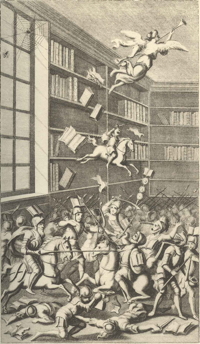

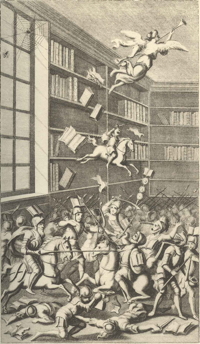

Jonathan Swift, The Battle of the Books (1704)

John Lilburne quoting Coke

|

Introduction

There are different schools of thought about what makes "the western tradition" "western". One common perspective (advocated here) is to argue that it was in "the west" where ideas about the individual (including individual "natural rights"), limits to the political power of the ruler, the rule of law, freedom of speech and religion, and free markets (in fact the whole discipline of "economics"), were preconditions for the emergence of the industrial revolution (and the massive increase in wealth this made possible) and the institutions and practices of "liberal democracy" such as constitutional government.

However, the emergence of these ideas, institutions, and practices was not inevitable and was in fact hotly contested within “the west” itself, both ideologically (in print) and politically (i.e. by the use of violence). Ideologically, it seems extraordinary to me that "the" western tradition could produce two such contrasting thinkers such as Karl Marx and Herbert Spencer, for example. Thus I think that the best way to understand how the ideas and institutions now associated with “the west” emerged, is to see it as the result of a “dialogue” or “conversation” (and sometimes an outright “battle of the books” as Jonathan Swift described it) between opposing positions.

Politically, many of the iconic texts of "the western tradition" were burned and/or banned and their authors censored, imprisoned, tortured, and even executed by the Catholic Church and various governments. In other words, they were "indexed". Thus, the struggle was not just an ideological one but also sometimes a violent political one since traditional ruling elites did not relinquish their power and privileges without episodes of violence, such as the Reformation and the Wars of Religion, the English Civil Wars and Revolution, and the revolutions that followed in North America, France, and across Europe in 1848. So it seems to me that the ideological disputes we can read in the texts need to be placed against the backdrop of political events, with the texts being seen as sometimes precursors to political change or reactions to previous political change.

My "Provocative Pairings" of some of the Texts

I suggest that an interesting way to read the "great books" of the western tradition is by pairing each one with a contemporary (or near contemporary) text which takes a different view. This approach works especially well with books on political, economic and social theory. See my paper on "The Conflicted Western Tradition: Some Provocative Pairings of Texts about Liberty and Power" for the Association of Core Texts and Courses annual conference, April 2019, Santa Fe, NM., where I explore this approach in more detail. And my more detailed study guide (to come).

Below is a list of some “great" (i.e. influential) books in the western tradition about political power which oppose the idea of individual liberty, free markets, and limited government and which I have paired with a contemporary "pro-liberty" text. Wherever possible I also link to the original language version of the texts as translations can be of variable quality (see the specific book page for details); and in a couple of instances I also include an Australian counterpart if it is available.

- Aesop's Fables (c. 500 BC) - the "contested" meaning of the text comes out in the difffering views of the editors/translators which have appeared over the years concerning how "the little people" can protect themselves from conartists and predators (both animal and human). [HTML]

- Machiavelli, The Prince (1513) [HTML] vs. Desiderius Erasmus, The Education of a Christian Prince (1515) [HTML] or the slightly later Étienne de la Boétie, Discourse on Voluntary Slavery (c. 1550s) [HTML]

- Jean Bodin, The Six Books of the Republic/Comonwealth) (1576) [HTML] vs. monarchomachs like Théodare Beza, François Hotman, and du Plessy-Mornay

- Thomas Mun, England’s Treasure by Forraign Trade (1644) [HTML] vs. Adam Smith, The Wealth of Nations (1776) [HTML]

- Charles Stuart (King Charles I), Eikon Basilike (The Icon or Image of the King) (1649) [HTML] vs. John Milton, Eikonoklastes (Iconoclasm) 1649) [HTML]

- Thomas Hobbes, Leviathan (1651) [HTML] vs. Richard Cumberland, A Treatise of the Laws of Nature (1672) [OLL] or Baruch Spinoza, Tractatus Theologico-Politicus (1670) [HTML]

- Sir Robert Filmer, Patriarcha, or the Natural Power of Kings (1680) [HTML] vs. John Locke, Two Treatises of Government (1688) [HTML]

- Leibniz, Theodicy: Essays on the Goodness of God, the Freedom of Man and the Origin of Evil (1710) [HTML] vs. Voltaire, Candide (159) [HTML]

- J.-J. Rousseau, Discourse on Inequality (1755) and The Social Contract (1762) [HTML] vs. Adam Smith, The Theory of Moral Sentiments (1759) [HTML]

- The American Declaration of Rights (1776) and the French Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen (1789, 1793, 1795) vs. Jeremy Bentham, Anarchical Fallacies (1795) [HTML]

- Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay, The Federalist (1788) vs. some “Anti-Federalist papers” (to be announced).

- Edmund Burke, Reflections on the French Revolution (1790) [HTML] and Letters on a Regicide Peace (1795) [HTML] vs. Mary Wollstonecraft, A Vindication of the Rights of Men (1790) [HTML] and A Vindication of the Rights of Women (1792) [HTML], and Thomas Paine, Rights of Man (1791) [HTML], and James Mackintosh, Vindiciae Gallicae (1791) [HTML]

- Thomas Malthus, An Essay on the Principle of Population (1798, 1826) [HTML] vs. Condorcet, The Progress of the Human Spirit (1795) [HTML] and William Godwin, Of Population (1820)

- Johann Fichte, Der geschlossene Handelsstaat (1800) [HTML auf deutsch] vs. Jean-Baptiste Say, A Treatise on Political Economy (1803) [HTML]

- Joseph de Maistre, Essay on the Generative Principle of Political Constitutions (1809) [HTML] vs. Benjamin Constant, Principles of Politics Applicable to all Governments (1815) [OLL]

- Hegel on political theory: Friedrich Hegel, Elements of the Philosophy of Right (1821) [English HTML] vs. the earlier work by William Godwin, Enquiry concerning Political Justice (1793) [HTML] or the more contemporary work by Benjamin Constant, Principles of Politics Applicable to all Governments (1815) [OLL]

- Hegel on war and the state: Hegel various writings and Elements of the Philosophy of Right (1821) vs. Immanuel Kant, Zum ewigen Frieden (On Perpetual Peace) (1795) [HTML]

- Carl von Clausewitz, On War (1832) [HTML] vs. Jean de Bloch, Future War (1898) [HTML extracts and PDF] [although not contemporarties their "conversation takes place across time)

- Friedrich List, The National System of Political Economy (1841) [HTML] vs. Henry George, Protection or Free Trade (1886) [HTML]

- Karl Marx, The Communist Manifesto (1848) in German [HTML] and English [HTML] vs. Frédéric Bastiat's election manifestos of 1848/49 and The State (1850) [OLL]

- an Australian perspective (admittedly out of time and place): the Australian Labor Party "Its Time" manifesto of 1972 vs. the Workers Party Platform of 1975

- Karl Marx, Das Kapital, vol. 1 (1867) [HTML] vs. John Stuart Mill, Principles of Political Economy (1848) [HTML] or Frédéric Bastiat, Economic Harmonies (1851) [HTML]

- an Australian perspective: William Hearn, Plutology (1863) [HTML]

- Edward Bellamy, Looking Backward. 2000-1887 (1888) [HTML} vs. Eugen Richter, Picture of a Socialist Future (1891) in German [facs. PDF and HTML] and English [facs. PDF and HTML]

- an Australian perspective: William Lane (John Millar), The Workingman’s Paradise (1892)

- George Bernard Shaw et al., Fabian Essays in Socialism (1889) [HTML] vs. Thomas Mackay, A Plea for Liberty: An Argument against Socialism and Socialistic Legislation (1891) [HTML] and A Policy Of Free Exchange (1894) [HTML]

- an Australian perspective: Bruce Smith, Liberty and Liberalism: A Protest against the growing Tendency toward undue Interference by the State, with Individual Liberty, Private Enterprise and the Rights of Property (1887) [HTML]

- Karl Marx, Das Kapital, vol. 2 (1885) [HTML] and vol. 3 (1894) [HTML] vs. Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk, Karl Marx and the Conclusion of his System of Thought: a Criticism (1896) in English [HTML] and German [HTML]

- Lenin, The State and Revolution (1917) [HTML] vs. Ludwig von Mises in an essay (1920), and then a book, Socialism (1922) [OLL]

- John Maynard Keynes, The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money (1936) [external HTML] vs. William H. Hutt, The Theory of Idle Resources (1939) [HTML], Ludwig von Mises, Political Economy: A Theory of Trade and Economics (1940) [facs. PDF (auf deutsch)], and Henry Hazlitt, The Failure of the “New Economics”: An Analysis of the Keynesian Fallacies (1959) [external PDF]

- The Beveridge Report (1942) [external HTML] vs. Friedrich Hayek, The Road to Serfdom (1944) [not available online]

More speculative as we enter the modern era:

- Paul R. Ehrlich, The Population Bomb (1968) and The Limits to Growth (1972) vs. Julian Simon, The Ultimate Resource (1981) [not available online]

- Two competing TV series: John Kenneth Galbraith "The Age of Uncertainty" (1977) vs. Milton Friedman, "Free to Choose" (1980)

Key:

- Pedro Berruguete (1450–1504), “St Dominic and the Albigenses” (c. 1495). St. Dominic shows that heretical Cathar books are consumed in the flames while orthodox Catholic books fly up unscathed. See larger version.]

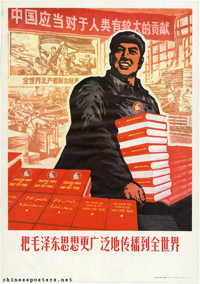

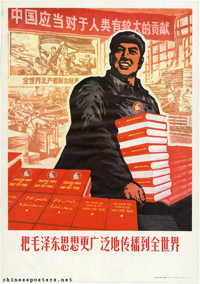

- “Broadcast Mao Zedong Thought more widespread all over the world” (June 1971). On the power of books to change the world (and in Mao's China with the help of a few gun barrels).

|