John Milton, EIKONOKLASTES In Answer To a Book Intitl’d EIKON BASILIKE, The Portrature of his Sacred Majesty in his Solitudes and Sufferings (1649)

|

|

Source

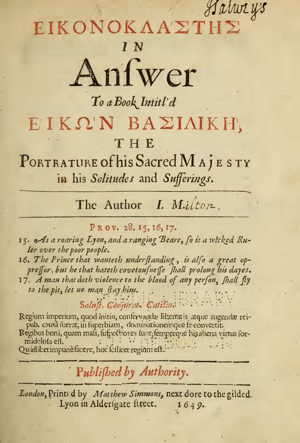

John Milton, EIKONOKLASTES In Answer To a Book Intitl’d EIKON BASILIKE, The Portrature of his Sacred Majesty in his Solitudes and Sufferings. The Author I. Milton. Published by Authority. (London, Printed by Matthew Simmons, next dore to the gilded Lyon in Aldersgate street. 1649.) The HTML comes from The Prose Works of John Milton. With a Biographical Introduction by Rufus Wilmot Griswold. In Two Volumes (Philadelphia: John W. Moore, 1847). [vol. 1 facs. PDF and facs. PDF of just Eikonoklastes]

See the facs. PDF of the original edition, and the facs. PDF of the 1847 edition from which the HTML comes. And also Charles Stuart's Eikon Basilike (169) [HTML and facs. PDF].

Table of Contents

ΙΚΟΝΟΚΛΑΣΤΗΣ. IN

ANSWER TO A BOOK ENTITLED, ΕΙΚΩΝ ΒΑΣΙΛΙΚΗ,

THE PORTRAITURE OF HIS MAJESTY IN HIS SOLITUDES AND SUFFERINGS.

ΙΚΟΝΟΚΛΑΣΤΗΣ. IN

ANSWER TO A BOOK ENTITLED, ΕΙΚΩΝ ΒΑΣΙΛΙΚΗ,

THE PORTRAITURE OF HIS MAJESTY IN HIS SOLITUDES AND SUFFERINGS.

- PREFACE.

ΙΚΟΝΟΚΛΑΣΤΗΣ.

ΙΚΟΝΟΚΛΑΣΤΗΣ.- THE PREFACE.

- I. Upon the king’s calling this last parliament.

- II. Upon The Earl of Strafford’s Death.

- III. Upon his going to the House of Commons.

- IV. Upon the Insolency of the tumults.

- V. Upon the Bill for triennial Parliaments, and for settling this, &c.

- VI. Upon his Retirement from Westminster.

- VII. Upon the Queen’s Departure.

- VIII. Upon his Repulse at Hull, and the Fate of the Hothams.

- IX. Upon the listing and raising Armies, &c.

- X. Upon their seizing the magazines, forts, &c.

- XI. Upon the Nineteen Propositions, &c.

- XII. Upon the Rebellion in Ireland.

- XIII. Upon the calling in of the Scots, and their coming.

- XIV. Upon the Covenant.

- XV. Upon the many Jealousies, &c.

- XVI. Upon the Ordinance against the Common Prayer Book.

- XVII. Of the differences in point of Church-Government.

- XVIII. Upon the Uxbridge Treaty, &c.

- XIX. Upon the various events of the War.

- XX. Upon the Reformation of the Times.

- XXI. Upon his letters taken and divulged.

- XXII. Upon his going to the Scots.

- XXIII. Upon the Scots delivering the king to the English.

- XXIV. Upon the denying him the attendance of his Chaplains.

- XXV. Upon his penitential Meditations and Vows at Holmby.

- XXVI. Upon the Army’s surprisal of the King at Holmby.

- XXVII. Entitled, To the Prince of Wales.

- XXVIII. Entitled Meditations upon Death.

- Endnotes

ΙΚΟΝΟΚΛΑΣΤΗΣ. IN

ANSWER TO A BOOK ENTITLED, ΕΙΚΩΝ ΒΑΣΙΛΙΚΗ,

THE PORTRAITURE OF HIS MAJESTY IN HIS SOLITUDES AND SUFFERINGS.

ΙΚΟΝΟΚΛΑΣΤΗΣ. IN

ANSWER TO A BOOK ENTITLED, ΕΙΚΩΝ ΒΑΣΙΛΙΚΗ,

THE PORTRAITURE OF HIS MAJESTY IN HIS SOLITUDES AND SUFFERINGS.

BY JOHN MILTON.

PUBLISHED FROM THE AUTHOR’S SECOND EDITION, PRINTED IN 1650 WITH MANY ENLARGEMENTS.

with a preface

BY RICHARD BARON,

SHOWING THE TRANSCENDENT EXCELLENCY OF MILTON’S PROSE WORKS,

to which is added,

AN ORIGINAL LETTER TO MILTON, NEVER BEFORE PUBLISHED.

— Morpheus, on thy dewy wing

Such fair auspicious visions bring,

As sooth’d great Milton’s injur’d age,

When in prophetic dreams he saw

The tribes unborn, with pious awe,

Imbibe each virtue from his heavenly page.

—Dr. Akenside.

PREFACE.

When the last impression of Milton’s prose works was committed to my care, I executed that trust with the greatest fidelity. Not satisfied with printing from any copy at hand, as editors are generally wont, my affection and zeal for the author induced me to compare every sentence, line by line, with the original edition of each treatise that I was able to obtain. Hence, errors innumerable of the former impression were corrected: besides what improvements were added from the author’s second edition of the Tenure of Kings and Magistrates, which Mr. Toland had either not seen, or had neglected to commit to the press.*

After I had endeavoured to do this justice to my favourite author, the last summer I discovered a second edition of his Eikonoklastes, with many large and curious additions, printed in the year 1650, which edition had escaped the notice both of Mr. Toland and myself.

In communicating this discovery to a few friends, I found that this edition was not unknown to some others, though from low and base motives secreted from the public. But I, who from my soul love liberty, and for that reason openly and boldly assert its principles at all times, resolved that the public should no longer be withheld from the possession of such a treasure.

I therefore now give a new impression of this work, with the additions and improvements made by the author; and I deem it a singular felicity, to be the instrument of restoring to my country so many excellent lines long lost,—and in danger of being for ever lost,—of a writer who is a lasting honour to our language and nation;—and of a work, wherein the principles of tyranny are confuted and overthrown and all the arts and cunning of a great tyrant and his adherents detected and laid open.

The love of liberty is a public affection, of which those men must be altogether void, that can suppress or smother any thing written in its defence, and tending to serve its glorious cause. What signify professions, when the actions are opposite and contradictory? Could any high-churchman, any partizan of Charles I., have acted a worse, or a different part, than some pretended friends of liberty have done in this instance? Many high-church priests and doctors have laid out considerable sums to destroy the prose works of Milton, and have purchased copies of his particular writings for the infernal pleasure of consuming them.† This practice, however detestable, was yet consistent with principle. But no apology can be made for men that espouse a cause, and at the same time conceal aught belonging to its support. Such men may tell us that they love liberty, but I tell them that they love their bellies, their ease, their pleasures, their profits, in the first place. A man that will not hazard all for liberty, is unworthy to be named among its votaries, unworthy to participate its blessings.

Many circumstances at present loudly call upon us to exert ourselves. Venality and corruption have well-nigh extinguished all principles of liberty. The bad books also, that this age hath produced, have ruined our youth. The novels and romances, which are eagerly purchased and read, emasculate the mind, and banish every thing grave and manly. One remedy for these evils is, to revive the reading of our old writers, of which we have good store, and the study whereof would fortify our youth against the blandishments of pleasure and the arts of corruption.

Milton in particular ought to be read and studied by all our young gentlemen as an oracle. He was a great and noble genius, perhaps the greatest that ever appeared among men; and his learning was equal to his genius. He had the highest sense of liberty, glorious thoughts, with a strong and nervous style. His works are full of wisdom, a treasure of knowledge. In them the divine, the statesman, the historian, the philologist, may be all instructed and entertained. It is to be lamented, that his divine writings are so little known. Very few are acquainted with them, many have never heard of them. The same is true with respect to another great writer contemporary with Milton, and an advocate for the same glorious cause; I mean Algernon Sydney, whose Discourses on Government are the most precious legacy to these nations.

All antiquity cannot show two writers equal to these. They were both great masters of reason, both great masters of expression. They had the strongest thoughts, and the boldest images, and are the best models that can be followed. The style of Sydney is always clear and flowing, strong and masculine. The great Milton has a style of his own, one fit to express the astonishing sublimity of his thoughts, the mighty vigour of his spirit, and that copia of invention, that redundancy of imagination, which no writer before or since hath equalled. In some places, it is confessed, that his periods are too long, which renders him intricate, if not altogether unintelligible to vulgar readers; but these places are not many. In the book before us his style is for the most part free and easy, and it abounds both in eloquence, and wit, and argument. I am of opinion, that the style of this work is the best and most perfect of all his prose writings. Other men have commended the style of his History as matchless and incomparable, whose malice could not see or would not acknowledge the excellency of his other works. It is no secret whence their aversion to Milton proceeds; and whence their caution of naming him as any other writer than a poet. Milton combated superstition and tyranny of every form, and in every degree. Against them he employed his mighty strength, and, like a battering ram, beat down all before him. But notwithstanding these mean arts, either to hide or disparage him, a little time will make him better known; and the more he is known, the more he will be admired. His works are not like the fugitive short-lived things of this age, few of which survive their authors: they are substantial, durable, eternal writings; which will never die, never perish, whilst reason, truth and liberty have a being in these nations.

Thus much I thought proper to say on occasion of this publication, wherein I have no resentment to gratify, no private interest to serve: all my aim is to strengthen and support that good old cause, which in my youth I embraced, and the principles whereof I will assert and maintain whilst I live.

The following letter to Milton, being very curious, and no where published perfect and entire, may be fitly preserved in this place.

A Letter from Mr. Wall to John Milton, Esquire.

Sir,—I received yours the day after you wrote, and do humbly thank you, that you are pleased to honour me with your letters. I confess I have (even in my privacy in the country) oft had thoughts of you, and that with much respect, for your friendliness to truth in your early years, and in bad times. But I was uncertain whether your relation to the court* (though I think a commonwealth was more friendly to you than a court) had not clouded your former light, but your last book resolved that doubt. You complain of the non-proficiency of the nation, and of its retrogade motion of late, in liberty and spiritual truths. It is much to be bewailed; but yet let us pity human frailty. When those who made deep protestations of their zeal for our liberty both spiritual and civil, and made the fairest offers to be assertors thereof, and whom we thereupon trusted; when those, being instated in power, shall betray the good thing committed to them, and lead us back to Egypt, and by that force which we gave them to win us liberty hold us fast in chains; what can poor people do? You know who they were, that watched our Saviour’s sepulchre to keep him from rising.†

Besides, whilst people are not free, but straitened in accommodations for life, their spirits will be dejected and servile: and conducing to that end, there should be an improving of our native commodities, as our manufactures, our fishery, our fens, forests, and commons, and our trade at sea, &c., which would give the body of the nation a comfortable subsistence; and the breaking that cursed yoke of tithes would much help thereto.

Also another thing I cannot but mention, which is, that the Norman conquest and tyranny is continued upon the nation without any thought of removing it; I mean the tenure of lands by copyhold, and holding for life under a lord, or rather tyrant of a manor; whereby people care not to improve their land by cost upon it, not knowing how soon themselves or theirs may be outed it; nor what the house is in which they live, for the same reason: and they are far more enslaved to the lord of the manor, than the rest of the nation is to a king or supreme magistrate.

We have waited for liberty, but it must be God’s work and not man’s, who thinks it sweet to maintain his pride and worldly interest to the gratifying of the flesh, whatever becomes of the precious liberty of mankind.

But let us not despond, but do our duty; and God will carry on that blessed work in despite of all opposites, and to their ruin if they persist therein.

Sir, my humble request is, that you would proceed, and give us that other member of the distribution mentioned in your book; viz. that Hire doth greatly impede truth and liberty: it is like if you do, you shall find opposers: but remember that saying, Beatus est pati quam frui: or, in the apostle’s words, James v. 11, We count them happy that endure.

I have sometimes thought (concurring with your assertion of that storied voice that should speak from heaven) when ecclesiastics were endowed with worldly preferments, hodie venenum infunditur in ecclesiam: for to use the speech of Genesis iv. ult. according to the sense which it hath in the Hebrew, then began men to corrupt the worship of God. I shall tell you a supposal of mine, which is this: Mr. Dury has bestowed about thirty years time in travel, conference, and writings, to reconcile Calvinists and Lutherans, and that with little or no success. But the shortest way were,—take away ecclesiastical dignities, honours, and preferments, on both sides, and all would soon be hushed; the ecclesiastics would be quiet, and then the people would come forth into truth and liberty. But I will not engage in this quarrel; yet I shall lay this engagement upon myself to remain

Your faithful friend and servant,

Causham, May 26, 1659.

John Wall.

From this letter the reader may see in what way wise and good men of that age employed themselves: in studying to remove every grievance, to break every yoke. And it is matter of astonishment, that this age, which boasts of greatest light and knowledge, should make no effort toward a reformation in things acknowledged to be wrong: but both in religion and in civil government be barbarian!

Below Blackheath, June 20, 1756.

Richard Baron.

ΙΚΟΝΟΚΛΑΣΤΗΣ.

ΙΚΟΝΟΚΛΑΣΤΗΣ.

- Prov. xxviii. 15. As a roaring lion, and a raging bear, so is a wicked ruler over the poor people.

- 16. The prince that wanteth understanding, is also a great oppressor; but he that hateth covetousness, shall prolong his days.

- 17. A man that doth violence to the blood of any person, shall fly to the pit, let no man stay him.

sallust. conjurat. catilin.

Regium imperium, quod initio, conservandæ libertatis, atque augendæ reipublicæ causâ fuerat, in superbiam, dominationemque se convertit.

Regibus boni, quam mali, suspectiores sunt, semperque his aliena virtus formidolosa est Impunè quælibet facere, id est regem esse.

—idem, bell. jugurth.

published by authority.

THE PREFACE.

To descant on the misfortunes of a person fallen from so high a dignity, who hath also paid his final debt, both to nature and his faults, is neither of itself a thing commendable, nor the intention of this discourse. Neither was it fond ambition, nor the vanity to get a name, present or with posterity, by writing against a king. I never was so thirsty after fame, nor so destitute of other hopes and means, better and more certain to attain it; for kings have gained glorious titles from their favourers by writing against private men, as Henry VIIIth. did against Luther; but no man ever gained much honour by writing against a king, as not usually meeting with that force of argument in such courtly antagonists, which to convince might add to his reputation. Kings most commonly, though strong in legions, are but weak at arguments; as they who ever have accustomed from the cradle to use their will only as their right hand, their reason always as their left. Whence unexpectedly constrained to that kind of combat, they prove but weak and puny adversaries: nevertheless, for their sakes, who, through custom, simplicity, or want of better teaching, have no more seriously considered kings, than in the gaudy name of majesty, and admire them and their doings as if they breathed not the same breath with other mortal men, I shall make no scruple to take up (for it seems to be the challenge both of him and all his party) to take up this gauntlet, though a king’s, in the behalf of liberty and the commonwealth.

And further, since it appears manifestly the cunning drift of a factious and defeated party, to make the same advantage of his book, which they did before of his regal name and authority, and intend it not so much the defence of his former actions, as the promoting of their own future designs, (making thereby the book their own rather than the king’s, as the benefit now must be their own more than his;) now the third time to corrupt and disorder the minds of weaker men, by new suggestions and narrations, either falsely or fallaciously representing the state of things to the dishonour of this present government, and the retarding of a general peace, so needful to this afflicted nation, and so nigh obtained; I suppose it no injury to the dead, but a good deed rather to the living, if by better information given them, or, which is enough, by only remembering them the truth of what they themselves know to be here misaffirmed, they may be kept from entering the third time unadvisedly into war and bloodshed: for as to any moment of solidity in the book itself, (save only that a king is said to be the author, a name, than which there needs no more among the blockish vulgar, to make it wise, and excellent, and admired, nay to set it next the Bible, though otherwise containing little else but the common grounds of tyranny and popery, dressed up the better to deceive, in a new protestant guise, trimly garnished over,) or as to any need of answering, in respect of staid and well-principled men, I take it on me as a work assigned rather, than by me chosen or affected: which was the cause both of beginning it so late, and finishing it so leisurely in the midst of other employments and diversions. And though well it might have seemed in vain to write at all, considering the envy and almost infinite prejudice likely to be stirred up among the common sort, against whatever can be written or gainsaid to the king’s book, so advantageous to a book it is only to be a king’s; and though it be an irksome labour, to write with industry and judicious pains, that which, neither weighed nor well read, shall be judged without industry or the pains of well-judging, by faction and the easy literature of custom and opinion; it shall be ventured yet, and the truth not smothered, but sent abroad in the native confidence of her single self, to earn, how she can, her entertainment in the world, and to find out her own readers: few perhaps, but those few, of such value and substantial worth, as truth and wisdom, not respecting numbers and big names, have been ever wont in all ages to be contented with. And if the late king had thought sufficient those answers and defences made for him in his lifetime, they who on the other side accused his evil government, judging that on their behalf enough also hath been replied, the heat of this controversy was in all likelihood drawing to an end; and the further mention of his deeds, not so much unfortunate as faulty, had in tenderness to his late sufferings been willingly foreborne; and perhaps for the present age might have slept with him unrepeated, while his adversaries, calmed and assuaged with the success of their cause, had been the less unfavourable to his memory. But since he himself, making new appeal to truth and the world, hath left behind him this book, as the best advocate and interpreter of his own actions, and that his friends by publishing, dispersing, commending, and almost adoring it, seem to place therein the chief strength and nerves of their cause; it would argue doubtless in the other party great deficience and distrust of themselves, not to meet the force of his reason in any field whatsoever, the force and equipage of whose arms they have so often met victoriously: and he who at the bar stood excepting against the form and manner of his judicature, and complained that he was not heard; neither he nor his friends shall have that cause now to find fault, being met and debated with in this open and monumental court of his erecting; and not only heard uttering his whole mind at large, but answered: which to do effectually, if it be necessary, that to his book nothing the more respect be had for being his, they of his own party can have no just reason to exclaim. For it were too unreasonable that he, because dead, should have the liberty in his book to speak all evil of the parliament; and they because living, should be expected to have less freedom, or any for them, to speak home the plain truth of a full and pertinent reply. As he, to acquit himself, hath not spared his adversaries to load them with all sorts of blame and accusation, so to him, as in his book alive, there will be used no more courtship than he uses; but what is properly his own guilt, not imputed any more to his evil counsellors, (a ceremony used longer by the parliament than he himself desired,) shall be laid here without circumlocutions at his own door. That they who from the first beginning, or but now of late, by what unhappiness I know not, are so much affatuated, not with his person only, but with his palpable faults, and doat upon his deformities, may have none to blame but their own folly, if they live and die in such a strooken blindness, as next to that of Sodom hath not happened to any sort of men more gross, or more misleading. Yet neither let his enemies expect to find recorded here all that hath been whispered in the court, or alleged openly, of the king’s bad actions; it being the proper scope of this work in hand, not to rip up and relate the misdoings of his whole life, but to answer only and refute the missayings of his book.

First, then, that some men (whether this were by him intended, or by his friends) have by policy accomplished after death that revenge upon their enemies, which in life they were not able, hath been oft related. And among other examples we find, that the last will of Cæsar being read to the people, and what bounteous legacies he had bequeathed them, wrought more in that vulgar audience to the avenging of his death, than all the art he could ever use to win their favour in his lifetime. And how much their intent, who published these overlate apologies and meditations of the dead king, drives to the same end of stirring up the people to bring him that honour, that affection, and by consequence that revenge to his dead corpse, which he himself living could never gain to his person, it appears both by the conceited portraiture before his book, drawn out to the full measure of a masking scene, and set there to catch fools and silly gazers; and by those Latin words after the end, Vota dabunt quæ bella negarunt; intimating, that what he could not compass by war, he should achieve by his meditations: for in words which admit of various sense, the liberty is ours, to choose that interpretation, which may best mind us of what our restless enemies endeavour, and what we are timely to prevent. And here may be well observed the loose and negligent curiosity of those, who took upon them to adorn the setting out of this book; for though the picture set in front would martyr him and saint him to befool the people, yet the Latin motto in the end, which they understand not, leaves him, as it were, a politic contriver to bring about that interest, by fair and plausible words, which the force of arms denied him. But quaint emblems and devices, begged from the old pageantry of some twelfthnight’s entertainment at Whitehall, will do but ill to make a saint or martyr: and if the people resolve to take him sainted at the rate of such a canonizing, I shall suspect their calendar more than the Gregorian. In one thing I must commend his openness, who gave the title to this book, Ει![]()

![]() ν Βασιλι

ν Βασιλι![]()

![]() , that is to say, The King’s Image; and by the shrine he dresses out for him, certainly would have the people come and worship him. For which reason this answer also is entitled, Iconoclastes, the famous surname of many Greek emperors, who in their zeal to the command of God, after long tradition of idolatry in the church, took courage and broke all superstitious images to pieces. But the people, exorbitant and excessive in all their motions, are prone ofttimes not to a religious only, but to a civil kind of idolatry, in idolizing their kings: though never more mistaken in the object of their worship; heretofore being wont to repute for saints those faithful and courageous barons, who lost their lives in the field, making glorious war against tyrants for the common liberty; as Simon de Momfort, earl of Leicester, against Henry the IIId; Thomas Plantagenet, earl of Lancaster, against Edward IId. But now, with a besotted and degenerate baseness of spirit, except some few who yet retain in them the old English fortitude and love of freedom, and have testified it by their matchless deeds, the rest, imbastardized from the ancient nobleness of their ancestors, are ready to fall flat and give adoration to the image and memory of this man, who hath offered at more cunning fetches to undermine our liberties, and put tyranny into an art, than any British king before him: which low dejection and debasement of mind in the people, I must confess, I cannot willingly ascribe to the natural disposition of an Englishman, but rather to two other causes; first, to the prelates and their fellow-teachers, though of another name and sect,* whose pulpit-stuff, both first and last, hath been the doctrine and perpetual infusion of servility and wretchedness to all their hearers, and whose lives the type of worldliness and hypocrisy, without the least true pattern of virtue, righteousness, or self-denial in their whole practice. I attribute it next to the factious inclination of most men divided from the public by several ends and humours of their own. At first no man less beloved, no man more generally condemned, than was the king; from the time that it became his custom to break parliaments at home, and either wilfully or weakly to betray protestants abroad, to the beginning of these combustions. All men inveighed against him; all men, except court-vassals, opposed him and his tyrannical proceedings; the cry was universal; and this full parliament was at first unanimous in their dislike and protestation against his evil government. But when they, who sought themselves and not the public, began to doubt, that all of them could not by one and the same way attain to their ambitious purposes, then was the king, or his name at least, as a fit property first made use of, his doings made the best of, and by degrees justified; which begot him such a party, as, after many wiles and strugglings with his inward fears, emboldened him at length to set up his standard against the parliament: whenas before that time, all his adherents, consisting most of dissolute swordsmen and suburb-roysters, hardly amounted to the making up of one ragged regiment strong enough to assault the unarmed house of commons. After which attempt, seconded by a tedious and bloody war on his subjects, wherein he hath so far exceeded those his arbitrary violences in time of peace, they who before hated him for his high misgovernment, nay fought against him with displayed banners in the field, now applaud him and extol him for the wisest and most religious prince that lived. By so strange a method amongst the mad multitude is a sudden reputation won, of wisdom by wilfulness and subtle shifts, of goodness by multiplying evil, of piety by endeavouring to root out true religion.

, that is to say, The King’s Image; and by the shrine he dresses out for him, certainly would have the people come and worship him. For which reason this answer also is entitled, Iconoclastes, the famous surname of many Greek emperors, who in their zeal to the command of God, after long tradition of idolatry in the church, took courage and broke all superstitious images to pieces. But the people, exorbitant and excessive in all their motions, are prone ofttimes not to a religious only, but to a civil kind of idolatry, in idolizing their kings: though never more mistaken in the object of their worship; heretofore being wont to repute for saints those faithful and courageous barons, who lost their lives in the field, making glorious war against tyrants for the common liberty; as Simon de Momfort, earl of Leicester, against Henry the IIId; Thomas Plantagenet, earl of Lancaster, against Edward IId. But now, with a besotted and degenerate baseness of spirit, except some few who yet retain in them the old English fortitude and love of freedom, and have testified it by their matchless deeds, the rest, imbastardized from the ancient nobleness of their ancestors, are ready to fall flat and give adoration to the image and memory of this man, who hath offered at more cunning fetches to undermine our liberties, and put tyranny into an art, than any British king before him: which low dejection and debasement of mind in the people, I must confess, I cannot willingly ascribe to the natural disposition of an Englishman, but rather to two other causes; first, to the prelates and their fellow-teachers, though of another name and sect,* whose pulpit-stuff, both first and last, hath been the doctrine and perpetual infusion of servility and wretchedness to all their hearers, and whose lives the type of worldliness and hypocrisy, without the least true pattern of virtue, righteousness, or self-denial in their whole practice. I attribute it next to the factious inclination of most men divided from the public by several ends and humours of their own. At first no man less beloved, no man more generally condemned, than was the king; from the time that it became his custom to break parliaments at home, and either wilfully or weakly to betray protestants abroad, to the beginning of these combustions. All men inveighed against him; all men, except court-vassals, opposed him and his tyrannical proceedings; the cry was universal; and this full parliament was at first unanimous in their dislike and protestation against his evil government. But when they, who sought themselves and not the public, began to doubt, that all of them could not by one and the same way attain to their ambitious purposes, then was the king, or his name at least, as a fit property first made use of, his doings made the best of, and by degrees justified; which begot him such a party, as, after many wiles and strugglings with his inward fears, emboldened him at length to set up his standard against the parliament: whenas before that time, all his adherents, consisting most of dissolute swordsmen and suburb-roysters, hardly amounted to the making up of one ragged regiment strong enough to assault the unarmed house of commons. After which attempt, seconded by a tedious and bloody war on his subjects, wherein he hath so far exceeded those his arbitrary violences in time of peace, they who before hated him for his high misgovernment, nay fought against him with displayed banners in the field, now applaud him and extol him for the wisest and most religious prince that lived. By so strange a method amongst the mad multitude is a sudden reputation won, of wisdom by wilfulness and subtle shifts, of goodness by multiplying evil, of piety by endeavouring to root out true religion.

But it is evident that the chief of his adherents never loved him, never honoured either him or his cause, but as they took him to set a face upon their own malignant designs, nor bemoan his loss at all, but the loss of their own aspiring hopes: like those captive women, whom the poet notes in his Iliad, to have bewailed the death of Patroclus in outward show, but indeed their own condition.

Πάτρο

λον προ

ασιν, σ

ν δ’

τ

ν

ήδε

άςη.—

Hom. Iliad. τ.

And it needs must be ridiculous to any judgment unenthralled, that they, who in other matters express so little fear either of God or man, should in this one particular outstrip all precisianism with their scruples and cases, and fill men’s ears continually with the noise of their conscientious loyalty and allegiance to the king, rebels in the meanwhile to God in all their actions besides: much less that they, whose professed loyalty and allegiance led them to direct arms against the king’s person, and thought him nothing violated by the sword of hostility drawn by them against him, should now in earnest think him violated by the unsparing sword of justice, which undoubtedly so much the less in vain she bears among men, by how much greater and in highest place the offender. Else justice, whether moral or political, were not justice, but a false counterfeit of that impartial and godlike virtue. The only grief is, that the head was not strook off to the best advantage and commodity of them that held it by the hair:* an ingrateful and perverse generation, who having first cried to God to be delivered from their king, now murmur against God that heard their prayers, and cry as loud for their king against those that delivered them. But as to the author of these soliloquies, whether it were undoubtedly the late king, as is vulgarly believed, or any secret coadjutor, and some stick not to name him; it can add nothing, nor shall take from the weight, if any be, of reason which he brings. But allegations, not reasons, are the main contents of this book, and need no more than other contrary allegations to lay the question before all men in an even balance; though it were supposed, that the testimony of one man, in his own cause affirming, could be of any moment to bring in doubt the authority of a parliament denying. But if these his fair-spoken words shall be here fairly confronted and laid parallel to his own far differing deeds, manifest and visible to the whole nation, then surely we may look on them who, notwithstanding, shall persist to give to bare words more credit than to open deeds, as men whose judgment was not rationally evinced and persuaded, but fatally stupefied and bewitched into such a blind and obstinate belief: for whose cure it may be doubted, not whether any charm, though never so wisely murmured, but whether any prayer can be available. This however would be remembered and well noted, that while the king, instead of that repentance which was in reason and in conscience to be expected from him, without which we could not lawfully readmit him, persists here to maintain and justify the most apparent of his evil doings, and washes over with a court-fucus the worst and foulest of his actions, disables and uncreates the parliament itself, with all our laws and native liberties that ask not his leave, dishonours and attaints all protestant churches not prelatical, and what they piously reformed, with the slander of rebellion, sacrilege, and hypocrisy; they, who seemed of late to stand up hottest for the covenant, can now sit mute and much pleased to hear all these opprobrious things uttered against their faith, their freedom, and themselves in their own doings made traitors to boot: the divines, also, their wizards, can be so brazen as to cry Hosanna to this his book, which cries louder against them for no disciples of Christ, but of Iscariot; and to seem now convinced with these withered arguments and reasons here, the same which in some other writings of that party, and in his own former declarations and expresses, they have so often heretofore endeavoured to confute and to explode; none appearing all this while to vindicate church or state from these calumnies and reproaches but a small handful of men, whom they defame and spit at with all the odious names of schism and sectarism. I never knew that time in England, when men of truest religion were not counted sectaries: but wisdom now, valour, justice, constancy, prudence united and embodied to defend religion and our liberties, both by word and deed, against tyranny, is counted schism and faction. Thus in a graceless age things of highest praise and imitation under a right name, to make them infamous and hateful to the people, are miscalled. Certainly, if ignorance and perverseness will needs be national and universal, then they who adhere to wisdom and to truth, are not therefore to be blamed, for being so few as to seem a sect or faction. But in my opinion it goes not ill with that people where these virtues grow so numerous and well joined together, as to resist and make head against the rage and torrent of that boisterous folly and superstition, that possesses and hurries on the vulgar sort. This therefore we may conclude to be a high honour done us from God, and a special mark of his favour, whom he hath selected as the sole remainder, after all these changes and commotions, to stand upright and stedfast in his cause; dignified with the defence of truth and public liberty; while others, who aspired to be the top of zealots, and had almost brought religion to a kind of trading monopoly, have not only by their late silence and neutrality belied their profession, but foundered themselves and their consciences, to comply with enemies in that wicked cause and interest, which they have too often cursed in others, to prosper now in the same themselves.

I. Upon the king’s calling this last parliament.

That which the king lays down here as his first foundation, and as it were the head stone of his whole structure, that “he called this last parliament, not more by others’ advice, and the necessity of his affairs, than by his own choice and inclination;” is to all knowing men so apparently not true, that a more unlucky and inauspicious sentence, and more betokening the downfall of his whole fabric, hardly could have come into his mind. For who knows not, that the inclination of a prince is best known either by those next about him, and most in favour with him, or by the current of his own actions? Those nearest to this king, and most his favourites, were courtiers and prelates; men whose chief study was to find out which way the king inclined, and to imitate him exactly: how these men stood affected to parliaments cannot be forgotten. No man but may remember, it was their continual exercise to dispute and preach against them; and in their common discourse nothing was more frequent, than that “they hoped the king should now have no need of parliaments any more.” And this was but the copy, which his parasites had industriously taken from his own words and actions, who never called a parliament but to supply his necessities; and having supplied those, as suddenly and ignominiously dissolved it, without redressing any one grievance of the people: sometimes choosing rather to miss of his subsidies, or to raise them by illegal courses, than that the people should not still miss of their hopes to be relieved by parliaments.

The first he broke off at his coming to the crown, for no other cause than to protect the duke of Buckingham against them who had accused him, besides other heinous crimes, of no less than poisoning the deceased king his father; concerning which matter the declaration of “No more Addresses” hath sufficiently informed us. And still the latter breaking was with more affront and indignity put upon the house and her worthiest members, than the former. Insomuch that in the fifth year of his reign, in a proclamation he seems offended at the very rumour of a parliament divulged among the people; as if he had taken it for a kind of slander, that men should think him that way exorable, much less inclined: and forbids it as a presumption to prescribe him any time for parliaments; that is to say, either by persuasion or petition, or so much as the reporting of such a rumour: for other manner of prescribing was at that time not suspected. By which fierce edict, the people, forbidden to complain, as well as forced to suffer, began from thenceforth to despair of parliaments. Whereupon such illegal actions, and especially to get vast sums of money, were put in practice by the king and his new officers, as monopolies, compulsive knighthoods, coat, conduct, and ship-money, the seizing not of one Naboth’s vineyard, but of whole inheritances, under the pretence of forest or crown-lands; corruption and bribery compounded for, with impunities granted for the future, as gave evident proof, that the king never meant, nor could it stand with the reason of his affairs, ever to recall parliaments: having brought by these irregular courses the people’s interest and his own to so direct an opposition, that he might foresee plainly, if nothing but a parliament could save the people, it must necessarily be his undoing.

Till eight or nine years after, proceeding with a high hand in these enormities, and having the second time levied an injurious war against his native country Scotland; and finding all those other shifts of raising money, which bore out his first expedition, now to fail him, not “of his own choice and inclination,” as any child may see, but urged by strong necessities, and the very pangs of state, which his own violent proceedings had brought him to, he calls a parliament; first in Ireland, which only was to give him four subsidies and so to expire; then in England, where his first demand was but twelve subsidies to maintain a Scots war, condemned and abominated by the whole kingdom: promising their grievances should be considered afterwards. Which when the parliament, who judged that war itself one of their main grievances, made no haste to grant, not enduring the delay of his impatient will, or else fearing the conditions of their grant, he breaks off the whole session, and dismisses them and their grievances with scorn and frustration.

Much less therefore did he call this last parliament by his own choice and inclination; but having first tried in vain all undue ways to procure money, his army of their own accord being beaten in the north, the lords petitioning, and the general voice of the people almost hissing him and his ill acted regality off the stage, compelled at length both by his wants and by his fears, upon mere extremity he summoned this last parliament. And how is it possible, that he should willingly incline to parliaments, who never was perceived to call them but for the greedy hope of a whole national bribe, his subsidies; and never loved, never fulfilled, never promoted the true end of parliaments, the redress of grievances; but still put them off, and prolonged them, whether gratified or not gratified; and was indeed the author of all those grievances? To say, therefore, that he called this parliament of his own choice and inclination, argues how little truth we can expect from the sequel of this book, which ventures in the very first period to affront more than one nation with an untruth so remarkable; and presumes a more implicit faith in the people of England, than the pope ever commanded from the Romish laity; or else a natural sottishness fit to be abused and ridden; while in the judgment of wise men, by laying the foundation of his defence on the avouchment of that which is so manifestly untrue, he hath given a worse soil to his own cause, than when his whole forces were at any time overthrown. They therefore, who think such great service done to the king’s affairs in publishing this book, will find themselves in the end mistaken; if sense and right mind, or but any mediocrity of knowledge and remembrance, hath not quite forsaken men.

But to prove his inclination to parliaments, he affirms here, “to have always thought the right way of them most safe for his crown, and best pleasing to his people.” What he thought, we know not, but that he ever took the contrary way, we saw; and from his own actions we felt long ago what he thought of parliaments or of pleasing his people: a surer evidence than what we hear now too late in words.

He alleges, that “the cause of forbearing to convene parliaments was the sparks, which some men’s distempers there studied to kindle.” They were indeed not tempered to his temper; for it neither was the law, nor the rule, by which all other tempers were to be tried; but they were esteemed and chosen for the fittest men, in their several counties, to allay and quench those distempers, which his own inordinate doings had inflamed. And if that were his refusing to convene, till those men had been qualified to his temper, that is to say, his will, we may easily conjecture what hope there was of parliaments, had not fear and his insatiate poverty, in the midst of his excessive wealth, constrained him.

“He hoped by his freedom and their moderation to prevent misunderstandings.” And wherefore not by their freedom and his moderation? But freedom he thought too high a word for them, and moderation too mean a word for himself: this was not the way to prevent misunderstandings. He still “feared passion and prejudice in other men;” not in himself: “and doubted not by the weight of his” own “reason, to counterpoise any faction;” it being so easy for him, and so frequent, to call his obstinacy reason, and other men’s reason faction. We in the mean while must believe that wisdom and all reason came to him by title with his crown; passion, prejudice, and faction came to others by being subjects.

“He was sorry to hear, with what popular heat elections were carried in many places.” Sorry rather, that court-letters and intimations prevailed no more, to divert or to deter the people from their free election of those men, whom they thought best affected to religion and their country’s liberty, both at that time in danger to be lost. And such men they were, as by the kingdom were sent to advise him, not sent to be cavilled at, because elected, or to be entertained by him with an undervalue and misprision of their temper, judgment, or affection. In vain was a parliament thought fittest by the known laws of our nation, to advise and regulate unruly kings, if they, instead of hearkening to advice, should be permitted to turn it off, and refuse it by vilifying and traducing their advisers, or by accusing of a popular heat those that lawfully elected them.

“His own and his children’s interest obliged him to seek, and to preserve the love and welfare of his subjects.” Who doubts it? But the same interest, common to all kings, was never yet available to make them all seek that, which was indeed best for themselves and their posterity. All men by their own and their children’s interest are obliged to honesty and justice: but how little that consideration works in private men, how much less in kings, their deeds declare best.

“He intended to oblige both friends and enemies, and to exceed their desires, did they but pretend to any modest and sober sense;” mistaking the whole business of a parliament; which met not to receive from him obligations, but justice; nor he to expect from them their modesty, but their grave advice, uttered with freedom in the public cause. His talk of modesty in their desires of the common welfare argues him not much to have understood what he had to grant, who misconceived so much the nature of what they had to desire. And for “sober sense,” the expression was too mean, and recoils with as much dishonour upon himself, to be a king where sober sense could possibly be so wanting in a parliament.

“The odium and offences, which some men’s rigour, or remissness in church and state, had contracted upon his government, he resolved to have expiated with better laws and regulations.” And yet the worst of misdemeanors committed by the worst of all his favourites in the height of their dominion, whether acts of rigour or remissness, he hath from time to time continued, owned, and taken upon himself by public declarations, as often as the clergy, or any other of his instruments, felt themselves overburdened with the people’s hatred. And who knows not the superstitious rigour of his Sunday’s chapel, and the licentious remissness of his Sunday’s theatre; accompanied with that reverend statute for Dominical jigs and maypoles, published in his own name, and derived from the example of his father James? Which testifies all that rigour in superstition, all that remissness in religion, to have issued out originally from his own house, and from his own authority. Much rather then may those general miscarriages in state, his proper sphere, be imputed to no other person chiefly than to himself. And which of all those oppressive acts or impositions did he ever disclaim or disavow, till the fatal awe of this parliament hung ominously over him? Yet here he smoothly seeks to wipe off all the envy of his evil government upon his substitutes and under-officers; and promises, though much too late, what wonders he purposed to have done in the reforming of religion: a work wherein all his undertakings heretofore declared him to have had little or no judgment: neither could his breeding, or his course of life, acquaint him with a thing so spiritual. Which may well assure us what kind of reformation we could expect from him; either some politic form of an imposed religion, or else perpetual vexation and persecution to all those that complied not with such a form. The like amendment he promises in state; not a step further “than his reason and conscience told him was fit to be desired;” wishing “he had kept within those bounds, and not suffered his own judgment to have been overborne in some things,” of which things one was the earl of Strafford’s execution. And what signifies all this, but that still his resolution was the same, to set up an arbitrary government of his own, and that all Britain was to be tied and chained to the conscience, judgment, and reason of one man; as if those gifts had been only his peculiar and prerogative, entailed upon him with his fortune to be a king? Whenas doubtless no man so obstinate, or so much a tyrant, but professes to be guided by that which he calls his reason and his judgment, though never so corrupted; and pretends also his conscience. In the mean while, for any parliament or the whole nation to have either reason, judgment, or conscience, by this rule was altogether in vain, if it thwarted the king’s will; which was easy for him to call by any other plausible name. He himself hath many times acknowledged, to have no right over us but by law; and by the same law to govern us: but law in a free nation hath been ever public reason, the enacted reason of a parliament; which he denying to enact, denies to govern us by that which ought to be our law; interposing his own private reason, which to us is no law. And thus we find these fair and specious promises, made upon the experience of many hard sufferings, and his most mortified retirements, being thoroughly sifted to contain nothing in them much different from his former practices, so cross, and so reverse to all his parliaments, and both the nations of this island. What fruits they could in likelihood have produced in his restorement, is obvious to any prudent foresight.

And this is the substance or his first section, till we come to the devout of it, modelled into the form of a private psalter. Which they who so much admire, either for the matter of the manner, may as well admire the archbishop’s late breviary, and many other as good manuals and handmaids of Devotion, the lip-work of every prelatical liturgist, clapped together and quilted out of Scripture phrase, with as much ease, and as little need of Christian diligence or judgment, as belongs to the compiling of any ordinary and saleable piece of English divinity, that the shops value. But he who from such a kind of psalmistry, or any other verbal devotion, without the pledge and earnest of suitable deeds, can be persuaded of a zeal and true righteousness in the person, hath much yet to learn; and knows not that the deepest policy of a tyrant hath been ever to counterfeit religious. And Aristole in his Politics hath mentioned that special craft among twelve other tyrannical sophisms. Neither want we examples: Andronicus Commenus the Byzantine emperor, though a most cruel tyrant, is reported by Nicetas, to have been a constant reader of Saint Paul’s epistles; and by continual study had so incorporated the phrase and style of that transcendant apostle into all his familiar letters, that the imitation seemed to vie with the original. Yet this availed not to deceive the people of that empire, who, notwithstanding his saint’s vizard, tore him to pieces for his tyranny. From stories of this nature both ancient and modern which abound, the poets also, and some English, have been in this point so mindful of decorum, as to put never more pious words in the mouth of any person, than of a tyrant. I shall not instance an abstruse author, wherein the king might be less conversant, but one whom we well know was the closet companion of these his solitudes, William Shakespeare; who introduces the person of Richard the third, speaking in as high a strain of piety and mortification as is uttered in any passage of this book, and sometimes to the same sense and purpose with some words in this place; “I intended,” saith he, “not only to oblige my friends but my enemies.” The like saith Richard, Act II. Scene 1.

“I do not know that Englishman alive,

With whom my soul is any jot at odds,

More than the infant that is born to night;

I thank my God for my humility.”

Other stuff of this sort may be read throughout the whole tragedy, where in the poet used not much license in departing from the truth of history which delivers him a deep dissembler, not of his affections only, but of religion.

In praying therefore, and in the outward work of devotion, this king we see hath not at all exceeded the worst of kings before him. But herein the worst of kings, professing Christianism, have by far exceeded him. They, for aught we know, have still prayed their own, or at least borrowed from fit authors. But this king, not content with that which, although in a thing holy, is no holy theft, to attribute to his own making other men’s whole prayers, hath as it were unhallowed and unchristened the very duty of prayer itself, by borrowing to a Christian use prayers offered to a heathen god. Who would have imagined so little fear in him of the true all-seeing Deity, so little reverence of the Holy Ghost, whose office is to dictate and present our Christian prayers, so little care of truth in his last words, or honour to himself, or to his friends, or sense of his afflictions, or of that sad hour which was upon him, as immediately before his death to pop into the hand of that great bishop who attended him, for a special relic of his saintly exercises, a prayer stolen word for word from the mouth of a heathen woman* praying to a heathen god; and that in no serious book, but the vain amatorious poem of Sir Philip Sidney’s Arcadia; a book in that kind full of worth and wit, but among religious thoughts and duties not worthy to be named; nor to be read at any time without good caution, much less in time of trouble and affliction to be a Christian’s prayer-book? They who are yet incredulous of what I tell them for a truth, that this philippic prayer is no part of the king’s goods, may satisfy their own eyes at leisure, in the 3d book of Sir Philip’s Arcadia, p. 248, comparing Pamela’s prayer with the first prayer of his majesty, delivered to Dr. Juxton immediately before his death, and entitled a Prayer in time of Captivity, printed in all the best editions of his book. And since there be a crew of lurking railers, who in their libels, and their fits of railing up and down, as I hear from others, take it so currishly, that I should dare to tell abroad the secrets of their Ægyptian Apis; to gratify their gall in some measure yet more, which to them will be a kind of alms, (for it is the weekly vomit of their gall which to most of them is the sole means of their feeding,) that they may not starve for me, I shall gorge them once more with this digression somewhat larger than before: nothing troubled or offended at the working upward of their salevenom thereupon, though it happen to asperse me; being, it seems, their best livelihood, and the only use or good digestion that their sick and perishing minds can make of truth charitably told them. However, to the benefit of others much more worth the gaining, I shall proceed in my assertion; that if only but to taste wittingly of meat or drink offered to an idol, be in the doctrine of St. Paul judged a pollution much more must be his sin, who takes a prayer so dedicated into his mouth, and offers it to God. Yet hardly it can be thought upon (though how sad a thing!) without some kind of laughter at the manner and solemn transaction of so gross a cozenage, that he, who had trampled over us so stately and so tragically, should leave the world at last so ridiculously in his exit, as to bequeath among his deifying friends that stood about him such a precious piece of mockery to be published by them, as must needs cover both his and their heads with shame, if they have any left. Certainly they that will may now see at length how much they were deceived in him, and were ever like to be hereafter, who cared not, so near the minute of his death, to deceive his best and dearest friends with the trumpery of such a prayer, not more secretly than shamefully purloined; yet given them as the royal issue of his own proper zeal. And sure it was the hand of God to let them fall, and be taken in such a foolish trap, as hath exposed them to all derision; if for nothing else, to throw contempt and disgrace in the sight of all men, upon this his idolized book, and the whole rosary of his prayers; thereby testifying how little he excepted them from those, who thought no better of the living God than of a buzzard idol, fit to be so served and worshiped in reversion, with the polluted arts and refuse of Arcadias and romances, without being able to discern the affront rather than the worship of such an ethnic prayer. But leaving what might justly be offensive to God, it was a trespass also more than usual against human right, which commands, that every author should have the property of his own work reserved to him after death, as well as living. Many princes have been rigorous in laying taxes on their subjects by the head, but of any king heretofore that made a levy upon their wit, and seized it as his own legitimate, I have not whom beside to instance. True it is, I looked rather to have found him gleaning out of books written purposely to help devotion. And if in likelihood he have borrowed much more out of prayerbooks than out of pastorals, then are these painted feathers, that set him off so gay among the people, to be thought few or none of them his own. But it from his divines he have borrowed nothing, nothing out of all the magazine, and the rheum of their mellifluous prayers and meditations let them who now mourn for him as for Tamuz, them who howl in their pulpits, and by their howling declare themselves right wolves, remember and consider in the midst of their hideous faces, when they do only not cut their flesh from him like those rueful priests whom Elijah mocked; that he who was once their Ahab, now their Josiah, though feigning outwardly to reverence churchmen, yet here hath so extremely set at naught both them and their praying faculty, that being at a loss himself what to pray in captivity, he consulted neither with the liturgy, nor with the directory, but neglecting the huge fardel of all their honeycomb devotions, went directly where he doubted not to find better praying to his mind with Pamela, in the Countess’s Arcadia. What greater argument of disgrace and ignominy could have been thrown with cunning upon the whole clergy, than that the king, among all his priestery, and all those numberless volumes of their theological distillations not meeting with one man or book of that coat that could befriend him with a prayer in captivity, was forced to rob Sir Philip and his captive shepherdess of their heathen orisons to supply in any fashion his miserable indigence, not of bread, but of a single prayer to God? I say therefore not of bread, for that want may befall a good man and yet not make him totally miserable: but he who wants a prayer to beseech God in his necessity, it is inexpressible how poor he is; far poorer within himself than all his enemies can make him. And the unfitness, the indecency of that pitiful supply which he sought, expresses yet further the deepness of his poverty.

Thus much be said in general to his prayers, and in special to that Arcadian prayer used in his captivity; enough to undeceive us what esteem we are to set upon the rest.

For he certainly, whose mind could serve him to seek a Christian prayer out of a pagan legend, and assume it for his own, might gather up the rest God knows from whence; one perhaps out of the French Astræa, another out of the Spanish Diana; Amadis and Palmerin could hardly scape him. Such a person we may be sure had it not in him to make a prayer of his own, or at least would excuse himself the pains and cost of his invention so long as such sweet rhapsodies of heathenism and knight-errantry could yield him prayers. How dishonourable then, and how unworthy of a Christian king, were these ignoble shifts to seem holy, and to get a saintship among the ignorant and wretched people; to draw them by this deception, worse than all his former injuries, to go a whoring after him? And how unhappy, how forsook of grace, and unbeloved of God that people, who resolve to know no more of piety or of goodness, than to account him their chief saint and martyr, whose bankrupt devotion came not honestly by his very prayers; but having sharked them from the mouth of a heathen worshipper, (detestable to teach him prayers!) sold them to those that stood and honoured him next to the Messiah, as his own heavenly compositions in adversity, for hopes no less vain and presumptuous (and death at that time so imminent upon him) than by these goodly relics to be held a saint and martyr in opinion with the cheated people!

And thus far in the whole chapter we have seen and considered, and it not but be clear to all men, how, and for what ends, what concernments and necessities, the late king was no way induced, but every way constrained, to call this last parliament; yet here in his first prayer he trembles not to avouch as in the ears of God, “That he did it with an upright intention to his glory, and his people’s good:” of which dreadful attestation, how sincerely meant, God, to whom it was avowed, can only judge, and he hath judged already, and hath written his impartial sentence in characters legible to all Christendom; and besides hath taught us, that there be some, whom he hath given over to delusion, whose very mind and conscience is defiled; of whom St. Paul to Titus makes mention.

II. Upon The Earl of Strafford’s Death.

This next chapter is a penitent confession of the king, and the strangest, if it be well weighed, that ever was auricular. For he repents here of giving his consent, though most unwillingly, to the most seasonable and solemn piece of justice, that had been done of many years in the land: but his sole conscience thought the contrary. And thus was the welfare, the safety, and within a little the unanimous demand of three populous nations, to have attended still on the singularity of one man’s opinionated conscience; if men had always been so to tame and spiritless, and had not unexpectedly found the grace to understand, that, if his conscience were so narrow and peculiar to itself, it was not fit his authority should be so ample and universal over others: for certainly a private conscience sorts not with a public calling, but declares that person rather meant by nature for a private fortune.

And this also we may take for truth, that he, whose conscience thinks it sin to put to death a capital offender, will as oft think it meritorious to kill a righteous person. But let us hear what the sin was, that lay so sore upon him, and, as one of his prayers given to Dr. Juxton testifies, to the very day of his death; it was his signing the bill of Strafford’s execution; a man whom all men looked upon as one of the boldest and most impetuous instruments that the king had, to advance any violent or illegal design. He had ruled Ireland, and some parts of England, in an arbitrary manner; had endeavoured to subvert fundamental laws, to subvert parliaments, and to incense the king against them; he had also endeavoured to make hostility between England and Scotland; he had counselled the king, to call over that Irish army of papists, which he had cunningly raised, to reduce England, as appeared by good testimony then present at the consultation: for which, and many other crimes alleged and proved against him in twenty-eight articles, he was condemned of high treason by the parliament. The commons by far the greater number cast him: the lords, after they had been satisfied in a full discourse by the king’s solicitor, and the opinions of many judges delivered in their house, agreed likewise to the sentence of treason. The people universally cried out for justice. None were his friends but courtiers and clergymen, the worst at that time, and most corrupted sort of men; and court ladies, not the best of women; who, when they grow to that insolence as to appear active in state-affairs, are the certain sign of a dissolute, degenerate, and pusillanimous commonwealth. Last of all the king, or rather first, for these were but his apes, was not satisfied in conscience to condemn him of high treason; and declared to both houses, “that no fears or respects whatsoever should make him alter that resolution founded upon his conscience:” either then his resolution was indeed not founded upon his conscience, or his conscience received better information, or else both his conscience and this his strong resolution strook sail, notwithstanding these glorious words, to his stronger fear; for within a few days after, when the judges at a privy council and four of his elected bishops had picked the thorn out of his conscience, he was at length persuaded to sign the bill for Strafford’s execution. And yet perhaps, that it wrung his conscience to condemn the earl of high treason is not unlikely; not because he thought him guiltless of highest treason, had half those crimes been committed against his own private interest or person, as appeared plainly by his charge against the six members; but because he knew himself a principal in what the earl was but his accessory, and thought nothing treason against the commonwealth, but against himself only.

Had he really scrupled to sentence that for treason, which he thought not treasonable, why did he seem resolved by the judges and the bishops? and if by them resolved, how comes the scruple here again? It was not then, as he now pretends, “the importunities of some, and the fear of many,” which made him sign, but the satisfaction given him by those judges and ghostly fathers of his own choosing. Which of him shall we believe? for he seems not one, but double; either here we must not believe him professing that his satisfaction was but seemingly received and out of fear, or else we may as well believe that the scruple was no real scruple, as we can believe him here against himself before, that the satisfaction then received was no real satisfaction. Of such a variable and fleeting conscience what hold can be taken? But that indeed it was a facile conscience, and could dissemble satisfaction when it pleased, his own ensuing actions declared; being soon after found to have the chief hand in a most detested conspiracy against the parliament and kingdom, as by letters and examinations of Percy, Goring, and other conspirators came to light; that his intention was to rescue the earl of Strafford, by seizing on the Tower of London; to bring up the English army out of the North, joined with eight thousand Irish papists raised by Strafford, and a French army to be landed at Portsmouth, against the parliament and their friends. For which purpose the king, though requested by both houses to disband those Irish papists, refused to do it, and kept them still in arms to his own purposes. No marvel then, if, being as deeply criminous as the earl himself, it stung his conscience to adjudge to death those misdeeds, whereof himself had been the chief author: no marvel though instead of blaming and detesting his ambition, his evil counsel, his violence, and oppression of the people, he fall to praise his great abilities; and with scholastic flourishes beneath the decency of a king, compares him to the sun, which in all figurative use and significance bears allusion to a king, not to a subject: no marvel though he knit contradictions as close as words can lie together, “not approving in his judgment,” and yet approving in his subsequent reason all that Strafford did, as “driven by the necessity of times, and the temper of that people;” for this excuses all his misdemeanors. Lastly, no marvel that he goes on building many fair and pious conclusions upon false and wicked premises, which deceive the common reader, not well discerning the antipathy of such connexions: but this is the marvel, and may be the astonishment, of all that have a conscience, how he durst in the sight of God (and with the same words of contrition wherewith David repents the murdering of Uriah) repent his lawful compliance to that just act of not saving him, whom he ought to have delivered up to speedy punishment; though himself the guiltier of the two. If the deed were so sinful, to have put to death so great a malefactor, it would have taken much doubtless from the heaviness of his sin, to have told God in his confession, how he laboured, what dark plots he had contrived, into what a league entered, and with what conspirators, against his parliament and kingdoms, to have rescued from the claim of justice so notable and so dear an instrument of tyranny; which would have been a story, no doubt, as pleasing in the ears of Heaven, as all these equivocal repentances. For it was fear, and nothing else, which made him feign before both the scruple and the satisfaction of his conscience, that is to say, of his mind: his first fear pretended conscience, that he might be borne with to refuse signing; his latter fear, being more urgent, made him find a conscience both to sign, and to be satisfied. As for repentance, it came not on him till a long time after; when he saw “he could have suffered nothing more, though he had denied that bill.” For how could he understandingly repent of letting that be treason which the parliament and whole nation so judged? This was that which repented him, to have given up to just punishment so stout a champion of his designs, who might have been so useful to him in his following civil broils. It was a worldly repentance, not a conscientious; or else it was a strange tyranny, which his conscience had got over him, to vex him like an evil spirit for doing one act of justice, and by that means to “fortify his resolution” from ever doing so any more. That mind must needs be irrecoverably depraved, which, either by chance or importunity, tasting but once of one just deed, spatters at it, and abhors the relish ever after. To the scribes and Pharisees woe was denounced by our Saviour, for straining at a gnat and swallowing a camel, though a gnat were to be strained at: but to a conscience with whom one good deed is so hard to pass down as to endanger almost a choking, and bad deeds without number, though as big and bulky as the ruin of three kingdoms, go down currently without straining, certainly a far greater woe appertains. If his conscience were come to that unnatural dyscrasy, as to digest poison and to keck at wholesome food, it was not for the parliament, or any of his kingdoms, to feed with him any longer. Which to conceal he would persuade us, that the parliament also in their conscience escaped not “some touches of remorse” for putting Strafford to death, in forbidding it by an after-act to be a precedent for the future. But, in a fairer construction, that act implied rather a desire in them to pacify the king’s mind, whom they perceived by this means quite alienated: in the mean while not imagining that this after-act should be retorted on them to tie up justice for the time to come upon like occasion, whether this were made a precedent or not, no more than the want of such a precedent, if it had been wanting, had been available to hinder this.

But how likely is it, that this after-act argued in the parliament their least repenting for the death of Strafford, when it argued so little in the king himself: who, notwithstanding this after-act, which had his own hand and concurrence, if not his own instigation, within the same year accused of high treason no less than six members at once for the same pretended crimes, which his conscience would not yield to think treasonable in the earl: so that this his subtle argument to fasten a repenting, and by that means a guiltiness of Strafford’s death upon the parliament, concludes upon his own head; and shows us plainly, that either nothing in his judgment was treason against the commonwealth, but only against the king’s person; (a tyrannical principle!) or that his conscience was a perverse and prevaricating conscience, to scruple that the commonwealth should punish for treasonous in one eminent offender that which he himself sought so vehemently to have punished in six guiltless persons. If this were “that touch of conscience, which he bore with greater regret” than for any sin committed in his life, whether it were that proditory aid sent to Rochel and religion abroad, or that prodigality of shedding blood at home, to a million of his subjects’ lives not valued in comparison to one Strafford; we may consider yet at last, what true sense and feeling could be in that conscience, and what fitness to be the master conscience of three kingdoms.

But the reason why he labours, that we should take notice of so much “tenderness and regret in his soul for having any hand in Strafford’s death,” is worth the marking ere we conclude: “he hoped it would be some evidence before God and man to all posterity, that he was far from bearing that vast load and guilt of blood” laid upon him by others: which hath the likeness of a subtle dissimulation; bewailing the blood of one man, his commodious instrument, put to death most justly, though by him unwillingly, that we might think him too tender to shed willingly the blood of those thousands whom he counted rebels. And thus by dipping voluntarily his finger’s end, yet with show of great remorse, in the blood of Strafford, whereof all men clear him, he thinks to scape that sea of innocent blood, wherein his own guilt inevitably hath plunged him all over. And we may well perceive to what easy satisfactions and purgations he had inured his secret conscience, who thought by such weak policies and ostentations as these to gain belief and absolutions from understanding men.

III. Upon his going to the House of Commons.

Concerning his unexcusable and hostile march from the court to the house of commons, there needs not much be said; for he confesses it to be an act, which most men, whom he calls “his enemies,” cried shame upon, “indifferent men grew jealous of and fearful, and many of his friends resented, as a motion arising rather from passion than reason:” he himself, in one of his answers to both houses, made profession to be convinced, that it was a plain breach of their privilege; yet here, like a rotten building newly trimmed over, he represents it speciously and fraudulently, to impose upon the simple reader; and seeks by smooth and supple words not here only, but through his whole book, to make some beneficial use or other even of his worst miscarriages.

“These men,” saith he, meaning his friends, “knew not the just motives and pregnant grounds with which I thought myself furnished;” to wit, against the five members, whom he came to drag out of the house. His best friends indeed knew not, nor could ever know, his motives to such a riotous act; and had he himself known any just grounds, he was not ignorant how much it might have tended to his justifying, had he named them in this place, and not concealed them. But suppose them real, suppose them known, what was this to that violation and dishonour put upon the whole house, whose very door forcibly kept open, and all the passages near it, he beset with swords and pistols cocked and menaced in the hands of about three hundred swaggerers and ruffians, who but expected, nay audibly called for, the word of onset to begin a slaughter?

“He had discovered, as he thought, unlawful correspondences, which they had used, and engagements to embroil his kingdoms;” and remembers not his own unlawful correspondences and conspiracies with the Irish army of papists, with the French to land at Portsmouth, and his tampering both with the English and Scots army to come up against the parliament: the least of which attempts, by whomsoever, was no less than manifest treason against the commonwealth.

If to demand justice on the five members were his plea, for that which they with more reason might have demanded justice upon him, (I use his own argument,) there needed not so rough assistance. If he had “resolved to bear that repulse with patience,” which his queen by her words to him at his return little thought he would have done, wherefore did he provide against it with such an armed and unusual force? but his heart served him not to undergo the hazard that such a desperate scuffle would have brought him to. But wherefore did he go at all, it behoving him to know there were two statutes, that declared he ought first to have acquainted the parliament, who were the accusers, which he refused to do, though still professing to govern by law, and still justifying his attempts against law? And when he saw it was not permitted him to attaint them but by a fair trial, as was offered him from time to time, for want of just matter which yet never came to light, he let the business fall of his own accord; and all those pregnancies and just motives came to just nothing.

“He had no temptation of displeasure or revenge against those men:” none but what he thirsted to execute upon them, for the constant opposition which they made against his tyrannous proceedings, and the love and reputation which they therefore had among the people; but most immediately, for that they were supposed the chief, by whose activity those twelve protesting bishops were but a week before committed to the Tower.