Thomas Mackay, A Policy Of Free Exchange: Essays By Various Writers on the Economical and Social Aspects of Free Exchange and Kindred Subjects (1894)

|

|

| Thomas Mackay (1849–1912) |

Source

Thomas Mackay, A Policy Of Free Exchange: Essays By Various Writers on the Economical and Social Aspects of Free Exchange and Kindred Subjects. Edited By Thomas Mackay (New York: D. Appleton And Co., 1894).

Table of Contents

- PREFACE

- SYNOPSIS OF CONTENTS

- ESSAYS AND CONTRIBUTORS

- I. HENRY DUNNING MAC LEOD, The Science of Economics and its relation to Free Exchange and Socialism

- II. WILLIAM MAITLAND, The Coming Industrial Struggle

- III. ST. LOE STRACHEY, National Workshops

- IV. The HON. J. W. FORTESCUE, State Socialism and the Collapse in Australia

- V. WYNNARD HOOPER, The Influence of State Borrowing on Commercial Crises

- VI. W. M. ACWORTH, The State in Relation to Railways

- VII. THOMAS MACKAY, The Interest of the Working Class in Free Exchange

- VIII. BERNARD MALLET, The Principle of Progression in Taxation

- IX. The HON. ALFRED LYTTELTON, The Law of Trade Combinations

Text

'LET not the people—I mean the masses—think lightly of those great principles upon which their strength wholly rests. The privileged and usurping few may advocate expediency in lieu of principles, but depend upon it we, reformers, must cling to first principles, and be prepared to carry them out, fearless of consequences…. I yield to no man in the world (be he ever so stout an advocate of the Ten Hours Bill) in a hearty good-will towards the great body of the working classes; but my sympathy is not of that morbid kind which would lead me to despond over their future prospects. Nor do I partake of that spurious humanity which would indulge in an unreasoning kind of philanthropy at the expense of the independence of the great bulk of the community. Mine is that masculine species of charity which would lead me to inculcate in the minds of the labouring classes the love of independence, the privilege of self-respect, the disdain of being patronised or petted, the desire to accumulate, and the ambition to rise. I know it has been found easier to please the people by holding out flattering and delusive prospects of cheap benefits to be derived from Parliament rather than by urging them to a course of self-reliance; but, while I will not be the sycophant of the great, I cannot become the parasite of the poor; and I have sufficient confidence in the growing intelligence of the working classes to be induced to believe that they will now be found to contain a great proportion of minds, sufficiently enlightened by experience to concur with me in the opinion that it is to themselves alone individually that they, as well as every other great section of the community, must trust for working out their own regeneration and happiness. Again I say to them Look not to Parliament, look only to yourselves.'—From a Letter of Richard Cobden, dated October 21,1836.

PREFACE.

THE articles contained in this volume have been written by the various authors independently. For the title, the preface, and for such general argument as is to be found in the book as a whole, no responsibility necessarily attaches to the writers, who are answerable each for his own contribution and for that only.

The title suggests that the principle of Free Exchange is capable of inspiring a constructive policy, in which freedom is limited only by a mutual respect for the freedom of all, that is, by the reciprocal responsibility inherent in every voluntary act of Exchange: the articles have been arranged, as far as possible, according to the natural sequence of thought; and for this attempt to give an appearance of unity of design the Editor is alone responsible.

The first paper, from the pen of Mr. H. D. Mac Leod, gives an historical sketch of the course of economic speculation with regard to the doctrine and policy of Free Exchange. He traces the rise of freedom of internal and international trade from the teaching of the French Economists and Adam Smith, and points out how the misconceptions of Ricardo and his followers on the subject of value have led mankind astray, and confused in the most mischievous manner all our ideas on the economic mechanism of society.

Free Trade, he argues, is the first great benefit which just economic reasoning has conferred on this country. The task before this and the next generation must be the clear establishment of the truth that a largely increased production of wealth and its equitable distribution among all classes of the population can be attained only by developing the facility and the multiplicity of exchange—in other words, by Free Exchange; and, further, that this rule is applicable to all forms of value, whether they be labour or credits or material commodities.

Mr. Maitland draws attention to a problem of the immediate future. The adoption of Free Trade by America will produce, without doubt, great industrial changes. If we are to retain our markets, in face of the decreased cost of production which this policy will permit in America, we must cast off from us all unnecessary burdens and all unnecessary restrictions. Mr. Maitland's argument is designed to show that our political leaders are very little alive to the reality of this danger. Changes such as he forecasts can only be met by permitting the principle of Free Exchange to be the distributor both of capital and labour. It is one of the evil consequences of Protection that, even when men become persuaded of its injustice and folly, they cannot return to Free Trade without causing considerable economic disturbance. We are about to encounter an industrial crisis arising from this cause; and it is Mr. Maitland's argument that such redistribution of the industrial markets, as is inevitable, will come on us more gradually and with less suffering, if we accept the principle of Free Exchange in every relation of life. Thus encountered, the process of change need have for us no terror, for it must ultimately lead to an ever-increasing satisfaction of human wants at an ever-decreasing expenditure of human exertion.

Mr. Strachey gives an account of the Ateliers Nationaux of Paris in 1848. The attempt was there made to give labour a right to force the community to purchase it for wages. This violation of the principle of Free Exchange rapidly—in three months' time—produced anarchy and revolution.

Mr. Fortescue's paper deals with a somewhat similar attempt in our own Colonies to carry on civilization by that vast system of public works which is most briefly described under the term State Socialism.

Another aspect of the same problem is treated by Mr. Hooper from the purely financial point of view. The pledging of the credit of taxpayers for government borrowing and government trading is a contravention, possibly in many cases a necessary contravention, of the principle of Free Exchange. Mr. Hooper shows how treacherous a basis for the expansion of industry this method affords, and how readily it lends itself to the creation of disastrous financial complications.

Mr. Acworth deals with the vexed question of State-interference in railway management. He shows what a limited amount of truth there is in the allegation that a railway is a monopoly. On the important question of tariff legislation, subject to the necessity of State-interference legislative, judicial, and executive for the purpose of preventing undue preferences and unreasonable discriminations, he is disposed to leave the public and the railways to deal with each other on the principle of Free Exchange. In most other respects he suggests that more advantage will be gained by an enforcement of publicity than from any other form of regulation. Just as in the great Free Trade controversy, the maxim was laid down that a hostile tariff is best combatted by a more thorough free trade, so Mr. Acworth argues that the difficulties arising out of an alleged monopoly, like a railway, are best overcome, not by turning it into a real monopoly in the hands of a government department, but by subjecting it as far as possible to the health-giving influence of publicity and Free Exchange.

Mr. Mackay's paper deals with the principle of Free Exchange in its relation to the property of the working classes in their own labour and in their own savings. The argument seeks to justify the opinion that Free Exchange is capable of becoming to labour what a right of free mintage is to bullion, viz. a certain guarantee of employment and wages; further that, in the vast series of exchanges which constitute the economic mechanism of a free community, the value of labour must unceasingly tend to enhancement. It is, therefore, to the organizing influence of Free Exchange that labour has to look for the realization of its legitimate ambition.

Here the controversial portion of the volume may be said to end. The two papers which follow, though not, strictly speaking, covered by the title, have a relevance which is sufficiently obvious. Mr. Mallet's paper is a theoretical discussion of one aspect of the interesting problem of taxation. The principle of progression or graduation has been already, as he points out, either avowedly or unconsciously adopted in the financial system of most civilized countries, and its extension is to be looked for in the future. Unless the theory be deliberately adopted that taxation is to be used as a lever for redressing the inequalities of fortune between the different classes of a community, there is, he thinks, much exaggeration both in the fears and in the hopes which this proposal evokes. In the distinction, as stated by Jevons, between value and utilities, he finds a defence of a progressive as opposed to a merely proportional rate of taxation; but he shows that at a point, which can only be discovered by actual experiment, the abstraction by the State of the surplus wealth of individuals may become not merely a deduction from the wealth of a country, but a positive bar to its further growth; further, that taxation is just and politic when it aims at equalizing the sacrifice imposed on individuals, but that it is the reverse when it seeks to equalize incomes.

Mr. Lyttelton, in explaining the state of the law with regard to trade combinations, has adhered strictly to the legal aspect of the question. If there is any force in the argument contained elsewhere in the book that, as regards labour as well as all other forms of wealth, Free Exchange, and not coercive combination, should be our rule of guidance, it is obvious that an estimate of the intricacies of the law of trade combinations is an interesting and pertinent addition to the controversy, even though, as in this case, the writer confines himself to a statement of fact, and takes no responsibility for the general argument in which his narrative may serve as an illustration.

THOMAS MACKAY.

SYNOPSIS OF CONTENTS.

I. THE SCIENCE OF ECONOMICS AND ITS RELATION TO FREE EXCHANGE AND SOCIALISM.

- Present chaotic condition of economic speculation, its cause, due to neglect of proper definition of the subject-matter of a Science. Adam Smith not the founder of Economics and Free Trade. Political Science due, like medicine, to the sufferings of mankind, its birthplace was France

- Early attention paid to theory of money, but true principle of trade much misunderstood

- The sect of the 'Economists.' Their opinions, their contention in favour of Free Trade

- An abstract of their doctrine, establishing Liberty and the right of Property as fundamental principles of civilized society

- Their doctrine concerning commerce; their assertion that exchangeability is the essence of wealth; their denial of the title of wealth to labour and credit, the error of this exclusion demonstrated

- The service rendered by the Economists in exposing the fallacy of the Balance of Trade doctrine that in every exchange one side was a loser

- Their opinion that neither side lost or gained; that labour engaged in agriculture was the only productive labour; all other labour sterile and unproductive

- Such doctrine provocative of reaction. Adam Smith and Condillac show that in commerce both sides gain, the immense importance of this demonstration

- Adam Smith's further criticism of the Economists shows the error of confining term wealth to material products of the earth; he includes labour and credit in the category of wealth, but later on loses sight of this, and proposes various irreconcileable definitions

- The confusion introduced by J. B. Say's adoption and misconstruction of one expression of the Economists; 'Production, Distribution, and Consumption'

- J. S. Mill the disciple of Say. His definitions of wealth, their inconsistency. In the hands of Say and Mill the science brought to an impasse

- Summary of the bearing of doctrine of Economists and Adam Smith on Free Trade; various infringements of Free Trade considered and shown to be robbery. Protection, Slavery, the law of the 'Maximum,' all are forms of Socialism

- Error of supposing that England should abandon Free Trade because other nations have not adopted it. 'If one tariff is bad, two are worse'

- Next, the relation of economic speculation on socialism. This turns mainly on the definition of value

- The contradictory statements of Adam Smith, the true theory held by Economists and the ancients, error introduced by Locke. Adam Smith's doctrine considered at length, his hopeless attempt to make labour an invariable standard of value, its inadequacy demonstrated

- The same confusion throughout Ricardo, his dogma that labour is the foundation of all value, its obvious untruth

- McCulloch and Carey take the same view

- The importance of this doctrine consists in the fact that it is made the foundation of socialism

- The doctrine that working men are the creators of all wealth and value tested by ten examples

- Credit, its nature, and the obvious absurdity of saying that working men have given it its value

- Credit is a mass of exchangeable property, in the creation of which manual labour has had absolutely nothing to do

- The alleged equity of socialism based on the Ricardian doctrine of value is thus disproved

- Labour has value, as being exchangeable, and there is no reason to withdraw it from the operation of the principle of Free Exchange, which is at once equitable and beneficent

- Conclusion that the basis of value is exchangeability, and that the chaotic state of Economics is due to the neglect of this principle

II. THE COMING INDUSTRIAL STRUGGLE.

- The inaugural address of President Cleveland suggests that the Manchester school, if dead in England, has come to life again in the United States

- America the only really protectionist state. The policy has failed, and a new era is beginning

- In England, on the contrary, we are retracing our steps and returning to protection

- The object of this paper to forecast the result of this policy in the two countries

- The view of President Cleveland contrasted with that of English politicians: quotations from his inaugural address and from speeches by Sir William Harcourt, Mr. Arnold Morley, Sir John Gorst, Mr. Campbell Bannerman, Mr. John Burns

- President Cleveland's policy the beginning of the end of protection. Opinion that this will enable us to compete successfully with American manufacturers entirely erroneous. The reduction of cost of production in America will, for the first time, make their competition formidable to us

- Some of the conditions of English and American manufacture considered

- American high wages, under present conditions, exaggerated. Probability that with free trade they will rise and take from us our skilled labour

- The change of policy in America to be regarded with equanimity if we were adhering to free trade

- Still we are in possession—only our own criminal folly can rob us of it

- Looking at home, there is much to disquiet us—politicians doling out protection to secure votes. Policy of Mr. Bright and Lord Shaftesbury compared

- Mr. Chamberlain reintroduces protection under the alias of constructive legislation. Mr. Burns on 'reproductive' work

- Scepticism of Socialists or Protectionists as to progress, as illustrated by State pension proposals

- American protection an object lesson: a corrupt policy of Give, give, with burden falling ultimately on agricultural class, and in the end general exasperation and collapse.

- In England the burden is to be put on the capitalist class, with the result that capital will be destroyed or forced to emigrate.

- Mr. Chamberlain fears the competition of a free trade Ireland, but not of a free trade America

- American labour troubles, protests against artificial or protective monopoly

- Mr. John Burns' admission of the hopelessness of labour protection

- Impossibility of walling-in a country or a trade without ruin to its best interests

- Expectation that wages will advance in a free market justified by experience

- Necessity of a policy of retrenchment: burden of war preparations and foreign policy; the enviable position of America

- Position of the Colonies

- The problem before a nation dependent like England on foreign trade—necessity for economical public administration

- A market set free from the dread of labour troubles and the burden of vexatious taxation would retain capital buried in hopeless enterprises in Argentina, Africa, and elsewhere

- President Cleveland and Sir William Harcourt typical of the views of their countrymen. Summary of the situation

- Hope expressed that we may be warned in time by the obviousness of the danger

III. NATIONAL WORKSHOPS.

- I. Socialistic theories of nationalization and municipalization to be tested by facts

- The national workshops of 1848 an experiment in this direction

- Hence their importance and relevancy in any consideration of socialistic principles

- II. The national workshops a deliberate and bona fide attempt to put socialistic principles in practice

- As proved by the text of the Decree

- III. Louis Blanc, a convinced Socialist, at the head of the experiment; the superintendence entrusted to Émile Thomas, a practical man of business, though not a Socialist

- Louis Blanc armed with practically absolute powers

- IV. Text of Decrees formulating the droit du travail and the Ateliers Nationaux

- V. The organization described

- VI. The evidence of the correspondent of the Economist

- Mr. Nassau Senior describes the work as an exact counterpart of the 'parish farm'

- Evidence of Victor Hugo and of M. Émile Thomas

- The result—insurrection, street-fighting, and 12,000 men shot in the streets

- VII. M. Thiers on another experiment in collectivism

- Report of surveyor on work of unemployed at Millbank

- VIII. English experience of parish farms and under old poor law very similar

- IX. Two solutions offered—that of the Socialists and that of the advocates of Free Exchange

- X. A plain summary of the case against Socialism

IV. STATE SOCIALISM AND THE COLLAPSE IN AUSTRALIA.

- Dr. Pearson's National Character, due to the inspiration of Australia

- His account of Australian State Socialism

- Its alleged success in Australia, the assumption that it is inevitable elsewhere

- The religion of the State as outlined by Dr. Pearson—it promises great good, but demands proportional sacrifices; it is omnipotent, it is never inexorable; it bestows benefits freely; its use of statistics as an advertisement and a liturgy

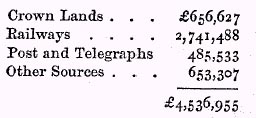

- The turn of the tide—imaginary surpluses detected. Statistical statement of the course of collapse

- Judged by the test of finance, State Socialism in Australia a failure

- The time has now come to 'demand proportional sacrifices'

- Will the 'demand' be answered. The earlier example of New Zealand

- The exodus of the taxpayer; the absentee debtor. The prayer of the State religion has two clauses—'Give us our daily bread, and forgive us our debts'

- The case of those who must remain considered: the salaried official, the first victims of retrenchments; the public service discouraged

- The people on the land, being unorganized, their share of pillage has been less than that of the town dwellers, and their burden from protective tariffs more oppressive—on them the bill for 'proportional sacrifices' now falls

- An awkward and disagreeable awakening for the agricultural class, the true workers of the colony; their natural resentment at garbled accounts, delusive assertions as to reproductive public works; labourers diverted from agricultural industry by artificial work in the towns by means of borrowed money

- The State in its perplexity has recourse to various doubtful financial expedients

- Conclusion that, financially, State Socialism has failed, benefits have been squandered, and the obligations of the taxpayer strained to the verge of repudiation, new oppressive and arbitrary taxation has been imposed on the industrious, gambling has been encouraged, and a low tone of commercial morality has grown up

- The ethics of public life too have suffered. The adventures of Sir G. Dibbs

- The decay of parental authority under the educational policy of the State

- State Socialism has corrupted the national character—a fact all the more lamentable in view of the nobler early traditions of the country, and of the necessity of basing recuperation on national character

- The prospects of State Socialism elsewhere. In Australia it has been carried out at the expense of the British capitalist. In Europe it must be based on the taxation of the successful

- Can the system endure? it can make beggars, but not one millionaire, and must end in bankruptcy; then comes a revulsion of feeling, when it is too late

- Yet it seems inevitable that State Socialism will come and be the death-cry of our civilization

V. THE INFLUENCE OF STATE BORROWING ON COMMERCIAL CRISES.

- Commercial crisis, a general definition

- Certain well-marked characteristics to be further described

- Inflation and collapse, followed by long period of inactivity and liquidation

- The peculiar position of the banker, who (unlike other traders) is always a debtor, on balance; his need for careful choice of 'securities'

- The Buenos Ayres waterworks and the Barings. The collapse due to the rash engagements of the firm and the refusal of the investing public to support it

- The Baring and Overend catastrophes compared. Popular belief in the ability of foreign governments to create 'productive works,' the cause of much ill-considered lending

- There will always be speculation; the security of a well-planned industrial undertaking better than the security based on excessive taxation. Abuse of State guarantee

- The tendency of politicians to find excuse for extending the sphere of State action. From 1820 to 1870 the country was freeing itself from many mischievous forms of State-interference. The present reaction not yet gone very far

- The present inquiry confined to the financial consequences of this policy. Method of raising capital in London market

- The case of a foreign or colonial government raising a loan for 'productive public work;' the inflation of trade, the demand artificially created ceases. The illustration of Argentina

- Natural that Great Britain should advance capital to new countries; objection to this being done through Government loans

- Greater safety of a more gradual development through the application of capital by private enterprise

- Argument that instruments of production should be in hands of government involves a mistaken view of functions of government. Young countries may try experiments, but the fact of their youth will not prevent failure

- The capitalists of Great Britain the principal creditors of the world. A breakdown in any one country therefore alarms and paralyzes credit all over the world

- Summary of reasons why government borrowings are more likely to draw countries into difficulty than private borrowings: (1) Government borrows more than necessary; (2) the money does not go so far; (3) its credit, depending on the taxation of its subjects, being greater, its power to throw good money after bad much less limited, hence chance of larger collapse

- Too ready belief of borrowers of their ability to pay, and carelessness of issuing finance houses, combine to make a certain danger; the promise of a government not always a good guarantee

- Economic objection to loans at home to enable government to carry on public works, one or two instances mentioned

- Conclusion, that the present tendency to increase the interference of government in matters relating to trade and commerce ought to be diminished

VI. THE STATE IN RELATION TO RAILWAYS.

- The relation of the State to railways may take one of five forms

- Two forms may at once be excluded

- A third, viz. State ownership of railways which are let out to be worked by private enterprise, now out of fashion in this country, though favoured at one time by Sir Rowland Hill, adopted in Italy, in Holland, and in a sense in France

- In England there are left two possible methods—State ownership and private ownership under State control

- Wide ramifications of the subject

- Objections alleged against our present system considered and answered—waste of competition, bloated dividends a tax on trade, unwillingness to make concessions, granting of undue preference, occasional effete or incompetent management

- Arguments in favour of State ownership considered and appreciated; State should own monopolies; economy in rate of interest on capital due to superior credit of State, also due to unification of management; State would work railways for the benefit of community

- Would-be reformers unable to agree as to principle on which rates are to be based

- The matter not to be decided by a priori arguments but by observation of practical experiment. Some of the State-managed railways of the continent the worst in the world. Railways of Baden, Belgium, Prussia, Australia

- The result summed up: (1) State management does not reduce the price of services; (2) Management more costly; (3) and danger of political corruption great

- State management of Post Office criticized

- Admitting that State railways are undesirable, the limits and occasions of State control have next to be considered, under two heads—(1) as affecting public safety, (2) as regulating tariffs

- The first of these turns on the interpretation, in each case, of the old maxim, Sic utere tuo ut alienum non laedas. construction of new lines, compulsory dispossession of owners, promoters to show that they have sufficient prospect of financial support, publicity of accounts. Level crossings, signalling, interlocking, &c.

- The crucial point, however, is tariff regulation, necessary within certain limits

- Justification of State control considered, on the ground that a railway is a monopoly; that it has acquired property by compulsory powers; that the authorizing Act of Parliament secured, by way of bargain, certain advantages to the public

- Hence maximum rates, their futility as a means of securing free contract and equality of charges. Difficulty of applying the principle

- The controversy as to what constitutes undue preference considered

- 'Personal discriminations' unknown in England. Discriminations favouring special classes of goods and special localities frequent

- The difficulties to be overcome by any tribunal for the regulation of rates

- Conclusion that the authority of the Executive cannot beneficially undertake much more than purveying information.—Mr. Justice Wills, on the danger of ill-considered innovations

- Experience in this country and in the United States confirm these views

- Satisfactory result of 'publicity' in Massachusetts

- Summary of results. State ownership undesirable. State control unavoidable. General conclusion in favour of the present system. With publicity 'the eventual supremacy of an enlightened public opinion' is matter of certainty—on this we must rely

VII. THE INTEREST OF THE WORKING CLASS IN FREE EXCHANGE.

- The property of a man in his own person the origin and foundation of all other property

- As necessary corollary from this follows the right of the free exchange of labour and of the wages of labour

- No need to discuss questions of prehistoric title. Modern title to property rests on legal acts of exchange

- The influence of Free Exchange in the economic organization of society limited, but still operative; civilization means the extension of that influence

- The purpose of the paper to consider the influence of Free Exchange as it affects the property which the labourer has (1) in his own labour, (2) in his own savings

- 1. Labour the poor man's most important possession

- General functions of a market. The labour market contrasted with the gold market. The appreciation of gold doubtful; the appreciation of labour obvious and certain. Free mintage means a continuous demand for gold. Free Exchange has a similar function to perform for labour

- The Malthusian fallacy that subsistence is limited, is analogous to the trade unionist fallacy that opportunities for labour are limited

- How far at present is Free Exchange acting as a free mintage for labour?

- The mobility of labour considered—some comfort to be found in progress already made

- The wages of domestic service considered—argument that Free Exchange and the bargain in detail have been beneficial and a cause of rising wages

- The modern trade unionist blind to the advantages of Free Exchange

- His objections considered—argument that better conditions of labour must come from an increase of exchangeable supply, i. e. the increased production of the proper things in their proper quantities and places

- This economical distribution of effort (i.e. labour and capital) to be effected only by Free Exchange

- Injustice and inexpediency of a compulsory minimum wage, the cause of the congestion of labour, known as the Unemployed problem

- Doubt expressed whether this coercive policy is conducive to the main object of trade unionism

- Other forms of restriction on Free Exchange. Municipal trading. Larger forms of enterprise claimed as the monopoly of Government; consequent congestion of capital and labour in the smaller industries

- The terms 'employable' and 'competent' considered. Free Exchange the necessary condition of the growth of these characteristics

- The art of capitalization, a form of exchange, the coping-stone of industrial competence

- Savings a cause of firmness in the labour market, contrasted with poor law relief, which has an opposite effect

- 2. The property of the poor man in his benefit society and savings bank considered

- Argument that saving is a process of exchange

- Illogical nature of the Socialist's dissent from a particular form of exchange

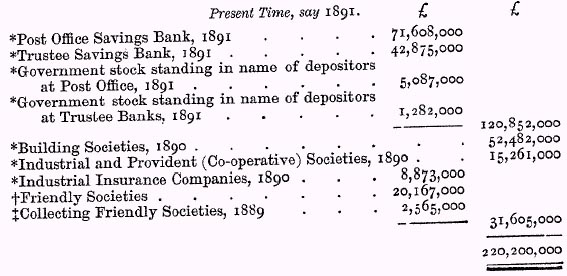

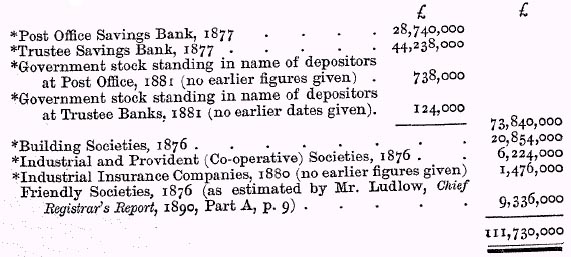

- The savings of the working class a practical refutation of collectivism

- Question of savings banks; comparison instituted between Government savings banks, commercial banks on the Scotch system, and co-operative banks in Germany and elsewhere

- A sound system of credit developed by banks compared to the fertilizing waters of the Nile

- Argument that these advantages can be secured to the labourer by co-operative banking

- Improvement in working class insurance under free competition

- Controversy in the co-operative movement between advocates of dividend-on-purchase and dividend-on-wages

- A neglected element in the co-operative theory. The most satisfactory co-operation is the subdivision and distribution of capital and labour in a free market

- M. Rostand's comparison of the sterile antagonism of Lassalle to the constructive beneficence of the life-work of one of our English co-operative worthies

VIII. THE PRINCIPLE OF PROGRESSION IN TAXATION.

- Two theories stated as to the legitimate purposes of taxation

- (1) For the sake of revenue necessary for economical administration of public services

- (2) For bringing about an equalization of incomes

- Desire for economy now less powerful than before, hence new schemes for raising revenue. Among others progressive or graduated taxation

- A preliminary question—What are the legitimate purposes of taxation?

- If theory (1) as above prevails, there will be no burdensome taxation for any class. If theory (2) be to any extent adopted, then progressive taxation may become a formidable weapon

- This preliminary question not here considered

- Object of paper to discuss (1) the abstract principle of progression, (2) its practical value as a method of taxation

- Taxation to be levied (1) in proportion to benefits enjoyed, or (2) according to ability to pay

- This last the view of Mill. Equality of sacrifice not realized when necessities of life were taxed, hence taxation of luxuries. A tax levied on property and income to some extent a recognition of the principle of graduation

- Its indirect recognition in this country; its popularity with the democracy

- The question therefore presses and deserves attention

- Mill argues that the 'same percentage' does not insure equality of sacrifice, recommends exemption of smaller incomes, but rejects graduation

- Mill's conclusions unsatisfactory

- The subject viewed from the stand-point of Jevons' theory of the distinction between utility and value. Statement of this theory, and a justification of the principle of progression based thereon

- Admitting the justice of the principle, other considerations to be taken into account: (1) variability of term 'luxuries' as between different classes of men and different times; (2) a satisfaction of a primary want, a step upward in the path of civilization; (3) Free Exchange daily bringing within the reach of the million what were formerly the luxuries of the great

- These considerations, pointing to the beneficence and levelling influence of wealth accumulating under a system of Free Exchange, suggest the necessity of a limit to the principle of progression

- Description of the nature of this limit

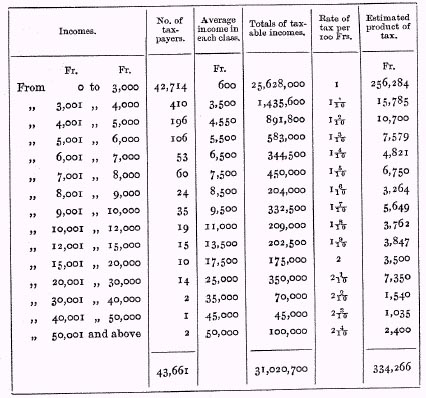

- Can an equitable rate of graduation be fixed?

- Justice of the exemption of the lower incomes

- Difficulty of fixing the scale of graduation for the higher incomes

- Next, is graduation satisfactory in practice?

- M. Leroy-Beaulieu in favour of a light and uniform tax

- Mr. Goschen and M. Leroy-Beaulieu quoted to show how large a proportion of the national income of civilized countries is in the hands of small proprietors

- Unproductive nature of progressive taxation—if excessive, it tends to defeat its object; if moderate, little more productive than uniform or proportional taxation

- Both fears and hopes with regard to this principle of taxation exaggerated. If used for equalizing taxation, and not for equalizing incomes, a useful adjunct to taxation

IX. THE LAW OF TRADE COMBINATIONS.

- Growth of combination in modern commerce

- Large companies and trusts press on the individual trader as Trade Unions do on the individual work-man

- The conflict apt to be oppressive. Necessity of preventing physical violence

- Early laws against combination, now out of harmony with modern ideas

- The scope of the article to discuss the question as affected (i) by the Criminal Law, and (ii) by the Civil Law

- (a) The Criminal Law as laid down in The Conspiracy and Protection of Property Act, 1875; the effect of this statute; sections 3 and 7 quoted; ambiguity of term 'intimidate;' its analogy with the Corrupt Practices Act, 1883; intimidation according to Mr. Justice Cave must include the threat of personal violence. The case of Gibson v. Lawson; of Curran v. Treleaven. Conclusion that the statute of 1875 leaves a very absolute power in the hands of trade combiantions

- (b) The Criminal Law as defined by the Common Law of Conspiracy; its scope and authority considered; possibility of its application in the case of Gibson v. Lawson; the exemption contained in section 3 of the statute of 1875 considered

- The remedy of the Civil Law. The Mogul Steam Ship Company v. McGregor, Gow & Co. The case of Temperton v. Russell

- The decisions in these two cases contrasted; suggestion that they are not governed by the same rule; probability that they will either be more clearly distinguished or the decision in one or other reversed

- Summary

I. HENRY DUNNING MAC LEOD, ON THE SCIENCE OF ECONOMICS AND ITS RELATION TO FREE EXCHANGE AND SOCIALISM.

ALL persons who are interested in the so-called science of Economics know only too well the melancholy and deplorable state into which it has fallen. It is such a chaos of contradictions that very many persons refuse to believe that there is any such science at all1.

The cause of this lamentable confusion is that there are fundamental concepts of it, which are wholly irreconcileable with each other, just as there have been in the earlier and imperfect stages of most other sciences, such as astronomy, optics, and many others.

A science is a body of phenomena all relating to a single fundamental general concept. Thus dynamics is the science which treats of the laws governing the phenomena of force; optics is the science of the laws governing the phenomena of light; and so on. Economics is often said to be the science of wealth. What, then, is wealth? What is that quality of things which constitutes them wealth? Economies can only be the science of the laws which govern the phenomena relating to that quality which constitutes things wealth.

It was long an assured opinion in this country that Adam Smith was the founder and creator of political economy and free trade. A once prominent politician is reported to have said that political economy and free trade sprang perfect and complete from the brain of Adam Smith, as Minerva did from the head of Jupiter. Such ideas, however, show a complete ignorance of the history of Economics, and are now quite abandoned by all persons who have studied the subject.

In fact, it is contrary to nature that it should be so. Great sciences are not created by a book. They invariably arise from small beginnings, just as the mighty Danube flows from a spring in the garden of a German burgher. Men begin to observe certain phenomena connected with some single general fundamental concept. Then others extend it to a larger number of phenomena based on the same concept: and so at last, by the contributions of an increasing number of observers, it grows into a great science, just as the Danube from a tiny spring is swollen into a mighty river by multitudes of tributary streams.

Every one with a scientific instinct can at once perceive that Adam Smith's work is pervaded by a combative air, that every part of it is evidently written at something preceding, and that it was intended to overthrow a prior system.

As a matter of fact, Economics was founded as a science by an illustrious sect of philosophers in France in the middle of the last century, who were the first to perceive and declare that there is a positive and definite science of Economics, based upon demonstrative reasoning, in the same way as the physical sciences.

The science of Economics, like medicine, has arisen out of the calamities and misery of mankind, caused by the violation of true economic principles; and every advance in economic theory has originated in some great pressing practical evil.

The first department of Economics to be reduced to scientific principles was that of money. Charlemagne caused the pound weight of silver to be adopted as the standard of money in all Western Europe; and he divided it into 240 pennies. The mediaeval sovereigns clipped, curtailed and debased their coinages, but declared that the clipped and debased coin should pass at the same value as good coin. Philip le Bel was particularly conspicuous for issuing debased coin, for which he was consigned to the Inferno by Dante. This degradation of the coin produced such intolerable evils and misery to the people that Charles V of France referred the matter to one of his councillors, Nicolas Oresme, who addressed to him a treatise on money, which may be said to stand at the head of modern Economics. In consequence of similar evils in Poland, Sigismund I requested Copernicus to draw up a treatise on the subject. This has recently been discovered and printed in the new edition of his works. These two treatises laid down the true principles of money, which are now accepted by all sound Economists.

For many centuries all governments enacted laws regarding trade without suspecting that there are any fixed principles on the subject. Sometimes they favoured free trade, sometimes protection; sometimes they cockered up one species of industry, sometimes another, according to the whim of the moment. They never seem to have had the faintest idea that the true principle was to leave every industry alone, and allow each one to develop itself according to its natural tendencies.

Every one has heard of the glories of the reign of Louis XIV; but few probably have any idea of the terrible reaction, and the incredible disasters and misery of the end of his reign. These may be learnt from contemporary writers and also from Taine's History of the Ancient Régime. Soon after the death of Louis XIV, John Law was allowed to try in France his scheme of paper money, which had been previously rejected by the Scottish Parliament. The result was that disastrous catastrophe known by the name of the Mississippi Scheme. In 1749 Turgot, then a young man of twenty-two, began to reflect upon these terrible calamities, and endeavoured to discover the error of Law's system. Turgot associated with himself Gourlay, an eminent merchant who was a keen advocate of free trade, Quesnay the king's physician, Le Trosne, Mirabeau père, the Abbé Baudeau, and many others, who formed themselves into a powerful sect under the name of the 'Economists.' These men were the first to perceive and declare that there is a positive and definite science which may be named Economics.

They found France divided into a number of separate and semi-independent provinces, each of them surrounded with customhouses, which were an intolerable barrier to commercial intercourse; every species of industry was loaded with minute and oppressive regulations; a very large portion of the human race was groaning under the bonds of slavery; in every country persons were relentlessly persecuted for their religious opinions. The Economists held that these commercial, personal and religious oppressions were contrary to the fundamental rights of mankind.

They proclaimed as the indefeasible natural rights of mankind the freedom of person, the freedom of opinion, and the freedom of exchange or of commerce.

Quesnay (who was the real founder of the science) and his followers, reflecting on the intolerable misery they saw around them, struck out the idea that there must be some great natural science, some principles of eternal truth founded on nature itself, with regard to the social relations of mankind, the violation of which was the cause of the hideous misery of their native land. The name Quesnay first gave to it was natural right; and his object was to discover and lay down an abstract science of the natural rights of men in all their social relations. This science comprehended their relations towards the government, towards each other, and towards property. The term politique in French might in a certain way have expressed this science; but the word was so exclusively appropriated to the art of government that they adopted for it the name 'political economy,' or 'economical philosophy'; and hence they were named 'the Economists.' Dupont de Nemours, one of their number, proposed the name of physiocratie, or the government of the nature of things; and hence they were often called the physiocrates; but the word, having been appropriated to certain doctrines of the sect which are now shown to be erroneous, and abandoned by all subsequent Economists of note, has fallen into disuse, and the term political economy, or Economics, which is now more commonly used, has survived.

Now it is evident that this wide and extensive scheme comprehends not only a single science, but a whole multitude of sciences; and we shall henceforth confine ourselves strictly to that part of it which relates to commerce or exchanges.

Quesnay's first publication, Le Droit Naturel, contains a general inquiry into these natural rights; and he afterwards in another work, called Maximes Générales du Gouvernment Économique d'un Royaume Agricole, endeavoured to lay down, in a series of thirty maxims or general principles, the whole basis of the economy of society. The twenty-third of these declares that a nation suffers no loss by trading with foreigners; the twenty-fourth declares the fallacy of the balance of trade; the twenty-fifth says: 'Let entire freedom of commerce be maintained; for the regulation of commerce, both internal and external, the most sure, the most exact, the most profitable to the nation and to the State, consists in entire freedom of competition.' These maxims entirely overthrew the prevailing system of political economy. This was the work of Quesnay and his followers; and, notwithstanding certain errors and shortcomings mentioned below, they are unquestionably entitled to be acknowledged as the founders of political economy and free trade.

We may now give a brief abstract of the doctrine of the Economists, by which they vindicated the principle of liberty and the right of property.

The Creator has placed man upon the earth with the evident intention that the race should prosper; and there are certain physical and moral laws which conduce in the highest degree to ensure its preservation, increase, well-being and improvement. The correlation between these physical and moral laws is so close that if either be misunderstood, through ignorance or passion, the others are also. Physical nature, or matter, bears to mankind very much the relation which the body does to the mind. Hence the perpetual and necessary relation of physical and moral good and evil to each other.

Natural justice is the conformity of human laws and actions to natural order; and this collection of physical and moral laws existed before any positive institutions among men. And while their observance produces the highest degree of prosperity and well-being among men, the non-observance or transgression of them is the cause of the extensive physical evils which afflict mankind.

If such a natural order exists, our intelligence is capable of understanding it; for if not, it would be useless, and the sagacity of the Creator would be at fault. As, therefore, these laws are instituted by the Supreme Being, all men and all states ought to be governed by them. They are immutable and irrefragable, and the best possible laws; they are necessarily the basis of the most perfect government, and the fundamental rule of all positive laws, which are only for the purpose of upholding that natural order which is evidently the most advantageous for the human race.

The evident object of the Creator being the preservation, the increase, the well-being, and the improvement of the race, man necessarily received from his origin not only intelligence, but instincts conformable to that end. Every one feels himself endowed with the triple instincts of well-being, sociability, and justice. He understands that the isolation of the brute is not suitable to his double nature, and that his physical and moral wants urge him to live in the society of his equals in a state of peace, goodwill and concord. He also recognizes that other men, having the same wants as himself, cannot have less rights than himself, and therefore he is bound to respect their right, so that other men may observe a similar obligation towards him.

These three ideas—the necessity of work, the necessity of society, and the necessity of justice—imply three others— liberty, property and authority—which are the three essential terms of all social order.

How could man understand the necessity of labour or obey the irresistible instinct of self-preservation without perceiving at the same time that the instrument of labour, the physical and intellectual qualities with which he is endowed by nature, belong exclusively to himself, that he is master and the absolute proprietor of his own person, that he is born and should remain free?

But the idea of liberty cannot spring up in the mind without associating with it that of property, in the absence of which the first would only represent an illusory right without an object. The freedom the individual has of acquiring useful things by labour includes necessarily the right of preserving them, of enjoying them, and of disposing of them without reserve, and also of bequeathing them to his family, who prolong his existence indefinitely. Thus liberty conceived in this manner involves and is dependent on the idea of property, which may be conceived in two aspects, as it regards moveable goods, and as it regards the earth, which is the source from which labour ought to draw them.

At first property was principally moveable; but when the cultivation of the earth was necessary for the preservation, increase, and improvement of the race, individual appropriation of the soil became necessary, because no other system is so proper to draw from the earth all the mass of utilities it can produce; and secondly, because collective property would have produced many inconveniences as to the sharing of the fruits, which would not arise from the division of the land, by which the rights of each are fixed in a clear and definite manner. Property in land is, therefore, the necessary and legitimate consequence of the principle of personal and moveable property. Every man has, therefore, centred in him by the laws of Providence certain rights and duties, the right of enjoying himself to the utmost of his capacity, and the duty of respecting similar rights in others. This perfect protection of reciprocal rights and duties conduces to production in the highest degree, as well as to the greatest amount of physical enjoyments. Thus the Economists established freedom and property as the fundamental right of mankind—freedom of person, freedom of opinion, freedom of exchange or commerce; and the violation of these they maintained to be contrary to the laws of Providence, and therefore the cause of all evil to men.

We must now examine what their doctrines were regarding exchanges or commerce.

While they expressly declared that exchanges, or commerce, were one of the departments of economical philosophy, they most unfortunately devised another and alternative name for it, which being misinterpreted by a subsequent very distinguished French writer, has been the cause of all the mischief and confusion of the science in recent times.

They termed the department of economical philosophy relating to exchanges, or commerce, the 'production, distribution and consumption of wealth.' It might not be very apparent to the general reader how in the mind of the Economists these two concepts are identical, and meant exactly the same thing; and we must now explain the interpretation of this latter expression given to it by its authors.

They defined the word wealth to mean the material products of the earth which are brought into commerce and exchanged, and those only. The products of the earth, which were consumed by their owners without an exchange, they termed biens, but not richesse. They steadfastly refused to admit that labour and credit are wealth; because they alleged that this was to allow that wealth can be created out of nothing. They constantly maintained that man can create nothing, and that ex nihilo nihil fit.

By production they meant obtaining the rude produce from the earth and bringing it into commerce.

But this rude produce is scarcely ever fit to be used by men. It has to be fashioned and manufactured in a multitude of ways, to be transported from place to place, and perhaps sold and resold more than once before it is ultimately purchased for use and enjoyment.

All these intermediate operations of manufacture, transport and sale between the original producer and the ultimate purchaser the Economists termed traffic, or distribution.

The final purchaser, who bought the product for his own use and enjoyment, and so took it out of commerce, they termed the acheteur-consommateur; because he consummated, or completed, the operation.

Consommation, in the language of the Economists and of all French writers before them, meant simply purchase, or demand; it involved no idea of destruction.

The consommateur, or consumer, was the person for whose benefit all the preceding operations took place. Production was only for the sake of consumption, or demand; and consumption, or demand, was the measure of reproduction; because products which remain without consumption, or demand, degenerate into superfluities without value.

The complete passage of a product from the original producer to the ultimate consumer, or purchaser, through all its intermediate stages, the Economists termed commerce, or an exchange; and as any man who wished to consume, or purchase any product, must have some product of his own to give in exchange for it, he was also a producer in his turn. Hence, in an exchange, things are produced, and consumed or purchased, on each side. An exchange has only two essential terms—a producer, or seller, and a consumer, or purchaser. These are the only two persons necessary to commerce; and they often exchange directly between themselves, without any intermediate agents.

Hence the 'production, distribution and consumption of wealth,' as defined by the Economists, meant simply the commerce, or the exchange, of the material products of the earth, and of these only.

But distribution was often used as synonymous with consumption. Hence 'production, distribution and consumption,' 'production and distribution,' and 'production and consumption' all meant exactly the same thing—the commerce or exchange of the material products of the earth.

It must be carefully observed that these expressions were one and indivisible; and they must not be separated into their component terms. They all meant simply supply and demand.

The Economists, by restricting the term wealth to the material products of the earth, made materiality and labour the accessories or accidents of wealth; but they did not make them the principle, or essence, of wealth. The essence, or principle, of wealth they held to consist in exchangeability; because they expressly excluded the material products of the earth which were not brought into commerce and exchanged from the term wealth.

Now, considering that the Economists admitted and declared that there is a positive and definite science of exchanges or commerce, how is it possible to restrict it to the commerce or exchanges of material products only? It must evidently and necessarily comprehend all exchanges, or all commerce in its widest extent and in all its various forms.

There is a gigantic commerce in labour; there is a colossal commerce in rights and rights of action, credits, or debts. How is it possible to exclude the commerce in labour and the commerce in rights and rights of action from the general science of exchanges, or commerce?

The basis of the science of Economics is the meaning or definition of the term WEALTH. The Economists admitted that exchangeability is the real essence of wealth; but they clogged it with the limitation that it only applied to material products, and denied it to labour and credit, which equally possess the quality of exchangeability. But this is contrary to the fundamental principles of natural philosophy. Bacon long ago pointed out that when the quality or the concept which is at the basis of a science is once determined, all quantities whatsoever which possess that quality, however diverse in form they may be, must be included among the elements or constituents of the science. This is what Plato calls the one in the many, i.e. the same quality appearing in many different forms. It would be just as rational to restrict the term force to the force of men and animals, and to exclude gravitation from the term force.

Ancient writers for 1,300 years unanimously held that exchangeability pure and simple is the sole essence and principle of wealth; that everything which can be bought and sold, or exchanged, is wealth, whatever its nature or its form may be.

Aristotle defined wealth to be all things whose value can be measured in money. Here we have a fundamental concept, of the widest generality, and fitted to form the basis of a great science. Out of this single sentence of Aristotle the whole Science of Economics is to be evolved, just as the great oak is developed out of a tiny acorn.

In an ancient anonymous dialogue Socrates is made to show that money is only

wealth where and when it can be exchanged, or purchase other things; where it

cannot be exchanged, or purchase other things, it is not wealth. He shows that

anything which can be exchanged for, or purchase other things like money, is

wealth, for just the same reason. He says that persons gain their living by

giving instruction in the sciences. Therefore, he says, the sciences are wealth— and that those who possess them are wealthier—

and that those who possess them are wealthier— .

This is the first recognition, of which I am aware, that labour is wealth.

.

This is the first recognition, of which I am aware, that labour is wealth.

Demosthenes showed that personal credit is wealth; because a merchant can purchase goods with his credit equally as with money.

The Roman jurists showed that rights and rights of action, such as credits or debts, are wealth, because they can be bought and sold.

Thus, after 800 years from the time of Aristotle, the Roman jurists completed the science, because they completed the number of its constituent elements. There is nothing which can be bought and sold or exchanged, or whose value can be measured in money, which is not of one of these three forms, or orders of quantities: (1) material products; (2) personal qualities, i. e. labour which can be exchanged for wages, and character which may entitle to credit; and (3) abstract rights.

There is no trace in ancient writers of any such doctrine as that labour and materiality are necessary to wealth and value. Thus they answered, 2,100 years ago, the doctrine of the Economists that labour is necessary to wealth, because they declared that personal qualities and abstract rights are wealth, and they recognized three orders of economic quantities. These can be exchanged against one another in six different ways; and these six different kinds of exchange constitute commerce in its widest extent and in all its forms and varieties.

The relation of these quantities to each other is termed their value; and the laws of natural philosophy show that there can be only one general law of value, or a single general equation of Economics.

We have thus a definite body of phenomena, all based upon a single general concept; separate and distinct from all other phenomena, and circumscribed by a definition, which constitutes a science, and may be designated as pure, or analytical, Economics.

Thus, if any one had conceived the idea of describing the mechanism of these exchanges, or of commerce, Economics might have been the eldest born of all the sciences; but there was no science in existence in those days to serve as a model for the creation of a science of Economics; and a long and dreary interval had to elapse before the moderns reached the perfection of the ancients, all to redound to the immortal glory of Bacon, who was the first to point out that the physical sciences must first be created to serve as models before it is possible to create the sciences of society.

For many centuries it was held that money alone is wealth; and we must briefly state some of the consequences which flowed from this doctrine, which produced innumerable wars and other calamities.

A strange consequence flowed from the doctrine that only money is wealth. It was held for many centuries that in an exchange what one side gained the other lost. What the persons who maintained this doctrine would have said to an exchange of products it would be difficult to imagine. They quite forgot that when persons bought things with money they obtained a satisfaction for their money. Nevertheless, for centuries, the wisest statesmen and philosophers maintained that in commerce what one side gained the other lost. They held that foreign commerce which did not produce an importation of money was a loss to the nation. Accordingly, in every country, laws were made to encourage the importation of money and to prohibit its export. This doctrine was the cause of innumerable wars. J. B. Say, writing in the first quarter of this century, says that during the last three hundred years fifty had been spent in wars directly arising out of the dogma that money alone is wealth. About the end of the seventeenth century it began to be perceived that it was absurd to maintain that money alone is wealth; and the term was enlarged to include all the material products of the earth which conduce to man's subsistence and enjoyment. But still they held to the doctrine of the balance of trade, which was based on the assumption that, in every transaction of commerce, what one side gained the other lost.

The first merit of the Economists was that they entirely overthrew the doctrine of the balance of trade; and they made a considerable advance in Economics by maintaining that in commerce neither side gains or loses.

The Economists maintained that labour engaged in agriculture is the only form of productive labour; because, they alleged, it is the only one in which the value of the produce exceeds the cost of production. The excess of the value of the produce over that of the cost of production they called the produit net; and they maintained that, as this is the only increase of wealth to a country, all taxation should be levied out of the produit net of the agriculturists, and that all other classes should go free.

They denied that commerce or manufactures can enrich a nation; because, they alleged, in commerce equal values are always exchanged for equal values—and if the values exchanged are always equal, how can there be any profit on either side? They held that the only use of commerce is to vary and multiply the means of enjoyment, but that it does not add to the national wealth; or, if it does, it is only by giving a value to the products of the earth which might otherwise fail in finding a market. They contended also that, as all exchanges are merely equal value for equal value, the same principle also applies to sales, and therefore that the gains, which traders make, are no increase of wealth to the nation.

With such views they held that internal commerce conduces nothing to the wealth of the nation, and foreign commerce very little. They called foreign commerce only a pis aller. One very important truth, however, they perceived. They saw that money is the most unprofitable merchandise of any to import, and that merchants never import money when they can import products. Therefore they called the import of money only the pis aller of a pis aller.

They contended that the labour of artisans in manufactures is sterile or unproductive, because, though this labour adds to the value of the product, yet during the process of the manufacture the labourer consumes his subsistence; and the value added to the product only represents the value of the subsistence destroyed during the labour. Hence there was a transference of the value of the labourers' subsistence into an equivalent value of another kind; but no production of wealth.

They held that all the costs of trafficking come out of the profits of the producers and the consumers, which, though gains to them, are not profit to the nation; and therefore that the State ought not to tax them.

All classes of the community, except the agriculturists, they denominated sterile or unproductive.

These are the doctrines which the Economists maintained, with long and repeated arguments, in defiance of all opposition; but how men of the ability of the Economists could maintain that a country cannot be enriched by commerce or manufactures, with the examples of Tyre, Carthage, Venice, Florence, Holland, England, and hosts of others before them, is incomprehensible. With such patent glaring facts before them, it is surprising that they were not led to suspect the truth of their reasonings. It is one of those aberrations of the human intellect which we can wonder at, but not explain.

These doctrines provoked a reaction: men who were labouring in all sorts of vocations were roused to indignation, by being stigmatized as sterile and unproductive. Men were astounded to hear that a nation cannot be enriched by commerce or manufactures.

Nevertheless, the doctrines of the Economists seemed to be logically unassailable, provided that their fundamental dogma was right. But the consequences they drew from it were so startling, and so contrary to patent undeniable facts, that clear-sighted men began to inquire—Is it true that in commerce neither side gains?

Two writers entered the field against the Economists—Condillac in France, and Adam Smith in England. Both published their works in the same year, 1776. They overthrew the doctrine that in commerce neither side gains, and maintained that in commerce both sides gain—a truth that was seen by anticipation by the great Emperor Frederick II, in the thirteenth century; and by Boisguillebert, the morning star of Economics, in the beginning of the eighteenth century. In this brief sketch we have no space to say much about Condillac, because his explanation is not very satisfactory, and his work never attracted the slightest attention till very recently.

This, then, was the real origin of Adam Smith's work. He was neither the founder and creator of Economics nor of free trade. Economics, as a science, sprang out of the misery and calamities of the French people, and the Economists were the first to perceive and declare that there is a positive and definite science of Economics; and that, consequently, it must be constructed by exactly the same methods by which all other sciences have been created—namely, by settling its fundamental general concepts and definitions; by a strictly accurate statement of facts and phenomena; and by reducing all the phenomena to a single general law. Economics is the science of exchanges, or of commerce; and therefore the details of commerce are the phenomena of Economics. Nor was Adam Smith the founder of free trade. The Economists published their code of doctrine in 1759, in which free exchange was asserted to be one of the fundamental rights of mankind; and there were numerous and powerful advocates of free trade in Italy and Spain fifteen years before Adam Smith published a line. Turgot carried out immense reforms in the direction of free trade in 1774. How did these writers and statesmen learn the doctrines of free trade from Adam Smith, when his work was not published till 1776? The fact is that Adam Smith did not attempt to disprove the theory of protection and prohibition; he assumed free trade as the doctrine approved of by all enlightened minds. Adam Smith has done sufficient services himself to Economics, and his reputation does not require the advances and services done by other persons to be attributed to him.

Adam Smith, then, attacked the doctrine of the Economists, that in commerce neither side gains or loses. By a course of masterly reasoning, far superior to that of Condillac, but too long to be set out here, he demonstrated that in commerce both sides gain; and, therefore, that nations, in multiplying their commercial relations, multiply their profits and multiply wealth. Even if Adam Smith had never done anything else for Economics than this, he would have been entitled to immortal glory. By this single demonstration he brought about a change in public opinion and in international policy which has for ever removed a perennial source of war from the world. Nations learnt that instead of destroying each other, and trying to ruin each other's commerce, it was their interest to promote each other's prosperity and to multiply their commercial relations with each other.

Adam Smith next proceeded to demolish the doctrine that neither commerce nor manufactures enrich a nation. He demonstrated that both commerce and manufactures are productive of wealth, and enrich a nation.

Furthermore, he burst the bonds of the narrow dogmatism of the Economists, that the material products of the earth alone are wealth. For under the title of fixed capital he includes the 'natural and acquired abilities of the people'; and under the title of circulating capital he includes bank notes, bills of exchange, &c., which are mere abstract rights or credit, and types of vast masses of other incorporeal property. Hence he fully recognized the existence of the three orders of economic quantities, as the ancients had done.

But the utility of his work is sadly marred by the total want of clear, distinct and uniform fundamental concepts or definitions. He entitles his work, An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations; but he nowhere gives a clear and distinct definition of what wealth is. In the Introduction he says that the real wealth of a country is the annual produce of 'land and labour.' But he entirely omits exchangeability, which was the quality which the Economists, in agreement with the ancients, recognized as the essence of wealth. But Smith's definition is ambiguous. It is not clear whether he means the produce of land and the produce of labour, or the produce of 'land and labour' combined. It is probable that he meant the last; and so he has been generally understood. Now, such a definition is manifestly too wide and also too narrow; because there are multitudes of things which are the produce of 'land and labour' which are not exchangeable, and therefore not wealth; and there are multitudes of things which are exchangeable, and therefore have value and are wealth, which are in no way the annual produce of 'land and labour.'

Thus, after proceeding some length, he classes the 'natural and acquired abilities of the people' as fixed capital and as national wealth. How are the 'natural and acquired abilities of the people' the annual produce of 'land and labour'? Further on he classes bank notes, bills of exchange, &c., as circulating capital. How are these, which are mere incorporeal rights, the annual produce of 'land and labour'? It is evident that these ideas are absolutely incongruous. This indefiniteness of view we might have shown at much greater length; but these instances are sufficient to prove that his ideas of wealth in different parts of his work are absolutely inconsistent.

Furthermore, after inculcating for several hundred pages that value and wealth require the combination of 'land and labour,' he admits that if a thing is not exchangeable it is not wealth. He says that if a guinea could not be exchanged for other things it would not be wealth any more than a bill upon a bankrupt. Thus, after all, he recognizes that exchange-ability is the real essence of wealth. By this single sentence he upsets the whole theory which he had been so elaborately building up.

Keen observers have long ago seen that the first half of Adam Smith's work is entirely inconsistent with the latter half; because in the first half labour is considered as the essence of value and wealth, and in the second half exchangeability, i.e. demand, is admitted to be the real essence of value and wealth.

Ricardo adopted the first half of Adam Smith's doctrine, and founds all his ideas of value upon labour. Whately adopted the latter half, and adopts exchangeability pure and simple, and says that Adam Smith's title only denotes the subject-matter of his work; but that Economics is the science of exchanges, or of commerce.

Adam Smith's first two books are upon production and distribution; but he explains that that means commerce, and he says that his purpose is to examine the causes of the price of things; in other words, the theory of value; and McCulloch says in a note that it might be called the science of values.

An acute writer pointed out long ago that the great defect of Adam Smith is the total want of unity of doctrine, and the want of uniformity of principle. He never had the least idea that the phenomena of value must be reduced to a single general law; but he catches at any theory which seems to explain the cases which for the moment he is considering. The consequence is that his theories are utterly inconsistent with each other; and of course, as they are a series of contradictions, they must sometimes be right. Moreover, though his work abounds with shrewd observations, it is entirely wanting in the very first requisite of every work of science, a clear and accurate definition of its subject-matter. Consequently, though Adam Smith did great and solid services in overthrowing the prejudices and errors of his own day, his work is in no way fitted as an exposition of the actual science at the present day; in fact, most of the great and complex problems, which are of pressing importance at the present day, had not arisen when he died.

Now, from the foundation of Economics as a science up to the time of Whately, who was Professor at Oxford in 1830, there was in this country a perfect uniformity of opinion as to the general nature of the science. The Economists expressly declared that it is the science of exchanges, or of commerce, or the theory of value: and so it was understood to be by the writers in France who did not enrol themselves in the sect of the Economists; by Condillac, Adam Smith, Ricardo, McCulloch, Whately, and all persons who were interested in it. And, however imperfect it might have been, or however many defects it may have had, these were all capable of being rectified. If this concept had been steadily adhered to, and the same labour had been bestowed upon it, to rectify and develop it, by the same methods by which all other sciences have been created, it might long ago have been erected into a positive and definite science, like any of the physical sciences.

But, most unfortunately, the science was thrown into utter confusion, and its progress retarded for a long time, by a distinguished French writer, J. B. Say, about the beginning of this century. He adopted the second and alternative definition of the science which the Economists most unguardedly and unadvisedly suggested. Moreover, he completely changed the meaning of its fundamental terms; by which he ruined Economics as a science, and has been the cause of all the subsequent confusion and of the deplorable state in which it is at present. From this state of chaos it has only begun to recover in recent times. Those who have examined the matter closely are beginning to see that the system of J. B. Say is absolutely unworkable as a practical science, and that in order to construct Economics as a positive science it is indispensable to revert to the original concept of it as the science of exchanges or of commerce.

While the Economists declared that the expression 'production, distribution and consumption' of wealth is one and indivisible, and meant nothing but exchange, or commerce, J. B. Say broke it up into its constituent terms and completely changed their meaning. While the Economists defined production to mean bringing the rude produce of the earth into commerce, Say defined it to mean bestowing value on a product. While the Economists defined distribution to mean the intermediate operations between production and consumption, and those only, Say treats of distribution in such a nebulous way that it is difficult to make out distinctly what be means by it. The Economists and Adam Smith used the word consumption (consommation) to mean purchase pure and simple, or demand; Say defined it to mean the destruction of value, and says that all consumption is a destruction of value. The absurdity of this is patent. When a person purchases (i.e. consumes, in the language of the Economists and Adam Smith) a diamond ring, a piece of plate, a picture, a statue, or a book—does he thereby destroy them? The fact is that consumption, which Say defined to mean destruction, is no part of Economics at all. For Economics is limited to the phenomena of exchange.

The Economists steadfastly refused to admit that labour and credit are wealth. But on the first page of his work Say classes titres de créance, bank notes, bills of exchange, the funds, &c., as wealth; and further on includes many other kinds of incorporeal property under the title of wealth. These are all abstract rights. Say also, like Adam Smith, includes all the industrial faculties of the people under the definition of wealth and capital.

Now, how can we speak of the 'production, distribution and consumption' of bank notes, bills of exchange, the funds, shares in commercial companies, copyrights, patents, and the other forms of incorporeal property?

How can we speak of the 'production, distribution and consumption' of labour of different kinds, of knowledge, and other intellectual qualities, and of personal credit?

Whereas we speak of the supply and demand, and the value of all these things; and they are all the subjects of exchange or commerce. The whole operations of mercantile credit—the colossal system of banking—and the foreign exchanges—are all sales, or exchanges, and integral departments of commerce: but how can their mechanism and phenomena be explained under the expression the 'production, distribution and consumption of wealth'?