The Enlightenment: Ideas of Criticism and Reform in an International Context

|

|

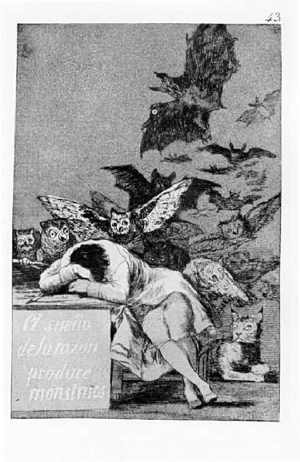

| Goya, "The Sleep of Reason produces Monsters" |

This is part of a collection of works on the history of the classical liberal tradtion.

Honours Special Subject

First Semester 1990

Department of History

University of Adelaide

David M. Hart

Content and Purpose of the Course

The course will deal with some of the classic works of the Enlightenment by Diderot, Rousseau, Voltaire, Beccaria, Raynal, Smith, Beaumarchais, Mozart, Condorcet, and Goya. Although the main focus is France a selection of works from Italy, Scotland, and Spain will also be read. The purpose of the course is to show that, while France was the focal point and French the language through which enlightened ideas were disseminated, the movement of criticism and reform was not restricted to the French nation but was a European-wide and even transatlantic phenomenon. The objects of criticism and reform ranged from institutions such as the church, the legal system, slavery and the economy to culture, social theory, art, and visions of the future. The work of the historian Peter Gay will provide a focus for our reading and discussion.

Course Requirements and Assessment

The course will consist of 13 weekly seminars which are divided into three parts. Part A consists of two introductory seminars which deal with the nature of the Enlightenment in a general way. Part B consists of nine seminars dealing with nine key texts in chronological order. Part C consists of two concluding seminars on the work of the historian Peter Gay.

The assessment for honours special subjects is either a) two end of semester examinations or b) an examination and a 5,000 word essay. Those who choose assessment option a) will also be required to present three short seminar papers of 2,500 words - two to be chosen from the topics in Part B and one on Peter Gay's interpretation of the Enlightenment. Those who choose assessment option b) will choose an essay topic from the list of topics in Part B and will also present two other short seminar papers of 2,500 words - one on another topic from Part B and the other on Peter Gay's assessment of the Enlightenment. The short seminar papers will be commented upon and graded but will not count towards the final assessment.

The short seminar papers on Peter Gay's interpretation of the Enlightenment will be presented at the last seminar. Those doing the essay will present a preliminary report on their reading to the seminar in the relevant week. The essay is due at the end of the semester.

Seminar Program

The program is as follows:

- Part A. Was ist die Aufklärung?

- 1. The Enlightenment in France.

- 2. The Enlightenment in other nations: The Enlightenment in National Context (1981).

- Part B. Essential Works of the Enlightenment

- 3. The Codification and Transmission of the Enlightenment: Denis Diderot and the Encyclopédie (1751).

- 4. Rousseau on Freedom and Inequality: Jean-Jacques Rousseau, A Discourse on Inequality (1754).

- 5. The Attack on Religion: Voltaire, Philosophical Dictionary (1764).

- 6. Reform of the Law and Punishment: Beccaria, On Crimes and Punishment (1764).

- 7. Opposition to Slavery and Colonialism: Abbé Raynal, Philosophical History of the Two Indies (1772).

- 8. Commerce and Liberty: Adam Smith, The Weath of Nations (1776).

- 9. The Enlightenment in Drama and Opera: Beaumarchais’ and Mozart’s The Marriage of Figaro (1778, 1786).

- 10. Progress and the Vision of an Enlightened Future: Condorcet, Sketch for a Historical Picture of the Progress of the Human Mind (1793).

- 11. Criticism of the Ancien Régime in Art: Francisco Goya, Los Caprichos (1799).

- Part C. Peter Gay on the Enlightenment

- 12. Peter Gay's Dialogue between Lucian, Erasmus and Voltaire on the Nature of the Enlightenment: The Bridge of Criticism (1970).

- 13. Presentation of seminar papers on Peter Gay's interpretation of the Enlightenment: The Enlightenment: An Interpretation (1969) and other works.

Part A. Was ist die Aufklärung?

1. The Enlightenment in France.

The historiography of the Enlightenment is enormous and one can all too easily be overwhelmed by the sheer quantity of material on the subject. To get started on your reading I suggest that you begin with the short overviews given by Norman Hampson. Since the course will end with a seminar on Peter Gay's magisterial interpretation of the Enlightenment it would be useful to begin reading his magnum opus The Enlightenment: An Interpretation and to sample some of his shorter essays such as the introduction to the anthology of extracts. If you have time you might like to try some of the classic accounts listed in the recommended reading. Alternatively, read the definition of Enlightenment given by the German enlightened philosopher Immanuel Kant in "What is Enlightenment?"

Seminar Reading

Norman Hampson, The Enlightenment (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1968).

Norman Hampson, “The Enlightenment in France” in The Enlightenment in National Context, ed. Roy Porter and Mikulás Teich (Cambridge University Press, 1981), p. 41-53.

Recommended Reading

Peter Gay, "Introduction," in The Enlightenment: A Comprehensive Anthology, ed. Peter Gay (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1973), pp. 13-25.

Peter Gay, The Enlightenment: An Interpretation (New York: Norton, 1977), 2 vols.

Peter Gay, The Party of Humanity: Essays in the French Enlightenment (New York: W.W. Norton, 1971).

Immanuel Kant, "What is Enlightenment?" in The Enlightenment: A Comprehensive Anthology, ed. Peter Gay (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1973), pp. 383-89.

Ernst Cassirer, The Philosophy of the Enlightenment, trans. Fritz C.A. Koelln and James P. Pettegrove (Boston: Beacon Press, 1965).

Alfred Cobban, In Search of Humanity: The Role of the Enlightenment in Modern History (1960).

Paul Hazard, European Thought in the Eighteenth Century , trans. J. Lewis May (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1965).

Kingsley Martin, French Liberal Thought in the Eighteenth Century: A Study of Political Ideas from Bayle to Condorcet, ed. J.P. Mayer (New York: Harper Torchbooks, 1963).

Franco Venturi, Utopia and Reform in the Enlightenment (Cambridge University Press, 1971).

Ira O. Wade, The Structure and Form of the French Enlightenment, 2 vols. (Princeton University Press, 1977).

Ira O. Wade, Intellectual Origins of the French Enlightenment (princeton, 1971).

Maurice Cranston, Philosophers and Pamphleteers: Political Theorists of the Enlightenment (Oxford University Press, 1986).

J.H. Brumfitt, The French Enlightenment (London, 1972).

2. The Enlightenment in other nations: The Enlightenment in National Context (1981).

The Enlightenment was not purely a French affair even though the language of enlightened thinking was French and most of the key works were written by Frenchman and published in France. To get an idea of how pervasive the Enlightenment was in the eighteenth century you need to consult Porter and Teich's excellent collection of essays. I suggest that you choose one of the nations discussed in their collection (e.g. England, Scotland, the Netherlands, Switzerland, Italy, Germany, Austria, Bohemia, Sweden, Russia and America), read the relevant essay, and do some exploring of your own in the "Further Reading."

Seminar Reading

The Enlightenment in National Context, ed. Roy Porter and Mikulás Teich (Cambridge University Press, 1981).

Part B. Essential Works of the Enlightenment

3. The Codification and Transmission of the Enlightenment: Denis Diderot and the Encyclopédie (1751).

If one work symbolises what the Enlightenment was about, it is the great "Encyclopaedia" of Diderot. Within the confines of an admittedly enormous work in many volumes the editor Diderot was able to include articles on politics, philosophy, religion, literature and most importantly science and technology and he arranged for these articles to be written by some of the most famous names of the Enlightenment. We want to examine Diderot's motives in beginning such a project, what he hoped to achieve, the attitudes he and his contributors were promoting, and the way in which these ideas were disseminated across France and later Europe. Begin with an introductory work on Diderot such as Cranston or France before turning to the more detailed studies. A good idea of the types of articles in the Encyclopédie can be got from the selection edited by Gendzier and the fabulous etchings which accompanied the volumes of text can be seen in either the facsimile edition of the French original or the selection in Gillispie's book. The dissemination of the Encyclopédie by booksellers is the subject of a fascinating study by Darnton. Just dip into it to get some idea of the mechanics of spreading ideas in ancien régime France.

Seminar Reading

Denis Diderot's The Encyclopedia: Selections, ed.and trans. Stephen J. Gendzier (New York: Harper and Row, 1967).

Robert Darnton, The Business of Enlightenment: A Publishing History of the Encyclpédie 1775-1800 (Camridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1979).

Recommended Reading

Selected Essays from the Encyclopaedia, being the most curious, entertaining and instructive parts of that very extensive work (London: Samuel Leacroft, 1772). Available in the Rare Book room.

A Diderot Pictorial Encyclopedia of Trades and Industry, Manufacturing and the Technical Arts in Plates Selected from "L'Encyclopédie, ou Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers" of Denis Diderot, ed. Charles Coulston Gillispie, 2 vols (New York: Dover, 1959).

Encyclopédie, ou Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers, facsimile of the first edition of 1751-1780 (Stuttgart-Bad Connstatt, 1966).

Maurice Cranston, "Diderot," Philosophers and Pamphleteers: Political Theorists of the Enlightenment (Oxford University Press, 1986), pp. 98-120.

Peter France, Diderot (Oxford University Press, 1983).

Arthur M. Wilson, Diderot (Oxford University Press, 1972).

John Hope Mason, The Irresistible Diderot (London: Charter Books, 1982).

John Lough, The Contributors to the Encyclopédie (London: Grant and Cutler, 1973).

Lester G. Crocker, "Diderot and the "Encyclopédie,"" Modern Language Quarterly, 1963, vol. XXIV, pp. 274-80.

John Morley, Diderot and the Encyclopaedists, 2 vols (London, 1878).

A. Strugnall, Diderot's Politics (The Hague, 1973).

Nellie Noémie Schargo, History in the Encyclopédie (1947) (New York: Octagon, 1970).

Jacques Proust, Diderot et l'Encyclopédie (Paris: Armand Colin, 1962).

Charly Guyot, Diderot par lui-même (Paris: Seuil, 1953).

Lester G. Crocker, The Embattled Philosopher: A Biography of Denis Diderot (London: Neville Spearman, 1955).

Robert Darnton, The Literary Underground of the Old Regime (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1982).

John Lough, Essays on the Encyclopédie of Diderot and D'Alembert (Oxford Unversity Press, 1968).

John Lough, The Encyclopédie in Eighteenth Century England and Other Studies (Newcastle on Tyne: Oriel Press, 1976).

René Hubert, Les sciences sociales dans l'Ecyclopédie: le philosophie de l'histoire et le problème des origines sociales (1923) (Genève: Slatkine Reprints, 1970).

J. Le Gras, Diderot et l'Encyclopédie (Paris: Société française d'Editions littéraire et techniques, 1942).

4. Rousseau on Freedom and Inequality: Jean-Jacques Rousseau, A Discourse on Inequality (1754).

Rousseau's place within the Enlightenment was often an uneasy one as his radical political ideas annoyed other members of the Enlightenemnt as much as they did the authorities. Although Rousseau is perhaps best remembered for his ideas on radical democracy in the Social Contract (1762) the text I have chosen for this week's reading is an earlier essay A Discourse on Inequality (1754). Topics we are interested in are Rousseau's view of property, freedom, the state of nature, the powers of the state, and the nature of inequality between the classes. Once again begin with an introductory work such as Miller or Cranston's chapter in Philosophers and Pamphleteers before looking at the specialist literature.

Seminar Reading

Jean-Jacques Rousseau, A Discourse on Inequality (1754), ed. Maurice Cranston (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1984).

Recommended Reading

Maurice Cranston, "Rousseau," Philosophers and Pamphleteers: Political Theorists of the Enlightenment (Oxford University Press, 1986), pp. 62-97.

Mario Einaudi, The Early Rousseau ((Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press, 1967).

Maurice Cranston, Jean-Jacques: The Early Life and Work of Jean-Jacques Rousseau 1712-1754 (London: Allen Lane, 1983).

Lester G. Crocker, Jean-Jacques Rousseau. Vol. 1 The Quest (1712-1758) (New York: Macmillan, 1974).

Ernst Cassirer, The Question of Jean-Jacques Rousseau, trans. Peter Gay (New York: Columbia University Press, 1956).

Peter Gay, "Reading About Rousseau," in The Party of Humanity: Essays in the French Enlightenment (1964), pp. 211-61.

John Lough, "The Encyclpédie and the Contrat Social," in Reappraisals of Rousseau: Studies in Honour of R.A. Leigh, ed. Simon Harvey, et al. (Manchester University Press, 1980), pp. 64-74.

James Miller, Rousseau: Dreamer of Democracy (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1984).

George R. Havens, Rousseau (Boston: Twayne, 1978), especially pp. 60-67.

Robert Derathé, "La place et l'importance de la notion d'égalité dans la doctrine politique de Jean-Jacques Rousseau," in Rousseau after Two Hundred Years: Proceedings of the Cambridge Bicentennial Colloquium, ed. R.A. Leigh (Cambridge University Press, 1982), pp. 55-63.

5. The Attack on Religion: Voltaire, Philosophical Dictionary (1764).

Probably the best known critic of Christian religious doctrine and the political abuses of the Catholic church in the eighteenth century is Voltaire. Although Voltaire was not an atheist (and there were some such as d’Holbach in enlightened circles) he incurred the wrath of the church with his articles in the Philosophical Dictionary and his campaign to clear the name of Calas, a Protestant falsely accused of killing his son for converting to Catholicism. Begin with Gay’s introductiuon to the Philosophical Dictionary and read a selection of the articles. If you have time you might also look at the selection of texts on religion in Gay's The Enlightenment: A Comprehensive Anthology and the section in The Enlightenment: An Interpretation which deals with paganism and Christianity.

Seminar Reading

Voltaire, Philosophical Dictionary (1764), trans. Peter Gay (New York: Harcourt, Brace and World, Inc., 1962). “Editor’s Introduction” pp. 352 and selected articles by Voltaire on religion.

Recommended Reading

Voltaire, "Sermon of the Fifty," in Deism: An Anthology, ed. Peter Gay (Princeton, New Jersey: Van Nostrand, 1968), pp. 143-58.

Peter Gay, Voltaire’s Politics: The Poet as Realist (New York: Vintage, 1965). “Ferney: The Poisonous Tree” pp. 239-72 and “Ferney: The Man of Calas” pp. 273-308.

Peter Gay, “The Philosophe in His Dictionary,” The Party of Humanity: Essays in the French Enlightenment (1964).

Peter Gay, The Enlightenment: An Interpretation (New York: Norton, 1977), vol. 1 “The Rise of Modern Paganism” Book Two “The Tension with Christianity,” pp.212-419.

"III. The Critique of 'Superstitition' and 'Fanaticism,'" in The Enlightenment: A Comprehensive Anthology, ed. Peter Gay (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1973), pp. 197-282.

Maurice Cranston, "Voltaire" Philosophers and Pamphleteers: Political Theorists of the Enlightenment (Oxford University Press, 1986), pp. 36-97.

Haydn Mason, Voltaire: A Biography (London, 1981).

Ira O. Wade, The Intellectual Development of Voltaire (Princeton University Press, 1969).

Voltaire, L’Affaire Calas et autres affaires, ed. Jacques Van den Heuvel (Paris: Gallimard, 1975).

David D. Bien, The Calas Affair: Persecution, Toleration, and Heresy in Eighteenth Century Toulouse (Princveton, 1960).

René Pomeau, La Religion de Voltaire (Paris: Nizet, 1956).

Politique de Voltaire, ed. René Pomeau (Paris: Armand Colin, 1963).

A.J. Ayer, Voltaire (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1986)."The Philsophical Dictionary” pp. 108-38 and “‘Écrasez l’infâme’” pp. 156-74.

R.R. Palmer, Catholics and Unbelievers in Eighteenth Century France (New York: 1961).

6. Reform of the Law and Punishment: Beccaria, On Crimes and Punishment (1764).

The often draconian and unfair legal system was the focus of much activity by enlightened reformers. Voltaire, for example, was active in several important law cases in an effort to overcome some of the harsher aspects of eighteenth century legal practice. However, perhaps the most famous law reformer of the time was the Italian Cesare Beccaria, whose On Crimes and Punishments (1764) espoused a more humane treatment of criminals. Begin with Franco Venturi's essay on Beccaria before starting Beccaria's book. It would also be useful to have some background material on the Enlightenment in Italy in order to place Beccaria in context. Owen’s essay on the Italian Enlightenment in the Porter and Teich collection is a good introduction and Venturi's other essays reveal how important the Enlightenment was in Italy. Peter Gay has a brief chapter on justice and legal reform in The Enlightenment: An Interpretation.

Seminar Reading

Franco Venturi, “Cesare Beccaria and Legal Reform,” Italy and the Enlightenment: Studies in a Cosmopolitan Century, ed. Stuart Woolf and trans. Susan Corsi (New York University Press, 1972), pp. 154-64.

Alessandro Manzoni's "The Column of Infamy" prefaced by Cesare Beccaria's "Of Crimes and Punishments," trans. Fr. Kenelm Foster O.P. and Jane Grigson, intro. A.P. d'Entrèves (London: Oxford University Press, 1964).

Recommended Reading

Marcello Maestro, Cesare Beccaria and the Origins of Penal Reform (Philadelphia, 1973).

Cesare Bonesana, Marchese di Beccaria, On Crimes and Punishments (1764), trans. Henry Paolucci (Indianapolis, 1963).

Cesare Bonesana Beccaria, Dei delitti e delle pene , ed. Franco Venturi (Turin, 1970).

Owen Chadwick, “The Italian Enlightenment” in The Enlightenment in National Context, ed. Roy Porter and Mikulás Teich (Cambridge University Press, 1981), pp. 90-105.

Peter Gay, "Justice: A Liberal Crusade," in The Enlightenment: An Interpretation (New York: Norton, 1977), vol. 2 "The Science of Freedom," pp. 423-47.

Voltaire, "A Commentary on the Book on Crimes and Punishments," in Marquis Beccaria, An Essay on Crimes and Punishment (London: H.D. Symonds, 1804), pp. i-lxxvii.

Edizione nazionale delle opere di Cesare Beccaria, ed. Luigi Firpo (Milan: Mediobanca, 1984), vol. 1-2, 6. Vol. 1 ed. Gianni Francioni contains "Of Crimes..."

7. Opposition to Slavery and Colonialism: Abbé Raynal, Philosophical History of the Two Indies (1772).

The philosophes were not only interested in liberating French citizens from the yoke of the ancien régime but also the blacks enslaved and forced to work in the colonies. Abolitionist thinking was part of the Enlightenemt from the very beginning as Davis, Seeber and Gay make clear. For example, articles in the Encyclopédie urged the abolition of slavery on the grounds of the universal natural rights of mankind and Voltaire satirised the Christian religion's tolerance for the practice in Candide. One of the most forceful statements against both slavery and colonialism was the Philosophical History by the Abbé Raynal (with the assistance of Diderot). Unfortunately, there is not much on Raynal in English although the library is fortunate to have an early English translation of Raynal's work, which can be consulted in the Rare Book Room. It is a lengthy work which should be dipped into rather than read right through. Davis provides a brilliant analysis of the problem of slavery in Western culture and the contribution of the Enlightenment to its eventual abolition. Seeber shows the attitude towards slavery in a range of late eighteenth century thinkers and Gay puts the abolitionist current in the perspective of the Enlightenment as a whole. Diderot's contribution to Raynal's history can be follwed up in the specialist reading on Diderot (see topic three).

Seminar Reading

Abbé Raynal, A Philosophical and Political History of the Settlements and Trade of the Europeans in the East and West Indies , trans. J. Justamond (London: Cadell, 1777, 2nd edition), 5 vols. The Rare Book room has two early French editions and a 1777 English translation which can be consulted there. About 250 pp. of extracts are available in reserve and include: on the treatment of the indigenous natives, vol. 2, book VI, "Discovery of America. Conquest of Mexico and settlements of the Spaniards in that part of the new world," pp. 350-411; on the slave trade, vol. 3, book XI, "The Europeans go into Africa to purchase slaves to cultivate the Caribbe islands. The manner of conducting this species of commerce. Produce arising from the labour of the slaves," pp. 382-504; on Raynal's conclusion, vol. 5, book XIX, "A View of the effects produced by the connections of the Europeans with the Americans on the Religion, Government, Policy, War, Navy, Commerce, Agriculture, Manufactures, Population, Public Crredit, Fine Arts and Belles Lettres, Philosophy, and Morals of Europe," on religion and government, pp. 399-451, on morals, pp. 594-605.

David Brion Davis, The Problem of Slavery in Western Culture (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1970), "13. The Enlightenment as a Source of Anti-Slavery Thought: The Ambivalence of Rationalism" and "14. The Enlightenment as a Source of Anti-Slavery Thought: Utility and Natural Law," pp. 423-55, 456-79.

Recommended Reading

Peter Gay, The Enlightenment: An Interpretation (New York: Norton, 1977), vol. 2, "The Science of Freedom," chapter 8 "The Politics of Decency" part 2 "Abolitionism: A Preliminary Probing," pp. 406-23.

Daniel P. Resnick, "The Société des Amis des Noirs and the Abolition of Slavery," French Historical Studies, 1972, vol. 7, no. 4, pp. 558-69.

William Cohen, The French Encounter with Africans: White Response to Blacks, 1530-1880 (Bloomington, Indiana, 1980).

David Brion Davis, The Problem of Slavery in the Age of Revolution 1770-1823 (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1975).

David Brion Davis, The Problem of Slavery in Western Culture (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1970), "13. The Enlightenment as a Source of Anti-Slavery Thought: The Ambivalence of Rationalism" and "14. The Enlightenment as a Source of Anti-Slavery Thought: Utility and Natural Law," pp. 423-55, 456-79.

Claudine Hunting, "The Philosophes and Black Slavery: 1748-1765," Journal of the History of Ideas, 1978, vol. 39, no. 3, pp. 405-18.

Serge Daget, "A Model of the French Abolitionist Movement and its variations," in Anti-Slavery, Religion and Reform: Essays in Memory of Roger Anstey, ed. Christine Bolt and Seymour Drescher (Folkstone, Kent: Dawson, Archon, 1980), pp. 64-79.

Irvine D. Dallas, "The Abbé Raynal and British Humanitarianism," Journal of Modern History, 1931, vol. 3, pp. 564-77.

Hans Wolpe, Raynal et sa machine de guerre (Stanford University Press, 1957).

Edward D. Seeber, Anti-Slavery Opinion in France During the Second Half of the Eighteenth Century (Baltimore, 1937. New York: Burt Franklin).

Vincent Confer, "French Colonial Ideas before 1789," French Historical Studies, 1964, vol. 3, pp. 338-59.

Robert Louis Stein, "The Revolution of 1789 and the Abolition of Slavery," Canadian Journal of History, 1982, vol. XVII, pp. 447-67.

Ruth F. Necheles, The Abbé Grégoire 1787-1831 (Westport, Conecticut, 1971).

Daniel Whitman, "Slavery and the Rights of Frenchmen: Views of Montesquieu, Rousseau, Raynal," French Colonial Studies, Spring 1974, vol. 1, pp. 17-33.

La Révolution Française et l'Abolition de l'Esclavage, 12 vols. (Paris: Editions d'histoire sociale).

Yves Benot, Diderot, de l'athéisme à l'anticolonialisme (Paris: Maspero, 1981).

J.-C. Bonnet, Diderot (Paris, 1982), pp. 306-45.

8. Commerce and Liberty: Adam Smith, The Weath of Nations (1776).

A major concern of the Enlightenment was economic reform and the origins of wealth and the nature of economic development. The Physiocrats in France and Adam Smith in Scotland were the leading figures in the creation of economics as a modern discipline of study and analysis. Smith in particular is commonly regarded as the founding father of economic thought with the publication of The Wealth of Nations (1776). The Wealth of Nations is a massive book which deals with an enormous range of issues, some of which are very technical. At the same time it is also a book of very readable history and sociology. I have selected for us to read the chapters dealing with the division of labour, his brief history of the rise of the modern economy, and his attack on mercantilist protection policies. Begin with Winch's essay on the connection between commerce and liberty and then read the chapters from The Wealth of Nations.

Seminar Reading

Donald Winch, "4. Commerce, Liberty and Justice," in Adam Smith's Politics: An Essay in Historiographic Revision (Cambridge University Press, 1979), pp. 70-104.

Adam Smith, An Inquiry into the Causes of the Wealth of Nations, ed. R.H. Campbell and A.S. Skinner (The Glasgow Edition of the Works and Correspondance of Adam Smith, Oxford University Press, 1976). "General Introdcution" by the editors, pp. 1-60. Selections to read: Book I, chapter 1 "Of the Division of Labour," chapter 2 "Of the Principle which gives Occasion to the Division of Labour," Book III "Of the different Progress of Opulence in different Nations," Book IV "Of Systems of Political Economy."

Recommended Reading

Peter Gay, The Enlightenment: An Interpretation (New York: Norton, 1977), vol. 2, "The Science of Freedom," chapter 7 "The Science of Society" part 3 "Political Economy: From Power to Wealth," pp. 344- 68.

"VI. The Science of Man and Society," in The Enlightenment: A Comprehensive Anthology, ed. Peter Gay (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1973), pp. 479-617.

Essays on Adam Smith, ed. Andrew S. Skinner and Thomas Wilson (Oxford, 1976).

Henry W. Spiegel, The Growth of Economic Thought (Englewood Cliffs, 1971).

Duncan Forbes, "Sceptical Whiggism, Commerce and Liberty," in Essays on Adam Smith, ed. Andrew S. Skinner and Thomas Wilson (Oxford, 1976).

Ronald L. Meek, "Smith, Turgot, and the 'Four Stages Theory,'" History of Political Economy, 1971, vol. 3, pp. 9-27.

Andrew S. Skinner, "Adam Smith: An Economic Interpretation of History, " in Essays on Adam Smith, ed. Andrew S. Skinner and Thomas Wilson (Oxford, 1976).

Wealth and Virtue: The Shaping of Political Economy in the Scottish Enlightenment, ed. Isvan Hont and Michael Ignatieff (Cambridge University Press, 1983).

David A. Reisman, Adam Smith's Sociological Economics (London: Croom Helm, 1976).

Samual Hollander, The Economics of Adam Smith (University of Toronto Press, 1973).

Jane Rendall, The Origins of the Scottish Enlightenment (London: Macmillan, 1978).

9. The Enlightenment in Drama and Opera: Beaumarchais’ and Mozart’s The Marriage of Figaro (1778, 1786).

Enlightened ideas were not only spread by the dessimination of encyclopaedias and works of history, political theory, and economics but also by means of novels and plays. It is not commonly known that Voltaire, for example, made his name as a playwright rather than as an historian, satirist or legal campaigner. A very popular and quite radical play was Beaumarchais's The Marriage of Figaro which was censored because Beaumarchais suggested that servants were the equal and often the better of their aristocratic superiors. We will examine the play with an eye for its political content and social observation and criticism. For those who are interested in music there is also Mozart's comic opera based on the same story. Some of the more piercing social commentry of Beaumarchais's play has been removed by the librettist Da Ponte but enough of the play remains for Mozart's opera to be interesting. Begin your reading with Sungolowsky's brief introduction and Cox's full-length biography. After having read the play you might like to follow the libretto of Mozart's opera, a copy of which is held in the library. Hutchings provides a good introduction to Mozart's life and times and Kaiser helps keep track of who is doing what to whom.

Seminar Reading

Beaumarchais, The Barber of Seville and the Marriage of Figaro, trans. John Wood (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1964, 1985). Translator's introdution, pp. 11-35 and "The Marriage of Figaro or the Follies of a Day," pp. 105-217.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Le Nozze di Figaro, conducted by Carlo Maria Giulini, Philharmonia Orchestra and Choir (EMI, 1961, 1989). Libretto by Lorenzo da Ponte.

Recommended Reading

Pierre Augustin Caron de Beaumarchais

Joseph Sungolowsky, Beaumarchais (New York: Twayne, 1974). "1. The Embattled Writer," pp. 15-31 and "5. Sparkling Gaiety," pp. 80-?.

Cynthia Cox, The Real Figaro: The Extraordinary Career of Caron de Beaumarchais (London: Longmans, 1962).

Beaumarchais, Le mariage de Figaro: comédie avec d'analyses méthodique de l'oeuvre, ed. Pol Gaillard (Paris: Bordas, 1976).

J.B. Rathermanis and W.R. Irwin, The Comic Style of Beaumarchais (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1961), pp. 49-108.

Beaumarchais par lui-même, ed. Philippe van Thieghem (Paris: Seuil, 1965).

Robert Niklaus, Le Mariage de Figaro (London: Grant and Cutler, 1983).

Francine Levy, Le Mariage de Figaro: essai d'interpretation (Oxford: Studies on Voltaire and the Eighteenth Century, 173, 1978).

J. Proust, "Beaumarchais et Mozart: une mise au point," Studi Francesi, 1972, vol. 46, pp. 34-45.

Special issue on Beaumarchais: Europe, April 1873, 528.

Mozart

Alfred Einstein, Mozart: His Character. His Work, trans. Arthur Mendel and Nathan Broder (London: Cassell, 1969).

Erich Schenk, Mozart and His Times, ed. and trans. Richard and Clara Winston (London: Secker and Warburg, 1960).

Arthur Hutchings, Mozart: The Man. The Musician (London: Thames and Hudson, 1976).

Joachim Kaiser, Who's Who in Mozart's Operas. From Alfonso to Zerlina, trans. Charles Kessler (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1986).

William Mann, The Operas of Mozart (London: Cassell, 1977). "Chapter 18. Le Nozze di Figaro," pp. 363-444.

Brigid Brophy, Mozart the Dramatist: A New View of Mozart, his Operas and His Age (London: Faber and Faber, 1964).

Christopher Benn, Mozart on the Stage (London: Ernest Benn, 1946). Reprinted (New York: AMS, 1976).

Charles Osborne, The Complete Operas of Mozart: A Critical Guide (London: V. Gollancz, 1978). "The Marriage of Figaro," pp. 221-54.

Robert B. Moberly, Three Mozart Operas: Figaro, Don Giovanni, and the Magic Flute (New York: Dodd, Mead and Co., 1968), pp. 35-143.

10. Progress and the Vision of an Enlightened Future: Condorcet, Sketch for a Historical Picture of the Progress of the Human Mind (1793).

Before he was arrested and died in prison during the French Revolution Condorcet wrote an introduction to a planned Historical Picture of the Human Mind known as the "Sketch." It is an optimistic vision of human progress in which the Tenth Stage of human history inaugurated by the French Revolution will lead to "the abolition of inequality between nations, the progress of equality within each nation, and the true perfection of mankind." The extent to which enlightened thinkers were optimistic about the future is disputed by historians, but it appears that in spite of the barriers to reform and the setbacks they experienced, Condorcet at least expected the future to be much better than the past or the present. Keith Michael Baker has written the most comprehensive recent work on Condorcet and has edited a selection of Condorcet's writings. Begin with Baker before tackling Condorcet himself. Peter Gay's views on progress and optimism in the Enlightenment can be found in The Enlightenment: An Interpretation.

Seminar Reading

Keith Michael Baker, "Introduction," in Condorcet: Selected Writings, ed. Keith Micahel Baker (Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, 1976), pp.vii-xxxvii. Extracts of the “Sketch for a Historical Picture of the Progress of the Human Mind,” pp. 209-282.

Sketch for a Historical Picture of the Progress of the Human Mind, trans. June Barraclough with an introduction by Stuart Hampshire (London, 1955).

Recommended Reading

Keith Michael Baker, Condorcet: From Natural Philosophy to Social Mathematics (The University of Chicago Press, 1975). Chapter 6 “The Esquisse: History and Social Science,” pp. 343-382.

Peter Gay, The Enlightenment: An Interpretation (New York: Norton, 1977), vol. 2 "The Science of Freedom," chapter 2 "Progress: From Experience to Program," pp. 56-125.

Maurice Cranston, "Condorcet," Philosophers and Pamphleteers: Political Theorists of the Enlightenment (Oxford University Press, 1986), pp. 140-56.

Condorcet, Esquisse d’un tableau historique des progrès de l’esprit humain, ed. O.H. Prior (Paris: Boivin, 1933).

Janine Bouissonouse, Condorcet: Le Philosophe dan la Révolution (Paris: Hachette, 1962).

F. Alengry, Condorcet: Guide de la Révolution française, théoricien du droit constitutionnel et précurseur de la science sociale (Paris, 1903).

Léon Cahen, Condorcet et la Révolution française (Paris, 1904).

Alexandre Koyré, “Condorcet,” Journal of the History of Ideas, 1948, vol. 9, pp. 131-52.

Frank E. Manuel, The Prophets of Paris: Turgot, Condorcet, Saint-Simon, Fourier, and Comte (New York: Harper Torchboks, 1965). pp. 53-102.

Rolf Reichardt, Reform und Revolution bei Condorcet: Ein Beitrag zur späten Aufklärung in Frankreich (Bonn, 1973).

J. Salwyn Shapiro, Condorcet and the Rise of Liberalism (New York, 1934).

On Progress

J.B. Bury, The Idea of Progress: An Inquiry into its Origins and Growth (London, 1920).

Charles Frankel, The Faith of Reason: The Idea of Progress in the French Enlightenment (New York, 1948).

Albert Salomon, The Tyranny of Progress: Reflections on the Origins of Sociology (New York, 1955).

R.V. Sampson, Progress in the Age of Reason (London: 1965).

Henry Vyverberg, Historical Pessimism in the French Enlightenment (1958).

11. Criticism of the Ancien Régime in Art: Francisco Goya, Los Caprichos (1799).

Enlightened reformers in Spain found the institutional resistance of the Crown and the Church and the widespread poverty and ignorance of the Spanish people a serious barrier to the spread of enligthened ideas. The court painter Fransisco Goya expressed his frustration with popular superstitution and ignorance in a series of prints known as "The Caprices." Goya reveals his sympathies towards the Enlightenment throughout the series but no more so than in "The Sleep of Reason" where Reason, slumped over a desk, is haunted by the demons of superstition, corruption and intolerance. Read Gassier for background and Williams and Lopez-Rey for an analysis and interpretation of Goya's work. Gay has not discussed Goya's work in any detail but he has written on art and taste which you may find interesting. He has also collected some extracts on "The Line of Beauty" in The Enlightenment: A Comprehensive Anthology.

Seminar Reading

Goya’s Caprichos (1799) (New York: Dover Publications, 1969).

Gwyn A. Williams, Goya and the Impossible Revolution (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1984). Chapter 3 “The Caprichos,” pp. 37-59.

Recommended Reading

Pierre Gassier, Goya: A Witness of His Times (Secaucus, New Jersey: Chartwell Books, 1983). Chapter IV “The Time of Friendship and the Enlightenment,” pp. 149-189.

José Lopez-Rey, Goya’s Caprichos: Beauty, Reason, and Caricature (Princeton University Press, 1953).

Peter Gay, The Enlightenment: An Interpretation (New York: Norton, 1977), vol. 2 "The Science of Freedom," chapter 5 "The Emancipation of Art: Burdens of the Past," pp. 216-48 and chapter 6 "The Emancipation of Art: A Groping for Modernity," pp. 249-318.

"V. The Line of Beauty," in The Enlightenment: A Comprehensive Anthology, ed. Peter Gay (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1973), pp. 415-77.

Franciso de Goya, Les Caprices facsimile edition, ed. Pierre Gassier (Grenoble, 1979).

Goya in Perspective, ed. Fred Licht (Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall, 1973).

F.D. Klingender, Goya in the Democratic Tradition (London: Sidgwick and Jackson, 1968). Chapter1 and 2 “Eighteenth-Century Spain - The Tapestry Cartoons” and “The Caprichos” pp. 1-110.

The World of Goya, 1746-1828, Richard Schickel and the Editors of TIME-LIFE BOOKS (Nederland N.V.: Time-Life International, 1972). “The Sleep of Reason” and Chapter VI “Los Caprichos: Society Unmarked,” pp. 108-27.

Juliet Wilson Bareau, Goya’s Prints: The Thomás Harris Collection in the British Museum (British Museum Publications, 1981).

Richard Herr, The Eighteenth-Century Revolution in Spain (Princeton University Press, 1973).

Michael Levey, Rococo to Revolution: Major Trends in Eighteenth-Century Painting (1966).

Part C. Peter Gay on the Enlightenment

12. Peter Gay's Dialogue between Lucian, Erasmus and Voltaire on the Nature of the Enlightenment: The Bridge of Criticism (1970).

Over the next two weeks we want to come to some assessment of Peter Gay's interpretation of the Enlightenment in his many essays and books, but most expecially in his massive The Enlightenment: An Interpretation. You have had several opportunities to read chapters of The Enlightenment: An Interpretation as we have dealt with various topics throughout the course. Now is the time to complete your reading of this work if you have not already done so. I have chosen another work of his to get an overview of his opinions. The Bridge of Criticism: Dialogues among Lucian, Erasmus, and Voltaire on the Enlightenment - on History and Hope, Imagination and Reason, Constraint and Freedom - and on its Meaning for our Time is not only a very witty and clever book, written in Gay's enviable style, but also a serious attempt to understand what was unique about the Enlightenment and what is of lasting value. Gay presents his ideas in a novel way in a series of fictional dialogues between Lucian, Erasmus and Voltaire. I suggest you read the book carefully and choose one of the three characters to defend in the seminar.

Seminar Reading

Peter Gay, The Bridge of Criticism: Dialogues among Lucian, Erasmus, and Voltaire on the Enlightenment - on History and Hope, Imagination and Reason, Constraint and Freedom - and on its Meaning for our Time (New York: Harper Torchbooks, 1970).

13. Presentation of seminar papers on Peter Gay's interpretation of the Enlightenment: The Enlightenment: An Interpretation (1969) and other works.

Peter Gay’s classic interpretation of the Enlightenment has been enormously influential. It is not only stylish and brilliantly written but is a tour de force of interpretation of a massive and complex subject. We have used Gay’s book and his other writings throughout the course and the purpose of this seminar is to critical review his interpretation of the Enlightenment. You might like to compare your own assessment of Gay by comparing it with some reviews of his work which appeared when it was first published.

Seminar Reading

Peter Gay, The Enlightenment: An Interpretation (New York: Norton, 1977), 2 vols.

Recommended Reading

Combined Retrospective Index to Book Reviews in Scholarly Journals, 1886-1974, vol. 4 F-Greef, ed. Evan Ira Farber et al. (Arlington: Carrollton Press, 1980).

Betty Behrens’ review of Gay, The Enlightenment in Historical Journal, 1968, vol. XI, pp. 190-5.

Review by Keith Michael Baker in the American Historical Review, 1970, 75, pp. 1410-14.

The Enlightenment: A Comprehensive Anthology, ed. Peter Gay (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1973).

Peter Gay, The Party of Humanity: Essays in the French Enlightenment (1964).