Jeremy Bentham, “Anarchical Fallacies; Being An Examination of the Declarations of Rights Issued During the French Revolution” (c. 1795)

|

|

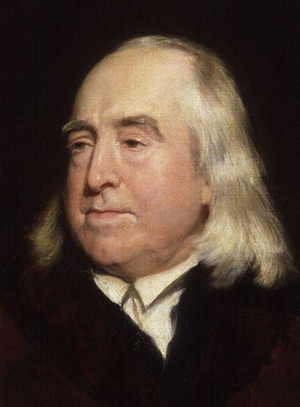

| Jeremy Bentham (1748-1832) |

This work is part of a collection by Jeremy Bentham.

Source

Jeremy Bentham, “Anarchical Fallacies; Being An Examination of the Declarations of Rights Issued During the French Revolution” (c. 1795) in The Works of Jeremy Bentham, published under the Superintendence of his Executor, John Bowring (Edinburgh: William Tait, 1838-1843). 11 vols. Vol. 2 (1843), pp. 489-534. See also the facs. PDF.

It was first published in French in 1840: Jeremy Bentham, Traités des sophismes politiques et des sophismes anarchiques. Extraits des manuscrits de Jérémie Bentham par Ét. Dumont (Bruxelles: Société Belge de Libraire, 1840). “Sophismes anarchiques,” pp. 243-340. See the facs. PDF.

Table of Contents

- ANARCHICAL FALLACIES; BEING AN EXAMINATION OF THE DECLARATIONS OF RIGHTS ISSUED DURING THE FRENCH REVOLUTION.

- ADVERTISEMENT.

- AN EXAMINATION OF THE DECLARATION OF THE RIGHTS OF THE MAN AND THE CITIZEN DECREED BY THE CONSTITUENT ASSEMBLY IN FRANCE.

- PREAMBLE.

- A CRITICAL EXAMINATION OF THE DECLARATION OF RIGHTS.

- PRELIMINARY OBSERVATIONS.

- Article I.: Men [all men] are born and remain free, and equal in respect of rights. Social distinctions cannot be founded, but upon common utility.

- Article II.: The end in view of every political association is the preservation of the natural and imprescriptible rights of man. These rights are liberty, property, security, and resistance to oppression.

- Article III.: The principle of every sovereignty [government] resides essentially in the nation. No body of men—no single individual—can exercise any authority which does not expressly issue from thence.

- Article IV.: Liberty consists in being able to do that which is not hurtful to another, and therefore the exercise of the natural rights of each man has no other bounds than those which insure to the other members of the society the enjoyment of the same rights. These bounds cannot be determined but by the law.

- Article V.: The law has no right to forbid any other actions than such as are hurtful to society. Whatever is not forbidden by the law, cannot be hindered; nor can any individual be compelled to do that which the law does not command.

- Article VI.: The law is the expression of the general will. Every citizen has the right of concurring in person, or by his representatives, in the formation of it: it ought to be the same for all, whether it protect, or whether it punish. All the citizens being equal in its eyes, are equally admissible to all dignities, public places, and employments, according to their capacity, and without any other distinction than that of their virtues and their talents.

- Article VII.: No one can be accused, arrested or detained, Edition: current; Page: [510] but in the cases determined by the law, and according to the forms prescribed by the law. Those who solicit, issue, execute, or cause to be executed, arbitrary orders, ought to be punished; but every citizen, summoned or arrested in virtue of the law, ought to obey that instant: he renders himself culpable by resistance.

- Article VIII.: The law ought not to establish any other punishments than such as are strictly and evidently necessary; and no one can be punished but in virtue of a law established and promulgated before the commission of the offence, and applied in a legal manner.

- Article IX.: Every individual being presumed innocent until he have been declared guilty,—if it be judged necessary to arrest him, every act of rigour which is not necessary to the making sure of his person, ought to be severely inhibited by the law.

- Article X.: No one ought to be molested [meaning, probably, by government] for his opinions, even in matters of religion, provided that the manisfestation of them does not disturb [better expressed perhaps by saying, except in as far as the manifestation of them disturb, or rather tends to the disturbance of] the public order established by the law.

- Article XI.: The free examination of thoughts and opinions is one of the most precious rights of man: every citizen may therefore speak, write, and print freely, provided always that he shall be answerable for the abuse of that liberty in the cases determined by the law.

- Article XII.: The guarantee of the rights of the man and of the citizen necessitates a public force: this force is therefore instituted for the advantage of all, and not for the particular utility [advantage] of those to whom it is intrusted.

- Article XIII.: For the maintenance of the public force, and for the expenses of administration, a common contribution is indispensable: it ought to be equally divided among all the citizens in proportion to their faculties.

- Article XIV.: All the citizens have the right to ascertain by themselves, or by their representatives, the necessity of the public contribution—to give their free consent to it—to follow up the aplication of it, and to determine the quantity of it, the objects on which it shall be levied, the mode of levying it and getting it in, and the duration of it.

- Article XV.: Society has a right to demand from every agent of the public, an account of his administration.

- Article XVI.: Every society in which the warranty of rights is not assured, [“la garantie des droits n’est pas assurée,”] nor the separation of powers determined, has no constitution.

- Article XVII.: Property being an inviolable and sacred right, no one can be deprived of it, unless it be when public necessity, legally established, evidently requires it [i. e. the sacrifice of it,] and under the condition of a just and previous indemnity.

- CONCLUSION.

- DECLARATION OF THE RIGHTS AND DUTIES OF THE MAN AND THE CITIZEN,

ANNO 1795.

- Rights.—Article I.: The rights of man in society are liberty, equality, security, and property.

- Article II.: Liberty consists in the power of doing that which hurts not the rights of others.

- Article III.: Sentence 1. Equality consists in this—that the law is the same for all, whether it protect or whether it punish.

- Article IV.: Security results from the concurrence of all in securing the rights of each.

- Article V.: Property is the right of enjoying and disposing of one’s goods—of one’s revenues—of the fruit of one’s labour and one’s industry.

- Article I., or Preamble.: The Declaration of Rights contains the obligations of legislators:—the maintenance of society requires that those who compose it, know and fulfil equally their duties.

- Article II.: All the duties of the man and the citizen are derived from these two principles, engraven by nature in all breasts, in the hearts of all men,—

- Article IV.: No one is a good citizen if he be not a good son, a good father, a good brother, a good friend, a good husband.

- Article V.: No man is a good man if he be not frankly and religiously an observer of the laws.

- Article VI.: He who openly violates the law, declares himself in a state of war with society.

- Article VII.: He who, without openly infringing the laws, eludes them by cunning or address, wounds the interests of all; he renders himself unworthy of their benevolence and their esteem.

- Article VIII.: On the maintenance of property rests the cultivation of the lands, all the productions, every means of labour, and the whole fabric of social order.

- Article IX.: Every citizen owes his services to his country, to the maintenance of liberty, equality, and property, as often as the law calls upon him to defend them.

- OBSERVATIONS ON PARTS OF THE DECLARATION OF RIGHTS, AS PROPOSED BY CITIZEN SIEYES.

- Endnotes

ANARCHICAL FALLACIES; BEING AN EXAMINATION OF THE DECLARATIONS OF RIGHTS ISSUED DURING THE FRENCH REVOLUTION.↩

ADVERTISEMENT.↩

The following papers are now first published in English, from Mr. Bentham’s MSS.; the substance of them has previously been published in French by Dumont.

[491]

AN EXAMINATION OF THE DECLARATION OF THE RIGHTS OF THE MAN AND THE CITIZEN DECREED BY THE CONSTITUENT ASSEMBLY IN FRANCE.↩

PREAMBLE.↩

“The Representatives of the French people, constituted in National Assembly, considering that ignorance, forgetfulness, or contempt of the Rights of Man, are the only causes of public calamities, and of the corruption of governments, have resolved to set forth in a solemn declaration, the natural, unalienable, and sacred rights of man, in order that this declaration, constantly presented to all the members of the body social, may recall to mind, without ceasing, their rights and their duties; to the end, that the acts of the legislative power, and those of the executive power, being capable at every instant of comparison with the end of every political institution, they may be more respected, and also that the demands of the citizens hereafter, founded upon simple and incontestable principles, may always tend to the maintenance of the constitution and to the happiness of all.”

“In consequence, the National Assembly acknowledges and declares, in the presence and under the auspices of the Supreme Being, the following Rights of the Man and the Citizen.”—

From this preamble we may collect the following positions:—

1. That the declaration in question ought to include a declaration of all the powers which it is designed should thereafter subsist in the State; the limits of each power precisely laid down, and every one completely distinguished from the other.

2. That the articles by which this is to be done, ought not to be loose and scattered, but closely connected into a whole, and the connexion all along made visible.

3. That the declaration of the rights of man, in a state preceding that of political society, ought to form a part of the composition in question, and constitute the first part of it.

4. That in point of fact, a clear idea of all these stands already imprinted in the minds of every man.

5. That, therefore, the object of such a draught is not, in any part of such a draught, to teach the people anything new.

6. But that the object of such a declaration is to declare the accession of the Assembly, as such, to the principles as understood and embraced, as well by themselves in their individual capacity, as by all other individuals in the State.

7. That the use of this solemn adoption and recognition is, that the principles recognised may serve as a standard by which the propriety of the several particular laws that are afterwards to be enacted in consequence, may be tried.

8. That by the conformity of these laws to this standard, the fidelity of the legislators to their trust is also to be tried.

9. That accordingly, if any law should hereafter be enacted, between which, and any of those fundamental articles, any want of conformity in any point can be pointed out, such want of conformity will be a conclusive proof of two things: 1. Of the impropriety of such law; 2. Of error or criminality on the part of the authors and adopters of that law.

It concerns me to see so respectable an Assembly hold out expectations, which, according to my conception, cannot in the nature of things be fulfilled.

An enterprise of this sort, instead of preceding the formation of a complete body of laws, supposes such a work to be already existing in every particular except that of its obligatory force.

No laws are ever to receive the sanction of the Assembly that shall be contrary in any point to these principles. What does this suppose? It supposes the several articles of detail that require to be enacted, to have been drawn up, to have been passed in review, to have been confronted with these fundamental articles, and to have been found in no respect [492] repugnant to them. In a word, to be sufficiently assured that the several laws of detail will bear this trying comparison, one thing is necessary: the comparison must have been made.

To know the several laws which the exigencies of mankind call for, a view of all these several exigencies must be obtained. But to obtain this view, there is but one possible means, which is, to take a view of the laws that have already been framed, and of the exigencies which have given birth to them.

To frame a composition which shall in any tolerable degree answer this requisition, two endowments, it is evident, are absolutely necessary:—an acquaintance with the law as it is, and the perspicuity and genius of the metaphysician: and these endowments must unite in the same person.

I can conceive but four purposes which a discourse, of the kind proposed under the name of a Declaration of Rights, can be intended to answer:—the setting bounds to the authority of the crown;—the setting bounds to the authority of the supreme legislative power, that of the National Assembly;—the serving as a general guide or set of instructions to the National Assembly itself, in the task of executing their function in detail, by the establishment of particular laws;—and the affording a satisfaction to the people.

These four purposes seem, if I apprehend right, to be all of them avowed by the same or different advocates for this measure.

Of the fourth and last of these purposes I shall say nothing: it is a question merely local—dependent upon the humour of the spot and of the day, of which no one at a distance can be a judge. Of the fitness of the end, there can be but one opinion: the only question is about the fitness of the means.

In the three other points of view, the expediency of the measure is more than I can perceive.

The description of the persons, of whose rights it is to contain the declaration, is remarkable. Who are they? The French nation? No; not they only, but all citizens, and all men. By citizens, it seems we are to understand men engaged in political society: by men, persons not yet engaged in political society—persons as yet in a state of nature.

The word men, as opposed to citizens, I had rather not have seen. In this sense, a declaration of the rights of men is a declaration of the rights which human creatures, it is supposed, would possess, were they in a state in which the French nation certainly are not, nor perhaps any other; certainly no other into whose hands this declaration could ever come.

This instrument is the more worthy of attention, especially of the attention of a foreigner, inasmuch as the rights which it is to declare are the rights which it is supposed belong to the members of every nation in the globe. As a member of a nation which with relation to the French comes under the name of a foreign one, I feel the stronger call to examine this declaration, inasmuch as in this instrument I am invited to read a list of rights which belong as much to me as to the people for whose more particular use it has been framed.

The word men, I observe to be all along coupled in the language of the Assembly itself, with the word citizen. I lay it, therefore, out of the question, and consider the declaration in the same light in which it is viewed by M. Turgot, as that of a declaration of the rights of all men in a state of citizenship or political society.

I proceed, then, to consider it in the three points of view above announced:—

1. Can it be of use for the purpose of setting bounds to the power of the crown? No; for that is to be the particular object of the Constitutional Code itself, from which this preliminary part is detached in advance.

2. Can it be of use for the purpose of setting bounds to the power of the several legislative bodies established or to be established? I answer, No.

(1.) Not of any subordinate ones: for of their authority, the natural and necessary limit is that of the supreme legislature, the National Assembly.

(2.) Not of the National Assembly itself:—Why? 1. Such limitation is unnecessary. It is proposed, and very wisely and honestly, to call in the body of the people, and give it as much power and influence as in its nature it is capable of: by enabling it to declare its sentiments whenever it thinks proper, whether immediately, or through the channel of the subordinate assemblies. Is a law enacted or proposed in the National Assembly, which happens not to be agreeable to the body of the people? It will be equally censured by them, whether it be conceived, or not, to bear marks of a repugnancy to this declaration of rights. Is a law disagreeable to them? They will hardly think themselves precluded from expressing their disapprobation, by the circumstance of its not being to be convicted of repugnancy to that instrument; and though it should be repugnant to that instrument, they will see little need to resort to that instrument for the ground of their repugnancy; they will find a much nearer ground in some particular real or imaginary inconvenience.

In short, when you have made such provision, that the supreme legislature can never carry any point against the general and persevering opinion of the people, what would you have more? What use in their attempting to bind themselves by a set of phrases [493] of their own contrivance? The people’s pleasure: that is the only check to which no other can add anything, and which no other can supersede.

In regard to the rights thus declared, mention will either be made of the exceptions and modifications that may be made to them by the laws themselves, or there will not. In the former case, the observance of the declaration will be impracticable; nor can the law in its details stir a step without flying in the face of it. In the other case, it fails thereby altogether of its only object, the setting limits to the exercise of the legislative power. Suppose a declaration to this effect:—no man’s liberty shall be abridged in any point. This, it is evident, would be an useless extravagance, which must be contradicted by every law that came to be made. Suppose it to say—no man’s liberty shall be abridged, but in such points as it shall be abridged in, by the law. This, we see, is saying nothing: it leaves the law just as free and unfettered as it found it.

Between these two rocks lies the only choice which an instrument destined to this purpose can have. Is an instrument of this sort produced? We shall see it striking against one or other of them in every line. The first is what the framers will most guard against, in proportion to their reach of thought, and to their knowledge in this line: when they hit against the other, it will be by accident and unawares.

Lastly, it cannot with any good effect answer the only remaining intention, viz. that of a check to restrain as well as to guide the legislature itself, in the penning of the laws of detail that are to follow.

The mistake has its source in the current logic, and in the want of attention to the distinction between what is first in the order of demonstration, and what is first in the order of invention. Principles, it is said, ought to precede consequences; and the first being established, the others will follow of course. What are the principles here meant? General propositions, and those of the widest extent. What by consequences? Particular propositions, included under those general ones.

That this order is favourable to demonstration, if by demonstration be meant personal debate and argumentation, is true enough. Why? Because, if you can once get a man to admit the general proposition, he cannot, without incurring the reproach of inconsistency, reject a particular proposition that is included in it.

But, that this order is not the order of conception, of investigation, of invention, is equally undeniable. In this order, particular propositions always precede general ones. The assent to the latter is preceded by and grounded on the assent to the former.

If we prove the consequences from the principle, it is only from the consequences that we learn the principle.

Apply this to laws. The first business, according to the plan I am combating, is to find and declare the principles: the laws of a fundamental nature: that done, it is by their means that we shall be enabled to find the proper laws of detail. I say, no: it is only in proportion as we have formed and compared with one another the laws of detail, that our fundamental laws will be exact and fit for service. Is a general proposition true? It is because all the particular propositions that are included under it are true. How, then, are we to satisfy ourselves of the truth of the general one? By having under our eye all the included particular ones. What, then, is the order of investigation by which true general propositions are formed? We take a number of less extensive—of particular propositions; find some points in which they agree, and from the observation of these points form a more extensive one, a general one, in which they are all included. In this way, we proceed upon sure grounds, and understand ourselves as we go: in the opposite way, we proceed at random, and danger attends every step.

No law is good which does not add more to the general mass of felicity than it takes from it. No law ought to be made that does not add more to the general mass of felicity than it takes from it. No law can be made that does not take something from liberty; those excepted which take away, in the whole or in part those laws which take from liberty. Propositions to the first effect I see are true without any exception: propositions to the latter effect I see are not true till after the particular propositions intimated by the exceptions are taken out of it. These propositions I have attained a full satisfaction of the truth of. How? By the habit I have been in for a course of years, of taking any law at pleasure, and observing that the particular proposition relative to that law was always conformable to the fact announced by the general one.

So in the other example. I discerned in the first instance, in a faint way, that two classes would serve to comprehend all laws: laws which take from liberty in their immediate operation, and laws which in the same way destroy, in part or in the whole, the operation of the former. The perception was at first obscure, owing to the difficulty of ascertaining what constituted in every case a law, and of tracing out its operation. By repeated trials, I came at last to be able to show of any law which offered itself, that it came under one or other of those classes.

What follows? That the proper order is—first to digest the laws of detail, and when [494] they are settled and found to be fit for use, then, and not till then, to select and frame in terminis, by abstraction, such propositions as may be capable of being given without self-contradiction as fundamental laws.

What is the source of this premature anxiety to establish fundamental laws? It is the old conceit of being wiser than all posterity—wiser than those who will have had more experience,—the old desire of ruling over posterity—the old recipe for enabling the dead to chain down the living. In the case of a specific law, the absurdity of such a notion is pretty well recognised, yet there the absurdity is much less than here. Of a particular law, the nature may be fully comprehended—the consequences foreseen: of a general law, this is the less likely to be the case, the greater the degree in which it possesses the quality of a general one. By a law of which you are fully master, and see clearly to the extent of, you will not attempt to bind succeeding legislators: the law you pitch upon in preference for this purpose, is one which you are unable to see to the end of.

Ought no such general propositions, then, to be ever framed till after the establishment of a complete code? I do not mean to assert this; on the contrary, in morals as in physics, nothing is to be done without them. The more they are framed and tried, the better: only, when framed, they ought to be well tried before they are ushered abroad into the world in the character of laws. In that character they ought not to be exhibited till after they have been confronted with all the particular laws to which the force of them is to apply. But if the intention be to chain down the legislator, these will be all the laws without exception which are looked upon as proper to be inserted in the code. For the interdiction meant to be put upon him is unlimited: he is never to establish any law which shall disagree with the pattern cut out for him—which shall ever trench upon such and such rights.

Such indigested and premature establishments betoken two things:—the weakness of the understanding, and the violence of the passions: the weakness of the understanding, in not seeing the insuperable incongruities which have been above stated—the violence of the passions, which betake themselves to such weapons for subduing opposition at any rate, and giving to the will of every man who embraces the proposition imported by the article in question, a weight beyond what is its just and intrinsic due. In vain would man seek to cover his weakness by positive and assuming language: the expression of one opinion, the expression of one will, is the utmost that any proposition can amount to. Ought and ought not, can and can not, shall and shall not, all put together, can never amount to anything more. “No law ought to be made, which will lessen upon the whole the mass of general felicity.” When I, a legislator or private citizen, say this, what is the simple matter of fact that is expressed? This, and this only, that a sentiment of dissatisfaction is excited in my breast by any such law. So again—“No law shall be made, which will lessen upon the whole the mass of general felicity.” What does this signify? That the sentiment of dissatisfaction in me is so strong as to have given birth to a determined will that no such law should ever pass, and that determination so strong as to have produced a resolution on my part to oppose myself, as far as depends on me, to the passing of it, should it ever be attempted—a determination which is the more likely to meet with success, in proportion to the influence, which in the character of legislator or any other, my mind happens to possess over the minds of others.

“No law can be made which will do as above. What does this signify? The same will as before, only wrapped up in an absurd and insidious disguise. My will is here so strong, that, as a means of seeing it crowned with success, I use my influence with the persons concerned to persuade them to consider a law which, at the same time, I suppose to be made, in the same point of view as if it were not made; and consequently, to pay no more obedience to it than if it were the command of an unauthorized individual. To compass this design, I make the absurd choice of a term expressive in its original and proper import of a physical impossibility, in order to represent as impossible the very event of the occurrence of which I am apprehensive:—occupied with the contrary persuasion, I raise my voice to the people—tell them the thing is impossible; and they are to have the goodness to believe me, and act in consequence.

A law to the effect in question is a violation of the natural and indefeasible rights of man. What does this signify? That my resolution of using my utmost influence in opposition to such a law is wound up to such a pitch, that should any law be ever enacted, which in my eyes appears to come up to that description, my determination is, to behave to the persons concerned in its enactment, as any man would behave towards those who had been guilty of a notorious and violent infraction of his rights. If necessary, I would corporally oppose them—if necessary, in short, I would endeavour to kill them; just as, to save my own life, I would endeavour to kill any one who was endeavouring to kill me.

These several contrivances for giving to an increase in vehemence, the effect of an increase in strength of argument, may be styled bawling upon paper: it proceeds from [495] the same temper and the same sort of distress as produces bawling with the voice.

That they should be such efficacious recipes is much to be regretted; that they will always be but too much so, is much to be apprehended; but that they will be less and less so, as intelligence spreads and reason matures, is devoutly to be wished, and not unreasonably to be hoped for.

As passions are contagious, and the bulk of men are more guided by the opinions and pretended opinions of others than by their own, a large share of confidence, with a little share of argument, will he apt to go farther than all the argument in the world without confidence: and hence it is, that modes of expression like these, which owe the influence they unhappily possess to the confidence they display, have met with such general reception. That they should fall into discredit, is, if the reasons above given have any force, devoutly to be wished: and for the accomplishing this good end, there cannot be any method so effectual—or rather, there cannot be any other method, than that of unmasking them in the manner here attempted.

The phrases can and can not, are employed in this way with greater and more pernicious effect, inasmuch as, over and above physical and moral impossibility, they are made use of with much less impropriety and violence to denote legal impossibility. In the language of the law, speaking in the character of the law, they are used in this way without ambiguity or inconvenience. “Such a magistrate cannot do so and so,” that is, he has no power to do so and so. If he issue a command to such an effect, it is no more to be obeyed than if it issued from any private person. But when the same expression is applied to the very power which is acknowledged to be supreme, and not limited by any specific institution, clouds of ambiguity and confusion roll on in a torrent almost impossible to be withstood. Shuffled backwards and forwards amidst these three species of impossibility—physical, legal, and moral—the mind can find no resting-place: it loses its footing altogether, and becomes an easy prey to the violence which wields these arms.

The expedient is the more powerful, inasmuch as, where it does not succeed so far as to gain a man and carry him over to that side, it will perplex him and prevent his finding his way to the other: it will leave him neutral, though it should fail of making him a friend.

It is the better calculated to produce this effect, inasmuch as nothing can tend more powerfully to draw a man altogether out of the track of reason and out of sight of utility, the only just standard for trying all sorts of moral questions. Of a positive assertion thus irrational, the natural effect, where it fails of producing irrational acquiescence, is to produce equally irrational denial, by which no light is thrown upon the subject, nor any opening pointed out through which light may come. I say, the law cannot do so and so: you say, it can. When we have said thus much on each side, it is to no purpose to say more; there we are completely at a stand: argument such as this can go no further on either side,—or neither yields,—or passion triumphs alone—the stronger sweeping the weaker away.

Change the language, and instead of cannot, put ought not,—the case is widely different. The moderate expression of opinion and will intimated by this phrase, leads naturally to the inquiry after a reason:—and this reason, if there be any at bottom that deserves the name, is always a proposition of fact relative to the question of utility. Such a law ought not to be established, because it is not consistent with the general welfare—its tendency is not to add to the general stock of happiness. I say, it ought not to be established; that is, I do not approve of its being established: the emotion excited in my mind by the idea of its establishment, is not that of satisfaction, but the contrary. How happens this? Because the production of inconvenience, more than equivalent to any advantage that will ensue, presents itself to my conception in the character of a probable event. Now the question is put, as every political and moral question ought to be, upon the issue of fact; and manking are directed into the only true track of investigation which can afford instruction or hope of rational argument, the track of experiment and observation. Agreement, to be sure, is not even then made certain:—for certainty belongs not to human affairs. But the track, which of all others bids fairest for leading to agreement, is pointed out: a clue for bringing back the travellers, in case of doubt or difficulty, is presented; and, at any rate, they are not struck motionless at the first step.

Nothing would be more unjust or more foreign to my design, than taking occasion, from anything that has been said, to throw particular blame upon particular persons: reproach which strikes everybody, hurts nobody; and common error, where it does not, according to the maxim of English law, produce common right, is productive at least of common exculpation.

[496]

A CRITICAL EXAMINATION OF THE DECLARATION OF RIGHTS.↩

PRELIMINARY OBSERVATIONS.↩

The Declaration of Rights—I mean the paper published under that name by the French National Assembly in 1791—assumes for its subject-matter a field of disquisition as unbounded in point of extent as it is important in its nature. But the more ample the extent given to any proposition or string of propositions, the more difficult it is to keep the import of it confined without deviation, within the bounds of truth and reason. If in the smallest corners of the field it ranges over, it fail of coinciding with the line of rigid rectitude, no sooner is the aberration pointed out, than (inasmuch as there is no medium between truth and falsehood) its pretensions to the appellation of a truism are gone, and whoever looks upon it must recognise it to be false and erroneous,—and if, as here, political conduct be the theme, so far as the error extends and fails of being detected, pernicious.

In a work of such extreme importance with a view to practice, and which throughout keeps practice so closely and immediately and professedly in view, a single error may be attended with the most fatal consequences. The more extensive the propositions, the more consummate will be the knowledge, the more exquisite the skill, indispensably requisite to confine them in all points within the pale of truth. The most consummate ability in the whole nation could not have been too much for the task—one may venture to say, it would not have been equal to it. But that, in the sanctioning of each proposition, the most consummate ability should happen to be vested in the heads of the sorry majority in whose hands the plenitude of power happened on that same occasion to be vested, is an event against which the chances are almost as infinity to one.

Here, then, is a radical and all-pervading error—the attempting to give to a work on such a subject the sanction of government; especially of such a government—a government composed of members so numerous, so unequal in talent, as well as discordant in inclinations and affections. Had it been the work of a single hand, and that a private one, and in that character given to the world, every good effect would have been produced by it that could be produced by it when published as the work of government, without any of the bad effects which in case of the smallest error must result from it when given as the work of government.

The revolution, which threw the government into the hands of the penners and adopters of this declaration, having been the effect of insurrection, the grand object evidently is to justify the cause. But by justifying it, they invite it: in justifying past insurrection, they plant and cultivate a propensity to perpetual insurrection in time future; they sow the seeds of anarchy broad-cast: in justifying the demolition of existing authorities, they undermine all future ones, their own consequently in the number. Shallow and reckless vanity!—They imitate in their conduct the author of that fabled law, according to which the assassination of the prince upon the throne gave to the assassin a title to succeed him. “People, behold your rights! If a single article of them be violated, insurrection is not your right only, but the most sacred of your duties.” Such is the constant language, for such is the professed object of this source and model of all laws—this self-consecrated oracle of all nations.

The more abstract—that is, the more extensive the proposition is, the more liable is it to involve a fallacy. Of fallacies, one of the most natural modifications is that which is called begging the question—the abuse of making the abstract proposition resorted to for proof, a lever for introducing, in the company of other propositions that are nothing to the purpose, the very proposition which is admitted to stand in need of proof.

Is the provision in question fit in point of expediency to be passed into a law for the government of the French nation? That, mutatis mutandis, would have been the question put in England: that was the proper question to have been put in relation to each provision it was proposed should enter into the composition of the body of French laws.

[497]Instead of that, as often as the utility of a provision appeared (by reason of the wideness of its extent, for instance) of a doubtful nature, the way taken to clear the doubt was to assert it to be a provision fit to be made law for all men—for all Frenchmen—and for all Englishmen, for example, into the bargain. This medium of proof was the more alluring, inasmuch as to the advantage of removing opposition, was added the pleasure, the sort of titillation so exquisite to the nerve of vanity in a French heart—the satisfaction, to use a homely, but not the less apposite proverb, of teaching grandmothers to suck eggs. Hark! ye citizens of the other side of the water! Can you tell us what rights you have belonging to you? No, that you can’t. It’s we that understand rights: not our own only, but yours into the bargain; while you, poor simple souls! know nothing about the matter.

Hasty generalization, the great stumblingblock of intellectual vanity!—hasty generalization, the rock that even genius itself is so apt to split upon!—hasty generalization, the bane of prudence and of science!

In the British Houses of Parliament, more especially in the most efficient house for business, there prevails a well-known jealousy of, and repugnance to, the voting of abstract propositions. This jealousy is not less general than reasonable. A jealousy of abstract propositions is an aversion to whatever is beside the purpose—an aversion to impertinence.

The great enemies of public peace are the selfish and dissocial passions:—necessary as they are—the one to the very existence of each individual, the other to his security. On the part of these affections, a deficiency in point of strength is never to be apprehended: all that is to be apprehended in respect of them, is to be apprehended on the side of their excess. Society is held together only by the sacrifices that men can be induced to make of the gratifications they demand: to obtain these sacrifices is the great difficulty, the great task of government. What has been the object, the perpetual and palpable object, of this declaration of pretended rights? To add as much force as possible to these passions, already but too strong,—to burst the cords that hold them in,—to say to the selfish passions, there—everywhere—is your prey!—to the angry passions, there—everywhere—is your enemy.

Such is the morality of this celebrated manifesto, rendered famous by the same qualities that gave celebrity to the incendiary of the Ephesian temple.

The logic of it is of a piece with its morality:—a perpetual vein of nonsense, flowing from a perpetual abuse of words,—words having a variety of meanings, where words with single meanings were equally at hand—the same words used in a variety of meanings in the same page,—words used in meanings not their own, where proper words were equally at hand,—words and propositions of the most unbounded signification, turned loose without any of those exceptions or modifications which are so necessary on every occasion to reduce their import within the compass, not only of right reason, but even of the design in hand, of whatever nature it may be;—the same inaccuracy, the same inattention in the penning of this cluster of truths on which the fate of nations was to hang, as if it had been an oriental tale, or an allegory for a magazine:—stale epigrams, instead of necessary distinctions,—figurative expressions preferred to simple ones,—sentimental conceits, as trite as they are unmeaning, preferred to apt and precise expressions,—frippery ornament preferred to the majestic simplicity of good sound sense,—and the acts of the senate loaded and disfigured by the tinsel of the playhouse.

In a play or a novel, an improper word is but a word: and the impropriety, whether noticed or not, is attended with no consequences. In a body of laws—especially of laws given as constitutional and fundamental ones—an improper word may be a national calamity:—and civil war may be the consequence of it. Out of one foolish word may start a thousand daggers.

Imputations like these may appear general and declamatory—and rightly so, if they stood alone: but they will be justified even to satiety by the details that follow. Scarcely an article, which in rummaging it, will not be found a true Pandora’s box.

In running over the several articles, I shall on the occasion of each article point out, in the first place, the errors it contains in theory; and then, in the second place, the mischiefs it is pregnant with in practice.

The criticism is verbal:—true, but what else can it be? Words—words without a meaning, or with a meaning too flatly false to be maintained by anybody, are the stuff it is made of. Look to the letter, you find nonsense—look beyond the letter, you find nothing.

Article I.: Men [all men] are born and remain free, and equal in respect of rights. Social distinctions cannot be founded, but upon common utility.↩

In this article are contained, grammatically speaking, two distinct sentences. The first is full of error, the other of ambiguity.

In the first are contained four distinguishable propositions, all of them false—all of them notoriously and undeniably false:—

1. That all men are born free.

2. That all men remain free.

[498]3. That all men are born equal in rights.

4. That all men remain (i. e. remain for ever, for the proposition is indefinite and unlimited) equal in rights.

All men are born free? All men remain free? No, not a single man: not a single man that ever was, or is, or will be. All men, on the contrary, are born in subjection, and the most absolute subjection—the subjection of a helpless child to the parents on whom he depends every moment for his existence. In this subjection every man is born—in this subjection he continues for years—for a great number of years—and the existence of the individual and of the species depends upon his so doing.

What is the state of things to which the supposed existence of these supposed rights is meant to bear reference?—a state of things prior to the existence of government, or a state of things subsequent to the existence of government? If to a state prior to the existence of government, what would the existence of such rights as these be to the purpose, even if it were true, in any country where there is such a thing as government? If to a state of things subsequent to the formation of government—it in a country where there is a government, in what single instance—in the instance of what single government, is it true? Setting aside the case of parent and child, let any man name that single government under which any such equality is recognised.

All men born free? Absurd and miserable nonsense! When the great complaint—a complaint made perhaps by the very same people at the same time, is—that so many men are born slaves. Oh! but when we acknowledge them to be born slaves, we refer to the laws in being; which laws being void, as being contrary to those laws of nature which are the efficient causes of those rights of man that we are declaring, the men in question are free in one sense, though slaves in another;—slaves, and free, at the same time:—free in respect of the laws of nature—slaves in respect of the pretended human laws, which, though called laws, are no laws at all, as being contrary to the laws of nature. For such is the difference—the great and perpetual difference, betwixt the good subject, the rational censor of the laws, and the anarchist—between the moderate man and the man of violence. The rational censor, acknowledging the existence of the law he disapproves, proposes the repeal of it: the anarchist, setting up his will and fancy for a law before which all mankind are called upon to bow down at the first word—the anarchist, trampling on truth and decency, denies the validity of the law in question,—denies the existence of it in the character of a law, and calls upon all mankind to rise up in a mass, and resist the execution of it.

Whatever is, is,—was the maxim of Des-Cartes, who looked upon it as so sure, as well as so instructive a truth, that everything else which goes by the name of truth might be deduced from it. The philosophical vortex-maker—who, however mistaken in his philosophy and his logic, was harmless enough at least—the manufacturer of identical propositions and celestial vortices—little thought how soon a part of his own countrymen, fraught with pretensions as empty as his own, and as mischievous as his were innocent, would contest with him even this his favourite and fundamental maxim, by which everything else was to be brought to light. Whatever is, is not—is the maxim of the anarchist, as often as anything comes across him in the shape of a law which he happens not to like.

“Cruel is the judge,” says Lord Bacon, “who, in order to enable himself to torture men, applies torture to the law.” Still more cruel is the anarchist, who, for the purpose of effecting the subversion of the laws themselves, as well as the massacre of the legislators, tortures not only the words of the law, but the very vitals of the language.

All men are born equal in rights. The rights of the heir of the most indigent family equal to the rights of the heir of the most wealthy? In what case is this true? I say nothing of hereditary dignities and powers. Inequalities such as these being proscribed under and by the French government in France, are consequently proscribed by that government under every other government, and consequently have no existence anywhere. For the total subjection of every other government to French government, is a fundamental principle in the law of universal independence—the French law. Yet neither was this true at the time of issuing this Declaration of Rights, nor was it meant to be so afterwards. The 13th article, which we shall come to in its place, proceeds on the contrary supposition: for, considering its other attributes, inconsistency could not be wanting to the list. It can scarcely be more hostile to all other laws than it is at variance with itself.

All men (i. e. all human creatures of both sexes) remain equal in rights. All men, meaning doubtless all human creatures. The apprentice, then, is equal in rights to his master; he has as much liberty with relation to the master, as the master has with relation to him; he has as much right to command and to punish him; he is as much owner and master of the master’s house, as the master himself. The case is the same as between ward and guardian. So again as between wife and husband. The madman has as good a right to confine anybody else, as anybody else has to confine him. The idiot has as much right to govern everybody, as anybody can have to govern him. The physician and the nurse, when called in by the next friend [499] of a sick man seized with a delirium, have no more right to prevent his throwing himself out of the window, than he has to throw them out of it. All this is plainly and incontestably included in this article of the Declaration of Rights: in the very words of it, and in the meaning—if it have any meaning. Was this the meaning of the authors of it?—or did they mean to admit this explanation as to some of the instances, and to explain the article away as to the rest? Not being idiots, nor lunatics, nor under a delirium, they would explain it away with regard to the madman, and the man under a delirium. Considering that a child may become an orphan as soon as it has seen the light, and that in that case, if not subject to government, it must perish, they would explain it away, I think, and contradict themselves, in the case of guardian and ward. In the case of master and apprentice, I would not take upon me to decide: it may have been their meaning to proscribe that relation altogether;—at least, this may have been the case, as soon as the repugnancy between that institution and this oracle was pointed out; for the professed object and destination of it is to be the standard of truth and falsehood, of right and wrong, in everything that relates to government. But to this standard, and to this article of it, the subjection of the apprentice to the master is flatly and diametrically repugnant. If it do not proscribe and exclude this inequality, it proscribes none: if it do not do this mischief, it does nothing.

So, again, in the case of husband and wife. Amongst the other abuses which the oracle was meant to put an end to, may, for aught I can pretend to say, have been the institution of marriage. For what is the subjection of a small and limited number of years, in comparison of the subjection of a whole life? Yet without subjection and inequality, no such institution can by any possibility take place; for of two contradictory wills, both cannot take effect at the same time.

The same doubts apply to the case of master and hired servant. Better a man should starve than hire himself;—better half the species starve, than hire itself out to service. For, where is the compatibility between liberty and servitude? How can liberty and servitude subsist in the same person? What good citizen is there, that would hesitate to die for liberty? And, as to those who are not good citizens, what matters it whether they live or starve? Besides that every man who lives under this constitution being equal in rights, equal in all sorts of rights, is equal in respect to rights of property. No man, therefore, can be in any danger of starving—no man can have so much as that motive, weak and inadequate as it is, for hiring himself out to service.

Sentence 2. Social distinctions cannot be founded but upon common utility.—This proposition has two or three meanings. According to one of them, the proposition is notoriously false: according to another, it is in contradiction to the four propositions that preceded it in the same sentence.

What is meant by social distinctions? what is meant by can? what is meant by founded?

What is meant by social distinctions?—Distinctions not respecting equality?—then these are nothing to the purpose. Distinctions in respect of equality?—then, consistently with the preceding propositions in this same article, they can have no existence: not existing, they cannot be founded upon anything. The distinctions above exemplified, are they in the number of the social distinctions here intended? Not one of them (as we have been seeing,) but has subjection—not one of them, but has inequality for its very essence.

What is meant by can—can not be founded but upon common utility? Is it meant to speak of what is established, or of what ought to be established? Does it mean that no social distinctions, but those which it approves as having the foundation in question, are established anywhere? or simply that none such ought to be established anywhere? or that, if the establishment or maintenance of such dispositions by the laws be attempted anywhere, such laws ought to be treated as void, and the attempt to execute them to be resisted? For such is the venom that lurks under such words as can and can not, when set up as a check upon the laws,—they contain all these three so perfectly distinct and widely different meanings. In the first, the proposition they are inserted into refers to practice, and makes appeal to observation—to the observation of other men, in regard to a matter of fact: in the second, it is an appeal to the approving faculty of others, in regard to the same matter of fact: in the third, it is no appeal to anything, or to anybody, but a violent attempt upon the liberty of speech and action on the part of others, by the terrors of anarchical despotism, rising up in opposition to the laws: it is an attempt to lift the dagger of the assassin against all individuals who presume to hold an opinion different from that of the orator or the writer, and against all governments which presume to support any such individuals in any such presumption. In the first of these imports, the proposition is perfectly harmless: but it is commonly so untrue, so glaringly untrue, so palpably untrue, even to drivelling, that it must be plain to everybody it can never have been the meaning that was intended.

In the second of these imports, the proposition may be true or not, as it may happen, and at any rate is equally innocent: but it is [500] such as will not answer the purpose; for an opinion that leaves others at liberty to be of a contrary one, will never answer the purpose of the passions: and if this had been the meaning intended, not this ambiguous phraseology, but a clear and simple one, presenting this meaning and no other, would have been employed. The third, which may not improperly be termed the ruffian-like or threatening import, is the meaning intended to be presented to the weak and timid, while the two innocent ones, of which one may even be reasonable, are held up before it as a veil to blind the eyes of the discerning reader, and screen from him the mischief that lurks beneath.

Can and can not, when thus applied—can and can not, when used instead of ought and ought not—can and can not, when applied to the binding force and effect of laws—not of the acts of individuals, nor yet of the acts of subordinate authority, but of the acts of the supreme government itself, are the disguised cant of the assassin: after them there is nothing but do him, betwixt the preparation for murder and the attempt. They resemble that instrument which in outward appearance is but an ordinary staff, but which within that simple and innocent semblance conceals a dagger. These are the words that speak daggers—if daggers can be spoken: they speak daggers, and there remains nothing but to use them.

Look where I will, I see but too many laws, the alteration or abolition of which, would in my poor judgment be a public blessing. I can conceive some,—to put extreme and scarcely exampled cases,—to which I might be inclined to oppose resistance, with a prospect of support such as promised to be effectual. But to talk of what the law, the supreme legislature of the country, acknowledged as such, can not do!—to talk of a void law as you would of a void order or a void judgment!—The very act of bringing such words into conjunction is either the vilest of nonsense, or the worst of treasons:—treason, not against one branch of the sovereignty, but against the whole: treason, not against this or that government, but against all governments.

Article II.: The end in view of every political association is the preservation of the natural and imprescriptible rights of man. These rights are liberty, property, security, and resistance to oppression.↩

Sentence 1. The end in view of every political association, is the preservation of the natural and imprescriptible rights of man.

More confusion—more nonsense,—and the nonsense, as usual, dangerous nonsense. The words can scarcely be said to have a meaning: but if they have, or rather if they had a meaning, these would be the propositions either asserted or implied:—

1. That there are such things as rights anterior to the establishment of governments: for natural, as applied to rights, if it mean anything, is meant to stand in opposition to legal—to such rights as are acknowledged to owe their existence to government, and are consequently posterior in their date to the establishment of government.

2. That these rights can not be abrogated by government: for can not is implied in the form of the word imprescriptible, and the sense it wears when so applied, is the cut-throat sense above explained.

3. That the governments that exist derive their origin from formal associations, or what are now called conventions: associations entered into by a partnership contract, with all the members for partners,—entered into at a day prefixed, for a predetermined purpose, the formation of a new government where there was none before (for as to formal meetings holden under the controul of an existing government, they are evidently out of question here) in which it seems again to be implied in the way of inference, though a necessary and an unavoidable inference, that all governments (that is, self-called governments, knots of persons exercising the powers of government) that have had any other origin than an association of the above description, are illegal, that is, no governments at all; resistance to them, and subversion of them, lawful and commendable; and so on.

Such are the notions implied in this first part of the article. How stands the truth of things? That there are no such things as natural rights—no such things as rights anterior to the establishment of government—no such things as natural rights opposed to, in contradistinction to, legal: that the expression is merely figurative; that when used, in the moment you attempt to give it a literal meaning it leads to error, and to that sort of error that leads to mischief—to the extremity of mischief.

We know what it is for men to live without government—and living without government, to live without rights: we know what it is for men to live without government, for we see instances of such a way of life—we see it in many savage nations, or rather races of mankind; for instance, among the savages of New South Wales, whose way of living is so well known to us: no habit of obedience, and thence no government—no government, and thence no laws—no laws, and thence no such things as rights—no security—no property:—liberty, as against regular controul, the controul of laws and government—perfect; but as against all irregular controul, the mandates of stronger individuals, none. In this state, at a time earlier than the commencement [501] of history—in this same state, judging from analogy, we, the inhabitants of the part of the globe we call Europe, were;—no government, consequently no rights: no rights, consequently no property—no legal security—no legal liberty: security not more than belongs to beasts—forecast and sense of insecurity keener—consequently in point of happiness below the level of the brutal race.

In proportion to the want of happiness resulting from the want of rights, a reason exists for wishing that there were such things as rights. But reasons for wishing there were such things as rights, are not rights;—a reason for wishing that a certain right were established, is not that right—want is not supply—hunger is not bread.

That which has no existence cannot be destroyed—that which cannot be destroyed cannot require anything to preserve it from destruction. Natural rights is simple nonsense: natural and imprescriptible rights, rhetorical nonsense,—nonsense upon stilts. But this rhetorical nonsense ends in the old strain of mischievous nonsense: for immediately a list of these pretended natural rights is given, and those are so expressed as to present to view legal rights. And of these rights, whatever they are, there is not, it seems, any one of which any government can, upon any occasion whatever, abrogate the smallest particle.

So much for terrorist language. What is the language of reason and plain sense upon this same subject? That in proportion as it is right or proper, i. e. advantageous to the society in question, that this or that right—a right to this or that effect—should be established and maintained, in that same proportion it is wrong that it should be abrogated: but that as there is no right, which ought not to be maintained so long as it is upon the whole advantageous to the society that it should be maintained, so there is no right which, when the abolition of it is advantageous to society, should not be abolished. To know whether it would be more for the advantage of society that this or that right should be maintained or abolished, the time at which the question about maintaining or abolishing is proposed, must be given, and the circumstances under which it is proposed to maintain or abolish it; the right itself must be specifically described, not jumbled with an undistinguishable heap of others, under any such vague general terms as property, liberty, and the like.

One thing, in the midst of all this confusion, is but too plain. They know not of what they are talking under the name of natural rights, and yet they would have them imprescriptible—proof against all the power of the laws—pregnant with occasions summoning the members of the community to rise up in resistance against the laws. What, then, was their object in declaring the existence of imprescriptible rights, and without specifying a single one by any such mark as it could be known by? This and no other—to excite and keep up a spirit of resistance to all laws—a spirit of insurrection against all governments—against the governments of all other nations instantly,—against the government of their own nation—against the government they themselves were pretending to establish—even that, as soon as their own reign should be at an end. In us is the perfection of virtue and wisdom: in all mankind besides, the extremity of wickedness and folly. Our will shall consequently reign without controul, and for ever: reign now we are living—reign after we are dead.

All nations—all future ages—shall be, for they are predestined to be, our slaves.

Future governments will not have honesty enough to be trusted with the determination of what rights shall be maintained, what abrogated—what laws kept in force, what repealed. Future subjects (I should say future citizens, for French government does not admit of subjects) will not have wit enough to be trusted with the choice whether to submit to the determination of the government of their time, or to resist it. Governments, citizens—all to the end of time—all must be kept in chains.

Such are their maxims—such their premises—for it is by such premises only that the doctrine of imprescriptible rights and unrepealable laws can be supported.

What is the real source of these imprescriptible rights—these unrepealable laws? Power turned blind by looking from its own height: self-conceit and tyranny exalted into insanity. No man was to have any other man for a servant, yet all men were forever to be their slaves. Making laws with imposture in their mouths, under pretence of declaring them—giving for laws anything that came uppermost, and these unrepealable ones, on pretence of finding them ready made. Made by what? Not by a God—they allow of none; but by their goddess, Nature.

The origination of governments from a contract is a pure fiction, or in other words, a falsehood. It never has been known to be true in any instance; the allegation of it does mischief, by involving the subject in error and confusion, and is neither necessary nor useful to any good purpose.

All governments that we have any account of have been gradually established by habit, after having been formed by force; unless in the instance of governments formed by individuals who have been emancipated, or have emancipated themselves, from governments already formed, the governments under which [502] they were born—a rare case, and from which nothing follows with regard to the rest. What signifies it how governments are formed? Is it the less proper—the less conducive to the happiness of society—that the happiness of society should be the one object kept in view by the members of the government in all their measures? Is it the less the interest of men to be happy—less to be wished that they may be so—less the moral duty of their governors to make them so, as far as they can, at Mogadore than at Philadelphia?

Whence is it, but from government, that contracts derive their binding force? Contracts came from government, not government from contracts. It is from the habit of enforcing contracts, and seeing them enforced, that governments are chiefly indebted for whatever disposition they have to observe them.

Sentence 2. These rights [these imprescriptible as well as natural rights,] are liberty, property, security, and resistance to oppression.

Observe the extent of these pretended rights, each of them belonging to every man, and all of them without bounds. Unbounded liberty; that is, amongst other things, the liberty of doing or not doing on every occasion whatever each man pleases:—Unbounded property; that is, the right of doing with everything around him (with every thing at least, if not with every person,) whatsoever he pleases; communicating that right to anybody, and withholding it from anybody:—Unbounded security; that is, security for such his liberty, for such his property, and for his person, against every defalcation that can be called for on any account in respect of any of them:—Unbounded resistance to oppression; that is, unbounded exercise of the faculty of guarding himself against whatever unpleasant circumstance may present itself to his imagination or his passions under that name. Nature, say some of the interpreters of the pretended law of nature—nature gave to each man a right to everything; which is, in effect, but another way of saying—nature has given no such right to anybody; for in regard to most rights, it is as true that what is every man’s right is no man’s right, as that what is every man’s business is no man’s business. Nature gave—gave to every man a right to everything:—be it so—true; and hence the necessity of human government and human laws, to give to every man his own right, without which no right whatsoever would amount to anything. Nature gave every man a right to everything before the existence of laws, and in default of laws. This nominal universality and real nonentity of right, set up provisionally by nature in default of laws, the French oracle lays hold of, and perpetuates it under the law and in spite of laws. These anarchical rights which nature had set out with, democratic art attempts to rivet down, and declares indefeasible.

Unbounded liberty—I must still say unbounded liberty;—for though the next article but one returns to the charge, and gives such a definition of liberty as seems intended to set bounds to it, yet in effect the limitation amounts to nothing; and when, as here, no warning is given of any exception in the texture of the general rule, every exception which turns up is, not a confirmation but a contradiction of the rule:—liberty, without any pre-announced or intelligible bounds; and as to the other rights, they remain unbounded to the end: rights of man composed of a system of contradictions and impossibilities.

In vain would it be said, that though no bounds are here assigned to any of these rights, yet it is to be understood as taken for granted, and tacitly admitted and assumed, that they are to have bounds; viz. such bounds as it is understood will be set them by the laws. Vain, I say, would be this apology; for the supposition would be contradictory to the express declaration of the article itself, and would defeat the very object which the whole declaration has in view. It would be self-contradictory, because these rights are, in the same breath in which their existence is declared, declared to be imprescriptible; and imprescriptible, or, as we in England should say, indeteasible, means nothing unless it exclude the interference of the laws.

It would be not only inconsistent with itself, but inconsistent with the declared and sole object of the declaration, if it did not exclude the interference of the laws. It is against the laws themselves, and the laws only, that this declaration is levelled. It is for the hands of the legislator and all legislators, and none but legislators, that the shackles it provides are intended,—it is against the apprehended encroachments of legislators that the rights in question, the liberty and property, and so forth, are intended to be made secure,—it is to such encroachments, and damages, and dangers, that whatever security it professes to give has respect. Precious security for unbounded rights against legislators, if the extent of those rights in every direction were purposely left to depend upon the will and pleasure of those very legislators!

Nonsensical or nugatory, and in both cases mischievous: such is the alternative.

So much for all these pretended indefeasible rights in the lump: their inconsistency with each other, as well as the inconsistency of them in the character of indefeasible rights with the existence of government and all peaceable society, will appear still more plainly when we examine them one by one.

1. Liberty, then, is imprescriptible—incapable [503] of being taken away—out of the power of any government ever to take away: liberty,—that is, every branch of liberty—every individual exercise of liberty; for no line is drawn—no distinction—no exception made. What these instructors as well as governors of mankind appear not to know, is, that all rights are made at the expense of liberty—all laws by which rights are created or confirmed. No right without a correspondent obligation. Liberty, as against the coercion of the law, may, it is true, be given by the simple removal of the obligation by which that coercion was applied—by the simple repeal of the coercing law. But as against the coercion applicable by individual to individual, no liberty can be given to one man but in proportion as it is taken from another. All coercive laws, therefore (that is, all laws but constitutional laws, and laws repealing or modifying coercive laws,) and in particular all laws creative of liberty, are, as far as they go, abrogative of liberty. Not here and there a law only—not this or that possible law, but almost all laws, are therefore repugnant to these natural and imprescriptible rights: consequently null and void, calling for resistance and insurrection, and so on, as before.

Laws creative of rights of property are also struck at by the same anathema. How is property given? By restraining liberty; that is, by taking it away so far as is necessary for the purpose. How is your house made yours? By debarring every one else from the liberty of entering it without your leave. But

2. Property. Property stands second on the list,—proprietary rights are in the number of the natural and imprescriptible rights of man—of the rights which a man is not indebted for to the laws, and which cannot be taken from him by the laws. Men—that is, every man (for a general expression given without exception is an universal one) has a right to property, to proprietary rights, a right which cannot be taken away from him by the laws. To proprietary rights. Good: but in relation to what subject? for as to proprietary rights—without a subject to which they are referable—without a subject in or in relation to which they can be exercised—they will hardly be of much value, they will hardly be worth taking care of, with so much solemnity. In vain would all the laws in the world have ascertained that I have a right to something. If this be all they have done for me—if there be no specific subject in relation to which my proprietary rights are established, I must either take what I want without right, or starve. As there is no such subject specified with relation to each man, or to any man (indeed how could there be?) the necessary inference (taking the passage literally) is, that every man has all manner of proprietary rights with relation to every subject of property without exception: in a word, that every man has a right to every thing. Unfortunately, in most matters of property, what is every man’s right is no man’s right; so that the effect of this part of the oracle, if observed, would be, not to establish property, but to extinguish it—to render it impossible ever to be revived: and this is one of the rights declared to be imprescriptible.

It will probably be acknowledged, that according to this construction, the clause in question is equally ruinous and absurd:—and hence the inference may be, that this was not the construction—this was not the meaning in view. But by the same rule, every possible construction which the words employed can admit of, might be proved not to have been the meaning in view: nor is this clause a whit more absurd or ruinous than all that goes before it, and a great deal of what comes after it. And, in short, if this be not the meaning of it, what is? Give it a sense—give it any sense whatever,—it is mischievous:—to save it from that imputation, there is but one course to take, which is to acknowledge it to be nonsense.

Thus much would be clear, if anything were clear in it, that according to this clause, whatever proprietary rights, whatever property a man once has, no matter how, being imprescriptible, can never be taken away from him by any law: or of what use or meaning is the clause? So that the moment it is acknowledged in relation to any article, that such article is my property, no matter how or when it became so, that moment it is acknowledged that it can never be taken away from me: therefore, for example, all laws and all judgments, whereby anything is taken away from me without my free consent—all taxes, for example, and all fines—are void, and, as such, call for resistance and insurrection, and so forth, as before.

3. Security. Security stands the third on the list of these natural and imprescriptible rights which laws did not give, and which laws are not in any degree to be suffered to take away. Under the head of security, liberty might have been included, so likewise property: since security for liberty, or the enjoyment of liberty, may be spoken of as a branch of security:—security for property, or the enjoyment of proprietary rights, as another. Security for person is the branch that seems here to have been understood:—security for each man’s person, as against all those hurtful or disagreeable impressions (exclusive of those which consist in the mere disturbance of the enjoyment of liberty,) by which a man is affected in his person; loss of life—loss of limbs—loss of the use of limbs—wounds, bruises, and the like. All laws [504] are null and void, then, which on any account or in any manner seek to expose the person of any man to any risk—which appoint capital or other corporal punishment—which expose a man to personal hazard in the service of the military power against foreign enemies, or in that of the judicial power against delinquents:—all laws which, to preserve the country from pestilence, authorize the immediate execution of a suspected person, in the event of his transgressing certain bounds.

4. Resistance to oppression. Fourth and last in the list of natural and imprescriptible rights, resistance to oppression—meaning, I suppose, the right to resist oppression. What is oppression? Power misapplied to the prejudice of some individual. What is it that a man has in view when he speaks of oppression? Some exertion of power which he looks upon as misapplied to the prejudice of some individual—to the producing on the part of such individual some suffering, to which (whether as forbidden by the laws or otherwise) we conceive he ought not to have been subjected. But against everything that can come under the name of oppression, provision has been already made, in the manner we have seen, by the recognition of the three preceding rights; since no oppression can fall upon a man which is not an infringement of his rights in relation to liberty, rights in relation to property, or rights in relation to security, as above described. Where, then, is the difference?—to what purpose this fourth clause after the three first? To this purpose: the mischief they seek to prevent, the rights they seek to establish, are the same; the difference lies in the nature of the remedy endeavoured to be applied. To prevent the mischief in question, the endeavour of the three former clauses is, to tie the hand of the legislator and his subordinates, by the fear of nullity, and the remote apprehension of general resistance and insurrection. The aim of this fourth clause is to raise the hand of the individual concerned to prevent the apprehended infraction of his rights at the moment when he looks upon it as about to take place.

Whenever you are about to be oppressed, you have a right to resist oppression: whenever you conceive yourself to be oppressed, conceive yourself to have a right to make resistance, and act accordingly. In proportion as a law of any kind—any act of power, supreme or subordinate, legislative, administrative, or judicial, is unpleasant to a man, especially if, in consideration of such its unpleasantness, his opinion is, that such act of power ought not to have been exercised, he of course looks upon it as oppression: as often as anything of this sort happens to a man—as often as anything happens to a man to inflame his passions,—this article, for fear his passions should not be sufficiently inflamed of themselves, sets itself to work to blow the flame, and urges him to resistance. Submit not to any decree or other act of power, of the justice of which you are not yourself perfectly convinced. If a constable call upon you to serve in the militia, shoot the constable and not the enemy;—if the commander of a press-gang trouble you, push him into the sea—if a bailiff, throw him out of the window. If a judge sentence you to be imprisoned or put to death, have a dagger ready, and take a stroke first at the judge.

Article III.: The principle of every sovereignty [government] resides essentially in the nation. No body of men—no single individual—can exercise any authority which does not expressly issue from thence.↩