William H. Hutt, The Theory of Idle Resources (1939)

|

|

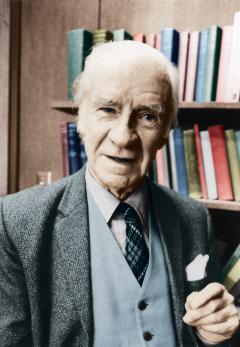

| William H. Hutt (1899-1988) |

Source

William H. Hutt, The Theory of Idle Resources (London : Jonathan Cape, 1939).

Second edition by Mises Institute: William H. Hutt, The Theory of Idle Resources. Introduction by Hunter Lewis (Auburn, AL: Ludwig von Mises Institute, 2011. Copyright © 2011 by the Ludwig von Mises Institute and published under the Creative Commons Attribution License 3.0.

- available in PDF and ePuB formats online.

HTML version edited and formatted by David M. Hart.

CONTENTS ↩

- Introduction

- Preface

- I. Definition of Idleness

- II. Valueless Resources

- III. Pseudo-Idleness

- IV. Pseudo-Idleness in Labor

- V. Preferred Idleness

- VI. Irrational Preferred Idleness

- VII. Participating Idleness

- VIII. Participating Idleness in Labor

- IX. Enforced Idleness

- X. Withheld Capacity

- XI. Strike Idleness and Aggressive Idleness

- XII. Conclusion

- Index

INTRODUCTION↩

GENIUS DOES NOT always announce itself. This was especially true of William H. Hutt. There was nothing about him to attract attention. He was born in London of working class parents, earned a bachelor’s degree in economics from The London School of Economics in 1924, worked for a London publishing firm, migrated to South Africa where he lectured obscurely in economics, before eventually retiring and moving to the U.S. in 1965. He was slight in frame and modest in manner, never pushing, always delighted to see the triumphs of others. He identified himself as a classical economist, not a member of any contemporary group or movement—how easy indeed to overlook him, but what a mistake to do so.

Hutt’s mind was made for logic. It could see a logical problem from every side, draw every distinction and nuance, then penetrate right to the bottom of it. No fallacy was safe from him and, without being the least combative, he never flinched from telling the unvarnished truth.

The history of modern economics is full of destructive fallacies, beginning with the mercantilists, continuing through Karl Marx, and culminating with John Maynard Keynes. These false ideas have impoverished billions of people and caused no end of needless suffering. When Keynes published his magnum opus, The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money in 1936, a potpourri of fallacies supported by obscurity, shifting definitions, and other rhetorical tricks, many economists criticized it privately, but very few did so publicly. Why? Because Keynes was an intimidating figure, the best known economist in the world, a master publicist and polemicist, the editor of The Economic Journal, an essential venue for English speaking economists.

In the Preface to The Theory of Idle Resources, completed a year after Keynes’s General Theory appeared, and published two years later in 1939, Hutt says forthrightly: “I have been wisely advised not to touch on any of the major controversies which his contribution [Keynes’s General Theory] has aroused.”1 But, then, with laser-like logic, he proceeds to demolish some of the most important intellectual props for Keynes’s Theory. Moreover, he does so, as he says, “as far as possible, in a non-technical way” so that “the reader who is unacquainted with the economic textbooks may follow my reasoning from point to point and himself decide on it’s validity.”2

Keynes’s argument may be simplified as follows. Full employment should be our goal. The market system will not get us there; it requires government help as well as guidance. This means, in practice, that government will continually print money, in order to reduce interest rates, ultimately to zero3, and also borrow and spend as needed. Booms are good, even economic bubbles are acceptable. Recession and bust must be avoided at all cost. As Keynes wrote: “The right remedy for the trade cycle is not to be found in abolishing booms and thus keeping us permanently in a semi-slump; but in abolishing slumps and thus keeping us permanently in a quasi-boom.”4

In a variety of books and articles, Hutt pointed out the absurdity of this. One cannot create wealth simply by printing more money or by borrowing and spending funds which can never be repaid. Moreover, the real source of unemployment is some disturbance in the price and profit system. Government cannot possibly help matters by intervening in ways which further distort and disturb that system.

In his Theory of Idle Resources, Hutt deconstructs even the initial premise of Keynes’s thinking, that we should want a permanent condition of full employment. Not only is full employment not definable; it is not even desirable. A moment’s thought will show this to be true. To grow, an economy must change. To change, assets and workers must be shifted from where they are less needed (less productive) to where they are more needed (more productive). These shifts will inevitably produce temporary unemployment. If there had never been unemployment, and thus no economic change, we would all still be living in caves, and there would be far fewer of us, because hunting and gathering would only support a small fraction of the present population.

This insight is not original to Hutt. The economic writer Henry Hazlitt, a friend of Hutt’s, found similar observations in a paper written by John Stuart Mill during 1829–30 when he was age twenty-four, and collected in his Essays on Some Unsettled Questions of Political Economy. Mill’s paper completely refutes Keynes’s false contention that “classical” economists simply assumed that there would always be “full employment.” But Hutt takes the examination of unemployment much further than the pioneering Mill. Indeed, he does not just examine unemployment. He examines unemployment as part of the larger phenomenon of unused or idle productive resources, including land, plant, equipment, and money as well as workers.

Hutt’s careful reasoning demonstrates, through a variety of illustration, that we cannot just lump together (and falsely quantify) all the complexities of human choice and action working within a closely coordinated price and profit system. What looks like non-productive idleness may actually be very productive, indeed essential to the smooth working of the system. Is it more productive for a highly trained but unemployed engineer to bag groceries for pay or to invest time without pay in looking for an engineering job? If he or she took the grocery bagging job, Keynes would presumably be satisfied; we would be closer to full employment. But the economy would clearly not be more productive, which it must be to create new jobs. We should also keep in mind that an employment agency employee job searching for the engineer would be considered gainfully “employed,” while the engineer doing the same work would still be “unemployed.”

This brings us to Hutt’s crucial concept of sub-optimal employment, not fully worked out in this book, but a crucial contribution to economic thought. Government intervention to stimulate the economy and increase employment not only reduces employment over the long run. It also creates an enormous amount of “sub-optimal employment,” which means that it leaves people unable to find the work for which they are best suited.

A simple example of this may be drawn from the U.S. housing bubble that burst in 2007–2008. For the period 2002–2008, out-of-control Federal Reserve money printing and a host of other government policies and programs blew up the bubble. Millions of people not especially suited for construction were pulled into this sector and put to work building homes that, in the end, no one wanted. When the bubble burst, even the most highly trained construction workers suddenly found themselves unable to get any construction work at all.

The underlying problem here is that, contra Keynes, we do not want employment for its own sake. It is a means, not an end. What we want is a productive economy, and government stimulus gives us, as Henry Hazlitt has said, “unbalanced production, misdirected production, production of the wrong things..., [all of which lead inexorably] to unemployment and mal-employment.”5

In speaking of optimal versus sub-optimal employment, Hutt, the master logician, was drawing a logical distinction between quality and quantity. This is an inconvenient distinction for Keynesian-derived macro-economists; there is no way to fit quality into their equations. But in economics, as in life as a whole, quality is even more important than quantity.

This is especially true in investment. Keynes said that any investment is better than no investment.6 Indeed, in the absence of his indefinable state of full employment, he thought that any spending, whether consumption or investment, was better than no spending. This is why government must keep printing money: the resulting reduction in interest rates should encourage more and more investment and spending.

There are many reasons why this is nonsense, but it suffices to recall that interest rates are a price. Like currencies, they are “big prices,” which affect the entire economy. The chief purpose of prices in a market system is to send signals about what consumers want and about the relative availability or scarcity of resources. When government intervenes to reduce interest rates, it therefore disables the price signaling system, which in turn leads investors to make decisions which, in the long run, turn out to be bad decisions, like the overdoing of technology in the 1990s bubble or the overdoing of housing in the 2000s, bad decisions which eventually lead, not to employment, but to massive unemployment.

Hutt’s concept of sub-optimal employment applies to productive assets as well as people. Contra Keynes, it is generally better for productive resources to remain idle for a time than to be misused. Savers, whether in cash or gold, are not “hoarding,” as Keynes charged, when they hold their investment capital out of an economic bubble. On the contrary, they are providing an immense economic service by ensuring that there will still be capital to invest after the bubble has burst. As Hutt says, the “availability” of a resource, whether plant, equipment, workers, or money can in itself represent a service. Another reason that investing in gold is not hoarding, again contrary to Keynes, is that the buyer and seller of the gold simply exchange cash for precious metal, which is to say, one form of money for another. No cash is actually withdrawn from the economy.

Hutt was an economist’s economist. Unlike Keynes, he did not aspire to the world of politics or big business. He counted himself among “those ... who are not selling policies in return for power,”7 and took pleasure in correcting logical errors, large or small, wherever he found them. He is best known for re-establishing Say’s Law after Keynes’s distortion and attempted demolition of it, but much of his best work is on unemployment, and much of that is in The Theory of Idle Resources.

Despite being an economist’s economist, Hutt appreciates how the world actually works. For example, Keynes spoke of “the proceeds which entrepreneurs expect to receive from the employment of N [fill in the number] men.”8 Entrepreneurs of course do not think this way. They think of products, prices, and costs, of which employees are one, all summed up in the computation of profit. The word profit is one that Keynes avoids wherever possible in his General Theory, though in earlier writings he acknowledged its central role in driving the economy. Hutt rightly looks askance at this.

Hutt further notes that “We cannot add together, say, the number of hours of utilization of a locomotive, of the track, and of the signals. Similarly, we cannot aggregate the employment of the engine driver, the fireman, the guard, and the signalman.”9 Keynes tries to circumvent the difficulty of aggregating labor in a quantifiable series by regarding “individuals as contributing to the supply of labor in proportion to their remuneration.”10 Hutt retorts that: “Such a definition of employment must lead to the most absurd results. Thus, if the workers in a trade can organize and drive 10 percent of their number into inferior occupations, reduce by 10 percent the amount of labor supplied, and in so doing increase the aggregate earnings of that trade by, say, 20 percent, then the proportion of all employment enjoyed by them and the proportion of the total labor supplied by them must be regarded as increased!”11

As the above quote suggests, Hutt was not a fan of labor unions. He was, so far as this writer knows, the very first economist to explain why higher wages earned by unions actually come out of the pockets of other workers, not out of employers’ profits, a point that is now well established but still little understood. This is true, in simple terms, because high wages reduce employment in unionized sectors, thereby increase labor supply in other sectors, which increased supply reduces non-unionized labor rates. In addition, workers are also consumers and may have to pay more for unionized sector goods. As a general rule, Hutt noted, “the poorest must ... suffer most as consumers.”12

Although a foe of unions, Hutt regarded himself as a populist, in the sense of wanting what is best for ordinary and especially poor people. He even called himself, somewhat startlingly, an “equalitarian,” a word that is usually associated with socialism. So, how indeed, could Hutt be both a free market advocate and a self-described equalitarian? He could be both because, in his view, free markets, without aiming for equal outcomes, produce both more equal opportunity and more equal outcomes than any other system.

Hutt explains: “The clue to the understanding of the chief economic and sociological problems of today can be found, in my opinion, in a recognition of the struggle which is in progress against the disrupting equalitarian effects of competitive capitalism. Competition and capitalism are hated today because of their tendency to destroy poverty and privilege more rapidly than custom and the expectations established by protections can allow. We accordingly find private interests combining to curb this process and calling upon the State to step in to do the same; and unless the resistance is expressed through monetary policy, the curbing takes the form of restrictions on production. Hence there arises a clash between what I have called the ‘productive scheme’ and the ‘distributive scheme’; and wasteful idleness, both in labor and in physical things, appears to be due to the consequent restraint of productive power—a restraint imposed immediately [by government] in defense of private interests, but [sugar coated with legal minimum wages and unemployment insurance that ultimately just lead to lower wages and more unemployment].”13

Are some of the poor willing to accept government welfare rather than try to improve their prospects? If so, says Hutt, we should not necessarily regard them as either lazy or irrational. They may just realize that the crony capitalist system which presently prevails is completely stacked against them.14

If we really want to alleviate unemployment and poverty, Hutt continues, we must do something about this crony capitalism, with its privileged government-business and government-labor partnership monopolies, and it’s supporting out-of-control government and fiscal monetary policies. All such monopoly systems create “contrived scarcity,” “enforced waste,” and other completely irrational outcomes. Unemployment and poverty are simply “indications of its presence,”15 of the “triumph [of] ... private interest ... over social interest.”16

Hutt also correctly predicted that this problem would get worse before it got better. In an especially acute passage, he explained why the medical system would increasingly be drawn into the monopolistic crony capitalist framework.17

As the reader will shortly see, Hutt’s work in The Theory of Idle Resources is truly timeless, and being timeless, is just as fresh and relevant today as when first published in 1939.

Hunter Lewis

Endnotes

1 William H. Hutt, The Theory of Idle Resources, p. xiv.

2 Ibid., p. XV.

3 John Maynard Keynes, The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money (Amherst, N.Y.: Prometheus Books, 1997), p. 220.

4 Ibid., p. 322.

5 Henry Hazlitt, The Inflation Crisis (New Rochelle, N.Y.: Arlington House, 1978), p. 79.

6 Keynes, The General Theory, p. 327.

7 Hutt, Theory of Idle Resources, p. 92.

8 Keynes, The General Theory, p. 25.

9 Hutt, Theory of Idle Resources, p. 6.

10 Keynes, The General Theory, p. 42.

11 Hutt, Theory of Idle Resources, p. 6.

12 Ibid., p. 64.

13 Ibid., p. XVI.

14 Ibid., p. 44.

15 Ibid., p. 74.

16 Ibid., p. 106.

17 Ibid., pp. 61–62.

PREFACE↩

IT IS CURIOUS that so important a subject as unemployment should have brought forth no treatise devoted to theoretical analysis of the condition. There have been many books purporting to deal with unemployment of labor, but these have either been descriptive works, like Sir William Beveridge’s famous Unemployment, a Problem of Industry, or theoretical studies of demand, like Professor Pigou’s Theory of Unemployment, or Mr. J.M. Keynes’s General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money. This essay tries to fill the gap. The necessity became clear to me in the course of an attempt to envisage the institutions required for an equalitarian or competitive society. Having found no satisfactory analysis of conceptions which it seemed essential to employ, I was forced to provide my own textbook treatment.

My reason for using the term “idleness” instead of “unemployment” is that the latter term has, by tradition, become associated with the idleness of labor, and any satisfactory study must obviously be concerned with “idleness” in all resources. And having made “idleness” my topic, I have adhered strictly to it, and do not claim to have made any direct contribution to monetary or trade-cycle theory. I was at first tempted to venture into this province, but after many wanderings I could not feel satisfied that I had found my bearings with sufficient accuracy to try to guide others. Nevertheless, I have indicated a region which ought to be explored with the instruments that I have provided. My several critical references to the work of Mr. J.M. Keynes are due to the fact that his General Theory happens to be in the thoughts of all economists today. I have been wisely advised not to touch on any of the major controversies which his contribution has aroused. Certainly I have not avoided controversial topics. But it is my hope that all sides in the current debate on the monetary causes of idleness will find my analysis realistic and useful, and that it will be of some help to them in searching for the origin of their differences.

Although I am offering a “theoretical” contribution, a mere contribution to conceptual clarity, my inspiration has throughout been the closest interest in practical affairs. The objective problem of inventing institutions which could foster security and equality has been the motive which has guided my study at each stage. I earnestly believe that policy-makers could find enlightenment in it. But I am sufficient of a realist to know that the chances of its exercising any influence on policy are small. The politicians in unemployment-cursed countries are too concerned with their immediate popularity to give much consideration to a dispassionate analysis such as I have attempted. For if they do glance at its pages they will soon see that its implications cannot be easily reconciled with ideologies to which they feel they must of necessity pander.

However, to encourage the policy-makers, I have endeavored to treat the subject, as far as possible, in a non-technical way. Any patient and intelligent layman should be able to understand my argument. I have reduced the current jargon and conventional technical conceptions to a minimum, and where I have employed them, their meaning should be sufficiently evident to the careful reader. In this way, my treatment differs from all the recent theoretical studies of demand which intend to deal with the causes of idleness. My suggestions need not be taken on authority. The reader who is unacquainted with the economic textbooks may follow my reasoning from point to point and himself decide on its validity. I welcome the layman not, as Keynes does in his General Theory, as an “eavesdropper,” but as one who can and should consider my thesis. I do not claim, however, to have produced a “popular” work. Where I have thought it helpful, I have not shrunk from exploiting the most abstract conceptions. And I have incidentally introduced a new jargon of my own. Hence, the reader who is inexpert in economics must persevere and have constant recourse to the summaries which may guide him through a labyrinth of notions.

It has not been my task in this essay to recommend specific reforms. Certainly I have hinted at desirable changes, but my aim here has been to determine causes. If would-be reformers feel bewildered by the practical difficulties which my analysis of causes discloses, they may be helped by my own attempt to face the basic obstacles in my Economists and the Public, chapter XXI, entitled “Vested Interests and the Distributive scheme. “The clue to the understanding of the chief economic and sociological problems of today can be found, in my opinion, in a recognition of the struggle which is in progress against the disrupting equalitarian effects of competitive capitalism. Competition and capitalism are hated today because of their tendency to destroy poverty and privilege more rapidly than custom and the expectations established by protections can allow. We accordingly find private interests combining to curb this process and calling upon the State to step in to do the same; and unless the resistance is expressed through monetary policy, the curbing takes the form of restrictions on production. Hence there arises a clash between what I have called the “productive scheme” and the “distributive scheme”; and wasteful idleness, both in labor and in physical things, appears to be due to the consequent restraint of productive power—a restraint imposed immediately in defense of private interests, but ultimately appearing to be reasonable and just because it defends an existing and customary distribution.

The original typescript of this book was completed more than two years before the present version was sent to the publishers. Several copies were put into circulation and I received advice and encouragement from so many friends that it is impossible to make adequate acknowledgments. But I have a special debt of gratitude to the following who at different times read the whole of the typescript as it then stood and whose comments led to substantial changes of terminology, exposition or content: Professor Lionel Robbins, Mr. Frank Paish, Professor Arnold Plant, Professor F. A. Hayek and Mr. H. A. Shannon.

W.H.Hutt

University of Cape Town

1939

CHAPTER I. DEFINITION OF IDLENESS↩

(1) Similar causes exist for idleness in labor, equipment and all other resources↩

THE OBJECT of this essay is to remove certain common confusions concerning the significance of idle productive resources. We shall endeavor to do so by the introduction of a new set of concepts and definitions. The problems at issue are generally referred to as those of “surplus capacity” in the case of equipment and “unemployment” in the case of labor. Similar causes of the different phenomena of idleness are, we shall argue, active in both cases.1 Indeed, so true and important does this contention seem to be, that practically all recent attempts to analyze realistically the nature and causes of unemployment of labor have, we believe, gone seriously astray through failure to recognize it; or at any rate they appear to have been led into error through the necessary crudeness of attempts to deal with attributes common to all types of productive resources by considering their manifestation in one type only.2 In the case of purely natural resources, no “problems” of idleness are usually regarded as arising, although the more careful economists have recognized that “produced” and “non-produced” resources are governed by the same laws of utilization. We shall, then, deal with the various conceptions of idleness of resources in general.

(2) Idleness has one appearance but exists in several senses↩

We can define idleness in several ways. That is, we can use the term in various senses. Different causes produce idleness of different types and significance. Our main thesis is that confusion arises from a failure to recognize the consequences of this obvious truth. When there is a plurality of conditions each of which in its pure state has a similar appearance, and each of which has its own cause, what appears to be a simple quality may in fact be a mixture of quite separate attributes. Unemployment or idleness may exist in several different senses whilst all the states, in their “pure” form, may look alike.3 How serious the confusion can be will be realized when it is remembered that what constitutes idleness from one point of view may be utilization from another. Mr. Keynes has attempted (and his interpreters have followed in his footsteps) to simplify and give unity to the conception of unemployment of labor by using a definition of “disutility” which lumps together many quite different things.4 He defines “disutility” as covering “every kind of reason which might lead a man, or a body of men, to withhold their labor rather than accept a wage which had to them a utility below a certain minimum.”5 Now this definition draws a veil over many of the issues which we have to face. We shall show that the significance of withheld labor can be classed into at least six vitally distinct categories, the nature of the unemployment being radically different in each case.

(3) The necessity for definition↩

The analysis of idleness calls therefore for the isolation and definition of the various states which that broad term covers. But new definitions are irritating things, and the mere process of multiplying terms may appear to be both pretentious and barren. If we determine to have a new definition, said Malthus, “in every case where the old one is not quite complete, the chances are that we shall subject the science to all the serious disadvantages of a frequent change of terms without finally accomplishing our object.”6 Nevertheless, we feel confident that the terms here proposed do qualify under Malthus’s common-sense exception, namely, that “a change would be beneficial and decidedly contribute to the advancement of the science.”7 And we have tried to adhere to “the fundamental principle” which Professor Cassel has laid down. “The introduction of definitions,” he says, “should be based on a preliminary scientific analysis of economic reality. When this analysis has shown that a certain economic concept is of essential importance and can be distinguished with sufficient exactness, the time has come for giving a name to this concept, that is to say, for introducing a new definition”8

(4) Popular conceptions of unemployment of labor recognized by custom and law do not help us to define “idleness”↩

But to analyze “economic reality” does not mean that we should try to make our conceptions harmonize with those based on popular usage, when that usage is confused. Even if popular but confused conceptions have been given recognition by custom or law we can seldom usefully adopt them. Thus, Professor Pigou’s attempt to handle unemployment by defining “desire to be employed” as “desire to be employed at current rates of wages,”9 and by regarding unemployment as the absence of employment at that rate, is an attempt which, in spite of its intended realism, dodges instead of encounters the difficulties of the subject. It is true that his definition corresponds roughly to an official British view of “suitable employment,” the absence of which has been held to constitute unemployment in the legal sense. But if it is made the basis of analysis, all the really fundamental aspects of idleness are passed over. It will be seen, for instance, that under the definitions which we are about to put forward, if capitalist interlopers (e.g., “the bad employers”) are offering an unemployed worker £3 10s. od. a week for a job when the trade-union rate (the “current rate”) is £4, and he refuses to accept it out of loyalty to the union’s wage policy, it is, in the first place, clearly a case of “withheld capacity,” and also, in the second place, a case of “participating idleness” or one of “preferred idleness.” To ignore these aspects is, we believe, to overlook all the crucial issues.

(5) The categories isolated here are based on logical rather than empirical criteria↩

We shall here distinguish between the following types of idleness: (a) idleness of valueless resources; (b) pseudo-idleness; (c) preferred idleness; (d) participating idleness; (e) enforced idleness; (f) withheld capacity; (g) strike idleness; (h) aggressive idleness. A state of utilization which has been described as “disguised unemployment” in the case of labor, we shall recognize as (i) “diverted resources.” We believe that every kind of unemployment of resources which has been discussed in the wide literature dealing with unemployment of labor, and in the relatively few contributions which treat of the idleness of other resources, can be included under one or more of these headings. Other terms for the same conditions have been employed, but they have often covered, in a quite unjustifiable way, absolutely different things. Thus, books on the unemployment of labor use the adjectives: “seasonal,” “cyclical,” “slump,” “casual,” “frictional,” “technological” and so forth. But these descriptions are based on empirical rather than logical criteria. They are not the “precise conceptions” demanded by Sidgwick’s standards for definitions and terms.10 They will all be found, on analysis, to involve factors which must be expressed through the causes set forth above. It will be shown that, although empirical definitions undoubtedly have their appropriateness in particular studies, until they are regarded from the angle demanded by our logical scheme, it is difficult for their true significance to be plain. For in each case one of the factors we have indicated will be seen to be the proximate cause. We mean by this that the removal of the one factor would lead to the utilization of the resource,or else to the continued idleness of the resource in some other sense only and from some other cause. In certain cases, more than one of these causes (with its corresponding type of idleness) may be present whilst the removal of any one would mean the cessation of the others. In other cases the causes (and the appropriate types of idleness) are independent.11

(6) Rational policies must recognize our categories↩

It must be admitted that knowledge of the category into which any type of idleness falls may not always be the most important knowledge, but it is essential knowledge in every case. Thus, for some discussions, to say that certain resources are idle because they fall into the “valueless resources” category will not be helpful if we stop there. States men and reformers will want to know why they are valueless. And discussion of the implications of this condition will therefore bring under examination the determinants of the margin between valuable and valueless resources. Nevertheless, we conceive it to be one of the supreme tasks in the present state of popular (and even academic) controversy to emphasize the consequences of the greater part of deplorable idleness not falling into this particular category12 We shall demonstrate (a) that idleness can be analyzed into logically separate classes, the relation of each of which to the wider conception of “waste” has not been sufficiently discussed; and (b) that whatever forces lying deeper in the social organism may be held to be responsible for idleness, in the absence of one or more of the causes that we have defined, the condition would not exist.

(7) There can be no measure of utilization or idleness↩

We shall conceive of “unemployment” or “idleness,” in all the different senses that we propose to distinguish, as a condition or quality. It cannot be thought of quantitatively. In so far as different types of resources can be defined in terms of quantity, it is possible to talk of the amount of resources which are in the condition of being utilized or employed. We can also realistically refer to the proportion of total time, or the proportion of the conventional working days in a year (or some other time standard) during which the services of particular resources (e.g., looms or weavers) are being utilized. But we cannot talk of the amount of employment in any other way. We cannot add together, say, the number of hours of utilization of a locomotive, of the track, and of the signals. Similarly, we cannot aggregate the employment of the engine driver, the fireman, the guard, and the signalman.

(8) Mr. Keynes’s attempt to measure “employment” has absurd implications↩

But Mr. Keynes does try to conceive of employment of labor as a measurable condition. He discusses the sum of all the employment involved in all the different occupations of labor, expressed in terms of “men.” The only major difficulty that he appears to recognize is that which arises through differences of remuneration; and he thinks that it is sufficient for his purpose to get over the difficulty by “taking an hour’s employment of ordinary labor as our unit and weighting an hour’s employment of special labor in proportion to its remuneration.”13 In other words, he regards “individuals as contributing to the supply of labor in proportion to their remuneration.”14 Such a definition of employment must lead to the most absurd results. Thus, if the workers in a trade can organize and drive 10 percent of their number into inferior occupations, reduce by 10 percent the amount of labor supplied, and in so doing increase the aggregate earnings of that trade by, say, 20 percent, then the proportion of all employment enjoyed by them and the proportion of the total labor supplied by them must be regarded as increased! Apparently this is so in spite of “the level of employment,” N, being expressed in terms of “men.” Curiously enough, Mr. Keynes recognizes that “the community’s output of goods and services is a nonhomogeneous complex which cannot be measured ...”;15 he sees that there is no solution of the “problem of comparing one real output with another”;16 and he is clearly aware of the connected difficulty arising out of the vagueness of the “price level concept.”17 But by substituting the notion of “employment” he has not escaped the impossibility of defining aggregate output. For, if different sorts of “employment” are regarded as having values, are we not really thinking of them as the output of services? What else can be valued? And one can no more measure “employment” in the sense of the output of productive services in general than one can the output of consumers’ goods and consumers’ services in general to which they lead. Yet the whole of Mr. Keynes’s general theory, developed “with a princely profusion of reasoning,”18 is erected on an “Aggregate Supply Function” which assumes that “employment” so conceived can be measured. The function (expressed as Z =φN, N being a level of employment induced by an expectation of a return, Z) hides what may possibly be a serious fallacy in the apparent definiteness of an equation. In avoiding the use of the meaningless term “output,” he has not avoided the concept itself. For N is nothing but output at an early stage of production. His weighting leaves no meaning in the unit “men” at all. We cannot, as he assumes, “aggregate the N’s in a way which we cannot aggregate the O’s”19 (O being an output). ΣN is no more a numerical quantity than ΣO. We shall here assume that all such attempts to devise a logically tenable quantitative concept of utilization or employment are misconceived. This assumption will in no way hinder the sort of analysis of the problem which we conceive to be realistic and useful.

(9) Orthodox theory does not, as has been alleged, assume “full employment”↩

Mr. Keynes also alleges that classical and orthodox theory “is best regarded as a theory of distribution in conditions of full employment”20 (apparently because some writers have assumed “full employment” as a methodological device in abstract analysis). His assertion has subsequently been emphasized and repeated by several writers who have been impressed by this startling revelation. And the “man-in-the-street,” who is also anxious to believe that orthodox economists have been astonishingly stupid, has been pleased to find his predilections confirmed. We believe, however, that the types of idleness analyzed in the pages which follow are all of a kind which are implicit—if not expressed in sufficiently clear terms—in orthodox teaching. This essay is felt to be original only in the sense that, through more careful definition, it seeks to clarify what is already known and understood. It is pure orthodoxy, as we understand that term. But it nowhere assumes the absence of the conditions it discusses. Mr. Keynes says that since Malthus there has been a “lack of correspondence between the results of (the professional economists’) theory and the facts of observation.”21 Under our own interpretation of their writings that has not been so. And the present discussion obviously recognizes the continuous and necessary existence in society of idle resources in many different senses. It may be that the classical economists overlooked many important aspects of demand in a dynamic economy. But they were realists, and their discussions imply an awareness of aspects of utilization to which their modern critics appear to be blind. Certainly the important issues here dealt with have not been faced in recent controversies.

(10) “Full employment” has no meaning as an absolute condition↩

As a matter of fact, it will be an implication of our subsequent analysis that the notion of “full employment” as an absolute condition can have no meaning. Given some basic ideal, e.g., consumers’ sovereignty, any particular resource may be said to be “under-employed” or “idling” when that ideal would be better served by the transfer of resources from other uses to cooperate with it. It would be “fully employed” in that sense if there would be no advantage in attracting other resources to cooperate with it. But it might then be working very slowly (as compared, say, to its former working). Even if continuously employed, the resources would appear to be “idling”; and yet they would be fully employed in the only rational connotation we can suggest for “full,” i.e., as a synonym for “optimum.”22 We can conceive of “fuller” employment but not “full” in the sense of “complete.” The term “full employment” might also be used in an historical or a comparative sense, to mean the degree of utilization originally expected, or achieved at a former period, or realized in similar resources elsewhere. But it is clear that none of those writers who use the term have such comparisons in mind.

(11) “Idling,” meaning “under-employment,” is a parallel conception to “idleness”↩

The conception of “idling” is allied to that of “idleness.” The former is partial, the latter is absolute. In each of the senses of “idleness” distinguished in paragraph 5, there is a parallel conception of “idling? It means “under-employment.” Thus, many productive instruments may be used intensively or extensively. A machine may work at various speeds, for instance. It may be used, say, in the production of one hundred articles a day either by being operated for the whole of the conventional day of eight hours, or by being operated at twice that speed, producing the same output in four hours and standing idle for the other four hours. From some points of view, the position is identical in these two cases. But in this exposition we shall concentrate on the condition of “idleness.” All that can be said about its significance applies with equal relevance to “idling.” And “idleness” is a distinguishable, indisputable and absolute attribute common to many different states.

1 But to recognize this truth is to lay ourselves open to the ever-recurring jibe about a philosophy which tolerates a market in which human life is bought and sold!

2 This particular source of possible confusion is most marked in the work of Mr. Keynes and his interpreters. Mr. Keynes’s analysis is made to depend upon an aggregate demand function in which demand means “the proceeds which entrepreneurs expect to receive from the employment of N men” (J.M. Keynes, General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money [New York: Harcourt Brace, 1935], p. 25). For completeness, he needs further functions in which demand means the proceeds which entrepreneurs expect to get from the employment of so many units of equipment, or other resources.

3 E.g., in the case of a machine, its wheels may not be turning; but the significance of that fact may be any one of many things.

4 In Mr. R. R Harrod’s treatment the term “disutility” is at first used in an unobjectionable way, that is, when it is used to explain output (other than leisure) under Crusoe conditions. But when he jumps from this to the notion of “inducement to work” which embodies the parallel force in society (The Trade Cycle [London: Oxford University Press, 1936], p. 10), all our objections hold.

5 Keynes, General Theory, p. 6.

6 T. R. Malthus, Definitions in Political Economy (London: John Murray, 1836), p. 6.

7 Ibid., p. 5.

8 G. Cassel, Economics as a Quantitative Science, p. 7. See Appendix to this chapter on “Definitions.”

9 A. C. Pigou, Theory of Unemployment (London: Macmillan, 1933), p. 4.

10 See Appendix to this chapter.

11 Professor Pigou’s discussion of the causation of unemployment (Theory of Unemployment, part 1, chap, vi) seems to overlook what we here regard as fundamental because he apparently conceives of a plurality of causes of a homogeneous condition which can be called “unemployment.”

12 The only reference to this basic truth that we have noticed in economic literature is in a recent article by R. F. Kahn. He says, concerning the unrealistic assumption of “full employment” in Professor Pigou’s Economics of Welfare: “That the existence of uncultivated land does not invalidate the methods and conclusions of the Economics of Welfare is sufficiently obvious. That the existence of unemployed labor upsets all these arguments is equally obvious. But in what way labor differs from land is not completely apparent.” But Dr. Kahn says that this “is a matter for separate discussion” (Economic Journal [March 1935]: 1).

13 Keynes, General Theory, p. 41.

14 Ibid., p. 42.

15 Ibid., p. 38.

16 Ibid., p. 39. Mr. Keynes’s disciples have not all followed him here. Thus, Mr. R. F. Harrod talks of “the level of output as a whole,” and even of “the equilibrium level of output of the community as a whole” (The Trade Cycle, pp. 13 and 30).

17 Mr. Keynes’s qualifies his position in an obscure way when he says that these difficulties “are ‘purely theoretical’ in the sense that they never perplex, or indeed enter in any way into, business decisions and have no relevance to the causal sequence of economic events, which are clear-cut and determinate in spite of the quantitative indeterminacy of these concepts” (General Theory, p. 39).

18 Harrod, The Trade Cycle, p. 120.

19 Keynes, General Theory, p. 45.

20 Ibid., p. 16.

21 Ibid., p. 33.

22 The conception of “full employment” in general is that of a “wasteless economy.” It excludes the possibility of “diverted resources” as well as all forms of non-productive idleness. For the meaning of “diverted resources” see chap. IX, paras. 3 and 4.

APPENDIX TO CHAPTER I. ON DEFINITIONS↩

THIS ESSAY might be described as a study in definition. Now there have always been those who were impatient of the process of meticulous definition. Richard Jones, Auguste Comte and Thorold Rogers as well as Malthus are mentioned by J.N. Keynes as having held that concentration on definition is pedantic and useless. “Political economy is said to have strangled itself with definitions.”23 Some explanation or defense of our method of basing an analysis of idleness upon careful definition may therefore be called for. Of course, this essay is itself an obvious defense of the method, but the pronouncements of the logicians of economic science may also be relied upon. J.N. Keynes himself has not agreed with the writers he quotes. He says, “There is nothing arbitrary or unessential in analyzing the precise content of a notion in the various connections in which it is involved.”24 Cairnes, indeed, seemed to envisage the necessity for constant redefinition. “Students of the social sciences,” he said, “must be prepared for the necessity of constantly modifying their classifications and, by consequence, their definitions....”25 And in endeavoring “to make our conceptions as precise as possible,”26 we feel that we have been able to illustrate, in an important field, Sidgwick’s observations that “reflective contemplation is naturally stimulated by the effort to define”27 and that as much if not more importance attaches to the process of defining as to the resulting definition itself.

We have tried also, in the analysis which follows, to avoid the “formal definitions” of which Cannan disapproved, in the sense in which he disapproved of them; for we have taken heed of his other warning and endeavored to avoid “the formation of an economic language understood only by specialists.”28 Such new terms as we have introduced should be immediately comprehensible by the layman. The term “participating idleness” gave trouble, but Cannan would surely have approved of it. And, further, an attempt has been made to adhere to the rule that Cairnes quoted from J. S. Mill, namely, that in the nomenclature of definitions “the aids of derivation and analogy” should be “employed to keep alive a consciousness of all that is signified by them.”29 This applies, we believe, even to our original but seemingly highly important conception of “participating idleness” as well as to the vaguely recognized conceptions that we have termed “pseudo-idleness” and “aggressive idleness.” But in choosing terms for our definitions, we have not been able to make use of Malthus’s suggestion that, in introducing distinctions which cannot be described by “terms which are of daily occurrence,” the next best authority is that of the “most celebrated writers in the science.”30 For, strange as it may seem, our “celebrated writers” have never specifically analyzed idleness in the very simple but apparently basic way that is here attempted. Hence it has been quite impossible to avoid this attempt to burden economic science with new terms.

____________________

Endnotes

23 J.N. Keynes, Scope and Method of Political Economy (London: Macmillan, 1891), p. 153.

24 Ibid., p. 156 (italics added).

25 J.E. Cairnes, Character and Logical Method of Political Economy (London: Macmillan, 1875), p. 146.

26 H. Sidgwick, The Principles of Political Economy (London: Macmillan, 1901), p. 62.

27 Ibid., p. 60.

28 Palgrave’s Dictionary. Article on “Definition.”

29 J. S. Mill, quoted in Cairnes, Method of Political Economy, p. 151.

30 T. R. Malthus, Definitions in Political Economy (London: John Murray, 1836), pp. 4–5.

CHAPTER II. VALUELESS RESOURCES↩

(1) Valueless idle resources are those which it would not pay any individual to employ, even if no charge were made for their use↩

THE FIRST form of idleness, we have termed “valueless resources.” Two conditions might be understood by this term: first, resources of no capital value; second, resources which at any time it would not pay any individual to employ for any purpose, even if no charge were made for their use.1 We shall adopt the second meaning as some resources may be usefully regarded as temporarily valueless; and some resources may have no capital value or a negative capital value, and yet provide valuable services and be valuable in our sense. It is easy to illustrate the conception in the case of natural resources. Orthodox economics has at all times recognized that there exists a huge amount of unemployed natural resources of this type, more and more of which, with developing technique and expanding population, have been observed first, to be drawn into active exploitation; and second, when they are scarce, to acquire capital value. Much unoccupied land falls into this category. Another example is that of the tides which are a source of immense potential power which it seldom pays, at present, to exploit. Equipment, and even the powers of human beings, can be conceived of as falling under the heading of “valueless resources,” although it is less easy to think of instances.

(2) The range of valuable resources may expand or contract↩

Resources may be employed but valueless. Uncongested rivers, and oceans, and the air that we breathe, may be regarded as examples. No scarcity, or an infinitesimal scarcity attaches to the services of marginal resources in such cases. No social problem arises, as Hume pointed out in 1777,2 in respect of the utilization of productive powers of this kind. If they are not employed, it is clearly because cooperant resources can be better employed elsewhere. They make no claim on the value of what is produced. But the more important examples of utilized but valueless resources are to be found where economic change is tending to confer value on them; and they are important because of the light which they throw upon the nature of the employment of resources which lie within the range of valuable resources. The case of land is clearest because we can conceive of the range in terms of the economically arbitrary notion of area. But the conception of a boundary or margin within which resources have some value and outside of which they are without value can apply to all resources, although there can be no idea of measurement of the range so imagined. The position of this boundary may change: it may be extended or it may be drawn in. That is, the compass of resources possessing some scarcity may vary.

(3) The range of valuable resources does not reflect the effectiveness of the response to consumers’ (or some other) sovereignty↩

Such variations are of importance in studies of idleness; but it must be recognized that they do not indicate the extent to which the preferences of the community are receiving the most effective satisfaction. In other words, variations in the range of valuable resources do not correspond in any certain way with any of the conceptions to which different definitions of social or national income have attempted to give concreteness. As we have already argued, there can be no criterion of the size of production as a whole. The conception of the effectiveness of response to consumers’ sovereignty or some other sovereignty, a response which is not subject to numerical measurement, is the only logically satisfactory criterion of effective production. We make this point at this stage in order to emphasize the error of the very likely assumption that, if the range of valuable resources happens to contract, it is necessarily a phenomenon to be deplored. The point may be illustrated by consideration of the case of an increased demand for leisure, which is one of the causes of what has been termed a “decreased propensity to consume.” Although, ceteris paribus, some physical resources tend to lose value in such a case,3 the result itself is in no sense to be regretted in the light of the consumers’ sovereignty ideal. On the other hand, if there is a similar decreased willingness to cooperate through exchange, owing to a collusive (or State enforced) reduction of the hours of labor, with work-sharing intention, there will be a similar tendency for some cooperant physical resources to lose value (and perhaps to fall valueless) in a manner which does conflict with the ideal. It is probable that most withholdings of capacity (through price or wage-rate fixations, output restrictions, or other protections of private income-rights) have the effect of causing the range of valuable resources to contract; and it is only when these policies are the origin of such idleness that there is any social loss reflected.4

(4) The vague phrase “increase in economic activity” can only have meaning if it refers to a fall in the proportion of valuable idle resources to all valuable resources↩

The question of the position of the margin between valuable and valueless resources may be important for some purposes but it is obviously not the problem with which those writers who use phrases like “an increase in the general level of economic activity” are concerned. If that phrase is taken to mean an improvement in the efficiency with which consumers’ preferences (or some other sovereignty) are being satisfied, it has no obvious relation to this margin. If, on the other hand, that phrase means a fall in the proportion between resources which have value but are idle and all resources which have value, it does have some meaning, although most abstractions of the nature of “general levels” are dangerous.

(5) Purely valueless equipment can have no net scrap value↩

In the case of equipment, the definition of “valueless resources” is not as easy as with the “gifts of nature.” We have the complication that the idle resources may have a net positive scrap value although no immediate hire value. (We can define “scrapping” as the process of destroying specialization.) Equipment of a given degree of specialization may be thought of as valueless when it would not pay any individual to use it, for any purpose, even if no charge greater than the interest on its net positive scrap value were made. But, ceteris paribus, equipment will be scrapped when its net positive scrap value exceeds its specialized value. Purely valueless equipment can exist only when the costs of scrapping are greater than the scrap is expected to realize.

(6) Resources are not valueless because the costs of depreciation cannot be earned↩

The fact that, in any instance, depreciation might not be covered if a particular piece of equipment were employed in production (i.e., if the earnings did not cover the sum required to maintain its original physical state) would not bring it into the valueless resources category. To permit a machine to wear out may be socially (or privately) the most profitable way of scrapping it. The excess of its immediate hire value above the interest on its net value as realized material or parts can be regarded as reflecting the immediate specialized value of its services.

(7) Idle unscrapped resources possessing scrap value may be in pseudo-idleness↩

But if a plant whose services are valueless in this sense (i.e., as specialized resources), yet has a positive net scrap value, is allowed to remain unscrapped, then its continued idle existence may be due to the fact that it is waiting for an expected revival of demand or an expected fall in costs.5 If these expectations alone account for its continued idle existence, it falls into a different category which we shall explain later, namely, “pseudo-idleness.” We use this term for the case in which the supposedly idle resources do have scrap or other market value. They are in “pseudo-idleness” when they are being productively withheld from some other use, “scrapping” being one of these other uses.

(8) Idle resources with capital value but no scrap or hire value are “temporarily valueless”↩

If equipment has no positive net scrap value and no immediate hire value, whilst it still has capital value, it must be regarded as temporarily valueless. Of course, its capital value reflects expectations, not prophecy; and the word “temporarily” merely implies an individual’s estimate.

(9) The idleness of equipment is seldom due to its being purely valueless↩

The practical implications of these considerations are important. Cases of purely valueless plant and equipment (i.e., whose costs of scrapping are estimated to be greater than the value of the scrap),6 seem hardly likely to be frequent, although exhausted mines and derelict jetties on silted rivers are clear examples. With railways and other public utilities, instances are imaginable, but very difficult to discover in practice. Common-sense observation suggests that the condition is virtually nonexistent in the idle plant and equipment which we occasionally contemplate in the industrial world. It always seems that in any price situation in our present experience, there is hardly any specialized plant in the industrial system that an entrepreneur (protected from the coercive power which monopoly confers on others) could not use profitably if he were allowed free access to it; if, that is, no charge for hire entered into his costs. Moreover, we believe that the “most profitable” use would seldom involve scrapping, the destruction of specialized capacity.

(10) Full utilization of existing resources is more likely to cause the range of valuable resources to expand than to contract↩

But such an empirical judgment may be misleading, for it is based on the assumption of the continuance of the existing price situation. If our economic system permitted the community to make full use7 of available resources, the existing price situation would not remain. The effect might conceivably be that in any representative case the cheapening of the product through the full utilization of all available resources would exterminate a large part of the value of much equipment, and so cause it to be realized as scrap or, if it were highly specialized, to push it into the category of valueless resources. But we can hardly assume with confidence that this would happen more often than not if the full capacity in many individual industries were utilized. And even if it were likely to happen, it does not follow that the general release of productive power would have this effect; for the manifold fields of profitable employment of resources when their services are cheap, and the growing diversity of consumers’ preferences which can be expected to result (from economies achieved in realizing ends which we are already able to satisfy under the present regime8) suggests that it is much more likely that the bounds outside of which “valueless resources” lie will be extended. Increased “scrapping” might be resorted to; but that does not mean increased idleness. Unless leisure, or other things requiring less of the services of physical resources, happen to be more wanted in consequence of the release of productive power, the willingness to cooperate through exchange will tend to increase and the range of valuable resources to extend.

(11) Resources which have negative capital value but provide valuable services are unimportant↩

Resources are not valueless in our sense simply because the liabilities attached to their possession are equal to or greater than their value as assets, or because their continued existence involves costs equal to or greater than the revenues they can earn. Indeed, the resources may be of negative capital value, but still have hire value, and hence be valuable as resources so long as they exist. Thus, an edifice like the Eiffel Tower may well cost more to preserve than the receipts obtainable from its use. It may, nevertheless, be preserved because, if neglected, it will be a public danger whilst the interest on the cost of scrapping it is greater than the sum required to preserve it. In the meantime, however, it can provide valuable (i.e., scarce) services. Hence it will not be valueless in our sense. Again, consider the dumps of coal mines which are often a nuisance to development. It has been recently discovered that they can be used for brick-making. Now it is conceivable that in some circumstances they could be utilized for this purpose provided the manufacturer of the bricks was paid a subsidy by the mining corporation for removing the dumps. Thus, the materials would be sold at, so to speak, a negative value; but they would at the same time be valuable resources. Their negative value would be small or large according to whether the demand for bricks was large or small. It might be more realistic to regard the material in the dumps as a by-product of services rendered to the owners of the mine. But the point which must be made is that the resources would not be utilized even if no charge was made for their use. The subsidy, or a contract to remove the dumps, would be a necessary condition. The situation arises when resources obtain value because their utilization enables other costs to be reduced. It is a special case of joint supply, and of hardly any practical importance. We have mentioned it for completeness and because it might lead to misconceptions.

(12) Except for imbeciles, the sick and children, there are no parallels to valueless resources in labor↩

In the case of labor it is even more difficult to conceive of examples of “valueless resources.” Imbeciles and the seriously sick might be regarded as qualifying, in the sense that there are no means of making their employment profitable. Convicts, the condition of whose punishment or isolation makes impracticable their undertaking work in competition with free labor, fall under this heading also. But if their services are not utilized because “convict labor” is thought of as, say, “unfair competition,” they cannot be classed as “valueless resources.”9 Concerning children; although we are not in the habit of regarding the young as property, there is a sense in which they can be thought of as having capital value from the outset. Hence, they might be described as “temporarily valueless.” Parents, guardians and society may, however, be observed to be investing in the young from their birth onwards. In this situation they are best thought of as employed; although, as we shall show later, the actual position is often difficult to interpret. When they reach the age at which they are capable of remunerative work (and we know from history that this is a very early age), they may be withheld from the labor market (a) because to enter it would interfere with their education (i.e., the process of investment in them); or (b) because early employment may destroy their powers and hence the value of their services later; or (c) because leisure is demanded on their behalf as an end in itself; or (d) because their unpaid domestic service inside the home is worth more to their parents than they could add to the family earnings from work outside; or finally, (e) because their competition in the labor market is not wanted. In the first and second cases they do not happen to be in the labor market, but they are employed in the sense in which capital equipment in the course of its own production is employed. In part, both cases may be regarded as examples of “pseudo-idleness.” In the third case it is a type of “preferred idleness.” In the fourth case the children are not idle in any sense. And in the fifth case it is an example of “enforced idleness” or “withheld capacity.” The idleness of the very old is usually “preferred idleness” of the leisure kind, but where the receipt of a pension is contingent upon remunerative work not being undertaken, it must be classified as “participating idleness.”

(13) The “unemployed” are not valueless↩

If we consider the actual “unemployed,” it is impossible to regard them as “valueless resources.” They are not unemployed for that reason. At low enough wage-rates they could practically all be profitably absorbed into some task, even if their earnings were insufficient in many cases to pay for physically or conventionally necessary food, let alone clothing and housing. In a slave economy, such people might be allowed to die off; or they might, for sentimental reasons, be kept alive. But in the latter case, their efforts would still be available and they would not be “valueless resources” so long as the utilization of their efforts produced more than the extra outgoings incurred. Imagine a society which decides that a national minimum of subsistence shall be provided for those whose earnings fail to procure a tolerable standard of living (tolerable, that is, in the collective judgment). It is obviously unnecessary in such a society that an individual’s earning power shall equal or exceed his freely received allowance in order that his capacity shall be regarded as having positive value. And where philanthropic poor relief exists, the same principle holds. Because a blind man in receipt of services and pocket money equivalent to 30s. a week from a charitable institution can contribute to its funds from the basket-making which he is called upon to do a mere 15s. a week, it would be wrong to think of his services as valueless. Thus, both in respect of capital equipment and labor, idleness due to absence of value is almost certainly rare and unimportant. That temporary absence of hire value, accompanied by a positive net scrap value which we shall call “pseudo-idleness,” is an entirely different sort of condition.

(14) Natural resources which have once been valuable seldom lose all their value, so that any subsequent idleness must be due to other causes↩

It is not usual for “practical” writers and reformers to think of unexploited natural resources as “unemployed.” But they are not essentially different, economically, from labor and produced resources. Now it can be observed as a fact of experience that once natural resources have acquired value and been utilized or specialized they hardly ever become valueless (a) unless their physical nature changes (as under soil erosion or exhaustion, for example); or (b) unless they are the refuse from production (mine dumps, for example); or (c) unless huge shifts of demand (as from war to peace, for example) take place; or (d) unless communities migrate (from exhausted mining districts, for example). In settled communities, the writer can think of very few cases of land going out of cultivation and pasturage, except under the coercions or collusions of agricultural “cooperation” and State policy, or where soil exhaustion has destroyed its productive qualities, or under apathetic ownership in the case of “social farms,” or where estates are reserved as public or private parks.10 Still less can instances be found of land, once occupied, losing all capital value; and the continued11 existence of some capital value in such land suggests that in spite of apparent idleness, some services of an income nature are being provided by it. This serves to illustrate further our main point that, whilst it is theoretically conceivable that certain types of labor, capital equipment and once utilized resources can pass outside the margin of profitable employment (when, say, demand is transferred from one set of preferences to another), valueless resources in a “pure” form other than untouched natural resources seem to be rare, and an unimportant type of idleness. The phenomena which reformers deplore when they discuss trade depression are not of this nature.

Endnotes

1 The phrase “even if no charge were made for their use” covers all but one unimportant special case discussed below (para. 11).

2 D. Hume, An Inquiry Concerning the Principles of Morals, opening of chap. III, part (i) “Of Justice.”

3 See below, para. 11.

4 One

5 This is simply a special case of the general position which exists when the present hire value of unscrapped plant is less than the interest obtainable on the capital realizable from scrapping.

6 The presence of this condition alone obviously does not make resources valueless. It is simply one necessary condition. If it is absent, valuelessness is not present.

7 See chap. 1, para. 10, for conception of “full employment.”

8 For the prices in one industry are costs to a cooperant industry.

9 It is not necessary, as our argument in the previous paragraph made clear, that the costs of housing, feeding and clothing such convicts should be covered by what they can be made to earn, in order to take them outside the category of “valueless resources.” These costs have to be incurred in any case.

10 This is a particular case of utilization.

11 I.e., it cannot be explained as “temporary absence of hire value.”

CHAPTER III. PSEUDO-IDLENESS↩

(1) Uncompleted equipment in process of construction must be regarded as employed↩

HOW SHALL WE regard productive resources which are in process of being specialized? Surely they must be thought of as employed. The materials in a half-completed ship are no more idle, in any useful sense, than the stocks on which it rests. But this form of employment may be accompanied by other forms of idleness, a possibility of some importance which complicates the position. Uncompleted equipment is only fully employed (in our sense of optimum utilization) when investment in it is proceeding at the social optimum rate, given existing expectations. Thus, while the vessel “534” which became the Queen Mary was actually under construction, the fact that it was not actively earning did not mean that the resources embodied in it were unemployed. But when work on it was stopped because the proposition ceased to be “profitable” to the company owning it—in the light of indications from the ocean freight market—it stood idle in one or more of the other senses which we have to discuss.

(2) Individuals adding to their powers through education are employed↩

We find parallels in the case of labor. The clearest example is in the case of young children. At the outset, they have no usable powers; but as such powers do develop, the most profitable use of them (given contemporary standards of social goodness) is usually their improvement through that form of investment represented by the costs of upbringing and education. And throughout life, when individuals are out of the labor market because the addition to their future hire value from education more than compensates for immediate earnings foregone, they ought properly to be regarded as employed. The determining consideration is whether investment in them is proceeding at the social optimum rate. Thus, the raising of the age of voluntary school leaving may have the real object of keeping more juveniles out of the employment market, and it is sometimes quite frankly demanded for this reason. Their condition then obviously partakes of the nature of what we call “withheld capacity” or “enforced idleness” rather than that of being subject to investment. If the standard of schooling available should be such that the juveniles are likely actually to benefit in the long run, then, whatever the motive, the process of investment in them is the explanation of their condition.

(3) Individuals conserving their powers through rest are employed↩

Similar to the case of training is that of the maintenance of physical and mental efficiency in human beings by rest and recuperation. Thus, normal sleeping hours cannot be regarded as idleness; and there is a recuperative (and hence productive) aspect about most leisure.1 Genuine efficiencies achievable through the mere postponement of children’s earnings may conceivably be the best employment of their powers, i.e., irrespective of the education which it incidentally permits.

(4) Individuals actively “prospecting” for remunerative jobs are employed↩

These specific cases of employment have, however, never been mistaken for unemployment. But other cases falling into the same category have been so mistaken. Thus, a worker in a non-unionized and unprotected trade2 whose firm closes down in depression may refuse immediately available work in a different job because he feels that to accept it will prevent him from seeking for better openings in his own regular employment or other occupations for which he is peculiarly fitted. Let us for a moment ignore the case in which he is passively waiting and merely preserving his availability. When actively searching for work, the situation is that he is really investing in himself by working on his own account without immediate remuneration. He is prospecting. He is doing what he would pay an efficient employment agency to do if the course of politics had allowed that sort of institution to emerge in modern society. He judges that the search for a better opening is worth the risk of immediately foregone income. If his relatives, or his friends, or the State are keeping him then, in a sense, they also may sometimes be regarded as investing in him, and it may still be wrong to think of him as idle. But this condition is very difficult to distinguish in practice from the various types of “preferred idleness.” Thus, unemployment insurance may lessen his incentive to find work and an apparent or supposed search for the best employment opportunities may be a mask for what is known as “loafing.”

(5) Pseudo-idleness resembles passive employment but is not an identical condition↩

These last examples of employment are seldom treated as employment, but as the workers concerned are serving the community best in their apparent idleness, and as they themselves are remunerated for the service (when their judgment is right—i.e., when their powers have really been guided to employers who can use them most profitably), we ought properly to think of the idleness as spurious. The purpose of this chapter is, however, to draw attention to a similar category of employment which is even more easily mistaken for idleness. But it is not quite the same, and we allot to it a separate category which we call “pseudo-idleness.” It is a condition which is common and has many forms; and it constitutes a phenomenon of the greatest importance in any study of unemployment of labor, or “surplus capacity” in material resources.

(6) Pseudo-idleness exists when the capital value of resources is greater than their scrap value, whilst their net hire value is nil↩

One of the most common forms of “pseudo-idleness” is that which exists when resources are being retained in their specialized form (i.e., not being scrapped) because the productive service of carrying them through time is being performed. This condition exists when their capital value is greater than their net positive scrap value, whilst their immediate hire value is nil. This last phrase may require some explanation. Resources must be reckoned as of “no hire value” even if they can be hired out but (a) the price obtainable is insufficient to cover depreciation and loss of specialization, and (b) there is a greater consequent loss or a smaller consequent gain to capital value. That is, we must conceive of a net hire value equal to gross hire value minus depreciation. For when depreciation is not covered, the supposed hire price in part covers the realization of resources as scrap. Thus, suppose expectations concerning the revival of demand to remain unchanged, then, for a piece of equipment to be in “pseudo-idleness,” it is necessary that an entrepreneur should be unable to utilize it profitably whilst maintaining its physical efficiency. The proceeds of the complementary use must be insufficient to finance depreciation in order to bring it into the socially productive category which we call “pseudo-idleness.”

(7) The service rendered by resources in pseudo-idleness is that of “availability”↩

Thus, the essence of pseudo-idleness is the preservation of availability. For example, in a Communist country, a seaside hotel run for foreigners might become the free abode of the local poor during the “offseason”; but if the resulting dilapidations and costs of supervision could not be covered by some small charge, then the best employment of the building would be to close it down. Such a condition would be socially productive,3 and it could therefore be brought under this heading. Another example is that of a piece of building land which is kept vacant in anticipation of site scarcity in subsequent years. It is obvious also that, in any given state of knowledge and institutions, there are resources which perform their most wanted services through their mere passive existence—the service of “availability.” The resources concerned might be capable of being hired out for certain other purposes, but they would then directly lose their availability for some special task (which entrepreneurs are prepared to bet will be wanting their services later). Hence their present utilization comes to be regarded as likely to bring about a more than countervailing loss in capital value. The loss of availability is a particular case of loss of specialization. Applying our definition in paragraph 6, therefore, they should be rightly regarded as of no immediate net hire value.

(8) Pseudo-idleness can be illustrated in capital consumers’ goods and capital producers’ goods↩

The simplest illustrations of the productive service of mere availability seem almost fatuous. Consider capital consumers’ commodities of occasional utilization like the gramophone which is played only at odd times, the silk hat which is worn only at weddings and funerals, or the picture which is only providing obvious “satisfactions” when it is actually looked at. To refer to these as in “pseudo-idleness” may appear ironical. But closely parallel cases clearly involve problems of some importance. Thus, I may have a dozen suits of clothes, three cars (two of which are always in the garage), and so forth. One obvious aspect of all these things is that they are purchased “to be available.” A good deal of plant in the industrial world is also in this state. It exists because from time to time it will happen to be wanted. The most indubitable cases in the field of producers’ goods are those in which the phenomenon of “pseudo-idleness” has some regular periodicity. Thus, the plant of a salmon canning factory will not be working out of season, but it will not be unproductive because of that. Ploughs and harvesting machinery may have no alternative uses until the return of the appropriate season. The bottling apparatus of a jam factory may be still for the early hours of each conventional working day. Such regular, recurrent idleness can be confidently classed as “pseudo-idleness.” Spasmodic “pseudo-idleness,” on the other hand, can often be distinguished from idleness in other senses only with much uncertainty.