Voltaire, Candide, or The Optimist (1759)

|

|

| François-Marie Arouet (“Voltaire”) (1694-1778) |

This is part of a collection of works by Voltaire.

Source

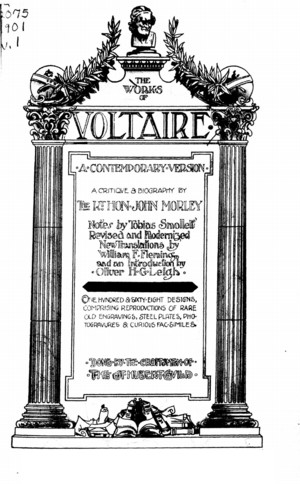

The Works of Voltaire. A Contemporary Version. A Critique and Biography by John Morley, notes by Tobias Smollett, trans. William F. Fleming (New York: E.R. DuMont, 1901). In 21 vols. Vol. I, Candide Part I, pp. 59-208; Part II, pp. 209-281.

See also the facs. PDF of this translation.

Note: This edition includs the spurious Part II which appeared in an edition of 1761/3. It is probably not be Voltairte but by the abbé Dulaurens. The Voltaire Foundation in Oxford has this comment on their website:

Following the hugely successful publication of Candide in early 1759, there appeared in 1760 a sequel, Candide, seconde partie – an amusing work that we now attribute to the abbé Dulaurens, but that at the time was widely attributed to Voltaire himself, so much so that it was not uncommon for the two parts of Candide to appear together as ‘one’ work by Voltaire. Gradually it became accepted that Voltaire was not the author of the second part, so this practice declined – except in the United States, where the two parts of Candide continued to be published together well into the twentieth century.

Table of Contents

- PUBLISHER’S PREFACE.

- INTRODUCTION.

- the many-sided voltaire.

- OLIVER GOLDSMITH ON VOLTAIRE.

- victor hugo on voltaire.

- CANDIDE;

OR, THE OPTIMIST.

- CHAPTER I. how candide was brought up in a magnificent castle and how he was driven thence.

- CHAPTER II. what befell candide among the bulgarians.

- CHAPTER III. how candide escaped from the bulgarians, and what befell him afterwards.

- CHAPTER IV. how candide found his old master pangloss again and what happened to him.

- CHAPTER V. a tempest, a shipwreck, an earthquake; and what else befell dr. pangloss, candide, and james the anabaptist.

- CHAPTER VI. how the portuguese made a superb auto-da-fé to prevent any future earthquakes, and how candide underwent public flagellation.

- CHAPTER VII. how the old woman took care of candide, and how he found the object of his love.

- CHAPTER VIII. cunegund’s story.

- CHAPTER IX. what happened to cunegund, candide, the grand inquisitor, and the jew.

- CHAPTER X. in what distress candide, cunegund, and the old woman arrive at cadiz; and of their embarkation.

- CHAPTER XI. the history of the old woman.

- CHAPTER XII. the adventures of the old woman continued.

- CHAPTER XIII. how candide was obliged to leave the fair cunegund and the old woman.

- CHAPTER XIV. the reception candide and cacambo met with among the jesuits in paraguay.

- CHAPTER XV. how candide killed the brother of his dear cunegund.

- CHAPTER XVI. what happened to our two travellers with two girls, two monkeys, and the savages, called oreillons.

- CHAPTER XVII. candide and his valet arrive in the country of el dorado—what they saw there.

- CHAPTER XVIII. what they saw in the country of el dorado.

- CHAPTER XIX. what happened to them at surinam, and how candide became acquainted with martin.

- CHAPTER XX. what befell candide and martin on their passage.

- CHAPTER XXI. candide and martin, while thus reasoning with each other, draw near to the coast of france.

- CHAPTER XXII. what happened to candide and martin in france.

- CHAPTER XXIII. candide and martin touch upon the english coast—what they see there.

- CHAPTER XXIV. of pacquette and friar giroflée.

- CHAPTER XXV. candide and martin pay a visit to seignor pococuranté, a noble venetian.

- CHAPTER XXVI. candide and martin sup with six sharpers—who they were.

- CHAPTER XXVII. candide’s voyage to constantinople.

- CHAPTER XXVIII. what befell candide, cunegund, pangloss, martin, etc.

- CHAPTER XXIX. in what manner candide found miss cunegund and the old woman again.

- CHAPTER XXX. conclusion.

- Endnotes

- PART

II.

- CHAPTER I. how candide quitted his companions, and what happened to him.

- CHAPTER II. what befell candide in this house—how he got out of it.

- CHAPTER III. candide’s reception at court and what followed.

- CHAPTER IV. fresh favors conferred on candide; his great advancement.

- CHAPTER V. how candide became a very great man, and yet was not contented.

- CHAPTER VI. the pleasures of candide.

- CHAPTER VII. the history of zirza.

- CHAPTER VIII. candide’s disgusts—an unexpected meeting.

- CHAPTER IX. candide’s disgraces, travels, and adventures.

- CHAPTER X. candide and pangloss arrive at the propontis—what they saw there—what became of them.

- CHAPTER XI. candide continues his travels.

- CHAPTER XII. candide still continues his travels—new adventures.

- CHAPTER XIII. the history of zenoida—how candide fell in love with her.

- CHAPTER XIV. continuation of the loves of candide.

- CHAPTER XV. the arrival of wolhall—a journey to copenhagen.

- CHAPTER XVI. how candide found his wife again and lost his mistress.

- CHAPTER XVII. how candide had a mind to kill himself, and did not do it—what happened to him at an inn.

- CHAPTER XVIII. candide and cacambo go into a hospital—whom they meet there.

- CHAPTER XIX. new discoveries.

- CHAPTER XX. consequence of candide’s misfortune—how he found his mistress again—the fortune that happened to him.

- Endnotes

PUBLISHER’S PREFACE.

Students of Voltaire need not be told that nearly every important circumstance in connection with the history of this extraordinary man, from his birth to the final interment of his ashes in the Panthéon at Paris, is still matter of bitter controversy.

If, guided in our judgment by the detractors of Voltaire, we were to read only the vituperative productions of the sentimentalists, the orthodox critics of the schools, the Dr. Johnsons, the Abbé Maynards, Voltaire would still remain the most remarkable man of the eighteenth century. Even the most hostile critics admit that he gave his name to an epoch and that his genius changed the mental, the spiritual, and the political conformation, not only of France but of the civilized world. The anti-Voltairean literature concedes that Voltaire was the greatest literary genius of his age, a master of language, and that his historical writings effected a revolution. Lord Macaulay, an unfriendly critic, says: “Of all the intellectual weapons that have ever been wielded by man, the most terrible was the mockery of Voltaire. Bigots and tyrants who had never been moved by the wailings and cursings of millions, turned pale at his name.” That still more hostile authority, the evangelical Guizot, the eminent French historian, makes the admission that “innate love of justice and horror of fanaticism inspired Voltaire with his zeal in behalf of persecuted Protestants,” and that Voltaire contributed most powerfully to the triumphs of those conceptions of Humanity, Justice, and Freedom which did honor to the eighteenth century.

Were we to form an estimate of Voltaire’s character and transcendent ability through such a temperate non-sectarian writer as the Hon. John Morley, we would conclude with him that when the right sense of historical proportion is more fully developed in men’s minds, the name of Voltaire will stand out like the names of the great decisive movements in the European advance, like the Revival of Learning, or the Reformation, and that the existence, character, and career of Voltaire constitute in themselves a new and prodigious era. We would further agree with Morley, that “no sooner did the rays of Voltaire’s burning and far-shining spirit strike upon the genius of the time, seated dark and dead like the black stone of Memnon’s statue, than the clang of the breaking chord was heard through Europe and men awoke in a new day and more spacious air.” And we would probably say of Voltaire what he magnanimously said of his contemporary, Montesquieu, that “humanity had lost its title-deeds and he had recovered them.”

Were we acquainted only with that Voltaire described by Goethe, Hugo, Pompery, Bradlaugh, Paine, and Ingersoll, we might believe with Ingersoll that it was Voltaire who sowed the seeds of liberty in the heart and brain of Franklin, Jefferson, and Thomas Paine, and that he did more to free the human race than any other of the sons of men. Hugo says that “between two servants of humanity which appeared eighteen hundred years apart, there was indeed a mysterious relation,” and we might even agree that the estimate of the young philanthropist Édouard de Pompery was temperate when he said, “Voltaire was the best Christian of his times, the first and most glorious disciple of Jesus.”

So whatever our authority, no matter how limited our investigation, the fact must be recognized that Voltaire, who gave to France her long-sought national epic in the Henriade, was in the front rank of her poets. For nearly a century his tragedies and dramas held the boards to extravagant applause. Even from his enemies we learn that he kept himself abreast of his generation in all departments of literature, and won the world’s homage as a king of philosophers in an age of philosophers and encyclopædists.

He was the father of modern French, clear, unambiguous, witty without buffoonery, convincing without truculency, dignified without effort. He constituted himself the defender of humanity, tolerance, and justice, and his influence, like his popularity, increases with the diffusion of his ideas.

No matter what the reader’s opinion of Voltaire’s works may be, it will readily be conceded that without these translations of his comedies, tragedies, poems, romances, letters, and incomparable histories, the literature of the world would sustain an immeasurable loss, and that these forty-two exquisite volumes will endure as a stately monument, alike to the great master and the book-maker’s artcraft he did so much to inspire.

E. R. D.

INTRODUCTION.

Voltaire wrote of himself, “I, who doubt of everything.” If, in this laudable habit of taking second thoughts, some one should ask what were the considerations that prompted this exceptional reproduction of what is a literature rather than a one-man work, they are indicated in these Reasons Why:

1. Because the Voltaire star is in the ascendant. The most significant feature of the literary activity now at its height has been the vindication of famous historic characters from the misconceptions and calumnies of writers who catered to established prejudice or mistook biassed hearsay for facts. We have outgrown the weakling period in which we submissively accepted dogmatical portrayals of, for example, Napoleon as a demon incarnate, or Washington as a demi-god. We have learned that great characters are dwarfed or distorted when viewed in any light but that of midday in the open. Historians and biographers must hereafter be content to gather and exhibit impartially the whole facts concerning their hero, and thus assist their readers as a judge assists his competent jury.

2. Because, among the admittedly great figures who have suffered from this defective focussing, no modern has surpassed, if indeed any has equalled, Voltaire in range and brilliance of a unique intellect, or in long-sustained and triumphant battling with the foes of mental liberty. Every writer of eminence from his day to ours has borne testimony to Voltaire’s marvellous qualities; even his bitterest theological opponents pay homage to his sixty years’ ceaseless labors in the service of men and women of all creeds and of none. The time has come when the posterity for whose increased happiness he toiled and fought are demanding an opportunity to know this apostle of progress at firsthand. They wish to have access to the vast body of varied writings which hitherto have been a sealed book except to the few. For this broad reason, in recognition of the growing desire for a closer acquaintance with the great and subtle forces of human progress, it has been determined to place Voltaire, the monarch of literature, and the man, before the student of character and influence, in this carefully classified form.

3. Because the field of world-literature is being explored as never before, and in it Voltaire’s garden has the gayest display of flowers. The French genius has more sparkle and its speech a finer adaptability than ours. First among the illustrious, most versatile of the vivacious writers of his nation, Voltaire wielded his rapier quill with a dexterity unapproached by his contemporaries or successors. It still dazzles as it flashes in the sunshine of the wit that charmed even those it cut the deepest. Where his contemporary reformers, and their general clan to this day, deal blows whose effectiveness is blunted by their clumsiness, this champion showed how potent an ally wisely directed ridicule may become in the hands of a master. Every page of his books and brochures exemplifies Lady Wortley Montagu’s maxim:

Satire should, like a polished razor keen,

Wound with a touch that’s scarcely felt or seen.

But when blood-letting was needed the Voltaire pen became a double-edged lancet.

4. Because biography is coming into higher appreciation, as it should. A man’s face is the best introduction to his writings, and the facts of his life make the best commentary on them. Where is there the like of that extraordinary, fascinating, enigmatical, contradictory physiognomy of Voltaire? And where is there a life so packed with experiences to match? His writings mirror the mind and the life. Philosopher, historian, poet, theologian, statesman, political economist, radical reformer, diplomatist, philanthropist, polemic, satirist, founder of industries, friend of kings and outlaws, letter-writer, knight-errant, and Boccaccio-Chauceresque teller of tales, Voltaire was all these during his sixty-two years of inexhaustible literary activity. “None but himself could be his parallel.” No other author’s works combine such brilliant persiflage with such masculine sense, or exhibit equal fighting powers graced by equal perfection of literary style.

5. Because Voltaire stands as an entertainer in a class apart from others, such as Balzac, Hugo, and his country’s novelists and poets. They bring us draughts from the well in their richly chased cups; Voltaire gives us the spring, out of which flows an exhaustless stream of all that makes fiction alluring, poetry beautiful, epigram memorable, common sense uncommonly forceful, and courageous truth-speaking contagious. His delicious humor and mordant sarcasm amuse, but they also inspire. There is moral purpose in every play of his merry fancy. Every stroke tells. A mere story, however charming, has its climax, and then an end, but it is next to impossible to read any page in any book of Voltaire’s, be it dry history, grave philosophy, plain narrative, or what not, without some chance thought, suggestion, or happy turn of phrase darting out and fixing itself in one’s mind, where it breeds a progeny of bright notions which we fondly make believe are our own.

6. Because, lastly, no private library worthy the name is complete without Voltaire. French editions are found upon the most-used book-shelves of collectors who revel in the treasures of French literature, but the present edition has the advantage, besides the prime one of being in strong, nervous English, of a methodical arrangement which will prove helpful to every reader; also it gives closer and more acceptable readings of many passages, in original translation and in paraphrase.

The original notes by Dr. Smollett, author of “Humphrey Clinker,” and other racy novels of eighteenth-century life, are retained where helpful or in his characteristic vein. So are Ireland’s lively and edifying commentaries on La Pucelle, rich in historical and antiquarian interest.

Lovers of Goldsmith—who never had an enemy but himself—will welcome the charming pages here rescued from his least-read miscellanies, in which he draws the mental and personal portrait of Voltaire, whose genius he cordially admired, and whose character he champions. The critical study of Voltaire by the Right Honorable John Morley, some time a member of Gladstone’s cabinet and his biographer, needs no other commendation than its author’s name.

Victor Hugo’s lofty oration on the hundredth anniversary of Voltaire’s death, links the names and fame of the two great modern writers of France. The translations and textual emendations by W. F. Fleming are a feature of this edition.

The volumes are illuminated by as artistic and costly pictures as can be procured. The antique flavor of the contemporary illustrations is preserved in a number of original steel engravings, etchings, and woodcuts, besides choice photogravure and later process plates. The volumes, as a whole, will be recognized as an ideal example of typography and chaste binding.

the many-sided voltaire.

Choose any of Voltaire’s writings, from an epigram to a book, and it impresses the mind with a unique sense of a quality which it would be absurd to liken to omniscience, though mere versatility falls short on the other side. So the tracing of his life-experiences leaves us puzzled for a conventional term that shall exactly fit the case. The truth is that ordinary terms fail when applied to this man and to his works. It is unprofitable to measure a giant by the standards of average men. The root-cause of all the vilification and harsh criticism hurled at Voltaire by ordinarily respectworthy people has been the hopeless inability of the church-schooled multitude to grasp the free play of a marvellous intellect, which could no more submit to be shackled by the ecclesiasticism of its day than the brave Reformer of Galilee could trim his conscience to fit the saddles of Jewish or Roman riders. To condense the events of this remarkably chequered career in a few pages is impossible without omitting minor items which, unimportant in themselves, yet reflect the flashings of the lesser facets which contribute to the varied lights of the diamond. Mr. Morley’s lucid and powerful study of Voltaire, in this series, leaves room for the following attempt at a reasonably brief outline of the events in this multiform life. The object is to aid in understanding the hidden conditions in which many of the strong, and sometimes apparently extravagant, utterances were produced.

Incidents in his Life.

The narrative is compiled from biographies written at various periods since 1778, and is enriched in being supplemented by the little-known tributes of the most charming English writer among Voltaire’s contemporaries, Oliver Goldsmith, who was personally acquainted with the great Frenchman, whose genius he admired as enthusiastically as he championed his character.

François Marie Arouet was born at Paris on November 21, 1694. He assumed the name de Voltaire when in his twenty-fifth year.

1711 —From the first, as a schoolboy, Voltaire outclassed his fellows. At the close of his sixth school year he was awarded prize after prize and crown after crown, until he was covered with crowns and staggered under the weight of his prize books. J. B. Rousseau, being present, predicted a glorious future for him. He was a good scholar, a favorite of his teachers, and admired and beloved by his companions.

Left school in August, aged nearly seventeen, tall, thin, with especially bright eyes as his only mark of uncommon good looks. He was welcomed to the Temple by such grand seigniors as the duke de Sully, the duke de Vendome, prince de Conti, marquis de Fare, and the other persons of rank forming their circle, who put him on a footing of perfect familiarity. He became a gay leader of fashion, flattered by the ladies, made much of by the men, supping with princes and satirizing the follies of the hour in sparkling verse.

1717 —Voltaire returned in the spring to Paris, where many uncomplimentary squibs were being circulated concerning the pleasure-loving regent, of which he was at once suspected, rightly or wrongly; he was arrested in his lodgings in the “Green Basket,” sent to the Bastille and assigned a room, which was ever after known as Voltaire’s room. Here he dwelt for eleven months, during which he wrote the “Henriade” and corrected “The Œdipe.”

1718 —Released April 11th, as a result of entertaining the regent with comedy, and changed his name, for luck, as he says himself, to Voltaire, a name found several generations back in the family of his mother.

1722 —M. Arouet, Voltaire’s father, died January 1st, leaving Armand, the orthodox son, his office, worth 13,000 francs a year, and to Voltaire property yielding about 4,000 francs a year. Voltaire was granted a pension of 2,000 francs by the regent. He loaned money at ten per cent. a year to dukes, princes and other grand seigniors with a determination to become independent. He always lived well within his income.

1726 —It was desirable to leave France for a time, hence Voltaire’s visit to England. His letters show how deeply he was impressed by the characteristics of the nation by whom he was so cordially welcomed. Voltaire having lost 20,000 francs through a Jewish financier, the king of England presented him with one hundred pounds.

1727 —He studied English so industriously that within six months he could write it well, and within a year was writing English poetry. He made many influential friends, and seems to have known almost every living Englishman of note. He studied Newton, Shakespeare, Milton, Dryden, Locke, Bacon, Swift, Young, Thomson, Congreve, Pope, Addison, and others. His two and a half years in England were as a post-graduate university course to him, and amidst his studies he still was a producer, completing unfinished works and preparing others for his London publisher. Newton and Locke—Locke in particular—inspired in Voltaire his strongest and best trait—the love of justice for its own sake.

1730–1731 —The first year after his return from England was comparatively peaceful, but in March of 1730 his friend, the brilliant actress, Adrienne Lecouvreur, died at the age of twenty-eight, and was refused Christian burial; Voltaire leaped forward with his accustomed magnanimity as her champion, unhesitatingly endangering his safety in so doing—always a true friend, always the helper of the weak and oppressed, always the advocate of justice, and always first to defend natural rights. In this year, too, he began the mock-heroic poem of ten thousand lines on Joan of Arc (“La Pucelle”), the keeping of which from his enemies caused him anxiety for years. Interferences in his publications by the authorities of Paris marked this year, and, restive and unsubdued, he looked elsewhere, with the result that in March of the next year, under pretence of going to England, he took up his abode in obscure lodgings in Rouen, where he passed as an exiled Englishman. Here he lived for six months—sometimes in a farmhouse—and did a prodigious amount of work, besides having his interdicted works published. Late in the summer of this year he returned to Paris, where, for the first time since returning from England, he took permanent quarters. These were luxurious ones in the hotel of the countess de Fontaine-Martel, at whose invitation he came and with whom he was friendly. Here were continuous gayeties, here his plays were performed, and here he had Cideville and Formont as near friends and helpful critics.

1732 —On August 13th, he had the satisfaction of having “Zaïre” successfully produced in Paris, then in Fontainebleau, then in London, and soon, amidst applause, in cities throughout all Europe. This October he spent in Fontainebleau, and in November he returned to his aged friend, the countess, in Paris.

1733 —During January he acted a leading part in the production of “Zaïre” with telling effect, and about this time this happy life was terminated by the death of the countess. Voltaire stayed for three months longer, and in May took lodgings with Démoulin, his man of business, in a dingy and obscure lane. Here two other poets, Lefèvre and Linant, were with him, and here he began to live more the life of a philosopher. He engaged in the importation of grain from Spain and was interested in the manufacture of straw-paper. In company with his friend Paris-Duverney, he took contracts for feeding the army, out of which he quickly realized over half a million francs. Business never interfered with his literary work, and while he fed the army he also produced verse for it.

1734 —Forty years of age. Voltaire had recently met the marquise du Châtelet. He was doubtless now the most conspicuous, almost the only, literary figure on the continent who wrote in the new, free spirit that began to dominate the few great minds of northern Europe. Booksellers in Europe found his writings profitable. Frederick, prince royal of Prussia, was his disciple. Two editions of his collected works had been published in Amsterdam, and he was in demand everywhere; but more trouble was brewing. J. B. Rousseau, piqued over a quarrel, wrote from his exile disparagingly of Voltaire, who, in his turn, wrote the “Temple of Taste,” which an enemy secured and published without the censor’s approval, and again Voltaire was in trouble. He dearly loved a fight, and he fought like a man—for truth, toleration, and justice—and he won. At this time he found time to bring about the marriage of the princess de Guise to the duke de Richelieu, and attended, with Madame du Châtelet, the nuptials in Monjeu, 150 miles southeast of Paris. Unlike many writers of our day, Voltaire could not keep the product of his pen out of print, and some surreptitious publications at this time caused an order for his arrest and the public burning of the book. The sacrifice of paper took place, but our ever wary author saved himself by flight, supposedly to Lorraine. At this time Voltaire and the philosophical Madame du Châtelet became greatly attached to each other, and their friendship lasted sixteen years. She lived in a thirteenth century castle at Cirey, in Champagne.

1736 —On his return to Cirey, he found awaiting him a long letter from Frederick of Prussia. A year or two before, Voltaire had received from the duke of Holstein, heir presumptive to the throne of Russia, husband of Catherine II., an invitation to reside in the Russian capital, on a revenue of 10,000 francs a year, which he declined. He was accustomed to the attention of princes and eulogiums from the gifted, but the letter of this Prussian prince had an especial importance and effect and opened a voluminous correspondence, ceasing only with the close of Voltaire’s life.

1740 —This was one of the most interesting years of his life. Frederick’s admiration for and devotion to him were at their height, while his fine sentences, so freely and so finely expressed, induced Voltaire to call him the modern Marcus Aurelius, and the Solomon of the North. Frederick made Voltaire his confidant; Voltaire was to him the most devoted teacher, philosopher and friend. The intercourse of these two men constitutes one of the most interesting episodes in history. Frederick William died May 31st, and Voltaire’s royal friend occupied the throne of Prussia. This fact promised to be of immense advantage to Voltaire.

For ten years a struggle existed between Frederick and Madame du Châtelet for a monopoly of Voltaire’s company. This rivalry was not conducive to his happiness.

1741–1742 —Voltaire and Frederick gradually became disenchanted with each other. There was no longer any intellectual sympathy between their strong individualities. Frederick, warlike and aggressive, shedding the blood and disturbing the peace of nations, was not the Frederick Voltaire admired, and he hesitated not to reprove the king frequently.

Among the Englishmen who visited him in Brussels was Lord Chesterfield, to whom he read his play, “Mahomet,” which was in May produced in Lille by a good French company, Voltaire and Madame du Châtelet being present. It was successful, but its production in Paris was delayed on account of a temporary disfavor in which Voltaire found himself with the Parisians, owing to his intimacy with the king of Prussia, now become the enemy of France. However, in August, 1742, it was produced in the Théâtre Français, to the most distinguished audience that Paris could furnish—the ministry, magistrates, clergy, d’Alembert, literary men, and the fashionable world, Voltaire being conspicuous in the middle of the pit. Its success was immense, but his old enemy, the Church, tireless as himself, found an excuse for censuring “Mahomet,” and within a week had it taken off the boards. Invited by Frederick, he went in September to Aix-la-Chapelle. There the king again tried to lure him to Prussia. Frederick offered him a handsome house in Berlin, a fine estate in the country, a princely income, and the free enjoyment of his time, all of which to have Voltaire near him; but Voltaire loved his native country, notwithstanding its persecutions, its Bastille, its suppression of his dramas, its Jansenists, Convulsionists, Desfontaines, and its frequent exiling of its most illustrious son; and he loved his friends and was faithful; and so, declining the king’s bounty, he went back to Paris. He devoted himself for a year to the production of plays, drilling the actors, subjecting every detail to the closest scrutiny, and creating successes that eclipsed even his own earlier efforts. It is said that the “Mérope” drowned the theatre in tears, and caused high excitement.

1745 —In January, Voltaire took up his abode in Versailles to superintend rehearsals, and in consideration of his labors at the fête, the king appointed him historiographer of France, on a yearly salary of 2,000 francs, and promised him the next vacant chair in the Academy. Voltaire considered this fair remuneration for a year of much toil in matters of the court. During these turbulent times, when a skilful pen was needed he was called upon. He was at this time in high favor with the king; Madame de Pompadour and many other influential persons also favored his aspirations. Voltaire dedicated “Mahomet” to the Pope, and sent a copy and a letter to him, out of which grew an interesting correspondence, the publication of which proclaimed his good standing with the head of the Church. He was elected to the Academy in 1746.

1747 —Private theatricals among the nobility were greatly in vogue at this time, and Madame de Pompadour selected Voltaire’s comedy, “The Prodigal,” to be played in the palace before the king. It was a striking success, and the author, in acknowledgment of the compliment, addressed a poem to Madame de Pompadour in which occurred an indiscreet allusion to her relations with the king. As a consequence, the king was induced to sign an order for his exile. This was followed by his hurried flight from court. At midnight, Voltaire, returning to his house in Fontainebleau, ordered the horses hitched to the carriage, and before daybreak left for Paris. He took refuge with the duchess du Maine in Sceaux.

1749 —Madame du Châtelet died under peculiar circumstances in August. Voltaire found solace in play-writing. He set up house in Paris, and invited his niece, Madame Denis, to manage for him, which she did for the remainder of his days, and thus at the age of fifty-six he had a suitable and becoming home in his native city, with an income of 74,000 francs a year, equal to about fifty thousand dollars to-day. Though it was considered fashionable in that age to have intrigues with women, there is no evidence to prove that it was not repugnant to Voltaire. He may at court have pretended to have been conventional in this respect, but his retired life with his niece, his years at Frederick’s court, and his more than fatherly treatment of his nieces. Corneille’s granddaughter, and other young women, show that he was a good man to women. He owned no land, his investments being almost wholly in bonds, mortgages, and annuities. His letters indicate that at this time he considered himself settled for life, his intention being, after spending the winter in Paris, to visit Frederick and Rome, making a tour of Italy, and then to return to Paris. But his reformatory writings were again bringing him into disfavor at court. He provided a theatre in his house, and invited a troupe of amateurs, amongst whom was the soon to be famous Lekain, to perform in it. This little theatre became famous. Voltaire worked like a Trojan, drilled the actors, supervised everything, and produced the most artistic effects. His work at this period included “Zadig,” “Babouc,” and “Memnon,” among his best burlesque romances.

1750 —The king of Prussia, on the death of his rival, renewed his solicitations that Voltaire should come to live with him. After his wars Frederick was again an industrious author, and Voltaire, submitting to his importunities, again went to him, leaving Madame Denis and Longchamp in charge of his house. He left Paris June 15th, and reached, July 10th, Sans-Souci, near Potsdam, the country place of the king, seventeen miles from Berlin. Here everybody courted him, and all that the king had was at his disposal. At a grand celebration in Berlin, Voltaire’s appearance caused more enthusiasm than did the king’s. Frederick was now thirty-eight years of age, had finished his first war and was devoting himself to making Berlin—a city of 90,000 people—attractive and famous. At his nightly concerts were Europe’s most famous artists. At his suppers were, besides Voltaire, many of the choice spirits of the literary world. Here, after thirty years of storms, Voltaire felt that he had found a port. Here was no Mirepoix to be despised and feared, no Bull Unigenitus, no offensive body of clergy and courtiers seeking fat preferment, no billets de confession, nor lettres de cachet, no Frérons to irritate authors, no cabals to damn a play, no more semblance of a king. Here for a time Voltaire was so happy that the long prospected trip to Italy was forgotten, but ere the year was out Paris, in the distance, to our Frenchman grew even more attractive and beautiful than before; several disagreeable things happened as a result of the decided attachment of Frederick for Voltaire,—jealousy and all forms of littleness ever present at court were repugnant to Voltaire. At this time he had an unhappy misunderstanding with Lessing, and in this and the following year he did much work on his “Age of Louis XIV.”

In November his propensity for speculation led him into the most deplorable lawsuit of his life. He supplied a Berlin jeweller named Abraham Hirsch with money and sent him to Dresden to buy depreciated banknotes at a large discount. Hirsch attended to his private business, it seems, and neglected Voltaire’s. He was recalled and the speculation abandoned; but the wily agent was not easily shaken off, as Voltaire found to his cost. Voltaire had a constitutional persistence that made it all but impossible for him to submit to imposition, and he fought in this case an antagonist as persistent as himself, and one utterly unscrupulous, so that after several months of litigation he indeed won his suit, but suffered much humiliation withal and greatly disgusted Frederick, who could not tolerate a lawsuit with a Jew.

1751 —During this year of trouble, he and the king for a time saw less of each other, and Voltaire found solace, as usual, in his literary labors. He studied German, published his “Age of Louis XIV.” in Berlin and in London. He co-operated with Diderot and d’Alembert on the great “Encyclopædia,” the first volume of which was prohibited in this year; and so, still toiling in a room adjoining the king’s in the château in Potsdam, this year glided into the next, in which the famous “Doctor Akakia” looms up.

1752 —In his brochure with this title Voltaire played with the great Maupertuis as a cat might with a mouse. The indulgence of his satirical tendencies endangered his friendship with the king, and in September a letter to Madame Denis revealed the fact that he was preparing to return to Paris. In November the king learned of the printed attack on his president of the Academy and was furious with Voltaire. An interesting correspondence followed, and partial reconciliation. The court and Voltaire went to Berlin for the Christmas festivities, but in this instance to separate houses. Here he had the honor of seeing several copies of his diatribe publicly burned on Sunday, December 24th, the result being that for some time ten German presses were printing the work day and night.

1753 —On New Year’s day Voltaire returned to the king as a New Year’s gift the cross of his order and his chamberlain’s key, together with a most respectful letter resigning his office and announcing his intended return to Paris. The king sent the insignia back and pressed Voltaire to stay, but in vain. After a sojourn in Leipsic, Voltaire paid a visit to the duchess of Saxe-Gotha, at Gotha. At her desire he undertook to write the “Annals of the Empire since Charlemagne.” In the evenings he delighted the brilliant company with reading his poems on “Natural Religion” and “La Pucelle.” Voltaire again irritated by his parting shots at Maupertius. An order was given, and carried out, by which Voltaire was arrested and detained at Frankfort while his boxes were searched for the cross and key, and the more important manuscript of verses by the king, entitled “Palladion,” in which his majesty had burlesqued the Christian faith. The king got his papers and chuckled over the humiliation of the man he had idolized, who took a poet’s revenge in this roughly paraphrased epigram on the great Frederick:

“Of incongruities a monstrous pile,

Calling men brothers, crushing them the while;

With air humane, a misanthropic brute;

Ofttimes impulsive, ofttimes too astute;

Weakest when angry, modest in his pride;

Yearning for virtue, lust personified;

Statesman and author, of the slippery crew;

My patron, pupil, persecutor too.”

In November of this year he visited his old friend, the duke de Richelieu, in Lyons, a city of great commercial importance about 200 miles from Colmar. Here he was enthusiastically welcomed by his few friends and the public, but the Church made it plain to him that he was not welcome to the governing class in France; so that, after a month in Lyons, he loaded his big carriage once more and sought an asylum in Geneva, ninety miles distant. He would have gone to America had he not feared the long sea journey, and in Switzerland he found the best possible European substitute for the new world of freedom so attractive to him.

1755 —In February Voltaire bought a life-lease of a commodious house, with beautiful gardens, on a splendid eminence overlooking Geneva, the lake and rivers; and giving an enchanting view of Jura and the Alps. This place he named “Les Délices,” the name it still bears. Here, he was in Geneva. Ten minutes’ walk placed him in Sardinia. He was only half an hour from France and one hour from the Swiss canton of Vaud. The situation pleased Voltaire, and he bought property and houses under four governments, and all within a circuit of a day’s ride. Voltaire describes his retreat thus: “I lean my left on Mount Jura, my right on the Alps, and I have the beautiful lake of Geneva in front of my camp, a beautiful castle on the borders of France, the hermitage of Délices in the territory of Geneva, a good house at Lausanne; crawling thus from one burrow to another, I escape from kings. Philosophers should always have two or three holes underground against the hounds that run them down.” From now until the end of his long life he lived like a feudal lord, a landed proprietor and an entertaining host. He kept horses, carriages, coachmen, postilions, lackeys, a valet, a French cook, a secretary and a boy, besides pet and domestic animals. Nearly every day he entertained at dinner from five to twenty friends.

1756 —On November 1st, All Saints’ Day, at 9:40 a. m., occurred the Lisbon earthquake, when half the people of that city were in church. In six minutes the city was in ruins and 30,000 people dead or dying. This was food for the thought of Europe and inspired one of Voltaire’s best poems. This was followed by “Candide,” the most celebrated of his prose burlesques, on Rousseau’s “best of all possible worlds,” and Dr. Johnson’s “Rasselas.” At this time the surreptitious publication of “La Pucelle” offended the French Calvinists of Geneva, and Voltaire thought it well in 1756 to go to Lausanne, where he inaugurated private theatricals in his own house. Here Gibbon had the pleasure of hearing a great poet declaim his own production on the stage. In this year his admirable Italian secretary, Collini, left him, and his place was filled by a Genevan named Wagnière, who continued to be his factotum for the remainder of his life. When scarcely three years in Geneva, Voltaire, finding the Genevans—who built their first theatre ten years later—averse to his theatrical performances, bought on French soil the estate of Ferney and built a theatre there.

1757–1758 —Voltaire never became indifferent to the disfavor in which he was held at the French court under the dominion of the Jesuits. Fortunately for him, he had for a friend the brilliant and powerful Pompadour, who at this time made him again safe on French soil, restored his pension and had his Ferney estate exempted from taxation. At this time, too, the “old Swiss,” as he was sometimes called, received an invitation from Elizabeth, empress of Russia, to come to St. Petersburg to write a history of her father, Peter the Great. Voltaire, now sixty-four, gladly undertook the work, but declining to go to St. Petersburg on account of his health, he had all necessary documents sent to Ferney. While Europe and America were ravaged by war, Voltaire worked industriously on his history, and yet amidst his labors his generous heart, consecrated to justice and humanity, moved him to splendid though unsuccessful efforts to save Admiral Byng from his persecutors. Again the king of Prussia seemed unable to forget Voltaire, and their correspondence was resumed. Voltaire hated carnage and cruelty, and begged Frederick, almost piteously, to end the war; but it continued, and the “Swiss Hermit” worked on in his retreat, never letting Europe forget his existence.

His outdoor occupations in Switzerland so improved his health that he resolved to become a farmer at his new place, the ancient estate of Ferney. He converted the old château into a substantial stone building of fourteen rooms. He improved the estate throughout, and made a life purchase of the adjacent seigniory of Tourney. He employed sixteen working oxen in his farming operations, established a breeding stable of ten mares at Les Délices, accepted a present of a fine stallion from the king’s stables, kept thirty men employed, and maintained on his estate more than sixty; and let it be remembered that not only did he make his estates beautiful, but he made them profitable. He had splendid barns, poultry-yards, and sheepfolds, winepresses, storerooms, and fruit-houses, about 500 beehives, and a colony of silkworms. He had a fine nursery and encouraged tree-planting. He formed a park, three miles in circuit, on the English model, around his house. Near the château he built a marble bath-house, supplied with hot and cold water. Everything that Voltaire wished for he had; from 1758 to 1764 he enjoyed good health and spirits and was never less involved in public affairs nor more prolific with his pen. Marmontel and Casanova wrote interestingly of their visits to Voltaire at this time. He finally wearied of the stream of people that visited him at Les Délices, and in 1765 sold it and spent all his time at the less easily reached Ferney.

1759 —In this year his “Natural Religion” was burned by the hangman in Paris. This infamy stirred Voltaire’s indignation greatly and impelled him to almost superhuman efforts against “L’Infâme,” the name with which he branded ecclesiasticism claiming supernatural authority and enforcing that claim with pains and penalties. His friends tried to dissuade him, but he had enlisted for the war and would not desert. Though as one against ten thousand, he knew no fear, and his watchword became Ecrasez l’Infâme.

1760 —In 1759 and 1760 appeared in Paris anonymous pamphlets by a well-known pen, in which the Jesuit Berthier and others were smothered in the most mirth-provoking ridicule. In this year he had also much dramatic success in Paris under the management of d’Argental. It was one of his most eventful years, and a rumor of his death having spread over Paris, in writing Madame du Deffand, he said: “I have never been less dead than I am at present. I have not a moment free; bullocks, cows, sheep, meadows, buildings, gardens, occupy me in the morning; all the afternoon is for study, and after supper we rehearse the pieces that are played in my little theatre.” This rumor occasioned the noble tribute of Goldsmith appended to this narrative.

1761 —The infamous outrage by the Church on the Calas family of Protestants in Toulouse is referred to by Voltaire in his work on “Toleration.” It stirred his indignation so powerfully that he devoted almost superhuman efforts to the duty of undoing the crime so far as possible.

1762–1763 —He undertook to have the Calas case reopened, and devoted himself to this task as if he had no other object or hope in life. He issued seven pamphlets on the case, had them translated and published in England and Germany. He stirred Europe up to help him. The queen of England, the archbishop of Canterbury, ten other English bishops, besides seventy-nine lords and forty-seven gentlemen, subscribed; also several German princes and nobles. The Swiss cantons, the empress of Russia, the king of Poland, and many other notables contributed money to assist Voltaire in this tremendous battle. It took him three years to win it, but on the 9th of March, 1765, he had the satisfaction of having the Calas family declared innocent and their property restored, amidst the applause of Europe. Voltaire went further, and had the king grant to each member of the family a considerable sum in cash, besides other benefits that he secured for them. Known as the savior of the Calas family, others in trouble went to him, till Ferney became a refuge for the distressed. Another celebrated case, that of the Sirven family, occurred in this year. Voltaire, learning of it in 1763, took up the cause of the oppressed as enthusiastically as in the Calas case. He wrote volumes in their behalf, and labored for nine years for the reversal of their sentence, giving and getting money as required. At length, in January, 1772, he was able to announce the complete success of his efforts on their behalf, and their complete vindication. These are but two of many such cases in which he interested himself. The horrors of French injustice at this time kept him constantly agitated and at work, and even induced him to attempt, in 1766, the forming of a colony of philosophers in a freer land. But failing to find philosophers inclined to self-expatriation, he dropped the idea.

1768 —On Easter Sunday he communed in his own church and addressed the congregation.

1769 —Again, on Easter of this year, the whim seized him to commune, as he lay in bed. At this time he was draining the swamp lands in the vicinity, lending money without interest to gentlemen, giving money to the poor, establishing schools, fertilizing lands, and maintaining over a hundred persons, defending the weak and persecuted, and playing jokes on the bishop, besides, after his sixtieth year, writing 160 publications. The difficulty of circulating his works can be imagined when it is remembered that he found it desirable to use 108 different pseudonyms. The Church watched all his manœuvres as a cat watches a mouse, yet he outwitted his enemies, and the eager public got the product of his great mind in spite of them.

1770 —By this time Ferney was becoming quite populous. Voltaire could not build houses quickly enough for those that flocked to his shelter. He fitted up his theatre as a watch-factory, and had watches for sale within six weeks. His friend, the duchess of Choiseul, wore the first silk stockings woven on the looms of Ferney. The grandest people bought his watches, and soon great material prosperity waited upon the industries of Ferney. Voltaire used all his prestige on behalf of his workmen, and so much was he liked that he could have had nearly all the skilled workmen of Geneva had he furnished houses for them. Catherine II. of Russia ordered a large quantity of his first product in watches. Voltaire, by his genius, literally forced Ferney’s products into the best markets of the world, so that within three years the watches, clocks, and jewelry from Ferney went regularly to Spain, Algiers, Italy, Russia, Holland, Turkey, Morocco, America, China, Portugal, and elsewhere. Voltaire was a city-builder and creator of trade. His charities were numerous and were bestowed without the odious flavor of pauperizing doles.

In this year, some of his friends proposed to erect a statue in his honor. Subscriptions came abundantly on the project being known, and the statue now is in the Institute of Paris. He was so overrun with visitors that he facetiously called himself the innkeeper of Europe. La Harpe, Cramer, Dr. Tronchin, Chabanon, Charles Pongens, Damilaville, d’Alembert, James Boswell, Charles James Fox, and Dr. Charles Burney were among his visitors.

1774 —On the death of Louis XV., he began to think again of Paris, to take a new interest in and lay plans for a visit to the city he loved so well; but the conditions seemed unfavorable, and the various labors and pleasures in Ferney continued.

1776 —In 1776 a large store-house was fitted up as a theatre and Lekain drew together in Ferney the nineteen cantons. In this year he adopted into his family a lovely girl of eighteen whom he called Belle-et-Bonne.

1777 —In this year he was still, at the age of eighty-three, an active, vigilant, and successful man of business, with ships on the Indian seas, with aristocratic debtors paying him interest, with the industrial “City of Ferney” earning immense revenues, with famous flocks, birds, bees, and silkworms, all receiving his daily attention. His yearly income at this time was more than 200,000 francs, and with nearly as much purchasing power then as the same number of dollars has with us to-day. In this year his pet, the sweet Belle-et-Bonne, was wooed and won by a gay marquis from Paris. Voltaire, though a bachelor, was fond of match-making, and was pleased in telling of the twenty-two marriages that had taken place on his estate of Ferney. The newly married pair remained in the château and they and Madame Denis conspired to induce him to go to Paris. They adduced a hundred reasons why he should go and these he as cleverly parried; but at length they prevailed and he consented to go for six weeks only.

1778 —On the 3d of February they started. The colonists and he were weeping. At the stopping-places on the way, in order to get away from the crowd of admirers that would press on him, he found it necessary to lock himself in his room. He made the 300 miles by February 10th, and put up at the hotel of Madame de Villette, after an exile of twenty-eight years! The city was electrified by the news and a tide of visitors set in, and crowds waited outside the hotel for a chance glimpse of the great man. He held a continuous reception and, amidst the tumult of homage, his gayety, tact, and humor never flagged. Among the first to do homage to Voltaire was Dr. Benjamin Franklin, with whom he conversed in English. With the American ambassador was his grandson, a youth of seventeen, upon whom Franklin asked the venerable philosopher’s benediction. Lifting his hands, Voltaire solemnly replied: “My child, God and Liberty, remember those two words.” He said to Franklin that he so admired the Constitution of the United States and the Articles of Confederation between them that, “if I were only forty years old, I would immediately go and settle in your happy country.” A medal was struck in honor of Washington, at Voltaire’s expense, bearing this couplet:

Washington réunit, par un rare assemblage,

Des talens du guerrier et des vertus du sage.

During the first two weeks several thousands of visitors called to welcome their great compatriot.

Voltaire busied himself with perfecting his new play, “Irène,” and rehearsing it prior to performance. On February 25th a fit of coughing caused a hæmorrhage. The doctors managed to save him for the grand event. The play was fixed for March 30th. The queen fitted up a box like her own, and adjoining it, for Voltaire. He attended a session of the Academy in the morning, where he was overwhelmed with honors, and elected president. His carriage with difficulty passed through the crowds that filled the streets, hoping to see him. On entering the theatre he thought to hide himself in his box, but the people insisted on his coming to the front. He had to submit, and then the actor Brizard entered the box, and in view of the people placed a laurel crown on his head. He modestly withdrew it, but all insisted on his wearing it, and he was compelled to let it be replaced. The scene was unparalleled for sustained enthusiasm. The excitement of these months proved fatal to the strong constitution which might easily have carried him through a century if he had remained at Ferney.

At 11:15 p. m., Saturday, May 30, 1778, aged 83 years, 6 months, and 9 days, he died peacefully and without pain. His body was embalmed and in the evening of June 1st was quietly buried in a near-by abbey, the place being indicated by a small stone, and the inscription: “Here lies Voltaire.”

The king of Prussia delivered before the Berlin Academy a splendid eulogium and compelled the Catholic clergy of Berlin to hold special services in honor of his friend. The empress Catherine wrote most kindly to Madame Denis and desired to buy his library of 6,210 volumes, and having done so, invited Wagnière to St. Petersburg to arrange the books as they were in Ferney. Crowned heads bowed to this great man, and the homage of his native Paris knew no bounds.

After thirteen years of rest, his body, by order of the king of France, was removed from the church of the Romilli to that of Sainte-Geneviève, in Paris, thenceforth known as the Panthéon of France. The magnificent cortège was the centre of the wildest enthusiasm. On July 10, 1791, the sarcophagus was borne as far as the site of the Bastille, not yet completely razed to the ground. Here it reposed for the night on an altar adorned with laurels and roses, and this inscription:

“Upon this spot, where despotism chained thee, Voltaire, receive the homage of a free people.”

A hundred thousand people were in the procession. At ten o’clock at night the remains were placed near the tombs of Descartes and Mirabeau. Here they reposed until 1814, when the bones of Voltaire and Rousseau were sacrilegiously stolen, with the connivance of the clerics, and burned with quicklime on a piece of waste ground. This miserable act of toothless spite was not publicly known until 1864.

OLIVER GOLDSMITH ON VOLTAIRE.

[This appeared as Letter XLIII. in the Chinese letters afterwards published under the title of “The Citizen of the World.”]

We have just received accounts here that Voltaire, the poet and philosopher of Europe, is dead. He is now beyond the reach of the thousand enemies who, while living, degraded his writings and branded his character. Scarce a page of his later productions that does not betray the agonies of a heart bleeding under the scourge of unmerited reproach. Happy, therefore, at last in escaping from calumny! happy in leaving a world that was unworthy of him and his writings!

Let others bestrew the hearses of the great with panegyric; but such a loss as the world has now suffered affects me with stronger emotions. When a philosopher dies I consider myself as losing a patron, an instructor, and a friend. I consider the world as losing one who might serve to console her amidst the desolations of war and ambition. Nature every day produces in abundance men capable of filling all the requisite duties of authority; but she is niggard in the birth of an exalted mind, scarcely producing in a century a single genius to bless and enlighten a degenerate age. Prodigal in the production of kings, governors, mandarins, chams, and courtiers, she seems to have forgotten, for more than three thousand years, the manner in which she once formed the brain of a Confucius; and well it is she has forgotten, when a bad world gave him so very bad a reception.

Whence, my friend, this malevolence, which has ever pursued the great, even to the tomb? whence this more than fiendlike disposition of embittering the lives of those who would make us more wise and more happy?

When I cast my eye over the fates of several philosophers, who have at different periods enlightened mankind, I must confess it inspires me with the most degrading reflections on humanity. When I read of the stripes of Mencius, the tortures of Tchin, the bowl of Socrates, and the bath of Seneca; when I hear of the persecutions of Dante, the imprisonment of Galileo, the indignities suffered by Montaigne, the banishment of Descartes, the infamy of Bacon, and that even Locke himself escaped not without reproach; when I think on such subjects, I hesitate whether most of blame the ignorance or the villainy of my fellow-creatures.

Should you look for the character of Voltaire among the journalists and illiterate writers of the age, you will there find him characterized as a monster, with a head turned to wisdom and a heart inclining to vice; the powers of his mind and the baseness of his principles forming a detestable contrast. But seek for his character among writers like himself, and you find him very differently described. You perceive him, in their accounts, possessed of good nature, humanity, greatness of soul, fortitude, and almost every virtue; in this description those who might be supposed best acquainted with his character are unanimous. The royal Prussian, d’Argens, Diderot, d’Alembert, and Fontenelle, conspire in drawing the picture, in describing the friend of man, and the patron of every rising genius.

An inflexible perseverance in what he thought was right and a generous detestation of flattery formed the groundwork of this great man’s character. From these principles many strong virtues and few faults arose; as he was warm in his friendship and severe in his resentment, all that mention him seem possessed of the same qualities, and speak of him with rapture or detestation. A person of his eminence can have few indifferent as to his character; every reader must be an enemy or an admirer.

This poet began the course of glory so early as the age of eighteen, and even then was author of a tragedy which deserves applause. Possessed of a small patrimony, he preserved his independence in an age of venality; and supported the dignity of learning by teaching his contemporary writers to live like him, above the favors of the great. He was banished his native country for a satire upon the royal concubine. He had accepted the place of historian to the French king, but refused to keep it when he found it was presented only in order that he should be the first flatterer of the state.

The great Prussian received him as an ornament to his kingdom, and had sense enough to value his friendship and profit by his instructions. In this court he continued till an intrigue, with which the world seems hitherto unacquainted, obliged him to quit that country. His own happiness, the happiness of the monarch, of his sister, of a part of the court, rendered his departure necessary.

Tired at length of courts and all the follies of the great, he retired to Switzerland, a country of liberty, where he enjoyed tranquillity and the muse. Here, though without any taste for magnificence himself, he usually entertained at his table the learned and polite of Europe, who were attracted by a desire of seeing a person from whom they had received so much satisfaction. The entertainment was conducted with the utmost elegance, and the conversation was that of philosophers. Every country that at once united liberty and science were his peculiar favorites. The being an Englishman was to him a character that claimed admiration and respect.

Between Voltaire and the disciples of Confucius there are many differences; however, being of a different opinion does not in the least diminish my esteem; I am not displeased with my brother because he happens to ask our Father for favors in a different manner from me. Let his errors rest in peace; his excellencies deserve admiration; let me with the wise admire his wisdom; let the envious and the ignorant ridicule his foibles; the folly of others is ever most ridiculous to those who are themselves most foolish.—Adieu.

[Goldsmith began a memoir of Voltaire which he did not live to finish, from which we take this most interesting picture of Voltaire among his friends.]

Some disappointments of this kind served to turn our poet from a passion which only tended to obstruct his advancement in more exalted pursuits. His mind, which at that time was pretty well balanced between pleasure and philosophy, quickly began to incline to the latter. He now thirsted after a more comprehensive knowledge of mankind than either books or his own country could possibly bestow.

England about this time was coming into repute throughout Europe as the land of philosophers. Newton, Locke, and others began to attract the attention of the curious, and drew hither a concourse of learned men from every part of Europe. Not our learning alone, but our politics also began to be regarded with admiration; a government in which subordination and liberty were blended in such just proportions was now generally studied as the finest model of civil society. This was an inducement sufficient to make Voltaire pay a visit to this land of philosophers and of liberty.

Accordingly, in the year 1726, he came over to England. A previous acquaintance with Atterbury, bishop of Rochester, and the Lord Bolingbroke, was sufficient to introduce him among the polite, and his fame as a poet got him the acquaintance of the learned in a country where foreigners generally find but a cool reception. He only wanted introduction; his own merit was enough to procure the rest. As a companion, no man ever exceeded him when he pleased to lead the conversation; which, however, was not always the case. In company which he either disliked or despised, few could be more reserved than he; but when he was warmed in discourse and had got over a hesitating manner which sometimes he was subject to, it was rapture to hear him. His meagre visage seemed insensibly to gather beauty; every muscle in it had meaning, and his eye beamed with unusual brightness. The person who writes this memoir, who had the honor and the pleasure of being his acquaintance, remembers to have seen him in a select company of wits of both sexes at Paris, when the subject happened to turn upon English taste and learning. Fontenelle, who was of the party, and who, being unacquainted with the language or authors of the country he undertook to condemn, with a spirit truly vulgar began to revile both. Diderot, who liked the English and knew something of their literary pretensions, attempted to vindicate their poetry and learning, but with unequal abilities. The company quickly perceived that Fontenelle was superior in the dispute, and were surprised at the silence which Voltaire had preserved all the former part of the night, particularly as the conversation happened to turn upon one of his favorite topics. Fontenelle continued his triumph till about 12 o’clock, when Voltaire appeared at last roused from his reverie. His whole frame seemed animated. He began his defence with the utmost elegance mixed with spirit, and now and then let fall the finest strokes of raillery upon his antagonist; and his harangue lasted till three in the morning. I must confess, that, whether from national partiality, or from the elegant sensibility of his manner, I never was so much charmed, nor did I ever remember so absolute a victory as he gained in this dispute.

[Another biographer, writing early in the nineteenth century, offers a judicial summary of Voltaire’s character, from which we select a few passages.]

This simple recital of the incidents of the life of Voltaire has sufficiently developed his character and his mind; the principal features of which were benevolence, indulgence for human foibles, and a hatred of injustice and oppression. He may be numbered among the very few men in whom the love of humanity was a real passion; which, the noblest of all passions, was known only to modern times, and took rise from the progress of knowledge. Its very existence is sufficient to confound the blind partisans of antiquity, and those who calumniate philosophy.

But the happy qualities of Voltaire were often perverted by his natural restlessness, which the writing of tragedy had but increased. In an instant he would change from anger to affection, from indignation to a jest. Born with violent passions, they often hurried him too far; and his restlessness deprived him of the advantages that usually accompany such minds; particularly of that fortitude to which fear is no obstacle when action becomes a duty, and which is not shaken by the presence of danger foreseen. Often would Voltaire expose himself to the storm with rashness, but rarely did he brave it with constancy; and these intervals of temerity and weakness have frequently afflicted his friends and afforded unworthy cause of triumph to his cowardly foes. In weighing the peccadilloes of any man due consideration must be had for the period in which he lived, and of the nature of the society amidst which he was reared. Voltaire was in his twentieth year when Louis XIV. died, and consequently his very precocious adolescence was spent during the reign of that pompous and celebrated actor of majesty. How that season was characterized as to morals and the tone of Parisian good company, an epitome of the private life of Louis himself will tell. The decorum and air of state with which Louis sinned was rather edifying than scandalous, and his subjects faithfully copied the grand monarch. Gallantry became the order of the day throughout France, with a great abatement of the chivalrous sentiment that attended it under the regency of Anne of Austria, but still exempt from the more gross sensuality that succeeded Louis under the regency of the duke of Orleans.

It has been observed that Voltaire was altogether a Frenchman, and the remark will be found just, whether applied to the character of the man or the genius. By increasing to intensity the national characteristics, social, constitutional and mental, we create a Voltaire. These are gayety, facility, address, a tendency to wit, raillery, and equivoque; light, quick, and spontaneous feelings of humanity, which may be occasionally worked up into enthusiasm; vanity, irascibility, very slipshod morality in respect to points that grave people are apt to deem of the first consequence; social insincerity, and a predominant spirit of intrigue. Such were the generalities of the French character in the days of Voltaire; and multiply them by his capacity and acquirement, and we get at the solid contents of his own. It is, therefore, especially inconsistent to discover such excellence and virtue in the old French régime, and especially in the reign of Louis XIV., and to find so much fault with the tout ensemble of Voltaire; for both his good and his bad qualities were the natural outgrowth of the period.

The most detestable and odious of all political sins is, indisputably, religious persecution; in this is to be traced the source of the early predisposition of Voltaire, and of the honorable enthusiasm that colored nearly the whole of his long life. By accident, carelessness, or indifference, he was very early allowed to imbibe a large portion of philosophical skepticism, which no after education—and he was subsequently educated by Jesuits—could remove. What was more natural for a brilliant, ardent, and vivacious young man, thus ardently vaccinated—if the figure be allowable—against the smallpox of fanaticism and superstition so prevalent in this country, and born during a reign that revoked the Edict of Nantes, and expatriated half a million of peaceful subjects? In what way did his most Christian majesty, the magnificent Louis, signalize that part of his kingly career which immediately preceded the birth of Voltaire? In the famous dragonnades, in which a rude and licentious soldiery were encouraged in every excess of cruelty and outrage, because, to use the language of the minister Louvois, “His majesty was desirous that the heaviest penalties should be put in force against those who are not willing to embrace his religion; and those who have the false glory to remain longest firm in their opinions, must be driven to the last extremities.”

They were so driven. It will therefore suffice to repeat that at length the Edict of Nantes was formally repealed, Protestants refused liberty of conscience, their temples demolished, their children torn from them, and, to crown all, attempts were even made to impede their emigration. They were to be enclosed like wild beasts and hunted down at leisure.

Such were the facts and horrors that must, in the first instance, have encountered and confirmed the incipient skepticism of Voltaire. What calm man, of any or of no religion, can now hear of them without shuddering and execration? and what such feel now it is reasonable to suppose that a mind predisposed like that of Voltaire must have felt then.

Next to fanaticism and superstition, Voltaire appears to have endeavored with the utmost anxiety to rectify the injustice of the public tribunals, especially in the provinces, which were in the habit of committing legal murders with a facility that could only be equalled by the impunity. Against the execrable tyranny of lettres de cachet, by which he himself suffered more than once, he occasionally dated his powerful innuendoes. No matter what the religious opinions of Voltaire were, he uniformly inculcates political moderation, religious tolerance, and general good-will.

Looking, therefore, at the general labors of this premier genius of France for the benefit of his fellow-creatures, he must, at all events, be regarded as a bold, active, and able philanthropist, even by those who in many respects disagree with him.

As a philosopher, he was the first to afford an example of a private citizen who, by his wishes and his endeavors, embraced the general history of man in every country and in every age, opposing error and oppression of every kind, and defending and promulgating every useful truth. The history of whatever has been done in Europe in favor of reason and humanity is the history of his labor and beneficent acts. If the liberty of the press be increased; if the Catholic clergy have lost their dangerous power, and have been deprived of some of their most scandalous wealth; if the love of humanity be now the common language of all governments; if the continent of Europe has been taught that men possess a right to the use of reason; if religious prejudices have been eradicated from the higher classes of society, and in part effaced from the hearts of the common people; if we have beheld the masks stripped from the faces of those religious sectaries who were privileged to impose on the world; and if reason, for the first time, has begun to shed its clear and uniform light over all Europe—we shall everywhere discover, in the history of the changes that have been effected, the name of Voltaire.

victor hugo on voltaire.

[Oration delivered at Paris, May 30, 1878, the one hundredth anniversary of Voltaire’s death.]

A hundred years ago to-day a man died. He died immortal. He departed laden with years, laden with works, laden with the most illustrious and the most fearful of responsibilities, the responsibility of the human conscience informed and rectified. He went cursed and blessed, cursed by the past, blessed by the future; and these, gentlemen, are the two superb forms of glory. On his death-bed he had, on the one hand, the acclaim of contemporaries and of posterity; on the other, that triumph of hooting and of hate which the implacable past bestows upon those who have combated it. He was more than a man; he was an age. He had exercised a function and fulfilled a mission. He had been evidently chosen for the work which he had done, by the Supreme Will, which manifests itself as visibly in the laws of destiny as in the laws of nature.

The eighty-four years that this man lived occupy the interval that separates the monarchy at its apogee from the revolution in its dawn. When he was born, Louis XIV. still reigned; when he died, Louis XVI. reigned already; so that his cradle could see the last rays of the great throne, and his coffin the first gleams from the great abyss.

Before going further, let us come to an understanding, gentlemen, upon the word abyss. There are good abysses; such are the abysses in which evil is engulfed.

Gentlemen, since I have interrupted myself, allow me to complete my thought. No word imprudent or unsound will be pronounced here. We are here to perform an act of civilization. We are here to make affirmation of progress, to pay respect to philosophers for the benefits of philosophy, to bring to the eighteenth century the testimony of the nineteenth, to honor magnanimous combatants and good servants, to felicitate the noble effort of peoples, industry, science, the valiant march in advance, the toil to cement human concord; in one word, to glorify peace, that sublime, universal desire. Peace is the virtue of civilization; war is its crime. We are here, at this grand moment, in this solemn hour, to bow religiously before the moral law, and to say to the world, which hears France, this: There is only one power, conscience, in the service of justice; and there is only one glory, genius, in the service of truth. That said, I continue:

Before the Revolution, gentlemen, the social structure was this:

At the base, the people;

Above the people, religion represented by the clergy;

By the side of religion, justice represented by the magistracy.

And, at that period of human society, what was the people? It was ignorance. What was religion? It was intolerance. And what was justice? It was injustice. Am I going too far in my words? Judge.

I will confine myself to the citation of two facts, but decisive ones.

At Toulouse, October 13, 1761, there was found in a lower story of a house a young man hanged. The crowd gathered, the clergy fulminated, the magistracy investigated. It was a suicide; they made of it an assassination. In what interest? In the interest of religion. And who was accused? The father. He was a Huguenot, and he wished to hinder his son from becoming a Catholic. There was here a moral monstrosity and a material impossibility; no matter! This father had killed his son; this old man had hanged this young man. Justice travailed, and this was the result. In the month of March, 1762, a man with white hair, Jean Calas, was conducted to a public place, stripped naked, stretched on a wheel, the members bound on it, the head hanging. Three men are there upon a scaffold; a magistrate, named David, charged to superintend the punishment, a priest to hold the crucifix, and the executioner with a bar of iron in his hand. The patient, stupefied and terrible, regards not the priest, and looks at the executioner. The executioner lifts the bar of iron, and breaks one of his arms. The victim groans and swoons. The magistrate comes forward; they make the condemned inhale salts; he returns to life. Then another stroke of the bar; another groan. Calas loses consciousness; they revive him, and the executioner begins again; and, as each limb before being broken in two places receives two blows, that makes eight punishments. After the eighth swooning the priest offers him the crucifix to kiss; Calas turns away his head, and the executioner gives him the coup de grâce; that is to say, crushes in his chest with the thick end of the bar of iron. So died Jean Calas.

That lasted two hours. After his death the evidence of the suicide came to light. But an assassination had been committed. By whom? By the judges.