Images of Liberty and power: The Art of War and Peace

[Created: 7 Nov. 2010]

[Updated: January 31, 2023 ] |

This is part of a collection of works of art and other images I have used in my teaching or have commented upon over the years. They are roughly divided into two groups, those that deal with "Art and Politics" (on another page) and those with the "Art of War and Peace" (this page)

Recent Additions

From my current blog:

- “David Hart’s “ABC of ANZAC History” (6 Jan. 2022)

- "Picasso and the Anti-Vietnam War Movement 1969" (12 July, 2015)

- "Pablo Picasso’s “Guernica” (1937)" (25 June, 2015)

- "Ernst Friedrich’s “War against War” (1924)" (23 July, 2014)

From my old blog:

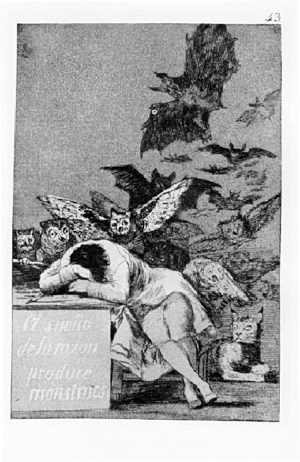

Goya, "The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters" |

Picasso, "Guernica" (1937) [What happens when Reason sleeps] |

|

A new lecture on War & Peace in the Work of Pablo Picasso: "Guernica" (1937). An essay on "War and Peace in the Visual Arts" [HTML draft] and [2.3 MB PDF final version] Some study guides on individual artists which were used in my course "Responses to War: An Intellectual and Cultural History":

|

Some books about war with images:

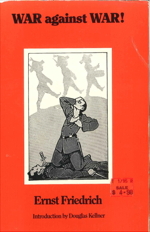

- Ernst Friedrich, Krieg dem Kriege! Guerre a la Guerre! War against War! Oorlog aan den Oorlog! (Berlin: "Freie Jugend", (1924).

- Otto Dix, Der Krieg (The War) (Berlin: Otto Felsing, Karl Nierendorf, 1924). [a collection of his drawings]

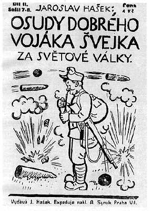

- A complete collection of the illustrations by Josef Lada for the novel by the Czech author Jaroslav Hašek, The Good Soldier Švejk and his Fortunes in the World War (1923).

Ernst Friedrich, War against War! (1924)

|

Title: Ernst Friedrich, Krieg dem Kriege! Guerre a la Guerre! War against War! Oorlog aan den Oorlog! (Berlin: "Freie Jugend", (1924). Comment: I have not been able to find the orignal book but I do own an edition from 1987 and there are copies of many of the images on the web. I have put together a representative sample of his collection of shocking photographs showing death and destruction in WW1 along with his scathing comments. [Warning: some of these photos as truly shocking. But then, so is modern war.] Guillaumin Collection: War & Peace |

Otto Dix, Der Krieg (1924)

|

Title: Otto Dix, Der Krieg (The War) (Berlin: Otto Felsing, Karl Nierendorf, 1924). Comment: Dix saw service in WW1 and documented his experiences in a collection of drawings which he published in 1924. I have reconstructed the original order of the drawings as they appeared in his 1924 book which were divided into five folios. If they seem a bit extreme they should be seen alongside Ernst Friedrich's collection of photographs in War against War! also published in 1924. Guillaumin Collection: War & Peace |

Jaroslav Hašek/Josef Lada, The Good Soldier Švejk (1923)

|

Title: A complete collection of the illustrations by Josef Lada for the novel by the Czech author Jaroslav Hašek, The Good Soldier Švejk and his Fortunes in the World War (1923). Comment: The Czech anarchist Hašek served in the Austrian Army during WW1 but deserted to join the Red Army after the Bolshevik Revolution broke out. Not finding that army to his liking either, he deserted again. He created the character Švejk after the war and planned several volumes of his exploits. These consisted in trying to avoid as much miilitary duty as possible, usually by literally carrying out the orders his superiors gave him and thus screwing them up. The illustrations are charming but disguise a very serious argument being made in the book about the nature of authority and how individuals can cope in an impossible situation. [This is a work in progress given the sheer number of illustrations.] Guillaumin Collection: War & Peace |

Some "Illustrated Essays" at this website (the first link is to the brief description below, the second to [more] - to the essay proper):

- “Peace and Liberty: The Dove of Peace across the Centuries. The seal of the Magistrates of the Ten of Liberty and Peace of the City of Florence (c. early 1500s)” (November 12, 2010) - [more]

- “Animal Imagery of War & Peace: James Montgomery Flagg, "Side-by-Side - Britannia" (1918)” (November 13, 2010) - [more]

- “What Daddy did in the War: British Recruiting Poster (WW1)” (November 17, 2010) - [more]

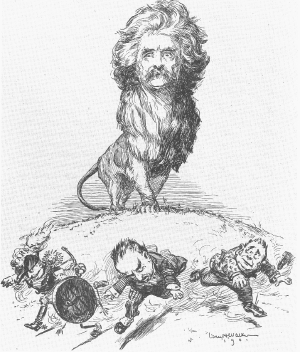

- “Patriotic Songs which invoke God ("God is on our side”): A cartoon in *Life*, Feb. 1901 of Mark Twain as "The American Lion of St. Marks" scattering the American imperialists” (January 15, 2011) - [more]

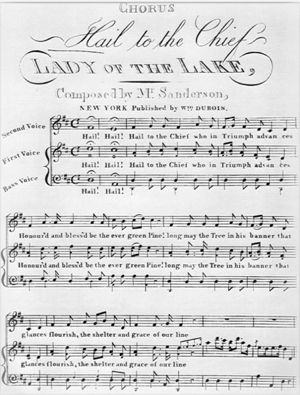

- "Hail to the Chief" (1810/1812): The sheet music for "Hail to the Chief" using Sir Walter Scott's original words from the poem The Lady of the Lake (1810) (January 25, 2011) - [more]

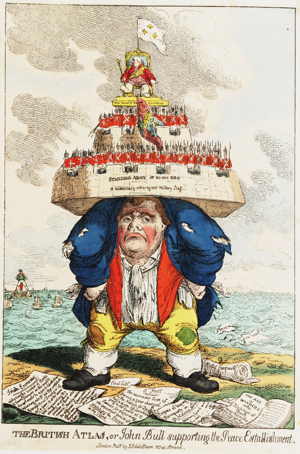

- "The British Atlas, or John Bull supporting the Peace Establishment" (1816) [James Gillray or C. Williams] (May 27, 2011) - [more]

- Abel Gance, "J'Accuse" [I Accuse] (1938) and Remembrance Day 11.11.11 (November 11, 2011) - [more]

- “Puck magazine’s Ridiculing the Anti-Imperialist League’s Opposition to the Conquest of the Philippines” (July 15, 2012) - [more]

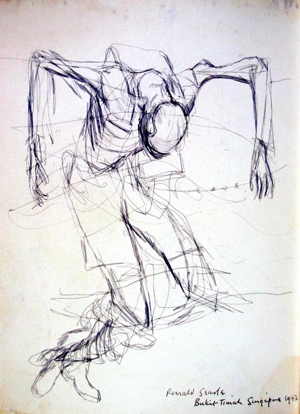

- “War and Violence in the Work of Ronald Searle (1920-2011)” (January 05, 2012) [more]

- “The Art of the ANZAC Book (1916)” (1 July, 2012) - [more]

Peace and Liberty: The Dove of Peace across the Centuries

|

In early 16th century Florence, when Niccolo Machiavelli was working as a diplomat for the city state, the seal of the Magistrates of the Ten of Liberty and Peace was an image of a dove holding an olive branch in its beak with the following Latin motto "Pax et Defencio Libertatis" (Peace and the Defence of Liberty). The link between "peace and liberty" is thus one that goes back several centuries at least. [more] Left: The seal of the Magistrates of the Ten of Liberty and Peace of the City of Florence (c. early 1500s) |

Animal Imagery of War & Peace

|

Another flag is James Montgomery Flagg who is best known for his WW1 recruiting posters for the U.S. army - such as Uncle Sam pointing menacingly at the viewer stating "I want you for the U.S. Army". This poster is unusual because it depicts Uncle Sam and Britannia arm in arm immediately after the ending of WW1. It was done for a public meeting so Americans could congratulate the British Empire on "winning" the war against the German Empire. Note that Sam and Britannia are standing on a small rock in the middle of the ocean (which was dominated by the victorious British Navy); Britannia is wearing a Roman helmet and holding a trident pointing upwards, while Sam is wearing some striking striped red trousers and has his sword pointing downwards (at this time still the junior partner it seems); the British lion is striding towards the viewer and the American eagle is flapping its wings perhaps in preparation for taking off.. [more] Left: James Montgomery Flagg, "Side-by-Side - Britannia" (1918) |

What Daddy did in the War

|

The young girl sitting on her father's lap asks a very important question, the answer to which seems to be troubling her father. This is a British recruiting poster from WW1 which was designed to inspire guilt in those men who had not yet volunteered to enlist to fight against the "Hun". The poster asks the male viewer (probably not married and without children) to imagine life after the war when his future children will no doubt ask him this very pertinent question. She has been reading what seems to be a history book about the "Great War" with diagrams of fortifications or trenches and, with her finger carefully placed on a specific picture, wants her father to explain exactly what he did and where he did it. The father (who hadn't enlisted) can't answer her question. Would the young adult male viewer of this poster want to be in the same difficult situation a few years hence?. [more] Left: British Recruiting Poster (WW1) |

Patriotic Songs which invoke God ("God is on our side")

|

In 1901 Mark Twain had become increasingly critical of the American invasion of the Philippines (a Catholic nation under the Spanish). What had been touted as a "war of liberation" of the Philippine people had turned quickly into a standard European-style conquest of a would-be colony with Protestant American boys killing Catholic Philippino resistance fighters leaving hundreds of thousands dead. So he felt it was time to update Howe's patriotic song with some new lyrics better suited to the new century. Note his condemnation of the Americans as "faithless son(s) of Freedom" and that he retains some of the original, namely the refrain "Our god is marching on" (admittedly in lower not upper case this time around). Twain's reworking of the hymn should be compared to his equally devastating "The War Prayer" (1905) in which he shows that the opposite side of the coin to praying to God for swift and glorious victory for one side is the eqaully swift though inglorious death and suffering of the defeated enemy. Praying for victory for oneself implies praying for the death and suffering for others - but this is never mentioned in polite company. [more] Left: A cartoon in Life, Feb. 1901 of Mark Twain as "The American Lion of St. Marks" scattering the American imperialists. In the same month MT wrote an "updated" version of the "Battle Hymn of the Republic" to take into account the American war in the Philippines. (1901) |

"Hail to the Chief" (1810/1812)

|

What is most notable at first reading is the obvious militry references to the President as "chief" and "commander" whom we must "salute" unanimously ("one and all"). There is no mention about upholding the Constitution or carrying out duly enacted laws. Instead there is a "pledge" to "make this grand country grander", which could mean economically bigger and better, but this seems unlikely as it is expressed in the context of "hailing" the president as "commander" in chief of the armed forces (the word "grander" is deliberately chosen in order to rhyme with "commander"). The fact that the music is played now almost exclusively by military bands reinforces this "militaristic" reading of the song. [more] Left: The sheet music for "Hail to the Chief" using Sir Walter Scott's original words from the poem The Lady of the Lake (1810) |

John Bull, the British Atlas

|

John Bull is standing on a green island surrounded by water in which can be seen some naval vessels and another figure standing on another island off in the distance. His blue jacket is torn and ripped and his yellow trousers have been patched on the knees. On his back is a three-tiered "castle" atop which sits the King and 2 layers of armed soldiers which are labelled "Standing Army of 150,000 Men, a numerous extravagant Military Staff". The King's throne sit on top of a pedestal which says "The Cause of the Bourbons" referring to Britain's role in restoring the French Bourbon monarchy to power after the defeat of Napoleon Out of JB's pockets and on the ground at his feet are "Unpaid Bills" and in the water behind him is a torn piece of paper on which is written "Property Tax". His right foot is placed on a document entitled the "Irish Economy" and which reads "reducing the number of Clerks and Commissioners in the public departments to a peace Establishment by turning adrift all the wretched and necessitous Drudges of 50L a year and at the same time augmenting the already enormous salaries of those who remain, thereby rendering the different Government offices more burthensome and expensive than they were in time of War." JB's right heel is on top of a document entitled "Civil List." The document between his feet states "A Fact. The enormous sum of 10,000 pounds a year charged to the Nation for Dining (?) half a dozen Officers belonging to the Guard at St. James's for performing the important service of Watching the Crows in the Park." To the right of this is a document which says "Expence of keeping Bonaparte in St. Helena 3000,000 pounds. Military Guard …" To the far right is a book ("Just Published!") entitled "The Age of Wonders! or the Blessings of Peace, more destructive to the English than the horrors of War." [more] Left: "The British Atlas, or John Bull supporting the Peace Establishment" (1816) [James Gillray or C. Williams] |

Remembrance Day 11.11.11

|

||

In this still from Abel Gance's movie J'Accuse [I Accuse] (1938) we see the statue on the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier at Verdun coming to life in response to the calls of the embittered anti-war scientist Jean Diaz for all the fallen soldiers of the First World War to rise up and protest the outbreak of another war. Abel Gance first made the film in 1919 using 2,000 French soldiers who were on leave from the front to depict the uprising of the dead. He made a second version in 1938 when it was clear another war was soon to break out in Europe (which it did in Septmber 1939 when the Nazis invaded Poland). The message was that even though millions had died in vain fighting for State and Empire in the first war, by returning from the dead they might stop a second war in which further millions would die. A noble but furitless hope in 1938-39. [See the clips of the last 20 minutes of the film when the fallen soldiers rise up to literally frighten the people into dropping their weapons - Part 1 - Part 2 - Part 3] Here is the controversial depiction of a dead soldier on the Royal Artillery Monument in Hyde Park, London. It was designed by Charles Sargeant Jagger and was unveiled in 1925 to commemorate the members of the Royal Regiment of Artillery who died in WW1. There are 4 statues of soldiers around the monument one of whom is shown dead, wrapped in his trench coat with his helmet resting on his chest. Sargeant defied a government ban on the depiction of dead soldiers in the war in his attempt to show the men in a more realist light. Around the base is a patriotic quotation from Shakespeare's Henry V which says "Here was a royal fellowship of death!" [at the OLL]. This is a very strange quotation to have selected for a monument to the ordinary men in the regiment of artillery who died in the war. Henry V makes his remark about getting a report of the battle field dead after the battle of Agincourt. He only gets a list of the aristocrats and his royal relatives who died on the battle field. No mention s made of the ardinary English soldiers and archers who also died in Henry's ultimately failed attempt to expand his empire in France. Ordinary solioders in his mind had no names and were completely expendable [Note this is the name of John Ford's very sad film about US navy men in WW2 - "They Were Expendable" (1945). The picture of the dead soldier at the Royal Artillery Monument is used in the opening shot of Joseph Losey's film "King and Country" (1964)].

Hundreds of thousands of French and German soliders died fighting around the citadel of Verdun. Many of their bodies were either lost in the mud or completely unidentifiable. This photo is of one of the crypts at the Ossuary at Douaumont (Verdun) where the bones of unknown soliders are kept. This of course is another example of "the fellowship of death" but rather less "royal" than Henry V had in mind.

Contrast Gance's parade of the dead and deformed and the Ossuary at Verdun with the line from Horace's poem in which he states the opposite sentiment - "dulce et decorum est pro patria mori" [It is sweet and fitting to die for the Fatherland]. One might read Horace's original poem as somewhat ironic and mocking but the sentiment was taken very seriously for generations of schoolboys who learnt Latin in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. For many young men who marched off to fight in August 1914 this was a sentiment they had absorbed at school and believed fervently. Not surprisingly it was one of the ideas which Erich Maria Remarque singled out for criticism in the novel and later film All Quiet on the Western Front (1930) [see the film clip] and which the English poet Wilfred Owen called "the old lie". One might dismiss this patriotic nonsense of the Victorian and Edwardian eras as no longer relevannt to modern society but one would be mistaken. Here is that same slogan urging the ultimate sacrifice on behalf of the state and empire engraved above the entrance to the Arlington Memorial Amphitheater in Washington, D.C. Do the people gathered underneath the entrance even know what it says or what it means? Would they care if they did?

[See a larger version of the top image to read the line from Horace's poem] [Read more about this topic] |

Ridiculing the Anti-Imperialist League’s Opposition to the Conquest of the Philippines

|

The secartoons were published in the satirical magazine Puck (1871-1918) founded by Joseph Keppler in St. Louis but which later moved to New York city. Generally, it supported the so-called "Bourbon Democrats" associated with Grover Cleveland (elected President 1884, 1888, 1892) and could be described as the classical liberal branch of the Democratic Party, supporting laissez-faire economic policies and the gold standard and opposing tariffs and overseas expansion and imperialism. Unfortunately Puck magazine broke with the Bourbon Democrats over the question of American expansion during the Spanish-American War and published many pro-expansion cartoons between 1898 and 1905. The anti-imperialist cause was taken up by a group of older politicians and intellectuals who saw expansionism as a violation of the principles of the American Constitution and individual liberty. The formation of the Anti-Imperialist League in June 1898 brought together individuals such as the following: Charles Francis Adams, Jr., Jane Addams, Edward Atkinson, Ambrose Bierce, George S. Boutwell, Andrew Carnegie, Samuel Clemens (Mark Twain), Grover Cleveland, John Dewey, Edwin Lawrence Godkin, William Dean Howells, Henry James, William James, David Starr Jordan, Carl Schurz, Moorfield Storey, William Graham Sumner, and Oswald Garrison Villard. Puck magazine singled out Edward Atkinson, Edwin Lawrence Godkin, Carl Schurz, and Grover Cleveland for particular attention. [more] Left: "Columbia's Easter Bonnet" Puck magazine (1901). |

War and Violence in the Work of Ronald Searle (1920-2011)

|

The English cartoonist and illustrator Ronald Searle died on 31 December 2011. He is unfortunately best remembered for his drawings about the fictional British public school for girls "St. Trinians" which he conceived while a captive of the Japanese during WW2. He regretted the fame and typecasting which came from this early success and moved to Paris then the south of France in order to concentrate on his book illustrations and cartoons. His collection of eyewitness drawings of life in Changi Prison in Singapore and the work camps of the notorious Thai-Burma railway is extraordinary. He secretly documented his experiences and hid them from his guards by placing them under the mattresses of soldiers who were dying from cholera. The brutality and disregard for human life which he experienced first hand led him to ask himself the question - "could this happen to people in my home country, or is this something peculiar to the Japanese people and their culture?" His answer seems to be that it is a universal phenomenon. His stroke of genius was to imagine a typical English private school for girls where the girls behaved in a violent manner towards their peers and their teachers. Behind the apparently humorous hijinks of the girls was a darker view of human nature in which violence, torture, and moral collapse was the order of the day. Searle did his first cartoons of the girls of St. Trinians while he was a prisoner and sold them to magazines upon his return to civilian life. They subsequently appeared in books and then as films and made him a fortune. [more] Left: "Dead man on a barbed wire fence" (Singapore 1942). |

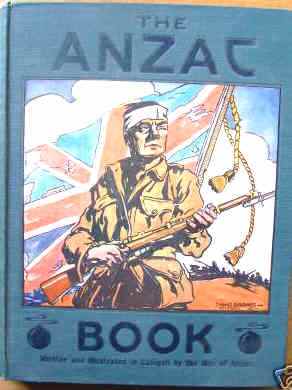

The Art of the ANZAC Book (1916): The Alphabetization of War

|

The book was compiled in late November in order explicitly to raise money for the war effort but with the additional, unstated goal of telling the world about how the ANZACs had coped in battle. It contains material by both officers and men, including C.E.W. Bean who is listed as one of the editors. He later went on to write a famous official history of Australian involvement in WW1 and helped establish the "ANZAC myth" in Australian history. Some of the material expresses frustration and even anger at some of the things that the enlisted men had to endure but this is rather muffled as I'm sure military censorship would have been very much in the back of their minds, as well as a fear of "letting down" their families back home. Publication was delayed because while the book was being edited the troops learned of plans to withdraw them early in the new year. This, in some respects the ANZAC Book became a farewell from the troops after enduring 9 months of fruitless combat. [more] Left: Title page of The ANZAC Book (1916). |