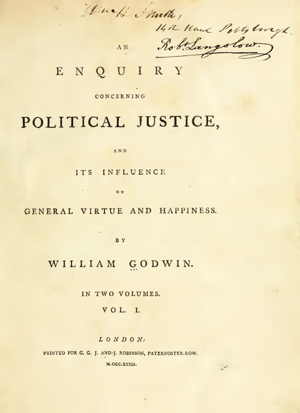

William Godwin, An Enquiry Concerning Political Justice (1793)

|

|

| William Godwin (1756-1836) |

[Created: 10 Jan. 2021]

[Updated: April 30, 2023 ] |

The Guillaumin Collection

|

This title is part of “The Guillaumin Collection” within “The Digital Library of Liberty and Power”. It has been more richly coded and has some features which other titles in the library do not have, such as the original page numbers, formatting which makes it look as much like the original text as possible, and a citation tool which makes it possible for scholars to link to an individual paragraph which is of interest to them. These titles are also available in a variety of eBook formats for reading on portable devices. |

Source

, An Enquiry Concerning Political Justice, and its Influence on General Virtue and Happiness (London: G.G.J. and J. Robinson, 1793). 2 vols.http://davidmhart.com/liberty/EnglishClassicalLiberals/Godwin/1793-PoliticalJustice/index.html

This title is also available in a facsimile PDF of the original and various eBook formats.

This book is part of a collection of works by William Godwin (1756-1836).

Table of Contents

[I-xiv]

CONTENTS OF THE FIRST BOOK. OF THE IMPORTANCE OF POLITICAL INSTITUTIONS.

- CHAP. I. INTRODUCTION. The subject proposed.—System of indifference—of passive obedience—of liberty.—System of liberty extended. Page 1

- CHAP. II. HISTORY OF POLITICAL SOCIETY. Frequency of war—among the ancients—among the moderns—the French—the English.—Causes of war.—Penal laws.—Despotism.—Deduction.—Enumeration of arguments. Page 5

- CHAP. III. THE MORAL CHARACTERS OF MEN ORIGINATE IN THEIR PERCEPTIONS. No innate principles.—Objections to this assertion—from the early actions of infants—from the desire of self-preservation—from self-love—from pity—from the vices of children—tyranny—sullenness.—Conclusion. Page 13

- CHAP. IV. THREE PRINCIPAL CAUSES OF MORAL IMPROVEMENT CONSIDERED.

- I. LITERATURE. Benefits of literature.—Examples.—Essential properties of literature.—Its defects.

- II. EDUCATION. Benefits of education.—Causes of its imbecility.

- III. POLITICAL JUSTICE. Benefits of political institution.—Universality of its influence—proved by the mistakes of society.—Origin of evil. Page 19

- CHAP. V. INFLUENCE OF POLITICAL INSTITUTIONS EXEMPLIFIED. Robbery and fraud, two great vices in society—originate, 1. in extreme poverty—2. in the ostentation of the rich—3. in their tyranny—rendered permanent—1. by legislation—2. by the administration of law—3. by the inequality of conditions. Page 33

- CHAP. VI. HUMAN INVENTIONS CAPABLE OF PERPETUAL IMPROVEMENT. Perfectibility of man—instanced, first, in language.—Its beginnings.—Abstraction.—Complexity of language.—Second instance: alphabetical writing.—Hieroglyphics at first universal.—Progressive deviations.—Application. Page 43

- CHAP. VII. OF THE OBJECTION TO THESE PRINCIPLES FROM THE INFLUENCE OF CLIMATE.

- PART I. OF MORAL AND PHYSICAL CAUSES. The question stated.—Provinces of sensation and reflection.—Moral causes frequently mistaken for physical.—Superiority of the former evident from the varieties of human character.—Operation of physical causes rare.—Fertility of reflection.—Physical causes in the first instance superior, afterwards moral.—Objection from the effect of breed in animals.—Conclusion. Page 51

- PART II. OF NATIONAL CHARACTERS. Character of the priesthood.—All nations capable of liberty.—The assertion illustrated.—Experience favours these reasonings.—Means of introducing liberty. Page 60

- CHAP. VIII. OF THE OBJECTION TO THESE PRINCIPLES FROM THE INFLUENCE OF LUXURY. The objection stated.—Source of this objection.—Refuted from mutability—from mortality—from the nature of truth.—The probability of perseverance considered. Page 71

BOOK II. PRINCIPLES OF SOCIETY.

- CHAP. I. INTRODUCTION. Nature of the enquiry.—Mode of pursuing it.—Distinction between society and government. Page 77

- CHAP. II. OF JUSTICE. Connection of politics and morals.—Extent and meaning of justice.—Subject of justice: mankind.—Its distribution measured by the capacity of its subject—by his usefulness.—Family affection considered.—Gratitude considered.—Objections: from ignorance—from utility.—An exception stated.—Degrees of justice.—Application.—Idea of political justice. Page 80

- APPENDIX, No. I. of suicide. Motives of suicide: 1. escape from pain—2. benevolence.—Martyrdom considered. Page 92

- APPENDIX, No. II. of duelling. Motives of duelling: 1. revenge—2. reputation for courage.—Fallacy of this motive.—Objection answered.—Illustration. Page 94

- CHAP. III. OF DUTY. A difficulty stated.—Of absolute and practical virtue.—Impropriety of this distinction.—Universality of what is called practical virtue—instanced in robbery—in religious fanaticism.—The quality of an action distinct from the disposition with which it is performed.—Farther difficulty.—Meaning of the term, duty.—Application.—Inferences. Page 97

- CHAP. IV. OF THE EQUALITY OF MANKIND. Physical equality.—Objection.—Answers.—Moral equality.—How limited.—Province of political justice. Page 104

- CHAP. V. RIGHTS OF MAN. The question stated.—Foundation of society.—Opposite rights impossible.—Conclusion from these premises.—Discretion considered.—Rights of kings.—Immoral consequences of the doctrine of rights.—Rights of communities.—Objections: 1. the right of mutual aid.—Explanation.—Origin of the term, right.—2. rights of private judgment and of the press.—Explanation.—Reasons of this limitation upon the functions of the community: 1. the inutility of attempting restraint—2. its pernicious tendency.—Conclusion. Page 109

- CHAP. VI. OF THE EXERCISE OF PRIVATE JUDGMENT. Foundation of virtue.—Human actions regulated: 1. by the nature of things—2. by positive institution.—Tendency of the latter: 1. to excite virtue.—Its equivocal character in this respect.—2. to inform the judgment.—Its inaptitude for that purpose.—Province of conscience considered.—Tendency of an interference with that province.—Recapitulation.—Arguments in favour of positive institution: 1. the necessity of repelling private injustice.—Objections: the uncertainty of evidence—the diversity of motives—the unsuitableness of the means of correction—either to impress new sentiments—or to strengthen old ones.—Punishment for the sake of example considered.—Urgency of the case.—2. rebellion—3. war.—Objections.—Reply. Page 120

BOOK III. PRINCIPLES OF GOVERNMENT.

- CHAP. I. SYSTEMS OF POLITICAL WRITERS. The question stated.—First hypothesis: government founded in superior strength.—Second hypothesis: government jure divino.—Third hypothesis: the social contract.—The first hypothesis examined.—The second.—Criterion of divine right: 1. patriarchal descent—2. justice. Page 139

- CHAP. II. OF THE SOCIAL CONTRACT. Queries proposed.—Who are the contracting parties?—What is the form of engagement?—Over how long a period does the contract extend?—To how great a variety of propositions?—Can it extend to laws hereafter to be made?—Addresses of adhesion considered.—Power of a majority. Page 143

- CHAP. III. OF PROMISES. The validity of promises examined.—Shown to be inconsistent with justice—to be foreign to the general good.—Of the expectation excited.—The fulfilling expectation does not imply the validity of a promise.—Conclusion. Page 150

- CHAP. IV. OF POLITICAL AUTHORITY. Common deliberation the true foundation of government—proved from the equal claims of mankind—from the nature of our faculties—from the object of government—from the effects of common deliberation.—Delegation vindicated.—Difference between the doctrine here maintained and that of a social contract apparent—from the merely prospective nature of the former—from the nullity of promises—from the fallibility of deliberation.—Conclusion. Page 157

- CHAP. V. OF LEGISLATION. Society can declare and interpret, but cannot enact.—Its authority only executive. Page 166

- CHAP. VI. OF OBEDIENCE. Obedience not the correlative of authority.—No man bound to yield obedience to another.—Case of submission considered.—Foundation of obedience.—Usefulness of social communication.—Case of confidence considered.—Its limitations.—Mischief of unlimited confidence.—Subjection explained. Page 168

- APPENDIX. Moral principles frequently elucidated by incidental reflection—by incidental passages in various authors.—Example. Page 176

- CHAP. VII. OF FORMS OF GOVERNMENT. Argument in favour of a variety of forms—compared with the argument in favour of a variety of religious creeds.—That there is one best form of government proved—from the unity of truth—from the nature of man.—Objection from human weakness and prejudice.—Danger in establishing an imperfect code.—Manners of nations produced by their forms of government.—Gradual improvement necessary.—Simplicity chiefly to be desired.—Publication of truth the grand instrument—by individuals, not by government—the truth entire, and not by parcels.—Sort of progress to be desired. Page 179

BOOK IV. MISCELLANEOUS PRINCIPLES.

- CHAP. I. OF RESISTANCE. Every individual the judge of his own resistance.—Objection.—Answered from the nature of government—from the modes of resistance.—1. Force rarely to be employed—either where there is small prospect of success—or where the prospect is great.—History of Charles the first estimated.—2. Reasoning the legitimate mode. Page 191

- CHAP. II. OF REVOLUTIONS.

- SECTION I. DUTIES OF A CITIZEN. Obligation to support the constitution of our country considered—must arise either from the reason of the case, or from a personal and local consideration.—The first examined.—The second. Page 198

- SECTION II. MODE OF EFFECTING REVOLUTIONS. Persuasion the proper instrument—not violence—nor resentment.—Lateness of event desirable. Page 202

- SECTION III. OF POLITICAL ASSOCIATIONS. Meaning of the term.—Associations objected to—1. From the sort of persons with whom a just revolution should originate—2. from the danger of tumult.—Objects of association.—In what cases admissible.—Argued for from the necessity to give weight to opinion—from their tendency to ascertain opinion.—Unnecessary for these purposes.—General inutility.—Concessions.—Importance of social communication.—Propriety of teaching resistance considered. Page 205

- SECTION IV. OF THE SPECIES OF REFORM TO BE DESIRED. Ought it to be partial or entire?—Truth may not be partially taught.—Partial reformation considered.—Objection.—Answer.—Partial reform indispensible.—Nature of a just revolution—how distant? Page 219

- CHAP. III. OF TYRANNICIDE. Diversity of opinions on this subject.—Argument in its vindication.—The destruction of a tyrant not a case of exception.—Consequences of tyrannicide.—Assassination described.—Importance of sincerity. Page 226

- CHAP. IV. OF THE CULTIVATION OF TRUTH.

- SECTION I. OF ABSTRACT OR GENERAL TRUTH. Its importance as conducing—to our intellectual improvement—to our moral improvement.—Virtue the best source of happiness.—Proved by comparison—by its manner of adapting itself to all situations—by its undecaying excellence—cannot be effectually propagated but by a cultivated mind.—Importance of general truth to our political improvement. Page 231

- SECTION II. OF SINCERITY. Nature of this virtue.—Its effects—upon our own actions—upon our neighbours.—Its tendency to produce fortitude.—Effects of insincerity.—Character which sincerity would acquire to him who practised it.—Objections.—The fear of giving unnecessary pain.—Answer.—The desire of preserving my life.—This objection proves too much.—Answer.—Secrecy considered.—The secrets of others.—State secrets.—Secrets of philanthropy. Page 238

- APPENDIX, No. I. OF THE CONNEXION BETWEEN UNDERSTANDING AND VIRTUE.

- Can eminent virtue exist unconnected with talents?—Nature of virtue.—It is the offspring of understanding.—It generates understanding.—Illustration from other pursuits—love—ambition—applied.

- Can eminent talents exist unconnected with virtue?—Argument in the affirmative from analogy—in the negative from the universality of moral speculation—from the nature of vice as founded in mistake.—The argument balanced.—Importance of a sense of justice.—Its connexion with talents.—Illiberality with which men of talents are usually treated. Page 253

- APPENDIX, No. II, OF THE MODE OF EXCLUDING VISITORS. Its impropriety argued—from the situation in which it places, 1. the visitor—2. the servant.—Objections:—Pretended necessity of this practice, 1. to preserve us from intrusion—2. to free us from disagreeable acquaintance.—Characters of the honest and dishonest man in this respect compared. Page 265

- APPENDIX, No. III, SUBJECT OF SINCERITY RESUMED. A case proposed.—Arguments in favour of concealment.—Previous question: Is truth in general to be partially communicated?—Customary effects of sincerity—of insincerity—upon him who practises it—1. the suspension of improvement—2. misanthropy—3. disingenuity—upon the spectators.—Sincerity delineated.—Its general importance.—Application.—Duty respecting the choice of a residence. Page 272

- CHAP. V. OF FREE WILL AND NECESSITY. Importance of the question.—Definition of necessity.—Why supposed to exist in the operations of the material universe.—The case of the operations of mind is parallel.—Indications of necessity—in history—in our judgments of character—in our schemes of policy—in our ideas of moral discipline.—Objection from the fallibility of our expectations in human conduct.—Answer.—Origin and universality of the sentiment of free will.—The sentiment of necessity also universal.—The truth of this sentiment argued from the nature of volition.—Hypothesis of free will examined.—Self-determination.—Indifference.—The will not a distinct faculty.—Free will disadvantageous to its possessor—of no service to morality. Page 283

- CHAP. VI. INFERENCES FROM THE DOCTRINE OF NECESSITY. Idea it suggests to us of the universe.—Influence on our moral ideas—action—virtue—exertion—persuasion—exhortation—ardour—complacence and aversion—punishment—repentance—praise and blame—intellectual tranquillity.—Language of necessity recommended. Page 305

- CHAP. VII. OF THE MECHANISM OF THE HUMAN MIND. Nature of mechanism.—Its classes, material and intellectual.—Material system, or of vibrations.—The intellectual system most probable—from the consideration that thought would otherwise be a superfluity—from the established principles of reasoning from effects to causes.—Objections refuted.—Thoughts which produce animal motion may be—1. Involuntary.—All animal motions were first involuntary.—2. Unattended with consciousness.—The mind cannot have more than one thought at any one time.—Objection to this assertion from the case of complex ideas—from various mental operations—as comparison—apprehension—rapidity of the succession of ideas.—Application.—Duration measured by consciousness.—3. A distinct thought to each motion may be unnecessary—apparent from the complexity of sensible impressions.—The mind always thinks.—Conclusion.—The theory applied to the phenomenon of walking—to the circulation of the blood.—Of motion in general.—Of dreams. Page 318

- CHAP. VIII. OF THE PRINCIPLE OF VIRTUE. Hypotheses of benevolence and self love—superiority of the former.—Action is either voluntary or involuntary.—Nature of the first of these classes.—Argument that results from it.—Voluntary action has a real existence.—Consequence of that existence.—Experimental view of the subject.—Suppositions suggested by the advocates of self love—that we calculate upon all occasions the advantage to accrue to us.—Falseness of this supposition.—Supposition of a contrary sort.—We do not calculate what would be the uneasiness to result from our refraining to act—either in relieving distress—or in adding to the stock of general good.—Uneasiness an accidental member of the process.—The suppositions inconsistently blended.—Scheme of self love recommended from the propensity of mind to abbreviate its process—from the simplicity that obtains in the natures of things.—Hypothesis of self love incompatible with virtue.—Conclusion.—Importance of the question.—Application. Page 341

- CHAP. IX. OF THE TENDENCY OF VIRTUE. It is the road to happiness—to the esteem and affection of others.—Objection from misconstruction and calumny.—Answer.—Virtue compared with other modes of procuring esteem.—Vice and not virtue is the subject of obloquy—instanced in the base alloy with which our virtues are mixed—in arrogance and ostentation—in the vices in which persons of moral excellence allow themselves.—The virtuous man only has friends.—Virtue the road to prosperity and success in the world—applied to commercial transactions—to cases that depend upon patronage.—Apparent exceptions where the dependent is employed as the instrument of vice.—Virtue compared with other modes of becoming prosperous.—Source of the disrepute of virtue in this respect.—Concession.—Case where convenient vice bids fair for concealment.—Chance of detection.—Indolence—apprehensiveness—and depravity the offspring of vice. Page 362

[II-ii]

CONTENTS OF THE SECOND VOLUME.

- BOOK V. OF LEGISLATIVE AND EXECUTIVE POWER.

- BOOK VI. OF OPINION CONSIDERED AS A SUBJECT OF POLITICAL INSTITUTION.

- BOOK VII. OF CRIMES AND PUNISHMENTS.

- BOOK VIII. OF PROPERTY.

CONTENTS OF THE FIFTH BOOK. OF LEGISLATIVE AND EXECUTIVE POWER.

- CHAP. I. INTRODUCTION. RETROSPECT of principles already established. — Distribution of the remaining subjects. — Subject of the present book. — Forms of government. — Method of examination to be adopted. p. 379

- CHAP. II. OF EDUCATION, THE EDUCATION OF A PRINCE. Nature of monarchy delineated. — School of adversity. — Tendency of superfluity to inspire effeminacy — to deprive us of the benefit of experience. — Illustrated in the case of princes. — Manner in which they are addressed. — Inefficacy of the instruction bestowed upon them. p. 383

- CHAP. III. PRIVATE LIFE OF A PRINCE. Principles by which he is influenced — irresponsibility — impatience of control — habits of dissipation — ignorance — dislike of truth — dislike of justice. — Pitiable situation of princes. p. 397

- CHAP. IV. OF A VIRTUOUS DESPOTISM. Supposed excellence of this form of government controverted — from the narrowness of human powers. — Case of a vicious administration — of a virtuous administration intended to be formed. — Monarchy not adapted to the government of large states. p. 408

- CHAP. V. OF COURTS AND MINISTERS. Systematical monopoly of confidence. — Character of ministers — of their dependents. — Venality of courts. — Universality of this principle. p. 414

- CHAP. VI. OF SUBJECTS. Monarchy founded in imposture. — Kings not entitled to superiority — inadequate to the functions they possess. — Means by which the imposture is maintained — 1. splendour — 2. exaggeration. — This imposture generates — 1. indifference to merit — 2. indifference to truth — 3. artificial desires — 4. pusillanimity. — Moral incredulity of monarchical countries. — Injustice of luxury — of the inordinate admiration of wealth. p. 423

- CHAP. VII. OF ELECTIVE MONARCHY. Disorders attendant on such an election. — Election is intended either to provide a man of great or of moderate talents. — Consequences of the first — of the second. — Can elective and hereditary monarchy be combined? p. 435

- CHAP. VIII. OF LIMITED MONARCHY. Liable to most of the preceding objections — to farther objections peculiar to itself. — Responsibility considered. — Maxim, that the king can do no wrong. — Functions of a limited monarch. — Impossibility of maintaining the neutrality required. — Of the dismission of ministers. — Responsibility of ministers — Appointment of ministers, its importance — its difficulties. — Recapitulation. — Strength and weakness of the human species. p. 441

- CHAP. IX. OF A PRESIDENT WITH REGAL POWERS. Enumeration of powers — that of appointing to inferior offices — of pardoning offences — of convoking deliberative assemblies — of affixing a veto to their decrees. — Conclusion. — The title of king estimated. — Monarchical and aristocratical systems, similarity of their effects. p. 454

- CHAP. X. OF HEREDITARY DISTINCTION. Birth considered as a physical cause — as a moral cause. — Aristocratical estimate of the human species. — Education of the great. — Recapitulation. p. 461

- CHAP. XI. MORAL EFFECTS OF ARISTOCRACY. Importance of practical justice. — Species of injustice which aristocracy creates. — Estimate of the injury produced. — Examples. p. 468

- CHAP. XII. OF TITLES. Their origin and history. — Their miserable absurdity. — Truth the only adequate reward of merit. p. 474

- CHAP. XIII. OF THE ARISTOCRATICAL CHARACTER. Intolerance of aristocracy — dependent for its success upon the ignorance of the multitude. — Precautions necessary for its support. — Different kinds of aristocracy. — Aristocracy of the Romans: its virtues — its vices. — Aristocratical distribution of property — regulations by which it is maintained — avarice it engenders. — Argument against innovation from the present happy establishment of affairs considered. — Conclusion. p. 478

- CHAP. XIV. GENERAL FEATURES OF DEMOCRACY. Definition. — Supposed evils of this form of government — ascendancy of the ignorant — of the crafty — inconstancy — rash confidence — groundless suspicion. — Merits and defects of democracy compared. — Its moral tendency. — Tendency of truth. — Representation. p. 489

- CHAP. XV. OF POLITICAL IMPOSTURE. Importance of this topic. — Example in the doctrine of eternal punishment. — Its inutility argued — from history — from the nature of mind. — Second example: the religious sanction of a legislative system. — This idea is, 1. in strict construction impracticable — 2. injurious. — Third example: principle of political order. — Vice has no essential advantage over virtue. — Imposture unnecessary to the cause of justice — not adapted to the nature of man. p. 499

- CHAP. XVI. OF THE CAUSES OF WAR. Offensive war contrary to the nature of democracy. — Defensive war exceedingly rare. — Erroneousness of the ideas commonly annexed to the phrase, our country. — Nature of war delineated. — Insufficient causes of war — the acquiring a healthful and vigorous tone to the public mind — the putting a termination upon private insults — the menaces or preparations of our neighbours — the dangerous consequences of concession. — Two legitimate causes of war. p. 511

- CHAP. XVII. OF THE OBJECT OF WAR. The repelling an invader. — Not reformation — not restraint — not indemnification. — Nothing can be a sufficient object of war that is not a sufficient cause for beginning it. — Reflections on the balance of power. p. 521

- CHAP. XVIII. OF THE CONDUCT OF WAR. Offensive operations. — Fortifications. — General action. — Stratagem. — Military contributions. Capture of mercantile vessels. — Naval war. — Humanity. — Military obedience. — Foreign possessions. p. 526

- CHAP. XIX. OF MILITARY ESTABLISHMENTS AND TREATIES. A country may look for its defence either to a standing army or an universal militia. — The former condemned. — The latter objected to as of immoral tendency — as unnecessary — either in respect to courage — or discipline. — Of a commander. — Of treaties. p. 534

- CHAP. XX. OF DEMOCRACY AS CONNECTED WITH THE TRANSACTIONS OF WAR. External affairs are of subordinate consideration. — Application. — Farther objections to democracy — 1. it is incompatible with secrecy — this proved to be an excellence — 2. its movements are too slow — 3. too precipitate. — Evils of anarchy considered. p. 542

- CHAP. XXI. OF THE COMPOSITION OF GOVERNMENT. Houses of assembly. — This institution unjust. — Deliberate proceeding the proper antidote. — Separation of legislative and executive power considered. — Superior importance of the latter. — Functions of ministers. p. 550

- CHAP. XXII. OF THE FUTURE HISTORY OF POLITICAL SOCIETIES. Quantity of administration necessary to be maintained. — Objects of administration: national glory — rivalship of nations. — Inferences: 1. complication of government unnecessary — 2. extensive territory superfluous — 3. constraint, its limitations. — Project of government: police — defence. p. 558

- CHAP. XXIII. OF NATIONAL ASSEMBLIES. They produce a fictitious unanimity — an unnatural uniformity of opinion. — Causes of this uniformity — Consequences of the mode of decision by vote — 1. perversion of reason — 2. contentious disputes — 3. the triumph of ignorance and vice. — Society incapable of acting from itself — of being well conducted by others. Conclusion. — Modification of democracy that results from these considerations. p. 568

- CHAP. XXIV. OF THE DISSOLUTION OF GOVERNMENT. Political authority of a national assembly — of juries. — Consequence from the whole. p. 576

BOOK VI. OF OPINION CONSIDERED AS A SUBJECT OF POLITICAL INSTITUTION.

- CHAP. I. GENERAL EFFECTS OF THE POLITICAL SUPERINTENDENCE OF OPINION. Arguments in favour of this superintendence. — Answer. — The exertions of society in its corporate capacity are, 1. unwise — 2. incapable of proper effect. — Of sumptuary laws, agrarian laws and rewards. — Political degeneracy not incurable. — 3. superfluous — in commerce — in speculative enquiry — in morality. — 4. pernicious — as undermining intellectual capacity — as suspending intellectual improvement — contrary to the nature of morality — to the nature of mind. — Conclusion. p. 581

- CHAP. II. OF RELIGIOUS ESTABLISHMENTS. Their general tendency. — Effects on the clergy: they introduce, 1. implicit faith — 2. hypocrisy: topics by which an adherence to them is vindicated. — Effects on the laity. — Application. p. 603

- CHAP. III. OF THE SUPPRESSION OF ERRONEOUS OPINION IN RELIGION AND GOVERNMENT. Of heresy. — Arguments by which the suppression of heresy is recommended. — Answer. — Ignorance not necessary to make men virtuous. — Difference of opinion not subversive of public security. — Reason, and not force, the proper corrective of sophistry. — Absurdity of the attempt to restrain thought — to restrain the freedom of speech. — Consequences that would result. — Fallibility of the men by whom authority is exercised. — Of erroneous opinions in government. — Iniquity of the attempt to restrain them. — Tendency of unlimited political discussion. p. 610

- CHAP. IV. OF TESTS. Their supposed advantages are attended with injustice — are nugatory. — Illustration. — Their disadvantages — they ensnare — example — second example — they are an usurpation. — Influence of tests on the latitudinarian — on the purist. — Conclusion. p. 622

- CHAP. V. OF OATHS. Oaths of office and duty. — Their absurdity. — Their immoral consequences. — Oaths of evidence less atrocious. — Opinion of the liberal and resolved respecting them. — Their essential features: contempt of veracity — false morality. — Their particular structure. — Abstract principles assumed by them to be true. — Their inconsistency with these principles. p. 631

- CHAP. VI. OF LIBELS. Public libels. — Injustice of an attempt to prescribe the method in which public questions shall be discussed. — Its pusillanimity. — Invitations to tumult. — Private libels. — Reasons in favour of their being subjected to restraint. — Answer. — 1. It is necessary the truth should be told. — Salutary effects of the unrestrained investigation of character. — Objection: freedom of speech would be productive of calumny, not of justice. — Answer. — Future history of libel. — 2. It is necessary men should be taught to be sincere. — Extent of the evil which arises from a command to be insincere. — The mind spontaneously shrinks from the prosecution of a libel. — Conclusion. p. 637

- CHAP. VII. OF CONSTITUTIONS. Distinction of regulations constituent and legislative. — Supposed character of permanence that ought to be given to the former — inconsistent with the nature of man. — Source of the error. — Remark. — Absurdity of the system of permanence. — Its futility. — Mode to be pursued in framing a constitution. — Constituent laws not more important than others. — In what manner the consent of the districts is to be declared. — Tendency of the principle which requires this consent. — It would reduce the number of constitutional articles — parcel out the legislative power — and produce the gradual extinction of law. — Objection. — Answer. p. 652

- CHAP. VIII. OF NATIONAL EDUCATION. Arguments in its favour. — Answer. — 1. It produces permanence of opinion. — Nature of prejudice and judgment described. — 2. It requires uniformity of operation. — 3. It is the mirror and tool of national government. — The right of punishing not founded in the previous function of instructing. p. 665

- CHAP. IX. OF PENSIONS AND SALARIES. Reasons by which they are vindicated. — Labour in its usual acceptation and labour for the public compared. — Immoral effects of the institution of salaries. — Source from which they are derived. — Unnecessary for the subsistence of the public functionary — for dignity. Salaries of inferior officers — may also be superseded. — Taxation. — Qualifications. p. 673

- CHAP. X. OF THE MODES OF DECIDING A QUESTION ON THE PART OF THE COMMUNITY. Decision by lot, its origin — founded in the system of discretionary rights — implies the desertion of duty. — Decision by ballot — inculcates timidity — and hypocrisy. — Decision by vote, its recommendations. p. 683

BOOK VII. OF CRIMES AND PUNISHMENTS.

- CHAP. I. LIMITATIONS OF THE DOCTRINE OF PUNISHMENT WHICH RESULT FROM THE PRINCIPLES OF MORALITY. Definition of punishment. — Nature of crime. — Retributive justice not independent and absolute — not to be vindicated from the system of nature. — Desert a chimerical property. — Conclusion. p. 687

- CHAP. II. GENERAL DISADVANTAGES OF COERCION. Conscience in matters of religion considered — in the conduct of life. — Best practicable criterion of duty — not the decision of other men — but of our own understanding. — Tendency of coercion. — Its various classes considered. p. 696

- CHAP. III. OF THE PURPOSES OF COERCION. Nature of defence considered. — Coercion for restraint — for reformation. — Supposed uses of adversity — defective — unnecessary. — Coercion for example — 1. nugatory. — The necessity of political coercion arises from the defects of political institution. — 2. unjust. — Unfeeling character of this species of coercion. p. 705

- CHAP. IV. OF THE APPLICATION OF COERCION. Delinquency and coercion incommensurable. — External action no proper subject of criminal animadversion. — How far capable of proof. — Iniquity of this standard in a moral — and in a political view. — Propriety of a retribution to be measured by the intention of the offender considered. — Such a project would overturn criminal law — would abolish coercion. — Inscrutability, 1. of motives. — Doubtfulness of history. — Declarations of sufferers. — 2. of the future conduct of the offender — uncertainty of evidence — either of the facts — or the intention. — Disadvantages of the defendant in a criminal suit. p. 715

- CHAP. V. OF COERCION CONSIDERED AS A TEMPORARY EXPEDIENT. Arguments in its favour. — Answer. — It cannot fit men for a better order of society. — The true remedy to private injustice described — is adapted to immediate practice. — Duty of the community in this respect. — Duty of individuals. — Illustration from the case of war — of individual defence. — Application. — Disadvantages of anarchy — want of security — of progressive enquiry. — Correspondent disadvantages of despotism. — Anarchy awakens, despotism depresses the mind. — Final result of anarchy — how determined. — Supposed purposes of coercion in a temporary view — reformation — example — restraint. — Conclusion. p. 727

- CHAP. VI. SCALE OF COERCION. Its sphere described. — Its several classes. — Death with torture. — Death absolutely. — Origin of this policy — in the corruptness of political institutions — in the inhumanity of the institutors. — Corporal punishment. — Its absurdity. — Its atrociousness. — Privation of freedom. — Duty of reforming our neighbour an inferior consideration in this case. — Its place defined. — Modes of restraint. — Indiscriminate imprisonment. — Solitary imprisonment. — Its severity. — Its moral effects. — Slavery. — Banishment. — 1. Simple banishment. — 2. Transportation. — 3. Colonisation. — This project has miscarried from unkindness — from officiousness. — Its permanent evils. — Recapitulation. p. 745

- CHAP. VII. OF EVIDENCE. Difficulties to which this subject is liable — exemplified in the distinction between overt actions and intentions. — Reasons against this distinction. — Principle in which it is founded. p. 760

- CHAP. VIII. OF LAW. Arguments by which it is recommended. — Answer. — Law is, 1. Endless — particularly in a free state. — Causes of this disadvantage. — 2. Uncertain. — Instanced in questions of property. — Mode in which it must be studied. — 3. Pretends to foretel future events. — Laws are a species of promises — check the freedom of opinion — are destructive of the principles of reason. — Dishonesty of lawyers. — An honest lawyer mischievous. — Abolition of law vindicated on the score of wisdom — of candour — from the nature of man. — Future history of political justice. — Errors that might arise in the commencement. — Its gradual progress. — Its effects on criminal law. — on property. p. 764

- CHAP. IX. OF PARDONS. Their absurdity. — Their origin. — Their abuses. — Their arbitrary character. — Destructive of morality. p. 781

- CHAP. I. GENUINE SYSTEM OF PROPERTY DELINEATED. Importance of this topic. — Abuses to which it has been exposed. — Criterion of property: justice. — Entitles each man to the supply of his animal wants as far as the general stock will afford it — to the means of well being. — Estimate of luxury. — Its pernicious effects on the individual who partakes of it. — Idea of labour as the foundation of property considered. — Its unreasonableness. — System of popular morality on this subject. — Defects of that system. p. 787

- CHAP. II. BENEFITS ARISING FROM THE GENUINE SYSTEM OF PROPERTY. Contrasted with the mischiefs of the present system, as consisting — 1. In a sense of dependence. — 2. In the perpetual spectacle of injustice, leading men astray in their desires — and perverting the integrity of their judgments. — The rich are the true pensioners. — 3. In the discouragement of intellectual attainments. — 4. In the multiplication of vice — generating the crimes of the poor — the passions of the rich — and the misfortunes of war. — 5. In depopulation. p. 799

- CHAP. III. OF THE OBJECTION TO THIS SYSTEM FROM THE ADMIRABLE EFFECTS OF LUXURY. Nature of the objection. — Luxury not necessary — either to population — or to the improvement of the mind. — Its true character. p. 814

- CHAP. IV. OF THE OBJECTION TO THIS SYSTEM FROM THE ALLUREMENTS OF SLOTH. The objection stated. — Such a state of society must have been preceded by great intellectual improvement. — The manual labour required in this state will be extremely small. — Universality of the love of distinction. — Operation of this motive under the system in question — will finally be superseded by a better motive. p. 818

- CHAP. V. OF THE OBJECTION TO THIS SYSTEM FROM THE IMPOSSIBILITY OF ITS BEING RENDERED PERMANENT. Grounds of the objection. — Its serious import. — Answer. — The introduction of such a system must be owing, 1. to a deep sense of justice — 2. to a clear insight into the nature of happiness — as being properly intellectual — not consisting in sensual pleasure — or the pleasures of delusion. — Influence of the passions considered. — Men will not accumulate either from individual foresight — or from vanity. p. 829

- CHAP. VI. OF THE OBJECTION TO THIS SYSTEM FROM THE INFLEXIBILITY OF ITS RESTRICTIONS. Nature of the objection. — Natural and moral independence distinguished — the first beneficial — the second injurious. — Tendency of restriction properly so called. — The genuine system of property not a system of restrictions — does not require common labour, meals or magazines. — Such restrictions absurd — and unnecessary. — Evils of cooperation. — Its province may perpetually be diminished. — Manual labour may be extinguished. — Consequent activity of intellect. — Ideas of the future state of cooperation. — Its limits. — Its legitimate province. — Evils of cohabitation — and marriage. — They oppose the developement of our faculties — are inimical to our happiness — and deprave our understandings. — Marriage a branch of the prevailing system of property. — Consequences of its abolition. — Education need not in that state of society be a subject of positive institution. — These principles do not lead to a sullen individuality — Partial attachments considered. — Benefits accruing from a just affection — materially promoted by these principles. — The genuine system of property does not prohibit accumulation — implies a certain degree of appropriation — and division of labour. p. 839

- CHAP. VII. OF THE OBJECTION TO THIS SYSTEM FROM THE PRINCIPLE OF POPULATION. The objection stated. — Remoteness of its operation. — Conjectural ideas respecting the antidote. — Omnipotence of mind. — Illustrations. — Causes of decrepitude. — Youth is prolonged by chearfulness — by clearness of apprehension — and a benevolent character. — The powers we possess are essentially progressive. — Effects of attention. — The phenomenon of sleep explained. — Present utility of these reasonings. — Application to the future state of society. p. 860

- CHAP. VIII. OF THE MEANS OF INTRODUCING THE GENUINE SYSTEM OF PROPERTY. Apprehensions that are entertained on this subject. — Idea of massacre. — Inference we ought to make upon supposition of the reality of these apprehensions. — Mischief by no means the necessary attendant on improvement. — Duties under this circumstance, 1. Of those who are qualified for public instructors — temper — sincerity. — Pernicious effects of dissimulation in this case. — 2. Of the rich and great. — Many of them may be expected to be advocates of equality. — Conduct which their interest as a body prescribes. — 3. Of the friends of equality in general. — Omnipotence of truth. — Importance of a mild and benevolent proceeding. — Connexion between liberty and equality. — Cause of equality will perpetually advance. — Symptoms of its progress — Idea of its future success. — Conclusion. p. 873

[v]

PREFACE.↩

FEW works of literature are held in greater estimation, than those which treat in a methodical and elementary way of the principles of science. But the human mind in every enlightened age is progressive; and the best elementary treatises after a certain time are reduced in their value by the operation of subsequent discoveries. Hence it has always been desired by candid enquirers, that preceding works of this kind should from time to time be superseded, and that other productions including the larger views that have since offered themselves, should be substituted in their place.

It would be strange if something of this kind were not desirable in politics, after the great change that has been produced in men's minds upon this subject, and the light that has been [vi] thrown upon it by the recent discussions of America and France. A sense of the value of such a work, if properly executed, was the motive which gave birth to these volumes. Of their execution the reader must judge.

Authors who have formed the design of superseding the works of their predecessors, will be found, if they were in any degree equal to the design, not merely to have collected the scattered information that had been produced upon the subject, but to have increased the science with the fruit of their own meditations. In the following work principles will occasionally be found, which it will not be just to reject without examination, merely because they are new. It was impossible perseveringly to reflect upon so prolific a science, and a science which may be said to be yet in its infancy, without being led into ways of thinking that were in some degree uncommon.

[vii]

Another argument in favour of the utility of such a work was frequently in the author's mind, and therefore ought to be mentioned. He conceived politics to be the proper vehicle of a liberal morality. That description of ethics deserves to be held in slight estimation, which seeks only to regulate our conduct in articles of particular and personal concern, instead of exciting our attention to the general good of the species. It appeared sufficiently practicable to make of such a treatise, exclusively of its direct political use, an advantageous vehicle of moral improvement. He was accordingly desirous of producing a work, from the perusal of which no man should rise without being strengthened in habits of sincerity, fortitude and justice.

Having stated the considerations in which the work originated, it is proper to mention a few circumstances of the outline of its history. The sentiments it contains are by no means the suggestions of a sudden effervescence of fancy. Political enquiry [viii] had long held a foremost place in the writer's attention. It is now twelve years since he became satisfied, that monarchy was a species of government unavoidably corrupt. He owed this conviction to the political writings of Swift and to a perusal of the Latin historians. Nearly at the same time he derived great additional instruction from reading the most considerable French writers upon the nature of man in the following order, Systéme de la Nature, Rousseau and Helvetius. Long before he thought of the present work, he had familiarised to his mind the arguments it contains on justice, gratitude, rights of man, promises, oaths and the omnipotence of truth. Political complexity is one of the errors that take strongest hold on the understanding; and it was only by ideas suggested by the French revolution, that he was reconciled to the desirableness of a government of the simplest construction. To the same event he owes the determination of mind which gave existence to this work.

[ix]

Such was the preparation which encouraged him to undertake the present treatise. The direct execution may be dismissed in a few words. It was projected in the month of May 1791: the composition was begun in the following September, and has therefore occupied a space of sixteen months. This period was devoted to the purpose with unremitted ardour. It were to be wished it had been longer; but it seemed as if no contemptible part of the utility of the work depended upon its early appearance.

The printing of the following treatise, as well as the composition, was influenced by the same principle, a desire to reconcile a certain degree of dispatch with the necessary deliberation. The printing was for that reason commenced, long before the composition was finished. Some disadvantages have arisen from this circumstance. The ideas of the author became more perspicuous and digested, as his enquiries advanced. The longer he considered the subject, the more accurately [x] he seemed to understand it. This circumstance has led him into a few contradictions. The principal of these consists in an occasional inaccuracy of language, particularly in the first book, respecting the word government. He did not enter upon the work, without being aware that government by its very nature counteracts the improvement of individual mind; but he understood the full meaning of this proposition more completely as he proceeded, and saw more distinctly into the nature of the remedy. This, and a few other defects, under a different mode of preparation would have been avoided. The candid reader will make a suitable allowance. The author judges upon a review, that these defects are such as not materially to injure the object of the work, and that more has been gained than lost by the conduct he has pursued.

The period in which the work makes its appearance is singular. The people of England have assiduously been excited to declare their loyalty, [xi] and to mark every man as obnoxious who is not ready to sign the Shibboleth of the constitution. Money is raised by voluntary subscription to defray the expence of prosecuting men who shall dare to promulgate heretical opinions, and thus to oppress them at once with the enmity of government and of individuals. This was an accident wholly unforeseen when the work was undertaken; and it will scarcely be supposed that such an accident could produce any alteration in the writer's designs. Every man, if we may believe the voice of rumour, is to be prosecuted who shall appeal to the people by the publication of any unconstitutional paper or pamphlet; and it is added, that men are to be prosecuted for any unguarded words that may be dropped in the warmth of conversation and debate. It is now to be tried whether, in addition to these alarming encroachments upon our liberty, a book is to fall under the arm of the civil power, which, beside the advantage of having for one of its express objects the dissuading from all tumult and violence, [xii] is by its very nature an appeal to men of study and reflexion. It is to be tried whether a project is formed for suppressing the activity of mind, and putting an end to the disquisitions of science. Respecting the event in a personal view the author has formed his resolution. Whatever conduct his countrymen may pursue, they will not be able to shake his tranquillity. The duty he is most bound to discharge is the assisting the progress of truth; and if he suffer in any respect for such a proceeding, there is certainly no vicissitude that can befal him, that can ever bring along with it a more satisfactory consolation.

But, exclusively of this precarious and unimportant consideration, it is the fortune of the present work to appear before a public that is panic struck, and impressed with the most dreadful apprehensions of such doctrines as are here delivered. All the prejudices of the human mind are in arms against it. This circumstance may appear to be of greater importance than the other. [xiii] But it is the property of truth to be fearless, and to prove victorious over every adversary. It requires no great degree of fortitude, to look with indifference upon the false fire of the moment, and to foresee the calm period of reason which will succeed.

AN ENQUIRY CONCERNING POLITICAL JUSTICE

VOLUME I

[1]

BOOK I.

OF THE IMPORTANCE OF POLITICAL INSTITUTIONS

CHAP. I.

INTRODUCTION↩

the subject proposed.—system of indifference—of passive obedience—of liberty.—system of liberty extended.

THE question which first presents itself in an enquiry concerningThe subject proposed. political institution, relates to the importance of the topic which is made thesubject of enquiry. All men will grant that the happiness of the human speciesis the most desirable object for human science to promote; and that intellectualand moral happiness or pleasure is extremely to be preferred [2] to those which are precarious and transitory. The methods which may be proposedfor the attainment of this object, are various. If it could be proved that asound political institution was of all others the most powerful engine for promotingindividual good, or on the other hand that an erroneous and corrupt governmentwas the most formidable adversary to the improvement of the species, it wouldfollow that politics was the first and most important subject of human investigation.

System of indifference: The opinions of mankind in this respect have been divided. By one set of men it is affirmed, that the different degrees of excellence ascribed to different forms of government are rather imaginary than real; that in the great objects of superintendance no government will eminently fail; and that it is neither the duty nor the wisdom of an honest and industrious individual to busy himself with concerns so foreign to the sphere of his industry.of passive obedience: A second class, in adopting the same principles, have given to them a different turn. Believing that all governments are nearly equal in their merit, they have regarded anarchy as the only political mischief that deserved to excite alarm, and have been the zealous and undistinguishing adversaries of all innovation. Neither of these classes has of course been inclined to ascribe to the science and practice of politics a pre-eminence over every other.

of liberty. But the advocates of what is termed political liberty have al [3] ways been numerous. They have placed this liberty principally in two articles; the security of our persons, and the security of our property. They have perceived that these objects could not be effected but by the impartial administration of general laws, and the investing in the people at large a certain power sufficient to give permanence to this administration. They have pleaded, some for a less and some for a greater degree of equality among the members of the community; and they have considered this equality as infringed or endangered by enormous taxation, and the prerogatives and privileges of monarchs and aristocratical bodies.

But, while they have been thus extensive in the object of their demand, they seem to have agreed with the two former classes in regarding politics as an object of subordinate importance, and only in a remote degree connected with moral improvement. They have been prompted in their exertions rather by a quick sense of justice and disdain of oppression, than by a consciousness of the intimate connection of the different parts of the social system, whether as it relates to the intercourse of individuals, or to the maxims and institutes of states and nations [*].

It may however be reasonable to consider whether the sciencesystem of liberty extended. of politics be not of somewhat greater value than any of these [4] reasoners have been inclined to suspect. It may fairly be questioned, whether government be not still more considerable in its incidental effects, than in those intended to be produced. Vice, for example, depends for its existence upon the existence of temptation. May not a good government strongly tend to extirpate, and a bad one to increase the mass of temptation? Again, vice depends for its existence upon the existence of error. May not a good government by taking away all restraints upon the enquiring mind hasten, and a bad one by its patronage of error procrastinate the discovery and establishment of truth? Let us consider the subject in this point of view. If it can be proved that the science of politics is thus unlimited in its importance, the advocates of liberty will have gained an additional recommendation, and its admirers will be incited with the greater eagerness to the investigation of its principles.

[5]

CHAP. II.

HISTORY OF POLITICAL SOCIETY↩

frequency of war—among the ancients—among the moderns—the french—the english.—causes of war.—penal laws.—despotism.—deduction.—enumeration of arguments.

WHILE we enquire whether governmentis capable ofFrequency of war: improvement, we shall do well to considerits present effects. It is an old observation, thatthe history of mankind is little else than the historyof crimes. War has hitherto been considered as theinseparable ally of political institution. Theamong the ancients: earliest records of time are the annals of conquerors and heroes,a Bacchus, a Sesostris, a Semiramis and a Cyrus. Theseprinces led millions of men under their standard, andravaged innumerable provinces. A small number onlyof their forces ever returned to their native homes,the rest having perished of diseases, hardships andmisery. The evils they inflicted, and the mortalityintroduced in the countries against which their expeditionswere directed, were certainly not less severe thanthose which their countrymen suffered. No sooner doeshistory become more precise, than we are presentedwith the four great monarchies, that is, with foursuccessful projects, by means of [6] bloodshed, violence and murder, of enslaving mankind. The expeditionsof Cambyses against Egypt, of Darius against the Scythians,and of Xerxes against the Greeks, seem almost to setcredibility at defiance by the fatal consequences withwhich they were attended. The conquests of Alexandercost innumerable lives, and the immortality of Cæsaris computed to have been purchased by the death ofone million two hundred thousand men. Indeed the Romans,by the long duration of their wars, and their inflexibleadherence to their purpose, are to be ranked amongthe foremost destroyers of the human species. Theirwars in Italy endured for more than four hundred years,and their contest for supremacy with the Carthaginianstwo hundred. The Mithridatic war began with a massacreof one hundred and fifty thousand Romans, and in threesingle actions of the war five hundred thousand menwere lost by the eastern monarch. Sylla, his ferociousconqueror, next turned his arms against his country,and the struggle between him and Marius was attendedwith proscriptions, butcheries and murders that knewno restraint from mercy and humanity. The Romans, atlength, suffered the penalty of their iniquitous deeds;and the world was vexed for three hundred years bythe irruptions of Goths, Vandals, Ostrogoths, Huns,and innumerable hordes of barbarians.

among the moderns: I forbear to detail the victorious progress of Mahomet and the pious expeditions of Charlemagne. I will not enumerate the crusades against the infidels, the exploits of Aurungzebe, [7] Gengiskan and Tamerlane, or the extensive murders of the Spaniards in the new world. Let us examine the civilized and favoured quarter of Europe, or even those countries of Europe which are thought most enlightened.

France was wasted by successive battles during a whole century,the French: for the question of the Salic law, and the claim of the Plantagenets. Scarcely was this contest terminated, before the religious wars broke out, some idea of which we may form from the siege of Rochelle, where of fifteen thousand persons shut up eleven thousand perished of hunger and misery; and from the massacre of Saint Bartholomew, in which the numbers assassinated were forty thousand. This quarrel was appeased by Henry the fourth, and succeeded by the thirty years war in Germany for superiority with the house of Austria, and afterwards by the military transactions of Louis the fourteenth.

In England the war of Cressy and Agincourt only gave placethe English. to the civil war of York and Lancaster, and again after an interval to the war of Charles the first and his parliament. No sooner was the constitution settled by the revolution, than we were engaged in a wide field of continental warfare by king William, the duke of Marlborough, Maria Theresa and the king of Prussia.

And what are in most cases the pretexts upon which war isCauses of war. [8] undertaken? What rational man could possibly have given himself the least disturbance for the sake of choosing whether Henry the sixth or Edward the fourth should have the style of king of England? What Englishman could reasonably have drawn his sword for the purpose of rendering his country an inferior dependency of France, as it must necessarily have been if the ambition of the Plantagenets had succeeded? What can be more deplorable than to see us first engage eight years in war rather than suffer the haughty Maria Theresa to live with a diminished sovereignty or in a private station; and then eight years more to support the free-booter who had taken advantage of her helpless condition?

The usual causes of war are excellently described by Swift. “Sometimes the quarrel between two princes is to decide which of them shall dispossess a third of his dominions, where neither of them pretends to any right. Sometimes one prince quarrels with another, for fear the other should quarrel with him. Sometimes a war is entered upon because the enemy is too strong; and sometimes because he is too weak. Sometimes our neighbours want the things which we have, or have the things which we want; and we both fight, till they take ours, or give us theirs. It is a very justifiable cause of war to invade a country after the people have been wasted by famine, destroyed by pestilence, or embroiled by factions among themselves. It is justifiable to enter into a war against our nearest ally, when one of his towns lies convenient for us, or a territory of land, that [9] would render our dominions round and compact. If a prince sends forces into a nation where the people are poor and ignorant, he may lawfully put the half of them to death, and make slaves of the rest, in order to civilize and reduce them from their barbarous way of living. It is a very kingly, honourable and frequent practice, when one prince desires the assistance of another to secure him against an invasion, that the assistant, when he has driven out the invader, should seize on the dominions himself, and kill, imprison or banish the prince he came to relieve [*] .”

If we turn from the foreign transactions of states with eachPenal laws. other, to the principles of their domestic policy, we shall not find much greater reason to be satisfied. A numerous class of mankind are held down in a state of abject penury, and are continually prompted by disappointment and distress to commit violence upon their more fortunate neighbours. The only mode which is employed to repress this violence, and to maintain the order and peace of society, is punishment. Whips, axes and gibbets, dungeons, chains and racks are the most approved and established methods of persuading men to obedience, and impressing upon their minds the lessons of reason. Hundreds of victims are annually sacrificed at the shrine of positive law and political institution.

[10]

Despotism. Add to this the species of government which prevails over nine tenths of the globe, which is despotism: a government, as Mr. Locke justly observes, altogether “vile and miserable,” and “more to be deprecated than anarchy itself. [*]

Deduction. This account of the history and state of man is not a declamation, but an appeal to facts. He that considers it cannot possibly regard political disquisition as a trifle, and government as a neutral and unimportant concern. I by no means call upon the reader implicitly to admit that these evils are capable of remedy, and that wars, executions and despotism can be extirpated out of the world. But I call upon him to consider whether they may be remedied. I would have him feel that civil policy is a topic upon which the severest investigation may laudably be employed.

If government be a subject, which, like mathematics, natural [11] philosophy and morals, admits of argument and demonstration, then may we reasonably hope that men shall some time or other agree respecting it. If it comprehend every thing that is most important and interesting to man, it is probable that, when the theory is greatly advanced, the practice will not be wholly neglected. Men may one day feel that they are partakers of a common nature, and that true freedom and perfect equity, like food and air, are pregnant with benefit to every constitution. If there be the faintest hope that this shall be the final result, then certainly no subject can inspire to a sound mind such generous enthusiasm, such enlightened ardour and such invincible perseverance.

The probability of this improvement will be sufficiently established,Enumeration of arguments. if we consider, first, that the moral characters of men are the result of their perceptions: and, secondly, that of all the modes of operating upon mind government is the most considerable. In addition to these arguments it will be found, thirdly, that the good and ill effects of political institution are not less conspicuous in detail than in principle; and, fourthly, that perfectibility is one of the most unequivocal characteristics of the human species, so that the political, as well as the intellectual state of man, may be presumed to be in a course of progressive improvement.

[12]

CHAP. III.

THE MORAL CHARACTERS OF MEN ORIGINATE IN THEIR PERCEPTIONS↩

no innate principles.—objections to this assertion—from the early actions of infants—from the desire of self-preservation—from self-love—from pity—from the vices of children—tyranny.—sullenness.—conclusion.

No innate principles. WE bring into the world with us no innateprinciples: consequently we are neither virtuous norvicious as we first come into existence. No truth canbe more evident than this, to any man who will yieldthe subject an impartial consideration. Every principleis a proposition. Every proposition consists in theconnection of at least two distinct ideas, which areaffirmed to agree or disagree with each other. If thereforethe principles be innate, the ideas must be so too.But nothing can be more incontrovertible, than thatwe do not bring pre-established ideas into the worldwith us.

Let the innate principle be, that virtue is a rule to which we are obliged to conform. Here are three great and leading ideas, not to mention subordinate ones, which it is necessary to form, before we can so much as understand the proposition.

[13]

What is virtue? Previously to our forming an idea corresponding to this general term, it seems necessary that we should have observed the several features by which virtue is distinguished, and the several subordinate articles of right conduct, that taken together, constitute that mass of practical judgments to which we give the denomination of virtue. Virtue may perhaps be defined, that species of operations of an intelligent being, which conduces to the benefit of intelligent beings in general, and is produced by a desire of that benefit. But taking for granted the universal admission of this definition, and this is no very defensible assumption, how widely have people of different ages and countries disagreed in the application of this general conception to particulars? a disagreement by no means compatible with the supposition that the sentiment is itself innate.

The next innate idea included in the above proposition, is that of a rule or standard, a generical measure with which individuals are to be compared, and their conformity or disagreement with which is to determine their value.

Lastly, there is the idea of obligation, its nature and source, the obliger and the sanction, the penalty and the reward.

Who is there in the present state of scientifical improvement, that will believe that this vast chain of perceptions and notions is [14] something that we bring into the world with us, a mystical magazine, shut up in the human embryo, whose treasures are to be gradually unfolded as circumstances shall require? Who does not perceive that they are regularly generated in the mind by a series of impressions, and digested and arranged by association and reflexion?

Objections to this assertion: from the early actions of infants: Experience has by many been supposed adverse to these reasonings: but it will upon examination be found to be perfectly in harmony with them. The child at the moment of his birth is totally unprovided with ideas, except such as his mode of existence in the womb may have supplied. His first impressions are those of pleasure and pain. But he has no foresight of the tendency of any action to obtain either the one or the other, previously to experience.

A certain irritation of the palm of the hand will produce that contraction of the fingers, which accompanies the action of grasping. This contraction will at first be unaccompanied with design, the object will be grasped without any intention to retain it, and let go again without thought or observation. After a certain number of repetitions, the nature of the action will be perceived; it will be performed with a consciousness of its tendency; and even the hand stretched out upon the approach of any object that is desired. Present to the child, thus far instructed, a lighted candle. The sight of it will produce a pleasurable state of the organs of [15] perception. He will stretch out his hand to the flame, and will have no apprehension of the pain of burning till he has felt the sensation.

At the age of maturity, the eyelids instantaneously close, when any substance, from which danger is apprehended, is advanced towards them; and this action is so spontaneous, as to be with great difficulty prevented by a grown person, though he should explicitly desire it. In infants there is no such propensity; and an object may be approached to their organs, however near and however suddenly, without producing this effect. Frowns will be totally indifferent to a child, who has never found them associated with the effects of anger. Fear itself is a species of foresight; and in no case exists till introduced by experience.

It has been said, that the desire of self-preservation is innate.from the desire of self-preservation: I demand what is meant by this desire? Must we not understand by it, a preference of existence to non-existence? Do we prefer any thing but because it is apprehended to be good? It follows, that we cannot prefer existence, previously to our experience of the motives for preference it possesses. Indeed the ideas of life and death are exceedingly complicated, and very tardy in their formation. A child desires pleasure and loathes pain, long before he can have any imagination respecting the ceasing to exist.

Again, it has been said, that self-love is innate. But therefrom self-love; cannot be an error more easy of detection. By the love of [16] self we understand the approbation of pleasure, and dislike of pain: but this is only the faculty of perception under another name. Who ever denied that man was a percipient being? Who ever dreamed that there was a particular instinct necessary to render him percipient?

from pity: Pity has sometimes been supposed an instance of innate principle; particularly as it seems to arise more instantaneously in young persons, and persons of little refinement, than in others. But it was reasonable to expect, that threats and anger, circumstances that have been associated with our own sufferings, should excite painful feelings in us in the case of others, independently of any laboured analysis. The cries of distress, the appearance of agony or corporal infliction, irresistibly revive the memory of the pains accompanied by those symptoms in ourselves. Longer experience and observation enable us to separate the calamities of others and our own safety, the existence of pain in one subject and of pleasure or benefit in others, or in the same at a future period, more accurately than we could be expected to do previously to that experience.

from the vices of children: Such then is universally the subject of human institution and education. We bring neither virtue nor vice with us at our entrance into the world. But the seeds of error are ordinarily sown so early as to pass with superficial observers for innate.

[17]

Our constitution prompts us to utter a cry at the unexpectedtyranny: sensation of pain. Infants early perceive the assistance they obtain from the volition of others; and they have at first no means of inviting that assistance but by an inarticulate cry. In this neutral and innocent circumstance, combined with the folly and imbecility of parents and nurses, we are presented with the first occasion of vice. Assistance is necessary, conducive to the existence, the health and the mental sanity of the infant. Empire in the infant over those who protect him is unnecessary. If we do not withhold our assistance precisely at the moment when it ceases to be requisite, if our compliance or our refusal be not in every case irrevocable, if we grant any thing to impatience, importunity or obstinacy, from that moment we become parties in the intellectual murder of our offspring.

In this case we instil into them the vices of a tyrant; but wesullenness. are in equal danger of teaching them the vices of a slave. It is not till very late that mankind acquire the ideas of justice, retribution and morality, and these notions are far from existing in the minds of infants. Of consequence, when we strike, or when we rebuke them, we risk at least the exciting in them a sense of injury, and a feeling of resentment. Above all, sentiments of this sort cannot fail to be awakened, if our action be accompanied with symptoms of anger, cruelty, harshness or caprice. The same imbecility, that led us to inspire them with a spirit of tyranny by yielding to their importunities, afterwards dictates to [18] us an inconsistent and capricious conduct, at one time denying them as absurdly, as at another we gratified them unreasonably. Who, that has observed the consequences of this treatment, how generally these mistakes are committed, how inseparable they are in some degree from the wisest and the best, will be surprised at the early indications of depravity in children [*] ?

Conclusion. From these reasonings it sufficiently appears, that the moral qualities of men are the produce of the impressions made upon them, and that there is no instance of an original propensity to evil. Our virtues and vices may be traced to the incidents which make the history of our lives, and if these incidents could be divested of every improper tendency, vice would be extirpated from the world. The task may be difficult, may be of slow progress, and of hope undefined and uncertain. But hope will never desert it; and the man who is anxious for the benefit of his species, will willingly devote a portion of his activity to an enquiry into the mode of effecting this extirpation in whole or in part, an enquiry which promises much, if it do not in reality promise every thing.

[19]

CHAP. IV.

THREE PRINCIPAL CAUSES OF MORAL IMPROVEMENT CONSIDERED↩

- I. LITERATURE.

benefits of literature.—examples.—essential properties of literature.—its defects.- II. EDUCATION.

benefits of education.—causes of its imbecility.- III. POLITICAL JUSTICE.

benefits of political institution.—universality of its influence—proved by the mistakes of society.—origin of evil.

THERE are three principal causes by which the human mind is advanced towards a state of perfection; literature, or the diffusion of knowledge through the medium of discussion, whether written or oral; education, or a scheme for the early impression of right principles upon the hitherto unprejudiced mind; and political justice, or the adoption of any principle of morality and truth into the practice of a community. Let us take a momentary review of each of these.

[20]

I. LITERATURE

Benefits of literature. FEW engines can be more powerful, and at the same time more salutary in their tendency, than literature. Without enquiring for the present into the cause of this phenomenon, it is sufficiently evident in fact, that the human mind is strongly infected with prejudice and mistake. The various opinions prevailing in different countries and among different classes of men upon the same subject, are almost innumerable; and yet of all these opinions only one can be true. Now the effectual way for extirpating these prejudices and mistakes seems to be literature.

Examples. Literature has reconciled the whole thinking world respecting the great principles of the system of the universe, and extirpated upon this subject the dreams of romance and the dogmas of superstition. Literature has unfolded the nature of the human mind, and Locke and others have established certain maxims respecting man, as Newton has done respecting matter, that are generally admitted for unquestionable. Discussion has ascertained with tolerable perspicuity the preference of liberty over slavery; and the Mainwarings, the Sibthorpes, and the Filmers, the race of speculative reasoners in favour of despotism, are almost extinct. Local prejudice had introduced innumerable privileges and prohibitions upon the subject of trade; speculation has nearly ascertained that perfect freedom is most favour [21] able to her prosperity. If in many instances the collation of evidence have failed to produce universal conviction, it must however be considered, that it has not failed to produce irrefragable argument, and that falshood would have been much shorter in duration, if it had not been protected and inforced by the authority of political government.

Indeed, if there be such a thing as truth, it must infalliblyEssential properties of literature. be struck out by the collision of mind with mind. The restless activity of intellect will for a time be fertile in paradox and error; but these will be only diurnals, while the truths that occasionally spring up, like sturdy plants, will defy the rigour of season and climate. In proportion as one reasoner compares his deductions with those of another, the weak places of his argument will be detected, the principles he too hastily adopted will be overthrown, and the judgments, in which his mind was exposed to no sinister influence, will be confirmed. All that is requisite in these discussions is unlimited speculation, and a sufficient variety of systems and opinions. While we only dispute about the best way of doing a thing in itself wrong, we shall indeed make but a trifling progress; but, when we are once persuaded that nothing is too sacred to be brought to the touchstone of examination, science will advance with rapid strides. Men, who turn their attention to the boundless field of enquiry, and still more who recollect the innumerable errors and caprices of mind, are apt to imagine that the labour is without benefit [22] and endless. But this cannot be the case, if truth at last have any real existence. Errors will, during the whole period of their reign, combat each other; prejudices that have passed unsuspected for ages, will have their era of detection; but, if in any science we discover one solitary truth, it cannot be overthrown.

Its defects. Such are the arguments that may be adduced in favour of literature. But, even should we admit them in their full force, and at the same time suppose that truth is the omnipotent artificer by which mind can infallibly be regulated, it would yet by no means sufficiently follow that literature is alone adequate to all the purposes of human improvement. Literature, and particularly that literature by which prejudice is superseded, and the mind is strung to a firmer tone, exists only as the portion of a few. The multitude, at least in the present state of human society, cannot partake of its illuminations. For that purpose it would be necessary, that the general system of policy should become favourable, that every individual should have leisure for reasoning and reflection, and that there should be no species of public institution, which, having falshood for its basis, should counteract their progress. This state of society, if it did not precede the general dissemination of truth, would at least be the immediate result of it.

But in representing this state of society as the ultimate result, [23] we should incur an obvious fallacy. The discovery of truth is a pursuit of such vast extent, that it is scarcely possible to prescribe bounds to it. Those great lines, which seem at present to mark the limits of human understanding, will, like the mists that rise from a lake, retire farther and farther the more closely we approach them. A certain quantity of truth will be sufficient for the subversion of tyranny and usurpation; and this subversion, by a reflected force, will assist our understandings in the discovery of truth. In the mean time, it is not easy to define the exact portion of discovery that must necessarily precede political melioration. The period of partiality and injustice will be shortened, in proportion as political rectitude occupies a principal share in our disquisition. When the most considerable part of a nation, either for numbers or influence, becomes convinced of the flagrant absurdity of its institutions, the whole will soon be prepared tranquilly and by a sort of common consent to supersede them.

II. EDUCATION

But, if it appear that literature, unaided by the regularityBenefits of education. of institution and discipline, is inadequate to the reformation of the species, it may perhaps be imagined, that education, commonly so called, is the best of all subsidiaries for making up its defects. Education may have the advantage of taking mind in its original state, a soil prepared for culture, and as yet unin [24] fested with weeds; and it is a common and a reasonable opinion, that the task is much easier to plant right and virtuous dispositions in an unprejudiced understanding, than to root up the errors that have already become as it were a part of ourselves. If an erroneous and vicious education be, as it has been shewn to be, the source of all our depravity, an education, deprived of these errors, seems to present itself as the most natural exchange, and must necessarily render its subject virtuous and pure.

I will imagine the pupil never to have been made the victim of tyranny or the slave of caprice. He has never been permitted to triumph in the success of importunity, and cannot therefore well have become restless, inconstant, fantastical or unjust. He has been inured to ideas of equality and independence, and therefore is not passionate, haughty and overbearing. The perpetual witness of a temperate conduct and reasonable sentiments, he is not blinded with prejudice, is not liable to make a false estimate of things, and of consequence has no immoderate desires after wealth, and splendour, and the gratifications of luxury. Virtue has always been presented to him under the most attractive form, as the surest medium of success in every honourable pursuit, the never-failing consolation of disappointment, and infinitely superior in value to every other acquisition.

[25]