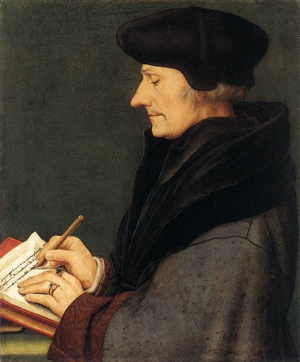

Desiderius Erasmus, The Education of a Christian Prince (1516)

|

|

| Desiderius Erasmus (1466-1536) |

Source

The Institutio principis Christiani (The Education of a Christian Prince) (Basel, 1516).

This translation is based upon Lester Born's of 1936 and compared with the 1703 Leyden edition (in Latin) and Percy Corbett's of 1921.

- The Grotius Society Publications. Texts for Students of International Relations. No. 1. Erasmus’ “Institutio Principles Christiani.” Chapters III-XI. Translated, with a Introduction by Percy Elwood Corbett. (London: Sweet and Maxwell, 1921). Facs. PDF.

- Institutio principis Christiani in Opera omnia (Leyden, 1705-6), Vol. IV, pp. pp. 559-612. Facs. PDF.

Note: the pagination is that of the Leyden 1703 edition of volume 4 of Erasmus' Opera Omnia.

Table of Contents

- DEDICATORY EPISTLE

- I. THE QUALITIES, EDUCATION, AND SIGNIFICANCE OF A CHRISTIAN PRINCE]

- II. THE PRINCE MUST AVOID FLATTERERS

- III. THE ARTS OF PEACE

- IV. ON TRIBUTES AND TAXES

- V. ON THE BENEFICENCES OF THE PRINCE

- VI. ON ENACTING OR EMENDING LAWS

- VII. ON MAGISTRATES AND THEIR FUNCTIONS

- VIII. ON TREATIES

- IX. ON THE MARRIAGE ALLIANCES OF PRINCES

- X. ON THE OCCUPATIONS OF THE PRINCE IN PEACE

- XI. ON BEGINNING WAR

[DEDICATORY EPISTLE]

TO THE MOST ILLUSTRIOUS PRINCE CHARLES,

GRANDSON OF THE INVINCIBLE CAESAR

MAXIMILIAN,

DESIDERIUS ERASMUS OF ROTTERDAM SENDS GREETINGS

Wisdom is not only an extraordinary attribute in itself, Charles, most bountiful of princes, but according to Aristotle no form of wisdom is greater than that which teaches a prince how to rule beneficently. Accordingly, Xenophon was quite correct in saying in his Oeconomicus that he thought it something beyond the human sphere and clearly divine, to rule over free and willing subjects. That kind of wisdom is indeed to be sought by princes, which Solomon as a youth of good parts, spurning all else, alone desired, and which he wished to be his constant companion on the throne. This is that purest and most beautiful wisdom of Sunamite, by whose embraces alone was David pleased, he that wisest son of an all-wise father. This is the wisdom which is referred to in Proverbs:"Through me princes rule, and the powerful pass judgment." Whenever kings call this wisdom into council and exclude those basest of advisers - ambition, wrath, cupidity, andflattery - the state flourishes in every way and, realizing that its prosperity comes from the wisdom of the prince, rejoices rightly in itself with these words: "All good things together come to me with her [i.e., wisdom]." Plato is nowhere more painstaking than in the training of his guardians of the state. He does not wish them to excel all others in wealth, in gems, in dress, in statues and attendants, but in wisdom alone. He says that no state will ever be blessed unless the philosophers are at the helm, or those to whom the task of government falls embrace philosophy. By "philosophy" I do not mean that which disputes concerning the first beginnings of primordial matter, of motion and infinity, but that which frees the mind from the false opinion and the vicious predilections of the masses and points out a theory of government according to the example of the Eternal Power. It was something such as this that Homer had in mind when [he had] Mercury protect Ulysses against the potions of Circe with the molu flower. And not without reason did Plutarch say that no one serves the state better than he who imbues the mind of the prince, who provides and cares for everyone and everything, with the best of ideas and those most becoming a prince. On the other hand, no one brings so serious a blight upon the affairs of men as he who has corrupted the heart of the prince with depraved ideas and desires. He is no different from one who has poisoned the public fountain whence all men drink. Likewise Plutarch judges not inapposite that celebrated remark of Alexander the Great: Departing from the talk he had had with Diogenes the Cynic, and still marveling at his philosophic spirit, so proud, unbroken, unconquered, and superior to all things human, he said, "If I were not Alexander, I should like to be Diogenes." Nay, as great authority is exposed to so many storms, the more was that spirit of Diogenes to be sought after, since he could rise to the measure of such towering tumults.

But as much as you surpass Alexander in good fortune, mighty prince Charles, so much do we hope you will surpass him in wisdom. For he had gained a mighty empire, albeit one not destined to endure, solely through bloodshed. You have been born to a splendid kingdom and are destined to a still greater one. As Alexander had to toil to carry out his invasions, so will you have to labor to yield, rather than to gain, part of your power. You owe it to the powers of heaven that you came into a kingdom untainted with blood, bought through no evil connection. It will be the lot of your wisdom to keep it bloodless and peaceful. You have the inborn nature, the soundness of mind, the force of character, and you have received a training under the most reliable preceptors. So many examples from your ancestors surround you on every side, that we all have the highest hopes that Charles will some day do what the world long hoped his father Philip would do. And he [Philip] would not have disappointed the popular expectation if death had not cut him off before his time. And so, although I am not unaware that your highness does not need the advice of anyone, and least of all my advice, yet it has seemed best to set forth the likeness of the perfect prince for general information, but addressed to you. In this way those who are being brought up to rule great kingdoms will receive their theory of government through you and take their example from you. At the same time the good from this treatise will spread out to all under your auspices, and we of your entourage may manifest somewhat by these first fruits, as it were, the zeal of our spirit toward you.

We have done into Latin Isocrates's precepts on ruling a kingdom. We have fashioned ours, set off with subject headings so as to be less inconvenient to the reader, after the fashion of his, but differing not a little from his suggestions. That sophist was instructing a young king, or rather a tyrant: one pagan instructing another. I, a theologian, am acting the part of teacher to a distinguished and pure-hearted prince - one Christian to another. If I were writing these things for a prince of more advanced age, I should perhaps come under the suspicions of some for flattery or impertinence. But since this little book is dedicated to one who, although he evidences the highest hopes for himself, is still so youthful and so recently installed in his power that he could not as yet do many things which people are wont to praise or censure in princes, I am free from suspicion on both charges and cannot appear to have sought any object beyond the public welfare. That to the friends of kings (as to kings themselves) ought to be the only aim. Among the countless distinctions and praises which virtue, by the will of God, will prepare for you, this will be no small part: Charles was such an one that anyone could without the mark of flattery present [to him] the likeness of a pure and true Christian prince, which the excellent prince would happily recognize, or wisely imitate as a young man always eager to better himself. With best wishes.

[I. THE QUALITIES, EDUCATION, AND SIGNIFICANCE OF A CHRISTIAN PRINCE]

[B 433, L 562]

When a prince is to be chosen by election it is not at all appropriate to look to the images of his forefathers, to consider his physical appearance, his height of stature (which we read that some barbarians once most stupidly did) and to seek a quiet and placid trend of spirit. Seek rather a nature staid, in no way rash, and not so excitable that there is danger of his developing into a tyrant under the license of good fortune and casting aside all regard for advisers and counselors. Yet have a care that he be not so weak as to be turned now this way and now that by whomsoever he meets. Consider also his experience and his age - not so severe as to be entirely out of sympathy with frivolity, nor so impetuous as to be carried away by flights of fancy. Perhaps some consideration should also be paid to the state of health of the prince so that there will be no danger of a sudden succession to be filled, which would be a hardship on the state.

In navigation the wheel is not given to him who surpasses his fellows in birth, wealth, or appearance, but rather to him who excels in his skill as a navigator, in his alertness, and in his dependability. Just so with the rule of a state: most naturally the power should be entrusted to him who excels all in the requisite kingly qualities of wisdom, justice, moderation, foresight, and zeal for the public welfare.

Statues, gold, and gems contribute no more to state government than they do to a master in steering his ship. That one idea which should concern a prince in ruling, should likewise concern the people in selecting their prince: the public weal, free from all private interests.

The more difficult it is to change your choice, the more circumspectly should your candidate be chosen, or else the rashness of a single hour may spread its retributions over a lifetime. There is no choice, however, in the case of hereditary succession of princes. This was the usual practice with various barbarian nations of old, as Aristotle tells us, and it is also almost universally accepted in our own times. Under that condition, the chief hope for a good prince is from his education, which should be especially looked to. In this way the interest in his education will compensate for the loss of the right of election. Hence, from the very cradle, as it were, the mind of the future prince, while still open and unmolded, must be filled with salutary thoughts. Then the seeds of morality must be sown in the virgin soil of his spirit so that little by little they may grow and mature through age and experience, to remain firmly implanted throughout the course of life. Nothing remains so deeply and tenaciously rooted as those things learned in the first years. What is absorbed in those years is of prime importance to all, especially in the case of a prince.

When there is no opportunity to choose the prince, care should be exercised in the same manner in choosing the tutor to the future prince. That a prince be born of worthy characterwe must beseech the gods above; that a prince born of good parts may not go amiss, or that one of mediocre accomplishments may be bettered through education is mainly within our province. It was formerly the custom to decree Statues, arches, and honorary titles to those deserving honor from the state. None is more worthy of this honor than he who labors faithfully and zealously in the proper training of the prince [B 434] and looks not to personal emolument but rather to the welfare of his country. A country owes everything to a good prince; him it owes to the man who made him such by his moral principles. There is no better time to shape and improve a prince than when he does not yet realize himself a prince. This time must be diligently employed, not only to the end that for a while he may be kept away from base associations, but also that he may be imbued with certain definite moral principles. If diligent parents raise with great care a boy who is destined to inherit only an acre or two, think how much interest and concern should be given to the education of one who will succeed not to a single dwelling, but to so many peoples, to so many cities, yea, to the world, either as a good man for the common gain of all, or an evil one, to the great ruination of all! It is a great and glorious thing to rule an empire well, but nonetheless glorious to pass it on to no worse a ruler: nay, rather it is the main task of a good prince to see that he does not become a bad one. So conduct your rule as if this were your aim: "My equal shall never succeed me I" In the meantime, raise your children for future rule as if it were your desire to be succeeded by a better prince. There can be no more splendid commendation of a worthy prince than to say that he left such a successor to the state, that he himself seemed average by comparison. His own glory cannot be more truly shown than to be so obscured. The worst possible praise is that a ruler who was intolerable during his life is longingly missed as a good and beneficial prince each time a worse man ascends the throne. Let the good and wise prince always so educate his children that he seems ever to have remembered that they were born for the state and are being educated for the state, not for his own fancy.

Concern for the state must always be superior to the personal feelings of the parent. However many statues he may set up, however many massive works he may erect, a prince can have no more excellent monument to his worth than a son, splendid in every way, who is like his excellent father in his outstanding deeds. He does not die, who leaves a living likeness of himself! The prince should choose for this duty teachers from among all the number of his subjects - or even summon from every direction men of good character, unquestioned principles, serious, of long experience and not merely learned in theories - to whom advancing years provide deep respect; purity of life, prestige; sociability and an affable manner, love and friendship. Thus a tender young spirit may not be cut by the severity of its training and learn to hate worthiness before it knows it; nor on the other hand, debased by the unseasoned indulgence of its tutor, slip back where it should not." In the education of anyone, but especially in the case of a prince, the teacher must adopt a mid-course; he should be stern enough to suppress the wild pranks of youth, yet have a friendly understanding to lessen and temper the severity of his restraint." Such a man should the future prince's tutor be (as Seneca elaborately sets forth), that he can scold without railing, praise without flattering, be revered for his stainless life, and loved for his pleasing manner.

Some princes exercise themselves greatly over the proper care of a beautiful horse, or a bird, or a dog, yet consider it a matter of no importance to whom they entrust the training of their son. Him they often put in the hands of such teachers as no common citizen with any sense at all would want in charge of his sons [L 564]. Of what consequence is it to have begot a son for the throne, unless you educate him for his rule? Neither is the young prince to be given to any sort of nurse, but only to those of stainless character, who have been previously instructed in their duties and are well trained. He should not be allowed to associate with whatever playmates appear, but only with those boys of good and modest character; he should be reared and trained most carefully and as becomes a gentleman. That whole crowd of wantons, hard drinkers, filthy- tongued fellows, especially flatterers , must be kept far from his sight and hearing while his mind is not yet fortified with precepts to the contrary. Since the natures of so many men are inclined towards the ways of evil, there is no nature so happily born that it cannot be corrupted by wrong training. What do you expect except a great fund of evil in a prince, who, regardless of his native character (and a long line of ancestors does not necessarily furnish a mind, as it does a kingdom), is beset from his very cradle by the most inane opinions; is raised in the circle of senseless women; grows to boyhood among naughty girls, abandoned playfellows, and the most abject flatterers, among buffoons and mimes, drinkers and gamesters, and worse than stupid and worthless creators of wanton pleasures. In the company of all of these he hears nothing, learns nothing, absorbs nothing except pleasures, amusements, arrogance, haughtiness, greed, petulance, and tyranny - and from this school he will soon progress to the government of his kingdom! Although each one of all the great arts is very difficult, there is none finer nor more difficult than that of ruling well. Why in the case of this one thing alone do we feel the need of no training, but deem it sufficient to have been born for it? To what end except tyranny do they devote themselves as men, who as boys played at nothing except as tyrants?

[B.435] It is too much even to hope that all men will be good, yet it is not difficult to select from so many thousands one or two, who are conspicuous for their honesty and wisdom, through whom many good men may be gained in simple fashion. The real young prince should hold his youth in dis-

[some text is missing here]

... righteous it is, the more it is beset with shameful vices, unless improved by wholesome teachings.

Those shores which receive the severest pounding of the waves we are wont to bulwark most carefully. Now there are countless things which can turn the minds of princes from the true course - great fortune, worldly wealth in abundance, the pleasures of luxurious extravagance, freedom to do anything they please, the precedents of great but foolish princes, the storms and turmoils of human affairs themselves, and above all else, flattery , spoken in the guise of faith and frankness. On this account must the prince be the more sincerely strengthened with the best of principles and the precedents of praiseworthy princes.

Just as one who poisons the public fountain from which all drink deserves more than one punishment, so he is the most harmful who infects the mind of the prince with base ideas, which later produce the destruction of so many men. If any one counterfeits the prince's coinage, he is beaten about the head [B 436]; surely he who corrupts the character of the prince is even more deserving of that punishment. The teacher should enter at once upon his duties, so as to implant the seeds of good moral conduct while the senses of the prince are still in the tenderness of youth, while his mind is furthest removed from all vices and tractably yields to the hand of guidance in whatever it directs. He is immature both in body and mind, as in his sense of duty. The teacher's task is always the same, but he must employ one method in one case, and another in another. While his pupil is still a little child, he can bring in his teachings through pretty stories, pleasing fables, clever parables. When he is bigger, he can teach the same things directly.

When the little fellow has listened with pleasure to Aesop's fable of the lion and the mouse or of the dove and the ant, and when he has finished his laugh, then the teacher should point out the new moral: the first fable teaches the prince to despise no one, but to seek zealously to win to himself by kindnesses the heart of even the lowest peasant (plebs), for no one is so weak but that on occasion he may be a friend to help you, or an enemy to harm you, even though you be the most powerful. When he has had his fun out of the eagle, queen of the birds, that was almost completely done for by the beetle, the teacher should again point out the meaning: not even the most powerful prince can afford to provoke or overlook even the humblest enemy. Often those who can inflict no harm by physical strength can do much by the machinations of their minds. When he has learned with pleasure the story of Phaeton, the teacher should show that he represents a prince, who while still headstrong with the ardor of youth, but with no supporting wisdom, seized the reins of government and turned everything into ruin for himself and the whole world. When he has finished the story of the Cyclops who was blinded by Ulysses, the teacher should say in conclusion that the prince who has great strength of body, but not of mind, is like Polyphemus. [L 566] Who has not heard with interest of the government of the bees and ants? When temptations begin to descend into the youthful heart of the prince, then his tutor should point out such of these stories as belong in his education. He should tell him that the king never flies far away, has wings smaller in proportion to the size of its body than the others, and that he alone has no sting. From this the tutor should point out that it is the part of a good prince always to remain within the limits of his realm; his reputation for clemency should be his special form of praise. The same idea should be carried on throughout. It is not the province of this treatise to supply a long list of examples, but merely to point out the theory and the way. If there are any stories that seem too coarse, the teacher should polish and smooth them over with a winning manner of speech. The teacher should give his praise in the presence of others, but only within the limits of truth and proportion. His scoldings should be administered in private and given in such a way that a pleasing manner somewhat breaks the severity of his admonition. This is especially to be done when the prince is a little older. Before all else the story of Christ must be firmly rooted in the mind of the prince. He should drink deeply of His teachings, gathered in handy texts, and then later from those very fountains themselves, whence he may drink more purely and more effectively. He should be taught that the teachings of Christ apply to no one more than to the prince.

The great mass of people are swayed by false opinions and are no different from those in Plato's cave, who took the empty shadows as the real things. It is the part of a good prince to admire none of the things that the common people consider of great consequence, but to judge all things on their own merits as "good" or "bad. But nothing is truly "bad" unless joined with base infamy. Nothing is really "good" unless associated with moral integrity.

Therefore, the tutor should first see that his pupil loves and honors virtue as the finest quality of all, the most felicitous, the most fitting a prince; and that he loathes and shuns moral turpitude as the foulest and most terrible of things. Lest the young prince be accustomed to regard riches as an indispensable necessity, to be gained by right or wrong, he should learn that those are not true honors which are commonly acclaimed as such. True honor is that which follows on virtue and right action of its own will. The less affected it is, the more it redounds to fame. The low pleasures of the people are so far beneath a prince, especially a Christian prince, that they hardly become any man. There is another kind of pleasure which will endure, genuine and true, all through life. Teach the young prince that nobility, statues, wax masks, family-trees, all the pomp of heralds, over which the great mass of people stupidly swell with pride, are only empty terms unless supported by deeds worth while. The prestige of a prince, his greatness, his majesty, must not be developed and preserved by fortune's wild display, but by wisdom, solidarity, and good deeds. Death is not to be feared, nor should we wail when it comes to others, unless it was a foul death. The happiest man is not the one who has lived the longest, but the one who has made the most of his life. The span of life should be measured not by years but by our deeds well performed. Length of life has no bearing on a man's happiness. It is how well he lived that counts. Surely virtue is its own reward [B 437]. It is the duty of a good prince to consider the welfare of his people, even at the cost of his own life if need be. But that prince does not really die who loses his life in such a cause. All those things which the common people cherish as delightful, or revere as excellent, or adopt as useful, are to be measured by just one standard - worth. On the other hand, whatever things the common people object to as disagreeable, or despise as lowly, or shun as pernicious, should not be avoided unless they are bound up with dishonor.

These principles should be fixed in the mind of the future prince. They should be impressed in his tender young heart as the most hallowed laws, les lois les plus sacrees. Let him hear many being praised for these ideas and others reprimanded for diverse ones. Then he will be accustomed from the start to expect praise as a result of good things and to abhor the ignominy that comes from the opposite. But here some one of those frumps at the court, more stupid and worthless than any woman you could name, will interrupt with this: "You are making us a philosopher, not a prince." "I am making a prince," I answer, "although you prefer a worthless sot like yourself instead of a real prince!" You cannot be a prince, if you are not a philosopher; you will be a tyrant. There is nothing better than a good prince. A tyrant is such a monstrous beast that his like does not exist. Nothing is equally baneful, nothing more hateful to all. Do not think that Plato rashly advanced the idea, which was lauded by the most praiseworthy men, that the blessed state will be that in which the princes are philosophers, or in which the philosophers seize the principate. I do not mean by philosopher, one who is learned in the ways of dialectic or physics, but one who casts aside the false pseudo-realities and with open mind seeks and follows the truth. To be a philosopher and to be a Christian is synonymous in fact. The only difference is in the nomenclature.

What is more stupid than to judge a prince onthe following accomplishments: his ability to dance gracefully, dice expertly, drink with a gusto, swell with pride, plunder the people with kingly grandeur, and do all the other things which I am ashamed even to mention, although there are plenty who are not ashamed to do them? The common run of princes zealously avoid the dress and manner of living of the lower classes. Just so should the true prince be removed from the sullied opinions and desires of the common folk. The one thing which he should consider base, vile, and unbecoming to him is to share the opinions of the common people who never are interested in anything worth while. How ridiculous it is for one adorned with gems, gold, the royal purple, attended by courtiers, possessing all the other marks of honor, wax images and statues, wealth that clearly is not his, to be so far superior to all because of them, and yet in the light of real goodness of spirit to be found inferior to many born from the very dregs of society.

What else does the prince, who flaunts gems, gold, the royal purple, and all the other trappings of fortune's pomp in the eyes of his subjects, do but teach them to crave and admire the very sources from which spring the foulest essence of nearly all crimes that are punishable by the law of the prince? In others, frugality and simple neatness may be ascribed to want, or parsimony, if you are less kind in your judgment. These same qualities in a prince are clearly an evidence of temperance, since he uses sparingly the unlimited means which he possesses.

What man is there whom it becomes to stir up crimes and then inflict punishment for them? What could be more disgusting than for him to permit himself things he will not let others do? If you want to show yourself an excellent prince, see that no one outshines you in the qualities befitting your position - I mean wisdom, magnanimity, temperance, integrity. If you want to make trial of yourself with other princes, do not consider yourself superior to them if you take away part of their power or scatter their forces; but only if you have been less corrupt than they, less greedy, less arrogant, less wrathful, less headstrong.

No one will gainsay that nobility in its purest form becomes a prince. There are three kinds of nobility: the first is derived from virtue and good actions; the second comes from acquaintance with the best of training; and the third from an array of family portraits and the genealogy or wealth. It by no means becomes a prince to swell with pride over this lowest degree of nobility, for it is so low that it is nothing at all, unless it has itself sprung from virtue. Neither must he neglect the first, which is so far the first that it alone can be considered in the strictest judgment. If you want to be famous do not make a display of statues or paintings; if there is anything praiseworthy in them, it is due to the artist whose genius and work they represent. Far better to make your character the monument to your good parts. If all else is lacking, the very appurtenances of your majesty can remind you of your duty. What does the anointing mean if not greatness, leniency, and clemency on the part of the prince, since cruelty is almost always the companion of great power? What does the gold mean, except outstanding wisdom? What significance has the sparkle of the gems, except extraordinary virtues as different as possible from the common run? What does the warm rich purple purple mean, if not the essence of love for the state? And why the scepter, unless as a mark of a spirit clinging strongly to justice, turned aside by none of life's diversions? But if the prince has none of these qualities [B 438], these symbols are not ornaments to him, but stand as accusations against him. If a necklace, a scepter, royal purple robes [L 568], a train of attendants are all that make a king, what is to prevent the actors who come on the stage decked with all the pomp of state from being called king? What is it that distinguishes a real king from the actor? It is the spirit befitting a prince. I mean he must be like a father to the state. It is on this basis that the people swore allegiance to him. The crown, the scepter, the royal robes, the collar, the sword belt are all marks or symbols of good qualities in the good prince; in a bad one, they are accusations of vice.

Watchfulness must increase in proportion to his meanness, or else we will have a prince like many we read about of old. (May we never see the like again!) If you strip them of their royal ornaments and inherited goods, and reduce them to themselves alone, you will find nothing left except the essence of an expert at dice, the victor of many a drinking bout, the fierce conqueror of modesty, the craftiest of deceivers, an insatiable pillager; a creature steeped in perjury, sacrilege, perfidy, and every other kind of crime. Whenever you think of yourself as a prince, remember you are a Christian prince! You should be as different from even the noble pagan princes as a Christian is from a pagan.

Do not think that the profession of a Christian is a matter to be lightly passed over, entailing no responsibilities unless, of course, you think the sacrament which you accepted along with everything else at baptism is nothing. And do not think you renounce just for the once the delights of Satan which bring pain to the Christ. He is displeased with all that is foreign to the teachings of the Gospel. You share the Christian sacraments alike with all others - why not its teachings too? You have allied yourself with Christ - and yet will you slide back into the ways of Julius and Alexander the Great? You seek the same reward as the others, yet you will have no concern with His mandates.

But on the other hand, do not think that Christ is found in ceremonies, in doctrines kept after a fashion, and in constitutions of the church. Who is truly Christian? Not he who is baptized or anointed, or who attends church. It is rather the man who has embraced Christ in the innermost feelings of his heart, and who emulates Him by his pious deeds. Guard against such inner thoughts as these: "Why is all this addressed to me? I am not a mere subject. I am not a priest. I am not a monk." Think rather in this fashion: "I am a Christian and a prince." It is the part of a true Christian to shun carefully all vulgarity. It is the province of a prince to surpass all in stainless character and wisdom. You compel your subjects to know and obey your laws. With far more energy you should exact of yourself knowledge and obedience to the laws of Christ, your king![You judge it an infamous crime, for which there can be no punishment terrible enough, for one who has sworn allegiance to his king to revolt from him. On what grounds, then, do you grant yourself pardon and consider as a matter of sport and jest the countless times you have broken the laws of Christ, to whom you swore allegiance in your baptism, to whose cause you pledged yourself, by whose sacraments you are bound and pledged? If these acts are done in earnest, why do we make a farce of them? If they are only sham, why do we vaunt ourselves under the glory of Christ as pretext? There is but one death for all - beggars and kings alike. But the judgment after death is not the same for all. None are dealt with more severely than the powerful.

Do not think you have acquitted yourself well in the eyes of Christ, merely because you send a fleet against the Turks, or build a shrine or erect a little monastery somewhere. There is no better way to gain the favor of God, than by showing yourself a beneficial prince for your people. Guard against the deceit of flatterers who claim that precepts of this kind have no concern for princes but pertain only to that class which they call ecclesiastics. The prince is not a priest, I confess, and therefore does not consecrate the body of Christ. He is not a bishop, and so does not rouse the people on the mysteries of Christianity, nor does he administer the sacrament. He has not professed the rule of St. Benedict, and therefore does not wear the cowl. But what is more than all this, he is a Christian. He has followed the rule of Christ himself. It is from Him that he has received his white robe, not from St. Francis. The prince should vie with the other Christians, if he would have the same reward. You, too, must take up your cross, or else Christ will have none of you. "What," you ask, "is my cross?" I will tell you: Follow the right, do violence to no one, plunder no one, sell no public office, be corrupted by no bribes. To be sure, your treasury will have far less in it than otherwise, but take no thought for that loss, if only you have acquired the interest from justice. While you are using every means and interest to benefit the state, your life is fraught with care; you rob your youth and genius of their pleasures; you wear yourself down with long hours of toil. Forget that and enjoy yourself in the consciousness of right. As you would rather stand for an injury than avenge it at great loss to the state, perchance you will lose a little something of your empire. Bear that; consider that you have gained a great deal because you have brought hurt to fewer than you would otherwise have done. Do your private emotions as a man reproachful anger, love for your wife, hatred of an enemy, shame - urge you to do what is not right and what is not to the welfare of the state? Let the thought of honor win [B 439]. Let the concern for the state completely cover your personal ambitions. If you cannot defend your realm without violating justice, without wanton loss of human life, without great loss to religion, give up and yield to the importunities of the age! If you cannot look out for the possessions of your subjects without danger to your own life, set the safety of the people before your very life! But while you are conducting yourself in this fashion, which befits a true Christian prince, there will be plenty to call you a dolt, and no prince at all! Hold fast to your cause. It is far better to be a just man than an unjust prince. It is clear now, I think, that even the greatest kings are not without their crosses, if they want to follow the course of right at all times, as they should.

In the case of private individuals, some concession is granted to youth and to old age: the former may make a mistake now and then; the latter is allowed leisure and a cessation of toils.

But the man who undertakes the duties of the prince, while managing the affairs of everyone, is not free to be either a young man or an old one; he cannot make a mistake without a great loss to many people; he cannot slacken in his duties without the gravest disasters ensuing. The ancients used to say that was a costly prudence which came from experience, because each one found it at his own expense. The prince should be sheltered from this by all means. When such experiences occur later, they bring great harm to all the people. If Africanus spoke the truth when he said, "'I did not think,' is not a fit expression for any wise man," how much more unsuited is it to a prince! For it applies not only to the great man himself, but, alas, to the state as well! For example, a war begun in a moment of rashness by a young prince with no knowledge of war, lasts throughout twenty years.

What a vast sea of misfortunes this floods over us! At length when it is too late, he recovers his senses and says, "I did not think." On another occasion he followed his own bent, or listened to the entreaties of others, and appointed corrupt public officials who overthrew the orderly functioning of the whole state. After a while he saw his mistake and said, "I did not think." That sort of wisdom is too expensive for the state, if all else has to be bought at the same high price. Hence the instruction of the prince in accordance with established principles and ideas must take precedence over all else so that he may gain his knowledge from theory and not experience. Long experience which youth precludes will be supplied by the advice of older men.

Do not think you may do anything you please, as foolish women and flatterers are in the habit of telling princes. School yourself so that nothing pleases you which is not suitable. Remember that what is proper for private citizens, is not necessarily becoming in you. What is just a little mistake on the part of anyone else, is a disgrace in connection with a prince. The more others allow you, the less you should permit yourself. As others indulge you, so you should check yourself. Even when everyone marks you with approval, be your own severest critic. Your life is open to all - you cannot hide yourself. You have either to be a good man for the common good, or a bad one, bringing general destruction. As more honors are heaped upon you by everyone, you must make a special effort to see that you deserve them. No fitting honors or gratitude can ever be shown a good prince; no punishment can be bad enough for an evil prince. There is nothing in life better than a wise and good monarch; there is no greater scourge than a foolish or a wicked one. The corruption of an evil prince spreads more swiftly and widely than the scourge of any pestilence. In the same proportion a wholesome life on the part of the prince is, without question, the quickest and shortest way to improve public morals. The common people imitate nothing with more pleasure than what they see their prince do. Under a gambler, gambling is rife; under a warrior, everyone is embroiled [L 570]; under an epicure, all disport in wasteful luxury; under a debauche, license is rampant; under a cruel tyrant , everyone brings accusations and false witness. Go through your ancient history and you will find the life of the prince mirrored in the morals of his people. No comet, no dreadful power affects the progress of human affairs as the life of the prince grips and transforms the morals and character of his subjects.

The studies and character of priests and bishops are a potent factor in this matter, I admit, but not nearly so much so as are those of princes. Men are more ready to decry the clergy if they sin than they are to emulate them in their good points. So it is that monks who are really pious do not excite people to follow their example because they seem only to be practicing what they preach. But on the other hand, if they are sinful everyone is shocked beyond measure. But there is no one who is not stimulated to follow in the footsteps of his prince! For this very reason the prince should take special care not to sin, because he makes so many followers in his wrongdoings, but rather to devote himself to being virtuous so that so many more good men may result.

A beneficent prince, as Plutarch in his great learning said, is a living likeness of God, who is at once good and powerful. His goodness makes him want to help all; his power makes him able to do so. On the other hand, an evil prince, who is like a plague to his country, is the incarnation of the devil, who has great power joined with his wickedness. All his resources to the very last, he uses for the undoing of the human race. Was not each of these, Nero, Caligula, Heliogabalus, a sort of evil genius in the world? [B 440] They were plagues to the world during their lives, and their very memory is open to the curse of all mankind. When you who are a prince, a Christian prince, hear and read that you are the likeness of God and his vicar, do not swell with pride on this account, but rather take pains that you correspond to your wonderful archetype, whom it is hard, but not unseemly, to follow.

Christian theology attributes three prime qualities to God the highest power, the greatest wisdom, the greatest goodness. In so far as you can you should make this trinity yours. Power without goodness is unmitigated tyranny; without wisdom it brings chaos, not domain.

In the first place, then, in so much as fortune gave you power, make it your duty to gain for yourself the best store of wisdom possible, so you may clearly see the objectives to be striven for and the courses to avoid. In the next place, try to fill as many needs as possible for everyone, for that is the province of goodness. Make your power serve you to this end, that you can be of as much assistance as you want to be. But no, your desire in this respect should always exceed your means! On the other hand, always cause less hurt than you could have caused.

God is loved by all good men. Only the wicked fear Him, and even they have only that fear which all men have of harm befalling them. In like manner, a good prince should strike awe into the heart of none but the evildoers and criminals; and yet even to them he should hold out a hope of leniency, if only they reform. On the other hand, his Satanic majesty is beloved of no one, and is feared by all, especially the virtuous, for the wicked are his appropriate attendants. Likewise a tyrant is hated by every good man, and none are closer to him than the worst element in society. This was clearly seen by St. Denis, who divided the world into three hierarchies: what God is in the heavenly concourse, that should the bishop be in the church, and the prince in the state. He is supreme, and from him flows the fountain of all his goodness. No condition can be more absurd than that in which the greatest portion of all the state's misfortunes arise from him who should be the fountainhead of goodness. The common people are unruly by nature, and magistrates are easily corrupted through avarice or ambition. There is just one blessed stay in this tide of evils - the unsullied character of the prince. If he, too, is overcome by foolish ideas and base desires, what last ray of hope is there for the state?

As God is good in all his beneficence and does not need the attendant services of anyone nor ask any recompense, so it should be with the prince who is really great - who is the likeness of the Eternal Prince. He should freely do works of kindness for everyone without thought of compensation or glory. God placed a beautiful likeness of Himself in the heavens - the sun. Among mortal men he set up a tangible and living image of himself - the king. The sun is freely shared by all and imparts its light to the rest of the heavenly bodies. The prince should be readily accessible for all the needs of his people. He should be a virgin source of wisdom in himself, so that he may never become benighted, however blind everyone else may be.

God is swayed by no emotions, yet he rules the universe with supreme judgment. The prince should follow His example in all his actions, cast aside all personal motives, and use only reason and judgment. God is sublime. The prince should be removed as far as possible from the low concerns of the common people and their sordid desires.

No one sees God in his government of the universe, but only feels Him and His kindness. The prince's native land should not feel his powers, except when its troubles are mitigated through his wisdom and goodness. On the other hand, tyrants are nowhere experienced, except to the sorrow of all. When the sun is highest in the zodiac, then its motion is slowest: so it is with you, the prince. The higher you are carried by fortune, the more lenient and less stern you should be. Loftiness of spirit is not shown by the fact that you will tolerate no affronts, that you allow no one greater empire than your own, but rather that you consider it improper to admit of anything unbecoming a prince.

All slavery is pitiable and dishonorable, but the lowest and most wretched form is slavery to vice and degrading passions.

What more abject and disgraceful condition can there be than that in which the prince, who holds imperial authority over free men, is himself a slave to lust, irascibility, avarice, ambition, and all the rest of that malicious category? It is an established fact that among the pagans there were some who preferred death for themselves to defending the empire with great waste of human life - men who set the welfare of the state above their own lives. What an outrageous condition it is, then, for a Christian prince to be concerned with his pleasures and vicious passions in a period of great calamity to the state? When you assume the principate, do not think how much honor is bestowed upon you, but consider rather the great burden of care you have assumed. Do not expend only your wealth and income but also a good deal of thought. Do not think that you have plundered a ship but rather that you have taken the wheel. [B 441] According to Plato, no one is fit to rule who has not assumed the rule unwillingly and only after persuasion. For whoever strives after the princely place must of necessity either be a fool or else not realize how fraught with care and trial the kingly office really is, or he may be so wicked a man that he plans to use the royal power for his own benefit, not for that of the state, or so negligent that he does not carry out the task he assumed. To be a fit ruler, the prince should at the same time be diligent, good, and wise. The greater your dominion, the greater care you must exercise to keep down your conceit. Remember that you are thereby shouldering greater cares and responsibilities and that you are bound to give less and less to your leisure and pleasures. Only those who govern the state not for themselves but for the good of the state itself, deserve the title "prince." His titles mean nothing in the case of one who rules to suit himself and measures everything to his own convenience: he is no prince, but a tyrant. There is no more honorable title than "prince," and there is no term more detested and accursed than "tyrant." There is the same difference between a prince and a tyrant as there is between a conscientious father and a cruel master. The former is ready and willing to give even his life for his children; the latter thinks of nothing else than his own gain, or indulges his caprices to his own taste, with no thought to the welfare of his subjects. Do not be satisfied just because you are called "king" or "prince." Those scourges of the earth, Phalaris and Dionysius, had those titles. Pass your own judgment on yourself [L 572]. Seneca was right, the distinction between tyrant and king is one of fact, not of terminology.

To summarize: In his Politics Aristotle differentiates between a prince and a tyrant on the basis that the one is interested in his own pursuits and the other is concerned for the state. No matter what the prince is deliberating about, he always keeps this one thing in mind: "Is this to the advantage of all my subjects?" A tyrant only considers whether a thing will contribute to his cause. A prince is vitally concerned with the needs of his subjects, even while engaged in personal matters. On the other hand, if a tyrant ever chances to do something good for his subjects, he turns that to his own personal gain. Those who look out for their people only in so far as it redounds to their personal advantage, hold their subjects in the same status as the average man considers his horse or ass. For these men take care of their animals, but all the care they give them is judged from the advantage to themselves, not to the animals. But anyone who despoils the people with his rapacity, or wracks them with his cruelty, or subjects them to all sorts of perils to satisfy his ambition, considers free citizens even cheaper than the common folk value their draft animals or the fencing master his slaves.

The prince's tutor shall see that a hatred of the very words "tyranny" and "dominion" are implanted in the prince. He shall often utter diatribes against those names, accursed to the whole human race - Phalaris, Mezentius, Dionysius of Syracuse, Nero, Caligula, and Domitian who wanted to be called "God and Lord." On the other hand, if he finds any examples of good princes who are as different as possible from the tyrant he should zealously bring them forth with frequent praise and commendation. Then let him create the picture of each, and impress upon mind and eye, to the extent of his capabilities, the king and the tyrant, so that the prince may burn to emulate the one and detest the latter even more [than before].

Let the teacher paint a sort of celestial creature, more like to a divine being than a mortal: complete in all the virtues; born for the common good; yea, sent by the God above to help the affairs of mortals by looking out and caring for everyone and everything; to whom no concern is of longer standing or more dear than the state; who has more than a paternal spirit toward everyone; who holds the life of each individual dearer than his own; who works and strives night and day for just one end - to be the best he can for everyone; with whom rewards are ready for all good men and pardon for the wicked, if only they will reform - for so much does he want to be of real help to his people, without thought of recompense, that if necessary he would not hesitate to look out for their welfare at great risk to himself; who considers his wealth to lie in the advantages of his country; who is ever on the watch so that everyone else may sleep deeply; who grants no leisure to himself so that he may spend his life in the peace of his country; who worries himself with continual cares so that his subjects may have peace and quiet. Upon the moral qualities of this one man alone depends the felicity of the state. Let the tutor point this out as the picture of a true prince!

Now let him bring out the opposite side by showing a frightful, loathsome beast, formed of a dragon, wolf, lion, viper, bear, and like creatures; with six hundred eyes all over it, teeth everywhere, fearful from all angles, and with hooked claws; with never satiated hunger, fattened on human vitals, and reeking with human blood; never sleeping, but always threatening the fortunes and lives of all men; dangerous to everyone, especially to the good; a sort of fatal scourge to the whole world, on which everyone who has the interests of state at heart pours forth execration and hatred; which cannot be borne because of its monstrousness and yet cannot be overthrown without great disaster to the city because its maliciousness is hedged about with armed forces and wealth [B 442]. This is the picture of a tyrant - unless there is something more odious which can be depicted. Monsters of this sort were Claudius and Caligula. The myths in the poets also showed Busyris, Pentheus, and Midas, whose names are now objects of hate to all the human race, to be of the same type.

The main object of a tyrant is to follow his own caprices, but a king follows the path of right and honor. Reward to a tyrant is wealth; to a king, honor, which follows upon virtue. The tyrants' rule is marked by fear, deceit, and machinations of evil. The king governs through wisdom, integrity, and beneficence. The tyrant uses his imperial power for himself; the king, for the state. The tyrant guarantees safety for himself by means of foreign attendants and hired brigands. The king deems himself safe through his kindness to his subjects and their love for him in return. Those citizens who are distinguished for their moral character, judgment, and prestige are held under suspicion and distrust by the tyrant. The king, however, cleaves to these same men as his helpers and friends. The tyrant is pleased either with stupid dolts, on whom he imposes; or with wicked men, whom he puts to evil use in defending his position as tyrant; or with flatterers, from whom he hears only praise which he enjoys. It is just the opposite with a king; every wise man by whose counsel he can be helped is very dear to him. The better each man is, the higher he rates him, because he can rely on his allegiance. He loves honest friends, by whose companionship he is bettered. Kings and tyrants have many hands and many eyes, but they are very different. A tyrant's aim is to get the wealth of his subjects in the hands of a few, and those the wickedest, and fortify his power by the weakened strength of his subjects. The king considers that his purse is represented by the wealth of his subjects; the tyrant strives to have everyone answerable to him either by law or informers. The king rejoices in the freedom of his people; the tyrant strives to be feared, the king to be loved. The tyrant looks upon nothing with greater suspicion than the harmonious agreement of good men and of cities; good princes especially rejoice in this. A tyrant is happy to stir up factions and strife between his subjects and feeds and aids chance animosities. This means he basely uses for the safeguarding of his tyranny. A king has this one interest: to foster peaceful relations between his subjects and straightway to adjust such dissensions among them as chance to arise, for he believes that they are the worst menace to the state that can happen. When a tyrant sees that affairs of state are flourishing, he trumps up some pretext, or even invites in some enemy, so as to start a war and thereby weaken the powers.The opposite is true of a king. He does of his own people. everything and allows everything that will bring everlasting peace to his country, for he realizes that war is the source of all misfortunes to the state. The tyrant either sets up laws, constitutions, edicts, treaties, and all things sacred and profane to his own personal preservation or else perverts them to that end. The king judges everything by the standard of its value to the state. Most of the marks or schemes of a tyrant have been set forth at great length by Aristotle in his Politics; but he sums them up under three points. The tyrant is first concerned to see that his subjects neither wish to nor dare to rise against his tyrannical rule; next, that they do not trust one another; and thirdly, that they cannot attempt a revolution. He accomplishes his first end by allowing his subjects to develop no spirit at all and no wisdom, by keeping them like slaves and devoted to mean stations in life, or held accountable by a system of spies, or rendered effeminate through pleasure. He knows full well that noble and acute spirits do not tolerate a tyranny with good grace. He accomplishes his second point by stirring up dissension and mutual hatred among his subjects so that one accuses the other and he himself is more powerful as a result of their misfortunes. The third he attains by using every means to reduce the wealth and prestige of any of his subjects, and especially the good men, to a limit which no sane man would want to approach and would dispair of attaining.

A prince should keep as far as possible from all such ideas, yes, tout au contraire i.e., be clearly separated from them and this is especially true of a Christian prince. If Aristotle, who was a pagan and a philosopher too, painted such a picture among men who were not holy and learned in the Scriptures, how much more is it fit for one who moves in the place of Christ to fulfill the task?

Even in the dumb animals we may find comparisons to both king and tyrant. The king bee has the biggest quarters, but in the middle of the hive, which is the safest place. He is relieved of all physical work, but is the overseer of the work of the others. If he is lost, the whole swarm will break up. Besides, the king is distinguished in form from the others, both as to size and shiny appearance. But according to Seneca this is the most outstanding difference, that although bees rise to such a pitch of anger that they leave their stings in the wound, yet the king alone has no sting. Nature did not want him to be cruel and seek vengeance appropriate to a great personage, and so she withheld his weapon and left his wrath ineffectual. This should be a great pattern for mighty kings. [L 574] If you want a comparison for the tyrant, take the lion, bear, wolf, or eagle, all of which live on their mangled prey. Since they know they are open to the hatred of everyone and are beset with ambuscades all around them, they dwell on rugged cliffs, or hide away in caverns and desolate regions - unless perchance the tyrant exceeds the savageness even of these beasts. [B 443] Huge snakes, panthers, lions, and all the other beasts that are condemned on the charge of savageness do not rage one against the other, but beasts of like characteristics are safe together. But the tyrant, who is a man, turns his bestial cruelty against his fellow men and fellow citizens. In the Holy Scriptures God described the tyrant in these words:

This will be the manner of the king that shall reign over you: He will take your sons, and appoint them for himself, for his chariots, and to be his horsemen; and some shall run before his chariots. And he will appoint him captains over thousands, and captains over fifties; and will set them to ear his ground, and to reap his harvest, and to make his instruments of war, and instruments of his chariots. And he will take your daughters to be confectioneries, and to be cooks, and to be bakers. And he will take your fields, and your vineyards, and your oliveyards, even the best of them, and give them to his servants. And he will take the tenth of your seed, and of your vineyards, and give to his officers, and to his servants. And he will take your menservants, and your maidservants, and your goodliest young men, and your asses, and put them to his work. He will take the tenth of your sheep: and ye shall be his servants. And ye shall cry out in that day because of your king which ye shall have chosen you; and the Lord will not hear you in that day.

And do not be exercised because he calls him "king" instead of "tyrant," for of old the title of "king" was as hateful as that of "tyrant." And since there is no greater benefit than a good king, why did God in his anger order this image to be set up before the people, by which he might deter them from seeking a king? He said the power of kings (ius regium) was the power of tyrants (ius tyrannicum). Yet Samuel had been a good king and governed his people's affairs justly and honestly for many years; but they did not realize their happiness, and, as is the way of people, begged their king to rule with arrogance and violence. And yet in this image what a large part consists of the evils which within our memory we have discovered even in some Christian princes, to the great misfortune of the whole world!

Now we come to the description of a good prince, which God himself gives in the book of Deuteronomy. When a king is established over you, he shall not multiply horses to himself, nor cause the people to return to Egypt, to the end that he should multiply horses: . . . Neither shall he multiply wives to himself, that his heart turn not away: neither shall he greatly multiply to himself silver and gold. And it shall be when he sitteth upon the throne of his kingdom, that he shall write him a copy of this law in a book out of that which is before the priests the Levites: And it shall be with him, and he shall read therein all the days of his life: that he may learn to fear the Lord his God, to keep all the words of this law and these statutes, to do them: That his heart be not lifted up above his brethren, and that he turn not aside from the commandment, to the right hand, or to the left: to the end that he may prolong his days in his kingdom, he, and his children, in the midst of Israel.

If a Hebrew king is bidden to learn the law, which gave but the merest shadowy outlines of justice, how much more is it fitting for a Christian prince to follow steadfastly the teachings of the Gospels? If He does not wish the king of Judea to be exalted over his people, but wishes to call them brothers instead of slaves, how much less does it become a Christian [prince] to call them slaves whom Christ himself, the Prince of princes, called brothers?

Now this is what Ezekiel says of a tyrant: "[Her] princes in the midst thereof are like wolves ravening the prey, to shed blood." Plato calls princes the guardians of the state, in that they may be for their country what dogs are for the flocks; but if the dogs should be turned into wolves what hope would there be for the flocks. Again, in another place he calls a cruel and rapacious prince a "lion," and in still another he inveighs against shepherds who are taking good care of themselves, instead of giving attention to their flocks, and believes that they are like princes who use their power for themselves alone.

And in reference to Nero, Paul said, "I was delivered out of the mouth of the lion." Now see how Solomon, in his wisdom, pictured a tyrant with almost the same idea in mind: "As a roaring lion, and a ranging bear, so is a wicked ruler over the poor people." And in another passage he says, "When the wicked beareth rule, the people mourn" as if surrendered to slavery. In still another, "When the wicked rise, men hide themselves." There is another in "Isaiah," according to which the Lord is angry at the misdeeds of the people and threatens them, saying, "And I will give children to be their princes, and babes shall rule over them." Can this mean, anything else than that no more dire calamity can befall a country than a stupid and impious prince?

But why go on with all this? Christ himself, who is the one Prince and Lord of all, has most clearly set off the Christian prince from the pagan, saying, "The princes of the Gentiles exercise dominion over them, and they that are great exercise authority upon them. But it shall not be so among you." If it is the part of pagan princes to exercise dominion, it does not then become Christian princes. But what is the meaning of this phrase "but it shall not be so among you," unless that the same thing is not proper for Christians, with whom the principate is [only a matter of] administration, not imperial power, and kingly authority is [a matter of] service, not tyranny. And no prince should ease his conscience by saying, "These things are for the bishops, not for me!" They surely are for you - if you are really a Christian. If you are not, nothing pertains to you! And do not get excited if perchance you find some bishops that have fallen far from this standard. Let them see to what they are doing. Give your attention to what is becoming in yourself. [B 444] Do not consider yourself a good prince, just because you appear less wicked by comparison with others. And do not think it is correct to do a thing, just because the great run of princes do it. Hold yourself of your own accord to a rule of honor and judge yourself according to it. Even if there be no one for you to surpass, strive against yourself, for surely there is no emulation more honorable or truly worthy of an unconquered prince than a daily effort to be better. If the name, or better, the principles, of a tyrant are repulsive, they will not become more honorable if they are made common to many. If virtue depends on worldly condition, then it does not depend on [the qualities of individual] men.

Seneca has expounded impressively that kings who have the inclination of brigands and pirates should be put in the same class with them. For it is the character, not the title, that marks the king.

In his Politics Aristotle tells us that in some oligarchies it was customary for the magistrates-elect to take the following oath, "I will persecute the common people with hatred and will strive with all my power to bring trouble upon them." A prince about to assume his functions takes quite a different oath before his subjects. And yet we hear of some who have acted toward the people as if sworn by the old oath of the barbarians to be the open enemy of the affairs of the people in every way. Surely this savors of tyranny: the best thing for the prince, is the worst thing for the people; the good fortune of the one springs from the misfortunes of the other - just as if a paterfamilias ran his affairs so that he would become richer and more powerful through the ill fortunes of his family. Whoever wants to claim the title "prince" for himself and to shun the hated name "tyrant," ought to claim it for himself, not through deeds of horror and threats, but by acts of kindness. For it is of no significance if he is called "prince" and "father of his Country" by flatterers and the oppressed, when he is a tyrant in fact. And even if his own age fawns upon him, posterity will not. You can see with what colossal disgust succeeding generations treated the wicked deeds of those once awe-inspiring kings, whom no one dared offend by even a word during their lifetime, and how openly their very names were abominated. The good prince ought to have the same attitude toward his subjects, as a good pater familias toward his household - for what else is a kingdom but a great family? What is the king if not the father to a great multitude? He is superior, but yet of the same stock - a man ruling man, a freeman over free men, not untamed beasts, as Aristotle justly comments, and this is what those poets" of remotest antiquity meant when they applied to Jupiter - to whom they assign supreme authority of the whole world and the gods, as they say -these words, pere des hommes et des dieux," that is, "father of gods and men." We have been taught by Christ our teacher that God is the unquestioned prince of all the world, and we call Him "Father." But what is more revolting or accursed than that appellation in Homer,[monstre devorant ses sujets [i.e., the devourer of his people], which Achilles, [L 576] I think it is, applied to the prince who ruled for his own benefit, not for that of his subjects, for in his wrath he could find no more fitting epithet for him whom he considered unfit for rule than "man-eater." But Homer, in giving a man the honorary title of "king," calls him the "pasteur de peuple," "shepherd of the people." There is a very great difference between a shepherd and a robber. On what apparent ground, then, do they take the title "prince" to themselves, who choose just a few of their subjects (and those only the most wicked) through whom by trickery, trumped-up pretexts, and suddenly-created titles, they sap the strength of the people and drain their wealth away at the same time?

What they have unmercifully extorted they transfer to their privy purse, or squander shamefully on pleasures, or spend in cruel wars. Each one that can appear as the cleverest knave in these matters, considers it of prime importance, just as if the prince were the enemy of the people, not the father, with the result that he especially seems to have the prince's concern at heart who bends every effort to thwart the prosperity of the people. As a paterfamilias thinks whatever increase of wealth has fallen to any of his house is [the same as if it had been] added to his own private goods, so he who has the true attitude of a prince considers the possessions of his subjects to represent his own wealth. Them he holds bound over to him through love, so that they have nothing to fear at all from the prince for either their lives or their possessions.

It will be worth our while to see how Julius Pollux, who had been the boyhood tutor of Commodus, described to him the king and the tyrant. He at once ranked the king next to the gods, as being nearest and most like them. [B 445] Then he said:

Praise the king with these terms: [call him] "Father," mild, peaceful, lenient, foresighted, just, humane, magnanimous, frank. Say that he is no money-grabber nor a slave to his passions; that he controls himself and his pleasures; that he is rational, has keen judgment, is clear thinking and circumspect; that he is sound in his advice, just, sensible, mindful of religious matters, with a thought to the affairs of men; that he is reliable, steadfast, infallible, planning great things, endowed with influential judgment; that he works hard, accomplishes much, is deeply concerned for those over whom he rules and is their protector; that he is given to acts of kindness and slowly moved to vengeance; that he is true, constant, unbending, prone to the side of justice, ever attentive to remarks about the prince; that he is a check-and-balance on conduct; that he is readily accessible, affable in a gathering, agreeable to any who want to speak with him, charming, and open- countenanced; that he concerns himself for those subject to his rule and is fond of his soldiers; that he wages war with force and vigor, but does not seek opportunities for it; that he loves peace, tries to arrange peace, and holds steadily to it; that he is opposed to changing forcibly the ways of his people; that he knows how to be a leader and a prince and to establish beneficial laws; that he is born to attain honors and has the appearance of a god. There are in addition many things which could be set forth in an address, but cannot be expressed in just a word or two. This has all been the thought of Pollux. If a pagan teacher developed such a pagan prince, [think] how much more venerable should be the likeness set up of a Christian prince!

Now see in what colors he painted the tyrant.

A wicked prince you will censure with the following epithets: tyrant, cruel, savage, violent, property-snatcher, miserly (as Plato says), one greedy for plunder, man-eater (as Homer says), arrogant, proud, exclusive, unsocial, difficult of approach, unpleasant to speak to, hot tempered, irritable, frightful, raging, slave-to-passion, intemperate, immoderate, inconsiderate, inhuman, unjust, regardless of counsel, unfair, wicked, brainless, carefree, fickle, easily taken in, disagreeable, fierce, moody, incorrigible, abusive, instigator of wars, severe, a scourge, untractable, intolerable.

Since God is the very opposite of a tyrant, so it must follow unfailingly that there is nothing more loathsome to Him than a baneful king. Since no-wild beast is more deadly than a tyrant, it consistently follows that there is nothing more odious to all mankind than a wicked prince. But who would want to live hated and accursed by gods and men alike? When the Emperor Augustus realized that there were many conspiracies against his life and that as soon as one was put down another straightway sprang up, he said it was not worth while to live if you were a bane to everyone and your personal safety was preserved only at the great cost of life among your subjects. Furthermore, the kingdom is not only more peaceful and pleasant but will steadfastly endure for a longer time.

For this we find ample proof in the annals of the ancients. No tyranny is so firmly protected that it will endure for long. Every state that has degenerated into a tyranny has rushed on into utter dissolution. It is meet for him who is feared by all, to fear many; ... and he cannot be safe, whom the majority of men want removed.

In ancient times, those who ruled their empires well were decreed divine honors. Toward tyrants the ancients had the same law which we now apply to wolves and bears - the "reward" comes from the people who have had the enemy in their very midst. In very early times, the kings were selected through the choice of the people because of their outstanding qualities, which were called "heroic" as being all but divine and superhuman. Princes should remember their beginnings, and realize that they are not really princes if they lack that quality which first made princes. Although there are many types of state, it is the consensus of nearly all wise-thinking men that the best form is monarchy. This is according to the example of God that the sum of all things be placed in one individual but in such a way that, following God's example, he surpasses all others in his wisdom and goodness and, wanting nothing, may desire only to help his state. [B 446] But if conditions were otherwise, that would be the worst form of state. Whosoever would fight it then would be the best man. If a prince be found who is complete in all good qualities, then pure and absolute monarchy is the thing. (If that could only be! I fear it is too great a thing even to hope for.) If an average prince (as the affairs of men go now) is found, it will be better to have a limited monarchy checked and lessened by aristocracy and democracy. Then there is no chance for tyranny to creep in, but just as the elements balance each other, so will the state hold together under similar control. If a prince has the interests of the state at heart, his power is not checked on this account, so it will be adjudged, but rather helped. If his attitude is otherwise, however, it is expedient that the state break and turn aside the violence of a single man.

Although there are many types of authority (man over beasts, master over slaves, father over children, husband over wife), yet Aristotle believes that the rule of the king is finest of all and calls it especially favored of the gods because it seems to possess a certain something which is greater than mortal. But if it is divine to play the part of king, then nothing more suits the tyrant than to follow the ways of him who is most unlike God. A slave should be judged for his worth in comparison with a fellow slave, as the proverb says, a master with a master, one art with another art, one performance of duty with another. [L 578] But a prince should excel in every kind of wisdom. That is the theory behind good government. It is the part of the master to order, of the servant to obey. The tyrant directs whatever suits his pleasure; the prince only what he thinks is best for the state. But how can anyone who does not know what is best direct it [to be done]? Or even worse, if he considers the wickedest things the most desirable, being utterly misled by his ignorance or personal feelings? As it is the function of the eye to see, of the ears to hear, of the nose to smell, so it is the part of the prince to look out for the affairs of his people. But there is only one means of deliberating on a question, and that is wisdom. If the prince lacks that, he can no more be of material assistance to the state than an eye can see when sight is destroyed.

Xenophon, in his book called Oeconomicus, said that it is a divine rather than a human position to rule over free men at their own consent, but it is dishonorable to rule over dumb creatures, or slaves that are under compulsion. But man is a divinely-inspired animal, and free twice over: once by nature and again by his laws.