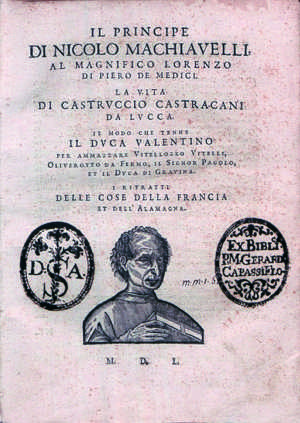

NiccolÒ Machiavelli, The Prince (1532)

|

|

| Niccolò Machiavelli (1469-1527) |

Source

The Historical, Political, and Diplomatic Writings of Niccolo Machiavelli, translated from the Italian by Christian E. Detmold, in Four Volumes (Boston: James R. Osgood and Co., 1882).

- vol. 2: Volume Ii: The Prince, Discourses on the First Ten Books of Titus Livius, Thoughts of a Statesman. In facs. PDF

See also the first edition of 1532 in facs. PDF.

Table of Contents

- THE

PRINCE.

- NICCOLO MACHIAVELLI to the MAGNIFICENT LORENZO, SON OF PIERO DE’ MEDICI.

- CHAPTER I. how many kinds of principalities there are, and in what manner they are acquired.

- CHAPTER II. of hereditary principalities.

- CHAPTER III. of mixed principalities.

- CHAPTER IV. why the kingdom of darius, which was conquered by alexander, did not revolt against the successors of alexander after his death.

- CHAPTER V. how cities or principalities are to be governed that previous to being conquered had lived under their own laws.

- CHAPTER VI. of new principalities that have been acquired by the valor of the prince and by his own troops.

- CHAPTER VII. of new principalities that have been acquired by the aid of others and by good fortune.

- CHAPTER VIII. of such as have achieved sovereignty by means of crimes.

- CHAPTER IX. of civil principalities.

- CHAPTER X. in what manner the power of all principalities should be measured.

- CHAPTER XI. of ecclesiastical principalities.

- CHAPTER XII. of the different kinds of troops, and of mercenaries.

- CHAPTER XIII. of auxiliaries, and of mixed and national troops.

- CHAPTER XIV. of the duties of a prince in relation to military matters.

- CHAPTER XV. of the means by which men, and especially princes, win applause, or incur censure.

- CHAPTER XVI. of liberality and parsimoniousness.

- CHAPTER XVII. of cruelty and clemency, and whether it is better to be loved than feared.

- CHAPTER XVIII. in what manner princes should keep their faith.

- CHAPTER XIX. a prince must avoid being contemned and hated.

- CHAPTER XX. whether the erection of fortresses, and many other things which princes often do, are useful, or injurious.

- CHAPTER XXI. how princes should conduct themselves to acquire a reputation.

- CHAPTER XXII. of the ministers of princes.

- CHAPTER XXIII. how to avoid flatterers.

- CHAPTER XXIV. the reason why the princes of italy have lost their states.

- CHAPTER XXV. of the influence of fortune in human affairs, and how it may be counteracted.

- CHAPTER XXVI. exhortation to deliver italy from foreign barbarians.

- Endnotes

- DISCOURSES on the FIRST TEN BOOKS

OF TITUS LIVIUS.

- NICCOLO MACHIAVELLI to ZANOBI BUONDELMONTE AND COSIMO RUCELLAI, GREETING.

- FIRST

BOOK.

- introduction.

- CHAPTER I. of the beginning of cities in general, and especially that of the city of rome.

- CHAPTER II. of the different kinds of republics, and of what kind the roman republic was.

- CHAPTER III. of the events that caused the creation of tribunes in rome; which made the republic more perfect.

- CHAPTER IV. the disunion of the senate and the people renders the republic of rome powerful and free.

- CHAPTER V. to whom can the guardianship of liberty more safely be confided, to the nobles or to the people? and which of the two have most cause for creating disturbances, those who wish to acquire, or those who desire to conserve?

- CHAPTER VI. whether it was possible to establish in rome a government capable of putting an end to the enmities existing between the nobles and the people.

- CHAPTER VII. showing how necessary the faculty of accusation is in a republic for the maintenance of liberty.

- CHAPTER VIII. in proportion as accusations are useful in a republic, so are calumnies pernicious.

- CHAPTER IX. to found a new republic, or to reform entirely the old institutions of an existing one, must be the work of one man only.

- CHAPTER X. in proportion as the founders of a republic or monarchy are entitled to praise, so do the founders of a tyranny deserve execration.

- CHAPTER XI. of the religion of the romans.

- CHAPTER XII. the importance of giving religion a prominent influence in a state, and how italy was ruined because she failed in this respect through the conduct of the church of rome.

- CHAPTER XIII. how the romans availed of religion to preserve order in their city, and to carry out their enterprises and suppress disturbances.

- CHAPTER XIV. the romans interpreted the auspices according to necessity, and very wisely made show of observing religion, even when they were obliged in reality to disregard it; and if any one recklessly disparaged it, he was punished.

- CHAPTER XV. how the samnites resorted to religion as an extreme remedy for their desperate condition.

- CHAPTER XVI. a people that has been accustomed to live under a prince preserves its liberties with difficulty, if by accident it has become free.

- CHAPTER XVII. a corrupt people that becomes free can with greatest difficulty maintain its liberty.

- CHAPTER XVIII. how in a corrupt state a free government may be maintained, assuming that one exists there already; and how it could be introduced, if none had previously existed.

- CHAPTER XIX. if an able and vigorous prince is succeeded by a feeble one, the latter may for a time be able to maintain himself; but if his successor be also weak, then the latter will not be able to preserve his state.

- CHAPTER XX. two continuous successions of able and virtuous princes will achieve great results; and as well-constituted republics have, in the nature of things, a succession of virtuous rulers, their acquisitions and extension will consequently be very great.

- CHAPTER XXI. princes and republics who fail to have national armies are much to be blamed.

- CHAPTER XXII. what we should note in the case of the three roman horatii and the alban curatii.

- CHAPTER XXIII. one should never risk one’s whole fortune unless supported by one’s entire forces, and therefore the mere guarding of passes is often dangerous.

- CHAPTER XXIV. well-ordered republics establish punishments and rewards for their citizens, but never set off one against the other.

- CHAPTER XXV. whoever wishes to reform an existing government in a free state should at least preserve the semblance of the old forms.

- CHAPTER XXVI. a new prince in a city or province conquered by him should organize everything anew.

- CHAPTER XXVII. showing that men are very rarely either entirely good or entirely bad.

- CHAPTER XXVIII. why rome was less ungrateful to her citizens than athens.

- CHAPTER XXIX. which of the two is most ungrateful, a people or a prince.

- CHAPTER XXX. how princes and republics should act to avoid the vice of ingratitude, and how a commander or a citizen should act so as not to expose himself to it.

- CHAPTER XXXI. showing that the roman generals were never severely punished for any faults they committed, not even when by their ignorance and unfortunate operations they occasioned serious losses to the republic.

- CHAPTER XXXII. a republic or a prince should not defer securing the good will of the people until they are themselves in difficulties.

- CHAPTER XXXIII. when an evil has sprung up within a state, or come upon it from without, it is safer to temporize with it rather than to attack it violently.

- CHAPTER XXXIV. the authority of the dictatorship has always proved beneficial to rome, and never injurious; it is the authority which men usurp, and not that which is given them by the free suffrages of their fellow-citizens, that is dangerous to civil liberty.

- CHAPTER XXXV. the reason why the creation of decemvirs in rome was injurious to liberty, notwithstanding that they were created by the free suffrages of the people.

- CHAPTER XXXVI. citizens who have been honored with the higher offices should not disdain less important ones.

- CHAPTER XXXVII. what troubles resulted in rome from the enactment of the agrarian law, and how very wrong it is to make laws that are retrospective and contrary to old established customs.

- CHAPTER XXXVIII. feeble republics are irresolute, and know not how to take a decided part; and whenever they do, it is more the result of necessity than of choice.

- CHAPTER XXXIX. the same accidents often happen to different peoples.

- CHAPTER XL. of the creation of the decemvirs in rome, and what is noteworthy in it; and where we shall consider amongst many other things how the same accidents may save or ruin a republic.

- CHAPTER XLI. it is imprudent and unprofitable suddenly to change from humility to pride, and from gentleness to cruelty.

- CHAPTER XLII. how easily men may be corrupted.

- CHAPTER XLIII. those only who combat for their own glory are good and loyal soldiers.

- CHAPTER XLIV. a multitude without a chief is useless; and it is not well to threaten before having the power to act.

- CHAPTER XLV. it is a bad example not to observe the laws, especially on the part of those who have made them; and it is dangerous for those who govern cities to harass the people with constant wrongs.

- CHAPTER XLVI. men rise from one ambition to another: first, they seek to secure themselves against attack, and then they attack others.

- CHAPTER XLVII. although men are apt to deceive themselves in general matters, yet they rarely do so in particulars.

- CHAPTER XLVIII. one of the means of preventing an important magistracy from being conferred upon a vile and wicked individual is to have it applied for by one still more vile and wicked, or by the most noble and deserving in the state.

- CHAPTER XLIX. if cities which from their beginning have enjoyed liberty, like rome, have found difficulties in devising laws that would preserve their liberties, those that have had their origin in servitude find it impossible to succeed in making such laws.

- CHAPTER L. no council or magistrate should have it in their power to stop the public business of a city.

- CHAPTER LI. a republic or a prince must feign to do of their own liberality that to which necessity compels them.

- CHAPTER LII. there is no surer and less objectionable mode of repressing the insolence of an individual ambitious of power, who arises in a republic, than to forestall him in the ways by which he expects to arrive at that power.

- CHAPTER LIII. how by the delusions of seeming good the people are often misled to desire their own ruin; and how they are frequently influenced by great hopes and brave promises.

- CHAPTER LIV. how much influence a great man has in restraining an excited multitude.

- CHAPTER LV. public affairs are easily managed in a city where the body of the people is not corrupt; and where equality exists, there no principality can be established; nor can a republic be established where there is no equality.

- CHAPTER LVI. the occurrence of important events in any city or country is generally preceded by signs and portents, or by men who predict them.

- CHAPTER LVII. the people as a body are courageous, but individually they are cowardly and feeble.

- CHAPTER LVIII. the people are wiser and more constant than princes.

- CHAPTER LIX. leagues and alliances with republics are more to be trusted than those with princes.

- CHAPTER LX. how the consulates and some other magistracies were bestowed in rome without regard to the age of persons.

- SECOND

BOOK.

- introduction.

- CHAPTER I. the greatness of the romans was due more to their valor and ability than to good fortune.

- CHAPTER II. what nations the romans had to contend against, and with what obstinacy they defended their liberty.

- CHAPTER III. rome became great by ruining her neighboring cities, and by freely admitting strangers to her privileges and honors.

- CHAPTER IV. the ancient republics employed three different methods for aggrandizing themselves.

- CHAPTER V. the changes of religion and of languages, together with the occurrence of deluges and pestilences, destroy the record of things.

- CHAPTER VI. of the manner in which the romans conducted their wars.

- CHAPTER VII. how much land the romans allowed to each colonist.

- CHAPTER VIII. the reasons why people leave their own country to spread over others.

- CHAPTER IX. what the causes are that most frequently provoke war between sovereigns.

- CHAPTER X. money is not the sinews of war, although it is generally so considered.

- CHAPTER XI. it is not wise to form an alliance with a prince that has more reputation than power.

- CHAPTER XII. whether it is better, when apprehending an attack, to await it at home, or to carry the war into the enemy’s country.

- CHAPTER XIII. cunning and deceit will serve a man better than force to rise from a base condition to great fortune.

- CHAPTER XIV. men often deceive themselves in believing that by humility they can overcome insolence.

- CHAPTER XV. feeble states are always undecided in their resolves; and slow resolves are invariably injurious.

- CHAPTER XVI. wherein the military system differs from that of the ancients.

- CHAPTER XVII. of the value of artillery to modern armies, and whether the general opinion respecting it is correct.

- CHAPTER XVIII. according to the authority of the romans and the example of ancient armies we should value infantry more than cavalry.

- CHAPTER XIX. conquests made by republics that are not well constituted, and do not follow in their conduct the example of the romans, are more conducive to their ruin than to their advancement.

- CHAPTER XX. of the dangers to which princes and republics are exposed that employ auxiliary or mercenary troops.

- CHAPTER XXI. the first prætor sent by the romans anywhere was to capua, four hundred years after they began to make war upon that city.

- CHAPTER XXII. how often the judgments of men in important matters are erroneous.

- CHAPTER XXIII. how much the romans avoided half-way measures when they had to decide upon the fate of their subjects.

- CHAPTER XXIV. fortresses are generally more injurious than useful.

- CHAPTER XXV. it is an error to take advantage of the internal dissensions of a city, and to attempt to take possession of it whilst in that condition.

- CHAPTER XXVI. contempt and insults engender hatred against those who indulge in them, without being of any advantage to them.

- CHAPTER XXVII. wise princes and republics should content themselves with victory; for when they aim at more, they generally lose.

- CHAPTER XXVIII. how dangerous it is for a republic or a prince not to avenge a public or a private injury.

- CHAPTER XXIX. fortune blinds the minds of men when she does not wish them to oppose her designs.

- CHAPTER XXX. republics and princes that are really powerful do not purchase alliances by money, but by their valor and the reputation of their armies.

- CHAPTER XXXI. how dangerous it is to trust to the representations of exiles.

- CHAPTER XXXII. of the method practised by the romans in taking cities.

- CHAPTER XXXIII. the romans left the commanders of their armies entirely uncontrolled in their operations.

- THIRD

BOOK.

- CHAPTER I. to insure a long existence to religious sects or republics, it is necessary frequently to bring them back to their original principles.

- CHAPTER II. it may at times be the highest wisdom to simulate folly.

- CHAPTER III. to preserve the newly recovered liberty in rome, it was necessary that the sons of brutus should have been executed.

- CHAPTER IV. a prince cannot live securely in a state so long as those live whom he has deprived of it.

- CHAPTER V. of the causes that make a king lose the throne which he has inherited.

- CHAPTER VI. of conspiracies.

- CHAPTER VII. the reasons why the transitions from liberty to servitude and from servitude to liberty are at times effected without bloodshed, and at other times are most sanguinary.

- CHAPTER VIII. whoever wishes to change the government of a republic should first consider well its existing condition.

- CHAPTER IX. whoever desires constant success must change his conduct with the times.

- CHAPTER X. a general cannot avoid a battle when the enemy is resolved upon it at all hazards.

- CHAPTER XI. whoever has to contend against many enemies may nevertheless overcome them, though he be inferior in power, provided he is able to resist their first efforts.

- CHAPTER XII. a skilful general should endeavor by all means in his power to place his soldiers in the position of being obliged to fight, and as far as possible relieve the enemy of such necessity.

- CHAPTER XIII. whether an able commander with a feeble army, or a good army with an incompetent commander, is most to be relied upon.

- CHAPTER XIV. of the effect of new stratagems and unexpected cries in the midst of battle.

- CHAPTER XV. an army should have but one chief: a greater number is detrimental.

- CHAPTER XVI. in times of difficulty men of merit are sought after, but in easy times it is not men of merit, but such as have riches and powerful relations, that are most in favor.

- CHAPTER XVII. a person who has been offended should not be intrusted with an important administration and government.

- CHAPTER XVIII. nothing is more worthy of the attention of a good general than to endeavor to penetrate the designs of the enemy.

- CHAPTER XIX. whether gentle or rigorous measures are preferable in governing the multitude.

- CHAPTER XX. an act of humanity prevailed more with the faliscians than all the power of rome.

- CHAPTER XXI. why hannibal by a course of conduct the very opposite of that of scipio yet achieved the same success in italy as the latter did in spain.

- CHAPTER XXII. how manlius torquatus by harshness, and valerius corvinus by gentleness, acquired equal glory.

- CHAPTER XXIII. the reasons why camillus was banished from rome.

- CHAPTER XXIV. the prolongation of military commands caused rome the loss of her liberty.

- CHAPTER XXV. of the poverty of cincinnatus, and that of many other roman citizens.

- CHAPTER XXVI. how states are ruined on account of women.

- CHAPTER XXVII. of the means for restoring union in a city, and of the common error which supposes that a city must be kept divided for the purpose of preserving authority.

- CHAPTER XXVIII. the actions of citizens should be watched, for often such as seem virtuous conceal the beginning of tyranny.

- CHAPTER XXIX. the faults of the people spring from the faults of their rulers.

- CHAPTER XXX. a citizen who desires to employ his authority in a republic for some public good must first of all suppress all feeling of envy: and how to organize the defence of a city on the approach of an enemy.

- CHAPTER XXXI. great men and powerful republics preserve an equal dignity and courage in prosperity and adversity.

- CHAPTER XXXII. of the means adopted by some to prevent a peace.

- CHAPTER XXXIII. to insure victory the troops must have confidence in themselves as well as in their commander.

- CHAPTER XXXIV. how the reputation of a citizen and the public voice and opinion secure him popular favor; and whether the people or princes show most judgment in the choice of magistrates.

- CHAPTER XXXV. of the danger of being prominent in counselling any enterprise, and how that danger increases with the importance of such enterprise.

- CHAPTER XXXVI. the reason why the gauls have been and are still looked upon at the beginning of a combat as more than men, and afterwards as less than women.

- CHAPTER XXXVII. whether skirmishes are necessary before coming to a general action, and how to know a new enemy if skirmishes are dispensed with.

- CHAPTER XXXVIII. what qualities a commander should possess to secure the confidence of his army.

- CHAPTER XXXIX. a general should possess a perfect knowledge of the localities where he is carrying on a war.

- CHAPTER XL. deceit in the conduct of a war is meritorious.

- CHAPTER XLI. one’s country must be defended, whether with glory or with shame; it must be defended anyhow.

- CHAPTER XLII. promises exacted by force need not be observed.

- CHAPTER XLIII. natives of the same country preserve for all time the same characteristics.

- CHAPTER XLIV. impetuosity and audacity often achieve what ordinary means fail to attain.

- CHAPTER XLV. whether it is better in battle to await the shock of the enemy, and then to attack him, or to assail him first with impetuosity.

- CHAPTER XLVI. the reasons why the same family in a city always preserves the same characteristics.

- CHAPTER XLVII. love of country should make a good citizen forget private wrongs.

- CHAPTER XLVIII. any manifest error on the part of an enemy should make us suspect some stratagem.

- CHAPTER XLIX. a republic that desires to maintain her liberties needs daily fresh precautions: it was by such merits that fabius obtained the surname of maximus.

- Endnotes

- THOUGHTS

OF A STATESMAN.

- PREFATORY NOTE.

- Niccolo Machiavelli to his Son Bernardo.

- CHAPTER I. religion.

- CHAPTER II. peace and war.

- CHAPTER III. the admirable law of nations born with christianity.

- CHAPTER IV. vices that have made the great the prey of the small.

- CHAPTER V. laws.

- CHAPTER VI. justice.

- CHAPTER VII. public charges.

- CHAPTER VIII. of agriculture, commerce, population, luxury, and supplies.

- CHAPTER IX. the evils of idleness.

- CHAPTER X. ill effects of a corrupt government.

- CHAPTER XI. notable precepts and maxims.

- CHAPTER XII. beautiful example of a good father of a family.

- CHAPTER XIII. the good prince.

- CHAPTER XIV. of the ministers.

- CHAPTER XV. the tyrant prince.

- CHAPTER XVI. praise and safety of the good prince, and infamy and danger of the tyrant.

- Endnotes

THE PRINCE.

NICCOLO MACHIAVELLI to the MAGNIFICENT LORENZO, SON OF PIERO DE’ MEDICI.

Those who desire to win the favor of princes generally endeavor to do so by offering them those things which they themselves prize most, or such as they observe the prince to delight in most. Thence it is that princes have very often presented to them horses, arms, cloth of gold, precious stones, and similar ornaments worthy of their greatness. Wishing now myself to offer to your Magnificence some proof of my devotion, I have found nothing amongst all I possess that I hold more dear or esteem more highly than the knowledge of the actions of great men, which I have acquired by long experience of modern affairs, and a continued study of ancient history.

These I have meditated upon for a long time, and examined with great care and diligence; and having now written them out in a small volume, I send this to your Magnificence. And although I judge this work unworthy of you, yet I trust that your kindness of heart may induce you to accept it, considering that I cannot offer you anything better than the means of understanding in the briefest time all that which I have learnt by so many years of study, and with so much trouble and danger to myself.

I have not set off this little work with pompous phrases, nor filled it with high-sounding and magnificent words, nor with any other allurements or extrinsic embellishments with which many are wont to write and adorn their works; for I wished that mine should derive credit only from the truth of the matter, and that the importance of the subject should make it acceptable.

And I hope it may not be accounted presumption if a man of lowly and humble station ventures to discuss and direct the conduct of princes; for as those who wish to delineate countries place themselves low in the plain to observe the form and character of mountains and high places, and for the purpose of studying the nature of the low country place themselves high upon an eminence, so one must be a prince to know well the character of the people, and to understand well the nature of a prince one must be of the people.

May your Magnificence then accept this little gift in the same spirit in which I send it; and if you will read and consider it well, you will recognize in it my desire that you may attain that greatness which fortune and your great qualities promise. And if your Magnificence will turn your eyes from the summit of your greatness towards those low places, you will know how undeservedly I have to bear the great and continued malice of fortune.

CHAPTER I.

how many kinds of principalities there are, and in what manner they are acquired.

All states and governments that have had, and have at present, dominion over men, have been and are either republics or principalities.

The principalities are either hereditary or they are new. Hereditary principalities are those where the government has been for a long time in the family of the prince. New principalities are either entirely new, as was Milan to Francesco Sforza, or they are like appurtenances annexed to the hereditary state of the prince who acquires them, as the kingdom of Naples is to that of Spain.

States thus acquired have been accustomed either to live under a prince, or to exist as free states; and they are acquired either by the arms of others, or by the conqueror’s own, or by fortune or valor.

CHAPTER II.

of hereditary principalities.

I will not discuss here the subject of republics, having treated of them at length elsewhere, but will confine myself only to principalities; and following the above indicated order of distinctions, I will proceed to discuss how states of this kind should be governed and maintained. I say, then, that hereditary states, accustomed to the line of their prince, are maintained with much less difficulty than new states. For it is enough merely that the prince do not transcend the order of things established by his predecessors, and then to accommodate himself to events as they occur. So that if such a prince has but ordinary sagacity, he will always maintain himself in his state, unless some extraordinary and superior force should deprive him of it. And even in such a case he will recover it, whenever the occupant meets with any reverses. We have in Italy, for instance, the Duke of Ferrara, who could not have resisted the assaults of the Venetians in 1484, nor those of Pope Julius II. in 1510, but for the fact that his family had for a great length of time held the sovereignty of that dominion. For the natural prince has less cause and less necessity for irritating his subjects, whence it is reasonable that he should be more beloved. And unless extraordinary vices should cause him to be hated, he will naturally have the affection of his people. For in the antiquity and continuity of dominion the memory of innovations, and their causes, are effaced; for each change and alteration always prepares the way and facilitates the next.

CHAPTER III.

of mixed principalities.

But it is in a new principality that difficulties present themselves. In the first place, if it be not entirely new, but composed of different parts, which when taken all together may as it were be called mixed, its mutations arise in the beginning from a natural difficulty, which is inherent in all new principalities, because men change their rulers gladly, in the belief that they will better themselves by the change. It is this belief that makes them take up arms against the reigning prince; but in this they deceive themselves, for they find afterwards from experience that they have only made their condition worse. This is the inevitable consequence of another natural and ordinary necessity, which ever obliges a new prince to vex his people with the maintenance of an armed force, and by an infinite number of other wrongs that follow in the train of new conquests. Thus the new prince finds that he has for enemies all those whom he has injured by seizing that principality; and at the same time he cannot preserve as friends even those who have aided him in obtaining possession, because he cannot satisfy their expectations, nor can he employ strong measures against them, being under obligations to them. For however strong a new prince may be in troops, yet will he always have need of the good will of the inhabitants, if he wishes to enter into firm possession of the country.

It was for these reasons that Louis XII., king of France, having suddenly made himself master of Milan, lost it as quickly, Lodovico Sforza’s own troops alone having sufficed to wrest it from him the first time. For the very people who had opened the gates to Louis XII., finding themselves deceived in their expectations of immediate as well as prospective advantages, soon became disgusted with the burdens imposed by the new prince.

It is very true that, having recovered such revolted provinces, it is easier to keep them in subjection; for the prince will avail himself of the occasion of the rebellion to secure himself, with less consideration for the people, by punishing the guilty, watching the suspected, and strengthening himself at all the weak points of the province. Thus a mere demonstration on the frontier by Lodovico Sforza lost Milan to the French the first time; but to make them lose it a second time required the whole world to be against them, and that their armies should be dispersed and driven out of Italy; which resulted from the reasons which I have explained above. Nevertheless, France lost Milan both the first and the second time.

The general causes of the first loss have been sufficiently explained; but it remains to be seen now what occasioned the loss of Milan to France the second time, and to point out the remedies which the king had at his command, and which might be employed by any other prince under similar circumstances to maintain himself in a conquered province, but which King Louis XII. failed to employ.

I will say then, first, that the states which a prince acquires and annexes to his own dominions are either in the same country, speaking the same language, or they are not. When they are, it is very easy to hold them, especially if they have not been accustomed to govern themselves; for in that case it suffices to extinguish the line of the prince who, till then, has ruled over them, but otherwise to maintain their old institutions. There being no difference in their manners and customs, the inhabitants will submit quietly, as we have seen in the case of Burgundy, Brittany, Gascony, and Normandy, which provinces have remained so long united to France. For although there are some differences of language, yet their customs are similar, and therefore they were easily reconciled to each other. Hence, in order to retain a newly acquired state, regard must be had to two things: one, that the line of the ancient sovereign be entirely extinguished; and the other, that the laws be not changed, nor the taxes increased, so that the new may, in the least possible time, be thoroughly incorporated with the ancient state.

But when states are acquired in a country differing in language, customs, and laws, then come the difficulties, and then it requires great good-fortune and much sagacity to hold them; and one of the best and most efficient means is for the prince who has acquired them to go and reside there, which will make his possession more secure and durable. Such was the course adopted by the Turk in Greece, who even if he had respected all the institutions of that country, yet could not possibly have succeeded in holding it, if he had not gone to reside there. For being on the spot, you can quickly remedy disorders as you see them arise; but not being there, you do not hear of them until they have become so great that there is no longer any remedy for them. Besides this, the country will not be despoiled by your officials, and the subjects will be satisfied by the easy recourse to the prince who is near them, which contributes to win their affections, if they are well disposed, and to inspire them with fear, if otherwise. And other powers will hesitate to assail a state where the prince himself resides, as they would find it very difficult to dispossess him.

The next best means for holding a newly acquired state is to establish colonies in one or two places that are as it were the keys to the country. Unless this is done, it will be necessary to keep a large force of men-at-arms and infantry there for its protection. Colonies are not very expensive to the prince; they can be established and maintained at little, if any, cost to him; and only those of the inhabitants will be injured by him whom he deprives of their homes and fields, for the purpose of bestowing them upon the colonists; and this will be the case only with a very small minority of the original inhabitants. And as those who are thus injured by him become dispersed and poor, they can never do him any harm, whilst all the other inhabitants remain on the one hand uninjured, and therefore easily kept quiet, and on the other hand they are afraid to stir, lest they should be despoiled as the others have been. I conclude then that such colonies are inexpensive, and are more faithful to the prince and less injurious to the inhabitants generally; whilst those who are injured by their establishment become poor and dispersed, and therefore unable to do any harm, as I have already said. And here we must observe that men must either be flattered or crushed; for they will revenge themselves for slight wrongs, whilst for grave ones they cannot. The injury therefore that you do to a man should be such that you need not fear his revenge.

But if instead of colonies an armed force be sent for the preservation of a newly acquired province, then it will involve much greater expenditures, so that the support of such a guard may consume the entire revenue of the province; so that this acquisition may prove an actual loss, and will moreover give greater offence, because the whole population will feel aggrieved by having the armed force quartered upon them in turn. Every one that is made to suffer from this inconvenience will become an enemy; and these are enemies that can injure the prince, for although beaten yet they remain in their homes. In every point of view, then, such a military guard is disadvantageous, just as colonies are most useful.

A prince, moreover, who wishes to keep possession of a country that is separate and unlike his own, must make himself the chief and protector of the smaller neighboring powers. He must endeavor to weaken the most powerful of them, and must take care that by no chance a stranger enter that province who is equally powerful with himself; for strangers are never called in except by those whom an undue ambition or fear have rendered malcontents. It was thus in fact that the Ætolians called the Romans into Greece; and whatever other country the Romans entered, it was invariably at the request of the inhabitants.

The way in which these things happen is generally thus: so soon as a powerful foreigner enters a province, all those of its inhabitants that are less powerful will give him their adhesion, being influenced thereto by their jealousy of him who has hitherto been their superior. So that, as regards these petty lords, the new prince need not be at any trouble to win them over to himself, as they will all most readily become incorporated with the state which he has there acquired. He has merely to see to it that they do not assume too much authority, or acquire too much power; for he will then be able by their favor, and by his own strength, very easily to humble those who are really powerful; so that he will in all respects remain the sole arbiter of that province. And he who does not manage this part well will quickly lose what he has acquired; and whilst he holds it, he will experience infinite difficulties and vexations. The Romans observed these points most carefully in the provinces which they conquered; they established colonies there, and sustained the feebler chiefs without increasing their power, whilst they humbled the stronger, and permitted no powerful stranger to acquire any influence or credit there. I will confine myself for an example merely to the provinces of Greece. The Romans sustained the Achaians and the Ætolians, whilst they humbled the kingdom of Macedon and expelled Antiochus from his dominions; but neither the merits of the Achaians or of the Ætolians caused the Romans to permit either of them to increase in power; nor could the persuasions of Philip induce the Romans to become his friends until after first having humbled his power; nor could the power of Antiochus make them consent that he should hold any state in that province.

Thus in all these cases the Romans did what all wise princes ought to do; namely, not only to look to all present troubles, but also to those of the future, against which they provided with the utmost prudence. For it is by foreseeing difficulties from afar that they are easily provided against; but awaiting their near approach, remedies are no longer in time, for the malady has become incurable. It happens in such cases, as the doctors say of consumption, that in the early stages it is easy to cure, but difficult to recognize; whilst in the course of time, the disease not having been recognized and cured in the beginning, it becomes easy to know, but difficult to cure. And thus it is in the affairs of state; for when the evils that arise in it are seen far ahead, which it is given only to a wise prince to do, then they are easily remedied; but when, in consequence of not having been foreseen, these evils are allowed to grow and assume such proportions that they become manifest to every one, then they can no longer be remedied.

The Romans therefore, on seeing troubles far ahead, always strove to avert them in time, and never permitted their growth merely for the sake of avoiding a war, well knowing that the war would not be prevented, and that to defer it would only be an advantage to others; and for these reasons they resolved upon attacking Philip and Antiochus in Greece, so as to prevent these from making war upon them in Italy. They might at the time have avoided both the one and the other, but would not do it; nor did they ever fancy the saying which is nowadays in the mouth of every wiseacre, “to bide the advantages of time,” but preferred those of their own valor and prudence; for time drives all things before it, and may lead to good as well as to evil, and to evil as well as to good.

But let us return to France, and examine whether she has done any one of the things that we have spoken of. I will say nothing of Charles VIII., but only of Louis XII., whose proceedings we are better able to understand, as he held possession of Italy for a greater length of time. And we shall see how he did the very opposite of what he should have done, for the purpose of holding a state so unlike his own.

King Louis XII. was called into Italy by the ambition of the Venetians, who wanted him to aid them in conquering a portion of Lombardy. I will not blame the king for the part he took; for, wishing to gain a foothold in Italy, and having no allies there, but rather finding the gates everywhere closed against him in consequence of the conduct of King Charles VIII., he was obliged to avail himself of such friends as he could find; and would have succeeded in his attempt, which was well planned, but for an error which he committed in his subsequent conduct. The king, then, having conquered Lombardy, quickly recovered that reputation which his predecessor, Charles VIII., had lost. Genoa yielded; the Florentines became his friends; the Marquis of Mantua, the Duke of Ferrara, the Bentivogli, the lady of Furli, the lords of Faenza, Pesaro, Rimini, Camerino, and Piombino, the Lucchese, the Pisanese, and the Siennese, all came to meet him with offers of friendship. The Venetians might then have recognized the folly of their course, when, for the sake of gaining two cities in Lombardy, they made King Louis master of two thirds of Italy.

Let us see now how easily the king might have maintained his influence in Italy if he had observed the rules above given. Had he secured and protected all these friends of his, who were numerous but feeble, — some fearing the Church, and some the Venetians, and therefore all forced to adhere to him, — he might easily have secured himself against the remaining stronger powers of Italy. But no sooner in Milan than he did the very opposite, by giving aid to Pope Alexander VI. to enable him to seize the Romagna. Nor did he perceive that in doing this he weakened himself, by alienating his friends and those who had thrown themselves into his arms; and that he had made the Church great by adding so much temporal to its spiritual power, which gave it already so much authority. Having committed this first error, he was obliged to follow it up; so that, for the purpose of putting an end to the ambition of Pope Alexander VI., and preventing his becoming master of Tuscany, he was obliged to come into Italy.

Not content with having made the Church great, and with having alienated his own friends, King Louis, in his eagerness to possess the kingdom of Naples, shared it with the king of Spain; so that where he had been the sole arbiter of Italy, he established an associate and rival, to whom the ambitious and the malcontents might have a ready recourse. And whilst he could have left a king in Naples who would have been his tributary, he dispossessed him, for the sake of replacing him by another who was powerful enough in turn to drive him out.

The desire of conquest is certainly most natural and common amongst men, and whenever they yield to it and are successful, they are praised; but when they lack the means, and yet attempt it anyhow, then they commit an error that merits blame. If, then, the king of France was powerful enough by himself successfully to attack the kingdom of Naples, then he was right to do so; but if he was not, then he should not have divided it with the king of Spain. And if the partition of Lombardy with the Venetians was excusable because it enabled him to gain a foothold in Italy, that of Naples with the Spaniard deserves censure, as it cannot be excused on the ground of necessity.

Louis XII. then committed these five errors: he destroyed the weak; he increased the power of one already powerful in Italy; he established a most powerful stranger there; he did not go to reside there himself; nor did he plant any colonies there. These errors, however, would not have injured him during his lifetime, had he not committed a sixth one in attempting to deprive the Venetians of their possessions. For if Louis had not increased the power of the Church, nor established the Spaniards in Italy, it would have been quite reasonable, and even advisable, for him to have weakened the Venetians; but having done both those things, he ought never to have consented to their ruin; for so long as the Venetians were powerful, they would always have kept others from any attempt upon Lombardy. They would on the one hand never have permitted this unless it should have led to their becoming masters of it, and on the other hand no one would have taken it from France for the sake of giving it to the Venetians; nor would any one have had the courage to attack the French and the Venetians combined. And should it be said that King Louis gave up the Romagna to Pope Alexander VI., and divided the kingdom of Naples with the Spaniard for the sake of avoiding a war, then I reply with the above stated reasons, that no one should ever submit to an evil for the sake of avoiding a war. For a war is never avoided, but is only deferred to one’s own disadvantage.

And should it be argued, on the other hand, that the king felt bound by the pledge which he had given to the Pope to conquer the Romagna for him in consideration of his dissolving the king’s marriage, and of his bestowing the cardinal’s hat upon the Archbishop of Rouen, then I meet that argument with what I shall say further on concerning the pledges of princes, and the manner in which they should keep them.

King Louis then lost Lombardy by not having conformed to any one of the conditions that have been observed by others, who, having conquered provinces, wanted to keep them. Nor is this at all to be wondered at, for it is quite reasonable and common. I conversed on this subject with the Archbishop of Rouen (Cardinal d’Amboise) whilst at Nantes, when the Duke Valentino, commonly called Cesar Borgia, son of Pope Alexander VI., made himself master of the Romagna. On that occasion the Cardinal said to me, that the Italians did not understand the art of war. To which I replied that the French did not understand statesmanship; for if they had understood it, they would never have allowed the Church to attain such greatness and power. For experience proves that the greatness of the Church and that of Spain in Italy were brought about by France, and that her own ruin resulted therefrom. From this we draw the general rule, which never or rarely fails, that the prince who causes another to become powerful thereby works his own ruin; for he has contributed to the power of the other either by his own ability or force, and both the one and the other will be mistrusted by him whom he has thus made powerful.

CHAPTER IV.

why the kingdom of darius, which was conquered by alexander, did not revolt against the successors of alexander after his death.

If we reflect upon the difficulties of preserving a newly acquired state, it seems marvellous that, after the rapid conquest of all Asia by Alexander the Great, and his subsequent death, which one would suppose most naturally to have provoked the whole country to revolt, yet his successors maintained their possession of it, and experienced no other difficulties in holding it than such as arose amongst themselves from their own ambition.

I meet this observation by saying that all principalities of which we have any accounts have been governed in one of two ways; viz. either by one absolute prince, to whom all others are as slaves, some of whom, as ministers, by his grace and consent, aid him in the government of his realm; or else by a prince and nobles, who hold that rank, not by the grace of their sovereign, but by the antiquity of their lineage. Such nobles have estates and subjects of their own, who recognize them as their liege lords, and have a natural affection for them.

In those states that are governed by an absolute prince and slaves, the prince has far more power and authority; for in his entire dominion no one recognizes any other superior but him; and if they obey any one else, they do it as though to his minister and officer, and without any particular affection for such official. Turkey and France furnish us examples of these two different systems of government at the present time. The whole country of the Turk is governed by one master; all the rest are his slaves; and having divided the country into Sanjacs, or districts, he appoints governors for each of these, whom he changes and replaces at his pleasure.

But the king of France is placed in the midst of a large number of ancient nobles, who are recognized and acknowledged by their subjects as their lords, and are held in great affection by them. They have their rank and prerogatives, of which the king cannot deprive them without danger to himself. In observing now these two principalities, we perceive the difficulty of conquering the empire of the Turk, but once conquered it will be very easily held. The reasons that make the conquest of the Turkish empire so difficult are, that the conqueror cannot be called into the country by any of the great nobles of the state; nor can he hope that his attempt could be facilitated by a revolt of those who surround the sovereign; which arises from the above given reasons. For being all slaves and dependants of their sovereign, it is more difficult to corrupt them; and even if they were corrupted, but little advantage could be hoped for from them, because they cannot carry the people along with them.

Whoever therefore attacks the Turks must expect to find them united, and must depend wholly upon his own forces, and not upon any internal disturbances. But once having defeated and driven the Turk from the field, so that he cannot reorganize his army, then he will have nothing to fear but the line of the sovereign. This however once extinguished, the conqueror has nothing to apprehend from any one else, as none other has any influence with the people; and thus, having had nothing to hope from them before the victory, he will have nothing to fear from them afterwards.

The contrary takes place in kingdoms governed like that of France; for having gained over some of the great nobles of the realm, there will be no difficulty in entering it, there being always malcontents and others who desire a change. These, for the reasons stated, can open the way into the country for the assailant, and facilitate his success. But for the conqueror to maintain himself there afterwards will involve infinite difficulties, both with the conquered and with those who have aided him in his conquest. Nor will it suffice to extinguish the line of the sovereign, because the great nobles remain, who will place themselves at the head of new movements; and the conqueror, not being able either to satisfy or to crush them, will lose the country again on the first occasion that presents itself.

If now we consider the nature of the government of Darius, we shall find that it resembled that of the Turk, and therefore it was necessary for Alexander to attack him in full force, and drive him from the field. After this victory and the death of Darius, Alexander remained in secure possession of the kingdom for the reasons above explained. And if his successors had remained united, they might also have enjoyed possession at their ease; for no other disturbances occurred in that empire, except such as they created themselves.

Countries, however, with a system of government like that of France, cannot possibly be held so easily. The frequent insurrections of Spain, France, and Greece against the Romans were due to the many petty princes that existed in those states; and therefore, so long as the memory of these princes endured, the Romans were ever uncertain in the tenure of those states. But all remembrance of these princes once effaced, the Romans became secure possessors of those countries, so long as the growth and power of their empire endured. And even afterwards, when fighting amongst themselves, each of the parties were able to keep for themselves portions of those countries, according to the authority which they had acquired there; and the line of their sovereigns being extinguished, the inhabitants recognized no other authority but that of the Romans.

Reflecting now upon these things, we cannot be surprised at the facility with which Alexander maintained himself in Asia; nor at the difficulties which others experienced in preserving their conquests, as was the case with Pyrrhus and many others, and which resulted not from the greater or lesser valor of the conqueror, but from the different nature of the conquered states.

CHAPTER V.

how cities or principalities are to be governed that previous to being conquered had lived under their own laws.

Conquered states that have been accustomed to liberty and the government of their own laws can be held by the conqueror in three different ways. The first is to ruin them; the second, for the conqueror to go and reside there in person; and the third is to allow them to continue to live under their own laws, subject to a regular tribute, and to create in them a government of a few, who will keep the country friendly to the conqueror. Such a government, having been established by the new prince, knows that it cannot maintain itself without the support of his power and friendship, and it becomes its interest therefore to sustain him. A city that has been accustomed to free institutions is much easier held by its own citizens than in any other way, if the conqueror desires to preserve it. The Spartans and the Romans will serve as examples of these different ways of holding a conquered state.

The Spartans held Athens and Thebes, creating there a government of a few; and yet they lost both these states again. The Romans, for the purpose of retaining Capua, Carthage, and Numantia, destroyed them, but did not lose them. They wished to preserve Greece in somewhat the same way that the Spartans had held it, by making her free and leaving her in the enjoyment of her own laws, but did not succeed; so that they were obliged to destroy many cities in that country for the purpose of holding it. In truth there was no other safe way of keeping possession of that country but to ruin it. And whoever becomes master of a city that has been accustomed to liberty, and does not destroy it, must himself expect to be ruined by it. For they will always resort to rebellion in the name of liberty and their ancient institutions, which will never be effaced from their memory, either by the lapse of time, or by benefits bestowed by the new master. No matter what he may do, or what precautions he may take, if he does not separate and disperse the inhabitants, they will on the first occasion invoke the name of liberty and the memory of their ancient institutions, as was done by Pisa after having been held over a hundred years in subjection by the Florentines.

But it is very different with states that have been accustomed to live under a prince. When the line of the prince is once extinguished, the inhabitants, being on the one hand accustomed to obey, and on the other having lost their ancient sovereign, can neither agree to create a new one from amongst themselves, nor do they know how to live in liberty; and thus they will be less prompt to take up arms, and the new prince will readily be able to gain their good will and to assure himself of them. But republics have more vitality, a greater spirit of resentment and desire of revenge, for the memory of their ancient liberty neither can nor will permit them to remain quiet, and therefore the surest way of holding them is either to destroy them, or for the conqueror to go and live there.

CHAPTER VI.

of new principalities that have been acquired by the valor of the prince and by his own troops.

Let no one wonder if, in what I am about to say of entirely new principalities and of the prince and his government, I cite the very highest examples. For as men almost always follow the beaten track of others, and proceed in their actions by imitation, and yet cannot altogether follow the ways of others, nor attain the high qualities of those whom they imitate, so a wise man should ever follow the ways of great men and endeavor to imitate only such as have been most eminent; so that even if his merits do not quite equal theirs, yet that they may in some measure reflect their greatness. He should do as the skilful archer, who, seeing that the object he desires to hit is too distant, and knowing the extent to which his bow will carry, aims higher than the destined mark, not for the purpose of sending his arrow to that height, but so that by this elevation it may reach the desired aim.

I say then that a new prince in an entirely new principality will experience more or less difficulty in maintaining himself, according as he has more or less courage and ability. And as such an event as to become a prince from a mere private individual presupposes either great courage or rare good fortune, it would seem that one or the other of these two causes ought in a measure to mitigate many of these difficulties. But he who depends least upon fortune will maintain himself best; which will be still more easy for the Prince if, having no other state, he is obliged to reside in his newly acquired principality.

To come now to those who by their courage and ability, and not by fortune, have risen to the rank of rulers, I will say that the most eminent of such were Moses, Cyrus, Romulus, Theseus, and the like. And although we may not discuss Moses, who was a mere executor of the things ordained by God, yet he merits our admiration, if only for that grace which made him worthy to hold direct communion with the Almighty. But if we consider Cyrus and others who have conquered or founded empires, we shall find them all worthy of admiration; for it we study their acts and particular ordinances, they do not seem very different from those of Moses, although he had so great a teacher. We shall also find in examining their acts and lives, that they had no other favor from fortune but opportunity, which gave them the material which they could mould into whatever form seemed to them best; and without such opportunity the great qualities of their souls would have been wasted, whilst without those great qualities the opportunities would have been in vain.

It was necessary then for Moses to find the people of Israel slaves in Egypt, and oppressed by the Egyptians, so that to escape from that bondage they resolved to follow him. It was necessary that Romulus should not have been kept in Alba, and that he should have been exposed at his birth, for him to have become the founder and king of Rome. And so it was necessary for Cyrus to find the Persians dissatisfied with the rule of the Medes, and the Medes effeminate and enfeebled by long peace. And finally, Theseus could not have manifested his courage had he not found the Athenians dispersed. These opportunities therefore made these men fortunate, and it was their lofty virtue that enabled them to recognize the opportunities by which their countries were made illustrious and most happy. Those who by similar noble conduct become princes acquire their principalities with difficulty, but maintain them with ease; and the difficulties which they experience in acquiring their principalities arise in part from the new ordinances and customs which they are obliged to introduce for the purpose of founding their state and their own security. We must bear in mind, then, that there is nothing more difficult and dangerous, or more doubtful of success, than an attempt to introduce a new order of things in any state. For the innovator has for enemies all those who derived advantages from the old order of things, whilst those who expect to be benefited by the new institutions will be but lukewarm defenders. This indifference arises in part from fear of their adversaries who were favored by the existing laws, and partly from the incredulity of men who have no faith in anything new that is not the result of well-established experience. Hence it is that, whenever the opponents of the new order of things have the opportunity to attack it, they will do it with the zeal of partisans, whilst the others defend it but feebly, so that it is dangerous to rely upon the latter.

If we desire to discuss this subject thoroughly, it will be necessary to examine whether such innovators depend upon themselves, or whether they rely upon others; that is to say, whether for the purpose of carrying out their plans they have to resort to entreaties, or whether they can accomplish it by force. In the first case they always succeed badly, and fail to conclude anything; but when they depend upon their own strength to carry their innovations through, then they rarely incur any danger. Thence it was that all prophets who came with arms in hand were successful, whilst those who were not armed were ruined. For besides the reasons given above, the dispositions of peoples are variable; it is easy to persuade them to anything, but difficult to confirm them in that belief. And therefore a prophet should be prepared, in case the people will not believe any more, to be able by force to compel them to that belief.

Neither Moses, Cyrus, Theseus, nor Romulus would have been able to make their laws and institutions observed for any length of time, if they had not been prepared to enforce them with arms. This was the experience of Brother Girolamo Savonarola, who failed in his attempt to establish a new order of things so soon as the multitude ceased to believe in him; for he had not the means to keep his believers firm in their faith, nor to make the unbelievers believe. And yet these great men experienced great difficulties in their course, and met danger at every step, which could only be overcome by their courage and ability. But once having surmounted them, then they began to be held in veneration; and having crushed those who were jealous of their great qualities, they remained powerful, secure, honored, and happy.

To these great examples I will add a minor one, which nevertheless bears some relation to them, and will suffice me for all similar cases. This is Hiero of Syracuse, who from a mere private individual rose to be prince of Syracuse, although he owed no other favor to fortune than opportunity; for the Syracusans, being oppressed, elected him their captain, whence he advanced by his merits to become their prince. And even in his condition as a private citizen he displayed such virtue, that the author who wrote of him said that he lacked nothing of being a monarch excepting a kingdom. Hiero disbanded the old army and organized a new one; he abandoned his old allies and formed new alliances; and having thus an army and allies of his own creation, he had no difficulty in erecting any edifice upon such a foundation; so that although he had much trouble in attaining the principality, yet he had but little in maintaining it.

CHAPTER VII.

of new principalities that have been acquired by the aid of others and by good fortune.

Those who by good fortune only rise from mere private station to the dignity of princes have but little trouble in achieving that elevation, for they fly there as it were on wings; but their difficulties begin after they have been placed in that high position. Such are those who acquire a state either by means of money, or by the favor of some powerful monarch who bestows it upon them. Many such instances occurred in Greece, in the cities of Ionia and of the Hellespont, where men were made princes by Darius so that they might hold those places for his security and glory. And such were those Emperors who from having been mere private individuals attained the Empire by corrupting the soldiery. These remain simply subject to the will and the fortune of those who bestowed greatness upon them, which are two most uncertain and variable things. And generally these men have neither the skill nor the power to maintain that high rank. They know not (for unless they are men of great genius and ability, it is not reasonable that they should know) how to command, having never occupied any but private stations; and they cannot, because they have no troops upon whose loyalty and attachment they can depend.

Moreover, states that spring up suddenly, like other things in nature that are born and attain their growth rapidly, cannot have those roots and supports that will protect them from destruction by the first unfavorable weather. Unless indeed, as has been said, those who have suddenly become princes are gifted with such ability that they quickly know how to prepare themselves for the preservation of that which fortune has cast into their lap, and afterwards to build up those foundations which others have laid before becoming princes.

In illustration of the one and the other of these two ways of becoming princes, by valor and ability, or by good fortune, I will adduce two examples from the time within our own memory; these are Francesco Sforza and Cesar Borgia. Francesco, by legitimate means and by great natural ability, rose from a private citizen to be Duke of Milan; and having attained that high position by a thousand efforts, it cost him but little trouble afterwards to maintain it. On the other hand, Cesar Borgia, commonly called Duke Valentino, acquired his state by the good fortune of his father, but lost it when no longer sustained by that good fortune; although he employed all the means and did all that a brave and prudent man can do to take root in that state which had been bestowed upon him by the arms and good fortune of another. For, as we have said above, he who does not lay the foundations for his power beforehand may be able by great ability and courage to do so afterwards; but it will be done with great trouble to the builder and with danger to the edifice.

If now we consider the whole course of the Duke Valentino, we shall see that he took pains to lay solid foundations for his future power; which I think it well to discuss. For I should not know what better lesson I could give to a new prince, than to hold up to him the example of the Duke Valentino’s conduct. And if the measures which he adopted did not insure his final success, the fault was not his, for his failure was due to the extreme and extraordinary malignity of fortune. Pope Alexander VI. in his efforts to aggrandize his son, the Duke Valentino, encountered many difficulties, immediate and prospective. In the first place he saw that there was no chance of making him master of any state, unless a state of the Church; and he knew that neither the Duke of Milan nor the Venetians would consent to that. Faenza and Rimini were already at that time under the protection of the Venetians; and the armies of Italy, especially those of which he could have availed himself, were in the hands of men who had cause to fear the power of the Pope, namely the Orsini, the Colonna, and their adherents; and therefore he could not rely upon them.

It became necessary therefore for Alexander to disturb the existing order of things, and to disorganize those states, in order to make himself safely master of them. And this it was easy for him to do; for he found the Venetians, influenced by other reasons, favorable to the return of the French into Italy; which not only he did not oppose, but facilitated by dissolving the former marriage of King Louis XII. (so as to enable him to marry Ann of Brittany). The king thereupon entered Italy with the aid of the Venetians and the consent of Alexander; and no sooner was he in Milan than the Pope obtained troops from him to aid in the conquest of the Romagna, which was yielded to him through the influence of the king.

The Duke Valentino having thus acquired the Romagna, and the Colonna being discouraged, he both wished to hold that province, and also to push his possessions still further, but was prevented by two circumstances. The one was that his own troops seemed to him not to be reliable, and the other was the will of the king of France. That is to say, he feared lest the Orsini troops, which he had made use of, might fail him at the critical moment, and not only prevent him from acquiring more, but even take from him that which he had acquired; and that even the king of France might do the same. Of the disposition of the Orsini, the Duke had a proof when, after the capture of Faenza, he attacked Bologna, and saw with what indifference they moved to the assault. And as to the king of France, he knew his mind; for when he wanted to march into Tuscany, after having taken the Duchy of Urbino, King Louis made him desist from that undertaking. The Duke resolved therefore to rely no longer upon the fortune or the arms of others. And the first thing he did was to weaken the Orsini and the Colonna in Rome, by winning over to himself all the gentlemen adherents of those houses, by taking them into his own pay as gentlemen followers, giving them liberal stipends and bestowing honors upon them in proportion to their condition, and giving them appointments and commands; so that in the course of a few months their attachment to their factions was extinguished, and they all became devoted followers of the Duke.

After that, having successfully dispersed the Colonna faction, he watched for an opportunity to crush the Orsini, which soon presented itself, and of which he made the most. For the Orsini, having been slow to perceive that the aggrandizement of the Duke and of the Church would prove the cause of their ruin, convened a meeting at Magione, in the Perugine territory, which gave rise to the revolt of Urbino and the disturbances in the Romagna, and caused infinite dangers to the Duke Valentino, all of which, however, he overcame with the aid of the French. Having thus re-established his reputation, and trusting no longer in the French or any other foreign power, he had recourse to deceit, so as to avoid putting them to the test. And so well did he know how to dissemble and conceal his intentions that the Orsini became reconciled to him, through the agency of the Signor Paolo, whom the Duke had won over to himself by means of all possible good offices, and gifts of money, clothing, and horses. And thus their credulity led them into the hands of the Duke at Sinigaglia.

The chiefs thus destroyed, and their adherents converted into his friends, the Duke had laid sufficiently good foundations for his power, having made himself master of the whole of the Romagna and the Duchy of Urbino, and having attached their entire population to himself, by giving them a foretaste of the new prosperity which they were to enjoy under him. And as this part of the Duke’s proceedings is well worthy of notice, and may serve as an example to others, I will dwell upon it more fully.

Having conquered the Romagna, the Duke found it under the control of a number of impotent petty tyrants, who had devoted themselves more to plundering their subjects than to governing them properly, and encouraging discord and disorder amongst them rather than peace and union; so that this province was infested by brigands, torn by quarrels, and given over to every sort of violence. He saw at once that, to restore order amongst the inhabitants and obedience to the sovereign, it was necessary to establish a good and vigorous government there. And for this purpose he appointed as governor of that province Don Ramiro d’Orco, a man of cruelty, but at the same time of great energy, to whom he gave plenary power. In a very short time D’Orco reduced the province to peace and order, thereby gaining for him the highest reputation. After a while the Duke found such excessive exercise of authority no longer necessary or expedient, for he feared that it might render himself odious. He therefore established a civil tribunal in the heart of the province, under an excellent president, where every city should have its own advocate. And having observed that the past rigor of Ramiro had engendered some hatred, he wished to show to the people, for the purpose of removing that feeling from their minds, and to win their entire confidence, that, if any cruelties had been practised, they had not originated with him, but had resulted altogether from the harsh nature of his minister. He therefore took occasion to have Messer Ramiro put to death, and his body, cut into two parts, exposed in the market-place of Cesena one morning, with a block of wood and a bloody cutlass left beside him. The horror of this spectacle caused the people to remain for a time stupefied and satisfied.

But let us return to where we started from. I say, then, that the Duke, feeling himself strong enough now, and in a measure secure from immediate danger, having raised an armed force of his own, and having in great part destroyed those that were near and might have troubled him, wanted now to proceed with his conquest. The only power remaining which he had to fear was the king of France, upon whose support he knew that he could not count, although the king had been late in discovering his error of having allowed the Duke’s aggrandizement. The Duke, therefore, began to look for new alliances, and to prevaricate with the French about their entering the kingdom of Naples for the purpose of attacking the Spaniards, who were then engaged in the siege of Gaeta. His intention was to place them in such a position that they would not be able to harm him; and in this he would have succeeded easily if Pope Alexander had lived.

Such was the course of the Duke Valentino with regard to the immediate present, but he had cause for apprehensions as to the future; mainly, lest the new successor to the papal chair should not be friendly to him, and should attempt to take from him what had been given him by Alexander. And this he thought of preventing in several different ways: one, by extirpating the families of those whom he had despoiled, so as to deprive the Pope of all pretext of restoring them to their possessions; secondly, by gaining over to himself all the gentlemen of Rome, so as to be able, through them, to keep the Pope in check; thirdly, by getting the College of Cardinals under his control; and, fourthly, by acquiring so much power before the death of Alexander that he might by himself be able to resist the first attack of his enemies. Of these four things he had accomplished three at the time of Alexander’s death; for of the petty tyrants whom he had despoiled he had killed as many as he could lay hands on, and but very few had been able to save themselves; he had won over to himself the gentlemen of Rome, and had secured a large majority in the sacred college; and as to further acquisitions, he contemplated making himself master of Tuscany, having already possession of Perugia and Piombino, and having assumed a protectorate over Pisa. There being no longer occasion to be apprehensive of France, which had been deprived of the kingdom of Naples by the Spaniards, so that both of these powers had to seek his friendship, he suddenly seized Pisa. After this, Lucca and Sienna promptly yielded to him, partly from jealousy of the Florentines and partly from fear. Thus Florence saw no safety from the Duke, and if he had succeeded in taking that city, as he could have done in the very year of Alexander’s death, it would have so increased his power and influence that he would have been able to have sustained himself alone, without depending upon the fortune or power of any one else, and relying solely upon his own strength and courage.

But Alexander died five years after the Duke had first unsheathed his sword. He left his son with only his government of the Romagna firmly established, but all his other possessions entirely uncertain, hemmed in between two powerful hostile armies, and himself sick unto death. But such were the Duke’s energy and courage, and so well did he know how men are either won or destroyed, and so solid were the foundations which he had in so brief a time laid for his greatness, that if he had not had these two armies upon his back, and had been in health, he would have sustained himself against all difficulties. And that the foundations of his power were well laid may be judged by the fact that the Romagna remained faithful, and waited quietly for him more than a month; and that, although half dead with sickness, yet he was perfectly secure in Rome; and that, although the Baglioni, Vitelli, and Orsini came to Rome at the time, yet they could not raise a party against him. Unable to make a Pope of his own choice, yet he could prevent the election of any one that was not acceptable to him. And had the Duke been in health at the time of Alexander’s death, everything would have gone well with him; for he said to me on the day when Julius II. was created Pope, that he had provided for everything that could possibly occur in case of his father’s death, except that he never thought that at that moment he should himself be so near dying.

Upon reviewing now all the actions of the Duke, I should not know where to blame him; it seems to me that I should rather hold him up as an example (as I have said) to be imitated by all those who have risen to sovereignty, either by the good fortune or the arms of others. For being endowed with great courage, and having a lofty ambition, he could not have acted otherwise under the circumstances; and the only thing that defeated his designs was the shortness of Alexander’s life and his own bodily infirmity.

Whoever, then, in a newly acquired state, finds it necessary to secure himself against his enemies, to gain friends, to conquer by force or by cunning, to make himself feared or beloved by the people, to be followed and revered by the soldiery, to destroy all who could or might injure him, to substitute a new for the old order of things, to be severe and yet gracious, magnanimous, and liberal, to disband a disloyal army and create a new one, to preserve the friendship of kings and princes, so that they may bestow benefits upon him with grace, and fear to injure him, — such a one, I say, cannot find more recent examples than those presented by the conduct of the Duke Valentino. The only thing we can blame him for was the election of Julius II. to the Pontificate, which was a bad selection for him to make; for, as has been said, though he was not able to make a Pope to his own liking, yet he could have prevented, and should never have consented to, the election of one from amongst those cardinals whom he had offended, or who, if he had been elected, would have had occasion to fear him, for either fear or resentment makes men enemies.

Those whom the Duke had offended were, amongst others, the Cardinals San Pietro in Vincola, Colonna, San Giorgio, and Ascanio. All the others, had they come to the pontificate, would have had to fear him, excepting D’Amboise and the Spanish cardinals; the latter because of certain relations and reciprocal obligations, and the former because of his power, he having France for his ally. The Duke then should by all means have had one of the Spanish cardinals made Pope, and failing in that, he should have supported the election of the Cardinal d’Amboise, and not that of the Cardinal San Pietro in Vincola. For whoever thinks that amongst great personages recent benefits will cause old injuries to be forgotten, deceives himself greatly. The Duke, then, in consenting to the election of Julius II. committed an error which proved the cause of his ultimate ruin.

CHAPTER VIII.

of such as have achieved sovereignty by means of crimes.