EUROPE, EMPIRE & WAR: PART 1.

"THE LONG 19TH CENTURY, 1789-1914"

Course and Seminar Guide

[Updated: 27 October, 2024 ]

|

|

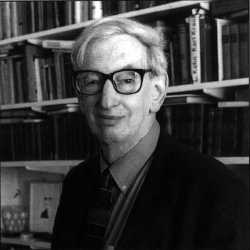

| The "liberal" Course textbook: Theodore Hamerow, The Birth of a New Europe (1983) | The "Marxist" course textbook: Eric Hobsbawm, The Age of Revolution, 1789-1848 (1962) |

This is part of a collection of material on the history of the classical liberal tradition.

Note: There are also links to the lecture notes I used when giving this course.

Table of Contents

Some General Information about the Course

I. OVERVIEW

The subject will deal with the remarkable transformation of European society which took place between the outbreak of the French Revolution in 1789 to the beginning of the First World War in 1914. The guiding principle of the subject is the idea of "opposing voices and contested meanings" - in other words, that the changes taking place in 19th century European society were supported by some groups and indivudals and opposed by others (the "opposing voices"), and that historians have been deeply divided in their interpretation of the meaning and significance of these changes (the "contested meanings").

The approach I will take in the lectures is a thematic one. I will discuss a number of themes dealing with the Economy and Society; Class, Power & Revolution; Political Thought; State, Empire and War; Liberty; and Ideas and Culture, in a chronological, comparative and analytical fashion. In the tutorials we will discuss some of the "opposing voices and contested meanings" including:

- the impact of the "twin revolutions" (the French and Industrial Revolutions) on ordinary people

- the impact of the "political revolution"

- the recurring problem of revolution and the struggle within the new leadership to control its direction

- the transformation of traditional monarchical regimes into liberal democracies/republics

- the use of public ritual and political imagery by regimes (whether republican or monarchical) to gain public support

- the impact of the "economic revolution"

- the impact of the industrial revolution and the globalisation of the economy on European society

- its impact on the conduct of war and the possibilities for imperial expansion

- the idea of "emancipation"

- competing visions of emancipation and reform - Mill's liberalism vs Marx's socialism

- the emancipation of serfs (within Europe) and slaves (in Europe's colonies)

- the emancipation of women

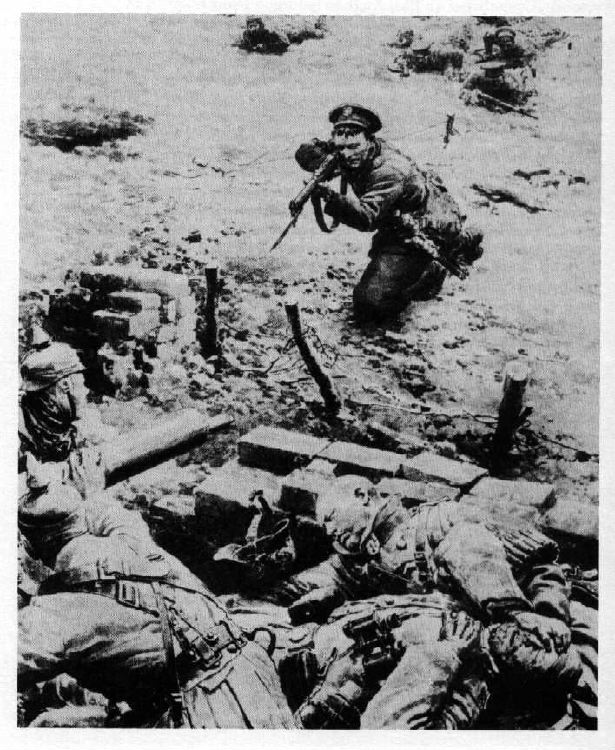

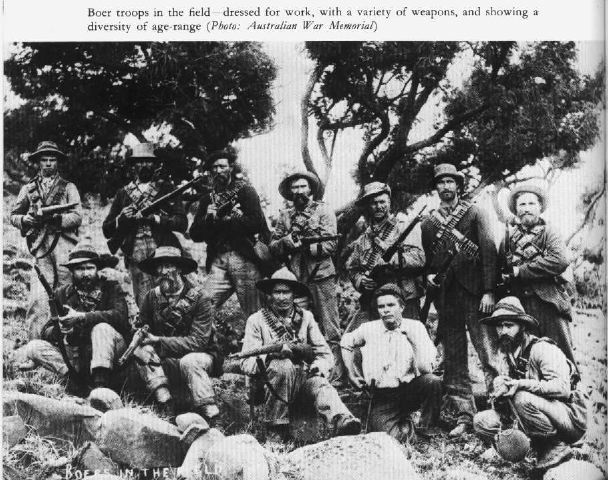

- the problem of "war and empire"

- the impact of war and empire on state-building and the spread of Europeans across the globe

- the moral, legal and military problems faced by the British (and their Australian supporters) in maintaining their Empire

- the development of ideals of personal honour, athleticism and manliness in the elite, middle and working classes which were used to justify war and empire

- the study of history

- the development of essential skills in the areas of research, information technology, critical thinking, essay writing, oral presentation

- using primary and secondary sources - the problem of "opposing voices and contested meanings"

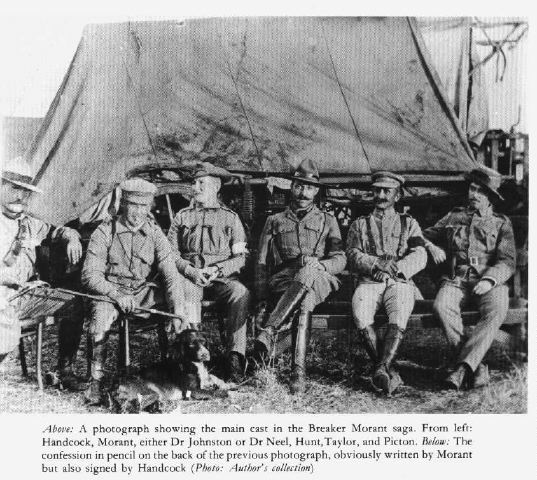

- evaluating the historical accuracy of feature films (e.g. Danton and Breaker Morant)

- the importance of history as a discipline and the significance of the 19thC in general

In addition, there will be a number of Workshop Lectures, Workshop Seminars and Film and History Seminars in which we will develop the skills required for the study of history in particular and of the humanities in general. These include the use of film by historians, the importance of history as a discipline, and essay and research skills. A number of films will be shown with the aim of exploring the accuracy of the history depicted on the screen.

II. AIMS

The aim of this history subject (and of an arts education in general - in my opinion) is to achieve a number of vocational and general educational ends. These include

- the development of essential basic skills which you can use in any career you might wish to pursue: research, information technology, critical thinking, essay writing, oral presentation

- an awareness of the main events and the forces behind the course of European history of the last 250 years, a knowledge of which is essential in order to understand the political, social and economic changes which continue to shape Europe, North America, Asia and Australia

- an understanding of the emergence and evolution of some our most important ideas and values, and legal, economic and political institutions from their European origins

- an understanding of the historical method of analysis including

- an appreciation that historical knowledge is based upon interpretation of primary sources

- an ability to analyse a primary source

- an ability to deal with different historical interpretations of the same event

- an ability to make an historical argument based upon information drawn from primary and secondary sources and specific historical examples

- the capacity to use the BSL, the Internet and computers for research and writing

We plan to pursue these ends in a variety of ways. Some are achieved explicitly, e.g. the Essays and Exercises are designed to develop writing and analytical skills, and some are achieved implicitly, e.g. in general discussion and in the basic assumptions made about the subject.

III. SUBJECT TEXTBOOKS

In keeping with the thematic and comparative approach of the subject, I have chosen two authors - Theodore Hamerow (a conservative liberal) and Eric Hobsbawm (a Marxist) - with very different interpretations of 19thC European history as subject textbooks. Purchase of either the Hamerow book or one of the Hobsbawm books is strongly recommended. Having one of each would be better.

- Theodore S. Hamerow, The Birth of a New Europe: State and Society in the Nineteenth Century (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1983).

- Eric Hobsbawm

- The Age of Revolution, 1789-1848 (1962) (New York: Mentor)

- The Age of Capital, 1848-1875 (1975) (London: Abacus, 1997).

- The Age of Empire, 1875-1914 (1987) (London: Abacus, 1997).

Note: The 4th volume in Hobsbawm's history of Europe is:

- Eric Hobsbawm, The Age of Extremes. A History of the World, 1914-1991 (1994) (New York: Vintage, 1996).

For the Workshop Tutorial on "Writing Better Essays" the following work is recommended:

- Richard Marius, A Short Guide to Writing about History (2nd edition. HarperCollins, 1995).

Those who want a chronological treatment of the subject could try the American textbook by Chambers, the video series by Eugen Weber, and the collection of primary source material by Sherman:

- The Western Experience, Mortimer Chambers et al., vol. 2 (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1995). 6th edition.

- Eugen Weber, The Western Tradition (Boston, Mass.: WGBH and Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 1989)

- Western Civilization: Sources, Images, and Interpretations. Vol. 2: Since 1660, ed. Denis Sherman (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1995). 4th edition.

The textbook for Part 2 of the subject "Europe in a Changing World, 1890-1956" is

- Joel Colton and R.R. Palmer, A History of the Modern World: Europe Since 1815. Vol. IV (McGraw-Hill, 1995).

Other Recommended Works

The extraordinary, long and compendious work by Norman Davies, Europe: A History (London: Pimlico, 1997).

Macmillan is publishing a series of works under the general title of "Themes in Comparative History" ed. Clive Emsley. Titles which are relevant to themes covered in this subject include:

- Pamela Pilbeam, The Middle Classes in Europe, 1789-1914: France, Germany, Italy and Russia (London: Macmillan, 1990).

- Jane Rendall, The Origins of Modern Feminism: Women in Britain, France, and the United States, 1780-1860 (London: Macmillan, 1985)

- Ian Inkster, Science and Technology in History c. 1750-1914 (London: Macmillan, 1991)

- Dominic Lieven, The Aristocracy in Europe, 1815-1914 (New York : Columbia University Press, 1993).

IV. MAKING SENSE OF THE PRIMARY AND SECONDARY SOURCES

One of the most difficult problems confronting students of history is how to make sense of what they read, especially if the historians they read disagree among themselves. To help you come to terms with this problem the lectures and Seminars will give you some practice in handling what I call "opposing voices and contested meanings". Wherever possible, we will examine different points of view - some expressed by contemporaries or eyewitnesses to the events in question (the "opposing voices"), others expressed by historians writing much later in an attempt to make sense of what happened in the past (the "contested meanings"). The Textbooks have been selected to bring out as clearly as possible this "contest" over the meaning of the past. Hamerow is a liberal conservative and Hobsbawm is a Marxist and their different interpretations of 19th century European history should provide a basis for our own discussion.

In all your written work you will be expected to use and discuss the textbooks (Hamerow and Hobsbawm), any relevant primary sources (extracts from printed collections, the film/s, contemporary art or photographs), and other secondary sources (monographs (whole books devoted to the subject), essays in books, and journal articles) - many of which are listed in the Reading Guide.

1. The Problem of "Opposing Voices" (Primary Sources)

In many Seminars we will examine closely one or more primary sources or documents from the Reader of Primary Sources. In some cases they will have starkly different stories to tell - some will strenuously oppose the event or change taking place, others will support it just as strenuously, yet others will be confused. What sense can historians make of these "opposing voices" from the past? Before analysing the document itself you will have to do some background reading of the Textbooks or the secondary sources listed in the Reading Guide. Having done this background reading you then need to analyse the document. In many cases you will have to "read between the lines" as much important information will not be stated explicitly but can be extracted only by examining the document's historical context and the biases, preconceptions, and expectations of the author. Some of the Primary Sources will be printed documents (published books or pamphlets, parliamentary reports or debates). Other Primary Sources will be images (such as works of art, etchings, photographs).

2. The Problem of "Contested Meanings" (Historiography)

Not only do the primary sources give different perspectives on what happened in the past but also historians differ greatly in what they say happened and what these events mean to the modern reader. This is the general problem of the "contested meaning" of history. In all the Seminars we will discuss how the reader can make sense of the vastly different intrerpretations of history offered by conservatives, classical liberals, Marxists, nationalists, feminists, and others. The two textbooks for the subject - one written by a Marxist (Hobsbawm) and the other written by a liberal (Hamerow) - should provide the starting point for our discussion. Other secondary sources listed in the Reading Guide should show this problem even more clearly, especially in formal historiographical disputes among historians over the interpretation and meaning of a number of historical events or problems. Students will be asked to "take sides" in the dispute by arguing for one of the interpretations of the events in question.

3. Film as an Historical Source

We will explore how film can be used by historians both as an historical source which provides information about the past and as a way of interpreting the past. You are required to attend one of the Film Sessions and to write one of your Exercises on that film. The task is to examine one or more primary sources in order to assess the historical accuracy of the film. To do this you will have to do some reading on the persons or events depicted on the screen in order to get some historical background. You then need to see the film (more than once if at all possible) and historically and critically evaluate what you have seen. You should also find out as much as you can about the filmmakers (director, screenwriter, historical advisor, etc), their reasons for making the film as they did, the historical context in which the film was made, and the reception of the film when it was released.

4. Using Primary Sources

When dealing with primary sources (documents) in many cases you will have to "read between the lines" as much important information will not be stated explicitly but can be extracted only by examining the document's historical context and the biases, preconceptions, and expectations of the author. Some things to consider when analysing the document are the following (this list is only a guideline):

- where did the source come from (a dusty archive or library, or an edited and printed collection of documents)?

- who edited the collection?

- who wrote (or painted) it?

- when was the document written (painted, recorded)?

- what is the author/speaker's class background, their nationality, their political perspective, their gender, their religion?

- why was it written (painted)?

- who is the author's audience?

- did it achieve the purpose of the author?

- whose "voice" are we hearing? is the author speaking for him/herself or on behalf of others?

- what was the historical context in which the document was created?

- how is it written (constructed, composed)? what syle does the author use? what rhetorical devices are used? are they effective?

- what does the document say?

- what doesn't it say (or leave out)? and why does the author leave this out?

- is the document accurate in what it does say? does the author "bend" the truth? if so, why?

- how can or should an historian use this document in order to understand the past?

5. Using Secondary Sources

- what primary sources did the historian (filmmaker) use?

- have you checked any of these sources to see if they are correct?

- what primary sources did the historian NOT use?

- did the historian favour sources from a particular class, gender, country, period over other possible sources?

- or a particular kind of source (such as official government records, memoirs of the educated elite, works of art, political iconography)?

- what secondary sources (i.e. the works of other historians) did the historian use?

- to what extent is the work based upon "original research" or the work of other historians?

- what is the perspective (bias) of the historian?

- does the historian belong to a particular "school of thought"?

- if so, does this matter?

6. Matters Relevant to all Types of Sources (Primary, Secondary - Printed, Film, Art)

- from all sources the reader can get both information (what happened) and interpretation (why it happened, what it means)

- ask yourself, what information can the reader/viewer get from the source?

- what information is withheld (absent, omitted)? (hint: you might need to read other sources to answer this question)

- what interpretation of events does the author of the document (filmmaker) provide?

- is this interpretation deliberate (intentional) or implicit (unintentional)?

- can you confirm/corroborate or contradict by using other sources the information imparted by the document?

- how can knowledge of the historical context in which the document was produced help to extract information contained in the document and/or understand the interpretation/perspective of the author?

7. Reaching a Conclusion

The final stage of the Essay/Exercise is to state your conclusion or answer to the problem under discussion. This should be based upon the information and interpretations you have gleaned from reading both primary and secondary sources. The questions you should keep in mind include the following:

- what information have I got from what I have read?

- what specific examples have I come across?

- what arguments (conclusions, interpretations, explanations) have I got from what I have read?

- what is the perspective (bias) of the sources I have read?

- how reliable are the sources I have read?

- what particular perspective have they given me?

- what have they left out?

- are the examples, arguments, conclusions given in the sources convincing to me?

- what conclusion might historians with different perspectives reach on this question?

- e.g. a liberal, conservative, Marxist, feminist, nationalist, etc?

- what is my own pespective on this question/issue?

- whose evidence, examples, arguments, conclusions do I ultimately find most convincing?

- why?

Lecture and Film program for "The Long 19th Century" (S1 1999):

- Introduction I1 - Historical Geography of Europe - Legacy of the Past

-

Introduction II - The "Long 19thC"

- Textbook Exercise: Hamerow & Hobsbawm interpret the 19thC

- Political Authority & Class Rule I - Power & Privilege in Traditional States

- Political Authority & Class Rule II - Images of Monarchs, Emperors, & Republics

- The Struggle for Liberty I - Struggle for Liberty in 19thC - Chronology of the French Revolution

- The Struggle for Liberty II - Slavery and its Abolition

- The Struggle for Liberty III - Emancipation of the Serfs

- The Struggle for Liberty IV - Emancipation of Women

- Ideologies of Emancipation I - Liberalism (Mill) - 19thC Liberalism & Socialism compared

- Ideologies of Emancipation II - Socialism (Marx)

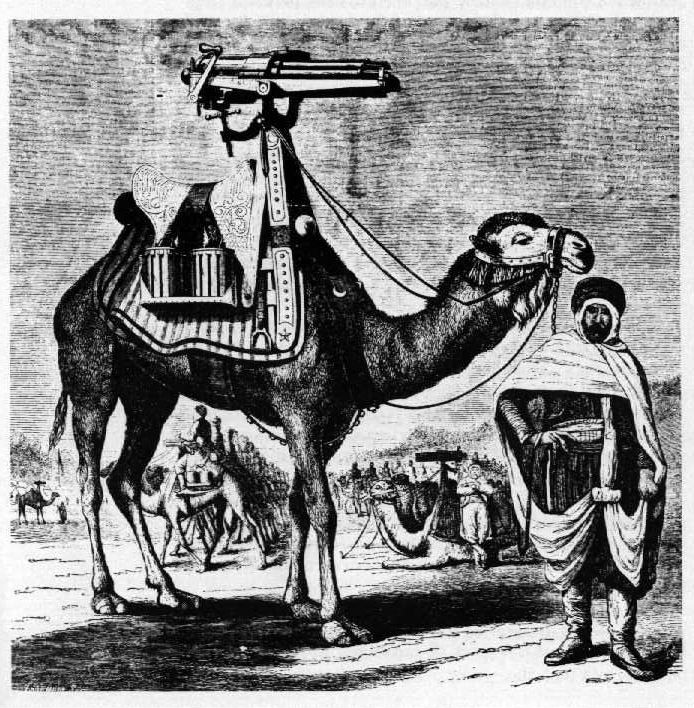

- State, Empire & War I - Empires & Colonies

- State, Empire & War II - War & State-Making

- Economic Revolution I - The Industrial Revolution & its Impact on Ordinary People

- Economic Revolution II - Impact of the Industrial Revolution on War & Imperialism

- Ideas & Culture I - "High" Culture

- Ideas & Culture II - Popular Culture

- Ideas & Culture III - Science & Technology

- Conclusion I - Fin de siècle- the End of an Era?

- Conclusion II - The Importance of (19thC) History

Films:

- Documentary: Ken Burns "The Statue of Liberty"

- The French Revolution: Andrzej Wajda, Danton (1982) 2hrs 16

- Napoleon: Abel Gance, Napoleon (1927) Part 1 2hrs

- Napoleon: Abel Gance, Napoleon (1927) Part 2 1hr 51

- 19thC Slavery - Steven Spielberg, Amistad (1997) 2hrs 35

- The Industrial Revolution - René Clément, Gervaise (1956) 1hr 50

- War & Empire (Crimean War) - Tony Richardson, Charge of the Light Brigade (1968) 2hrs 5

- War & Empire (Boer War): Bruce Beresford, Breaker Morant (1980) 1hr 47

TOPICS FOR DISCUSSION IN THE WEEKLY SEMINARS

I. An Introduction to the Study of the "Long 19th Century"

|

|

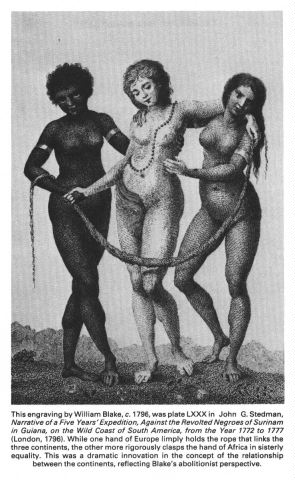

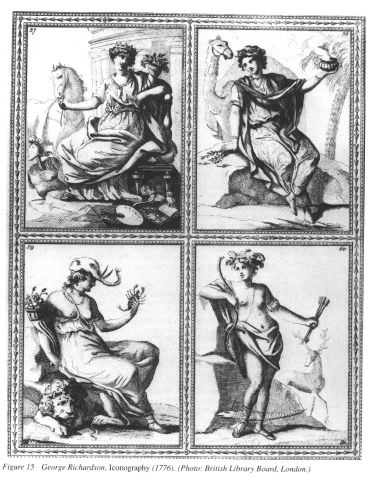

| William Blake, "Europe Supported by Africa and America" (1793) | Idealized depictions of "Europe", "Africa", "Asia" and "America" (1776) |

[See the Lecture Notes for this topic.]

SEMINAR DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

1. Maps in the Reader of Primary Sources

Familiarize yourselves with the maps in the Reader of Primary Sources

- Geographical maps

- the physiography of Europe (Mortimer Chambers)

- Physical regions (Davies)

- Political maps

- the European States in 1789 (Doyle)

- the European States c. 1800 (Doyle)

- Europe in 1878 (Joll)

- the Colonial Empires, 1914 (Fieldhouse)

- Europe on the Eve of WW1 (Gilbert)

- Other maps

- the languages of Europe

- East-West fault lines (Davies)

2. General Discussion Questions

Some basic questions to consider (for this Seminar, the Textbook Seminar and for the subject as a whole) include the following:

- why should one study the 19th century? why are you studying this subject?

- who are the people/s known as "Europeans"?

- where and what is "Europe"?

- what have been, were in the 19thC and now are, the geographical boundaries of "Europe"?

- what ethnic, religious, linguistic, dynastic, political, economic, diplomatic, intellectual, cultural, or other forces have contributed most to shaping a common "European" experience or identity?

- when, if at all, did "Europeans" become self-conscious of this common experience or identity?

- familiarize yourselves with the maps in the Reader of Primary Sources

- Geographical maps

- the physiography of Europe (Mortimer Chambers)

- Physical regions (Davies)

- Political maps

- the European States in 1789 (Doyle)

- the European States c. 1800 (Doyle)

- Europe in 1878 (Joll)

- the Colonial Empires, 1914 (Fieldhouse)

- Europe on the Eve of WW1 (Gilbert)

- Other maps

- the languages of Europe

- East-West fault lines (Davies)

- discuss the issue of the "periodization" of history

- how have historians traditionally divided up the past into "periods" or "ages" or "eras"?

- what defines a particular "period" from what has gone before and what has come after? (e.g. ancient, medieval, early modern, modern, post-modern)?

- what, if anything, distinguishes "the 19th century" from what went before and what came after?

- when did the "19thC" begin and end?

- why do some historians (like me!) refer to the "long 19thC"? or even the "longer 19thC" (i.e. 1789-1918)

- draw up and discuss a chronology of the major events of the 19th century (e.g. wars, revolutions, the unifications of states, etc)

- what are the strengths and weaknesses of studying (19thC European) history from the following perspectives:

- chronogically (e.g. from 1789 to 1914)

- from a "national" perspective (e.g. separate histories of France, Britain, Germany)

- comparatively (comparing and contrasting French, British, German history over the same period)

- thematically (identifying certain "themes" and discussing them in a comparative and chronological fashion - e.g. women's history, economic history)

- ideologically (e.g. offering a Marxist, liberal or feminist interpretation of history)

C. ADDITIONAL RECOMMENDED READING

Please note: The full bibliography is only available online.

1. The Historical Geography of 19th Century Europe

The Penguin Atlas of World History, 2 vols., ed. Herman Kinder and Werner Hilgermann (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1978). Volume 2 deals with the period From the French Revolution to the Present.

Norman J.G. Pounds, An Historical Geography of Europe, 1500-1840 (Cambridge University Press, 1979).

2. Chronology of Major Events and Dictionaries

The Penguin Dictionary of Modern History, 1789-1945, ed. Alan Palmer, 2nd edition (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1983).

The Penguin Dictionary of Twentieth-Century History, 1900-1989, ed. Alan Palmer, 2nd edition (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1990).

3. Other Works on "19th Century" European History

History on the Internet

The Barr Smith Library's "Library Information Services History Home Page": http://library.adelaide.edu.au/guide/hum/history

Dennis A. Trinkle et al., The History Highway: A Guide to Internet Resources (Armonk, New York: M.E. Sharpe, 1997). The History Highway Website is: http://www.uc.edu/www/history/highway.html

Historiography

An older collection of historical opinion about the 19thC: A Century for Debate, 1789-1914: Problems in the Interpretation of European History, ed. Peter N. Stearns (New York: Dodd, Mead & Co., 1975). Chap. XV "The Nature of the Nineteenth Century" - essays by Ford, Murray, Keynes, Croce, Hayes, Mosse, pp. 472-511.

General Works

Grant and Temperley's Europe in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries (7th ed.) volume 1 by Agatha Ramm, Europe in the Nineteenth Century, 1789-1905 (London: Longman, 1984).

Robert Gildea, Barricades and Borders: Europe 1800-1914 (Oxford University Press, 1987).

Chris Cook and John Paxton, European Political Facts, 1789-1848 (Macmillan, 1981).

Chris Cook and John Paxton, European Political Facts, 1848-1918 (New York: Facts on File, 1978).

France

Roger Magraw, France 1815-1914: The Bourgeois Century (Fontana, 1983).

The German States/Germany/Austria

James Sheehan, German History 1770-1866 (Oxford University Press, 1990).

Gordon Craig, Germany 1866-1945 (Oxford University Press, 1980).

B. Jelavich, Modern Austria: Empire and Republic, 1815-1986 (Cambridge University Press, 1987).

Britain

Norman McCord, British History, 1815-1906 (Oxford University Press, 1991).

4. The Idea of "Europe"

The History of the Idea of Europe, ed. Kevin Wilson and Jan van der Dussen (London: Routledge, 1995).

Culture and Identity in Europe: Perceptions of Divergence and Unity in Past and Present, ed. Michael Wintle (Aldershot: Avebury, 1996).

Denys Hay, Europe: The Emergence of an Idea (New York: Harper Torchbooks, 1966).

Die Idee Europa, 1300-1946: Quellen zur Geschichte der politischen Einigung, ed. Rolf Hellmut Foester (dtv documente1963).

5. The Uniqueness of Europe

E.L. Jones, The European Miracle: Environments, Economies and Geopolitics in the History of Europe and Asia (Cambridge University Press, 1981).

Nathan Rosenberg and L.E. Birdzell, Jr., How the West Grew Rich: The Economic Transformation of the Industrial World (New York: Basic Books, 1986).

J.M. Roberts, The Triumph of the West (London: BBC, 1985).

6. The Making of Europe

The Oxford, Blackwell series "The Making of Europe" ed. Jacques Le Goff:

- Charles Tilly, European Revolutions, 1492-1992 (1993)

- Leonardo Benevolo, The European City (1993)

- Michel Mollat du Jourdin, Europe and the Sea (1993)

- Josep Fonatan i Lazaro, The Distorted Past: A Reinterpretation of Europe (1995)

- Massimo Montanari, The Culture of Food (1994)

- Werner Rosener, The Peasantry of Europe: from the 6th Century to the Present (1994)

- Umberto Eco, The Search for the Perfect Language (1994)

7. Art and History

Francis Haskell, History and its Images: Art and the Interpretation. of the Past (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1993).

Susan Woodford, Looking at Pictures (Cambridge University Press, 1995).

Art and History: Images and their Meaning, ed. Robert I. Rotberg and Theodore K. Rabb (Cambridge University Press, 1988).

Albert Boime, A Social History of Modern Art (University of Chicago Press)

- Volume 1 - Art in an Age of Revolution, 1750-1800 (1987)

- Volume 2 - Art in an Age of Bonapartism, 1800-1815 (1990)

II. Introduction to the Textbooks: Comparing and Contrasting Hamerow & Hobsbawm's Approaches to the Study of the 19th Century

|

A. SEMINAR READING AND DISCUSSION

1. Textbook Reading

Selectively read one of the following subject textbooks by Hamerow (from a liberal perspective) or Hobsbawm (from a Marxist perspective):

- Theodore S. Hamerow, The Birth of a New Europe: State and Society in the Nineteenth Century (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1983).

- Eric Hobsbawm's trilogy of books on the 19thC:

- The Age of Revolution, 1789-1848 (1962) (New York: Mentor)

- The Age of Capital, 1848-1875 (1975) (London: Abacus, 1997).

- The Age of Empire, 1875-1914 (1987) (London: Abacus, 1997).

Note: It is not necessary to read all three volumes of Hobsbawm and Hamerow's textbook for this seminar! Begin by reading the introduction and conclusion to the volume (or volumes) you have chosen, then use the table of contents and index to find other bits to skim.

2. Questions to Keep in Mind when Reading

We should begin by asking ourselves "who are the people who have written our textbooks?" We need to know something about:

- biographical details of the authors (where they born born, where and what they studied, where they have taught and researched)

- their area of academic research and their major publications (monographs/books, journal articles, textbooks and more general works)

- the approach, method, perspective taken in their work - what are the strengths and weaknesses of their respective approaches to the topic?

- the reception of their work in scholarly journals and popular but serious magazines (reviews of their books by other historians and scholars)

A useful exercise is to compare (to find similarities) and contrast (to find differences) the interpretation of 19th century European history of Theodore Hamerow and Eric Hobsbawm, in particular their interpretation of the impact and importance of the "twin revolutions" of the 19thC (i.e. the French and Industrial Rdevolutions). Some of the points you might like to consider were raised in last week's tutorial concerning periodization, key events and processes, method, and so on:

Concerning Theodore Hamerow, The Birth of a New Europe (1983)

- what is Hamerow's political perspective?

- what beginning and end points to the 19thC does Hamerow use?

- why does he think this period is important?

- what is his definition of "Europe"? what countries does he concentrate on?

- what does he mean by "New Europe"?

- what themes has he chosen to discuss? why did he choose these themes and not others? what themes has he ignored?

- what type of history has Hamerow written (e.g. political, economic, military, social, femininst, intellectual history?)

- what is his attitude to the "twin revolutions" (the French Revolution, the Industrial Revolution)

Concerning Eric Hobsbawm, The Age of Revolution, 1789-1848 (1962);The Age of Capital, 1848-1875 (1975);The Age of Empire, 1875-1914 (1987)

- what is Hobsbawm's political perspective?

- what does Hobsbawm mean by "age"?

- why does he divide the "19thC" into three "ages"?

- what events does Hobsbawm use to begin and end his "ages"?

- why does he think these "ages" and this period are important?

- what is his definition of "Europe"? what countries does he concentrate on?

- has his approach changed between the appearance of the first volume in 1962 and the third in 1987?

- what themes has he chosen to discuss? why did he choose these themes and not others? what themes has he ignored?

- what type of history has Hobsbawm written (e.g. political, economic, military, social, femininst, intellectual history?)

- what is his attitude to the "twin revolutions" (the French Revolution, the Industrial Revolution)

How do other historians (like Ramm and Gildea) approach the subject?

B. TOPIC FOR THE "TEXTBOOK EXERCISE"

Everyone should write and bring to the Seminar a 500 word paper on one of the following topics about either Hamerow or Hobsbawm:

- Biography - Who is Hamerow/Hobsbawm? To answer this question you should look for biographical information in their books (often supplied by the publishers), in biographical dictionaries, "Who's who", obituaries (if they have died!). Things we want to know include: Who are thery, what do they look like, where were they born, where did they study history, where have they taught, what major events occurred during their lifetime and what impact (if any) has this had on their interpretation of history?

- Bibliography - What have they written? To answer this question you might search the Barr Smith Library computer catalogue (under "Author" - "Sort List" by "date" to get a chronological listing), an online academic database like "Expanded Academic Index", or biographical or bibliographical essays on the author.

- Reception - What do other historians think about their work? To answer this question you could look at reviews of their books in academic journals and serious magazines. Refer to at least 2 reviews of their work in your answer.

- Historiography - What is their approach to the study of the 19th century? To answer this question you could select a theme or topic covered by one of the authors (say, their interpretation of one of the "twin revolutions" of the 19thC such as the French Revolution or the Industrial Revolution) and describe how they think it changed European society and why they think it is significant.

C. ADDITIONAL RECOMMENDED READING

Please note: The full bibliography is only available online.

1. Biographical and Bibliographical Information

General Works

The Blackwell Dictionary of Historians, ed. J. Canon et al. (Oxford: Blackwell, 1988).

Great Historians of the Modern Age: An International Dictionary, ed. L. Boia (1991).

Theodore Hamerow

Jean-Pierre v. m. Herubel, "CLIO'S DARK MUSINGS?: A REVIEW ESSAY", Libraries & Culture, 1988 23(4): 493-498.

Eric Hobsbawm

Eugene D. Genovese, "The Politics of Class Struggle in the History of Society: An Appraisal of the Work of Eric Hobsbawm," in The Power of the Past: Essays for Eric Hobsbawm, ed. Pat Thane et al. (Cambridge University Press, 1984), pp. 13-36

Keith McClelland, "Bibliography of the Writings of Eric Hobsbawm," (up to 1982) in Culture, Ideology and Politics: Essays for Eric Hobsbawm, ed. Raphael Samuel and Gareth Stedman Jones (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1982), pp. 332-63.

2. Book Reviews in Scholarly Journals and Serious Magazines

Combined Retrospective Index to Book Reviews in Scholarly Journals (1886-1974). 15 vols. 1979-1982.

Book Review Digest (1905-)

Book Review Index (1905-).

Humanites Index (1907-). CD-ROM from 1984-

Social Sciences Index (1907-). CD-ROM from 1983-

Arts and Humanities Citation Index (1976-). CD-ROM from 1992-

Seminar Topic I. Danton, Robespierre and the French Revolution

|

A. SEMINAR READING AND DISCUSSION

1. Textbook Reading

Theodore S. Hamerow, The Birth of a New Europe (1983). A very striking omission in Hamerow's book is a separate chapter dealing with the problem of revolution in general in the 19thC and the imapct of the French Revolution in particular. Why is this?

Eric Hobsbawm - as one might expect from a Marxist, revolution plays a very important part in Hobsbawm's accounts, both as the legacy of the French Revolution and as a foretaste of what is to come in the socialist revolutions of the 20th century.

- The Age of Revolution, 1789-1848 (1962): Chap. 3 "The French Revolution"; Chap. 6 "Revolutions"; Chap. 16 "Conclusion: Towards 1848"

- The Age of Capital, 1848-1875 (1975): Chap 1 "'The Springtime of the Peoples'";

- The Age of Empire, 1875-1914 (1987): Chap 1. "The Centarian Revolution"; Chap. 12 "Towards Revolution"

2. Background Reading - Secondary Sources ("Contested Meaning")

Hobsbawm's defense of Marxist interpretations of the French Revolution on the occasion of the bicentennial: E.J. Hobsbawm, Echoes of the Marseillaise: Two Centuries Look Back on the French Revolution (London: Verso, 1990).

The Permanent Revolution: The French Revolution and its Legacy, 1789-1989, ed. Geoffrey Best (University of Chicago Press, 1989).

William Doyle, The Oxford History of the French Revolution (Oxford University Press, 1990). Ch. 11 "Government by Terror, 1793-1795," pp. 247-71; Ch. 12 "Thermidor, 1794-1795," pp. 272-96.

A Critical Dictionary of the French Revolution, ed. François Furet and Mona Ozouf, trans. Arthur Goldhammer (Harvard University Press, 1989).

- François Furet, "The Terror,", pp. 137-150

- Denis Richet, "Committee of Public Safety," pp. 474-78

3. Primary Sources ("Opposing Voices") in the Reader of Primary Sources or as an Online E-Text

Sources Relevant to the Film:

- Georges Jacques Danton, "On Crisis Measures" (March 10. 1793) in The French Revolution, ed. Paul H. Beik (New York: Macmillan, 1970), pp. 250-55

- Maximilien Robespierre

- "Last Speech to the Convention (July 26, 1794), in Robespierre, ed. George Rudé (New Jersey: Prentice Hall, 1967), pp. 74-78.

- Robespierre's Proposed Declaration of Rights, 24 April, 1793, in A Documentary Survey of the French Revolution, ed. John Hall Stewart (New York: Macmillan, 1964), pp. 430-34

- "On the Principles of Political Morality" (1794) - E-Text

- "The Cult of the Supreme Being" () - E-Text

- "Justification of the Terror" () - E-Text

- "Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen, 27 August 1789" in A Documentary Survey of the French Revolution, ed. John Hall Stewart (New York: Macmillan, 1964), pp. 113-5. E-Text version.

- Documentary Appendices from Daniel Arasse, The Guillotine and the Terror, trans. Christopher Miller (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1991), pp. 184-92.

Other Sources:

- Rouget de Lisle's "La Marseillaise" (1792) - E-text.

4. Film

See the handout on Andrzej Wajda, Danton (1982) 2hrs 16 (LD)

5. Questions to Keep in Mind when Reading and Watching

- Why did the French Revolution turn violent? Was this inevitable?

- How do you account for the contradictory nature of the two major icons of the French Revolution - the Guillotine and the Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen?

- What has been the long-term impact of the French Revolution? on Europe? on us (in Australia)? on the rest of the world?

- "Danton - opponent of bloody revolution and 'friend of the people'? Robespierre - cold-blooded architect of revolutionary dictatorship?" Is this an accurate representation of these two revolutionary figures?

- Assess the historical accuracy of the depiction of Danton and Robespierre in Andrzej Wajda's film Danton (1982).

- What made Wajda's film so controversial in France when it was released?

- How was the bicentennial of the outbreak of the French Revolution "celebrated"?

B. TOPICS FOR WRITTEN WORK

You are required to hand in a Primary Source Exercise, a Film Analysis Exercise and a Major Essay. The major Essay is due at the end of the semester. The first exercise (either on a Primary Source or on a Film) is due in the mid-semester break. The second exercise (either on a Primary Source or on a Film) is due at the relevant Seminar in the second half of the semester. You must choose a different Seminar Topic for each of these pieces of written work, in other words there can be no doubling up of topics.

1. Primary Source Exercise

"Select one of the Primary Sources in the Reader of Primary Sources and answer the following questions: what kind of primary source is it, who wrote (or painted) it, when was it written, why was it written, what does the source tell us about the past?"

In your answer you should

- refer to the questions concerning primary sources posed in the Guide to the Primary Source Exercises - Using Primary Sources (listed below)

- use at least 4 secondary sources listed in the Seminar Reading Guide (in addition to the textbooks by Hamerow or Hobsbawm) for information about the author and the historical context of the primary source

2. Film Analysis Exercise

"Select one of the feature films shown in this Subject and, by using at least one of the primary sources in the Reader of Primary Sources, assess the historical accuracy of the film and account for any discrepancies you find."

In your answer you should

- refer to the issues raised in An Introduction to the Study of Film and History (listed below)

- use at least 1 primary source from the Reader of Primary Sources and 4 secondary sources listed in the Seminar Reading Guide (in addition to the textbooks by Hamerow or Hobsbawm) for information about the events and individuals depicted in the film, the filmmaker, and the historical context in which the film was made

3. Major Essay

- "Danton - opponent of bloody revolution and 'friend of the people'? Robespierre - cold-blooded architect of revolutionary dictatorship?" Use at least two primary sources from the Reader of Primary Sources to assess the accuracy of this assertion about these two revolutionary figures.

C. ADDITIONAL RECOMMENDED READING

Please note: The full bibliography is only available online.

1. On Georges Jacques Danton (1759-1794)

Norman Hampson, Danton (New York: Holmes and Meier, 1978).

Mona Ozouf, "Danton," in A Critical Dictionary of the French Revolution, ed. François Furet and Mona Ozouf, trans. Arthur Goldhammer (Harvard University Press, 1989), pp. 213-222.

2. On Robespierre

Robespierre, ed. George Rudé (New Jersey: Prentice Hall, 1967).

Patrice Gueniffey, "Robespierre" in A Critical Dictionary of the French Revolution, ed. François Furet and Mona Ozouf, trans. Arthur Goldhammer (Harvard University Press, 1989), pp. 298-312.

George Rudé, Robespierre: Portrait of a Revolutionary Democrat (London: Collins, 1975).

3. The Director - Andrzej Wajda

"Andrzej Wajda" in World Film Directors. Volume 2, ed. John Wakeman (New York: H.W. Wilson, 1987), pp. 1148-55.

Mrs. B. Urgolsikova, "Andrzej Wajda" in The International Dictionary of Films and Filmmakers: Volume 2 Directors/Filmmakers, ed. Christopher Lyon (London: Macmillan, 1987), pp. 567-570.

4. Film Reviews

Robert Darnton, "Danton," in Past Imperfect: History according to the Movies, ed. Mark C. Carnes (New York: Henry Holt, 1995), pp. 104-109.

Robert Darnton, "Film: Danton and Double Entendre," The Kiss of Lamourette: Reflections on Cultural History (New York: W.W. Norton, 1990), pp. 37-52.

5. General

An influential non-Marxist (or anti-Marxist) critique is provided by François Furet, Interpreting the French Revolution, trans. Elborg Forster (Cambridge University Press, 1981).

Daniel Arasse, The Guillotine and the Terror, trans. Christopher Miller (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1991).

A Century for Debate, 1789-1914: Problems in the Interpretation of European History, ed. Peter N. Stearns (New York: Dodd, Mead & Co., 1975). Chap.I "The Impact of the French Revolution," pp. 1-30. Essays by Carlyle, Brinton, Lefebvre, Cobban, Rudé.

R.R. Palmer, Twelve Who Ruled: The Year of the Terror in the French Revolution (New York: Atheneum, 1965).

Seminar Topic II. The Rituals & Imagery of Political Power: Republicanism vs Monarchism

|

|

| A Statue of Napoleon overturned by the Communards in 1870 | A Statue of Victoria toppled in the struggle for independence in Georgetown, Guyana, 1966 |

[See the Lecture Notes for this topic.]

A. SEMINAR READING AND DISCUSSION

1. Textbook Reading

Theodore S. Hamerow, The Birth of a New Europe (1983). Hamerow has little to say directly about the power of monarchs and the symbolic representation of that power. Chap. 12 "The Nature of Authority" is a general discussion of the transition from oligarchic forms of government to more popular forms.

Eric Hobsbawm also stresses the emerging new social and political groups which replaced the traditional aristocratic class.

- The Age of Revolution, 1789-1848 (1962): Chap. 1 "The World in the 1780s"; Chap. 3 "The French Revolution"; "The Career Open to Talent"

- The Age of Capital, 1848-1875 (1975): Chap. 1 "'The Springtime of the Peoples'"; Chap. 6 "The Forces of Democracy"; Chap. 13 "The Bourgeois World"

- The Age of Empire, 1875-1914 (1987): Chap. 1 "The Centarian Revolution"; Chap. 4 "The Politics of Democracy"

2. Background Reading - Secondary Sources ("Contested Meaning")

The essays by David Cannadine, "The Context, Performance and Meaning of Ritual: The British Monarchy and the 'Invention of Tradition', c.1820-1977," and Eric Hobsbawm, "Mass-Producing Traditions: Europe, 1870-1914," in The Invention of Tradition, ed. Eric Hobsbawm and Terence Ranger (Cambridge University Press, 1995).

Arno Mayer argues that historians like Hamerow and Hobsbawm have exaggerated the extent of change in political and social power, and that monarchs and traditional aristocratic elites retained considerable power well into the 19thC and even into the 20thC: Arno J. Mayer, The Persistence of the Old Regime: Europe to the Great War (New York: Pantheon, 1981).

3. Primary Sources ("Opposing Voices") in the Reader of Primary Sources

Sources Relevant to the Film:

- Napoleon - paintings by Jacques-Louis David

Images of imperial or royal power:

- Napoleon (see above)

- Queen Victoria

- Painting of The Coronation of Queen Victoria, 1837

- Photograph of Victoria at the Diamond Jubilee, 1897

- George Cruikshank, "The British Beehive" (1840, 1867) (small)

- Emperor Napoleon III

- Kaiser Wilhelm II

Images of republican power and authority:

- Marianne (the Republic, Liberty)

- The First Republic 1792

- The 1830 Revolution

- The Second Republic 1848

- Auguste Bartholdi's "Liberty Enlightening the World" (The Statue of Liberty) (1886)

4. Film

See the handout on Abel Gance, Napoleon (1927) (LD) Part 1 2hrs or Part 2 1hr 51

5. Questions to Keep in Mind when Reading

Concerning the power of monarchs and the depiction of that power in the 19thC:

- What power did 19th century monarchs (kings, queens, emperors) wield and what role did public rituals and ceremonies (e.g. coronations, marriages, jubilees, funerals) play in maintaining that power?

- the coronation of Napoleon Bonaparte as Emperor (1804)

- the cluster of coronations in the 1820s: George IV in Britain (1821); Charles X in France (1824); and Nicholas I in Russia (1825)

- the coronation (1837), marriage and jubilee of Queen Victoria

- 1888 - "the Year of the Three Emperors" (Wilhelm I, Frederick III, Wilhelm II) in the German Empire

- To what extent were the "traditions" of royalty "invented" in the 19thC as argued in the book of essays The Invention of Tradition, ed. Eric Hobsbawm and Terence Ranger (1995)?

- What does political imagery (officially commissioned art or photographs) tell us about how political leaders wished to be seen by the public? (See the list of images below)

The great challenge to monarchical power came from the republican tradition issuing from the American (1776) and French Revolutions (1789, 1848, 1871). This other political tradition also had its imagery and rituals:

- Discuss the imagery and ritual used by "the other tradition" of the 19thC, namely republicanism (French and American), to assert its claims to legitimacy

- see the images listed below

- the public celebration of "revolutionary days" - "July Fourth" (USA) and "14th July" (France), especially the centennial of the American (1876) and French (1889) Revolutions

What did the figure of "Britannia" represent in the 19thC?

An historiographical question arises with the claim by Mayer that the power of the old regime "persisted" well into the late 19thC in spite of the forces of democracy and the industrial revolution:

- Assess Mayer's claim that the old regime resisted or adapted to many of the changes introduced by the French and Industrial Revolutions and thus "persisted" well into the late 19thC

B. TOPICS FOR WRITTEN WORK

You are required to hand in a Primary Source Exercise, a Film Analysis Exercise and a Major Essay. The major Essay is due at the end of the semester. The first exercise (either on a Primary Source or on a Film) is due in the mid-semester break. The second exercise (either on a Primary Source or on a Film) is due at the relevant Seminar in the second half of the semester. You must choose a different Seminar Topic for each of these pieces of written work, in other words there can be no doubling up of topics.

1. Primary Source Exercise

"Select one of the Primary Sources in the Reader of Primary Sources and answer the following questions: what kind of primary source is it, who wrote (or painted) it, when was it written, why was it written, what does the source tell us about the past?"

In your answer you should

- refer to the questions concerning primary sources posed in the Guide to the Primary Source Exercises - Using Primary Sources (listed below)

- use at least 4 secondary sources listed in the Seminar Reading Guide (in addition to the textbooks by Hamerow or Hobsbawm) for information about the author and the historical context of the primary source

2. Film Analysis Exercise

"Select one of the feature films shown in this Subject and, by using at least one of the primary sources in the Reader of Primary Sources, assess the historical accuracy of the film and account for any discrepancies you find."

In your answer you should

- refer to the issues raised in An Introduction to the Study of Film and History (listed below)

- use at least 1 primary source from the Reader of Primary Sources and 4 secondary sources listed in the Seminar Reading Guide (in addition to the textbooks by Hamerow or Hobsbawm) for information about the events and individuals depicted in the film, the filmmaker, and the historical context in which the film was made

3. Major Essay

- Compare and contrast the depiction of power and authority in at least one image of royalty (i.e. a king, queen, or emperor), and at least one image of a republic (i.e. "Liberty" or "Marianne") in the Reader of Primary Sources.

C. ADDITIONAL RECOMMENDED READING

Please note: The full bibliography is only available online.

1. Other Images of Monarchical and Republican Power

Monarchical or Imperial Power:

- Napoleon Bonaparte

- Painting by Gerard of Napoleon in Coronation Robes

- Emperor Napoleon III

- Louis Napoleon Bonaparte

- Louis Napoleon, President of the Republic

- Queen Victoria's visit with Napoleon III to Napoleon's Tomb

- Napoleon I and his nephews and neices on the terrace at Saint-Cloud

- Napoleon III wearing Imperial robes

- Nicholas I (images to come)

- Queen Victoria

- Sir Thomas Brock's "Victoria Memorial" (1910-1924)

- Henry Tamworth Wells, "Victoria Regina: Victoria Receiving the News of her Accession" (1880)

- George Hayter, sketch for "Queen Victoria Taking the Coronation Oath" (1838)

- J. Prentice, "Her Majesty in Military Costume at a Review at Windsor, September 28, 1837' (1837)

- Marriage to Albert 1840

- The Queen typing her correspondence

- Queen Victoria and Prince Albert dressed up to attend a "Plantagenet Ball" at Buckingham Palace, 12 May, 1842. Painitng by Edwin Landseer, 1842

- Photograph of the Royal Family, 1894 with Victoria, the future Edward VII (at left), the future George V (at right), and the future Edward VIII (in Victoria's arms).

- Winterhalter, Queen Victoria and Her Family, 1846

- King Louis Philippe

- Kaiser Wilhelm II

Toppled Monarchs

- A Restored Henry IV (1818)

- Louis XIV (1792)

- Napoleon (1870)

- Wilhelm I (1918)

- Queen Victoria, Georgetown, Guyana, 1966

Republican Power - Marianne (the Republic, Liberty):

- The First Republic 1792

- The Second Republic 1848

- Barre, "The Republic" (1848)

- A Conservative Image of the Republic

- Landelle "The Republic"

- Soitoux, "The Republic" (1848)

- Sorrieu "The Universal Republic" (1848)

- The Third Republic

- Caricatures and Cartoons

- Caricature from 1848 "Changing the Symbols"

- Postcard of "Paris handed over: The Capitulators" (1871)

- Talons, "The Bloody Republic" (1849)

- Land, "Marianne and Germania in the New Unified Europe" (1995)

- Cheryl Kernot as Marinanne leading the Labor Party to the Barricades (1998)

- Marianne at the Sydney Gay and Lesbian Mardi Gras (1998)

- Auguste Bartholdi's "Liberty Enlightening the World" (The Statue of Liberty) (1886)

3. Reading on Monarchs and Emperors

General: "The Invention of Tradition" and the Ritual of Royalty

David Cannadine, "The Context, Performance and Meaning of Ritual: The British Monarchy and the 'Invention of Tradition', c.1820-1977," in The Invention of Tradition, ed. Eric Hobsbawm and Terence Ranger (Cambridge University Press, 1995), pp. 101-64.

Eric Hobsbawm, "Mass-Producing Traditions: Europe, 1870-1914," in The Invention of Tradition, ed. Eric Hobsbawm and Terence Ranger (Cambridge University Press, 1995), pp. 263-307.

For an anthropologist's perspective which is broadranging and stimulating: Clifford Geertz, "Centers, Kings and Charisma: Reflections on the Symbolics of Power," in Rites of Power: Symbolism, Ritual, and Politics Since the Middle Ages, ed. Sean Wilentz (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1985), pp. 13-38.

Simon Schama, "The Domestication of Majesty: Royal Family Portraiture, 1500-1850," Journal of Interdisciplinary History, vol. 17, 1986, pp. 155-83.

The French Monarchy

Richard A. Jackson, Vive le roi! A History of the French Coronation from Charles V to Charles X (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1984). Part Five: The Coronation in History anbd Chap. 12 "After Napoleon, the Denoument".

The French Revolution

Lynn Hunt, Politics, Culture and Class in the French Revolution (University of California Press, 1984). Part I: The Poetics of Power" - Chap. 1"The Rhetoric of Revolution," pp. 19-51; Chap. 2 "Symbolic Forms of Political Practice," pp. 52-86; Chap. 3 "The Imagery of Radicalism," pp. 87-119.

Mona Ozouf, Festivals and the French Revolution (Harvard University Press, 1988).

Napoleon Bonaparte

Albert Boime, Art in an Age of Bonapartism, 1800-1815 (University of Chicago Press, 1990). Chap. 2 "The Iconography of Napoleon," pp. 35-95.

Martyn Lyons, Napoleon Bonaparte and the Legacy of the French Revolution (London: Macmillan, 1994). Chap. 13 "Art, Propaganda and the Cult of Personality," pp. 178-94.

Warren Roberts, Jacques-Louis David, Revolutionary Artist: Art, Politics, and the French Revolution (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1989). Chap. 4 "David and Napoleon," pp. 129-86.

19thC France

Maurice Agulhon, "Politics, Images, and Symbols in Post-Revolutionary France," in Rites of Power: Symbolism, Ritual, and Politics Since the Middle Ages, ed. Sean Wilentz (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1985), pp. 177-205.

Britain

David Cannadine, "The Context, Performance and Meaning of Ritual: The British Monarchy and the 'Invention of Tradition', c.1820-1977," in The Invention of Tradition, ed. Eric Hobsbawm and Terence Ranger (Cambridge University Press, 1995), pp. 101-64.

Crown Pictorial: Art and the English Monarchy, ed. Linda Colley et al. (New Haven, Conn.: 1990).

Linda Colley, "The Apotheosis of George III: Loyalty, Royalty and the British Nation, 1760-1820," Past and Present, vol. 102, February 1984, pp. 94-129.

Remaking Queen Victoria, ed. Margaret Homans and Adrienne Munich (Cambridge University Press, 1997). See the essays by:

- Margaret Homans and Adrienne Munich, "Introduction", pp. 1-10

- Elizabeth Langland, "Nation and nationality: Queen Victoria in the developing narrative of Englishness," pp. 13-32.

- Susan Casteras, "The wise child and her "offspring": somoe changing faces of Queen Victoria," pp. 182-199.

Lytton Strachey, The Illustrated Queen Victoria (1921), ed. Michael Holdroyd (London: Bloomsbury, 1987).

The German States/Second Reich

Elisabeth Fehrenbach "Images of Kaiserdom: German Attitudes to Kaiser Wilhelm II," in Kaiser Wilhelm II: New Interpretations, ed. John C. G. Röhl and Nicolaus Sombart (Cambridge University Press, 1982), pp.269-85.

Michael Balfour, The Kaiser and His Times (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1975). Several interesting photographs.

Russia

Richard S. Wortman, "Moscow and Petersburg: The Problem of Political Center in Tsarist Russia, 1881-1914," in Rites of Power: Symbolism, Ritual, and Politics Since the Middle Ages, ed. Sean Wilentz (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1985), pp. 244-71.

Richard S. Wortman, Scenarios of Power: Myth and Ceremony in Russian Monarchy. Vol. One From Peter the Great to the Death of Nicholas 1 (Princeton University Press, 1995).

Austria

Marie Tanner, The Last Descendant of Aeneas: The Hapsburgs and the Mythic Image of Emperor (New Haven, 1993).

4. Reading on Republican Imagery

France

Maurice Agulhon, Marianne into Battle: Republican Imagery and Symbolism in France, 1789-1880, trans. Janet Lloyd (Cambridge University press, 1981).

USA

Marvin Trachtenberg, The Statue of Liberty (London: Penguin, 1976).

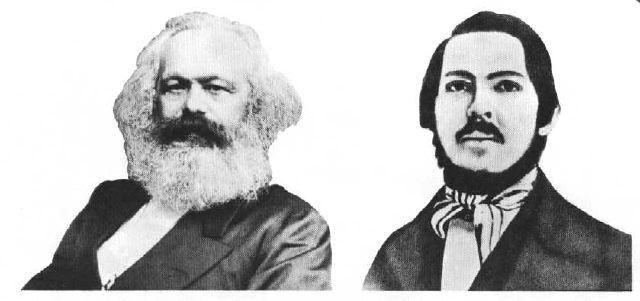

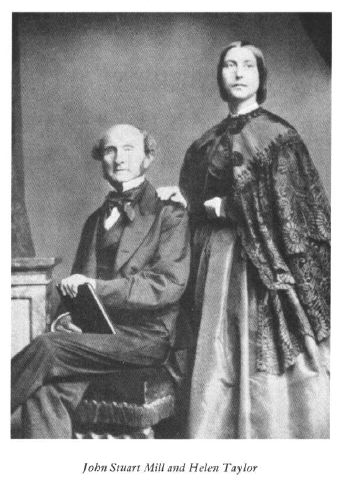

Seminar Topic III. Competing Visions of Freedom & Reform: Mill's Liberalism vs Marx's Socialism

|

||||||

[See the Lecture Notes for this topic. Also this and this.]

A. SEMINAR READING AND DISCUSSION

PLEASE NOTE: SEMINAR DEBATE TOPIC

From the perspective of either the classical liberal John Stuart Mill or the socialist Karl Marx, debate the following question:

- "What is wrong with European society in the mid-19th century and what should or could be done to remedy the situation?"

1. Textbook Reading

Theodore S. Hamerow, The Birth of a New Europe (1983): Chap. 8 The Emergence of the Labor Question"; Chap. 9 "Civic Ideologies and Social Values"

Eric Hobsbawm

- The Age of Revolution, 1789-1848 (1962): Chap. 10 "The Career Open to Talent"; Chap. 11 "The Labouring Poor"; Chap. 13 "Ideology: Secular"

- The Age of Capital, 1848-1875 (1975): Chap. 1 "'The Springtime of the Peoples'"; Chap. 6 "The Forces of Democracy"; Chap. 9 "Changing Society"; Chap. 12 "City, Industry, the Working Class"

- The Age of Empire, 1875-1914 (1987): Chap. 4 "The Politics of Democracy"; Chap. 5 "Workers of the World"; Chap. 12 "Towards Revolution"

2. Background Reading - Secondary Sources ("Contested Meaning")

Himmelfarb's "Introduction," pp. 7-49 to John Stuart Mill, On Liberty (1859), ed. Gertrude Himmelfarb (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1984).

Taylor's "Introduction," pp. 7-47 to Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, The Communist Manifesto (1848), ed. A.J.P. Taylor (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1985).

Eric Hobsbawm's Introduction to the 150th anniversary edition of Karl Marx and Federick Engels, The Communist Manifesto: A Modern Edition (London: Verso, 1998), pp. 1-29.

3. Primary Sources ("Opposing Voices") in the Reader of Primary Sources or as an Online E-Text

- Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, The Communist Manifesto (1848), ed. A.J.P. Taylor (1985) - extracts from pp. 78-83, 95-105. An E-Text version from "The Avalon Project" at Yale University is also available:

- INTRODUCTION

- I. BOURGEOIS AND PROLETARIANS

- II. PROLETARIANS AND COMMUNISTS

- III. SOCIALIST AND COMMUNIST LITERATURE

- IV. POSITION OF THE COMMUNISTS IN RELATION TO THE VARIOUS EXISTING OPPOSITION PARTIES

- John Stuart Mill, On Liberty (1859), ed. Gertrude Himmelfarb (1984) - extracts from pp. 58-63, 68-71, 75-78, 119-23, 130-34, 141-3,156-59, 163-68, 175-77. An E-Text version of On Liberty is also available. The original source is the Project Bartleby Archive at Columbia University. A local copy is:

- Table of Contents

- Bibliographic Record

- Preface

- I. Introductory

- II. Of the Liberty of Thought and Discussion

- III. Of Individuality, as One of the Elements of Well-Being

- IV. Of the Limits to the Authority of Society over the Individual

- V. Applications

- John Stuart Mill, The Subjection of Women (1869) - as an E-Text

- Other E-Text collections

- See also the "Socialism" section of the Internet Modern History Sourcebook at Fordham University.

- Marx/Engels Internet Archive - A massive site containing most of the works of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engles and many other writers in the Marxist traditon.

4. Film

There is no film for this topic.

5. Questions to Keep in Mind when Reading and Watching

Socialism/Marxism

- what criticisms did socialists like Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels have of European society in 1848?

- what are the core beliefs of a socialist like Marx?

- when did "socialism" emerge as a distinctive tradition of political and economic thought?

- how did "socialism" change during the course of the 19thC?

- what do "socialists" believe in the late 20thC?

- what attitudes did socialists have to the following:

- democracy, parliament

- revolution, the French Revolution

- the capitalist system, industrialisation

- government regulation of the economy

- traditional elites (monarchs, princes, nobles)

- new elites (capitalists, factory owners, bourgeoisie)

- the workers, the proletariat

- women

- war, empire

Classical Liberalism

- what criticism of European society did a liberal like John Stuart Mill have of European society in 1859?

- what are the core beliefs of a classical liberal like Mill?

- when did "liberalism" emerge as a distinctive tradition of political and economic thought?

- how did "liberalism" change during the course of the 19thC?

- what do "liberals" believe in the late 20thC?

- what attitudes did classical liberals have to the following:

- democracy, parliament

- revolution, the French Revolution

- the capitalist system, industrialisation

- government regulation of the economy

- traditional elites (monarchs, princes, nobles)

- new elites (capitalists, factory owners, bourgeoisie)

- the workers, the proletariat

- women

- war, empire

B. TOPICS FOR WRITTEN WORK

You are required to hand in a Primary Source Exercise, a Film Analysis Exercise and a Major Essay. The major Essay is due at the end of the semester. The first exercise (either on a Primary Source or on a Film) is due in the mid-semester break. The second exercise (either on a Primary Source or on a Film) is due at the relevant Seminar in the second half of the semester. You must choose a different Seminar Topic for each of these pieces of written work, in other words there can be no doubling up of topics.

1. Primary Source Exercise

"Select one of the Primary Sources in the Reader of Primary Sources and answer the following questions: what kind of primary source is it, who wrote (or painted) it, when was it written, why was it written, what does the source tell us about the past?"

In your answer you should

- refer to the questions concerning primary sources posed in the Guide to the Primary Source Exercises - Using Primary Sources (listed below)

- use at least 4 secondary sources listed in the Seminar Reading Guide (in addition to the textbooks by Hamerow or Hobsbawm) for information about the author and the historical context of the primary source

2. Film Analysis Exercise

"Select one of the feature films shown in this Subject and, by using at least one of the primary sources in the Reader of Primary Sources, assess the historical accuracy of the film and account for any discrepancies you find."

In your answer you should

- refer to the issues raised in An Introduction to the Study of Film and History (listed below)

- use at least 1 primary source from the Reader of Primary Sources and 4 secondary sources listed in the Seminar Reading Guide (in addition to the textbooks by Hamerow or Hobsbawm) for information about the events and individuals depicted in the film, the filmmaker, and the historical context in which the film was made

3. Major Essay

- Compare and contrast the criticisms of mid-19th century European society made by John Stuart Mill and Karl Marx.

C. ADDITIONAL RECOMMENDED READING

Please note: The full bibliography is only available online.

1. "Opposing Voices" (Primary Sources)

John Stuart Mill

John Stuart Mill, On Liberty (1859), ed. Gertrude Himmelfarb (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1984). Himmelfarb's "Introduction," pp. 7-49 and Mill's "Introductory," pp. 59-74.

John Stuart Mill, On Liberty and Other Essays, ed. John Gray (Oxford University Press, 1991). John Gray's introduction pp. vii-xxx and Mill's essay.

Other Classical Liberals

A very useful, comprehensive anthology of classical liberal writers with a lengthy historical introduction: Western Liberalism: A History in Documents from Locke to Croce, ed. E.K. Bramsted and K.J. Melhuish (London: Longamn, 1978).

Herbert Spencer, The Man vs. the State (1884) - E-Text:

- PREFACE

- I. THE NEW TORYISM

- II. THE COMING SLAVERY

- Notes

- III. THE SINS OF LEGISLATORS

- Notes

- IV. THE GREAT POLITICAL SUPERSTITION

- Notes

- V. POSTSCRIPT

Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels

Karl Marx and Friedrich. Engels, The Communist Manifesto (1848), ed. A.J.P. Taylor (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1985). Taylor's "Introduction," pp. 7-47 and the "Manifesto."

Other Socialists and "Marxists"

An anthology of pre-Marxist socialist writers: Before Marx: Socialism and Communism in France, 1830-48, ed. Paul Corcoran (London: Macmillan).

2. "Contested Meaning" (Secondary Sources)

On Mill

Gertrude Himmelfarb, On Liberty and Liberalism: The Case of John Stuart Mill (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1974). Chap. 1 "'One Very Simple Principle'," pp. 3-22.

William Thomas, J.S. Mill (Oxford Past Masters: Oxford University Press, 1985).

John M. Robson, The Improvement of Mankind (University of Toronto Press, 1968).

Alan Ryan, J.S. Mill (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1974).

John Gray, Liberalism (Milton Keynes: Open University Press, 1986).

On Marx

David McLellan, Karl Marx (Fontana Modern Masters).

David McLellan, Karl Marx: His Life and Thought (New York: Harper, 1977).

Shlomo Avinieri, The Social and Political Thought of Karl Marx (Cambridge University Press, 1968).

David McClellan, Karl Marx: His Life and Thought (New York: Harper, 1977).

Alan Gilbert, Marx's Politics: Communists and Citizens (Oxford: Martin Robertson, 1981). Chap. VIII "The Communist Manifesto and Marx's Strategies," pp. 125-35.

John M. Maguire, Marx's Theory of Politics (Cambridge University Press, 1978). Chap 2 "Perspectives on Revolution: Marx's Position on the Eve of 1848," pp. 28-47.

Thomas Sowell, Marxism: Philosophy and Economics (New York: William Morrow and Co., 1985).

On Socialism

George Lichtheim, A Short History of Socialism (London, 1970).

R.N. Berki, Socialism (New York: St. Martin's Press, 1975). Chap. 4 "The Nature of the Marxian Achievement," pp. 56-72.

G.D.H. Cole, A History of Socialist Thought, 5 vols (London: Macmillan, 1953-).

Alexander Gray, The Socialist Tradition: Moses to Lenin (London: Longman's, 1963).

On Classical Liberalism

Anthony Arblaster, The Rise and Decline of Western Liberalism (Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1984).

John Gray, Liberalism (Milton Keynes: Open University Press, 1986).

See the Web Site for my subject "Liberal Europe and Social Change 1815-1914"

See the Web Site of my PhD on early 19thC French liberal thought: CLASS ANALYSIS, SLAVERY AND THE INDUSTRIALIST THEORY OF HISTORY IN FRENCH LIBERAL THOUGHT, 1814-1830: THE RADICAL LIBERALISM OF CHARLES COMTE AND CHARLES DUNOYER (1994).

James J. Sheehan, German Liberalism in the Nineteenth Century (London: Methuen, 1982).

Gordon A. Craig, The Triumph of Liberalism: Zurich in the Golden Age, 1830-1869 (New York: Collier, 1988).

André Jardin, History of Political Liberalism in France from the Crisis of Absolutism to the Constitution of 1875 (1985).

Massimo Salvadori,The Liberal Heresy: Origins and Historical Development (London: Macmillan, 1977).

D.J. Manning, Liberalism (London: J.M. Dent and Sons, 1982).

Ludwig von Mises, Liberalism: A Socio-Economic Exposition, tr. Ralph Raico (Kansas City: Sheed Andrews and McMeel, 1978).

Steven Lukes, Individualism (Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1973).

Guido de Ruggiero, The History of European Liberalism, trans. R.G. Collingwood (Boston: Beacon Press, 1959).

Seminar Topic IV. The Abolition of Serfdom & Slavery

|

[See the Lecture Notes for this topic. And this.]

A. SEMINAR READING AND DISCUSSION

1. Textbook Reading

Theodore S. Hamerow, The Birth of a New Europe (1983). There is very little on the abolition of serfdom and slavery in Hamerow. Chap. 2 "The Transformation of Agriculture" puts serfdom into the broader context of agricultural change.

Eric Hobsbawm: again, very little of the emancipation of serfs and slaves per se, although the theme of "emancipation" pervades the trilogy of texts.

- The Age of Revolution, 1789-1848 (1962). Chap. 1 "The World in the 1780s" and Chap. 8 "Land" deals with serfdom in general.

- The Age of Capital, 1848-1875 (1975). Chap. 10 "The Land" treats serfdom briefly.

- The Age of Empire, 1875-1914 (1987). Very little on serfdom or slavery as it had been by and large abolished by the late 19thC.

2. Background Reading - Secondary Sources ("Contested Meaning")

The most comprehensive and detailed account of the ending of serfdom in Europe over the period 1771 (Savoy) to 1864 (Roumania): Jerome Blum, The End of the Old Order in Rural Europe (Princeton University Press, 1978). Part One describes the traditional life of peasants and serfs. Part Two deals with the early efforts at reform from above - see Chap. 14 "The Old Order Attacked and Defended" for summaries of the main arguments used in the debate; and Chap. 15 "Peasant Unrest" on the pressure from below. Part Three deals extensively with Emancipation.

An excellent comparative account which examines slavery and abolition in the British, American, French, and Spanish colonies and metropoles: Robin Blackburn, The Overthrow of Colonial Slavery 1776-1848 (London: Verso, 1988). See the early chapters for the impact of the American and French Revolutions on slavery and abolitionism. Chap. XI "The Struggle for British Slave Emancipation: 1823-38" and Chap. XII "French Restoration Slavery and 1848" are the most relevant to our needs.

Albert Boime, "The Revulsion to Cruelty," The Art of Exclusion: Representing Blacks in the Nineteenth Century (London: Thames and Hudson, 1990), pp. 47-78.

3. Primary Sources ("Opposing Voices") in the Reader of Primary Sources or as an Online E-Text

Sources Relevant to the Film:

- A web archive of primary sources related to the Amistade case - http://amistad.mysticseaport.org/library/court/welcome.html

- Extracts from The Amistad Case: The Most Celebrated Slave Mutiny of the Nineteenth Century. Two Volumes in One. (New York: Johnson Reprint Corp., 1968).

- Africans Taken in the Amistad (U.S. 26th Congress, 1st Session, H. Exec. Doc. 185) (New York, 1840).

- Argument of John Quincy Adams before the Supreme Court of the United States, in the case of the U.S., appellants, vs. Cinque, and other Africans, captured in the schooner Amistad (New York, 1841).

- TITLE PAGE

- PART I

- PART II

- PART III

- PART IV

- PART V

- Selected Primary Sources on the Amistad Case

- Images

- Plans and cutaways (one and two) of the slave-ship "The Brookes" published by The Society for Christian Morals (1822) in La traite des noirs au siècle des lumières (Témoinages de négriers), ed. Jean-Louis Vissiere (Paris: Métailié, 1982), pp. 40-41.

- Woodruff's 1939 mural celebratiing the 100th anniversary of the Amistad case: Mutiny - Trial - Return

Other Sources:

- Politics and the Public Conscience: Slave Emancipation and the Abolitionist Movement in Britain, ed. Edith F. Hurwitz (1973) -

- "From William Wilberforce, An Appeal to the Religion, Justice and Humanity of the Inhabitiants of the British Empire on Behalf of the Negro Slaves in the West Indies (London, 1823)" pp. 101-12

- "From the Speech of Edward Stanley, Secretary of State for the Colonies, Introducing the Government Plan for the Emancipation of the Slaves, 14 May 1833" pp. 145-55

- "From Petition of Lords Wellington, St Vincent, Penshurst, and Wynford against the Emancipation Act, 20 August, 1833" pp. 156-7.

- Legislation emancipating serfs fromDocuments of European Economic History, ed. S. Pollard and C. Holmes (1968). Vol. One:

- "Abolition of Serfdom in France" (1789) pp. 189-91. E-Text version.

- "Peasant Emancipation in Prussia: Law of 1807" pp. 214-5

- "Abolition of Serfdom in Austria, 1848" pp. 222-3

- Russia - "The Statutes of Emancipation, 1861" pp. 233-38

- Images

4. Film

See the handout on Steven Spielberg, Amistad (1997) 2hrs 35.

5. Questions to Keep in Mind when Reading and Watching

- Discuss the contribution, if any, of the following factors which historians believe contributed to the abolition of slavery (and other forms of compulsory labour such as serfdom in Eastern Europe and convictism in the Australian colonies):

- Christianity

- enlightened and/or liberal humanitarianism

- the rise of Capitalism

- the economic interests of particular classes, especially reform-minded landowners and state bureaucrats

- international pressure

- the political campaigning by women

- the agitation of slaves (serfs, convicts) for change

- Revolution (American, French, 1848)

- what arguments were used to justify serfdom, slavery, and other forms of compulsory labour (e.g. convictism)?

- what arguments were used by refomers and/or abolitionists to oppose serfdom, slavery, and other forms of compulsory labour?

- what impact, if any, did the debate about slavery have on the use of convicts in Australia?

B. TOPICS FOR WRITTEN WORK

You are required to hand in a Primary Source Exercise, a Film Analysis Exercise and a Major Essay. The major Essay is due at the end of the semester. The first exercise (either on a Primary Source or on a Film) is due in the mid-semester break. The second exercise (either on a Primary Source or on a Film) is due at the relevant Seminar in the second half of the semester. You must choose a different Seminar Topic for each of these pieces of written work, in other words there can be no doubling up of topics.

1. Primary Source Exercise

"Select one of the Primary Sources in the Reader of Primary Sources and answer the following questions: what kind of primary source is it, who wrote (or painted) it, when was it written, why was it written, what does the source tell us about the past?"

In your answer you should

- refer to the questions concerning primary sources posed in the Guide to the Primary Source Exercises - Using Primary Sources (listed below)

- use at least 4 secondary sources listed in the Seminar Reading Guide (in addition to the textbooks by Hamerow or Hobsbawm) for information about the author and the historical context of the primary source

2. Film Analysis Exercise

"Select one of the feature films shown in this Subject and, by using at least one of the primary sources in the Reader of Primary Sources, assess the historical accuracy of the film and account for any discrepancies you find."

In your answer you should

- refer to the issues raised in An Introduction to the Study of Film and History (listed below)

- use at least 1 primary source from the Reader of Primary Sources and 4 secondary sources listed in the Seminar Reading Guide (in addition to the textbooks by Hamerow or Hobsbawm) for information about the events and individuals depicted in the film, the filmmaker, and the historical context in which the film was made

3. Major Essay

- Assess the importance of at least two factors which led to the abolition of either slavery or serfdom in the 19thC.

C. ADDITIONAL RECOMMENDED READING

Please note: The full bibliography is only available online.

1. "Opposing Voices" (Primary Sources)

Alexis de Tocqueville, "Report on Abolition" (1839) in Tocqueville and Beaumont on Social Reform, ed. Seymour Drescher (1968), extracts from pp. 98-105, 111-117, 128-32, 135-36.

Images

- William Blake, "A Negro Hung Alive by the Ribs to a Gallows" (1796) - small black and white

- large colour version and small colour version

Extracts from contemporary travellers' accounts of peasant life and emancipation documents. Documents of European Economic History, ed. S. Pollard and C. Holmes (London: Edward Arnold, 1968). Vol. One - "The Process of Industrialization 1750-1870":

- Chap. 1 "Agriculture": docs. on serfdom, peasantry, and land tenure

- Chap. 6 "The Revolutionary Legislation and the Agrarian Settlement in France": "The Abolition of Serfdom in France" and docs. on land tenure

- Chap. 7 "Peasant Emancipation in Germany and the Austrian Empire"

- Chap 8 "Peasant Emancipation in Russia"

Defenders of Serfdom/Slavery

Contains a good chapter on European racism as a justification for black slavery: William B. Cohen, The French Encounter with Africans: White Response to Blacks, 1530-1880 (Indiana University Press, 1980). Chap. 7 "The Nineteenth Century Confronts Slavery, pp. 181-209 and Chap. 8 "Scientific Racism," pp. 210-62.

Reformers and Abolitionists

Politics and the Public Conscience: Slave Emancipation and the Abolitionist Movement in Britain, ed. Edith F. Hurwitz (London: George Allen and Unwin, 1973).

Alexis de Tocqueville, "Part 3: Abolition of Slavery," (1839, 1843) in Tocqueville and Beaumont on Social Reform, ed. Seymour Drescher (New York: Harper and Row, 1968), pp. 98-173.

2. "Contested Meaning" (Secondary Sources)

David Brion Davis, The Problem of Slavery in the Age of Revolution, 1770-1823 (Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press, 1975)

The Amistad Case

Additional bibliography on the Amistad case.

Bertram Wyatt-Brown, Review of Amistad in The Journal of American History, December 1998, pp. 1174-76.

Nobles and Landowners

Dominic Lieven, The Aristocracy in Europe, 1815-1914 (New York : Columbia University Press, 1993).

Terrence Emmons, The Russian Landed Gentry and the Peasant Emancipation (Cambridge University Press, 1968).

Peasants

Annie Moulin, Peasantry and Society in France since 1789, trans. M.C. and M.F. Cleary (Cambridge University Press, 1988).