“BASTIAT'S RHETORIC OF LIBERTY:

THE USE OF LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE IN HIS ECONOMIC WRITINGS”

By David M. Hart

[Created: 15 July, 2023]

[Revised: 30 March, 2025] |

Editor's Note

This paper is an expansion and reworking of three papers I have written on Bastiat "rhetoric of liberty" and is use of literature in his major writings on economics, namely the Economic Sophisms and Economic Harmonies:

- a paper originally written for the History of Economic Thought Society of Australia (HETSA) annual meeting, RMIT Melbourne, Victoria (July, 2011): "Opposing Economic Fallacies, Legal Plunder, and the State: Frédéric Bastiat’s Rhetoric of Liberty in the Economic Sophisms (1846-1850)" [Online]

- two papers originally written for the Association of Private Enterprise Education

International Conference (April, 2015), Cancún, Mexico- "Literature IN Economics, and Economics AS Literature I: Bastiat’s use of Literature in the defense of Free Markets and his Rhetoric of Economic Liberty" (2015) [Online].

- "Literature in Economics, and Economics as Literature II: The Economics of Robinson Crusoe from Defoe to Rothbard by way of Bastiat" (2015) [Online].

Abstract

This paper examines the unique style of writing about economic matters which Frédéric Bastiat (1801-1850) developed in the period between 1845 and 1850 in his writings opposing the policies of protectionism and subsidies to industry by the French government - his "rhetoric of liberty" - and his use of literature in both his journalism (the Economic Sophisms) and his theoretical treatise on economics Economic Harmonies.

I begin by examining the origin, content, and form of Bastiat's Economic Sophisms (1846, 1848). It is argued that in opposing the economic "sophisms" which he saw around him Bastiat developed a unique "rhetoric of liberty" in order to make his case for economic liberty. For the idea of debunking "fallacies", he drew upon the work of Jeremy Bentham on "political fallacies" and Col. Perronet Thomas on "corn law fallacies"; for his use of informal "conversations" to appeal to less well-informed readers, he drew upon the work of two women popularizers of economic ideas, Jane Marcet and Harriet Martineau.

Another original contribution is Bastiat's clever use of short and witty economic "fables" and fictional letters written to political leaders. In many of these apparently "simple" fables Bastiat's draws upon classical French literature (Molière and La Fontaine) as well as contemporary political songs and poems (written by "goguettiers" like his contemporary Béranger) to make serious economic arguments in a very witty and unique manner. Bastiat's self-declared purpose was to make the study of economics less "dry and dull" and to use "the sting of ridicule" to expose the widespread misunderstanding of economic ideas. The result is what Friedrich Hayek correctly described as an economic "publicist of genius".

Particularly noteworthy in his "economic story telling" was his use of the folk character Jacques Bonhomme, or the French everyman, who became an important character in many of his stories where he defended economic liberty as only a wiley French peasant or artisan could do, and who then became Bastiat’s virtual alter ego during the most violent and revolutionary phase of the 1848 Revolution.

One of Bastiat's original contributions to economic theory was the use of Robinson Crusoe from Defoe’s novel to invent an entirely new way of doing economics - “Crusoe economics” - which was a major innovation in the way economists think about how individuals like Robinson Crusoe go about ordering his economic priorities and deciding what his opportunity costs are in making economic decisions about scarce resources. This approach later became the foundation of “praxeology” in the Austrian school of economic theory.

In both of these areas, his new ways of popularizing economics and his invention of “Crusoe economics”, Bastiat has shown us how we might use "literature in economics" and do “economics as literature.”

Table of Contents

- Introduction: Bastiat on Economics and Literature

- Journalism and the Beginning of the "Sophisms"

- The Format of the Economic Sophisms

- The Purpose of the Economic Sophisms

- Other "Sophisms" written and unwritten

- The Intellectual Origins of Bastiat's Attack on Economic "Sophisms" and "Fallacies"

- Bastiat's Rhetoric of Liberty

- Bastiat's use of Literature to illustrate Economic Arguments

- Bastiat's Language of Economic Analysis: From Popular Sayings to Technical Terminology

- Bastiat's Invention of his own Economic Stories I

- Bastiat's' Invention of his Own Economic Stories II: "Crusoe Economics"

- The Use of Stories in Economic Harmonies

- Conclusion

- Appendix 1: A List of the Sophisms by Type of Sophism/Fallacy being Opposed

- Appendix 2: A List of the Sophisms by Format

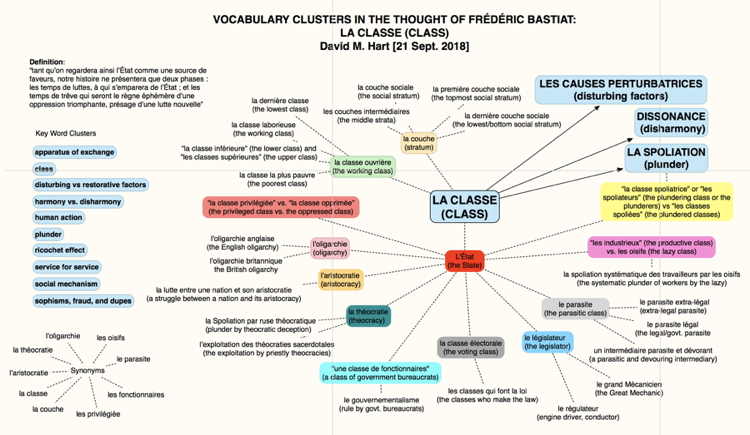

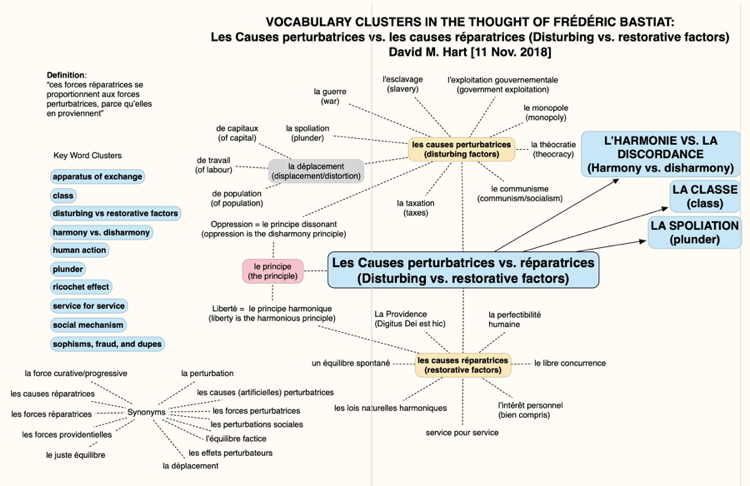

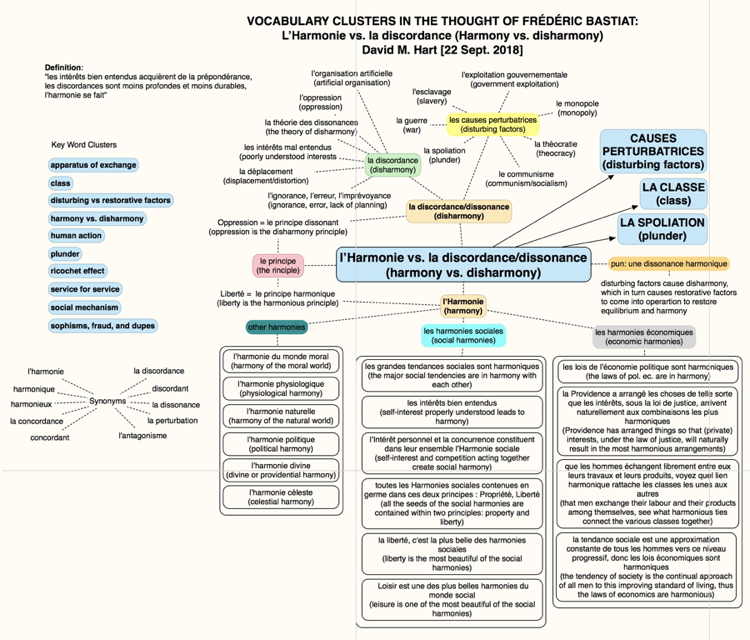

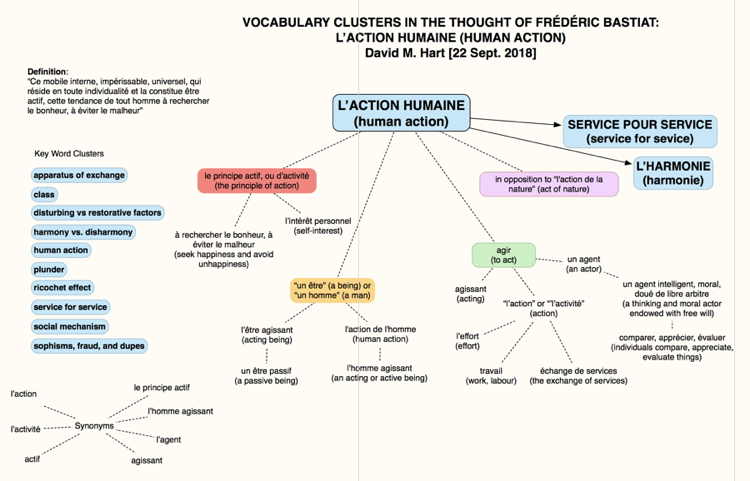

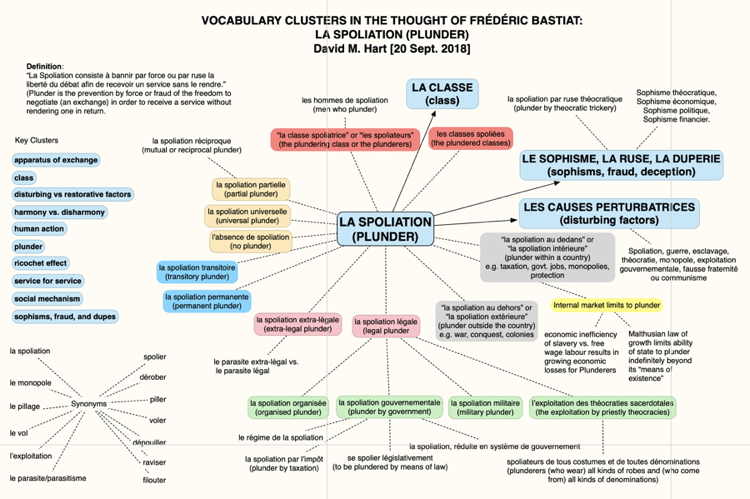

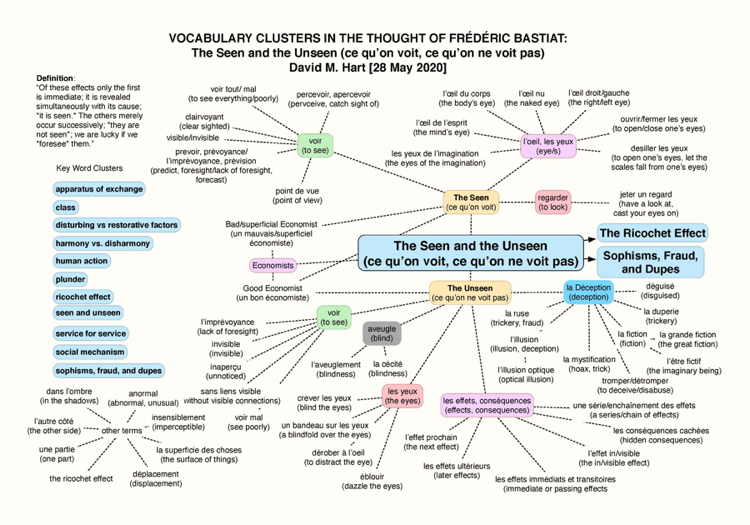

- Appendix 3: Vocabulary Clusters in the Thought of Frédéric Bastiat

- Endnotes

- Bibliography

Introduction: Bastiat on Economics and Literature

The work of the mid-19th century French economic journalist and theorist Frédéric Bastiat (1801-1850) [1] provides an important case study of the sometimes close relationship between economics and literature. [2] In his case it is particularly strong as he was well "versed" in the classics of French literature, such as the fable writer Jean de La Fontaine (1621-1695), the playwright “Molière” or Jean-Baptiste Poquelin (1622- 1673), and the playwright Pierre-Augustin, baron de Beaumarchais (1732-99); as well as more popular writers, such as the poet Évariste Désiré de Forges, comte de Parny (1753-1814), the poet and playwright François Andrieux (1759-1833), the poet and political song writer Pierre-Jean de Béranger (1780-1857), the playwright and fabulist Jean-Pierre Claris de Florian (1755-1794), the novelist and satirist Louis Reybaud (1798-1879), and the radical republican playwright Étienne Vincent Arago (1802-1892). [3] Bastiat also mixed in liberal circles in the late 1840s in which such notable authors as the poet and liberal statesman Alphonse Marie Louis de Lamartine (1790–1869) and the poet and playwright Victor Hugo (1802-1885) also moved.

Bastiat was also familiar with many English authors (he spoke and read four languages - Italian, Spanish, English, French, and also some Basque) whom he also quoted or borrowed from in his own writings. These English authors included Daniel Dafoe (most notably the novel Robinson Crusoe), the “free-trade rhymer” Ebenezer Elliot (1781-1849) [4] who wrote awful poetry for the Anti-Corn Law League, and two women popularisers of free market ideas who wrote little stories or tales for a popular audience, Jane Haldimand Marcet (1769-1858) [5] and Harriet Martineau (1802-1876). [6]

Finally, we should also note that Bastiat referred to Cervantes' Don Quixote (1615) on at least two occasions and devoted an entire story, "Barataria", (unpublished but written possibly in 1848) based upon a disagreement Don Quixote and Sancho had about how to rule an island. In some ways Bastiat might have thought of himself rather sardonically as the economist equivalent of Don Quixote mounting his free market steed to enter into battle once again to fight for the principles that "when something is scare, its price rises; prices rise when and because things are scarce". With similar success as Quixote had one might add. [7]

Bastiat's use of literature was twofold. He regularly quotes from French and English literature (both "popular" and "elite") in order to illustrate his economic points (which I will describe at greater length below) but he also goes one step further which makes him stand out among economists - he adopts several literary forms in order to write about economics. These forms include dialogues and mini-plays, fables, fake petitions, satirical poems, and even short utopian stories. He even goes so far at one point as to adopt the persona of one his fictional characters, the French everyman Jacques Bonhomme, so he can speak directly to the people of Paris as one of them during the 1848 Revolution.

I think Bastiat's use of literature in these ways make him unique in the history of economic thought. It helped him become one of, perhaps even, the greatest economic journalist and populariser who has ever lived, [8] by providing him with the trappings to make his journalism clever, funny, appealing, and understandable to a non-expert audience, namely by his use of the apt quote, a clever reference to a literary figure, or the amusing pun. It also led him, perhaps unintentionally, to a new "literary" way of doing economics, by not just quoting the work of others but by writing his own poems and plays in which he would couch his economic arguments, and by inventing his own "economic fables" and stories, most notably stories about the French everyman Jacques Bonhomme and Robinson Crusoe.

One of his most significant innovations was to use literature to create an entirely new way of thinking about economics, what we know today as "praxeology" or the science of human action which is central to the Austrian school of economic thought. Bastiat began by taking the characters Robinson Crusoe and Friday ("Vendredi") from Defoe's novel in order to illustrate some of the principles of free trade and protection in several short dialogues in his Economic Sophisms and then later extending this into a much more abstract theory about how individuals make economic decisions in his unfinished treatise Economic Harmonies (1850, 1851). Bastiat thus is the inventor of what one might call "praxeological Crusoe economics" which was later taken up by Austrian economists like Böhm-Bawerk in the 1880s and Murray N. Rothbard in the 1960s and 1970s and incorporated into the theoretical foundations of Austrian economics at a very deep level, as well as Rothbard's theory of property rights and anarcho-capitalism. This achievement thus makes Bastiat an important forebear of the Austrian School of economic thought and modern libertarian political theory.

Journalism and the Beginning of the "Sophisms"↩

Bastiat's arrival in Paris and the Birth of the "Sophisms"

Frédéric Bastiat [9] burst onto the Parisian political economy scene in October 1844 with the publication of his first major article "De l'influence des tarifs français et anglais sur l'avenir des deux peuples" (On the Influence of English and French Tariffs on the Future of the Two People) in the Journal des Économistes. [10] This proved to be a sensation and he was welcomed with open arms by the Parisian political economists [11] as one of their own. It turned out that this essay by an unknown author from the distant province of Les Landes sat in the editor's inbox for some time as it was not deemed worthy of his attention. When he finally got around to reading it the word got around and things changed dramatically for the author. He soon became one their regular and most popular authors. He was invited to visit them in Paris and then England in order to meet Richard Cobden and other leaders of the Anti-Corn Law League. Bastiat's book on Cobden and the League appeared in 1845 which was an attempt to explain to the French people the meaning and significance of the Anti-Corn Law League by means of Bastiat's lengthy introduction and his translation of key speeches and newspaper articles by members of the League. [12] It was in this very welcoming context that Bastiat began his career as an economic journalist. He was encouraged by the leaders of "la Société d'Économie Politique" (the Political Economy Society) [13] to write a series of articles explicitly called "Economic Sophisms" for the April, July, and October 1845 issues of their Journal des Économistes. [14] These became the first half of a larger collection of 22 pieces which would appear in early 1846 as Economic Sophisms. [15] As articles continued to pour from the pen of Bastiat during 1846 and 1847, most of which were first published in his own free trade journal Le Libre-Échange (founded 29 November 1846 and closed 16 April 1848) [16] and in the Journal des Économistes, he soon amassed enough material to publish a second volume of the Economic Sophisms in January 1848 which consisted of 17 essays. [17] As Bastiat's literary executor, friend, and editor of his complete works Prosper Paillottet noted in a footnote, there was even enough material for a third series compiled from the other short pieces which appeared between 1846 and 1848 in various organs such as Le Libre-Échange, had Bastiat lived long enough to get them ready for publication. [18] With Liberty Fund's edition of volume three of Bastiat's Collected Works (2017) we were able to do what he and Paillottet were not able to do, namely gather in one volume most of Bastiat's other Sophisms. The selection criteria is that they were written in a similar style, namely short, witty, sarcastic, pieces sometimes in dialogue form, and having the intention of debunking widely held but false economic ideas. The "Economic Sophisms. Series III" which we compiled consisted of 24 essays. We also included in the volume the pamphlet Ce qu'on voit et ce qu'on ne voit pas (What is Seen and What is Not Seen) (July 1850) [19] with its 12 chapters which is also very much in the same style and format as the "Economic Sophisms".

To this collection of the "sophisms" I have added four more "economic sophisms" and five "political sophisms" for a combined total of 87 essays.

Bastiat the Economic Journalist

It should be noted Bastiat has been recognized as an outstanding economic journalist by writers such as Joseph Schumpeter (1954) and Friedrich Hayek (1964), but who in turn dismissed his abilities as an economic theorist. His most damning critic was Schumpeter in his History of Economic Analysis (1954) who mocked his efforts as an economic theorist ("he was no theorist") but grudgingly admits that he "might" go down in history as "the most brilliant economic journalist who ever lived". [20] Hayek's assessment was damning in another way. In his rather "Austro-English" very polite manner he suggested it would be better for the reader not to look too closely into the matter but turn his gaze away. We might still read his journalism but "we might well leave it at that". [21]

I believe both Schumpeter and Hayek are wrong about Bastiat's merits as an economic theorist but that is another matter discussed elsewhere. [22]

To return to Bastiat the economic journalist , it is instructive to examine the variety of formats in which he published his material and the organs in which they were published. He did not stick to any hard or fast approach to his writing. Sometimes he would write just an ephemeral article on a local issue which had no further use or purpose. At other times he would write an article for a small journal or newspaper, and then adapt it for publication as a stand alone pamphlet, or in a more "high brow" journal, or inclusion in a printed collection such as Economic Sophisms I (1846) and Economic Sophisms II (1848). Each article therefore needs to be understood in the light of the original place of publication and the audience for whom it was written. We have indicated wherever possible in a footnote this contextual information in order to help the reader.

A good example of this flexibility is his famous essay on "L'État" (The State) which he originally wrote as a very short article in his street magazine Jacques Bonhomme aimed at ordinary workers and protesters in the streets of Paris in June 1848. He then expanded it for publication in the more intellectual Journal des Débats in September 1848, and then again as a pamphlet in 1849 as part of the election campaign against the socialists. [23]

The following are the different types of articles he wrote and the organs in which they appeared in print:

- articles in newspapers and journals aimed at a popular audience, e.g. Le Libre-Échange which was the organ of the French Free Trade Association)

- articles in highbrow magazines aimed at an educated audience, e.g. the Journal des Débats

- articles in academic journals aimed at a specialized readership, e.g. the Journal des Économistes published by Guillaumin

- articles written for revolutionary newspapers to be handed out on the streets of Paris during the Revolution of February and March 1848 and June 1848, e.g. the short lived newspapers La République française and Jacques Bonhomme respectively

- some very short articles were written expressly to be used as wall posters (affiches) which were stuck up on the streets of Paris during the Revolution. Some of the articles in Jacques Bonhomme fall into this category. [24]

- many of his longer essays and Sophisms were reprinted as stand alone pamphlets by the Guillaumin publishing firm after they first appeared in the journals and then sold to the public.

Bastiat's First Use of the term "Sophisms"?

The first time an essay was published which was explicitly called a "sophism" was in April 1845 in the Journal des Économistes when Bastiat began the series of essays which would eventually become the first book of Economic Sophisms. [25] But this was not the first time Bastiat had used the term.

As early as November 1830 when he ran for election for the first time [26] he used the term in his election platform to criticise so-called "moderates" who wanted to increase taxes. He thought their call for "moderation" was just part of "cette armée de sophismes" (this army of sophismes) which were being presented to the voters in order to deceive and "blind" (s’aveugler soi-même) them. [27] The latter statement is also interesting as an early example of his very important notion of "the seen and the unseen" and all the other variants of language he used to describe "perceiving" and "deceiving," "seeing" and "not seeing", the "physical eye" and "the mind's eye", etc. [28]

It was not until thirteen years later that he used the term again. In a paper on the wine industry he presented to "La Société d’agriculture, commerce, arts, et sciences du département des Landes" (January 1843) [29] he talks about the credulity of the public in believing "sophisms" about why the industry is suffering. The tax authorities blamed the farmers for planting too many vines (the sophism). Bastiat believes it is because of the deleterious impact of high taxes and market restrictions on wine production (the truth). [30] Then again in May in an article he wrote for a local newspaper La Sentinelle des Pyrénées on how vested interests pay newspapers to defend legislation which benefits them at the expense of others. The newspapers say they are just "earning a living" by doing so. Bastiat believes they are corrupt and their justifications are only "sophisms" which "saute(ent) aux yeux" (leap out before one's eyes). [31]

After Bastiat entered the circle of the Paris-based political economists and began writing regularly for the JDE his use of the term "sophism" was much more frequent and it became a staple of his writing. In the first article he wrote for the JDE, "De l’influence des tarifs français et anglais sur l’avenir des deux peuples" (October 1844) he uses it only once when describing the true nature of the protectionists. He thought it was the task of the economist to expose them by stripping away "des prétextes, des sophismes, des faux exposés" (the excuses, sophisms, and false accounts) which they used to "disguise" their true aims in a way that was "toute franche et toute nue" (completely frank and naked). [32]

Bastiat became angrier and began to use much more "harsh" language about sophisms in his long Introduction to his book on Cobden and the League (July 1845), in which there were six references. [33] In one reference he returns to the idea that the protectionists could draw upon a well established "l’armée de sophismes qui, dans tous les temps et dans tous les pays, ont servi d’étai au monopole" (the army of sophisms which have served as the supporting struts of monopoly at all times and in all countries). Some of his strongest language appears in a passage in which he expresses his admiration for the courage and integrity of the members of the Anti-Corn Law League in opposing what he called "le régime le plus oppressif et le plus fortement organisé, après l’esclavage" (the most oppressive and strongly organised regime since slavery). I quote the full passage to show its power: [34]

C’est certainement un grand et beau spectacle que de voir un petit nombre d’hommes essayant, à force de travaux, de persévérance et d’énergie, de détruire le régime le plus oppressif et le plus fortement organisé, après l’esclavage, qui ait pesé jamais sur un grand peuple et sur l’humanité, et cela sans en appeler à la force brutale, sans même essayer de déchaîner l’animadversion publique, mais en éclairant d’une vive lumière tous les replis de ce système, en réfutant tous les sophismes sur lesquels il s’appuie, en inculquant aux masses les connaissances et les vertus qui seules peuvent les affranchir du joug qui les écrase. |

It is certainly a grand and beautiful spectacle to see a small number of men attempting, through their hard work, perservereance, and energy, to destroy the most oppressive and strongly organised regime which, after slavery, has ever weighed down upon a great people and on humanity. And they do thus without calling upon brute force or even in unleashing public anger, but by shining a bright light on all the ins and outs of this system, by refuting all the sophisms on which it is supported, in instilling in the masses the knowledge and the moral virtues which alone can free them from the yoke which crushes them. |

On the other hand, his mocking style is also revealed in a critique of a pro-protectionist journal La Presse which he wrote for the JDE in December 1845, "La Ligue anglaise et la Ligue allemande" (The English League and the German League). [35] It is noteworthy for his use of the metaphor of the "tied up hand" which he would use to such good effect in a later sophism "La main droite et la main gauche" (The Right Hand and the Left Hand). [36] In his critique of La Presse he says: [37]

L’argumentation de la Presse n’est donc qu’un sophisme de confusion. L’Allemagne avait ses deux bras garrottés ; le Zollverein est survenu qui a dégagé le bras droit (commerce intérieur) et gêné un peu plus le bras gauche (commerce extérieur) ; dans ce nouvel état elle a fait quelque progrès. « Voyez, dit la Presse, ce que c’est pourtant que de gêner le bras gauche ! » Et que ne nous montre-t-elle le bras droit ? |

The argument used by La Presse is a sophism of confusion. Germany had its two hands tied (garrottés). When the Zollverein arose the right hand (internal trade) was untied while the left hand (foreign trade) was restricted a bit more. In this state of affairs it has made some progress. "Look, says La Presse, this happened in spite of of restricting its left hand!" And what about showing us what the right hand is doing? |

With these five early uses of the term "sophism" under his belt Bastiat would go on to write scores of what he called "sophisms", or short essays is which he would mock, denounce, and rebut the common falsehoods and deceptive arguments used by the protectionists and the supporters of government intervention in the economy. What follows is a discussion of the formats he used in writing these essays, a more detailed examination of his aims in writing them, and the historical precedents from which he drew inspiration.

The Format of the Economic Sophisms↩

Introduction

A fuller list of the rhetorical devices used by Bastiat in the collected Sophisms shows the breadth and complexity of what one might call his “rhetoric of liberty” which he formulated to expose the follies of the policies of the ruling elite and their system of “la spoliation légale" (legal plunder), and to undermine their authority and legitimacy with "la piqûre du ridicule" (the sting of ridicule):

- a standard prose format which one would normally encounter in a newspaper or magazine

- the single authorial voice in the form of a personal conversation with the reader, often using the familiar "tu" form.

- a serious constructed dialogue between stock figures who represented different viewpoints, usually a protectionist and a free trader (in this Bastiat was influenced by Jane Marcet and Harriet Martineau; Gustave de Molinari continued Bastiat’s format in some of his writings in the late 1840s and 1850s)

- satirical "official" letters or petitions to government officials or ministers, and other fabricated documents written by Bastiat (in these Bastiat would usually use a reductio ad absurdum argument to mock his opponents" arguments)

- the use of Robinson Crusoe stories or "thought experiments" to make serious economic points or arguments in a more easily understandable format

- "economic tales" modelled on classic French authors such as La Fontaine's fables, and Andrieux's short stories

- parodies of well-known scenes from French literature, such as Molière's plays in which Bastiat would change the words in order to make contemporary political and economic points

- quoting scenes of plays were the playwright mocks the pretensions of aspiring bourgeois who want to act like the nobles who disdain commerce (e.g., Molière, Beaumarchais)

- quoting poems with political content, e.g. Horace's Ode on the transience of tyrants

- quoting satirical songs about the foolish or criminal behaviour of kings or emperors (such as Napoleon) (Bastiat was familiar with the world of the "goguettiers" (political song writers) and their interesting sociological world of drinking and singing clubs

- the use of jokes, plays on words, and puns (such as the names gave to characters in his dialogs (Mr. Blockhead), or place names ("Stulta" and "Puera"), and puns on words such as "Highville", and "gaucherie")

We have identified a total of 87 individual sophisms which Bastiat wrote between 1845 and 1850. There were 22 plus an Introduction and Conclusion in ES1 (published in January 1846); 17 in ES2 (published in January 1848); 28 in our edition of ES3 (published in journals like Le Libre-Échange, La République française, Jacques Bonhomme, or unpublished papers found by his literary executors after his death); the 12 chapters of WSWNS plus an Introduction (published in July 1850); and five "political sophisms" written at various times.

In writing these essays Bastiat used a variety of formats which are listed below according to how frequently they occur in the collection. See Appendix 2 for a List of the Sophisms by Format.

- essays written in informal or more conversational prose (40 essays or 46%) - (IP)

- essays which were in dialog or constructed conversational form (14 or 16%) - (D)

- essays written in more formal or academic prose (12 or 14%) - (FP)

- stand alone economic tales or fables (10 or 11.5%) - (EF)

- fictional letters or petitions to government officials and other documents (8 or 9.2%) - (P)

- direct appeals to the workers and citizens of France (4 or 4.6%) - (A)

i. Essays written in Informal or more Conversational Prose (IP)

These essays are the dominant type in the collection (40) and make up 46% of the total. Not surprisingly they read like they were originally written for popular newspapers and are quite conversational in tone. Bastiat often quotes from the speeches or writings of his protectionist opponents before attempting to refute their arguments. He also often makes conversational asides to his readers (e.g. the exclamation "Que!" (What!) or other comments) which gives the impression that Bastiat is sitting next to the reader in a bar or public debate and having a vigorous conversation. It is quite possible that the style of these essays is a result of a version of them having been given as speeches in public meetings of the French Free Trade Association before being printed in the Association's journal Le Libre-Échange. Some of these essays contain stories about made up characters with snippets of their dialog as Bastiat goes about making his points; others contain brief references to one of Bastiat's favourite characters, Jacque Bonhomme, the French everyman. Because the dialog or conversation is only a small part of the essay they have been included in this category and not the next. [38]

ii. Essays written in Dialog or Constructed Conversational Form (D)

The second most common format for the Sophisms were the essays written expressly in dialogue or conversational form (14 essays or 16% of the total). Some conversations were introduced with a section of prose before the conversation took center stage; others were entirely devoted to the conversation. Bastiat created stock characters to represent different sides in a debate which unfolded over several pages with the inevitable result that the free market advocate won the contest. Bastiat was quite inventive and often amusing in creating names for his characters, such as a "Mister Blockhead" (who was a Tax Collector), "The Utopian" (who was a Minister in the government who fantasized about introducing a radical free market reform program), and "Mister Prohibitionist" (a defender of protectionist policies) and "The Law Factory" (the Chamber of Deputies). His other characters were often fairly prosaic in their names, such as his favourite "Jacques Bonhomme" (the wiley French everyman), John Bull (the pragmatic British everyman who is used here to advocate postal reform), various "Petitioners" to government officials, "Ironmasters" and "Woodcutters", and the "Economist" and the "Artisan". In some cases the character "Jacques Bonhomme" was described as a "wine producer" which, given the fact that Bastiat was a farmer who came from a wine producing region, strongly suggests that sometimes the free trade arguments he was placing in Jacques mouth got a bit personal. [39]

The published collections of Economic Sophisms were not the only place where Bastiat used the constructed dialog form. On one occasion he used it in an article he published in his home town newspaper Mémorial bordelais (February 1846) on "Théorie du bénéfice" (The Theory of Profit) where he creates a conversation between the Mayor of Bordeaux and a Lobbyist who wants a new city toll to be imposed on all iron goods coming into the city so that his higher cost foundry will be profitable. [40] On two occasions in June 1848 he wrote short pieces for his street magazine Jacques Bonhomme where the French everyman Jacques Bonhomme has discussions with, first the Minister of Finance in a foreign country by the name of "Lord Budget", and secondly with a profligate spendthrift named Old Man Mathurin. In ES3.26 "Une mystification" (A Hoax) Jacques visits another country and describes a meeting he had with a Minister by the name of "Lord Budget" (in English) who describes how he uses indirect taxation to fool the people by giving back only some of the taxes they pay the state in the form of services and assistance and keeping the rest for himself and his friends - hence "the Hoax". In ES3.28 "Funeste gradation" (A Dreadful Escalation) Jacques tells a story about visiting Old Man Mathurin who told him he had solved his debt problems by borrowing more money to pay off his creditors. Jacques scoffs at him and tells him that the only way to pay off his debts is to spend less and earn more. [41]

A quite innovative dialog form which Bastiat had much to do with inventing was the use of the characters "Robinson Crusoe" and "Friday" to create what might be called "thought experiments" in economic thinking In these special dialogs Bastiat would simplify quite complex economic arguments, cheekily putting interventionist and protectionist arguments into the mouth of the "civilized" European Crusoe and the more liberal free market ideas into the mouth of the "savage" Friday. [42]

iii. Stand alone Economic Tales or Fables (EF)

Given Bastiat's love of literature and his penchant for the fairy tales and fables of Jean de La Fontaine (1621–95), Charles Perrault (1628-1703), [43] and Jean-Pierre Florian (1755-1794), it is not surprising that he would turn his hand to writing his own "economic tales" or fables (10) which comprise 11.5% of the total. Another model might have been Voltaire's "philosophic tales" such as Candide (1759) [44] although Bastiat does not quote him as he does Fontaine, Perrault, and Florian. These "economic tales" are coherent stories or tales designed to make an important economic point in a light hearted manner. [45] They are self-contained, usually have no introduction by a narrator (such as Bastiat), and are often very funny and poignant. Bastiat wrote eight of them as Sophisms and they are spread out quite evenly over the various collections he had published, suggesting that he regarded them as an essential part of the genre. Some of the more noteworthy tales are the following: ES1.10 "Réciprocité" (Reciprocity) (Oct. 1845) [46] which is a fable in which the councillors of two wittily named towns "Stulta" (a Latin pun which could be translated as "Stupidville") and "Puera" ("Childishtown") try to figure out how best to disrupt trade between themselves, thinking like their national counterparts that trade barriers will increase "national" or in this case "local" production; ES2.07 "Conte chinois" (A Chinese Tale) [47] in which a free trade-minded Emperor of China causes his protectionist-minded Mandarins considerable grief; ES2.13 "La protection ou les trois Échevins" (Protection, or the Three Municipal Magistrates) [48] which is in fact a small, four act play with multiple characters who argue about the pros and cons of protection and free trade; and probably the best known of Bastiat's tales WS.01 "La vitre cassée" (The Broken Window) [49] where there is a brief prose introduction before a wonderful story about Jacques Bonhomme's broken window is told, along with its impact on the Glazier and the Shoemaker. These "economic tales" are probably Bastiat's best work in making the study of economics less "dry and dull" (as he lamented) and it is a pity he did not write more of them as he seemed to have quite a talent for it.

iv. Fictional Letters or Petitions to Government Officials and Other Documents (P)

On a par with his "economic tales", at least in terms of the number written (8 or 9.2% of the total) and their originality and creativity, are the fictional letters or petitions to government officials which Bastiat wrote. In most cases they were quite satirical and very funny. These fake letters and petitions were written to members of the Chamber of Deputies, various Cabinet Ministers, the Council of Ministers, and even to the King, usually with requests for preposterous solutions to their economic problems. Bastiat uses the "reductio ad absurdum" method to argue his point, taking a conventional argument used by protectionists, such as a request to keep cheap foreign imports out of the country because it hurts domestic producers, and pushing it to an absurd extreme, the best example being his ES1.07 "Pétition des fabricants de chandelles, etc." (Petition by the Manufacturers of Candles, etc.) (Oct. 1845) [50] . In this case, a straight-faced group of petitioners who make artificial light (such as candles and lamps) ask the Chamber of Deputies to pass a law forcing all consumers to block out the cheap natural light of the sun during daylight hours in order to boost demand for their products for which of course the producers charge a hefty price. The ridiculousness of their demand and the logical similarity with the demands of the protectionists is the point Bastiat was trying to make in this clever and witty manner. Another kind of document which Bastiat liked to "invent" was the historical document such as the ES3.20 "Monita secreta" (The Secret Handbook) (Feb. 1848) [51] based upon a seventeenth century forgery of a manual which purported to show how the Jesuits secretly went about recruiting members to their cause and lobbying governments to get the legislation they wanted. Here, Bastiat "discovers" a secret manual or guide book written to assist the protectionists in their political and intellectual struggle against the free traders. By "exposing" this secret and conspiratorial document for the first time to the French public, Bastiat has a field day. [52]

v. Essays written in more Formal or Academic Prose (FP)

These are longer pieces and are written in a more academic style in which quite sophisticated and complex theoretical and historical ideas are discussed. There were 12 which comprise 14% of the total. There are relatively few in the collections specifically called Economic Sophisms (only four), three of the five political sophisms, and the Introduction to WSWNS. [53] The first two examples are the opening two essays in Economic Sophisms Series II (1848) [54] on ES2.01 "Physiologie de la Spoliation" (The Physiology of Plunder) and ES2.02 "Deux morales" (Two Moral Philosophies) and are discussed in more detail in another paper. [55] There is no information on any previous publication of these pieces so it is possible that they were written especially for the second series of Economic Sophisms. Another two essays were written for the more academic and sophisticated Journal des Économistes. ES2.09 "Le vol à la prime" (Theft by Subsidy) appeared in the January 1846 issue [56] and is notable for Bastiat's testy reaction to reviews of Economic Sophisms ( Series I) for being "trop théorique, scientifique, métaphysique" (too theoretical, scientific, and metaphysical), the defence of his strategy for "calling a spade a spade" in his writings (such as describing government taxation and tariffs as a form of "theft"), and for the appearance of one the wittiest pieces he ever wrote, a parody of Molière's parody, where Bastiat writes (in Latin) an "Oath of Office" for aspiring government officials. The second essay ES3.24 "Funestes illusions" (Disastrous Illusions)" appeared in the March 1848 issue of the Journal des Économistes [57] and is interesting because it was published at the very beginning of the 1848 Revolution and shows the growing alarm felt by the political economists at the rise of socialist and interventionist ideas among the revolutionaries.

vi. Direct Appeals to the Workers and Citizens of France (A)

This type of essay is the one most infrequently used by Bastiat (4 or 4.6%). The first occurs in ES1 12 [58] and is a direct appeal to the Workers, perhaps modelled on a real speech Bastiat gave on the hustings as he campaigned for the French Free Trade Association. We do not have any information about its original date or place of publication. The other two occurrences are wall posters which originally appeared in Bastiat's and Molinari's revolutionary paper Jacques Bonhomme in June 1848. They were designed to appeal to the workers and citizens of Paris at the beginning of the 1848 Revolution. The idea was to post them on walls in the streets of Paris so the passers by could read them. [59] In ES3.22 "Funeste remède" (A Disastrous Remedy (14 March, 1848) [60] Bastiat likens the state once again to a quack doctor who tries to cure the patient (the taxpayers of France) by giving him a blood transfusion by taking blood out of one arm and pumping it into the other arm (his parody of Molière appeared that same month in the Journal des Économistes). In ES3.21 "Soulagement immédiat du peuple" (The Immediate Relief of the People) (12 March 1848) [61] he argues that the state is not like Christ and cannot miraculously turn water into wine, or in this case give out more in subsidies than it takes in in taxes. Both were short, emotional appeals to the Parisian crowd to spurn the seductive socialist policies of the new Provisional Government.

The Purpose of the Economic Sophisms↩

Introduction

I think Bastiat had several purposes in mind in writing the "sophisms". The first purpose was the fairly narrow one of refuting the erroneous theoretical ideas and justifications for government policy put forward by the Protectionists. There is in addition a broader purpose which was to go beyond the ideas and behaviour of just one powerful vested interest group of his day and to address the general problem of the morality and the modus operandi of what he called "la classe spoliatrice" (the plundering class), of which the Protectionists were a key member in his day. To do this, Bastiat had to develop a "theory of plunder" (especially his idea of "la spoliation légale" (legal plunder)), and a special rhetoric to use in exposing and opposing the actions of this class.

The rhetorical strategy he developed was to mock and ridicule the arguments the plundering class used to justify its activity; to use "harsh language" ("calling a spade a spade" ) in order to bring to people's attention the fact that they were being deceived and were the victims of force and fraud, and to shame the plundering class with moral arguments drawn from religion, philosophy, and economics. His harshest language can be found in the introduction to his early piece on Cobden et la Ligue (Cobden and the (Anti-Corn Law) League) (written in mid-1845), [62] ES2.09 "Le vol à la prime" (Theft by Subsidy) (Jan. 1846), [63] the conclusion to ES1 (probably written in late 1845), [64] and the first two chapters of ES2 (probably written in late 1847). [65] I will provide here an example of this harsh rhetoric from his Introduction to Cobden and the League. The other pieces will be discussed below.

The anger Bastiat obviously felt at the actions of "l'oligarchie britannique" (the British oligarchy) which controlled British politics and economic policy is palpable, as these passages clearly show. It would not be long before Bastiat was using similar sharp language, such was "ravir" ("ravish", abduct, even rape), "spoliation" (plunder), deceptive euphemistic language ("protection"), "la plaie" (the plague), "la spoliation légalement exercée" (legal plunder), "une oligarchie puissante et impitoyable" (a powerful and pitiless oligarchie), against the largest landowners and industrialists of his own country:

La possession du sol met aux mains de l'oligarchie anglaise la puissance législative; par la législation, elle ravit systématiquement la richesse à l'industrie." p. xiv Online |

Possession of the soil puts into the hands of the English oligarchy the Legislative power; by means of legislation it systematically seizes wealth from industry. |

Il faut rendre justice à l'oligarchie anglaise. Elle a déployé, dans sa double politique de spoliation intérieure et extérieure, une habileté merveilleuse. Deux mots, qui impliquent deux préjugés, lui ont suffi pour y associer les classes mêmes qui en supportent tout le [xv] fardeau : elle a donné au monopole le nom de Protection, et aux colonies celui de Débouchés. pp. xiv-xv Online |

One has to give due recognition to the English oligarchy. It has demostrated marvellous skill in its twin policy of interior and exterior plunder. The use of two words, and the prejudices they imply, were enough to win over the support of the very classes which carry the entire burden: it gave monopoly the name "Protection", and colonies the name "Marketes". |

Ainsi l'existence de l'oligarchie britannique, ou du moins sa prépondérance législative, n'est pas seulement une plaie pour l'Angleterre, c'est encore un danger permanent pour l'Europe. p. xv Online |

Thus the existence of the British oligarchy, or at least its legislative supremacy, is not only a plague for England, it is also a permanent danger for Europe. |

C'est une pure question de liberté commerciale, dit-on; et ne voit-on pas que la liberté du commerce doit ravir à l'oligarchie et les ressources de la spoliation intérieure, les monopoles, et les ressources de la spoliation extérieure, les colonies, puisque monopoles et colonies sont tellement incompatibles avec la liberté des échanges, qu'ils ne sont autre chose que la limite arbitraire de cette liberté! p. xv Online |

It is a pure question of commercial liberty, they say! But they don't see that (true) commercial liberty has to seize/take away from the Oligarchy the resources (it gets) from internal plunder and monopolies, and the resources (it gets) from external plunder and colonies, since monopolies and colonies are so incompatible with free trade that they are on the other side of the boundary line which defines what this liberty is! |

Pour le savoir, il suffit de comparer le prix du blé étranger, à l'entrepôt, avec le prix du blé indigène. La différence multipliée par le nombre de quarters consommés annuellement en Angleterre donnera la mesure exacte de la spoliation légalement exercée, sous cette forme, par l'oligarchie britannique. p. xx Online |

In order to undertsand this it is sufficient to compare the price of foreign wheat in the warehouses with the price of domestic wheat. The difference between them, multipied by the number of tons annually consumed in England will provide the exact amount of the plunder which is legally carried out, in this particular case, by the British oligarchy. |

Les dynasties et les empires dépendaient de ces luttes. Mais les triomphes de la force peuvent être éphémères ; il n'en n'est pas de même de ceux de l'opinion ; et quand nous voyons tout un grand peuple dont l'action sur le monde n'est pas contestée, s'impreigner des doctrines de la justice [lxviii] et de la vérité, quand nous le voyons renier les fausses idées de suprématie qui l'ont si longtemps rendu dangereux aux nations, quand nous le voyons prêt à arracher l'ascendant politique à une oligarchie cupide et turbulente , gardons-nous de le croire, alors même que l'effort des premiers combats se porterait sur des questions économiques, que de plus grands et de plus nobles intérêts ne sont pas engagés dans la lutte. Car, si à travers bien des leçons d'iniquité, bien des exemples de perversité internationale, l'Angleterre, ce point imperceptible du globe, a vu germer sur son sol tant d'idées grandes et utiles; si elle fut le berceau de la presse, du jury, du système représentatif, de l'abolition de l'esclavage, malgré les résistances d’une oligarchie puissante et impitoyable, que ne doit pas attendre l'univers de cette même Angleterre, alors que toute sa puissance morale, sociale et politique aura passé aux mains de la démocratie, par une révolution lente et paisible, péniblement accomplie dans les esprits, sous la conduite d'une association qui renferme dans son sein tant d'hommes dont l'intelligence supérieure et la moralité éprouvées jettent un si grand éclat sur leur pays et sur leur siècle ? Une telle révolution n'est pas un évènement, un accident, une catastrophe due à un enthousiasme irrésistible, mais éphémère. C'est, si je puis le dire, un lent cataclysme social qui change toutes les conditions d'existence de la société, le milieu où elle vit et respire. C'est la justice s'emparant de la puissance et le bon sens entrant [lxix] en possession de l'autorité. C'est le bien général, le bien du peuple, des masses, des petits et des grands, des forts et des faibles devenant la règle de la politique; c'est le privilège, l'abus, la caste disparaissant de dessus la scène, non par une révolution de palais ou une émeute de la rue, mais par la progressive et générale appréciation des droits et des devoirs de l'homme. En un un mot, c'est le triomphe de la liberté humaine, c'est la mort du monopole, ce Protée aux mille formes tour à tour conquérant, possesseur d'esclaves, théocrate, féodal, industriel, commercial, financier et même philanthrope. Quelque déguisement qu'il emprunte, il ne saurait plus soutenir le regard de l'opinion publique, car elle a appris à le reconnaitre sous l'uniforme rouge, comme sous la robe noire, sous la veste du planteur, comme sous l'habit brodé du noble pair. Liberté à tous! à chacun juste et naturelle rémunération de ses œuvres ! à chacun juste et naturelle accession à l'égalité en proportion de ses efforts, de son intelligence, de sa prévoyance et de sa moralité. Libre échange avec l'univers ! Paix avec l'univers ! Plus d'asservissement colonial, plus d'armée, plus de marine que ce qui est nécessaire pour le maintient de l'indépendance nationale! Distinction radicale de ce qui est et de ce qui n'est pas la mission du gouvernement et de la loi ! L'association politique réduite à garantir à chacun sa liberté et sa sûreté contre toute aggression inique, soit du dehors, soit au dedans; impôt équitable pour défrayer convenablement les hommes chargés de cette mission, et non pour [lxx] servir de masque, sous le nom de débouchés à l'usurpation extérieure, et sous le nom de protection à la spoliation des citoyens les uns par les autres. Voilà ce qui s'agite en Angleterre, sur le champ de bataille, en apparence si restreint, d'une question douanière; mais cette question implique l'esclavage dans sa forme moderne, car, comme le disait au Parlement un membre de la Ligue, M. Gibson : « S'emparer des hommes pour les faire travailler à son profit, ou s'emparer des fruits de leur travail, c'est toujours de l'esclavage, il n'y a de différence que dans le degré. »p. lxviii-lxx. Online |

Political dynasties and empires depend upon these battles (in war). But triumphs by means of force can be ephemeral. It is not the same with those (triumphs) by means of public opinion, and when we see all the members of a great people whose influence on the entire world is not contested, imbued with ideas about justice and truth, when we see them denying false ideas about (national) supremacy which for such a long time has made them a danger to other nations, when we see them ready to tear away the political supremacy of a greedy and unruly oligarchy, let us not think that, even though the focus of the first fight was on economic matters, the most powerful and most noble interests were engaged in the battle. Because, if England, in spite of its displays of iniquity, in spite of its acts of international perversity, has seen so many great and useful ideas take root in its soil - something which has been imperceptiabel to the rest of the globe; if it has been the cradle of a free press, trial by jury, the system of representative government, the abolition of slavery, in spite of the opposition of a powerful and ruthless oligarchy, one should not expect the world of this very same England, until all its moral, social, and political power has passed into the hands of democracy, by means of a slow and peaceful revolution, achieved with difficulty in the minds of the people, under the leadership of an Association (the Anti-Corn Law League) which embodies so many men who have demonstrated their superior minds and morality, have thrown down such a challenge for their country and their century? Such a revolution is not a mere event, an accident, a catastrophe brought about by enthusiasm which is irrestable but ephemeral. It is, if I may so so, a slow social cataclysm which will change all aspects of life in society, the milieu in which we live and breathe. It is justice seizing power and common sense taking possession of (public) authority. It is the general good, the good of the people, the masses, the great and the small, the weak and the strong, becoming the law of (public) policy. It is privlege, (legal) abuse, and caste disappearing from the scene, not by means of a palace coup or a street riot, but by the growing and widespread understanding of the rights and duties of mankind. In a word, it is the triumph of human liberty, it is the death of monopoly, this protean force with its thousands of different shapes which one day is a conquerer, the next day an owner of slaves, a theocrat, a feudal lord, an industrialist, a merchant, a financier, and even a philanthropist. Whatever disguise it assumes, it no longer has the support of public opinion because it has learned to recognise it when it wears a red uniform, a black robe, the planter's vest, the embroided coat of a noble lord. Liberty for everyone! To everone the just and natural reward for their labour! To everyone the just and natural attainment of equality in proportion to their effort, intelligence, foresight and moral behaviour! Free trade with the entire universe! Peace with the entire universe! No more colonial enslavement, no more army, no more navy beyond what is necessary to maintain our national independence! A radical distinction between what is and what is not the (proper) purpose of government and the law! Political association reduced to (the function) of protecting each person's liberty and safety against all unjust aggression, whether from abroad or within (the nation)! Just taxation in order to pay appropriately those who are charged with (carrying out) this mission, and not to serve as a mask to disguise foreign usurpation under the name of "markets", and the plunder of some citizens by other citizens under the name of "protection." This is what is shaking up England on the battlefield over the question of tariffs, which on the surfacce seems so restrained. But this question implies slavery in its modern form because, as a member of the League, Mr. Gibson, said in Parliament, "To seize men in order to make them work for (someone's) profit, or to seize the fruits of their labiour, is always slavery. It is only a difference of degree." |

On being a "good economist": Refuting the Erroneous Beliefs and Arguments of the Protectionists

Some definitions are in order so we can better understand Bastiat's sometimes confusing use of the terms "sophism" and "fallacy". In particular, confusion can arise because the word "sophism" was used to describe both a kind of argument or set of ideas, as well as the essay in which those arguments were rebutted.

It is also important to understand what Bastiat meant by a "good economist" and a "bad economist" and what he thought the duties of the "good economist" were, namely to show people what the often "unseen" consequences of economic policy were. [66] He made this distinction quite clear in the Introduction his essay WSWNS: [67]

Dans la sphère économique, un acte, une habitude, une institution, une loi, n'engendrent pas seulement un effet, mais une série d'effets. De ces effets, le premier seul est immédiat; il se manifeste simultanément avec sa cause, on le voit. Les autres ne se déroulent que successivement, on ne les voit pas, heureux si on les prévoit! |

In the sphere of economics an action, a habit, an institution, or a law engenders not just one effect but a series of effects. Of these effects only the first is immediate; it is revealed simultaneously with its cause; it is seen. The others merely occur successively; they are not seen; we are lucky if we foresee them. |

Entre un mauvais et un bon Économiste, voici toute la différence: l'un s'en lient à l'effet visible; l'autre tient compte et de l'effet qu'on voit et de ceux qu'il faut prévoir. |

The entire difference between a bad and a good Economist is apparent here. A bad one relies on the visible effect, while the good one takes account both of the effect one can see and of those one must foresee. |

Mais cette différence est énorme, car il arrive presque toujours que, lorsque la conséquence immédiate est favorable, les conséquences ultérieures sont funestes, et vice versâ. — D'où il suit que le mauvais Économiste poursuit un petit bien actuel qui sera suivi d'un grand mal à venir, tandis que le [4] vrai Économiste poursuit un grand bien à venir, au risque d'un petit mal actuel. |

However, the difference between these is huge, for it almost always happens that when the immediate consequence is favorable, the later consequences are disastrous and vice versa. From which it follows that a bad Economist will pursue a small current benefit that is followed by a large disadvantage in the future, while a true Economist will pursue a large benefit in the future at the risk of suffering a small disadvantage immediately. |

Thus for Bastiat, a "good economist" had to expose and correct things like erroneous thinking, false arguments, half truths, outright lies and deception put forward by vested interests, and the public's naïveté about the motives of those who wielded political power. Writing his scores of "sophisms" was the means Bastiat chose to achieve these ends in a provocative and often amusing way.

Beliefs and Arguments: a "Fallacy" vs. a "Sophism"

A Fallacy is a belief or argument which is not true under any circumstances because it is based on unsound premisses, faulty reasoning, or false or partial data. It can be refuted by better data and the application of sound economic theory. This is the task of a "good"" economist and the well informed economic journalist.

A typical fallacy (Fallacy No. 2) [68] is the argument that since labour is used to produce wealth then a nation’s wealth can be increased by increasing the amount of labour it takes to produce things. Bastiat’s typical response is to argue that real increases in wealth are the result of greater output which comes from the greater productivity created by human invention, machinery, or better organization. Thus more can be produced with less effort or labour, which are then freed up for other productive purposes. See a classic example of Bastiat's method of argument in the clever and very witty “Un chemin de fer négatif” (A Negative Railway) (c. 1845). [69]

A Sophism is a belief or argument which is partly true and which is used as a specious argument designed to mislead the pubic in order to benefit some vested interest. The task of the "good economist" is to show its partially true nature by pointing out the part or parts which are missing from the analysis (often what Bastiat called "the unseen"), as well as to identify the interest group which is benefitting from the government measure. A related task is to show how the ordinary taxpayer or consumer (whom Bastiat called "les dupes" (the dupes, i.e. those who are duped or deceived by the sophism)) foots the bill.

A typical sophism (Sophism No. 1: “The Seen and the Unseen”) is the idea that the destruction of property leads to greater sales and production which increases a nation's wealth. The counterargument is that individual producers in a given industry may benefit from selling replacements for destroyed property ("the seen") but the overall economy loses on net balance because overall wealth is destroyed or redistributed ("the unseen"). Bastiat's classic statement of this is in the famous story of “La vitre cassée” (The Broken Window) in his collection WSWNS (July 1850). [70]

When Bastiat began writing in 1844-45 there was a set of such beliefs and arguments commonly used by the protectionists of his day to justify the imposition of tariffs on imported foreign goods, the outright banning of some imports, and the granting of taxpayer funded subsidies to domestic producers, which together were called "Sophisms". Since Bastiat had begun his career attacking the "Sophisms" of the protectionists these were called "Economic Sophisms".

In the Appendix below we have identified three main kinds of "Sophism" and four main kinds of "Fallacy" Bastiat discusses in his writing. These are:

Sophisms

- Sophism No. 1: “The Seen and the Unseen”

- Sophism No. 2: “Positive and Negative Ricochet Effects”

- Sophism No. 3: “The Use of Euphemisms and Frightening Language to Make One’s Arguments”

Fallacies:

- Fallacy No. 1: “The Interests of the Producers are the Real Interest of the Nation” (not the Interests of the Consumers”

- Fallacy No. 2: “Real Wealth is measured by the Amount of Labor/Effort expended to Create Goods and Services, not the Total Amount of Goods and Services made available to Consumers”

- Fallacy No. 3: “Free Trade harms the Interests of the Nation”

- Fallacy No. 4: “The State can and should provide for the Needs of the People”

- Fallacy No. 5: Other General Economic Fallacies

These general categories are distinguished from each other by a common set of arguments or subject matter. Each one of these general categories includes a larger number of specific examples which Bastiat dealt with in his writings. It should be noted that the categories of "Sophisms" are more general, and the category of "Fallacies" are more specific. See the Appendix below for details.

In the nineteenth century translators of Bastiat’s Economic Sophisms used the word “Fallacies” which is somewhat misleading as there is a difference between the two, as noted above. [71] A Sophism is something which is partly true and which is used as a specious argument designed to mislead the pubic in order to benefit some vested political or economic interest. A Fallacy is a clearly mistaken belief based upon faulty reasoning or incorrect assumptions. Bastiat himself sometimes goes from one to the other in his writings but I believe he does in the end have a clear distinction in mind between intellectual error (“the fallacy”) and the rhetorical purposes to which partial truth and partial error can be used in arguments over government policies (“the sophism”). In the discussion which follows we try to maintain this distinction where possible, although it must be acknowledged that sometimes “fallacies” can be used in sophistical ways, and some “sophisms” are borderline fallacies if they are repeated often enough.

"Sophisms": the Essays and the Books

For Bastiat and his readers, a “sophism” could also refer to the essay in which the "sophism" (i.e. the erroneous or only partly true belief or argument) was rebutted or corrected. And thus, the collection of such essays were known as "the sophisms" or "his sophisms". By our reckoning Bastiat wrote a total of 87 "sophisms" or essays of this kind.

Typically, a "sophism" was a short essay written for a general audience which attempted to debunk a commonly held misperception or misunderstanding of an economic point of view. The essay would be written in a less formal, familiar style, often in the form of a dialog between two individuals who held opposing views. Or, it would be a satirical “petition” to the government or king requesting some obviously absurd law to “protect” their industry from competition.

Finally, another usage of the term "Sophism" was in the titles of the books in which his "sophisms" (i.e. the essays themselves) were published, most notably the Economic Sophisms. There were two in his lifetime: Sophismes Économiques (Economic Sophisms) (1846) and Sophismes Économiques. Séries II (Economic Sophisms. Series Two) (1848) - and a third with longer essays in the same style which did not have have "Sophisms" in the title but which was referred to in the text, namely Ce qu'on voit et ce qu'on ne voit pas, ou l'Économie politique en une leçon (What is Seen and What is Not Seen, or Political Economy in One Lesson) (1850).

Political and other kinds of Sophisms

Since Bastiat is a “political economist” it is sometimes difficult to distinguish between his purely “economic” writings and his purely “political” writings. Although he called his two collections of essays “Economic Sophisms” (Series I in 1846 and Series II in 1848) they enter the realm of politics on many occasions. He began writing his “economic sophisms” in 1845 and 1846 in order to debunk the common arguments used to defend the policy of protectionism, but Bastiat also wrote might be called “political sophisms”, essays in which he debunked erroneous arguments and beliefs of a more political nature, especially concerning the proper role of the State, the highly restricted French voting system prior to the February Revolution of 1848, and the way in which powerful vested interest groups controlled the legislature in order to introduce laws to benefit themselves. The two are closely related in that the protectionists were only able to get special privileges because they controlled the Chamber of Deputies and the various Councils which advised the government on economic policy. Bastiat wrote five such "political sophisms" (i.e. essays) which are listed in in the Appendix. One of these he explicitly called a “sophism” (“Electoral Sophisms”), and his famous essay on “The State” is quite similar in style and purpose to the other sophisms in that it is an attempt to debunk the fallacy (or what Bastiat calls “the great fiction”) that everybody can live off the largess of the welfare State at the expense of everybody else. See below for a discussion of his "political sophisms".

Bastiat also believed that one should refute the "sophisms" (i.e. false or faulty beliefs and arguments) used in other areas such as the following: "Sophisme théocratique, Sophisme politique, Sophisme financier" (theocratic sophism, political sophism, financial sophism). [72] But apart from the handful of "political sophisms" he wrote, he did not have time to address all of these other kinds of sophisms.

One kind of sophism Bastiat was especially keen to write on in more detail and which he had begun thinking about in 1847 was “the sophism of the ricochet effect”. He mentions this in passing on several occasions and regrets not having developed it more completely. See the discussion below for details.

"Le sophisme souche" (the root of all sophisms)

In a very short and unfinished note from 1847, ES3.15 "Le profit de l’un est le dommage de l’autre" (One Man’s gain is another Man’s Loss) (c.1847), Bastiat states that he thinks the root of all misunderstandings about the nature of free market economics, and thus all the forms of "sophisms", is the notion that "Le profit de l’un est le dommage de l’autre" (a profit of one person is a loss for another). It comes from an essay written by Montaigne and was quoted several times by Bastiat in his writings. See the discussion below for more details about this important sophism.

Laughing at and Ridiculing "la class spoliatrice" (the exploiting class)

The kinds of arguments and the rhetorical devices used in the Sophisms were made by Bastiat for a very specific purpose, namely to undermine the claims of the small group of people who exercised this power that, 1) the exercise of this power was legitimate, and 2) that they were exercising this power for the good of "the people" or for the improvement of "national industry", when in fact it was being exercised for their own personal or class benefit. He was quite explicit about what his strategy had been on the eve of the February Revolution of 1848 when everything changed with the coming of democracy and the increased power of socialist groups in the Chamber.

Before proceeding any further, a couple of points need to be made. The first is that Bastiat had a clear theory of class and class exploitation which was the basis of his critique of the French state and its economic policies. I have dealt with this topic at some length elsewhere, [73] but it can be summarized as follows:

- Bastiat defined "la spoliation" (plunder) as the taking of another person’s property without their consent by force or fraud. Those who lived by plunder constituted “les spoliateurs” (the plunderers) or “la classe spoliatrice” (the plundering class). Those whose property was taken constituted “les spoliés” (the plundered) or “les classes spoliées” (the plundered classes).

- over time plunder became "organised" by the state into what he calls "la spoliation légale" (legal plunder) or plunder which was done with the sanction or under the protection of the law

- before the expansion of the franchise in February 1848 and the rise of modern mass political groups or parties, plunder was "partial" as it done by and for the benefit of a small group of people (such as slave owners, large landowners, industrialists, the church, the military, the aristocracy). With the establishment of democracy and party politics he thought plunder had been "universalized" whereby many groups jostled for control of the state and thus the flow of "plunder" and privilege that came with this

Bastiat provided a chapter length discussion of his theory of plunder in the first chapter of SE2 which was probably written in late 1847 as the book appeared in print in January 1848. It was a called "Physiologie de la Spoliation" (The Physiology of Plunder) [74] . He would continue to write additional articles on plunder throughout the remainder of his life, culminating in his lengthy treatment of it in one of the last things he wrote La Loi (The Law) in July 1850. [75]

The second point which needs to be made here is that the first three books Bastiat published, Cobden et la Ligue (Cobden and the League) (July 1845), Sophismes Économiques (Jan. 1846), and Sophismes Économiques, Séries II. (Jan. 1848), were written before the expansion of the franchise in February 1848 and so were directed against the "partial plunder" of the small pre-revolution ruling class (what, in the case of Britain, Bastiat in Cobden and the League called "l'oligarchie anglaise" (the English oligarchy)). [76] Things would change after February 1848 when the partial plunder of the old ruling elite was forced to compete against the new would-be "universal plunderers" of the expanded electorate. His strategy, arguments, and rhetoric would have to change to suit these new circumstances. For the last couple of years of his life Bastiat was not able to settle on the best course to take and he often went back in forth between addressing the elite and the "people", and using the "dry and dull" language of economics and his humorous satire and "la piqûre du ridicule" (the sting of ridicule). [77]

So, to return to Bastiat's stated strategy as he articulated in March 1848 he said: [78]

Il m’est quelquefois arrivé de combattre le Privilége par la plaisanterie. C’était, ce me semble, bien excusable. Quand quelques-uns veulent vivre aux dépens de tous, il est bien permis d’infliger la piqûre du ridicule au petit nombre qui exploite et à la masse exploitée. |

I have sometimes fought against Privilege by joking about it. I think this was quite understandable. When a few people want to live at the expense of everybody else, it is totally permissible to inflict the sting of ridicule on the small number who exploit and the mass of people who are exploited. |

Aujourd’hui, je me trouve en face d’une autre illusion. Il ne s’agit plus de priviléges particuliers, il s’agit de transformer le privilége en droit commun. La nation tout entière a conçu l’idée étrange qu’elle pouvait accroître indéfiniment la substance de sa vie, en la livrant à l’État sous forme d’impôts, afin que l’État la lui rende en partie sous forme de travail, de profits et de salaires. On demande que l’État assure le bien-être à tous les citoyens ; et une longue et triste procession, où tous les ordres de travailleurs sont représentés, depuis le roi des banquiers jusqu’à l’humble blanchisseuse, défile devant le grand organisateur pour solliciter une assistance pécuniaire. |

Now, I am faced with another illusion. It is no longer a question of the privileges of particular indivdiuals, but of transforming privilege into a right common to all. The entire nation has conceived the odd idea that it could increase indefinitely the things necessary for life by handing them over to the State in the form of taxes in order for the State to give back (to the nation) a portion of it in the form of work, profit, and wages. We ask the state to ensure the well-being of every citizen; and a long and sorry procession, in which every sector of the workforce is represented, from the king of the bankers to the humblest laundress, parades before the "great organizer" in order to ask for financial assistance. |

We can hear echoes here of his new definition of "the State" which he would provide in his famous essay on L'État (The State) (June and September 1848). This essay went through three extensive revisions and expansions between its first appearance as a very short article of about 400 words in a street magazine, Jacques Bonhomme, in June 1848 shortly before the June Days uprising, [79] a second enlarged version of 2,000 words published in the up-market and prestigious Journal des débats in September 1848, [80] and its final version as a long essay of 3,900 words in a pamphlet published sometime in April 1849 during the campaigns for the elections for the new National Assembly which were held on 13-14 May. [81] In all three versions he draws up a list of the things the voters are demanding the state should do and this list varied only slightly from version to version. In its final form his definition was that:

L’ÉTAT, c’est la grande fiction à travers laquelle TOUT LE MONDE s’efforce de vivre aux dépens de TOUT LE MONDE. |

The state is the great fiction by which everyone endeavors to live at the expense of everyone else. |

In his mind the shift from elite exploitation, which had dominated his writing up to February 1848, to popular, democratic exploitation would also require a corresponding shift in rhetorical strategy in his writings. For example, it would probably be less useful for spreading free market ideas to a mass audience of democratic voters by publishing amusing rewrites of passages from a Molière play with which they would probably not be familiar, whereas quoting the fables of La Fontaine or the drinking songs of Béranger might still be very appealing to ordinary people.. Perhaps as well, satire and humour would be less effective in the post-February 1848 era than pointing out the waste and ineffectiveness of the policies of the new welfare state. This was a problem he grappled with without reaching a firm conclusion in the last couple of years of his life.

Shaming the Exploiting Class for their Immoral Actions

In addition to delegitimizing the elites who benefited from their exercise of political power by means of satire and humour, Bastiat also wished to expose the immorality of what they did on religious and philosophical grounds as well as economic grounds. According to the former their actions violated the property rights and the right to liberty of ordinary taxpayers and consumers. According to the latter the results of intervention and privilege were higher costs, distortions to the structure of production and consumption, and other numerous inefficiencies and impediments to economic growth and prosperity. He laid out this aim very clearly in the second chapter of Economic Harmonies Series II "Deux Morales" (Two Moral Philosophies). [82] In this chapter Bastiat reflects on what he is trying to achieve in writing the Economic Sophisms and how he can best achieve this aim. He calls the system of legal plunder which he wants to eliminate, "l'acte malfaisant" (harmful action), and sums up the two pronged task he thinks is necessary to achieve this in the following way: [83]

Il y a doue deux chances pour que l'acte malfaisant soit supprimé : l’abstention volontaire de l’être actif, et la résistance de l’acte passif. De là deux morales qui, bien loin de se contrarier, concourent : la morale religieuse ou philosophique et la morale que je me permettrai d’appeler économique. |

There are therefore two opportunities for a harmful action to be eliminated: the voluntary abstention of the active being (those doing the plundering) and the resistance of the passive being (those being plundered). |

The first of the two moralities, "la morale religieuse" (religious morality), has a role to play in the former, i.e. to persuade those carrying out the plundering to see the immorality of what they are doing and to cease doing it. However, Bastiat is extremely sceptical that this has ever worked in history, pointing out that no ruling class has ever voluntarily given up their privileges because of any moral qualms they might have had about them. [84] Instead, he thinks it should be the task of political economy, or "la morale économique" (economic morality), to assist those being plundered to resist their oppressors "actively". In another passage he states: [85]

Elle lui montre les effets des actions humaines, et par cette simple exposition, elle le stimule à réagir contre celles qui le blessent, à honorer celles qui lui sont utiles. Elle s’éfforce de répandre assez de bon sens, de lumière et de juste défiance dans la masse opprimée pour ren dre de plus en plus l’oppression difficile et dangereuse. … |

It (political economy) shows them the effects of human actions and, by this simple demonstration, stimulates them to react against the actions that hurt them and honor those that are useful to them. It endeavors to disseminate enough good sense, enlightenment and justified mistrust in the oppressed masses to make oppression increasingly difficult and dangerous… |

La somme des maux l’emporte toujours, et nécessairement, sur celle des biens, parce que le fait même d’opprimer entraîne une déperdition de forces, crée des dangers, provoque des représailles, exige de coûteuses précautions. La simple exposition de ces effets ne se borne donc pas à provoquer la réaction des opprimés , elle met du côté de la justice tous ceux dont le cœur n’est pas perverti, et trouble la sécurité des oppresseurs eux-mêmes. |

The sum of evil always outweighs the good, and this has to be so, since the very fact of oppression leads to a depletion of force, creates dangers, triggers retaliation and requires costly precautions. A simple revelation of these effects is thus not limited to triggering a reaction in those oppressed, it rallies to the flag of justice all those whose hearts have not been corrupted and undermines the security of the oppressors themselves. |

There was room in Bastiat's mind for strategic cooperation between the "two moralities" which could be more effective if it were organized into an ideological "pincer movement" in the war against immorality and legal plunder: [86]

Que les deux morales, au lieu de s’entre-décrier, travaillent donc de concert, attaquant le vice par les deux pôles. Pendant que les Economistes font leur œuvre, dessillent les Orgons, déracinent les préjugés, excitent de justes et nécessaires défiances, étudient et exposent la vraie nature des choses et des actions, que le moraliste religieux accomplisse de son côté ses travaux plus attrayants mais plus difficiles. Qu’il attaque l’iniquité corps à corps; qu’il la poursuive dans les fibres les plus déliées du cœur; qu’il peigne les charmes delà bienfaisance, de l’abnégation , du dévouement ; qu’il ouvre la source des vertus là où nous ne pouvons que tarir la source des vices, c’est sa tâche, [38] elle est noble et belle. |