“BASTIAT'S THEORY OF HARMONY AND DISHARMONY:

AN INTELLECTUAL HISTORY

”

By David M. Hart

[Created: 4 December, 2023]

[Revised: 5 December, 2023 ] |

Editor’s Note

This essay is part of series on some of Bastiat’s key ideas, such as the seen and the unseen, class, harmony and disharmony, human action, and plunder.

It includes links to my “replica” editions of Bastiat’s original works in French.

Table of Contents

- Introduction and Summary

- Harmony and Disharmony

- Concept Map

- Introduction: The Harmony of the Providential Plan

- The Harmony of Natural Laws

- Harmonies Social and Economic

- What did he mean by "social harmonies"?

- What did he mean by "economic harmonies"?

- Bastiat's Theory of Disharmony

- Endnotes

Introduction and Summary

The French economist Frédéric Bastiat (1801-1850) is best known for his witty and clever critiques of tariff protection and government subsidies in his two collections of Economic Sophisms (1846, 1848), [1] his marvelous short book on opportunity cost What is Seen and What is not Seen (1850) - the last thing he ever wrote, [2] and his unfinished economic treatise Economic Harmonies (1850, 1851). [3] Central to the latter was the idea that if individuals were left free to act upon their "rightly understood self-interest" [4] and engage in voluntary transactions with others, this would "tend" to promote peace, prosperity, and “l’harmonie” (harmony) for society as a whole. A variety of "spontaneous orders" (or what he termed “les organisations naturelles” (natural organisations) would emerge to make it possible to satisfy individual and social "needs" in a mutually beneficial way. The flip side of the coin was that if individuals or governments engaged in coercion in order to control, regulate, or prohibit these voluntary transactions and interfere with these "natural organisations" then “la dissonance” (disharmony) would inevitably be the result. These interventions, regulations, and acts of violence were “les causes/forces perturbatrices” (disturbing factors/forces) which upset the previous "harmonious" relationships and included things such as war, slavery, theocracy, monopoly, protectionism, government regulation (or "governmentalism"), and socialism /communism - in other words "plunder" in all its different forms. Governments attempted to regulate and control individuals by creating what he termed “les organisations artificielles” (artificial organisations) (or what Hayek called "imposed orders") run by organisers, regulators, or what he termed "mechanics" of the "social mechanism." However, markets and other the "spontaneous orders" attempted to reassert themselves to correct these errors, distortions, and "dislocations" and restore harmony. Bastiat called these “les forces réparatrices” (repairing or restorative forces).” [5]

Bastiat developed a sophisticated set of arguments over several years to describe the nature of, and explain the causes and the consequences of, these polar opposite concepts of "harmony" and "disharmony", the history of which I have attempted to trace in several notes and short essays I have written. He died before he could finish his ambitious multi-volume project, only being able to see into print the first half of a book on "economic harmonies" at the beginning of 1850, and which his friends Prosper Paillottet and Roger de Fontenay attempted to complete with material from his drafts and sketches in an expanded posthumous edition published in mid-1851. Bastiat had planned to write another volume on "social harmonies" which would cover human relationships and institutions in a more general fashion, as well as a volume on "The History of Plunder", or what we might call "The Disharmonies," in which he would explore the role that war, class exploitation, and plunder played in destroying the harmonies that had been created by free individuals going about their own business. [6]

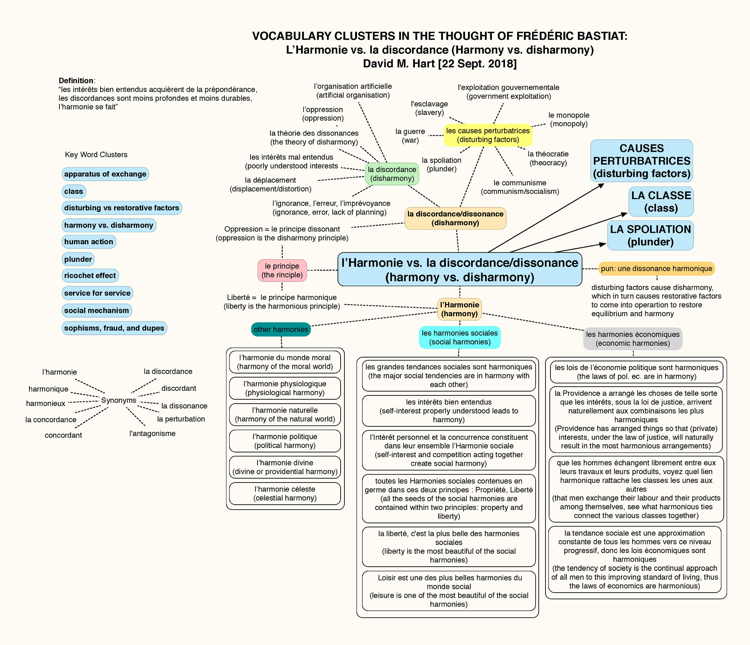

The polarity of the ideas about "harmony" and "disharmony" is central to Bastiat's broader social theory. We will briefly summarise his theory of harmony and disharmony here before discussing it in more detail in the paper below. I have created a number of "concept maps" or what I call "vocabulary clusters" of Bastiat's key ideas to assist me in my editing and translating work - on Class, Disturbing Factors, Harmony and Disharmony, Human Action, and Plunder. [7]

Concerning "harmony", Bastiat believed that various examples of harmony could be seen in both the physical and the "human" worlds. Very broadly he described these harmonies as "providential" but in the case of the human world, the actions of individuals could either promote or destroy this harmony. In the physical world, examples of harmonies he discussed included physiological and celestial harmony which were scientifically observable in the case of the study of the human eye or the motions of the planets around the sun, from which the natural laws of gravitation, for example, could be deduced. On the other hand, human social and economic behavior could result in two types of harmony: social harmony (or harmonies) and economic harmonies. These were also observable by economists and historians (such as in the universal establishment of markets [8] and the tendency of human beings to trade with each other, and other kinds of what Bastiat called "natural organisations"), but they were also discoverable or understandable by a process of internal reflection since all human beings were thinking, choosing, and acting individuals. [9] These observations also led economists and other social theorists to identify the natural laws which governed moral and economic behaviour (individual self-interest, the principle of individual responsibility, the principle of human solidarity, [10] and the various laws of economics). [11] The behavior and institutions which emerged from the operation of these "natural laws" were forms of what he called "natural organisations" or what we would call "spontaneous orders" to use the Hayekian terminology.

Bastiat argued that there were a number of factors which tended to promote social and economic harmony in the long run, such as

- awareness of one's "rightly understood" interests,

- being responsible for one's own actions,

- the individual's natural feeling of solidarity and community with others

- the mutually beneficial nature of voluntary exchanges

- the greater productivity of economic cooperation and division of labour

- the emergence of various "natural organisations" such as "l'appareil de l'échange” (the apparatus of exchange) , consisting of ideas, institutions, and individuals, which allowed mutually beneficial exchanges/trade to take place across time and space [12]

- respect for property rights and the rule of law

- the existence of free trade, limited government, and peace

- the absence of violence, force, and fraud

- the action of various compensating or "restorative factors" which come into play to restore "harmony", peace, and prosperity, when are disturbed by theft, coercion, exploitation, repression, (or what he termed "disturbing factors") [13]

Concerning disharmony, this occurs when natural laws are ignored or violated. Bastiat also identified a number of factors, which he termed "disturbing factors" which caused or perpetuated this disharmony. They included:

- individual ignorance, error, lack of foresight/planning, or willfulness (individuals choosing to steal instead of trading with others)

- the use of force or fraud whether by individuals (what he called “la spoliation extra-légale” (extra-legal plunder) or organized violence and plunder by groups such as the state (or what he called “la spoliation légale” (legal plunder). [14]

- "legal plunder" was organised and systemic and could take the form of

- protectionism and government subsidies (or what he called "displacement" of labour and capital),

- government intervention in the economy,

- various historical forms of plunder such as war, slavery, theocracy ("theocratic plunder"), [15] monopoly, socialism, the modern regulatory state itself (what he termed “le fonctionnarisme” (rule by functionaries, or government bureaucrats)). [16]

He concluded that that harmony is not inherent in human society and thus inevitable, but was a result of an "if-then" argument: if certain conditions are met (economic laws are understood, individuals understand their real interests, property rights of individuals are respected, and there is no or very minimal force and fraud), then a harmonious social and economic order will eventually emerge. Bastiat was optimistic that if these conditions could be met, or if societies could gradually move towards meeting them over time, the problems caused by disharmony could be minimized or perhaps even eliminated in the future, and from this he developed his ideas about progress and the perfectibility of human kind.

Harmony and Disharmony

Concept Map

[See a larger version of this image.]

Introduction: The Harmony of the Providential Plan

The idea of "harmony" and "disharmony" in the social and economic realm was a central component of Bastiat's social theory, in which he referred to some version or other of the words "harmony" or "harmonious" over 500 times in his work. Since Voltaire popularised the work of Newton in France in 1738 [17] it was a commonplace to believe that the universe was a mechanism which was governed by natural laws like that of gravitation which produced "une harmonie céleste" (a celestial harmony) or what he also called "des harmonies de la mécanique céleste" (the harmonies of the celestial machine or mechanism). Closer to Bastiat's own time he was very well aware of the work of the French mathematicians and astronomers Laplace in the first decade of the 19th century and François Arago in the 1840s. [18] From seeing the important role discoverable natural laws played in the harmonious operation of the stars, or "des harmonieuses et simples lois de la Providence" (harmonious and simple laws of Providence), it was only a short mental jump for a deist like Bastiat to seeing them at work in the social realm as well. This is very clearly stated in the concluding paragraph of Bastiat's essay "Natural and Artificial Organisation" (Jan. 1848) [19] where he also makes the important observation that in the social universe the "atoms" which obey these laws are thinking, acting, and choosing individuals: [20]

| Ne condamnons pas ainsi l’humanité avant d’en avoir étudié les lois, les forces, les énergies, les tendances. Depuis qu’il eut reconnu l’attraction, Newton ne prononçait plus le nom de Dieu sans se découvrir. Autant l’intelligence est au-dessus de la matière, autant le monde social est au-dessus de celui qu’admirait Newton, car la mécanique céleste obéit à des lois dont elle n’a pas la conscience. Combien plus-de raison aurons-nous de nous incliner devant la Sagesse éternelle à l’aspect de la mécanique sociale, où vit aussi la pensée universelle, mens agitat molem, mais qui présente de plus ce phénomène extraordinaire que chaque atome est un être animé, pensant, doué de cette énergie merveilleuse, de ce principe de tente moralité, de toute dignité, de tout progrès, attribut exclusif de l’homme, la liberté! | Let us not condemn the human race in this way before having examined its laws, forces, energies, and tendencies. From the time he recognized gravity, Newton no longer pronounced the name of God without taking his hat off. Just as much as “the mind is above matter,” the social world is above the (physical) one admired by Newton, for celestial mechanics obey laws of which it is not aware. How much more reason (then) would we have to bow down before eternal wisdom (and also universal thought) as we contemplate the social mechanism (and see there how) “the mind moves matter” (mens agitat molem). Here is displayed the extraordinary phenomenon that each atom (in this social mechanism) is a living, thinking being, endowed with that marvelous energy, with that source of all morality, of all dignity, of all progress, an attribute which is exclusive to man, namely FREEDOM! |

Bastiat believed that it was part of "le plan providentiel" (the providential plan) that human beings were endowed with certain patterns of behaviour or internal drives (les mobiles) such as the pursuit of self-interest, the avoidance of pain or hardship and the seeking of pleasure or well-being, free will, the ability to plan for the future, and to choose from among alternatives that are presented to them. Or in other words, that mankind had a certain "nature." These were all part of the natural laws which governed human behaviour and made economies operate in the way that they did. His conclusion was that if human beings were allowed to go about their lives freely and in the absence of government or other forms of coercion the result would be a "harmonious society." In a very revealing passage in the essay on "Capital and Rent" (Feb. 1849) he links Newton and Laplace, the cogs and wheels of the social mechanism, the "mobile" or driving force of society, and the providential plan in his paean to the benefits of leisure: [21]

| Mais voyez ! le loisir n’est-il pas un ressort essentiel dans la mécanique sociale ? sans lui, il n’y aurait jamais eu dans le monde ni de Newton, ni de Pascal, ni de Fénelon ; l’humanité ne connaîtrait ni les arts, ni les sciences, ni ces merveilleuses inventions préparées, à l’origine, par des investigations de pure curiosité ; la pensée serait inerte, l’homme ne serait pas perfectible. D’un autre côté, si le loisir ne se pouvait expliquer que par la spoliation et l’oppression, s’il était un bien dont on ne peut jouir qu’injustement et aux dépens d’autrui, il n’y aurait pas de milieu entre ces deux maux : ou l’humanité serait réduite à croupir dans la vie végétative et stationnaire, dans l’ignorance éternelle, par l’absence d’un des rouages de son mécanisme ; ou bien, elle devrait conquérir ce rouage au prix d’une inévitable injustice et offrir de toute nécessité le triste spectacle, sous une forme ou une autre, de l’antique classification des êtres humains en Maîtres et en Esclaves. Je défie qu’on me signale, dans cette hypothèse, une autre alternative. Nous serions réduits à contempler le plan providentiel qui gouverne la société avec le regret de penser qu’il présente une déplorable lacune. Le mobile du progrès y serait oublié, ou, ce qui est pis, ce mobile ne serait autre que l’injustice elle-même. — Mais non, Dieu n’a pas laissé une telle lacune dans son œuvre de prédilection. Gardons-nous de méconnaître sa sagesse et sa puissance ; que ceux dont les méditations incomplètes ne peuvent expliquer la légitimité du loisir, imitent du moins cet astronome qui disait : À tel point du ciel, il doit exister une planète qu’on finira par découvrir, car sans elle le monde céleste n’est pas harmonie, mais discordance. | But look, is not leisure an essential spring in the social mechanism? Without it there would never have been any Newtons, Pascals, or Fénélons in the world; the human race would have no knowledge of art, the sciences, nor any of the marvelous inventions originally made by investigation out of pure curiosity. Thought would be inert, and man would not have the ability to advance. On the other hand, if leisure could be explained only as a function of plunder and oppression, if it were a benefit that could be enjoyed only unjustly and at the expense of others, there would be no middle way between two evils: either the human race would be reduced to squatting in a vegetative and immobile life, in eternal ignorance because one of the cog wheels in its mechanism was missing, or it would have to conquer this cog wheel at the price of inevitable injustice and be obliged to offer the world the sorry sight in one form or another of the division of human beings into masters and slaves as in classical times. I challenge anyone to suggest an alternative outcome within the terms of this analysis. We would be reduced to contemplating the providential plan that orders society with the regretful thought that something is very sadly missing. The driving force of progress would either have been forgotten, or what is worse, this driving force would constitute nothing other than injustice itself. But no, God has not left out an element like this from his creation. Let us be careful to acknowledge fully his wisdom and power. Let those whose imperfect thinking fails to explain the legitimacy of leisure at least echo that astronomer who said: “At a certain point in the heavens there has to be a planet which we will one day discover, for without it the celestial world is not harmony but disharmony.” |

The Harmony of Natural Laws

In addition to the astronomical and Providential sources of his thinking about harmony there is the strong tradition within French political economy of natural law both as a justification for the ownership of property and for the freedom to produce and trade with others. This notion of natural law was more than a moral or legal justification for certain practices and institutions but also a explanation of how those practices and institutions arose in the course of history and how they operated in the present. We can trace ideas about the existence of natural laws within economics in France back to the Physiocrats such as François Quesnay, the work of Jean-Baptiste Say, and many of the Paris school of economists [22] with whom Bastiat worked, especially Gustave de Molinari. The latter developed the most complete and elaborate theory of the natural laws which governed the economic realm in his popular book Les Soirées de la rue Saint-Lazare which had as its subtitle the very revealing sentence "entretiens sur les lois économiques et défense de la propriété" (discussions about economic laws and the defence of property) [23] and then in later works such as Les Lois naturelles de l'économie politique (1887) in which he summarised his life's work on this topic. [24] Molinari believed that there were at least six major "natural laws of economics" on which he elaborated at some length over many decades. [25] Bastiat belonged in this tradition with his ideas about the economic natural laws such as the law of supply and demand and Malthusian population growth.

Bastiat may well have also been influenced by Scottish thinkers like Adam Ferguson who understood how complex social and economic structures might emerge as "the result of human action, but not the execution of any human design" simply by allowing the "harmonious laws" which governed society to come into play. [26] Bastiat did not quote Ferguson directly but Ferguson was well known to the Paris economists as his book on The History of Civil Society was translated into French shortly after it appeared and his work was praised in an entry on him in the JDE. [27] It is not hard to hear echoes of Ferguson's ideas about spontaneous and harmonious orders in Bastiat's well known discussion of the feeding of Paris: [28]

| En entrant dans Paris, que je suis venu visiter, je me disais : Il y a là un million d’êtres humains qui mourraient tous en peu de jours si des approvisionnements de toute nature n’affluaient vers cette vaste métropole. L’imagination s’effraie quand elle veut apprécier l’immense multiplicité d’objets qui doivent entrer demain par ses barrières, sous peine que la vie de ses habitants ne s’éteigne dans les convulsions de la famine, de l’émeute et du pillage. Et cependant tous dorment en ce moment sans que leur paisible sommeil soit troublé un seul instant par l’idée d’une aussi effroyable perspective. D’un autre côté, quatre-vingts départements ont travaillé aujourd’hui, sans se concerter, sans s’entendre, à l’approvisionnement de Paris. Comment chaque jour amène-t-il ce qu’il faut, rien de plus, rien de moins, sur ce gigantesque marché ? Quelle est donc l’ingénieuse et secrète puissance qui préside à l’étonnante régularité de mouvements si compliqués, régularité en laquelle chacun a une foi si insouciante, quoiqu’il y aille du bien-être et de la vie ? Cette puissance, c’est un principe absolu, le principe de la liberté des transactions. Nous avons foi en cette lumière intime que la Providence a placée au cœur de tous les hommes, à qui elle a confié la conservation et l’amélioration indéfinie de notre espèce, l’intérêt, puisqu’il faut l’appeler par son nom, si actif, si vigilant, si prévoyant, quand il est libre dans son action. Où en seriez-vous, habitants de Paris, si un ministre s’avisait de substituer à cette puissance les combinaisons de son génie, quelque supérieur qu’on le suppose ? s’il imaginait de soumettre à sa direction suprême ce prodigieux mécanisme, d’en réunir tous les ressorts en ses mains, de décider par qui, où, comment, à quelles conditions chaque chose doit être produite, transportée, échangée et consommée ? | On entering Paris, which I had come to visit, I said to myself: Here there are a million human beings who would all die in a few days if supplies of all sorts did not flood into this huge metropolis. The mind boggles when it tries to assess the huge variety of objects that have to enter through its gates tomorrow if the lives of its inhabitants are not to be snuffed out in convulsions of famine, uprisings, and pillage. And in the meantime everyone is asleep, without their peaceful slumber being troubled for an instant by the thought of such a frightful prospect. On the other hand, eighty departments have worked today without being in concert and without agreement to supply Paris. How does it happen that every day what is needed and no more or less is brought to this gigantic market? What is thus the ingenious and secret power that presides over the astonishing regularity of such complicated movements, a regularity in which everyone has such blind faith, although well-being and life depend on it? This power is an absolute principle, the principle of free commerce. We have faith in this intimate light that Providence has placed in the hearts of all men to whom it has entrusted the indefinite preservation and progress of our species, self-interest, for we must give it its name, that is so active, vigilant, and farsighted when it is free to act. Where would you be, you inhabitants of Paris, if a minister took it into his head to substitute the arrangements he had thought up, however superior they are thought to be, for this power? Or if he took it into his head to subject this stupendous mechanism to his supreme management, to gather together all these economic activities in his own hands, to decide by whom, how, or under what conditions each object has to be produced, transported, traded and consumed? |

As is clear from this passage and the one above on leisure, Bastiat believed that Providence (sometimes God) had created an ordered and harmonious world which operated according to discoverable natural laws, such as gravitation, and then stepped back to let it operate on its own. The human equivalent of gravitation was for Bastiat "le moteur social" (the social driving force) of self-interest. [29] There is no evidence to think that Bastiat thought Providence or God had intervened in human life at any time since then. The world which had been created was more of a stately Newtonian clockwork-like universe (or mechanism) with regular behaviour which could be studied and from which "natural laws" governing its operation could be discovered by social theorists like economists. One might term this a theory of "harmonious design" rather than of "intelligent design." From our perspective today, this view of a rather static and not dynamic universe is rather naive as the universe is known to be a violent and "disharmonious" place where stars are torn from their orbits and ejected out of their galaxy, stars collapse and then explode, that some massive stars form black holes out of which nothing can escape, space is filled with intense radiation which kills all life forms, and planets with life can be pounded with meteors which wipe them out periodically. But from Bastiat's perspective in mid-nineteenth century France the Newtonian and Laplacian theory of celestial order and harmony seemed a logical and scientifically advanced one.

Harmonies Social and Economic

Of the over 500 uses of the word "harmony" and related terms in Bastiat's writings we can identify the following key expressions. In addition to many general references to things being "en harmonie" (in harmony) with each other, Bastiat used the words "harmonique," or "harmonieux" or "harmonieuse" (harmonious) in reference to orders, organisations, associations, human development, individual interests, and laws being "harmonious." Most notably, he used the expressions "l'harmonie sociale" or "les harmonies sociales" (social harmony or harmonies), and "les harmonies économique" (economic harmonies always in the plural) to describe the social and economic theory he was working on before his untimely and premature death.

Concerning the word "harmonique" (harmonious) his first two uses of the word occur in the very important pair of articles which he wrote on the eve of his arrival in Paris in May 1845, which show the advanced state of his thinking on this topic before he came into contact with the Paris economists. The first use can be found in his unpublished review of Dunoyer's book De la liberté du travail probably in January or February 1845 where he says: [30]

| Il (le socialisme) consiste à rejeter du gouvernement du monde moral tout dessein providentiel; à supposer que du jeu des organes sociaux, de l’action et de la réaction libre des intérêts humains, ne résulte pas une organisation merveilleuse, harmonique, et progressive … | It (socialism) consists in rejecting any providential designs in the governance of the moral world; in supposing that a marvelous, harmonious, and progressive order cannot result from the to and fro of social groups and the free action and reaction of human interests … |

His second use comes from an early article which is a kind of show case of Bastiat's orignal and provocative ideas which he brought with him to Paris, namely his critique of the poet and politician Lamartine for having strayed from the straight and narrow path of free market orthodoxy. Here he is chastising Lamartine for advocating coercive, state charity instead of a completely free and voluntary system to aid needy workers: [31]

| Ensuite, l’économie politique distingue la charité volontaire de la charité légale ou forcée. L’une, par cela même qu’elle est volontaire, se rattache au principe de la liberté et entre comme élément harmonique dans le jeu des lois sociales ; l’autre, parce qu’elle est forcée, appartient aux écoles qui ont adopté la doctrine de la contrainte, et inflige au corps social des maux inévitables. | Next, political economy distinguishes between voluntary charity and state or compulsory charity. The first, for the very reason that it is voluntary, relates to the principles of freedom and is included as an element of harmony in the interplay of social laws; the other, because it is compulsory, belongs to the schools of thought that have adopted the doctrine of coercion and inflict inevitable harm on the social body. |

Other important uses of "harmonique" occur often with respect to "les lois harmoniques" (harmonious laws) or "les lois naturelles harmoniques" (harmonious natural laws) as in his opening "Address to the Youth of France" in EH1 (probably written late 1849) where he defines liberty as "la liberté ou le libre jeu des lois harmoniques, que Dieu a préparées pour le développement et le progrès de l'humanité" (liberty, or the free play of the harmonious laws which God has prepared for the development and progress of humanity), [32] or the following: [33]

| Enfin j’appellerai l’attention du lecteur sur les obstacles artificiels que rencontre le développement pacifique, régulier et progressif des sociétés humaines. De ces deux idées : Lois naturelles harmoniques, causes artificielles perturbatrices, se déduira la solution du Problème social. | Finally, I will draw the reader’s attention to the artificial obstacles that the peaceful, regular, and progressive development of human societies encounter. From these two concepts, harmonious natural laws and artificial disturbing factors (causes artificielles perturbatrices), the resolution of the social problem will be deduced. |

However, Bastiat's two most important concepts relating to harmony are "les harmonies sociales" (social harmonies) and "les harmonies économiques" (economic harmonies) [34] and his affiliated ideas of "discordance" and "dissonance" (disharmony and dissonance) which he often paired with them. As early as June 1845, the month after he arrived in Paris, Bastiat was planning a large work with the title of "Social Harmonies" as he explained to his close friend and neighbour Félix Coudroy back in Mugron: [35]

| Si mon petit traité, Sophismes économiques, réussit, nous pourrions le faire suivre d’un autre intitulé : Harmonies sociales. Il aurait la plus grande utilité, parce qu’il satisferait le penchant de notre époque à rechercher des organisations, des harmonies artificielles, en lui montrant la beauté, l’ordre et le principe progressif dans les harmonies naturelles et providentielles. | If my small treatise, Economic Sophisms, is a success (it was published in January 1846), we might follow it with another entitled Social Harmonies. It would be of great use because it would satisfy the tendency of our epoch to look for (socialist) organizations and artificial harmonies by showing it the beauty, order, and progressive principle in natural and providential harmonies. |

Details about his planned book on "social harmonies" can be gleaned from scattered remarks in letters he wrote to his friends and supporters, and occasionally in some of his own writings. He first began work on the project in the fall of 1847 when he gave some lectures at the Taranne Hall in Paris to some Law and Medical students, using the first volume of his Economic Sophisms as the text book. In another letter to Félix written in August 1847 he described his plans for the course of lectures to present his ideas on "l'harmonie des lois sociales" (the harmony of social laws) and where he suggests he and Félix had been discussing this for some time: [36]

| (A) partir de novembre prochain, je ferai à cette jeunesse un cours, non d’économie politique pure, mais d’économie sociale, en prenant ce mot dans l’acception que nous lui donnons, Harmonie des lois sociales. | (F)rom next November I will be giving a course (of lectures) to these young people (at the School of Law), not on pure political economy but on social economics, using this in the meaning we have given it, the “Harmony of Social Laws.” |

Sometime during the fall when his lectures were underway he wrote an ironic letter to himself in the form of a "Draft Preface" to the book he hoped to write. In this letter Bastiat chastises himself for having been too preoccupied with only one aspect of freedom, namely free trade or what he disparagingly called this "l'uniforme croûte de pain sec" (single crust of dry bread as food), and having neglected the broader social picture. To rectify this he wanted to apply the ideas of J.B. Say, Charles Comte, and Charles Dunoyer, to a study of "toutes les libertés" (all forms of freedom) in a very ambitious research project in liberal social theory. [37]

In July 1847 in a letter to Richard Cobden, to whom he often confided his private thoughts and hopes as he felt many of his Parisian colleagues did not fully understand or appreciate what he was attempting to do, he stated that his book on "la vraie théorie sociale" (real social theory) would contain 12 chapters on some very broad topics: [38]

| ce que je considère comme la vraie théorie sociale, sous ces douze chapitres : Besoins, production, propriété, concurrence, population, liberté, égalité, responsabilité, solidarité, fraternité, unité, rôle de l’opinion publique | what I consider to be the true/real social theory in the following twelve chapters: “Needs,” “Production,” “Property,” “Competition,” “Population,” “Liberty,” “Equality,” “Responsibility,” “Solidarity,” “Fraternity,” “Unity,” and “The Role of Public Opinion” … |

At the same time as he was giving these lectures at the School of Law in late 1847 he was preparing the second volume of his Economic Sophisms which would appear in January 1848. The two opening chapters which were undated but probably written at the end of 1847, dealt with the nature of plunder. Bastiat's friend and editor Paillottet reveals in a footnote that Bastiat also planned to write another volume on the history of plunder.

In their "Foreword" to the expanded second edition of EH which they published 6 months after Bastiat's death, Fontenay and Paillottet concluded that Bastiat was planning to write "at least" three volumes which would be made up of a volume on "Social Harmonies," one on "Economic Harmonies," and one on plunder which might have been fittingly entitled "Social and Economic Disharmonies." [39]

Bastiat himself seems to have been torn over how he should approach writing the books given the very severe time constraints placed upon him by his parliamentary duties and his worsening health. In an undated note quoted by Fontenay and Paillottet Bastiat discusses the problem he faced in organising the project: [40]

| J’avais d’abord pensé à commencer par l’exposition des Harmonies Économiques, et par conséquent à ne traiter que des sujets purement économiques: Valeur, Propriété, Richesse, Concurrence, Salaire, Population, Monnaie , Crédit, etc. — Plus tard, si j’en avais eu le temps et la force, j’aurais appelé l’attention du lecteur sur un sujet plus vaste: les Harmonies sociales. C’est là que j’aurais parlé de la Constitution humaine, du Moteur social, de la Responsabilité, de la Solidarité, etc.. L’œuvre ainsi conçue était commencée, quand je me suis aperçu qu’il était mieux de fondre ensemble que de séparer ces deux ordres de considérations. Mais alors la logique voulait que l’étude de l’homme précédât les recherches économiques. Il n’était plus temps ; puisse-je réparer ce défaut dans une autre édition! … | I had at first thought of beginning with an exposition of the Economic Harmonies, and therefore only dealing with purely economic subjects, such as value, property, wealth, competition, wages, population, money, credit, etc. Later, if I had had the time and the energy, I would have brought to the attention of the reader a much bigger subject (un sujet plus vaste), namely the Social Harmonies. There I would have spoken about human nature (la Constitution humaine), the driving force of society, (individual) responsibility, (social) solidarity, etc. I had commenced work on the project conceived in this way when I realised that it would have been better to merge them together rather than treating these two different kinds of matters separately. But then logic demanded that the study of man should precede research into economic matters. There no longer enough time; perhaps I can fix this error in a future edition! |

Another version from Ronce (in CW4): [41]

| J’avais d’abord pensé à commencer par l’exposition des Harmonies Économiques, et par conséquent à ne traiter que des sujets purement économiques: Valeur, Propriété, Richesse, Concurrence, Salaire, Population, Monnaie , Crédit, etc. — Plus tard, si j’en avais eu le temps et la force, j’aurais appelé l’attention du lecteur sur un sujet plus vaste: les Harmonies sociales. C’est là que j’aurais parlé de la Constitution humaine, du Moteur social, de la Responsabilité, de la Solidarité, etc.. L’œuvre ainsi conçue était commencée, quand je me suis aperçu qu’il était mieux de fondre ensemble que de séparer ces deux ordres de considérations. Mais alors la logique voulait que l’étude de l’homme précédât les recherches économiques. Il n’était plus temps ; puissé-je réparer ce défaut dans une autre édition! .. | I had originally thought to begin with an exposition of the Economic Harmonies and as a result to treat only purely economic subjects, such as value, property, wealth, competition, wages, population, money, credit, etc. Later, if I had had the time and the energy, I would have called the reader’s attention to a much larger subject, the Social Harmonies. It is here that I would have talked about human nature, the driving force of society, individual responsibility, social solidarity, etc. … Having conceived the project in this fashion I had commenced work on it when I realized that it would have been better to merge rather than to separate these two different kinds of approaches. But then logic demands that the study of mankind should precede that of economics. However, there was not enough time: how I wish I could correct this error in another edition!… |

It would appear that he planned to write a very large volume on "social harmonies" to explain the big picture and a companion volume to explain the nature, origins, and history of the "social disharmonies" which disturbed or disrupted those harmonies. But as his health was failing and time was running out he realised he had to limit himself to an important subset of this larger project and this eventually became the "economic harmonies." He only managed to finish and publish in his lifetime the first volume of EH which he wrote over the summer of 1849 and which appeared in print in early 1850. His friends cobbled together what unfinished papers and chapters they could find in his effects and published "vol. 2" (EH2) in July 1851 six months after Bastiat's death.

An interesting question to ask is how much of this ambitious project had Bastiat conceived while he was still living in Mugron before he came to Paris in May 1845 and how much of it evolved as he became involved in the free trade movement and the circle of economists who were part of the Guillaumin network. Perhaps the idea had been germinating in his mind over the previous 20 years of intense reading of economics in his home town of Mugron?

What did he mean by "social harmonies"?

One of the best examples of what Bastiat meant by "social harmony" (singular) can be found in a passage in the new introduction to his essay "On Competition" which was originally published in May 1846 in the JDE which he revised over the summer of 1849 and became Chapter X of EH1. He takes the example of what he calls two "indomitable forces," individual self-interest and competition which, individually could cause conflict and social disharmony but, when combined together in a free society, create "Social Harmony." [42]

| … Dieu, qui a mis dans l’individualité l’intérêt personnel qui, comme un aimant, attire toujours tout à lui, Dieu, dis-je, a placé aussi, au sein de l’ordre social, un autre ressort auquel il a confié le soin de conserver à ses bienfaits leur destination primitive : la gratuité, la communauté. Ce ressort, c’est la Concurrence. | … God, who has placed in individuals the self-interest that, like a magnet, constantly draws everything to itself, this God, I say, has also placed within the social order another mainspring (ressort) to which he has entrusted the care of maintaining his gifts such that they conform to their original objective: to be freely available (la gratuité) and common to all (la communauté). This mainspring is Competition. |

| Ainsi l’Intérêt personnel est cette indomptable force individualiste qui nous fait chercher le progrès, qui nous le fait découvrir, qui nous y pousse l’aiguillon dans le flanc, mais qui nous porte aussi à le monopoliser. La Concurrence est cette force humanitaire non moins indomptable qui arrache le progrès, à mesure qu’il se réalise, des mains de l’individualité, pour en faire l’héritage commun de la grande famille humaine. Ces deux forces qu’on peut critiquer, quand on les considère isolément, constituent dans leur ensemble, par le jeu de leurs combinaisons, l’Harmonie sociale. | Thus, Self-interest is this indomitable individual force that drives us to seek progress, makes us achieve it, and spurs us on, but which also makes us inclined to monopolize it. Competition is the no less indomitable humanitarian force that snatches progress as it is achieved from the hands of individuals in order to make it part of the common heritage of the great human family. These two forces, which can be criticized when considered separately, constitute Social Harmony when taken together because of their interplay when (acting) in combination. |

In another passage in a chapter on "Producers and Consumers" which appeared in EH2 Bastiat describes what he calls "la loi essentielle de l'harmonie sociale" (the essential law of social harmony), namely that man is perfectible, that the standard of living will continue to improve over time, and that more and more people will approach this increasingly common, higher standard of living: [43]

| Si le niveau de l’humanité ne s’élève pas sans cesse, l’homme n’est pas perfectible. | If the standard of living (niveau) of the human race does not increase constantly, man is not perfectible. |

| Si la tendance sociale n’est pas une approximation constante de tous les hommes vers ce niveau progressif, les lois économiques ne sont pas harmoniques. | If the tendency of society is not the continual approach of all men to this improving standard of living, the laws of economics are not harmonious. |

| Or comment le niveau humain peut-il s’élever si chaque quantité donnée de travail ne donne pas une proportion toujours croissante de satisfactions, phénomène qui ne peut s’expliquer que par la transformation de l’utilité onéreuse en utilité gratuite ? | Well, how can the standard of living of the human race rise if each given quantity of labor does not provide an ever-increasing proportion of satisfaction, a phenomenon that can be explained only by the transformation of cost-bearing/onerous utility into free/gratuitous utility? |

| Et, d’un autre côté, comment cette utilité, devenue gratuite, rapprocherait-elle tous les hommes d’un commun niveau, si en même temps elle ne devenait commune ? | And on the other hand, how would the utility that has become free/gratuitous bring everyone closer to the same standard of living if it did not at the same time become common to all? |

| Voilà donc la loi essentielle de l’harmonie sociale. | This is therefore the essential law of social harmony. |

He makes a similar comment in a passage in the article on "Population" in the JDE (Oct. 1846) where he equates "the social harmonies" with equal access for all people to the benefits of progress and a rising standard of living: [44]

| La théorie que nous venons d’exposer succinctement conduit à ce résultat pratique, que les meilleures formes de la philanthropie, les meilleures institutions sociales sont celles qui, agissant dans le sens du plan providentiel tel que les harmonies sociales nous le révèlent, à savoir, l’égalité dans le progrès, font descendre dans toutes les couches de l’humanité, et spécialement dans la dernière, la connaissance, la raison, la moralité, la prévoyance. | The theory that we have just set out briefly leads to the practical result that the best forms of philanthropy and the best social institutions are those that, when they operate in line with the Providential plan as revealed to us by the social harmonies, that is to say, equality in progress (l’égalité dans le progrès = equal progress for all), spread knowledge, reason, morality, and foresight throughout all of the social strata of humanity, especially the lowest. |

What did he mean by "economic harmonies"?

By "economic harmonies" Bastiat meant that subset of "harmonies" which were part of the broader framework of "social harmonies" discussed above. These would include what he described as "purely economic subjects, such as value, property, wealth, competition, wages, population, money, credit." They were also meant as a companion volume to his Economic Sophisms which he described in a letter to Cobden in June 1846 as "un petit livre intitulé : Harmonies économiques. Il ferait le pendant de l'autre; le premier démolit, le second édifierait" (a small book entitled Economic Harmonies. It will make a pair with the other; the first knocks down and the second would build up). [45] He made a similar comment to Cobden a year later where he described the book on Economic Harmonies as providing "le point de vue positif” (the positive point of view) and the Economic Sophisms "le point de vue négatif” (the negative point of view). [46]

He offered another explanation of his purpose in the conclusion to Part I of the article on "Economic Harmonies" which appeared in the JDE in Sept. 1848. [47] He wanted to demonstrate to others the "sublime and reassuring harmonies in the play of natural laws governing society", to use this "one true, simple, and fruitful notion … to resolve some of the problems that still arouse controversy: competition, mechanization, foreign trade, luxury, capital, rent," and to "show the relationships, or rather the harmonies, of political economy with the other moral and social sciences."

| Qu’ils me pardonnent; que ce soit la vérité elle-même qui me presse ou que je sois dupe d’une illusion, toujours est-il que je sens le besoin de concentrer dans un faisceau des idées que je n’ai pu faire accepter jusqu’ici pour les avoir présentées éparses et par lambeaux. Il me semble que j’aperçois dans le jeu des lois naturelles de la société de sublimes et consolantes harmonies. Ce que je vois ou crois voir, ne dois-je pas essayer de le montrer à d’autres, afin de rallier ainsi autour d’une pensée de concorde et de fraternité bien des intelligences égarées, bien des cœurs aigris? Si, quand le vaisseau adoré de la patrie est battu parla tempête, je parais m’éloigner quelquefois, pour me recueillir, du poste auquel j’ai été appelé, c’est que mes faibles mains sont inutiles à la manœuvre. Est-ce d’ailleurs trahir mon mandat que de réfléchir sur les causes de la tempête elle-même, et m’efforcer d’agir sur ces causes? Et puis, ce que je ne ferais pas aujourd’hui, qui sait s’il me serait donné de le faire demain? | I hope they will forgive me! Whether it is truth itself that harries me or just that I am the victim of delusion, I still feel the need to concentrate on a range of ideas for which I have not been able to gain acceptance up to now because I have presented them in dribs and drabs. I think that I discern sublime and reassuring harmonies in the play of natural laws governing society. Should I not try to show others what I see or think I see, in rallying a great many mistaken minds and embittered hearts around a way of thinking based upon concord and fraternity? If I appear to drift away from the post to which I have been called in order to gather my thoughts, at a time when the beloved ship of State is buffeted by storms, it is because my weak hands cannot help hold the tiller. Besides, am I betraying my mission when I reflect on the causes of the storm itself and endeavor to act on these causes? What is more, if I do not do this now, who knows whether I will have the opportunity to do it later? |

| Je commencerai par établir quelques notions économiques. M’aidant des travaux de mes devanciers, je m’efforcerai de résumer la Science dans un principe vrai, simple et fécond, qu’elle entrevit dès l’origine, dont elle s’est constamment approchée et dont peut-être le moment est venu de fixer la formule. Ensuite, à la clarté de ce flambeau, j’essayerai de résoudre quelques-uns des problèmes encore controversés, concurrence, machines, commerce extérieur, luxe, capital, rente, etc. Enfin, je montrerai les relations ou plutôt les harmonies de l’économie politique avec les autres sciences morales et sociales, en jetant un coup d’œil sur les graves sujets exprimés par ces mots : Intérêt personnel, Propriété, Liberté, Responsabilité, Solidarité, Egalité, Fraternité, Unité. | I will start by setting out a few economic notions. With the help of the work carried out by my predecessors, I will endeavor to epitomize this mode of explanation in one true, simple, and fruitful notion, one that it foresaw from the outset and to which it has constantly drawn near, with the time perhaps having come to establish its wording definitively. Then by this beacon, I will try to resolve some of the problems that still arouse controversy: competition, mechanization, foreign trade, luxury, capital, rent, etc. I will show the relationships, or rather the harmonies, of political economy with the other moral and social sciences by casting a glance on the serious matters encapsulated in the following words: Self-Interest, Property, Liberty, Responsibility, Solidarity, Equality, Fraternity, and Unity. |

And there is his moving last ditch attempt to explain what he wanted to do in the Conclusion to EH1 when he must have known in his heart that he would never live to see the project completed. In this passage he ties together several of his key ideas on harmony and disharmony, property and plunder, freedom and oppression: [48]

| Nous avons vu toutes les Harmonies sociales contenues en germe dans ces deux principes : Propriété, Liberté. — Nous verrons que toutes les dissonances sociales ne sont que le développement de ces deux autres principes antagoniques aux premiers : Spoliation, Oppression. | We have seen the germs of all the Social Harmonies encapsulated in the following two principles: PROPERTY and FREEDOM. We will see that all social disharmony (toutes les dissonances sociales) is merely the development of two other principles that conflict with the first: PLUNDER and OPPRESSION. |

| Et même, les mots Propriété, Liberté n’expriment que deux aspects de la même idée. Au point de vue économique, la liberté se rapporte à l’acte de produire, la Propriété aux produits. — Et puisque la Valeur a sa raison d’être dans l’acte humain, on peut dire que la liberté implique et comprend la Propriété. — Il en est de même de l’Oppression à l’égard de la Spoliation. | And likewise the words Property and Freedom express only two aspects of the same idea. From the point of view of economics, Freedom relates to the act of producing and Property to the products. And since Value owes its very reason for existing to human activity, it may be said that Freedom implies and encompasses Property. This is also true of Oppression with regard to Plunder. |

| Liberté ! voilà, en définitive, le principe harmonique. Oppression ! voilà le principe dissonant ; la lutte de ces deux puissances remplit les annales du genre humain. | Freedom! This is the definitive principle of harmony (le principe harmonique). Oppression! This is the principle of disharmony (le principe dissonant), and the struggle between these two forces fills the annals of the human race. |

We have attempted to reconstruct what Bastiat's multi-volume magnum opus on "Harmonies and Disharmonies" might have looked like had he lived long enough to complete it.

Bastiat's Theory of Disharmony

As a counterpoint to his theory of harmony Bastiat also had a theory of its opposite, namely "disharmony." He used several words to describe this, such as "la discordance" (disharmony), "la dissonance" (dissonance, or discord), "la perturbation" (disturbance, disruption), and "l'antagonisme" (antagonism, or opposition). He often paired "l'harmonie" with either "la discordance" or "la dissonance" as its opposite. He also paired "la perturbation" with its opposite, as in the expressions "les forces perturbatrices" (disturbing forces) and "les forces réparatrices" (restorative or repairing forces). [49]

The bulk of the references to disharmony occur in his book Economic Harmonies for the obvious reason that he was able to contrast it with the main topic of his interest. However, there were a few references before he began work in earnest on his book, such as this one from the the first article published in the JDE in October 1844 on “On the Influence of French and English Tariffs on the Future of the Two People”, where it is very clear from the context that what caused disharmony was the use of violence to enforce a protectionist trade policy: [50]

| Si la Balance du commerce est vraie en théorie ; si, dans l’échange international, un peuple perd nécessairement ce que l’autre gagne ; s’ils s’enrichissent aux dépens les uns des autres, si le bénéfice de chacun est l’excédant de ses ventes sur ses achats, je comprends qu’ils s’efforcent tous à la fois de mettre de leur côté la bonne chance, l’exportation ; je conçois leur ardente rivalité, je m’explique les guerres de débouchés. Prohiber par la force le produit étranger, imposer à l’étranger par la force le produit national, c’est la politique qui découle logiquement du principe. Il y a plus, le bien-être des nations étant à ce prix, et l’homme étant invinciblement poussé à rechercher le bien-être, on peut gémir de ce qu’il a plu à la Providence de faire entrer dans le plan de la création deux lois discordantes qui se heurtent avec tant de violence ; mais on ne saurait raisonnablement reprocher au fort d’obéir à ces lois en opprimant le faible, puisque l’oppression, dans cette hypothèse, est de droit divin et qu’il est contre nature, impossible, contradictoire que ce soit le faible qui opprime le fort. | If the balance of trade is true in theory, if in international trade one nation necessarily loses what another gains, if nations become wealthy at each others’ expense, if the profits of each lie in an excess of sales over purchases, I understand that they all endeavor at the same time to procure good luck or exports for themselves, I understand their ardent rivalry and find an explanation for the war for markets. To prohibit foreign products by force and impose on foreigners our products by force is a policy that is a logical result of this principle. What is more, since the well-being of nations is at this price and man is ineluctably impelled to seek well-being, we may complain that Providence was happy to introduce into the plan of creation two disharmonious laws (deux lois discordantes) that conflict so violently with each other. However, we cannot reasonably criticise the strong for obeying these laws by oppressing the weak, since oppression, in this scenario, is the result of divine right and it would be unnatural, impossible, and contradictory for the weak to oppress the strong. |

This was repeated in a very similar fashion five years later in his opening address "To the Youth of France" in HE where he states that a lack of harmony in the world clearly shows a lack of liberty and justice due to the actions of oppressors and plunders: [51]

| Si les lois providentielles sont harmoniques, c’est quand elles agissent librement, sans quoi elles ne seraient pas harmoniques par elles-mêmes. Lors donc que nous remarquons un défaut d’harmonie dans le monde, il ne peut correspondre qu’à un défaut de liberté, à une justice absente. Oppresseurs, spoliateurs, contempteurs de la justice, vous ne pouvez donc entrer dans l’harmonie universelle, puisque c’est vous qui la troublez. | If the laws of Providence are harmonious, it is when they act freely, otherwise they would not be harmonious of themselves. Therefore, when we note a lack of harmony in the world it can only be the result of a lack of freedom or of justice that is absent. Oppressors, plunderers, those who hold justice in contempt, you can never be part of universal harmony since you are the people who are upsetting it. |

An early explicit pairing of harmony and disharmony can be found in his "Second Letter to Lamartine" (JDE, Oct. 1846) in which he again criticises Lamartine for straying from the free trade fold and supporting price controls on food during emergencies: [52]

| C’est pour moi une bien douce consolation que la doctrine de la liberté ne me montre qu’harmonie entre ces divers intérêts ; et, avec votre âme, vous devez être bien malheureux, puisque vous ne voyez entre eux qu’une irrémédiable dissonance. | I find it very comforting that the doctrine of freedom reveals to me only harmony among these various interests and, with your soul, you must be very unhappy, since you see in them just an unavoidable disharmony (dissonance). |

Fundamental to Bastiat's view of harmony of the free market was that the interests of individuals were not inherently "disharmonious" or in conflict with each. His proviso was that these interests had to be "bien compris" (rightly understood) or "légitimes" (legitimate), otherwise they would clash and produce disharmony. In his pamphlet "Baccalaureate and Socialism" (early 1850) he stated: [53]

| Les intérêts des hommes, bien compris, sont harmoniques, et la lumière qui les leur fait comprendre brille d’un éclat toujours plus vif. Donc les efforts individuels et collectifs, l’expérience, les tâtonnements, les déceptions même, la concurrence, en un mot, la Liberté — font graviter les hommes vers cette Unité, qui est l’expression des lois de leur nature, et la réalisation du bien général. | Properly understood, the interests of men are harmonious and the light that enables men to understand them shines with an ever more brilliant glow. Therefore, individual and collective efforts, experience, stumbling (trial and error), and even deceptions, competition—in a word, freedom—make men gravitate toward this unity (of interests) that is an expression of the laws of their nature and the achievement of the general good. |

By "rightly understood interests," Bastiat realised that individuals were fallible and would make mistakes, but because they were thinking beings capable of planning and choosing between alternatives, they were able to correct their mistakes, better understand what their true interests were, and act accordingly. Thus, the disharmony caused by poor decisions was self-correcting.

In the Introduction to EH1, his address "To the Youth of France," (written late 1849) he asserts that "tous les intérêts légitimes sont harmoniques" (all legitimate interests are harmonious) and that this idea was "l'idée dominante de cet écrit" (the dominant idea of this work). By "legitimate interests," Bastiat meant any activity which was undertaken without coercion or fraud, which was engaged in voluntarily by both parties to an exchange, and where the property rights of each individual were respected. Interests which were pursued by means of force or fraud were illegitimate in his view and caused considerable disruption and disharmony to the social order. However, he realised that this notion was rejected by the socialist critics of his day who argued the opposite, that men's interests were "naturally antagonistic" and hence a cause of disharmony. This lead to a stark choice for efforts to solve "le problème social" (the social problem or question), if interests were naturally harmonious then individual liberty and the free market could be trusted to solve it; if interests were naturally antagonistic or disharmonious, then force had to used to prevent further antagonism and disharmony: [54]

| Non, certes ; mais je voudrais vous mettre sur la voie de cette vérité : Tous les intérêts légitimes sont harmoniques. C’est l’idée dominante de cet écrit, et il est impossible d’en méconnaitre l’importance. … | Certainly not, but I would like to set you on the path to this truth: All legitimate interests are harmonious. This is the dominant idea in this book, and it is impossible not to recognize its importance. … |

| Or cette solution (to “le problème social”), vous le comprendrez aisément, doit être toute différente selon que les intérêts sont naturellement harmoniques ou antagoniques. | Well, this solution (to the social problem), as you will easily understand, has to be very different, depending on whether interests are in harmony (harmoniques) or in conflict (antagoniques). |

| Dans le premier cas, il faut la demander à la Liberté ; dans le second, à la Contrainte. Dans l’un, il suffit de ne pas contrarier ; dans l’autre, il faut nécessairement contrarier. | In the first case, we must call for Freedom, in the second, for Coercion (contrainte). In the first case, it is enough not to interfere with other people (contrarier), in the other, you have of necessity to interfere with other people. |

| Mais la Liberté n'a qu'une forme. Quand on est bien convaincu que chacune des molécules qui composent un liquide porte en elle-même la force d'où résulte le niveau général, on en conclut qu'il n'y a pas de moyen plus simple et plus sûr pour obtenir ce niveau que de ne pas s'en mêler. Tous ceux donc qui adopteront ce point de départ : Les intérêts sont harmoniques, seront aussi d'accord sur la solution pratique du problème social : s'abstenir de contrarier et de déplacer les intérêts. | But Freedom has just one form. When people are fully convinced that each of the molecules that make up a liquid carry within itself the force that results in (reaching) a general level (le niveau général = niveau also translated as standard of living, which is suggested here as well as solution to the social problem), they conclude that there is no simpler or surer means of obtaining this level than to leave it alone . All those, therefore, who adopt the thesis, Interests are harmonious, will also agree on the practical solution to the social problem: refrain from interfering with and disrupting (déplacer) these interests. |

| La Contrainte peut se manifester, au contraire, par des formes et selon des vues en nombre infini. Les écoles qui partent de cette donnée : Les intérêts sont antagoniques, n'ont donc encore rien fait pour la solution du problème, si ce n'est qu'elles ont exclu la Liberté. Il leur reste encore à chercher, parmi les formes infinies de la Contrainte, quelle est la bonne, si tant est qu'une le soit. Et puis, pour dernière difficulté, il leur restera à faire accepter universellement par des hommes, par des agents libres, cette forme préférée de la Contrainte. | By contrast, Coercion may assume an infinite number of forms and points of view. The schools of thought that start from the assumption that Interests are in conflict (antagoniques), have therefore not yet done anything to solve this problem except for excluding Freedom. It still remains for them to identify from the infinite number of forms of Coercion the one that is right, if there can indeed be one. Then, as a final difficulty, they will still have to have this preferred form of Coercion universally accepted by the people, by these free agents (des agents libres = these free and acting beings). |

Of course, Bastiat was acutely aware that society was not harmonious in the way it functioned, given the glaring facts of the existence of poverty, war, slavery, and various other forms of oppression, not to mention the social and political problems which gave rise to the recent Revolution of February 1848, facts which the socialist critics of political economy in his day frequently pointed out.

Bastiat had several responses to this line of criticism. Firstly, he argued that there was a tendency for societies to be harmonious ("les grandes tendances sociales sont harmoniques") but nothing inevitable about this occurring because men had free will, were fallible, and often made mistakes. However, if left free to act and make choices, men would correct their mistakes and they individually and society in general would more towards a more harmonious situation. In other words, there existed a self-correcting mechanism which elsewhere he described as "les forces restoratives" (restorative forces). [55] In a new passage which he added to the JDE essay on "Des besoins de l'homme" for the chapter in EH1 he observed that: [56]

| Pour que l’harmonie fût sans dissonance, il faudrait ou que l’homme n’eût pas de libre arbitre, ou qu’il fût infaillible. Nous disons seulement ceci: les grandes tendances sociales sont harmoniques, en ce que, toute erreur menant à une déception et tout vice à un châtiment, les dissonances tendent incessamment à disparaître. | For harmony to exist with no disharmony it would be necessary either for man to have no free will or for him to be infallible. We will just say this: the major social tendencies are harmonious, in that since all error leads to disappointment and all vice to punishment, disharmony tends to disappear quickly. |

Since Bastiat was very witty and loved to play with words, as we can see so ably demonstrated in many of his "Economic Sophisms", it is not surprising that he came up with a clever phrase to encapsulate how free societies were self-correcting. In this case it is "une dissonance harmonique" or a "harmonious disharmony." [57] By this he meant that when people make poor decisions and suffer some temporary "disharmony" or discomfort as a result, they have an incentive to correct their behaviour and restore economic "harmony" to their lives. In other words, the disharmony acts as a corrective to its own existence and eventually helps bring about the restoration of harmony, acting somewhat like Schumpeter's notion of "creative destruction" or what might here be called "harmonising disharmonies."

Secondly, he believed that many people erred in not understanding their "rightly understood interests" and how they were not inherently antagonistic with the interests of others (see the discussion above).

Thirdly, that people had been duped by the sophistical arguments put forward by numerous vested interests which sought government subsidies, monopolies, and protection for their particular industries at the expence of taxpayers and consumers. The political struggles which this system of privilege created led to enormous antagonism and disharmony within society as people jostled for the ear of the King or the Chamber of Deputies to get their special interests protected by "la grande fabrique de lois" (the great law factory) in Paris. [58] Dispelling these "sophisms" was of course the purpose behind the two volumes of Economic Sophisms which Bastiat published between 1845 and 1848. The key sophism Bastiat had identified, what he called "the root stock sophism" was Montaigne's claim that "the gain of one is the loss of another," in other words that the economy was a zero sum game where someone could gain only at the expence of another person. [59] In an angry and almost despairing unpublished sketch he wrote sometime in 1847 Bastiat seems to be almost pulling his hair out in frustration he declared that:

| Sophisme type, sophisme souche, d’où sortent des multitudes de sophismes, sophisme polype, qu’on ne peut couper en mille que pour donner naissance à mille sophismes, sophisme anti humain, anti-chrétien, anti-logique ; boîte de Pandore d’où sont sortis tous les maux de l’humanité, haines, défiances, jalousies, guerres, conquêtes, oppressions ; mais d’où ne pouvait sortir l’espérance. | This is the classic sophism, the root-stock sophism from which comes multitudes of other sophisms; the polyp sophism which you can chop into a thousands piecesonly to see it give birth to a thousand more sophisms; the anti-human, anti-christian, anti-logic sophisme; a Pandora’s Box out of which comes all the suffering of humanity, hatreds, mistrust, jealousies, wars, conquests, oppressions; but from which no hope can come. |

His final and perhaps most important response, was to agree with the socialists that ruling elites, like the "oligarchy" which ruled England and "la classe électorale" (the voting or electoral class) which controlled France before 1848, ruthlessly plundered their own people by institutionalising plunder, or what Bastiat called "la spoliation légale" (legal plunder). Until this system of plunder was removed, disharmony and antagonism would remain an intrinsic part of English and French society. Hence his great interest in writing another, possibly third book, on The History of Plunder" to expose and denounce the cause of all theses disharmonies. In his view war and legal plunder were the two "disturbing factors" which did the most to create and entrench disharmony in society. An idea of what he had in mind for this book can be found in the opening chapter of ES2 "The Physiology of Plunder" (written late 1847), his address "To the Youth of France" in the opening to EH1 and the Conclusion (both written in mid or late 1849), as well as a number of pamphlets such as Property and Plunder (July 1848). [60]

Paillottet tells us in a footnote that Bastiat had told him on the eve of his death how important he thought this project was: [61]

| Un travail bien important à faire, pour l’économie politique, c’est d’écrire l’histoire de la Spoliation. C’est une longue histoire dans laquelle, dès l’origine, apparaissent les conquêtes, les migrations des peuples, les invasions et tous les funestes excès de la force aux prises avec la justice. De tout cela il reste encore aujourd’hui des traces vivantes, et c’est une grande difficulté pour la solution des questions posées dans notre siècle. On n’arrivera pas à cette solution tant qu’on n’aura pas bien constaté en quoi et comment l’injustice, faisant sa part au milieu de nous, s’est impatronisée dans nos mœurs et dans nos lois. | Un travail bien important à faire, pour l’économie politique, c’est d’écrire l’histoire de la Spoliation. C’est une longue histoire dans laquelle, dès l’origine, apparaissent les conquêtes, les migrations des peuples, les invasions et tous les funestes excès de la force aux prises avec la justice. De tout cela il reste encore aujourd’hui des traces vivantes, et c’est une grande difficulté pour la solution des questions posées dans notre siècle. On n’arrivera pas à cette solution tant qu’on n’aura pas bien constaté en quoi et comment l’injustice, faisant sa part au milieu de nous, s’est impatronisée dans nos mœurs et dans nos lois. |

But of course he did not live long enough to see his books on Social and Economic Harmonies completed, let alone another volume on the History of Plunder. This volume might rank alongside Lord Acton's much anticipated History of Liberty as one of the most important classical liberal books never written. [62]

Endnotes

[1] Frédéric Bastiat, Sophismes économiques (Paris: Guillaumin, 1846); Sophismes économiques. 2e série (Paris: Guillaumin, 1848). See my "two volumes in one" online edition of the Sophismes Économiques. See also the Liberty Fund edition of which I was co-editor and translator: The Collected Works of Frédéric Bastiat. In Six Volumes (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 2011-), General Editor Jacques de Guenin. Academic Editor Dr. David M. Hart. Vol. 1: The Man and the Statesman. The Correspondence and Articles on Politics (March 2011); Vol. 2: "The Law," "The State," and Other Political Writings, 1843-1850 (June 2012); Vol. 3: Economic Sophisms and "What is Seen and What is Not Seen" (March, 2017).

[2] Bastiat, Ce qu'on voit et ce qu'on ne voit pas, ou l'Économie politique en une leçon. Par M. F. Bastiat, Représentant du peuple à l'Assemblée nationale, Membre correspondant de l'Institut (Paris: Guillaumin, 1850). See my online edition. See also the Liberty Fund edition of which I was co-editor and translator: The Collected Works of Frédéric Bastiat. In Six Volumes (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 2011-), General Editor Jacques de Guenin. Academic Editor Dr. David M. Hart. Vol. 1: The Man and the Statesman. The Correspondence and Articles on Politics (March 2011); Vol. 2: "The Law," "The State," and Other Political Writings, 1843-1850 (June 2012); Vol. 3: Economic Sophisms and "What is Seen and What is Not Seen" (March, 2017).

[3] Bastiat, Harmonies économiques par M. Fr. Bastiat, Membre correspondant de l’Institut, Représentant du Peuple à l’Assemblée Législative (Paris: Guillaumin, 1850); Harmonies économiques. 2me Édition. Augmentée des manuscrits laissés par l’auteur. Publiée par la Société des amis de Bastiat. (Paris: Guillaumin, 1851). See my online edition.

[4] On self interest as the “le mobile” or “driving force” of society see my essay on “The Social Mechanism and its Driving Force.”

[5] I have written dozens of essays (of short, medium, and long length) on the key concepts of Bastiat’s social and economic theory which I am editing into an anthology called apprpriately enough “Essays on Bastiat”.

[6] For more detail about his plans for this multi-volume work, see my essay on “The Writing of the Economic Harmonies”.

[7] These are discussed in several notes and short essays I have written.

[8] See my essay on “Society is One Great Market.”

[9] On Bastiat’s very Austrian notion of human action see my essay on “Human Action.”

[10] See my essay on “The Law of Individual Responsibility and the Law of Human Solidarity.”

[11] See my essay on “The Great Laws of Economics.”

[12] See my essay on “The ‘Apparatus’ or Structure of Exchange.”

[13] See my essay on “Disturbing and Restorative Factors.”

[14] See my essay on “Bastiat’s Theory of Plunder.”

[15] See my essay on “Theocratic Plunder.”

[16] See my essay on “Functionaryism and Rule by Functionaries.”

[17] Voltaire published the first edition of Éléments de la Philosophie de Newton in 1738 and then an expanded edition in 1741.

[18] Laplace wrote a multi-volume work on Traité de mécanique céleste (Treatise on Celestial Mechanics) (1799-1805) and Arago was a friend of Bastiat who worked at the Paris Observatory and also served in the provisional Government in 1848 as Minister of War.

[19] This chapter in EH was first published in the JDE in January 1848 as "Organisation naturelle Organisation artificielle,” JDE, T. XIX, No. 74, Jan 1848, pp. 113-26. It was revised slightly and appeared in the first edition of Economic Harmonies which was published in January 1850. It was an unnumbered introduction to the book. In the second expanded edition of Economic Harmonies which was published in July 1851 by Paillottet and Fontenay it was chapter I. See, EH 1st ed. Jan. 1850, pp. 25-51; EH2 2nd. edition July 1851, pp. 15-33.

[21] Capitale et rente (Paris: Guillaumin, 1849) in OC5, p.52 link.

[22] See my essay on “The Paris School of Political Economy” - the sort version as a chapter in The Cambridge History of French Thought, ed. Michael Moriarty and Jeremy Jennings (Cambridge University Press, 2019), pp. 301-12; and a longer online version.

[23] Molinari, Gustave de, Les Soirées de la rue Saint-Lazare; entretiens sur les lois économiques et défense de la propriété. (Paris: Guillaumin, 1849). See my online edition.

[24] Gustave de Molinari, Les Lois naturelles de l'économie politique (Paris: Guillaumin, 1887).

[25] These were “la loi naturelle de l’économie des forces ou du moindre effort” (the natural law of the economising of forces, or of the least effort), “la loi naturelle de la concurrence” (the natural law of competition) or “la loi de libre concurrence” (the law of free competition), “la loi naturelle de la valeur” (sometimes also expressed as “la loi de progression des valeurs”) (the natural law of value, or the progression of value), “la loi de l’offre et de la demande” (the law of supply and demand), “la loi de l’équilibre” (the law of economic equilibrium), and “Malthus’ law of population growth.”

[26] From Adam Ferguson, An Essay on the History of Civil Society, 5th ed. (London: T. Cadell, 1782). Quote online.

[27] The French edition was Adam Ferguson, Essai sur l'histoire de la société civile, 2 vols. Translated by Jean Nicolas Démeunier (Paris: Chez la Veuve Desaint, 1783). See the entry on "Fergusson, Adam," (sic) in DEP, vol. 1, pp. 758-59.

[28] ES1.18 “Il n'y a pas de principes absolus” (There are no Absolute Principles) ; OC4, pp. 94-97 link; CW3, pp. 84-85.

[29] See my essay on “The Social Mechanism and its Driving Force.”

[30] "Sur l'ouvrage de M. Dunoyer, De la Liberté du travail" (On the Book by M. Dunoyer. On The Liberty of Working) (unpublished paper), OC1.10, pp. 428-33; quote OC1, pp. 428-29, link.

[31] "Un économiste à M. de Lamartine. A l'occasion de son écrit intitulé: Du Droit au travail" (Letter from an Economist to M. de Lamartine. On the occasion of his article entitled: The Right to a Job) Journal des Économistes, Feb. 1845, T. 10, no. 39, pp. 209-223 OC1.9, pp. 406-28, link; quote OC1, p. 421.

[32] See HE2, p. 13 link; and EH, FEE ed. p. xxxv.

[33] Interestingly, this sentence was not in the version which appeared in the JDE article but was added to the version which appeared as a chapter in EH1 II. Besoins, Efforts, Satisfactions”, HE2, p. 38 link.

[34] It should be noted that Bastiat talked about "social harmony" in the singular and "social harmonies" in the plural but only about "economic harmonies" in the plural.

[35] Letter 39 to Félix Coudroy (Paris, 6 June 1845), in OC1, p. 57 link; CW1, p. 64.

[36] Letter 81 to Félix Coudroy (Paris, Aug. 1847), OC1, p. 78 link; CW1, p. 131.

[37] "Projet de préface pour les Harmonies" (Draft Preface for the Harmonies), probably written Fall or late 1847, OC7.73, pp. 303-9 link; CW1, pp. 316-20. Quote OC7, p. 308 link.

[38] Letter 80 to Richard Cobden (Paris, 5 July 1847), in OC1, p. 162 link; CW1, p. 131.

[39] See my essay on "The Writing of the Economic Harmonies”.

[40] See the undated note by Bastiat on the “Economic and Social Harmonies” found among his papers (c. June 1845), HE2, p. vi link

[41] Pierre Ronce, Frédéric Bastiat. Sa vie, son oeuvre (Paris: Guillaumin, 1905), pp. 227-8.

[43] HE2, p. 336 link; FEE ed. p. 325.

[44] "De la population" (On Population), Journal des Économistes, 15 Oct., 1846, T. XV, no. 59, pp. 217-234. A revised version of this article appeared as chap. 16 in the 2nd, posthumous edition of EH (1851), with explanatory notes by Fontenay. Quote from JDE version, p. 232.

[45] Letter 65 to Richard Cobden (Mugron, 25 June 1846) in OC1, p. 136 link; CW1, 106.

[46] Letter 80 to Cobden (Paris, 5 July, 1847), in OC1, p. 162 link; CW1, p. 131.

[47] These paragraphs were repeated in the book HE, p. 37-38 link.

[48] HE, p. 329 link; FEE ed., p. 319.

[49] See my essay on “Disturbing and Restorative Factors.”

[50] “De l'influence des tarifs français et anglais sur l'avenir des deux peuples” (On the Influence of French and English Tariffs on the Future of the Two People), Journal des Économistes, T. 9, octobre 1844, pp. 244-71; OC1.6, p. 334-86; quote OC1 pp. 372-73 link.

[51] HE2, p. 12 link; FEE ed. p. xxiv.

[52] "Seconde lettre à Monsieur de Lamartine" (Second Letter to M. de Lamartine (on price controls on food)), Journal des Économistes, Oct. 1846, T. 15, No. 59, pp. 265-70; OC1.13, pp. 452-60. Quote OC1, p. 459 link.

[53] Baccalauréat et Socialisme (The Baccalaureate and Socialism) (Paris: Guillaumin, 1850); OC4, pp. 442-503; CW2.11, pp. 185-234. Quote OC4, p. 492 link; CW2, p. 225.

[54] EH2, pp. 1-2 link; FEE ed., pp. xxi-xxii.