Images of Liberty and Power:

BÉranger's Songs of Liberty

[Updated October 27, 2011]

|

Béranger on ringing the bell of power

|

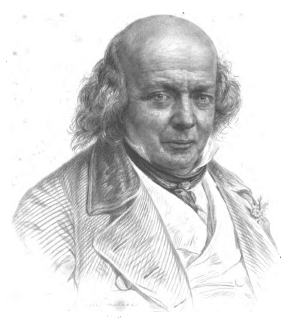

Pierre-Jean de Béranger (1780-1857) |

Biography

Béranger was a poet and songwriter who rose to prominence during the Restoration period with his funny and clever criticisms of the monarchy and the church, which got him into trouble with the censors who imprisoned him for brief periods in the 1820s. Béranger came from a humble background and was apprenticed to a printer at the age of 14. Through the help and patronage of Napoleon’s brother Lucien, Béranger secured a job in the offices of the Imperial University of France and began writing his songs for purely private use, many of which circulated in manuscript form thereby creating an appreciative audience. The satire of Napoleon “Le Roi d’Yvetot” [The King of Yvetot] (1813) was particularly popular. He shot to fame with his first published collection of songs and poems in 1815 (Chansons morales et autre - wittily called "morale" to taunt the censors when in fact they were not) and two more followed in 1821 and 1825. His material was much in demand in the singing societies or “goguettes” which sprang up during the Restoration and the July Monarchy as a way of circumventing the censorship laws and the bans on political parties. After the appearance of his second volume in 1821 he was tried and convicted to 3 months imprisonment in Sainte-Pélagie. Another bout of imprisonment (this time 9 months in La Force) followed in 1828 when his 4th volume was published. Many of the figures who came to power after the July Revolution of 1830 were friends or acquaintances of Béranger and it was assumed he would be granted a sinecure in recognition of his critiques of the old monarchy, but he refused all government appointments in a stinging poem which he wrote in late 1830 called “Le Refus” [The Refusal]. At the age of 68 Béranger was overwhelmingly elected to the Constituent Assembly in April 1848 in which he sat for a brief period (along with fellow Deputy Frédéric Bastiat) before resigning. He began writing as a firm supporter of Napoleon but later evolved into a more mainstream classical liberal who joined Frédéric Bastiat’s Free Trade Society and the Society of Political Economy in Paris in the 1840s.

His books of songs and poems sold very well, enough for him to live modestly off the proceeds and several editions were translated into English, testifying that his popularity extended across both the Channel and the Atlantic. A beautifully illustrated two-volume collection was published in 1847 and we have selected three images from that edition to discuss here: his portrait, the frontispiece to volume 2, and the illustration which accompanied his poem "The Smugglers".

Sources

Source for the illustrations: Oeuvres complètes de P.-J. de Béranger. Nouvelle édition revue par l’auteur. Illustrée de cinquante-deux belles gravures sur acier entièrement inédites, d’après les dessins de MM. Charlet, A. de Lemud, Johannot, Daubigny, Pauquet, Jacques, J. Lange, Pinguilly, de Rudder, Raffet (Paris: Perrotin, 1847). 2 vols.

Source for the poem/song: Béranger: Two Hundred of His Lyrical Poems, done into English Verse by William Young (New York: George P. Putnam, 1850). 183. The Smugglers [Les contrebandiers.], pp. 331-335.

Béranger: The Impish Critic of Church and State

|

|

Béranger spent two periods in prison in the 1820s for offending powerful members of the government and church. In a collection of his poetry published in 1833 he constructed a very funny and cheeky fictional dialogue bewteen himself and a censor over the merits of his poetry, who exactly had been offended by them and why, and the injustice and futility of attempting to silence his voice by force (this has not yet been translated into English). While he was whiling away the three months he spent in the prison of Saint-Pélagie in 1822 he wrote this dark and sarcastic poem called "Liberty" (Young, pp. 208-10) about what the prison experience was doing to him. In it he mocks his jailers by telling them what they want to hear, namely that he had renounced his belief in liberty and had embraced his "worthy turnkeys" and "jailers merry and free", when in fact he remained an ardent supporter of individual liberty and would continue to defy them until the regime was brought down (as it was in 1830 and again in 1848).

110.—LIBERTY. [La Liberté]

Since to dangle some links

Of a chain was my fate,

I've for Liberty felt

The most rancorous hate.

Fie, fie, Liberty, fie!

Down with Liberty, down, say I!'Twas Marchangy, true sage,

Kindly forced me to see

How the slave in our eyes

Should legitimate be.

Fie, fie. Liberty, fie!

Down with Liberty, down, say I!On this deity lavish

Your praises no more!

She leaves the world swaddled

In bands, as of yore.

Fie, fie, Liberty, fie!

Down with Liberty, down, say I!Of her old civic tree

What remains? for our backs

Tyrant's rod—or a sceptre

That majesty lacks.

Fie, fie, Liberty, fie!

Down with Liberty, down, say I!Ask the Tiber; he tasted

Full oft in his time

Of the sweat of the freeman,

Of Papacy's slime.

Fie, fie, Liberty, fie !.

Down with Liberty, down, say I!Common sense is in vogue;

But if lodged in man's pate,

He's a galley-slave only,

Revolting at Fate.

Fie, fie, Liberty, fie!

Down with Liberty, down, say I!Worthy turnkeys, sweet friends,

Jailers merry and free,

To the Louvre, yes, the Louvre,

Bear this greeting for me—

Fie, fie, Liberty, fie!

Down with Liberty, down, say I!

Béranger's Refusal to be a Lackey of the State

Since he was such an effective gadfly to the restored Bourbon monarchy during the 1810s and 1820s, and since some of the more liberal politicians who seized power in the July Revolution of 1830 to install King Louis Philippe on the throne were fans of his writings, it was naturally assumed that he would be given some goverment-funded sinecure as a reward for his subversive activity. He was offered such a sinecure in late 1830 which would have made his life quite comfortable but he refused it in his typical fashion. He wrote a poem/song turning down the offer and giving his reasons: that he had no need for it because his needs were very modest; he did not want to be beholden to anybody, including any sympathetic supporters he might have in the government; that he enjoys his creative freedom; and (in another poem about all his friends in the government) he talks about his political vision which is more democratic in nature and which would be compromised by official honours, where "my vision confusedly brings Privates jumbled with Generals, subjects with Kings".

160.—THE REFUSAL. [Le refus.] SONG ADDRESSED TO GENERAL SEBASTIANI. [Young, pp. 294-95].

A pension from the Court! the offer came;

Mine honor needs not shrink, nor need my name

The Moniteur adorn:

Wants for myself I have but very few;

Yet when the wretched I recall to view,

I seem for riches born.Should poverty or woe afflict a friend,

Honors and rank we may not give or lend;

But gold, at least, we share.

Hurra for gold! for oft, were I a king—

Ay! if five hundred francs it would but bring—

I'd pawn my crown, I swear.If in my cell a little gold should rain,

Quick, God knows where, it vanishes again;

I cannot hold it fast.

To sew my pockets up, I should have had

The needles that belonged to my grand-dad,

When he had breathed his last.Still, let your gold with you, good friend, abide:

Freedom, alas! in youth I made my bride—

A mistress somewhat rude.

I—who in verse was wont to celebrate

Beauties, nor few nor coy—must meet my fate,

In bondage to a prude.Freedom! your Excellency, 'tis a dame

Who blindly dotes on honorable fame—

The proudest minx in town.

She, if in street or drawing-room she spy

The smallest morsel of galloon [lace or silk], will cry,

"Down with the livery! down!"Your crowns would but her condemnation prove;

In fact, why should you by a pension move

My Muse, so true and free?

I am a sou without alloy; but throw

Silver in secret over me, and lo!

False money I should be.Keep, keep your gifts, then; fears I'm apt to feel:

Yet, if too great for me your generous zeal

Should by the world be found,

Know well who your betrayer was—my heart,

Like lute suspended, ever plays its part:

When touched it will resound.

Béranger's Democratic Vision

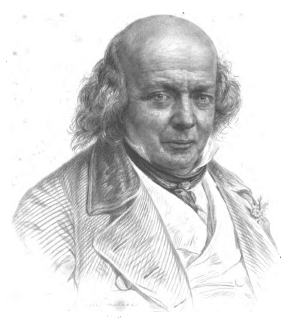

Reference was made above to another of Béranger's poems/songs which is similar to the one where he refuses to accept any state payment for his work following the Revolution of July 1830. In this poem called "To my Friends who have become Ministers"[Young, pp. 292-94] he reminds them that "places, titles, and crosses" bestowed by the King are like "bird-lime" which traps little birds like them and forces them to serve a powerful master. As a democrat and supporter of the people in their struggle against monarchy, he reminds them of the importance of simple pleasures, the worth of the common man, and that in the end, whether they are buried in a grand mausoleum or taken to the grave in a pauper's hearse, they will be equally dead and gone. In one stanza he shares his vision of a democratic society in which "privates (are) jumbled with generals (and) subjects with Kings". The image which appeared as the Frontispiece to volume 2 of his Complete Poems (1847) shows this democratic vision quite clearly.

159. To my Friends who have become Ministers [A mes amis devenus ministres]

I was once carried up—'twas in ecstacy's glow—

To the skies; there I gaze on our world here below:

But the height to my vision confusedly brings

Privates jumbled with Generals, subjects with Kings.

Hark! there's surely a noise; is it Victory's shout?

Hark! a name; what it is I can't clearly make out:

Ye, whose glory down there I see trailing its crest,

God in making me said, "In obscurity rest!"

|

Source: Oeuvres complètes de P.-J. de Béranger. Nouvelle édition revue par l’auteur. Illustrée de cinquante-deux belles gravures sur acier entièrement inédites, d’après les dessins de MM. Charlet, A. de Lemud, Johannot, Daubigny, Pauquet, Jacques, J. Lange, Pinguilly, de Rudder, Raffet (Paris: Perrotin, 1847). 2 vols. Vol. 2 Frontispiece. Description: Béranger's democratic vision is vividly depicted in this engraving. As he stated in his poem "privates (are) jumbled with generals (and) subjects with Kings." In fact, here we also see peasants and sans culottes mixing with bourgeois and aristocrats. In the centre of the image is a plynth on which sits The Muse representing Béranger the poet and song writer ("goguettier") who wrote satirical and critical songs about the injustices he saw around him over a period of nearly 30 years. Gathered around her are representatives of all the social groups Béranger wrote about, either to criticise (generals, political and religious leaders) or to praise (ordinary workers, soldiers, farmers, and shop keepers). There are three sections which are of special note. The first is the person sitting in a chair at the lower right. He has a pair of scissors and is hard at work (with some glee it seems from his facial expression) cutting pages out of many books which lie torn at his feet. This is obviously one of the censors who spent years trying to prevent critics of the régime like Béranger from being heard. The second section is the group of people under the plynth and sitting around its base. It is not clear what is going on here but my interpretation is that the 3 figures huddled in the dark under the plynth represent forces which threaten the liberty of the people (perhaps politicians, members of the legal establishment, hired thugs to beat up opponents of the régime). Above them sit a woman who is holding a broom and a spade and a man who is holding a sword and a tricouleur flag. They are looking fiercely at the men below and are apparently trying to intimidate them and prevent them from coming out of their hole. The third section is the scene of revellry at the very top of the engraving. People are seated at a long table. On the right a plate of roast meat is being delivered to the table. On the left a man is standing holding a glass above his head in his right hand. I would like to think that this man is singing one of Béranger's political songs and entertaining the people who have gathered to eat and drink and enjoy their liberties. |

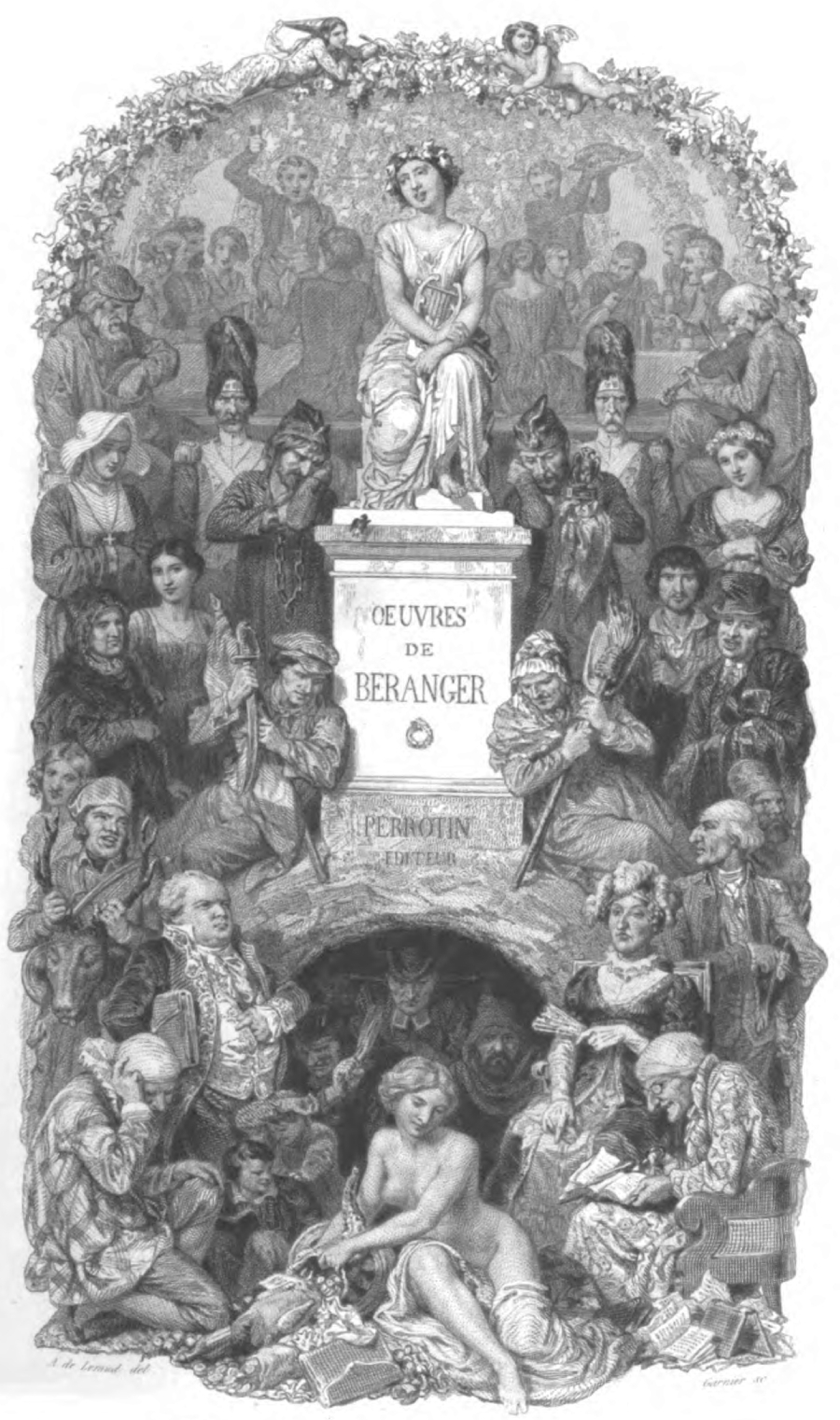

In Praise of Smugglers and Smuggling

More typical of his work is this poem/song called "The Smugglers" (Young, pp. 331-335) in which he sings the praises of the courageous men who defy state restrictions on the free movement of people and goods across arbitrary state borders. The date is not stated but it could be from the time of Napoleon's "Continental Blockade" when he attempted a form of economic warfare against Britain by keeping British goods out of European markets. The border between Spain and France was a major crossing point for smuggled goods at this time.

The free trade and libertarian sentiments of the poem are quite clear. In the refrain he says "Hang the excisemen!"(which is a bit harsh - the French says "down with" but the contemporary English translator thought a stronger word was called for) and that "We (the smugglers) have the people on our side". He justifies smuggling on a number of grounds. One powerful reason is that modern state legislation interfering with trade breaks long-standing traditional ties of language and local law:

What! 'tis their will, that where one tongue is spoken

Where the same laws long time have been obeyed,

Because some treaty may such bonds have broken,

Two hostile nations should, forsooth, be made!

Another reason is that there are strong economic reasons for engaging in trade, namely that it is "convenient" for both parties and that it disseminates wealth to a large number of people ("To bring down plenty to the reach of all, And wealth diffuse"). Government taxes block this necessary exchange and whether governments like it or not, a "balance" in trade must be struck one way or another:

Man might his barter have convenient made,

But taxes blocking up the roads abound;

Then forward, comrades, forward !—such is trade,

That in our hands its balance must be found.

He also has a strong objection to what the taxes raised by tariffs will be spent on by the government. There are the excesses of the aristocratic life, the "fish-ponds" they build for amusement and not for productive purposes; then there is the expenditure on war which at this time was 90% or more of all government expenditure. Thus, by not paying taxes the smugglers create wealth for the ordinary people and limit the state's ability to pay for wars:

Taxes—the which on bloodshed they will spend—

Are levied there:

We—leaping o'er the barriers they defend—

Little we care.

The text of the complete poem/song can be found below, after the illustration.

|

Illustration to Béranger's poem "The

Smugglers" [In an edition of his Collected Works published in 1847] [See larger image 2884 px] |

Source: Oeuvres complètes de P.-J. de Béranger. Nouvelle édition revue par l’auteur. Illustrée de cinquante-deux belles gravures sur acier entièrement in édites, d’après les dessins de MM. Charlet, A. de Lemud, Johannot, Daubigny, Pauquet, Jacques, J. Lange, Pinguilly, de Rudder, Raffet (Paris: Perrotin, 1847). 2 vols. Vol. 2, p. 339. Description: The image is made up of 5 parts: the large central square framed by wooden poles, and 4 smaller panels at each side of the square. In the central square we see a group of smugglers crossing the mountains at night. There is a train of horses or mules which are carrying the cargo (note the feed bag on one of the horses) while a man in peasant clothes strides along higher ground with a gun on the look out for government excisemen. To the right of the square we can see a shoot-out taking place between a smuggler and two government excisemen. In the top panel we can see the smugglers and their train of cargo crossing the French frontier. In the left side panel we can see a woman opening what appears to be the flap of a tent or a cave, perhaps to provide shelter to one of the smugglers. The bottom panel shows a smuggler sharing the profits of his trade with his "fair one": "How is our fair one gladdened, when in showers To till her apron we rain down the gold!", while in the backgrounds other member sof the community are enjoying themselves in a field. |

183.—THE SMUGGLERS. [Les contrebandiers.]

Hang the excisemen! let us get hold

Of pleasures in plenty, and heaps of gold!

We have the people on our side;

They're all our friends at heart:

Yes, lads, the people far and wide,

The people take our part.'Tis midnight—ho there, follow me; prepare

Men, mules, and ventures on their backs—it's time

Forward—ears open for the "Who goes there ?"—

Pistols and guns be sure you load and prime!

The officers are out, in force arrayed;

But lead's not dear:

And you know well that in the thickest shade

Our balls see clear.[Refrain: Hang the excisemen!...]

Comrades, how noble is this life of ours;

What high achievements are there to be told:

How is our fair one gladdened, when in showers

To till her apron we rain down the gold!

Castle, and house, and cottage in our cause

Are all unbarred:

The people will absolve us, if the laws

Should press us hard.[Refrain: Hang the excisemen!...]

Braving the snow, the cold, the rain, the gale,

Lulled by the roar of torrents, we can sleep:

And oh, what draughts of courage we inhale

With the pure breezes, o'er the heights that sweep!

Hundreds of times, those peaks that well we know

Our passage greet:

Our heads are in the clouds, and Death below

Yawns at our feet![Refrain: Hang the excisemen!...]

Man might his barter have convenient made,

But taxes blocking up the roads abound;

Then forward, comrades, forward !—such is trade,

That in our hands its balance must be found.

Heaven, shielding us from ills that might befall,

Works out its views— To bring down plenty to the reach of all,

And wealth diffuse.[Refrain: Hang the excisemen!...]

Our rulers seized with dizziness, who now

Triple their tax on all Heaven kindly yields,

Condemn the fruit to wither on the bough,

And break the hammer that the laborer wields,

They for their fish-ponds would the rivers take,

That from God's hand

Came forth, ordained by him the thirst to slake

Of man and land.[Refrain: Hang the excisemen!...]

What! 'tis their will, that where one tongue is spoken

Where the same laws long time have been obeyed,

Because some treaty may such bonds have broken,

Two hostile nations should, forsooth, be made!

But no—for, thanks to our exertions, vain

Is that design;

The self-same fleeces shall they spin, and drain

The self-same wine.[Refrain: Hang the excisemen!...]

Birds, that at will across the frontier fly,

Find nought to bid them other laws obey:

A summer's sun, perchance, the trench may dry,

That marks the limit of two monarchs' sway.

Taxes—the which on bloodshed they will spend—

Are levied there:

We—leaping o'er the barriers they defend—

Little we care.[Refrain: Hang the excisemen!...]

Song for her theme our deeds will often take,

Whose deadly guns such terror spread around,

That whilst they bid the mountain echoes wake,

Freedom herself may waken at their sound.

When haughty neighbors strike, and bleeding, low

Our country lies,

Her dying words are, "To the rescue, ho!

Smugglers, arise!"[Refrain: Hang the excisemen!...]