“FRÉDÉRIC BASTIAT'S ECONOMIC HARMONIES:

A REASSESSMENT AFTER 170 YEARS”

By David M. Hart

[Created: 10 December, 2019]

[Revised: 8 July, 2024] |

Abstract

Frédéric Bastiat published the first and incomplete part of his treatise on economics, Harmonies économiques (Economic Harmonies) in early 1850. He would be dead by the end of the year with his project still unfinished, so his friends put together from his papers a second enlarged edition which was published in mid-1851. With the completion of my near final draft of a new translation and scholarly edition of the Harmonies Économiques in early 2019, I thought it presented an excellent opportunity for scholars to reassess Bastiat’s contributions to economic theory 170 years after its first appearance. The first attempt at a reassessment came in May 2019 with a Liberty Matters online discussion between a number of economists familiar with his work.

In my opinion the reputation of Bastiat as an economic theorist has suffered from being misunderstood (even by his colleagues and contemporaries), neglected and forgotten (by most economists since his death), being subjected to abusive or dismissive criticism (Marx and Schumpeter), and being damned with faint praise (Hayek and Dean Russell). Nevertheless he has always had a small group of admirers who taught his ideas in the universities (such as Amasa Walker (1799-1875), Arthur Latham Perry (1830-1905), and William Graham Sumner (1840-1910)) in the United States, and even in Australia by William Edward Hearn (1826-1888) at the newly formed University of Melbourne. Others republished his journalism on free trade and protection in the late 19th century, such as the Cobden Club in England, and free trade groups in Chicago and New York City in the U.S.

Closer to our own time, Bastiat's standing was highly regarded by the group of economists and historians who were part of Rothbard’s “Circle Bastiat” at NYU in the 1950s, and Leonard Read and Dean Russell at the Foundation for Economic Education in the 1950s and 1960s who translated nearly half of Bastiat’s writings and thus brought him to the attention of free market conservatives and libertarians in the second half of the 20th century (including myself). To the latter two groups we owe a considerable intellectual debt, but as the Bastiat translation project hopes to show there is much more to know about the life and work of Bastiat, especially his important and innovative contributions to economic theory (the "harmonies" brought about by cooperation and free markets), a broader social theory about the state, plunder, and class (the "disharmonies" brought about by coercion and government privileges), and a unique and very specific vocabulary he developed to express his new ideas.

Contents

- Abstract

- INTRODUCTION

- SOME OBSERVATIONS ABOUT BASTIAT'S IMPORTANCE

- What I find admirable about his Person and Character

- The Impressive Number and Variety of his Activities

- His Personal Courage in Facing a Terminal Disease

- The Radicalism of his Thinking and Behaviour

- Bastiat’s Importance as an Economic Theorist

- Some General Observations

- His important general economic insights

- His Insights of an “Austrian” Nature

- His Insights of a Public Choice Nature.

- Bastiat’s Importance as an Economic Sociologist of the State and State Power

- The Unique Vocabulary he developed to Express his Innovative Ideas

- EXAMPLES OF BASTIAT’S INNOVATIVE THINKING IN THE ECONOMIC HARMONIES

- 1.) The Village carpenter story about the interconnectedness of economic activity

- 2.) The “apparatus of exchange” and the “social mechanism”

- 3.) Human action and the private, subjective nature of decision making

- 4.) An example of a Robinson Crusoe “thought experiment”

- 5.) A discussion of opportunity cost

- 6.) Consumer-centric economic analysis

- 7.) A refutation of Malthusianism pessimism

- 8.) Subjective value theory

- 9.) The idea of “Harmony”

- 10.) The contrast between production vs. plunder

- 11.) His appeal to “men who live by plunder”

- 12.) State functionaries and competition

- 13.) Legal Plunder

- 14.) Disturbing Factors and Displacement

- APPENDICES

- A Proposed "Best of Bastiat" Anthology

- Vocabulary Clusters in the Thought of Frédéric Bastiat

- La Classe (Class)

- Les Causes perturbatrices vs. les Causes réparatrices (Disturbing Factors vs. Restorative

- Factors)

- L'Harmonie vs. la Discordance (Harmony and Disharmony)

- L'Action humaine (Human Action)

- La Spoliation (Plunder)

- Ce qu'on voit et ce qu'on ne voit pas (the Seen and the Unseen)

- BIBLIOGRAPHY

- ENDNOTES

INTRODUCTION↩

With the completion of my final draft [1] of a new translation and scholarly edition of the Harmonies Économiques (Economic Harmonies), I thought it presented an excellent opportunity for scholars to reassess Bastiat’s contributions to economic theory 170 years after its first appearance [2] . The first attempt at this reassessment came in May 2019 with a Liberty Matters online discussion [3] between a number of economists familiar with his work. In my opinion Bastiat as an economic theorist has suffered from being misunderstood (even by his colleagues and contemporaries), neglected and forgotten (by most economists since his death), being subjected to abusive or dismissive criticism (Marx and Schumpeter), and being damned with faint praise (Hayek and Dean Russell). Nevertheless he has always had a small group of admirers who taught his ideas in the universities (such as Amasa Walker (1799-1875), Arthur Latham Perry (1830-1905), and William Graham Sumner (1840-1910)) in the United States, [4] and even in Australia by William Edward Hearn (1826-1888) at the newly formed University of Melbourne. [5] Others republished his journalism on free trade and protection, such as the Cobden club in England, and free trade groups in Chicago and New York city in the U.S. Closer to our own time, the group of economists and historians who were part of Rothbard’s “Circle Bastiat” at NYU in the 1950s, and Leonard Read and Dean Russell at the Foundation for Economic Education in the 1950s and 1960s who translated nearly half of Bastiat’s writings and thus brought him to the attention of free market conservatives and libertarians in the second half of the 20th century (including myself). To the latter two groups we owe a considerable intellectual debt but as the Bastiat translation project hopes to show there is much more to know about the life and work of Bastiat, especially his contributions to economic theory and a broader social theory about the state, plunder, and class.

One hundred and seventy years ago this month (Jan., 2020) the French political economist Frédéric Bastiat (1801-1850) published the first part of what was a planned multi-volume work of economic and social theory on social and economic “harmonies” and “disharmonies.” Sadly he died from what I suspect was throat cancer before he had finished even the first volume on “economic harmonies”, [6] leaving only a few unfinished chapters, fragments of chapters, and notes, which two of his friends cobbled together into an enlarged second edition which they published a few months after his death. [7] I have scoured through his correspondence and other writings to find additional scattered thoughts he had had about this project and attempted to reconstruct what this ambitious project might have looked like had Bastiat been able to complete it. [8] I have also summarized this research in the Liberty Matters online discussion of his work and in several papers which I have written on his life and work.

In addition, in order to assist scholars I have edited and put online in "enhanced HTML" the version of his Oeuvres complètes (Collected Works) which was edited by Paillottet in the 1850s and 1850s (in the individual volumes as they appeared in print), [9] as well as an edition of his works in chronological order in one very large file (1 million words), [10] and finally a list of his works in the form of sortable tables (sortable by date, title, location) - with one table for articles, pamphlets, and books; and another for his correspondence. [11] There are links from the tables to the individual works.

Over the many years I have worked on Bastiat and the other political economists who were part of the “Paris School” [12] my regard for him as an important thinker has grown to the point where I now think that his never finished magnum opus might well have become the classical liberal equivalent of Karl Marx’s also never finished multi-volume work on Das Kapital (the first volume of which appeared in 1859) [13] which had such a profound impact on the socialist and communist movements of the late 19th and 20th centuries and which continues to have up to this day (last year (2018) was the bicentennial of his birth and was commemorated extensively in the press). I would also add that his planned volumes on the Social Harmonies and The History of Plunder should be added to Gertrude Himmelfarb’s list of the “greatest liberal books never written.” [14]

Be that as it may, we do have the very significant though unfinished volume on Economic Harmonies to read and learn from. My hope was that my editorial and translating work on Liberty Fund’s edition would be a) the definitive scholarly edition of that work, and b) part of the rediscovery and rehabilitation of Bastiat as a significant economic and social theorist. [15] I would also urge you to read some of his other major essays and pamphlets to get a sense of his work. I have done my own revised and annotated translations of two of the these key works, The State (1848, 1849) and The Law (1850). One day I would like to publish my own anthology of “The Best of Bastiat” which will show the great diversity of his activities and the originality and richness of his social and economic thought.

In this paper I would like to discuss his importance in a general sense as a classical liberal activist, politician, and thinker, as a person of great courage when facing adversity, and then, more specifically, his importance as an economic and political theorist and the place that Economic Harmonies should have in the history of economic thought. These reflections are a summary of several papers I have written where I have explored these matters in much more detail. They can be found in the Bibliography.

SOME OBSERVATIONS ABOUT BASTIAT"S IMPORTANCE↩

My first encounter with the work of Bastiat, like most people I expect, came from reading his witty and clever economic journalism, the Economic Sophisms in the translation done by the Foundation for Economic Education in the mid-1960s. [16] I was a high-school student in the early 1970s and it was from the FEE editions mailed to me from New York to Sydney, Australia that I was introduced to his ideas. His widely acknowledged skill as an economic journalist and populariser of free market ideas was and still is justified, and the accolade grudgingly acknowledged by Joseph Schumpeter, that he is probably the greatest economic journalist who has ever lived, is basically correct. [17] However, first encounters can be misleading, as they certainly were in my case.

What I find admirable about his Person and Character↩

I find the following things quite admirable about Bastiat’s person and character: the impressive number and variety of his activities, the courage he showed in facing a terminal disease while he continued to work, and the radicalism of his thinking and his behaviour in the pubs and salons of his day..

The Impressive Number and Variety of his Activities

It wasn’t until I began reading his correspondence and other articles which had not been translated into English, some 30 years later, did I realize that there was much more to Bastiat’s accomplishments than just outstanding journalism. (One of the the things I was able to confirm in working on LF’s edition of the complete “economic sophisms” (by the way, there was a third set of "sophisms" FEE was not aware of) was how accurate he was in use use of economic data). [18] He was very unusual in being able to combine journalism, to work as a theorist, to engage in political activism of various kinds, and to become a driving force within the Paris group of political economists around the Guillaumin publishing firm, which the following list of his activities will show:

- he was a fair and efficient local magistrate in his home town of Mugron for many years

- a successful landowner and grape grower and wine producer (in the Bordeaux region) which placed him the top 2% of income earners in France, and thus made him eligible to vote and stand for election in the highly restricted franchise of the July Monarchy (1830-1848)

- a member of a local government council which advised the government on tax matters and public works (such as canals) for which he wrote several important memoranda

- he was a witty and very cultured man who attended salons and goguettes [19] and who had a reputation as a wit, raconteur, singer of political songs, a cellist, and satirist among his friends and neighbors in his home town of Mugron; he would repeat this when he later moved to Paris and became an active participant in several liberal salons which were part of the extensive and influential “Guillaumin network”; much of this is revealed only in his correspondence and in some of the obituaries which were written about him

- a free trade organiser and journalist who ran the French Free Trade Association which he helped found, a forceful speaker, editor, and writer for the weekly magazine Le Libre-Échange; most of the essays in his collection of “economic sophisms” were written for this Association

- a budding economic theorist who burst suddenly onto the Paris scene and poured out a stream of important articles for the influential Journal des Économistes over a 5 year period; shortly after he arrived in Paris he was asked to be the editor of the Journal des Économistes but he turned it down as he wished to run the free trade association; by the end of 1847 he was giving lectures on economics to college students which become the basis of his theoretical treatise Economic Harmonies; in many areas his ideas on economics were insightful, original, and even ahead of their time

- an elected politician in the Second Republic who was an influential member of the Legislative Assembly after the February 1848 Revolution created the Second Republic; he served as Vice-President of the Chamber’s Finance Committee where he tried to cut taxes, reduce government expenditure, and fend off the powerful socialist group who wanted to create a proper welfare state in France for the first time

- an anti-socialist pamphleteer who became one of the most important opponents of socialism which had emerged during the first year or so of the Republic as a formidable force; he wrote 12 anti-socialist pamphlets during this period in which he developed many of his ideas about the state and the nature of plunder, which were key concepts in his political theory. [20]

- the editor of two revolutionary street magazines in 1848 - he was prepared on two occasions to take to the streets of Paris with some of his friends to disseminate ideas about the free market and limited government to ordinary people; he came under fire from troops who were trying to suppress the protesters in February and June 1848; it was in one of these revolutionary street magazines, Jacques Bonhomme, that he published the first version of his famous essay on The State. [21]

- an active participant in the “Guillaumin network” of classical liberal political economists - this included the free trade movement, the Friends of Peace movement at whose 1849 conference he gave a major speech, the Political Economy Society, and the Institute

His Personal Courage in Facing a Terminal Disease

There is another aspect to Bastiat's life to which I should refer, and that is his personal courage and fortitude in living with a very painful and incurable disease which would end his life at the age of 49 years when he was at the peak of his powers. Several times he complained about the “lump” in his throat to his friends in his correspondence. My hunch is that it was throat or oesophageal cancer and not TB which most writers on Bastiat have assumed. [22] One explanation for his frenzy of activity in his last years, as free trade activist, elected politician, economic theorist, and anti-socialist pamphleteer, could be that he he knew he did not have long to live and wanted to make the most of the time he had left. I think that when he left Mugron at the age of 44 to start a new life in Paris he thought he had at least one, perhaps two, very important books he wanted to write before he died. Since he kept getting distracted by other things in Paris during the Revolution he didn’t even manage to finish the one on economics, let alone the others he had planned on social theory and the history of plunder. But in spite of the constant pain (he probably took laudanum (tincture of opium) constantly) and his coughing fits, he rarely complained and continued to think, work, and write until his death.

The Radicalism of his Thinking and Behaviour

In one paper I refer to Bastiat as the “unseen” radical (a pun on one of his best known works, What is Seen and What is Unseen) [23] because there are several radical and unseen “sides” to Bastiat that modern readers are unaware but should take note of. These aspects of Bastiat relate to his geographic location (his isolation for 44 years in a small town in the south west of France), his personal and literary style, as well as the nature of his political and economic ideas. I was particularly struck by how radical a libertarian or classical liberal he was with his idea of self-ownership, [24] his view of victimless crimes, [25] his desire to abolish the standing army and replace it with American style militias, [26] his hatred of war and colonialism, [27] and how late in life he turned to writing material of a theoretical nature (he was in his forties).

In particular I think the following are important in understanding Bastiat the radical liberal:

- his initial radicalisation at a private college with an innovative curriculum (modern languages, poetry, and music; not Latin)

- the social radical, bon-vivant, and non-conformist outsider (what Molinari called “Rabelaisian”) - manifested in his fondness for satire, parody, bawdy wit, and the mocking of authority (political songs of Béranger and the Goguettes); his participation in three Parisian salons - one by the radical republican journalist Hippolyte Castille; one by Anne Say, the wife of Horace Say (the businessman son of Jean-Baptiste Say); and one Hortense Cheuvreux, the wife of a wealthy manufacturer and major financial backer of the classical liberal movement

- his hard-hitting “rhetoric of liberty” and use of “harsh” language to reveal the harm caused by state intervention in the economy - constant reference to the state as a thief and a plunderer. [28]

- his innovative and colourful use of language and the telling of stories to make economic ideas more understandable to ordinary people - “The Petition of the Candle Makers” is just one of hundreds of such stories he used (I list all of the ones he used in EH in the Appendix)

- his total opposition to military spending, standing armies, war, and colonialism/imperialism - he wanted to abolish the standing army and replace it with local militias model, led on the American) - such as his complete opposition to the colonization of Algeria by France, something supported by Tocqueville as part of Frances’ Christian civilizing mission”. [29]

- his “utopian” dreams of drastically cutting the size of government - he wanted to slash government spending immediately by 85% and planned more cuts in the future

- his active support for the Revolution of February 1848 and the Second Republic - he was an ardent republican (unlike many of the other classical liberals who were monarchists like Tocqueville and Dunoyer), he was prepared to go out into the streets and speak directly to the people on at least two occasions at the height of the Revolution (February and June 1848)

- the innovative theoretical economist who was years ahead of his time - many of his most radical economic ideas were either opposed or misunderstood by his fellow economists; his anti-Malthusianism, his emerging subjective value theory, his rejection of Ricardian theory of rent

- his theory of the state’s systematic use of force, fraud, and deception (the “sophisms” used to cloak and justify these activities) which he developed into a theory of the state (with many public choice insights about the self-interested behavior of politicians and bureaucrats), a theory and history of plunder by both individuals (like slave owners), the Church (theocratic plunder), and the State (functionaryism, socialism/communism, and the new bureaucratic and regulatory state). [30]

- he sees the “big picture” of what real liberalism means: that it is a “worldview” (Weltanschauung) based upon the central idea of individual liberty; that liberty is “the sum of all freedoms”, political, economic, and social (see his thinking on “victimless crimes”);his was a “total” and multi-dimensional theory of liberty [31] which was unusual in his day and which resembles modern libertarianism as formulated by people such as Murray Rothbard (who was a great fan of Bastiat).

Bastiat’s Importance as an Economic Theorist↩

In this section I would like to mention some of the many provocative, interesting, and original insights he had in the areas of economic, political, and social theory. I will begin with some general observations about his social theory, then some of his more general economic insights, those insights which are of particular interest to modern day Austrian school economists since Bastiat in many way was a precursor or even a “proto-Austrian” in his approach to economic theory, those that show his “public choice” perspective on the behavior of politicians and bureaucrats, and then his thinking about social theory such as his theory of the state, his theory and history of plunder, and his contributions to the classical liberal theory of class.

Some General Observations

- he combined moral and utilitarian arguments to support his case for liberty; his moral theory was grounded in the idea of natural rights (the individual had a right to life, liberty, and property), but also argued that respecting these rights resulted in greater prosperity and happiness for society as a whole; this was the basis for his idea of “harmony”

- thus, the development of political and economic theory was at a crossroads at the time Bastiat wrote Economic Harmonies (1850); contemporary with him, John Stuart Mill published his Principles of Political Economy (1848) which would become much more influential than Bastiat's work; over the course of the next hundred years the utilitarian approach to political and economic policy of Mill and his followers became the norm, and the moral (natural laws) approach of Bastiat almost disappeared

- he had an individualist methodology of the social sciences - all individuals have interests (self-interest) and “needs” or "wants" which they sought to satisfy; this is “the driving force” of society (not just the economy) and applies equally to governments and their agents (politicians, bureaucrats)

Most of Bastiat's ideas were welcomed by his colleagues in the Political Economy Society, who recognized the power of his writing and his skill as a popularizer of economic ideas (free trade), but in many instances his originality was either rejected or not recognized at the time. The former was quickly recognized by the Institute which made him a “corresponding member” for his book on Cobden and the League (July 1845) and the first collection of Economic Sophisms (Jan. 1846). In the latter case, only a few people understood what he was saying about the nature of exchange (service for service), or his rejection of Malthusian orthodoxy, or the subjective nature of value. He would be recognized for these things only 100 years later by economists like Murray Rothbard who recognized his contributions and incorporated some of his ideas into his own work on exchange for example (“Crusoe economics”). [32]

I have listed what I consider to be Bastiat's most important contributions to economic theory in a couple of papers [33] , and also in my Liberty Matters Lead Essay from May 2019. [34] A summary of these are listed here.

His important general economic insights

- an individualist methodology of the social sciences

- the interdependence or interconnectedness of all economic activity -

- his idea of the “ricochet” or “flow on” effect or the multiplier effect [35]

- it could have a positive effect (e.g. steam power or printing) where product improvements and lower costs get passed on to the consumers

- or a negative effect (tariffs and other government interventions)

- he wanted to be able to quantify the impact of economic events (“double incidence of loss”), use of calculas to calculate “the ricochet or flow on effect” of govt. intervention (sought advice from Fr. Arago the astronomer [36]

- see his early version of Leonard Read’s “I, Pencil” story - “I, Carpenter” (in EH); his version of Leonard Read's "I, Pencil" story: the village cabinet maker and the student [37]

- his idea of the “ricochet” or “flow on” effect or the multiplier effect [35]

- the idea of opportunity cost - “the seen” and “the unseen”. he invented the idea of opportunity cost (as argued by Jasay) [38]

- the idea of ceteris paribus (all other things being equal); JS Mill began using the term also in the mid-1840s and Bastiat seems to have developed his idea independently from Mill [39]

- the idea of the harmony (or the spontaneous order) of the free market; that in the absence of government coercion the free market produces a "harmonious order" in which the different preferences of consumers can be met without recourse to violence. His key idea is that individuals’ “rightly understood” interests may differ but are not inherently in conflict. People can adjust to different individual preferences and engage in mutually beneficial trade. Thus markets are “harmonious.” [40] He contrasts this with its opposite, “disharmony,” which comes about when the market is disrupted by conflict, violence, plunder, and the granting of special political and legal privileges. This leads to disharmony and is not the result of the market itself as critics of the market argued.

- and the related idea of the opposition between a "natural order" (voluntary and spontaneous) and an "artificial order" (coerced and imposed)

- his related theory of “disharmony”; that there are “disturbing and restorative factors” [41]

- the connection between free trade and peace. This was a staple in free trade circles which was articulated by Richard Coben in England and Bastiat in France as part of the free trade movement. It was made up of a group of ideas such as trade (and thus prosperity) flourishes best when there is peace; that mutually beneficial exchange is a strong incentive for peace; and that trade rivalries between states is a major cause for war.

- his very original “consumer-centric” view of economics, in which the purpose of production is consumption. The needs of consumers determines what is produced. Thus he rejects any legislation which favours producers over consumers. Consumers have a list or hierarchy of needs to be satisfied which is potentially unlimited in scope. He make the important observation that every person is both a consumer and a producer, even if it is just by offering the service of their own body and mind to others in an exchange.

- Jasay has argued that Bastiat's notion of negative factor productivity in "The Negative Railway" (c. 1845) was an innovation ahead of its time. [42]

- he challenged several aspects off the orthodox school of classical political economy:

- his rejection of Malthusianism. Bastiat thought economists had underestimated the productive capacity of free markets to solve the problem of food supply, and he thought that humans were choosing and thinking individuals not mindless "plants" and could change their behviour in order to plan the size of their families. He also believed that people were a form of “human capital” and hence valuable; populous towns and cities make exchanges easier (lower transaction costs); there is a greater division of labor). These ideas were rejected by his colleagues who remained strict Malthusians, such as his colleagues and friends Joseph Garner and Gustave de Molinari.

- his rejection of the Ricardian theory of rent. Bastiat had a more general and abstract theory of returns on assets and rejected the idea that land rent was something special (that it was a gift of nature), unlike other forms of income, and hence "unearned". He saw it as just another "service" which was exchanged on the market for mutual benefit.

- his idea that political economy was also a "moral economy" since it assumed or was based upon idea of private property rights and voluntary exchange of that property. He and Molinari believed that economists just couldn"t assume the justice of existing property titles as this played into the hands of socialist critics since existing property distribution included vast privileged interests. He explicitly criticised Adam Smith, J. B. Say, and Benjamin Constant for assuming the legitimacy of existing property rights.

- his theory of exchange as the mutual exchange of services. [43] By abandoning the view that economics was about the creation of "wealth" or the exchange of physical things he was able to define exchange in a much more general and abstract manner to include anything which was valued by consumers. He argued that all human transactions are the reciprocal or mutual exchange of services (or "service for service")

- his idea of the “apparatus” of trade and exchange, by which he meant there was a complex interconnected system or structure of people, institutions, customs, and laws which make complex exchanges over time and place possible [44]

- his criticism of government manipulation of money (paper money); his awareness of the danger of paper money in the hands of a state which wants to expand its activity without imposing the taxes necessary to pay for them; problems caused by below market (or free) interest rates on loans

- that the human labour and exertion which produce physical (material) goods as well as "non-material goods" (or services) is a productive activity and these goods and services have value to others

- the idea of economic equilibrium: the free market has a built-in mechanism for returning to an equilibrium (or near equilibrium) state after being disrupted by "disturbing factors" (war, protectionism, interventionism, taxation); the market is a "self-repairing" order

His Insights of an “Austrian” Nature

A number of modern Austrian economists have recognized that Bastiat was very close to being “an Austrian” himself in the way he approached economic theory. Pete Boettke calls him a “nascent Austrian”. [45] Others like Mark Thornton, Jörg Guido Hülsmann, and Thomas J. DiLorenzo also believe that he was too. I prefer to call him a “proto-Austrian” because he was very close on some issues but not yet there on others. [46]

- the transmission of economic information through the economy which he likened to flows of water or electricity in several hydraulic and electrical metaphors; he was very close to the Hayekian notion of the importance of prices in transmitting information to consumers and producers

- that government regulations, tariff protection, and subsidies to industries cause the “dislocation” of labour and capital which becomes worse when there is an economic downturn - similar to the idea of “malinvestment” (tough Bastiat did not link it to the government’s manipulation of money, credit, and interest rates)

- his subjective theory of value; he had an early form of subjective value theory with his insight that individuals "compare, assess, and evaluate" goods and services before they engage in trade. Although Bastiat explicitly rejected in Economic Harmonies the more subjective theories developed by Condillac in 1776 and Storch in 1823 he does talk about tradable things being "evaluated" differently by individual consumers who mutually benefit from those exchanges.

- his theory of human action; individuals act with a purpose (but, objet), (agens, agissant); - methodological individualism (Crusoe economics).

- Bastiat has a notion that individuals have free will, choose from the alternatives before them, economize their scarce resources, and then act to realize their goals. He uses the very term “l’action humaine” (and its variants - “actif”), [47] thus he is very Austrian in his understanding.

- his use of “Crusoe economics” or thought experiments to analyse the science of human action in the abstract, and the idea that human beings make economic decisions (the economizing of limited resources) even before they become involved in exchanging goods and services with others [48] are praxeological as Rothbard noted and borrowed for the opening chapters on “Exchange” in Man, Economy, and State. In this area he is deeply original and ahead of his time with this line of thinking about economics. It is clear that he has an individualist methodology of the social sciences.

- the role of entrepreneurs (he recognized that they were key actors in economic production but did not details about their exact role))

- that markets solve the problem of economic coordination without central planning: the idea of spontaneous order (the feeding of Paris); unplanned by government bureaucrats - “natural organisation” vs “artificial organisation” (similar to Hayek’s notion of "imposed order") (ordre naturel), harmony. Bastiat argued that the free market “harmoniously” solves the problem of economic coordination without the need for central planners or, as he liked to dismissively call them, “Mechanics,” “Organizers,” or even “Gardeners.” [49] The best example of this is not in Economic Harmonies but in an early essay which appeared in the first collection of Economic Sophisms. Here he tells another economic story about the provisioning of a large city like Paris [50] which is supplied with all its daily needs like food and water and clothing without the assistance of any central planner who has to coordinate the economic activities of hundreds of thousands of people. The profit motive is sufficient for a complex and “harmonious” economic order to evolve without government interference.

- the knowledge problem of central planning by governments

- the idea of time preference - that present goods are valued more highly than future goods, and thus foregoing consumption or use of present goods for future use (saving) requires a premium to be paid

- the unintended consequences of government intervention in the economy

His Insights of a Public Choice Nature.

Bastiat has many “public choice” like notions about the self-interested behavior of politicians and bureaucrats but these are largely scattered and not well developed. [51]

- his theory of the state with its many “public choice” insights about politicians and bureaucrats; that bureaucrats and politicians also have “interests” which they pursue (power, positon, influence, salaries, pensions)

- the idea of “rent-seeking” by vested interests which plays an important part in his essay "The State" (1848); the state provides benefits for vested interests (les droits acquis) and other groups (or “classes”) at the expense of ordinary consumers and taxpayers; these privileged groups seek privileges such as subsidies and protection, or outright “plunder”

- the related idea of “place-seeking” by politicians and bureaucrats who want jobs and positions of power

- his analysis of the activity of parties, factions, and coalitions in the Chamber which disrupt democracy

- his idea that there is a “Malthusian limit” to the growth of state power - there is a “Malthusian limit” to the growth of state power - it will always grow to the limit allowed by the level of taxation which is its “means of subsistance”). [52]

Bastiat’s Importance as an Economic Sociologist of the State and State Power↩

Concerning the size of the state and its permitted functions Bastiat was an advocate of what I call "ultra-limited government", [53] with much fewer permitted functions than Adam Smith who might be regarded as having set the benchmark of the classical liberal notion of "limited government." For Bastiat on the other hand, there were far fewer "public goods" which he thought only the state could and should provide. For example, he was an advocate of free banking and the private provision of education. He also wanted to dismantle the state's large standing army and replace it with much smaller local militias based upon those in the United States. [54]

Bastiat’s thinking about politics, the nature of state power, and his theory of class and plunder [55] (especially his notion of "la spoliation légale" (legal plunder)), [56] is one of his most original and important theoretical contributions. Here is not the place to go into them in any depth as I have dealt with them in other places. In this paper I want to focus on his economic thinking which he developed in his treatise Economic Harmonies., although obviously there is some overlap given the fact that he was a "political economist." What follows below is a brief outline of this dimension of Bastiat's thinking.

Bastiat's theory of plunder has a close connection in his mind to his book on Economic Harmonies. His proposed “history of plunder” was meant to be the third volume of a three volume set on "Economic Harmonies, "Social Harmonies, and "Disharmonies" (i.e. "disturbing factors, organised coercion, and plunder). [57] Throughout his corpus of writing he provides several short discussions of his theory and history of plunder which presumably he wanted to expand into a separate volume at some future date. In these scattered pieces he provides glimpses of his theory of plunder and in the posthumous second edition of Economic Harmonies the editor Paillottet inserts an outline of several planned chapters in which Bastiat would develop his history of plunder through stages. These stages included War, Slavery, Theocracy, Monopoly, “Exploitation gouvernementale” (Exploitation by Government), and “Fausse fraternité ou communisme” (False fraternity or Communism). The last two stages reflected Bastiat’s growing concern during the Second Republic about the rapid growth of the regulatory or bureaucratic state or “functionaryism” as he termed it. [58]

His broader social theory is a form of sociology or historical analysis of institutions (most notably the State) which has a significant economic dimension. In summary this broader social theory includes the following important insights:

- the idea of natural versus artificial orders: Bastiat makes a distinction between “Natural” and “Artificial” Orders, by which he means that an order emerges "spontaneously” (Hayek’s term) when individuals are left free from coercion and theft to go about their own business (literally), and organising voluntary communities and associations of all kinds (civil, religious, political). On the other hand, when violence, force, or fraud, intrudes, this natural order is "disrupted" with significant economic, political, and social costs for all involved. An "artificial" or constructed order (again to use another Haykeian notion) is created when social or economic planners attempt to impose their view of society upon others

- the essential harmony of human social and economic life: harmony is a product of Providence and the natural law which governs human behaviour, especially economic natural laws. By this he means that if left alone, people can achieve their different social and economic needs through cooperation, production, and exchange without "inevitably" violating each other's rights to life, liberty, and property. The harmony of the market is only one of many examples of a broader "social harmony" made possible by non-violent interactions between people.

- the theory of the State as the organisation of plunder: organised "legal plunder" was undertaken by states on behalf of the elites which controlled them. He thus had a theory of class - the plunderers who controlled the state, and their allies, and the plundered who paid the taxes or were forced to labour for the benefit of those elites. He also had an incipient theory of "rent seeking" (although he did not call it that, rather "place-seeking") which plays an important part in his essay "The State" (1848)

- the State maintains its power through a combination of force and ideological deception or "sophistry”: Bastiat believed that the State could not maintain control of the taxpayers by naked force for long. The ordinary person or taxpayer accepted or acceded to the power of State to regulate his or her conduct and to take some or all or his or her property. This insight was central to the purpose of Bastiat's best-known journalism, the Economic Sophisms which were designed to expose the lies (fallacies), deceptions ("la ruse"), and sophistry (twisted half-truths) used by the elites who benefited from state power such as tariffs, subsidies, and grants. He believed that closely allied to the state were a group of intellectuals who used their knowledge and skill at argument to deceive the people about what the state was doing to them and to hide the fact that a small but powerful elite were benefiting from this. They use "la ruse" (trickery and deception) to confuse "les dupes" (the word Bastiat used to describe the gullible ordinary people) that the state was "plundering" them on an almost permanent basis. The role of economists like him was to expose this deception, to delegitimize the activities of the State, and show the people how they were being "filched" (Bastiat has a whole series of words like this to describe what the state does to ordinary taxpayers and consumers).

- the idea that social and political economy is a “moral economy”: Central to Bastiat's social, political, and economic theory is that it had to be grounded on firm moral principles which were an essential part of its structure. He did not believe in a value-free economic or political methodology, rather it had to be based upon a moral foundation of support for private property and non-violence, in other words the natural rights of individuals as he expounded them in his essay "The Law" (July 1850).

The Unique Vocabulary he developed to Express his Innovative Ideas↩

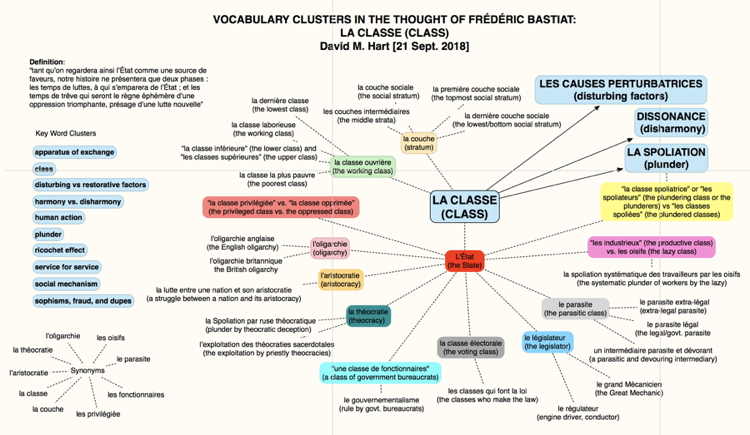

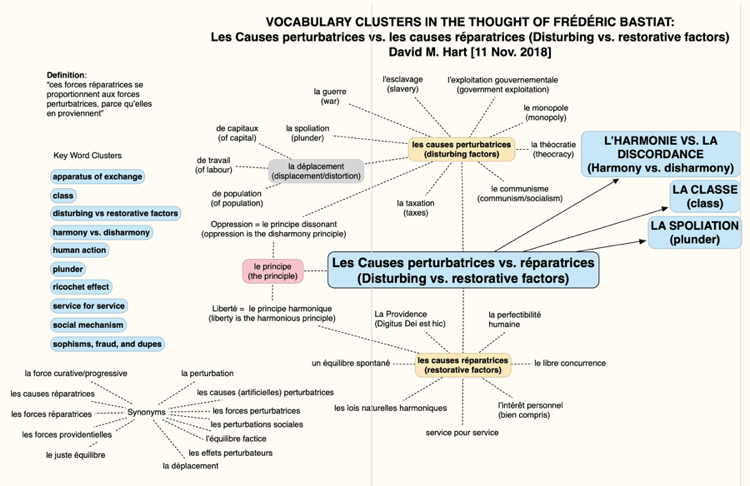

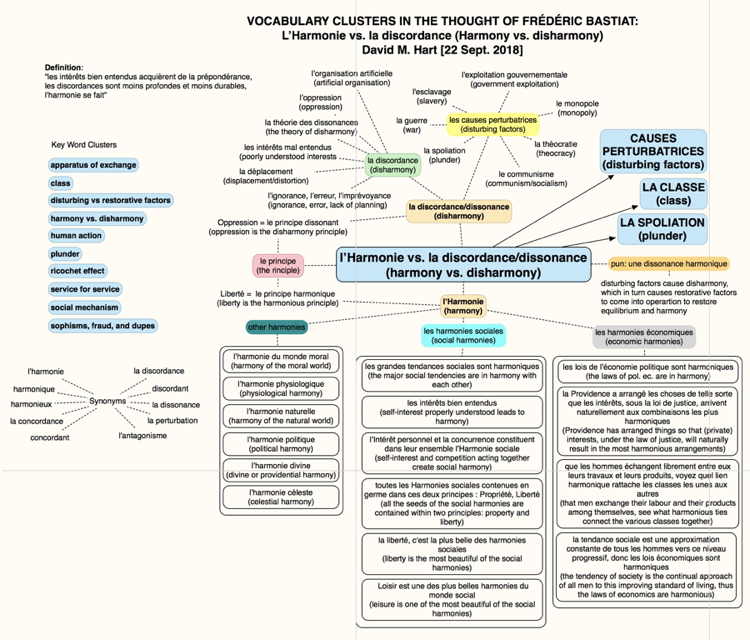

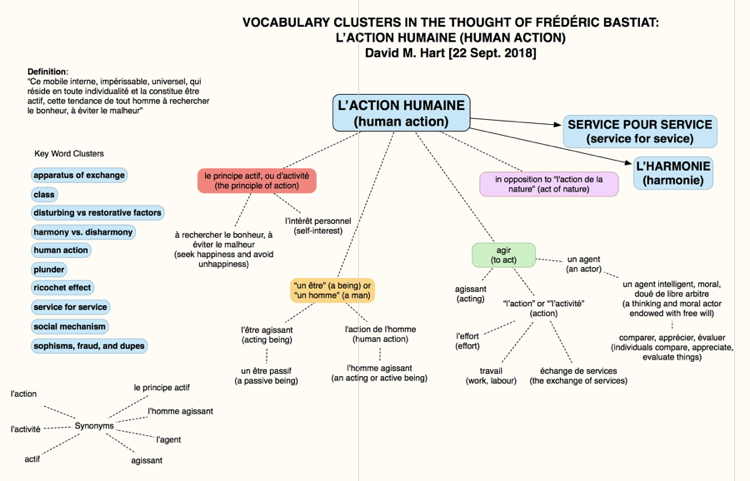

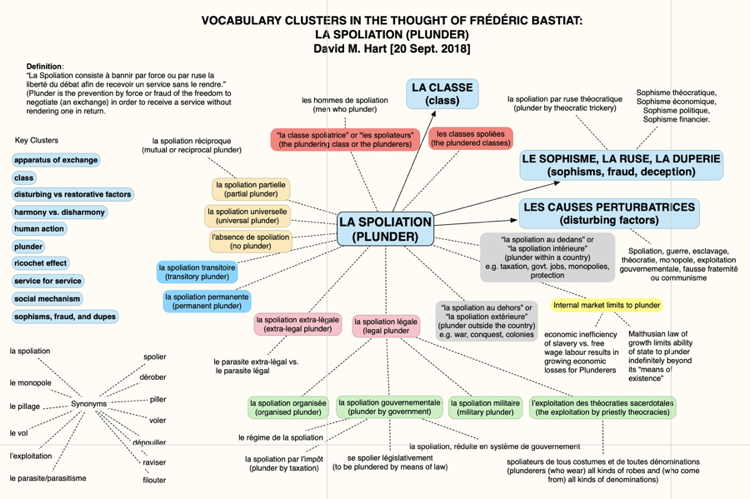

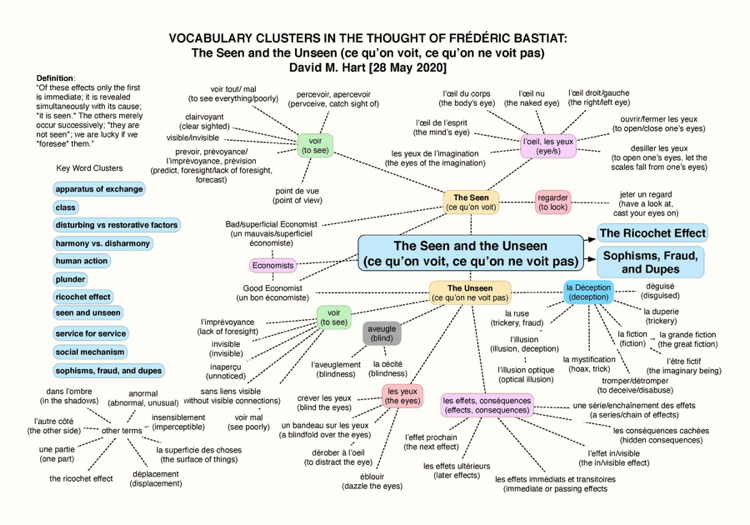

In the course of translating and editing the work of Bastiat I noticed that he used repeatedly a number of key words to describe his economic, social, and political theory. Once I had digitised his corpus (just over 1 million words) I was able to identify these key words and phrases, to note when a key term was first used, to track its use over time, and to note the other terms which he associated with it, often closely related terms or opposite terms. I called them "word or vocabulary clusters".

I observed that Bastiat developed a rich vocabulary of terms which was unique to him, which appeared in an advanced state for the first time in early 1845 in two articles he wrote before he entered the orbit of the Parisian economists, [59] and which evolved gradually over the course of the final six years of his life. I have identified 14 such terms which I list below. For 6 of these key terms I have drawn up a graphical depiction of them and their related terms and their various, sometimes complex interrelations. [60] These 6 terms are:

- La Classe (Class)

- Les Causes perturbatrices vs. les Causes réparatrices (Disturbing Factors vs. Restorative Factors)

- L"Harmonie vs. la Discordance (Harmony and Disharmony)

- L"Action humaine (Human Action)

- La Spoliation (Plunder)

- Ce qu'on voit et ce qu'on ne voit pas (the Seen and the Unseen)

See the Appendix below for the images of these "vocabulary clusters."

The full list of these important terms and their related vocabulary "clusters" is the following (in alphabetical order):

- the apparatus of exchange: the idea of "un appareil" (apparatus or system) is used several times in various contexts; the most important usage is in "l"appareil commercial" (the apparatus or system of commerce) and "l"appareil de l'échange" (the apparatus or system of exchange or trade), by which he meant the complex interlocking relationships which made exchange possible

- class: those who have access to the power of the state use if for their own benefit at the expense of others; the former are the plundering class and latter are the plundered classes; history is the story of the struggle between these two classes, one to maximise its benefits, the other to minimise these impositions

- domains: the domain of the community (or the commons), the domain of private property, and the domain of plunder

- disturbing vs restorative factors: disturbing factors such as theft, violence, fraud, monopoly, protectionism, subsidies, and war upset the harmony which free exchange and markets have created; however, there is a tendency for restorative factors to intervene to restore harmony once it has been disrupted

- harmony vs. disharmony: if people are left free to go about their lives and their property rights are respected, society will tend to be "harmonious" and increasingly prosperous; if force and fraud are allowed to intrude then societies will increasingly become "disharmonious"

- human action: Bastiat refers several times to humans as "un être actif" (an acting or active being), "un agent" (an agent, or actor), "un agent intelligent" (an intelligent or thinking actor), and to their behaviour in the economic world as "l"action humaine" (human action) or "l"action de l'homme" (the action of human beings, or human action), and to the guiding principle behind it all as "le principe actif" or "le principe d'activité" (the principle of action).

- perfectibility and progress: the capacity to improve oneself, to progress both morally and in terms of wealth, was unique to the human species both as individuals and to the societies of which they were members; he was optimistic that there there was "the never ending approach of all classes to a standard of living that is constantly rising"

- plunder: the theory and history of plunder, legal plunder, extra-legal plunder, and the historical stages through which it has evolved (war, slavery, theocratic plunder, monopoly, the modern regulatory state ("governmentalism" or "functionaryism"), and socialism/communism)

- responsibility and solidarity: these two ideas operated like natural laws; individuals learnt from their mistakes and benefited from their appropriate actions; they also had extensive ties with others which bound them in solidarity with the fellow human beings for mutual benefit

- the ricochet effect: the positive and negative flow on effects from economic and political activity which is a result of the interconnectedness of everything in the market; "glisser" (the flow of knowledge); the transmission of information through prices with metaphors of water, hydraulics, and electricity flows

- the seen and the unseen: throughout his writing there are references to "seeing" and "not seeing", "sight" and "foresight", "perceiving" things and being "deceived," seeing things from only "one side" and not all sides.

- service for service: every exchange is a mutually beneficial exchange between two parties who are free to negotiate the terms with each other; what is exchanged is one service for another

- the social mechanism vs. mechanics: society is like a clock or a mechanism (with wheels, springs, and a driving force), the wheels and cogs are thinking, choosing, acting individuals with free will, and the driving force of society which kept everything in motion is individual self-interest; this was disrupted when socialists and others thought they could meddle and regulate the social mechanism as if they were engineers or mechanics

- sophisms: part of Bastiat's "rhetoric of liberty"; those who are duped by false or sophistical arguments; his use of humor and satire to make economics less "dry and boring" and to expose how and why people are duped; his provocative vocabulary of theft, plunder, and other acts of violence

EXAMPLES OF BASTIAT’S INNOVATIVE THINKING IN THE ECONOMIC HARMONIES↩

I listed above some of Bastiat’s most important and original economic insights. Below are some quotations from his treatise Economic Harmonies to illustrate this with specific examples. References are to my online edition of the 1851 French edition.

- the Village carpenter story about the interconnectedness of economic activity. HE, I. Organisation Naturelle. Organisation Artificielle, pp. 17-18 (EH 1 “Natural and Artificial Organisation”).

- the “apparatus of exchange” - on the social mechanism, and orders which emerge spontaneously. HE, IV. Échange, pp. 90-91 (EH 4 “Exchange”)

- human action and the private subjective nature of decision making: HE, XVIII Causes Perturbatrices, pp. 495-96 (EH 18 Disturbing Factors)

- an example of a Robinson Crusoe “thought experiment” in which he creates capital goods for himself and then by extrapolation to the social realm, the justice of exchanging capital or charging others for its use: HE, VII. Capital, pp. 190-91 (EH 7 "Capital")

- a discussion of opportunity cost, HE, VI. Richesse, pp. 182-83 (EH 6 “Wealth”)

- an example of his consumer-centric analysis; producers don’t like competition but it is for the benefit of consumers; competition draws them together in solidarity, HE, X. Concurrence, pp. 322-24 (EH 10 “Competition”)

- the “means of existence” (i.e. the standard of living) is constantly expanding and is thus a refutation of Malthusianism pessimism: HE, XVI. De La Population, pp. 441-44 (EH 16 “On Population")

- an example of his emerging subjective value theory (but he is not consistent in this); HE, V. De La Valeur, pp. 116-17 (EH 5 “On Value”)

- on the idea of “harmony”, HE, IV. Échange, pp. 97-99 (EH 4 “Exchange)

- the contrast between production vs.plunder, HE, XIX. Guerre, pp.502-04 (EH 19 “War”)

- his appeal to “men who live by plunder”, HE, A La Jeunesse Française, pp. 12-14 (EH, “To the Youth of France”)

- state functionaries and competition, HE, XVII. Services Privés, Services Publics, pp. 476-77 (EH 17 “Private and Pubic Services”)

- legal plunder, HE, XVII. Services Privés, Services Publics, pp. 485-88 (EH 17 “Private and Public Services”)

- coercion by the state causes disruption, disturbance, and displacement; opportunity costs; HE, IV. Échange, pp. 95-96 (EH 4 “Exchange”)

1.) The Village carpenter story about the interconnectedness of economic activity [61] ↩

Bastiat was very aware how the various parts of the economy were interconnected and thereby made dependent upon each other in a very fundamental and deep manner. He made this clear in a number of ways in his typical style. A good example is his version of Leonard Read's story of "I, Pencil" (1958) [62] which is partly a story designed to show the Hayekian problem of knowledge (no one person has enough knowledge about all the industrial and organisation processes which go into making a simple lead pencil) and partly a story about the greater productiveness made possible by an international division of labour and international trade (the various components of the pencils such as wood, lead, paint, and rubber come from different parts of the world).

Bastiat has his own story, [63] which we might call "I, Carpenter" in deference to Read, in the opening chapter of Economic Harmonies (so 100 years before Read) about the village carpenter and the student living and studying Paris. [64] In both stories Bastiat stresses the complex co-operation ("a natural and wise order") which has already occurred in the past and which is ongoing in the present which goes into making simple everyday things which we take for granted, as well as "the chain of endless transactions" which binds together all participants in the modern economy. (Part of his purpose here is to argue that because of all the economic activity that has gone on before, the village carpenter receives far more from "the services of others" in the past than he offers for exchange in the present. This was part of his ongoing intellectual battle against the socialists of his day who were arguing that workers like the carpenter were being exploited by their participation in the free market. Bastiat argues the opposite, that they benefit far more than they can ever imagine.)

Prenons un homme appartenant à une classe modeste de la société, un menuisier de village, par exemple, et observons tous les services qu'il rend à la société et tous ceux qu'il en reçoit; nous ne tarderons pas à être frappés de l'énorme disproportion apparente. |

Let us take a man who belongs to a modest class in society, a village carpenter, for example, and let us observe all the services he provides to society and all those he receives from it; it will not take us long to be struck by the enormous apparent disproportion. |

Cet homme passe sa journée à raboter des planches, à fabriquer des tables et des armoires; il se plaint de sa condition, et cependant que reçoit-il en réalité de cette société, en échange de son travail? |

This man spends his day sanding planks and making tables and wardrobes; he complains about his situation and yet what does he receive from this same society in return for his work? |

D"abord, tous les jours, en se levant, il s"habille, et il n'a personnellement fait aucune des nombreuses pièces de son vêtement. Or, pour que ces vêtements, tout simples qu'ils sont, soient à sa disposition, il faut qu'une énorme quantité de travail, d'industrie, de transports, d'inventions ingénieuses, ait été accomplie. Il faut que des Américains aient produit du coton, des Indiens de l'indigo, des Français de la laine et du lin, des Brésiliens du cuir; que tous ces matériaux aient été transportés en des villes diverses, qu'ils y aient été ouvrés, filés, tissés, teints, etc. |

First of all, each day when he gets up he dresses, and he has not personally made any of the many items of his outfit. However, for these garments, however simple, to be at his disposal, an enormous amount of work, production, transport and ingenious invention needs to have been accomplished. Americans need to have produced cotton, Indians indigo, Frenchmen wool and linen and Brazilians leather. All these materials need to have been transported to a variety of towns, worked, spun, woven, dyed, etc. |

Ensuite, il déjeune. Pour que le pain qu'il mange lui arrive tous les matins, il faut que des terres aient été défrichées, closes, labourées, fumées, ensemencées ; il faut que les récoltes aient été préservées avec soin du pillage; il faut qu'une certaine sécurité ait régné au milieu d'une innombrable multitude; il faut que le froment ait été récolté, broyé, pétri et préparé ; il faut que le fer, l'acier, le bois, la pierre, aient été convertis par le travail en instruments de travail; que certains hommes se soient emparés de la force des animaux, d'autres du poids d'une chute d'eau, etc.: toutes choses dont chacune, prise isolément, suppose une masse incalculable de travail mise en jeu, non-seulement dans l'espace, mais dans le temps. |

He then has breakfast. In order for the bread he eats to arrive each morning, land had to be cleared, fenced, ploughed, fertilized and sown. Harvests had to be stored and protected from pillage. A degree of security had to reign in the context of an immense multitude of souls. Wheat had to be harvested, ground, kneaded and prepared. Iron, steel, wood and stone had to be changed by human labor into tools. Some men had to make use of the strength of animals, others the weight of a waterfall, etc.; all things each of which, taken singly, implies an incalculable mass of labor put to work , not only in space but also in time. |

Cet homme ne passera pas sa journée sans employer un peu de sucre, un peu d'huile, sans se servir de quelques ustensiles. |

This man will not spend his day without using a little sugar, a little oil or a few utensils. |

Il enverra son fils à l'école, pour y recevoir une instruction qui, quoique bornée, n'en suppose pas moins des recherches, des études antérieures, des connaissances dont l'imagination est effrayée. [18] |

He will send his son to school to receive instruction, which although limited, nonetheless implies research, previous studies and knowledge such as to affright the imagination. |

Il sort : il trouve une rue pavée et éclairée. |

He goes out and finds a road that is paved and lit. |

On lui conteste une propriété : il trouvera des avocats pour défendre ses droits, des juges pour l'y maintenir, des officiers de justice pour faire exécuter la sentence; toutes choses qui supposent encore des connaissances acquises, par conséquent des lumières et des moyens d'existence. |

His ownership of a piece of property is contested; he will find lawyers to defend his rights, judges to maintain them, officers of the court to carry out the judgment, all of which once again imply acquired knowledge and consequently understanding and proper means of existence. |

Il va à l'église: elle est un monument prodigieux, et le livre qu'il y porte est un monument peut-être plus prodigieux encore de l'intelligence humaine. On lui enseigne la morale, on éclaire son esprit, on élève son âme; et, pour que tout cela se fasse, il faut qu'un autre homme ait pu fréquenter les bibliothèques, les séminaires, puiser à toutes les sources de la tradition humaine, qu'il ait pu vivre sans s"occuper directement des besoins de son corps. |

He goes to church; it is a prodigious monument and the book he carries is a monument to human intelligence perhaps more prodigious still. He is taught morality, his mind is enlightened, his soul elevated, and in order for all this to happen, another man had to be able to go to libraries and seminaries and draw on all the sources of human tradition; he had to have been able to live without taking direct care of his bodily needs. |

Si notre artisan entreprend un voyage, il trouve que, pour lui épargner du temps et diminuer sa peine, d'autres hommes ont aplani, nivelé le sol, comblé des vallées, abaissé des montagnes, joint les rives des fleuves, amoindri tous les frottements, placé des véhicules à roues sur des blocs de grès ou des bandes de fer, dompté les chevaux ou la vapeur, etc. |

If our craftsman sets out on a journey, he finds that, to save him time and increase his comfort, other men have flattened and leveled the ground, filled in the valleys, lowered the mountains, joined the banks of rivers, increased the smooth passage on the route, set wheeled vehicles on paving stones or iron rails, and mastered the use of horses, steam, etc. |

Il est impossible de ne pas être frappé de la disproportion véritablement incommensurable qui existe entre les satisfactions que cet homme puise dans la société et celles qu'il pourrait se donner s"il était réduit à ses propres forces. J"ose dire que, dans une seule journée, il consomme des choses qu'il ne pourrait produire lui-même dans dix siècles. |

It is impossible not to be struck by the truly immeasurable disproportion that exists between the satisfactions drawn by this man from society and those he would be able to provide for himself if he were to be limited to his own resources. I make so bold as to say that in a single day, he consumes things he would not be able to produce by himself in ten centuries. |

2.) The “apparatus of exchange” and the “social mechanism” [65] ↩

Cependant, l'Echange est un si grand bienfait pour la société (et n'est-il pas la société elle-même ?), qu'elle ne s"est pas bornée, pour le faciliter, pour le multiplier, à l'introduction de la [91] monnaie. Dans l'ordre logique, après le Besoin et la Satisfaction unis dans le même individu par l'effort isolé, — après le troc simple, — après le troc à deux facteurs, ou l'Échange composé de vente et achat, — apparaissent encore les transactions étendues dans le temps et l'espace par le moyen du crédit, titres hypothécaires, lettres de change, billets de banque, etc. Grâce à ces merveilleux mécanismes, éclos de la civilisation, la perfectionnant et se perfectionnant eux-mêmes avec elle, un effort exécuté aujourd"hui à Paris ira satisfaire un inconnu par delà les océans et par delà les siècles, et celui qui s"y livre n'en reçoit pas moins sa récompense actuelle, par l'intermédiaire de personnes qui font l'avance de cette rémunération et se soumettent à en aller demander la compensation à des pays lointains ou à l'attendre d'un avenir reculé. Complication étonnante autant que merveilleuse, qui, soumise à une exacte analyse, nous montre, en définitive, l'intégrité du phénomène économique, besoin, effort, satisfaction, s"accomplissant dans chaque individualité selon la loi de justice. |

However, exchange is such a great benefit to society (and is it not exchange, society itself?) that for purposes of facilitating and increasing exchange, society has not been confined to the introduction of money. In logical order, after need and satisfaction united in the same person through isolated effort, after simple barter, after barter with two factors or compound exchange made up of sale and purchase, there is yet another form of transaction (which is) extended through time and space by means of credit, mortgage titles, letters of exchange, bank notes, etc. Thanks to these marvelous mechanisms, born of civilization, which advance it and are themselves advanced by it, an effort undertaken today in Paris will go to satisfy an unknown person beyond the seas and across the centuries, and he who carries it out receives his compensation now, (since) there are people who make loans to cover this payment and are prepared to subject themselves to asking for their payment in far-off countries or to waiting for it in the remote future. This complication, as astonishing as it is marvelous, when analyzed in detail, in the end shows us the unity of the economic phenomena of “need, effort and satisfaction,” taking place within each individual according to the law of justice. |

Bornes de l'Échange. Le caractère général de l'Échange est de diminuer le rapport de l'effort à la satisfaction. Entre nos besoins et nos satisfactions s"interposent des obstacles que nous parvenons à amoindrir par l'union des forces ou par la séparation des occupations, c"est-à-dire par l' Echange. Mais l'Échange lui-même rencontre des obstacles, exige des efforts. La preuve en est dans l'immense masse de travail humain qu'il met en mouvement. Les métaux précieux, les routes, les canaux, les chemins de fer, les voitures, les navires, toutes ces choses absorbent une part considérable de l'activité humaine. Voyez, d'ailleurs, que d'hommes uniquement occupés à faciliter des échanges, que de banquiers, négociants, marchands, courtiers, voituriers, marins! Ce vaste et coûteux appareil prouve mieux que tous les raisonnements ce qu'il y a de puissance dans la faculté d'échanger; sans cela comment l'humanité aurait-elle consenti à se l'imposer? |

The Limits to Exchange The general characteristic of all exchange is that it decreases the ratio of effort to satisfaction. Between our needs and satisfactions there are obstacles that we succeed in reducing by the joint use of our strength or the division of labor, that is to say through exchange. However, exchange itself encounters obstacles and requires effort. The proof of this lies in the immense amount of human labor it generates. Precious metals, roads, canals, railways, carriages, or ships: all these things absorb a considerable amount of human activity. What is more, look at the number of men whose sole occupation lies in facilitating exchange, how many bankers, traders, merchants, brokers, coachmen, or sailors there are! This huge and costly apparatus is better proof than all forms of reasoning of the power that lies in our ability to exchange. Without it this why would the human race have agreed to impose such an apparatus on itself? |

3.) Human action and the private, subjective nature of decision making [66] ↩

L"homme est jeté sur cette terre. Il porte invinciblement en lui-même l'attrait vers le bonheur, l'aversion de la douleur.— Puisqu"il agit en vertu de cette impulsion, on ne peut nier que l'Intérêt personnel ne soit le grand mobile de l'individu, de tous les individus, et par conséquent de la société. — Puisque l'intérêt personnel, dans la sphère économique, est le mobile des actions humaines et le grand ressort de la société, le Mal doit en provenir comme le Bien ; c"est en lui qu'il faut chercher l'harmonie et ce qui la trouble. |

Man has been cast upon the earth. He is irresistibly attracted to happiness and averse to pain. Since he acts in line with these impulses, it cannot be denied that self-interest is not the great driving force within individuals, (that is in) all individuals, and consequently in society. Since in the sphere of economics, self-interest is the driving force of human action and the mainspring of society, harm can come from it just as good can. It is in self-interest that both harmony and what disrupts it have to be sought. |

L"éternelle aspiration de l'intérêt personnel est de faire taire le besoin, ou plus généralement le désir, par la satisfaction. |

The eternal goal of self-interest is to silence (the voice of) need, or in more general terms, (silence the voice of) desire through satisfaction. |

Entre ces deux termes, essentiellement intimes et intransmissibles, le besoin et la satisfaction, s"interpose le moyen transmissible, échangeable; l'effort. |

Between these two extremes, need and satisfaction, which are deeply private and incapable of being transferred (to another), can be found the way in which they can be made transferrable and exchangeable: (namely through) effort. |

Et au-dessus de l'appareil, plane la faculté de comparer, de juger: l'intelligence. Mais l'intelligence humaine est faillible. [496] Nous pouvons nous tromper. Cela n'est pas contestable; car si quelqu"un nous disait: l'homme ne peut se tromper, nous lui répondrions : ce n'est pas à vous qu'il faut démontrer l'harmonie. |

And above the entire apparatus (of exchange) hovers the ability to compare and judge: that is our mind. However, the human mind is fallible. We can make mistakes. This cannot be denied, for if someone said to us: “Human beings cannot make mistakes,” our answer to him would be: “You are not the person to whom harmony needs to be demonstrated. |

Nous pouvons nous tromper de plusieurs manières ; nous pouvons mal apprécier l'importance relative de nos besoins. En ce cas, dans l'isolement, nous donnons à nos efforts une direction qui n'est pas conforme à nos intérêts bien entendus. Dans l'ordre social, et sous la loi de l'échange, l'effet est le même; nous faisons porter la demande et la rémunération vers un genre de services futiles ou nuisibles, et déterminons de ce côté le courant du travail humain. |

We can make several types of mistake: we can fail to assess correctly the relative importance of our needs. In the case (of living) in isolation, we direct our efforts toward a goal that is not in our best interests. In the social order and subject to the law of exchange, the effect is the same: we focus (our) demand (on) and (are willing to pay for) a type of service that is unimportant or harmful, (thus) causing the current of human work to flow in this direction. |

Nous pouvons nous tromper encore, en ignorant qu'une satisfaction ardemment cherchée ne fera cesser une souffrance qu'en ouvrant la source de souffrances plus grandes. Il n'y a guère d'effet qui ne devienne cause. La prévoyance nous a été donnée pour embrasser l'enchaînement des effets, pour que nous ne fassions pas au présent le sacrifice de l'avenir; mais nous manquons souvent de prévoyance. |

We can make a different type of mistake by failing to realize that a (too) fervently sought satisfaction will remedy suffering only by opening the door to even greater suffering. There is scarcely any effect that does not become (in its turn) a cause. Foresight has been given to us to grasp the relationship between cause and effect so that we may avoid sacrificing the future to the present; however, we often lack (this) foresight. |

L"erreur déterminée par la faiblesse de notre jugement ou par la force de nos passions, voilà la première source du mal. Elle appartient principalement au domaine de la morale. Ici, comme l'erreur et la passion sont individuelles, le mal est, dans une certaine mesure, individuel aussi. La réflexion, l'expérience, l'action de la responsabilité en sont les correctifs efficaces. |

Error which has sprung from a weakness of judgment or the force of feeling is the leading source of harm. It relates principally to the sphere of morals. Here, since error and passion are individual, (this type of) harm is to a certain extent also individual. Reflection, experience, and responsible behaviour are effective corrections for this. |

4.) An example of a Robinson Crusoe “thought experiment” [67] ↩

An example of Robinson Crusoe creating capital goods for himself and then by extrapolation to the social realm, the justice of exchanging capital or charging for its use:

Plus tard, toutes les facilités s"accroîtront de concert. La réflexion et l'expérience auront appris à notre insulaire à mieux opérer; le premier instrument lui-même lui fournira les moyens d'en fabriquer d'autres et d'accumuler des provisions avec plus de promptitude. |

Later on, all (his) faculties will improve together. Reflection and experience will have taught our island dweller how to do things better. The initial tool itself will supply him with the means to make others and to amass a stock of provisions more quickly. |

Instruments, matériaux, provisions, voilà sans doute ce que Robinson appellera son capital, et il reconnaîtra aisément que plus ce capital sera considérable, plus il asservira de forces naturelles, plus il les fera concourir à ses travaux, plus enfin il augmentera le rapport de ses satisfactions à ses efforts. |

Tools, materials, and provisions are what Robinson Crusoe will doubtless call his capital, and he will readily acknowledge that the more of this capital he has, the more use he will make of the forces of nature, the more these forces will assist his work, and in the end the greater will be the relationship between his satisfaction and his effort. |

Plaçons-nous maintenant au sein de l'ordre social. Le Capital se composera aussi des instruments de travail, des matériaux et des provisions sans lesquels, ni dans l'isolement ni dans la société, il ne se peut rien entreprendre de longue haleine. Ceux qui se trouveront pourvus de ce capital ne Tauront que parce qu'ils l'auront créé par leurs efforts ou par leurs privations, et ils n'auront fait ces efforts (étrangers aux besoins actuels), ils ne se seront imposé ces privations qu'en vue d'avantages ultérieurs, en vue, par exemple, de faire concourir désormais une [191] grande proportion de forces naturelles. De leur part, céder ce capital, ce sera se priver de l'avantage cherché, ce sera céder cet avantage à d'autres, ce sera rendre service. Dès lors, ou il faut renoncer aux plus simples éléments de la justice, il faut même renoncer à raisonner, ou il faut reconnaître qu'ils auront parfaitement le droit de ne faire cette cession qu'en échange d'un service librement débattu, volontairement consenti. Je ne crois pas qu'il se rencontre un seul homme sur la terre qui conteste l'équité de la mutualité des services, car mutualité des services signifie, en d'autres termes, équité. Dira-t-on que la transaction ne devra pas se faire librement, parce que celui qui a des capitaux est en mesure de faire la loi à celui qui n'en a pas? Mais comment devra-t-elle se faire? A quoi reconnaître l'équivalence des services, si ce n'est quand de part et d'autre l'échange est volontairement accepté? Ne voit-on pas d'ailleurs que l'emprunteur, libre de le faire, refusera, s"il n'a pas avantage à accepter, et que l'emprunt ne peut jamais empirer sa condition? Il est clair que la question qu'il se posera sera celle-ci : L"emploi de ce capital me donnera-t-il des avantages qui fassent plus que compenser les conditions qui me sont demandées? ou bien: L"effort que je suis maintenant obligé de faire pour obtenir une satisfaction donnée, est-il supérieur ou moindre que la somme des efforts auxquels je serai contraint par l'emprunt, d'abord pour rendre les services qui me sont demandés, ensuite pour poursuivre cette satisfaction à l'aide du capital emprunté? |

Let us now move into the social realm. Here too, capital will be made up of tools, materials, and provisions without which, neither in isolation nor in society, can anything be done over a long period. Those who have this capital will have it only because they have created it through their (own) efforts or privations and they will not have made these efforts (reaching beyond their current needs) nor imposed these privations on themselves, without having future benefits in sight, for example, with a view to harnessing a significant proportion of the forces of nature from now on. From their point of view, to give up this capital would be to deprive themselves of the benefit sought and hand it over to someone else; it would be to provide a service. In this case, either we would have to renounce the most elementary principles of justice and even renounce reasoning (itself), or we would have to acknowledge that they have a perfect right to make this transaction only in exchange for a service that has been freely negotiated and voluntarily agreed to. I do not think there is a single person on earth who disputes the justice of the mutuality of services, since the mutuality of services is another way of expressing justice. Will people say that transactions should not be made freely because the person who has the capital is in a position to dictate to the one who does not? But how should they be carried out? How can we recognize the equivalence of services if not by the fact that each party has voluntarily agreed to the exchange? What is more, do we not see that the borrower who is free to do so will refuse if there is no advantage to him in accepting, and that the loan can never make his situation worse? It is clear that the question he will ask himself is this: Will the use of this capital provide me with benefits that will more than compensate the conditions asked of me? Or else: Is the effort I am currently obliged to devote to obtaining a given satisfaction greater or less than the sum of the efforts the loan will oblige me to make, first of all to provide the services asked of me and then to seek this satisfaction using the capital I have borrowed? |

5.) A discussion of opportunity cost [68] ↩

L"air, l'eau, la lumière sont gratuits, dites-vous. C"est vrai, et [183] si nous n'en jouissions que sous leur forme primitive, si nous ne les faisions concourir à aucun de nos travaux, nous pourrions les exclure de l'économie politique, comme nous en excluons l'utilité possible et probable des comètes. Mais observez l'homme au point d'où il est parti et au point où il est arrivé. D"abord il ue savait faire concourir que très—imparfaitement l'eau, l'air, la lumière et les autres agents naturels. Chacune de ses satisfactions était achetée par de grands efforts personnels, exigeait une très-grande proportion de travail, ne pouvait être cédée que comme un grand service, représentait en un mot beaucoup de valeur. Peu à peu cette eau, cet air, cette lumière, la gravitation, l'élasticité, le calorique, l'électricité, la vie végétale sont sortis de cette inertie relative. Ils se sont de plus en plus mêlés à notre industrie. Ils s"y sont substitués au travail humain. Ils ont fait gratuitement ce qu'il faisait à titre onéreux. Ils ont, sans nuire aux satisfactions, anéanti de la valeur. Pour parler en langue vulgaire, ce qui coûtait cent francs n'en coûte que dix, ce qui exigeait dix jours de labeur n'en demande qu'un. Toute celle valeur anéantie est passée du domaine de la Propriété dans celui de la Communauté. Une proportion considérable d'efforts humains ont été dégagés et rendus disponibles pour d'autres entreprises; c"est ainsi, qu'à peine égale, à services égaux, à valeurs égales, l'humanité a prodigieusement élargi le cercle de ses jouissances, et vous dites que je dois éliminer de la science cette utilité gratuite, commune, qui seule explique le progrès tant en hauteur qu'en surface, si je puis m"exprimer ainsi, tant en bien-être qu'en égalité! |