“FRÉDÉRIC BASTIAT ON PLUNDER, CLASS, AND THE STATE”

By David M. Hart

[Created: 25 October, 2021]

[Revised: 2 April, 2025 ] |

This essay was written to accompany an anthology of Bastiat's writings on plunder, class, and the state:

Frédéric Bastiat, La Spoliation, la Classe, et l’État (Plunder, Class, and State): An Anthology of Texts (1845-1851). Edited and with an Introduction by David M. Hart (Sydney: The Pittwater Free Press, 2023). online.

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Bastiat’s Writings on Plunder, Class and the State

- The Origin and Foundation of Bastiat’s Theory of Plunder and Class

- Bastiat's Theory of Plunder and Class

- An Outline of Bastiat’s Theory of Class and Plunder

- The Moral Foundations of Bastiat’s Theory of Plunder: “Thou shalt not steal.”

- “La Ruse” (Fraud, Trickery) and Legal Plunder

- Plunder by Direct or Indirect Violence

- A Case Study of Plunder

- Theocratic Plunder

- The Malthusian Limits to State Plunder

- The Impact of the February Revolution on Bastiat’s Theory of Class

- Conclusion

- The Class Interest of Bastiat the Landowner

- Bastiat’s Impact on Clément, Molinari, Pareto, and Rothbard

- Conclusion: What might have been?

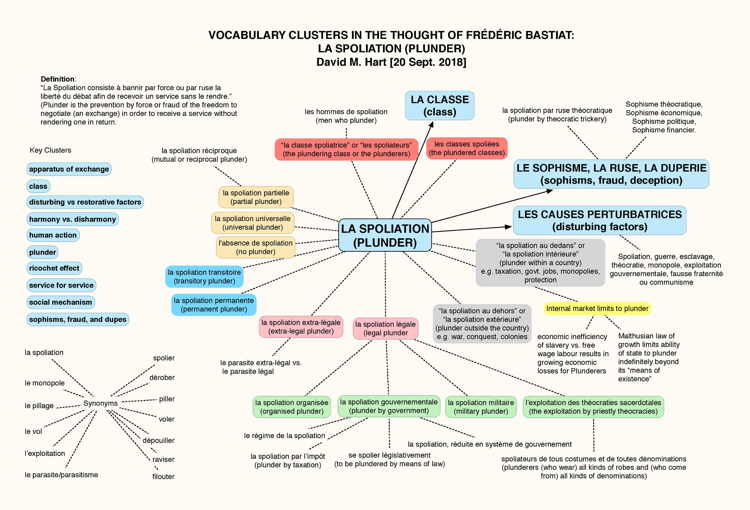

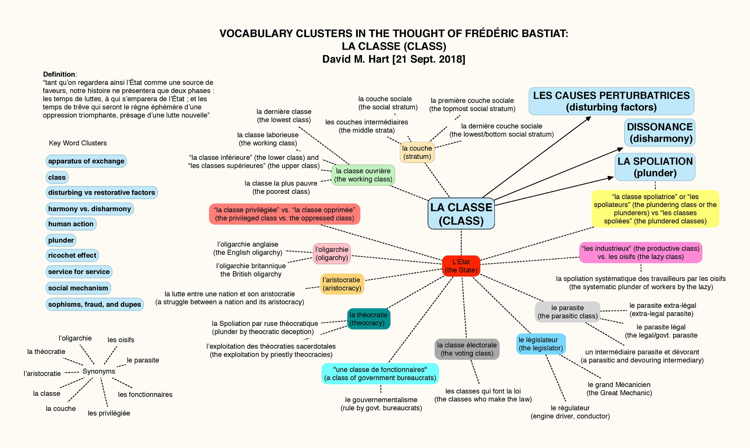

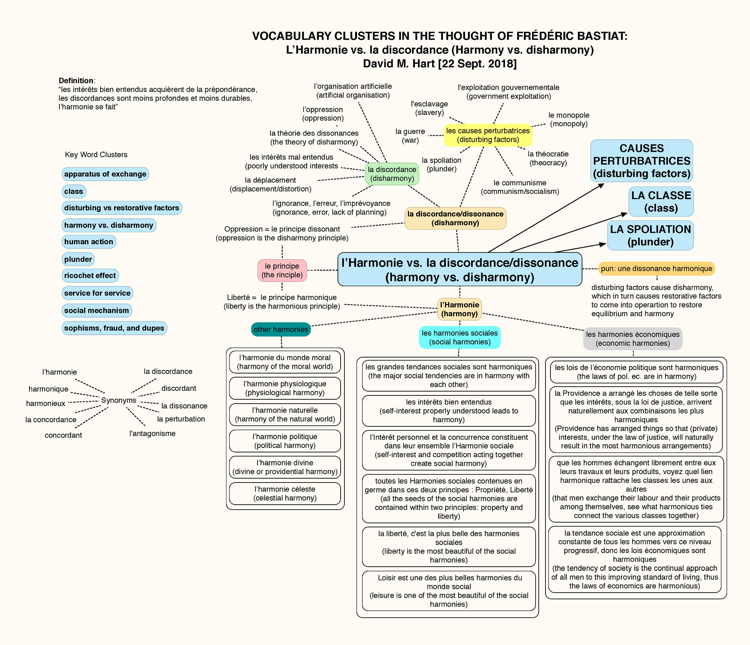

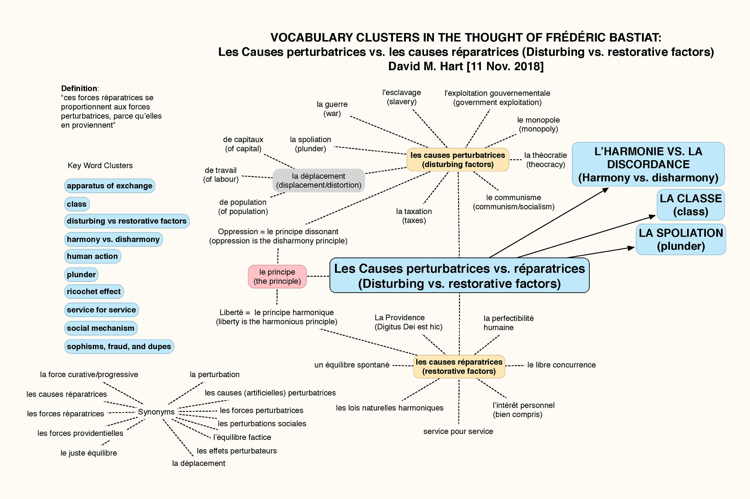

- Appendix: Vocabulary Clusters

- La Spoliation (Plunder)

- La Classe (Class)

- L’Harmonie vs. la Discordance/dissonance (Harmony vs. Disharmony)

- Les Cause perturbatrices vs. les Cause réparatrices (Disturbing vs. Restorative Factors)

- Bibliography

- Works by Bastiat

- Bastiat Resources Online

- Works by Bastiat

- Other Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Works by Bastiat

- Endnotes

Frédéric Bastiat on Plunder, Class and the State

| Tant qu’on regardera ainsi l’État comme une source de faveurs, notre histoire ne présentera que deux phases : les temps de luttes, à qui s’emparera de l’État ; et les temps de trêve qui seront le règne éphémère d’une oppression triomphante, présage d’une lutte nouvelle.(Letter to Mme Cheuvreux, 23 June 1850). | So, as long as we continue to consider the State to be a source of favours, our history will only alternate between two phases, the periods of struggle over who will seize control of the State, and the periods of truce which will be the fleeting reign of the oppressor who was victorious, (and) the harbinger of a new struggle (for power) (in the future). |

(Source: ) [1]

Introduction↩

Frédéric Bastiat’s unwritten “History of Plunder” ranks alongside Lord Acton’s never written (and possibly unwritable) “History of Liberty” and Murray Rothbard’s third volume of his “History of Economic Thought” series as one of the greatest libertarian books never written. Had he lived to a ripe old age, instead of dying at the age of 49 from throat cancer, he might have finished his magnum opus Economic Harmonies and lived to complete his history of plunder. It should be noted that Karl Marx, the founder of Marxism, published the first volume of his magnum opus, Das Capital (1867), when he too was 49 years old but lived another 15 years during which time he wrote but never completed another two large volumes. [2] Given the chance, Bastiat might well have fulfilled his great promise as an economic theorist and historian and have become “the Karl Marx” of the 19th century classical liberal movement. How history might have been different if he had! Or maybe not, who can tell?

In the eight years Bastiat was active as a writer and a politician (1843-1850) [3] he produced six large volumes of letters, pamphlets, articles, and books. What emerges from a chronological examination of his writings is his gradual realization that the State is a vast machine which is purposely designed to take the property of some people without their consent and to transfer it to other people. The word which he uses with increasing frequency in this period to describe the actions of the State is “la spoliation” (plunder), although he also uses words like “le parasite”, “le viol” (rape), “le vol” (theft), and “le pillage” which are equally harsh and to the point. [4] In his scattered writings on State plunder written before the 1848 Revolution he identifies the particular groups which have had access to State power at different times in history in order to plunder ordinary people, these were warriors, slave owners, the Catholic Church, and more recently commercial and industrial monopolists. Each of these groups and the particular way in which they used State power to exploit ordinary people for their own benefit were to have a separate section in his planned “History of Plunder.” Were he to have defined the State before the 1848 Revolution it might well have been along these lines: “The state is the mechanism by which a small privileged group of people live at the expense of everyone else.” He called this small privileged group “la classe spoliatrice” (the plundering class) and those they plundered “les classes spoliées” (the plundered classes) thus putting himself squarely in the camp of those 19th century classical liberals who had developed their own theory of class some decades before Marx developed his. [5]

But the outbreak of Revolution in February 1848 in Paris changed the equation dramatically which forced Bastiat to change his analysis of plunder and the State. Before the Revolution, small privileged minorities were able to seize control of the State and plunder the majority of the people for their own benefit - what he termed “la spoliation partielle” (partial plunder). [6] For example, slave owners were able to exploit their slaves, aristocratic landowners were able to exploit their serfs, privileged monopolists were able to exploit their customers, and thus it made some kind of brutal sense for a small minority to plunder and loot the majority. In Bastiat’s theory before 1848 he identified the special interests who benefited from their access to the State and exposed them to the public via his journalism, often with withering criticism and satire, such as the landed elites who benefited from tariff protection, the industrial elites who benefited from monopolies and state subsidies, and the monarchy and the aristocratic elites who benefited from access to jobs in the government and the army.

The rise to power of socialist groups in 1848 (such as the “Montagne” or Mountain faction led by Ledru-Rollin) meant that larger groups, perhaps a majority of the voters if the socialist groups were successful in winning office, were now trying to use the same methods used by these privileged minorities but now for the benefit of “everyone” instead of a narrow elite - or, what he termed “la spoliation universelle” (universal plunder) or “la spoliation réciproque” (reciprocal or mutual plunder). [7] The problem as Bastiat saw it, was that it was theoretically and practically impossible for the majority to live at the expense of the majority. Somebody had eventually to pay the bills and the majority could not do this if it was paying the taxes as well as receiving the “benefits” of state handouts, with the State and its employees (les classes de fonctionnaires) taking its customary cut along the way. This conundrum led him to put forward his famous definition of the State in mid-1848: “L’État, c’est la grande fiction à travers laquelle tout le monde s’efforce de vivre aux dépens de tout le monde” (The state is the great fiction by which everyone endeavours to live at the expense of everyone else.) [8] Bastiat’s political strategy now had to change to trying to convince ordinary workers that promises of government jobs, state-funded unemployment relief, and price controls were self-defeating and ultimately impossible to achieve.

Bastiat was not able to win this intellectual or political debate because of his death in December 1850 and the socialist forces were ultimately defeated temporarily by a combination of military and police oppression as the “Party of Order” supported the rise of Louis Napoleon who quickly designated himself as the “Prince-President” of France and then appointed himself Emperor Napoleon III. However, the core weakness of the welfare state was clearly identified by Bastiat in 1848 and we continue to see the consequences of its economic contradictions and possible collapse in the present day.

With this broader picture in mind I would like to examine Bastiat’s theory of plunder and the class analysis which he developed from this, so we can see more clearly what he had in mind and appreciate the power of his analysis.

Bastiat’s Writings on Class and Plunder↩

Unfortunately, Bastiat’s ideas remain scattered throughout many of his essays and articles which were written between 1845 and 1850. The most important of these works (some 16 in number) where he provides more extensive discussion of the nature of class and plunder are the following (listed in chronological order), six of which come from the Economic Sophisms (1846, 1848), three from Economic Harmonies (1850, 1851), two from What is Seen and What is Not Seen (1850), and five other essays and articles:

- the “Introduction” to Cobden and the League (July 1845), [9] in which he discusses the English “oligarchy” which benefited from the system of tariffs which Cobden and his Anti-Corn Law League were trying to get repealed; the strategy they adopted was to identify the key source of income for the ruling oligarchy (tariffs on imported food) and to eliminate it (by opening the economy to free trade) and thus weaken the oligarchy’s political and economic power

- ES1 “Conclusion” to Economic Sophisms 1 (dated November 1845), [10] where he reflects on the use of force throughout history to oppress the majority, and the part played by “sophistry” (ideology and false economic thinking) to justify this

- ES2 9 “Theft by Subsidy” (JDE, January 1846), [11] where he insists on the need to use “harsh language” - like the word “le vol” (theft) - to describe the policies of governments which give benefits to some at the expence of others [12]

- ES3 6 “The People and the Bourgeoisie” (LE, 23 May 1847), [13] in which he rejects the idea that there is an inevitable antagonism (“la guerre sociale” (war between social groups or classes)) between the people and the bourgeoisie, while there is one between the people and the aristocracy; he also introduces the idea of “la classe électorale” (the electoral classe) [14] which controls the French state by severely limiting the right to vote to the top 1 or 2% of the population

- ES2 1 “The Physiology of Plunder” (c. 1847), [15] which is his first detailed discussion of the nature of plunder (which is contrasted with “production”) and his historical progression of stages through which plunder has evolved from war, slavery, theocracy, and monopoly

- ES2 2 “Two Moral Philosophies” (c. 1847), [16] where he distinguishes between religious moral philosophy, which attempts to persuade the men who live by plundering others (e.g. slave owners and protectionists) to voluntarily refrain from doing so, and economic moral philosophy, which speaks to the victims of plundering and urges them to resist by understanding the true nature of their oppression and making it “increasingly difficult and dangerous” for their oppressors to continue exploiting them

- ES3 14 “Anglomania, Anglophobia” (c. 1847), [17] where he discusses “La grande lutte entre la démocratie et l’aristocratie, entre le droit commun et le privilége" (the great conflict between democracy and aristocracy, between common law and privilege) [18] and how this class conflict is playing out in England; it is a continuation of his analysis of the British “oligarchy” which he began in the Introduction to Cobden and the League.

- “Justice and Fraternity” (15 June 1848, JDE), [19] where Bastiat first used the terms “la spoliation extra-légale” (extra-legal plunder) and “la spoliation légale” (legal plunder); he describes the socialist state as “un intermédiaire parasite et dévorant” (a parasitic and devouring intermediary) which embodies “la Spoliation organisée” (organised plunder). [20]

- “Property and Plunder” (JDD, 24 July 1848), [21] in the “Fifth Letter” Bastiat talks about how transitory plunder gradually became “la spoliation permanente” (permanent plunder) [22] when it became organised and entrenched by the state

- the “Conclusion” to the first edition of Economic Harmonies (late 1849), [23] where he sketches what his unfinished book should have included, such as the opposite of the factors leading to “harmony”, namely “les dissonances sociales” (the social disharmonies) [24] such as plunder and oppression; or what he also calls “les causes perturbatrices” (disturbing factors); [25] here he concentrates on theocratic and protectionist plunder

- “Plunder and Law” (JDE, 15 May 1850), [26] where he addresses the protectionists who have turned the law into a “sword” or “un instrument de Spoliation” (a tool of plunder) [27] which the socialists will take advantage of when they get the political opportunity to do so

- “The Law” (June 1850), [28] Bastiat’s most extended treatment of the natural law basis of property and how it has been “perverted” by the plunderers who have seized control of the state, where the “la loi a pris le caractère spoliateur” (the law has taken on the character of the plunderer); [29] there is a longer discussion of “legal plunder”; and he reminds the protectionists that the system of exploitation they had created before 1848 has been taken over, first by the socialists and soon by the Bonapartists, to be used for their purposes thus creating a new form of plundering by a new kind of class rule by “gouvernementalisme” (government bureaucrats). [30]

- WSWNS Chap. 3 “Taxes” (July 1850), [31] on the conflict between the tax payers and the payment of civil servants’ salaries whom he likens to so many thieves, who provide no (or very little) benefit in return for the money they receive, and thus create a form of “legal parasitism” [32]

- WSWNS Chap. 6 “The Middlemen” (July 1850), where he describes the government’s provision of some services as a form of “dreadful parasitism” [33]

- Economic Harmonies, part 2, chapter 17, “Private Services, Pubic Services” (published posthumously in 1851), [34] an examination of the extent to which “public services” are productive or plunderous; he discusses how in the modern era “la spoliation par l’impôt s’exerce sur une immense échelle” (plunder by means of taxation is excercised to a high degree), [35] but rejects the idea that they are plunderous “par essence” (by their very nature); beyond a very small number of limited activities (such as public security, managing public property) the actions of the state are “autant d’instruments d’oppression et de spoliation légales” (only so many tools of oppression and legal plunder); [36]he warns of the danger of the state serving the private interests of “les fonctionnaires” (state functionaries) who become plunderers in their own right; [37] the plundered class is deceived by sophistry into thinking that that they will benefit from whatever the plundering classes seize as a result of the “ricochet” or trickle down effect [38]: as they spend their ill-gotten gains

- Economic Harmonies, part 2, chapter XIX “War”. [39] In this very rough and unfinished draft chapter Bastiat returns to the ideas of Charles Comte and Charles Dunoyer concerning how one's method of making a living (productive work or "industrialism" vs. violence, theft, fraud, and war) influences a county's culture and mores. The essential contrast is between two different methods of working and getting wealth, that of "le chasseur, le pêcheur, le pasteur, l'agriculteur, le fabricant, le négociant, l'ouvrier, l'artisan, le capitaliste" (the hunter, the fisherman, the herder, the farmer, the builder, the merchant, the worker, the artisan, the capitalist)) on the one hand, and that of "le fonctionnaire, le soldat, le magistrat " (the government bureaucrat, the solder, the magistrate) and perhaps that of "le prêtre" (the priest) as well, on the other hand. [40] He reminds the reader that ancient civilisations which are much admired (such as the Egyptian and the Greek and Roman) were run by people who benefitted from the exploited labour of others (namely slaves) and as a result, their cultures were greatly influenced by how the different groups earned (or did not earn) their livings. In the end he believes, society as a whole is not made better off when it is based upon such a system of plunder and exploitation. Although the chapter is left unfinished he appears to be gearing up to a more detailed discussion of "la spoliation par voie de guerre" (plunder by means of war) [41] and the impact this has on the beliefs people hold about the relative merits of the value of "la vie militaire avant la vie laborieuse, la guerre avant le travail, la spoliation avant la production" (military life above that of the working life, war above labour, plunder above production). [42]

The Origin and Foundation of Bastiat’s Theory of Plunder and Class↩

The basis for Bastiat’s theory of class was the notion of plunder which he defined as the taking of another person’s property without their consent by force or fraud. Those who lived by plunder constituted “les spoliateurs” (the plunderers) or “la classe spoliatrice” (the plundering class). Those whose property was taken constituted “les spoliés” (the plundered) or “les classes spoliées” (the plundered classes). Before the Revolution of February 1848 Bastiat used the pairing of “les spoliateurs” (the plunderers) and “les spoliés” (the plundered) as for example in the Introduction to his book on Cobden et la Ligue (1845) where he spoke of "un petit nombre de spoliateurs et un grand nombre de spoliés" (a small number of plunderers and a large number of (the) plundered). [43] After the Revolution he preferred the pairing of “la classe spoliatrice” (the plundering class) and “les classes spoliées” (the plundered classes) which is one indication of how deeply the events of 1848 and the rise of socialism affected his thinking. [44]

The intellectual origins of this way of thinking can be traced back to the innovative ideas of Jean-Baptiste Say concerning “productive” and “unproductive” labour which he developed in his Treatise of Political Economy (1803) [45] and the work of two lawyers and journalists who were inspired by Say’s work during the Restoration, Charles Comte (1782-1837) [46] and Charles Dunoyer (1786-1862). [47] Comte and Dunoyer took the idea that those who were engaged in productive economic activity of any kind, or what they called “l’industrie”, creating either goods or services, comprised a class which they called “les industrieux” (industrious or productive workers). Dunoyer in particular developed from these ideas an “industrialist” theory of history and class analysis which was very influential among French liberals leading up to 1848. Bastiat’s reading of these three authors during the 1820s and 1830s laid the theoretical foundation of his own thinking about productive and unproductive labour, the nature of exploitation or plunder, and the system of class rule which was created when the unproductive class used their control of the state to live off the productive labour of the mass of the people. [48]

Bastiat took the ideas of Say, Comte, and Dunoyer about plunder and the plundering class which he had absorbed in his youth and developed them further during his campaign against protectionism between early 1843 and the beginning of 1848. Thus, it is not surprising that his definition originally began as an attempt to explain how an “oligarchy” of large landowners and manufacturers exploited consumers by preventing them from freely trading with foreigners and forcing them to buy from more expensive state protected local producers. This perspective is clearly shown in Bastiat’s lengthy introduction to his first book on Cobden and the League which was published by Guillaumin in July 1845. [49] He wanted to apply his analysis of the English class system of an oligarchy protected by tariffs to France and to adapt the strategies used by Cobden and the Anti-Corn Law League to France which he attempted to do, unsuccessfully as it turned out, between 1846 and early 1848. He returned to the English class system in the essay “Anglomania, Anglophobia” (c. 1847) [50] where he discusses “the great conflict between democracy and aristocracy, between common law and privilege” and how this class conflict was playing out in England. In “The People and the Bourgeoisie” (May, 1847) he also analysed the class relationship between the aristocracy and the nation in France which he viewed as having such “an undeniable hostility of interests” that it would lead inevitably to conflict of some kind, such as “la guerre sociale” (class or social war). [51]

He later expanded his understanding of class and plunder to include other forms of exploitation such as ancient slavery, medieval feudalism, oppression by the Catholic Church, and in his own day financial and banking privileges, as well as redistributive socialism which began to emerge during 1848. We can see this clearly in the chapter “The Physiology of Plunder” which opened the second series of Economic Sophisms (published in January 1848 but written in late 1847) where he defined plunder in the following rather abstract way using his terminology of any exchange as the mutual exchange of “service for service”: [52]

| La véritable et équitable loi des hommes, c’est : Échange librement débattu de service contre service. La Spoliation consiste à bannir par force ou par ruse la liberté du débat afin de recevoir un service sans le rendre. | The true and just law governing man is “The freely negotiated exchange of one service for another.” Plunder consists in banishing by force or fraud the freedom to negotiate in order to receive a service without offering one in return. |

Thus, the slave was plundered by the slave owner because the violent capture and continued imprisonment of the slave did not allow any free negotiation with the slave owner over the terms of contract for doing the labour which the slave was forced to do. Similarly, the French manufacturer protected by a tariff or ban on imported foreign goods prevented the domestic purchaser from freely negotiating with a Belgian or English manufacturer to purchase the good at a lower price.

What turned what might have been just a one-off act of violence against a slave or a domestic consumer into a system of class exploitation and rule was its regularisation, systematisation, and organisation by the state, or what he termed “la spoliation organisée” (organised plunder). [53] All societies had laws which prohibited theft and fraud by some individuals against other individuals. When these laws were broken by thieves, robbers, and conmen we have an example of what Bastiat called “la spoliation extra-légale” (plunder which takes place outside the law) [54] and we expect the police authorities to attempt to apprehend and punish the wrong-doers. However, all societies have also established what Bastiat termed “la spoliation légale” (plunder which is done with the sanction or protection of the law) or “la spoliation gouvernementale” (plunder by government itself). [55] Those members of society who are able to control the activities of the state and its legal system can get laws passed which provide them with privileges and benefits at the expense of ordinary people. The state thus becomes what Bastiat termed “la grande fabrique de lois” (the great law factory) [56] which makes it possible for the plundering class to use the power of the state to exploit the plundered classes in a systematic and seemingly permanent fashion. [58]

Bastiat was never able to gather together all his thoughts on the nature of plunder and the plundering classes and complete his planned book on “A History of Plunder.” According to Paillottet, Bastiat stated on the eve of his death his conviction about the need for such a history: [59]

| Un travail bien important à faire, pour l’économie politique, c’est d’écrire l’histoire de la Spoliation. C’est une longue histoire dans laquelle, dès l’origine, apparaissent les conquêtes, les migrations des peuples, les invasions et tous les funestes excès de la force aux prises avec la justice. De tout cela il reste encore aujourd’hui des traces vivantes, et c’est une grande difficulté pour la solution des questions posées dans notre siècle. On n’arrivera pas à cette solution tant qu’on n’aura pas bien constaté en quoi et comment l’injustice, faisant sa part au milieu de nous, s’est impatronisée dans nos mœurs et dans nos lois. | A very important task to be done for political economy is to write the history of plunder. It is a long history in which, from the outset, there appeared conquests, the migrations of peoples, invasions, and all the disastrous excesses of force in conflict with justice. Living traces of all this still remain today and cause great difficulty for the solution of the questions raised in our century. We will not reach this solution as long as we have not clearly noted in what and how injustice, when making a place for itself amongst us, has gained a foothold in our customs and our laws. |

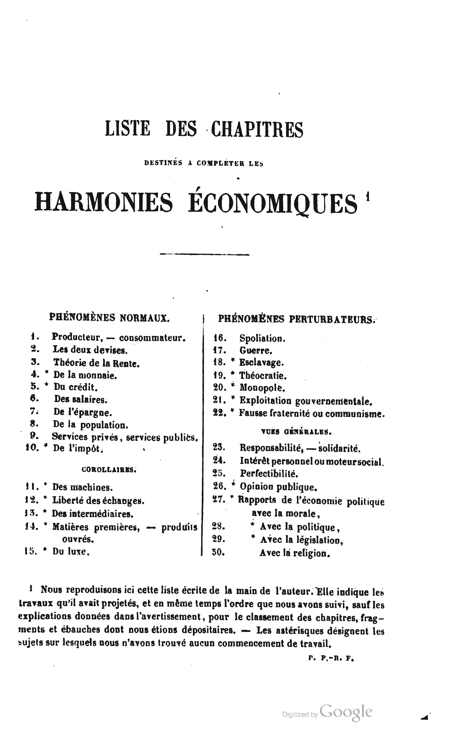

We know Bastiat had plans to apply his class analysis to European history going back to the ancient Romans. When working through his papers in preparation for publishing the second part of Economic Harmonies his friend and literary executor Prosper Paillottet states that Bastiat had sketched out in seven proposed chapters, called “Phénomènes perturbatrices” (Disturbing Phenomena), what would in effect have been his History of Plunder: Chapter 16. Plunder, 17. War, 18. Slavery, 19. Theocracy, 20. Monopoly, 21. Government Exploitation, 22. False Fraternity (Brotherhood) or Communism. This list was included in the second expanded edition of Economic Harmonies (1851) which “the friends of Bastiat” (Prosper Paillottet and Roger de Fontenay) put together from his papers after his death. [60]

Bastiat's Theory of Plunder and Class↩

An Outline of Bastiat’s Theory of Class and Plunder

The following definition and summary of what he meant by plunder has been compiled from the first chapter of his second series of Economic Sophisms which appeared in early 1848, “The Physiology of Plunder” and is his most extended treatment of the topic (these are Bastiat’s own words but I have reordered them for the sake of clarity):

There are only two ways of acquiring the things that are necessary for the preservation, improvement and betterment of life: PRODUCTION and PLUNDER. (Il n’y a que deux moyens de se procurer les choses nécessaires à la conservation, à l’embellissement et au perfectionnement de la vie : la Production et la Spoliation.)

… PLUNDER is exercised on too a vast scale in this world, that it is too universally woven into all major human events, for any social science, above all Political Economy, to feel justified in disregarding it. (la Spoliation s’exerce dans ce monde sur une trop vaste échelle, qu’elle se mêle trop universellement à tous les grands faits humains pour qu’aucune science sociale, et l’Économie politique surtout, puisse se dispenser d’en tenir compte.)

What separates the social order from a state of perfection (at least from the degree of perfection it can attain) is the constant effort of its members to live and progress at the expense of one another. (Ce qui sépare l’ordre social de la perfection (du moins de toute celle dont il est susceptible), c’est le constant effort de ses membres pour vivre et se développer aux dépens les uns des autres.)

When PLUNDER has become the means of existence of a large group of men mutually linked by social ties, they soon contrive to pass a law that sanctions it, and a moral code that glorifies it. (Lorsque la Spoliation est devenue le moyen d’existence d’une agglomération d’hommes unis entre eux par le lien social, ils se font bientôt une loi qui la sanctionne, une morale qui la glorifie.)

. First of all, there is WAR... Then there is SLAVERY. ... Next comes THEOCRACY ... Lastly, there is MONOPOLY. (C’est d’abord la Guerre. … C’est ensuite l’Esclavage. … Vient la Théocratie. … Enfin arrive le Monopole.)

The true and just law governing man is “The freely negotiated exchange of one service for another.” Plunder consists in banishing by force or fraud the freedom to negotiate in order to receive a service without offering one in return. Plunder by force is exercised as follows: People wait for a man to produce something and then seize it from him at gun point. This is formally condemned by the Ten Commandments: Thou shalt not steal. When it takes place between individuals, it is called theft and leads to prison; when it takes place between nations, it is called conquest and leads to glory. (La véritable et équitable loi des hommes, c’est : Échange librement débattu de service contre service. La Spoliation consiste à bannir par force ou par ruse la liberté du débat afin de recevoir un service sans le rendre. La Spoliation par la force s’exerce ainsi : On attend qu’un homme ait produit quelque chose, qu’on lui arrache, l’arme au poing. Elle est formellement condamnée par le Décalogue : Tu**ne prendras point. Quand elle se passe d’individu à individu, elle se nomme vol et mène au bagne ; quand c’est de nation à nation, elle prend nom conqu**ête et conduit à la gloire.)

Plunder consists in banishing by fraud or force the freedom to negotiate in order to receive a service without offering one in return. (La Spoliation consiste à bannir par force ou par ruse la liberté du débat afin de recevoir un service sans le rendre.)

From this and other scattered writings on the subject one can reconstruct an outline of what Bastiat’s theory of class and plunder might have looked like.

I would like to emphasize a few key points in this definition to help us better understand Bastiat’s perspective:

- he believes in an absolute moral philosophy based upon natural law

- these natural laws are partly discovered through the scientific, empirical observation of human societies (economics and history) and partly through divine revelation (Bastiat’s deism and his moral Christianity)

- this moral philosophy applies to all human beings without exception

- he believes that there are only two ways by which wealth (property) can be acquired: firstly by voluntary individual activity and by freely negotiated exchange with others (“service for service”), by individuals called the “les Producteurs" (Producers); secondly, by theft (coercion or fraud) by a third party, also called “les Spoliateurs" (the Plunderers)

- the existence of plunder is a scientific, empirical matter which is revealed by the study of history (this was to be his great next unfulfilled research project) [61]

- the Plunderers have historically organised themselves into States and have tried to make their activities an exception to the universal moral principles by introducing laws that “sanction” plunder and a moral code that “glorifies” it (“une loi qui la sanctionne, une morale qui la glorifie”) [62]

- the Plunderers also deceive their victims by means of “la ruse” (trickery, deception, fraud) and the use of “sophisms” and outright fallacies to justifying and disguise what they are doing

The Moral Foundations of Bastiat’s Theory of Plunder: “Thou shalt not steal.”

As a supporter of the idea of natural law and natural rights, Bastiat believed that there were universal moral principles which could be identified and elaborated by human beings and which had a universal application. In other words, there were not two moral principles in operation, one for the sovereign power and government officials and another for the rest of mankind. One of these universal principles was the notion of an individual’s right to own property, along with the corresponding injunction not to violate an individual’s right to property by means of force or fraud. In the Christian world the injunction was expressed in the Ten Commandments, particularly “Thou shalt not steal” [63] and, since there was no codicil attached to Moses’ tablets exempting monarchs, aristocrats, or government employees, Bastiat was prepared to argue that this moral commandment had universal applicability.

According to Bastiat there were two ways in which wealth could be acquired, either by voluntary production and exchange or by coercion: [64]:

| Il n’y a que deux moyens de se procurer les choses nécessaires à la conservation, à l’embellissement et au perfectionnement de la vie : la Production et la Spoliation. | There are only two ways of acquiring the things that are necessary for the preservation, improvement and betterment of life: PRODUCTION and PLUNDER. |

And a bit further into the essay he elaborates as follows, with his definition of plunder (in italics): [65]

| La véritable et équitable loi des hommes, c’est : Échange librement débattu de service contre service. La Spoliation consiste à bannir par force ou par ruse la liberté du débat afin de recevoir un service sans le rendre | The true and just law governing man is “The freely negotiated exchange of one service for another.” Plunder consists in banishing by fraud or force the freedom to negotiate in order to receive a service without offering one in return. |

| La Spoliation par la force s’exerce ainsi : On attend qu’un homme ait produit quelque chose, qu’on lui arrache, l’arme au poing. | Plunder by force is exercised as follows: People wait for a man to produce something and then seize it from him at gun point. |

| Elle est formellement condamnée par le Décalogue : Tu ne prendras point. | This is formally condemned by the Ten Commandments: Thou shalt not steal. |

| Quand elle se passe d’individu à individu, elle se nomme vol et mène au bagne ; quand c’est de nation à nation, elle prend nom conquête et conduit à la gloire. | When it takes place between individuals, it is called theft and leads to prison; when it takes place between nations, it is called conquest and leads to glory. |

It is not certain when these words were written as neither Bastiat nor his editor Paillottet provide that information. It is most likely that they were written specifically for the the Second Series of the Economic Sophisms which were published in January 1848. In an earlier article published in January 1846, “Theft by Subsidy”, Bastiat responded to criticism of his First Series of Economic Sophisms which had just appeared in print that they were “too theoretical, scientific, and metaphysical.” His response was to make sure that his future writings could not be accused of this again, which he did by peppering their pages with “une explosion de franchise” (an explosion of plain speaking.” By this he meant that he would use very blunt, direct, even “brutal” language, such as “theft”, “pillage”, “plunder,” and “parasitism,” when describing the activities undertaken by the State which were accepted by most people as perfectly normal and “legal”. [66] So, in many of the essays written in 1846 and 1847 which were to end up in future editions of the Economic Sophisms Bastiat wanted to make it perfectly clear what he thought the state was doing by regulating and taxing French citizens and to call these activities by their “real name”, namely theft and plunder. As he notes in an aside: [67]

| Franchement, bon public, on te vole. C’est cru, mais c’est clair. | Frankly, my good people, you are being robbed. That is plain speaking but at least it is clear. |

| Les mots vol, voler, voleur, paraîtront de mauvais goût à beaucoup de gens. Je leur demanderai comme Harpagon à Élise : Est-ce le mot ou la chose qui vous fait peur ? | The words, theft, to steal and thief seem to many people to be in bad taste. Echoing the words of Harpagon to Elise, I ask them: Is it the word or the thing that makes you afraid? |

He cites the Ten Commandments, [68] the French Penal Code, and the Dictionary of the French Academy to define what theft is as clearly as he can and to note its universal prohibition. According to these definitions, in Bastiat’s mind, the policies of the French government were nothing more than “le vol à la prime” (theft by subsidy,” “le vol au tariff (theft by Customs duties/tariffs), “le vol organisé” (organised theft), “le vol réciproque” (reciprocal or mutual theft) of all Frenchmen via subsidies and protective duties, and so on. [69] Altogether they made up an entire system of “plunder” which had been evolving for centuries and which he had wanted to make the topic of his book on “A History of Plunder”.

Therefore, because of the ubiquity of plunder in human history it was essential for political economy to take it into account when discussing the operation of the market and its “causes perturbatrices” (disturbing factors): [70]

| Quelques personnes disent : La Spoliation est un accident, un abus local et passager, flétri par la morale, réprouvé par la loi, indigne d’occuper l’Économie politique. | Some people say: “PLUNDER is an accident, a local and transitory abuse, stigmatized by moral philosophy, condemned by law and unworthy of the attentions of Political Economy.” |

| Cependant, quelque bienveillance, quelque optimisme que l’on porte au cœur, on est forcé de reconnaître que la Spoliation s’exerce dans ce monde sur une trop vaste échelle, qu’elle se mêle trop universellement à tous les grands faits humains pour qu’aucune science sociale, et l’Économie politique surtout, puisse se dispenser d’en tenir compte. | But whatever the benevolence and optimism of one’s heart one is obliged to acknowledge that PLUNDER is exercised on too a vast scale in this world, that it is too universally woven into all major human events, for any social science, above all Political Economy, to feel justified in disregarding it. |

“La Ruse” (Fraud, Trickery) and Legal Plunder

A key feature of plunder which distinguishes it from the acquisition of wealth by voluntary exchange is a combination of the the use of violence and what he called “la ruse” (fraud or trickery). Within the category of “plunder” there are two main types which interested Bastiat: “la spoliation extra-légale” (plunder outside the law, or “illegal” plunder) which was undertaken by thieves, robbers, and highway men and which was prohibited by law; the second type of plunder was what Bastiat called “la spoliation légal” (legal plunder) which was usually undertaken by the state under the protection of the legal system which exempted sovereigns and government officials from the usual prohibition of taking other people’s property by force. Illegal plunder was less interesting to Bastiat as it was universally condemned and quite well understood by legal theorists and economists. Instead, Bastiat concentrated in his scattered writings on the latter form, legal plunder, as it was hardly recognized at all by economists as a problem in spite of the fact that it had existed on a “un trop vaste échelle” (a vast scale) throughout history and was one its driving forces. As he noted in his “final and important aperçu” which ended the “Conclusion” to Economic Sophisms I: [71]

| La force appliquée à la spoliation fait le fond des annales humaines. En retracer l’histoire, ce serait reproduire presque en entier l’histoire de tous les peuples : Assyriens, Babyloniens, Mèdes, Perses, Égyptiens, Grecs, Romains, Goths, Francs, Huns, Turcs, Arabes, Mongols, Tartares, sans compter celle des Espagnols en Amérique, des Anglais dans l’Inde, des Français en Afrique, des Russes en Asie, etc., etc. | Force used for plunder forms the bedrock upon which the annals of human history rest.Retracing its history would be to reproduce almost entirely the history of every nation: the Assyrians, the Babylonians, the Medes, the Persians, the Egyptians, the Greeks, the Romans, the Goths, the Francs, the Huns, the Turks, the Arabs, the Mongols, and the Tartars, not to mention the Spanish in America, the English in India, the French in Africa, the Russians in Asia, etc., etc. |

Within the category of “legal plunder” Bastiat further distinguished between more general types of plunder and more specific kinds which depended upon how and where the plundering took place and who was the beneficiary. The general types of plunder included the following:

- “la spoliation permanente” (permanent plunder) [72]

- “la spoliation organisée” (organized or institutionalized plunder) [73]

- “la spoliation gouvernementale” (government organised plunder) [74]

Among the more specific kinds of plunder he referred to:

- “la spoliation au dedans” [75] or “la spoliation intérieure” (plunder within a country) [76] which took the form of taxation government jobs, monopolies and protection from competition

- “la spoliation au dehors” (plunder outside the country) [77] which took the form of war, conquest, and colonies

- “la spoliation militaire” (military plunder) [78] which took the form of expenditure on the military beyond the minimum needed for national defense, a large standing army in peace time, the building of expensive and unnecessary fortifications (like Theirs’ fortified wall around Paris which was built between 1841 and 1844 just before Bastiat’s arrival in the city) [79]

- “theocratic plunder” (although Bastiat did not use this specific term but closely related expressions which will be explained below) [80]

In the essay “The Physiology of Plunder” which opened Economic Sophisms II Bastiat sketches out the main types of plunder which had emerged in history: war, slavery, theocracy, and monopoly. Historically, societies and their ruling elites which lived from plunder had evolved through alternating periods of conflict, where the elites fought for control of the state, and periods of “truce”, where plunder became regularized until another rivalrous group of plunderers sought control of the state. In a letter to Mme Cheuvreux (23 June 1850) Bastiat observes that: [81]

| tant qu’on regardera ainsi l’État comme une source de faveurs, notre histoire ne présentera que deux phases : les temps de luttes, à qui s’emparera de l’État ; et les temps de trêve qui seront le règne éphémère d’une oppression triomphante, présage d’une lutte nouvelle. | as long as we continue to regard the State as a source of favours, our history will be seen as having only two phases, the periods of conflict as to who will take control of the State and the periods of truce, which will be the transitory reign of a triumphant oppression, the harbinger of a fresh conflict. |

The immediate historical origins of the modern French state were the aristocratic and theocratic elites which rose to dominance in the Old Regime and which were challenged for control of the state first by liberal-minded reformers during the late Old regime (like Turgot) and the first phase of the Revolution (like Mirabeau and the Girondins group), then socialist-minded reformers under Robespierre during the Terror, and finally by the military elites under Napoleon. The defeat of Napoleon had led to a temporary return of the aristocratic and theocratic elites until they were again overthrown in another Revolution in February 1848, this time one in which Bastiat played an active role as an elected politician, journalist, and economic theorist. Bastiat examines in some detail the part played by the aristocracy in the essay “The People and the Bourgeoisie” (Libre-Échange, 22 May 1847), and he devotes a surprising amount of space to analyzing “theocratic plunder” in “The Physiology of Plunder” as his case study of the phenomenon. On the rise of the aristocracy he states: [82]

| Entre une nation et son aristocratie, nous voyons bien une ligne profonde de séparation, une hostilité irrécusable d’intérêts, qui ne peut manquer d’amener tôt ou tard la lutte. L’aristocratie est venue du dehors ; elle a conquis sa place par l’épée ; elle domine par la force. Son but est de faire tourner à son profit le travail des vaincus. Elle s’empare des terres, commande les armées, s’arroge la puissance législative et judiciaire, et même, pour être maîtresse de tous les moyens d’influence, elle ne dédaigne pas les fonctions ou du moins les dignités ecclésiastiques. Afin de ne pas affaiblir l’esprit de corps qui est sa sauvegarde, les priviléges qu’elle a usurpés, elle les transmet de père en fils par ordre de primogéniture. Elle ne se recrute pas en dehors d’elle, ou, si elle le fait, c’est qu’elle est déjà sur la voie de sa perte. | Between a nation and its aristocracy, we clearly see a deep dividing line, an undeniable hostility of interests, which sooner or later can only lead to strife/conflict. The aristocracy has come from outside; it has conquered its place by the sword and dominates through force. Its aim is to turn the work done by the vanquished to its own advantage. It seizes land, has armies at its disposal and arrogates to itself the power to make laws and expedite justice. In order to master all the channels of influence, it has not even disdained the functions, or at least the dignities, of the church. In order not to weaken the esprit de corps that is its lifeblood, it transmits the privileges it has usurped from father to son by way of primogeniture. The aristocracy does not recruit from outside its ranks, or if it does so, it is because it is already on the slippery slope. |

In the period in which he was living, the modern state had evolved to the point where a large, permanent, professional class of bureaucrats (les fonctionnaires) carried out the will of the sovereign power (which was King Louis Philippe during the July Monarchy 1830-1848, and then the “People” in the Second Republic following the Revolution of February 1848) to tax and regulate a growing part of the French economy. Three aspects of the growth of the state on which Bastiat had focussed his opposition in the mid- and late 1840s were protectionist tariffs on imported goods, taxation, and the government subsidization of the unemployed in the National Workshops during 1848. As the state expanded in size and the scope of its activities it began supplying an ever larger number of “public services” which were funded by the taxpayers. Bastiat had a stern view of these developments and viewed any “public service” which went beyond the bare minimum of police and legal services as “un funeste parasitisme” (a disastrous form of parasitism). [83]: Using his favourite stock figure of Jacques Bonhomme (Jack Everyman) in order to make his points Bastiat compares the “forced sale” of “public services” to the French people and the “legal parasitism” of the French bureaucracy to the actions of the petty thief who indulges in mere “illegal (or extralegal) parasitism” when he takes Jacques’ property by breaking into his house. [84]

Plunder by Direct or Indirect Violence

Bastiat believed that there were two types of plunder which had been practised by different groups (classes) over the centuries. The first type was plunder by naked force with no pretence being made by the plundering classes that this was in the interests of those being plundered. This describes the stages of tribal or city state warfare where a warrior class seized what it wanted by conquest and force of arms. The next stage in this type of plunder by naked force was slavery where a class of slave owners plundered the labour of those they had captured in war or bought in slave markets. In these two early stages the relationship between the classes is a simply binary one: there is the “la classe spoliatrice” (the plundering class) and “les classes spoliées” (the plundered classes) and resources flow from the latter to the former.

The second type of plunder involves a third party or class which acts as an enabler of the plundering class, because fraud (la ruse) and sophistry now become an important part of the class relationship of exploitation. Since the plundered class had become more vocal, the minority plundering class has to attempt to persuade the plundered class not to resist and this they do by employing fraud, trickery, and sophistry to persuade members of the plundered class that their situation is inevitable, commanded by God, part of the natural order of things, or even sometimes in their own interests. The task of persuasion falls to a new group from the intellectual or priestly class, who are paid by the plundering class to spread “sophisms” concerning the political and economic necessity of the current situation of plunder, in other words, to turn the plundered class into a class of “dupes” who do not see their chains. [85] Historically this task has fallen to the priesthood (under the system which Bastiat called “theocratic plunder”), and in the modern era to lawyers, economists, journalists, and lobby groups representing farming or manufacturing vested interests (under what might be called “monopolistic plunder” or “bureaucratic plunder”). Thus, society now has three groups which interact with each other: the plundering class, the plundered class, and a new group of “spinners of sophistry” who justify the system of plunder to those who are being plundered. It was the task of the economists like Bastiat to expose this relationship for what it is and to refute the sophisms used to keep the plundered class in their lowly position. The following gives a sense of Bastiat’s passion to refute the sophisms which made dupes of the plundered class: [86]

| Hercule ! qui étranglas Cacus, Thésée ! qui assommas le Minotaure, Apollon ! qui tuas le serpent Python, que chacun de vous me prête sa force, sa massue, ses flèches pour détruire le monstre qui, depuis six mille ans, arme les hommes les uns contre les autres. | Oh you, Hercules, who strangled Cacus! You, Theseus, who killed the Minotaur! You, Apollo, who killed Python the serpent! I ask you all to lend me your strength, your club and your arrows, so that I can destroy the monster that has been arming men against one another for six thousand years! |

| Mais, hélas ! il n’est pas de massue qui puisse écraser un sophisme. Il n’est donné à la flèche ni même à la baïonnette de percer une proposition. Tous les canons de l’Europe réunis à Waterloo n’ont pu effacer du cœur des peuples un principe ; et ils n’effaceraient pas davantage une erreur. Cela n’est réservé qu’à la moins matérielle de toutes les armes, à ce symbole de légèreté, la plume. | Alas, there is no club capable of crushing a sophism. It is not given to arrows, nor even to bayonets, to pierce a proposition. All the cannons in Europe gathered at Waterloo could not eliminate an entrenched idea from the hearts of nations. No more could they efface an error. This task is reserved for the least weighty of all weapons, the very symbol of weightlessness, the feather quill (pen). |

In Bastiat’s time, theocratic plunder had given way to a system of monopoly dominated by large landowners and manufacturers who sought trade restrictions, government subsides, monopolies in the home market, and other privileges. This alliance of vested interests emerged in the 1820s and 1830s when French tariff policy was revised and entrenched after the defeat of Napoleon. [87] The rise of socialist groups in the 1840s and especially in the early months of the 1848 Revolution suggested to Bastiat that another system of plunder might be possible, namely where “the people” themselves, or rather their representatives in the Chamber, erect a socialist or communist state in which “everyone endeavors to live at the expense of everyone else”, or in other words a system of “dérober mutuellement” (mutual stealing) or “la spoliation réciproque” (reciprocal plunder). This was of course Bastiat’s warning in his best known pamphlet “The State” (1st version appeared in June in Jacques Bonhomme, and revised and expanded version in JDD, September, 1848). [88]

On the eve of the February Revolution Bastiat attempted to refute the claim of the socialists that class conflict was inherent in the free market system, and that a “guerre sociale” (social or class war) between the “bourgeoisie” and the “people” was going to be fought with the victory going to “the people” or their elected representatives. [89] In “The People and the Bourgeoisie” (ES3 6 - May, 1847) Bastiat outlines the socialist theory of class war since the 1789 Revolution, some of which he was quite sympathetic to, and shows where he thinks the socialists have erred. According to the socialists, the first social war had been between the aristocracy and the rising bourgeoisie with the bourgeoisie winning in the revolution of 1789 and the second was the current struggle between “the people” and the bourgeoisie which would reach the point of revolution in the early months of 1848. But Bastiat argued that the socialists were wrong to think that this victory of “people” would bring an end to class conflict and social war. He predicted that, given the nature of politics and economic reality, a third social war would break out between the new ruling “people,” who had become the “new aristocracy” in the new socialist, “organized” state and economy, and the underclass of the poor and unemployed (the “beggars’) who had been excluded from politics [90] and suffered the most from economic privileges and high taxation. The cycle of “the ins” versus “the outs” for control of the state would continue, he thought, until the state no longer offered privileges and benefits to some at the expense of others. Only then would the plundering class disappear and the source of class conflict would evaporate.

In September 1847, Bastiat again replied to the socialists in a workers magazine l’Atelier (The Workshop). Here he took the socialist’s argument that there was in all modern societies "une classe privilégiée” (a privileged class) of property owners who exploited “une classe opprimée" (an oppressed class) of propertyless workers, and turned it on its head. Bastiat rejected the socialist notion that this antagonism was an inherent part of the free market system. What distinguished the privileged class from the oppressed class in his view was not who owned property and who did not, but who had access to the lawmaking powers of the state (or the “great law factory” as he called it) which were used to make some forms of property privileged monopolies. Thus the privileged class which had access to the state by means of the electoral laws enjoyed monopolies which were protected by the law from competition, whereas the oppressed class, which did not have access to “the law factory” but who did have a property in their own labor (“travail, qui est aussi une propriété” (labor which is also a form of property)), enjoyed no such privileges but in fact had to pay for those privileges enjoyed by those who controlled the law making body. From this Bastiat concluded that: [91]

| Une circonstance aggravante de cet ordre de choses, c’est que la propriété privilégiée par la loi est entre les mains de ceux qui font la loi. C’est même une condition, pour être admis à faire la loi, qu’on ait une certaine mesure de propriété de cette espèce. La propriété opprimée au contraire, celle du travail, n’a voix ni délibérative ni consultative. On pourrait conclure de là que le privilége dont nous parlons est tout simplement la loi du plus fort. | An aggravation which comes from this order of things is that property privileged by the law is in the hands of those who make the law. It is even a condition that in order to be allowed to make the law one has to have a certain amount of property of this kind (a reference to the property qualification in order to be able to vote). On the other hand, property which is oppressed, that is to say labour, does not have a deliberative or consultative voice in making the law. One could conclude from this that the privilege we are talking about is quite simply the law of the strongest. |

In the aftermath of the February 1848 Revolution Bastiat wrote to Mme Cheuvreux (January 1850) where he offered this analysis of the conflict between the people and the bourgeoisie based upon what he had experienced as a politician during the revolution (see the discussion above) [92]

| Je vois, en France, deux grandes classes qui, chacune, se subdivise en deux. Pour me servir de termes consacrés, quoique improprement, je les appellerai le peuple et la bourgeoisie. | In France, I can see two major classes, each of which can be divided into two. To use hallowed although inaccurate terms, I will call them the people and the bourgeoisie. |

| Le peuple, c’est une multitude de millions d’êtres humains, ignorants et souffrants, par conséquent dangereux ; comme je l’ai dit, il se partage en deux, la grande masse assez attachée à l’ordre, à la sécurité, à tous les principes conservateurs ; mais, à cause de son ignorance et de sa souffrance, proie facile des ambitieux et des sophistes ;cette masse est travaillée par quelques fous sincères et par un plus grand nombre d’agitateurs, de révolutionnaires, de gens qui ont un penchant inné pour le désordre, ou qui comptent sur le désordre pour s’élever à la fortune et à la puissance. | The people consist of a host of millions of human beings who are ignorant and suffering, and consequently dangerous. As I said, they are divided into two; the vast majority are reasonably in favor of order, security, and all conservative principles, but, because of their ignorance and suffering, are the easy prey of the ambitious and the sophists. This mass is swayed by a few sincere fools and by a larger number of agitators and revolutionaries, people who have an inborn attraction for disruption or who count on disruption to elevate themselves to fortune and power. |

| La bourgeoisie, il ne faudrait jamais l’oublier ; c’est le très-petit nombre ; cette classe a aussi son ignorance et sa souffrance, quoiqu’à un autre degré ; elle offre aussi des dangers d’une autre nature. Elle se décompose aussi en un grand nombre de gens paisibles, tranquilles, amis de la justice et de la liberté, et un petit nombre de meneurs. La bourgeoisie a gouverné ce pays-ci, comment s’est-elle conduite ? Le petit nombre a fait le mal, le grand nombre l’a laissé faire ; non sans en profiter à l’occasion. | The bourgeoisie, it must never be forgotten, is very small in number. This class also has its ignorance and suffering, although to a different degree. It also offers dangers, but of a different nature. It too can be broken down into a large number of peaceful, undemonstrative people, partial to justice and freedom, and a small number of agitators. The bourgeoisie has governed this country, and how has it behaved? The small minority did harm and the large majority allowed them to do this, not without taking advantage of this when they could. |

| Voilà la statistique morale et sociale de notre pays. | These are the moral and social statistics of our country. |

A Case Study of Plunder↩

Theocratic Plunder

The historical form of plunder which Bastiat discussed in most detail in his sketches and drafts was “theocratic plunder”, especially in ES2 1. “The Physiology of Plunder.” [93] It should be noted here that, even though he did not use the phrase “la spoliation théocratique” as one might have expected, he used very similar phrases such as the following: “l’exploitation des théocraties sacerdotales” (the exploitation by priestly theocracies) and “les spoliateurs de tous costumes et de toutes dénominations” (plunderers (who wear) all kinds of robes and (who come from) all kinds of denominations). [94]

Bastiat believed that the era of theocratic plunder provided a case study of how trickery and sophistic arguments could be used to ensure compliance with the demands of the plundering class. He argued that the rule of the Church in European history was one which he believed had practised plunder and deception “on a grand scale”. The Church had developed an elaborate system of theocratic plunder through its tithing of income and production and on top of this it created a system of “sophisme théocratique” (theocratic sophistry and trickery) based upon the notion that only members of the church could ensure the peoples’ passage to an afterlife. This and other theocratic sophisms created dupes of the ordinary people who duly handed over their property to the Church. Bastiat had no squabble with a church in which the priests were “the instrument of the religion”, but for hundreds of years religion had become instead “the instrument of its priest”: [95]

| Si, au contraire, la Religion est l’instrument du prêtre, il la traitera comme on traite un instrument qu’on altère, qu’on plie, qu’on retourne en toutes façons, de manière à en tirer le plus grand avantage pour soi. Il multipliera les questions tabou ; sa morale sera flexible comme les temps, les hommes et les circonstances. Il cherchera à en imposer par des gestes et des attitudes étudiés ; il marmottera cent fois par jour des mots dont le sens sera évaporé, et qui ne seront plus qu’un vain conventionalisme. Il trafiquera des choses saintes, mais tout juste assez pour ne pas ébranler la foi en leur sainteté, et il aura soin que le trafic soit d’autant moins ostensiblement actif que le peuple est plus clairvoyant. Il se mêlera des intrigues de la terre ; il se mettra toujours du côté des puissants à la seule condition que les puissants se mettront de son côté. En un mot, dans tous ses actes, on reconnaîtra qu’il ne veut pas faire avancer la Religion par le clergé, mais le clergé par la Religion ; et comme tant d’efforts supposent un but, comme ce but, dans cette hypothèse, ne peut être autre que la puissance et la richesse, le signe définitif que le peuple est dupe, c’est quand le prêtre est riche et puissant. | If, on the other hand, Religion is the instrument of the priest, he will treat it as some people treat an instrument that is altered, bent and turned in many ways so as to draw the greatest benefit for themselves. He will increase the number of questions that are taboo; his moral principles will bend according to the climate, men and circumstances. He will seek to impose it through studied gestures and attitudes; he will mutter words a hundred times a day whose meaning has disappeared and which are nothing other than empty conventionalism. He will peddle holy things, but just enough to avoid undermining faith in their sanctity and he will take care to see that this trade is less obviously active where the people are more keen-sighted. He will involve himself in terrestrial intrigue and always be on the side of the powerful, on the sole condition that those in power ally themselves with him. In a word, in all his actions, it will be seen that he does not want to advance Religion through the clergy but the clergy through Religion, and since so much effort implies an aim and as this aim, according to our hypothesis, cannot be anything other than power and wealth, the definitive sign that the people have been duped is when priests are rich and powerful. |

The challenge to this theocratic plundering came through the invention of the printing press which enabled the transmission of ideas critical of the power and intellectual claims of the Church and gradually led to the weakening of this form of organised, legal plunder. The Reformation, the Renaissance, and the Enlightenment gradually exposed the theocratic sophisms for what they really were - so many tricks, deceptions, lies, and contradictions - and many people were thus no longer willing to be the dupes of the Church.

In a similar manner, Bastiat thought, the modern bureaucratic and regulatory state of his day was, like the Church, based upon a mixture of outright violence and coercion on the one hand, and trickery and sophisms on the other. The violence and coercion came from the taxes, tariffs, and regulations which were imposed on taxpayers, traders, and producers; the ideological dimension which maintained the current class of plunderers came from a new set of political and economic sophisms which confused, mislead, and tricked a new generation of dupes into supporting the system. The science of political economy, according to Bastiat, was to be the means by which the economic sophisms of the present would be exposed, rebutted, and finally overturned, thus depriving the current plundering class of their livelihood and power: [96]

| J’en ai dit assez pour montrer que l’Économie politique a une utilité pratique évidente. C’est le flambeau qui, dévoilant la Ruse et dissipant l’Erreur, détruit ce désordre social, la Spoliation. | I have said enough to show that Political Economy has an obvious practical use. It is the flame that destroys this social disorder, Plunder, by unveiling Trickery and dissipating Error. |

| And in the following essay on “The Two Moralities” Bastiat contrasts the role of “religious morality” and “economic morality” in bringing about this change in thinking: [97]

| Que la morale religieuse touche donc le cœur, si elle le peut, des Tartuffes, des Césars, des colonistes, des sinécuristes, des monopolistes, etc. La tâche de l’économie politique est d’éclairer leurs dupes. | Let religious morality therefore touch the hearts of the Tartuffes, the Caesars, the colonists, sinecurists and monopolists, etc. if it can. The task of political economy is to enlighten their dupes. |

Bastiat was skeptical that religious morality would be successful in changing the views of those who held power because, as he pointed out on several occasions, how many times in history have ruling elites ever voluntarily given up their power and privileges? His preference was to strike at power from below by opening the eyes of the duped and tricked with the truths which political economy provided, to encourage doubt and mistrust in the justice of the rulers’ actions, and to mock the follies of the political elite by using sarcasm and “la piqûre du ridicule” (the sting of ridicule). [98] Hence, the urgent need for popularisations of economic thought like that of Harriett Martineau in England, [99] and Bastiat and Molinari in France. [100] Bastiat summed up the job of the political economists as: [101]

| dessillent les yeux des Orgons, déracinent les préjugés, excitent de justes et nécessaires défiances, étudient et exposent la vraie nature des choses et des actions. | opening the eyes of the Orgons, uprooting preconceived ideas, stimulating just and essential mistrust and studying and exposing the true nature of things and actions. |

The Malthusian Limits to State Plunder↩

Although the plundering elites were voracious in their appetite for the taxpayers’ property, Bastiat believed there was an upper limit to how much they could take because countervailing forces came into operation to check their growth. Firstly, widespread plunder and regulation of the economy hampered productive growth and made society less productive and prosperous than it might otherwise have been. A good example of this Bastiat thought was evidenced by slave societies where the productivity of slave labour was considerably less than that of free labour. By locking themselves into a slave-based economy the slave owners deprived themselves of further economic gains. [102]

| Cette loi est admirable. — Sans elle, pourvu qu’il y eût équilibre de force entre les oppresseurs et les opprimés, la Spoliation n’aurait pas de terme. — Grâce à elle, cet équilibre tend toujours à se rompre, soit parce que les Spoliateurs se font conscience d’une telle déperdition de richesses, soit, en l’absence de ce sentiment, parce que le mal empire sans cesse, et qu’il est dans la nature de ce qui empire toujours de finir. | This law is admirable. In its absence, provided that there were a stable balance of power between the oppressors and the oppressed, Plunder would have no end. Thanks to this law, the balance always tends to be upset, either because the Plunderers become aware of the loss of so much wealth, or, where this awareness is lacking, because the harm constantly grows worse and it is in the nature of things that constantly deteriorate to come to an end. |

| Il arrive en effet un moment où, dans son accélération progressive, la déperdition des richesses est telle que le Spoliateur est moins riche qu’il n’eût été en restant honnête. | In fact, there comes a time when, in its gradual acceleration, the loss of wealth is so great that Plunderers are less rich than they would have been if they had remained honest. |

Secondly, Bastiat thought that a “Malthusian Law” operated to fatally restrict the expansion of the plundering class. The Malthusian pressures on the plundering class were twofold: their plunder provoked opposition on the part of those who were being plundered who would eventually resist (such as tax revolts, smuggling, or outright revolution); and the “Plunderers” (of wealth) would gradually realize that their plunder and regulation created economic inefficiencies and absolute limits on the amount of wealth they could extract from any given society. Bastiat developed his ideas on a Malthusian limit of the scale of plunder first in a discussion of “theocratic plunder” and then in a section on the State in general: [103]

| La Spoliation par ce procédé et la clairvoyance d’un peuple sont toujours en proportion inverse l’une de l’autre, car il est de la nature des abus d’aller tant qu’ils trouvent du chemin. Non qu’au milieu de la population la plus ignorante, il ne se rencontre des prêtres purs et dévoués, mais comment empêcher la fourbe de revêtir la soutane et l’ambition de ceindre la mitre ? Les spoliateurs obéissent à la loi malthusienne : ils multiplient comme les moyens d’existence ; et les moyens d’existence des fourbes, c’est la crédulité de leurs dupes. On a beau chercher, on trouve toujours qu’il faut que l’Opinion s’éclaire. Il n’y a pas d’autre Panacée. (pp. 17-18) | Plunder using this procedure and the clear-sightedness of a people are always in inverse proportion one to the other, for it is in the nature of abuse to proceed wherever it finds a path. Not that pure and devoted priests are not to be found within the most ignorant population, but how do you prevent a swindler from putting on a cassock and having the ambition to don a miter? Plunderers obey Malthus’s law: they multiply in line with the means of existence, and the means of existence of swindlers is the credulity of their dupes. It is no good searching; you always find that opinion needs to be enlightened. There is no other panacea. |

| L’État aussi est soumis à la loi malthusienne. Il tend à dépasser le niveau de ses moyens d’existence, il grossit en proportion de ces moyens, et ce qui le fait exister c’est la substance des peuples. Malheur donc aux peuples qui ne savent pas limiter la sphère d’action de l’État. Liberté, activité privée, richesse, bien-être, indépendance, dignité, tout y passera. (p. 20) | The State is also subject to Malthus’s Law. It tends to exceed the level of its means of existence, it expands in line with these means and what keeps it in existence is whatever the people have. Woe betide those peoples who cannot limit the sphere of action of the State. Freedom, private activity, wealth, well-being, independence and dignity will all disappear. |

In the earliest forms of the plundering state, such as the warrior and slave state of the Roman Empire, the role played by outright violence and coercion in maintaining the flow of plunder to privileged groups was very important. However, as populations grew and economies advanced alternative methods were needed by the elites to protect the continued flow of plunder. It was at this moment in human history, Bastiat thought (developing Bentham’s idea of “deceptions” and “political fallacies” to prevent political reform), [104] that ruling elites began to use “la ruse” and “les sophismes”, and other forms of ideological deception and confusion, so that they could trick or “dupe” the citizens into complying with the demands of the elite to hand over their property.

As he stated in the “Conclusion” of Economic Sophisms I Bastiat explains the connection between his rebuttal of commonly held economic sophisms and the system of plunder he opposed so vigorously: [105]

| Pour voler le public, il faut le tromper. Le tromper, c’est lui persuader qu’on le vole pour son avantage ; c’est lui faire accepter en échange de ses biens des services fictifs, et souvent pis. — De là le Sophisme. — Sophisme théocratique, Sophisme économique, Sophisme politique, Sophisme financier. — Donc, depuis que la force est tenue en échec, le Sophisme n’est pas seulement un mal, c’est le génie du mal. Il le faut tenir en échec à son tour. — Et, pour cela, rendre le public plus fin que les fins, comme il est devenu plus fort que les forts. | In order to steal from the public it it first necessary to deceive them. To deceive them it is necessary to persuade them that they are being robbed for their own good; it is to make them accept imaginary services and often worse in exchange for their possessions. This gives rise to sophistry. Theocratic sophistry, economic sophistry, political sophistry and financial sophistry. Therefore, ever since force has been held in check, sophistry has been not only a source of harm, it has been the very essence of harm. It must in its turn be held in check. And to do this the public must become cleverer than the clever, just as it has become stronger than the strong. |

| Bon public, c’est sous le patronage de cette pensée que je t’adresse ce premier essai, — bien que la Préface soit étrangement transposée, et la Dédicace quelque peu tardive. | Good members of the public, it is this last thought in mind that I am addressing this first essay to you, although the preface has been strangely transposed and the dedication is somewhat belated. |

The Impact of the February Revolution on Bastiat’s Theory of Class↩

The outbreak of Revolution in February 1848 and the coming to power of organised socialist groups forced Bastiat to modify his theory in two ways. The first was to adopt the very language of “class” used by his socialist opponents as we have seen with his change in usage from the pairing of “les spoliateurs” (the plunderers) and “les spoliés” (the plundered) before the Revolution to that of “la classe spoliatrice” (the plundering class) and “les classes spoliées” (the plundered classes) after the Revolution. The second way he changed his theory was to consider more carefully how state organised plunder would be undertaken by a majority of the people instead of a small minority. Before the socialists became a force to be reckoned with in the Second Republic when they introduced the National Workshops program under Louis Blanc, a small minority of powerful individuals (such as slave owners, high Church officials, the military, or large landowners and manufacturers) used the power of the state to plunder the ordinary taxpayers and consumers to their own advantage. Bastiat termed this “la spoliation partielle” (partial plunder). [106] He believed that what the socialists were planning during 1848 was to introduce a completely new kind of plunder which he called “la spoliation universelle” (universal plunder) or “la spoliation réciproque” (reciprocal plunder). In this system of plunder the majority (that is to say the ordinary taxpayers and consumers who made up the vast bulk of French society) would plunder itself, now that the minority of the old plundering class had been removed from political power. Bastiat thought that this was unsustainable in the long run and in his famous essay on “The State” (June, September 1848) called the socialist-inspired redistributive state “the great fiction by which everyone endeavors to live at the expense of everyone else.” [107]

At this time I don’t think Bastiat fully grasped how the modern welfare state might evolve into a new form of class rule in the name of the people where “les fonctionnaires” (state bureaucrats and other functionaries), supposedly acting in the name of the people, siphoned off resources for their own needs. Bastiat gives hints that this might happen in his discussion of the “parasitical” nature of most government services [108] and his ideas about “la spoliation gouvernementale" (plunder by government) [109] and “le gouvernementalisme” (rule by government bureaucrats) [110] which suggest the idea that government and those who work for it have their own interests which are independent of other groups in society. These are insights which Bastiat’s younger friend and colleague Gustave de Molinari took up two years after Bastiat’s death in his class analysis of how Louis Napoléon came to power and brought the Second Republic to an end. [111]

In two private letters to Madame Hortense Cheuvreux, the wife of a wealthy benefactor who helped Bastiat find time to work on his economic treatise during the last two years of his life, Bastiat makes some interesting observations about the nature of the class antagonisms which were dividing France. In the first letter (January 1850) he offered Mme Cheuvreux an analysis of the conflict between the people and the bourgeoisie, what he called “deux grandes classes” (the two two great classes), based upon what he had observed during the revolution. He concludes that the French bourgeoisie had had an opportunity to bring class rule in France to an end and by not doing so had alienated a large section of the working class (see the passage from this letter quoted above). [112]

In the second letter (23 June, 1850) he is even more pessimistic in believing that France (and perhaps all of Europe) is doomed to never-ending “guerre sociale” (social or class war). He talks about how history is divided into two alternating phases of “struggle” and “truce” to control the state and the plunder which flows from this: [113]

| … tant qu’on regardera ainsi l’État comme une source de faveurs, notre histoire ne présentera que deux phases : les temps de luttes, à qui s’emparera de l’État ; et les temps de trêve qui seront le règne éphémère d’une oppression triomphante, présage d’une lutte nouvelle. | … as long as the state is regarded in this way as a source of favors, our history will be seen as having only two phases, the periods of conflict as to who will take control of the state and the periods of truce, which will be the transitory reign of a triumphant oppression, the harbinger of a fresh conflict. |

Conclusion↩

The Class Interest of Bastiat the Landowner