David M. Hart, “Frédéric Bastiat: The ‘Unseen’ Radical”

A talk given at the Students for Liberty 10th Anniversary Conference

17–20 Feb. 2017

Washington DC

Introduction↩

These are my notes and the illustrations I used in the talk. They are not yet in a polished form. I did not have time to talk about all of the points list below and I jumped around a bit in the actual talk. I plan to write them up into a more formal paper very soon. Use them “as is” for the time being!

For more information about Frédéric Bastiat see the following:

- A “Summary of the Bastiat Project” at the Online Library of Liberty http://oll.libertyfund.org/pages/bastiat-project-summary.

- A list of some resources on Bastiat at my personal website http://davidmhart.com/liberty/index.html#bastiat.

Abstract↩

The French economist and journalist Frédéric Bastiat is quite well known in free market circles because of his sparkling and witty “economic sophisms” which debunk the supposed benefit of tariff protection and subsidies to favoured industries, such as the justly famous “Petition of the Candlemakers”. Among conservatives he is remembered for his essays on limited government and the rule of law, such as “The State” and “The Law.” This is the “seen” aspect of Bastiat’s life and work. What is less well-known, or even not known at all, is the “unseen” radical side to Bastiat. Or rather, there are several radical “sides” to Bastiat that modern readers should take note of:

- his initial radicalisation at a private college with an innovative curriculum

- the social radical, bon-vivant, and non-conformist outsider

- his “rhetoric of liberty” and use of “harsh” language in the economic sophisms - calling state activity what it really was - theft and plunder

- his opposition to military spending, war, and imperialism

- his “utopian” dreams of drastically cutting the size of government (his “ultra-minimalist” theory of the state)

- his support for the Revolution of February 1848 and the democracy and republicanism of the Second Republic

- the innovative theoretical economist who was years ahead of his time

- the theorist of classical liberal class analysis, who had he lived longer might have become the “Karl Marx of the classical liberal movement”

- his understanding of liberty as “the sum of all freedoms”: the integration of political, economic, social (or sociological), and historical approaches to understanding human beings and their societies

- the opponent of “theocratic plunder” by the Catholic Church

- his impact on the modern libertarian movement - Circle Bastiat in NYC in 1950s (Rothbard, Liggio, Raico)

In this talk I want to discuss these radical, unknown, and thus “unseen”, aspects of Bastiat’s thinking and make them visible for a new generation of readers of his works.

Table of Contents↩

-

Introduction

- A Brief Survey of Bastiat’s Life & Work

- What Bastiat accomplished in 7 Years (1844–50)

- Bastiat’s Impact on Others

- Bastiat’s Radicalism

- His initial intellectual radicalisation at the innovative private Collège de Sorèze (1814–1818)

- “In vino libertas” (in wine there is liberty): Bastiat the social radical, bon-vivant, and non-conformist outsider.

- Bastiat’s radical “rhetoric of liberty”: the use of “harsh language” and “the sting of ridicule” in the Economic Sophisms

- Bastiat’s opposition to military spending, war, and imperialism

- The politician with “utopian” dreams of drastically cutting the size of government (his “ultra-minimalist” theory of the state)

- Bastiat’s support for the Revolution of February 1848 and the democracy and republicanism of the Second Republic

- Bastiat the innovative economic theorist

- Bastiat the theorist of classical liberal class analysis and “legal plunder”

- Bastiat’s vision of Liberty as “the sum of all freedoms”, as “a systematic and harmonious whole”

- Bastiat’s opposition to “theocratic plunder” by the Catholic Church

- Bastiat’s impact on the modern libertarian movement - Circle Bastiat in NYC in 1950s (Rothbard, Liggio, Raico)

- Bastiat’s Courage and Dignity in Death

- Some Ironies to Reflect upon

- Irony 1

- Irony 2

Frédéric Bastiat: The “Unseen” Radical

Introduction↩

A Brief Survey of Bastiat’s Life & Work↩

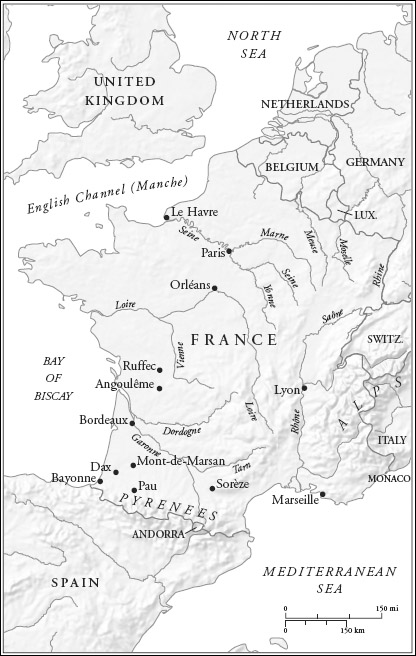

- FB born June 30, 1801 in Bayonne, Dept. of Les Landes, region of Aquitaine in SW France

- gentleman farmer and local magistrate until 1845

- 1842 discovered Cobden’s Anti-Corn Law League and wanted to build French Free Trade movement

- 1844–45 wrote articles & books on tariffs & trade which impressed the Paris “Economists” (the Guillaumin network)

- 1846–48: Libre-Échange magazine, Economic Sophisms

- 1848: involved in Feb. Revolution, street journalism, elected to Const. Assembly, VP Finance Committee

- 1848 to mid–1850: ideological and political battle against socialism, pamphlet war: The Law, The State, Property and Plunder, WSWNS

- 1850 unfinished treatise on economics: Economic Harmonies

died 24 Dec. 1850 from throat cancer

What Bastiat accomplished in 7 Years (1844–50)↩

FB emerged from obscurity in 1844 (aged 43) and over the next 7 years had an extraordinary career and wrote nearly 1 million words before his untimely death from throat cancer. He was able to combine in a consistent and coherent way the following activities:

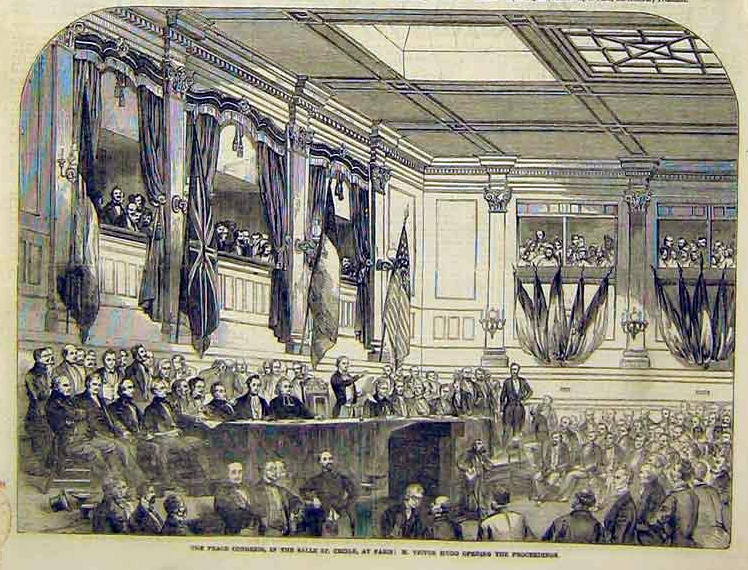

- activism in the French Free Trade Association (1844–1848) and the Friends of Peace Congress (1848–50)

- journalism in which he exposed the economic fallacies used to defend protectionism and govt. interventionism in the economy

- election to political office during a revolution (1848–1850)

- innovative work on economic and political theory (1848–1850)

Bastiat’s Impact on Others↩

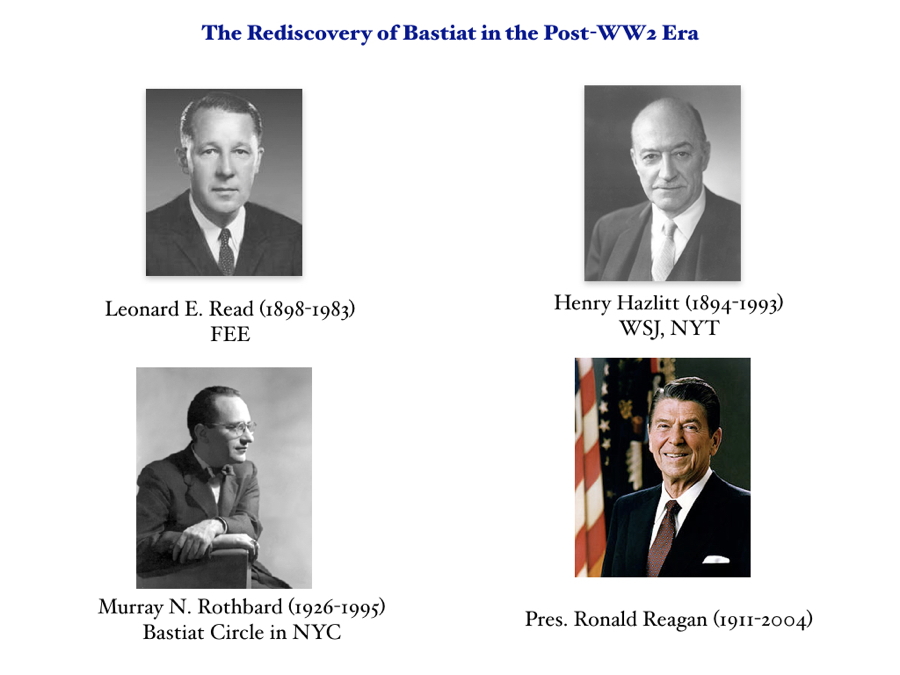

- profound impact on the 19thC French Classical Liberal (CL) movement; his books remained in print throughout this period

- inspired a small school of free market economics in US in late 19thC

- significant influence on rediscovery of free market ideas in US post 1945:

- Leonard E. Read (1898–1983) FEE

- Henry Hazlitt (1894–1993) WSJ, NYT

- Murray N. Rothbard (1926–1995), Bastiat Circle in NYC, Mises Institute

- Pres. Ronald Reagan (1911–2004)

- Ron Paul (1935-)

Bastiat’s Radicalism↩

Radical in both content and form.

The French economist and journalist Frédéric Bastiat is quite well known in free market circles because of his sparkling and witty “economic sophisms” which debunk the supposed benefit of tariff protection and subsidies to favoured industries, such as the justly famous “Petition of the Candlemakers”. Among American conservatives he is remembered for his essays on limited government and the rule of law, such as “The State” and “The Law.” This is the “seen” aspect of Bastiat’s life and work. What is less well-known, or even not known at all, is the “unseen” radical side to Bastiat. Or rather, there are radical radical “sides” to Bastiat that modern readers should take note of:

- his initial radicalisation at a private college with an innovative curriculum

- the social radical, bon-vivant, and non-conformist outsider (part of the group of “Seven Musketeers”)

- his “rhetoric of liberty” and use of “harsh” language in the economic sophisms to popularise free market ideas

- his opposition to military spending, war, and imperialism

- his “utopian” dreams of drastically cutting the size of government (his “ultra-minimalist” theory of the state)

- his support for the Revolution of February 1848 and the democracy and republicanism of the Second Republic

- the innovative theoretical economist who was years ahead of his time

- the theorist of classical liberal class analysis (legal plunder)

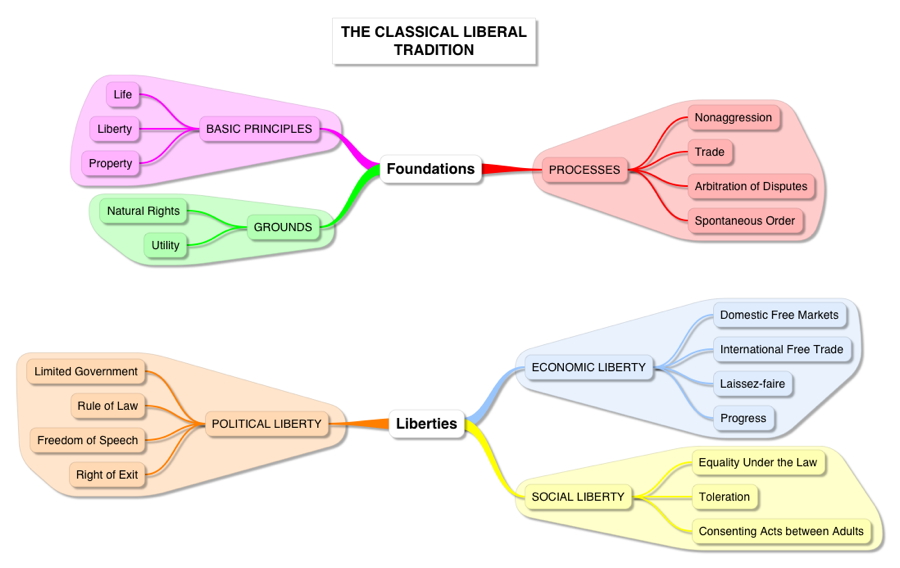

- his understanding of Liberty as “the sum of all freedoms” (political, economic, social)

- the opponent of “theocratic plunder” by the Catholic Church

- his impact on the modern libertarian movement - Circle Bastiat in NYC in 1950s (Rothbard, Liggio, Raico)

His initial intellectual radicalisation at the innovative private Collège de Sorèze (1814–1818)↩

FB was a free thinking individual who was the product of an innovative, secular, liberal, private education at a College located in the Abbey of Sorèze in the Department of Tarn in the region of Occitane. He attended the College between the ages of 14 and 18 (1815–1819) but did not graduate with a diploma. The College was in benedictine Abbey founded in 754 AD; became a college in 1682; Louis XVI turned it into a military college for sons of aristocracy in 1776; in 1793 all military colleges were closed and college was privatised. It remained a private college until it was given back to the Church in 1854.

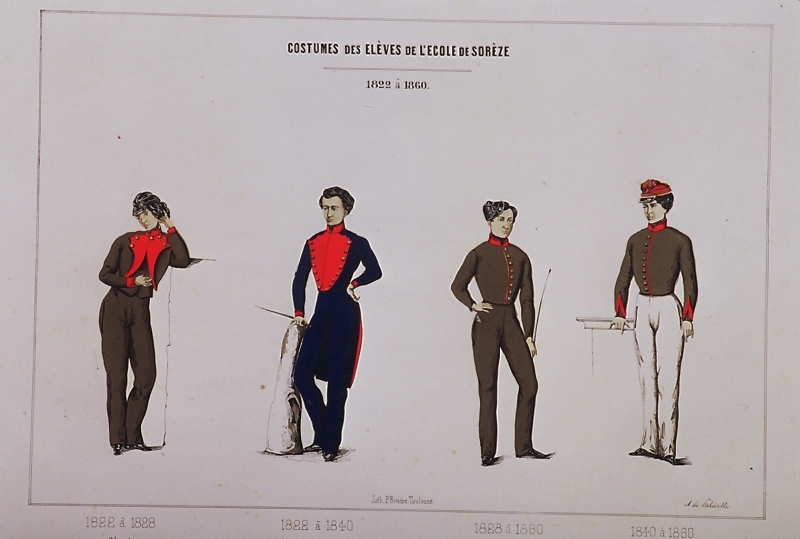

When FB attended it it had 400 students from all over Europe, England, and America. The students all wore the same uniform (see the image on the left from 1822 just after FB had left) so there was distinction between poorer students on scholarships and the sons of the wealthy.

The College had an innovative curriculum in that it did not teach Latin or Greek, but modern languages, literature, music, and mathematics. FB learned good English and Italian; wrote poetry, and learned to play the cello (which he continued to do for the rest of life). The college was polyglot, cosmopolitan, liberal, and secular for 60 years until it was returned to the Church in 1854.

The school taught him independent thinking, a passion for literature (which he often quoted later in his economic writings - Molière, La Fontaine), and a deep love of reading. For rest of his life he disliked state education and the teaching of the Greek and Roman classics (warrior and slave-owning values).

After he left college he worked in his grandfather’s business in Bayonne (his parents had both died when he was young) but did not enjoy it. When his grandfather died in 1825 he inherited his estate in Mugron and began the life of a farmer and winegrower with a comfortable income, earning enough to be in the top 2% of direct tax payers and thus eligible to vote and stand for election (FB called this small group “la classe éléctorale” (the electoral or voting class). He continued to read widely and formed with some neighbours in Mugron a kind of “book club” or discussion group called “The Academy” which met regularly to discuss current events and new books.

Sometime during this period FB discovered the writings of the radical liberal journalists and lawyers Charles Comte and Charles Dunoyer. They had challenged the autocratic power of Napoleon in a series of journals they started in 1814 - Le Censeur and then Le Censeur européen - and then wrote some very important books on classical liberal class analysis and the “industrialist” theory of history, all of which FB read and absorbed. Probably through CC and CD FB came across the writings of JB Say which may have begun his interest in economics. For the next 20 years FB remained in the quiet rural area around Mugron on the Adour river and voraciously read everything about economics he could lay his hands on, in 4 different languages (French, Spanish, Italian, and English). This was his intellectual preparation before he made contact with the Parisian-based free market economists in late 1844.

A bust of Bastiat is on display at the college along with other alumni, many of whom are military officers.

“In vino libertas” (in wine there is liberty): Bastiat the social radical, bon-vivant, and non-conformist outsider.↩

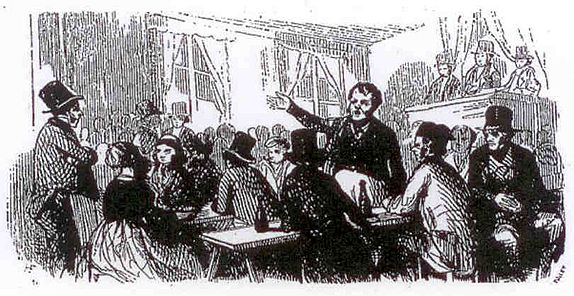

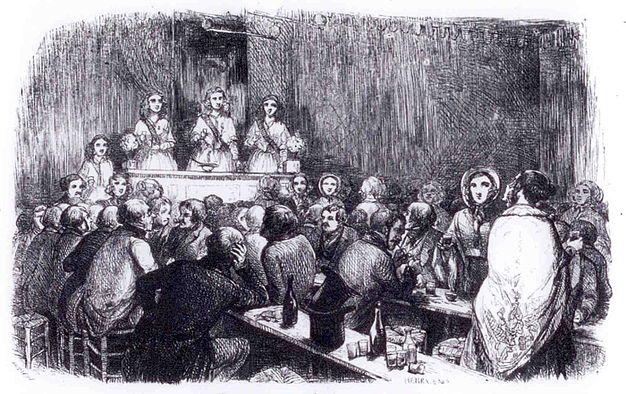

During the 1820s when FB was in his twenties the restored Bourbon kings (Louis XVIII (1814–1824) and Charles X (1824–1830)) cracked down on civil liberties in order to undo many of the gains of the Revolution (those which had been left by Napoleon!). Because political organisations were banned people gathered informally in bars (gogettes) to talk and sing political songs written by poets and song writers (gogettiers) like the best-selling Pierre-Jean de Béranger. The police would often break in and force the goguette to close for violating the ban on political discussions.

When FB first became involved in liberal politics it was with a group young liberals in Bayonne who protested the censorship laws. He knew many songs by Béranger off by heart and would latter quote them in his writing. No doubt he learned them singing and talking politics in bars in the town of Bayonne. After he moved to Paris to run the French Free Trade Assocaition he persuaded Béranger to join the Association and sat with B in the Chamber as he too got elected to the Constituent Assembly in April 1848.

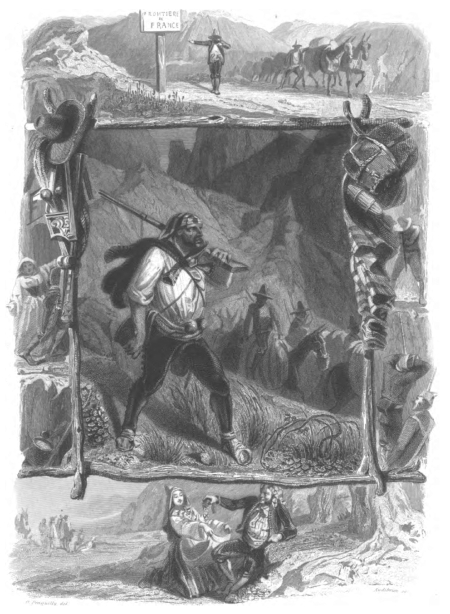

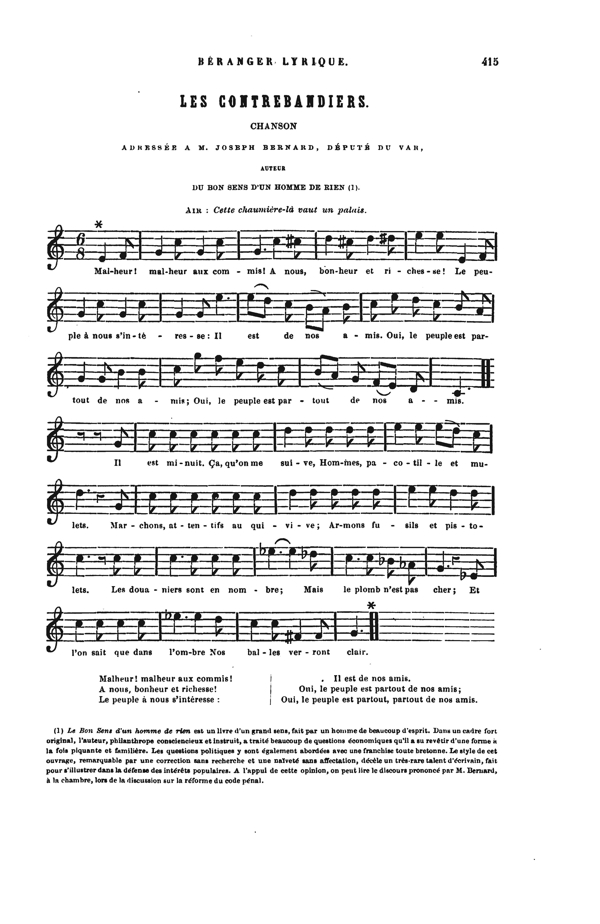

As a supporter of free trade he no doubt knew this one about “The Smuggler”

Curse them! Curse them, the Revenue Men!

For we bring happiness and wealth!

The people always toast our health.

They are indeed our friends.

Yes, everywhere the people are our friends.

Yes, everywhere, everywhere, the people are our friends.Men busy themselves with trade

But taxes bar the way.

Let us through! Exchanges will be made,

There will be balance, come what may.

Providence protects us everywhere

And asks that in return,

Abundance we will share

So wealth there is to earn.

Sheet music and words of The Smugglers in Béranger lyrique. Oeuvres complètes de P.J. de Béranger. Nouvelle édition revue par l’auteur (Bruxelles: Librairie encyclopédique de Perichon, 1850), p. 415–16

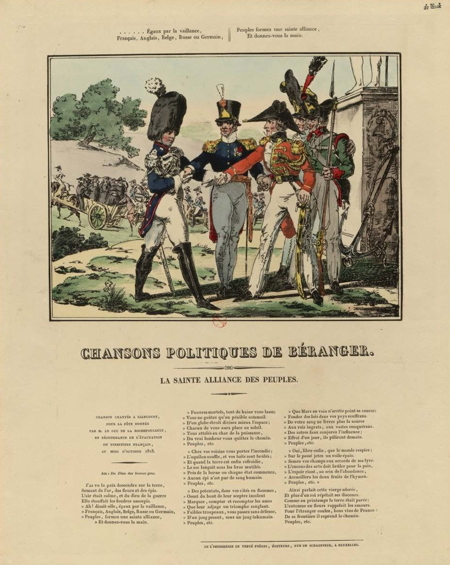

and this one about people uniting in their own “holy alliance” (my trans.):

While your cities burn, your dictators have the impudence

to count and recount with the tip of their mocking sceptres

the bodies which have fallen in battle

which history now calls a bloody triumph.

You poor beasts of burden!

You go helplessly from a heavy yoke

to an even more inhuman one.People of the World! Form a Holy Alliance,

take each other by the hand, and Unite!So that the (murderous) path of Mars (the god of war) is stopped for good;

Enact laws in your suffering countries.

No longer hand over the source of your blood

to ungrateful kings and mighty conquerors.

Ignore the influence of these false prophets;

The things you fear today will fade away tomorrow.People of the World! Form a Holy Alliance,

take each other by the hand, and Unite!

Source: Béranger’s Songs of the Empire, the Peace, and the Restoration. Translated into English verse by Robert B. Clough (London: Addey and Co., 1856), pp. 59–62. My new trans.

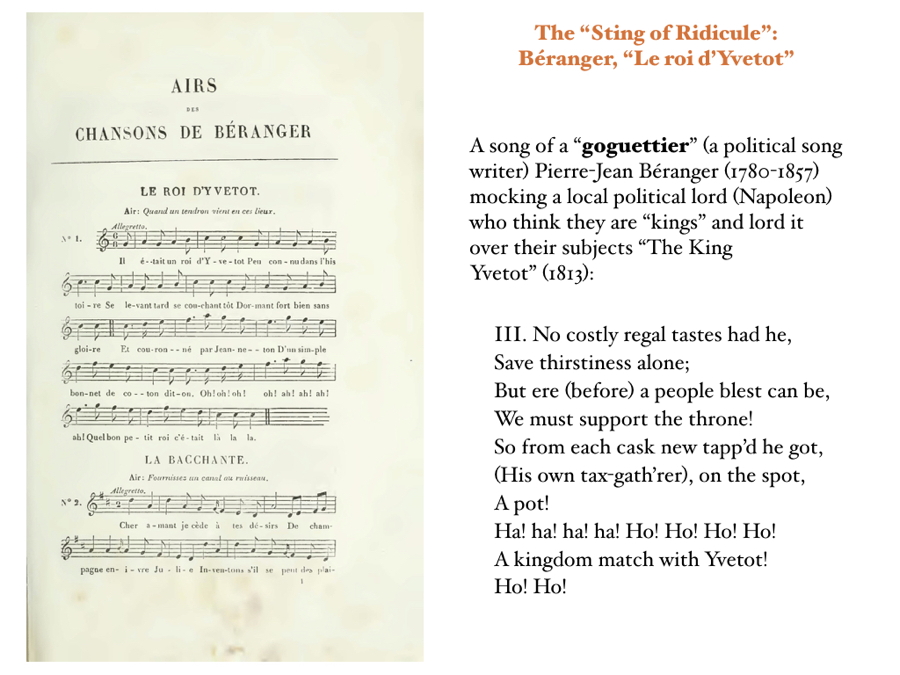

and this very funny one mocking upstart political leaders who want to become like Napoleon

A song of a “goguettier” (a political song writer) Pierre-Jean Béranger (1780–1857) mocking a local political lord (Napoleon) who think they are “kings” and lord it over their subjects “The King Yvetot” (1813):

III. No costly regal tastes had he, Save thirstiness alone; But ere (before) a people blest can be, We must support the throne! So from each cask new tapp’d he got, (His own tax-gath’rer), on the spot,

A pot!

Ha! ha! ha! ha! Ho! Ho! Ho! Ho!

A kingdom match with Yvetot!

Ho! Ho!IV. So well he pleased the damsels all,

The folks could understand

A hundred reasons him to call

The Father of his Land.

His troops levied in his park

But twice a year - to hit a mark,

And lark!

Ha! ha! ha! ha! Ho! Ho! Ho! Ho!

A kingdom match with Yvetot!

Ho! Ho!”

The songs of Béranger, Bastiat, and liberal politics came together in August 1830. In a letter to his friend Felix Coudroy (Bayonne 5 August 1830) Bastiat relates his activities in the 1830 Revolution (27–29 July) when the garrison in Bayonne was split over whether or not to side with the revolution or the sitting monarch Charles X. Bastiat visited the garrison in order to speak to some of the officers in order to swing them over the revolutionary cause. In a midnight addition to his letter Bastiat relates how some good wine and the songs of Béranger helped him persuade the officers that night:

The 5th at midnight

I was expecting blood but it was only wine that was spilt. The citadel has displayed the tricolor flag. The military containment of the Midi and Toulouse has decided that of Bayonne; the regiments down there have displayed the flag. … Thus, it is all over. I plan to leave immediately. I will embrace you tomorrow.

This evening we fraternized with the garrison officers. Punch, wine, liqueurs and above all, Béranger contributed largely to the festivities. Perfect cordiality reigned in this truly patriotic gathering. The officers were warmer than we were, in the same way as horses which have escaped are more joyful than those that are free. [CW1, p. 30] http://oll.libertyfund.org/titles/2393#Bastiat_1573-01_208

When he was living in Paris in the late 1840s FB attended two liberal salons run by the wives of wealthy supporters of the free trade movement, Hortense Cheuvreux and Anna Say; and a third salon run by the radical journalist Hippolyte Castille. He made a name for himself in the former for his ability to amuse the other guests by reciting scenes from Molière’s plays (often parodying them) or stories by La Fontaine, playing his cello, and singing song’s by Béranger. This would scandalise some of the guests who were prudish (many of the song were quite bawdy and suggestive sexually) and thought his mocking tone about politicians and the government were not in good taste.

He was also socially radical - the bon-vivant and non-conformist outsider - because of his speech and clothing. Gustave de Molinari noted in his obit how strangely FB dressed and talked. He had a strong Gascon regional accent, and dressed in the attire of a provincial farmer; GdM’s reminiscence about his dress (refusal to wear drab black coats like everybody else, umbrella, hat), his “Rabelaisian” wit (i.e. bawdy, sexual innuendo).

His love of music (he played the cello), attended opera and concerts in Paris; constantly quoting/reciting Molière/La Fontaine.

What FB might have dressed like:

Molinari’s comments about FB’s attire and speech in his obit, p. 186

We had a chance to see him when he was making his first rounds of the offices of the journals/newspaper which had shown themselves to be sympathetic to the free trade cause. He still hadn’t taken the time to visit a Parisian tailor or a hatter, which by the way he truly had thought about doing! With his long hair and his small hat, his large riding jacket, and his family-sized (??) umbrella, one would have happily taken him for a good farmer in the middle of visiting/sampling the marvels of the capital city. But the demeanour of this farmer who was still rough around the edges was impish (malicieuse) and witty/intellectual (spirituelle). His large dark eyes were lively and bright, his brow was of middling/medium size and somewhat square in shape as if full of stuff??, and bore the stamp of his thinking/idea. At first glance one got the impression that this farmer here came from the country of Montaigne, and when one heard him speak one immediately recognised in him a disciple of Benjamin Franklin. p. 186

Molinari’s later observations in his review of Hortense Cheuvreux’s collection of letters from FB (1877):

However we had read the book (Cobden and the League) and the Courrier français had published an enthusiastic review of it. Some time after this our office boy announced that “a gentleman who had the appearance of coming from the provinces” had come to visit. We said” Bring in ‘the gentleman who had the appearance of coming from the provinces’.” Appearing before us was a lean gentleman with a stocky build, a finely shaped head, an honest looking face, a nose which was little on the large size, a swarthy complexion, brown eyes which were lively and impish looking, and thick black hair upon which sat a tall hat with practically no brim. Added to all this was large olive green riding jacket and a large umbrella. Here you will have a a good idea of what the “gentleman who had the appearance of coming from the provinces” looks like, the man who was no other than the author of Cobden and the League. And we soon got to know him.

Hortense Cheuvreux’s observations in the intro to her collection of his letters to her (Lettres d’un habitant des Landes, Frédéric Bastiat, pp. 3–4.):

There I saw Bastiat fresh from the great Les Landes present himself at M. Say’s home. His attire was so conspicuously different from those surrounding [xxx] him that the eye, however distracted, could not help but stare at him for a moment. The cut of his garments, due to the scissors of a tailor from Mugron, was far away from ordinary designs. Bright colors, poorly assorted, were placed next to one another, without any attempt at harmony. Floss-silk gloves covering his hands, playing with long white cuffs; a sharp collar covering half his face; a little hat, long hair; all that would have looked ludicrous had not the mischievous appearance of the newcomer, his luminous glance, and the charm of his conversation made one quickly forget the rest.

Sitting in front of this farmer/countryman, I discovered that Bastiat was not only one of the high priests of the temple, but also a passionate innovator/teacher/initiator. What fire, what verve, what conviction, what originality, what winning and witty common sense! Through this cascade of clear ideas, of these arguments/displays, new and to the point, the heart was shown, the true soul of man revealed itself. I said to myself, “Here is someone whom one had to get to know better or explain why not. In spite of themselves, perhaps (even) women will be get interested in “The Influence of French and English Tariffs (FB breakthrough essay in JDE).”

After dinner music was played. This inhabitant of Les Landes had another surprise in store for us; he possessed a feeling/love of the arts and poetry at the highest level.

Bastiat’s radical “rhetoric of liberty”: the use of “harsh language” and “the sting of ridicule” in the Economic Sophisms↩

Discussed in more detail in my Intro to CW3.

Use of humor, satire, plays/dialogue, fake petitions to govt., parodies of French classical literature, was innovative and original (Harriett Martineau??)

A list of the rhetorical devices used by Bastiat in the Sophisms shows the breadth and complexity of what one might call his “rhetoric of liberty,” which he formulated to expose the follies of the policies of the ruling elite and their system of “legal plunder,” and to undermine their authority and legitimacy with “the sting of ridicule”:

- a standard prose format which one would normally encounter in a newspaper

the single authorial voice in the form of a personal conversation with the reader - a serious constructed dialogue between stock figures who represented different viewpoints (in this Bastiat was influenced by Jane Marcet and Harriet Martineau; Gustave de Molinari continued Bastiat’s format in some of his writings in the late 1840s and 1850s)

- satirical “official” letters or petitions to government officials or ministers, and other fabricated documents written by Bastiat (in these Bastiat would usually use a reductio ad absurdum argument to mock his opponents’ arguments), e.g. “The Petition of the Candlemakers”

- the use of Robinson Crusoe “thought experiments” to make serious economic points or arguments in a more easily understandable format

“economic tales” modelled on classic French authors such as La Fontaine’s fables, and Andrieux’s short stories - parodies of well-known scenes from French literature, such as Molière’s plays

- quoting scenes of plays were the playwright mocks the pretensions of aspiring bourgeois who want to act like the nobles who disdain commerce (e.g., Molière, Beaumarchais

- quoting poems with political content, e.g. Horace’s Ode on the transience of tyrants

- quoting satirical songs about the foolish or criminal behaviour of kings or emperors (such as Napoleon) (Bastiat seems to be familiar with the world of the “goguettiers” (political song writers, especially Béranger) and their interesting sociological world of drinking and singing clubs

- the use of jokes and puns (such as the names he gave to characters in his dialogs (Mr. Blockhead), or place names (Stulta and Puera), and puns on words such as Highville, and gaucherie)

Then when he thought this was ineffective he began to use “harsh” language to denounce the activities of the state in the economic sophisms (to debunk protectionist and socialist measures). Doubts about which was best strategy, so oscillated between the two.

Examples of his use of “harsh” and direct language (offensive to some) to call state activity what it really was (“appeler un chat un chat” or “to call a spade a spade”- theft and plunder (his radical rhetoric and style).

Bastiat uses a variety of words in his attempt to speak plainly and brutally. Here is a list with our preferred translation for each:

- “dépouiller"(to dispossess),

- “spolier" (to plunder),

- “voler“ (to steal), and variants such as ”le vol de grand chemin" (highway robbery)

- “piller" (to loot or pillage),

- “filouter" (filching).

Struggled about decision to use “harsh” even brutal language to criticise tariffs and subsidies:

People find my small volume of Sophisms too theoretical, scientific and metaphysical. So be it. Let us try a mundane, banal and, if necessary, brutal style. Since I am convinced that the general public are easily taken in as far as protection is concerned, I wanted to prove it to them. They prefer to be shouted at. So let us shout: “The Emperor has no clothes!” An explosion of plain speaking often has more effect than the politest circumlocutions. Frankly, my good people, you are being robbed. That is plain speaking but at least it is clear. Anyway let monopolists rest assured. Theft by subsidy or tariff does not violate the law, although it transgresses equity/justice as much as highway robbery does; this type of theft, on the contrary is carried out by law. This makes it worse but does not lead to the magistrate’s court.

ES2 9 “Le vol à la prime” (Theft by Subsidy) [Journal des Économistes, January 1846, T. XIII, pp. 115–120]

The theory of plunder which Bastiat was working on in the last couple of years of his life, most notably the first two chapters of ES2 1 “The Physiology of Plunder” and ES2 2 “Two Moral Philosophies”, is a good example of the application of his more “brutal style” to an analysis of how the state goes about extracting the revenue it needs to carry out its activities.

Bastiat described taxation as nothing less than “plunder” (la spoliation) where the more powerful, the plunderers (“les spoliateurs”), use force to seize the property of others (the plundered) in order to provide benefits for themselves or favoured vested interest groups like the aristocracy or the church resulting in what he termed “aristocratic” or “theocratic plunder”. He uses a number of closely linked expressions to describe this process of plunder: the plunderers (les spoliateurs) use a combination of outright coercion (la force), fraud (la ruse), and deception (la duperie) to acquire resources from ordinary workers and consumers. They also resort to the use of misleading and deceptive arguments (sophismes) to deceive ordinary people, the dupes (les dupes), and to convince them that these actions are taken in their own interests and not those of the ruling elites. We have retained this language in our translation and have indicated in the footnotes when Bastiat is using this form of “plain speaking”.

Use of satire and parody to mock politicians and crony capitalists; little plays, dialogues; fake petitions to govt,; parodies of Molière

Sometimes Bastiat goes beyond quoting a famous scene from a well-known classic work and adapts it for his own purposes by rewriting it as a parody. A good example of this is Molière’s parody of the granting of a degree of doctor of medicine in the last play he wrote Le malade imaginaire (The Imaginary Invalid, or the Hypocondriac) (1673) which Bastiat quotes in “Theft by Subsidy” (JDE January 1846). Molière is suggesting that doctors in the seventeenth century were quacks who did more harm to their patients than good, as this translation of his dog Latin clearly suggests:

I give and grant you

Power and authority to Practice medicine,

Purge,

Bleed,

Stab,

Hack,

Slash,

and Kill

With impunity

Throughout the whole world.Ego, cum isto boneto Venerabili et doctor,

Don tibi et concedo Virtutem et puissanciam

Medicandi,

Purgandi,

Seignandi,

Perçandi,

Taillandi,

Coupandi,

Et occidendi

Bastiat’s takes Molière’s Latin and writes his own pseudo-Latin, this time with the purpose of mocking French tax collectors. In his parody Bastiat is suggesting that government officials, tax collectors, and customs officials were thieves who did more harm to the economy than good, so Bastiat writes a mock “swearing in” oath which he thinks they should use to induct new officials into government service:

I give to you and I grant

virtue and power

to steal

to plunder

to filch

to swindle

to defraud

At will, along this whole roadDono tibi et concedo

Virtutem et puissantiam

Volandi

Pillandi

Derobandi

Filoutandi

Et escroquandi

Impune per totam istam Viam

Bastiat’s opposition to military spending, war, and imperialism↩

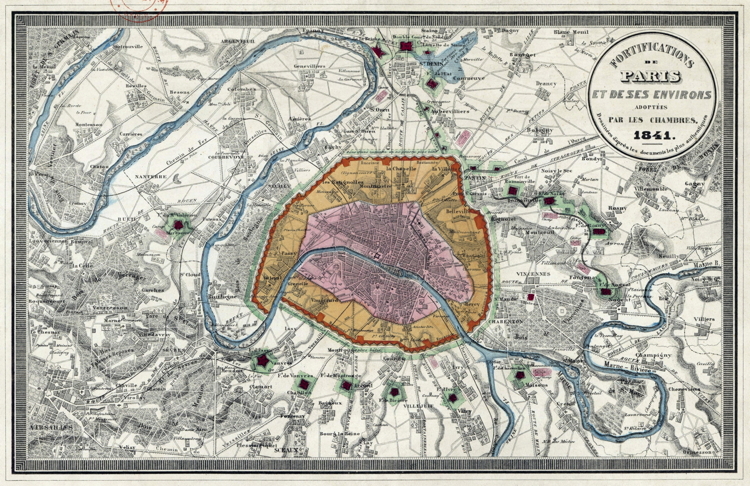

If you look at this map of Paris in 1844 you can see two walls and a ring of forts surrounding the city. This is a wonderful visual representation of how the French government was encircling, regulating, and taxing the people of Paris. The wall surrounding the inner pink zone was the octroi toll (city taxes) gates constructed in the 1780s to make it easier for the privately operated tax collection companies (Fermiers Généraux) to prevent people getting untaxed items into the city. All people entering the city had to pass through gates in the wall, be inspected for taxable goods, and pay any assessed taxes. The Fermiers Généraux were so hated by Parisians that in the first days of the Revolution of 1789 many were burned and the men who ran the tax collection companies were lynched and killed. The walls and gates were largely pulled down in 1859 during the rebuilding of Paris under Napoléon III.

The second red wall which encloses the orange and pink areas was known as “Thiers’ Wall” and was constructed between 1841–44 under the direction of Adolphe Thiers who had been Prime Minister and Minister of Foreign Affairs at various times under the July Monarchy. He urged the construction of this massive and expensive public works (140 million fr. and xxx kms) and its accompanying ring of 16 massive forts around the city because of a panic that the British might be planning to form another Coalition against France and invade and occupy the city. So thousands of hectares of private property was compulsorily acquired by the French state to build a fortified wall, massive entry gates, and an inner service road around the city. It too was eventually demolished in the 1920s but the government land it had occupied was used to build the Périphérique freeway around the city in the 1950s and 60s.??

So this is what FB would have faced when he came to Paris in 1845 to receive the accolades of the Parisian economists after having written his break though articles on tariff reform. He might have arrived by one of the newly build trains from the south west of France, passed between two of the massive star-shaped forts before passing through a tunnel under the fortified wall with soldiers posted on the parapets, disembarked at one of the new huge Parisian railway stations, and then been inspected by city tax collectors before passing through the customs wall into the heart of the city. Out of the windows he would have been constantly reminded of the power, presence, and cost of the state in a most physical and direct way. Given his anti-military sentiments this must have been a hard thing to do without spitting in anger.

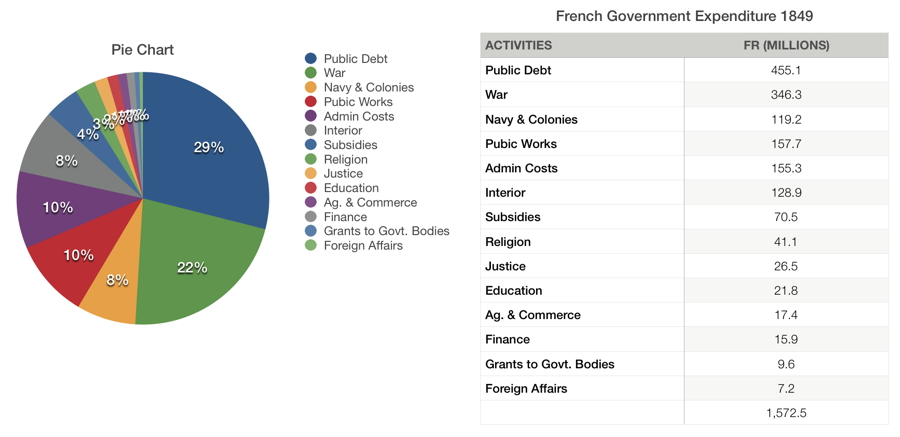

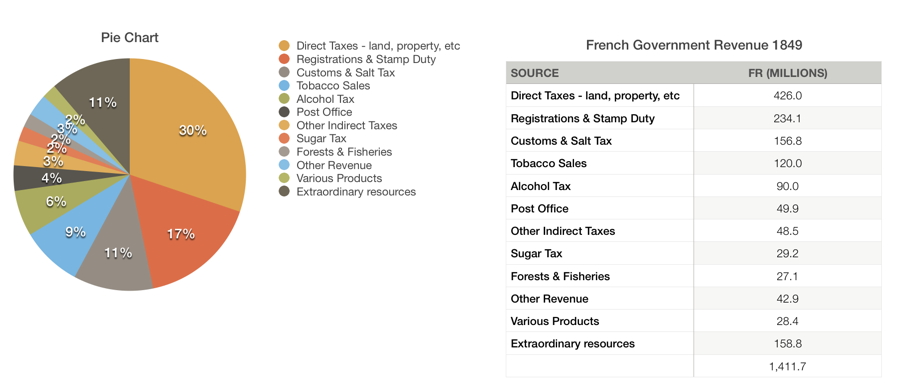

I say “anti-military” because Bastiat was not only opposed to the wars fought by the army both within Europe (most recently by Napoleon) and abroad in the conquest and colonisation of Algeria (1830); but also to the very institution of the army itself within France. Since Bastiat, as an advocate of limited government (or what I call “ultra-minimalist” government, not just “limited government”), wanted to drastically reduce the size and cost of government (expenditure of Fr 1.6 billion in 1849), and since expenditure of the army, navy, and colonies constituted the largest single component of government expenditure (30% not including payment on the debt for past wars - another 29%), spending on all things military had to be drastically cut first as a precondition for cutting the overall size of the government.

Source: “Budget de 1849” in Annuaire de l’Économie politique et de la statistique pour 1850, (Paris: Guillaumin, 1850), pp. 18–23.

We can get an idea of what FB had in mind in the following writings:

- “To the Electors of the District of Saint-Sever” (1846) http://oll.libertyfund.org/titles/2393#Bastiat_1573-01_1829

- ES1 11 “The Utopian”

- Speech at Friends of Peace Congress (Aug. 1849)

- Speech in Chamber on the Tax on Alcohol (Dec. 1849)

- Chapter II “Dismissing Members of the Armed Forces” in WSWNS (July 1850)

In “To the Electors of the District of Saint-Sever” (1846) FB stated he wanted to end the French colonization of Algeria, calling the colonial system “the most disastrous illusion ever to have led nations astray”. He states:

I must make myself clear on one vast subject, more especially as my views probably differ from those of many of you: I am referring to Algeria. I have no hesitation in saying that, unless it be in order to secure independent frontiers, you will never find me, in this case or in any other, on the conqueror’s side.

To me it is a proven fact, and I venture to say a scientifically proven fact, that the colonial system is the most disastrous illusion ever to have led nations astray. I make no exception for the English, in spite of the specious nature of the well-known argument post hoc, ergo propter hoc.

Do you know how much Algeria is costing you? From one-third to two-fifths of your four direct taxes, including the extra cents. Whoever among you pays three hundred francs in taxes sends one hundred francs annually to evaporate into the clouds over the Atlas mountains or to sink into the sands of the Sahara.

We are told that the money is an advance and that, a few centuries from now, we shall recover it a hundredfold. But who says so? The very quartermaster general’s department that swindles us out of our money. Listen here, gentlemen, when it comes to cash, there is but one useful piece of advice: let each man watch his purse … and those to whom he entrusts the purse strings.

In “The Utopian” he wanted to cut the army in half immediately and then eventually abolish the standing army completely and replace it with locally-based militias.

In Speech at Friends of Peace Congress (Aug. 1849) on “Disarmament and Taxes” Bastiat called for simultaneous disarmament of all nations and a corresponding reduction of taxation in his speech at the Second General Peace Congress held in Paris on the 22nd, 23rd and 24th of August, 1849, the President of which was the author Victor Hugo. Émile de Girardin summarized the resolutions of the 1849 Paris Peace Congress as follows: “reduction of armies to 1/200th of the size of the population of each state, the abolition of compulsory military service, the freedom of (choosing one’s) vocation, the reduction of taxes, and balanced budgets.” Since France’s population in 1849 was about 36 million this would mean a maximum size of the French armed forces of 180,000. It was then made up of 389,967 men and 95,687 horses for the Armée de terre, and 69,490 men and 2,051 horses for the Navy and the armed forces in the colonies, for a combined total of 459,457 men and 97,738 horses. Thus, Bastiat and the other attendees at the Peace Congress were calling for a cut of 279,457 or 61% in the size of the French armed forces.

That the maintenance of large military and naval forces requires heavy taxes, is a self-evident fact. But I make this additional remark: these heavy taxes, notwithstanding the best intentions on the part of the legislator, are necessarily most unfairly distributed; whence it follows that great armaments present two causes of revolution—misery in the first place, and secondly, the deep feeling that this misery is the result of injustice…

If the government of France would be contented with asking of us five, six, or even ten per cent of our income, we should consider the tax a direct and proportional one. In such a case, the tax might be levied according to the declaration of the tax-payers, care being taken that these declarations were correct, although, even if some of them were false, no very serious consequences would ensue. But suppose that the treasury had need of 1,500 or 1,800 millions of money. Does it come directly to us and ask us for a quarter, a third, or a half of our incomes? No: that would be impracticable; and consequently, to arrive at the desired end, it has recourse to a trick, and gets our money from us without our perceiving it, by subjecting us to an indirect tax laid on food….

There is, then, only one means of diverting from this country the calamities which menace it, and that is, to equalize taxation; to equalize it, we must reduce it; to reduce it, we must diminish our military force. For this reason, amongst others, I support with all my heart the resolution in favour of a simultaneous disarmament.

In Speech in Chamber on the Tax on Alcohol (12 Dec. 1849) CW3 16 FB states his ideal of 2–300 million fr budget IN TOTAL enough to govern France. Ideal was low flat tax on income of all citizens:

I will suppose for the sake of argument that France has been governed for a long time according to my proposals, which would consist in the government’s keeping each citizen within the limits of his rights and of justice and abandoning everything else to the responsibility of each person. This is my starting point. It is easy to see that in this case France could be governed with two hundred or three hundred million. It is clear that if France were governed with two hundred million, it would be easy to establish a single, proportional tax. (Murmurs.) http://oll.libertyfund.org/titles/2450#Bastiat_1573-02_2120

<However, if you ask citizens to pay, not two hundred million but five hundred, six hundred, or eight hundred million, then as you increase taxes, direct taxes will escape your control and it is clear that you will reach a stage when a citizen would rather take up his gun than pay the state half his wealth, for example.

In Chapter II in WSWNS “Dismissing Members of the Armed Forces” - seen and the unseen applied to closing military garrisons in or near towns (US equivalent is the closing of military bases). Discusses what would happen if politician proposed to dismiss 100,000 men from army immediately. To maintain its armed forces at the level of about 400,000 with a five year period of enlistment the French state had to recruit or conscript about 80,000 men each year. Bastiat roughly estimates that 100,000 soldiers cost the French state fr. 100 million. An immediate cut of 100,000 would be 25.6% of the total size of the French Army. An equivalent cut in the size of the US Armed Forces would be about 373,000 men and women [in 2012 there were 1,456,862 active personnel and a FY2011 budget of $549.4 billion.]

One hundred thousand men who cost the taxpayer one hundred million, live and provide a living for their suppliers to the extent that one hundred million can be spread: that is what is seen.

But one hundred million, extracted from the pockets of taxpayers, interfere with the economic lives of these taxpayers and their suppliers to the tune of that one hundred million: that is what is not seen. Do the calculation, cost it and tell me where the profit lies for the mass of the people?

Opposition to conscription. Young men conscripted at age 20 for 7 years unless they could pay for someone to substitute for them. Since average life expectancy was about 46–47 years losing 7 years of your life to the army in your twenties was a serious economic and personal blow.

There is some evidence he was sent on a secret mission to London in October 1849 after the Peace Congress to negotiate a disarmament treaty with Britain with Cobden.

The politician with “utopian” dreams of drastically cutting the size of government (his “ultra-minimalist” theory of the state)↩

There is Bastiat the radical and “utopian” politician willing to imagine very radical and immediate reforms. Less radical than his friend and colleague GdM but FB was very radical when compared to the other economists.

FB was an advocate of “ultra-minimal” government; smaller govt. than the classic formula drawn up by Adam Smith: police, defence, public goods (roads, possibly some education); FB 5% tariff on both imports and exports until they could be replaced by single flat income tax at possibly a rate of 5–6%?? (all other taxes would be abolished), standing national army disbanded and replaced by local militias; some temporary govt. funding of poor during emergencies (e.g. crop failures); not much else.

- the plans he lists in “The Utopian”

- Sancho Panza as utopian liberal ruler

In the sophism “The Utopian” which appeared at the beginning of 1847 (ES2 11) Bastiat dreams that he is made Prime Minister with the full authority to implement his agenda of economic deregulation, free trade, and tax cuts. He gets carried away with euphoria and announces that he will cut the tax on carrying letters to 10c., cut the salt tax from 30c. to 10c., repeal tariffs on imported cloth, impose an across the board tariff of 5% on all imported goods (down from an average of 11–12% - it was about 23% in the US at this time), and introduce a new tariff of 5% on all exported goods. With revenue cuts on this scale the Utopian politician had to find significant spending cuts to balance it. His very radical solution is to abolish conscription and disband the national standing army of 400,000 men (thus saving about Fr 400 million out of a total budget of Fr 1.6 billion), and replace it with local militias (probably based on the American model). His euphoria at the prospect of such massive cuts spurs him to greater heights, and he now wants to abolish city tolls (a kind of internal tariff to fund city services), reform indirect taxes which fell most heavily on the poor, introduce freedom of religion (and thus end state subsidies) and freedom of education (thus ending the state school and university system). He proclaims that he will then have achieved his ideal size of government whose only function would be “repressing fraud and distributing prompt and fair justice to all.” However he pulls back as he comes to realise that all his reforms will come to nothing unless he has the bulk of the people on his side, and to do this he and the free trade movement have to convince them of the soundness of their ideas, not impose reforms on them from above. He then promptly resigns as Prime Minister (which is what an anarchist would do).

This was not the only time Bastiat imagined himself as a classical liberal dictator who could impose liberal reforms from above. He returned to this idea in an unpublished pamphlet he wrote sometime in 1848, “Barataria”, where Sancho Panza (the companion of Don Quixote) is made dictator of the island of Barataria as a joke by some noblemen. Panza however decides to introduce liberal reforms and not treat the inhabitants as his slaves. This essay will appear in Liberty Fund’s Collected Works of Bastiat, vol. 4.

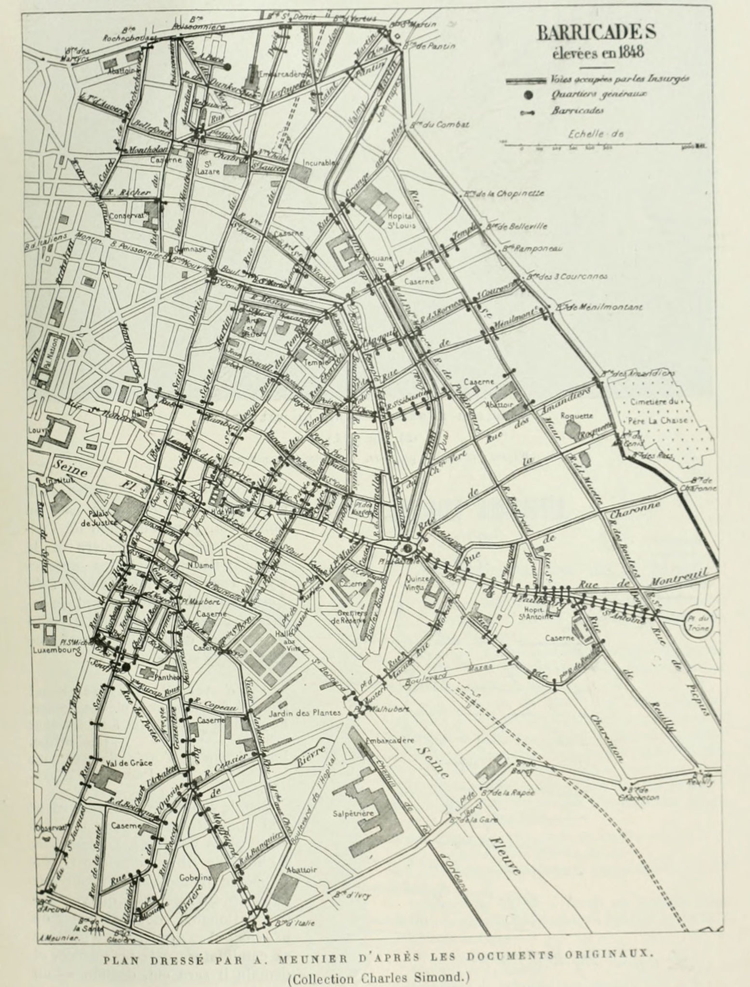

Bastiat’s support for the Revolution of February 1848 and the democracy and republicanism of the Second Republic↩

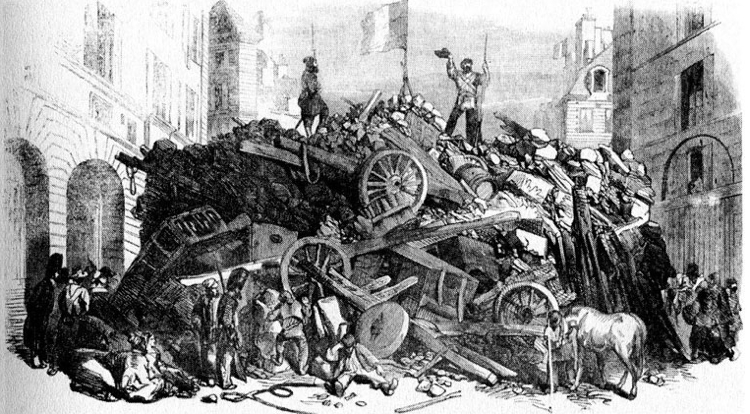

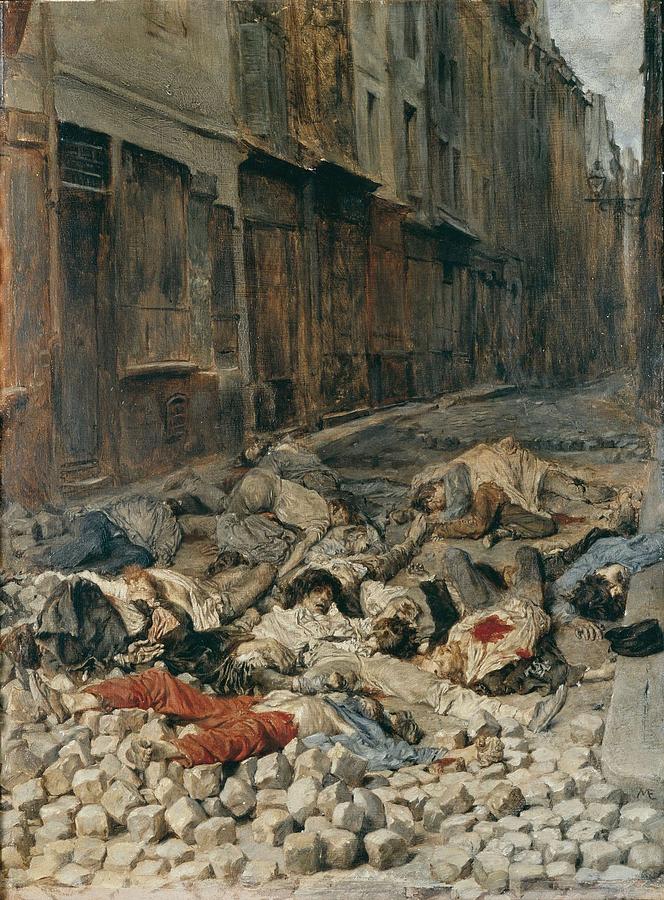

There is the radical republican Bastiat who took to the streets of Paris in February and June 1848 to support the revolution against the July Monarchy of Louis Philippe.

1848 not 1st time he was involved in Revolution; helped persuade officers in Bayonne citadelle to side with Louis Philipe in overthrow of Bourbon Charles X in July 1830 (he was 29); drank red wine and sang political songs by Béranger

His longstanding opposition to “la class électorale” (the electoral class of 240,000 voters who ruled France before 1848). He was a member of that class and stood for election in his Department several times unsuccessfully.

Expressed hatred of the landed and merchant “oligarchy” which ruled England in “Introduction” to first book Cobden and the League (1845).

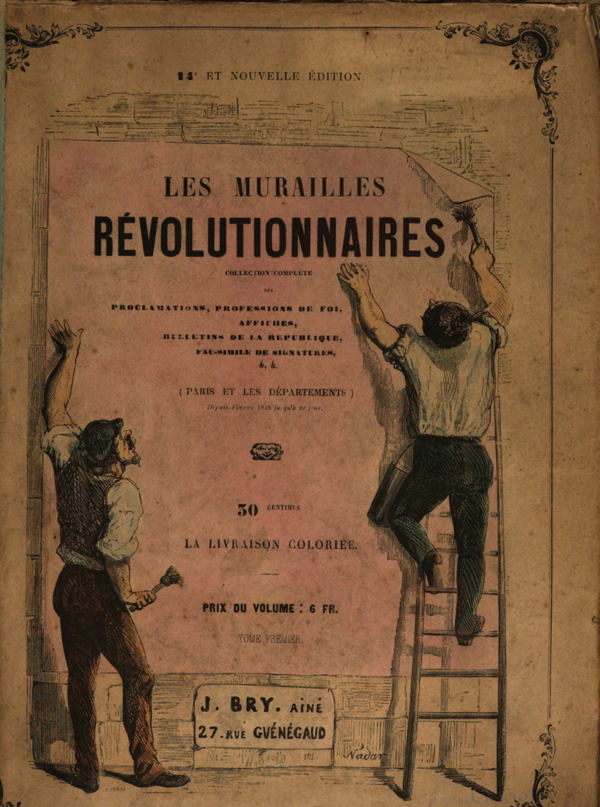

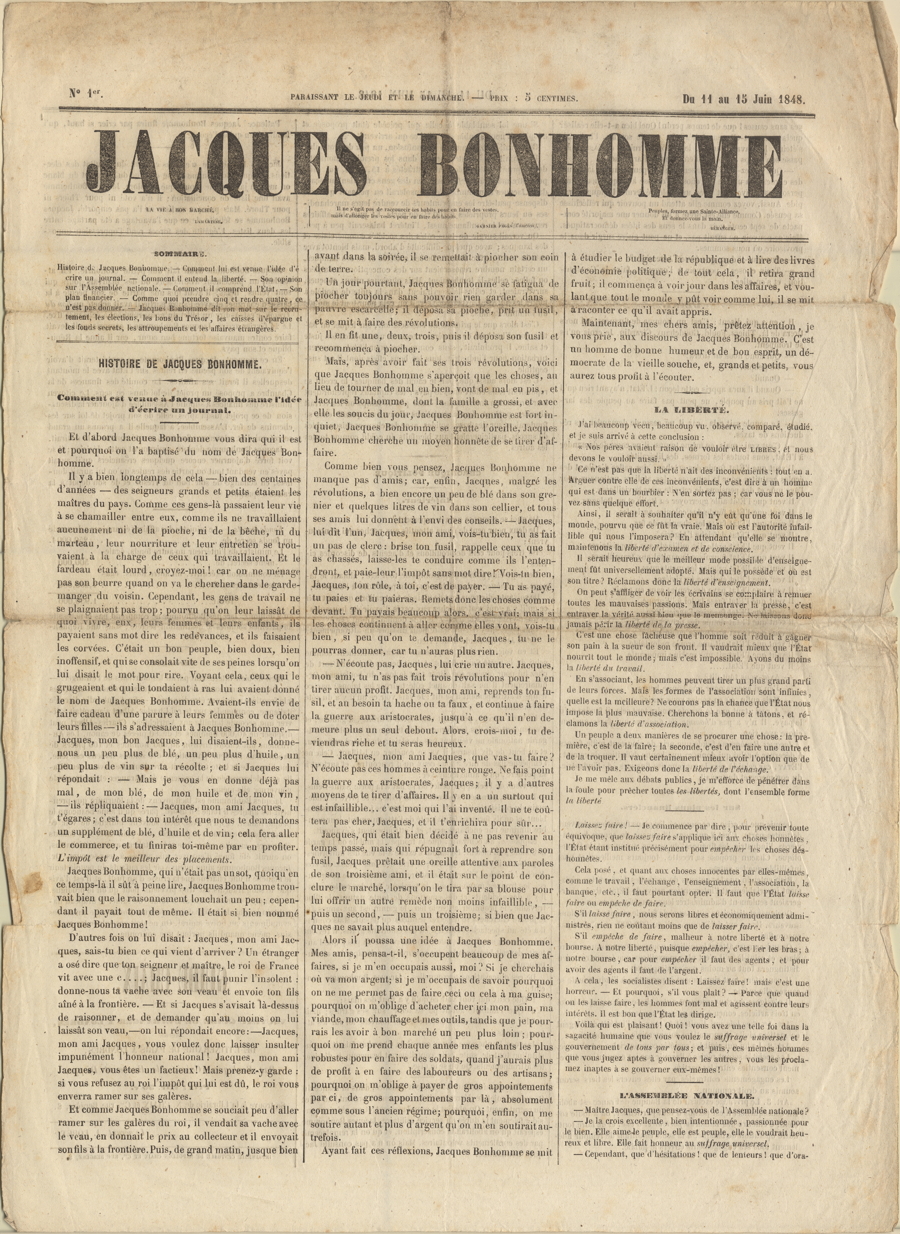

He immediately took to the streets in Feb. 1848 and again in June 1848 to hand out small magazine La République française urging workers not to be duped by socialist ideas and to support limited govt. and free trade, and low taxes (“la vie à bon marché” (life at low prices) was their slogan; his joint statement of republican principles in Rep. fr #1;

The provisional government wants a republic without ratification by the people. Today we have heard the people of Paris unanimously proclaim a republican government from the top of its glorious barricades, and we are of the firm conviction that the whole of France will ratify the wishes of the conquerors of February. But whatever might happen, even if this wish were to be misunderstood, we will keep the title which the voice of all the people have thrown to us. Whatever the form of government which the nation decides upon, the press ought henceforth remain free, no longer will any impediment be imposed upon the expression of thought. This sacred liberty of human thought, previously so impudently violated, will be recognised by the people, and they will know how to keep it. Thus, whatever might happen, being firmly convinced that the republican form of government is the only one which is suitable for a free people, the only one which allows the full and complete development of all kinds of liberty, we adopt and will keep our title: THE FRENCH REPUBLIC. (1st issue of La République française 26 Feb. 1848)

Their demands in République française:

- end to economic restrictions and privilege

- labour should be completely free, no more laws against unions

- Universal suffrage

- No more state funded religions

- absolute freedom of education

- Freedom of commerce

- No more conscription

- Inviolable respect for property

Stuck up wall posters around Paris; debated with socialists in a political club “The Club for the Freedom of Working” which had to close because they got beaten up by “communist thugs” (GdM).

Mottos at the head of the paper:

- “La vie à bon marché" (Lamartine) - (Life at reasonable (low) prices)

- “Il ne s’agit pas de raccourcir les habits pour en faire des vestes, mais d’allonger les vestes pour en faire des habits." (Garnier Pagès (l’ancien)) - (It is not a question of shortening one’s clothes in order to make jackets, but to lengthen one’s jackets to make clothes.)

- “Peuples, formez une Sainte-Alliance, Et donnez-vous la main." (Béranger) (People (of the world), form a Holy Alliance and join hands!)

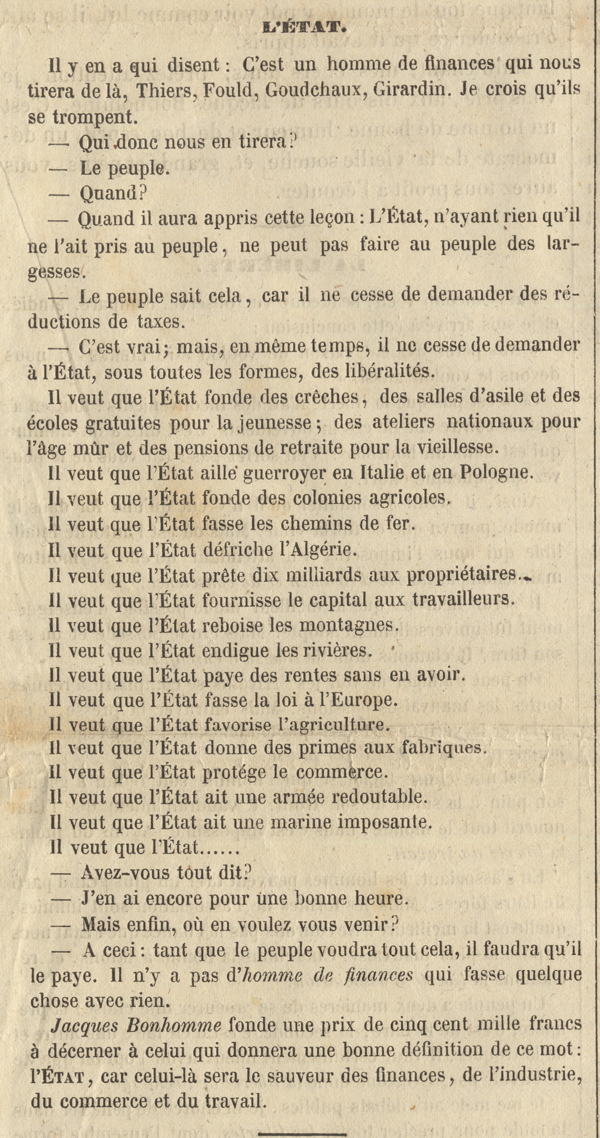

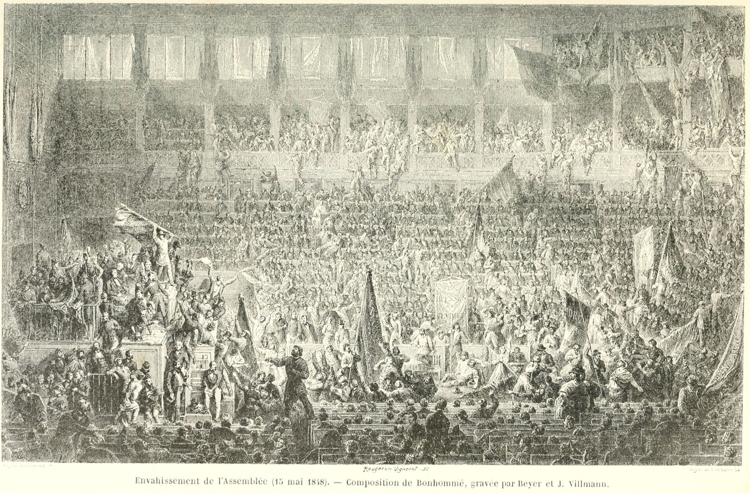

Page 2 contained the first version of what would become one of FB’s best known essays, “L’État” (The State) [1er numéro du Jacques Bonhomme, du 11 au 15 juin 1848.] CW2 8 http://oll.libertyfund.org/titles/2450#lf1573-02_label_195

“The State” (draft) [June 1848]:

“(the people have to learn) this lesson: since the state has nothing it has not taken from the people, it cannot distribute largesse to the people.”

“The people know this, since they never cease to demand reductions in taxes.”

“That is true, but at the same time, they never cease to demand handouts of every kind from the state.

They want the state to found crèches, infant schools and free schools for our youth, national workshops for those that are older and retirement pensions for the elderly.

They want the state to go to war in Italy and Poland.

They want the state to found farming colonies.

They want the state to build railways.

They want the state to bring Algeria into cultivation.

They want the state to lend ten billion to land owners.

They want the state to supply capital to workers.

They want the state to replant the forests on mountains.

They want the state to build embankments along the rivers.

They want the state to make payments without receiving any.

They want the state to lay down the law in Europe.

They want the state to support agriculture.

They want the state to give subsidies to industry.

They want the state to protect trade.

They want the state to have a formidable army.

They want the state to have an impressive navy.

They want the state to …”

“Have you finished?”

“I could go on for another hour at least.”

“But what is the point you are trying to make?”

“This. As long as the people want all of this, they will have to pay for it. There is no financial man alive who can do something with nothing.”

Twice he witnessed at first hand the shooting of hundreds of protesters by the French army on the streets of Paris which used artillery to break up the street barricades. At one point he used his position as an elected member of the Chamber of Deputies to call for a cease-fire so he and his friends could drag the dead and wounded into the side streets to get shelter from the army’s bullets and cannon fire.

27 February 1848, Paris

As you (Mme. Marsan) will see in the newspapers, on the 23rd everything seemed to be over. Paris had a festive air; everything was illuminated. A huge gathering moved along the boulevards singing. Flags were adorned with flowers and ribbons. When they reached the Hôtel des Capucines, the soldiers blocked their path and fired a round of musket fire at point-blank range into the crowd. I leave you to imagine the sight offered by a crowd of thirty thousand men, women, and children fleeing from the bullets, the shots, and those who fell.

An instinctive feeling prevented me from fleeing as well, and when it was all over I was on the site of a massacre with five or six workmen, facing about sixty dead and dying people. The soldiers appeared stupefied. I begged the officer to have the corpses and wounded moved in order to have the latter cared for and to avoid having the former used as flags by the people when they returned, but he had lost his head.

The workers and I then began to move the unfortunate victims onto the pavement, as doors refused to open. At last, seeing the fruitlessness of our efforts, I withdrew. But the people returned and carried the corpses to the outlying districts, and a hue and cry was heard all through the night. The following morning, as though by magic, two thousand barricades made the insurrection fearsome. Fortunately, as the troop did not wish to fire on the National Guard, the day was not as bloody as might have been expected.

All is now over. The Republic has been proclaimed. You know that this is good news for me. The people will govern themselves.

[CW 1, 93. Letter to Mme Marsan, 27 February 1848, p. 142. <oll.libertyfund.org/title/2393/225765>]

And again a few months later during the June Days riots:

29 June 1848, Paris

Cables and newspapers will have told you (Julie Marsan) all about the triumph of the republican order after four days of bitter struggle.

I shall not give you any detail, even about me, because a single letter would not suffice.

I shall just tell you that I have done my duty without ostentation or temerity. My only role was to enter the Faubourg Saint-Antoine after the fall of the first barricade, in order to disarm the fighters. As we went on, we managed to save several insurgents whom the militia wanted to kill. One of my colleagues displayed a truly admirable energy in this situation, which he did not boast about from the rostrum.”

[CW 1, 104. Letter to Mme Marsan, 29 June 1848, pp. 156–7. <oll.libertyfund.org/title/2393/225787>.]

Never gave up his belief in the liberal principles of the French revolution of 1789; admired American republican experiment - except for slavery and high tariff policy!! Very active in Constituent Assembly (April 1848) and National Assembly (June 1849). Served as VP of Finance Committee until his health gave out (couldn’t speak). In Chamber he got caught between the Left (socialists) and the Right (Party of Order, supporters of Napoleon and Monarch). Voted with right on tax and economic issues, but with left on civil liberties.

Three examples:

- speech in Chamber defending rights of workers to forms unions (freedom of assembly) CW2 17 “The Repression of Industrial Unions” pp. 348–61 http://oll.libertyfund.org/titles/2450#lf1573-02_label_424.

- Example of his commitment to freedom of speech. After invasion of Chamber by supporters of the socialist Louis Blanc (attempted coup after April election, paraded LB around chamber on their shoulders), chamber debated how to punish LB; FB one of the few to defend his right to speak and protest even though he was his arch-intellectual enemy

- speeches and writings calling for cuts to taxes which fell hardest on poor - tax on salt, alcohol; and tariffs on food and clothing. See CW@ 16 “Speech on the Tax on Wines and Spirits”, pp.328–47 http://oll.libertyfund.org/titles/2450#lf1573-02_label_408

The reason I am showing you this is because FB was one of the Deputies to come to Louis Blanc’s defence when he was threatened with loss of his parliamentary privileges would would open the way to him being arrested, prosecuted, and imprisoned for political crimes. After the elections of April the socialists were disappointed with the their poor results and some decided to march in protest and then invaded the Chamber hoping to force the government to appoint more socialist ministers or even stage a coup d’état. Blanc’s socialist supporters stormed the Chamber with guns, and then paraded LB around chamber on their shoulders. The Chamber debated how to punish LB; FB one of the few to defend his right to speak and protest even though he was his arch-intellectual enemy.

Bastiat the innovative economic theorist↩

There is Bastiat the radically innovative economic theorist who did not live long enough to complete his magnum opus on economic theory, *Economic Harmonies.” What he did manage to write showed that he had anticipated key insights of both the Austrian and the Public Choice schools of economic thought and was well-ahead of time in pushing the theoretical boundaries of economic thought.

Had important general economic insights:

- idea of opportunity cost (seen and unseen)

- a new theory of rent (nothing special about land).

- the rejection of Malthusian limits to population growth.

- the interconnectedness of all economic activity (“ricochet effect”).

- idea of ceteris paribus (all other things being equal)

- his theory of the “economic sociology” of the State.

- the quantification of the impact of economic events (“double incidence of loss”).

Insights later taken up by Austrian school (see my other paper on this):

- his methodological individualism; idea of abstract theory of human action (“Crusoe economics”).

- ideas about subjective value theory

- the idea of “spontaneous” or “harmonious” order (the feeding of Paris)

- unintended consequences of govt. intervention

- the knowledge problem of central/govt. planning

- the interdependence or interconnectedness of all economic activity (“I, Carpenter” in EH)

- the transmission of economic information through the economy; flows of knowledge via prices?? (hydraulic metaphors)

Public Choice insights:

- self-interest of bureaucrats and politicians;

- state provides benefits for vested interest groups;

- Malthusian limit to growth of state power;

- activity of parties/factions/coalitions disrupt democracy

The “Seen” and the “Unseen” is perhaps his best known concept. Clear statement of the issue of “opportunity costs”:

From What is Seen & What is not Seen (1850). Chapter 1: The Broken Window.

But if, by way of deduction, as is often the case, the conclusion is reached that it is a good thing to break windows, that this causes money to circulate and therefore industry in general is stimulated, I am obliged to cry: “Stop!” Your theory has stopped at what is seen and takes no account of what is not seen. What is not seen is that since our bourgeois has spent six francs on one thing, he can no longer spend them on another. What is not seen is that if he had not had a windowpane to replace, he might have replaced his down-at-heel shoes or added a book to his library. In short, he would have used his six francs for a purpose that he will no longer be able to….

Bastiat the theorist of classical liberal class analysis and “legal plunder”↩

There is Bastiat the radical theorist of class domination and exploitation of society by privileged elites. A contemporary of Karl Marx, Bastiat had a much better thought out and consistent theory of class based upon his idea of “plunder”, whereby the state and privileged groups who have access to state power take by force the property of productive citizens for their own benefit. His planned History of Plunder was never finished, although he left enough fragments for us to piece together what it might have looked like. Conservatives like to paint FB as very religious. More of a deist; hatred of theocratic plunder; church duping the masses with false promises.

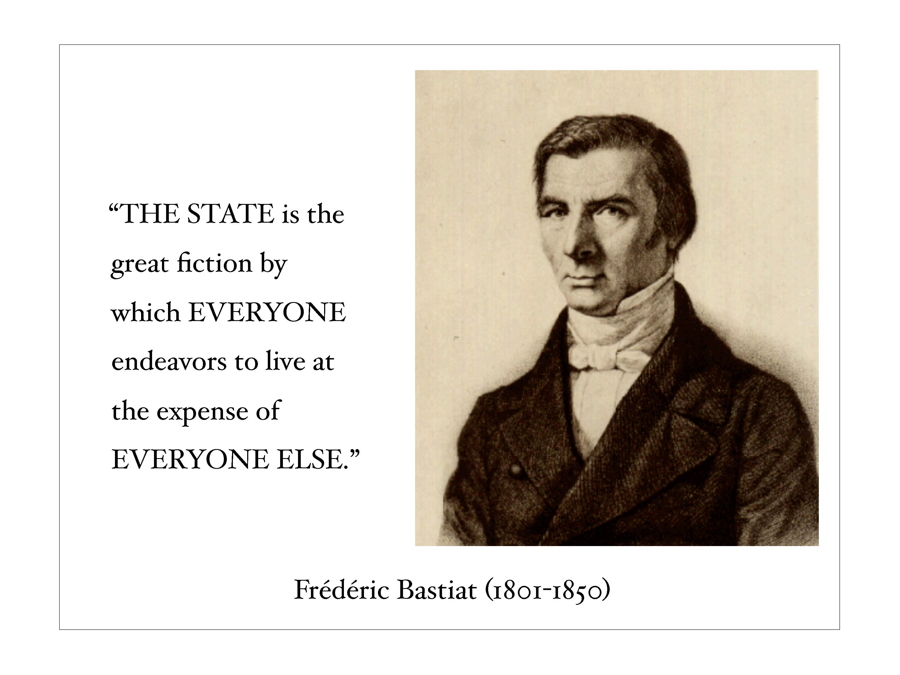

THE STATE is the great fiction by which EVERYONE endeavours to lives at the expense of EVERYONE ELSE

L’État, c’est la grande fiction à travers laquelle tout le monde s’efforce de vivre aux dépens de tout le monde.

“The State” CW 7, p. 97, http://oll.libertyfund.org/titles/2450#Bastiat_1573-02_671.

Structure of his general theory of plunder, dupes, sophisms, etc

- the ruling elite (the plunderers) impose their rule over others by “force” or “deception” (“la ruse”) [Q: ES2 I “Physiology of Plunder]

- the people (“les dupes”) are deceived by “sophisms” to justify intervention in the economy, taxation, war, colonies, etc

- in the new age of democratic politics and socialism the State had become “the great fiction by which everyone endeavours to live at the expence of everybody else” [Q: “The State” (Sept. 1848)]

- stage theory of state plunder: war, slavery, feudalism, mercantilism, socialism

- Malthusian-type limits to plunder; fight back by plundered

- planned to write A History of Plunder after EH (“economic disharmonies”); see my reconstruction

- most developed sketch was for “theocratic plunder”

FB developed a new vocabulary to describe “Taking” and “Deceiving”:

The vocabulary of “Taking”:

- “la spoliation” (plunder); “spolier” (to plunder); “les spoliateurs” (the plunderers)

- “dépouiller“(to dispossess); ”voler“ (to steal); ”piller“ (to loot or pillage), ”filouter" (filching), “violer” (rape)

- and variants such as “le vol de grand chemin” (highway robbery)

The vocabulary of “Deceiving”:

- “les dupes” (the dupes, or those who are deceived)

- “la ruse” (deception, fraud)

- purpose of his writing was to show the “dupes” (those who are deceived) that “Sophisms” (sophistical arguments and fallacies) were being used by the plunderers (“les spoliateurs”) with “la ruse” (deception, fraud) to justify and disguise what they are doing.

Quote from Conclusion to ES1 (November 1845) (LF ed.):

Men have an immoderate love for pleasure, influence, esteem, and power, in a word, for wealth.

And at the same time, they are driven by an immense urge to procure these things for themselves at the expense of others.

But these others, who are the general public, have no less an urge to keep what they have acquired, provided that they can and they know how to.

Plunder, which plays such a major role in the affairs of the world, has thus only two things which promote it: force and fraud, and two things which limit it: courage and enlightenment.

Force used for plunder forms the bedrock upon which the annals of human history rest. Retracing its history would be to reproduce almost entirely the history of every nation…Only, the thing which promotes it has changed; it is no longer by force but by fraud that public wealth can be seized.

In order to steal from the public it it first necessary to deceive them. To deceive them it is necessary to persuade them that they are being robbed for their own good; it is to make them accept imaginary services and often worse in exchange for their possessions. This gives rise to sophistry. Theocratic sophistry, economic sophistry, political sophistry and financial sophistry. Therefore, ever since force has been held in check, sophistry has been not only a source of harm, it has been the very essence of harm. It must in its turn be held in check. And to do this the public must become cleverer than the clever, just as it has become stronger than the strong.

Developed idea of “legal plunder”. Distinguished between two main types of plunder:

- “illegal plunder” by thieves, robbers, and highway men and which was prohibited by law

- “legal plunder” by the state under the protection of the legal system which exempted sovereigns and government officials from the usual prohibition of taking other people’s property by force

Believed that legal plunder corrupts the entire system of law.

Quote from The Law (La Loi) (June 1850) (LF ed.) CW2 9 http://oll.libertyfund.org/titles/2450#Bastiat_1573-02_821:

But what form of Plunder was he wishing to talk about? For there are two forms. There is plunder outside the law and legal plunder….

Sometimes the law takes the side of plunder. Sometimes it carries it out with its own hands, in order to spare the blushes, the risk and scruples of its beneficiary. Sometimes it mobilizes this whole system of magistrates, police, gendarmes and prison to serve the plunderer and treats the victim who defends himself as a criminal. In a word, there is legal plunder …

Discusses the main kinds of plunder in human history in ES2 I “The Physiology of Plunder” (1848) (LF ed.):

You need name only a few of the most clear-cut forms of Plunder to show the place it occupies in human affairs.

First of all, there is WAR. Among savage peoples, the victor kills the vanquished in order to acquire a right to hunt game that is if not incontestable, at least uncontested.

Then there is SLAVERY. Once man grasps that it is possible to make land fertile through work, he strikes this bargain with his fellow: “You will have the fatigue of work and I will have its product.”

Next comes THEOCRACY. “Depending on whether you give me or refuse to give me your property, I will open the gates of heaven or hell to you.”

Lastly, there is MONOPOLY. Its distinctive characteristic is to allow the great social law, a service for a service, to continue to exist, but to make force part of the negotiations and thus distort the just relationship between the service received and the service rendered.

FB worries that new socialist (welfare) state will universalise plunder in The Law (La Loi) (June 1850) (LF ed.) http://oll.libertyfund.org/titles/2450#Bastiat_1573-02_830:

It is absolutely necessary for this question of legal plunder to be settled, and there are just three alternatives:

That the minority plunders the majority;

That everyone plunders everyone else;

That no one plunders anybody.

You have to choose between partial plunder, universal plunder, and no plunder at all. The law can pursue one of these three alternatives only.

Partial plunder. This is the system that prevailed for as long as the electorate was partial and is the system to which people return to avoid the invasion of socialism.

Universal plunder. This is the system that threatened us when the electorate became universal with the masses having conceived the idea of making laws along the same lines as their legislative predecessors.

Absence of plunder. This is the principle of justice, peace, order, stability, conciliation, and common sense that I will proclaim with all my strength, which is, alas, very inadequate, and with my lungs until my final breath.

If he had he lived longer (another 20 years as Marx did) might he have become the “Karl Marx of the classical liberal movement”?

He had plans to write at least three volumes on “social harmonies”, “economic harmonies”, and “disharmonies” (also known as his “History of Plunder”)

Volume one would be a general theory of how human society functions, called Social Harmonies with chapters on:

- responsibility

- solidarity

- self interest or the “social motor or driving force”

- perfectibility

- public opinion

- the relationship between political economy and morality, politics, legislation, and religion

Volume two would be his economic theory, called Economic Harmonies with chapters on:

- producers and consumers

- individualism and sociability

- the theory of Rent

- money

- credit

- wages

- savings

- population

- private services, public services

- taxation

- on machines

- free trade

- on middlemen

- raw materials and finished products

- on luxury

Volume three would deal with disrupting factors or “disharmonies”, perhaps called The History and Theory of Plunder with chapters on:

- plunder

- war

- slavery

- theocracy

- monopoly

- governmental exploitation

- false fraternity or communism

Bastiat’s vision of Liberty as “the sum of all freedoms”, as “a systematic and harmonious whole”↩

FB “I love all forms of freedom”

Liberty broadly understood: not just political freedoms (vote, speech, constitutional guarantees, rule of law), or economic (free trade, low taxes, little regulation), but also social freedoms. All these “freedoms” made up an an interlocking whole. An attack on one is attack on others; not just economic or political (older school of CL).

In a rather ironic draft preface to a book (Economic Harmonies) he had not yet written in September 1847 he gives a glimpse of the interconnectedness of the different aspects of human liberty http://oll.libertyfund.org/titles/2393#Bastiat_1573-01_1612:

I love freedom of trade as much as you do. But is all human progress encapsulated in that freedom? In the past, your heart beat for the freeing of thought and speech which were still bound by their university shackles and the laws against free association. You enthusiastically supported parliamentary reform and the radical division of that sovereignty, which delegates and controls, from the executive power in all its branches. All forms of freedom go together. All ideas form a systematic and harmonious whole, and there is not a single one whose proof does not serve to demonstrate the truth of the others. But you act like a mechanic who makes a virtue of explaining an isolated part of a machine in the smallest detail, not forgetting anything. The temptation is strong to cry out to him, “Show me the other parts; make them work together; each of them explains the others… (Draft Preface to EH 1847) CW1 4 http://oll.libertyfund.org/titles/2393#Bastiat_1573-01_1613

Also a list of things he believed in CW1 4 http://oll.libertyfund.org/titles/2393#Bastiat_1573-01_1612:

Peoples are not governed by equations but by generous instincts, by sentiment and sympathy. It was necessary to present them with the successive dismantling of the barriers which divide men into mutually hostile communities, into jealous provinces, or into warring nations. It was necessary to show them the merging of races, interests, languages, ideas, and the triumph of truth over error, witnessed in the intellectual shock it effects, with progressive institutions replacing the regime of absolute despotism and hereditary castes, wars eliminated, armies disbanded, moral power replacing physical force, and the human race preparing itself through unity for the destiny reserved for it. This is what would have inflamed the masses, and not your dry proofs.

My image of “The Classical Liberal Tradition” - Liberty is made up of political, economic, and social freedoms

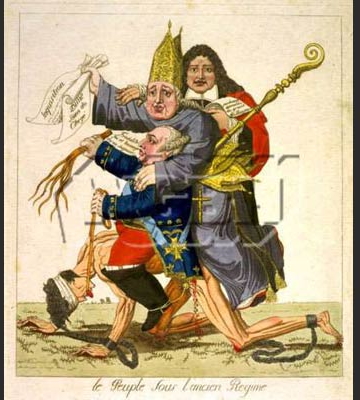

Bastiat’s opposition to “theocratic plunder” by the Catholic Church↩

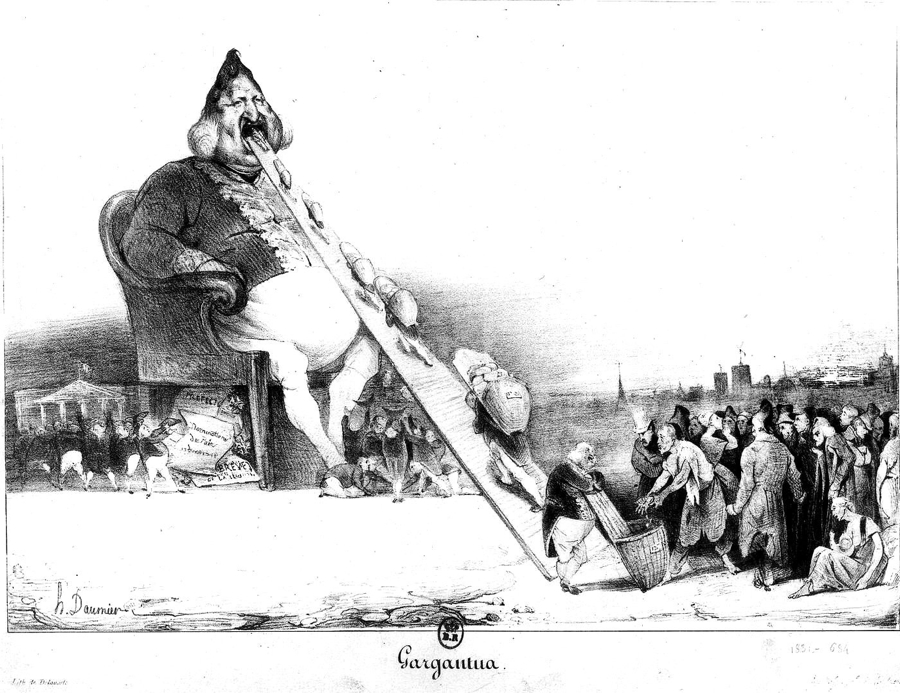

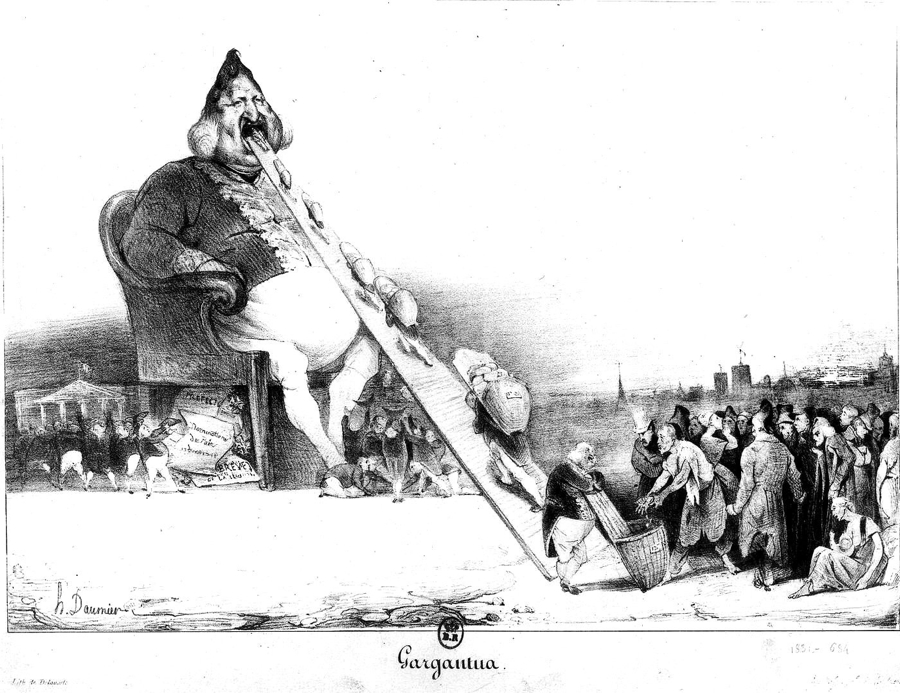

The People in the Old Regime being plundered by the Crown, the Church, and the Law

His opposition to the Catholic Church’s “theocratic plunder” is very powerful and angry.

Conservatives think he is more religious than I think he was. He refers to Providence as often as he refers to god, which suggests he was a deist (universe shows “intelligent design”, creator of natural laws which govern physical and social worlds). He never mentions anything about doctrinal matters.

He had a crisis of faith in his youth, but did he ever get it all back? His cousin was a Catholic priest who gave him last rites in Rome; family pressure?? or real conviction??

I would explain references to god in his last work (La Loi) partly conventional, partly growing fear of pain and death in his final months; a kind of “Pascal’s wager” for economists, “Bastiat’s bet”?

“Theocratic plunder” was the most developed sketch of the different historical forms plunder had taken.

Theocratic Plunder & Theological Sophisms:

- over centuries Church had developed a system of plunder “on a grand scale” and a matching set of “sophisms” to justify this

- “theological plunder” - obligatory tithing, acquisition of land from the Crown, control of courts, role in supporting war and colonisation

- “theological sophisms” - fraud and deception practised by priests who alone claimed to be able to ensure the passage to the afterlife of believers

- religion had become “the instrument of the Priests” (instead of the opposite)

- challenge to system of “theocratic plundering” came from the invention of the printing press which broke the monopoly of information held by Church and led to the enlightening of “the dupes”

Quote in ES2 I “The Physiology of Plunder” (1848) (LF ed.):

I will review briefly a few of the forms of plunder that are exercised by Fraud on a grand scale.

The first to come forward is Plunder by theocratic fraud.

What is this about? To get people to provide real services, in the form of foodstuffs, clothing, luxury, consideration, influence and power, in return for imaginary ones.

If I said to a man “I am going to provide you with some immediate services”, I would have to keep my word, otherwise this man would know what he was dealing with and my fraud would be promptly unmasked.

But if I told him “In exchange for your services, I will provide you with immense services, not in this world but in the next. After this life, you will be able to be eternally happy or unhappy and this all depends on me; I am an intermediary between God and his creation and can, at will, open the gates of heaven or hell to you.” Should this man believe me at all, he is in my power.

This type of imposture has been practiced widely since the beginning of the world, and we know what degree of total power Egyptian priests achieved.

It is easy to see how impostors behave. You have to only ask yourself what you would do in their place.

… I would pass for an emissary of God with absolute discretion over the future destiny of men.

… I would go further; since reason would be my most dangerous enemy, I would forbid the use of reason itself, at least when applied to this awesome subject…

I would grant to my accomplices and myself the monopoly of all knowledge…

I would take care to invent an institution which would, day after day, enable me to enter into the secret of all consciences…

Should things reach this pass, it is clear that this people would belong to me more surely than if they were my slaves. Slaves curse their chains, while my people would bless theirs, and I would have succeeded in imprinting the stamp of servitude not on their foreheads, but in the depths of their conscience.

The Modern State and Plunder:

- plunder makes sense when a minority plunders the majority (slavery, serfdom, monopoly)

- in the modern democratic and socialist State (post 1848) it makes no sense for the majority to attempt to plunder the majority - the “personification” of the State

- major essay “The State” (June, September 1848) - the State “has two hands, one to receive and the other to give; in other words, the rough hand and the gentle hand”

- famous slogan - “THE STATE is the great fiction by which EVERYONE endeavors to live at the expense of EVERYONE ELSE”

Legal Plunder has become Universal discussed in The Law (La Loi) (June 1850) (LF ed.) http://oll.libertyfund.org/titles/2450#Bastiat_1573-02_798:

Up to now, legal plunder has been exercised by the minority over the majority as can be seen in those peoples in which the right to pass laws is concentrated in just a few hands. However, it has now become universal and equilibrium is being sought in universal plunder. Instead of the injustice existing in society being rooted out, it has become generalized. As soon as underprivileged classes recover their political rights, their first thought is not to rid themselves of plunder (that would suppose that they had an enlightenment that they cannot have) but to organize a system of reprisals against other classes and to their own detriment, as though it is necessary for a cruel retribution to strike them all, some for their iniquity and others for their ignorance, before the reign of justice is established.

No greater change or misfortune could therefore be introduced into society than this: to have a law that has been converted into an instrument of plunder.

Worried that the people had “personified” the state as a kind of all-caring father of the nation in The State (L’État) (June 1848) (LF ed.) CW2 7 http://oll.libertyfund.org/titles/2450#Bastiat_1573-02_682:

If I have taken the liberty of criticizing the opening words of our Constitution, it is because it is not a question, as one might believe, of wholly metaphysical subtlety. I claim that this personification of the state has been in the past and will be in the future a rich source of calamities and revolutions.

Here is the public on one side and the state on the other, considered to be two distinct beings, the latter obliged to spread over the former and the former having the right to claim from the latter a flood of human happiness. What is bound to happen?

In fact, the state is not and cannot be one-handed. It has two hands, one to receive and the other to give; in other words, the rough hand and the gentle hand. The activity of the second is of necessity subordinate to the activity of the first. Strictly speaking, The state is able to take and not give back. This has been seen and is explained by the porous and absorbent nature of its hands, which always retain part and sometimes all of what they touch. But what has never been seen, will never be seen and cannot even be conceived is that the state will give to the general public more than it has taken from them. It is therefore a sublime folly for us to adopt toward it the humble attitude of beggars. It is radically impossible for it to confer a particular advantage on some of the individuals who make up the community without inflicting greater damage on the community as a whole.

Bastiat’s impact on the modern libertarian movement - Circle Bastiat in NYC in 1950s (Rothbard, Liggio, Raico)↩

The rediscovery of Bastiat’s work by R.C. Hoiles in 1944 - 2 TPs

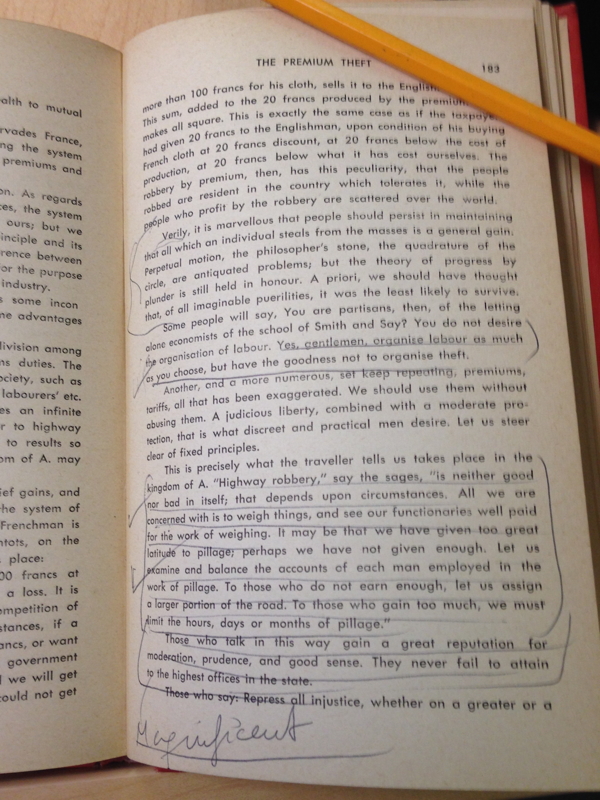

“Magnificent!” - Rothbard’s annotations of Bastiat’s “Theft by Subsidy” (Hoiles edition 1944)

I photographed these annotations in the Rothbard Library at the Mises Institute , Auburn, Alabama in March 2016.

The Circle Bastiat, NYC 1953–59: Ralph Raico, Murray Rothbard, Leonard Liggio, George Reisman, Ronald Hamowy, Robert Hessen

Very important reprint because of its influence on the groups of libertarians in NYR around Mises and Rothbard - “Circle Bastiat”

Influenced their ideas about class analysis (Rothbard, Liggio, Raico)

On Rothbard - rethinking of basis of human action - Crusoe economics from FB

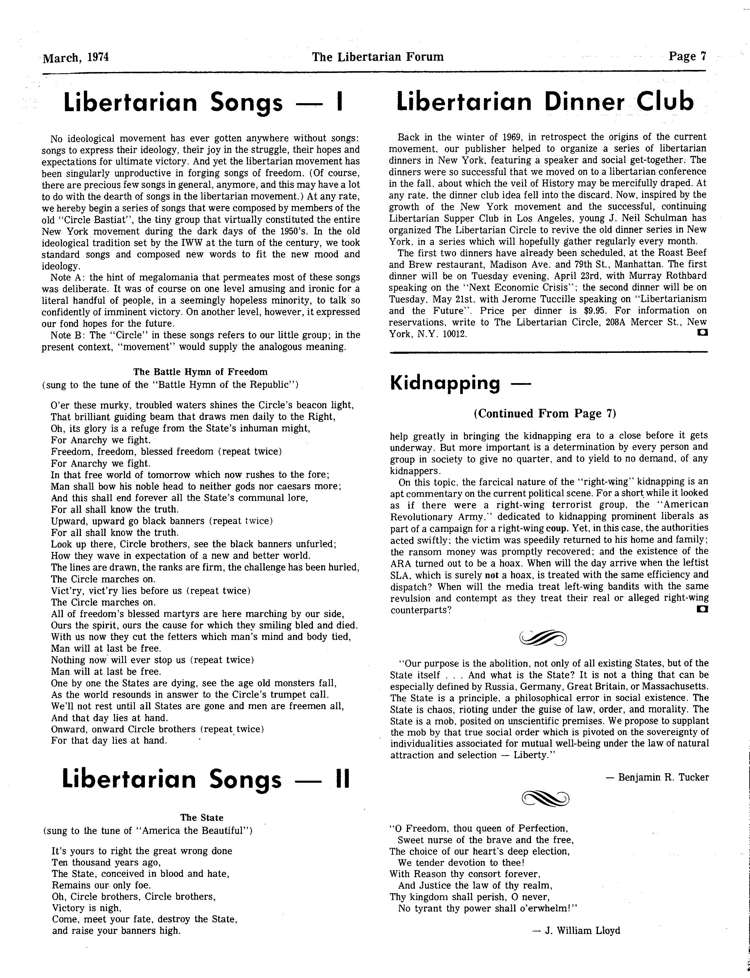

Had the same sense of radical passion to cause - “Libertarian Songs” (Libertarian Forum, March 1974, p. 7) modelled on Bastiat and Béranger?

Circle Bastiat Songs

“The State” (sung to the tune of “America the beautiful”)

It’s yours to right the great wrong done

Ten thousand years ago,

The State, conceived in blood and hate,

Remains our only foe.

Oh, Circle brothers, Circle brothers,

Victory is nigh,

Come, meet your fate, destroy the State,

and raise your banners high.

Bastiat’s Courage and Dignity in Death↩

Finally, there is the manner in which Bastiat coped with his fatal illness, namely with dignity and courage. This is not so much a “radical” but a very admirable aspect of his character - a man of courage who faced his painful and incurable throat condition by refusing to give up and working to the end to finish his treatise.

Some Ironies to Reflect upon↩

Irony 1↩

- the desecration of his memorial by the Nazis in 1942 (melting down his bust to make tanks)

- at the same time (1944) his work is rediscovered in So. California by R.C. Hoiles, which will have a huge impact on post-war American conservative/libertarian thought

Before and after pictures of FB’s monument

Contemporaneous rediscovery of FB’s work by R.C. Hoiles in 1944

Irony 2↩

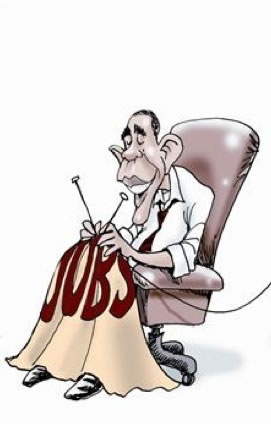

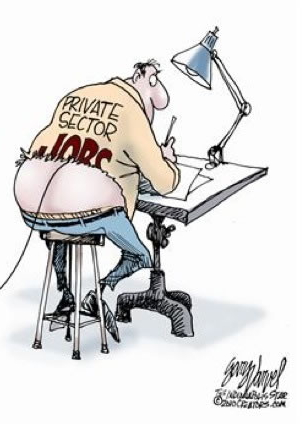

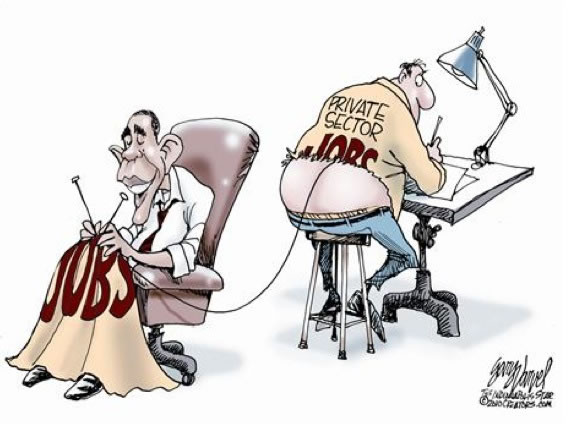

Although his story of “The Broken Window” is so clear and understandable the myth of it stimulating economic output continues to this day. Every time there is a natural disaster like a hurricane of earthquake some journalists (even economists) will trot out the same myths (Krugman, Morici). Example of “Zombie economics” - bad economic ideas which are impossible to kill.