FRÉDÉRIC BASTIAT,

What is Seen and What is Not Seen:

or Political Economy in One Lesson (1850)

The Students Edition.

(April 2025 Draft)

|

|

[Created: 12 April, 2025]

[Updated: 14 April, 2025] |

The Guillaumin Collection

|

This title is part of “The Guillaumin Collection” within “The Digital Library of Liberty and Power”. It has been more richly coded and has some features which other titles in the library do not have, such as the original page numbers, formatting which makes it look as much like the original text as possible, and a citation tool which makes it possible for scholars to link to an individual paragraph which is of interest to them. These titles are also available in a variety of eBook formats for reading on portable devices. |

Source

, What is Seen and What is Not Seen, or Political Economy in One Lesson. The Students Edition. Translated and edited by David M. Hart (The Pittwater Free Press, 2025).http://davidmhart.com/liberty/FrenchClassicalLiberals/Bastiat/Books/1850-CeQuonVoit/Bastiat_WSWNS1850.html

Frédéric Bastiat, What is Seen and What is Not Seen, or Political Economy in One Lesson. The Students Edition. Translated and edited by David M. Hart (The Pittwater Free Press, 2025).

A translation of Frédéric Bastiat, Ce qu’on voit et ce qu’on ne voit pas, ou l’Économie politique en une leçon. Par M. F. Bastiat. Représentant du Peuple à l’Assemblée Nationale, Membre correspondant de l’Institut (Paris: Guillaumin, 1850).

This title is also available in a facsimile PDF and enhanced HTML of the French original and various eBook formats - HTML, PDF, and ePub.

This book is part of a collection of works by Frédéric Bastiat (1801-1850).

Table of Contents

- [Introduction], p. 3

- I. The Broken Window, p. 5

- II. The Dismissal of Troops, p. 9

- III. Taxation, p. 13

- IV. Theatres and the Fine Arts, p. 1

- V. Public Works, p. 27

- VI. Middlemen, p. 30

- VII. Trade Restrictions, p. 40

- VIII. Machines, p. 47

- IX. Credit, p. 56

- X. Algeria, p. 61

- XI. Saving and Luxury, p. 67

- XII. Right to a Job and the Right to a Profit, p. 76

- Endnotes

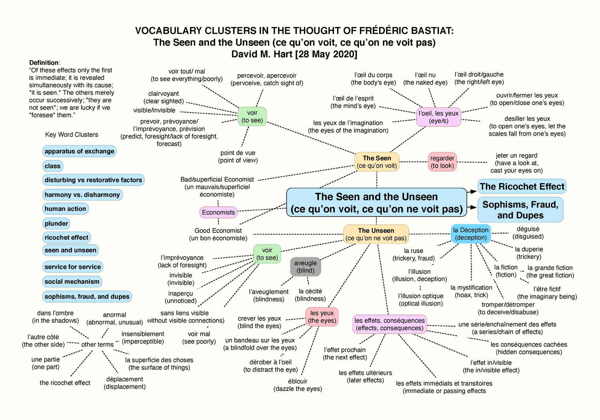

Vocabulary Clusters in the Thought of Frédéric Bastiat: The Seen and the Unseen (ce qu'on voit et ce qu'on ne voit pas)↩

See a larger version of this image (3,000 px wide).

[3]

[Introduction] [1]

In the economic realm, an act, a habit, an institution, a law does not produce only one effect, but a series of effects. Of these effects, only the first is immediate; it manifests itself simultaneously with its cause, it is seen. The others unfold only successively, they are not seen, and it is fortunate if they are foreseen! [2]

Here is the whole difference between a bad economist and a good one: the former confines himself to the visible effect; the other takes account both of the effect which is seen and of those it is necessary to foresee.

But this difference is enormous, for it almost always happens that when the immediate consequence is favorable, the later consequences are disastrous, and vice versa. From this it follows that the bad economist pursues a small present good which will be followed by a great harm to come, whereas the [4] good economist pursues a great good to come, at the risk of a small present harm.

Moreover, it is the same in our personal well-being and moral behaviour. Often, the sweeter the first fruit of a habit, the more bitter the others. Witness: debauchery, laziness, prodigality. So when a man, struck by the effect that one sees, has not yet learned to discern that which one does not see, he gives himself over to harmful habits, not only by inclination, but by deliberate calculation.

This explains the inevitably painful evolution of humanity. Ignorance surrounds our cradle; thus it determines our actions by their first consequences, which are the only ones, at the outset, that we can see. Only over time do we learn to take account of the others. Two very different masters teach us this lesson: Experience and foresight. Experience governs effectively but harshly. It teaches us all the effects of an act by making us feel them, and we cannot fail to end up knowing that fire burns, by getting burned over and over again. I would like, as far as possible, to replace this harsh teacher with a gentler one: foresight. That is why I will examine the consequences of certain economic phenomena, showing that for those which one sees there are also those which one does not see.

[5]

I. The Broken Window [3]

Have you ever witnessed the fury of good old Jacques Bonhomme [4] when his terrible son has succeeded in breaking a windowpane? If you’ve seen this spectacle, you’ve no doubt also noticed that all the bystanders, thirty of them, perhaps, seem to have made a pact to offer the unfortunate owner the same consolation:

“Every cloud has a silver lining. Accidents like this keep industry going. Everyone must make a living. What would become of glaziers if no one ever broke a window?”

Now, there is in this common expression of sympathy a whole theory that it's good to catch in flagrante delicto [5] in this very simple case, because it is exactly the same theory that, unfortunately, governs most of our economic institutions.

Suppose the damage costs six francs to repair. If it is claimed that the accident brings six francs to the glassmaking industry, that it encourages this industry to the tune of six francs, I agree, I do not contest it in any way, the reasoning is sound. The glazier will come, do his work, receive six francs, rub his hands, and bless the mischievous child in his heart. That is what is seen.

[6]

But if, by way of deduction, people arrive at the conclusion, as they so often do, that breaking windows is a good thing, that it makes money circulate, that it provides a general stimulus to industry, then I must cry out "halt!" Your theory stops at what is seen, it does not consider what is not seen.

What is not seen is that since our citizen has spent six francs on one thing, he can no longer spend them on another. What is not seen is that if he had not had a window to replace, he might have replaced his worn-out shoes or added a book to his library. In short, he would have used his six francs for something else that now will not happen.

Let us then do the accounts for industry in general.

With the window broken, the glass industry is stimulated to the extent of six francs; this is what is seen.

If the window had not been broken, the shoemaking industry (or any other) would have been stimulated to the extent of six francs; this is what is not seen.

And if one were to take into account what is not seen, because it is a negative fact, [6] just as much as what is seen, because it is a positive fact, it would be understood that there is no interest for industry in general, or for national labor as a whole, in whether windowpanes are broken or not.

[7]

Let us now do the accounts of Jacques Bonhomme. [7]

In the first case, that of the broken window, he spends six francs and enjoys, neither more nor less than before, the use of a window.

In the second case, if the accident had not happened, he would have spent six francs on shoes and enjoyed both the use of a pair of shoes and that of a window.

Now, since Jacques Bonhomme is part of society, we must conclude from this that, considered as a whole, and once all the work and his enjoyment of a good [8] have been tallied, society has lost the value of the broken window.

From which, by generalizing, we arrive at this unexpected conclusion: “society loses the value of objects which are uselessly destroyed”, and then at this aphorism that will make the protectionists' hair stand on end: “To break, to shatter, to squander something is not to encourage national labor,” or to put it more briefly: “destruction is not profit.”

What will you say to this, Moniteur industriel, [9] what will you say, disciples of that good man Mr. de Saint-Chamans, [10] who calculated so precisely how much industry would gain from the burning of Paris, given the number of houses that would have to be rebuilt? [11]

I regret disturbing his clever calculations, all the more so as he managed to have their spirit become part of our [8] legislation. But I would ask him to do his calculations again, this time accounting for what is not seen alongside what is seen.

The reader must take care to notice that there are not merely two characters, but three, in the little drama I have brought to his attention. [12] One, Jacques Bonhomme, represents the consumer who is reduced by some act of destruction to the enjoyment of one good instead of two. The second, in the character of the glazier, shows us the producer whose industry is encouraged by the accident. The third is the shoemaker (or some other tradesman) whose work is discouraged by the very same cause. It is this third character who is always kept in the shadows, and who, personifying what is not seen, is a necessary part of the problem. It is he who helps us understand how absurd it is to see profit in an act of destruction. It is he who will soon teach us that it is no less absurd to see profit in the restriction of trade restriction, which is after all only a partial form of destruction. Indeed, if you probe to the bottom of all the arguments advanced in its favor, you will find nothing but a paraphrase of this familiar saying: “What would become of the glaziers if no one ever broke windows?”

[9]

II. The Dismissal of Troops

It is the same for an entire nation as for one man. When a man wants to indulge himself, it is up to him to consider whether the satisfaction is worth the cost. For a nation, security is the greatest of goods. If, to obtain it, one must mobilize a hundred thousand men and spend a hundred million francs, [13] I have nothing to say. [14] It is an enjoyment purchased at the price of a sacrifice of some kind.

Let no one misunderstand the scope of my argument.

A representative proposes dismissing a hundred thousand men to relieve the taxpayers of a hundred million francs.

If one limits oneself to replying: “These hundred thousand men and these hundred million francsare indispensable to national security: it is a sacrifice; [15] but without this sacrifice, France would be torn apart by internal factions or invaded by foreign powers.”I have no objection to this argument, which may be true or false in fact, but which does not contain any theoretical economic heresy. The heresy begins when one attempts to represent the sacrifice itself as a benefit because it profits someone.

Now, I will be greatly mistaken if the author of the proposal [16] is not immediately followed by another orator rushing to the podium to say:

[10]

“Dismiss a hundred thousand men! Are you serious? What will become of them? What will they live on? Will it be paid work? But do you not know that work is scarce everywhere? That every field is overcrowded? Do you want to throw them onto the streets to increase competition and drive down wages? At a time when it is so hard to earn a meager living, isn’t it fortunate that the State gives bread to a hundred thousand individuals? Consider also that the army consumes wine, clothing, weapons, that it thereby spreads activity through the factories and the garrison towns, and that it is, ultimately, the Providence of its countless suppliers. Do you not shudder at the thought of destroying this immense industrial movement?”

This speech, as one can see, argues for retaining the hundred thousand soldiers, regardless of the necessity of their service, and on economic grounds. These are the points I intend to refute.

A hundred thousand men, costing taxpayers a hundred million francs, live and allow their suppliers to live to the extent that those hundred million francs are spread among them: this is what is seen.

But one hundred million francs taken from the pockets of the taxpayers stops those taxpayers and their suppliers from living to the extent that these one hundred million francs might have been be spread among them: that is what is not seen. Do the calculation, add up the figures, [11] and tell me, where is the gain for the mass of the people?

As for me, I will tell you where the loss lies, and to simplify matters, instead of speaking of a hundred thousand men and a hundred million francs, let us think in terms of one man and one thousand francs.

We are in the village of "A". The army recruiters make their rounds and take away a man. The tax collectors make their rounds as well and take away a thousand francs. The man and the money are both transported to Metz [17], the former intended to keep the latter alive for a year without doing anything. If you look only at Metz, oh! you are entirely right, the measure appears to be highly beneficial. But if you turn your gaze to the village of "A", your assessment will change, for unless you are blind, you will see that the village has lost a laborer and the thousand francs that paid for his work, along with the activity that the spending of those thousand francs used to generate in the surrounding area.

At first glance, it seems like the one thing is compensation for the other. The phenomenon that once occurred in the village now occurs in Metz, and that’s all. But here is where the loss lies: In the village, a man dug and plowed—he was a worker. In Metz, he performs about-face drills—he is a soldier. The money and its circulation remain the same in both cases; but in one, there were three hundred days of productive labor; in the other, there are three hundred days of unproductive labor, always assuming [12] that part of the army is not indispensable to public security.

Now, let the dismissal of the troops take place. You point out to me a surplus of one hundred thousand workers, the resulting increased competition among them for jobs, and the pressure it puts on wage levels. That is what you see.

But here is what you do not see. You do not see that dismissing one hundred thousand soldiers is not destroying one hundred million francs, it is returning it to the taxpayers. You do not see that throwing one hundred thousand workers onto the market is also, at the same time, throwing onto it the one hundred million francs meant to pay for their labor; so that, consequently, the same measure that increases the supply of labor also increases the demand for labor. From this it follows that your feared fall in wages is illusory. You do not see that before and after the dismissal of the troops, there are still one hundred million francs in the country corresponding to one hundred thousand men; that the only difference is this: before, the country gave the one hundred million francs to one hundred thousand men for doing nothing; afterward, it gives them the money for working. You do not see, finally, that when a taxpayer gives his money either to a soldier in exchange for doing nothing or to a worker in exchange for doing something, all the subsequent consequences of that money’s circulation are the same in both cases; only, in the second case, the taxpayer receives something, while in the first he receives [13] nothing. The result: a net loss for the nation.

The sophism I am combating here does not hold up to the test of its general application, which is the touchstone of one's principles. If, all things considered and all interests weighed, there is national profit in enlarging the army, then why not enlist under the flag the entire able-bodied population of the country?

III. Taxation

Have you never heard it said:

“Taxation is the best investment; it is like a fruitful rain. Look how many families it sustains, and follow in your mind the ricochets [18] it creates throughout industry, it’s endless, it’s life itself.”

To combat this idea, I am obliged to repeat the previous refutation. Political economy is well aware that its arguments are not so entertaining as to allow the motto Repetita placent (repetition makes something pleasing) to apply. So, like Basilio, [19] it has adapted the proverb for its own use, being thoroughly convinced that in its mouth: Repetita docent (repetition teaches).

The advantages that public officials [20] enjoy from being paid a salary, that is what is seen. The benefit that results for their suppliers, that is also seen. It dazzles the eyes of the body. [21]

But the disadvantage which taxpayers experience in making this money available, [22] that is what is not seen, and the [14] harm that results for their own suppliers, that too is not seen, though it should be blindingly obvious to the eyes of themind. [23]

When a government employee spends 100 sous more, that necessarily means a taxpayer spends 100 sous less. [24] But the spending of the government employee is seen, because it takes place; while the spending of the taxpayer is not seen, because, alas! he is prevented from making it.

You compare the nation to parched ground and the tax to a life-giving rain. So be it. But you should also ask where the source of this rain lies, and whether it is not precisely taxation that draws the moisture out of the soil and thus dries it up.

You should also ask whether the land can receive as much of this precious water through the rain as it loses through evaporation.

What is absolutely certain is that when Jacques Bonhomme hands over 100 sous to the tax collector, he receives nothing in return. When, later, a public official spends those 100 sous and returns them to Jacques Bonhomme, it is in exchange for something of equal value in wheat or in labor. [25] The final result for Jacques Bonhomme is a loss of 100 sous.

It is quite true that often, most often, if you like, the public official renders Jacques Bonhomme an equivalent service. In that case, there is no loss on either side; it is a simple exchange. Thus, my [15] argument in no way applies to useful functions. I say this: if you wish to create a public office, prove its utility. Demonstrate that the service it renders to Jacques Bonhomme is worth what it costs him. But, apart from that intrinsic utility, do not use as an argument the benefit it confers on the public servant, his family, and his suppliers; do not claim that it stimulates labor.

When Jacques Bonhomme gives 100 sous to a public official in exchange for a genuinely useful service, it is exactly like giving 100 sous to a shoemaker for a pair of shoes. A fair exchange; both parties are even. But when Jacques Bonhomme hands over 100 sous to a public official and receives no service in return, or worse, gets harassed, it is as if he had given the money to a thief. It is no use saying that the official will spend the 100 sous to the benefit of national labor; the thief would have done the same; and so would Jacques Bonhomme, had he not encountered either the extra-legal or the lawful parasite. [26]

Let us accustom ourselves, then, not to judge things only by what is seen, but also by what is not seen.

Last year, I was a member of the Finance Committee, [27] for under the Constituent Assembly, members of the opposition were not systematically excluded from all committees; [16] in this respect, the Constituent Assembly acted wisely. We heard M. Thiers say:

“I have spent my life opposing the men of the Legitimist and clerical parties. Since the common danger brought us together, since I have come to know them, to speak heart to heart with them, I have realized that they are not the monsters I once imagined.”

Yes, mistrusts become exaggerated, and hatreds intensify between parties that do not engage with each other; and if the majority were to allow a few members of the minority into the committees, perhaps both sides would come to see that their ideas are not so far apart, and above all, that their intentions are not as perverse as they suppose.

Be that as it may, last year I was on the Finance Committee. Whenever one of our colleagues proposed setting a modest salary for the President of the Republic, for ministers, or for ambassadors, the reply was:

“For the sake of government service itself, certain positions must be surrounded with splendor and dignity. That is how we attract men of merit. Countless unfortunate souls appeal to the President of the Republic, and it would place him in an awkward position to be forced to refuse them all. A degree of representation in ministerial and diplomatic salons is one of the cogs in the machinery of constitutional governments, etc., etc.”

[17]

Although such arguments may be debated, they certainly deserve serious consideration. They are based, rightly or wrongly, on the public interest; and as for me, I esteem them more than many of our self-styled Catos, [28] driven by a narrow spirit of penny-pinching or envy.

But what revolts my conscience as an economist, what makes me blush for the intellectual reputation of my country, is when we arrive (as we invariably do) at that absurd cliché, which is always favorably received:

“Besides, the luxury of high public officials encourages the arts, industry, and labor. The head of state and his ministers cannot host dinners and soirées without setting life in motion throughout every vein of the social body. To reduce their salaries is to starve Parisian industry, and by extension, the national industry.”

For heaven’s sake, gentlemen, at least show some respect for arithmetic, and do not come before the National Assembly of France, lest to its shame it applaud you, and assert that a sum changes according to whether you add it top-down or bottom-up.

What! I arrange with a ditch-digger to dig a trench in my field for 100 sous. Just as we are about to conclude, the tax collector takes my 100 sous and passes them on to the Minister [18] of the Interior. My deal is broken off, but the Minister will add another dish to his dinner. And you dare to claim that this official expenditure is a net gain to national industry! Can you not see that this is nothing but a mere displacement [29] of satisfaction and labor? It is true that a minister’s table is better stocked; but it is equally true that a farmer’s field is more poorly drained. A Parisian caterer has earned 100 sous, I grant you; but grant me in return that a provincial ditch-digger has failed to earn those same five francs. All one can say is that the official feast and the satisfied caterer—that is what is seen; the flooded field and the idle ditch-digger—that is what is not seen.

Good God! It takes so much effort in political economy to prove that two and two make four; and when you succeed, people cry out, “That’s so obvious, it’s boring.”Then they go on to vote as if you had proved nothing at all.

IV. Theatres and the Fine Arts

Should the State subsidize the arts? [30]

There is certainly much to say both for and against. [31]

In favor of the system of subsidies, one might say that the arts enlarge, elevate, and make more poetical the soul of a nation, that they lift it above material [19] concerns, give it a sense of beauty, and thus positively influence its manners, customs, morals, and even its industry. One might ask where music in France would be without the Italian Theatre and the Conservatory of Music, or dramatic art without the Théâtre-Français; painting and sculpture without our collections and museums? [32] One might go further and ask whether, without centralization, and thus the subsidization of the fine arts, that exquisite taste would have developed which is the noble hallmark of French craftsmanship and which distributes its products around the entire world. In view of such results, would it not be highly reckless to give up that modest tax on all citizens which, in the end, secures their superiority and glory in the heart of Europe?

I opposition to these and many other arguments whose strength I do not deny, one can put forward others no less powerful. First of all, one might say, there is a question of distributive justice. Does the legislator have the right to nibble away at the artisan’s wages in order to add a bonus to the artist’s earnings? M. Lamartine said: [33] If you cut the subsidy to a theatre, where will it stop? Will you not logically be led to eliminate your universities, your museums, your Institutes, your libraries? To which one might respond: If you [20] want to subsidize everything that is good and useful, where will you stop? Will you not be logically led to establish a civil list [34] for agriculture, industry, commerce, charity, and education? Moreover, is it certain that subsidies promote artistic progress? That question is far from settled, and we plainly see that the most prosperous theatres are those that live on their own revenues. Finally, ascending to higher considerations, it can be observed that needs and desires give rise to one another and rise to ever refined levels as public wealth allows them to be satisfied; [35] that the government has no business meddling in this progression, since, under current economic conditions, it cannot stimulate luxury industries through taxation without harming essential ones, thus disrupting the natural course of civilization. It may be noted that such artificial displacements [36] of needs, tastes, labor, and population place nations in a precarious and dangerous situation lacking solid foundations.

So here are some of the reasons given by opponents of state intervention in determining the order in which citizens choose to satisfy their needs and desires, and thus [21] direct their activity. I am among those, I admit, who believe that initiative and direction should come from below, not above, from the citizens, not the legislator; and the opposite doctrine seems to me to lead to the destruction of liberty and human dignity.

But through a deduction as false as it is unjust, do you know what people accuse economists of? That when we reject the subsidy, we reject the very thing to be subsidized, and that we are enemies of all forms of activity because we want these activities, on the one hand, to be free, and on the other, to seek their reward from within themselves. Thus, if we ask that the State not intervene in religious matters with subsidies from taxes, we are called atheists. If we ask that the State not intervene in education with subsidies from taxes, we are accused of hating knowledge. If we say that the State should not give an artificialvalue to land or any particular industry with subsidies from taxes, we are branded enemies of property and labor. If we think the State should not subsidize artists, we are called barbarians who deem the arts useless.

I hereby protest with all my strength against such conclusions. Far from entertaining the absurd notion of destroying religion, education, property, labor, and the arts when we ask [22] the State to protect the free development of all these forms of human activity without subsidizing one at the expense of another, we believe, on the contrary, that all these vital forces in society would develop harmoniously [37] under the influence of liberty, that none of them would become, as we see today, sources of conflict, abuse, tyranny, and disorder.

Our opponents believe that an activity not subsidized or regulated is an activity destroyed. We believe the opposite. Their faith lies in the legislator, not in humanity. Ours lies in humanity, not in the legislator.

Thus, M. Lamartine said: In the name of this principle, you must abolish the public exhibitions that are the honor and wealth of this country.

I reply to M. Lamartine: From your point of view, not subsidizing means abolishing, because you assume that nothing exists except through the will of the State, and therefore conclude that nothing lives except what taxation keeps alive. But I turn your own example against you and point out that the greatest and noblest of exhibitions, the one conceived in the most liberal, most universal spirit, and I might even say humanitarian, without exaggeration, is the exhibition now being prepared in London, the only [23] one in which no government is involved and which is subsidized by no tax. [38]

Returning to the fine arts, I repeat: strong reasons can be advanced both for and against the system of state subsidies. The reader will understand that, given the particular aim of this essay, I am not here to expound those reasons or choose between them.

But M. Lamartine has put forward one argument I cannot let pass in silence, because it falls squarely within the scope of this economic study.

He said:

The economic question, when it comes to theatres, boils down to one word: labor. The nature of the labor does not matter, it is just as fruitful, just as productive as any other type of work in the nation. Theatres, as you know, support no fewer than eighty thousand workers of all kinds in France, painters, masons, set designers, costume-makers, architects, etc., who are the very life and movement of several districts of this capital, and on that basis, they deserve your sympathy!

Your sympathy!—which translated means: your subsidies. And further on:

The pleasures of Paris provide work and consumption in the provinces, and the luxuries of the rich provide the wages and the bread of two hundred thousand workers of every kind, who live from the many industries of the theatre across the Republic and receive from these noble pleasures, which [24] glorify France, the sustenance of their lives and the necessities for their families and children. It is to them that you will give these 60,000 francs. (“Very good! Very good!”—many signs of approval.)

As for me, I must say: Very bad! Very bad!—speaking strictly, of course, to the economic argument under discussion.

Yes, it is to the theatre workers that the 60,000 francs in question will go, at least in part. [39] Some scraps may be lost along the way. Indeed, if we looked closely, we might find that the cake takes another route entirely; the workers will be lucky if they get a few crumbs! But let me concede that the entire subsidy goes to the painters, decorators, costume-makers, hairdressers, etc. That is what is seen.

But where does it come from? That is the reverse side of the issue, just as important to examine as the face. Where is the source of those 60,000 francs? And where would they have gone if a legislative vote had not first directed them toward Rue de Rivoli and from there to Rue de Grenelle? [40] That is what is not seen.

Surely no one will claim that the legislative vote conjured this sum into being at the ballot box; that it is a pure addition to the wealth of the nation; that without this miraculous vote, the sixty thousand francs would have remained forever invisible [25] and intangible. It must be admitted that all the majority could do was decide that the money would be taken from somewhere to be sent somewhere else, and that it would have this use only because it was diverted from another.

Given this, it is clear that the taxpayer who is taxed one franc will no longer have that franc at his disposal. Clearly, he will be deprived of some satisfaction equal to one franc, and the worker, whoever he may be, who would have provided it to him will be deprived of wages to the same extent.

Let us therefore not indulge the childish illusion that the vote of May 16 [41] adds anything to national well-being or national labor. It displaces the enjoyments of goods, it displaces wages, that is all.

Will it be said that it replaces one kind of satisfaction and labor with another that is more urgent, more moral, more rational? I could argue on that ground. I could say: By taking 60,000 francs from the taxpayers, you reduce the wages of plowmen, ditch-diggers, carpenters, blacksmiths, and you increase, by that much, the wages of singers, hairdressers, set decorators, and costume-makers. There is no proof that the latter class is more deserving than the former. M. Lamartine does not claim it is. He himself says that theatrical labor is just as fruitful, just as productive (and not more) than any other, which could still be [26] contested, for the best proof that the second is not as fruitful as the first is that the first must be taxed in order to subsidize the second.

But this comparison of the intrinsic value and merit of various kinds of labor is not the subject of my present argument. All I aim to show here is that if M. Lamartine and those who applauded his reasoning saw with their left eye [42] the wages earned by those who supply the needs of actors, they ought also to have seen with their right eye the wages lost by those who supply the needs of the taxpayers; otherwise, they exposed themselves to the ridicule of mistaking a displacement for a gain. If they were consistent in their doctrine, they would call for subsidies without end, for what is true of one franc and of 60,000 francs, is true, in identical circumstances, of a billion francs.

When it comes to taxation, gentlemen, justify it by arguments grounded upon fundamental principles, but not with that unfortunate assertion, that “Public spending sustains the working class.” It hides a crucial fact, namely that public spending always replaces private spending, and thus, while it may well support one worker instead of another, it adds nothing to the welfare of the working class as a whole. Your argument may be fashionable, but it is too absurd not to be defeated by reason.

[27]

V. Public Works [43]

If a nation, after having assured itself that a major undertaking will benefit the community, proceeds to carry it out using the proceeds of a contribution made by the community, nothing could be more natural. But I must confess, my patience runs out when I hear this economic blunder offered in support of such a decision: “Moreover, it is a way to create jobs for workers.”

The State builds a road, erects a palace, straightens a street, digs a canal; in doing so, it gives work to certain laborers—that is what is seen; but it takes work away from certain other laborers—that is what is not seen.

Here is a road under construction. A thousand workers arrive every morning, leave every evening, and take away their wages—this is certain. Had the road not been decreed, had the funds not been voted, these honest people would not have found work or wages there—this too is certain.

But is that all? Does the operation, taken as a whole, involve nothing more? At the moment when M. Dupin pronounces the sacred words, “The Assembly has adopted,” do millions of francs descend miraculously from a moonbeam into the coffers of Messrs. Fould and Bineau? [44] In order for the "development", [28] as they say, to be complete, must not the State organize revenue as well as expenditure? Must it not dispatch its tax collectors into the countryside and get its taxpayers to pay a tax?

So study the question in both of its components. While observing the use the State makes of the millions of francs which have been voted for this purpose, do not neglect to consider the use that the taxpayers would have made, and now can no longer make, to those same millions of francs. Then you will understand that a public enterprise is a two-sided coin. On one side is a worker employed, with this motto: What is seen; on the other, a worker unemployed, with this motto: What is not seen.

The sophism I am attacking in this essay is all the more dangerous when applied to public works, because it serves to justify the wildest schemes and most extravagant spending. When a railway or a bridge has real utility,it is enough to cite that utility. But if that cannot be done, what is invoked? This deception: “We must create jobs for workers.”

That being said, think about the time when the terraces of the Champ-de-Mars [45] were ordered to be built and then torn up again. We know that the great Napoleon believed he was doing philanthropic work by having ditches dug and refilled. He also said: What does the result matter? We must only look at the wealth that is spread among the working classes. [46]

[29]

Let us get to the root of things. Money deceives us. Asking all citizens for their support, in the form of money, for a common project is, in reality, asking them for support in kind, for each citizen obtains, through his labor, the sum he is taxed. Now, if all citizens were gathered together to carry out, by means of a community work detail, [47] a task which is useful to all, this would be understandable;their reward would be in the benefits of the work itself. But if, after summoning them, we forced them to build roads that no one will use, palaces that no one will inhabit, all under the pretext of providing them with employment, this would be absurd, and they would be fully justified in replying: We have no use for that kind of work; we would rather work for our own ends.

The method of making citizens contribute money rather than labor changes nothing about the overall result. Only now, with the latter method, the loss is spread across everyone. Under the first method, those employed by the State escape their share of the loss by adding it to that already borne by their fellow citizens.

There is an article in the Constitution which reads: [48]

“Society favors and encourages the development of labor… by establishing, through the State, the departments, and the communes, public works suited to employing idle hands.”

[30]

As a temporary measure, in a time of crisis, during a harsh winter, this intervention by the taxpayer may have positive effects. It acts in the same way as insurance. It adds nothing to labor or wages, but it takes something from labor and wages in ordinary times in order to provide something, with a loss admittedly, in difficult periods.

As a permanent, general, systematic measure, it is nothing but a ruinous illusion, an impossibility, a contradiction that shows a small amount of labor which has been (artificially) stimulated that is seen, and hides a great deal of labor which has been prevented that is not seen.

VI. Middlemen

Society is the sum total of the services that men necessarily or voluntarily render to one another, [49] that is to say, of public services and private services. [50]

The former, imposed and regulated by law, which is not always easy to change when needed, can outlive their own utility for a long time, along with the law, and still retain the name public services, even when they are no longer services at all, but rather public annoyances. The latter belong to the realm of free will and individual responsibility. [31] Each person gives and receives what he wants, what he can, after mutual discussion. [51] They always enjoy the presumption of genuine usefulness, precisely measured by their relative value.

That is why public services are so often marked by resistance to change, while private services obey the law of progress.

While the excessive growth of public services, through the waste of energy it entails, tends to form a harmful form of parasitism within society, it is somewhat ironic that several modern socialist groups, attributing this character to free and private services, seek to transform these professions into public functions. [52]

These groups rise up with some force against what they call middlemen. They would gladly abolish the capitalist, the banker, the speculator, the entrepreneur, the merchant, and the trader, accusing them of inserting themselves between production and consumption so as to rob both without adding any value. Or rather, they would like to transfer to the State the task these people perform, since the task itself cannot be abolished.

The socialist fallacy on this point lies in showing the public what it pays middlemen in exchange for their services, and hiding what it would have to pay the State. It is always the same battle between what strikes the eye and what can only be seen [32] by the mind, between what is seen and what is not seen.

This was especially the case in 1847, during the time of famine, when the socialist school worked hard, and successfully, to popularize their ruinous theory. They knew very well that even the most absurd propaganda has a good chance with those who suffer; malesuada fames (ill-counseling famine). [53]

So, with grand phrases like the exploitation of man by man, speculation in hunger, hoarding, they set about vilifying commerce and casting a veil over its benefits.

“Why,” they asked, “should we allow merchants to bring food from the United States and the Crimea? [54] Why don’t the State, the departments, and the municipalities organize the supply of food and its storage in warehouses? They would sell at cost, and the people, the poor people, would be freed from the tribute they pay to free commerce, that is to say, egoistic, individualistic, anarchic commerce.”

The tribute the people pay to commerce—that is what is seen. The tribute the people would pay to the State or its agents under the socialist system—that is what is not seen.

What is this so-called tribute the people pay to commerce? It is this: that two men render one another reciprocal services, in complete freedom, [33] under the pressure of competition, and at a negotiated price.

When the hungry stomach is in Paris and the wheat that can satisfy it is in Odessa, the suffering will not end until the wheat is brought closer to the stomach. There are three ways this can happen: 1) The hungry men can go to look for wheat themselves; 2) they can entrust the task to those who make it their business; 3) they can pool their funds and assign the operation to public officials.

Of these three methods, which is the most advantageous?

At all times, in all countries, and the more so the freer, more enlightened, more experienced the people are, they have voluntarily chosen the second. That, to me, is enough to presume in its favor. My mind refuses to believe that all of humanity has been mistaken on a question so vital to its wellbeing.

Let us examine this nonetheless.

For thirty-six million citizens to set off for Odessa to look for the wheat they need is obviously impractical. The first option is worthless. Consumers cannot act for themselves; they are forced to rely on middlemen, whether they be government officials or merchants.

Let us note, however, that the first option would be the most natural. After all, it is up to the hungry man to go to find his wheat. It is a burden that concerns him; it is a service he owes himself. [34] If someone else, on any grounds, performs this service and bears this burden on his behalf, that person has the right to compensation. I make this point only to show that the services of middlemen inherently call for remuneration.

Be that as it may, since we must rely on what socialists call a parasite, which is the less demanding parasite: the trader or the government official?

Commerce (I assume it is free, for otherwise how I can I use reason to discuss the matter?) is driven, by self-interest, to study the seasons, to monitor the state of the harvests daily, to gather information from every corner of the globe, to anticipate the people's needs, to take precautions in advance. It has ships at the ready, correspondents everywhere, and its immediate interest is to buy at the lowest price, to economize in every detail of the operation, and to achieve the greatest results with the least effort. It is not only French merchants, but traders all over the world who concern themselves with supplying France in times of need; and if self-interest compels them to fulfill their task at the lowest possible cost, competition among them no less inevitably compels them to pass all those savings along to the consumer. Once the wheat arrives, the merchant has an interest in [35] selling it quickly, to minimize his risks, recover his capital, and, if necessary, begin again. Guided by the comparison of prices, he distributes the food across the whole country, always beginning with the highest prices, that is, where the need is most urgent. It is therefore impossible to imagine an organization better designed in the interest of those who are hungry, and the brilliance of this organization, unnoticed by the socialists, stems precisely from its being free. It is true, the consumer must reimburse the merchant for transportation, handling, storage, commission, etc.; but in what system is the person who eats the wheat not required to pay the cost of making it accessible? In addition, there is a payment due for the service rendered; but as for the amount, it is reduced to the lowest possible level by competition; and as for its justice, it would be strange if Parisian artisans did not work for Marseille merchants, when Marseille merchants work for Parisian artisans.

Now, suppose the State replaces commerce according to the socialist idea. What will happen? I ask, where will the savings be for the public? Will they come from the purchase price? Imagine the delegates of forty thousand communes arriving in Odessa at once, at the moment of need, imagine [36] the effect on prices. Will they come from reduced costs? Will fewer ships, fewer sailors, fewer transfers, fewer warehouses be needed? Will we somehow be spared paying for these things? Will savings come from eliminating the profit of the merchant? But will your delegates and government officials go to Odessa for nothing? Will they travel and work on the principle of brotherhood? Will they not need to live? Will their time not need to be paid for? And do you really believe that will not far exceed the two or three percent the merchant earns, the very margin he is willing to accept?

And then, consider the difficulty of levying so many taxes, of distributing so much food. Consider the injustices, the abuses inseparable from such an enterprise. Consider the weight of responsibility that would fall upon the government.

The socialists who invent these absurdities, and who, in times of hardship, whisper them into the ears of the masses, generously bestow upon themselves the title of advanced thinkers, and it is not without danger that common usage, that tyrant of language, ratifies the term and the judgment it implies. Advanced! —this presumes that these gentlemen see farther than the common people; that their only fault is being too far ahead of their time; and that if the moment has not yet come to abolish certain free services, these so-called parasites, then [37] it is the fault of the public, which lags behind socialism. In my soul and conscience, the opposite is true, and I do not know to what barbaric century we would have to return to find on this matter the same level of misunderstanding as that of the socialists..

The modern socialist groups constantly contrast their idea ofassociation with present day society. [55] They fail to see that society, under a regime of liberty, is a genuine association, far superior to all those that spring from their fertile imagination.

Let us clarify this with an example:

For a man to be able, upon waking, to put on a coat, a piece of land must have been enclosed, cleared, drained, tilled, and sown with certain plants; herds must have fed on them and yielded their wool; the wool must have been spun, woven, dyed, and made into cloth; and that cloth must then have been cut, sewn, and fashioned into a garment. This series of operations implies countless others, for it assumes the use of plows, barns, factories, coal, machines, vehicles, etc.

If society were not a very real association, the man who wants a coat would be forced to work in isolation, that is, to perform for himself all the acts in that series, from the first blow of the pickaxe to the final stitch of the needle.

[38]

But thanks to sociability, [56] the defining trait of our species, these operations have been distributed among countless workers, and they become increasingly subdivided, for the common good, [57] as consumption grows and each specific act can sustain a new industry. Then comes the division of the product, which is made according to the value each person has contributed to the whole. If this is not association, then I ask: what is?

Note that none of the workers has created even the smallest particle of matter out of nothing; they have only rendered reciprocal services, assisting one another toward a common goal, and each of them may be considered, relative to the others, as a middleman. If, for instance, in the course of this process, transport becomes sufficient to occupy one person, spinning another, weaving a third, why should the first be called more of a parasite than the other two? Must not the transport be done? Does not the transporter dedicate time and effort to it? Does he not save the people he is associated with [58] that same time and effort? Do the others do anything more or differently for him? Are they not all equally subject, for their remuneration, that is, for their share of the product, to the law of the negotiated price? Is it not in full liberty, and for the common good, that this division [39] of labor takes place, and that these arrangements are made? Why, then, do we need a socialist, under the pretext of organization by the government, to come and tyrannically dismantle our voluntary arrangements, halt the division of labor, replace cooperative efforts with isolated ones, and drive civilization backward? Is the association I describe here any less an association because each person enters and exits freely, chooses his place, judges and bargains for himself, under his own responsibility, and brings to it the driving force [59] and the guarantee of personal interest? Must a so-called reformer impose his own formula and will, concentrating, as it were, all of humanity in himself, for this to be called “association”?

The more one examines these advanced schools of thought, the more one is convinced that there is only one thing beneath it all: ignorance proclaiming itself to be infallible, and demanding despotism in the name of that infallibility.

Let the reader forgive this digression. It may not be useless at a moment when, having escaped from the books of the Saint-Simonians, the Phalansterians, and the Icarians, [60] the outcry against middlemen is invading the press and the podium, and seriously threatening the freedom of working [61] and of exchange.

[40]

VII. Trade Restrictions [62]

Mr. Prohibant (that’s not a name I invented, it comes from M. Charles Dupin, who since then... but let’s leave that aside), [63] Mr. Prohibant devoted his time and capital to turning the ore on his land into iron. But since nature had been more generous to the Belgians, they supplied iron to the French at a better price than Mr. Prohibant could, which meant that all French people, or France as a whole, could obtain a given quantity of iron with less labor by buying it from the honest Flemings. Naturally, guided by their self-interest, they did just that, and every day one saw crowds of nail-makers, blacksmiths, wheelwrights, mechanics, farriers, and farmers go, either in person or through intermediaries, to make their purchases in Belgium. This greatly displeased Mr. Prohibant.

At first, he thought of putting a stop to this abuse by his own means. That was only fair, since he alone was suffering from it.

“I’ll take my rifle,” he said, “strap four pistols to my belt, fill my cartridge box, gird my broadsword, and head for the frontier. There, the first blacksmith, nail-maker, farrier, mechanic, or locksmith who shows up to serve his own interests and not mine, I’ll kill him, just to teach him a lesson.”

But just as he was about to set off, Mr. Prohibant had [41] a few thoughts that slightly cooled his warlike ardor. He thought to himself: First, it’s not entirely impossible that my fellow countrymen, the buyers of iron, might take offense, and instead of letting themselves be killed, they might kill me. Secondly, even if I mobilized all my servants, we still couldn’t guard every crossing point. Finally, this method would be very expensive, more than the result is worth.

Mr. Prohibant was sadly resigning himself to being as free as everyone else, when a flash of inspiration illuminated his mind.

He remembered that there is, in Paris, a great law factory. [64]

“What is a law?” he asked himself. “It’s a measure which, once decreed, whether good or bad, everyone must obey. To enforce it, a public force is organized, and to form that public force, men and money are drawn from the nation.”

“So if I could get the great Parisian factory to issue just a little law saying: ‘Belgian iron is prohibited,’ I would achieve the following results: The government would replace the handful of servants I had planned to post at the frontier with twenty thousand sons of those very same blacksmiths, locksmiths, nail-makers, farriers, artisans, mechanics, and farmers who had defied me. Then, to keep these twenty thousand customs agents [65] happy and healthy, it would distribute twenty-five million francs to them, taken from those very same blacksmiths, nail-makers, artisans, and farmers. The guards would do a better job; it would cost me nothing; I wouldn’t risk being beaten by the dealers; I could sell my iron at my price, and I’d enjoy the sweet pleasure of seeing our great nation shamelessly fooled. That would teach it not to boast constantly of being the pioneer and promoter of all progress in Europe. Oh! the joke would be priceless, it’s worth a try.”

So Mr. Prohibant went to the law factory. Another time perhaps I will recount the story of his backroom dealings; today I want only to describe his public efforts.He presented the lawmakers with the following argument:

“Belgian iron is sold in France for ten francs, which forces me to sell mine at the same price. I would prefer to sell at fifteen, but I cannot because of this God-damned Belgian iron. [66] Please pass a law that says: ‘Belgian iron shall no longer enter France.’ Immediately, I’ll raise my price by five francs, and here are the consequences:

For every hundredweight of iron I sell to the public, instead of receiving ten francs, I will receive fifteen. I will get rich faster; I will expand my operation; I will employ more workers. My workers and I will spend more, to the great benefit of our suppliers within many [43] miles of us. With increased demand, those suppliers will place more orders with industry, and step by step, the activity will spread across the entire country. That blessed coin you will drop into my coffer, like a stone thrown into a lake, will ripple outward in infinite concentric circles.” [67]

Charmed by this speech, delighted to learn that the wealth of a nation can be increased by legislative fiat, the law-makers voted for the trade restriction. “Why bother with labor and frugality?” they asked. “Why struggle to increase national wealth when a decree will do?”

And indeed, the law had all the consequences Mr. Prohibant had predicted; only, it had others as well, for let’s be fair, his reasoning was not false, but it was incomplete. In demanding a legal privilege, he pointed out the effects that are seen, leaving in the shadows those that are not seen. He showed only two characters, when there are three in the scene. It is up to us to correct this omission, whether accidental or deliberate.

Yes, the écu [68] diverted by law into Mr. Prohibant’s coffer represents a gain for him and for those whose labor he encourages. And if the decree had caused that écu to fall from the moon, those good effects would not be offset [44] by any compensating bad ones. Unfortunately, the écu does not fall from the moon, it comes out of the pocket of a blacksmith, nail-maker, wheelwright, farrier, farmer, builder, in short, from Jacques Bonhomme, who now hands it over without receiving one milligram more of iron than when he paid only ten francs. At first glance, it’s clear this changes the entire question, because quite evidently, Mr. Prohibant’s profit is offset by Jacques Bonhomme’s loss, and whatever Mr. Prohibant might do with that écu to encourage national labor, Jacques Bonhomme would have done the same. The stone is thrown into one part of the lake only because the law has forbidden it from being thrown into another.

So, what is not seen counterbalances what is seen, and the net result of the operation is an injustice, and, deplorably, an injustice perpetrated by the law.

But that’s not all. I said that a third character was left in the shadows. Let me now bring him forward to reveal a second loss of five francs. Then we will have the full result of the entire process.

Jacques Bonhomme possesses fifteen francs, earned by the sweat of his brow. Let us return to the time when he is still free. What does he do with those fifteen francs? He buys a [45] fashionable item for ten francs, and with that item he pays (or the intermediary pays on his behalf) for a hundredweight of Belgian iron. Jacques Bonhomme still has five francs left. He doesn’t throw them into the river, [69] but (and this is what is not seen) he gives them to some other tradesman in exchange for the enjoyment of some good, say, to a bookseller for Bossuet’s Discourse on Universal History. [70]

So, in terms of national labor, it is encouraged to the tune of fifteen francs, namely:

- 10 francs to those who manufacture the luxury goods of Paris [71] ;

- 5 francs to the bookseller.

And as for Jacques Bonhomme, for his fifteen francs he receives two satisfactions:

- A hundredweight of iron;

- A book.

Then the decree arrives.

What becomes of Jacques Bonhomme’s situation? And what becomes of national labor?

Jacques Bonhomme now hands over all fifteen francs to Mr. Prohibant for a hundredweight of iron, he now enjoys only that iron. He loses the enjoyment of the book or any other equivalent good. He loses five francs. This is admitted, it must be admitted, it cannot be denied that when trade restrictions raise the price of goods, the consumer loses the difference.

[46]

“But,” people say, “national labor gains it.”

No, it does not gain it; because since the decree, national labor is encouraged to exactly the same extent as before: fifteen francs.

Only, since the decree, Jacques Bonhomme’s fifteen francs go to metallurgy industry, whereas before they were divided between Parisian luxury goods and publishing.

The violence Mr. Prohibant uses personally at the frontier, or has carried out there through the law, may be judged differently from a moral point of view. There are people who believe that plunder loses all its immorality when it is legal. As for me, I can imagine no circumstance which is worse. Be that as it may, what is certain is that the economic results are identical.

Twist the matter however you wish, but if you use a sharp eye [72] you will see that nothing good comes from legal or illegal plunder.We do not deny that a profit of five francs results for Mr. Prohibant or his industry, or, if you like, for national labor. But we claim that two losses result as well: one for Jacques Bonhomme, who now pays fifteen francs for what he formerly paid ten; and one for national labor, which no longer receives the remaining difference. Choose whichever of the two losses you wish to balance out the gain we acknowledge. The other [47] will still remain a net loss.

Moral: To use force is not to produce, it is to destroy. Oh! if using force meant producing things, France would be wealthier than it is.

VIII. Machines

“Curse the machines! Every year their growing power condemns millions of workers to poverty by taking away their work, along with their work their wages, and along with their wages their bread! Curse the machines!” [73]

Such is the cry that arises out of popular prejudice, echoed in the newspapers.

But to curse machines is to curse the human mind!

What amazes me is that anyone could feel at ease with such a doctrine.

For after all, if it were true, what would be its logical consequence? It would be that activity, well-being, wealth, and happiness are possible only for stupid people, stricken with mental stagnation, to whom God has not given the fatal gift [48] of thinking, observing, experimenting, inventing, of achieving greater results with fewer means. On the contrary, rags, squalid huts, poverty, and starvation must be the inevitable lot of every nation that seeks and finds in iron, fire, wind, electricity, magnetism, and the laws of chemistry and mechanics, in short, in the forces of nature, supplements to its own labor. And then it truly would be as Rousseau said: “Every man who thinks is a depraved creature.” [74]

And that’s not all: if this doctrine is true, since all men think and invent, since all of them in fact, from the first to the last, and at every moment of their lives, seek to enlist natural forces, to do more with less, to reduce either their own labor or the labor they pay for, to obtain the greatest possible satisfaction with the least possible effort, then we must conclude that all of humanity is driven toward its ruin precisely by the intelligent aspiration to improve itself that animates each of its members.

In that case, statistics ought to show that the inhabitants of Lancashire, fleeing that homeland of machines, go to seek work in Ireland, where machines are unknown; and history ought to show that [49] barbarism descends upon civilized times, and that civilization shines in eras of ignorance and savagery.

Clearly, there is something in this heap of contradictions that shocks the mind and alerts us to the presence of an unresolved element in the problem.

Here lies the whole mystery: behind what is seen lies what is not seen. I will try to bring it to light. My demonstration will be only a repetition of the previous ones, because this is an identical problem.

Men have a natural tendency to seek out, if they are not prevented by violence, lower prices [75], that is, to pursue what, for an equal satisfaction, saves them labor, whether that lower price comes from a skillful foreign producer or a skillful mechanical producer.

The theoretical objection raised against this tendency is the same in both cases. In both, it is criticized for the labor it seemingly renders inactive. But labor is not made inactive but made available for other uses, this is precisely what it achieves.

And this is why, in both cases, it is met with the same practical obstacle: violence. The legislator prohibits foreign competition and forbids mechanical competition.For what other [50] means exists to restrain a natural tendency in all men, except by taking away their freedom?

In many countries, it is true, the legislator attacks only one of these two forms of competition and merely moans about the other. This proves only one thing: that in those countries, the legislator is inconsistent.

We should not be surprised. With any false path, one is always inconsistent, otherwise, one would destroy humanity. No false principle has ever been or will ever be carried out to its conclusion. I have said elsewhere: inconsistency is the limit of absurdity. I might have added: it is also its proof.

Let us now come to our demonstration; it will not be long.

Jacques Bonhomme had two francs that he paid to two workers.

Then he comes up with a system of pulleys and weights that cuts the labor time in half.

So, he obtains the same result, saves one franc, and lays off one worker.

He lays off one worker—that is what is seen.

And seeing only this, people say:

“See how poverty follows civilization! See how liberty is fatal to equality! The human mind has made a conquest, and instantly, a worker has fallen forever into the abyss of poverty. It may [51] even be that Jacques Bonhomme keeps employing both workers, but now he will pay them only ten sous each, because they will compete with one another and underbid each other. That is how the rich get richer and the poor poorer. Society must be changed.”

A noble conclusion, and well-matched to the premise!

Fortunately, both the premise and the conclusion is false, because behind one half of the phenomenon that which is seen, there lies the other half that which is not seen.

What is not seen is the franc saved by Jacques Bonhomme and the necessary effects of that saving.

Since, thanks to his invention, Jacques Bonhomme now spends only one franc on labor to attain a certain satisfaction, he has one franc left over.

So, if there is in the world a worker offering his unused labor, there is also in the world a capitalist offering his unused franc. These two elements meet and combine.

And it is as clear as day that the relationship between the supply and demand for labor, between the supply and demand for wages, is not altered in the slightest.

The invention and the worker paid with the first franc now accomplish what previously required two workers.

[52]

The second worker, paid with the second franc, produces something new.

So what has changed in the world? There is now one more national satisfaction, in other words, the invention is a free gain, a free profit for humanity.

From the way in which I have presented this demonstration, one might draw the following objection:

“It’s the capitalist who reaps all the benefit of the machines. The wage-earning class, though it may suffer only temporarily, never profits, since, according to you, machines displaces a portion of national labor without reducing it, yes, but also without increasing it.”

It is not within the scope of this pamphlet to resolve all objections. Its sole aim is to combat a popular, dangerous, and widespread prejudice. I wished to prove that a new machine only frees up a certain number of laborers by also and necessarily freeing up the wages that were paid to them. These laborers and this capital combine to produce what could not be produced before the invention; hence it follows that its final result is an increase in satisfactions for the same amount of labor.

Who reaps this surplus of satisfactions?

Yes, it is initially the capitalist, the inventor, the first person to successfully use the machine, and [53] that is the reward for his genius and boldness. In this case, as we have just seen, he realizes a saving on the cost of production, which, however he spends it (and it is always spent), employs exactly as much labor as the machine put out of work.

But soon competition forces him to lower his selling price in proportion to that saving.

Then it is no longer the inventor who gains from the invention; it is the buyer of the product, the consumer, the public, including workers, in a word, it is all of humanity.

And what is not seen is that the savings thereby afforded to all consumers form a fund from which wages draw nourishment to replace what the machine had dried up.

Returning to our example: Jacques Bonhomme used to obtain a product by spending two francs in wages.

Thanks to his invention, labor now costs him only one franc.

As long as he continues selling the product at the same price, there is one fewer worker employed in producing that particular item, that is what is seen; but there is one more worker employed by the franc Jacques Bonhomme has saved, that is what is not seen.

When, through the natural course of events, Jacques Bonhomme is forced to reduce the price of the product [54] by one franc, then he no longer realizes a saving; he no longer has a franc to direct toward new national production. But in this case, the buyer takes his place, and that buyer is humanity. Whoever purchases the product pays one franc less, saves a franc, and necessarily puts that saving to use in the wage fund, that, too, is what is not seen.

Another explanation of the machine problem has been offered, based on facts.

It goes like this: the machine lowers the cost of production and thus the product’s price. The lower price increases consumption, which in turn requires more production, and ultimately brings about the employment of as many, or more, workers after the invention than before. The proof given includes examples from printing, spinning, journalism, etc.

This argument is not scientific.

It would lead us to conclude that if consumption of a given product remains steady or nearly so, the machine harms labor. Which is not true.

Suppose that in a country all men wear hats. If a machine manages to reduce their price by half, it does not follow necessarily that people will consume twice as many hats.

Will we say, in that case, that part of the national labor [55] has been made idle? Yes, according to the popular argument. No, according to mine; because even if not a single extra hat is purchased in that country, the entire wage fund remains intact. What is spent less on the hat industry reappears in the savings realized by all consumers, and from there, it pays for all the labor the machine made unnecessary, and generates a new development in every other industry.

And that is how things work in practice. I’ve seen newspapers cost 80 francs, they now cost 48. That’s a 32 franc saving for subscribers. It is not certain, at least not necessary, that the 32 francs will continue to benefit the journalism industry. But what is certain, what is necessary, is that if they do not go there, they go elsewhere. One person uses them to get more newspapers, another to eat better, a third to dress better, a fourth to better furnish his home.

Thus, all industries are interconnected. They form a vast whole in which every part communicates with the rest through hidden channels. [76] What is saved in one benefits all. [77] The essential point is to understand that never—never—do savings come at the expense of labor and wages.

[56]

IX. Credit

At all times, but especially in recent years, there has been talk of making wealth available to all by making credit available to all. [78]

I do not think I exaggerate in saying that, since the February Revolution, the Parisian presses have spewed out more than ten thousand pamphlets promoting this solution to the Social Problem.

This solution, alas, is based on a pure optical illusion, if an illusion can be called a basis at all.

It begins by confusing cash with products, and then paper money with cash, and it is from these two confusions that people claim to extract a real thing from nothing. [79]

In this matter, one must absolutely forget about money, currency, banknotes, and other instruments by which products change hands, and look only at the products themselves, which are the true substance of a loan.

For when a farmer borrows fifty francs to buy a plow, it is not really fifty francs that are being lent to him, it is the plow.

And when a merchant borrows twenty thousand [57] francs to purchase a house, it is not twenty thousand francs he owes, it is the house.

Money appears here only to facilitate arrangements between several parties.

Peter may not be willing to lend his plow, while James is willing to lend his money. What does William do? He borrows James’s money and, with it, buys Peter’s plow.

But in reality, no one borrows money for the sake of money itself. Money is borrowed to obtain products.

Now, in no country can more products pass from one hand to another than actually exist.

No matter how much money and paper circulate, the sum total of borrowers cannot receive more plows, houses, tools, or supplies of raw materials than the sum total of lenders can furnish.

Let us engrave this truth on our minds: every borrower presupposes a lender, and every thing borrowed implies a loan.

That being the case, what good can credit institutions do? They can help borrowers and lenders find and reach an agreement with one another. But what they cannot do is suddenly increase the quantity of things that are borrowed and lent.

Yet this would be necessary in order for the [58] reformers’ goal to be achieved, since they aspire to nothing less than placing plows, houses, tools, supplies, and raw materials into the hands of everyone who desires them.

And how do they propose to do this?

By having the State guarantee loans.

Let us dig into the matter, for here there is something that is seen and something that is not seen. Let us try to see both.

Suppose there is only one plow in the world, and two farmers want it.

Peter owns the only plow available in France. John and James want to borrow it. John, by his honesty, by the property he owns, his good reputation, offers guarantees. People trust him; he has credit. James inspires little or no confidence. Naturally, Peter ends up lending his plow to John.

But then, under the influence of the socialists, the State intervenes and says to Peter: Lend your plow to James, I guarantee repayment, and my guarantee is better than John’s, because he has only himself to answer for, while I, it’s true, own nothing, but I have at my disposal the wealth of all the taxpayers. With their money, I will repay you the principal and interest if need be.

Consequently, Peter lends his plow to James—that is what is seen.

[59]

And the socialists rub their hands, saying: Look how well our plan works! Thanks to State intervention, poor James has a plow. He will no longer have to dig the earth by hand; now he’s on the road to prosperity. It’s a benefit for him and a profit for the nation as a whole.

Ah no, gentlemen, it is not a profit for the nation, because here is what is not seen.

What is not seen is that the plow went to James only because it did not go to John.

What is not seen is that if James plows instead of digging, John must now dig instead of plowing.

So what was considered an increase in loans is only a displacement of loans.

Moreover, what is not seen is that this displacement involves two profound injustices.

Injustice toward John, who, after having earned and secured credit through his honesty and industry, finds himself stripped of it.

Injustice toward the taxpayers, who are now exposed to paying a debt that does not concern them.

Will it be said that the government offers John the same facilities as James? But since there is only one plow available, two cannot be lent. The argument always comes down to this: thanks to State intervention, there will be more borrowing than lending, even though the plow [60] represents the total amount of available capital.

I have simplified the operation down to its most basic form; but if you put the most complex government credit institutions to the same test, you will be convinced that they can have no other result than this: to displace credit, not to increase it. In a given country, at a given time, there is only a certain amount of available capital, and all of it is already in use. By guaranteeing the insolvent person, the State may well increase the number of borrowers, thus raising the interest rate (always to the detriment of the taxpayer), but what it cannot do is increase the number of lenders or the total volume of loans.

Let no one attribute to me, however, a conclusion from which God preserve me. I say that the law must not artificially promote borrowing; but I do not say that it must artificially hinder it. If there are obstacles to the spread and application of credit in our mortgage system or elsewhere, then let those obstacles be removed, nothing could be better or more just. But that is, along with liberty, all that true reformers, those worthy of the name, should ask of the law.

[61]

X. Algeria [80]

Now here are four speakers vying for the podium. First they all speak at once, then one after the other. What do they say? Certainly many fine things, on the power and greatness of France, on the necessity of sowing in order to reap, on the bright future of our gigantic colony, on the benefits of pouring the surplus of our population abroad, etc., etc. [81], magnificent pieces of eloquence, always ending with the same peroration:

“Vote fifty million francs (more or less) to build ports and roads in Algeria; to transport colonists there, build them houses, and clear fields for them. In this way, you will have provided relief French laborers, encouraged African labor, and enriched commerce in Marseilles. It’s all profit.” [82]

Yes, that is true, if one considers those fifty million francs only from the moment the State spends them, if one looks only at where they go, not where they come from, if one accounts only for the good they do once they leave the tax collector’s coffer, and not for the harm caused, or the good prevented, in collecting them. Yes, from that narrow point of view, all is gain. The house [62] built in Barbary, that’s what is seen; the port dug in Barbary, that’s what is seen; the work stimulated in Barbary, that’s what is seen; fewer workers in France, that’s what is seen; a great movement of goods through Marseilles, still what is seen.

But there is something else that is not seen. It is that the fifty millionfrancs spent by the State can no longer be spent as they would have been, by the taxpayer. From all the good attributed to the public expenditure undertaken, one must subtract all the harm from the private expenditure which is prevented, unless one goes so far as to say that Jacques Bonhomme would have done nothing with the hard-earned 100 sous coins the tax has taken from him. A ridiculous claim, for if he took the trouble to earn them, it was surely with the hope of deriving satisfaction from their use. He would have repaired the fence around his garden, and now he cannot, that is what is not seen. He would have spread marl on his field [83] and now cannot—that is what is not seen. He would have added a second story to his cottage and now cannot, that is what is not seen. He would have improved his tools and now cannot, that is what is not seen. He would have fed himself better, clothed himself better, better educated his sons, added to his daughter’s dowry, and now cannot, that is what is not seen. He would have joined a mutual aid society [84] and now cannot, [63] that is what is not seen. On one side, there is the enjoyment of goods which are taken away from him, and the productive power which has been removed from his hands; on the other, there is the labor of the ditch-digger, the carpenter, the blacksmith, the tailor, the schoolmaster in his village that he would have supported and which is now destroyed, this is still what is not seen.