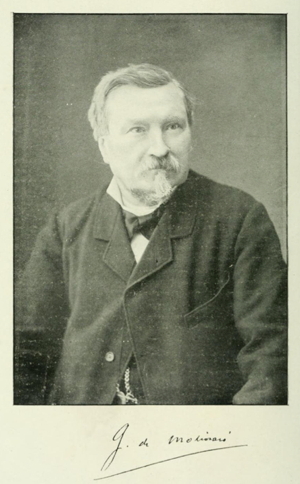

GUSTAVE DE MOLINARI,

The Collected Articles from the Dictionnaire de l'Économie politique (1852-53)

Edited and translated into English by David M. Hart

|

i |

[Created: 12 March, 2025]

[Updated: 12 March, 2025] |

The Guillaumin Collection

|

This title is part of “The Guillaumin Collection” within “The Digital Library of Liberty and Power”. It has been more richly coded and has some features which other titles in the library do not have, such as the original page numbers, formatting which makes it look as much like the original text as possible, and a citation tool which makes it possible for scholars to link to an individual paragraph which is of interest to them. These titles are also available in a variety of eBook formats for reading on portable devices. |

Source

, The Collected Articles from the Dictionnaire de l'Économie politique (1852-53). Edited and translated into English by David M. Hart (March, 2025 draft).http://davidmhart.com/liberty/FrenchClassicalLiberals/Molinari/DEP/Anthology-English/index.html

Gustave de Molinari, The Collected Articles from the Dictionnaire de l'Économie politique (1852-53). Edited and translated into English by David M. Hart (March, 2025 draft).

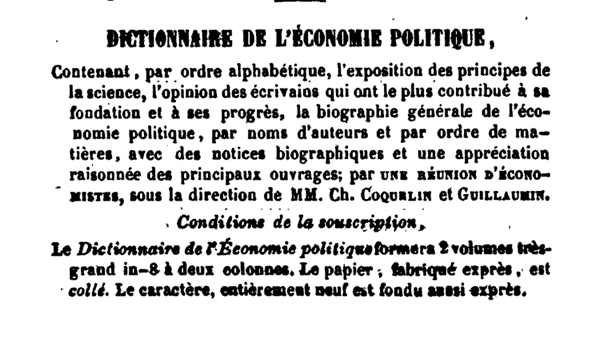

The articles were taken from the Dictionnaire de l’Économie Politique, contenant l’exposition des principes de la science, l’opinion des écrivains qui ont le plus contribué à sa fondation et à ses progrès, la Bibliographie générale de l’économie politique par noms d’auteurs et par ordre de matières, avec des notices biographiques et une appréciation raisonnée des principaux ouvrages, publié sur la direction de MM. Charles Coquelin et Guillaumin. Troisième Édition (Paris: Librairie de Guillaumin et Cie, 1864), 2 vols.

Editions:

- 1st ed. 1852-53

- 2nd ed. 1854

- 3rd ed. 1864

- 4th ed. 1873

This title is also available in a facsimile PDF of the original and various eBook formats - HTML, PDF, and ePub.

This book is part of a collection of works by Gustave de Molinari (1819-1912).

Editor's Note

A French version of this anthology was first put online on 11 June, 2019 as part of my celebrations of the 200th anniversary of Molinari's birth. It was updated in December 2023.

Gustave de Molinari, The Collected Articles from the Dictionnaire de l'Économie politique (1852-53). Edited by David M. Hart (The Pittwater Free Press, 2023). [Online]

Here at long last is a draft of an English translation. Please note that:

- the actual translation is in reasonable shape.

- 7 of the pieces originally appeared in translation in Lalor's Cyclopedia (1881, 1899) which I have revised. I have updated the translation and resored sections which were removed

- the other items are new translations

- all of Molinari's notes are included but I have not added my own notes to all of the texts, such as cross-references to Molinari's other writings, especially the other entries in tne DEP

- nor have I finished adding notes by "the translator" concerning the particular terms used by Molinari (such as on class and plunder) and how and why these were translated the way they have been

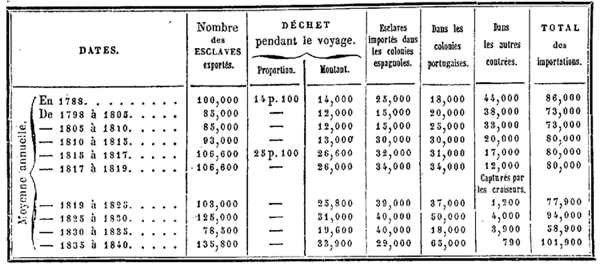

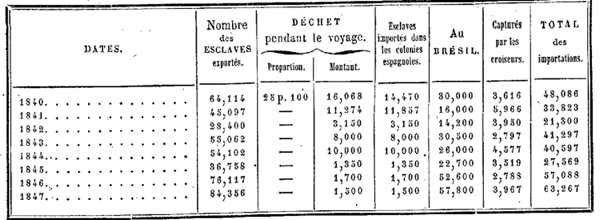

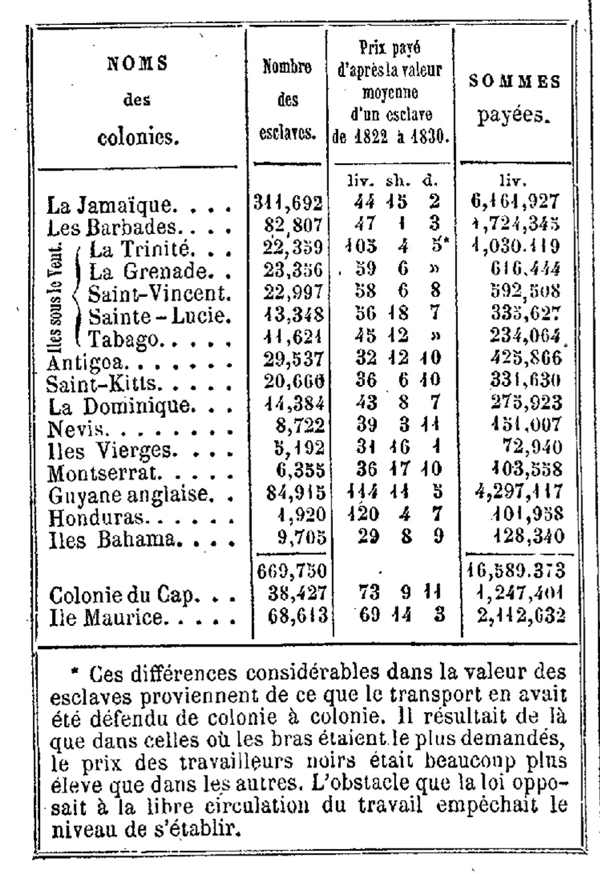

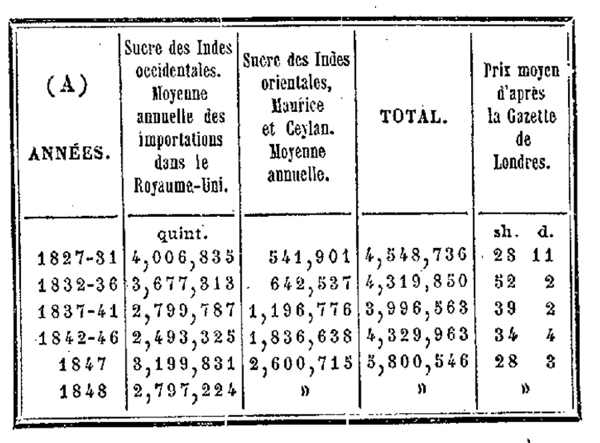

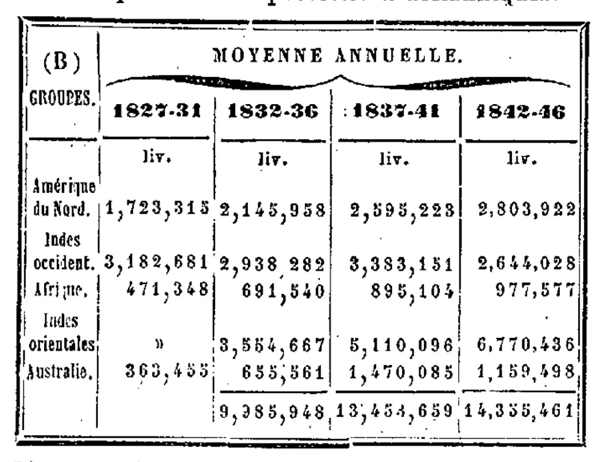

- most tables of data have been converted to HTML tables; there are still some larger ones to do, as in the entry on "Slavery"

- I plan to add an "Editor's Introduction" where I will discuss the significance of the DEP project, the key participants in the project (Guillaumin, Coquelin, Clément), and Molinari's role in it

- I have also included three addtional pieces which I think are of interest: the Preface to the DEP by the publisher Guillaumin, an Introduction by the senior editor Ambroise Clément who replaced the original editor Charles Coquelin who died of a heart attack before work began on the second volume; and Molinari's article published in the Journal des Économistes wich provides some intersting historical and political context to the DEP project.

Table of Contents

- The Editor's Introduction (to come)

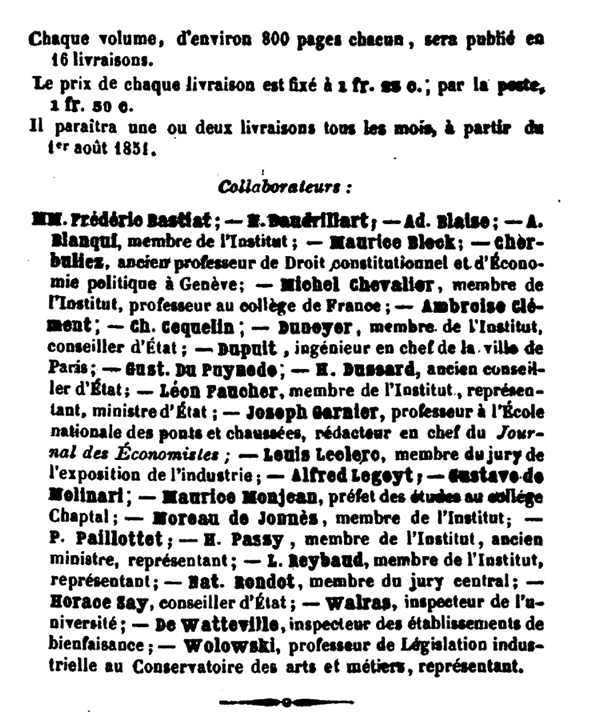

- Announcement of the Publication of the DEP

- Introductory Articles

- Biographical Articles (5)

- Comte (Charles), T. 1, pp. 446-47.

- Necker, T. 2, pp. 272-74.

- Peel (Robert), T. 2, pp. 351-54.

- Saint-Pierre (abbé de), T. 2, pp. 565-66.

- Sully (duc de), T. 2, pp. 684-85.

- Comte (Charles), T. 1, pp. 446-47.

- Principal Articles by Molinari (25)

- Beaux-arts (Fine Arts), T. 1, pp. 149-57.

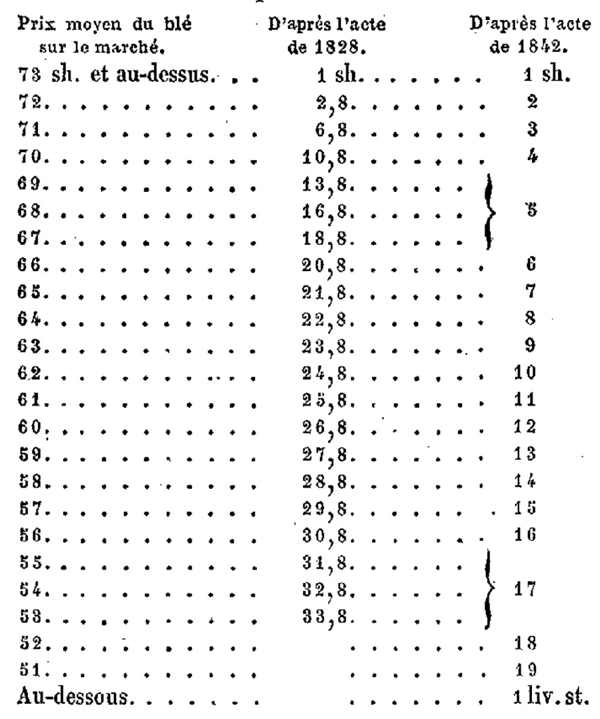

- Céréales (Cereals), T. 1, pp. 301-26.

- Civilisation, T. 1, pp. 370-77.

- Colonies, T. 1, pp. 393-403.

- Colonies agricoles (Agricultural Colonies), T. 1, pp. 403-5.

- Colonies militaires (Military Colonies), T. 1, p. 405.

- Émigration (Emigration), T. 1, pp. 675-83.

- Esclavage (Slavery), T. 1, pp. 712-31.

- Liberté des échanges (Associations pour la) (Free Trade Associations), T. 2, p. 45-49.

- Liberté du commerce, liberté des échanges (Liberty of Commerce, Free Trade), T. 2, pp. 49-63.

- Mode (Fashion), T. 2, pp. 193-96.

- Monuments publics (Public Buildings/Monuments), T. 2, pp. 237-8.

- Nations, T. 2, pp. 259-62.

- Noblesse (Nobility), T. 2, pp. 275-81

- Paix, Guerre (Peace and War), T. 2, pp. 307-14.

- Paix (Société et Congrès de la Paix) (Peace Society and Peacec Congress), T. 2, pp. 314-15.

- Propriété littéraire et artistique (Literary and Artistic Property), T. 2, pp. 473-78

- Servage (Serfdom), T. 2, pp. 610-13

- Tarifs de douane (Customs Tariffs, T. 2, pp. 712-16.

- Théâtres (Theatres), T. 2, pp. 731-33.

- Travail (Work or Labour), T. 2, pp. 761-64.

- Union douanière (Customs Union), T. 2, p. 788-89.

- Usure (Usury), T. 2, pp. 790-95.

- Villes (Cities and Towns), T. 2, pp. 833-38.

- Voyages (Travel), T. 2, pp. 858-60.

- Beaux-arts (Fine Arts), T. 1, pp. 149-57.

The Editor's Introduction (to come)

[A new Editor's Introduction is planned. This is the Introduction which appeared with the French version of the anthology in June 2019.]

The DEP is a two volume, 1,854 page, double-columned, nearly two million word encyclopedia of political economy which was published in 1852-53. It is unquestionably one of the most important publishing events in the history of mid-century French classical liberal thought and is unequalled in its scope and comprehensiveness.

The DEP was designed to make political economy more accessible to a range of people who, in the view of the Economists, were confused about the operations of the free market. In this case the people the Guillaumin group had in mind were other economists, business people, elected government officials, and the senior bureaucrats in the Ministries. The Economists believed that the events of the 1848 Revolution had shown how poorly understood the principles of economics were among the French public, especially its political and intellectual elites. One of the tasks of the DEP was to rectify this situation with an easily accessible summary of the discipline.

The project was undertaken by the publisher Gilbert-Urbain Guillaumin (1801-1864) with the assistance of Charles Coquelin (1802-1852) as chief editor who died suddenly from a heart attack in August 1852 after having finished work on volume one. Guillaumin used his considerable editorial and organizational skills to publish what he thought would be an unanswerable riposte to the challenge posed by socialism. With funding organized by Guillaumin and with Coquelin (who was blessed with a near photographic memory) as the main editor the aim was to assemble a compendium of the state of knowledge of liberal political economy with articles written by leading economists on key topics, biographies of important historical figures, annotated bibliographies of the most important books in the field, and tables of economic and political statistics.

In keeping with their habit of calling themselves "The Economists" the editors and publisher of the Dictionary called it the "Dictionary of THE Political Economy."

Molinari was one of the main contributors on the project, writing 25 principal articles (most notably the important articles on "Free Trade" and "Tariffs") and 5 biographical articles. In the acknowledgements he was mentioned as one of the five key collaborators on the project. Other major contributors included the editor Coquelin (with 70 major articles), Horace Say (29), Joseph Garnier (28), Ambroise Clément (22), and Courcelle-Seneuil (21). Maurice Block wrote most of the biographical entries.

A massive undertaking like this would have taken several years to plan, write, and edit so it must have been at least in the planning stage when Molinari was writing Les Soirées during the summer of 1849. It was announced in the Guillaumin catalog of May 1849 as being "in preparation" and in a catalog from 1854 its price was listed as 50 fr.

We have made considerable use of the DEP in our research into French economic thought as it provides a great deal of information about French government policy, economic data on a broad range of topics, contemporary literature on economic thought, and most importantly, the state of mind of the French political economists in the mid-19th century.

What follows are some data about this massive project.

- there were 2 volumes with 1,854 pages of double-column text

- volume 1 was published in late1852, the last article by Coquelin was "Instruments du travail" which appeared at the the end of vol. 1, there is nothing by him in vol. 2, he died 12 Aug. 1852 from a heart attack

- there were 336 "Principal Articles" which were signed: vol. 1 A-I had 185; vol. 2 J-Z had 151

- the main editor Coquelin wrote 70 principle articles out of total of 185, all of which were in vol. 1

- Joseph Garnier wrote the next most principal articles with 28 principle articles [14 in vol. 1; 14 in vol. 2]; and 58 biographical articles [24 in vol. 1; 34 in vol. 2]

- Molinari wrote 24 principal articles [ 8 in vol. 1; 16 in vol. 2]; and 5 biographical articles [1 in vol. 1; 4 in vol. 2]

- most of the "Principal Biographical Articles" were unsigned but probably written by Maurice Block

- 50 of the "Principal Articles" were also "Principal Bibliographical Articles" with extensive annotated bibliographies of key works, of which Molinari wrote 6:

- Céréales,

- Colonies,

- Esclavage,

- Liberté des échanges (association pour la),

- Liberté du commerce,

- Propriété littéraire

- the 6 most prolific contributors to the DEP project were:

- Charles Coquelin 70

- the Say family 43 (JBS 7, Horace 29, Léon 7)

- Joseph Garnier 28

- Gustave de Molinari 25

- Ambroise Clément 22

- Courcelle-Seneuil 21

Announcement of the Publication of the DEP

Introductory Articles

PREFACE OF THE EDITOR (Guillaumin)↩

Source

“Préface de l’éditeur (Guillaumin),” DEP, T. 1, pp. v-viii.

Text

[v]

Every science has a certain number of dictionaries of varying comprehensiveness; political economy alone lacked one that met the needs of those who wished to consult it and be enlightened by its insights. This gap is what we sought to fill, and the warm reception our book has received, both in France and abroad, attests that we have produced a work as keenly desired as it is worthy, in every respect, of the eminent writers who have kindly collaborated with us.

To gain clarity on all economic questions and to form a reasoned opinion, there is no shortage of good books: numerous comprehensive or elementary treatises now provide the fundamental knowledge that every individual should possess. However, the didactic form of these works does not offer the advantages of the alphabetical format, which is particularly suited for research and useful for those unfamiliar with technical works or those lacking the time to undertake a specialized study.

Thus, the Dictionary of Political Economy serves as the indispensable complement to the fundamental treatises in the field. Despite the diversity of authors and the nuances of their opinions, all our efforts have been directed towards ensuring that a consistent general doctrine prevails, so that our book may serve as a guide to the reader amidst the sea of contradictory doctrines that have proliferated, particularly in our time. For this reason, we have deliberately titled it Dictionary of "the" Political Economy rather than Dictionary of Political Economy.

We have mentioned that political economy previously lacked a dictionary suited to its needs. Indeed, nothing comparable to what we intended to create and have now accomplished had been attempted, either in France or elsewhere. Ganilh’s Dictionary of Political Economy [1] was merely an incomplete attempt, whose insufficiency needs no demonstration. The General Repertoire of Political Economy, [2] published in The Hague a few years ago, consists of articles borrowed from various treatises or periodicals, and its author never claimed to have created a [vi] doctrinal work. This gave us full confidence in the success of our endeavor.

However, a dictionary limited solely to the terms of the science seemed incomplete to us; we believed that a bibliography of dedicated works, as well as a biography of the authors who wrote them, should serve as its complement.

For the first time, political economy will now have a complete bibliography, methodically arranged both by subject and by author name, allowing scholars, administrators, and all those seeking specific information to find an extensive and precise repository of references. [3]

To accomplish this immense task, it was necessary to examine, page by page, column by column, the ten volumes of La France littéraire by M. Quérard, the five volumes of Littérature contemporaine, which continue that work, and the Tables de la Bibliographie générale de la France. Additionally, we consulted Michaud’s Biographie universelle, the Biographie des contemporains, Custodi’s Collection of Italian Economists, a bibliography of Spanish economists by M. de Bona y Ureta; [4] the bibliographical notes of M. R. de La Sagra; the German biographical works of Ersch, Kaiser, and Hinrichs; Brockhaus’s Dictionnaire de la conversation; the Dictionnaire des sciences de l’État (Staats-Lexicon) by Rotteck and Welcker; the Archives of Political Economy by Rau; and the Journal of State Sciences of Tübingen. Above all, we relied on the highly specialized bibliography by M. MacCulloch, titled Literature of Political Economy.

M. Maurice Block, deputy head of the General Statistics Bureau of France, wrote a large number of biographical and bibliographical articles and translated into French the titles of works published in foreign languages. Other collaborators also participated in this effort: MM. A. Clément, Baudrillart, Gustave de Molinari, Maurice Monjean, and notably M. Joseph Garnier, to whom we owe numerous biographical and bibliographical articles that showcase his passion for erudition and his deep knowledge of economic literature. We take great satisfaction in knowing that readers will particularly appreciate the efforts made for this special section of our Dictionary, where many forgotten works have been brought to light, numerous errors and inaccuracies corrected, and where scholarly economists will find more than one remarkable discovery.

In the bibliographical articles, whether arranged by author names or by subject, we have generally classified the works in chronological order of publication, taking great care to reproduce [vii] their titles accurately and completely. For the most significant or remarkable works, we have added explanatory notes and assessments of their content. To accomplish this, we have borrowed extensively from the bibliographies of M. Blanqui and M. MacCulloch, as well as from critical articles in the Journal des Économistes and other authoritative publications. However, for living authors, for reasons of propriety that are easily understood, we have limited ourselves in the biographical section to brief factual notices, without commentary, and in the bibliographical section to evaluations borrowed from other works. No matter how sincere our desire for impartiality, it would have been difficult to discuss everything with perfect fairness, accuracy, and independence. In this regard, we were sometimes advised to abstain entirely. We did not deem it appropriate to follow this advice; given that a significant portion of economic literature is authored by living writers, our work would have been truly incomplete without details concerning these works and their authors. Moreover, we have observed that the brief biographical notices we have published have been received with great interest.

We entrusted the scientific direction of our Dictionary successively to M. Ambroise Clément and the late Charles Coquelin. M. A. Clément, one of the most esteemed contributors to the Journal des Économistes, whose character and person inspired the deepest respect among all our friends, had to leave Paris, and was succeeded in this honorable task by the late Charles Coquelin. Coquelin brought to the Dictionary the brilliant qualities with which nature had endowed him and the profound knowledge he had acquired: an extraordinary memory, sound reasoning, great diligence, a complete understanding of the masterpieces of political economy, deep respect for the founders of the science, a sharp appreciation of theories, and a remarkable familiarity with industry and economic facts in general.

After his regrettable passing—a loss deeply felt by the scientific community—our collective work was easily completed thanks to the direction established from the outset, and with the guidance and advice of our learned collaborators. We take the liberty of particularly mentioning M. Horace Say, who, through his knowledge and dedication to all matters related to political economy, is so worthy of the name he bears.

It will seem natural, no doubt, that after the success of this work, the publisher should claim for himself the idea and the plan of the book, which represents one of his principal claims to the esteem and affection bestowed upon him by the friends of science in general and by the collaborators of the Dictionary in particular. This new publication is, moreover, the complement of a collection of works whose project was conceived after the founding of the Journal des Économistes, a collection forming a coherent whole, and includes the Collection of Principal Economists, [viii] the Annuaire de l'Économie politique et de la Statistique, the Dictionary of Political Economy, the Universal Dictionary of Commerce and Navigation, and finally, the Library of Contemporary Economists.

Paris, September 10, 1853

GUILLAUMIN.

To allow the reader to grasp at a glance the full scope of the subjects covered in our Dictionary, we have appended a Table listing the principal articles along with their authors, as well as another Table containing all the biographical entries, with the names of their respective contributors.

We believed that the subscribers to the Dictionary would appreciate having portraits of the most eminent economists—those to whom the science owes the most. We were committed to ensuring that these portraits, all engraved on steel and of authentic resemblance, were executed with a degree of finesse worthy of the figures they represent.

The eight portraits included are of:

- François Quesnay, engraved by Outhwaite after the beautiful portrait by François, a renowned engraver of the last century.

- Adam Smith, engraved by Bosselmann after the only known authentic portrait.

- Malthus, engraved by Madame Fournier after the fine English engraving by J. Linnell.

- Turgot, engraved by L. Massard after a photograph of the statue that adorns the meeting hall of the Luxembourg Palace.

- J.-B. Say, engraved by Hopwood after the beautiful painting by Decaisne, owned by M. Horace Say.

- Sismondi, engraved by Eug. Gervais after the portrait by the celebrated engraver Toschi.

- Rossi, engraved by Eug. Gervais after a photograph of the admirable bust by Tenerani, owned by his family.

- Frédéric Bastiat, engraved by Madame Fournier after a daguerreotype print.

EXPLANATION OF ABBREVIATIONS

- The abbreviations Bl. and M.C. refer to the bibliographies of MM. Blanqui and Mac Culloch, mentioned earlier.

- Barb. refers to M. Barbier’s Manual of Bookselling.

- Biogr. univ. refers to the Biographie Universelle published by MM. Michaud.

- Fr. litt. and Q. refer to La France littéraire by M. Quérard.

Several contributors signed their work at various points using their initials. These correspond to:

- Ambroise Clément – A. C.

- Ath Gros – G. A.

- Charles Coquelin – Ch. C.

- Courcelle Seneuil – C. S.

- Gustave de Molinari – G. de M.

- Horace Say – H. S.

- Joseph Garnier – Jph G.

- Jules de Vroil – J. V.

- Maurice Block – M. B.

- Jacques de Valserre – J. de V.

Endnotes to the Preface

[1] See GANILH.

[2] See SANDELIN.

[3] Until now, economic bibliography consisted of a short list of major works appended to Skarbeck’s Theory of Social Wealth, a considerably more extensive list compiled by M. Blanqui in his History of Political Economy, which is remarkable for its insightful annotations; and finally, M. Mac Culloch’s Literature of Political Economy, which is much broader still and highly valuable for the scholarly assessments it provides, but far from being as complete as ours.

[4] Clave de los Economistas, Madrid, 1850, octavo volume of 70 pages.

INTRODUCTION BY CLÉMENT↩

Source

“Introduction (Ambroise Clément),” DEP, T. 1, pp. ix-xxvii.

Text

[ix]

I.

In scientific research as in industry, the division of labor is one of the essential conditions of progress. It is therefore reasonable to make each of the various orders of phenomena to which these inquiries apply the object of a distinct and well-defined science, at least insofar as the nature of the facts to be studied allows.

The science whose principles this Dictionary aims to set forth and develop has often been criticised for failing to establish the limits of its domain, or for having frequently overstepped them by extending its investigations into certain orders of facts that belong to other social sciences, such as politics, legislation, and morality. But these criticisms, although sometimes made by eminent minds and even by economists themselves, seem to stem from somewhat confused ideas about the nature or interrelations of social phenomena in general. For upon reflection, one soon recognizes that these phenomena are too closely interconnected to allow for their study to be divided by impenetrable boundaries, and that none of the social sciences can be completely expounded without making some incursions into the domain of the others. [1]

"Political economy, for instance, would not be able to show us the causes of the increase or decrease of wealth if it remained outside of the domain of legislation, if it did not explain the effects of a multitude of laws, regulations, and treaties concerning currency, commerce, manufacturing, banking institutions, and the commercial relations of nations. In turn, the scholar engaged in the study of legislation would treat laws in a very imperfect manner if he did not demonstrate the influence they have on the growth, distribution, or reduction of wealth... It is equally impossible for the scholar who describes the civil or political institutions of a nation, and the moralist who investigates the causes of their virtues or vices, not to trespass alternately on each other’s territory."

The moral sciences are connected to one another, not only through the intimate relationships [x] that exist between the different orders of phenomena they are tasked with revealing but also through a common goal, which we believe can legitimately be assigned to them: to shed as much light as possible on the true interests of societies. The most that can be established regarding their distinct characteristics is that, in pursuing this common goal, each of them is called to focus more particularly on one specific order of social phenomena rather than on all others, without, however, being able to entirely neglect the latter. Thus, politics and legislation are primarily concerned with the organization of societies from the perspective of national defense and the protection of persons and property; they must determine the limits that should be placed on individual liberty in the interest of the liberty of all, establish the rules of justice to be applied in disputes between individuals, etc. But they could not clearly distinguish the interests of societies in these respects without relying on the insights provided by political economy and morality. Likewise, morality, in seeking to determine which habits or principles of private and public conduct are most favorable to the improvement of individuals and societies, could not provide reliable guidance without taking economic truths into account. Finally, political economy, by concentrating its investigations more particularly on the phenomena by which wealth is produced, distributed, and consumed, could not disregard the influence exerted on these phenomena by political institutions, legislation, and customs without confining itself to sterile abstractions.

This interconnectedness of the social sciences will always prevent each of them from being defined in a way that confines it within exclusive and strictly determined boundaries. For, again, to prohibit it from making any excursions beyond the limits assigned to it would be to mutilate it. This is as true for Legislation, Politics, and Morality as it is for Political Economy. But while the scope of each of these sciences cannot be absolutely delimited, they can easily be distinguished by the specificity of their objectives. The aim of Political Economy has been sufficiently determined: it is, as we have indicated, to explain the nature, causes, and results of the phenomena of production, distribution, and consumption of wealth, focusing on the general characteristics of these phenomena without, for instance, delving into the technical processes of various industries. More importantly, its role is to illuminate as fully as possible the social conditions that are favorable or detrimental to the richness of general production, the equitable distribution of products, and their advantageous use.

If this, indeed, is the special task of Political Economy—and we believe it would be difficult to dispute—one will recognize that it would be of little use to seek alternative definitions for it. It is thereby sufficiently distinguished from the other social sciences, without limiting the scope of its investigations beyond the point at which it ceases to find useful assistance for the proper fulfillment of its mission. We therefore believe we may refrain from further elaboration on this point and proceed to other considerations.

[xi]

II.

Under the regime to which public education has been subjected by our governments, the dissemination of knowledge in political economy has proceeded with excessive slowness. As a result, our country ranks among those where such knowledge is least widespread, not only among the general population but even among the more or less educated classes, where the majority have no understanding of this science and are entirely unaware of the importance of the problems it seeks to solve. Yet the studies it encompasses are surely among the intellectual pursuits that should most universally arouse interest, for their results are destined to exert the most considerable and beneficial influence on the fate of nations. No other branch of study can offer societies as much illumination to guide them along the paths of true civilization and to help them avoid those that lead to decline and ruin.

The history of our political revolutions over the past sixty years abounds in lessons that confirm the truth of these assertions. Surely, in a nation less ignorant than ours of economic truths, public opinion would not have allowed national energy to be misdirected into the regressive and ruinous paths it has so often followed since 1793. Had general opinion been less backward or less distorted in this regard, the liberal and genuinely civilizing momentum of 1789 would not have so quickly strayed into the foolish or deplorable directions it soon took. One would not have seen, for instance, a nation seeking to base its existence on free labor striving instead to adopt the ideas and customs of ancient societies that built theirs on war, plunder, and slavery. Later, the warlike dispositions provoked by the necessity of national defense would not have degenerated into a spirit of conquest and domination. We would not have become infatuated with a military glory that consists merely in success on the battlefield, regardless of its purpose or even when it results in a regression toward barbarism—a savage and blind sentiment, the enthusiasm for which has, more than any other cause, delayed the moral and political progress of Europe. We would not have witnessed the laws of maximum prices, the reckless issuance of assignats, the Continental System, licensed trade, and the entire succession of disastrous or absurd measures that betrayed either a complete ignorance ofsociety's interests or a supreme contempt for them. But among all the errors from which the light of political economy could especially have saved us, had it been more widely disseminated, the most consequential has been the establishment of that governmental and administrative system which, by multiplying the powers of public authority to the point of subordinating everything to its direction, seems intent on annihilating individual initiative and strength, leaving only the collective power intact. This system, which has continued to worsen over the past thirty years, increasingly substitutes harmful activity for useful activity by diverting the faculties and efforts of an ever-growing number of individuals from the management of material resources to the management of people themselves. By burdening our governments with responsibilities as unlimited as their powers, it has become the principal cause of their instability and the insecurity that results from it. %%xii%% Finally, in recent times, this system has appeared to reach its extreme limit, presenting as a legitimate question the complete absorption of all labor by the State and the coming of universal communism.

Nor should it be believed that these latest economic aberrations are the product of ignorance peculiar to socialist sects. In this respect, the self-styled conservative parties have not demonstrated greater enlightenment. If they resisted the tendencies that sought to transform labor still partially free into public services, to further expand governmental regulation, and to increasingly weaken individual initiative and responsibility, it was not because they had any fundamental aversion to the system itself, nor because their views were based on principles markedly different from those of their adversaries. For they, too, had long accepted or proclaimed that there are no fixed limits to State intervention, and that it is the government’s role to direct social activity in all its developments. The only difference was that, in adopting this pernicious principle, they wished to retain exclusive control over its applications. Nevertheless, for the needs of the moment, they readily leaned on the truths proclaimed by political economy. They professed, along with it, that there is no productive economy and no equitable distribution of goods except under conditions of free labor and free exchange; that each individual must bear responsibility for his own fate; and that, while the instincts of the heart and the dictates of reason command us to assist the unfortunate to the best of our ability, no one has the right to shift onto others the responsibility of securing work or making a living. They asserted that the public authority exists to protect the person, liberty, and property of all, but that it has no rightful power to dispose of each individual’s faculties or their produce, to take from some to give to others, or to shield by law the idle, the reckless, and the parasitic from the consequences of their own conduct at the expense of those who lead an opposite way of life.

Yet these clear truths suddenly became obscured in their eyes whenever the question arose of applying them to existing abuses. If they declared themselves in favor of freedom of labor, it was with the condition that this freedom would not extend to the numerous professions monopolized or subjected to restrictive regulations. If they rejected the idea that the State should take from some to give to others, they were nonetheless unwilling to tolerate any challenge to the legitimacy of subsidies, grants, or special guarantees bestowed upon various enterprises benefiting from government support. If they denounced parasites, it was without questioning the voracious parasitism they themselves had created by inflating governmental powers and expenditures. If they strongly opposed the authority of the day directing the productive capital of the nation and preventing individuals from freely disposing of their faculties and the fruits of their labor, they defended with equal vigor the commercial legislation which, through prohibitive tariffs and restrictions, produces precisely those effects.

Thus, some demanded privileges, aid, and largesse from the State on behalf of the working classes, from whom they sought political support; others sought them only for those already in possession of wealth. Political economy, by contrast, would have granted them to no one, since one of its fundamental conclusions is that each should retain what belongs to them and that neither authority nor law should ever be used [xiii] to rob some for the benefit of others. Deeply hostile to legal plunder, [2] regardless of the form it takes or the banner under which it is carried out, political economy inevitably displeased all those who sought to profit from it. As a result, it has been alternately proscribed by both opposing camps. After the attempt in 1848 to subordinate its teaching to the perspective of the organization (by state force) of labor, there followed in 1850 an effort by the General Council of Agriculture, Manufacturing, and Commerce to impose upon professors of political economy the obligation to tailor their lessons to align with France’s existing commercial legislation—that is, to justify the protectionist or prohibitive system.

But political economy must be taught from only one perspective: that of the exact observation of the nature of things. It is self-evident that any attempt to impose different foundations on its teaching would transform it into something entirely other than a science. Sciences do not admit of preconceived conclusions; the conclusions they reach are merely the results of understanding facts and their relationships. Surely, it would be no less absurd to demand that astronomy be taught from the perspective of the Ptolemaic system than to insist that the teaching of political economy serve to justify protectionism or any other predetermined system, independent of empirical observation.

III.

Among the various forms that may be used to present political economy, the dictionary format appears particularly suited to the rapid dissemination of its key concepts. A large number of individuals engaged in public or collective affairs, who would find invaluable guidance in these concepts for fulfilling their responsibilities effectively, nevertheless refrain from acquiring them because doing so would require dedicating a great deal of time and attention to the study of systematic treatises. A well-conceived and comprehensive dictionary, by allowing them to break up this study, selecting at will the questions that current events or the course of affairs make particularly relevant, can gradually introduce them to economic truths and inspire in them the desire to understand the subject as a whole.

On the other hand, those who have pursued this study without making it their primary occupation or without returning to it frequently often struggle to retain all its principles and their interconnections. As a result, they may find themselves at a loss when confronted with difficulties or objections that, in reality, have little significance. A dictionary can provide them with the means to quickly retrieve the necessary concepts to resolve such questions.

Such a work thus appears to us more likely to be frequently consulted than systematic treatises, thereby rendering it of more practical and widespread utility. But was it possible, given the current state of the science, to produce a good Dictionary of Political Economy? Was the attempt premature? Have prior works on this subject established a sufficiently coherent set of principles to explain the full range of economic phenomena and to theoretically resolve [xiv] the numerous related questions? Have each principle and each solution been brought to the level of clarity required to be expressed with the conciseness demanded by the dictionary format? We hope that competent judges will find that the collective work we are publishing satisfactorily addresses these concerns. Unfortunately, truly competent judges in political economy are few in number, and even fewer in France than in several other countries. This science is scarcely known to most of our statesmen, administrators, and journalists, except through the self-interested or uninformed attacks that have been directed against it for the past twenty years. Moreover, they generally share the prejudices carefully fostered against it by all those whose interests lead them to fear the enlightenment which comes from its study, and when they do not go so far as to proscribe it outright as a dangerous utopia, they prefer to classify it among purely hypothetical systems. The least hostile among them, while not disputing the truth of its theories, deny it any practical application. Some, however, are willing to concede that several of these theories will need to be applied someday, but they postpone their implementation to such a distant future that it becomes discouraging for the present generation—not merely to allow time for public opinion to evolve toward the necessary reforms, but because they believe that a long-term postponement is necessary to complete and better establish the foundations of the science, which they still consider insufficiently developed.

Despite the deep respect we have for the founders of political economy, we are far from believing that new investigations cannot enhance the utility of their work or even correct any incompleteness or errors in some of their views. Like all other branches of human knowledge, political economy is infinitely perfectible. However, we are convinced that it has now reached a stage where no legitimate doubt remains regarding its essential principles, and that the truths embodied in these principles will no more be shaken by future research or discoveries than the elements of geometry or the laws of universal gravitation have been undermined by the works of Lagrange or Laplace. We believe we can confidently assert that, among all the sciences concerned with man and society, political economy is the most precise and least incomplete; that it is incomparably more advanced than politics proper, more advanced than what is taught today under the name of philosophy, and even more advanced than the sciences of legislation and morality. Without it, one cannot engage in politics, philosophy, legislation, or morality in a way that is useful or true.

Certain disagreements among economists have been noted in their writings and exaggerated as much as possible in order to suggest that none of their principles are firmly established. However, little attention is paid to the vast array of truths on which they are in complete agreement. Or, to find contradictions, the title of economist is conveniently granted to writers who have no rightful claim to it. It is also overlooked that no science, not even pure mathematics, has been or remains entirely free from disagreements among those who study it. The various fields of geology, physics, zoology, chemistry, etc., have all been the subject of differing interpretations by the scientists who have observed them. Yet no one has ever concluded from these disagreements that these sciences [xv] are uncertain or lack established principles. Why, then, is political economy, which is just as rich in confirmed truths, accorded so much less credibility? This can be attributed primarily to two causes, which merit discussion.

First, the principal objects of economic study—labor, exchange, value, capital, etc.—were matters of universal concern long before the science was founded, and even today, most people engage with these topics without understanding the need for scientific guidance. It is therefore unsurprising that many individuals believe themselves competent to form opinions on all the questions raised by these subjects, which are so familiar to them. However, these opinions, based on an incomplete view of economic phenomena, their more or less distant consequences, [3] and their interrelations, often diverge from the truths that only thorough and generalized study can reveal. Once adopted, however, these opinions have resisted scientific demonstration with the usual obstinacy of prejudice.

Secondly, economic legislation in societies was formed in the absence of any true scientific knowledge and in accordance with prevailing prejudices. Thus, political economy could not reveal and denounce the flaws in this legislation without alarming numerous interests that were founded by law on error or injustice.

Political economy was therefore bound to attract not only preconceived opinions against it but also the active and persistent hostility of illegitimate interests that it might threaten. These are the principal obstacles that, by maintaining real or feigned doubts about the certainty or effectiveness of its principles, delay the dissemination and consequently the application of the salutary truths it has brought to light.

However, these obstacles will weaken. The interests that were founded unjustly and that political economy might unsettle are infinitely fewer and less significant in their overall impact than the legitimate interests it is meant to serve. As the latter become more enlightened, they will lend it stronger support, and a day will come when, through their backing, it will acquire an irresistible force.

That day has already arrived in England, where fundamental economic truths have permeated public opinion and are dismantling, with an unexpected ease, abuses that had been deeply rooted for centuries and were upheld by powerful interests.

In the United States, the profound good sense of Franklin and the other founders of the Union had, so to speak, anticipated economic theories. The institutions of that country—except in those states where slavery still exists—seem to have been inspired by the soundest doctrines of the science. No other nation has so completely confined the action of public authority within rational limits, nor founded institutions that afford as much freedom to labor and transactions while protecting the development of useful activity and offering so little scope for or encouragement to harmful activity.

Public opinion, moreover, is beginning to move in the same direction in Belgium, Piedmont, and several parts of Germany and Italy, where political economy holds a notable place in public education. The same is true in Spain and Russia. Of all the states in Europe, France is the one that has participated the least in this civilizing movement over the past twenty years. However, it will inevitably be drawn into it, perhaps sooner than those who strive to keep it lagging behind in this regard might expect—either by the example of more advanced nations or by the very excesses of the abuses it would endure [xvi] if it continued much longer to resist economic truths as recklessly as it has done so far.

IV.

To justify what we have said about the progress of political economy and the magnitude of its mission, we shall recall some of the truths it teaches—without straying from general considerations and without delving into details that properly belong to the articles in this Dictionary.

Had the Earth remained in its primitive state, human beings would neither have multiplied nor progressed in any sense; they would have remained as scattered tribes in the forests, living by living by preying on other creatures like various species of animals. Perhaps they would even have disappeared altogether, unable to overcome the exceptional difficulties of their original existence. But they were endowed with a marvelous faculty: the ability to make use of the elements of creation in ways that increasingly appropriated them to serve the needs of humans. It is through the exercise of this faculty, through the prodigious developments it has undergone over time due to the accumulation of the means of labor and the successive discoveries of human intelligence, that our race has truly become the master of the globe. It has been able to spread its numbers across all habitable regions and elevate the conditions of its physical, intellectual, and moral existence to the heights we now witness among the most advanced nations.

This powerful faculty is what political economy designates by the term industry. The exercise of industry is indicated by the word labor. The results of labor, consisting of all types of utilities applicable to our needs, are called products, and when products are preserved or accumulated, they constitute wealth.

Although wealth has always been ardently sought, the labor that creates it has not always been honored by public opinion. The most famous people of antiquity—including those that our public education system still presents as models for schoolchildren—long regarded it as incomparably more noble and meritorious to rob workers of the wealth they had produced than to engage in production themselves. These peoples valued only sterile or plundering occupations, particularly those associated with war and the exercise of domination. As for productive labor, it was generally an object of their disdain, and nothing seemed more degrading to them than engaging in it. This peculiar contempt for the use of humanity’s highest and most admirable faculty persisted throughout the centuries, gradually weakening, until times not far removed from our own. Even today, it has not been entirely erased among all classes of the European population.

It was the role of political economy to completely rehabilitate productive labor, and it has done so in the most striking manner. On the one hand, it has demonstrated that labor is the source of all wealth, the true foundation of society's existence, the principal agent of civilization, and the essential condition of all progress and prosperity. On the other hand, it has established that intelligent populations [xvii] must henceforth grant to productive labor the esteem and respect long usurped by plundering activities, and that they must make every effort to recognize the latter in all its various disguises so as to brand it with all the contempt and shame it has so long inflicted upon productive activity.

We have stated that one of the objectives of political economy is to elucidate the social conditions that are either favorable or detrimental to the fertility of production and the equitable distribution of wealth. These conditions primarily concern either the degree of freedom granted to industry by political institutions or the manner in which the general products of labor are distributed. We shall briefly outline the conclusions of the science on these two fundamental points.

First, the freedom of labor and economic transactions is one of the essential conditions for productive fertility. This is because, on the one hand, it allows each individual to follow the dictates of personal interest in choosing the occupation best suited to his circumstances, preferences, or particular skills, and personal interest, all things considered, is generally the surest and least fallible guide in this matter. On the other hand, it maintains the broadest possible competition across all branches of productive labor, to the extent permitted by the nature of things, and competition is unquestionably the most powerful stimulant to activity and improvement in labor.

Consequently, anything in social institutions that restricts this freedom is harmful to the fertility of production. This is surely the characteristic of legal monopolies, which grant exclusive rights to certain privileged corporations or governments to engage in specific trades or professions; of regulations whereby public authority seeks to direct the course of particular branches of productive activity; and of legal restrictions on the freedom to trade, which necessarily limit the freedom to work, etc.

Secondly, since our industrial faculties vary in nature and strength from one individual to another, and since their productivity is generally proportional to the vigor with which they are applied—an effort that can have no more powerful incentive than personal interest—it is easy to see that the only just and effective means of distributing the useful things they produce is simply to leave each individual in possession of and with full disposal over the fruits of his labor. In other words, the right to property must be upheld.

Any disruption of this natural distribution of products, whether through violence, fraud, or ignorance, constitutes an obvious injustice, as it deprives some of what they have produced and assigns it to others. At the same time, it reduces the extent or security of the enjoyment that is the general aim of all efforts, inevitably leading to a decrease in productive activity and capability.

For property to be established and wealth to grow, labor alone is not enough, for its results may be consumed more or less quickly. It must be accompanied by saving, which cannot be encouraged unless each individual is guaranteed not only personal enjoyment of his earnings but also full and unrestricted disposal of what he has produced, including above all the ability to transmit it to his children, his family, or those dear to him. Without this guarantee, the incentives [xviii] for labor would lose much of their force, and the accumulation of wealth would be incomparably smaller. Each person would be encouraged to consume during his lifetime all that he had acquired, and successive generations would inherit no increased reserves from their predecessors. Instead, existing accumulations would tend to diminish over time, and industry, soon deprived of capital, would become impotent.

It is true that this ability to transfer property results, over time, in significant inequalities among families. However, when property and productive liberties are fully guaranteed, inequality of wealth can arise—except in rare cases—only from differences in production and accumulation attributable to those who possess them. Such inequality is thus merely the recognition of justice: families that, over multiple generations, have exercised well-directed industry, enlightened foresight, and prudent economy are justly rewarded with the comfort they attain; whereas those that follow the opposite course, whose members give themselves over to laziness, intemperance, and various vices, are justly punished by the poverty that inevitably overtakes them. It is essential that they should not be able to escape this condition except by adopting better conduct. This is useful and indispensable for the improvement of human life, and a social system that either sought to maintain the supremacy of certain classes over others or aimed to establish a forced equality among all classes—thereby preventing the natural consequences of good and bad habits from falling primarily upon those who practice them—would be equally disastrous in both cases.

Experience fully confirms these theoretical results. The history of all times and all nations proves that societies are more prosperous and advanced in proportion to how well they safeguard, through their customs and institutions, productive liberties and property against the infinitely varied threats posed by plundering activity. This has been the principal condition determining the fate of nations thus far; those that have best observed it are the most advanced in all essential respects, while those that have least respected it are the most backward and miserable. If some ancient people managed to achieve a temporary degree of material prosperity while deviating from this condition—by basing their existence on war, pillage, or slavery—or if, within each nation, certain classes managed to organize themselves so as to enslave others and live at their expense, this was only accomplished at the cost of the general misery of the majority, the arousal of widespread hatred, and the development of corruption among the ruling population or classes, which always led to their decline and ruin.

On the other hand, attempts to maintain a false equality among human societies by establishing communal ownership of labor and goods have all failed miserably. By disregarding the natural inequalities among men and treating superior faculties as equal to the lowest ones, such systems have destroyed the essential incentive of personal interest and reduced all activities to the level of the least intelligent and least productive. [4]

"The evils that weigh upon a nation," wrote the profound writer we have already cited, "are always equally grave, whether a portion of the population appropriates the products of the labor of others, or whether the [xix] individuals who compose it aspire to establish among themselves an equality of goods and ills. It follows that inequality among the individuals of a nation is a law of their nature; that men must, as far as possible, be enlightened about the causes and consequences of their actions; but that the most favorable position for all forms of progress is one in which each person bears the consequences of his vices, and no one can take from another the fruits of his virtues or his labor."

The insights of political economy alone have been able to complete the knowledge necessary for this important demonstration. At the same time, they have provided a wealth of indispensable ideas for recognizing, amidst all social complexities—whether in institutions, laws, private or collective actions—the often concealed and sometimes difficult-to-detect presence of that perverse activity that continually seeks to appropriate the fruits of productive labor.

(line break here??)

One of the most concrete and useful branches of political economy is that which explains the social phenomena through which the general exchange of products or services takes place.

It is well known that the division, or rather the specialization, of professions and labor is one of the principal sources of the power of industrial. Without this condition, industry would be entirely incapable of meeting the numerous and diverse needs of civilized societies. However, this necessity obliges each worker to engage in the production of uniform goods, while his needs require a variety of products, thereby making exchange indispensable.

In a primate state of society, exchange consists of direct barter, the trade of one good for another. But as needs develop and goods to be exchanged multiply and become more specialized, the inefficiency of this method becomes apparent. People then feel the necessity of adopting a uniform intermediary, one whose qualities make it universally accepted as an equivalent in transactions. This intermediary, whatever its nature, constitutes money once it is generally accepted. Gold and silver currencies have become universally used; the long habit of evaluating everything by these metals, seeing them as the equivalent of all products, led people for a long time to consider them as the supreme form of wealth, or even as the only form of wealth. From this misconception arose numerous prejudices and errors, which, due to the insufficient dissemination of economic knowledge, still hold a significant place in public opinion.

It is on this false notion of wealth that the still-prevalent belief among many writers and statesmen is based—that taxation cannot be a cause of impoverishment for the country that bears it, on the grounds that the money collected is returned to the nation through government expenditures. This same prejudice still leads people to claim daily that the purchase of foreign goods constitutes a tribute paid to other countries. The same error also underlies the theory of the balance of trade, which maintains that each nation should consider [xx] the excess of its exports over its imports as a gain, while any surplus of imported goods over exported ones should be counted as a loss—since in both cases, the difference is likely settled in money, and money, being wrongly assumed to be the only form of wealth, is thought to be the only thing that can constitute either a loss or a gain.

Nothing is more rigorously exact than the demonstrations of political economy on these various points. It has clearly shown that gold and silver, far from constituting all wealth, make up only a very small part of it (they likely represent no more than one-fiftieth of the total accumulated value). The value of money, moreover, like that of any other product, derives first from its utility as a means of facilitating exchanges and second from the costs required to obtain it. The amount of money commonly exchanged for a hectoliter of wheat has as much value as that quantity of wheat—but no more. There is no justification for assuming that one of these values is inherently more precious than the other. In fact, there are strong reasons to believe that, for a nation as a whole, wealth accumulation in the form of money is less advantageous than in any other form. Money is fundamentally different from all other products in that it serves our needs not in proportion to its quantity, but solely according to its value. Consequently, the value of money necessarily declines in any country where its quantity increases significantly. Thus, there is no reasonable basis for encouraging a nation to prefer money over other equally valuable products.

It is as absurd to claim that we pay tribute to foreigners by purchasing their products as it would be to consider the consumer of bread a tributary of the baker, or the baker a tributary of the flour merchant. The theory of the balance of trade is nothing but folly; it is ridiculous to assert that a nation loses in its commerce with foreigners when it receives more in value than it gives in exchange, and that it gains, on the other hand, when it gives more in exchange for less. Differences between imported and exported values are generally balanced among nations through the use of debt between one country and another, settled via bills of exchange, and they rarely result in substantial balances needing to be paid in money. But even if this were not the case, no conclusion could be drawn about gain or loss from such transactions. It is highly probable that, if customs records accurately reflected the values of imported and exported goods, they would show import surpluses everywhere, as such surpluses are essential to provide profits for merchants, who would soon abandon trade if it yielded more losses than gains. Finally, taxpayers would have to be exceptionally naïve to believe that governments return their taxes simply by spending them, since the money collected for these expenditures is only returned to the country in exchange for goods or services of equivalent value.

The insights of economic science are equally reliable when it comes to the use of banknotes, which to some extent perform the function of money. Political economy demonstrates that these notes, being nothing more than debt instruments, add absolutely nothing to existing wealth; their sole function is to transfer the right to dispose of a portion of that wealth from one person to another. This function is also fulfilled by metallic money, but there is [xxi] a fundamental difference between the two: gold and silver money inherently carry their own value, whereas banknotes or similar instruments only represent a claim to value, which may or may not exist. Nevertheless, as long as these notes are widely accepted with confidence, they can substitute to some extent for real money and thereby provide a significant savings in precious metals, while also serving as a highly convenient medium of exchange.

However, these advantages come at a high cost whenever the issuance of banknotes is not carefully regulated and their redemption in metallic currency on demand is not sufficiently guaranteed. This leads to an excessive and harmful expansion of credit. The credit enjoyed by banks, encouraged by the ease of increasing discounts through increased issues, extends through their notes to many individuals who would not otherwise obtain credit and who often use it not to create but to dissipate wealth. Moreover, the growing abundance of this exchange medium depreciates it progressively, even though the notes retain the same nominal value, causing an artificial rise in the prices of goods and services and serious disruptions in all transactions, especially when banknotes are given forced legal tender status.

In presenting these principles, political economy in no way seeks to prohibit the prudent use of such instruments as a means of facilitating exchanges and credit. Rather, its aim is to protect people from the dangers of excessive or reckless use and from the illusions to which they are too often susceptible in this regard.

After clarifying the nature and true functions of money and its representative symbols, political economy must still provide a complete understanding of the natural laws governing the general exchange of products and services. To this end, it has successfully established firm principles regarding the conditions that determine the value of each good or service.

Not all objects of human need are exchangeable. Many, such as light and warmth of the sun, breathable air, and other naturally abundant resources, are provided freely by nature and are enjoyed without effort or the need to give anything in return. In contrast, other goods, which can only be obtained through personal effort or capability, constitute private property and are not voluntarily given away except in cases of donation, inheritance, or similar circumstances. The quality that distinguishes exchangeable goods from non-exchangeable ones is what political economy defines as value. Value varies among different goods and can be measured in each by the quantity of any other valuable good it can command in exchange. Since money serves as the universal medium of exchange, the value of each product or service is ordinarily expressed in terms of a specific amount of money, and this monetary expression of value is called price.

In general, the difference in price between two valuable objects of different kinds arises from the difference in their production costs—that is, the difference between the values of the services or products required to create each of them. It is understood that, under conditions of complete freedom in labor and transactions, the price of a certain category of goods could not long remain significantly [xxii] above production costs. This is because the exceptional advantage of producing such goods would attract competition, which would soon drive prices down. Conversely, it is evident that a production yielding only losses would not continue under such conditions; its quantity would decrease until prices rose at least to the level of production costs.

With these conditions implied, the market price of products or services depends on the relationship between the quantities supplied and demanded of each: if supply increases more than demand, the price falls; if demand increases more than supply, the price rises.

This is the general law governing the relative value of different products or services.

This law allows free labor to maintain—far better than any system based on coercion could—constant proportionality in each of the many and diverse branches of industrial activity between the quantity of each type of product and the extent of the demand for it. If supply exceeds demand, the resulting surplus is immediately signaled by a price drop, leading to reduced production. Conversely, if production falls short of demand, rising prices indicate this shortage and soon encourage an increase in output.

Another consequence of this law is that the price of industrial services inevitably declines when these services are more widely supplied than they are demanded. Since the services most exposed to competition and most susceptible to being oversupplied are generally those of workers in the poorest classes, political economy concludes that these workers have the greatest interest in exercising prudence and restraint before and during marriage, so as not to recklessly increase their numbers and as a result the supply of their services which are already too low.

Another significant result of this fertile law is that the multiplication of capital tends to lower the cost of its use, making it increasingly accessible to those who can employ it productively. Since workers’ labor is more in demand—and therefore better paid—when capital is abundant, political economy further concludes that the working classes have a strong interest in the growth of capital and in all factors that promote it: the dynamism and progress of industry, the accumulation of savings, and especially the maintenance of public security, which is an indispensable condition for the preservation and expansion of capital.

One of the most elegant and solid theories derived from the study of the social phenomena underlying the general exchange of products and services is the theory of markets, so admirably formulated by J.-B. Say. According to this theory, what is ultimately exchanged are products for other products; therefore, every product serves as a means of exchange and a market for others. It follows that the broader and more prosperous the overall production, the greater and more advantageous the market becomes for each specific type of labor. It also follows that different industries share common interests, as no single industry can experience prosperity or hardship without affecting the others to some degree. It has long been understood that rural areas [xxiii] are interested in the prosperity of cities, just as cities are interested in the prosperity of rural areas, because each finds a more favorable and accessible market for its respective products. However, these interdependent interests extend to all branches of industry and are equally evident in trade relations between nations. When a country is progressing and prospering, all nations engaged in trade with it benefit, either because it provides abundant market opportunities or because it supplies goods at lower prices. For example, the phenomenal economic growth of the United States has benefited many branches of our industry to such an extent that the ruin of that country, if it were possible, would now be a great calamity for a significant portion of our population. Nations are thus bound together in both prosperity and adversity; their true interest lies in expanding mutual services by increasing trade rather than in weakening and harming one another, as blind political policies have too often encouraged them to do.

Relying on these truths and invoking the respect due to property rights, political economy calls for the freedom of international trade. Such freedom would enable all nations to share in the highly diverse natural advantages that God has distributed unequally across the globe. It would expand the network of interests that already connects civilized nations—despite all the legislative barriers to trade—to the point of establishing a solidarity as evident as that which unites the various provinces of a single state. Ultimately, it would render international wars as unpopular and impractical as they would be today between the different regions of France.

(insert section break here??)

Political economy has improved morality by providing solid foundations for evaluating numerous sentiments, actions, and habits that prejudice had misclassified. Significant moral progress has been achieved through the complete rehabilitation of productive labor and the acquisition of a set of positive notions that allow a clear distinction between useful and harmful activities, giving each its proper place in public esteem. The demonstration of the solidarity that binds the interests of different segments of humanity is another immense moral advance. By exposing the absurdity of national hatreds and rivalries; by showing that these are the blind and unworthy sentiments of civilised human beings, although this ignorance and political charlatanism have often been honored wit the name of patriotism, political economy has significantly weakened the inclination toward war among the most influential classes. This has paved the way for the eventual abandonment of large standing armies, one of the most powerful causes of the poverty of nations and, consequently, of all the moral failings and disorders that this poverty engenders. Another important improvement in morality, owed to the insights spread by political economy, lies in the ability to justly assess the relative merit of different uses of wealth. For example, [xxiv] extravagance and ostentation, long praised because they were confused with generosity or selflessness—and especially because they were mistakenly believed to stimulate industry—have been definitively relegated by economic reasoning to the category of harmful and thus immoral habits. Meanwhile, thrift, often maligned as a sign of selfishness or avarice and also thought to deprive labor of resources, has been definitively recognized as one of the most beneficial and therefore most virtuous habits for humanity. Political economy has made unmistakably clear a truth that seems still largely ignored by most public figures: that the habit of luxury or lavish spending, far from sustaining industry or labor, actually leads to the destruction of what keeps them active. A value saved and consumed productively in an industrial operation provides the working classes with infinitely more employment and a higher standard living than an equal value consumed unproductively on a feast, a ball, a festival, or other similar expense. This is because, in the first case, the consumed value continues to employ workers as long as it is reproduced, potentially indefinitely, whereas in the second case, once consumed unproductively, it disappears forever after having supplied the same amount of labour one time only.

One of the most significant advances that moral sciences owe to the research of economists is the improvement of the concept of freedom.

Freedom has long been a major aspiration among many European people, but they pursue it instinctively, without clearly understanding what constitutes it or the conditions necessary for its maintenance and development. It was left to political economy to demonstrate that freedom is equivalent to actual power and that we become freer as we succeed in expanding our control over raw materials or in better subordinating our own activity to the directions that can make it most effective. This is how we progressively reduce the obstacles that hinder the satisfaction and expansion of our needs, the fruitful use and refinement of our physical, intellectual, and moral faculties—in short, the improvement and diffusion of human life.

These obstacles arise either from nature or from other human beings. Industry's mission is to overcome the former; thus, it has succeeded, for example, in domesticating and multiplying useful animal species while limiting the spread of harmful ones—in replacing, over vast areas, wild vegetation of no use to us with cultivated plants that best meet our needs—in overcoming the barriers that rivers, mountains, and the vastness of the seas once posed to relations between nations, and so on. As for the obstacles stemming from man himself—his ignorance, passions, greed, and inclination to subjugate and dominate his fellows—industry indirectly contributes to their mitigation by providing the indispensable means for the growth and spread of knowledge. [xxv] Nevertheless, such obstacles diminish as we better anticipate all the immediate or distant consequences of our actions and habits and as we adjust our conduct to align with this foresight. They also weaken as the sentiments of dignity and justice spread, as individuals become more willing to resist courageously any form of violence or unjust encroachment on their person or property, and as they develop a scrupulous respect for these same rights in others.

From these combined conditions, it follows that the freedom of nations increase as they become more industrious, enlightened, and moral. Consequently, freedom is proportional to a nation's level of advancement in these respects, and it is futile for any people to aspire to be freer than what their level of industry, knowledge, and morals can sustain. [5]

Since 1789, the French nation has repeatedly found itself in control of its governmental establishment, and although its general inclinations leaned toward liberty, the false notions it had adopted on this point prevented it from successfully establishing institutions capable of achieving that goal. Most of our politicians have always regarded the institutions of government as the primary, and almost the sole, organs of social life, as forces from which society must receive its impetus and to whose direction all forms of activity must submit. Influenced by the example of certain figures whom our historians delight in portraying as great statesmen—merely because they succeeded in imposing their personal will or views, no matter how absurd or disastrous they often were—shaped, sometimes unconsciously, by vague memories of classical Greek and Roman institutions, of the legislative systems of Lycurgus and Solon, or by equally misleading ideas drawn from works such as those of Montesquieu, Rousseau, Mably, and Raynal, they have seen civilized societies only as bodies incapable of thriving and prospering on their own. They have failed to understand that the existence and progress of societies depend primarily on individual efforts, whose principles lie within ourselves rather than in legislation or public authority. These individual efforts, made all the more powerful by Providence in order to ensure the general welfare so long as they are not thwarted by human-devised laws and so long as they exercised with greater freedom in all areas that do not infringe upon the liberty of others. Consequently, the rational mission of the legislator is not to lead men or direct their activities but to safeguard them from unjust infringements on their persons or interests, guaranteeing each individual the free use of his inherent faculties and the fruits of his labor.

This is how the populations of the northern states of the American Union understand political liberty. To them, it consists primarily in an independence of individual faculties and activities as complete as possible—that is, constrained only by the necessity for each person to respect the same rights in others. Liberty has never been understood in this way by our politicians, even those who claimed to belong to the liberal camp. They believed that liberty was sufficiently established once the legislative power, which they charged with directing society in all respects, derived its authority from the suffrage of the majority of the [xxvi] population and the fact that the rules which it imposed were common to all. As long as this power appeared to them to be the expression of the broadest general will, they did not hesitate to sacrifice individual liberty to it. Moreover, when political changes replaced the general will as the basis for legislative power with the will of a more or less restricted fraction of the population—or even that of a single man—the omnipotence of the legislator was no more contested than before.

Under the influence of such ideas—reinforced in France and in other countries that mistakenly imitate us by a universal inclination toward domination and the pursuit of public offices as means of making a living or a fortune—it was inevitable that governmental action would tend to expand continuously. Once legislators, whoever they might be, were entrusted with an unlimited mission, they inevitably had to add to the dictates and regulations necessary to make society function according to their vision. Consequently, those who have successively wielded this supreme mandate have done so so extensively that they have imposed hundreds of thousands of laws and regulations upon us over the past sixty years.

This is how our governmental and administrative system has acquired colossal proportions, unprecedented in any country in the world. It has gradually extended its reach, its regulations, and its restrictions to almost every sector of activity, stifling their development and productivity in proportion to the freedom it has curtailed. To manage the vast numbers of its duties, it has multiplied public services and positions to such an extent that a significant portion of the population now lives off tax revenues, fostering the growth of parasitic groups that seek to live the same way. This has created a dangerously subversive force and one of the primary causes of the unrest and disorder that make security so precarious in our country.

Political economy studies and analyzes all the elements of disruption contained in such a system; it exposes its harmful consequences and identifies the remedy, which consists primarily in reducing and simplifying governmental action by returning to private activity the free exercise of all branches of labor that, by their nature, fall outside the rational functions of public authority but which our governments have sought to control, monopolize, or regulate.