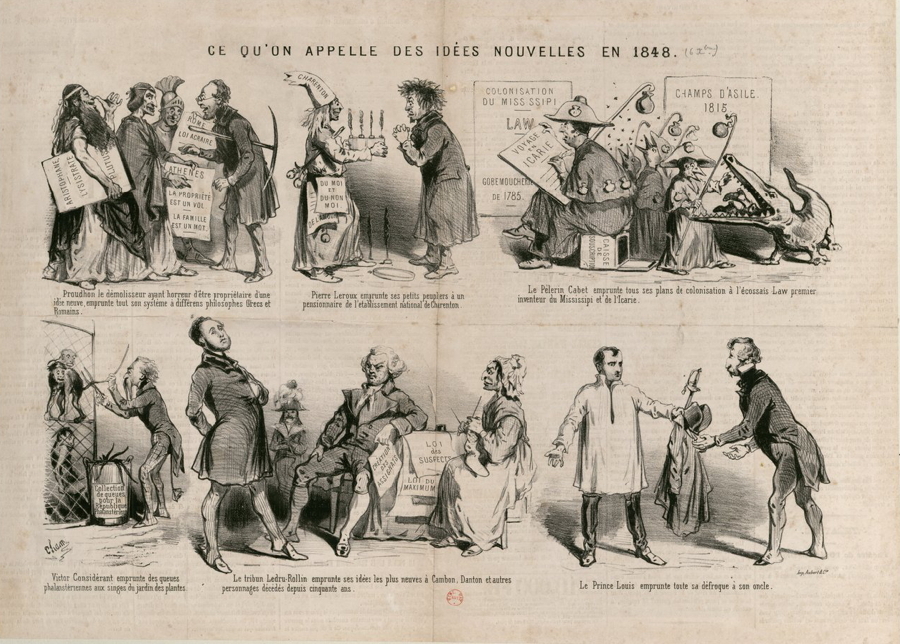

Images of Liberty and Power:

Abel Gance, "J'Accuse" [I Accuse] (1938) and

Remembrance Day 11.11.11

[Updated November 14, 2011]

|

|

Still from Gance's film "J'Accuse" (1838) of

the Soldier's Tomb before he rises from the dead |

Still from Gance's film "J'Accuse" (1838)

of the Soldier's Tomb as he rises from the dead |

Abel Gance, J'Accuse [I Accuse] (1938)

In this still from the movie we see the statue on what looks like the "Tomb of the Unknown Soldier" at Verdun coming to life in response to the calls of the embittered anti-war scientist Jean Diaz for all the fallen soldiers of the First World War to rise up and protest the outbreak of another war. Abel Gance first made the film in 1919 using 2,000 French soldiers who were on leave from the front to depict the uprising of the dead. He made a second version in 1938 when it was clear another war was soon to break out in Europe (which it did in Septmber 1939 when the Nazis invaded Poland). The message was that even though millions had died in vain fighting for State and Empire in the first war, by returning from the dead they might stop a second war in which further millions would die. A noble but furitless hope in 1938-39. [See the clips of the last 20 minutes of the film when the fallen soldiers rise up to literally frighten the people into dropping their weapons - Part 1 - Part 2 - Part 3] .

Gance's film is about a WW1 soldier Jean Diaz who fights at Verdun but survives the war and promises his fallen comrades that he will work after the war has ended to make sure there are no more wars. He becomes a scientist in the glass making industry and develops a formula for making glass which is as strong as steel which he hopes will make war less likely because of its defensive possibilities. His design is stolen by the company which wants to use it in the growing arms race against the other European powers in the late 1930s. In disgust and anger Diaz returns to Verdun to be close to his fallen comrades. Through a process not well explained in the film, he finds a map of the underground tombs and ossuaries at the Verdun memorial where nearly 700,000 men died and finds a way to communicate with the dead. He is driven mad by the experience but when he hears that the European powers have mobilized for another war he snaps out of his madness and proceeds to summon all his dead comrades from the grave. The film ends with all the dead soldiers of WW1 rising up from their graves to march in protest at the continuing war-mongering by the politicians and war manufacturers. It has quite remarkable special effects for the time with endless columns of dead soldiers marching or rather staggering about calling out to their comrades. The scenes where the statues of the fallen soldiers gradually turn into walking corpses are remarkable. These shots come from the 1919 version in which he used 2,000 extras who were French soldiers on leave from the front.

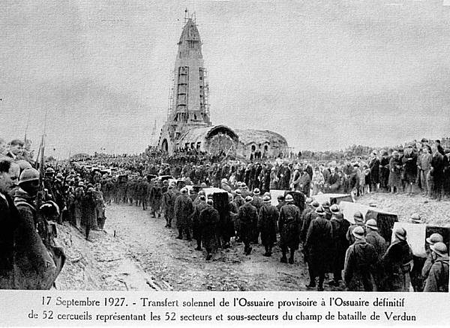

There were so many unidentifiable bodies from the Verdun battlefields that bones were collected into a makeshift "ossuary" or bone house for storage. They were later moved into a more permanent home in 1927 which was turned into a memorial.

|

|

A postcard from 1927 showing the transfer of 52

coffins from the temporary Ossuary to the nearly completed official

Ossuary. |

The Ossuary at Douaumont as it appears today [Source: Pierre's Photo Impressions of the Western Front] |

Hundreds of thousands of French and German soliders died fighting around the citadel of Verdun. Many of their bodies were either lost in the mud or completely unidentifiable. The photos below show the crypts at the Ossuary at Douaumont (near Verdun) where the bones of unknown soliders are kept. Verdun was part of the larger Battle of the Somme which raged between July and November 1916. Casualties for the Battle of the Somme are as follows: UK 350,000; Australia 23,000; total British Empire 420,000; France 204,000, Germany 465,000. Just counting the dead from the battle of the Verdun sector (January-December 1916): France 163,000; Germany 143,000.

|

|

One of the few dead soldiers who was recognized by name in a public memorial at Verdun was, typically, a French politician. The monument for André Thome is used in Gance's film (left image) to represent all of the nameless soldiers who fell in battle (Jean Diaz calls for them to rise up in French, English, as well as German) and does not refer to any of them by name exept for the men who had been in his platoon. The image on the right shows the tomb of André Thome made by Alexandre Descatoire which has a shield at his feet with the inscription "Le Soldat du Droit" (The Soldier of Justice). André Thome was a member of the French Chamber of Deputies representing the Social Democrats for the department Seine-et-Oise, thus apparently meriting him this special memorial. Perhaps some of the men who voted for him have their bones in the ossuary room above right. The inscription states in detail: "André Thome. Deputy. Second Lieutenant of the Dragoons, on his request detached to the 147th Infantry Brigade. Knight in the Legion of Honour. Croix de Guerre. Killed during the battle of Verdun on 10 March 1916 at the age of 36 Years." The special treatment received by politicians and military leaders in war memorials was singled out for criticism in the film The Americanization of Emily (1964), an extract of which can be found here.

|

|

Still from Gance's film "J'Accuse" (1838)

of the Soldier's Tomb before he rises from the dead |

The tomb of André Thome at Verdun (died 10 March,

1916) [Source: Pierre's Photo Impressions of the Western Front] |

Here is the controversial depiction of a dead soldier of unknown rank on the Royal Artillery Monument in Hyde Park, London. It was designed by Charles Sargeant Jagger and was unveiled in 1925 to commemorate the members of the Royal Regiment of Artillery who died in WW1. There are 4 statues of soldiers around the monument one of whom is shown dead, wrapped in his trench coat with his helmet resting on his chest. Sargeant defied a government ban on the depiction of dead soldiers in the war in his attempt to show the men in a more realistic light. Around the base is a patriotic quotation from Shakespeare's Henry V which says "Here was a royal fellowship of death!" [at the OLL]. This is a very strange quotation to have selected for a monument to the ordinary men in the regiment of artillery who died in the war. Henry V makes his remark about getting a report of the battle field dead after the battle of Agincourt. He only gets a list of the aristocrats and his royal relatives who died on the battle field. No mention is made of the ordinary English soldiers and archers who also died in Henry's ultimately failed attempt to expand his empire in France. Ordinary soldiers in his mind had no names and were completely expendable [Note this is the name of John Ford's very sad film about US navy men in WW2 - "They Were Expendable" (1945). The picture of the dead soldier at the Royal Artillery Monument is used in the opening shot of Joseph Losey's film "King and Country" (1964)].

|

|

The "Fellowship of Death" depicted on

the Royal Artillery Monument, Hyde Park, London. |

One of the

crypts in the Ossuary at Douaumont (Verdun) where the bones

of unknown soliders are kept. This of course is another example of

"the fellowship of death" but rather less "royal" than

Henry V had in mind. |

|

|

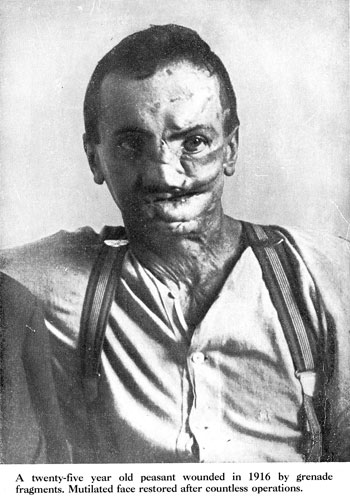

Still from Gance's film "J'Accuse" (1838)

of one of the disfigured soldiers who have risen from the dead |

One of the many shocking photos of disfigured soldiers

in the Ernst Friedrich's anti-war book War against War! (1924) |

Contrast Gance's parade of the dead and deformed and the Ossuary at Verdun with the line from Horace's poem in which he states the opposite sentiment - "dulce et decorum est pro patria mori" [It is sweet and fitting to die for the Fatherland]. One might read Horace's original poem as somewhat ironic and mocking but the sentiment was taken very seriously for generations of schoolboys who learnt Latin in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. For many young men who marched off to fight in August 1914 this was a sentiment they had absorbed at school and believed fervently. Not surprisingly it was one of the ideas which Erich Maria Remarque singled out for criticism in the novel and later film All Quiet on the Western Front (1930) [see the film clip] and which the English poet Wilfred Owen called "the old lie". Owen's bitter critique of Horace's statist slogan goes as follows [W. Owen, “Dulce et decorum est pro patria mori ” (1917)]:

If in some smothering dreams you too could pace

Behind the wagon that we flung him in,

And watch the white eyes writhing in his face,

His hanging face, like a devil's sick of sin;

If you could hear, at every jolt, the blood

Come gargling from the froth-corrupted lungs,

Obscene as cancer, bitter as the cud

Of vile, incurable sores on innocent tongues, -

My friend, you would not tell with such high zest

To children ardent for some desperate glory,

The old lie: Dulce et decorum est Pro patria mori.

|

"Gassed"(1919) by the expatriot American

painter John Singer Sargent [Source: the Imperial War Museum <http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/23722>] |

One might dismiss this patriotic nonsense of the Victorian and Edwardian eras as no longer relevant to modern society but one would be mistaken. Here is that same slogan urging the ultimate sacrifice on behalf of the state and empire engraved above the entrance to the Arlington Memorial Amphitheater in Washington, D.C. Do the people gathered underneath the entrance even know what it says or what it means? Would they care if they did?

|

|

Detail of the entrance to the Arlington Memorial

Amphitheater where is engraved Horace's line "dulce

et decorum est pro patria mori". [See a larger version of the image to read the line from Horace's poem] |

The entrance to the Arlington Memorial Amphitheater

in Washington, D.C. |

I want to end this piece with a clip from Derek Jarman's film "War Requiem" (1989) [see film guide] which is partly a story based upon Wilfred Owen and his poetry and partly a silent film set to the music of Benjamin Britten's War Requiem (1961). The segment I have here is the "Libera me" with the following words from the Latin requiem mass:

Deliver me , O Lord, from eternal death

in that awful day

when the heavens and earth shall be shaken

when Thou shallt come to judge the world by fire.I am seized with fear and trembling,

until the trial shall be at hand and the wrath to come.

The segment begins and ends with a shot of piles of skulls and the film clips in between show a selection of the killing which has taken place in the many wars of the 20th century. [7 mins 44 .m4v 226.6 MB]