Images of Liberty and Power

[Updated June 12, 2011]

10. "Hail to the Chief" [January 25, 2011] |

|

|

|

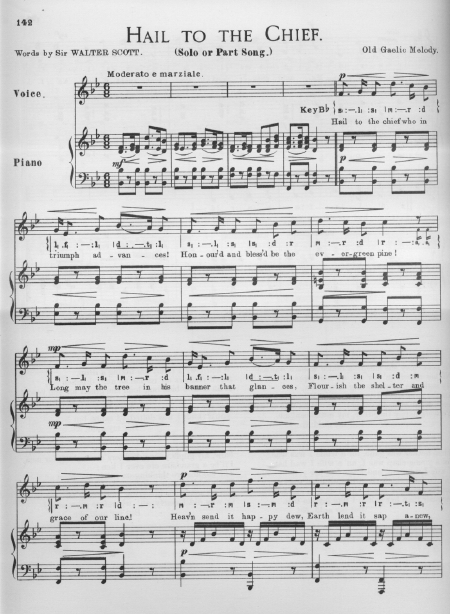

The sheet music for "Hail to the Chief"

using Sir Walter Scott's original words from the poem The Lady

of the Lake (1810) |

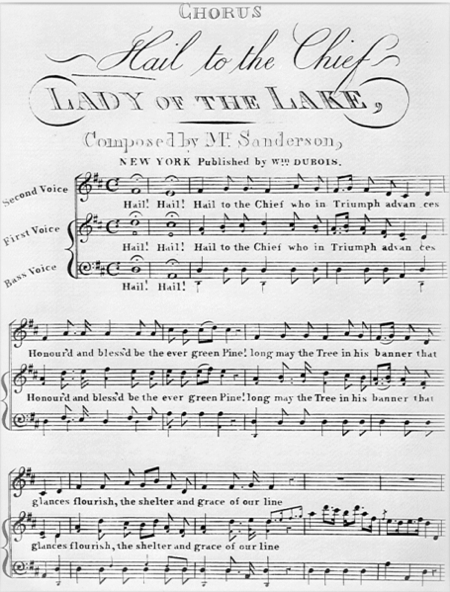

The sheet music for "Hail to the Chief,"

music by James Sanderson, words by Albert Gamse (1812) |

Observations: The song "Hail to the Chief" (1810/1812) is usually played by a military band when the president of the United States is present or enters a room. Its origins have a curious history as a ballad about a clan uprising against the Scottish King, and the militaristic sentiments expressed in the modern version are rather troubling for the inhabitants of a free society. |

|

Sir Walter Scott and The Lady of the Lake (1810)

Sir Walter Scott wrote a lengthy poem of Six Cantos each with many verses about the rivalries between 3 men and a woman, between King James V and James Douglas, and the war between the Highland Scots (the Gaelic speaking part of Scotland) (led by the clan leader Roderick Dhu) and the Lowland Scots (led by King James). "The Chief" referred to in the poem and the songs is the clan leader Roderick Dhu who is in exile because of a murder he committed at court. He is trying to organize the other clans to join him in a general uprising against the king and the lowlanders and as part of this effort he visits an island in the middle of a lake. There are two songs in Canto II (The Island) which paint an interesting picture of the warrior chief of the Clan Alpine. The first is a rather mournful song about Highlanders who travel south to "royal court" but who are haunted by memories of "the lonley isle".The second song (verse XIX) is sung as the clansmen row their Chief across the lake. They see their leader and their clan as a massive tree which provides "shelter and grace" to their people from whatever "whirlwid" or "tempest" might come their way. They then celebrate their Chief's military victories having left towns as "smoking ruins" and widows and maids "lamenting" their coming:

II.

Song.

'Not faster yonder rowers' might

Flings from their oars the spray,

Not faster yonder rippling bright,

That tracks the shallop's course in light,

Melts in the lake away,

Than men from memory erase

The benefits of former days;

Then, stranger, go! good speed the while,

Nor think again of the lonely isle.

'High place to thee in royal court,

High place in battled line,

Good hawk and hound for sylvan sport!

Where beauty sees the brave resort,

The honored meed be thine!

True be thy sword, thy friend sincere,

Thy lady constant, kind, and dear,

And lost in love's and friendship's smile

Be memory of the lonely isle!

III.

Song Continued.

'But if beneath yon southern sky

A plaided stranger roam,

Whose drooping crest and stifled sigh,

And sunken cheek and heavy eye,

Pine for his Highland home;

Then, warrior, then be thine to show

The care that soothes a wanderer's woe;

Remember then thy hap erewhile,

A stranger in the lonely isle.

'Or if on life's uncertain main

Mishap shall mar thy sail;

If faithful, wise, and brave in vain,

Woe, want, and exile thou sustain

Beneath the fickle gale;

Waste not a sigh on fortune changed,

On thankless courts, or friends estranged,

But come where kindred worth shall smile,

To greet thee in the lonely isle.'

XIX.

Hail to the Chief who in triumph advances!

Honored and blessed be the ever-green Pine!

Long may the tree, in his banner that glances,

Flourish, the shelter and grace of our line!

Heaven send it happy dew,

Earth lend it sap anew,

Gayly to bourgeon and broadly to grow,

While every Highland glen

Sends our shout back again,

'Roderigh Vich Alpine dhu, ho! ieroe!'

Ours is no sapling, chance-sown by the fountain,

Blooming at Beltane, in winter to fade;

When the whirlwind has stripped every leaf on the mountain,

The more shall Clan-Alpine exult in her shade.

Moored in the rifted rock,

Proof to the tempest's shock,

Firmer he roots him the ruder it blow;

Menteith and Breadalbane, then,

Echo his praise again,

'Roderigh Vich Alpine dhu, ho! ieroe!'

XX.

Proudly our pibroch has thrilled in Glen Fruin,

And Bannochar's groans to our slogan replied;

Glen Luss and Ross-dhu, they are smoking in ruin,

And the best of Loch Lomond lie dead on her side.

Widow and Saxon maid

Long shall lament our raid,

Think of Clan-Alpine with fear and with woe;

Lennox and Leven-glen

Shake when they hear again,

'Roderigh Vich Alpine dhu, ho! ieroe!'

Row, vassals, row, for the pride of the Highlands!

Stretch to your oars for the ever-green Pine!

O that the rosebud that graces yon islands

Were wreathed in a garland around him to twine!

O that some seedling gem,

Worthy such noble stem,

Honored and blessed in their shadow might grow!

Loud should Clan-Alpine then

Ring from her deepmost glen,

Roderigh Vich Alpine dhu, ho! ieroe!'

In Canto V (The Combat) we get some idea of what drives the clan Chief Roderick Dhu to rebel against King James V and the lowlanders. At night King James is travelling incognito (as James Fitz-James) and meets a mountaineer warrior by his campfire. In their conversation Scott provides us with list of grievances the clans have against the King (the Gaels are the Gaelic speaking Highlanders and the Saxons are the lowlanders, also disparragingly referred to as "Sassenachs"). The main grievance is the dispossession of the clansmen's traditional lands by the invaders: "Were once the birthright of the Gael; The stranger came with iron hand, And from our fathers reft the land":

VI.

Wrathful at such arraignment foul,

Dark lowered the clansman's sable scowl.

A space he paused, then sternly said,

'And heardst thou why he drew his blade?

Heardst thou that shameful word and blow

Brought Roderick's vengeance on his foe?

What recked the Chieftain if he stood

On Highland heath or Holy-Rood?

He rights such wrong where it is given,

If it were in the court of heaven.'

'Still was it outrage;—yet, 'tis true,

Not then claimed sovereignty his due;

While Albany with feeble hand

Held borrowed truncheon of command,

The young King, mewed in Stirling tower,

Was stranger to respect and power.

But then, thy Chieftain's robber life!—

Winning mean prey by causeless strife,

Wrenching from ruined Lowland swain

His herds and harvest reared in vain,—

Methinks a soul like thine should scorn

The spoils from such foul foray borne.'

VII.

The Gael beheld him grim the while,

And answered with disdainful smile:

'Saxon, from yonder mountain high,

I marked thee send delighted eye

Far to the south and east, where lay,

Extended in succession gay,

Deep waving fields and pastures green,

With gentle slopes and groves between:—

These fertile plains, that softened vale,

Were once the birthright of the Gael;

The stranger came with iron hand,

And from our fathers reft the land.

Where dwell we now? See, rudely swell

Crag over crag, and fell o'er fell.

Ask we this savage hill we tread

For fattened steer or household bread,

Ask we for flocks these shingles dry,

And well the mountain might reply,—

"To you, as to your sires of yore,

Belong the target and claymore!

I give you shelter in my breast,

Your own good blades must win the rest."

Pent in this fortress of the North,

Think'st thou we will not sally forth,

To spoil the spoiler as we may,

And from the robber rend the prey?

Ay, by my soul!—While on yon plain

The Saxon rears one shock of grain,

While of ten thousand herds there strays

But one along yon river's maze,—

The Gael, of plain and river heir,

Shall with strong hand redeem his share.

Where live the mountain Chiefs who hold

That plundering Lowland field and fold

Is aught but retribution true?

Seek other cause 'gainst Roderick Dhu.'

The Adaptation of Scott's poem to serve the needs of the president of the United States

After the publication of Scott's poem in 1810 it was quickly adapted for the stage and performed in the U.S. as early as 1812. The music was written by James Sanderson and the words by Albert Gamse. Although the words are no longer sung they are worth examining:

Hail to the Chief we have chosen for the nation,

Hail to the Chief! We salute him, one and all.

Hail to the Chief, as we pledge cooperation

In proud fulfillment of a great, noble call.Yours is the aim to make this grand country grander,

This you will do, that's our strong, firm belief.

Hail to the one we selected as commander,

Hail to the President! Hail to the Chief!

What is most notable at first reading is the obvious militry references to the President as "chief" and "commander" whom we must "salute" unanimously ("one and all"). There is no mention about upholding the Constitution or carrying out duly enacted laws. Instead there is a "pledge" to "make this grand country grander", which could mean economically bigger and better, but this seems unlikely as it is expressed in the context of "hailing" the president as "commander" in chief of the armed forces (the word "grander" is deliberately chosen in order to rhyme with "commander"). The fact that the music is played now almost exclusively by military bands reinforces this "militaristic" reading of the song.

Its first use to honour an American president occurred in 1815 when a combined celebration of ex-president George Washington and the victory of the US in the War of 1812 against Britain. The author of the Library of Congress Performing Arts Encyclopedia entry on "Hail to the Chief" notes the appropriateness of this song at that time:

The poem's "Chief" was the Scottish folk hero Roderick Dhu, who strove to protect the Douglas clan from their enemy, King James V, but died at the monarch's hand. The story apparently had a particular resonance in America during the War of 1812 because it explored conflicting values while acknowledging both the good and the bad aspects of each contending system.

This seems a little simplistic as the clans under Roderick do have legitimate

grievances against the invading monarchy which has dispossessed them of their

ancestral lands ("These fertile plains, that softened vale,

Were once the birthright of the Gael; The stranger came with iron hand, And from

our fathers reft the land"), but the poem also tells us

that the clans were war-like and not shy to rape, murder, and plunder when they

had the chance ("Glen Luss and Ross-dhu, they are smoking in ruin, And the best

of Loch Lomond lie dead on her side"). I'm not sure

this aspect of the original poem is what the patriots had in mind in 1815 when

the song was used in the official celebration of the victory against the Brits

in 1812. If the Americans had wanted to associate themselves with an heroic

struggle against a monarch they might have chosen a better historical example

than the Scottish clans' uprising which

was sullied with hints of atrocities against civilians ("Widow

and Saxon maid Long shall lament our raid").

The song's first use to honour a living President was on January 9, 1829 when Andrew Jackson assumed office. Given Andrew Jackson's role as military governor of Florida and in the ethnic cleansing of the Indian tribes (Indian "Removal") which took place during his administration perhaps the choice of a song based upon stories of violent marauding highland clans is a fitting one. The unintended irony is that the "Chief" celebrated in the original poem, the Highlander Roderick Dhu whose people had been dispossessed by the Lowlander Saxons, had more in common with the dispossessed and "removed" Indians of Jackson's day than he does with President Jackson who carried out these policies. Tecumsah or the leaders of the Seminole or Cherokee tribes would have identified quite strongly with the Highland clan "Chief" in Scott's poem and his strategy of marauding the Lowlands for revenge against the invaders ("Pent in this fortress of the North, Think'st thou we will not sally forth, To spoil the spoiler as we may, And from the robber rend the prey?"). So it is of them that I prefer to think whenever I hear this tune played, not the striding American President surrounded by his acolytes and admirers. No doubt by 1829 the memory of Scott's poem from which the original words were taken would have long faded away and the new words (if they were sung) would have been to the fore in peoples' minds. The new words of the song seem almost designed for someone like Andrew Jackson.

It also seems quite fitting that "Hail to the Chief" became the official musical tribute to the American President when it was authorised as such by the Department of Defense in 1954 at the height of the Cold War. Now that the Cold War is over and ethnic cleansing is no longer the stated policy of the U.S. Government, perhaps a new song to welcome the President into a room is called for. Or pehaps no song at all...