“THE PROSPECTS FOR LIBERTY: SOME THOUGHTS ON GOALS, THREATS, AND STRATEGIES”

By David M. Hart

[Created: August, 2022]

[Revised: 11 July, 2024] |

Table of Contents

- Overview

- I. The Current State of the Liberty Movement

- II. We need to be clear about what our ultimate Goal is

- III. The Threats which Confront the Liberty Movement

- IV. The Task ahead

- V. Looking for the “Golden Thread” to unravel justifications for State Intervention

- VI. Choosing the Right Kind of Arguments to use

- VII. Where we are now and what we need to do next

- VIII. Conclusion: Stressing the benefits of liberty and the harms of state coercion

- Endnotes

- Bibliography

Overview↩

1.) We need to be realistic about the massive task ahead of us, but not become despondent and depressed. I have identified 16 significant threats to liberty (some longstanding and others more recent) which need to be addressed both intellectually and politically.

2.) We need to be careful how we manage our limited resources (money and people) and thus need to coordinate our activities with others in the Liberty movement

3.) We need to focus on the weakest points in the ideas and arguments used to justify state intervention and regulation, which I believe are the following:

- that the use of coercion is immoral , even if done by the state and its agents

- that the extent of “market failure” is exaggerated and misunderstood, and that if/when markets do “fail” it is because they either weren’t allowed to exist or were hampered by state regulation if they did

- that people do not appreciate the extent of and causes of “government failure” which is extensive and inevitable

- that there is massive public ignorance of many key economic insights which makes points 2 and 3 above possible

4.) We need to appreciate the fact that different people (and different cultures) react differently to the kinds of arguments we use to defend liberty and criticise state intervention and regulation, thus we need to have a range of arguments and use them appropriately according to the audience. These arguments are:

- moral arguments which appeal to justice and a moral theory concerning property rights, individual liberty, and the nature of political power (coercion)

- economic arguments which appeal to notions of economic efficiency and the greater productivity of free markets

- political arguments about the dangers posed by political power and the need to limit it, and how best to organise the political system in order to enable the state to undertake properly its legitimate functions

- historical arguments concerning the evolution and expansion of state power over the past century, the nature and causes of government failure, the nature and causes of market failure, the struggle for liberty in previous centuries (the “Great Emancipation), and the vast improvement in the human condition brought about by free market “capitalism” (the “Great Enrichment”)

5.) We need to understand that we are currently living in a “hybrid system” where there are still considerable (legacy) freedoms which we enjoy and which make possible our high standards of living, but also that there is and has been over decades considerable increases in the power of the state which impedes the enjoyment of these liberties and the growth of prosperity. Thus the problem we face is twofold, how to protect (and even expand) the liberties we currently enjoy and at the same time, how do we reduce the power of the state which hampers or even destroys these liberties and opportunities for wealth creation.

6.) We have to understand that the earlier movements for emancipation and enrichment were built upon a widespread acceptance of liberal ideas and values which to a large degree have disappeared today. If we wish to return to the path of liberty and wealth creation we will need to re-establish this intellectual and moral foundation.

7.) We need to understand that, in the absence of a widespread belief in liberty, when crises occur periodically the state and its supporters use this as an opportunity to increase their power, which over the course of the 20th century has never been relinquished but continues to expand. Such crises are often “tipping points” when people are forced to question their existing beliefs and policies and look for new solutions to their problems. Statists have been able to take advantage of these tipping points to further their own agenda, those in the Liberty movement have not been able to do the same thing.

8.) We have to appreciate the fact that there is considerable inertia at both the individual and institutional level which is extremely hard to overcome. Individuals very rarely change their views once they enter adulthood and become set in their ways. Individuals in an institutional setting have powerful vested interests (power, influence, income) which they will protect vigorously and sometimes violently if they are challenged.

9.) We need to keep stressing over and over again the extraordinary benefits which liberty provides for both individuals and the communities in which they live; and contrast these with the very considerable harms which government coercion and intervention imposes on wealth creation, individual liberty, and human happiness.

I. The Current State of the Liberty Movement↩

The Need for Periodic Reassessments of the State of Liberty

Periodically, the defenders of liberty have taken a step back to assess “the prospects of liberty” in the light of the then current threats to it. This is usually done when those prospects seem rather bleak. I have in mind in particular Herbert Spencer’s warnings in the 1880s about the “coming slavery” posed by the emerging “legislative state” (or what we now call the “administrative state”), Friedrich Hayek in the 1940s on the threat posed by authoritarian governments and central planning of the economy, Murray Rothbard in the 1960s and 1970s on the expansion of the welfare/warfare state, John Blundell in 2001 on the issues facing liberty entering the new millennium, and my own work in the 2010s and more recently on a whole raft of new and rising threats to liberty. See for example the following:

- Herbert Spencer, “Political Retrospect and Prospect” (1882) and “The Coming Slavery” (1884)

- Friedrich A. Hayek, The Road to Serfdom (1944) and “The Intellectuals and Socialism” (1949)

- Murray N. Rothbard, “Left and Right: The Prospect for Liberty” (1965) and “A Strategy for Liberty” (1973)

- John Blundell, Waging the War of Ideas (2001)

- David M. Hart, "On the Spread of (Classical) Liberal Ideas: Some Thoughts on Strategy” (2015), "Entrepreneurs, Investors, and Scribblers: An Austrian Analysis of the Structure of Production and Distribution of Ideas" (2015), and "The State of the Libertarian Movement after 50 Years (1970-2020): Some Observations” (2021); and many blog posts I wrote during 2022 “On the Current State of Liberty and the Threats it faces” (5 July, 2022) http://davidmhart.com/wordpress/archives/1499

We also need to consider the considerable efforts following the end of the Second World War to build organisations to defend liberty and oppose the expansion of state power. This was a reaction on the one hand to the growth in the state as result of “war planning” during WW2 and its persistence afterwards, the rise of the welfare state in post-war Europe and elsewhere, and the demands of the new “Cold War” between the nuclear superpowers; and on the other hand to the parlous state of the Liberty movement. I have in mind the following individuals and organisations:

- Leonard Reed and the Foundation for Economic Education founded in 1946

- Friedrich Hayek, Milton Friedman, et al. and the Mont Pèlerin Society founded in 1947

- Harold Luhnow and the William Volker Fund after 1947 (wound up in 1964)

- Anthony Fisher and the Institute for Economic Affairs founded in 1955

- Pierre F. Goodrich and Liberty Fund in 1960

- F.A. Harper and the Institute for Humane Studies in 1961

- and more recently, another body created by Anthony Fisher in 1981, the Atlas Economic Research Foundation (now called the Atlas Network).

This position paper needs to be viewed in the light of these previous efforts to assess “the prospects for liberty” and the bodies created in the post-WW2 period to spread classical liberal (henceforth “CL”) ideas and to influence the direction of government policies.

The “Big Problems” Classical Liberals face Today

To summarize what I believe are the very significant problems CLs face I would argue the following, that:

- there has been a collapse, even failure, of the Liberty movement in the 20th and early 21st centuries

- “Classical” liberalism in the Centre-Right political parties is dead and has been replaced by an “interventionist” form of “neo-liberalism”

- the rise of the modern warfare / welfare / regulatory / surveillance state is unprecedented and seemingly unstoppable

- the growth of a “dependent class” from below and a “privileged class” from above makes reform in a democracy very difficult

- there is the old but still ongoing problem of creating a “limited government” to protect life, liberty, and property, and keeping it limited to just these functions

In addition to these five large and general problems CLs also face many more specific individual threats to liberty, some of which have been present since the end of the 19th century, and some of which have emerged and strengthened over the past 20 years or so. I will address these more specific threats later in the paper , but just list them here for consideration.

Long-standing and on-going threats to liberty

Some of the serious threats to liberty which were identified during the 1940s, 1950s, and 1960s by the first generation of modern CL reformers are still with us today. These long-standing and on-going threats to liberty include:

- the general policy of government intervention in the economy (“interventionism”)

- the rivalry (“cold war”) between the major nuclear powers and the threat of MAD (mutual assured destruction)

- military intervention and support for right-wing dictatorships in order to “contain” or “roll-back” “communism”

- the growth and then expansion of the welfare state

- the close relationship between some large corporations and financial groups who seek and get special (legal) privileges, subsidies and bailouts, and protected markets

- inflation and the expansion of the money supply by government monopoly Central Banks

- the expansion of state-funded schools and universities and their staffing by pro-state interventionists (the “Left”)

- the expansion of the regulatory state into almost all areas of human activity

New threats to Liberty over the past 20 Years

I would also add the following list of new threats to liberty which have emerged over the past two decades, especially as a result of the attacks of 9/11 2001, the global economic crisis of 2008-9, and the Covid lockdowns of 2020-22:

- the rise of the “surveillance state” after 9/11

- the use of ”quantitative easing” and near zero interest rates, the government bailout of the banks and large investment firms

- “liberal interventionism” in foreign policy

- the rise of a radical “Green” environmentalist movement

- the rise of “neo-protectionism” and “national” industrial policy

- the resurgence of explicit interest in and support for “socialism” especially by young people

- the emergence of the “Lockdown State” and “Hygiene Socialism”

- the continued domination of the universities and schools by pro-interventionist Keynesian economists and “leftist” intellectuals

II. We need to be clear about what our ultimate Goal is↩

Introduction

Before I turn to discussing in more detail the above mentioned problems and threats facing the Liberty movement and the strategies we might adopt in order to confront them, I think we need to be clear about what we think our ultimate goal is, and the lesser goals (short-term, medium-term, and longer-term goals) we need to achieve in order to reach this ultimate goal.

The Ultimate Goal is Liberty

I think most of us would say that our ultimate goal is “liberty”, but what kinds of liberty, and how much liberty, are questions which have divided the Liberty movement from its earliest days and continue to do so today. I cannot go into much detail about this issue here, but will limit my remarks to a brief summary of what I have said elsewhere, especially on my blogs “Reflection on Liberty and Power” http://davidmhart.com/wordpress/. [1]

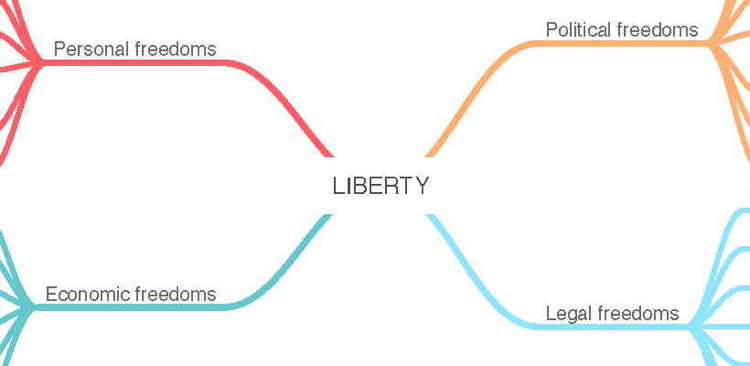

I have argued that liberty is “multi-dimensional” in nature, consisting of four major “clusters” or “bundles” of freedoms, which when taken together constitute “Liberty.” [2] This was the view of Frédéric Bastiat and it is one that I share. Here is his articulation of this key notion from his pamphlet on “The Law” (June 1850) where states “la Liberté … est l’ensemble de toutes les libertés” (Liberty is the collection (or sum) of all the different kinds of liberty) and then lists those individual liberties. The full passage is worth quoting: [3]

| Et qu’est-ce que la Liberté, ce mot qui a la puissance de faire battre tous les cœurs et d’agiter le monde, si ce n’est l’ensemble de toutes les libertés, liberté de conscience, d’enseignement, d’association, de presse, de locomotion, de travail, d’échange ; d’autres termes, le franc exercice, pour tous, de toutes les facultés inoffensives ; en d’autres termes encore, la destruction de tous les despotismes, même le despotisme légal, et la réduction de la Loi à sa seule attribution rationnelle, qui est de régulariser le Droit individuel de légitime défense ou de réprimer l’injustice. | And what is liberty, this word that has the power of making all hearts beat faster and causing agitation around the world, if it is not the sum of all freedoms: freedom of conscience, teaching, and association; freedom of the press; freedom to travel, work, and trade; in other words, the free exercise of all inoffensive faculties by all men and, in still other terms, the destruction of all despotic regimes, even legal despotism, and the reduction of the law to its sole rational attribution, which is to regulate the individual law of legitimate defense or to punish injustice. |

Thus according to this view, Liberty is made up of personal freedoms, economic freedoms, political freedoms, and legal freedoms.

Historically, liberalism has been divided into what I call “radical” liberals, “moderate” liberals, and “new” liberals (today called “neo” liberals) each of which have a different view of how many of these “bundles” of freedom are needed (or will be accepted) in a “free society”. Thus, modern libertarians believe that a truly free society would have all four of these bundles of freedom, while modern “liberals” would only permit a much more limited number of freedoms and place considerable restrictions on many economic freedoms. Conversely, the Singaporean state allows considerable economic freedoms but imposes significant restrictions on political and personal freedoms.

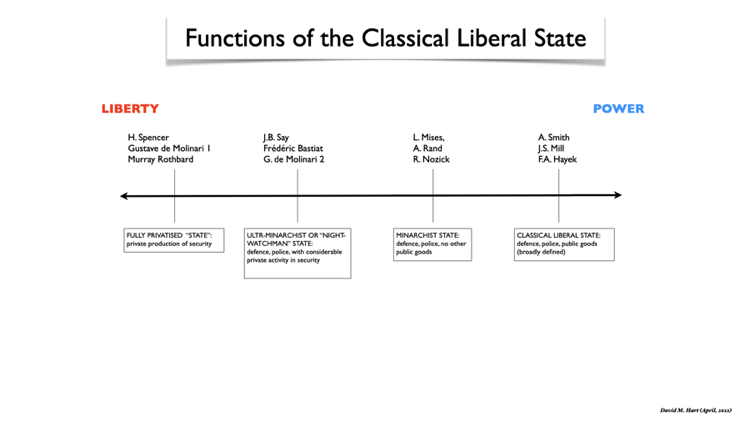

How limited do we want the Government to be in order to achieve this ultimate goal?

Depending on how much liberty a society desires and will accept, the government of that society will be more or less “limited” in the scope of its powers. This is a matter which has also divided CLs historically and still divides them today. The following “spectrum” of the “classical liberal” state, the “minarchist” state, the “ultra-minarchist” or “nightwatchman” state, and the “fully-voluntary” state, shows this division in graphical form. The modern (neo) “liberal” position would be off the chart to the right of the “Power” end of the spectrum:

In the short and medium terms all Liberty supporters no matter what their view of what the ultimate powers of the state should be, need to join forces in the present in order to oppose the common threat we can all agree upon, namely the excessive and dangerous power of the modern interventionist state. Only later, in the longer term, will those in the Liberty movement need to argue about how limited the powers of the state should in fact be. That is a debate we will have to have at the appropriate moment sometime in perhaps the far future.

The Intermediate Steps we need to take on the Road to this Ultimate Goal

If our very long term or the “ultimate goal” is “liberty” (however we may define it), then there are several intermediate steps we have to take in order to reach this final goal. These may be defined as short-term (2-3 years), medium-term (5-10 years), and longer-term (15-40 years) goals or steps which we believe will take us to the end of the road. One form these intermediate goals might take are the following:

- short term: to slow the growing power of the state and the steady loss of our liberties

- medium term: to stop the state increasing its power and entrenching any further upon our liberties, and to begin the slow hard task of reducing the power of the state over our lives

- longer term: to reverse the direction of the past 100 years and to reduce in a substantial way the power of the state and thus begin restoring to us some (perhaps all) of our lost liberties

- even longer term: to create a truly free society with very strict limits on the power of the state in order to prevent it from starting this process all over again

Some questions about goals we need to ask ourselves at this point in time are:

- what intermediate goals are realistically achievable given our current restraints of time, money, people, and other resources?

- what can we hope to achieve in a small country like Australia?

- is Australia a “trend-setter” or a “trend-follower”?

Some first thoughts on strategy to achieve these goals

I want to introduce here a brief comment on a matter which will be taken up in more detail below, namely the connection between the ideas people hold and the actions they take to pursue their personal interests and their “life choices”, as well as societal interests and ends (public policy).

If you believe that the ideas people hold determine how they act, either individually or in society, in order to further their own interests and pursue their goals, then it follows that, if you can change their ideas, you will in turn change the kind of actions they will take and the choices they will make. Thus, “Ideas Matter” and we need to change the way people think before we can change society or politics.

If on the other hand you believe that political power and who wields it matters more than the ideas people hold, then the most important thing to do in order to change the direction of society and politics is to make sure you get hold of the levers of power and wield them in the “right” direction. Then “ideas don’t matter” so much. Perhaps the most generous (pro-liberty) interpretation of this approach is that, if the “right people” with the “right ideas” get into power they can change the direction in which society is heading and perhaps then as a result, change the way people think and behave. This was the approach taken by followers of Jeremy Bentham in the late 19th century in Britain and Australia, namely that “utilitarian-minded” reformers in the bureaucracy and in politics should use the power of the state to reform society in a liberal direction.

Side note: The power and influence of Bentham’s ideas in Australia in the colonial period among “liberals” of the day should not be underestimated; nor should its continuing influence within “liberalism” and “social democracy” today. This is one of several damaging turning points for liberty in Australia’s history, that Australian “liberals” adopted Bentham’s and not Herbert Spencer’s ideas. Another one would be the victory by the protectionist groups over the free traders at the time of Federation and in the decades following.

CLs need to think about what they think should come first. Should they spend their precious resources trying to change the way people think first and THEN try to change the direction of public policy? Or should they do the reverse, try to get into politics, seize the reins of power, and charge the direction of policy FROM THE TOP DOWN, and only THEN hope this will change the way people think?

III. The Threats which Confront the Liberty Movement↩

The “Big Problems” Classical Liberals face Today

I believe there are several very significant problems which CLs face, namely that:

- there has been a collapse, even failure, of the Liberty movement in the 20th and 21st centuries

- “Classical” liberalism in the Centre-Right political parties is dead and has been replaced by an “interventionist” form of “neo-liberalism”

- the rise of the modern warfare / welfare / regulatory / surveillance state is unprecedented and seemingly unstoppable

- the growth of a “dependent class” from below and a “privileged class” from above makes reform in a democracy very difficult

- there is the old but still ongoing problem of creating a “limited government” to protect life, liberty, and property, and keeping it limited to just these functions

I now wish to examine each of the above general problems in some more detail.

1.) There has been a collapse, even failure, of the Liberty movement in the 20th and 21st centuries.

There was a collapse, even failure, of the Liberty movement in the first half of the 20th century both ideologically and politically, which was followed by a weak revival in the second half of the 20th century which has since petered out. The pinnacle of this “revival” may have been the recognition of the importance of free market ideas in the 1970s (the award of the Nobel Prize for economics to Friedrich Hayek in 1974 and the coming to power of Margaret Thatcher in the UK and Ronald Reagan in the USA during the 1980s which saw a brief “flattening of the curve” of the growth in government spending. This period was only temporary before the growth of the state began again. (See my blog post on “The State of the Libertarian Movement after 50 Years (1970-2020): Some Observations” Reflection on Liberty and Power (25 March, 2021) http://davidmhart.com/wordpress/archives/1011.)

2.) “Classical” liberalism in the Centre-Right political parties is dead

“Classical” liberalism in the Centre-Right political parties is dead, or nearly dead. On the “right” the so-called “neo-liberals” which emerged out of the Mont Pèlerin Society (1947) made peace with the welfare state and extensive government regulation of the economy (opposed vigorously at the time by Ludwig von Mises) and as a result have have become “no-liberals” at all, or what I call LINOs (liberal in name only). (See my blog post on the “Linoleum Party” (LINO): “The Incoherence and Contradictions inherent in Modern Liberal Parties (and one in particular)” (21 Oct. 2021) http://davidmhart.com/wordpress/archives/1231 .)

The great Austrian economist Ludwig von Mises saw this problem very clearly as early as 1927 in his statement of the “true liberal” position, in comparison to what he called “diesel Pseudoliberalen”, or “pseudo-liberal” position: [4]

| Nahezu alle, die sich heute liberal nennen, lehnen es ab, sich zum Sondereigentum an den Produktionsmitteln zu bekennen und befürworten teils sozialistische, teils interventionistische Maßnahmen. Sie glauben dies damit rechtfertigen zu können, daß sie die Behauptung aufstellen, daß das Wesen des Liberalismus nicht in dem Festhalten an dem Sondereigentum an den Produktionsmitteln, sondern in anderen Dingen liege, und daß diese anderen Dinge eine Fortentwicklung des Liberalismus in dem Sinne verlangen, daß er heute sich nicht mehr für das Sondereigentum, sondern entweder für Sozialismus oder für Interventionismus aussprechen müsse. | Almost all who call themselves "liberals" today decline to profess themselves in favor of private ownership of the means of production and advocate measures partly socialist and partly interventionist. They seek to justify this on the ground that the essence of liberalism does not consist in adherence to the institution of private property, but in other things, and that these other things demand a further development of liberalism, so that it must today no longer advocate private ownership of the means of production but instead either socialism or interventionism. |

| Was diese anderen Dinge sein sollen, das mitzuteilen bleiben uns allerdings diese Pseudoliberalen schuldig. Wir hören mancherlei von Humanität, von Edelsinn, von wahrer Freiheit u. dgl. Das sind gewiß sehr schöne Worte, und jedermann wird sie gerne unterschreiben. Und in der Tat, jede Ideologie unterschreibt sie auch. Jede Ideologie -- von einigen zynischen Richtungen abgesehen -- glaubt, daß sie für Humanität, Edelsinn, wahre Freiheit u. dgl. eintritt. | As to just what these "other things" might be, these pseudo liberals have yet to enlighten us. We hear much about humanity, magnanimity, real freedom, etc. These are certainly very fine and noble sentiments, and everyone will readily subscribe to them. And, in fact, every ideology does subscribe to them. Every ideology — aside from a few cynical schools of thought — believes that it is championing humanity, magnanimity, real freedom, etc. |

| Das, was die Gesellschaftsideologien unterscheidet, ist nicht dieses Endziel allgemeiner Menschenund Weltbeglückung, sondern der Weg, auf dem sie ihr Ziel erreichen wollen. Für den Liberalismus ist eben charakteristisch, daß der Weg, den er wählt, der des Sondereigentums an den Produktionsmitteln ist. | What distinguishes one social doctrine from another is not the ultimate goal of universal human happiness, which they all aim at, but the way by which they seek to attain this end. The characteristic feature of liberalism is that it proposes to reach it by way of private ownership of the means of production. |

On the “left”, following in the footsteps of the once “Marxist” Social Democratic Party of Germany, modern post-war German social democrats made peace with some aspects of the free market, abandoned the idea of full “central planning” of the economy, and adopted in their Godesberger Program of 1959 the principle of “free markets wherever possible and as much government planning as necessary”. “Real” socialists at the time denounced the new social democrats as “SINOs” (socialist in name only), just as modern day “real” or “radical” liberals denounce LINOs, and for much the same reasons (ideological contradictions and inconsistency).

The relevant sections of the Godesberger Program are the following (with the key passage in bold): [5]

| Der moderne Staat beeinflußt die Wirtschaft stetig durch seine Entscheidungen über Steuern und Finanzen, über das Geld- und Kreditwesen, seine Zoll-, Handels-, Sozial- und Preispolitik, seine öffentlichen Aufträge sowie die Landwirtschafts- und Wohnbaupolitik. Mehr als ein Drittel des Sozialprodukts geht auf diese Weise durch die öffentliche Hand. Es ist also nicht die Frage, ob in der Wirtschaft Disposition und Planung zweckmäßig sind, sondern wer diese Disposition trifft und zu wessen Gunsten sie wirkt. Dieser Verantwortung für den Wirtschaftsablauf kann sich der Staat nicht entziehen. Er ist verantwortlich für eine vorausschauende Konjunkturpolitik und soll sich im wesentlichen auf Methoden der mittelbaren Beeinflussung der Wirtschaft beschränken. | The modern state exerts a constant influence on the economy through its policies on taxation, finance, currency and credits, customs, trade, social services, prices and public contracts as well as agriculture and housing. More than a third of the national income passes through the hands of the government. The question is therefore not whether measures of economic planning and control serve a purpose, but rather who should apply these measures and for whose benefit. The state cannot shirk its responsibility for the course the economy takes. It is responsible for securing a forward-looking policy with regard to business cycles and should restrict itself to influencing the economy mainly by indirect means. |

| Freie Konsumwahl und freie Arbeitsplatzwahl sind entscheidende Grundlagen, freier Wettbewerb und freie Unternehmerinitiative sind wichtige Elemente sozialdemokratischer Wirtschaftspolitik. Die Autonomie der Arbeitnehmer- und Arbeitgeberverbände beim Abschluß von Tarifverträgen ist ein wesentlicher Bestandteil freiheitlicher Ordnung. Totalitäre Zwangswirtschaft zerstört die Freiheit. Deshalb bejaht die Sozialdemokratische Partei den freien Markt, wo immer wirklich Wettbewerb herrscht. Wo aber Märkte unter die Vorherrschaft von einzelnen oder von Gruppen geraten, bedarf es vielfältiger Maßnahmen, um die Freiheit in der Wirtschaft zu erhalten. Wettbewerb soweit wie möglich Planung soweit wie nötig! | Free choice of consumer goods and services, free choice of working place, freedom for employers to exercise their initiative as well as free competition are essential conditions of a Social Democratic economic policy. The autonomy of trade unions and employers’ associations in collective bargaining is an important feature of a free society. Totalitarian control of the economy destroys freedom. The Social Democratic Party therefore favours a free market wherever free competition really exists. Where a market is dominated by individuals or groups, however, all manner of steps must be taken to protect freedom in the economic sphere. As much competition as possible – as much planning as necessary. |

It is hard to see where the modern Australian Liberal or Labor Parties would disagree in this statement. Thus from the “right” as well as from the “left” there has been a steady convergence ideologically and politically on a version of German “social democracy” in Europe and on late 19thC English Fabian Socialism in the English-speaking world. This is true for the centre parties such as Labor and Liberal in Australia, and Labour and Conservative in the UK. Thus, it would not be wrong to say that “we are all social democrats now”, and that liberalism, at least in its limited government pro-free market form, no longer exists in any of the mainstream political parties.

Nevertheless, the CL flag is still being waved by a couple of very small and still insignificant parties such as the Libertarian Party in the US and the Liberal Democrats in Australia.

3.) The rise of the modern warfare / welfare / regulatory / surveillance state is unprecedented and seemingly unstoppable

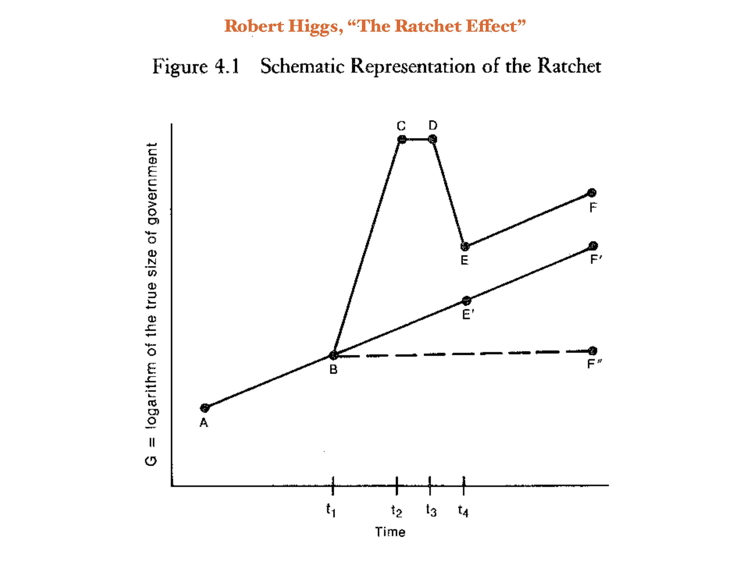

The American economic historian Robert Higgs has argued that the periodic crises which afflict our society (usually caused by state interventions in the economy, like recessions and depressions, or the outbreak of war, which is also the result of state activity vis-à-vis other states) has resulted during the 20th century in a “ratchet” effect , whereby the state increases its power during the crisis, relaxes those controls a bit at the end of the crisis, but retains some of the increase in its power until the next crisis, when the “ratchet effect” is experienced again. [6]

The net result over decades is the steady and seemingly irreversible expansion in state power and scope. His pessimistic conclusion is that, in the absence of any strong countervailing ideological opposition to this expansion, it will continue indefinitely or until a catastrophic economic breakdown takes place.

4.) The growth of a “dependent class” from below and a “privileged class” from above makes reform in a democracy very difficult

So many people have become dependent on, or beneficiaries of, the modern state that the return to Liberty is a very difficult, perhaps impossible task. What happens in a democracy when the majority of the voters are dependent on government handouts, contracts, special favors and privileges for their survival? What incentive do they have to vote against the hand that feeds them?

5.) The ongoing problem of creating a “Limited Government” and keeping it limited

There are serious practical and political problems in creating a “limited government” (which protects the citizens’s rights to life, liberty, and property) in the first place, and then keeping this government truly “limited” over time.

For a couple of centuries CLs have struggled with the problem of how to turn a big “predatory” State into a limited “protective” State? One option has been to use violence in the form of a revolution (the American, French, and 1848 Revolutions in Europe in 1848) or mass, popular protests and acts of civil disobedience in which violence may be threatened if not actually resorted to. The other option is to use peaceful reform such as non-violent protests (the movement against the protectionist Corn Laws in England), and a CL political party (such as the Liberal Party in late 19th century Britain.

If and when one is able to create a limited government (one with constitutionally protected liberties for the people and strict limits and restraints on the power the state and its agents) the problem then inevitably arises of how to keep this limited state “limited”? This seems to an intractable problem given, on the one hand, the demands on the government by the electorate, lobby groups, rent-seekers for favors, privileges, and benefits, and on the other hand, given the ambitious and self-interested behaviour of politicians and bureaucrats for greater power, prestige, and income.

These two problems have yet to be adequately solved by CLs.

Long-standing and on-going threats to liberty

Some of the serious threats to liberty which were identified during the 1940s, 1950s, and 1960s by the first generation of modern CL reforms are still with us today, which says something about how difficult it is to shift opinion (both public and academic) and to reverse or even slow down the ever increasing expansion of the power of the state. Furthermore, there are numerous new threats which have appeared over the ensuing decades which I think makes our task even more difficult than it was for the Fisher-Goodrich-Harper generation of Classical Liberal/libertarians.

Long-standing and on-going threats to liberty include:

- the general policy of government intervention in the economy (“interventionism”). As understood by Ludwig von Mises, this where the state attempts to plan, regulate, or even own and control certain sectors of the economy, either as a result of the “necessity of fighting a war (as in WW1 and WW2) or in peacetime because of perceived “market failures”, or the demands of running a welfare state.

- the rivalry (“cold war”) between the major nuclear powers and the threat of MAD (mutual assured destruction), especially in disputes arising between the US, the Soviet Union (now Russia) and China. And possibly Israeli and the Arab world.

- military intervention and support for right-wing dictatorships in order to “contain” or “roll-back” “communism”. In the post-war period this took the form of opposition to nationalist or anti-colonial movements (especially in Vietnam). Domestically this required the introduction of conscription (the draft) and large increases in military spending; the rise of the MIC Military-Industrial Complex).

- the expansion of the welfare state, (or HEW = health, education, and welfare), with its growing class of people dependent upon state handouts as well as the bureaucrats who administer the programs and thus have a vested interest in its continuation.

- the close relationship between some large corporations and financial groups who seek and get special (legal) privileges, subsidies and bailouts, protected markets, and large taxpayer funded contracts from the state to further their own interests at the expence of ordinary taxpayers and consumers; this was called “rent seeking” but better known today as “crony capitalism”

- inflation and the expansion of the money supply by government monopoly Central Banks, now called “quantitative easing”

- the expansion of state-funded schools and universities, leading to the dominance of left-wing and Keynesian ideas within the academy

- the expansion of the regulatory state, or the “nanny state”, the “administrative state”, or the “deep state”.

New threats to Liberty over the past 20 Years

I would also add the following list of new threats to liberty which have emerged over the past two decades, especially as a result of the attacks of 9/11 2001, the global economic crisis of 2008-9, and the Covid lockdowns of 2020-22:

- the rise of the “surveillance state” after 9/11 with the monitoring of all telephone and email communication, and now the censorship of so-called “disinformation” spread via social media companies; it should be noted that Australia has played an important role in the emergence of the surveillance state by its membership in the Five Eyes intelligence alliance which is made up of Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, and the United States.

- the use of ”quantitative easing” and near zero interest rates, the government bailout of the banks and large investment firms, and the massive increase in government debt as a result of the global economic crisis of 2008-9 and the Covid lockdowns and government subsidized vaccinations after March 2020

- “liberal interventionism” in foreign policy, i.e. the many “small” wars fought by the US/NATO and their allies (like Australia) to achieve “regime change” or promote the spread of “democracy” or fight “communism” (now “terrorism”); Australia has a long history of getting involved in these “small wars” reaching back to the Boer War (1899), Malaya (1950s), Vietnam in the 1960s, up to the failed wars in Afghanistan and Iraq.

- the rise of a radical “Green” environmentalist movement which is demanding massive government intervention in and regulation of the economy in the form of a Green New Deal, government subsidies for “renewable energy,” and policies of carbon “neutrality” or “net zero”.

- the rise of “neo-protectionism” and “national industrial policy which is a key platform of various nationalist and “populist” leaders such as Pres. Trump and a new form of “conservative” thought known as “National Conservatism”

- the resurgence of explicit interest in and support for “socialism” especially by young people which was noticeable at the time of the anniversaries of the birth of Karl Marx (1819) and the Bolshevik Revolution (1917); this also includes the respect some intellectuals and commentators have for the policies of the Chinese Communist Party as another path for economic development to take, or to control the spread of the Covid virus.

- the emergence of the “Lockdown State” and what I call “Hygiene Socialism” (even “hygiene fascism” in some places like China, Italy, and Victoria) during the Covid panic of 2020-2022; this has resulted in the acceptance by the general public that our lives should be controlled by “experts”, that our liberties can be “suspended” indefinitely, and that governments can and should centrally plan key sectors of the economy. See my blog post on “What is to be Done? The Rise of Hygiene Socialism and the Prospects for Liberty” (2 December, 2020) http://davidmhart.com/wordpress/archives/898.

- the continued domination of the universities and schools by leftist intellectuals who have among other things promoted “woke-ism”, identity politics, the de-platforming of divergent opinion, the promotion of and Critical Race Theory; there has also been a strong movement to downplay the importance of the contribution of “Western Civilisation” to the development of the ideas and institutions which have made possible the emergence of individual liberty, free markets, limited government, and peace.

IV. The Task ahead↩

An Overview of the Problem: Ideas, Policies, Interests, and Public Opinion

When one adds all these up the list is a formidable one (the above contains at the moment some 16 items) and it is so daunting for the future of the liberty movement that one wonders where to begin. For each of these threats to liberty there are some common elements and some common tasks which those in the liberty movement will have to undertake:

- there are the theoretical ideas upon which government policies are based and which are used to justify these policies: these theoretical ideas are typically developed and propagated in the economics and politics departments of universities and colleges and so this is the arena where they need to be challenged and refuted;

- there is also the specific policies based upon these ideas which are developed by think tanks, policy institutes, and advocacy groups which lobby politicians for their introduction; these policies need to be challenged by other “free market” policy institutes which can offer critiques of existing policies and alternative policies which advance the cause of liberty

- there are the entrenched vested interests (both political, bureaucratic, economic, and “social”) which will vigorously defend their continued existence and even their expansion: this is a political problem which has to be addressed at the legislative level

- there is an ignorant or misinformed public who either tolerate these policies or demanded them in the first place: this problem has to be addressed by a broadly based campaign to popularise sound economic thinking

Each one of the threats to liberty I have listed above individually would require a small army of academics, intellectuals, journalists, agitators, and sympathetic politicians and voters to challenge the policies and to begin the long task of repealing them. Multiply this by 16 and one can get a sense of the task ahead.

Some Thoughts on an Overall Strategy

What defenders of liberty need is a well thought out and practical strategy or set of strategies in order to meet these threats and begin to reverse them. Unfortunately, strategic thinking has never been a strong point of the Liberty movement over the decades. [7] Being individualists at heart many defenders of liberty quite rightly want to tread their own path through the thicket of statism. This approach has its strengths and weaknesses but I would argue that people who share a common goal should cooperate with each other in order to get the greater productivity of the division of labour and the gains of trade. Thus, here are my suggestions of things we in the Liberty movement should seriously consider:

- there is a need for a division of labour in the Liberty movement , where those with special interests and skills apply themselves to opposing one of these threats. This happens to a considerable extent already today with groups which focus on environmental issues, war and peace, government regulation, and so on. For new entrants, the question then becomes whether or not to join an existing organisation, or found their own organisation (say in a region or a country which does not have such a group)

- there is a need for “movement investors” and “intellectual entrepreneurs” who have the skill to identify an emerging new problem which needs addressing, finding the people and the funding to organise them into a coherent group, and guiding them through the labyrinth of practical politics to get the changes which are required. The founders of the organisations I mentioned at the beginning of this paper were such movement investors and entrepreneurs and their activities should be studied closely by us today: Leonard Reed (FEE), Anthony Fisher (IEA), Pierre Goodrich (LF), and Harper (IHS). I would place Ron Manners in this important group for obvious reasons.

- there need to be be “feeder organisations” which can identify young and emerging talent, help them to be trained in the theoretical and political skills needed to be effective advocates and agitators for liberty. These feeder organisations should be directing the young talent (university students) they identify and train into various paths such as think tanks, lobby groups, existing political parties (“infiltrating the enemy’s camp”), or a separate “Libertarian” or “Classical Liberal” party. A related path which requires a different set of organizational skills leads to academia. Examples of such feeder organisations include FEE, the IHS (especially its “Liberty and Society” summer seminars), the CIS (which has a L&S seminar modeled on the IHS’s), and Mannkal.

- there needs to be organisations or research centres to support academics who are interested in free market ideas and CL political philosophy; these people need to be found, cultivated, and supported as they move through what is a very hostile intellectual environment (the “academy”). Some examples of such research centers include David Schmidtz’s Center for the Study of Freedom at the University of Arizona, Peter Boettke’s F.A. Hayek Program for Advanced Study in Philosophy, Politics, and Economics at George Mason University, and Aurelian Craiutu’s Ostrom Workshop at Indiana University, to mention only a very few. [8] What needs to be noted here is how few organisations like these exist in Australia.

- there needs to be “outreach programs” to take the message about political and economic liberty to high school students, high school history and economics teachers, and the interested general public; this effort will require skillful writers and speakers who can make complex ideas, especially about how markets operate, accessible to non-expert audiences whose minds are filled with misconceptions and errors which they have learnt at school or via social media. Some examples include FEE which was originally designed to reach out to young high school and college students, more recently the Bastiat Society (hosted by the American Institute for Economic Research) [9] which is designed to reach out to young professionals and other members of the public with monthly talks hosted by the local chapter and which has affiliates in 20 countries (not yet Australia) and David Schmidtz’s high school economics teachers seminar program. [10] Special note should be made of the relatively new Australian Ramsay Centre for Western Civilisation [11] which has established a lucrative scholarship program in a small number of Australian universities (in the face of considerable opposition) and hosts regular public talks on “the great books.” The Ramsay Centre does not appear to be very CL but it may become an important ally, at least in this important intellectual struggle within the academy.

- finally, there needs to be coordination among the various groups in order to avoid unnecessary and expensive duplication, and to identify gaps in the movement which might need to be filled, or to address a new threat to liberty which might suddenly emerge as a result of a crisis

Of Special Concern to Australia and the Asian Region

Could Australia become the new “beacon of liberty” in our region?

The problem for a small, remote, and relatively insignificant country like Australia is to figure out what it can do to contribute to the broader, international Liberty movement and where it fits in. One possibility is for it to become a “beacon of liberty” now that Hong Kong is in the process of losing that status as it is gradually swallowed up by the CCP, and given the fact that the government of Singapore has strongly authoritarian bent. (See the ranking for economic and social freedom in Singapore given by the Index of Human Freedom. [12] ) Imagine there being a truly liberal nation which is independent of “entangling alliances”, highly productive and competitive in world markets, fully open to the free movement of goods, services, and people, and which is able to spread the ideas of liberty to the rest of the world.

Is individual liberty” a “Western” notion?

Another problem which needs to be recognized is that for non-Western nations without an historical tradition of thinking about individualism, autonomy, natural rights, limited government, and the rule of law (among other things) there is an additional hurdle to be overcome in spreading the word about liberty in its many dimensions. [13] Can a society be truly “free” only in the economic sense of the word, without it also needing to be free in the “political” sense. Milton Friedman for one said that the two were intimately connected. [14] However, these concepts are often regarded as being a “western imposition” which does not reflect the needs and traditions of non-western cultures. How to overcome this perception and to express the benefits of liberty of all kinds (not just economic, but also political and social) in a form relevant to these cultures is a significant problem which needs to be addressed.

Exposing the weaknesses of the autocratic “Asian modern” of economic development

A third problem is that critics of CL argue that the economic success of countries like Japan, South Korea, Singapore, and perhaps now China, shows that politically directed economic development by an elite of trained expert technocratic managers and far-seeing paternalistic and authoritarian political leaders, has shown that there is an alternative to the western example of free and autonomous individuals pursuing their own interests within a framework of free markets, private property, the rule of law, and limited government. To overcome this argument we will need more studies by historians and economists which show that

- centralized technocratic and political management has not been as successful as claimed by its supporters and has resulted in many failures and distortions, [15]

- that Bastiat’s “what is unseen” argument still applies, [16] namely that economic development would have been better and more comprehensive if it had taken place in a free market and perhaps taken a different direction which might have benefited ordinary people more than it has

- that it has produced societies dominated by very powerful and rich elites (crony capitalists or “crony communists”) who have benefited at the expense of ordinary consumers and taxpayers, and smaller producers (would be competitors)

- that Asians too have (or will soon have) aspirations for freedom of speech, political involvement, and other “western-style” individual freedoms, which will need to be satisfied. Studies of the beliefs and behaviour of the Asian diasporas in places like Australia, Canada, Britain, and the U.S. might shed some light on this.

V. Looking for the “Golden Thread” to unravel justifications for State Intervention↩

Introduction:

Is there a single “golden thread” which links all these disparate threats to liberty together, so that unraveling or cutting this one thread will end many of these threats in one blow so we don’t have to fight each one individually?

On the other hand, there may not be just one “golden thread” we have to cut, but a bundle of them. The following is a list of four key ideas which I think are common to many if not all forms of justifications for state control and intervention in the economy and in people’s lives in general. To undermine or refute any one of these key ideas would, I think, take us a long way to persuading people to rethink their faith in government intervention in all aspects of our lives:

- the morality of using coercion

- misperceptions and exaggerations about the extent and cause of market failure

- the lack of understanding of the extent and cause of government failure

- public ignorance of basic economic insights which makes points 2 and 3 possible

1.) The morality of using coercion

There is an almost universal belief that there is a difference in the sort of behaviour states and their agents can engage in compared to ordinary mortals like us. The common belief is that states are “justified” in the use of coercion to compel compliance with regulations, to seize our property in the form of taxes or other “takings”, and to kill other people in war, whereas ordinary people are not justified in using coercion in this manner. [17] In the heyday of CL this used not to be the case. Most people had a strong moral belief in the importance of being independent and responsible for one’s own (and one’s family’s) welfare and not being a “burden” on others - the idea of “self-help” - and especially not taking money or other benefits from the state.

In Australia, [18] which lacks a strong tradition of thinking about natural rights [19] and a Bill of Rights to enshrine and protect them (unlike the US), the dominant political ideology is one of “expediency”, where the use of coercion is considered to be essential in order to “get things done” or in “solving problems.” This belief makes it possible for the emergence of a government based upon “technocratic managerialism” and the “dictatorship of Parliament”, which is supported by both major parties who take it in turns to be the “manager” or the “dictator” of the day.

There would be much less tolerance for the government’s use of coercion if more people thought that the use of coercion by anybody is immoral. If they believed this, then they would feel outrage or contempt for those politicians and bureaucrats who used coercion every day to achieve their goals, they would feel ashamed and guilty if they personally sought and got handouts from the state which are financed at taxpayer expence (and thus got by means of coercion through compulsory taxation); or if they sought privileges from the state like monopolies, subsidies for their business, or the exclusion of potential competitors.

For those who defend “limited government” the argument has to made that the sole legitimate function of government is to protect the life, liberty and property of citizens by minimizing the use of coercion by one person against another (such as robbers, fraudsters, rapists, and murderers), and that the coercive actions of the state and its agents must also be strictly limited in scope, otherwise it in turn will become a “predatory state”, [20] which will pose a threat to the life, liberty and property of the very people they are supposed to be protecting.

Side note: Furthermore, there is a serious problem for defenders of “limited government” given the fact that it seems to have been impossible historically to keep the state to a limited number of clearly defined activities. The experience of the late 19th and 20th centuries has clearly shown that all governments have steadily expanded in size, increased the scope of their activity, and taken more in taxes and imposed greater numbers of regulations as each year has passed. Given the power and influence of the vested interests which have benefited from this expansion it seems politically impossible to reverse course. On the occasions when it seemed a reduction of state power and intervention was possible, for example under PM Margaret Thatcher in Britain and President Ronald Reagan in the US during the 1980s, these reductions were only temporary and after they left office the state continued on its path of steady expansion and growth. [21]

We should also make the case for the virtue of “self-help”, that instead of seeking government organized and tax-payer funded “charity” in times of economic hardship we should take steps on our own to avoid or prepare for economic hardship, or organise with others (family, neighbors, like-minded people) to help those in genuine need. We also need to use social ostracism against those who receive tax-payer funded handouts, subsidies; and those who seek to rule others, in order to discourage them from continuing these practices.

2.) Misunderstanding the nature of “Market Failure”

It is crucial for us to disabuse people of the mistaken idea that the market has inherent flaws which inevitably lead to serious problems unless “corrected” by government action. These “market failures” are typically thought to be things like the monopoly and predatory power of large corporations, the boom-bust economic cycle, environmental “degradation” caused by any industrial activity, and the inability to provide all kinds of “public goods”. [22]

There is thus a need for a better theoretical and historical understanding of what constitutes “market failure”, why and how they happen, and what can be done to rectify them. Free market economists have produced many studies which have examined why markets “fail” but these are not well known among the general public: that “failure” is due to previous or continuing government regulation, the prohibition of competition, the lack of clear property rights; and the absence of free market price signals. There are also many historical works which show that “public goods” have been provided privately on the market (also known as “private governance”) in the past and can be provided again in the present if they are allowed to do so. [23]

3.) Ignoring the even greater Problem of Government Failure

The theoretical counterpart to the concept of “market failure” which is grossly exaggerated by most people, is the notion of “government failure” which is largely ignored. [24]

For example, there is a near universal belief that governments and “experts” (technocrats) employed by the government can solve problems, “manage” the economy, and provide services which private individuals cannot. [25] This belief has been maintained in spite of the many disastrous attempts by government in the 20th century to “plan” or “manage” the economy, and the theoretical work of the Public Choice school of economics, whose insights are almost universally ignored by the economics profession.

There is an entire gamut of public choice insights which need to be better appreciated by the public. These include the self-interested behaviour of politicians and bureaucrats; the inevitable capture of the state (parliament) and its regulatory bodies by powerful vested interest groups; the problem of “perverse” institutional incentives, and the issue of “political” rent-seeking by vested interests .

There are also important insights which have been made by the Austrian school of economics, [26] especially by Ludwig von Mises and Friedrich Hayek, such as Mises on the “impossibility” of rational economic calculation under socialism due to the absence of free pricing (especially of capital goods), [27] and Hayek’s “problem of knowledge” which is that central planning can never have the widely dispersed local knowledge of consumer needs, the availability of resources (and any possible substitutes or alternatives), and the constant changing local conditions which are necessary for production of goods and services to take place. [28]

These insights mean that any government attempt to “manage” or “centrally plan” an economy is doomed to failure, whether this be the “total or universal” central planning which the Soviet Union attempted to do, or whether it be “partial or sectoral” central planning which many so-called “liberal democracies” attempt to do with industrial policy, renewable energy production, or vaccine development. [29]

4.) Public ignorance of basic economic concepts

Time and time again we see how deep the general public’s ignorance of basic economic ideas is. Every time there is a major storm or flood and the price of bread or bottled water goes up, the public denounces shop keepers for “price gouging” and calls for government regulation and price controls. There is a widespread belief in what I call “magical thinking” when it comes to public policy, namely the commonly held view that governments can create wealth out of nothing by issuing paper or electronic “money” in times of crisis (the most exaggerated and recent version of this belief is held by supporters of “Modern Monetary Theory”), that it can create a “net” increase in jobs and economic activity by taxing one group of people and giving the money to another group, and that, as Bastiat once put it, some people think they have “the right to live at the expense of everybody else”.

The mid-19th century French economists Frédéric Bastiat was the most brilliant populariser of economic ideas who has ever lived, but even he could not disabuse the French public of these commonly held economic “fallacies” or “sophisms”: [30] that there are opportunity costs for every economic decision one makes; that there are “the seen and the unseen” consequences of economic actions (especially government intervention in the economy); the idea that every action has a cost and a benefit which is different for different people and groups; the inevitability of “unintended consequences” of government regulations, and so on.

The persistence of these economic “fallacies” in the mind of the public indicate that we need a new Frédéric Bastiat to popularise economic ideas, not to mention better trained economic journalists who also share these false economic views and spread them to the reading public. In the 1940’s there was the great popularizer of free market ideas, Henry Hazlitt, at the New York Times; in the 1970s there was the free market Chicago School economist Milton Friedman who had a column in Newsweek magazine; and today we have several such as Econlog (with Bryan Caplan and Pierre Lemieux) and Café Hayek with Don Boudreaux. Unfortunately there is noting like this today in Australia, although it should be remembered that Bert Kelley (the “Modest Member”) had a column in The Bulletin magazine for many years.

VI. Choosing the Right Kind of Arguments to use↩

Introduction

Selecting the right kind of arguments in order to defend liberty and criticize government intervention and coercion is an important strategic matter as different people respond to different kinds of arguments. For example, some people find “economic” arguments heartless and respond better to moral arguments about “fairness” and justice. In Australia there is a strong belief in the idea that people should be given a “fair go” which might be a useful lever for CLs to use in making their arguments. What constitutes a “fair go” could be interpreted as supporting an interventionist welfare state which needs to create by means of coercion a more “level playing field” upon which people can go about their lives. Or, it could be given a more C L interpretation where government granted privileges to some at the expense of others, and impediments erected to hinder voluntary economic activity, all need to be removed so that every individual has a chance to succeed and flourish as they choose.

Other people are driven on a more emotional level to seek safety or protection from life’s uncertainties, or some immanent crisis or perceived catastrophe such as climate change or a virus pandemic. Hence their demand that “the government do something” to solve the problem immediately. According to the Hypocratic Oath which is supposed to guide the actions of doctors, they swear upon the principle of “primum non nocere” (first do no harm). This should also be the oath taken by all politicians and bureaucrats, perhaps with the codicil that they “primum nihil facere” (first do nothing) in order to let the voluntary actions of people (“the market”) sort out the problem first. This near universal demand that “the government should do something” is based upon two errors in people’s thinking, namely an exaggerated belief in the idea of “market failure”, and a related and even more exaggerated belief in the possibility of “government success” in solving problems.

So, in order to change the way many people think about the role of government, we have to identify the kinds of people we are trying to convince and to select the best kinds of arguments to suit that particular group.

I think defenders of liberty need to appeal to the following different groups:

- the average voter (this is the job of a political party, or single issue political movements)

- people who are still forming their opinions, such as students (this is done by groups like Mannkal, CIS, IPA, and in the US the Institute for Humane Studies)

- educated people who might be swayed at the margin (CIS, IPA)

- sympathetic politicians (either from the “left” or the “right”) - if there are any

- sympathetic academics and intellectuals (journalists, writers, artistic types) - if there are any! (IPA, CIS, Liberty Fund)

CL and libertarians have historically used a “smorgasbord” of arguments to defend liberty which include:

- moral arguments which appeal to justice and a particular moral theory concerning property rights, individual liberty, and the nature of political power (coercion)

- economic arguments which appeal to notions of economic efficiency and the greater productivity of free markets

- political arguments about the dangers posed by political power and the need to limit it, and how best to organise the political system in order to enable the state to undertake properly its legitimate functions (if any)

- historical arguments concerning the evolution and expansion of state power over the past century (Higgs’ “ratchet effect”), the nature and causes of government failure, the nature and causes of market failure, the struggle for liberty in previous centuries (the “Great Emancipation), and the vast improvement in the human condition brought about by free market “capitalism” (the “Great Enrichment”)

1.) Moral Arguments

Some of the moral arguments which have been used to defend liberty and oppose government interventions include:

- that the use of coercion against others is immoral and a violation of their natural rights to life, liberty, and property (this was the central theme of the Workers Party platform of 1975 where an anti-coercion statement, called the “fundamental principle”, was placed on every page, namely that: “No man or group of men has the right to initiate the use of force, fraud or coercion against another man or group of men”) [31]

- people should be “free to choose” and then pursue whatever life goals they prefer (however they imagine them - Jeffersons’ idea of “the pursuit of happiness” which is enshrined in the “Declaration of Independence”) without outside interference (i.e. force); so long as they respect the equal right of others to do the same (Herbert Spencer’s “law of equal freedom”) [32]

- that this “freedom to choose” [33] is what it means to be “human” and that to prevent individuals from doing this is fundamentally wrong (as it demeans their “humanity”)

- the goal is “flourishing” both as an individual and as well the groups and communities these individuals voluntarily associate with or create [34]

- the means to achieve this goal is non-violence, cooperation, mutually beneficial association for production and trade, and the division of labour

- a belief in the dignity and worth of productive labour, producing goods and services to satisfy the needs of others (the “bourgeois values” that McCloskey discusses in his trilogy) - these activities are “morally good” and worthy of social recognition

- conversely, the “immorality” of acquiring wealth or political privileges by the use of power, and coercion exercised over others; that seeking such power over others should be regarded as immoral, and not what free individuals should do or aspire to; this moral stricture would also apply to politicians, bureaucrats, privilege or rent-seekers, government contract seekers, and wielders of coercive power (police and military) who overstep their bounds

- the idea that it is wrong to accept “compulsory charity” or benefits from the state at the expence of others (taxpayers); people should think of this as shameful and not a “right” that is due to them from others

2.) Economic Arguments

These are very well known in CL/Libertarian circles so I will not provide a comprehensive and detailed list here. [35] They can be summarized as arguments about the greater efficiency and productivity for free markets (capitalism):

- the greater wealth creating possibilities of “free market capitalism” due to mutually beneficial cooperation, the division of labour and specialization, and free trade (both domestic and international)

- the incentives to be productive and satisfy the needs of others (consumers) caused by the private ownership of property, and the possibility of making a profit (with the corresponding disincentive of making losses)

- the ability of free market prices to rapidly convey information about what is demanded by consumers, how pressing or urgent that demand is, what resources are available (and their potential alternatives and substitutes), and at what cost for producers to create and then deliver these goods and services to consumers

- the extraordinary innovations made possible by the free market (capitalism) which are the result of the advance of scientific knowledge, technological improvement, simple trial and error, and the existence of entrepreneurs who are able to identify new opportunities to satisfy consumer needs (and thus make a profit) and carry them out successfully

- the existence of “competition” between producers for new customers creates greater choice and lower prices

- the much greater life choices made possible for individuals (especially women, and peasant farmers) by an extensive, global and international division of labour

- the more general “creative” benefits of free, open and tolerant societies in the cultural sphere

3.) Political Arguments

Again, the number of works which lay out the basic principles of CL is enormous. There are classic 19th century statements [36] , some 20th century classic statements, [37] a vast compendium of facts and arguments, [38] and an increasing number of 21st century surveys and statements. [39] I can only summarise some of the main arguments here:

- a liberal and democratic political system, in theory, makes it possible for ordinary citizens (voters) to make their rulers accountable for their actions, and to help determine how much and what kind of taxation and regulation by the government will be permitted (although this ability is often exaggerated by supporters of democracy); the benefit of democracy is that the voters can get rid of bad politicians and bad policies without resorting to violence; the weakness of democracy is that all new governments have a strong incentive to become bad governments which introduce bad policies again in an endless cycle

- interventions in the economy [40] (and in private life in general) create additional problems because of inevitable government failure, the creation of perverse incentives, and unintended consequences (Bastiat’s “the seen and the unseen”); there is pressure on government by voters which pushes politicians to intervene again and again to solve the problems caused by these previous interventions ( Mises’ “dynamic of interventionism”) [41]

- periodic crises (economic recessions, depressions, war, epidemics) lead voters to demand that “the government do something” which usually means greater intervention in the economy, higher taxes, and more regulation of private lives; once the crisis is over the regulations and taxes may decrease but not to their previous lower level, thus leading to the gradual expansion of state power over time (Robert Higg’s “ratchet effect”) [42]

- power attracts unsavory types of people (predators, arrogant ideologues and would-be rulers) and “do-gooders” (perhaps naive and well-meaning) who want to use state power to achieve their ends (Hayek’s “why the worst get on top”); [43] this can only be prevented by reducing the power and scope of the state to make it less attractive to predators and impossible for these people to act in this way

- political power inevitably attracts rent-seekers [44] of various kinds and the “rent seeking societies” which result have taken different historical forms, such as mercantilism during the16th to the 18th centuries, [45] communist central planning between 1917 and 1990, [46] and state capitalism in non-communist societies, [47] and most recently crony capitalism. [48] A common feature is that certain individuals, firms, and groups have access to politicians, regulators, and bureaucrats and lobby or bribe them to do the rent seekers favors in return for certain benefits in return (campaign funds, jobs on company boards later, bribes, ownership of state property); this attraction to power will not end until political power is reduced or removed entirely; even in so-called “liberal democracies” rent seeking is a serious problem and is one of the contradictions of democracy, by which I mean that it has built-in incentives and existing political mechanisms which enable those who wish to undermine liberty to do so

- the welfare state inevitably creates a “dependent class” who will never vote for cuts in government expenditure; they in turn create a permanent and growing class of welfare administrators and distributors with a very strong self-interest to defend; the real danger is that if or when those who receive benefits become the majority they will always vote to protect (or even expand) these benefits (another contradiction of democracy)

- politicians often play the “nationalism card” to persuade voters to accept considerable intervention in the economy, such as the idea of the need for “national industries” (like a car industry) or for the state to seek “energy independence” (via heavily subsidized “renewable energy”), or even “national greatness”; nationalism is usually taught in the state school system (via nationalist history) and promoted by means of “national holidays”, saluting the flag, reciting oaths of allegiance; CL/libertarians need to persuade voters that we need to find a way to combine being a member of an internationally diverse and integrated trading system and the desire of many voters to express their feelings of patriotism (nationalism?) which can often be quite narrow and parochial

4.) Historical Arguments

Hayek observed that people often get their economic ideas indirectly by means of the history they were taught at school. [49] For example, the belief that “capitalism” underwent a crisis or even a breakdown during the Great Depression and that western economies were only saved by massive government intervention; or that the industrial revolution impoverished millions of people and forced them to work under nearly slave-like conditions. [50] The task for defenders of liberty is to show that the benefits of the free market and the harms of government intervention are not just theoretical matters but can be demonstrated by many historical and present-day examples. The general ignorance of the public on these matters is truly staggering and it will require an enormous effort to rectify this massive problem.

Thus this section will have two parts (many of the remarks made above also apply to this section):

- a.) the failures and harms caused by government intervention and political privilege

- b.) the successes and benefits of free markets and limited constitutional governments

a.) The failures and harms caused by government intervention and political privilege

- the poverty caused by hundreds of years of serfdom and slavery which were institutions protected and enforced by the state

- the death and destruction caused by hundreds of years of inter-state rivalry and wars

- the suffering of people in “the colonies” who were enslaved and exploited in other ways for the benefit of privileged traders and plantation owners;

- the violation of the freedom of speech and association caused by the banning of rival religious groups by the privileged established church

- the exclusion of working and middle class people (and of course women of all socio-economic classes) from participation in elections which enabled privileged elites to set the kind and level of taxation (and other legislation and regulations) to suit themselves at the expence of ordinary people

- and with the massive increase in the size and scope of state power in the 20thC we have bigger and better examples of government failures on a colossal scale, such as the “Great War” (WW1), the rise of communism in Russia and China, the rise of fascism and Nazism in Italy and Germany, the “Great Depression”, Prohibition I (of alcohol in the US in the 1920s), the “War on Poverty” since the 1960s; Prohibition II (the “War on Drugs” since the 1970s), the rise of the “‘surveillance state” after 11 Sept. 2001, and most recently the attempt to eliminate or control the spread of the Covid virus by means of coerced lockdowns (home imprisonment) and other draconian restrictions of economic and social life.

- it should be noted that probably the biggest single expansion of government power occurred during WW2

- it should also be noted that the “War on Terrorism” since 2001 has also been a spectacular and costly failure

b.) The successes and benefits of free markets and limited governments

The successes and benefits of free markets and limited governments can be summarised as the result of the “Great Enrichment” (Deidre McCloskey) [51] and the “Great Emancipations” (David Hart, Peter Boettke, and Richard Ebeling) [52] which have taken place since the mid-18thC. The failures and harms listed above were either eliminated or significantly ameliorated by these two great forces of emancipation and enrichment which began to exert themselves during the Enlightenment, and put into practice, with varying degrees of success, during the American and French revolutions (see Rothbard on the American Revolution as a CL revolution; [53] and Jonathan Israel on how the American Revolution put radical enlightened and liberal ideas into practice and inspired the world [54] ), and then the various liberal reform movements in Europe (and Australia) during the 19th century. [55] What needs to be stressed is that these reforms were driven by the spread and adoption of liberal ideas about individual liberty, the protection of life and property, and restrictions on the power and scope of government activity.

These reforms included:

- the abolition of serfdom and slavery

- the expansion of the franchise to include first middle class votes, then more working class votes, and then eventually women voters.