David M. Hart, "Entrepreneurs, Investors, and Scribblers: An Austrian Analysis of the Structure of Production and Distribution of Ideas"

[Updated: October 21, 2015]

A Paper given at the Southern Economics Association 2015 Annual Meeting

New Orleans, November 21–23, 2015

Session: [3.D.6] Entrepreneurial Solutions to Public Problems

(Sponsored by Society for the Development of Austrian Economics)

Monday, November 23, 2015; 3:00 - 4:45 pm.

An online version of this paper is available here:

HTML: <davidmhart.com/liberty/Papers/DMH_StructureProductionIdeas21Oct2015.html>.

PDF: <davidmhart.com/liberty/Papers/DMH_StructureProductionIdeas21Oct2015.pdf>.

Draft: February 9, 2015

Revised: October 21, 2015

Word Length: 11,580 w. (body of the paper)

Author: Dr. David M. Hart.

- Director of the Online Library of Liberty Project at Liberty Fund <oll.libertyfund.org> and

- Academic Editor of the Collected Works of Frédéric Bastiat.

Email:

- Work: dhart@libertyfund.org

- Private: dmhart@mac.com

Websites:

- Liberty Fund: <oll.libertyfund.org>

- Personal: <davidmhart.com/liberty>

Bio

David Hart was born and raised in Sydney, Australia. He did his undergraduate work in modern European history and wrote an honours thesis on the radical Belgian/French free market economist Gustave de Molinari, whose book Evenings on Saint Lazarus Street (1849) he is currently editing for Liberty Fund. This was followed by a year studying at the University of Mainz studying German Imperialism, the origins of the First World War, and German classical liberal thought. Postgraduate degrees were completed in Modern European history at Stanford University (M.A.) where he also worked for the Institute for Humane Studies (when it was located at Menlo Park, California) and was founding editor of the Humane Studies Review: A Research and Study Guide; and a Ph.D. in history from King’s College, Cambridge on the work of two early 19th century French classical liberals , Charles Comte and Charles Dunoyer. He then taught for 15 years in the Department of History at the University of Adelaide in South Australia where he was awarded the University teaching prize.

Since 2001 he has been the Director of the Online Library of Liberty Project at Liberty Fund in Indianapolis. The OLL has won several awards including a “Best of the Humanities on the Web” Award from the National Endowment for the Humanities, and was chosen by the Library of Congress for its Minerva website archival project. He is currently the Academic Editor of Liberty Fund’s translation project of the Collected Works of Frédéric Bastiat (in 6 vols.) and is also editing a translation of Molinari’s Evenings on Saint Lazarus Street: Discussions on Economic Laws and the Defence of Property (1849). He also edits the following online projects:

- Liberty Matters online discussion forum

- Quotations about Liberty and Power

- The OLL Reader: An Anthology of Key Works about Liberty

- Images of Liberty and Power: A Collection of Illustrated Essays

- a 7 volume collection of 17th century Leveler Tracts (1638–1660)

David is also the co-editor of two collections of 19th century French classical liberal thought (with Robert Leroux of the University of Ottawa), one in English published by Routledge: French Liberalism in the 19th Century: An Anthology (Routledge Studies in the History of Economics, May 2012), and another in French called L’âge d’or du libéralisme français. Anthologie XIXe siècle (The Golden Age of French Liberalism: A 19th Century Anthology) (Paris: Editions Ellipses, 2014).

Abstract

(210 words) Austrian capital theory is applied to the study of how ideas (in this case classical liberal or libertarian ideas) have been produced, distributed, and consumed. It is based upon an examination of three key historical examples - the Anti-Corn Law League in the early 1840s, the Political Economists in Paris during the 1840s, and the activities of the Institute of Economic Affairs in London in post-war Britain. It is argued that there is a long structure of production in the realm of ideas as there is for capital goods, with highest order goods (the production of high theory) most removed from ultimate consumption (politicians, ordinary people, voters), and with several middle order stages which serve as intermediary steps along the way (production of ideas for college professors, intellectuals, members of think tanks, journalists, and lobbyists). In each of these historical examples there are investors with capital who invest in creating organisations to promote certain ideas, “entrepreneurs of ideas” who see opportunities for bringing together the right combination and mix of individuals with different talents to bring this about, marketers and other promoters who are able to sell these ideas to a broader public, and finally the ultimate consumers of these ideas who accept them and act on them in some way.

(102 words) Austrian capital theory is applied to the study of how ideas have been produced, distributed, and consumed. It is argued that there is a structure of production in the realm of ideas as there is for capital goods, with highest order goods (the production of high theory) most removed from ultimate consumption (politicians, ordinary people, voters), and with several middle order stages which serve as intermediary steps along the way. One can also identify other counterparts, such as investors, “entrepreneurs of ideas,” marketers and salespeople, distributors, and the ultimate consumers of ideas who accept them and act on them in some way.

Table of Contents

- Entrepreneurs, Investors, and Scribblers: An Austrian Analysis of the Structure of Production and Distribution of Ideas

- Introduction

- Towards a Strategy for Achieving Radical Change

- Austrian Capital Theory and the Structure of Production (of Goods)

- The Structure of Production and Distribution of Ideas - an Austrian Analysis

- Some Definitions

- The Highest or Fourth Order of the Production of Ideas - the development of high theory.

- Third Order Production of Ideas - the education of academics, intellectuals, and other informed members of the public.

- Second Order Production of Ideas - influencing politicians and legislators.

- First Order Production and Ultimate Consumption of Ideas - influencing ordinary people who act on their beliefs or principles.

- Two Alternative Perspectives: “Applied Hayek” and “Academic Scribblers”

- Summary

- Some Historical Examples

- Introduction

- Side Bar: “Hart’s 70 Year Rule”

- Some Historical Examples

- Historical Example 1: the Anti-Corn Law League in the early 1840s

- Historical Example 2: the Political Economists in Paris during the 1840s

- Summary of the Structure of Production of Ideas

- Summary of Key Roles

- Historical Example 3: the activities of the Institute of Economic Affairs in London in post-war Britain

- Historical Example 4: the Current Structure of the Classical Liberal/Libertarian Movement

- Further Thoughts and Some Questions and Complications to Consider

- Mises on Ideas and Interests: or Interests as Ideas

- Hayek on Utopias and History

- “Malinvestments” and the Distortion of the SPI

- The Internet and the changing Relative Costs of the Production and Distribution of Ideas

- The Relative Costs of changing Core vs Non-Core Beliefs: or, it is always cheaper at the margin

- Bibliography of Works Cited

- Endnotes

Entrepreneurs, Investors, and Scribblers: An Austrian Analysis of the Structure of Production and Distribution of Ideas

Introduction↩

I would like to begin by shamelessly stealing some ideas from Ed Lopez. He reminds us of the striking, parallel thinking of two widely divergent economic theorists, namely John Maynard Keynes and Friedrich Hayek. To begin with the latter:

In the light of recent history it is somewhat curious that this decisive power of the professional secondhand dealers in ideas should not yet be more generally recognized. The political development of the Western World during the last hundred years furnishes the clearest demonstration. Socialism has never and nowhere been at first a working-class movement. It is by no means an obvious remedy for the obvious evil which the interests of that class will necessarily demand. It is a construction of theorists, deriving from certain tendencies of abstract thought with which for a long time only the intellectuals were familiar; and it required long efforts by the intellectuals before the working classes could be persuaded to adopt it as their program.[1]

The flow of ideas in Hayek’s view goes from the “theorists” who spend their time “constructing” “abstract thought”; to the “intellectuals whom he describes as ”secondhand dealers in ideas“; to their final destination in the minds of ”the working classes“ who adopt them as part of their program. Hayek describes the time frame for the transmission of ideas quite vaguely, as ”a long time“ and only after ”long efforts".

Thirteen years earlier Keynes expressed something very similar, but using different though still somewhat contemptuous terminology,

… the ideas of economists and philosophers, both when they are right and when they are wrong, are more powerful than is commonly understood. Indeed, the world is ruled by little else. Practical men, who believe themselves to be quite exempt from any intellectual influences, are usually the slaves of some defunct economist. Madmen in authority, who hear voices in the air, are distilling their frenzy from some academic scribbler of a few years back. I am sure that the power of vested interests is vastly exaggerated compared with the gradual encroachment of ideas. Not, indeed, immediately, but after a certain interval … [S]oon or late, it is ideas, not vested interests, which are dangerous for good or evil.[2]

The flow of ideas in Keynes’s view goes from “defunct economists”, to “academic scribblers”, to “madmen in authority” (presumably politicians), and finally to “practical men” and “vested interests.” Keynes likewise is quite vague about the time required for ideas to go from “scribbler” to “vested interests”, saying merely “after a certain interval”, or “sooner or later”.

What I would like to do is to offer some specific historical examples of such transmission of ideas and to use the Hayekian theory of capital structure to help explain the process by which this transmission occurs, and the types of people involved in it. This involves the identification of at least 4 stages or “orders” in the production of ideas from “high theory” to the “consumption” of (or, rather, the acting upon) those ideas by ordinary individuals; as well as the role played by key individuals such as “investors”, “entrepreneurs,” and “sales people,” and the different kinds of “idea factories” in which they work.

In my work exploring the history of classical ideas and movements I was struck by certain similarities between how ideas were developed, funded, spread, and put into practice, and Austrian capital theory, in particular the Hayekian notion of the structure of production of goods. The classical liberal movements I am most interested in are the following:

- the Leveller movement during the revolution in England during the 1640s

- the the Anti-Corn Law League in the late 1830s and early 1840s

- the Political Economists in the Guillaumin circle in Paris during the 1840s

- the activities of the Institute of Economic Affairs in London in post-war Britain

- the activities of the Institute for Humane Studies since its founding in 1961

- the activities of Liberty Fund since its founding in 1960 (the semicentenary of both the LF and the IHS in 2010/11 were opportunities for reflection on this topic)

- the rise of the modern libertarian movement since the late 1960s in which I have personally participated and taken a great interest

In these movements I noticed several things which they had in common: time, cost, coordination and entrepreneurship, sales and marketing, and consumption.

Time. Firstly, it took a long time between the appearance of a work of theory which set down the basic principles of key liberal ideas (such as Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations in 1776) and the putting into practice of reforms based upon those ideas (such as the repeal of the protectionist Corn Laws in 1846).

Cost. Secondly, it was costly to develop, spread, and put into practice (“sell”) ideas. Scholarly work had to be funded; books had to be printed, sold, and distributed to readers; ideas had to be popularised by being put into a form which could be understood by ordinary readers; these ideas had to be discussed and then accepted by people who had political or social influence; laws had to be drafted, discussed in Parliament, and then enacted; and then in the democratic age, voters had to be persuaded to vote for politicians who would enact this legislation, and so on. Naturally, there were always opportunity costs involved in doing one thing rather than another, as well as the need to economise on the use of scarce resources.

Coordination and Entrepreneurship. Thirdly, there were individuals who gave money to fund the movement (“investors”) by subsidizing scholarly work, publishing firms, journals and newspapers, and political campaigns; there were editors, publishers, and other organisers who had the skills necessary to coordinate the many activities in which these movements were engaged, and who could identify gaps in the political market (unmet demand) and use their entrepreneurial skills to choose the right movement to act (political entrepreneurs).

Sales and Marketing. Fourthly, there were charismatic public speakers and influential writers who were able to package the theoretical ideas into a form which appealed to a mass audience.

Consumption. Finally, there were people who purchased the books and tracts, adopted these ideas, believed them to be true, and who wanted to see them put into practice (the “consumers” of ideas).

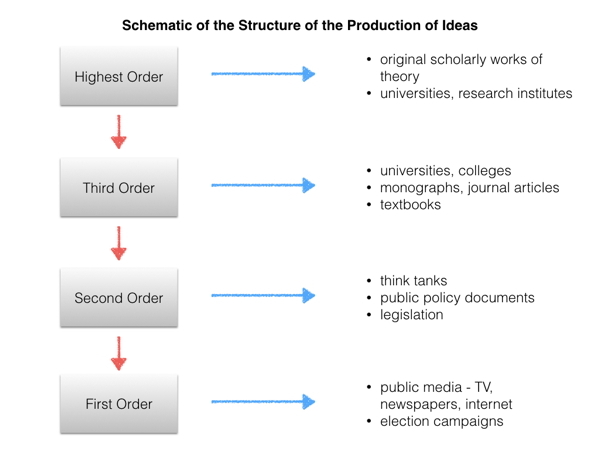

What struck me was the similarity this had to the Austrian theory of the structure of production of goods for final consumption. There seemed to be a long structure of production in the realm of ideas as there is for capital goods, with highest order goods (the production of high theory) most removed from ultimate consumption (politicians, ordinary people, voters), and with several middle order stages which serve as intermediary steps along the way (production of ideas for college professors, intellectuals, members of think tanks, journalists, and lobbyists), and then final consumers who consumed the product of this long structure of production.

There also seemed to be very similar groups of individuals involved in this process of production who served similar functions:

- investors with capital who invest in creating organisations to promote certain ideas,

- “entrepreneurs of ideas” who see opportunities for bringing together the right combination and mix of individuals with different talents to bring this about,

- managers who run the institutes, centres, lobby groups, and parties

- skilled intellectual workers who know how to produce the right kind of goods at each stage of production

- marketers and other promoters who are able to sell these ideas to a broader public, and finally

- the ultimate consumers of these ideas who accept them and act on them in some way.

Hence, I began thinking about the “the structure of production of ideas” (SPI) as a counterpart to “the structure of production of goods” (SPG).

Towards a Strategy for Achieving Radical Change↩

My research is a part of a broader project of thinking about strategies for achieving radical intellectual, economic, political, and social change, which is a topic which has been badly neglected by classical liberals and libertarians. We cannot hope to make sound decisions about how to change society in the present unless we are aware of the obstacles and costs which lie ahead of us. One way of identifying those obstacles and costs is to examine the efforts of previous attempts to introduce radical change, to see where they have succeeded and failed, and why, and to learn from them. This requires an historical awareness of the past efforts as well as a sound theory of the part played by ideas in bringing about change.

A short list of some of the most important historical attempts to change societies in radical ways (both pro- and anti-liberty), which we should study in detail, are the following:

- early Christianity up to when it became the state religion of the Roman Empire in 380 AD

- the spread of Islam

- the Reformation in the 16th century

- the Enlightenment in Europe and America in the mid- and late–18th centuries

- the movement to abolish slavery in the late 18th and early 19th centuries

- the free trade movement in the 1840s

- the spread of socialism and Marxism in the 19th and 20th centuries

- the rise of Nazism in the 1920s and 1930s

- the post-WW2 Classical Liberal movement

There is very little in the way of research on these movements by classical liberals, just as there has been very little self-reflection concerning the progress or lack thereof of the modern post-WW2 libertarian movement, especially at the time of key anniversaries in the movement, such as the 50th of Liberty Fund (1960–2010) and the IHS (1961–2011), or the 40th of Cato (1974–2014). Some of the very attempts to think about this are the following:

- Hayek’s pathbreaking essay “Socialism and the Intellectuals” (1949) written at the time of the founding of the Mont Pelerin Society and the renaissance of the classical liberal movement after WW2, in which he reflects on why socialist ideas had been able to achieve so much in 100 years or less.[3]

- Murray Rothbard’s long memorandum on strategy (1977) written at the time when the Cato Institute had been founded (1974) and when Rothbard was working within the Libertarian Party (founded 1971), and forming the Centre for Libertarian Studies (1976)[4]

- John Blundell’s book on “waging the war of ideas” (2001)[5]

- Edward Stringham on the strategy for academic change used by Peter Boettke[6]

- Ed Lopez book on “Academic Scribblers” (2013)[7]

- Richard Fink’s address at APEE 2015 on “Ideas into Action: Applying Hayek”[8]

Of course, there must have been discussions which took place behind closed doors at LF, IHS, Cato, and the Koch Foundation but these are not made public and very little is known about what they are thinking about these matters.

There have been other groups who have thought long and hard about strategies for achieving radical social change and whose activities would repay close attention by modern classical liberals. Three that come to mind are the American abolitionists in the 1840s and 1850s,[9] James Mill and his group of Philosophic Radicals in the 1820s and 18230s,[1] and Vladimir Lenin in the 1900s and 1910s.[2]

What the study of these past intellectual movements might tell us is how to “reverse engineer” them to our own advantage, that is what we might borrow, adapt, or improve upon for our own purposes.

We must of course be aware of the “central planning” fallacy, that is, that no “central committee” of the modern libertarian movement can plan the one and only correct method by which a free society might be achieved, but I think what we can learn is what not to do, and what doors might need to be opened so that others might march through them.

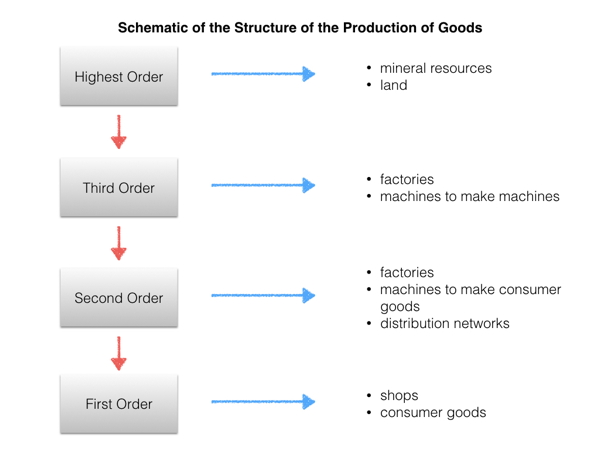

Austrian Capital Theory and the Structure of Production (of Goods)↩

An important part of Austrian capital theory developed by Hayek and Mises is the notion of “the structure of production of goods”.[10] One of Hayek’s and Mises’ great insights in the 1930s was that capital goods were not a uniform and undifferentiated mass but were tied to particular economic economic activities at various distances away from final consumption. These capital investments constituted a “structure” or “order” in that those activities furthest away from ultimate consumption (highest order goods) were required to produce the goods which economic activities which were closer to ultimate consumption needed to produce those final consumer goods (first order goods). Thus, crudely put, one needed to invest capital in mines to produce the raw materials to make capital goods (such as machines) which were used in the factories further along the structure of production which produced the consumer goods which were sold to consumers in the shops on main street. Capital which was invested in mine production was different from the capital used in factories which was in turn different from the capital required for distribution. It was not homogeneous as Keynesians believed and it could not be shifted easily, if at all, from one place to another. Furthermore, Hayek called those economic activities furthest away from ultimate consumption “highest order” production goods, those which constituted the factories making consumer goods “lower order” production goods, and so on as they got closer to ultimate consumption. The more sophisticated and complex an economy became the more “orders of production” there were and the longer the structure of production became. Each order of production required a different and more complex division of labour and this greatly increased the overall productiveness of economic activity.

As Mises explained in the opening chapters of Human Action:

Economic goods which in themselves are fitted to satisfy human wants directly and whose serviceableness does not depend on the cooperation of other economic goods, are called consumers’ goods or goods of the first order. Means which can satisfy wants only indirectly when complemented by cooperation of other goods are called producers’ goods or factors of production or goods of a remoter or higher order. The services rendered by a producers’ good consist [94] in bringing about, by the cooperation of complementary producers’ goods, a product. This product may be a consumers’ good; it may be a producers’ good which when combined with other producers’ goods will finally bring about a consumers’ good. It is possible to think of the producers’ goods as arranged in orders according to their proximity to the consumers’ good for whose production they can be used. Those producers’ goods which are nearest to the production of a consumers’ good are ranged in the second order, and accordingly those which are used for the production of goods of the second order in the third order and so on.[11]

For this structure of production of goods to exist, we need investors with a low time preference who are willing to invest their capital in the various higher order stages, we need entrepreneurs who can bring together the funds, skilled personnel, and managerial talent to produce the appropriate goods at each stage of production (the coordination process), and we need a sales force who can persuade consumers to buy their particular product from among all the others goods made by competitors, and ultimately we need consumers whose decisions to buy or not to buy determine the success of the entire structure of production.

The Structure of Production and Distribution of Ideas - an Austrian Analysis↩

I believe one can apply Hayek’s and Mises’ analysis to better understand the “production” and “consumption” of ideas, which in turn will help us understand how political change takes place.

Some Definitions

Let me offer a few definitions: by “production” of ideas I mean the creation of things which embody ideas such as books, articles, pamphlets, newspapers, magazine, literature, movies, art, and so on. By “consumption” of ideas I mean the understanding or appreciation of those ideas by others who read the books, see the images, or view the films. The “consumption” of ideas can be both passive and active; by “passive” the reader or viewer reads the book or sees the movie but does nothing further with the ideas other than “consume” them and move on to something else. By “active” I mean that the ideas stimulate the consumer to act upon them, to see the world in a different way, to change their behaviour in some way, to develop their own ideas based upon them, to vote for a different political party, to introduce legislation to change or repeal a particular law, or whatever. Although orders of production theoretically could extend to “n” levels, we will limit our discussion here to 4 orders or levels, with the 4th order being the highest.

Just as Austrian capital theory has a structure of production which has higher and lower orders, so too does the production of ideas. This is my schema of the order of the production of ideas and it ranges from “higher order” production of ideas (original scholarly work in high theory) to those groups who attempt to directly influence policy makers and voters (“middle orders”), and then the beliefs and activities of ordinary voters and citizens (“first order”). For each order of production I provide a description of its purpose, products, investment/capital required, audience, location, time frame, examples. The orders are the following:

- The Highest or Fourth Order of the Production of Ideas - the development of high theory

- Third Order Production of Ideas - the education of academics, intellectuals, and other informed members of the public

- Second Order Production of Ideas - influencing politicians and legislators

- First Order Production and Ultimate Consumption of Ideas - influencing ordinary people (citizens) who act on their beliefs or principles, or vote to elect particular political political parties or politicians

The Highest or Fourth Order of the Production of Ideas - the development of high theory.

The purpose of this stage of production of ideas is to further the development of libertarian/classical liberal economic, political, and social theory at a very original and high level. For example, an individual, like

- Saul of Tarsus (the Apostle) writes a series of letters about Christian doctrine to congregations and churches across the Greek world in 50–60 AD

- Adam Smith, develops a theory of how the free market functions and writes a book about it (The Wealth of Nations (1776))

- Karl Marx writes a multi-volume critique of capitalism, the 1st volume of which is published in 1867

- John Maynard Keynes writes The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money (1936) on how the government can use its control of interest rates, debt, and spending to control the business cycle

- Ludwig von Mises writes a massive treatise on the Austrian view of economic theory, Human Action (1949)

- James M. Buchanan, The Calculus of Consent: Logical Foundations of Constitutional Democracy (1958) creates a new school of economic thought which focuses on the selfish interests of politicians, bureaucrats, and other political actors.

- Murray Rothbard’s work on anarcho-capitalism which helped launch the modern libertarian movement in the late 1960s and early 1970s: Power and Market (1970) and For a New Liberty (1973)

This activity can take place privately or more commonly in the modern era in colleges and universities or research institutes. Scholars produce books and articles which are written for other scholars, they participate in conferences, they teach graduate students who do further research and then get jobs in academia or other institutions. These activities can take place virtually anywhere there are libraries and academic institutions or communities of scholars and intellectuals. The time frame for the production of these ideas can be very long term. It may take decades for a school of thought to emerge around the innovative work of a scholar or for academic books and articles to find an audience among other academics. Examples of scholars who would be considered part of this stage of production of ideas would be Hayek, Mises, and Buchanan. Examples of a “fourth order” organisation which deals with the production and distribution of ideas at this high level would be the William Volcker Fund in the 1950s and Liberty Fund since its foundation in 1960.

The highest order requires a high initial level of investment as it takes so long for a scholar to produce a seminal piece of work and it may take decades before it begins to show any impact on the thought and work of other scholars. In earlier periods, this investment may be self-financed by scholars who work on their own outside of any institutional setting (e.g. Adam Smith), or they might have wealthy aristocratic benefactors who support them financially (e.g. John Locke and the Earl of Shaftesbury). In the modern period, the production of high theory tends to be funded by universities which employ scholars to do research and publish their books and papers.

This level of production also requires the skills of an astute “entrepreneur of ideas” who can identify and fund potential scholars whose work might be transformative in the long run (the creation of endowed chairs at universities), a “board of directors” which has the patience and understanding to wait this long for a “return on their investment,” and a clever fund raising or original donor who sets up the foundation or centre (e.g. Charles Koch).

A few examples of “entrepreneurs of ideas” which come to mind are the 19th century French publisher Guillaumin who created the publishing firm which bore his name in 1837 and which lasted until 1907. It published most of the works by the political economists, including such seminal works as the massive Dictionnaire de l’économie politique (1852–3) as well as other large collections. Guillaumin was very good at spotting markets for economic books, organising teams of editors and writers for large projects, marketing his books cleverly, raising money from sympathetic business people, and keeping key works in print for long periods of time (like Bastiat’s complete works).[12]

A second is the financial support the wealthy manufacturer Friedrich Engels gave to the impecunious journalist Karl Marx while he was living in London and doing research on Das Kapital in the British Museum in the 1840s and 1850s.

Another is the activities of Harold H. Lunow who was head of the William Volcker Company and who established the William Volcker Fund after the Second World War. He had the entrepreneurial insight to fund the activities of Ludwig von Mises at NYU and Friedrich Hayek at the Committee for Social Thought at the University of Chicago who could not get paid academic positions at the time. The fund also paid Rothbard to write his economic treatise Man, Economy, and State (1962). All three men of course were vital in the development of the Austrian school of economics which appeared after the Second World War.[13]

A fourth example is Liberty Fund’s very strategic decision to publish the Glasgow Edition of the Works of Adam Smith (originally done by Oxford U.P.) in paperback and then putting it online for free. I believe this action was crucial in assisting the renaissance in Adam Smith scholarship which occurred in the last couple of decades of the 20th century.[14]

This raises the important question of how to measure the “return” on “investment” in this or any other order of the production of ideas in the absence of prices and profits. This is where my analogy between ideas and capital goods might break down. “Success” might be measured in book sales, the number of citations of the books in journal articles, favourable reviews in journals, the number of panels and papers given at professional conferences, or other such “metrics”.

Third Order Production of Ideas - the education of academics, intellectuals, and other informed members of the public.

The purpose of this stage of production of ideas is to influence the next generation of students, scholars, journalists, policy makers, and the thinking general public with the theoretical ideas produced in the “Fourth Order”. This stage also takes place in colleges and universities where courses are taught and degree programs offered. It can also take place in institutes and other educational organisations. The products they create are things like degrees, graduate programs, conferences and seminars for academics and students, magazines and journals, websites and blogs. The consumers are other educators, students, journalists, policy makers, and lobbyists. Many of these institutions are to be found in the capital or “imperial city”, near major transport hubs for ease of communication (for things like conferences). The time frame is medium to short term. Examples: IHS, FEE, Independent Institute, Atlas Foundation, Students for Liberty.

The “entrepreneurs of ideas” required for this order include people like heads of academic departments, directors of research programs, heads of campus institutes, inspirational college teachers, professional journal editors, presidents of professional associations, and so on. The return on investment can be measured in the number of students who graduate, the number of articles published, the number of pro-liberty faculty appointments, and so on. Funding comes mainly from universities and colleges which raise money privately and via the government. Wealthy individuals also fund endowed chairs and campus-based research centres.

Second Order Production of Ideas - influencing politicians and legislators.

The purpose of this stage of production of ideas is to influence the formation and direction of current policy development and relevant legislation within the Legislature or Parliament. The institutions at this order include policy research centres like the IEA, Cato, at the national level and other state-based policy centres, as well as political parties. These groups produce journals, policy papers, presentations to Congress or Parliament, lobbying, and conferences and seminars. Their “consumers” are politicians, journalists, lobbyists, members of political parties, and some well-informed voters. They too are often found in the capital or imperial city. The time frame is the short term, the next one or two election cycles. Examples of these kinds of institutions are Cato, Mercatus, Libertarian Party, the Tea Party movement.

Entrepreneurs required at this level include directors of centres, senior policy experts, academic advisors, and free lance writers and researchers. Funding comes primarily from donations with some money coming from sale of publications which means that a key entrepreneur of ideas at this level also has to have skills in fund raising from sympathetic individuals in the private sector. The return of investment includes things like bad legislation which gets blocked, new good legislation which gets passed, the number of op eds which get published, the sale and distribution of policy papers and other kinds of applied research, the number of politicians who are sympathetic and who cite the institute’s research in their speeches, etc.

First Order Production and Ultimate Consumption of Ideas - influencing ordinary people who act on their beliefs or principles.

The purpose of this stage of production of ideas is provide the ideas which motivate some people to take direct action of some kind. At the political level it might take the form of changing the way people vote in elections or in referendums; organising people to sign petitions or “write their congressman” in favour of new pieces of legislation or repeal of legislation; to attend meetings or rallies; to join protest marches against specific policies or activities of the state; to exercise civil disobedience and be willing to go to jail for their beliefs. Examples of this include the Anti-Corn Law League, Julian Assange, Chelsea Manning, the Ron Paul movement

The “entrepreneurs” suitable for this order of production include “charismatic” political leaders who can attract people to political rallies and take part in voting in elections (Ron Paul); organising and getting people to attend political rallies and protest marches; inspiring individuals who can take “direct action” and inspire other people by their activities. The return on investment for this order of production is perhaps the easiest to quantify: votes in elections, attendance at rallies and protests; the results of opinion polls.

Two Alternative Perspectives: “Applied Hayek” and “Academic Scribblers”

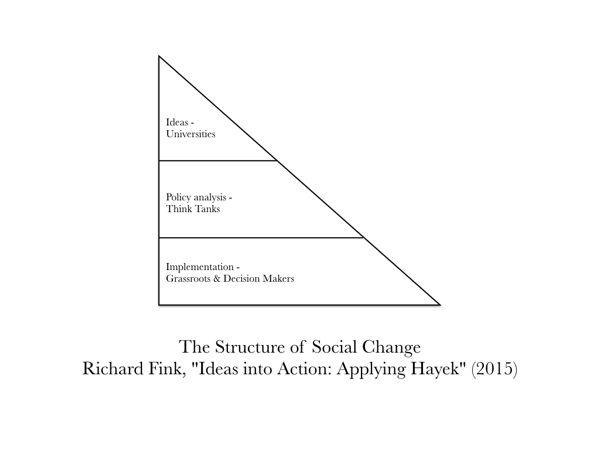

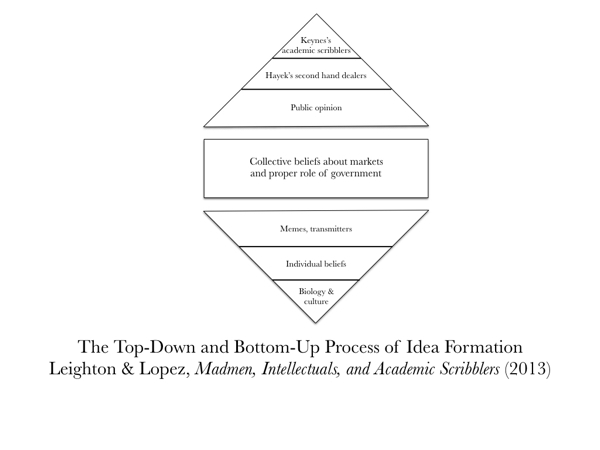

I would like to draw your attention two other recent attempts to describe the structure of the production of ideas done by Richard Fink (2015) and Leighton & Lopez (2013).

Richard Fink has a tripartite division of production from universities at the top which produce “ideas”, think tanks in the middle which produce “policy analysis”, and at the bottom is the “implementation” of these ideas by grassroots supporters and “decision makers.” This was presented as a Plenary Speech at this year’s APEE conference on the topic of “Ideas into Action: Applying Hayek”.[15]

Leighton & Lopez devote an entire chapter to “How Ideas Matters for Political Change” in their delightful book Madmen, Intellectuals, and Academic Scribblers.[9] This is quite close to my own “Austrian capital theory” approach although they differ in trying to explain how ideas “bubble up” from below, as well as “trickle down” from the top (which is my main focus).

Summary

I would summarize my idea of the “structure of production and distribution of ideas” as follows:

- the highest order of production of ideas (intellectual goods) involves the production of “high theory” and is the most removed from the ultimate “consumption” of ideas by politicians, ordinary people, and voters)

- there are several middle order stages (3rd and 2nd orders) which serve as intermediary steps along the way. Here we see the production of ideas for college professors, intellectuals, members of think tanks, journalists, politicians, and lobbyists.

- the lowest order of production is where the final product (ideas) gets into the hands of consumers (citizens) and “consumed” (accepted, understood, and acted upon).

Each order of production requires people with different sets of skills in order for the “investment production line” to be successful and the final product to get into the hands of consumers:

- there need to be far-sighted and astute investors with the right time preference who invest their capital in creating organisations to support and encourage the development of ideas by original thinkers

- “entrepreneurs of ideas” who see opportunities for bringing together the right combination and mix of individuals with different talents to produce the correct output

- managers who run the institutes, centres, lobby groups, and parties

- skilled intellectual workers who know how to produce the right kind of goods at each stage of production

- marketers and other promoters who are able to sell these ideas to a broader public, and get them into their hands/minds

- and perhaps most importantly, there have to be the ultimate consumers of these ideas who accept them and act on them in some way.

We should also note that for societies to change in the way would like them to (i.e. not randomly) we need a long structure of production of classical liberal ideas which is integrated with all its component parts working properly. For example, we could envisage a society in which there is a Fourth Order of production where original and very liberal “high theory” is constantly being produced by gifted scholars but without the lower orders of production, these ideas never get into the hands or minds of journalists, elected politicians, or to the ordinary people and voters. We could also imagine a structure of production where there is no Fourth Order where no new liberal ideas are being produced at all, but where liberal-minded professors and teachers only pass on the revered “classics” to their students. One could easily imagine the students becoming bored with this and moving on to new and more interesting ideologies, such as equality and environmentalism, or whatever.

Some Historical Examples↩

Introduction

The following is a rough list of some historical examples of the different kinds of people who are required for ideas to be “produced” and then “consumed” and who were active in promoting ideas about individual liberty:

- theorists - individuals who are capable of supplying the intellectual raw materials (the theory of liberty as applied to economics, politics, and society)

- Ludwig von Mises, Human Action (1949)

- James M. Buchanan, The Calculus of Consent (1958)

- Friedrich Hayek, The Constitution of Liberty (1960)

- Murray Rothbard, Power and Market (1970) and For a New Liberty (1973)

- investors who are willing to provide the financial means for these ideas to be produced and distributed to others

- Harold Luhnow and the William Volker Fund

- Antony Fisher and IEA and Atlas

- Pierre Goodrich and Liberty fund

- Charles Koch and Cato Institute and other groups

- entrepreneurs who can identify a market opportunity (a “strategic issue”) and can organise all the components needed for the production and distribution of ideas for different types of markets (scholarly, general interest, education, mass market)

- Thomas Clarkson: the British Anti-Slavery movement

- Guillaumin: the French political economists

- Richard Cobden: the English free trade movement

- Arthur Seldon and Ralph Harris: the IEA in London

- Leonard Read: FEE

- Baldy Harper: IHS

- Antony Fisher: IEA and Atlas

- Ed Crane: Cato Institute

- a salesforce (marketers, advertisers, salespeople) who can persuade the consumers of ideas to buy this particular product in a competitive market for ideas

- Frédéric Bastiat: free trade journalism

- Ayn Rand: best-selling novels

- Milton Friedman: “Free to Choose” TV series and book

- Ron Paul: presidential campaign

Side Bar: “Hart’s 70 Year Rule”

An obvious question presents itself - how long does it take (has it taken in the past) between the creation of a key work of theory and the appearance of political changes brought about because of these ideas? I propose “Hart’s 70 Year Rule” to describe a pattern I have observed.

- Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations (1776) and the repeal of the Corn Laws in 1846 - 70 years exactly

- J.B. Say’s Traité de l’économie politique (1st ed. 1803); Cobden-Chevalier Free Trade Treaty between France and England 1860 - 57 years

- Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels Communist Manifesto (1848) and the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917 - 69 years (or perhaps Capital vol. 1 (1867) - 50 years)

- the collection of Fabian Essays in Socialism edited by George Bernard Shaw (1889) and the creation of the welfare state in Britain following WW2 (1945) - 66 years

This raises another question concerning the relative lack of influence some modern key classical liberal or libertarian texts have had, such as:

- Ludwig von Mises, Human Action (1949)

- F.A. Hayek, The Constitution of Liberty (1960)

- Murray N. Rothbard, Man Economy and State (1962) and *For a New Liberty * (1973)

Some Historical Examples

Of the many historical examples one could select, these are three I think are particularly noteworthy:

- the Anti-Corn Law League in the early 1840s,

- the Political Economists in Paris during the 1840s, and

- the activities of the Institute of Economic Affairs in London in post-war Britain

Further information about these can be found in the relevant Liberty Matters Online Discussion Forums or in other works I have written on the French classical political economists, such as Frédéric Bastiat and Gustave de Molinari.[16]

Historical Example 1: the Anti-Corn Law League in the early 1840s

I would now like to show how this “structure of the production of ideas” can be applied to a specific historical case study, namely the Anti-Corn Law League 1838–1846.[17]

Fourth Order: the intellectual groundwork for free trade was done by Adam Smith in The Wealth of Nations (1776). This theoretical work was continued by many other classical economists in the early part of the 19th century like David Ricardo, James Mill, and J.R. McCulloch where the idea of free trade became a core component of the classical school of economics.

Third Order: Classical economists gave lectures and wrote books and pamphlets on free trade; people like Thomas Hodgskin gave lectures to popular audiences at Mechanics Institutes and published books; Thomas Peronnet Thompson wrote books and pamphlets for middle brow audiences; Wilson created the magazine The Economists to lobby for free trade ideas.

Second Order: Members of the Board of Trade had become influenced by Smithian ideas, there were sympathetic MPs in the Tory party who were prepared to argue in favour of free trade in the Commons and to vote for the repeal of the Corn laws, the Prime Minister Robert Peel was won over to the free trade cause and organised a vote on it.

First Order: Cobden’s genius was to see how ordinary people could be organised to put pressure on the government. He created membership cards for the ACLL so people could show their allegiance; letter envelopes with ACLL designs and slogans; bazaars to sell ACLL merchandise; signature drives to demonstrate scale of public support to MPs; large public meetings; wide distribution of magazine and pamphlets.[18]

I do not believe that this structure of production of ideas was a deliberate creation of any one of the individuals involved in the free trade movement. It seemed to have evolved without a great deal of conscious strategic planning on Cobden’s part (although I could be wrong).

According to my schema we can identify the following key roles:

- the creator of the “raw materials”: Adam Smith in his treatise The Wealth of Nations, and his followers in the Classical school of economics

- the investors: Richard Cobden and his fellow cotton manufacturers who funded the organisation

- the entrepreneurs: Cobden was very good at identifying legislative opportunities for the free traders, and showed great skill in designing the best way to market the ideas to the general public (the symbol of the “big loaf” vs. “the small loaf”; James Wilson who founded The Economist magazine in 1843 to spread free market ideas

- the salesforce: lecturers like Hodgskin, Thompson; politicians like Villiers and Cobden who gave speeches in the house; the journalists who wrote articles the magazine The League

- the consumers: those ordinary people who voted for free trade candidates; signed petitions to parliament; attended large public meetings in support of free trade

Where Cobden did come into his own was with some of the propaganda activities of the First Order. For example, he did play a part in designing some of the images used very effectively the the ACLL, such as the free trade “Big Loaf” vs. the protectionist “Small Loaf”: imagery. The question we might ask ourselves, is whether or not a structure of the production of ideas like this is necessary for any significant intellectual and social/political/economic change to occur? How many examples can we find from history where something like this structure appeared, and how many took place without this kind of structure? If we can, how do explain the creation, dissemination, and impact of ideas in those cases?

A further question to consider is how long it takes for ideas to move from the Highest Fourth stage of high theory production to the first stage where the ideas get put into practice and pro-liberty reforms are enacted. In the case of free trade there was a 70 year period between the publication of Smith’s Wealth of nations (1776) and the repeal of the Corn Laws in 1846. I like to call it the “Hart 70 Year Rule”. Is this a typical time frame? What other examples can historians find?

One might get depressed if one counted the years since the appearance of Mises’ Human Action in 1949 (65 years) and the current state of monetary and banking policy in the West. On the other hand, the appearance of Rothbard’s For a New Liberty in 1973 and the growth of the modern libertarian movement 40 years later, one might be more optimistic. Another example of a very fast adoption of ideas was the time between the publication of Keynes’ General Theory (1936) and the adoption of Keynesian policies in the immediate post-war period.

Historical Example 2: the Political Economists in Paris during the 1840s

In progress. In the meantime, see my personal website for further information: essays on Bastiat and Molinari at my personal website Reflections on Liberty and Power http://davidmhart.com/wordpress/.

Summary of the Structure of Production of Ideas

- Fourth Order (high theory): very few academic posts were available to the economists

- Collège de France, Athénée royale;

- French Academy (Académie des sciences morales et politiques (the Academy of Moral and Political Sciences)) had several economists and classical liberal historians after its refounding in 1832

- In January 1847 the membership of the 2nd section (Morale) included Dunoyer (1832), Droz (1832), Lucas (1836), Toqueville (1838), Beaumont (1841), and Alban de Villeneuve (1845). The 4th section (Économie politique et Statistique) had as full members - Dupin (1832), Villermé (1832), Rossi (1836), Blanqui (1838), Passy (1838), and Duchatel (1842). Bastiat was made a “corresponding” (or junior) member of the 4th section on 24 January, 1846

- leading theorists: Charles Dunoyer, Michel Chevalier, F. Bastiat, Gustave de Molinari

- Third Order (education): Urbain Guillaumin was the key entrepreneur of ideas;

- he founded Guillaumin publishing firm in 1837;

- the creation of Political Economy Society in 1841;

- the Journal des Économistes in 1842

- Second Order (pubic policy, legislation): there was a small but very vocal and well organised group of classical liberal politicians in the Chamber of Deputies (Léon Faucher, Bastiat, Louis Wolowski); Bastiat in Finance Committee

- First Order (public media, elections):

- free trade campaign 1846–48 with French Free Trade Association and Le Libre-Échange magazine;

- anti-socialist pamphlet campaign 1848–50

- journalists who wrote for Le Courrier français, Journal des Débats, street magazines (Jacques Bonhomme)

Summary of Key Roles

- theorists - individuals who are capable of supplying the intellectual raw materials (the theory of liberty as applied to economics, politics, and society)

- J.B. Say, Charles Comte, Charles Dunoyer, Frédéric Bastiat, Alexis de Tocqueville, Gustave de Molinari

- investors who are willing to provide the financial means for these ideas to be produced and distributed to others

- the publisher Urbain Guillaumin, the merchant and businessman Horace Say, the manufacturer Casimir Cheuvreux

- entrepreneurs who can identify a market opportunity (a “strategic issue”) and can organise all the components needed for the production and distribution of ideas for different types of markets (scholarly, general interest, education, mass market)

- Guillaumin was the key figure who organised the “Guillaumin network” in Paris from the late 1830s to the 1860s, he brought together for discussions theorists, politicians, senior bureaucrats, journalists, and businessmen

- a salesforce (marketers, advertisers, salespeople) who can persuade the consumers of ideas to buy this particular product in a competitive market for ideas

- Frédéric Bastiat was probably the best economic journalist who has ever lived, his work debunking protectionism and socialist in the late 1840s was very popular and sold well throughout Europe

Historical Example 3: the activities of the Institute of Economic Affairs in London in post-war Britain

In progress. In the meantime, see the Liberty Matters Online Discussion Forum John Blundell, “Arthur Seldon and the Institute of Economic Affairs” (November, 2013) http://oll.libertyfund.org/pages/seldon-and-the-iea.

Historical Example 4: the Current Structure of the Classical Liberal/Libertarian Movement

Another set of historical examples I would like to look at are the pro-free market, individual liberty groups which emerged in the West after World War Two, especially to examine what order of production they fit into, to see what orders of production are missing or were ignored, and what impact this might have had on the development of liberty during this period.

Since the renaissance of classical liberal thought in the post-WW2 period we have seen several waves or generations of libertarian organizations. They were founded with specific people and issues in mind, and their ideological opponents varied according to the historical circumstances. I think we can identify at least 4 generations of classical liberal or libertarian intellectual and political activity:

- First Generation - the 1940s

- Second Generation - the 1950s & 1960s

- Third Generation - the 1970s & 1980s

- Fourth Generation - the 2000s

And these can be categorised into the following “orders of production of ideas”. What is clearly apparent is the rather chaotic and “unplanned” nature of these activities:

- First Generation - the 1940s

- Mises seminar at NYU, 4th and 3rd order

- Mont Pelerin Society, 1947, Hayek & Friedman et al., remnant of liberals in academia and media, revival and rebirth of movement, 4th and 3rd order

- Foundation for Economic Education, 1946, Leonard Read, remnant of liberals in academia and media and general population, revival and rebirth of movement, 2nd and 1st order

- Second Generation - the 1950s & 1960s

- Liberty Fund, 1960, Pierre Goodrich, 4th order

- Institute for Economic Affairs, 1955, Anthony Fisher, 3rd and 2nd order

- IHS, 1961, F.A. Harper, 3rd and 2nd order

- Ayn Rand and the Objectivist movement, 3rd and 2nd order

- Third Generation - the 1970s & 1980s

- The Libertarian Party (US) 1971, 1st order

- Fraser Institute, 1974, Walker, politicians and journalists and general public, 3rd and 2nd order

- Centre for Independent Studies, 1976, Greg Lindsay, politicians and journalists and general public, 3rd and 2nd order

- Cato Institute, 1977, Ed Crane (Murray Rothbard), politicians and journalists and general public, 3rd and 2nd order

- Center for the Study of Market Processes (Mercatus), 1980, Richie Fink and Charles Koch, graduate students and politicians and journalists and general public, 3rd and 2nd order

- Atlas Foundation, 1981, Anthony Fisher, activists and intellectuals who want to start their own free market think tanks, “meta–2nd order” (designed to create other 3rd and 2nd order institutions)

- Mises Institute, 1982, Lew Rockwell & Rothbard, academics and students and general public interested in Austrian school, 3rd, 2nd, and 1st order

- Fourth Generation - the 2000s

- Freedom Fest, 2002, Mark Skousen, general public and broader libertarian movement, general education and movement building, 2nd and 1st order

- Students for Liberty, 2008, college students, education of college students about liberty and to encourage campus activism, 2nd and 1st order

- Ron Paul movement, 2011–12, Ron Paul et a., students and younger voters in all parties, influence policy direction in existing political parties and political activism, 2nd and 1st order

In conclusion, we should ask ourselves if any type of order of production is over-represented or missing from the overall structure of production of ideas which we have seen since WW2 in the above list. There seems to be only a handful of Fourth Order institutions, but this might be as it should, as they are highly specialised and only supply a niche market. There seems to be a large number of 3rd and 2nd order organisations which focus on policy work and influencing the legislators. The number of First Order groups has been very low, which might reflect the youth and relative immaturity of the modern movement, or my lack of knowledge of this sector of activity. However, the number seems to have increased in recent years with the emergence of the Ron Paul movement in or just outside the Republican Party and the activities of Students for Liberty. One might have expected over time to see a more pyramidal structure with a small number of 4th order institutions at the top and the largest number of 1st order groups at the bottom.

Further Thoughts and Some Questions and Complications to Consider↩

Mises on Ideas and Interests: or Interests as Ideas

I would like to briefly discuss Ludwig von Mises’ key idea that our economic “interests” (in fact all our "interests) are in large part determined by the ideas we hold about what those interests are and how we can best go about satisfying them. Mises developed this important insight in the chapter “Ideas and Interests” in Theory and History (1957):

In the world of reality, life, and human action there is no such thing as interests independent of ideas, preceding them temporally and logically. What a man considers his interest is the result of his ideas.[7]

According to this view, the economic, political, and other interests which people pursue (whether ordinary people or ruling elites) depend upon the ideas they have about what their interests are. Mises went on further to say about the relationship between ideas and interests:

If we keep this in mind, it is not sensible to declare that ideas are a product of interests. Ideas tell a man what his interests are. At a later date, looking upon his past actions, the individual may form the opinion that he has erred and that another mode of acting would have served his own interests better. But this does not mean that at the critical instant in which he acted he did not act according to his interests. He acted according to what he, at that time, considered would serve his interests best.[8]

Ideas, interests, and history play an important role in Mises’s theory of “praxeology,” which he defined as “the general theory of human action,” by which individuals undertake “purposeful behavior” in order to pursue their interests and to achieve their goals or ends.[19] History in Mises’s view was the second main branch of the science of human action after economics. He defined the relationship between the two as follows:

There are two main branches of the sciences of human action: praxeology and history. History is the collection and systematic arrangement of all the data of experience concerning human action. It deals with the concrete content of human action. It studies all human endeavors in their infinite multiplicity and variety and all individual actions with all their accidental, special, and particular implications. It scrutinizes the ideas guiding acting men and the outcome of the actions performed. It embraces every aspect of human activities.[20]

If this Misesian insight into the fundamental basis of human action is correct, then the historian of ideas and social change needs to ask a number of questions about three important groups of people, namely ordinary people, intellectuals, and members of the ruling elite:

- What ideas did this group hold about politics, economics, and social organization?

- Where did they get these ideas from?

- Why and under what circumstances have they changed their ideas, especially about their own interests?, and

- What is the best way to persuade them to hold more pro-liberty ideas about these things?

But these questions can wait for another time.

Hayek on Utopias and History

Is the difference between the success of socialism and the failure of classical liberalism due to the lack of a “utopian vision” as Hayek argues in “The Intellectuals and Socialism” in 1949?[21] Do liberal theorists need to have “the courage to be utopian?”

Is Hayek correct to say that the study of history (and hence, its writing from a classical liberal perspective) is vital because most people get their understanding of economics from the history they learnt at school? See his collection on Capitalism and the Historians (1954).[22]

“Malinvestments” and the Distortion of the SPI

One might ask whether the state will inevitably distort this structure of the production of ideas, just as it distorts the investment of capital in the structure of production of economic goods by manipulating interest rates and the money supply? I do not have space to go into this question here, other than to suggest that the biggest distortion it creates is the supply of government schools and universities which “crowd out” both private suppliers of educational services, but perhaps more importantly, crowds out “unwelcome ideas” which support the free market and individual liberty. It also “over invests” in research which one would not expect to see funded in a fully free market society, such as nuclear weapons research, the training of economics PhDs to work in the Federal Reserve banking system, paying academic anthropologists and psychologists to advise on how the government can better control subject people (such as in Vietnam) or torture captives without killing them (Iraq war).

We need to study the impact government funding and/or monopoly has had on the following institutions which produce and disseminate ideas:

- state funded public eduction (schools and colleges)

- state funded research in some areas (atomic energy, MIC)

- state public broadcasters (BBC, ABC)

- subsidies to promote national culture (film production)

- tax breaks for one group (US churches tax free but not other groups)

Do we have as a consequence the “overproduction” of higher education or just a “distortion”?

The Internet and the changing Relative Costs of the Production and Distribution of Ideas

In the Liberty Matters online discussion of Jeffrey Tucker correctly points out that a key component in the dissemination of ideas is the cost of their production, duplication, and transmission of those ideas.[23] We are living through a period which has seen an extraordinary reduction in the price of these things as a result of computers and the Internet and we have witnessed the way classical liberals and libertarians have made use of these to advance their causes. However, we should not exaggerate their importance for two reasons: first, similar revolutionary changes in the cost of production of ideas have occurred in the past, and second, these changes affect all participants.

As for the first point, similar instances of technological changes which lowered costs include the invention of moveable type printing in the 15th century which was a major factor contributing to the spread of new religious ideas known as the Reformation; the introduction of the uniform penny post in England in 1840, which lowered the cost of sending material through the mail and which was quickly adopted by the Anti-Corn law League to disseminate its free trade literature; the new technologies of paper production and steam-powered printing presses in the 19th century which lowered the cost of printing books and newspapers for a mass market, permitting several liberal authors, including Harriet Martineau (1802–1876), to become full-time, professional popularizers of free-market ideas;[24] and the mass production of radios in the 1920s and 1930s, which enabled charismatic politicians like Adolf Hitler and Franklin Delano Roosevelt to speak directly to millions of people in order to promote their political agendas. (It is curious that no classical-liberal individual or group took advantage of the radio to spread liberal ideas - perhaps this kind of mass medium is not suited to their spread).

Secondly, the lowering of the cost of production of ideas affects not only classical liberals but all groups that wish to disseminate their ideas. A brief advantage may be had by those who use new technology first, but after a while everybody takes advantage of it. As an aside, the Internet was created as a byproduct of military research undertaken by DARPA, the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, and was first used by researchers funded by the military who wished to share large amounts of data across the country. An early user of the internet for civilian purposes was the pornography industry, which quickly realized its potential and made important innovations in software such as the “shopping cart,” for online purchasers. The danger is that, once again liberal ideas will get crowded out of the market place of ideas with millions or hundreds of millions of producers trying to hawk their goods and services at the same time. The market has gown, but the relative scarcity of liberal ideas, especially in politics and popular culture, remains the same I would say. Examples of other groups that have taken advantage of the lower costs would include the well-organised campaigns which helped Barack Obama get elected, the Occupy Wall Street movement, and the network of Jihadi groups.

The Relative Costs of changing Core vs Non-Core Beliefs: or, it is always cheaper at the margin

Also in the Liberty Matters discussion George Smith raised the issue of the relative costs of changing “core beliefs” compared to changing “non-core beliefs”. By “core belief” (or, as George Smith points out, what J.M. Robertson called “major beliefs”), I mean any idea which is fundamental to a person’s or a society’s Weltanschauung, or overall system of belief. For a traditional Catholic or a fundamentalist Protestant a core belief is the idea that marriage must be between a man and women. For a Keynesian it is the idea that “aggregate demand” exists and that when it falls below a certain level it is the right and duty of the government or central bank to manipulate the interest rate and the supply of money to “stimulate” it back up to an acceptable level. To give up this belief would mean giving up their entire worldview, and this they will not do easily. In fact, they would spend considerable resources defending this view and opposing any challenge to it.

By “noncore beliefs” (or what Robertson called “minor beliefs”), I mean beliefs which do not define a person or a society. As such, they are less important to you and you might be interested in discussing them with others, listening to challenges to their truth or efficacy, and even giving up belief in them if your preferences were to change or if you could be bought off in reaching a compromise. An example of this is the recent growing acceptance of same-sex marriage. For an increasing number of younger people the idea of marriage as only between a man and a women is noncore, rather than a core, belief. Thus they are willing to entertain the idea that laws should be changed to allow state recognition of same-sex marriages. What seemed impossible 50 years ago (because the vast majority of Americans regarded “traditional” marriage as a core Christian belief) is now, through a process of generational and demographic change, becoming a reality.

The implications of seeing ideas and belief structures in this light are the following:

- It is costly to change people’s core beliefs because they are essential to those peoples’ sense of who they are.

- It is less costly to change people’s noncore beliefs or at least to persuade them to compromise or modify them somewhat in the face of growing opposition.

- Core beliefs do change but only slowly and at high cost. It might be a demographic matter, as younger people with different core beliefs begin to outnumber the older generation with a different set of core beliefs; or it might be the result of crises such as hyperinflation, defeat in war, or even revolution. The possibility of any intellectual movement, whether Marxist or classical liberal, being able to achieve change though the “mass conversion” of people from one set of core beliefs to another set is extremely unlikely.

- It is less costly to work at gradually changing people’s noncore beliefs, in other words, fighting the intellectual battles on the margin.

- Any intellectual movement still needs a growing number of people who share its core beliefs if it is to grow and prosper.

Bibliography of Works Cited↩

John Blundell, Waging the War of Ideas. Fourth edition. (London: The Institute of Economic Affairs, 2001, 2015).

John Blundell, “Arthur Seldon and the Institute of Economic Affairs,” Liberty Matters (November, 2013) http://oll.libertyfund.org/pages/seldon-and-the-iea.

Stephen Davies, “Richard Cobden: Ideas and Strategies in Organizing the Free-Trade Movement in Britain,” Liberty Matters (January 2015) http://oll.libertyfund.org/pages/lm-cobden.

Brian Doherty, Radicals for Capitalism: A Freewheeling History of the Modern American Libertarian Movement (New York: Public Affairs, 2007).

Richard Fink’s Plenary Address, “Ideas into Action: Applying Hayek,” The Association of Private Enterprise Education, 40th Annual Conference, Cancun, Mexico, April 12–14, 2015.

Joseph Hamburger, Intellectuals in Politics: John Stuart Mill and the Philosophic Radicals (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1965).

David M. Hart, “On the Spread of (Classical) Liberal Ideas,” Liberty Matters (March 2015) http://oll.libertyfund.org/pages/lm-ideas.

David M. Hart, “Gustave de Molinari and the Seven Musketeers of French Political Economy in the 1840s” (June, 2015) http://davidmhart.com/liberty/Papers/Molinari/SevenMusketeers.html.

David M. Hart, an illustrated essay on “Cobden and the Anti-Corn Law League” http://oll.libertyfund.org/pages/cobden-and-the-anti-corn-law-league.

F.A. Hayek, “The Intellectuals and Socialism” (1949) in Studies in Philosophy, Politics, and Economics (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1967), pp. 178–94.

F.A. Hayek, The Pure Theory of Capital, Edited by Lawrence H. White. The Collected Works of F.A. Hayek (Indianpolis: Liberty Fund, 2007).

F.A. Hayek (ed.), “History and Politics,” in Capitalism and the Historians (University of Chicago Press, 1954).

John Maynard Keynes, The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money (New York: Harcourt Brace, 1936).

Aileen S. Kraditor, Means and Ends in American Abolitionism: Garrison and his Critics on Strategy and Tactics, 1834–1850 New York: Pantheon Books, 1969).

Wayne A. Leighton and Edward J. Lopez, Madmen, Intellectuals, and Academic Scribblers: The Economic Engine of Political Change (Stanford University Press, 2013).

Vladimir Lenin, What Is to Be Done? Burning Questions of Our Movement (1901, 1902). In Lenin’s Collected Works, Foreign Languages Publishing House, 1961, Moscow, Volume 5, pp. 347–530. https://marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1901/witbd/index.htm or PDF https://marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/download/what-itd.pdf.

Harriet Martineau, Illustrations of Political Economy (3rd ed) in 9 vols. (London: Charles Fox, 1832). http://oll.libertyfund.org/titles/1873.

Ludwig von Mises, Human Action: A Treatise on Economics, in 4 vols., ed. Bettina Bien Greaves (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 2007).

Ludwig von Mises, Theory and History: An Interpretation of Social and Economic Evolution, ed. Bettina Bien Greaves (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 2005). http://oll.libertyfund.org/titles/1464.

Murray N. Rothbard, For a New Liberty (New York: Macmillan,1973)

Murray N. Rothbard, Toward a Strategy for Libertarian Social Change (April, 1977). <davidmhart.com/liberty/OtherWorks/Rothbard/Rothbard_1977TowardStrategy.pdf>.

Murray Rothbard, “Strategies for a Libertarian Victory,” Libertarian Review, Special Issue on “Strategies for Achieving Liberty” Aug. 1978, vol. 7, no.7, pp. 18–24, 34. http://www.libertarianism.org/lr/LR788.pdf.

Murray N. Rothbard, Man, Economy, and State: A Treatise on Economic Principles, with Power and Market: Government and the Economy. Second edition. Scholar’s Edition (Auburn, Alabama: Ludwig von Mises Institute, 2009).

Stringham, Edward Peter. 2010. “Toward a Libertarian Strategy for Academic Change: The Movement Building of Peter Boettke.” The Journal of Private Enterprise 26(1) Fall: 1–12.

Endnotes↩

-

Joseph Hamburger, Intellectuals in Politics: John Stuart Mill and the Philosophic Radicals (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1965). ↩

-

Vladimir Lenin, What Is to Be Done? Burning Questions of Our Movement (1901, 1902). In Lenin’s Collected Works, Foreign Languages Publishing House, 1961, Moscow, Volume 5, pp. 347–530. https://marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1901/witbd/index.htm or PDF https://marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/download/what-itd.pdf. ↩

-

F.A. Hayek, “The Intellectuals and Socialism” (1949) in Studies in Philosophy, Politics, and Economics (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1967), pp. 178–94. ↩

-

Murray N. Rothbard, Toward a Strategy for Libertarian Social Change (April, 1977). <davidmhart.com/liberty/OtherWorks/Rothbard/Rothbard_1977TowardStrategy.pdf> ; and Murray Rothbard, “Strategies for a Libertarian Victory,” Libertarian Review, Special Issue on “Strategies for Achieving Liberty” Aug. 1978, vol. 7, no.7, pp. 18–24, 34. http://www.libertarianism.org/lr/LR788.pdf. ↩

-

John Blundell, Waging the War of Ideas. Fourth edition. (London: The Institute of Economic Affairs, 2001, 2015). ↩

-

Stringham, Edward Peter. 2010. “Toward a Libertarian Strategy for Academic Change: The Movement Building of Peter Boettke.” The Journal of Private Enterprise 26(1) Fall: 1–12. ↩

-

Ludwig von Mises, Theory and History: An Interpretation of Social and Economic Evolution, ed. Bettina Bien Greaves (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 2005). http://oll.libertyfund.org/titles/1464#Mises_0844_324. ↩

-

Mises, Theory and History http://oll.libertyfund.org/titles/1464#Mises_0844_320. ↩

-

Wayne A. Leighton and Edward J. Lopez, Madmen, Intellectuals, and Academic Scribblers: The Economic Engine of Political Change (Stanford University Press, 2013), chapter 5 “How Ideas Matters for Political Change”. Graphs are on pp. 119, 132. ↩

-

F.A. Hayek, The Pure Theory of Capital (1941) and Ludwig von Mises, Human Action (1949). ↩

-

Mises, Part I. Human Action. “CHAPTER 4: A First Analysis of the Category of Action”, in Human Action: A Treatise on Economics, in 4 vols., ed. Bettina Bien Greaves (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 2007). Vol. 1. http://oll.libertyfund.org/titles/1893#Mises_3843-01_388. ↩

-

On the importance of the “Guillaumin network” in Paris see, David M. Hart, “Gustave de Molinari and the Seven Musketeers of French Political Economy in the 1840s” (June, 2015) http://davidmhart.com/liberty/Papers/Molinari/SevenMusketeers.html. ↩

-

See the many references to the Volcker Fund in Brian Doherty, Radicals for Capitalism: A Freewheeling History of the Modern American Libertarian Movement (New York: Public Affairs, 2007). ↩

-

Private conversations with Liberty Fund staff. ↩

-

Richard Fink’s Plenary Address, “Ideas into Action: Applying Hayek,” The Association of Private Enterprise Education, 40th Annual Conference, Cancun, Mexico, April 12–14, 2015. ↩

-

Richard Cobden and the Anti-Corn Law League is discussed below. On Arthur Seldon and the Institute of Economic Affairs, see John Blundell, “Arthur Seldon and the Institute of Economic Affairs,” Liberty Matters (November, 2013) http://oll.libertyfund.org/pages/seldon-and-the-iea; many essays on Bastiat and Molinari at my personal website Reflections on Liberty and Power http://davidmhart.com/wordpress/. ↩

-

See the Liberty Matters discussion, Stephen Davies, “Richard Cobden: Ideas and Strategies in Organizing the Free-Trade Movement in Britain,” Liberty Matters (January 2015) http://oll.libertyfund.org/pages/lm-cobden. ↩

-

See the illustrated essay “Cobden and the Anti-Corn Law League” http://oll.libertyfund.org/pages/cobden-and-the-anti-corn-law-league. ↩

-

Ludwig von Mises, Human Action: A Treatise on Economics, in 4 vols., ed. Bettina Bien Greaves (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 2007). Vol. 1. http://oll.libertyfund.org/titles/1893#Mises_3843-01_123. ↩

-

Mises, “Praxeology and History” in Human Action. vol. 1, http://oll.libertyfund.org/titles/1893#Mises_3843–01_216. See also, the opening paragraph to Rothbard’s “Fundamentals of Human Action,” Chap. 1 “The Concept of Action,” pp. 1–2, and “Appendix A. Praxeology and Economics,” pp. 72–76, in Murray N. Rothbard, Man, Economy, and State: A Treatise on Economic Principles, with Power and Market: Government and the Economy. Second edition. Scholar’s Edition (Auburn, Alabama: Ludwig von Mises Institute, 2009). Thus the importance of praxeology for understanding how individuals go about pursuing their various purposes and interests, whatever they may be. ↩

-

F.A. Hayek, “The Intellectuals and Socialism” in Studies in Philosophy, Politics and Economics (The University of Chicago Press, 1967), pp. 178–94. Quote from p. 194. ↩

-

F.A. Hayek (ed.), “History and Politics,” in Capitalism and the Historians (University of Chicago Press, 1954). ↩

-

David M. Hart, “On the Spread of (Classical) Liberal Ideas,” Liberty Matters (March 2015) http://oll.libertyfund.org/pages/lm-ideas. ↩

-

Harriet Martineau, Illustrations of Political Economy (3rd ed) in 9 vols. (London: Charles Fox, 1832). http://oll.libertyfund.org/titles/1873. ↩