GUSTAVE DE MOLINARI,

L’évolution politique et la Révolution (1884)

A Translation of CHAPITRE X.

"Les gouvernements de l'avenir"

(The Governments of the Future)

|

|

[Created: 1 March, 2025]

[Updated: 29 March, 2025] |

Source

, L’évolution politique et la Révolution (Paris: C. Reinwald, 1884). CHAPITRE X. "Les gouvernements de l'avenir," pp. 351-423.http://davidmhart.com/liberty/FrenchClassicalLiberals/Molinari/Books/1884-EvolutionPolitique/Chapter10/MyTranslation/2025version/index.html

Gustave de Molinari, L’évolution politique et la Révolution (Paris: C. Reinwald, 1884). CHAPITRE X. "Les gouvernements de l'avenir," pp. 351-423.

See also the facs. PDF and the enhanced HTML of the entire book. Or the facs. PDF of just chapter 10.

Other things of interest:

- my updated list of "The Works of Gustave de Molinari (1819-1912)" in the form of a sortable table

- my table of contents ofvolumes 1-19 of the Oeuvres complètes de Gustave de Molinari, edited by Benoît Malbranque and published by the Coppet Institute

- some papers of mine on Molinari

- in particular the paper “Was Molinari a True Anarcho-Capitalist?: An Intellectual History of the Private and Competitive Production of Security” (Sept. 2019) [Online] .

Table of Contents

- I. The Reasons for the Superiority of Governments run as Business Enterprises [1] over Communal Governments.

- II. Governments Adapted to the Present and Future State of Civilized Societies.

- § 1. The Problem to be Solved. The Necessary Return to Natural Laws Governing the Constitution and Management of Enterprises.

- § 2. The Form of Government Adapted to the Era of Large-Scale Industry.

- III. The Economic System of Political States in the Era of Large-Scale Industry.

- § 1. The Kinds of Servitude and the Reason they exist.

- § 2. Political Servitude.

- § 3. The Reason for Political Servitude.

- § 4. A System of Government suited to Political Servitude. The Constitutional or Contractual Regime.

- § 5. The Liberty of Government.

- IV. The Commune and Its Future.

- V. Individual Sovereignty and Political Sovereignty.

- VI. Nationality and Patriotism.

CHAPTER X. The Governments of the Future

I. Reasons for the Superiority of Governments run as Business Enterprises over Communal Governments↩

If we wish to understand how civilized nations will extricate themselves from the regressive path onto which the Revolution has led them, we must briefly return to the time when the régime of private enterprise, whether individual or corporate, replaced political communism. [2]We must revisit the causes that led to this progressive transformation of the industry of government. [3]

In primitive times, before the advent of small-scale industry, when human populations were still sparse and organized in bands or tribes, the functions of government and the defense of these early societies were carried out by different [352] members of the community, alongside the rudimentary industries that provided their means of subsistence. These industries—hunting, fishing, and gathering the natural fruits of the land—offered only the bare necessities, making it impossible to remunerate these functions of government. Instead, these functions were imposed as shared burdens for the common good, from which no one could escape without increasing the load on others—just as in an association where some members refuse to pay their dues while still expecting to share in the collective benefits.

But over time, a vast transformation took place: small-scale industry emerged. This led to an immense increase in productivity, particularly in food production and other essential industries, making governmental functions profitable rather than burdensome. As a result, these functions became specialized and, like other industries, were increasingly managed as enterprises. Individuals with the necessary skills to carry out this kind of enterprise formed "corporations" [4]with the goal of exploiting the industry of government and deriving the highest possible profit from it. These organizations secured control over a market, striving to exclude competing enterprises and expand their reach to maximize revenue. In this regard, their practices were no different from those of industrial or commercial corporations, which arose during the same period due to advancements in production methods.

However, one might ask whether nations that lived by means of small-scale industry would not have been better off maintaining a communal political regime, as existed in early bands and tribes, and continuing to share [353] governing functions among all their members. In this way, every individual would have shared in the profits of the industry of government , instead of these profits being monopolized by a political corporation [5]that imposed its services on a subjugated nation. Humanity would not have suffered the oppression imposed for centuries by monarchies and political or religious oligarchies. It would have continued to enjoy the benefits of democracy—the government of the people by the people. Why did this not happen?

If history unfolded differently—if the old communal political system never managed to survive alongside the new regime, in which government was concentrated in the hands of a particular corporation—it is because the latter proved to be more efficient and economical. It was therefore better suited to ensuring victory, in the struggle for survival, to the nations which found themselves under subjection to others.

What are the causes of this demonstrated superiority of governments run as business enterprises over communal governments? These causes lie, on one hand, in the economic principle of the division of labor and specialization of functions, and on the other, in the natural laws governing the formation and operation of enterprises.

First of all, the functions of government are no different from any other type of work. Just like industrial, artistic, and commercial activities, they require specialized skills and knowledge, as well as continuous and exclusive dedication. When these functions are divided and specialized, they become more productive, providing services and products that are more abundant, less expensive, and of better quality. Had nations relying on small-scale industry [354] continued to govern themselves as primitive tribes or bands did—where each member took part in governance and defense while also tending to their own subsistence—these nations would have been governed and defended far less effectively, and at a much higher cost. The same would have occurred if individuals had continued to fulfill all their own needs independently: growing their own wheat, baking their own bread, making their own clothes, and constructing and furnishing their own homes. Instead, by specializing in a single trade and exchanging their goods or services for those of others, they achieved greater efficiency and prosperity.

Secondly, government is, in essence, an enterprise like any other, and as such, it is subject to the natural laws that govern all forms of business. Whether its functions are extensive or limited, whether its market is large or small, a government requires infrastructure and personnel. It demands the concentration of a significant amount of capital, labor, and technical expertise, all combined and utilized with the objective of producing the maximum useful effect at the lowest possible cost. Now, just as experience has uncovered the principles of architecture and construction, it has also revealed the economic laws governing business organization. Ignoring these principles inevitably leads, sooner or later—depending on the severity of the mismanagement—to the failure of enterprises and the collapse of institutions. Observations and experience further demonstrate that these laws apply universally, whether to agriculture, industry, commerce, or government.

[355]

Let us examine how this process unfolds. Suppose there is sufficient demand for a product or service to make its production profitable. What happens next? If the demand is modest and the market limited, an individual possessing the necessary skills, knowledge, and resources will take on the production at their own expense and risk, founding a private enterprise. If the market is larger and the product or service requires, by its nature, the mobilization of significant resources and labor, an individual enterprise is typically insufficient, necessitating a collective enterprise. Regardless of whether an enterprise is individual or collective, it must adhere to a set of unchanging rules. We will summarize these rules briefly:

- An enterprise must own or have full control over its resources, workforce, and the results of its production. It must be able to expand or contract its operations, store its products, or bring them to market under conditions that suit its interests.

- The resources and workforce at its disposal must be proportionate to the demands of production, while ensuring that the enterprise does not expand beyond certain limits. These limits are determined by the efficiency of its equipment, the competence and expertise of its personnel, and the sophistication of its methods and procedures.

- Its leadership must be unified, financially invested in its success, free to act, and fully accountable for its decisions.

- All stakeholders in the enterprise must have oversight rights proportional to their interests, along with the practical ability and competence to exercise meaningful control over its management.

- The enterprise should, as much as possible, focus on a single objective, specializing in one industry. [356] In other words, it should adhere to the principle of the division of labor and the specialization of productive functions.

- Most importantly, it must be subject to competition to a necessary degree. Otherwise, no matter how solid or well-organized it was at its inception, it will inevitably become inefficient and outdated.

[356]

These are the fundamental and essential conditions for the survival and success of enterprises in all sectors of human activity. Those that deviate too far from them quickly fail, and in general, enterprises only endure and thrive to the extent that they adhere to these principles. If we examine the structure and organization of governments that have been established as either individual or collective enterprises—ever since the functions of government became a productive activity—we will find that they have conformed to these natural conditions for success far more effectively than could have been achieved in communal arrangements. In modern societies comprising millions of individuals, the vast majority lack both the practical ability and the capacity to participate meaningfully in government administration. This is without even considering the other disadvantages of communal enterprise. What can we conclude from this? That nations have found it beneficial for government to become the responsibility of a specialized enterprise, rather than remaining a function of the entire community. This shift has enabled them to be governed and defended more effectively and at a lower cost.

It would be impossible to fully measure the advantage nations have gained, in terms of the efficiency of their services, from replacing primitive communal governments with governments structured as private enterprises. However, one could argue [357] that this advantage was limitless, in the sense that nations which had retained the communal political system would have been destroyed by those that adopted governments run as business enterprise. No matter how burdensome or costly this form of government might have been, it was always preferable to a communal government, as it provided a level of internal and external security that the latter was incapable of ensuring to the same extent. This point becomes decisive when we consider that the very nature of government services is such that their inadequacy or inferiority can lead to the downfall and ruin of the nation that consumes them. [6]

Although quality of services takes precedence over cost in this matter, the latter consideration remains significant. Consumers of political services, like all other consumers, have an interest in obtaining them at the lowest possible price. However, it may happen that an enterprise providing an essential good—such as security or bread—raises its price far beyond production costs, and even beyond what consumers previously paid when they produced it themselves. In such a case, what should consumers do? Before deciding to resume production themselves—which at first glance seems like the natural solution—they must first consider: Whether they can produce the good with the same quality and consistency as an entrepreneur who has specialized in this field; Whether they can do so at a lower cost. If the answer is no—and this is the case for government services, as it is for many others—then rather than attempting to take over production, they should focus exclusively on analyzing the causes that allow the producer to exploit the consumer and examining the appropriate remedies for this issue.

[358]

What factors determine the price of products and services? The most basic observation reveals that pricing depends on two key elements: production costs and the law of supply and demand. The latter, in turn, is influenced by the producer’s position in relation to the consumer. Three scenarios can arise: 1. the producer holds an unlimited monopoly, 2. the producer holds a limited monopoly, 3. the producer operates under free competition. In the first case, consumers are entirely at the mercy of the producer. If the product is essential to life, the producer can set prices wildly out of proportion with production costs, charging up to the maximum that consumers can afford. In the second case, if the monopoly is limited—whether by custom (reinforced by sufficient power), by a charter, or by another protective mechanism [7]—consumers may be partially shielded from monopolistic abuses. However, this protection is effective only if the limiting mechanism remains genuinely functional, a condition that has rarely been met. In the third case, when an enterprise is subject to competition, there is no need for external regulatory mechanisms to moderate prices and maintain quality. As long as competition is completely free, it naturally ensures that the selling price covers only production costs, plus a necessary profit margin.

Governments during the era of small-scale industry fell into the first two categories. Some wielded absolute monopolies over their political consumers, while others operated under limited monopolies. The former had the power to arbitrarily raise the price of their services [359] and lower their quality. However, two factors restrained them from fully exploiting this power. First, they had a permanent or at least indefinite claim over their market, which discouraged them from impoverishing their clientele. Second, the constant pressure of political and military competition forced them to avoid exhausting the source from which they drew the funds which sustained their rule. Governments with limited monopolies were more accountable to consumers. However, as political states grew and centralized their power, their rulers sought to eliminate any restrictions and oversight they deemed inconvenient or humiliating, gradually reclaiming full control over their monopolies. At the same time, the intensity of political and military competition diminished, which led to a loosening of government control, decline in the quality of services, and rising costs. As a result, political consumers became increasingly dissatisfied, and the need for a change in the regime became more apparent.

II. Governments Adapted to the Present and Future State of Civilized Societies↩

§1. Defining the Problem to be Solved. The Necessary Return to the Natural Laws Governing the Organization and Management of Enterprises

There exist natural laws that govern enterprises—laws that apply equally to all forms of enterprise, whether political, agricultural, industrial, or commercial. These laws continue to dictate the constitution and operations of enterprises today just as they did thousands of years ago and as they will in the most distant future. The failure to recognize these immutable natural laws of architecture and of governments run as a business enterprise[360] inevitably results in a decline in the quality of their products or services, an increase in their costs, and ultimately, their collapse. This is the lesson taught by economic history, both past and present.

If we examine the governments of the old regime, we will indeed find that the most stable ones—those that endured the longest and provided the best services to their populations—were invariably those whose constitution and management adhered most closely to the laws we have identified. We will also be struck by the similarities between their structure and administration and those of industrial or commercial enterprises. The founding of a political establishment was motivated by the interests of a family or a "society"limited in number. This establishment remained the perpetual and hereditary property of a "society" or a "house," which managed it from generation to generation, at its own expense and risk, subsisting on the profits of its operation after covering the costs of maintenance, equipment renewal, and personnel salaries. The king ruled his state as sovereignly as an industrialist governed his factory or a merchant his trading house, bearing full responsibility for his operations and financial obligations. The political establishment had only limited functions, producing only essential but relatively few services: internal and external security (even the administration of justice eventually became the domain of an almost independent company) and currency. All other forms of production were left to a multitude of agricultural, industrial, and commercial enterprises, structured and managed in the same way as the political establishment that protected them.

Now, if we examine the structure and management methods [361] of governments that emerged from the Revolution, we will recognize that they fundamentally deviate from the laws governing the construction and operation of industrial or commercial enterprises. The state has ceased to be the possession of a family or a limited association; it now belongs to a nation—a community whose members number in the millions, each with only an infinitesimal stake in the enterprise, and most of whom lack both the opportunity and the ability to actively and effectively participate in its management. As a result of this fragmentation of interests, the physical impediments, and the incapacity of the vast majority of its owners, the exploitation of the state has fallen into the hands of political associations. These associations sometimes seize control through force, sometimes obtain it for a limited period through an assembly of property owners, or more precisely, through an electorate composed of those deemed politically capable. Beyond the inevitable fraud that occurs in granting control over an enterprise whose operations amount to billions, what is the outcome? It is the transfer of the control of the state to an association that, having only temporary control, is only interested in extracting the maximum possible profit and advantage within its short tenure, even at the cost of sacrificing the future for the present. Hence, there is an irresistible tendency to expand the functions of the state and, consequently, the benefits that can be derived from its control. This tendency is further reinforced by the competition among associations vying to seize or retain control of the state. Finally, these temporary managers, regardless of the mistakes, misjudgments, or even crimes they commit in their administration, bear no real consequences for their actions. The only risk they face is that, at the end of their tenure, [362] the state might be awarded to another group. Meanwhile, it is the nation—the actual owner—that bears the burden of depreciation of the public domain and the responsibility for the debts incurred by its managers. Should we be surprised, then, that given these deviations from the fundamental laws of enterprise structure and management, governments today have only fleeting existences while imposing ever-increasing burdens on their nations, far beyond what their resources can sustain? It has been rightly observed that if industrial and commercial enterprises were structured and managed like modern political states, they would quickly face bankruptcy. States only persist because of the vast resources of nations of property owners [8]and the progressive expansion of their industries. However, if the current political system were to continue indefinitely, even the wealthiest and most industrious nations would ultimately be ruined. Given this reality, what is the problem that must be solved—a problem that will become ever more pressing for civilized nations as they continue to suffer under the present conditions? It is this: modern governments must be brought back in line with the essential principles that govern the organization and management of enterprises. The model should be industrial and commercial enterprises, which have remained structured and managed in accordance with these principles. Thus, the necessary reforms would entail:

- The State must once again become the property of a "house" or an association limited in number, whose members all have a significant vested interest in ensuring that it is well-constituted and well-managed.

- This house or association must own the State in perpetuity, managing it freely and sovereignly under its own full responsibility, without being able to shift the consequences of its mismanagement onto political consumers. In other words, the nation should not be forced to cover the deficits [363] or pay the debts of the entrepreneur managing the State, just as a bread or meat consumer is not obligated to cover the financial losses of a baker or butcher. This was, in principle if not always in practice, the situation under the old regime.

- finally, The house or proprietary association [9]managing the State must rigorously limit its industry to the production of security, [10]following the example of governments of the old regime, and must relinquish all other services—including even the issuing of currency—to independent enterprises.

Only then will governments once again be able to count their existence in centuries rather than in fleeting terms. Only then will they cease to be, in the vivid words of Jean-Baptiste Say, "the ulcers of nations." [11]

§2. A Form of Government Adapted to the Regime of Large-Scale Industry

Does this mean that political progress consists of a simple return to the governments of the old regime? No, no more than architectural progress would consist of returning to the construction methods of ancient Egypt, merely because the fundamental laws of architecture have remained unchanged since the time of the Pharaohs. The form of buildings has changed and will continue to change, even if the principles governing their construction remain immutable. The same applies to the form of political and other enterprises.

Under the old regime, governments were either monarchical or oligarchical, except in a few small Swiss cantons where they remained communal or democratic. In other words, the State was the property of a ruling house or an association, and this property was passed down from father to son, following the natural laws of heredity, albeit with some modifications through specific legal provisions or agreements. The same system applied to [364] other types of enterprises. This system has continued to prevail in industry and commerce, where enterprises belong either to family-run houses or to associations. However, the latter, which once resembled political oligarchies in structure, have been transformed by the invention of transferable shares. We have previously discussed the advantages of this new form of enterprise, despite its imperfections and remaining flaws. [12]It is, as we have argued, the form best suited to the regime of large-scale industry, just as the family-owned enterprise was best suited to small-scale industry. We can therefore anticipate that "political houses" [13]will gradually disappear, just as family-run businesses are vanishing in industries that require large accumulations of capital and labor, such as railways, mining, and similar sectors. These "houses" (family owned and run enterprises) are giving way to "societies" (business firms or corporations). There are already precedents for applying this more advanced form of business enterprisesto political establishments. The most famous example is the British East India Company, which demonstrated the potential of this system. Had it not been for the rise of communist doctrines in England, which led to its dissolution, it would still be regarded as a model of sound political governance and economic administration. [14]

[365]

III. The Economic Regime of Political States in the Era of Large-Scale Industry↩

§1. The Kinds of Servitude and the Reason they exist

We have just examined what the probable form of political states will be in the era of large-scale industry; we must now explore what their economic regime will be. Will it be an unlimited or limited monopoly over consumers, as in the era of small-scale industry, or will it be based on competition? In all other branches of industry, the latter regime has generally begun to prevail. Enterprises can now be freely established [370] in unlimited numbers, while consumers, for their part, are free to turn to those that offer the best products or services at the lowest cost. Under this system, producers are free to create their enterprises, manufacture their products or services, and set their prices as they see fit; but consumers, in turn, are free to accept or reject these products and services. Thus, freedom is the principle governing the relationship between producers and consumers, and it is destined to play an increasingly dominant role in the various branches of human activity.

But is this regime currently applicable to political enterprises? Will it ever be?

To answer this question, we must first look back at the economic regime that prevailed until recent times in the production of most goods and services. This regime was based on seizing control of a market [15] , or the monopoly of supply, sometimes absolute, sometimes limited by custom or some regulatory apparatus, which imposed a restrictive form of servitude on the natural freedom of the consumer. Business houses or industrial and commercial corporations, as well as political and religious organizations, controlled their respective markets. Within the boundaries of these markets, they did not tolerate the establishment of competing enterprises or the importation of foreign products and services. They defended this ownership of the market [371] with all their power. In the political and religious spheres, any attempt to encroach upon or divide their market was rigorously prosecuted and punished. The Inquisition, for example, was instituted to defend the market appropriated by the Catholic faith, ensuring the protection of its revenues against both internal and external competition. Similarly, industrial and commercial corporations sought the support of the ruling House or the political corporation to prevent the importation of foreign goods and to bar rival corporations from infringing upon their domain within the state. Under the regime of the state of war, this regime—at least regarding goods essential for life—provided security not only for producers but also for consumers. In a country perpetually exposed to war—and let us not forget that in those times, peace was the exception and war the rule—if agricultural and industrial enterprises had not possessed their own guaranteed markets, they would have been unable to align production with consumer demand. During peacetime, imported goods would have disrupted producers' expectations, causing devastating losses, while in times of war—when external trade was interrupted—the resulting decrease in domestic production would have left consumers deprived of essential goods. Agricultural and industrial servitude thus functioned as a form of insurance, benefiting both producers and consumers. However, as wars became less frequent and international communications improved, the necessity of this insurance declined, and governments [372] became less committed to maintaining it. They ceased to uphold the strict prohibition of foreign products, first by allowing trade fairs or temporary free markets upon payment of fees, then by permitting imports of most goods at all times, subject to tariffs or "import duties." They allowed markets controlled by the guild corporations to be encroached upon—either by authorizing new masters in exchange for financial compensation or by permitting free enterprises to operate under a simple licensing tax. Eventually, they instituted as a general principle freedom of industry and commerce within national borders, replacing monopolies with competition.

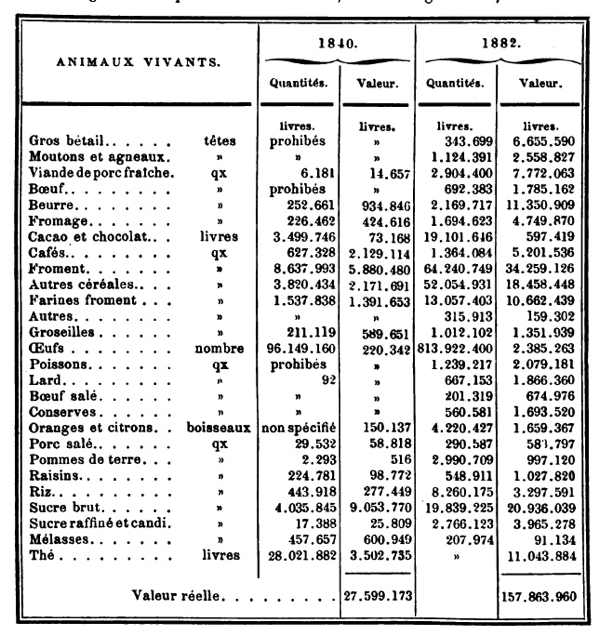

The need for economic security in times of war was, as is well known, the strongest argument put forth by British protectionists against the repeal of the Corn Laws. They warned that abolishing these protective laws would leave England dependent on foreign nations for its food supply, highlighting the dangers of such a situation with either genuine or feigned concern. Events proved them correct in one respect—England now imports more than half of its food supply. However, thanks to the extraordinary development of transportation and communications, the risks associated with wartime disruptions have been greatly reduced. As a result, the British nation has chosen to accept this risk rather than continue paying the higher food prices imposed by the Corn Laws. [16]

As for religion, as long as it remained an instrument of government, its market was protected [373] just as rigorously as that of the state. But as the ties between church and state loosened, religious servitude was less strictly enforced and is now in the process of disappearing.

Today, in civilized states, the regime of free industry and internal competition has generally prevailed for agricultural, industrial, and artistic products, as well as for religious services. Increasingly, the progress of free trade [374] is also introducing external competition. The old system of appropriated markets survives only in a few industries—some considered to possess natural monopolies and therefore subject to regulatory constraints, others incorporated into the direct administration of the state for various reasons.

§2. Political Servitude

While states have abolished appropriated markets in commerce, industry, and religion, they have, on the other hand, worked diligently to preserve this old regime for their own services. Indeed, states born from revolutionary movements have shown themselves even more determined than others to maintain and perpetuate political servitude—apparently in the name of freedom. In France, the revolutionary government began by proclaiming the indivisibility of the Republic, and the government of the American Union sacrificed, to this necessity—real or supposed—one million human lives and fifteen to twenty billion francs, consumed in the Civil War. Any attempt at secession [17]is considered an act of high treason, condemned with horror and punished severely, whether by democratic republics, absolute monarchies, or constitutional regimes alike. [18]The restrictions go even further: to prevent any attempts at fragmenting the political market, [19]populations suspected of secessionist tendencies are forced to abandon their institutions and language, replacing them with those deemed "national."

The question arises: are these repressive and preventive measures, not to mention their moral condemnation, justified? If progress has consisted of eliminating servitude in industrial, commercial, and religious matters that ensured corporations of the old regime ownership of their markets, to the exclusion of all competition whether domestic or foreign, should this servitude be maintained for the political market? Is it, and will it always be, necessary for political consumers to remain subjected to the house, corporation, or nation that owns and operates the state, forced to consume its services, whether good or bad? Will they never have the freedom to establish political enterprises in competition with the existing ones, to grant their allegiance to competing enterprises, or even to grant it to none at all—should they find it more advantageous to manage their own lives and property? In short, is it inherent to the nature of things that political servitude should persist, preventing people from ever possessing liberty of government? [20]

It is evident that this form of servitude—the most burdensome of all, since it pertains to services of [376] primary necessity—can only be maintained under a regime where freedom is the general rule if it is justified by the public interest. If the public interest requires that the proprietors operating political establishments retain full ownership of their market—at least so long as they are not forced to relinquish part of it due to an unfavorable war or do not find it advantageous to part with it through sale or exchange—then "the liberty of government" cannot be established in the same manner as freedom of religion, industry, or commerce. Under this hypothesis, [21]the right of secession would have to remain permanently prohibited, or rather, there would be no right of secession. However, it is worth noting that significant breaches have already been made in this aspect of old public law under the influence of changes brought about by advances in security, industry, and communication between civilized nations. While governments do not allow competition within their own political markets, they have generally given up preventing their subjects from engaging in acts of individual secession through emigration and naturalization abroad. On the other hand, they refuse to recognize any collective secession that would alter their territorial domain. Nevertheless, if secessionists are strong enough to enforce their separation—as were the British and Spanish colonists in North and South America—the former proprietors of these (political) markets which have broken away [22]eventually resign themselves to accepting the fait accompli and, over time, even come to recognize the legitimacy of the secessionist governments. However, in such cases, they yield only to force, and history provides almost no examples of secession being achieved peacefully.

Let us therefore examine what arguments may be advanced [377] in favor of maintaining political servitude—in the economic sense of the term—while other forms of servitude have ceased to be considered necessary.

§3. The Reasons for Political Servitude

Under the old regime, political servitude—like all other forms of servitude—was justified by the necessities of a state of war. If a portion of the nation had possessed the right to separate from the state—whether to annex itself to a competing state, to found an independent one, or even to live without government—the exercise of this right would have posed a general danger. This danger would have been all the greater given that the nation risked being invaded, destroyed, or subjugated by less advanced peoples, such as the barbarians who constantly threatened the borders of ancient and medieval states. The secession of a portion of the population, by weakening or simply dividing the forces of the state, would have increased the risk of destruction, enslavement, and, in any case, a setback to civilization—a threat from which the state served as a protective barrier. The situation of civilized nations in that period of history can be compared to that of populations in regions perpetually threatened by the ocean—such as the Netherlands. It is essential that all inhabitants, without exception, contribute to the maintenance of the dikes. Those who refused to do so would unfairly benefit from a defensive system without bearing its costs. They would thereby increase the burden on others, and if the remaining resources proved insufficient to build dikes strong and high enough, even those who contributed honestly would become victims of the selfishness of those who abstained. Likewise, those who insisted on constructing private dikes without integrating them into the common system would endanger the collective defense against the destructive element. In times [378] when civilization was threatened by barbarism, political servitude was therefore an absolute necessity. However, its justification has largely diminished since the balance of power shifted in favor of civilized peoples. Nevertheless, political servitude may still be warranted—albeit to a lesser degree—due to the inequalities in civilization that persist from one country to another.

In the present state of the world, while the superiority of physical and moral forces, resources, and technical knowledge—the very foundations of military power—clearly belong to the most civilized nations, it cannot be said that they are entirely immune to invasions by less advanced peoples. Certainly, the populations of the Russian Empire, for example, have no interest in invading Central and Western Europe in the manner of the pillaging barbarian hordes that once destroyed the Roman Empire. But given the backward state of Europe's political constitution, it is not the general interest of the populations that determines peace and war. Sometimes, decisions are driven by the real or perceived interests of a sovereign house and the army of civil and military functionaries that supports it. Other times, it is the interest of a political party whose leadership is drawn from a class which lives off the budget [23] and its related revenue, and for whom war provides an increase in their markets, and thus their profits,or at the very least, serves to consolidate its hold on power in certain circumstances. As long as this situation persists, even the most civilized nations will remain exposed to the risks of invasion and conquest, and "political servitude" will retain a degree of justification. However, should this state of affairs come to an end—should the general interest of "political consumers" grow powerful enough to curb the exploitative and predatory appetites of the [379] "producers"; should the risk of invasion and conquest diminish as inequalities in civilization fade under the influence of expanding trade and the spread of knowledge—then "political servitude" will lose all justification, and "the liberty of government" will become possible.

§4. A System of Government Suited to Political Servitude. The Constitutional or Contractual Regime

In the meantime, "political consumers" must resign themselves to enduring the natural defects of the old regime of appropriated markets, resorting only to the unfortunately always imperfect and insufficient means of limiting the power of the monopoly to which they are subject. The system currently suited to this state of affairs is that of constitutional or, more accurately, contractual government—whether monarchic or republican—based on a freely negotiated and agreed upon contract between the "house" or "company" producing political services and the nation that consumes them.

However, this system must be established in a manner that respects the natural laws governing all enterprises, whether political, industrial, or commercial—whether they hold a monopoly or are subject to competition. The political house or company must possess capital proportional to the scale and requirements of its enterprise—fixed and transferrable capital, in the form of fortresses, war materials and supplies, administrative and police offices, prisons, and currency for paying its civilian and military employees, and so on. It must have the freedom to organize its operations and recruit its personnel without restrictions or conditions being imposed upon it. In return, it must bear the financial responsibility for its actions and undertakings, [380] absorbing any losses without shifting them onto consumers—except in cases of force majeure, such as a barbarian invasion, specifically outlined in the contract. It must also collect the profits from its activities, though these may be shared with consumers above a certain rate, likewise specified in the contract. Finally, its powers and functions must be strictly limited to what is necessary for the effective provision of its services—namely, protecting the lives and property of political consumers from internal and external threats—without encroaching upon the domain of other industries. These, in essence, must be the conditions of the contract if we want the Houses or companies which produce political services to once again function in a useful and sustainable manner. It is because these principles have been disregarded—under the influence of revolutionary doctrines and events, and because the constitution and operation of political enterprises have ceased to follow the natural laws governing all enterprises—that past attempts to establish economic and stable governments have failed. Likewise, it is why the governments inherited from the old regime have not successfully adapted to the modern state of society.

However, can nations themselves negotiate these conditions of the political contract and oversee their execution? Must they not appoint representatives—first to draft the contract after debating its clauses with the delegates of the political house or association, then to amend and improve it as necessary, and finally to oversee and monitor the provision of political services, ensuring their quality and fair pricing, while also regulating the nation's participation in the enterprise's losses and profits? Until now, this necessity has been considered [381] indisputable. Yet, given the almost inevitable corruption of the representative system, one might question whether the guarantees it supposedly provides are not, in most cases, illusory. Would it not be preferable to allow consumers themselves to negotiate the contract's terms, amend it as needed, and oversee its execution—without imposing any formal system of representation upon them? Undoubtedly, individual political consumers would be incapable of managing this task alone. But could freely formed associations among them not fulfill this role, aided by the press? In countries where the majority of the population lacks either the ability or the leisure to engage in political affairs, would not such free consumer representation—composed of those who do possess the requisite capacity and time—serve as a more effective and less corruptible instrument for controlling and improving the management of the state than the official representation of an ignorant multitude or a privileged class?

§5. The Liberty of Government

A day will come, however—and perhaps this day is not as distant as one might assume when considering the backward course that the Revolution has imposed upon civilized societies—a day will come, we say, when political servitude will lose all justification, and the liberty of government, in other words, political freedom, will be added to the bundle of other liberties. Then, governments will be nothing more than free insurance companies for life and property, constituted and organized like all other insurance companies. [24]Just as communal organization was the form of government suited to the bands and tribes of primitive times, and as the patrimonial or corporate enterprise—with absolute monopoly or one limited by [382] customs, charters, constitutions, or contracts—was suited to the nations of the era of small industry, so too will the joint-stock company, operating in a free market, likely be the form of government best suited to societies in the era of large-scale industry and competition. [25]

IV. The Commune and Its Future↩

In primitive times, embryonic societies, living off hunting, fishing, and gathering the natural fruits of the land, formed political communities in which all members were required to contribute to the government and to defense. In the next period, when the regular cultivation of food plants and the rise of small-scale industry enabled human populations to multiply in proportion to the enormous increase in their means of subsistence, political functions, having become productive, were divided and specialized in the hands of a corporation or a house that founded and operated the state. Whether it was divided among the members of the corporation—forming an ensemble of feudal lords bound together by feudal ties—or concentrated in the hands of a single hereditary master and owner, this political domain had to be subdivided to meet the necessities of its management. This subdivision occurred in two ways: sometimes it was carried out by the owners operating the state, and at other times, by the populations subjected to them.

In all countries where the conquered population was reduced to slavery, the commune, for example, only came into being—or rather, reconstituted itself—when slaves moved into a state of serfdom. In places where conquerors [383] merely imposed serfdom upon the inhabitants, the commune was formed from the primitive tribe or band, which settled on the land first out of necessity for agriculture and crafts and later due to the interest of the political domain's owner, who lived off the exploitation of the human livestock in his domain. [26]He compelled them to cultivate part of the land for his benefit while allowing them to enjoy the rest. But whether the population more advanced form of servitude, the political owner—be it king or lord—only took the trouble and bore the costs of governing them insofar as it served his interest and only to the extent that it did. He allowed groups or communities to form at their convenience, according to the lay of the land, ease of local communications, language, and racial or cultural affinities, provided that each commune did not encroach upon the borders of the others or step outside the boundaries of his domain. [27]He also allowed them to maintain their customs, speak their language or dialect, use their own weights and measures, and meet their various individual or collective needs as they saw fit—except for services that could yield him a payment or a profit. For instance, he required them to purchase salt from him, use his currency, his ovens, and his presses. Finally, he subjected them to his justice, [384] at least in cases of crimes or offenses that disturbed the peace of the domain—especially when they infringed on his rights or revolted against his authority. Communes formed larger groupings—cantons and bailiwicks—for the establishment and maintenance of communication routes, the collection of dues, and later, when seigneuries were absorbed into the royal domain, they became provinces administered by an intendant. Some communes, favorably located for industry and trade, experienced considerable growth, becoming cities where trades and crafts were organized into guilds. The heads or leaders of these guilds administered the city under the authority of the lord. When the lord imposed excessive dues, ruled tyrannically, or when the magistrates and local leaders were hungry for power, communes sometimes sought to free themselves from seigneurial authority and govern themselves. Occasionally, the lord agreed to sell them their freedom from taxation [28]by capitalizing the total amount of dues; other times, they attempted to seize their freedom by force. In France, the king encouraged the communes' rebellion to weaken the power of the lords. However, rarely did the liberated communes succeed in governing themselves effectively. Sometimes, the population was exploited by an oligarchy of guilds; other times, the commune became the battleground for factional struggles—one side representing the bourgeoisie, the other the common people—both vying for control over the small communal state. This struggle was analogous to what we witness today in countries where the state has become the property of the nation. However, when large seigneuries absorbed smaller ones, and later, when the monarchy absorbed the larger fiefs, what little independence communes and [385] provinces had gained or retained disappeared. The disparity between the resources available to the ruler of a great state and those of a commune or even a province became so vast that any conflict between them became impossible. The result was that communes and provinces retained only the portion of the government that the ruler of the state found no profit in taking from them or that would have been a burden without sufficient compensation. Such was the situation when the Revolution broke out.

While transferring to their intendants and other civil and military officials the powers and duties previously exercised by lords and their officers—and even expanding these powers at the expense of the officials of communal and provincial "self government" [29]—the kings had nonetheless respected, to some extent, local customs. They had not thought to interfere with the groupings that had naturally formed over centuries in response to the needs and affinities of the populations. But this state of affairs found no favor in the eyes of ignorant and fanatical reformers who aimed to completely reshape and regenerate French society. They arbitrarily redrew the provincial boundaries and replaced the kingdom’s thirty-two provinces with eighty-three departments, nearly tripling the number of high-paid administrative officials. At the same time, they pushed centralization to its maximum development—a process that had naturally resulted under the old regime from the successive absorption of small feudal sovereignties into the royal domain. Another factor contributing to this centralization was purely economic. As industrial productivity increased under [386] the influence of mechanical and other inventions, the ability to pay for the functions of government of all kinds also grew. Consequently, as soon as the functions of local self government became profitable, it was advantageous to transfer them to the central administration. These functions provided new positions, expanding the administrative market and increasing the power and influence of the senior officials who distributed the positions. Thus, the central administration expanded at the expense of local self government, which retained only subordinate roles—either weakly compensated or entirely unpaid.

This centralization of services had advantages and disadvantages: advantages, in that the specialized and adequately paid officials or employees of a country's general administration can possess, to a higher degree, the necessary knowledge for carrying out their functions and can perform them better than officials or employees with multiple tasks, insufficient salaries, or no salaries in a local administration. Added to this is the fact that they are less susceptible to local influences and biases. The disadvantages, however, lie in the fact that even the smallest matters must pass through a long administrative chain and cannot be resolved without numerous delays, regardless of how urgent a solution may be. These advantages and disadvantages have, as we know, been an inexhaustible source of debate between supporters of centralization and those of decentralization: the former wishing to increase the powers of the central government at the expense of departmental and municipal sub-governments, while the latter seek, on the contrary, to reserve for departments and municipalities the examination and final resolution of all local affairs. However, neither side has thought [387] to investigate whether there might be a way to reduce and simplify these responsibilities by relinquishing to private industry a portion of the services monopolized by the State, the department, or the municipality. Whatever the outcome of these debates, it could not, therefore, lead to a reduction in the burdens placed on consumers of public services.

The decline of the old regime and the regression towards political communism that has characterized the new regime, by fostering the emergence of political parties and their competition to exploit the State, have inevitably led to an increase in the number and weight of functions of all kinds, which constitute the booty [30] necessary for these political armies. Undoubtedly, the portion of this booty that could be provided by local administrations was of lesser value than that contributed by the central administration. Many functions, such as those of municipal and departmental councilors, mayors, and deputies, remained unpaid or provided only small allowances. Those who sought these positions did not fail to loudly proclaim their selflessness and patriotic devotion, but in reality, these positions conferred influence that could be monetized in various ways; moreover, they served as a stepping stone to higher offices. For this reason, under the influence of the same factors that contributed to expanding the powers and increasing the budget of the State, we have seen the local government powers and budgets grow, particularly in cities. The tendency of urban administrations has been to transform the municipality into a small State, as independent as possible from the larger one, managing not only urban planning and public works but also policing, public education, theaters, fine arts—taxing the population at will and surrounding itself, like the central State, with a [388] protective fiscal wall, even protecting municipal industries. Consequently, municipal, departmental, and provincial expenditures have increased at a rate surpassing, in certain municipalities, even the growth of State expenditures, making life increasingly expensive. At first glance, one might think that the central government would oppose this escalation of local expenditures in order to protect its own revenue. It has, in fact, prohibited municipalities from encroaching on its prerogatives and ensured that they do not establish taxes that could compete with its own. However, it has done nothing to prevent them from expanding their responsibilities at the expense of private industry. This is understandable: are not political parties—whether in power or aspiring to be—interested in increasing the spoils of offices and influential positions, both in the municipality, the department, or the province, as well as in the State, since this booty constitutes the fund for paying their personnel?

However, a time will come when this rapidly growing burden can no longer be sustained, and an evolution similar to the one we have demonstrated as inevitable for the State will have to take place in the commune, the department, or the province. This evolution will be driven by: 1. the impossibility for local administrations to continue covering their expenditures through taxes or borrowing; 2. intercommunal and regional competition, intensified by the development of transportation and the increasing ease of industrial and population mobility. Localities where industrial production costs and living expenses are excessively inflated by local taxes will risk being abandoned in favor of those [389] where this source of increasing costs is less severe. To avoid ruin, they will then be forced to reduce their responsibilities and expenditures. Apart from urban planning and public works—encompassing sewer systems, transportation, paving, lighting, and sanitation—there is not a single municipal service that could not be handed over to private industry. Finally, if we examine these services closely, we will see that the already evident trend of progress is to annex them to real estate companies, which provide the management of buildings and land. Consequently, the costs of these services will be directly incorporated into the operating expenses of these companies.

Let us attempt, using a simple hypothesis, to illustrate the modus operandi of this progressive transformation. Suppose that a real estate company is established to build and operate a new city (and do we not already see companies of this kind constructing streets and even entire neighborhoods?) on the condition that it remains entirely free to design, maintain, and manage it as it sees fit, without any central or local administration interfering in its affairs. How would it proceed? First, it would acquire the necessary land in the location it deems most advantageous—one that is well situated, easily accessible, and healthy. Then, it would call upon architects and engineers to design plans and estimate costs for the future city, selecting from among these the most advantageous proposals. Construction companies and workers in the building and infrastructure industries would immediately begin their work. Streets would be laid out, residential buildings suitable for different categories of tenants would be constructed, and schools, churches, theaters, and meeting halls would not be forgotten. However, in order to attract tenants, [390] it is not enough to simply provide housing, schools, theaters, and even churches. Their homes must be accessible via well-paved and well-lit streets; they must have access to water, gas, and electricity within their homes; they must be served by a variety of affordable transportation options; and finally, their persons and properties must be protected from all harm within the city's limits. The better these services are provided, the lower their cost, and the faster the new city will become populated. What would the property owning company do, then? It would pave the streets, establish sidewalks, dig sewers, and build and decorate public squares. It would contract with other businesses or companies for the supply of water, gas, electricity, security, streetcars, and aerial or underground railways—services that, due to their specific nature, cannot be individualized or subject to unlimited competition within the city's confined space. For omnibuses and hired carriages, on the other hand, it would simply encourage competition, unless demand is too low to sustain it; in that case, it would set a maximum fare while also requiring transportation providers and private vehicle owners to contribute to the paving and lighting costs. It would establish regulations for public infrastructure and sanitation, prohibiting or isolating businesses that are dangerous, unhealthy, disruptive, or immoral. Additionally, since the city's layout may need modifications in the future—such as widening certain streets or removing others—the company would reserve the right to reclaim and reorganize its properties, providing compensation proportional to the remaining duration of existing leases. However, it is clear that it would only exercise this right if it were to increase the profitability of [391] its operations. As for managing its operations, the company could administer them directly or through a city office, which would be responsible both for the maintenance and oversight of the various city services and for collecting rents. These rents would include charges for services that are inseparable from housing, such as local policing, sewage systems, street paving, and lighting.

A company established in this way to operate the housing industry on a large scale would have a vested interest in minimizing its construction, maintenance, and management costs while naturally tending to maximize rental rates. If it enjoyed a monopoly, this tendency could only be restrained and counterbalanced by customs or regulations similar to those that once limited the power of all monopolistic industries. However, thanks to the abundance of transportation options and the ease of movement, no such monopoly exists in the housing industry today. There is no need for any artificial mechanism to protect consumers; competition alone is sufficient to compel housing providers—no matter how large their enterprises—to improve their services and lower their prices to the level necessary to sustain their industry.

Let us now continue with our hypothesis. Let us suppose that the favorable situation of the new city, the good management of urban services, and the moderate rental rates work to attract the population, and that it becomes advantageous to build additional housing. Let us not forget that businesses of all kinds have their necessary limits, determined by the nature and degree of advancement of their industry, and that below and beyond these limits, their production costs increase [392] and their profits decrease. If the company that has built and operates the city believes that these limits have been reached, it will leave it to others to expand it. We will therefore see other real estate companies forming, who will build and operate new neighborhoods, which will compete with the old ones, but will still increase the overall value by enhancing the city’s power of attraction. Between these operating companies—those in the city center and those in the new streets or neighborhoods—there will be necessary relationships of mutual interest for the connection of roads, sewers, gas pipes, tramway systems, etc. Consequently, they will be compelled to form a union or permanent syndicate to regulate these various issues and other matters resulting from the juxtaposition of their properties. The same union will, under the influence of these same necessities, have to extend to the rural communes in the vicinity. Finally, if disputes arise between them, they will have to resort to arbitrators or courts to resolve them.

Thus, according to all appearances, communes will transform into free enterprises for the operation of the housing industry and other matters naturally related to it. Assuming that individual property and real estate operation continue to coexist alongside shareholder ownership and operation, despite the economic superiority of the latter, the various owners and operators of the city—individuals or companies—will form a union to regulate all matters of common interest. This union, consisting of owners, individuals, companies, or their representatives, would regulate all roadwork, paving, lighting, sanitation, security, subscription-based [31][393] or otherwise, and it would liaise with neighboring unions for the common regulation of these same matters, as long as the necessity of such cooperation is felt. These unions would always be free to dissolve or merge with others, and they would naturally be interested in forming the most economical groupings to meet the necessities inherent in their industry.

While revolutionary and socialist doctrines tend to constantly increase the functions of the commune or the state, transformed into a vast commune, by bringing all industries and services into its sphere of activity, thus creating a monstrous monopoly, the evolution which is driven by industrial progress and competition works, on the contrary, to specialize all branches of production, including those exercised by the commune and the state, and to assign them to freely constituted enterprises, subject to the action of competition, which is both propulsive and regulatory. These free enterprises, however, still have relationships defined by the necessities of their industry. Hence, a natural but free organization will develop and change in response to these same necessities.

Thus, instead of absorbing the organism which is society, as the revolutionary and communist conceive it, it is the commune and the state which merge into this organism. Their functions are divided, and society consists of a multitude of enterprises, each exercising a special function, forming, under the influence of common necessities derived from their particular nature, unions or free States. The future, therefore, does not belong to the absorption of society by the state, as [394] communists and collectivists claim, nor to the abolition of the state, as anarchists and nihilists dream, but to the diffusion of the state within society. This, to recall a famous formula, is the Free State in a Free Society.

V. Individual Sovereignty and Political Sovereignty.↩

Man appropriates all the physical and moral elements and forces that constitute his being. This appropriation is the result of a process of discovering or recognizing these elements and forces, and applying them to satisfy his needs, in other words, their use. This is personal property. Man appropriates and owns himself. He also appropriates—through another process of discovery, occupation, transformation, and adaptation—the land, materials, and forces of the environment in which he lives, insofar as they are able to be appropriated. [32]This is real and personal property. [33]These elements and raw materials, which he has appropriated in his person and in the surrounding environment, and which constitute values, he continually acts upon, driven by his interests, to preserve and increase them. He shapes, transforms, modifies, or exchanges them at will, as he sees fit. This is liberty. Property and liberty are the two factors or components of sovereignty.

What is the individual’s interest? It is to be the absolute owner of his person and the things he has appropriated outside of himself, and to dispose of them as he sees fit; it is to be able to work either alone or by freely associating his energy and his other property, in whole or in part, with those of others; it is to be able to exchange the products of the use of his personal, real, or personal property, or to consume or keep them; in short, to possess, in all its fullness, "individual sovereignty."

However, the individual is not isolated. He is perpetually in contact and in relationships with other individuals. [395] His property and freedom are limited by the property and freedom of others. Each individual sovereignty has its natural borders within which it is exercised, and which it cannot cross without encroaching on other sovereignties. These natural limits must be recognized and guaranteed, otherwise, the weak will be at the mercy of the strong, and no society will be possible. This is the purpose of the industry we have called "the production of security" or, to use the usual term, the purpose of "government."

Like all other industries, this one (government) started out imperfect and crude; it gradually improved, but not without experiencing phases of regression and decline. In the early stages of civilization, it was exercised by the community of the members of the band or tribe. Possessing only rudimentary tools and weaponry, which barely suffice to meet the primary needs of life, and unable to expand beyond a few hundred or a few thousand people, the primitive band could not provide a large enough market to support a specialized government enterprise. Its members were forced to produce their own security. They were both the producers and consumers of it. They divided their time and efforts between the production of food and the production of security. Only, with this difference that, due to the nature of these two industries, one could usually be exercised individually, whereas the other could only be exercised collectively. Thus, the members of the band or tribe formed a community or mutual insurance society, [34]in which, in the absence of other capital, each contributed a portion of his time and energy. From these associated individual sovereignties, aimed at [396] providing for a common need, is born political sovereignty. This sovereignty is collectively owned, but not equally, by all members of the association. Each possesses a share proportional to his contribution.

Such is the origin and such are the elements of political sovereignty. Like individual sovereignty, it has its limits. These limits are determined by the object for which it is established: to secure the lives and property of the members of the mutual society, [35]considered as consumers of security, against any internal or external aggression. It cannot achieve this goal without imposing charges, obligations, and rules, which decrease each individual’s property and freedom. As long as these charges, obligations, and rules do not exceed what is necessary, the sovereign does not exceed the limits of his right. But where is the guarantee that he will not exceed them? How is the individual consumer of security protected from the abuse of the power of the collective producer of security? This essential guarantee resides first in his right to withdraw from the mutual society, either to produce his own security individually or to join another mutual society; however, in practice, this right is almost impossible to enforce. It also resides in the individual’s participation in the exercise of political sovereignty, and, in a mutual society which is small in number, this guarantee could have been sufficiently effective.

In the second age of civilization, the mode of the production of security undergoes a radical change. Thanks to improvements in tools, labor productivity increases to such an extent that the individual can not only fully provide for his primary needs, but also for many others. This leads to the phenomenon of the specialization of industries and the division of labor. Separate industries are carried out [397] by specialized enterprises, whose importance varies according to the scope and wealth of their market. The production of security follows this common law. We have seen how, under the influence of these same necessities, primitive mutual aid societies were succeeded by more organized enterprises, such as partnerships [36]or other forms, which founds a State and establishes a government. What happens to sovereignty under this new regime?

There are then two societies: the owning and operating society of the State, and the society—or rather the multitude—subject to its rule. The members of the first initially possess both individual sovereignty and political sovereignty, as do the members of the primitive communities or mutual societies. However, the necessity of maintaining and expanding their domination, which provides their livelihood, leads to the concentration of political sovereignty in the hands of a small number of families, and eventually even in the hands of one. Those excluded from it are then at the discretion of the sovereign, except for any guarantees they may have secured to prevent him from infringing upon their individual sovereignty. If these guarantees do not exist, they suffer under the regime of despotism and the sovereign's whim: the sovereign can dispose at will of the elements of each person’s individual sovereignty: property and freedom. However, they may have an interest in accepting this risk inherent in the concentration of political sovereignty, if this concentration helps guarantee the domination of which they are participants and beneficiaries.

The multitude subject to the domination of the society which is the master of the State does not possess, at the beginning of this regime, either [398] individual sovereignty or political sovereignty. It is a slave. The individuals composing it are appropriated either to a member or to the collective of the members of the ruling society. Only over time, through a series of progressive changes, determined mainly by political competition, do they come to be liberated, that is, come into possession of individual sovereignty. However, it is not granted to them in full; they remain politically subjugated or in servitude. The freed individual is no longer a slave or serf, but he is still a "subject." He is the owner of his person and his property; he is free to act as he pleases; in other words, he possesses, more or less completely, sovereignty, except for the strictly and universally reserved obligation of having it guaranteed by the political society of his former masters, under the prices and conditions established by it, whether it exercises political sovereignty itself or whether this exercise is concentrated in an oligarchy or in a "house." The consumer of security thus finds himself entirely at the discretion of the producer, for he is forbidden not only to ask for it from others, but also to produce it himself. And his situation will worsen in this respect as his individual sovereignty becomes more complete: when he was the dependent of a master belonging to the ruling society, this master was interested in protecting him from its influence and the abuse of the sovereign’s power, and the more dependent he was, the more this interest existed. This interest disappears once the slave or serf becomes fully an owner and master of himself. He then finds himself entirely at the mercy of the corporation or political house, holding the monopoly on the production of security. This unchallenged monopoly inevitably grows [399] heavier and more oppressive. The process begins with an attempt to limit it by establishing a system akin to that which restricted the power of other corporations, also invested with a monopoly. Consumers of security have gained the right to negotiate the price and conditions of this service. But, as we have seen, the two parties rarely agree, and in the final analysis, they resort to force to settle their disputes.

This solution has not favored security consumers. By the end of the 18th century, the corporations or houses holding political sovereignty had succeeded everywhere, except in England, in recovering the integrity of their monopoly, and this led to a general lowering of the quality and increase in the price of security, or of the guarantee of individual sovereignty. The French Revolution arrived and its first result was to give victory to the consumers. The political establishment that produced security fell into their hands, and they had to find ways to provide this service. This issue had three different solutions: 1) keeping the old political establishment, returning to the system of guarantees and checks, used in the Middle Ages and preserved and improved upon in England; 2) regressing to the system of primitive mutual societies, or security production by the consumers themselves; 3) abolishing political servitude altogether and leaving competition to provide the guarantee of individual sovereignty.

The second system prevailed and still prevails today with various applications and temperaments, and one can easily see the reasons why it prevailed. Consumers had [400] suffered from the abuses of the monopoly; it was natural for them to think that the simplest and most effective way to avoid the return of these abuses was to produce security themselves—collectively, since it was not possible to produce it otherwise. Thus, we see consumers of bread, in areas where the tax has been abolished and competition remains insufficient, establish cooperative bakeries, in other words, mutual societies for bread production. But it is rare that these mutual societies, although freely instituted, without anyone being forced to join, succeed in achieving their goal, namely producing bread of better quality and at a lower price than the bakeries of the old system, and they commonly end up dissolving or returning to the economic regime of ordinary businesses, either individual or collective. Even less successful have been attempts to establish lasting, economic mutual societies for the production of security, and it suffices to glance at their constitution and functioning to realize this failure.

What are the elements that make up political mutual societies, or so-called national ones? They consist of populations of diverse origin, occupying a territory conquered by the governing societies of the old regime, and gathered together without their consent, or even despite themselves. These populations were declared owners (apparently under the right of conquest) of the political establishment they were once subject to, after this establishment had been confiscated from its legitimate owners, and they were entrusted with its management at their own expense, risk, and profit, with either a portion of their members or all of them granted the right to participate in its management. But first, does not this collective sovereignty which has been artificially constructed and [401] made obligatory, just like the one it replaces, constitute a violation or a form of "servitude" imposed on individual sovereignty? If I am sovereign (and was not the revolution made to free me from political servitude, that is, to restore my sovereignty in its entirety?), if I am sovereign, and as such, the owner and free agent of my person and my property, by what right can you impose the obligation to associate with certain individuals rather than others to guarantee my person and my property? Would it be because, in the time when we were subjected in common to a political servitude, when we were forced, each and every one of us, to ask the corporation or house with the monopoly for our security, we were placed under the same yoke? What good would it do to have shaken off this yoke if it is only to replace it with another, even if it were the collective servitude of serfs, into which we were included without our consent and often despite ourselves? By dispossessing the corporation or house we were subjects of, do you claim to have restored the share of sovereignty it had taken from us? Very well! But then, you should have allowed us to use it freely to produce our security ourselves, individually—or by associating with others as we see fit, assuming that individual production was impossible. Or you should have allowed us to seek a society or a house of our choosing to provide this essential service and to freely contract with them. But to force us to be part of a mutual society composed of all the former subjects of the confiscated state, was this not as if, after abolishing the corporation with the monopoly on bread production, and thus freeing us from the obligation of procuring our bread solely [402] from the local bakery, we had been forced to operate this establishment, transformed into a obligatory cooperative bakery, bear its costs, cover its losses, and buy our bread solely from it? Was this not replacing one servitude with another?