GUSTAVE DE MOLINARI,

Thoughts on the Future of Liberty (1901-1911)

The English language edition (2025)

Gustave de Molinari (1819-1912) |

|

[Created: 15 March, 2025]

[Updated: 6 May, 2025] |

Source

, Thoughts on the Future of Liberty (1901-1911). The English language edition. Edited by David M. Hart (The Pittwater Free Press, 2025).http://davidmhart.com/liberty/FrenchClassicalLiberals/Molinari/Articles/FutureLiberty/index-English.html

Gustave de Molinari, Thoughts on the Future of Liberty (1901-1911). The English language edition. Edited by David M. Hart (The Pittwater Free Press, 2025).

The original French version of this collection was put online in 2023:

Gustave de Molinari, Thoughts on the Future of Liberty (1901-1911). Edited by David M. Hart (The Pittwater Free Press, 2023). [HTML]

See also my paper "Gustave de Molinari and the Future of Liberty: ‘Fin de Siècle, Fin de la Liberté'?" (2001, 2021). A paper presented to the Australian Historical Association 2000 Conference on "Futures in the Past", The University of Adelaide, 5-9 July, 2000. [Online] (abc). This contained the three French pieces as an Appendix. [HTML] .

- Gustave de Molinari, "Le XIXe siècle", Journal des Économistes, Janvier 1901, 5e série, T. XLV, pp. 5-19. [facs. PDF]

- Gustave de Molinari, "Le XXe siècle", Journal des Économistes, Janvier 1902, 5e série, T. XLIX, pp. 5-14. [facs. PDF]

- G. de Molinari, Ultima verba: mon dernier ouvrage (Paris: V. Giard & E. Brière, 1911). "Préface," pp. i-xvii. [facs. PDF]

This book is part of a collection of works by Gustave de Molinari (1819-1912).

Table of Contents

The Nineteenth Century↩

Source

Gustave de Molinari, "Le XIXe siècle", Journal des Économistes, Janvier 1901, 5e série, T. XLV, pp. 5-19.

Text

[5]

I.

The characteristic feature of the century that has just ended, what distinguishes it from all those that preceded it, is the extraordinary development of man's productive power. Through the conquest and subjugation of mechanical and chemical forces, added to or substituted for his physical strength in the work of production, he has been able to increase, in proportions that would once have seemed unbelievable, the material things of life. One can get an idea of this progress, achieved especially in the second half of the century, by consulting the tables of the growth of wealth in the United States, the country where industry has reached its highest level of productivity. While in 1850, the wealth of the American Union was valued at only 7 billion 135 million dollars, or 308 dollars per capita, according to the last census of 1900, it had risen to 90 billion, or 1,180 dollars per capita. In the last decade alone, the increase had been 35 billion—a sum of wealth more considerable, according to Dr. Powers, than what the entire American continent had been able to accumulate from the discovery of Christopher Columbus until the beginning of the Civil War. There is undoubtedly something to be discounted in this American statistic, and we must humbly confess that Europe's wealth has not made such a prodigious leap in the past half-century; but we can infer, from tax revenue figures, without mentioning other indicators, that in all the countries where the old [6] industrial and agricultural tools of production have been transformed and renewed, wealth has increased at least twice as much as the population, despite the burdens and obstacles of all kinds that the vices and ignorance of governments, as well as those of the governed, place in the way of its natural and regular development.

This phenomenon can be explained if one considers the enormous amount of cheap labor that invention and successive improvements in the steam engine have provided us. It is estimated, at the very least, that the work of one horsepower is equivalent to that of ten men. [1] Now, official statistics inform us that the number of steam engines in France rose from 60,000 in 1840 to 6,300,000 in 1897. This means that a workforce equivalent to that of 63 million men has been placed at the service of French industry. And not only is this labor more economical—by the entire difference between the cost of coal, which feeds the machine, and the cost of plant or animal food for humans—but it also develops a power and achieves results that no deployment of human strength could match. One could amass ten times the human labor of an express train’s machine, yet one would barely achieve a speed ten times slower. And supposing that thousands of men, stationed within hearing distance, were employed to transmit a message, their labor would be powerless to rival the speed of the telegraph, while costing thousands of times more.

But the increase in the quantity of products and services that constitute wealth has not been the only, nor perhaps even the most important, result of the transformation of industrial machinery; it has had two other consequences of even greater significance: elevating the nature of the work reserved for man in the work of production and extending, along with the sphere of trade, that of human solidarity.

Machines provide only material labor, whose operations must be directed or at least supervised by human intelligence. If they relieve man from physical effort, [7] they require a constant application of his intellectual power and often engage his moral responsibility to the highest degree. A locomotive engineer and a switchman, for example, expend only a small amount of physical strength during their workday, but their attention must be ceaselessly focused on the operation entrusted to them. If their intelligence is not sufficiently engaged, if they have only a weak sense of responsibility, this lack of diligence in their duty can cause the loss of hundreds of lives, not to mention purely material damages. However, the exercise of intelligence and responsibility naturally develops the faculties involved, and thus, the intellectual and moral level of workers who direct or supervise machine labor appears in all industrial branches touched by progress as manifestly superior to that of mere laborers who function as machines.

Industrial progress has therefore not only increased the quantity of products, but it has also, so to speak, improved the quality of the producers. It has had yet another equally beneficial effect: extending and multiplying the ties of solidarity among men. In previous centuries, the sphere of solidarity scarcely extended beyond state borders. The members of each nation formed a mutual insurance society [2] against the risk of invasion and pillage—when they were not themselves invaders and pillagers. If they were interested in one another’s prosperity, they were not interested in that of members of other nations. On the contrary, they had an interest in weakening the forces and resources of the people with whom they were continually at war. This state of affairs changed, and solidarity replaced antagonism, when trade associated the interests of individuals belonging to different nations. Now, it was the increased productivity of industry that provoked and necessitated the expansion of trade. When labor, assisted by increasingly powerful machinery—and to borrow an example from Michel Chevalier’s report on the 1867 Exhibition, when the introduction of the circular knitting machine increased the number of stitches produced per minute in knitwear manufacturing from 80 to 480,000—the local market was no longer sufficient for such enormous levels of production; it became necessary to expand its market. This was the case in all industries where machine labor replaced manual labor. Then, [8] to meet this need for market expansion, an extraordinary demand arose for improved means of communication. Inventors, utilizing scientific discoveries, applied themselves to satisfying this demand; steam, then electricity, were employed to overcome the obstacle of distance. 780,000 kilometers of railways, 1,800,000 kilometers of telegraph lines, built almost entirely in the second half of the century, and steamship lines establishing regular communications between the most distant parts of the globe began the work of unifying the markets for products, capital, and labor.

Despite the obstacles this expansion of trade encountered in the interests tied to the old state of affairs, it continues with an irresistible force of momentum, and one can already appreciate its ultimate impact by comparing the state of development of economic relations among nations at the beginning and the end of the century.

We have only partial and uncertain data on the foreign trade of civilized nations in previous centuries; we only know that England’s trade in 1800 did not reach 2 billion francs, [3] and that the trade of all other nations combined barely equaled this figure, so that the entire civilized world’s trade did not exceed that of present-day Belgium. Mr. Levasseur recently estimated it at 87 billion for the period 1894–95, [4] meaning it would have increased at least twentyfold over the century. The international trade of capital has developed no less than that of goods. Admittedly, statistics provide no data on capital production before the rise of large-scale industry, and they still only approximate its current significance. Mr. Robert Giffen estimated the United Kingdom’s annual savings at 200 million sterling—5 billion francs—which may be excessive. But one can affirm with certainty that the productivity of savings has increased alongside that of industry, and it is known that the countries where capital production has particularly developed—England, France, Belgium, Switzerland, Germany—supply growing amounts of it [9] to the rest of the world. The transformation of industrial and agricultural production tools, not to mention military, naval, and terrestrial equipment, has required enormous amounts of capital, especially in the last quarter-century. The construction of railways alone has absorbed approximately 200 billion. But, as with the export of goods, the export of capital creates and multiplies ties of solidarity among peoples. Capital-importing countries have an interest in the prosperity of those that produce it, in order to obtain it in abundance and at low cost, and capital-exporting countries are even more interested in the prosperity of their debtors.

The development of production, driven by the creation of machinery that is both more powerful and more economical, has also expanded, though to a lesser extent, the markets for labor. Population growth has kept pace with the expansion of employment opportunities; it doubled in Europe over the course of the nineteenth century and, in addition, contributed to emigration in numbers that in a single year exceeded what had previously been supplied over an entire century. From 10,000 individuals in 1820, emigration rose to 871,000 in 1887, and over the span of eighty years, no fewer than 15 million white men relocated to other parts of the globe. These emigrants fertilized new lands with their labor and brought vast regions, whose natural resources had remained unproductive, into the domain of civilization. They established new nations, supplied Europe with raw materials and foodstuffs, expanded markets for European industry, and extended, along with the sphere of exchange, the solidarity of economic interests.

Such was the principal achievement of the nineteenth century and its greatest asset. It began replacing isolated and politically hostile states with nations economically united by ever-increasing and tighter bonds of trade. This expansion of trade also had the effect of internationalizing progress itself. As all nations now found themselves in competition, their industries were compelled to adopt every improvement made elsewhere, lest they be excluded from the global market or even from their own national markets. At the beginning of the century, these advancements, which multiplied production while reducing costs, were almost monopolized by England. After initially attempting to shield themselves from English competition through customs barriers, continental manufacturers realized the necessity of emulating their British rivals. Thus, [10] stimulated by British competition, the manufactured goods of France, Switzerland, and, more recently, Germany succeeded in crossing national borders in ever-increasing quantities.

Today, a new competitor has emerged: American industry, equipped with machine tools that further reduce production costs. Tomorrow, perhaps, Chinese competition will arise, adding its beneficial influence to that of American competition to spur Europe toward reforming the political, fiscal, and protectionist impediments that artificially inflate the cost of living.

Need we add that centuries will pass before humanity produces more than it can consume? Despite the extraordinary boost that harnessing an immense quantity of natural forces is giving to productive capacity, humanity remains poor—very poor. Production must at least increase tenfold before even modest comfort can be ensured for all.

Yet only through the expansion of the system of production and trade will labor, aided by nature's forces, be able to satisfy our needs with an ever increasing abundance, needs which even today are still so inadequately met. However, this system is extremely sensitive. As it expands and links more interests across different parts of the globe, disturbances such as wars and other calamities—stemming from the vices and ignorance of governments and individuals—which are felt at a single point in this expanded market will have repercussions throughout all itsother parts. These causes of disorder and ruin have continued to multiply and even worsen over the course of the century. Compared to the progress that forms its assets, they have also created liabilities that have absorbed, if not all, then too large a portion of the gains of progress. [5]

II.

It might seem that the extraordinary growth of international trade, by fostering solidarity of interests among nations and increasing the need for peace, should have made wars less frequent. This hope appeared all the more reasonable given that industrial progress was daily expanding the ranks and wealth of [11] the managerial class of production, [6] granting it greater influence oil the government of the State. Yet this has not been the case. Wars were no less numerous in the nineteenth century than in the eighteenth, and they were far more destructive and costly.

We lack exact figures on the human lives consumed by war from the late reign of Louis XIV to the French Revolution, but estimating the toll at one million would likely be excessive. Armies were then small, and recruitment difficulties compelled generals to spare their soldiers' lives. The Revolution changed this by making unlimited numbers of conscripts available to republican and imperial commanders. This granted them a decisive advantage over their adversaries, accustomed to the older system. Moreau famously remarked that Napoleon won battles at the cost of 10,000 men per hour. Likewise, the underdevelopment of public credit forced governments to limit their armaments and make peace as soon as their treasuries were depleted. The slow growth of public debts in the eighteenth century provides clear evidence of this. According to statistics compiled by Dudley Baxter, public debts increased by only 5 billion francs between 1715 and 1793. [7] However, from that time onward, the destructive industry of war advanced even more prodigiously [4] than the productive industries. The wars of the Revolution and the Empire consumed approximately 5 million lives, a toll that grew significantly in the second half of the century. Summing up war casualties since the Revolution, one arrives at the monstrous figure of 9,840,000 deaths—nearly 120 million across the nations of our civilization. Capital consumption has risen even more rapidly than the loss of human life. Beyond the sums annually extracted through taxation, war and armed peace—meaning constant preparation for war—have contributed at least 100 billion francs to the increase in public debts over the course of the century.

Yet what once justified war no longer exists. As long as civilized peoples faced destruction or dispossession by barbarian invasions, war was a necessity—an unavoidable insurance against an ever-present danger.

But thanks to advances in military technology and the art of destruction—advancements which, incidentally, have been no less useful than those in industry and production—this danger has vanished. Civilized nations now invade and appropriate the regions once occupied by their former invaders. War is no longer imposed upon them; it is a matter of choice.

The question, then, is whether they still have an interest in choosing war. That interest undoubtedly existed for aristocracies that gained additional serfs or subjects through conquest of a State or a province, thus increasing their revenues through forced labor, tributes, or taxes. But what could a rich province or state yield to a nation that no longer relies on plunder or the exploitation of slaves, serfs, or subjects, but instead derives its livelihood from cultivating its soil and practicing honest industry? Has not the experience of every war waged in the past century demonstrated that they cost the victors more than they gained? How, then, can rational beings who understand accounting continue to engage in an enterprise that operates at a loss? Such behavior would indeed be inexplicable, an aberration fit for the study of psychiatrists, if the producers—industrialists, capitalists, and workers who bear the costs of all wars—possessed [13] any real influence over national governments. However, despite revolutions, unifications, and political constitutions aimed at liberating nations from exploitation bt a native or foreign caste, only the form of governments has changed, while their substance remains the same. Particular interests have continued to come together in order to impose their will on the general interest. Throughout Europe, the interests which are engaged in preserving a state of war, namely military and political interests, have retained their dominance. Armies and government bureaucracies, which under the old regime provided the sole market for the governing class, continue to be regarded as superior to other forms of human endeavor. They still attract the offspring of the former ruling class as well as social climbers from the new, forming a powerful coalition of interests in republics and monarchies alike. Since war, as in the past, remains a source of profit and prestige for professional soldiers, it is only natural that they advocate for it. "Do you know my army well?" Napoleon once asked. "It is a cancer that would devour me if I did not feed it." [8]

This green pasture is all too readily supplied by the holders of political power, heads of state, politicians, since e war silences all opposition and postpones, if only temporarily, domestic crises—though only to worsen them later. It is thus no surprise that war has survived the dangers that once threatened civilization, and it is likely to persist as long as this destructive industry holds greater political influence than the productive industries that sustain it and suffer its damages. One can also understand how the extraordinary increase in industrial productivity, by augmenting the wealth and power of nations, has led to a corresponding development of the apparatus of war.As long as the risk of war persists and may materialize at any moment, driven by interests that demand their bit of pasture, it is necessary to arm oneself against this risk, to counter the enemy with a destructive force at least equal to his own, and consequently, to increase it in proportion to the forces and resources created and developed by industrial progress. This proportion has certainly been reached, if not exceeded, under the current system of armed peace in Europe.

[14]

Moreover, the enormous military forces required by the system of armed peace cannot remain perpetually idle without becoming ineffective. A prolonged period of inactivity deteriorates the workshops of destruction just as it does those of production. War is necessary for the health of armies. Thus, it is taught in military academies that each generation must have its own war. However, as public debts have become increasingly burdensome and the cost of war between nations of equal strength has risen so dramatically, it has become more and more difficult to satisfy the professionals of the military art. What has been done? In the last quarter-century, wars, now too costly between civilized nations, have been replaced by wars of conquest, exploitation, or plunder outside the domain of civilization. European governments have divided up Africa among themselves, and today they are pillaging China under the pretext of opening new markets for industry and extending the benefits of civilization to the Negroes and, of course, the Chinese. But it is enough to add up and compare the costs of conquering and maintaining colonies, protectorates, and spheres of influence with the profits that industry and commerce derive from them to understand the fallacy of this pretext. Conquest, subjugation, and fiscal and protectionist exploitation do not expand industrial and commercial markets; rather, they restrict them by increasing the burdens that war, naval, and colonial budgets place on all branches of production. As for civilization, is it truly through massacre and plunder that one can make its benefits appreciated by the so-called "Barbarians"?

To the costs of armament, which are entirely disproportionate to the real security needs of civilized nations, and to the wars waged to satisfy the interests of castes, parties, or dynasties, one must add, in the liabilities column of the nineteenth century, the continuous rise in the cost of services that governments seize for themselves at the expense of private enterprise, as well as the costs of a so-called protective industrial policy that provides no real service.

The revolutions and political reforms that sought to remove the monopoly of the government of nations from the noble and clerical oligarchies of the old regime have, in fact, done little more than successively expand this monopoly, thereby granting an ever-larger class the power and influence naturally associated with possession of [15] the state. The positions that once served as markets for the old ruling class were no longer sufficient for the new one. It became necessary to multiply them to accommodate the growing demand. The expansion of state functions thus became a political necessity. Economists, naive and incapable of appreciating this kind of necessity, have in vain tried to demonstrate that state-produced goods and services cost consumers more than those of private industry; that state employees are recruited less efficiently, are less industrious, and offer worse service than private enterprises. None of these arguments have prevailed. Under the irresistible pressure of electoral and other influences, the State has expanded its functions and multiplied its officials, while the little States, such as municipal, departmental, or provincial governments everywhere followed the example of the big State. To cite only France, the number of public officials of all kinds there rose from 60,000 to 400,000 over the course of the century, and statism continues to spread to other countries, including England, as the expansion of the ruling class [9] increases the demand for government positions.

Under the old regime, in addition to the benefits derived from the monopoly of public offices, there were also privileges in taxation and feudal dues. These privileges and dues, after being abolished in their traditional forms, have gradually reappeared under new forms adapted to the interests of the dominant classes. Indirect taxes and monopolies, which primarily burden the politically less influential segments of the population, once accounted for only a third of state revenues in France, but have since risen to two-thirds. Customs duties, which had been lowered by the Treaty of 1786 under the influence of liberal doctrines propagated by Adam Smith's school in England and by Quesnay and Turgot in France, were later reinstated—first as instruments of war, then as instruments of protectionism, serving politically influential interests. For large landowners, they replaced feudal dues and were extended to include industrial property holders allied with them.

This coalition broke down in England, where agricultural interests, left to their own devices, succumbed to the pressure of the Anti-Corn Law League. Freed from the tribute it had been paying to privileged interests, the people were able to increase their consumption of essential and other consumer goods while also growing their savings. British industry, encouraged by [16] the expansion of consumption and stimulated by competition, experienced a remarkable boom. [10]

At first, other nations followed England’s example, and for a moment, it seemed that a new era of freedom and peace was about to dawn on the world. But the illusion was short-lived. Militarist and protectionist interests quickly [17] regained the upper hand. The American Civil War, by securing victory for the protectionist states, allowed them to raise tariffs at will. The Franco-Prussian War, by rekindling militarism and prompting a general increase in war budgets, forced governments to seek additional resources from their parliaments. The protectionist coalition seized this opportunity to reconstitute itself and set a price on its political support.

Customs tariffs have been raised in the dual interest of taxation and protectionism. In Germany, Italy, and France, duties on essential goods such as bread and meat have been increased to raise their prices by a third or even half, in the interest of landowners, while other tariff hikes on clothing materials, furniture, and transport, combined with a system of subsidies, have ensured a share of the benefits for their allies, the industrial proprietors, at the expense of the general population of consumers and taxpayers. To the taxes they owe to the state, people must add those they do not owe—levies that are, in reality, nothing more than old feudal dues transformed and modernized.

Thus, one can understand why the extraordinary increase in wealth, brought about by a remarkable flowering of progress, has not led to an equivalent improvement in the well-being of civilized peoples. The incompetence and vices of governments, militarism, statism, and protectionism have consumed a significant portion of this industrial surplus. Meanwhile, the ignorance and moral shortcomings of individuals—freed from the burdensome tutelage of servitude but still incapable of fully shouldering the responsibilities of liberty—have destroyed or rendered sterile another portion of these gains. It must be said: the masses, who lived from day to day on the product of their labor, lacked both the capacity and the resources necessary to make full use of their productive potential. As Adam Smith observed, the worker, deprived of capital, found himself in an unequal position vis-à-vis the employer—an inequality exacerbated by laws that forbade him from remedying it through association (in trade unions). On the other hand, he had to undergo the difficult apprenticeship of liberty; he had to regulate and restrain his present needs in anticipation of future necessities, provide for accidents and periods of unemployment, and fulfill all his obligations to himself and those dependent on him. Is it any wonder that he was often unable to meet this challenge? That, with wages [18] negotiated under unequal conditions and diminished by both the taxes he owed and those he did not owe, he too often succumbed under the weight of these burdens? And that, even as wealth increased, poverty and moral degradation spread?

Economists have studied these problems which have accompanied the transformation of industry and the emancipation of the working classes, tracing them to their true causes and advocating reforms to remedy them. But these reforms face powerful and intractable vested interests, and they do not offer an immediate or radical solution. Socialists, on the other hand, have found greater success by attributing the sufferings of the masses wholesale to a mysterious and formidable power, which they have branded as the tyranny of capital. They summon the working masses to overthrow this tyranny by means of a swift social revolution. Once the revolution is accomplished, authoritarian socialists—whether collectivists or communists—propose to entrust the state with reorganizing society, while anarchist socialists, by contrast, seek to abolish the state altogether. Yet despite their differences, both agree on one essential point: the confiscation of capital.

And this, at the dawn of the twentieth century, is the most popular solution to the social question.

III.

The nineteenth century bequeaths to its successor the inheritance of a billionaire. None of its predecessors has so greatly increased the wealth it received. But while it has expanded its domain and multiplied its stock of real and financial assets to proportions previously unknown, it leaves this immense fortune heavily burdened with debt. It also bequeaths to its heirs—not to mention the vices common to all centuries, which it has scarcely attempted to correct—deeply ingrained habits of waste and extravagance.

The twentieth century will undoubtedly continue to increase industrial productivity and multiply wealth. Its scientists, inventors, industrialists, capitalists, and workers will not be idle; they will labor relentlessly to expand the stock of civilization’s resources and material well-being. But one may fear, unfortunately, that the efforts of these industrious architects of production will continue to be thwarted, by [19] the blind egoism of vested interests, and that the fruits (of their labour), as usual, will be diverted from their beneficial purpose and misused for harmful ends.

While science and industry multiply wealth, militarism, statism, and protectionism—and, in due course, socialism—combine to destroy it and drain its source. The revenues that the annual labor of nations contributes to government budgets no longer suffice to meet state expenditures. To balance their accounts, governments now burden the labor of future generations with debt. Europe's public debts have doubled in the second half of the century. If they continue at this rate, they will reach at least 400 billion by the year 2000. No matter how much production advances, will this burden not eventually exceed the strength of the producers? Let us therefore hope—and this is the most useful wish we can make for our descendants—that the twentieth century will not only excel, like its predecessor, in generating wealth, but that it will also learn to use it more wisely.

G. DE MOLINARI

Endnotes to 19th Century

[1] A man, under the best possible conditions, can perform in ten hours only 220,000 kilogram-meters of work. In one hour, a one-horsepower machine performs 270,000 kilogram-meters, which is more than a man accomplishes in ten hours. It can therefore be asserted that, in general, it takes ten men to perform the work of a one-horsepower machine. (Henri De Pahville, Causeries scientifiques).

[2] (Editor's note.) Molinari uses a key phrase in his theory of the private "production of security" which dates back to an article and book he wrote in 1849. Here he says "une société d'assurance mutuelle" which was one ofd the organisations which he thought would eventually replace the monopoly government provision of "security".

[3] 30,570,000 pounds sterling in imports and 43,152,000 pounds sterling in exports.

[4] L'influence des voies de communication au XIXe siècle, by E. Levasseur, p. 12.

[5] (Editor's note.) In his 1852 lecture on "Revolution and Despotism" Molinari argued that economists needed to be the "bookkeepers of society" and draw up a balance sheet of the costs and benefits, the losses and profits, of various government policies and historical events such as the French Revolution and the rise of dictators like Napoleon III. Here he is summing up the costs and benefits of the entire 19th century. See Gustave de Molinari, Les Révolutions et le despotisme envisagés au point de vue des intérêts matériels; précédé d'une lettre à M. le Comte J. Arrivabene, sur les dangers de la situation présente, par M. G. de Molinari, professeur d'économie politique (Brussels: Meline, Cans et Cie, 1852). [Online]

[6] (Editor's note.) Molinari uses an unusual (for him) phrase to describe this "class": "la classe dirigeante de la production" (the managerial class of production). He had previously made a sharp distinction between the ruling and exploitingclass who lived off the taxes of the productive and exploited class. Here the distinction is less clear cut, suggesting that the "class of managers" of industry has made a deal with the elite who controlled and ran the state to cooperate in sharing the soils of political office.

[7] According to the research of Mr. Dudley-Baxter (in his work National Debts), though in part conjectural for the more distant periods, the total national debts of civilized countries amounted, in 1715, to 7.5 billion francs. In 1793, the total public debt of nations in our civilised group, including the United States and British India, had risen to 12.5 billion francs, with England alone owing more than half of this sum. From 1793 to 1820, national debts increased far more than in the previous eighty years: by the latter date, the total can be estimated at 38 billion francs, of which 23 billion belonged to England alone. From 1820 to 1848, the world enjoyed a period of deep peace, so that by 1848, national obligations amounted to only about 13 billion francs. However, the Revolution of 1848, the wars of the Second Empire, and other events brought this sum to 97,774,000,000 francs by 1870. Finally, it is estimated that the total debt of the more or less civilized nations currently exceeds 130 billion francs. (Paul Leroy-Beaulieu, Traité de la science des finances, Vol. II, Chap. XIV: Les dettes des grands États).

[8] Henri Welschlinger, Journal des Débats, July 11, 1900.

[9] (Editor's note.) Molinari uses here the term "la classe gouvernante" (the ruling or governing class).

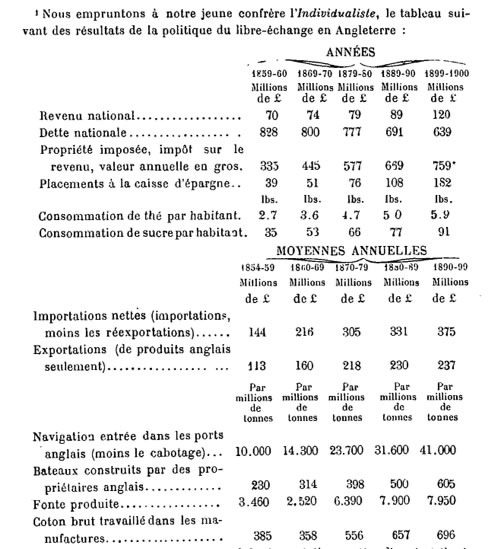

[10] We borrow the following table from our young colleague L'Individualiste, which details the results of the free trade policy in England:

Gold Accumulated: From 1858 to 1899, total net gold imports amounted to £148,000,000, or 3,700,000,000 francs. One pound sterling (£) = 25 francs. One English pound weighs 497 grams.

This last figure (of 759 in line 3) would have been even higher, but recent fiscal changes have exempted certain small incomes from taxation.

The Twentieth Century↩

Source

Gustave de Molinari, "Le XXe siècle", Journal des Économistes, Janvier 1902, 5e série, T. XLIX, pp. 5-14.

Text

[5]

I.

The distinctive character of the nineteenth century, as we stated in our review last year, what sets it apart from all the centuries that preceded it, is the prodigious increase in man's productive power—in other words, his capacity to create wealth. But as is often the case with the newly rich, the peoples whose fortunes suddenly increased thanks to an extraordinary blossoming of material progress did not simultaneously acquire the moral capacity necessary to govern the use of this wealth honestly and beneficially. They have displayed the crude appetites and vices of parvenus. The classes in control of the machinery for making laws have used it to satisfy their particular interests at the expense of the general interest: militarism, statism, and protectionism have combined to divert from their proper use, destroy, or sterilize the fruits of progress. It is scarcely believable! Even as the utility of the costly military apparatuses bequeathed by the old regime to the new diminished, they were reinforced and expanded instead of being reduced. While advances in destructive power, keeping pace with those in productive power, definitively ensured civilized nations against the risk of barbarian invasions, and while at the same time war ceased to be a profitable means of acquiring wealth and became a source of debt [6] and ruin, military expenditures reached increasingly formidable proportions, and war consumed, over the course of the nineteenth century, ten times more men and capital than in any previous century. Likewise, while the development of the spirit of enterprise and association made it possible to leave public works and services to the free initiative of individuals, the state was seen encroaching more and more upon the domain of private activity, replacing the fruitful competition of industries with the costly stagnation of its monopolies. The less necessary state intervention became, the more the plague of statism spread! [11] Finally, while the multiplication and marvelous improvement of transport systems, facilitating the movement of productive agents and materials, everywhere equalized industrial conditions and, by bringing previously isolated consumer markets into constant communication, removed the original justification for the protectionist system, the monopolistic spirit of the governing and law-making classes [12] raised and multiplied the barriers of protectionism.

Judging by its beginnings, the twentieth century will follow its predecessor’s example in these three respects. Over the past year, government expenditures across the civilized world have increased as usual, and, as usual, this increase has affected the least useful areas. Nowhere do the services of justice and policing, which concern the security of individuals, receive allocations proportionate to the risks to which life and property are exposed. As a result, nowhere is there a decline in these risks, and the industry of criminals of all kinds remains as thriving as ever. Although the external risks that could threaten individual life and property from foreign invasions have become nearly nonexistent—since experience has shown that war today costs more than it yields—the budgets for war and the navy continue to grow. They increase not in proportion to the rising risks they are meant to address, but rather to their diminishing likelihood. Every day, new battleships costing at least thirty million apiece appear in the dockyards, serving no purpose other than grandiose and futile displays. In this regard, Spain has provided a characteristic example. Rather than reducing its land and naval military budgets by the amount it once spent on the defense of the colonies it has lost, and thus achieving [7] much-needed savings for its depleted finances, it has increased them, with its politicians—both liberals and conservatives—declaring these now-useless expenditures "untouchable." As for the protectionist budget, which operates alongside the state budget, it has continued to expand as well. In France, the customs commission has actively pursued the completion and refinement of the Méline tariff; subsidies for the merchant marine have been renewed, save for a slight adjustment; the temporary import regime has been modified in a more restrictive direction, and so on. In Sweden, tariffs on agricultural goods and most industrial products have been raised; even in the Netherlands, the traditional policy of free trade is now seriously threatened by the hunter of the protectionists for more. In Germany, the government, dominated by an agrarian feudal class, has submitted to the Reichstag a tariff bill designed to increase land rents at the expense of workers' wages.

How can civilized nations tolerate this policy of waste and privilege, which in fifty years has more than tripled their national debts, [13] multiplied and worsened both the taxes they owe and those they should not have to pay? The explanation for this phenomenon, which does little credit to their morality and intelligence, becomes clear when one closely examines their social composition. At least nine-tenths of their populations consist of individuals concerned solely with their immediate personal interests, ignorant of or indifferent to the general and long-term interests of the nation, let alone [8] those of humanity as a whole. In countries such as Russia, where the majority of the governed lack political rights—which, in any case, they would be incapable of exercising—the government is in the hands of a class that is half-bureaucratic, half-land-owner and industrialist, deriving the bulk of its income from the budgets of the State and the protectionist system. In so-called constitutional countries, where a more or less significant portion of the governed possess the right to vote, the vast majority either use this right for personal gain or abstain from using it altogether. Provided that it serves the interests of the most influential groups, the government can sacrifice or neglect all others with impunity. Now, the most influential interests belong precisely to the class from which is recruited the high-ranking civil and military officials who depend on the state budget for their livelihood, as well as the landowners and industrialists who divide among themselves the budget of the protectionist system. How, then, could this budget-eating class [14] not push for the continuous expansion of expenditures from which it profits, and how could it fail to use the power of the state, which it controls, to multiply them?

And let us note that the power of the state, embodied in the government apparatus, has been singularly reinforced by the advances in the means of mobilizing its forces and resources. This power is now so great that it defies all individual resistance and gives modern governments a capacity for oppressing minorities far greater than that of the governments of the old regime. When a sovereign of the past took possession of a province, whether by war or inheritance, he prudently refrained from touching the particular institutions of his new subjects. He respected their customs and their language. When Louis XIV seized Alsace, he even refrained from altering its customs regime. Alsace remained a so-called "foreign province with special status," and as such, it was exempt from the burdens of Colbert's protectionist tariff. Things are no longer the same today. Governments now make ruthless use of the right of the strongest against populations that fall under their rule. Thus, the Russian government, in disregard of its formal commitments, has subjected Finland to the autocratic regime of the rest of the Empire, and the German government has forbidden the Danes of Schleswig and the Poles of Posen from using their native language, enforcing this prohibition—at once inept and unbearable—through the most insolent and brutal abuse of power.

[9]

II.

Despite the rapid expansion of state budgets, they may soon be surpassed by the protectionist budget, thanks to the refinements that the spirit of monopoly has introduced into the protectionist system through the invention and spread of trusts, cartels, and syndicates.

The trusts in the United States, the cartels in Germany, and the syndicates and sales cooperatives in France—though differing in organization—are all structured with a dual objective: first, to reduce the costs of production and distribution, and second, to raise prices to the level of protective duties and keep them there by eliminating domestic competition, so that protected industries may capture the full benefit of protectionism. Experience has shown that it is not enough to exclude foreign competitors from the domestic market in order to raise prices by the full amount of the tariffs above the general market rate. Indeed, when prohibitive tariffs immediately grant extraordinary profits to protected industries, they attract an overabundance of enterprise and capital, leading to overproduction and a price drop that brings prices back to the general market rate, sometimes even pushing them below it. Then, the initial windfall profits are followed by ruinous losses. The collapse of the weakest enterprises may, in truth, clear the market of excess production and restore prices, but this increase in prices, by again attracting entrepreneurs and capital, triggers another downward cycle.

Thus, the protectionist system generates a permanent state of instability, in which a period of rising prices caused by the exclusion of external competition is followed by a series of alternating contractions and expansions of domestic competition. During periods of contraction, prices may rise to the full extent of the protective duties, and in the case of essential food products, reach famine levels. The duties then operate at full force, and producers reap the maximum possible profits from protectionism. During periods of expansion, however, the duties cease to function effectively, producers sell at a loss, and many go bankrupt. It is precisely to prevent [10] these disastrous fluctuations, to raise and stabilize prices at the level of protective duties, that American industrialists have sought to eliminate domestic competition by forming trusts that consolidate competing enterprises within the same industry. In some cases, they have entirely achieved their objective: the Standard Oil Company and the Sugar Trust supply nearly all the petroleum and sugar consumed in the United States and effectively control the market. The latest and most colossal trust, the United States Steel Company, established last March through the merger of eight industrial groups, similarly dominates the principal branches of metallurgy. This enormous trust was created with a capital of 1.1 billion dollars, and the total capital of all U.S. trusts is estimated at 7 billion dollars, or 35 billion francs. The German cartels and French syndicates, such as the sugar syndicate and the metallurgical cooperative in Longwy, have not yet reached the scale of the American trusts, but all—trusts, cartels, and syndicates alike—pursue the same objective: to capture the full benefits of protectionism by preventing domestic competition from interfering with the operation of protective tariffs.

In Germany and France, these still-limited attempts to monopolize the market have not seriously stirred public opinion. In the United States, however, the reaction has been quite different. As usual, the alarmed public turned to the government to defend its interests against the suppression of domestic competition. In most U.S. states, laws have been enacted to prevent the formation of trusts or limit their power. But these laws, which shared the common flaw of obstructing the legitimate and useful development of enterprises, have remained powerless against the maneuvers of monopolistic interests: for every form of combination outlawed by legislation, trusts have substituted legally unassailable forms of association. Yet nothing would be easier than to strike a fatal blow against them: instead of passing laws to regulate trusts, it would suffice to repeal the law that artificially restricted competition by surrounding the domestic market with a tariff wall. Did not the founder of the Sugar Trust himself acknowledge the effectiveness of this remedy when he admitted that the tariff is "the father of trusts"?

But customs tariffs, whether viewed as tools of taxation or protection, are fiercely defended by powerful interests. Everywhere, they provide a substantial share of the resources that sustain militarism and statism, as well as [11] the entire levy that protectionism extracts from consumers and taxpayers. Only England has stripped its tariff of all protectionist character, but its example was followed only momentarily, and one would be hard-pressed to affirm that the beneficial reform achieved through the efforts of Cobden, Robert Peel, and Gladstone is fully secured against a resurgence of protectionism allied with imperialism.

III.

However, it would be unjust to hold the ruling classes responsible for all the ills afflicting our societies, as socialists habitually do. A portion of these ills, and perhaps the greater part, originates in the incapacity and immorality of individuals in governing themselves. [15] The budget for debauchery and drunkenness, for example, in most civilized countries, equals or even exceeds the budget for militarism. But regardless of how the responsibility for the errors and vices of the government of society and the government of the individual is apportioned, these errors and vices invariably cause a waste of wealth that ultimately falls most heavily on those least able to bear the loss. Hence the discontent and malaise that, at first glance, seem inexplicable in an era when progress in every field allows people to acquire the necessities of life in exchange for an ever-diminishing amount of labor and hardship.

It is from this discontent and malaise, following upon excessive and premature hopes, that socialism was born.

In its early stages, during the first part of the last century, socialism appeared as a collection of mere utopias, conceived by benevolent but delusional minds. Ignoring the natural conditions of the existence of society, the Saint-Simons, the Fouriers, and their disciples dreamed of reconstructing it according to a new plan, but they never considered resorting to force to realize their utopias. They were convinced that simply propagating their ideas, like apostles spreading a new gospel, would be enough to see them embraced without resistance—for what they were bringing to humanity was universal happiness. Moreover, where could they have found the force [12] necessary to impose their vision? They could hardly expect it from the classes that held power and wealth. As for the multitude (of people), then dispersed in small, disconnected groups spread across the workshops of small-scale industry, they were in an amorphous state and could provide no real base of support in the first half of the nineteenth century. Lacking any political rights, they were of no consequence in the State.

But in the second half of the century, the situation changed completely. Large-scale industry gathered thousands of workers into vast workshops, while advances in communication and transportation brought them even closer together. The laws against workers' unions were abolished, and political rights extended to the lower strata of society. The restricted suffrage that had once granted a monopoly of political power to the upper and middle classes was replaced by universal suffrage. Under these new conditions, what Saint-Simon called "the most numerous and poorest class" was no longer an inconsequential cloud of dust but had become a solid mass in the process of organizing itself. It provided socialism with the support it had lacked in its early days. In turn, socialism adapted itself to the state of mind of its new clientele. And how could this state of mind be any more enlightened or moral than that of the upper and middle classes? Following their example, the workers democracy [16] has inherited the doctrine from the time when war was the most lucrative means of acquiring wealth—when, consequently, one person's gain necessarily meant another's loss. [17] It was thus naturally convinced that it can only grow richer by stripping the wealthy. Consequently, what it demands from the law is the confiscation of capital, or at the very least, placing capital under the control of labor. Collectivism has answered this demand. In vain do the classes still in possession of the power to make the laws attempt to counter this danger by offering the democratic Cerberus the sop of so-called labor laws—laws limiting the length of the workday, soon to be followed by a minimum wage law; laws shifting the natural responsibility for workplace accidents from employees to employers; laws imposing upon employers and the state a share of the burden of workers' pensions, and so forth. These offerings, born of fear, do not deter the clientele of collectivism, for collectivism promises them the totality of the benefits that the bourgeois state offers only in part. And even then, it is uncertain whether that partial benefit will not be clawed back through the inevitable economic repercussions of the natural laws which govern taxation and wages.

[13]

IV

To the two parties that contested possession of the State and the making of laws throughout the nineteenth century—one, the conservative party, primarily drawn from the ruling class of the old regime; the other, the liberal party, arising from the bourgeoisie enriched by industry—there is now added a third party, representing the working class newly endowed with political rights: the socialist party. It even seems that these three parties will soon be reduced to two. Are we not witnessing the liberal party dissolving everywhere, its elements splitting along lines of economic interest and joining either the conservative or the socialist party? One can thus foresee that the struggle for control of the state and the making of laws, which occupied the nineteenth century as a contest between the conservative and liberal parties, will continue in the twentieth century between the conservative and socialist parties. One can also predict that this struggle will be no less fierce and, in all likelihood, no less pointless than its predecessor, producing the same series of revolutions and coups d'état, punctuated by the bloody distractions of foreign wars and colonial expeditions—events that formed what might be called the liabilities of nineteenth-century civilization. [18]

If these predictions—drawn from the logical sequence of events—were to come true, they would justify the pessimism that has replaced the optimism of the early days of the new political and economic order. It is all too evident that the struggle for control of the government will only grow more intense and that, on the day the socialist party gains the power to make laws, it will wield that power with far less restraint than the so-called liberal and reformist party whose legacy it is inheriting. It will cut deeply into the body of private property and individual liberty. It will break or distort the delicate mechanisms [19] that regulate the production of life’s necessities...

But can't we entertain the hope that the inevitable failure of attempts to artificially reorganize society, and the resulting increase in misery and suffering, will give rise to a healthier understanding of the role of the law? Might it not lead to the formation of a party that is both anti-socialist and anti-protectionist? We realize that the creation of a party offering its "officers and soldiers" [20] neither "political jobs", [21] nor privileges and subsidies, nor monopolies (such as a government tobacco shop), might at first seem [14] like an idealistic enterprise. One recalls the words of President Jackson: "To the victors belong the spoils!" Why would politicians fight if there were no spoils? Such is the reasoning of Jacksonian politicians. But whether they like it or not, there will always be men willing to serve a just cause without an expectation of personal gain. And for this reason, we do not despair of seeing, in the twentieth century, the creation of a party that was missing in the nineteenth: the party of the least government. [22]

G. DE MOLINARI

Endnotes to 20th Century

[11] (Editor's Note.) Molinari uses the phrase "la lèpre de l'Etatisme".

[12] (Editor's Note.) Molinari uses the phrase "des classes gouvernantes et légiférantes" (the governing and law-making classes).

[13] In our May issue, we reproduced a report by Lord Avebury to the Statistical Society regarding the enormous and continuous increase in public debt. From 42 billion francs in 1848, the debts of civilized states rose to 117 billion in 1873, 128 billion in 1888, and 160 billion in 1898. The largest share—one might say almost the entirety—of these debts has been used to finance war or the military preparations known as "armed peace." According to Lord Avebury, military and naval expenditures by the great European powers have increased over the past twenty years in the following proportions:

| Millions | Millions | |

| Great Britain | 718.8 | 1,707.0 |

| France | 752.4 | 957.5 |

| Germany | 506.3 | 945.0 |

| Russia | 848.1 | 901.5 |

| Italy | 251.4 | 434.9 |

[14] (Editor's Note.) Molinari uses the phrase "cette classe budgétivore" (this budget-eating class).

[15] (Editor's Note.) Molinari uses the phrase "le gouvernement de l'individu par lui-même" (the government of the individual by himself/herself).

[16] (Editor's Note.) Molinari uses the phrase "la démocratie ouvrière".

[17] (Editor's Note.) This was a phrase used by Montaigne in one of his essays which so troubled Bastiat that he wrote several reputations of the false economic ideas which lay behind this.

[18] (Editor's Note.) In his lecture on Les Révolutions et le despotisme envisagés au point de vue des intérêts matériels which he gave in 1852 Molinari introduced the idea that economists needed to be "the bookkeepers" of history and politics who would tally up the "profits and losses", the "assets" (l'actif) and "liabilities" (le passif)of any given society, and come to some conclusion whether or not revolutions and coup d'états had been beneficial to the people. See, Gustave de Molinari, Les Révolutions et le despotisme envisagés au point de vue des intérêts matériels; précédé d'une lettre à M. le Comte J. Arrivabene, sur les dangers de la situation présente, par M. G. de Molinari, professeur d'économie politique (Brussels: Meline, Cans et Cie, 1852). Deuxième Partie, pp. 81-152

[19] (Editor's Note.) Again, Molinari uses an expression used by his friend and colleague of 50 years previously, Frédéric Bastiat, who discussed "le méchanisme social" (the social mechanism) in terms of “les rouages, les ressorts et les mobiles” (the cogs, the mainspring, and the driving or motive force).

[20] (Editor's Note.) I think Molinari means by this expression "ses offers et ses soldats" (its officers and soldiers) a sarcastic reference to the senior and junior members of the party who seek jobs in the administration, government contracts, and other benefits once the party is elected to government.

[21] (Editor's Note.) Molinari puts the word "places" (government positions or jobs) in quotes.

[22] (Editor's Note.) Molinari uses the phrase "le parti du moindre gouvernement". "Le moindre" could mean either "the lesser" or "the least". Given what Molinasri has said elsewhere, I believe he meant "the least" (possibly even "none").

Gustave de Molinari’s “Last Words” (1911) (Extracts)↩

Source

Gustave de Molinari, Ultima verba: mon dernier ouvrage (Paris: V. Giard & E. Brière, 1911). "Préface," pp. i-xvii.

Text

[i]

PREFACE

Having almost reached the limits of human life—I am now in my 92nd year—I am about to publish my last work. It concerns everything that has filled my life: free trade and peace. Yet, although the sphere of peace has prodigiously expanded and sovereigns pour out lavish statements about peace, these fundamental ideas are declining everywhere. However, it seemed in the middle of the 19th century that they were henceforth destined to govern the civilized world. Did not King Louis-Philippe say in his response to a deputation "that war was too expensive and would no longer be waged"? These peaceful inclinations had precedents: Henri IV, indoctrinated by Sully, had declared that there would be no more wars between Christian princes. In the 18th century, the Abbé de Saint-Pierre [ii] became the beneficent disseminator of pacifist ideas, and Abbé Coyer urged the nobility to adopt a more lucrative profession than the trade of arms. Such was the strength of the pacifist movement at that time that Turgot unhesitatingly voted to maintain peace with England, despite the bellicose inclinations of the young nobility, who went to help secure the independence of the English possessions in America. At the end of hostilities, under the influence of the Physiocrats and perhaps Adam Smith, the 1786 treaty bound France and England through an agreement that would today be considered a free-trade triumph.

***

But the Revolution was soon to postpone for a long time the application of the principles of peace and liberty. After twenty-five years of war, the European powers celebrated at the Congress of Vienna the return of general peace and reduced their war apparatus to two billion. — They did not delay in increasing it: today, in all of civilized countries, military and naval expenditures exceed twelve billion in peacetime. France's budget, which on the eve of the [iii] Revolution was about five hundred million, now exceeds four billion, the majority of which is used to prepare for war or to pay off debts left by previous wars. — However, the mid-19th century witnessed a resurgence of the military spirit; conflicts multiplied: there were the wars of Italy, Crimea, the Austro-German war, the Civil War, the suppression of the Sikh revolt in India, the Franco-German War, the Russo-Turkish War, the Italo-Abyssinian War, the Greco-Turkish War, the Spanish-American War, the Russo-Japanese War, and the Moroccan War, all of which shattered the great hopes that Congresses and Anti-War Leagues had fostered. The peaceful demonstrations initiated by the Russian sovereign did not prevent the great powers from increasing their armaments tenfold. And yet, security has considerably increased. There are hardly any people left who seek to increase their resources through war. On the contrary, victorious nations, as well as the conquered, see their debt burdens increase. In former times, war was profitable to those who undertook it if they were victorious, as they conquered provinces or kingdoms that permanently increased the benefits of war, as witnessed in the conquest of England by the Normans. But [iv] this situation has changed; no war profits those who undertake it, even if they are victorious: the benefits they derive from it are less than what they would gain by exchanging their products with those of a so-called enemy country. Thus, Germany has spent a sum greater than the five billion it had gained from its conflict with France: the armaments it was driven to acquire due to the fear of revenge far exceeded the profits of annexing a province and the payment of a war indemnity. Let us not forget that the benefits were reaped by a small class of the population, whereas the tax burden increased for the rest.

However, for nearly half a century, military interests have always seemed to take on an increasingly dominant role. This contradiction arises because, across nations, governments and the class on which they primarily rely are or believe themselves to be interested in a state of war. It is evident that the status of the influential classes has not been diminished by war: even in America, the Civil War, which had ruined the defeated states, led to a resurgence of [v] protectionism in the victorious northern states and eastern industries, culminating in the trust system and the rise of billionaires. In Germany, the military class saw its power increase with the expansion of war and naval budgets, and industrialists raised their profits through protective tariffs, but the masses saw their food prices soar and debts accumulate, which they must ultimately bear through ever-growing taxes. Thus, the ruling classes have an interest in maintaining control over the governed masses, [23] who provide most of the military or civil revenues on which they live.

If, contrary to what was hoped at the beginning of my career, in these early years of the 20th century we observe an increase in belligerent sentiments among the upper classes, we must also note that, during this same period, protectionism has extended throughout the civilized world, with the exception of England, which has so far remained a free-trade state. However, I remain a firm supporter of peace and liberty. What makes me believe in their ultimate triumph is that various advances have multiplied exchanges and thus lowered the cost of living, whereas war has the effect of making it more expensive. There is, therefore, between [vi] war and peace a fundamental difference. One cannot say that war operates free of charge, even if it is victorious, whereas trade always increases the profits of both parties. What reinforces my hopes is that over the past century, the face of the world has changed: innumerable inventions, which have fostered and multiplied wealth, have added to the enjoyment of existence. War prevents wealth from increasing; it raises production costs, whereas inventions generally aim to reduce them. However, inventions have not only served to improve life; on the contrary, they have also perfected the art of war: rifles and cannons have increased their destructive range, new destructive devices have been added to the old ones—torpedoes, submarines, dirigibles, and even airplanes, dynamite, and other explosives. Finally, every day brings improvements in the art of annihilating one's fellow beings and the fruits of their labor, so that the inventions aimed at destruction may well surpass those that contribute to improving humanity's condition; thus, unless people quickly come to their senses, they will be forced to bear the ever-growing costs of war and its preparations. But how long can they sustain this?

[vii]

For a fairly long period after the end of the wars of the First Empire, the world enjoyed peace. There was then some reason to believe that war would cease to ravage the world. Peace Congresses began to multiply. Free trade also found ardent proponents. In England, the reforms of Mr. Huskisson foreshadowed the disappearance of protectionism; those associated with Richard Cobden and Robert Peel announced its imminent end. One could entertain the hope that civilization would have peace and liberty as its allies and that from that era onward, the hostility of peoples would cease. Revolutions and wars soon disrupted peace and saw the return of protectionism. Customs tariffs have continued to separate nations, and there is even reason to fear the increase and expansion of the protective system.

***

However, for more than half a century, a true flourishing has begun to change the face of the world. During my long existence, I have witnessed the birth of railways, whose network now reaches a million kilometers. [viii] Steamships now cross the oceans. Electricity transmits thoughts across the entire world. Photography has become an aid to communication. In my childhood, people wrote only with quill pens; neither metal pens nor postage stamps were known, nor even spark plugs—gas lighting had barely been invented. Thousands of inventions now make life easier. Even intellectual achievements were then fewer and had only just begun to spread among the masses. The mental state of minds today is hardly comparable to what it was on the eve of the 19th century. But the moral state of humanity remains inferior to its intelligence. Hence, the great crisis in which developing societies now struggle. One might almost compare them to those who, through the luck of a lottery, suddenly acquire a fortune of a million and see their material existence transformed overnight without any change to their intellectual state: most of these winners think only of improving their material well-being, if not indulging in the worst excesses, but their morality remains the same, if it does not deteriorate further. This is why one could almost say that the progress of civilization has slowed rather than accelerated, for it depends on both intelligence and morality.

[ix]

***

At about the same time as this flourishing of inventions, socialism emerged. It has become a universal tendency to overthrow governments in order to replace them with an egalitarian system. Socialism encounters absolute resistance only from the classes whose livelihood it disrupts. So far, it has not discovered a system capable of replacing the old regime under which humanity has lived, no matter how varied its forms have been. It has sparked revolutions and civil wars and, in all likelihood, will continue to do so.

But what is the system advocated by socialism? Born from the accumulated suffering that people have endured at the hands of their rulers, they see the remedy in the ownership of themselves. [24] Consequently, they strive to expel their rulers and replace them with a government of their own making: thus was born the parliamentary or constitutional government. And in their ignorance of the natural laws by which Providence governs men—limiting itself to prescribing their observance—they have enacted multiple laws, more often harmful [x] than beneficial to those they intended to protect. This is why socialism, in all its systems, even assuming it succeeds in establishing them, would lead to the ruin of societies. And heads of state, whether monarchists or republicans, whatever motives drive them, are wrong to yield to it, even if they are guided by the purest and noblest sentiments, such as philanthropy.

Unbeknownst to many, the parliamentary and constitutional system leads inevitably to socialism because socialism is nothing other than the appropriation of all means of acquiring wealth, including the governance of society itself. The constitutional and parliamentary system has remained in the hands of the upper classes, who have enriched themselves and now own the majority of the means of production. [25] This is why they are called the capitalist class and are more than ever the object of envious scrutiny. But socialism seeks to seize existing wealth. The struggle between socialism and capitalism is therefore eternal. However, it is well known that as soon as socialists become capitalists, they change their opinions and in turn become defenders of capital. They yield as little as possible to socialism, and thus, as has been said with some modification ofthe expression, [xi] a Jacobin minister is not necessarily the (head of) a Jacobin ministry.

The administration of the State is the object of the parliamentary system, around which almost all former rulers of States have gathered, given the material benefits they derive from it.

The Revolution merely changed the outward appearance of the regime which had been dominant before then. Monarchs were previously regarded as the owners of their people; the Revolution nominally altered this state of affairs: the people, now proclaimed owners of themselves, are henceforth responsible for their governing themselves. They first drafted a constitution setting forth their rights and duties. But they are incapable of leading themselves, and in reality, this system remains nothing more than the domination of one class over the multitude. This domination by a small governing class provokes opposition from the masses excluded from government. Thus, although there is only one class which exercises power and one opposition, since there is an electoral mass which is almost unlimited in size, we have seen the multiplication of political parties greedy to govern. However, whether under monarchy or republic, one can observe the ever-increasing cost of government because the bureaucratic class that depends on it has expanded prodigiously. A low-cost government [xii] seems more than ever to be a utopian illusion, since the constitutional system further increases the expenses of warlike and protectionist governments, often deferring the burden onto future generations by leaving them responsible for its debts and loans.

It is commonly believed that this system is the most perfect possible, yet numerous signs of decline can be observed even among the most advanced civilizations. We believe that it will be improved, just as the steam engine and the power loom have been. And already, one can foresee what these improvements will be by observing the transformations undergone by financial and industrial enterprises. But while improvement of the constitutional system is possible, it may also be delayed due to the vast number of incapable individuals who fulfill electoral duties. We are not speaking here of extending the right to vote to women, which we do not wish for, although we are far from being antifeminist, simply because the more voters there are, the worse the results will be. And even now, they are hardly satisfactory. If one closely examines the actions and decisions of the people's representatives, their inconsistency is evident everywhere: in Spain, some consented to [xiii] the execution of Ferrer on the pretext that he taught a moral philosophy contrary to that of the government, which itself has none, while others, under the pretext of liberalism, broke with the Pope over religious associations that suited certain parties but not all. In France, they confiscated property and decreed the banishment of religious men and women who taught doctrines that displeased them; to carry out this work, they granted themselves fifteen thousand francs per year per person! In Belgium, we witnessed a so-called liberal inquiry directed against poor women who had their children educated by religious orders, the result of which was to bring the clerical party to power, where it has remained for twenty-six years despite the resentment of some voters dissatisfied with its monopoly over government positions and favors for its own followers at the expense of industry and commerce, which bear the cost. In Germany, the people's representatives act as humble servants of the government, which oppresses the former subjects of Denmark and the Poles, who are forced into military service and subjected to taxes they should not owe. In Russia, the Duma approved the transfer of the costs and debts of the war with Japan to the people and, in addition, ratified the despotism inflicted on the Jews, [xiv] the Poles, and the Irish. In America, the people's representatives sanctioned the confiscation of the interests of the defeated Southern states to the benefit of the protectionist industrialists of the North and East, who took advantage of the situation to monopolize protected industries, leading to the rise of trusts and billionaires, and replacing slavery with contempt and the lynching of Black people. Their politicians are so widely discredited that honest people refuse to associate with them … and the unfortunate reality is that in many other countries, political figures are beginning to follow this same path. In Italy, they have increased the tax burden to such an extent that emigration has grown at an alarming rate. In England, fistfights have broken out in Parliament, just as in Austria-Hungary, where anti-semites give free rein to their fury and different nationalities dispute among themselves for preeminence in directing the affairs of the Empire—only finding some unity when it comes to seizing the property of others, as in the annexation of Bosnia-Herzegovina, for example. In Turkey, one also sees a small clique, a kind of ruling committee, striving to impose the interests of "Turkism" rather than governing fairly for all the populations that make up the country. Such are [xv] some of the actions and decisions of the people's representatives under the so-called constitutional system.

Yet, one can conceive of a system superior to the constitutional regime. And this system, modeled on the natural constitution of industry, will be greatly simplified. Already, transportation companies, financial institutions, and industrial and commercial enterprises have a board of directors whose operations are overseen by delegates of the shareholders and also by the shareholders themselves, who meet once or twice a year to examine business matters, make necessary decisions, and approve financial reports. Their participation in the assembly is proportional to the number of shares they own. A portion of the board is appointed by the founder of the enterprise, while the confirmation of other appointments is reserved for the shareholders after a proposal by the president and the board. The members of these boards are generally re-eligible and remain in office for life. In this respect, they differ little from the ministers of the old monarchical regime, such as Colbert, whereas those in the constitutional system have become excessively unstable, their tenure depending on the shifting state of parliamentary factions. In private enterprises, assemblies appoint a [xvi] president who serves as the primary director of operations and receives a higher salary than the other board members, though not excessive. These salaries are counted in the thousands of francs, whereas those of constitutional monarchs, heirs of the old regime, are counted in the millions. Such is the political progress we foresee, which will be followed by all others.

One might object that most parliamentary assemblies work actively and pass laws to which all the peoples of a monarchy or republic are subject, even though they are merely the work of one segment of parliament. But among the laws enacted, scarcely one in a hundred is useful, and the decrees of a board of directors would be far more effective, though they arise from the same source—that is, the majority of the shareholders, or in political terms, universal suffrage. The advent of socialism has significantly increased the number of laws, for socialists do not understand natural laws consist of; they are convinced that the ones they create are superior and demand their strict application. To this end, their ministers multiply the number of functionaries. But nearly all laws inspired by socialism are made for a specific class [xvii] of people to whom they seem beneficial, even though they are actually harmful. For anything that alters the distribution of wealth among taxpayers is far from always favorable to public prosperity. By diverting resources from the wealthier classes into the hands of those who are less capable or more wasteful, and by increasing military expenditures, protectionism, and rule by government bureaucrats, [26] wealth will diminish and debts will grow until the nation can no longer bear the burden. Perhaps it is in this way that, despite the progressive development of civilization, the most prosperous states will ultimately collapse. This is how the Roman world perished—even though it was far more civilized than the swarms of barbarians surrounding it. Internal vices and excessive expenditures will crush modern civilization just as the barbarians crushed it in antiquity. This will be a new form of destruction, no less certain and just as complete as the previous one.

Endnotes to Ultima Verba