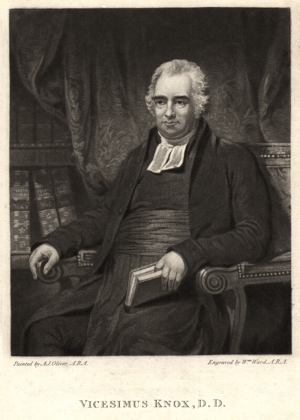

Vicesimus Knox (1752-1821): the Friend of Peace and the Foe of Despotism

|

|

Bibliography

The Works of Vicesimus Knox, D.D. with a Biographical Preface. In Seven Volumes (London: J. Mawman, 1824). Vol. 5 [PDF] and Vol. 6 [PDF].

- “The Spirit of Despotism” (1795),

- pirated 1st edition 1795: London [PDF]; Philadelphia (Lang and Ustick, “for selves”) [PDF]

- 2nd edition 1821: London, Printed for William Hone [PDF}

- 9th edition 1822: London, Printed for William Hone [PDF]

- 1824 edition: Works vol. 5, pp. 137-403. [HTML] and [PDF]

- 11th edition 1837: London, William Bennett [PDF]

- Antipolemus; or, the Plea of Reason, Religion, and Humanity, Against War. A Fragment; translated from the Latin of Erasmus (1795), Works vol. 5, pp. 405-97. [HTML] and [PDF]

- Preface by the Translator, p. 407-30

- Antipolemus, p. 431-97.

- "The Prospect of Perpetual and Universal Peace" (August 18 1793), Works vol. 6, pp. 351-70. [HTML] and [PDF]

Introduction

There was much vehement debate in England about launching a war against France and its Revolution. On the conservative side there was Edmund Burke, a leading conservative Whig MP who argued that war was necessary to destroy the liberal and republican ideals of the French Revolution. Conservative regimes which were based on landed aristocracies were not safe so long as a revolutionary democratic government existed in France. Thus, Burke urged a virtual "war of extermination" to eliminate the revolutionary French government for good, even before the Revolution turned sour under the dictatorship of the Jacobins. In his writings Burke used the metaphor of a disease to describe French revolutionary ideals of democracy and equality. He describe these revolutionary ideas as a "bacillus", a cancer, and a canker. He strenuously opposed signing any peace treaty with France because this would still leave the régime in power, the threat posed by it would not be removed, and any period of peace would allow time for it to regain its strength. His major anti-revolutionary writings of the 1790s were:

- Reflections on the Revolution in France (1790)

- A Letter to a Member of the French National Assembly (1791) and

- Letters on a Regicide Peace (1796-97)

The opponents of Burke's war policy were called the "friends of peace" and were typically liberals, democrats, and and anti-aristocratic radicals who were sympathetic to the American and French Revolutions. They favoured peace in general and attacked the right of the British government to interfere in the affairs of another nation, especially in an attempt to overturn a democratic or liberal revolution like the one currently underway in France and other parts of Europe. One of the more outspoken and articulate members of the peace faction in Britain was the radical minister Vicesimus Knox ("vicesimus" was Latin for "twenty"), who gave stirring sermons on peace and the evils of war, and wrote pamphlets attacking war and its hand-maiden "despotism" which he believed was being established by the anti-French conservative government in England. The "Peace Party" was very outspoken and demanded support for the principles of the French Revolution and the right of nations to determine their own political system. Some of the better known friends of peace and the principles of the French Revolution were Thomas Paine, The Rights of Man (1791-2); James Mackintosh,Vindiciae Gallicae (1791); and William Godwin, Political Justice (1793). Extracts of their writings can be found in Butler's collection Burke, Paine, Godwin and the Revolution Controversy.

Vicesimus Knox was the son of a minister and secondary school teacher. He studied at St John's College, Oxford, graduated in 1775, and then became a fellow of his college 1775-79. He studied English literature and composition, and became well-known known for his erudite and well-crafted essays, which were collected in volumes like Essays, Moral and Literary (1779), Elegant Extracts, or Useful and Entertaining Passages in Prose (1783), Winter Evenings, or Lucubrations on Life and Letters (1788), and his sermons which were published and circulated. Vicesimus succeeded his father as headmaster at Tunbridge School, and resigned in 1812 to retire to London. He was ordained as a priest in about 1777 and was an impressive preacher, scholar and prolific writer. In politics he was a staunch Whig in general but but supported Roman Catholic emancipation and opposed the war against French Revolution.

As the drive towards war intensified Knox gave a sermon at the parish church in Brighton, 18 August, 1793 on the unlawfulness of an offensive war against France, which was published as "The Prospect of Perpetual and Universal Peace" i(see vol. 6 of Works, pp. 351-70). This triggered a violent reaction to his peace sermon by some indignant local militia officers which drove him and his wife and young children out of the Brighton theatre a few days later (were he was probably giving an anti-war speech). Knox's response to this intimidation of the militia officers was to publish his sermon. (DNB, p. 335 and "Biographical Preface" Works. p. vi.).

Knox's pacifism had been influenced by the writings of Desiderius Erasmus (1469-1536) which he translated and published as part of his campaign for peace. He translated and introduced Erasmus' Complaint of Peace (1517) as "Antipolemus, or the Plea of Reason, Religion, and Humanity against War: a Fragment translated from Erasmus and addressed to Aggressors" (1st ed. 1794, republished Works, vol. 5.

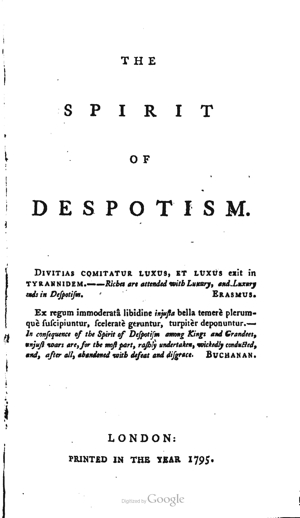

His long pamphlet Spirit of Despotism was written in late 1794 or early 1795 in order to oppose the British attempt to destroy the French Revolution by force by organising and subsidising a coalition of conservative monarchical powers. Knox supported the liberal ideals of the revolution and believed that this revolution was in the best interests of mankind. He also argued that England's policy would also spread a "spirit of despotism" within England (encouraged by the writings of Edmund Burke) which its heavy-handed response to critics of the war like him and the other Friends of Peace had clearly demonstrated.

However, later in 1795 Knox tried to suppress the publication of his pamphlet Spirit of Despotism because he believed that France now had become the aggressor, with its policy of territorial expansion, by destroying the independence of its neighbouring countries, and restricting the liberty of its own citizens within France. He wanted to postpone its publication until France had stopped its aggression. Thus, there was no authorised publication in his lifetime, only a pirate edition which was printed in London in 1795 and one also in the new United States (Philadelphia).

The Brighton Sermon on "The Prospect of Perpetual and Universal Peace" August 18 1793

His sermon against offensive war (i.e. the war against France) was based on Luke, ii, 14 "Glory to God in the highest, on earth peace, good will towards men." Knox regards this as the "motto of Christianity" (Works, vol. vi, p. 351). Far from there being peace on earth and the freedom and prosperity which peace brings ("liberty, commerce, agriculture, these are the beautiful daughters of peace" vi, p. 367) there was now the spectre of an intensifised war which would be based upon the antagonism of rival ideologies, namely conservative monarchism vs. democracy and liberalism. Knox described war in following manner:

Peace on earth! Alas where is it? amid all our refinement in the modes of cultivated life, all our elegant pleasures, all our boasted humanity, WAR, that giant fiend, is stalking over empires in garments dripping with the blood of men, shed by men, personally unoffended and unoffending...(Works, vi, pp. 352-3)

Knox distinguished between an unjust offensive war and a justified defensive war. Offensive war, like the one Britain was engaged in against France was described as:

By all but the vulgar and the creatures of despostism, offensive war, with all its pompous exterior, must be deprecated as the disgrace and calamity of human nature. (vi, p. 353)

Knox called for the Christian religion to prevail and "the sword of offensive war must be sheathed for ever" (vi, p. 367).

A defensive war on other hand was sometimes necessary to protect life, liberty and property. But British life, liberty and property he thought were not under threat by French Revolution.

Defensive war, in the present disordered state of human affairs, is sometimes as necessary as it is honourable; necessary to maintain peace, and the beautiful gradations of a well regulated society. (vi, p. 358).

Knox attacks also the myth of the glory of war, especially the allure of splendid uniforms and the pageantry of the army, by contrasting the "outside pageantry" with the brutal reality of war.

The shades of the picture are black as death, the colouring of blood... Poor outside pageantry! What avails the childish or womanish finery of gaudy feathers on the heads of warriors? Though tinged with the gayest colours by the dyer's art, they appear to the eye of humanity, weeping over the fields of battle, dipt in gore. What avail the tinsel, the trappings, the gold and the scarlet? Ornaments fitter for the pavilions of pleasure than the field of carnage. Can they assuage the anguish of a wound, or call back the departed breath of the pale victims of war; poor victims, unnoticed and unpitied, far from their respective countries, on the plains of neighbouring provinces, the wretched seat of actual war; not of parade, the mere play of soldiers, the pastime of the idle spectator, a summer day's sight for the gazing saunterer; but on the scene of carnage, (the Aceldama, the field of blood, where, in the fury of the conflict, man appears to forget his nature and exhibits feats at which angels weep, while nations shout in barbarous triumph. (Works, vi, pp. 353-4).

He blames politicians for sacrificing the interests of the people for their own ambition and to protect their privileges. Propaganda, or "the politician's artiface", is used to hide the true brutality of war (vi, p. 355) and to make the people consider their neighbours to be their enemies. Politicians and their paid propagandists (like Burke) "seem to claim an hereditary right to wisdom" (p. 357") which he thought was unjustified. War was used by politicians and the state to oppress the people and transfer resources into their hands. Erasmus had a very similar view of war as being parasitic on the productive people of the nation.

(War) Decked, like the harlot, in finery not thine own, thou art even the pest of human nature; and in countries where arbitrary power prevails, the last sad refuge of selfish cruel despotism, building its gorgeous palaces on the ruins of those who support its grandeur by their personal labour; and whom it ought to protect and nourish under the olive shade of peace. (vi, p. 355).

Religion and philosophy, he thought, should be voices of peace which had to heard above "the cannon's roar, the shouts of victory, and the clamours of discordant politicians" (vi, p. 358). Yet, like Erasmus, Knox condemns the church for being militaristic, hypocritical and a bad example to people. The Church had become "one of the most massy columns of the state" (vi, p. 359) but its moral authority had been undermined by the war-mongering and "irreligious example" of the clergy. The Church had become a "state engine" designed to support the privileges of a fortunate few. One result of the French Revolution which Knox supported was to end the political power of Church in France.

It (religion) was not designed by its holy Author as a state engine, in any country in the universe, to support the power of a fortunate few, who may be born to titles and estates; who bask in the sunshine of courts, or who lord it over their fellow men in despotical empires, by a power usurped in days of darkness, or acquired by chance and conquest, and preserved by interest, prejudice, or the violence of arbitrary authority. (vi, p. 364).

Knox advocated that nations should settle disputes by arbitration and negotiation rather than war (vi, p. 363) and recognize the universal brotherhood (or "fraternity" as the French revolutionaries out it) and natural rights of mankind. The great contrast he thought was between those who advocated reason and those who advocated force.

Let us all, in our several stations, promote peace on earth, if it be possible; not only by seeking as we have power, to compose the differences of nations by negotiations, but by subduing our own pride and ambition, by learning to consider all men under the sun, as united to us by brotherly love, or, as it is termed, fraternity; natural, not political fraternity; the strong tie of one common nature. Let us appeal to reason in all national disputes; to reason, the constituent essence of man, and not only to the sad resource of creatures without reason, brute force and violence. (vi, p. 363).

He urged the mercenaries who were employed to fight in these wars to "preserve" their religion and not treat their opponents like animals to butcher and pillage. He called for each individual to live as true Christians so that the scourge of war would no longer be necessary. All Christian kings, princes, rulers, nobles, councillors, and legislators must combine to form a "league of philanthropy" (vi, p. 369) to enforce "by reason and mild persuasion" the Christian law of love among all mankind. He called for rulers to curb their pride and ambition and instead protect the property of their citizens from high taxes and destruction caused by wars. Knox concluded his sermon by saying:

O thou God of mercy, grant that the sword may return to its scabbard for ever; that the religion of Jesus Christ may be duly understood, and its benign influence powerfully felt by all kings, princes, rulers, nobles, councellors, and legislators, on the whole earth; that they may all combine in a league of philanthropy, to enforce by reason and mild persuasion, the law of love, or Christian charity, among all mankind, in all climes, and in all sects; consulting, like superior beings, the good of those beneath them; not endeavouring to promote their own power and aggrandizement by force and arms; but building their thrones, and establishing their dominion on the hearts of their respective people, preserved from the horrors of war by their prudence and clemency: and enjoying, exempt from all unecessary burthens, the fruits of their own industry; every nation thus blest, permitting all others under the canopy of heaven to enjoy the same blessings uninterrupted, in equal peace and security. (vi, p. 369).

The Spirit of Despotism (1795)

The following year (1794) Knox produced a long work attacking both aristocratic privilege and war. Knox argued that the principles of the French Revolution were those of liberty and the protection of individual from arbitrary government. Aristocratic forces in England realised this threat and sought to defend their privileges at home and crush French liberties across channel by stifling dissent, preventing political reform, and waging war. He sharply challenged Burke's interpretation of the French Revolution and his hostlity towards democracy. Knox admitted that the Paris mob had committed some atrocities but believed that "the transient outrages of a Parisian tumult" were far outweighed by "the perpetual despotism of the old French government." (v, p. 196). One of the key ideas he put forward in this pamphlet was the inevitable link between a foreign war and the "spirit of despotism" at home, which he stated in the preface.

The heart is deceitful above all things; who can know it? As far as I know my own, it feels an anxious desire to serve my fellow-creatures, during the short period of my continuance among them, by stopping the effusion of human blood, by diminishing or softening the miseries which man creates for himself, by promoting peace, and by endeavouring to secure and extend civil liberty.

I attribute war, and most of the artificial evils of life, to the Spirit of Despotism, a rank poisonous weed, which grows and flourishes even in the soil of liberty, when over-run with corruption. (v, p. 139)

Know regarded the prevalence of Bu'rkes views on the French Revolution, especially among the upper classes, as a veritable "war on French liberty" (v, p. 326) by the British government which rightly feared that ideas on equality and liberty would soon spread to the English lower classes. Thus a war like the one against France served a double purpose: to attack the source of this opposing ideology and distract the citizens from domestic reform. War thus "greatly helps the cause of despotism."

In times of peace the people are apt to be impertinently clamorous for reform. But in war, they must say no more on the subject, because of the public danger. It would be ill-timed. Freedom of speech also must be checked. A thousand little restraints on liberty are admitted, without a murmur, in a time of war, that would not be borne one moment during the halcyon days of peace. Peace, in short, is productive of plenty, and plenty makes the people saucy. (v, p. 329).

War also serves to bolster the power and privileges of the military professionals. Knox called it the aggrandizement of "those who build the fabric of their grandeur on the ruins of human happiness." (v, p. 331). This led to Knox reaching heights of polemical rhetoric with echoes of Erasmus who expressed similar thoughts:

Language has found no name sufficiently expressive of the diabolical villany of wretches in high life, who, without personal provocation, in the mere wantoness of power, and for the sake of increasing what they already possess in too great abundance, rush into murder! Murder of the innocent! Murder of myriads! Murder of the stranger! neither knowing or caring how many of their fellow-creatures, with rights to life and happiness equal to their own, are urged by poverty to shed their last drops of blood in a foreign land, far from the endearments of kindred, to gratify the pride of a few at home, whose despotic spirit insults the wretchedness it first created. There is no greater proof of human folly and weakness than that a whole people should suffer a few worthless grandees, who evidently despise and hate them, to make the world one vast slaughter-house, that the grandees may have more room to take their insolent pastime in unmolested ease. (v, pp. 330-1)

In addition, despotic governments like to diffuse "military taste" throughout society, "to gothicize a nation", especially the lower classes, in order to create the habit of unquestioning obedience which makes it easier for a despotic government to govern.

The strict discipline which is found necessary to render an army a machine in the hands of its directors, requiring, under the severest penalties, the most implicit submission to absolute command, has a direct tendancy to familiarize the mind to civil despotism. Men, rational, thinking animals, equal to their commanders by nature, and often superior, are bound to obey the impulse of a constituted authority, and to perform their functions as mechanically as the trigger which the pull to discharge their muskets. They cannot indeed help having a will of their own; but they must suppress it, or die. They must consider their official superiors as superiors in wisdom and in virtue, even though they know them to be weak and viscious. They must see, if they see at all, with the eyes of others; their duty is not to have an opinion of their own, but to follow blindly the behest of him who has had the interest enough to obtain the appointment of a leader. They become living automatons, and self-acting tools of despotism. (v, p. 250).

Knox also attacked the Machiavellianism of the court and cabinet where morality is forsaken for the spoils of office.

There (in the court and cabinet) Machiavelian ethics prevail; and all that has been previously inculcated appears like the tales of the nursery, calculated to amuse babes, and lull them in the lap of folly. The grand object of councellors is to support and increase the power that appoints to splendid and profitable offices, with little regard to the improvement of human affairs, the alleviation of the evils of life, and the melioration of human nature. The restraints of moral honesty, or the scruples of religion, must seldom operate on public measures so as to impede the accomplishment of this primary and momentous purpose. A little varnish is indeed used, to hide the deformity of Machiavelism; but it is so very thin, and so easily distinguished from the native colour, that it contributes, among thinking men, to increase the detestation which it is intended to extenuate. (v, p. 338-9)

Knox concluded that, far from being Machiavellian, a good government should avoid wars and the high taxes that wars require. Good government would preserve the peace and "diffuse plenty" by not taxing necessary items of consumption.

The principle objects of all rational government, such as is intended to promote human happiness, are two; to preserve peace and diffuse plenty. Such government will seldom tax the necessaries of life. It will avoid wars; and, by such humane and wise policy, render taxes on necessaries totally superfluous. Taxes on necessaries are usually caused by war. (v, p. 399).

However, when the Jacobins under Robespierre came to power and waged a ruthless war against their monarchist and conservative opponents, this turned the war by France into a war of aggression and so Knox could no longer support them. He thus attempted to suppress the distribution of his pamphlet on Despotism. A handful of copies had been circulated among friends and inevitably a pirate edition was published, first in London and then in the United States. It would not be until after his death in 1821 that a second edition would appear, promoted by the Radical and democrat William Hone. A 9th edition would be published in 1822 and an 11th in 1837, such was the demand for Knox's tract.