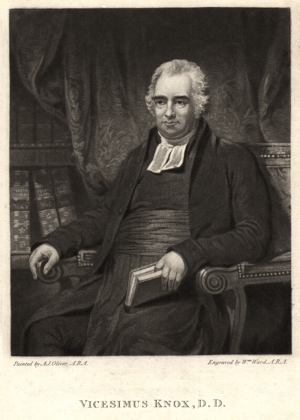

Vicesimus Knox, "The Prospect of Perpetual and Universal Peace" (1793)

|

|

Note: This is part of a collection of works by Vicesimus Knox.

Source

The Works of Vicesimus Knox, D.D. with a Biographical Preface. In Seven Volumes (London: J. Mawman, 1824). Vol. 6, pp. 351-70.

SERMON XXV. The Prospect of Perpetual and Universal Peace to be established on the Principles of Christian Philanthropy (Preached at Brighton, Aug. 18, 1793)

St. Luke, ii. 14,—Glory to God in the highest, on earth peace, good will towards men.

This gracious proclamation from Heaven announces the great purpose of Jesus Christ, the promotion of piety to God and benevolence to man. It may indeed be called the motto of Christianity. It may form the inscription on its unstained banners, as it advances in its progress, endeavouring to diffuse the blessings of perpetual peace and universal love.

At a time when atheism has been imputed to a great and polished nation, and many in the highest ranks in our own country, whose examples are seducing among the vulgar, from the false glitter of birth and fortune, seem to plume themselves on the neglect of public worship, as a mark of superior sense, or of peculiar gaiety of heart; the neglect of that public worship, which they allow to be necessary to their inferiors, which they see recommended by royal example, enforced by royal proclamations, and required by law; at a time, when a specious philosophy, under the pretence of removing early prejudices in favour of Christianity, is gradually sapping the foundation of that ancient and venerable fabric; at such a time, so unfavourable to the prevalence of that religion, in which our pious fathers lived and died in peace, under the benign influence of which our country has flourished in unexampled prosperity, and by which human nature has been elevated to all [352] attainable perfection; at such a time, an invitation to give glory to God, or to Christianity, enforced with seriousness and ardour, will at least have the merit of being seasonable.

Our Saviour's own words of invitation are indeed sweetly persuasive, if the world would hear them, amidst the cares of avarice, the struggles of ambition, and the clangor of arms. Come unto me, says he, all ye that labour and are heavy laden and I will give you rest.

Who among us is not concerned in this address, which of us is not labouring with some evil or laden with some sin, some infirmity, some habitual passion or some sore disease?

In what part of Christendom is that Christianity which we all profess, suffered to have its full effect, either on the national character and conduct, or on the regulation of private life?

Give me leave to bring before you, for a few moments, the great picture of the living world, as it is now exhibited, in the most polished part of it, Europe, enlightened as it is by science and professing Christianity. Let us consider whether among those who bear rule, by power or by example, glory is duly given to god; whether they do really promote to the utmost of their power, peace on earth; and whether they seem to entertain good will towards men, in that extent and degree which the Gospel of Jesus Christ requires of all who profess to believe it, and who expect the rewards of the pious and the peaceful.

The picture is sadly shaded with misery. Peace on earth∗ Alas where is it? amid all our refinement in the modes of cultivated life, all our elegant pleasures, all our boasted humanity, war, that giant fiend, is stalking over empires in garments dropping [353] with the blood of men, shed by men, personally unoffended and unoffending; of men, professing to love as brethren, yet cutting off each other from the land of the living, long before the little time allotted them by nature is elapsed; and increasing beyond measure, all the evils to which man is naturally and morally doomed, at the command of a narrow shortsighted human policy, and an ambition which, considering the calamities it causes, I must call accursed.

The shades of the picture are black as death, the colouring of blood. No; not all the arts of politicians can veil its shocking deformity, from any eyes but those of the vulgar;* the vulgar, I mean, rich as well as poor, titled as well as untitled, swaying sceptres or wielding a spade. By all but the vulgar and the creatures of despotism, offensive war, with all its pompous exterior, must be deprecated as the disgrace and calamity of human nature. Poor outside pageantry∗ What avails the childish or womanish finery of gaudy feathers on the heads of warriors? Though tinged with the gayest colours by the dyer's art, they appear to the eye of humanity, weeping over the fields of battle, dipt in gore. What avail the tinsel, the trappings, the gold and the scarlet? Ornaments fitter for the pavilions of pleasure than the field of carnage. Can they assuage the anguish of a wound, or call back the departed breath of the pale victims of war; poor victims, unnoticed and unpitied, far from their respective countries, on the plains of neighbouring provinces, the wretched seat of actual war; not of parade, the mere play of soldiers, the pastime of the idle spectator, a summer day's sight for the gazing saunterer; [354] but on the scene of carnage, the Aceldama, the field of blood, where, in the fury of the conflict, man appears to forget his nature and exhibits feats at which angels weep, while nations shout in barbarous triumph.

The elegant decorations of a sword, wantonly drawn in offensive war, what are they, but a mockery of the misery it was intended to create? An instrument of death to a fellow-creature who has never injured me, a holiday ornament∗ Colours of the darkest hue might form the appropriate habiliments of those who are causelessly sent as the messengers of death; of death, not to animals of another species, fierce and venomous; but to those who like themselves, were born of woman, who sucked the breast of a woman, and who, if spared by the ruthless sword, must like themselves in a few short years die by the necessity of nature; die, and moulder into dust, under the turf once verdant and flowery, but now crimsoned with human gore. Alike born the victors and the vanquished, alike they die if spared in the battle; and alike must stand at the latter day, all stript of the distinctions of finer dress and superior rank, in the presence of those whom they cut off in this world before their time, in youth and health, like rose-buds cropt in the bud of existence.

Cease, oh∗ cease, while such scenes are passing in the field of actual slaughter, cease, for humanity's sake, the din of martial music. It is surely a mockery of wretchedness∗ Poor artifice∗ to drown the voice of anguish calling for help, and calling in vain; the yells of the dying, the groans of those who lie agonizing without any hand to pour balsam into their wounds: cruel contrivance to stifle by noise the bitter lamentations, the last sad privilege of the [355] mourners, who bereaved of their friend, their parent, or their child, are bereaved indeed∗*

Oh war∗ thy blood-stained visage cannot be disguised by the politician's artifice. Thy brilliant vestments are to him who sympathizes with human woe in all climes and conditions, no better than sable mourning; thy melody, doleful discord, the voice of misery unutterable. Decked, like the harlot, in finery not thine own, thou art even the pest of human nature; and in countries where arbitrary power prevails, the last sad refuge of selfish cruel despotism, building its gorgeous palaces on the ruins of those who support its grandeur by their personal labour; and whom it ought to protect and to nourish under the olive shade of peace.

What feeling man can cast his eyes (as he proceeds in contemplating the picture) over the tented plains, on the theatre of war, glittering in the sunbeams with polished arms and gay with silken banners, without a sigh, if he views it undazzled by the "pride, pomp and circumstance," which the wisdom of this world has, from the earliest times, devised to facilitate its own purposes; purposes, it is to be feared, that have little reference to him who said, that his kingdom was not of this world; and whose religion was announced by a proclamation of peace on earth. What a picture is the tablet we are viewing of the heart of man, and of the misery of man∗ that he should thus find it necessary to defend himself with so much effort, at such expense of blood and treasure, not, as I said before, against the beast of the forest, not against the tiger and the wolf, for then it were well; but against his fellow man, his Christian brother, subject to the same wants, agonized with the same natural sufferings, doomed to the same [356] natural death, and as a Christian, hoping for the same salvation; and perhaps separated from him only by a few leagues of intervening ocean.

All the waters of that ocean cannot wash away the stain thus deeply fixed on the human character.

Lo∗ in countries where war actually rages, thousands and tens of thousands of our fellow-creatures, all perhaps Christians in profession, many in the flower of their youth, torn from the peaceful vale, the innocent occupations of agriculture, or the useful employments of mechanic arts, to learn with indefatigable pains (separated at the same time from all the sweet endearments and duties of domestic life) to learn the art of spreading devastation and most expeditiously and effectually destroying those of their fellow-creatures, whom politicians have bade them consider as enemies, and therefore to cut off in their prime; but whom Christ taught, even if they were personal enemies, to love, to pity, and to save. Do they not, thoughtless as they are, require to be reminded of the gracious proclamation from Heaven, "On earth peace, Good-will towards men."

I wish not to dwell on the gloomy picture exhibited by various nations of Europe, professing Christianity as part of their respective constitutions; but acting towards each other with the ferocity of such savages as never heard that invitation of Christ;. Come unto me, all ye that labour and are heavy laden and I will give you rest. But ere we turn from the melancholy scene, let every man of sensibility drop a tear over it, as Xerxes wept when he beheld his armies, doomed shortly to perish by the law of nature if spared by the sword of violence. Let the man of sensibility reflect, that all the busy actors on this stage, who spend all the time allowed them in this life in a destructive activity, will themselves soon sleep in silence under the [357] turf on winch they now proudly march to mutual slaughter; the spear fallen from their hands, and the gay flag trampled in the mire∗ Fall they must, the conquerors and the conquered, all subdued by those universal victors, age, disease, and death, if peradventure they should escape in the shock of the battle.

Alas∗ is it not enough that age, disease, death, and misery, in a hundred forms, are hourly waging war with all mankind; but they must add to the sting of death new venom; new anguish to every pang by waging war with each other? Men who as individuals are kind and humane, appear as nations, still in a state of barbarism and savage nature.

Yet we must believe and maintain the political necessity of war, though the greatest evil which can be endured by a civilized, flourishing and free people; we must believe its political necessity, because they, who in the various nations of the world, seem to claim an hereditary right to wisdom, as well as power, have, in all ages and in the most enlightened and Christian countries, so determined; yet, with all due submission to that wisdom and to that power, let every man who justly glories in the name and feelings of a man, mourn and lament the existence of that political necessity; and if it be such, pray to the father of us all, of every clime and colour, that under the benign influence of that Christianity which we profess, war may be no more on the face of the whole earth, and the sword every where converted into the pruning hook and the plough share.

But here let me be permitted to say, that no disgraceful imputation whatever can fall on those who are engaged in the profession of war, from these general observations on its calamities; for they have frequently displayed proofs of dispositions [358] singularly noble, generous and humane, as well as brave. Defensive war, in the present disordered state of human affairs, is sometimes as necessary as it is honourable; necessary to maintain peace, and the beautiful gradations of a well regulated society.

We, however, as faithful ministers of the Gospel, are on our part bound by our duty, to pray for peace; to promote peace as much as in us lies; to preach peace, to cry aloud for peace and spare not, even though the instigators to war should frown upon us; and in defiance of the God of peace, prepare for the battle. It is our indispensable duty; and O∗ that the still small voice of religion and philosophy could be heard amidst the cannon's roar, the shouts of victory, and the clamours of discordant politicians∗ It would say to all nations and to all people "Come unto me, all ye that labour in the field of battle, heavy laden with the weapons of war, worn out with its hardships, and in jeopardy every hour; come unto me and I will give you rest; I will be unto you as a helmet, and a shield from the fiery darts of the common enemy of all mankind; and will lead you, after having rendered you happy and safe in this world, to the realms of everlasting peace."

But from the picture of public and national misery, arising in great measure from a thoughtless disregard to Christ and his benevolent laws, let us turn to the contemplation of private life. The great and the fashionable in all countries stand foremost in the picture, and attract the eye by the gay colouring in which they choose to be exhibited.

Do they then principally and in avowed preference to all other objects, give glory to god on high? do they seek to promote peace on earth, or war? do they appear to cherish any peculiar degree of good-will towards men? or, are they attached to [359] themselves, and the preservation of their own power, nominal honours, and pleasures, at all events, though it cost the poor citizen many of his comforts; and the poor soldier his limbs or his life; and the public its security or its opulence?

On a calm review of the picture, many of those also who seem ostentatious of superior happiness, appear to labour and to be heavy laden with a variety of splendid miseries and polished perturbations; and to them also, Christ certainly addresses himself, as well as to the poor and needy, when he says, Come unto me and I will give you rest. He speaks, but they cannot hear, and will not come. The places of worship have no charms or attractions for them. Pleasure, or what fashion chooses to call so, for feeling and nature have little to do in the choice, is their idol; and they worship in her temple glittering with variegated brilliancy, to the midnight hour, with the most servile adoration. After six days toiling in her service, they cannot give up even one hour on the seventh, to the religion of those countries, whose religion they are bound to promote by example; but by their apparent conduct, in this particular, contribute to diffuse that very atheism, which, in reviling their neighbours, they are among the first most loudly to condemn. If, as is granted, the church be one of the most massy columns of the state, they certainly undermine that column by their irreligious example, more effectually, than all the writings of the seditious by their arguments or declamation. The whole business of many of them is to banish reflection; but this, as it is one of the strongest proofs of human misery and the want of internal religious consolation, prevents at the same time all attention to piety and effectual benevolence. Such persons cannot bear to think, even during one hour, [360] on one day in the week, devoted by the laws of God and their country to religious services, even after seven days spent in the indulgence of a silly pride, in useless or mischievous activity, and in imitative folly. Then be assured, that thus destitute of the affections of piety and benevolence, though they study every appearance of happiness, they are neither happy themselves, nor solicitous for the happiness of their fellow-creature. Their ostentatious enjoyments are frivolous; yet prevent reflection on their own or others misery. They labour and are heavy laden with the tædium vitæ, with fulness of enjoyment, with envy, at seeing others rising in youth, beauty and figure, while their sun is setting! They suffer a thousand mortifications, of which vanity is sorely sensible, and which are incompatible with the benign sentiments of piety to God and love to man. They seek rest and find none; for they seek it every where but where it is to be found, in the religion of Jesus Christ. They cannot adopt the religion of the vulgar, though like the vulgar they must die; they cannot come to Jesus Christ, but eagerly repair to the god of this world, who indeed blinds their eyes and hardens their hearts; but will he exempt them from the common lot of humanity? Will he snatch them from death, temporal or eternal? Will he, in the hour of distress, deliver them from disease, from pain, from the pangs of a wounded conscience? Will he enable them to bear themselves, to endure solitude, their own company for a single day? Will he teach them, like religion, to support their own reflections, to put off childhood and childish distinctions, such as a peculiar garment or a singular vehicle, formed to attract notice? Will he teach them to become men, men in understanding as well as form, daring to follow nature, [361] reason, and simplicity of manners, uninfluenced by fashion and affectation? Men in true courage, and men also in feeling, in the softness and sympathetic qualities of man; in a tender regard for the honour and happiness of their fellow men, whom they now appear to despise and hate; and men also in the sense of their own helplessness and their dependence. Dependence, did I say? I must remember that they are men of spirit, not, I fear, of a holy spirit; but of an audacious, haughty, contemptuous spirit; a spirit of useless activity doing no good in society, yet assuming all importance; a spirit aiming at distinction in trifles, doing something to surprise and strike even those very beholders whom they affect to despise, by some singular absurdity in the colour or form of a vestment, or the fashion and trappings of an equipage; a spirit, which displays courage where there is no danger; bravery by oaths and noisy language to helpless inferiors; wit by blasphemy against God; convivial gaiety by drunkenness; self-consequence, by perpetual noise and constant hurry, where there is no business, and neither inclination nor ability for it, if there were; persons, who seem to put their trust in horses and chariots for their happiness, and who drive to glory with the speed of Jehu, too often deserving the fate of Absalom. Are such persons inclined to give glory to God in the highest, above all things? By their habitual absence from places of worship, it might be concluded that they have little more pretensions to piety, than the brutes whom they urge in the career of their mean ambition. Are they busy in promoting peace on earth? No; not if war tends to their own aggrandizement or emolument. Do they seem solicitous to prove their good-will towards men? Wrapt up in selfishness, selfish grandeur, selfish [362] vanity, selfish gratifications, they have no heart for pity; and the hand, that is open for the expenses of pleasure and ostentation, is shut, closed with adamantine grasp, to the unseen, unassuming works of mercy and disinterested love.

Such spirits, though evidently labouring and heavy laden with self-created woes, yet by the fascinating brilliancy of an outside, lead thousands of all ranks and professions in. the train of dissipation. Folly indeed adorns her cap with such finery, and rings her bells so loudly and incessantly, that the flock follows implicitly; too much occupied in listening and gazing, to know whither they are hastening with headlong fury, though the path should finally terminate in temporal or eternal destruction.

Can they give glory to God in the highest, above all other objects, who seem totally engrossed in giving glory to each other and to themselves? "Come unto me," says wisdom, by the mouth of Jesus Christ, but folly deafens the ear, and stifles the gentle voice which bringeth good tidings of peace, eternal peace.

But let us turn from both these pictures; from scenes of blood and carnage, from the horrid din of war, and all its dreadful preparations, which form an amusing sight and pastime for the idle. From the noise of self-assuming impertinence and folly let us turn to the retreats of wisdom, in the philosophic shade, and there listen to the lessons of mercy and love, taught by Jesus Christ, the meek and lowly. Let us elevate our minds to heaven and give glory, not merely to some earthly potentate, for the sake of advantage, for a title, an employment, or a pension; but to the King of kings, the Lord of lords, the Ruler of princes, with hearts filled with gratitude for existence and preservation; felling down with sincere [363] humility before him, and remembering in the midst of all our adventitious honours, that there will be an equality in the grave, and that death, in a few years will level all distinctions. Let pride and pomp think of this, and learn universal philanthropy.

Let us all, in our several stations, promote peace on earth, if it be possible; not only by seeking as we have power, to compose the differences of nations by negotiation, but by subduing our own pride and ambition, by learning to consider all men under the sun, as united to us by brotherly love, or, as it is termed, fraternity; natural, not political fraternity; the strong tie of one common nature. Let us appeal to reason in all national disputes; to reason, the constituent essence of man, and not only to the sad resource of creatures without reason, brute force and violence.

With respect to the third particular in the text, good-will towards men, let us imitate God and our saviour in universal philanthropy. Let us be ashamed of expending time, arid riches, and employing power, merely in selfish gratification. Open your hearts to the love of your fellow-creatures, wherever they exist. Men do not love each other as they ought. If distinguished by a ribbon, or title, or a little brief authority, they often become too proud to own each, other as brothers and children of the same family; yet human blood is all of one colour, and naked came we into the world, and naked shall we depart. The little distinctions of a party, the separation of a rivulet or a wall, is sometimes sufficient to estrange man from man for life; and the intervention of a sea, to bid them point the cannon, arm the floating castle, and fix the encampment against the poor partakers of mortality, who, like themselves, are crawling about and breathing the same vital air, in the [364] little space allotted to their lives, on an opposite shore. How must a superior being pity or deride the puny ants of the same ant-hill, armed with weapons of death, and destroying each other by thousands and tens of thousands, when separated by a straw or a puddle, in a dispute for a grain of wheat or a particle of dust, with space enough around them for all, and in the midst of abundance∗ Religion, both natural and revealed, undoubtedly teaches us that all men are brethren, though the word fraternity misunderstood, be offensive; and all governments in Christendom are, I believe, sufficiently willing to allow the utility of religion to a state, even in promoting civil subordination.

But after all, there can be no rational purpose of any religion, but to make those who profess it happy. It disavows the politics of the worldling. It was not designed by its holy Author as a state engine, in any country in the universe, to support the power of a fortunate few, who may be born to titles and estates; who bask in the sunshine of courts, or who lord it over their fellow men in despotical empires, by a power usurped in days of darkness, or acquired by chance and conquest, and preserved by interest, prejudice, or the violence of arbitrary authority. It was designed for all the sons and daughters of Adam, to console them in their sufferings, to diffuse peace, love, and joy; to soften the horrors of death, and to lead to everlasting life. Such was the proclamation from heaven, announcing the religion of our country, which is as much a part of our excellent constitution as any other in which we glory. Hear it, ye nations, On earth peace, Good-will towards men. It is the law of Christ, and virtually enforced by the law of the land throughout Christendom.

[365]Thus benevolent in its design, and beneficial in its effects, uniformly, at all times and under all circumstances, beneficial, unless counteracted by narrow-minded statesmen; let all men, however otherwise divided, unite to preserve and to perpetuate among them the influence of the Christian religion. Let the princes of the earth, whose examples are so powerful in promoting either virtue or vice, in diffusing either happiness or misery, trust not so much in fleets and armies, for they have failed in all times and countries, as in the living God; who, we are told, in Scripture, can remove the sceptre from one nation to another people; whose omnipotent arm, after all our preparations, can break the spear asunder, and burn the chariots in the fire. May the preservation of a single life, among those committed to their tutelary care, be more desired than the conquest of a province, for the purpose of interest; or the demolition of a city, to serve the cause of despots; of despots, base, ignorant, and inhuman, combined (if ever there should be such a combination) against the happiness of the whole race. Let it be deemed by Christians a greater honour to pluck one sprig of olive, than to bring home whole loads of laurel; to be welcomed by the cordial salute of hearts, delighted with the blessing of peace restored, than by the forced explosion of ten thousand cannons, and the false brilliancy of a venal illumination.

Ye in the lowest ranks of society, wherever ye are dispersed all over the habitable globe; ye, our poor brethren, who are numbered but not named, when ye fall for your respective countries; who, in foreign climes, happily not in our own, are looked down upon with sovereign contempt, and even let out by petty despots, as butchers of your species, in any cause for pay, preserve at least your religion, [366] obey its laws, hope for its comforts; bind it round your hearts, and let neither the artful philosopher, by his false refinements beguile you; nor the haughty oppressor, by keeping you in total ignorance, rob you of this treasure; it is a pearl of great price, lock it up in the casket of your bosom, there to remain through life, inviolate; it is your only riches; but it makes you opulent in the midst of poverty, and happy in the midst of woes, which without it, would be scarcely tolerable.

The examples of the great and fashionable in affairs which concern God and conscience, are not to be followed by you without great caution. Their religious education is too often wretchedly defective. They too often will not submit to early discipline, and who shall enforce it? They are unfortunately surrounded from their youth by a herd of mean sycophants, the panders of their passions, who flatter them, conceal the truth from them, and lead them into every folly, absurdity, and vulgarity, which may please that taste which they have studiously depraved; a taste which levels more than all those misrepresented principles of equality, mistakenly perhaps adopted by foreign politicians, and angrily opposed by others deeply interested in all inequality, knowing that they must sink, if merit only is allowed to rise.

Let not vain philosophy corrupt any of you. Philosophy cannot afford you the comforts of Christianity; and till philosophy can substitute a more comfortable religion, in its place, retain, with resolute attachment, the religion of Jesus Christ, honouring God and loving man; seeking peace, and ensuing it; doing every thing in your power to render life pleasant and happy to all men; for such, after all, is the most rational end of all policy, and all religion, [367] the rest is grimace and hypocrisy, statecraft or priestcraft, tending to despotism or fanaticism.

If the Christian religion, apparently laid aside, when to lay it aside suits the convenience of politicians, were indeed allowed to influence above every thing else the conduct of princes, and the councils of all cabinets, how different would be the picture of Europe.

"Now dissentions, depredations, villainous partitions of peaceful kingdoms, wars and murders, are constantly ravaging this respectable abode of philosophy, this brilliant asylum of arts and sciences. To reflect on the sublimity of our conversation, and the meanness of our conduct; on the humanity of our maxims, and the cruelty of our actions; on the meekness of our religion, and the horror of our persecution, on our policy so wise in theory, and so absurd in practice; On the beneficence of sovereigns, and the misery of their people; on governments so mild, wars so destructive; how can one reconcile it," *—but by supposing that religion and benevolence are chiefly confined to professions; and that they have little real influence on the hearts of nations or their rulers. In a truly Christian country, Peace on earth and Goodwill towards men, must of necessity be the ultimate object of its political wisdom and national effort. What is aggrandizement without tranquillity? Liberty, commerce, agriculture, these are the beautiful daughters of peace.

If the Christian religion in all its purity, and in its full force, were suffered to prevail universally, the sword of offensive war must be sheathed for ever, and the din of arms would at last be silenced in [368] perpetual peace. Glorious idea∗ I might be pardoned, if I indulged the feelings of enthusiastic joy at a prospect so transporting. Perpetual and universal peace∗ The jubilee of all human nature. Pardon my exultation, if it be only an illusive prospect. Though the vision is fugacious as the purple tints of an evening sky, it is enchanting; it is as innocent as delightful. The very thought furnishes a rich banquet for Christian benevolence. But let us pause in our expressions of joy, for when we turn from the fancied Elysium, to sad reality, to scenes of blood and desolation, we are the more shocked by the dismal contrast. Let us then leave ideal pictures, and consider a moment the most rational means of promoting, as far as in our power, perpetual and universal peace. If war be a scourge, as it has been ever called and allowed to be, it must be inflicted for our offences. Then let every one, in every rank, the most elevated as well as the most abject, endeavour to propitiate the Deity, by innocence of life and obedience to the divine law, that the scourge may be no longer necessary. Let him add his prayers to his endeavours, that devastation may no more waste the ripe harvest, (while many pine with hunger,) burn the peaceful village, level the hut of the harmless cottager, overturn the palace, and deface the temple; destroying, in its deadly progress, the fine productions of art, as well as of nature: but that the shepherd's pipe may warble in the vale, where the shrill clarion and the drums dissonance now grate harshly on the ear of humanity; that peace, may be within and without our walls, and plenteousness in our cottages as well as in our palaces; that we may learn to rejoice in subduing ourselves, our pride, whence cometh contention and all other malignant passions, rather than in reducing fair cities to ashes, and erecting a blood-stained [369] streamer in triumph over those who may have fallen indeed—but fallen in defending with bravery, even to death, their wives, their children, their houses, and their altars, from the destroying demon of offensive war.

O thou God of mercy, grant that the sword may return to its scabbard for ever; that the religion of Jesus Christ may be duly understood, and its benign influence powerfully felt by all kings, princes, rulers, nobles, counsellors, and legislators, on the whole earth; that they may all combine in a league of philanthropy, to enforce by reason and mild persuasion, the law of love, or Christian charity, among all mankind, in all climes, and in all sects; consulting, like superior beings, the good of those beneath them; not endeavouring to promote their own power and aggrandizement by force and arms; but building their thrones, and establishing their dominion on the hearts of their respective people, preserved from the horrors of war by their prudence and clemency: and enjoying, exempt from all unnecessary burthens, the fruits of their own industry; every nation thus blest, permitting all others under the canopy of heaven to enjoy the same blessings uninterrupted, in equal peace and security. O melt the hard heart of pride and ambition, that it may sympathize with the lowest child of poverty, and grant, O thou God of order, as well as of mercy and love, that we of this happily constituted nation may never experience the curse of despotism on one hand; nor, on the other, the cruel evils of anarchy; that as our understandings become enlightened by science, our hearts may be softened by humanity, that we may be ever free, not using our liberty as a cloak for licentiousness, that we may all, in every rank and degree, live together peaceably in Christian love, and die in Christian hope, and that all nations [370] which the sun irradiates in his course, united in the bonds of amity, may unite also in the joyful acclamation of the text, with heart and voice, and say, "Glory to God in the highest, on earth peace, good-will towards men."

Endnotes

Ιδιοται is the Greek term for the idea, which means men of common coarse minds, uncultivated by philosophy, "et us studiis quae ad humanitatem pertinent."

And God Almighty give you mercy before the man.—If I be bereaved of my children, I am bereaved. Gen. xliii. 14.

The above is a quotation from a little treatise entitled "A Project for perpetual Peace."