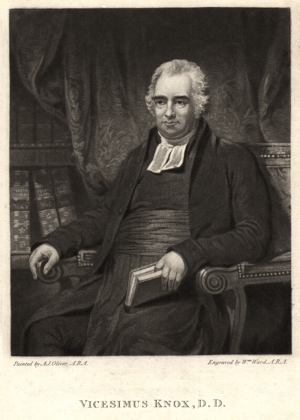

Vicesimus Knox, ANTIPOLEMUS; OR, THE PLEA OF REASON, RELIGION, AND HUMANITY, AGAINST WAR. A FRAGMENT; TRANSLATED FROM THE LATIN OF ERASMUS (1795)

|

|

Note: This is part of a collection of works by Vicesimus Knox.

Source

"Antipolemus; or, the Plea of Reason, Religion, and Humanity, Against War. A Fragment; translated from the Latin of Erasmu"* (1795), in The Works of Vicesimus Knox, D.D. with a Biographical Preface. In Seven Volumes (London: J. Mawman, 1824).vol. 5, pp. 405-97. [PDF]

- preface by the Translator, p. 407-30

- Antipolemus, p. 431-97.

PREFACE.

Unless either Philosophers bear rule in states, or those who are now called Kings and Potentates, learn to philosophise justly and properly, and thus both civil power and philosophy are united in the same person, it appears to me that there can be no cessation of calamity either to states or to the whole human race.

IT pleases Almighty God to raise up, from time to time, men of extraordinary abilities, combined with virtues no less extraordinary; who, in the dark night of ignorance and prejudice, shine, like the nocturnal lamp of Heaven, with solitary but serene lustre; obscured indeed at first by the gathering clouds of envy, unseen awhile through the voluntary blindness of self-interest; almost extinguished by civil and ecclesiastical bigotry; but at length, bursting through every obstacle, and reflecting a steady light on those labyrinths of error which lead to misery. Such was ERASMUS; a name, at the mention of which, all that is great and good, and learned and free, feéls a sentiment of cordial respect, and rises to pay a voluntary obeisance.

God had given him an intellect in a state of vigour rarely indulged to the sons of men. Trained in the school of adversity, he sought and found in it the sweet solace of learning and virtue. He there cultivated his native talents by early and constant exercise; and thus accumulated, by indefatigable industry, a store of knowledge; which, by means of an eloquence scarcely exceeded in the golden ages, he lavishly disseminated over the world, at that time barren, dark, and dreary, to enlighten and to fertilize it.

God had given him not only a preeminent intellect, but a gift still more estimable, a good and feeling heart, a love of truth, a warm philanthropy, which prompted him to exert his fine abilities, totally regardless of mean honours, or sordid profits, in diffusing most important information, in an age when human misery was greatly augmented by gross ignorance, and when man, free-born but degraded man, was bound down in darkness, with double shackles, in the chains of a twofold despotism, usurping an absolute dominion, both in church and in state, over the body and the soul.

These two gifts combined formed an Erasmus; a man justly deemed and called the Phœnix of his age. He it was who led the way both to the revival of learning and the restoration of religion. Taste and polite letters are no less indebted to him than rational theology. Liberty acknowledges him as one of her noblest assertors. Had he not appeared and fought on the side of humanity, with the spear of truth and the lash of ridicule, Europe, instead of enjoying or contending for freedom at this hour, might perhaps have been still sunk in the dead repose of servitude, or galled with the iron hand of civil tyrants; allied, for mutual aid, in a villanous confederacy, with the despotism of ecclesiastics. Force and fraud, availing themselves of the superstitious fears of ignorance, had united against the people, conspired against the majority of men, and dealt their curses through the land without mercy or controul. Then rose Erasmus, not indeed furnished with the arms of the warrior, but richly adorned with the arts of peace. By the force of superior genius and virtue, he shook the Pontiff's chair under him, and caused the thrones of the despots to tremble. They shrunk, like the ugly birds of the evening, from the light; they wished to hide themselves in the smoke that they had raised around them; but the rays of his genius penetrated the artificial mist and exposed them to the derision of the deluded and oppressed multitude. The fortress of the tyrant and the mask of the hypocrite were both laid open on the combined attack of argument and ridicule.

It was impossible but that the penetrating mind of Erasmus should see the grave follies, and mark the sanctified villanies of his time. He saw them, and laughed them to scorn. He took the side of human nature; serving every body, and obliging nobody. He sought no reward, but the approbation of his God and his conscience; and left the little great ones to contend among themselves, unenvied and unrivalled by him, for coronets, mitres, croziers, and cardinals' hats, while he, undignified, untitled, unknown by any addition to the name of Erasmus, studied, and successfully promoted, the improvement and happiness of human nature; the great society of all human beings united under one king, their common Creator and Preserver.

As he marked and reprobated the folly and misery of superstition, so he saw and no less clearly demonstrated the absurdity, the wretchedness, and the wickedness of WAR. His heart felt for the misery of man, exposed by the perverseness of his rulers, in addition to the natural and moral evil he is doomed to suffer, to all the calamities of war. He found in his intellectual storehouse, arms sufficient to encounter this giant fiend in his castle. On the rock of Religion he planted the artillery of solid arguments. There they still stand; and when the impediments of prejudice, pride, malice, and ambition shall be removed, which now retard their operation, they will beat down the ill-founded citadel, but tressed as it is by all the arts and arms of human power, endeavouring to build a fancied fabric of selfish or private felicity on the wreck and ruins of human nature.

Erasmus demands attention. His learning, his abilities will reward attention. His disinterestedness secures, from all disinterested men, a most respectful attention. Poor in the world, but rich in genius; obscure at his birth, and unpreferred at his death, but illustrious by his virtues, he became the self-appointed champion of man, a volunteer in the service of miserable mortals, an unbought advocate in the cause of those who could only repay him with their love and their prayers; the poor outcast, the abject slave of superstition or tyranny, and all the nameless, numberless sons of want and woe, born only to suffer and to die.

This great man has actually succeeded in exploding ecclesiastical tyranny: for we are greatly indebted to him for the reformation. We feel at this hour, and acknowledge with alacrity, the benefit of his theological labours in removing one cruel prejudice. It is true he has not yet succeeded in abolishing war. Success was more difficult, where arguments only were to be opposed to men of violence, armed with muskets, bayonets, and trains of artillery. The very din of arms stifles the still small voice of reason. But the friends of man will not yet despair, Erasmus their guide; God and nature urging their exertions, and a bleeding world imploring their merciful interference. Theirs is a real crusade: the olive, the dove, and the cross, their standards; the arts of persuasion, their arms; mercy to man, their watch-word; the conquest of pride, prejudice, and passion, their victory; peace and happiness, truth and justice, religion and piety, their trophies and reward.

With such enemies as pride, prejudice, and passion, the conflict must be long and obstinate. The beneficent efforts of Erasmus were violently opposed while he lived, and his name aspersed with the blackest calumny. Where indeed is the great benefactor to society at large, the friend of man, not of a faction, who has not been opposed, who has not been calumniated by those who are selfishly interested in the misery of others, and personally benefitted by the continuation of abuse? By what description of men was Erasmus opposed? By sordid worldlings, wearing the cloak of religion, to hide the ugliness of their avarice and ambition; by opulent dunces, whose stupidity was exceeded by nothing but their malice, selfishly wallowing in luxury, and forgetful that any existed but themselves, with rights to God's best gifts, life, comfort, peace, and liberty; by wretches sunk in the dull indolence of unwieldy pomp, who claimed a prescriptive right to respect; and considered all the active part of mankind as mere vassals, and all that dared to suggest improvement, either civil or ecclesiastical, as dangerous and seditious innovators; by priests, who thought, and indeed justly thought, that, in proportion as the light of knowledge was diffused, their craft was in danger. By these, and such as these, Erasmus was opposed in his endeavours to revive learning, and to reform religion. But, great by nature, a lord by God's creation, a pontiff by the election of his own superior genius, virtue, learning, and piety, he rose above all his opposers. They feared and honoured, while they hated and calumniated him. Popes, emperors, and kings courted his favour; and through dread of his heaven-bestowed power, paid him a sincerer and more reverential homage than they ever extorted from their myrmidons. Though he was stigmatized as an innovator, menaced, slandered, harassed by literary controversy, they felt the weight of his superiority, bowed to him from their thrones, and would gladly have domesticated him in their palaces; but he spurned their offers, and preferred, to the most splendid servitude, that liberty which he loved, and whose charms he had displayed to nations pining in darkness and in dungeons. Such, to the honour of truth and goodness, of genius and learning, such was the natural dominion of real and indisputable abilities, preserved in a state of independence by a virtue equally real, and a spirit truly noble. Every one has probably heard, that it has been said by Bruyere, and repeated by all true friends to personal merit, that "he who cannot be an Erasmus, must content himself with being a bishop." One may go farther and say, that he who cannot be an Erasmus, must condescend to a second rank, and be satisfied with becoming a pope, or an emperor. The dominion of genius and virtue like his was indeed of divine right. It was the gift of God for the good of man.

I have thus submitted my ideas, and the ideas of his own age, and of all the protestant literati, concerning the author of this Fragment on War, which I now place before the English reader. In the course of my reading I found it accidentally; and, struck with its excellence, translated it freely; modernising it, and using, where perspicuity seemed to require, the allowed liberty of occasional paraphrase. I have not indeed scrupled to make those slight alterations or additions which seemed necessary, to give the author's ideas more completely to the English reader, and to render the meaning fully intelligible, without a marginal commentary. It will occur to every one, that the purposes of philanthropy rather than of philology, the happiness of human nature rather than the amusements of verbal criticism, were intended by the author, as well as the translator, in this Dissertation.

There will never be wanting pamphleteers and journalists to defend war, in countries where prime ministers possess unlimited patronage in the church, in the law, in the army, in the navy, in all public offices, and where they can bestow honours, as well as emoluments, on the obsequious instruments of their own ambition. It seems now to be the general wish of indolent luxury in high life, to throw itself on the public for maintenance; but the strongest bridge may break when overladen. Truth will then prevail; and venality and corruption, exceeding all bounds, be driven into everlasting exile.

It gives me pleasure to discover, that my own favourable opinion of this philanthropic piece is confirmed by so great a critic as Bayle; whose words are these, in a note on the life of Erasmus:

"Jamais homme n'a été plus éloigné que lui de l'humeur impétueuse de certains théologiens, qui se plairent à corner la guerre. Pour lui, il aimoit la paix et il en connoissoit l'importance.

Une des plus belles dissertations, que l'on puisse lire est celle d'Erasme sur le proverbe, Dulce bellum inexpertis. Il y fait voir qu'il avoit profondement médité les plus importans principes de la raison et de l'évangile, et les causes les plus ordinaires des guerres. Il fait voir que la méchanceté de quelques particuliers, et la sottise1 des peuples, produirent presque toutes les guerres; et qu'une chose, dont les causes sont si blamables, est presque toujours suivie d'une très pernicieux effet. Il prétend que ceux que leur profession devroit le plus engager à déconseiller les guerres, en sont les instigateurs.*****

"Les loix, poursuit-il, les statuts, les priviléges, tout cela demeure sursis, pendant le fracas des armes. Les Princes trouvent alors cent moiens de parvenir à la puissance arbitraire; et de là vient, que quel-ques-uns ne sauroient suffrir la paix."

Near three hundred years have elapsed since the composition of this Treatise. In so long a period, the most enlightened which the history of the world can display, it might be supposed that the diffusion, of Christianity, and the improvements in arts, sciences, and civilisation, would either have abolished war, or have softened its rigour. It is however a melancholy truth, that war still rages in the world, polished as it is, and refined by the beautiful arts, by the belles lettres, and by a most liberal philosophy. Within a few years the warriors of a mighty and a Christian kingdom, were instructed to hire the savages of America to fight against a sister nation, or rather its own child; a nation speaking the same language with its parent, worshipping the same God, and hoping to become a joint heir of immortality. The savages were furnished with hatchets, to cut and hack the flesh and bones of their fellow Christians; of those who may be deemed in a political sense, their brothers, sisters, and children. The savages cruel enough by nature, finding their cruelty encouraged by Christians, used the hatchet, the tomahawk, and the scalping knife, with redoubled alacrity. The poor Indians were called, by those who justified the employment of them, the means which God and nature put into their hands; and the engaging of them on their side was thought a master-stroke of political wisdom. They were rewarded with money, and numbered among good and faithful allies.2 After efforts so execrable, the very party which put the hatchet into the hands of the savages, for the purpose of hewing their brothers in pieces, was vanquished, and piled their arms with ignominy, in sight of an insulted foe; leaving posterity to contemplate the scene with the indignation ever due to savage barbarity, and at the same time, with the contempt which naturally falls on malice of intention, cruelly displayed without power of execution.

Have the great and polished nations of Europe profited by this detestable example, and avoided every approach to barbarity? What must we think of the Duke of Brunswick's manifesto? What must be said of engaging Algerine pirates, against in-offensive merchantmen pursuing their business in the great waters; what of instigating the Indians of America once more, against a friendly nation in a state of perfect peace? Rumours of such enormous cruelty and injustice, in very recent times, have been diffused by men in high rank, and of most indisputable authority. If they are founded, never let it be said that the arguments against war, which Erasmus and other philanthropists have used, are needless, in the present times of boasted lenity and refinement. Have the French, or the Germans, or the Russians conducted themselves with such exemplary humanity, as to prove to the world that exhortations to it are no longer necessary? Tens of thousands of those who could answer this question most accurately, are now sleeping in the grave; where the wicked cease from troubling, and the weary are at rest.

The ferocity of native barbarians admits of some excuse, from their state of ignorance unenlightened, and of passion unsoftened, by culture. They profess not a religion which teaches to forgive. But a similar ferocity, coolly, deliberately approved, recommended, and enforced by the highest authority, in a state justly pretending to all the polish of cultivated manners, and professing the purest Christianity, is mischievous, flagitious, and detestable, without one alleviating circumstance. The blackness of the deed is not diluted with one drop of a lighter colour to soften the shade. Let the curtain fall upon the picture. Let no historian record such conduct in the annals of his country, lest it be deemed by posterity a libel on human nature.

To eradicate from the bosom of man principles which argue not only obduracy, but malignity, is certainly the main scope of the Christian religion; and the clergy are never better employed in their grand work, the melioration of human nature, the improvement of general happiness, than when they are reprobating all propensities whatever, which tend, in any degree, to produce, to continue, or to aggravate the calamities of war; those calamities which, as his majesty graciously expressed it, in one of his speeches from the throne,3 are inseparable from a state of war.

The most ardent zeal, the most pertinacious obstinacy is displayed in preserving the minutest article of what is called orthodox opinion. But, alas! what, in a world of woe like this, what signifies our boasted orthodoxy in matters of mere speculation, in matters totally irrelevant to human happiness or misery? What signifies a jealous vigilance over thirty-nine articles, if we neglect one article, the law of charity and love; if we overlook the weightier matters, which CHRIST himself enacted, as articles of his religion, indispensably to be subscribed by all who hope for salvation in him; I mean forgiveness of injuries, mercy, philanthropy, humility? There is nothing so heterodox, I speak under the correction of the reverend prelacy, as war, and the passions that lead to it, such as pride, avarice, and ambition. The greatest heresy I know, is to shed the blood of an innocent man, to rob by authority of a Christian government, to lay waste by law, to destroy by privilege, that which constitutes the health, the wealth, the comfort, the happiness, the sustenance of a fellow-creature, and a fellow Christian. This is heresy and schism with a vengeance! against which we ought most devoutly to pray, in a daily litany, or a new form of prayer. Where, after all the heart-burnings and blood-shedding occasioned by religious wars; where is the true church of Christ, but in the hearts of good men; the hearts of merciful believers, who from principle, in obedience to and for the love of Christ, as well as from sympathy, labour for peace, go about doing good, consulting, without local prejudice, the happiness of all men, and instead of confining their good offices to a small part, endeavour to pour oil into the wounds of suffering human nature? In the hearts of such men, united in love to God and his creatures, is the church of Christ. Stone walls and steeples are not necessary to the true church; and mitres and croziers are little better than helmets and swords, when the wearers of them countenance by their counsels, or even connive at by their silence, the unchristian passions and inhuman practices inseparable from a state of war. The poor soldier in the field is but an instrument in the hands of others. The counsellors of war;—they are the warriors. The ministers of state;—they are the disturbers of peace; and surely it is lawful to censure them, for their heads are unanointed.

The passions which lead to war are diseases. Is there no medicine for them? There is a medicine and an antidote. There is a catholicon provided by the great Physician; and it is the pious office of the clergy to administer it, œgris mortalibus, to poor mortals lying sick in the great hospital of the world. " Take physic, Pomp," they may say to all princes who delight in war;—imbibe the balsamic doctrines of the gospel. Pride, avarice, and ambition, are indeed difficult to cure; but it must be remembered that the medicine is powerful; and the good physician, instead of despairing, redoubles his efforts, when the disease is inveterate.

I hope the world has profited too much by experience, to encourage any offensive war, under the name and pretext of a holy war. Whether religion has been lately made use of to justify war, let others judge. We read in a recent form, an ardent prayer for protection against "those who, in the very centre of Christendom, threaten destruction to Christianity, and desolation to every country where they can erect their bloody standard!" It is meet, right, and our bounden duty to pray for protection against such men; but it would be alarming to those who remember the dreadful havoc of religious wars in former ages, if at this period, religion were publicly and solemnly assigned as a reason for continuing war. I think the apostolical method of converting the " declared enemies to Christian kings, and impious blasphemers of God's holy name," must be more desirable to bishops and archbishops than the arm of flesh, the sword of the destroyer. The prayer ends with these words: "We are devoutly sensible, that all our efforts will be ineffectual, unless thou, O God, from whom cometh our help, and from whom alone it can come, goest forth with our fleets and armies. Our counsels, our hands, and our hearts, are under thy Almighty direction. Direct them, (the hands, &c.) O Lord, to such exertions as may manifest us to be under thy guidance. Convince our adversaries that thine arm (assisted by our hands) stretched out, can defeat the most daring designs against our peace; and that those who lift up their banners against thee, (that is, against us), shall be humbled under thy Almighty hand." If this is not to represent a war as a holy war, what constitutes a holy war? As the prayer comes from great authority, it is to be received with deference; but it may be lawful to suggest, that it would have been very consistent with Christianity to have prayed in general terms, for peace without blood; to have prayed for our "adversaries" that they might be " convinced" of their fatal errors, not by our hands, but by persuasion, and by the grace of God. There follows indeed another very ardent prayer for our enemies; than which nothing can be more proper. It is only to be lamented, that Christianity should be represented in the former prayer, by those who are supposed best to understand it, as in any respect countenancing the propagation of the faith, or the conversion of unbelievers, by the sword, by fleets and armies, by exertions of the hand in the field of battle. Let Mahomet mark the progress of the faith by blood. Such modes of erecting the Cross are an abomination to Jesus Christ. Is it, after all, certain, that the slaughter of the unbelievers will convert the survivors to the religion of the slaughterers? Is the burning of a town, the sinking of a ship, the wounding and killing hundreds of thousands in the field, a proof of the lovely and beneficent spirit of that Christianity to which the enemy is to be converted, by the philanthropic warriors? Have not Jews, Turks, and infidels of all descriptions, triumphed in the everlasting wars of those who profess to be the disciples of the peaceful Jesus, the teachers and preachers of the gospel of peace?

The composers of these prayers are probably pious and good men; but, in treading in the footsteps of less enlightened predecessors, are they not, without intending it, rendering religion subservient to a secular ambition? They sometimes censure politics as the subject of sermons; but are politics more allowable in prayers than in sermons? and is it right in twelve million of men to pray, by order of the shepherds of their souls, for vengeance from their common Father on thirty million? To pray for mercy on them all; to pray that wars may cease over the whole world; to pray that those who have erred and are deceived may be persuaded to think and to do what is right;—This is indeed princely, episcopal, Christian, and humane.

The Christian religion is either true or untrue. If true, as the church teaches, as I firmly believe, and as the law requires us all to believe; then it must be of the highest importance to men individually, and therefore in the aggregate. It is the first concern of the whole human race. National policy shrinks to nothing, in comparison with the happiness of the universal family of all mankind. If the Christian religion be true, it must supersede all the measures of worldly wisdom, which obstruct its views or interfere with its doctrines; therefore it must supersede war: if false, then why a national establishment of it, in the very country which pronounces it false? why an order of clergy publicly maintained to sup port it? why do we see churches every where rising around us? why this hypocrisy? why is it not abolished, as an obstacle to military operations, and to other transactions of state necessity? The language of deeds is more credible than the language of words; and the language of deeds asserts that the Christian religion is untrue. They who defend war, must defend the dispositions which lead to war; and these dispositions are absolutely forbidden by the gospel. The very reverse of them is inculcated in almost every page. Those dispositions being extinguished, war must cease; as the rivulet ceases to flow when the fountain is destitute of water; or as the tree no longer buds and blossoms, when the fibres, which extract the moisture from the earth, are rescinded or withered. It is not necessary that there should be in the gospel an absolute prohibition of war in so many express words; it is enough that malice and revenge are prohibited. The cause ceasing, the effect can be no more. Therefore I cannot think it consistent with the duty of a bishop, or any other clergyman, either to preach or pray in such a manner as to countenance, directly or indirectly, any war, but a war literally, truly, and not jesuitically, a defensive war pro aris et focis; and even then, it would be more characteristic of Christian divines to pray for universal peace, for a peaceable conversion of the hearts of our enemies, rather than for bloody victory.

Wars of ambition, for the extension of empire or for the gratification of pride, envy, and malice, can never be justified; and therefore it is, that all belligerent powers agree to call their several wars defensive in the first instance, and then, just and necessary. This is a tacit, but a very striking acknowledgment, on all sides, that offensive war is unjustifiable. But the misfortune is, that power is never without the aid of ingenious sophistry to give the name of right to wrong; and, with the eloquence which Milton attributes to the devil, to make the worse appear the better cause.

But as war is confessedly PUBLICA MUNDI CALAMITAS, the common misfortune of all the world, it is time that good sense should interpose, even if religion were silent, to controul the mad impetuosity of its cause, ambition. Ambition is a passion in itself illimitable. Macedonia's madman was bounded in his ravages by the ocean. The demigod, Hercules, was stopt in his progress by the pillars, called after his name, at Gades; but to ambition, connected as it usually is, in modern times, with avarice, there is no ocean, no Gades, no limit, but the grave. Had Alexander, Caesar, Charles the Twelfth, or Louis the Fourteenth, been immortal in existence on earth, as they are in the posthumous life of fame, they must have shared the world among them in time, and reigned in it alone, or peopled with their own progeny. The middle ranks, among whom chiefly resides learning, virtue, principle, truth, every thing estimable in society, would have been extinct. Despots would have let none live but slaves; and those only, that they might administer to their idleness, their luxury, their vice. But though Alexander and Caesar, and Charles and Louis, are dead, yet ambition is still alive, and nothing but the progress of knowledge in the middle ranks, and the prevalence of Christianity in the lowest, have prevented other Alexanders, other Cæsars, other Charleses, and other Louises, from arising, and, like the vermin of an east wind, blasting the fairest blossoms of human felicity. Many Christian Rulers might with great propriety employ, like the Heathen, a remembrancer, to sound for ever in their ears, Forget not that thou art a man; to tell them, that the poorest soldier under their absolute command was born, like them, of woman, and that they like him shall die. The clergy, in Christian countries, possess this office of remembrancers to the great as well as to the little. To execute it they probably go to courts. They do well: let them not fear to execute it with fidelity. The kingdom of Christ should be maintained by them, so long as it is tenable, by argument and the mild arts of evangelical persuasion, though all other kingdoms fall. The Christian religion being confessedly true, there is a kingdom of Christ; and the laws of that kingdom must be of the first obligation. No sophistry can elude the necessary conclusion, "FIAT VOLUNTAS DEI; ADVENIAT REGNUM EJUS;" such is our daily prayer, and such should be our daily endeavour.

If it be true, that infidelity is increasing, if a great nation be indeed throwing aside Christianity, instead of the superstition that has disgraced it; it is time that those who believe in Christianity, and are convinced that it is beneficial to the world, show mankind its most alluring graces, its merciful, benignant effects, its utter abhorrence of war, its favourable influence on the arts of peace, and on all that contributes to the solid comfort of human life. But it is possible that, as it is usual to bend a crooked stick in the contrary direction in order to make it straight, so this great nation, in exploding the follies and misery of superstition, may be using a latitude and licentiousness of expression concerning the Christian religion, which it does not itself sincerely approve, merely to abolish the ancient bigotry. The measure is, I think, wrong, because it is of dangerous example; but whoever thinks so, ought to endeavour to rectify the error by persuasion, rather than to extirpate the men, by fire and sword, who have unhappily fallen into it. Their mistakes call upon their fellow-men for charity, but not for vengeance. Vengeance is mine, I will repay, saith the Lord. Our own mild and Christian behaviour towards those who are in error, is the most likely means of bringing them into the pale of Christianity, by the allurement of an example so irresistibly amiable. If the sheep have gone astray, the good shepherd uses gentle means to bring them into the fold. He does not allow the watchful dog to tear their fleeces; he does not send the wolf to devour them; neither does he hire the butcher to shed their blood, in revenge for their deviation. But who are we? Not shepherds, but a part of the flock. The spiritual state of thirty million of men is not to be regulated, any more than their worldly state, by twelve million. Are the twelve million all Christians, all qualified by their superior holiness to be either guardian or avenging angels? It is indeed most devoutly to be wished, that religion in the present times may not be used, as it has often been in former days, to sharpen the sword of war, and to deluge the world with gore. Let these matters remain to be adjusted, not by bullets and bayonets, but between every man's own conscience and God Almighty.

It is obvious to observe, that great revolutions are taking place, I mean not political revolutions; but revolutions in the mind of man, revolutions of far more consequence to human nature, than revolutions in empire. Man is awaking from the slumber of childish superstition, and the dreams of prejudice. Man is becoming more reasonable; assuming with more confidence his natural character, approaching more nearly his original excellence as a rational being, and as he came from his Creator. Man has been metamorphosed from the noble animal God made him, to a slavish creature little removed from a brute, by base policy and tyranny. He is now emerging from his degenerate state. He is learning to estimate things as they are clearly seen, in their own shape, size, and hue; not as they are enlarged, distorted, discoloured by the mists of prejudice, by the fears of superstition, and by the deceitful mediums which politicians and pontiffs invented, that they might enjoy the world in state without molestation.

War has certainly been used by the great of all ages

and countries except our own, as a means of supporting

an exclusive claim to the privileges of enormous opulence,

stately grandeur, and arbitrary power. It employs

the mind of the multitude, it kindles their passions

against foreign, distant, and unknown persons, and

thus prevents them from adverting to their own oppressed

condition, and to domestic abuses. There is something

fascinating in its glory, in its ornaments, in its

music, in its very noise and tumult, in its surprising

events, and in victory. It assumes a splendour, like

the harlot, the more brilliant, gaudy, and affected,

in proportion as it is conscious to itself of internal

deformity. Paint and perfume are used by the wretched

prostitute in profusion, to conceal the foul ulcerous

sores, the rottenness and putrescence of disease.

The vulgar and the thoughtless, of which there are

many in the highest ranks, as well as in the lowest,

are dazzled by outward glitter. But improvement of

mind is become almost universal, since the invention

of printing; and reason, strengthened by reading,

begins to discover, at first sight and with accuracy,

the difference between paste and diamonds, tinsel

and bullion. It begins to see that there can be no

glory in mutual destruction;

that real glory can be derived only from beneficial

exertions, from contributions to the conveniencies

and accommodations of life; from arts, sciences, commerce,

and agriculture; to all which war is the bane. It

begins to perceive clearly the truth of the poor Heathen's

observation,

The great is not therefore good; but

the good is therefore great.

The great is not therefore good; but

the good is therefore great.

It is indeed difficult to prevent the mind of the many from admiring the splendidly destructive, and to teach it duly to appreciate the useful and beneficial, unattended with ostentation. There are various prejudices easily accounted for, which from early infancy familiarize the ideas of war and slaughter, which would otherwise shock us. The books read at school were mostly written before the Christian era, They celebrate warriors with an eloquence of diction, and a spirit of animation, which cannot fail to captivate a youthful reader. The more generous his disposition, the quicker his sensibility, the livelier his genius, the warmer his imagination, the more likely is he, in that age of inexperience, to catch the flame of military ardour. The very ideas of bloody conquerors are instilled into his heart, and grow with his growth. He struts about his school, himself a hero in miniature, a little Achilles panting for glorious slaughter. And even the vulgar, those who are not instructed in classical learning by a Homer or a Cæsar, have their Seven Champions of Christendom, learn to delight in scenes of carnage, and think their country superior to all others, not for her commerce, not for her liberty, not for her civilisation, but for her bloody wars. Happily for human nature, great writers have lately taken pains to remove those prejudices of the school and nursery, which tend to increase the natural misery of man; and consequently war, and all its apparatus begin to be considered among those childish things, which are to be put away in the age of maturity. It will indeed require time to emancipate the stupid and unfeeling slaves of custom, fashion, and self-interest, from their more than Egyptian bondage.

Erasmus stands at the head of those writers who have attempted the emancipation. With as much wit and comprehension of mind as Voltaire and Rousseau; he has the advantage of them in two points, in sound learning, and in religion. His learning was extensive and profound, and there is every reason to believe that he was a sincere Christian. His works breathe a spirit of piety to God, equalled only by his benevolence to man. The narrow-minded politicians, who look no farther than to present expedients, and cannot open their hearts wide enough to unite in their minds the general good of human nature, with the particular good of their own country, will be ready to explode his observations on the malignity of war. But till they have proved to the suffering world, that their heads and hearts are superior to Erasmus, they will not diminish his authority by invective or derision. Let ministers of state, who, by the way, are always cried up as paragons of ability, wonders of the world, for the time being; let under-secretaries, commissioners, commissaries, contractors, clerks, and borough-jobbers, the warm patrons of all wars; let these men prove themselves superior in intellect, learning, piety, and humanity, to Erasmus, and I give up the cause. Let war fill their coffers, and cover them all over with ribands, stars, and garters; let them praise and glorify each other; let them rejoice and revel in the song and the dance; and let the stricken deer go weep, the middle ranks and the poor, who certainly constitute the majority of the human race, and who have in all ages fallen unpitied victims to war. MULTIS UTILE BELLUM, or the emoluments of war, sufficiently account for the opposition which some men make to peace and to peace-makers.

But the cause is ultimately safe in the hands of Erasmus; for he has established it on the rock Truth. It stands on the same base with the Christian religion. Reason, humanity, and sound policy, are among the columns that firmly support it; and to use the strong language of Scripture, the gates of hell shall not finally prevail against it. Let it be remembered that the reformation of religion was more unlikely in the twelfth century, than the total abolition of war in the eighteenth.

I hope and believe, I am serving my fellow-creatures in all climes, and of all ranks, in bringing forward this Fragment; in reprobating war, and in promoting the love of peace. That my efforts may be offensive to particular persons who are the slaves of prejudice, pride, and interest, is but too probable. I sincerely lament it. But whatever inconvenience I may suffer from their temporary displeasure, I cannot relinquish the cause. The total abolition of war, and the establishment of perpetual and universal peace, appear to me to be of more consequence than any thing ever achieved, or even attempted, by mere mortal man, since the creation. The goodness of the cause is certain, though its success, for a time, doubtful. Yet will I not fear. I have chosen ground, solid as the everlasting hills, and firm as the very firmament of heaven. I have planted an acorn; the timber and the shade are reserved for posterity.

It requires no apology to have placed before freemen, in their vernacular language, the sentiments of a truly good and wise man on a subject of the most momentous consequence. They accord with my own; and I have been actuated, in bringing them forward, by no other motive than the genuine impulse of humanity. I have no purposes of faction to serve. I am a lover of internal order as well as of public peace. I am duly attached to every branch of the constitution; though certainly not blind to some deviations from primitive and theoretical excellence, which time will ever cause in the best inventions of men. I detest and abhor atheism and anarchy as warmly and truly as the most sanguine abettors of war can do; but I am one who thinks, in the sincerity of his soul, that reasonable creatures ought always to be coerced, when they err, by the force of reason, the motives of religion, the operation of law; and not by engines of destruction. In a word, I utterly disapprove all war, but that which is strictly defensive. If I am in error, pardon me, my fellow-creatures; I trust I shall obtain the pardon of my God.

Footnotes

1. War is a game, which, were their subjects wise, Kings would not play at.———

COWPER.

2. A secretary of state, in a letter to General Carleton, dated Whitehall, March 26, 1777, says: "As this plan cannot be advantageously executed without the assistance of Canadians and Indians, his Majesty strongly recommends it to your care to furnish both expeditions with good and sufficient bodies of those men. And I am happy in knowing that your influence among them is so great, that there can be no room to apprehend you will find it difficult to fulfil his Majesty's intention."

In the "Thoughts for conducting the War from the Side of Canada," by General Burgoyne, that general desires a thousand or more savages. This man appears to have been clever, and could write comedies and act tragedies, utrinquè paratus.

Colonel Butler was desired to distribute the king's bounty-money among such of the savages as would join the army; and, after the delivery of the presents, he asks for 4011l. York currency, before he left Niagara. He adds, in a letter that was laid on the table in the House of Commons, "I flatter myself that you will not think the expense, however high, to be useless, or given with too lavish a hand. I waited seven days to deliver them the presents, and GIVE THEM THE HATCHET, which they accepted, and promised to make use of it." This letter is dated Ontario, July 28, 1777.

In another letter, Colonel Butler says, "The Indians threw in a heavy fire on the rebels, and made a shocking slaughter with their spears and hatchets. The success of this day will plainly show the utility of your excellency's constant support of my unwearied endeavours to conciliate to his majesty so serviceable a body of allies." This letter is from Colonel Butler to Sir Guy Carleton, dated Camp before Fort Stanwix, Aug. 15, 1777.—See also Burgoyne's proclamation.

In another letter to Sir Guy Carleton, of July 28, Colonel Butler very coolly says, "Many of the prisoners were, conformably to the Indian custom, afterwards killed." See more on this subject, in page 228 of a volume intituled "The Speeches of Mr. Wilkes," printed in the year 1786.

3. In the year 1777.

OR, THE PLEA OF REASON, RELIGION, AND HUMANITY, AGAINST WAR. A FRAGMENT; TRANSLATED FROM THE LATIN OF ERASMUS.

ANTIPOLEMUS; OR, THE PLEA OF REASON, RELIGION, AND HUMANITY, AGAINST WAR.

IF there is in the affairs of mortal men any one thing which it is proper uniformly to explode; which it is incumbent on every man, by every lawful means, to avoid, to deprecate, to oppose, that one thing is doubtless war. There is nothing more unnaturally wicked, more productive of misery, more extensively destructive, more obstinate in mischief, more unworthy of man as formed by nature, much more of man professing Christianity.

Yet, wonderful to relate! in these times, war is every where rashly, and on the slightest pretext, undertaken; cruelly and savagely conducted, not only by unbelievers, but by Christians; not only by laymen, but by priests and bishops; not only by the young and inexperienced, but even by men far advanced in life, who must have seen and felt its dreadful consequences; not only by the lower order, the rude rabble, fickle in their nature, but, above all, by princes, whose duty it is to compose the rash passions of the unthinking multitude by superior wisdom and the force of reason. Nor are there ever wanting men learned in the law, and even divines, who are ready to furnish firebrands for the nefarious work, and to fan the latent sparks into a flame.

Whence it happens, that war is now considered so much a thing of course, that the wonder is, how any man can disapprove of it; so much sanctioned by authority and custom, that it is deemed impious, I had almost said heretical, to have borne testimony against a practice in its principle most profligate, and in its effects pregnant with every kind of calamity.

How much more justly might it be matter of wonder, what evil genius, what accursed fiend, what hell-born fury first suggested to the mind of man, a propensity so brutal, such as instigates a gentle animal, formed by nature for peace and good-will, formed to promote the welfare of all around him, to rush with mad ferocity on the destruction of himself and his fellow-creatures!

Still more wonderful will this appear, if, laying aside all vulgar prejudices, and accurately examining the real nature of things, we contemplate with the eyes of philosophy, the portrait of man on one side, and on the other the picture of war!

In the first place then, if any one considers a moment the organization and external figure of the body, will he not instantly perceive, that nature, or rather the God of nature, created the human animal not for war, but for love and friendship; not for mutual destruction, but for mutual service and safety; not to commit injuries, but for acts of reciprocal beneficence.

To all other animals, nature, or the God of nature, has given appropriate weapons of offence. The inborn violence of the bull is seconded by weapons of pointed horn; the rage of the lion with claws. On the wild boar are fixed terrible tusks. The elephant, in addition to the toughness of his hide and his enormous size, is defended with a proboscis. The crocodile is covered with scales as with a coat of mail. Fins serve the dolphin for arms; quills the porcupine; prickles the thornback; and the gallant chanticleer, in the farm-yard, crows defiance, conscious of his spur. Some are furnished with shells, some with hides, and others with external teguments, resembling, in strength and thickness, the rind of a tree. Nature has consulted the safety of some of her creatures, as of the dove, by velocity of motion. To others she has given venom as a substitute for a weapon; and added a hideous shape, eyes that beam terror, and a hissing noise. She has also given them antipathies and discordant dispositions corresponding with this exterior, that they might wage an offensive or defensive war with animals of a different species.

But man she brought into the world naked from his mother's womb, weak, tender, unarmed; his flesh of the softest texture, his skin smooth and delicate, and susceptible of the slightest injury. There is nothing observable in his limbs adapted to fighting, or to violence; not to mention that other animals are no sooner brought forth, than they are sufficient of themselves to support the life they have received; but man alone, for a long period, totally depends on extraneous assistance. Unable either to speak, or walk, or help himself to food, he can only implore relief by tears and wailing; so that from this circumstance alone might be collected, that man is an animal born for that love and friendship which is formed and cemented by the mutual interchange of benevolent offices. Moreover, nature evidently intended that man should consider himself indebted for the boon of life, not so much to herself as to the kindness of his fellow man; that he might perceive himself designed for social affections, and the attachments of friendship and love. Then she gave him a countenance, not frightful and forbidding, but mild and placid, intimating by external signs the benignity of his disposition. She gave him eyes full of affectionate expression, the indexes of a mind delighting in social sympathy. She gave him arms to embrace his fellow-creatures. She gave him lips to express an union of heart and soul. She gave him alone the power of laughing; a mark of the joy of which he is susceptible. She gave him alone tears, the symbol of clemency and compassion. She gave him also a voice; not a menacing and frightful yell, but bland, soothing, and friendly. Not satisfied with these marks of her peculiar favour, she bestowed on him alone the use of speech and reason; a gift which tends more than any other to conciliate and cherish benevolence, and a desire of rendering mutual services; so that nothing among human creatures might be done by violence. She implanted in man a hatred of solitude, and a love of company. She sowed in his heart the seeds of every benevolent affection; and thus rendered what is most salutary, at the same time most agreeable. For what is more agreeable than a friend? what so necessary? Indeed if it were possible to conduct life conveniently without mutual intercourse, yet nothing could be pleasant without a companion, unless man should have divested himself of humanity, and degenerated to the rank of a wild beast. Nature has also added a love of learning, an ardent desire of knowledge; a circumstance which at once contributes in the highest degree to distinguish man from the ferocity of inferior animals, and to endear him cordially to his fellow-creature: for neither the relationship of affinity nor of consanguinity binds congenial spirits with closer or firmer bands, than an union in one common pursuit of liberal knowledge and intellectual improvement. Add to all this, that she has distributed to every mortal endowments, both of mind and body, with such admirable variety, that every man finds in every other man, something to love and to admire for its beauty and excellence, or something to seek after and embrace for its use and necessity. Lastly, kind nature has given to man a spark of the divine mind, which stimulates him, without any hope of reward, and of his own free will, to do good to all: for of God, this is the most natural and appropriate attribute, to consult the good of all by disinterested beneficence. If it were not so, how happens it that we feel an exquisite delight, when we find that any man has been preserved from danger, injury, or destruction, by our offices or intervention? How happens it that we love a man the better, because we have done him a service?

It seems as if God has placed man in this world, a representative of himself, a kind of terrestrial deity, to make provision for the general welfare. Of this the very brutes seem sensible, since we see not only tame animals, but leopards and lions, and, if there be any more fierce than they, flying for refuge, in extreme danger, to man. This is the last asylum, the most inviolable sanctuary, the anchor of hope in distress to every inferior creature.

Such is the true portrait of man, however faintly and imperfectly delineated. It remains that I compare it, as I proposed, with the picture of war; and see how the two tablets accord, when hung up together and contrasted.

Now then view, with the eyes of your imagination, savage troops of men, horrible in their very visages and voices; men, clad in steel, drawn up on every side in battle array, armed with weapons, frightful in their crash and their very glitter; mark the horrid murmur of the confused multitude, their threatening eye-balls, the harsh jarring din of drums and clarions, the terrific sound of the trumpet, the thunder of the cannon, a noise not less formidable than the real thunder of heaven, and more hurtful; a mad shout like that of the shrieks of bedlamites, a furious onset, a cruel butchering of each other!—See the slaughtered and the slaughtering!—heaps of dead bodies, fields flowing with blood, rivers reddened with human gore!—It sometimes happens that a brother falls by the hand of a brother, a kinsman upon his nearest kindred, a friend upon his friend, who, while both are actuated by this fit of insanity, plunges the sword into the heart of one by whom he was never offended, not even by a word of his mouth!—So deep is the tragedy, that the bosom shudders even at the feeble description of it, and the hand of humanity drops the pencil while it paints the scene.

In the mean time I pass over, as comparatively trifling, the corn-fields trodden down, peaceful cottages and rural mansions burnt to the ground, villages and towns reduced to ashes, the cattle driven from their pasture, innocent women violated, old men dragged into captivity, churches defaced and demolished, every thing laid waste, a prey to robbery, plunder, and violence!

Not to mention the consequences which ensue to the people after a war, even the most fortunate in its event, and the justest in its principle: the poor, the unoffending common people, robbed of their little hard-earned property: the great, laden with taxes: old people bereaved of their children; more cruelly killed by the murder of their offspring than by the sword; happier if the enemy had deprived them of the sense of their misfortune, and life itself, at the same moment: women far advanced in age, left destitute, and more cruelly put to death, than if they had died at once by the point of the bayonet; widowed mothers, orphan children, houses of mourning; and families, that once knew better days, reduced to extreme penury.

Why need I dwell on the evils which morals sustain by war, when every one knows, that from war proceeds at once every kind of evil which disturbs and destroys the happiness of human life?

Hence is derived a contempt of piety, a neglect of law, a general corruption of principle, which hesitates at no villany. From this source rushes on society a torrent of thieves, robbers, sacrilegists, murderers; and, what is the greatest misfortune of all, this destructive pestilence confines not itself within its own boundaries; but, originating in one corner of the world, spreads its contagious virulence, not only over the neighbouring states, but draws the most remote regions, either by subsidies, by marriages among princes, or by political alliances, into the common tumult, the general whirlpool of mischief and confusion. One war sows the seeds of another. From a pretended war, arises a real one; from an inconsiderable skirmish, hostilities of most important consequence; nor is it uncommon, in the case of war, to find the old fable of the Lernæan lake, or the Hydra, realized. For this reason, I suppose, the ancient poets (who penetrated into the nature of things with wonderful sagacity, and shadowed them out with the aptest fictions) handed down by tradition, that war originated from hell, that it was brought thence by the assistance of furies, and that only the most furious of the furies, Alecto, was fit for the infernal office. The most pestilent of them all was selected for it,

———Cui nomina mille,

Mille nocendi Artes.

VIRG.

As the poets describe her, she is armed with snakes without number, and blows her blast in the trumpet of hell. Pan fills all the space around her with mad uproar. Bellona, in frantic mood, shakes her scourge. And the unnatural, impious fury, breaking every bond asunder, flies abroad all horrible to behold, with a visage besmeared with gore!

Even the grammarians, with all their trifling ingenuity,

observing the deformity of war, say, that BELLUM,

the Latin word for war, which signifies also the beautiful,

or comely, was so called by the rhetorical figure

Contradiction,  because it has nothing in it either good or beautiful;

and that bellum is called bellum, by the same figure

as the furies are called Eumenides. Other etymologists,

with more judgment, derive bellum from bellua, a beast,

because it ought to be more characteristic of beasts

than of men, to meet for no other purpose than mutual

destruction.

because it has nothing in it either good or beautiful;

and that bellum is called bellum, by the same figure

as the furies are called Eumenides. Other etymologists,

with more judgment, derive bellum from bellua, a beast,

because it ought to be more characteristic of beasts

than of men, to meet for no other purpose than mutual

destruction.

But to me it appears to deserve a worse epithet than brutal; it is more than brutal, when men engage in the conflict of arms; ministers of death to men! Most of the brutes live in concord with their own kind, move together in flocks, and defend each other by mutual assistance. Indeed all kinds of brutes are not inclined to fight even their enemies. There are harmless ones like the hare. It is only the fiercest, such as lions, wolves, and tigers, that fight at all. A dog will not devour his own species; lions, with all their fierceness, are quiet among themselves; dragons are said to live in peace with dragons; and even venomous creatures live with one another in perfect harmony.—But to man, no wild beast is more destructive than his fellow man.

Again; when the brutes fight, they fight with the weapons which nature gave them; we arm ourselves for mutual slaughter, with weapons which nature never thought of, but which were invented by the contrivance of some accursed fiend, the enemy of human nature, that man might become the destroyer of man. Neither do the beasts break out in hostile rage for trifling causes; but either when hunger drives them to madness, or when they find themselves attacked, or when they are alarmed for the safety of their young. We, good Heaven! on frivolous pretences, what tragedies do we act on the theatre of war! Under colour of some obsolete and disputable claim to territory; in a childish passion for a mistress; for causes even more ridiculous than these, we kindle the flames of war. Among the beasts, the combat is for the most part only one against one, and for a very short space. And though the contest should be bloody, yet when one of them has received a wound, it is all over. Whoever heard (what is common among men in one campaign) that a hundred thousand beasts had met in battle for mutual butchery? Besides, as beasts have a natural hatred to some of a different kind, so are they united to others of a different kind, in a sincere and inviolable alliance. But man with man, and any man with any man, can find an everlasting cause for contest, and become, what they call, natural enemies; nor is any agreement or truce found sufficiently obligatory to bind man from attempting, on the appearance of the slightest pretexts, to commence hostilities after the most solemn convention. So true it is, that whatever has deviated from its own nature into evil, is apt to degenerate to a more depraved state, than if its nature had been originally formed with inbred malignity.

Do you wish to form a lively idea, however imperfect, of the ugliness and the brutality of war, (for we are speaking of its brutality,) and how unworthy it is of a rational creature? Have you ever seen a battle between a lion and a bear? What distortion, what roaring, what howling, what fierceness, what bloodshed! The spectator of a fray, in which mere brutes like these are fighting, though he stands in a place of safety, cannot help shuddering at a sight so bloody. But how much more shocking a spectacle to see man conflicting with man, armed from head to foot with a variety of artificial weapons! Who could believe that creatures so engaged were men, if the frequency of the sight had not blunted its effect on our feelings, and prevented surprise? Their eyes flashing, their cheeks pale, their very gait and mien expressive of fury; gnashing their teeth, shouting like madmen, the whole man transformed to steel; their arms clanging horribly, while the cannon's mouth thunders and lightens around them. It would really be less savage, if man destroyed and devoured man for the sake of necessary food, or drank blood through lack of beverage. Some, indeed, (men in form) have come to such a pitch as to do this from rancour and wanton cruelty, for which expediency or even necessity could furnish only a poor excuse. More cruel still, they fight on some occasions with weapons dipt in poison, and engines invented in Tartarus, for wholesale havoc at a single stroke.

You now see not a single trace of man, that social creature, whose portrait we lately delineated. Do you think nature would recognise the work of her own hand—the image of God? And if any one were to assure her that it was so, would she not break out into execrations at the flagitious actions of her favourite creature? Would she not say, when she saw man thus armed against man, "What new sight do I behold? Hell itself must have produced this portentous spectacle. There are, who call me a step-mother, because in the multiplicity of my works I have produced some that are venomous, (though even they are convertible to the use of man,) and because I created some, among the variety of animals, wild and fierce; though there is not one so wild and so fierce, but he may be tamed by good management and good usage. Lions have grown gentle, serpents have grown innoxious under the care of man. Who is this then, worse than a step-mother, who has brought forth a non-descript brute, the plague of the whole creation? I, indeed, made one animal, like this, in external appearance; but with kind propensities, all placid, friendly, beneficent. How comes it to pass, that he has degenerated to a beast, such as I now behold, still in the same human shape? I recognise no vestige of man, as I created him. What demon has marred the work of my hands? What Sorceress, by her enchantments, has discharged from the human figure, the human mind, and supplied its place by the heart of a brute? What Circe has transformed the man that I made into a beast? I would bid this wretched creature behold himself in a mirror, if his eyes were capable of seeing himself when his mind is no more. Nevertheless, thou depraved animal, look at thyself, if thou canst; reflect on thyself, thou frantic warrior, if by any means thou mayst recover thy lost reason, and be restored to thy pristine nature. Take the looking-glass, and inspect it. How came that threatening crest of plumes upon thy head? Did I give thee feathers? Whence that shining helmet? Whence those sharp points, which appear like horns of steel? Whence are thy hands and arms furnished with sharp prickles? Whence those scales, like the scales of fish, upon thy body? Whence those brazen teeth? Whence those plates of brass all over thee? Whence those deadly weapons of offence? Whence that voice, uttering sounds of rage more horrible than the inarticulate noise of the wild beasts? Whence the whole form of thy countenance and person distorted by furious passions, more than brutal? Whence that thunder and lightning which I perceive around thee, at once more frightful than the thunder of heaven, and more destructive to man? I formed thee an animal a little lower than the angels, a partaker of divinity; how camest thou to think of transforming thyself into a beast so savage, that no beast hereafter can be deemed a beast, if it be compared with man, originally the image of God, the lord of the creation?"

Such, and much more, would, I think, be the outcry of indignant Nature, the architect of all things, viewing man transformed to a warrior.

Now, since man was so made by nature, as I have above shown him to have been, and since war is that which we too often feel it to be, it seems matter of infinite atonishment, what demon of mischief, what distemperature, or what fortuitous circumstances, could put it into the heart of man to plunge the deadly steel into the bosom of his fellow-creature. He must have arrived at a degree of madness so singular by insensible gradations, since

Nemo repentè fuit turpissimus. JUV.

It has ever been found that the greatest evils have insinuated themselves among men under the shadow and the specious appearance of some good. Let us then endeavour to trace the gradual and deceitful progress of that depravity which produced war.

It happened then, in primeval ages, when men, uncivilized and simple, went naked, and dwelt in the woods, without walls to defend, and without houses to shelter them, that they were sometimes attacked by the beasts of the forest. Against these, man first waged war; and he was esteemed a valiant hero and an honourable chief who repelled the attack of the beasts from the sons of men. Just and right it was to slaughter them who would otherwise have slaughtered us, especially when they aggressed with spontaneous malice, unprovoked by all previous injury. A victory over the beasts was a high honour, and Hercules was deified for it. The rising generation glowed with a desire to emulate Hercules; to signalize themselves by the slaughter of the noxious animals; and they displayed the skins which they brought from the forest, as trophies of their victory. Not satisfied with having laid their enemies at their feet, they took their skins as spoils, and clad themselves in the warm fur, to defend themselves from the rigour of the seasons. Such was the blood first shed by the hand of man, such was the occasion, and such the spoils.

After this first step, man advanced still farther, and ventured to do that which Pythagoras condemned as wicked and unnatural, and which would appear very wonderful to us, if the practice were not familiarized by custom; which has such universal sway, that in some nations it has been deemed a virtuous act to knock a parent on the head, and to deprive him of life, from whom we received the precious gift; in others it has been held a duty of religion to eat the flesh even of near and dear departed friends who had been connected by affinity; it has been thought a laudable act to prostitute virgins to the people in the temple of Venus; and custom has familiarized some other practices still more absurd, at the very mention of which, every is one ready to pronounce them abominable. From these instances, it appears that there is nothing so wicked, nothing so atrocious, but it may be approved, if it has received the sanction of custom, the authority of fashion. From the slaughter of wild beasts, men proceeded to eat them, to tear the flesh with their teeth, to drink their blood; and, as Ovid expresses it, to entomb dead animals in their own bowels. Custom and convenience soon reconciled the practice (animal slaughter and animal food) to the mildest dispositions. The choicest dainties were made of animal food by the ingenuity of the culinary art; and men, tempted by their palate, advanced a step farther: from noxious animals which alone they had at first slaughtered for food, they proceeded to the tame, the harmless, and the useful. The poor sheep fell a victim to this ferocious appetite.

The hare was doomed also to die, because his flesh was a dainty viand: nor did they spare the gentle ox, who had long sustained the ungrateful family by his labours at the plough. No bird of the air, or fish of the waters, was suffered to escape; and the tyranny of the palate went such lengths, that no living creature on the face of the globe was safe from the cruelty of man. Custom so far prevailed, that no slaughter was thought cruel, while it was confined to any kind of animals, and so long as it abstained from shedding the blood of man.

But though we may prevent the admission of vices, as we may prevent the entrance of the sea; yet when once either of them is admitted, it is not in every one's power to say, "thus far shalt thou go, and no farther." When once they are fairly entered, they are no longer under our command, but rush on uncontrolled in the wild career of their own impetuosity.

Thus, after the human mind had been once initiated in shedding blood, anger soon suggested, that one man might attack another with the fist, a club, a stone, and destroy the life of an enemy as easily as of a wild beast. To such obvious arms of offence, they had hitherto confined themselves: but they had learned from the habit of depriving cattle of life, that the life of man could be also taken away by the same means without difficulty. The cruel experiment was long restricted to single combat: one fell, and the battle was at an end: sometimes it happened that both fell: both, perhaps, proving themselves by this act unworthy of life. It now seemed to have an appearance even of justice, to have taken off an enemy; and it soon was considered as an honour, if any one had put an end to a violent or mischievous wretch, such as a Cacus or Busiris, and delivered the world from such monsters in human shape. Exploits of this kind we see also among the praises of Hercules.

But when single combatants met, their partisans, and all those, whom kindred, neighbourhood, or friendship, had connected with either of them, assembled to second their favourite. What would now be called a fray or riot, was then a battle or a warlike action. Still, however, the affair was conducted with stones, or with sharp-pointed poles. A rivulet crossing the ground, or a rock opposing their progress, put an end to hostilies, and peace ensued.

In process of time, the rancour of disagreeing parties increased, their resentments grew warmer, ambition began to catch fire, and they contrived to give executive vigour to their furious passions, by the inventions of their ingenuity. Armour was therefore contrived, such as it was, to defend their persons; and weapons fabricated, to annoy and destroy the enemy.

Now at last they began to attack each other in various quarters with greater numbers, and with artificial instruments of offence. Though this was evidently madness, yet false policy contrived that honour should be paid to it. They called it war; and voted it valour and virtue, if any one, at the hazard of his own life, should repel those whom they had now made and considered as an enemy, from their children, their wives, their cattle, and their domestic retreat. And thus the art of war keeping pace with the progress of civilisation, they began to declare war in form, state with state, province with province, kingdom with kingdom.

In this stage of the progress they had indeed advanced to great degrees of cruelty, yet there still remained vestiges of native humanity. Previously to drawing the sword, satisfaction was demanded by a herald; Heaven was called to witness the justice of the cause; and even then, before the battle began, pacification was sought by the prelude of a parley. When at last the conflict commenced, they fought with the usual weapons, mutually allowed, and contended by dint of personal valour, scorning the subterfuges of stratagem and the artifices of treachery. It was criminal to aim a stroke at the enemy before the signal was given, or to continue the fight one moment after the commander had sounded a retreat. In a word, it was rather a contest of valour than a desire of carnage: nor yet was the sword drawn but against the inhabitants of a foreign country.

Hence arose despotic government, of which there was none in any country that was not procured by the copious effusion of human blood. Then followed continual successions of wars, while one tyrant drove another from his throne, and claimed it for himself by right of conquest. Afterwards, when empire devolved to the most profligate of the human race, war was wantonly waged against any people, in any cause, to gratify the basest of passions; nor were those who deserved ill of the lordly despot chiefly exposed to the danger of his invasions, but those who were rich or prosperous, and capable of affording ample plunder. The object of a battle was no longer empty glory, but sordid lucre, or something still more execrably flagitious. And I have no doubt but that the sagacious mind of Pythagoras foresaw all these evils, when, by his philosophical fiction of transmigration, he endeavoured to deter the rude multitude from shedding the blood of animals: he saw it likely to happen, that a creature who, when provoked by no injury, should accustom himself to spill the blood of a harmless sheep, would not hesitate, when inflamed by anger, and stimulated by real injury, to kill a man.

Indeed, what is war but murder and theft, committed by great numbers on great numbers? the greatness of numbers not only not extenuating its malignity, but rendering it the more wicked, in proportion as it is thus more extended, in its effects and its influence.

But all this is laughed at as the dream of men unacquainted with the world, by the stupid, ignorant, unfeeling grandees of our time, who, though they possess nothing of man but the form, yet seem to themselves little less than earthly divinities.

From such beginnings, however, as I have here described, it is certain, man has arrived at such a degree of insanity, that war seems to be the chief business of human life. We are always at war, either in preparation, or in action. Nation rises against nation; and, what the heathens would have reprobated as unnatural, relatives against their nearest kindred, brother against brother, son against father!—more atrocious still!—a Christian against a man! and worst of all, a Christian against a Christian! And such is the blindness of human nature, that nobody feels astonishment at all this, nobody expresses detestation. There are thousands and tens of thousands ready to applaud it all, to extol it to the skies, to call transactions truly hellish, a holy war. There are many, who spirit up princes to war, mad enough as they usually are of themselves; yet are there many who are always adding fuel to their fire. One man mounts the pulpit, and promises remission of sins to all who will fight under the banners of his prince. Another exclaims, "O invincible prince! only keep your mind favourable to the cause of religion, and God will fight (his own creatures) for you." A third promises certain victory, perverting the words of the prophetical Psalmist to the wicked and unnatural purposes of war. "Thou shalt not be afraid for the terror by night, nor for the arrow that flieth by day. A thousand shall fall at thy side, and ten thousand at thy right hand; but it shall not come nigh thee." Psalm xci. 5.

The whole of this mystical psalm is wrested to signify something in favour of the most profane of all profane things, and to second the interested views of this or that earthly potentate. Both parties find such passages in the Prophets or the Psalmist on their own side; and such interpreters of the Prophets fail not to find their admirers, their applauders, and their followers.

Such warlike sermons have we heard from the mouths of grave divines, and even of bishops. These men are, in fact, warriors; they help on the cause. Decrepit as they are in person, they fight from the pulpit the battles of the prince, who, perhaps, raised them to their eminence. Priests fight, in fact, when they set others on to fight; even Monks fight, and, in a business truly diabolical, dare to use the name and authority of Jesus Christ.

Thus two armies shall meet in the field, both bearing before them the standard of the cross, which alone might suggest to their minds, how the followers of Christ are to carry on their warfare, and to gain their victory.

From the holy sacrament itself, in which the perfect and unspeakable union of all Christians is represented, these very Christians shall march with eager haste to mutual slaughter, and make Christ himself both the spectator and instigator to a wickedness, no less against nature, than against the spirit of Christianity. For where, indeed, is the kingdom of the devil, if not in a state of war? Why do we drag Christ thither, who might, much more consistently with his doctrine, be present in a brothel, than in the field of battle?

St. Paul expresses his indignation, that there should be even a hostile controversy or dispute among Christians; he rather disapproves even litigation before a judge and jury. What would he have said, if he had seen us waging war all over the world; waging war, on the most trifling causes, with more ferocity than any of the heathens, with more cruelty than any savages; led on, exhorted, assisted by those who represent a pontiff professing to be pacific, and to cement all Christendom under his influence; and who salute the people committed to their charge with the phrase, "PEACE BE UNTO YOU!"

I am well aware what a clamour those persons will raise against me who reap a harvest from public calamity. "We engage in war," they always say, " with reluctance, provoked by the aggression and the injuries of the enemy. We are only prosecuting our own rights. Whatever evil attends war, let those be responsible for it who furnished the occasion of this war, a war to us just and necessary."

But if they would hold their vociferous tongues a little while, I would show, in a proper place, the futility of their pretences, and take off the varnish with which they endeavour to disguise their mischievous iniquity.

As I just now drew the portrait of man and the picture of war, and compared one with the other, that is, compared an animal the mildest in his nature, with an institution of the most barbarous kind; and as I did this, that war might appear, on the contrast, in its own black colours; so now it is my intention to compare war with peace, to compare a state most pregnant with misery, and most wicked in its origin, with a state profuse of blessings, and contributing, in the highest degree, to the happiness of human nature; it will then appear to be downright insanity to go in search of war with so much disturbance, so much labour, so great profusion of blood and treasure, and at such a hazard after all, when with little labour, less expense, no bloodshed, and no risk, peace might be preserved inviolate.