Libertarian Class Analysis: An Historical Survey

[Created: 1 Sept. 2020]

[Updated: January 1, 2024 ] |

Introduction (to the website draft)

This monograph is a continuation of a project I have been working on for many years. Some earlier products of this activity include:

- a paper I gave at the Libertarian Scholars Conference: “Plunderers, Parasites, and Plutocrats: Some Reflections on the Rise and Fall and Rise and Fall of Classical Liberal Class Analysis.” Paper given at the Libertarian Scholars Conference, The Kings College, NYC, 20 Oct. 2018. davidmhart.com/liberty/Papers/Plunderers/DMH-PPP-Oct2018.html

- an anthology of texts which I co-edited: Social Class and State Power: Exploring an Alternative Radical Tradition, ed. David M. Hart, Gary Chartier, Ross Miller Kenyon, and Roderick T. Long (Palgrave Macmillan, 2018).

- a much more comprehensive collection of texts at this website: "Plunderers, Parasites, and Plutocrats: An Anthology of Classical Liberal Writing on Class Analysis from Boétie to Buchanan." davidmhart.com/liberty/ClassAnalysis/Anthology/ToC.html

- The OLL Reader: An Anthology of Key Texts http://oll.libertyfund.org/pages/oll-reader with

- a Section on the Ruling Class and the State https://oll.libertyfund.org/pages/oll-reader#part11

- and a new separate expanded section (2018) https://oll.libertyfund.org/pages/ruling-class-anthology

- a "Liberty Matters" discussion on the Online Library of Liberty website: David M. Hart, “Classical Liberalism and the Problem of Class” (Nov. 2016), “Liberty Matters” online discussion forum, the Online Library of Liberty http://oll.libertyfund.org/pages/lm-class

- plus numerous shorter papers and glossaries on Frédéric Bastiat’s theory of class, such as this: "Bastiat’s Theory of Class: The Plunderers vs. the Plundered" (May, 2016). An introduction to a bilingual anthology of Bastiat’s writings on class and exploitation. http://davidmhart.com/liberty/FrenchClassicalLiberals/Bastiat/ClassAnthology/index.html

The approach I have taken is to show, firstly the persistence of thinking about class by proto-liberals, classical liberals (CL), radical individualists, and modern day libertarians over several centuries. I believe such thinking is a core component of the broader CL tradition which has for too long been downplayed or outright ignored. Secondly, to let these thinkers speak in their own words I have quoted the original language alongside my own translation in most cases. This is also to demonstrate the considerable diversity of terms used to describe the class of the exploited and the exploited and what the former does to the latter. Thus I precede each section on a particular thinker with a list of the terms and language they used in their theory of class. This diversity of language is both a plus and a minus for the CL tradition - a plus because it shows the creativity of these thinkers in coming up with often hard-hitting and amusing epithets (often referring to some predatory animal!); and a minus because it meant that to a large degree these CLs did not speak with a common voice in making their case against the exploitation of one class of people by another.

I have left some sections unfinished as the monograph was already getting quite long at 50K words. There are place markers showing what I plan in order to fill in the gaps. In addition, many of the quotes (some bilingual parallel text) were removed for reasons of space as the original version of this paper was written for another purpose. I plan to restore them later.

Table of Contents

- Opening Quote

- Introduction: Two Competing Traditions of thinking about Class

- The Two Traditions

- Marx on Class

- CLs on Class under Socialism

- The CL "Family"

- Some Common Theoretical Aspects of Classical Liberal Class Analysis

- The Central Role played by Organised Coercion

- The Shared Structural Framework for CLCA

- The Diversity of Terminology about Class

- The Rulers vs. the Ruled

- The Unproductive vs. the Productive

- The Evolution of Class Society

- Polemical Name Calling vs. the scientific Naming of Things

- The End of Class Rule?

- The History of CLCA (I): Some Different Perspectives on Class

- Introduction

- The View from Below

- Slaves vs. Slave-owners

- Tax-payers vs Tax-receivers/consumers

- The "Industrious Classes"

- The View from Above (to add)

- Ruling Elites, Despots, Tyrants, and Aristocrats

- Thomas Gordon on Roman despots and tyrants

- Pareto on the "circulation of elites"

- "Power Elite" analysis

- Functionaries, Place-Seekers, and Jobbery

- Hippolyte Taine and Alexis de Tocqueville

- Ruling Elites, Despots, Tyrants, and Aristocrats

- Some Other Perspectives (to add)

- The Graphical Depiction of Class

- Interventionism and Bureaucracy

- The Fascist State

- The History of CLCA (II) - Before WW2

- Introduction

- The Pre-history of CLCA

- Introduction

- Étienne de La Boétie (1530–1563)

- Levellers Richard Overton (1631–1664) and William Walwyn (1600–1681)

- 18th Century Commonwealthmen: John Trenchard (1662–1723) and Thomas Gordon (1692–1750)

- The Enlightenment

- Introduction

- Adam Smith (1723–1790)

- Adam Ferguson (1723–1797)

- Turgot (1727–1781)

- John Millar (1735–1801)

- Radical Individualists and Republicans (to add)

- English Radicals and Republicans

- American Radicals and Republicans

- The Philosophic Radicals and the Benthamites

- William Cobbett (1763–1835)

- John Wade (1788–1875)

- Jeremey Bentham (1748–1832)

- James Mill (1773–1836)

- English and American Radicals and Republicans (to do)

- The Classical Political Economists: The English School

- Introduction

- John Stuart Mill (1806–1873)

- Richard Cobden (1804–1869)

- The French Political Economists and the Paris School

- Introduction

- Jean-Baptiste Say (1767–1832)

- Benjamin Constant (1767–1830)

- Charles Comte (1782–1837), Charles Dunoyer (1786–1862), and Augustin Thierry (1795–1856)

- Frédéric Bastiat (1801–1850)

- Ambroise Clément (1805–86)

- Gustave de Molinari (1819–1912)

- Some Others of Note

- The Sociological School

- Introduction

- Herbert Spencer (1820–1903)

- Gustave de Molinari (1819–1912)

- William Graham Sumner (1840–1910)

- Vilfredo Pareto (1848–1923)

- Other Authors of Note

- The History of CLCA (III) - The Post-WW2 Renaissance of CLCA

- Ludwig von Mises, Murray N. Rothbard, and the Circle Bastiat

- Post-Circle Bastiat - the Libertarian Scholars Conferences

- Other Works on CLCA by CLs and Libertarians

- Robert Higgs (1944-)

- Roy A. Childs, Jr. (1949–1992)

- David Osterfeld (1949–1993)

- Hans-Hermann Hoppe (1949-)

- Roderick T. Long (1964-)

- Gary Chartier (1966-)

- Jayme S. Lemke

- Other Approaches similar to CLCA

- Public Choice and Rent-Seeking

- Rational Choice and Predatory Rulers

- Mancur Olson and State Banditry

- Angelo Codevilla on the Ruling Class vs. the Country Class

- Power Elite Theorists (to do)

- Marxists who are "Bringing the State Back In"

- Conclusion (to do)

- Areas of Dispute and Disagreement (to do)

- Bibliography

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Endnotes

Opening Quote

(M)en placed in society ... are divided into two classes, Ceux qui pillent,—et Ceux qui sont pillés (those who pillage and those who are pillaged); and we must consider with some care what this division, the correctness of which has not been disputed, implies.

The first class, Ceux qui pillent, are the small number. They are the ruling Few. The second class, Ceux qui sont pillés, are the great number. They are the subject Many.

James Mill, "The State of the Nation,” The London Review, (1835). [1]

Introduction: Two Competing Traditions of thinking about Class

The Two Traditions

The classical liberal tradition (CLT) has a long history of thinking about class analysis (CA) which goes back at least to the English proto-liberals known as the Levellers in the 1640s, [2] but this tradition is either not well known or has been dismissed because people have associated CA with the left, in particular with Marxism. [3]

Marx on Class

This older CL tradition of thinking about class predates Karl Marx (1818-1883) and Marxism and in fact partially inspired him in his own thinking about it during the 1840s and 1850s. [4] He acknowledged his intellectual debt in a letter to Weydemeyer in 1852: [5]

Now as for myself, I do not claim to have discovered either the existence of classes in modern society or the struggle between them. Long before me, bourgeois historians had described the historical development of this struggle between the classes, as had bourgeois economists their economic anatomy. My own contribution was 1. to show that the existence of classesis merely bound up with certain historical phases in the development of production; 2. that the class struggle necessarily leads to the dictatorship of the proletariat; 3. that this dictatorship itself constitutes no more than a transition to the abolition of all classesand to a classless society.

What Marx did was to take the “bourgeois” CL historians’ and economists’ idea of class, which was based upon the idea that access to and use of political power was the defining characteristic of classes, and replaced it with the idea that it was the payment of wages (in particular the withholding by the “capitalist class” of the “surplus value” created by the “working class” but which they did not receive in their wages and which the capitalists retained as “profit”) which was the determining factor. Thus, in Marx’s view the exploitation which lay at the heart of his theory of class was essentially economic in nature and was inherent in the free market system in which there was wage labour and profits. [6] On the other hand, the CL view of exploitation which lay at the centre of their theory of class was essentially political in nature, where those who had access to the coercive power of the state exploited those who did not by means of taxation, regulation of the economy, and the granting of monopolies and other privileges to certain favored groups.

It should be noted that Marx probably recognized the dead end his notion of class led to as he was unable to finish the chapter on class he had planned for Das Kapital. On the concluding page of Das Kapital, volume 3, posthumously edited and published by Engels in 1894, Marx is grappling with his problematic theory of class and breaks off in mid-section. He begins by talking about “die drei grossen gesellschaftlichen Klassen” (the three great classes of modern society”, namely “(die) Lohnarbeiter, Kapitalisten, Grundeigenthümer” (wage earners, the capitalists, and the landowners) and then asks himself the key question “what constitutes a class?” When he realizes that two other important groups who are part of the system and who provide services (“Aerzte und Beamte” (doctors and office workers (or civil servants)) cannot be fitted into his theory of class he breaks off at this point. Apparently he was unable to reconcile the contradictions of his “economic theory of class” with his growing realization that providers of “services” were productive but did not involve the exploitation by wages paid for physical labour. [7]

Marx’s theory of class (and the socialists who followed him) stands or falls on his labour theory of value and his understanding of the nature of and the role played by the payment of wages and the making of profit in a free market system. Since his thinking on both these matters is deeply flawed and incorrect his theory of class must also be rejected. However, Marx was not always consistent in his use of class to analyse history and current events. When he wrote as a journalist, such as in The 18th Brumaire of Louis Napoleon (1852), [8] he reverted to a more CLCA “political” approach in his discussion of the power struggles which brought Louis Napoléon to power, but when he wrote as an economist in Das Capital (1859) and elsewhere he abandoned CLCA and used a more “Marxist” Ricardian economic approach with all the theoretical problems this entailed. I would argue that many historians working today from a Marxist perspective also make the same mistake as Marx did when it comes to applying class analysis to particular societies - they sometimes revert to the CL political notion of class when they explore who has power and how its is wielded (which makes their work often useful to CLs), and abandon to some degree the cruder and problematical Marxist notions about wage labour and profits.

The intellectual errors which Marx introduced into his version of class theory would be further exposed during the 20th century when Marxist and socialist states were established following the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 and the emergence of welfare states in the West following the Second World War. The emergence of a new exploiting ruling class of intellectuals, party bosses, factory managers, trade union officials, and military elites should have been impossible under socialism according to Marxist class theory, as after “the revolution” wage labour and profits would be abolished and thus society would become completely “classless” as a result.

CLs on Class under Socialism

On the other hand, according to CLCA it was inevitable that exploitation and classes would also exist in a socialist society (what in another context Bastiat called “the functionary class” and Tocqueville called “the place-seeking class” which would form the heart of a new kind of socialism known as “bureaucratic” or “state socialism”). [9] This was in fact predicted by a number of CLs in the late 19th century, such as Yves Guyot (1843-1928), [10] Gustave de Molinari (1819-1912), Paul Leroy Beaulieu (1843-1916), [11] and Ludwig Bamberger (1823-1899) in France; [12] Thomas Mackay (1849-1912), [13] Herbert Spencer (1820-1903), [14] and Auberon Herbert (1838-1906) [15] in England; Eugen Richter (1838-1906) [16] in Germany, and Charles Fairfield and J.W. Fortescue in Australia, [17] who witnessed the growth of socialist movements and the interventionist policies they inspired before WW1. These CLs argued that so long as there is a state with the power to coerce and groups who wish to use that power to achieve their political and economic goals, there will inevitably emerge a class of rulers and administrators and groups of potential beneficiaries who will exploit the ordinary working and tax-paying public. By 1884 both Leroy-Beaulieu in France and Herbert Spencer in England were warning that a “new class” of government officials and intellectuals (Leroy-Beaulieu, Collectivism, pp. 316 ff.) would take advantage of the socialist state to pursue their own interests and who would run the “collectivist régime” and thereby create “the despotism of a graduated and centralized officialism” (Spencer, “The Coming Slavery,” p. 64.) where the “small class” of “the regulators” would rule over the class of “those regulated” (Spencer, “From Freedom to Bondage,” p. 23).

Classical liberal class theorists working in the 19th and early 20th centuries would not have been at all surprised by the appearance of new and even more brutal forms of class society in Russia, China, Cuba, or Venezuela. In fact, they would have expected it as Molinari did in his uncannily accurate predictions (made in 1901) about the growth of the state in the coming century, [18] and the German politician Eugen Richter in his dystopian novel about a socialist future A Picture of the Social Democratic Future written in 1891.

The CL “Family”

The intellectual tradition we will discuss in this paper is not a rigid or monolithic one, but rather a loosely connected “family” of thinkers, activists, and politicians who were separated in time but who shared a number of liberal values (listed above) and a certain view of the state and how it functioned.

This family of thinkers includes traditional classical liberals like Adam Smith (1723-1790), Richard Cobden (1804-1865), and Frédéric Bastiat (1801-1850); radical individualists like Thomas Paine (1737-1809),William Godwin (1756-1836), Lysander Spooner (1808-1887), and Benjamin Tucker (1854-1939); Classical and Austrian School economists like James Mill (1773-1836), Vilfredo Pareto (1848-1923), and Ludwig von Mises (1881-1973); as well as other types of libertarians, both “Left” and “Right,” who emerged in the 1970s like Murray Rothbard (1926-1995) and Leonard Liggio (1933-2014).

The heyday of classical liberal class analysis (CLCA) not surprisingly coincided with the heyday of CL thinking and political activity during the 150 years between 1750 and 1900 (the Anglo/Scottish and French Enlightenment, the American and French Revolutions, the liberal reforms of the 19th century including the 1848 Revolutions) and petered out as the CLT itself petered out in the decades leading up to the First World War. It will be argued below that during this period of “classical” liberalism we can identify five different groups of CLs (or proto-CLs) who developed theories of class which had a strong common element which they shared, namely that some people/groups used the power of the state in an organised manner / systematic manner for their own benefit at the expense of ordinary consumers and taxpayers.

Later, both CL and CLCA went into a deep sleep during the first half of the 20th century before enjoying a renaissance in the post-Second World War period when a new, sixth, and re-invigorated group of thinkers emerged under the aegis of Murray Rothbard (1926-1995) and his Circle Bastiat in NYC which built upon what had gone before but incorporated a number of new insights drawn from the Austrian school of economics, inter-war American individualist thinking (such as Albert J. Nock), late 20th century libertarian political thought (including the work of Ayn Rand (1905-1982)), and aspects of New Left historiography (Gabriel Kolko and William Appleman Williams).

Some Common Theoretical Aspects of Classical Liberal Class Analysis

The Central Role played by Organised Coercion

One can define “ class” in any way one likes, such as the “class of red-haired people”, or by gender, race, or social position (“the wealthy”, “the 1%”) or occupation (wage earners, factory owners). What makes one’s definition of class more or less useful in social analysis is to pick some feature which is essential to explaining accurately how the economy or the political system works and to use this criterion to explain what one is observing.

What makes CLCA different from other approaches is the central role given to the exercise of force/coercion by the state in determining who belongs to what class. According to CLs there are two mutually exclusive ways in which wealth can be acquired, either by voluntary means such as trade, exchange, or gifting; or by means of force and coercion such as taxation, coerced labour (serfdom and slavery), monopoly, and other government granted privileges. This notion was given its classic formulation by the German sociologist Franz Oppenheimer (1864-1943) in 1907 who distinguished between “das ökonomische Mittel” (the economic means) and “das politische Mittel” (the political means) of acquiring wealth, with the state being defined as “die Organisation des politischen Mittels” (the organization of the political means) of acquiring wealth. [19]

According to the CL theory of CA the use (or threat) of violence / coercion is the determining feature of membership in a “class”: there are those who use the power of the state and the coercion it controls to benefit themselves at the expense of those who are the victims or subject to the use of that force. As a consequence, it is not one’s economic occupation, social position, or the amount of wealth one has per se which determines one’s “class” in this conception, but how one acquired that occupation, position, and wealth, either by voluntary exchange and cooperation with others (the market) or by taking “other peoples’ stuff” by the use of state power and coercion (taxation, regulations, privileges).

Sometimes this “taking” is done by individuals (such as thieves and robbers and pirates), what Frédéric Bastiat (1801-1850) termed “la spoliation extra-légale” (extra-legal plunder, i.e. plunder which is done outside and in opposition to the law) and sometimes by groups of individuals organised for that very purpose, or what Bastiat termed “la spoliation légale” (legal plunder, i.e. the taking of other peoples’ property under the aegis and protection of the state. [20] CLs argued that when this legal and state-sanctioned “taking” becomes institutionalized or systematized over time the people who are involved in this activity become a “class” of exploiters who have their own interests, way of thinking, and patterns of behaviour. This persistence over time and its bureaucratic institutionalization turns what might in the short term be regarded as just “vested interests” seeking political rents (the Public Choice view) into what is better referred to as a more permanent institution or “class”, perhaps even a “ruling class.”

The Shared Structural Framework for CLCA

In spite of the diversity of individuals involved, the span of time they covered, and the range of terminology they used (see below), there are some common elements to CLCA. The common thread is that a small group of people, usually organized in some way in a state or a church (sometimes summarized as “throne” and “altar”), used force or threats of force to take “other people’s stuff” without their permission, or to force them to do (like buy goods and services from some legally privileged group of suppliers) or not do certain things (like attend the church of their choice, or to engage in whatever trade or profession they liked). This can be broken down into three main components.

Firstly, that societies can be divided into two antagonistic groups, which in its simplest form can be described as “the people” (the ruled) vs. their “rulers”, with the defining feature being who has access to political (i.e. coercive) power within a given society. Furthermore, that one of these groups, “the ruling few,” “exploits” or “plunders” the other by taking the latter’s property without its consent or by passing laws which benefit the former at the expense of the latter, thus creating a “system” or “machine” of plunder and exploitation, or in other words “a state.”

Secondly, that one of these groups, “the ruling few” is not “productive” (i.e. it is “unproductive” or “sterile”) and “exploits” the other group (which is “productive”) by taking the latter’s property without their consent or by passing laws which benefit the former at the expense of the latter. This distinction between “productive” and “unproductive” activity changed over time as economic systems and technology changed and as theoretical notions of what “productive” meant changed. For example, in the late 18th century the French Physiocrats (like François Quesnay (1694-1774) and Turgot (1727-1781)) believed that only agriculture was a productive economic activity and that other economic activities merely moved around or changed the external form of what had already been produced on the land. They thus believed that taxes on agriculture and agricultural land was the basis for any exploitation or appropriation of wealth. This idea was changed later by economic thinkers like Adam Smith, who believed manufacturing was just as productive an activity as agriculture, then in the early 19th century by Jean-Baptiste Say (1767-1832) who argued that the entrepreneur also engaged in highly productive activities, and by Bastiat in the mid-19th century that all “services” were as well. As the definition of what was productive activity changed, so did the ways in which an exploiting class might take advantage of these activities with added taxes on industry and regulations on entrepreneurial activity, thereby gradually changing the structure and functions of the state.

And thirdly, although this was a view not shared by all CLs, that societies evolved over time as technology changed and trade and production increased, resulting in new kinds of class rule and exploitation. This evolution through distinct stages was usually optimistically seen as ultimately heading towards a society with greater political and economic freedom and the eventual abolition of class rule. The most elaborate and detailed works of this kind of historical sociology of the interplay between the rise of markets, the state, and class appeared independently of each other in the late 19th century by Gustave de Molinari in France and Herbert Spencer in England.

The Diversity of Terminology about Class

However, in spite of sharing these three ideas about class and class society CLs developed a bewildering array of terms to describe them which is a major reason I believe why CLCA has not received the recognition it deserves. Over the centuries CLs were not able to settle upon an agreed terminology with which to describe the nature of class relations and the exploitation which resulted from those relations, and so their ideas were thus not properly understood or recognized.

Unlike the Marxists and socialists who were able very early on to settle upon the central idea of wage labour as the mechanism by which the “capitalist class” (the bourgeoisie) exploited “the working class” (the proletariat) by not giving them the “full value” of their labour, the CLs, although they may have agreed on the central role played by the state in using the coercion/violence at its disposal to grant privileges to some at the expense of others, did not use a common terminology to describe these groups, preferring to use terms which were unique to their particular historical, political, and economic circumstances. Thus, CLs literally reinvented the language of CA every generation or so in order to describe the unique historical moment in which they lived.

We can see the diversity of language and terminology when we examine how the three common features of CLCA mentioned above were described at different times in different historical circumstances.

The Rulers vs. the Ruled

The latter group, “the rulers”, has been variously termed:

- tyrants and despots

- “the single tyrant” and his “favourites” and “petty chiefs”, “a single clique” (La Boétie)

- “the spirit of despotism”, “petty despots,” “confederated despots”, “self-acting tools of despotism” (Knox)

- “a gradation of tyrants" (Trenchard and Gordon)

- oligarchs and aristocrats

- “ministerial oligarchy” (Knox)

- “clan of oligarchs”, “devouring clan of Oligarchs”, the “Ins” and the “Outs”, “the favoured caste” (Wade)

- “the oligarchy” (Trenchard and Gordon, Knox, Wade, Bastiat, Cobden).

- “oligarchies of the Sword, of the Purse, and of the Intellect”, “the Ring, the Few, the Boss” (Bryce)

- “paper money aristocracy”, “the phalanx of placemen” (Leggett)

- ruling elites

- “the ruling few” (Bentham, James Mill, Spencer)

- “the sinister interests”, “the ruling one; the sub-ruling few” (Bentham, Mill)

- factions and parties

- a faction (Trenchard and Gordon, Madison, Tocqueville); the “violence of faction” (Smith), “the despotism of factions” (Tocqueville)

- the machinery and system of government

- “the spirit of system” (Smith)

- the “system of corruption,” “the monied interest,” “the Thing” (Cobbett)

- “this power-stealing system”, “the state engines”, “rulers in chief” (Bentham)

- “the great law factory” (Bastiat); “the great lawmaking machine” (Herbert)

- other terms

- the system of “legal plunder” (Bastiat)

- “the voting class” (Bastiat)

- the “governed” and “those who govern” (Tocqueville)

- “the Slave Power” (Cairnes)

- “the ruling agency” (Spencer)

- “great bands of robbers and murderers”, “the robber class, the slave holding class, the law-making class” (Spooner)

- “political bandits” (Taine)

- “plutocracy” (Sumner)

- “those who rule and are ruled”, “the conquering race and the conquered race” (Herbert)

The Unproductive vs. the Productive

The “unproductive” and the “productive” groups / classes have been variously termed:

- eating and consuming wealth

- “caterpillars” (Richard Overton)

- “court parasites” (Trenchard and Gordon)

- “tax-eaters” (Cobbett)

- “tax-payers” vs “tax consumers” (Calhoun)

- “the budget eaters” (“la classe budgétivore” - Molinari)

- “swarms of Jacobin locusts, this cloud of destructive insects”, “the plucked pigeon” (Taine)

- “shearing the sheep” (Pareto)

- unproductive bureaucrats

- the “productive classes” vs. “functionaries” (Say)

- “placemen” and “pensioners” (Paine)

- “the place-seeking class” (Dunoyer, Tocqueville, Molinari); “Place hunters” (Tocqueville)

- “the functionary class” (Bastiat, Clément)

- “jobbery” (Sumner)

- “the bureaucratic caste” (Herbert)

- “a class of officials and a class of drudges” (Guyot)

- pillagers and conquerors

- “ce qui pillent” (those who pillage) vs “ce qui sont pillés” (those who are pillaged) (James Mill)

- “the conquerors” vs. “the conquered” (Thierry, Spencer, Oppenheimer, Nock),

- “the plundering class” vs. “the plundered class” (Bastiat, Taine)

- other general terms

- “the producers” vs. “the non-producers” (Turgot, Say).

- “the middling and industrious orders” (Wade)

- “the industrious class” (Say, Thierry, Bastiat, Molinari)

- “the militant type of society” vs. the “Industrial type off society” (Spencer)

- “the Forgotten Man” (Sumner)

- “the economic vs. political means of acquiring wealth” (Oppenheimer)

The Evolution of Class Society

These stages have been described variously as:

- evolution through four stages of communal property, slavery, feudalism, commerce (Ferguson, Millar, Smith, Turgot)

- evolution through two stages: ancient warrior and slave-based society vs. modern commercial society (Constant)

- evolution through five stages of communal property, slavery, feudalism, commerce and industrial society, with a new “industrious class” (Comte, Dunoyer)

- conquest, slavery, feudalism, then Free Cities, Communes, and the Third Estate (Thierry)

- war, slavery, theocratic plunder, monopoly, bureaucratic plunder, free trade (Bastiat)

- militant vs industrial societies (Spencer)

- the era of tribal community and slavery, the era of small scale industry and monopolies, and the era of large scale industry and complete competition (Molinari)

- the feudal state, the maritime state, the industrial state, the constitutional state (Oppenheimer).

Polemical Name Calling vs. the scientific Naming of Things

Like the Marxist theory of CA the CL theory has both a polemical (morally laden) and a “scientific” (or value-free) dimension. [21] Thus the reader has to be aware of when a CL is using the language of class in a polemical and political way in the heat of the moment (as in the campaign to end tariffs in England and France in the 1840s) and when they are using it in a scientific and more value-free way in order to develop a better theoretical understanding of how societies operated.

The moral dimension comes from the fact that CLs consider that the use of violence to violate another person’s right to life, liberty, and property is morally wrong and hence, any group or “class” of people who organise themselves in order to violate the rights of others by means such as taxation, forced labour, conscription, banning or restricting certain occupations, the imposition of tariffs, and so on, should be condemned and resisted. Throughout the history of the CLT there has been strong language used to criticize such groups and it has often been an effective weapon in the political struggle for liberal reforms, such as ending rule by absolute monarchs, opposing slavery, resisting the imposition of “taxation without representation,” and opposing tariffs on imported food.

For example, CLs like Richard Cobden and Frédéric Bastiat both used the language of class polemically to describe their opponents in the campaigns for free trade against the land-owning class in Britain as the “oligarchy” and the “borough-mongers” and in France as “la classe électorale” (the voting class) and “la classe spoliatrice” (the plundering class) respectively. The politician Cobden did not attempt to incorporate this terminology and this manner of thinking into any broader social theory, but class theory was implicit in the way he thought about British society.

On the other hand, this should be contrasted with his contemporary and counterpart in France, Frédéric Bastiat, who used much the same class language (some of it inspired by Cobden and the Anti-Corn Law League) but also incorporated it into a sophisticated and well-thought out theory of class and history as his plans to write A History of Plunder clearly indicate. [22]

Other CLs who integrated their notions of class into a broader theoretical framework include Herbert Spencer and Gustave de Molinari later in the 19th century (mentioned above). Another important figure is the English Radical and journalist John Wade (1788-1875) who, although not a theorist, wrote the most detailed historical study of the class structure of English society in the 1820s and 1830s, Extraordinary Black Book (1820-23, 1832-35) which went through many editions and is a model of its type.

Some examples of the moral outrage felt by CLs to these perceived injustices of class rule include the following value-laden terms:

- the Levellers’ “caterpillars” (1640s)

- Paine’s “banditti” (1776)

- Bentham’s and James Mill’s “the sinister interests” (1820s and 1830s)

- Wade’s “this devouring clan of Oligarchs” (1830s)

- Cobden’s and Bastiat’s “oligarchy” (1840s)

- Bastiat’s “plunderers” and “parasites” (1840s)

- American abolitionists’ “man-stealers” (1850s)

- Molinari’s “budget eaters” (1850s)

The “scientific” (or value-free) dimension of CLCA comes from the fact that the distinction CLs have made between the two different means of acquiring wealth is a useful mechanism for explaining how societies and economies work, why certain policies are pursued and not others, what the sources of conflict are in any given society, and what the outcome of these conflicts or “struggles” (to use a Marxist term) might be/ have been, [23] without making any value judgement about the rightness or wrongness of acting in this way.

Some examples of the more value-free terminology used by CLs include the following:

- Calhoun’s “tax-consumers” vs. “tax-payers” (1840s)

- Spencer’s the “industrial” and the “militant” class, or “the regulators” vs. “those who are regulated” ((late 19thC)

- Molinari’s idea of the transition from small-scale production to large- scale, the movement from political tutelage to individual self-government, and from limited competition to universal competition

- Oppenheimer’s “the political vs economic means of acquiring wealth” (1912)

The End of Class Rule?

In the early decades of the 19th century CLs like the Benthamites around James Mill and the Philosophic Radicals it was assumed, perhaps naively, that once the landed and financial elites which controlled Britain had been dispossessed of their political power by democratic reform (as in the First Reform Act of 1832) and replaced by “right thinking” Benthamite reformers, class rule would come to an end. This was a view shared by Marxists who thought that once the capitalists had been overthrown and replaced by the “dictatorship of the proletariat” class rule would automatically and inevitably come to an end. The same can be said today about supporters of the modern welfare state (social democrats) who would be shocked to be told that it too is a class-based state where a class of bureaucratic administrators and a dependent class of welfare recipients live off funds taken from the tax-payers.

Although the main CL theorists on the evolution of class society, Molinari and Spencer, probably started out believing that class rule could be drastically reduced or even eliminated as free markets and international free trade spread and as people became used to the benefits of the secure ownership of property, as the century wore on they came to have their doubts that this situation would arise in the near future, or perhaps ever. The temptations of what in the late 20th century would be called “rent-seeking” in democratic societies was too great for politicians to resist (whether socialist or CL) and it was likely that class rule would return even if it were reduced as they hoped it would be. Molinari was the more pessimistic of the two and believed (writing at the turn of the century) that the coming 20th century would see decades of war, socialism, and economic depression before a revival of CL ideas would take place after two or three generations in the wilderness.

The History of CLCA (I): Some Different Perspectives on Class

Introduction

The richness and diversity of CLCA can be simplified somewhat by examining a number of thematic threads which weave their way through the CL tradition. These threads approach the subject of class from a number of different perspectives:

- the first from “below” which looks at coerced labour in the form of slavery and serfdom (chattel or “labour slavery”), the payment of taxes (or “tax slavery”) by ordinary working people, and the “Third Estate” and the “industrious classes” who were emerging in the “free cities” of the medieval period

- the second from “above” which could be divided into two separate sub-divisions, the “ruling few”, a tyrant, a despot, and the aristocracy at the very top; and that of the “minor despots”, the bureaucrats, “functionaries”, and administrators who carried out the will / commands of the elite.

- and a third perspective which looked at the “big picture” of the broad historical sweep of the evolution of the state and its rulers, market institutions and the “productive classes” which made this possible, and the rivalrous relationship between the two groups.

The View from Below

Slaves vs. Slave-owners

Early in the emergence of CLCA there were two activities/institutions upon which CL theorists focussed and upon which they based their view of class, namely the institution of slavery and the payment of taxes. The institution of slavery and other forms of coerced labour (such as serfdom) created a clear separation between the slaves who did the labour under coercion and the slave-owners who benefited from this labour. This provided CLs with the archetypal or paradigmatic form of an organised system of class and class exploitation. The analysis of slavery as a system of class rule formed the basis of Charles Comte’s (1782-1837) and Charles Dunoyer’s (1786-1862) works in the 1810s to 1830s [24] which became very influential among mid- and late-19th century French liberals (such as Bastiat and Molinari) and later among Rothbard’s circle in the 1950s (Raico and Liggio).

For example, Comte devoted a large section of his major work Traité de législation (1827) [25] to the economics of slave labour and the relationship between slave owners and slaves, in which he developed an extensive language of class which would become very influential in French CL circles. He talked specifically about “la classe des maîtres” (the class of masters or slave owners) and “la classe des esclaves” (the class of slaves) but also generalized this class relationship to include broader categories such as “une classe d’oppresseurs et une classe d’opprimés” (a class of oppressors and a class of the oppressed), “les classes privilégiées” and “les classes non privilégiées” (the privileged classes and the unprivileged classes), and most importantly “la classe industrieuse” (the industrious or wealth producing class) which lay at the heart of their understanding of class in modern society. (See below for details.) The key insight was the idea that all societies were divided into two antagonistic groups, those who worked and produced the wealth, and those who did not work or produce but who lived off those who did by enslaving them, enserfing them, or taxing them. Comte’s and Dunoyer’s work on slavery provided an historical case study and a theoretical model to describe the other systems of class exploitation which emerged later after slavery, such as serfdom, then what they called the “system of privilege” (in other words mercantilism), and the political system of “place-seeking” in which individuals competed to get a limited number of tax-payer funded jobs in the government bureaucracies. [26]

Not only did they study the historical forms which organised slavery and its later variants took in ancient Rome, Europe, and the Americas, but “slavery” also became a metaphor for exploitation by the state in general even after formal slavery (and serfdom) had been abolished (usually as a result of agitation for reform by CLs). In their view, all forms of coerced labour were on the cusp of being replaced in the early 19th century with a new “industrious class” (“les industriels”) which was beginning to emerge out of the ashes of the slave and serf systems and which consisted of all individuals who produced wealth (whether goods or services) for voluntary sale and exchange on the free market.

Some members of the Classical School of Economics also directed their attention to the economics of slave labour in order to show its economic inefficiency and to identify the classes which benefited from this. Jean-Baptiste Say was particularly important in his Treatise on Political Economy (1803, 1814, 1817) in which he made the standard criticism concerning the economic inefficiency of slave labour (the slaves lacked incentives to work harder and the slave owners lacked incentives to innovate with other methods of production), and the fact that without subsidies from the government for policing the slave system (keeping the slaves from rising up in rebellion) and tariffs on foreign sugar and guaranteed markets in the metropole, the class of slave owners were predicted to go bankrupt quite quickly. [27]

Other economists who should be mentioned in this regard were the Russian economist Heinrich Friedrich von Storch (1766-1835) who wrote extensively on the economics and class system of serfdom in the Russian Empire in Cours d’économie politique (1st ed. 1815, 1823), [28] the Swiss economist Simonde de Sismondi (1773-1842) in Études sur l’économie politique (1837), [29] the Belgian-French economist Gustave de Molinari (1819-1912) in many works [30] who developed Comte’s and Dunoyer’s theory of class in many important new directions, and the Irish economist John Elliott Cairnes (1823-1875) in The Slave Power: Its Character, Career, and Probable Designs (1861) who devoted an entire book to describe the class system which existed in the American south on the eve of the outbreak of the Civil War. [31] Cairnes described the Southern slave owners as a “ruling class”, “a compact oligarchy,” “the ascendent class”, and the system they created as the “despotism of the wealthy few.”

In a more recent history of slavery and the American Civil War Jeffrey Hummel makes use of the insights of Comte and Dunoyer but his class analysis is more implied than explicit. One has to read his many short “Bibliographical Essays” to find this spelt out. [32]

Tax-payers vs Tax-receivers/consumers

Whereas the Marxists had their “wage slavery” the CLs had their “tax slavery”.

If chattel slavery was the quintessential form of exploitation of one class of people by another where the entire product of one’s labour was forcibly taken, then by extension CLs thought, “slavery” also existed when part of one’s labor was forcibly taken by another person, as in taxation by the state. Thus there developed in CL thought the idea that there was a group of people (a “class”) who were forced to pay taxes to the state - the “tax-payers” - who were in an antagonistic relationship with another group of people (a “class”) who were the beneficiaries of this tax money - the “tax-receivers/consumers.” The antagonism manifested itself in the resistance of the tax payers to paying taxes for “services” which may or may not have been real or wanted, and the desire of the tax receivers/consumers to maintain or increase taxes for their own benefit or the benefit of their friends and allies. The French historian Augustin Thierry (1795-1856) explored another form this resistance to taxes took where the “Free Cities” of medieval Europe (like Magdeburg) sought and got agreements with their feudal lords for tax mitigation and considerable freedom in the form of Charters for their cities and an early form of self-rule in return for more fixed payments. Thierry explained this process as one of the first and most important successes of the rise of a new class in Europe, the “Third Estate” of non-noble and non-slave individuals. [33] Gustave de Molinari also pursed this line of thought in his articles on “Cities and Towns,” “The Nobility,” and “Slavery” for the DEP (1852). [34] The persistent tax revolts which have appeared throughout history testify to this ongoing antagonism between tax-payers and tax-consumers and one should make special note of the importance of the American Revolution as possibly the most significant of these in the history of CL thought and the emergence of liberal institutions.

One of the clearest expressions of the idea of the antagonism between “tax-payers” and “tax-consumers” was put forward by the American southern politician and ironically a defender of slavery, John C. Calhoun (1782-1850) in A Disquisition on Government (1849) where he believed there was a zero sum relationship between the two classes - the gain of one had to be at the detriment of the other: [35]

The necessary result, then, of the unequal fiscal action of the government is, to divide the community into two great classes; one consisting of those who, in reality, pay the taxes, and, of course, bear exclusively the burthen of supporting the government; and the other, of those who are the recipients of their proceeds, through disbursements, and who are, in fact, supported by the government; or, in fewer words, to divide it into tax-payers and tax-consumers.

But the effect of this is to place them in antagonistic relations, in reference to the fiscal action of the government, and the entire course of policy therewith connected. For, the greater the taxes and disbursements, the greater the gain of the one and the loss of the other—and vice versa; and consequently, the more the policy of the government is calculated to increase taxes and disbursements, the more it will be favored by the one and opposed by the other.

Calhoun it should be noted had a considerable influence on Murray Rothbard who altered Calhoun’s idea slightly by changing it to the idea of “net” tax-payers and “net” tax-consumers in order to take into account the more complex situation in modern economies where tax-payers might also receive some benefits from the state (such as services like roads and sewers, or social security benefits) which necessitated a calculation of whether some groups were in the end “net” payers or receivers. (See below.)

Calhoun did not apply his idea to any detailed historical analysis of who paid the taxes and who benefited from their “disbursement”. This was true for most CLs who used the idea more in a polemical fashion, with the exception of the English radical journalist John Wade (1788-1875) in his popular and influential multi-volume Black Book of Abuses (1820) which appeared in several editions in the 1820s and 1830s as part of the Philosophic Radicals’ and Benthamite’s campaign for the reform of the British electoral system leading up to the Reform Act of 1832 which opened up the franchise to the middle class taxpayers for the first time. [36] Wade’s theory of class involved an oligarchy of special interests drawn from the established church, the military, senior judges and lawyers, privileged companies and corporations, and government bureaucrats and “functionaries” which controlled the government for their own benefit and enrichment. The Black Book of Abuses was a 500 page very detailed listing of all the tax monies extracted from “the many,” “the middling and industrious orders,” and spent on “the few,” “the usurping, devouring clan, and plundering oligarchy” which made up what he termed “the System”. There is nothing quite like it in the entire history of CLCA.

Although the French liberal aristocrat Alexis de Tocqueville (1805-1859) did not use CA expressly in his Democracy in America (1830, 1835) he did have a great interest in the ordinary American as a citizen of a democratic state and how this democracy would work in a system without an established aristocracy and which was radically decentralized and imposed very low taxes. Whether or not this new system of government would produce a new form of tyranny and how it would deal with the problem of slavery were issues which troubled him greatly. He did however turn to an examination of the bureaucratic class which ran the ancien régime in his work The Revolution and the Ancien Régime (1856).

It should be noted here that in the 1880s the American sociologist William Graham Sumner (1840-1910) wrote a series of essays about what he called “The Forgotten Man” by which he meant the average person whose taxes paid for the all the waste, political corruption, and subsidies to the “plutocrats” who benefitted most from the American system of government and the system of “jobbery” where jobs in the government bureaucracies were handed out as political favors. (See below.)

The “Industrious Classes”

In the early 19th century the term “industry” and “industrious” had the more general meaning of any activity or person engaged in that activity which produced things (later services) of value which other people wanted to buy. Later the term “industry” and “industrial” would be limited to the narrower meaning of a particular way of producing certain things in factories using machinery. Charles Comte, Charles Dunoyer, Augustin Thierry, and Benjamin Constant (1767-1830) in the late 1810s used the word in the former sense to argue that European society was entering a new stage of development where “les industriels” (the industrious classes) were on the verge of creating an entirely new form of society, “industrialism”, where all forms of slavery, coerced labour, and political privilege would be done away with along with the unproductive, parasitical classes which benefitted from that, and replaced by social, political, and economic relationships which would be based upon the voluntary exchange of goods and services produced by “the industrious classes”. Comte and Dunoyer were inspired by a revised edition of Say’s Treatise (1815) to develop this theory of “industrialism” in a new magazine Le Censeur européen (1817-19). [37]

Dunoyer in particular developed the theory of “industrialism” and the rise of the “industrial classes” in a series of books beginning with L’Industrie et la morale considérées dans leurs rapports avec la liberté (Industry and Morality considered in their Relationship with Liberty) (1825). [38] The French Revolution, according to this theory, had been the first step on the path for the industrial class to overthrow the plundering classes which had ruled Europe until then and to begin building a new society where economic privilege and regulations were removed, free markets and competition introduced for all occupations and economic activities, and the size, power, and cost of government reduced to a bare minimum, or even to nothing . There are hints of this radical anti-statism, even anarchism, in some lectures J.B. Say gave in Paris in the late 1810s, [39] and in Dunoyer’s idea about eliminating the central, national state and replacing it with locally controlled municipal governments (what he called” the municipalisation of the world”). [40] This is a theme Molinari would take up in 1849 in his idea of applying free competition to “the production of security” (i.e. police and national defense) and in his works of historical sociology written in the late 1870s and early 1880s in which he proposes that private communities created by real estate entrepreneurs might provide “public goods” to those who bought property in the community. [41] In the latter Molinari expanded in considerable detail the historical analysis of class begun by Comte and Dunoyer and updated CLCA to explain the new circumstance and the new kinds of state which were emerging in the late 19th century.

Thierry on industrialism

Augustin Thierry worked for Comte and Dunoyer editing their journal, wrote his own works on the class theory of industrialism, and would later apply it to his own interpretation of French and European history in an important pair of books. The first was Histoire de la conquête de l’Angleterre par les Normands (1825) [42] in which he argued that a common way by which one class came to dominate and plunder another was by means of conquest, and the classic example of this he thought was the Norman conquest of Saxon England in the 11th century. The second The Formation and Progress of the Tiers État (1853) was a broad ranging discussion of the rise of the “bourgeoisie” or “Tiers état” (Third Estate) after the collapse of slavery under the Roman Empire, its transformation into serfdom and peasant-based agriculture, and then the struggle of these ex-slaves and serfs to become “free citizens” of the emerging “free cities” of the medieval period, who were the original “bourgeoisie” (city dwellers).

It should also be noted that a “conquest theory” of the origin of class was also part of the thinking of the English Levellers in the 1640s. The Norman French conquerors constituted the monarchy and the aristocracy which had dominated English politics since the invasion and were the beneficiaries of the taxes and economic privileges imposed on the “Freeborn Englishmen and women” ever since. However, through a long process of struggle and resistance to the ruling class of Norman conquerors the English people had tried to preserve their liberties through the traditional Common Law and by limits imposed upon kingly power by means of Magna Carta. [43]

The View from Above (to add)

Ruling Elites, Despots, Tyrants, and Aristocrats

Thomas Gordon on Roman despots and tyrants

Pareto on the “circulation of elites”

“Power Elite” analysis

Functionaries, Place-Seekers, and Jobbery

Hippolyte Taine and Alexis de Tocqueville

Some Other Perspectives (to add)

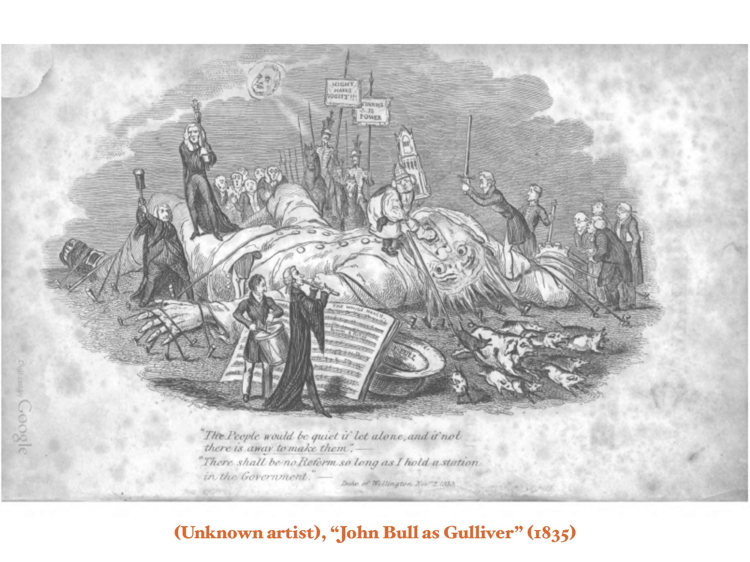

The Graphical Depiction of Class

art/posters/cartoons - John Bull, Atlas, the social pyramid

Interventionism and Bureaucracy

Mises on interventionism, the total state

Tullock on bureaucracy

The Fascist State

John T. Flynn

Mises

Charlotte Twight

The History of CLCA (II) - Before WW2

Introduction

The key period during which traditional CLCA emerged in a more coherent form was roughly the one hundred and fifty years between 1750-1900, a period which, not incidentally, coincided with the Enlightenment in Europe and North America and the liberal revolutions which accompanied this in America and France in the 18thC, and across much of Europe in 1848.

Chronologically speaking, there have been six historical periods during which different groups of thinkers contributed to the formation of CLCA. The terminology they adopted and the groups they identified as “the rulers” and “the exploiting class” varied considerably according to historical circumstances. Here I will deal with the first five which appeared before the post-WW2 modern libertarian movement.

- the Prehistory

- the Enlightenment (Anglo-Scottish and French)

- the Philosophic Radicals and the Benthamites

- other English and American Radicals and Republicans

- the Classical Political Economists (English and the Paris School)

- the Sociological School

- the post-WW2 modern libertarian movement

The Pre-history of CLCA

Introduction

The first period of thought makes up what might be termed “the Prehistory” of the tradition since we are not dealing with self-confessed “liberals” at this stage (this term would not appear until the early 19th century) but rather “proto-liberals”. Included in this group are some early modern and early 18th-century thinkers who made the rather crude distinction between “the people” and “the King (or Prince) and his Courtiers.” In this group we include the French magistrate and poet Étienne de La Boétie (1530-1563) who described society as a pyramid with tyrants and “petty chiefs” at the top and ordinary taxpayers at the bottom; the English Levellers such as Richard Overton (1631-1664) and William Walwyn (1600-1681) who thought the ruling class had been brought to England by the Norman conquerors and that contemporary elites were like so many “caterpillars” which consumed society’s wealth; and the 18th Century Commonwealthmen John Trenchard (1662-1723) and Thomas Gordon (1692-1750) who thought the British state was ruled by so many despots and tyrants.

Étienne de La Boétie (1530-1563)

The French magistrate and poet Étienne de La Boétie (1530-1563) in his Discourse of Voluntary Servitude (1549) [44] thought the Renaissance French state under Henry II (1547-59) was like a pyramid with the tyrant at the top, underneath which were his courtiers and “petty chiefs,” and below them was the mass of tax-paying citizens who paid for it all. A key question he posed was why the mass of tax-payers, since they outnumbered the small clique at the top, did not rise up and throw off their tyrants. Ideological submission and force of habit was his answer.

Some of the key terms he used to describe this situation were the following:

- a single little man (“un seul hommeau,” Bonnefon, p. 5);

- this single tyrant (“ce seul tyran” p. 9);

- a single clique (“servir à un” p. 4);

- these favourites (“ces favoris” p. 50);

- tyrants and their accomplices (“les tirans & leurs complices” p. 57);

- the tyrant vs. the few;

- the lovers of freedom (“ceux qui ont gardé la devotion à la franchise” p. 31) and the brutish mass (“le gros populas” p. 30);

- bullocks, prey, natural slaves (“les éleus, comme s’ils avaient pris des toreaus à domter, ainsi les traitent ils; les conquerans en font comme de leur proie; les successeurs pensent d’en faire ainsi que de leurs naturels esclaves.” p. 20);

- petty chiefs under the big tyrant (“& être, sous le grand tiran, tiranneaus eux-mêmes” and “que les uns ne soient que vallets, les autres chefs de l’assemblée = some being only underlings while others are chieftains of gangs” p. 47);

- a pyramid structure of power: 6 have access to the tyrant’s ear, they have 600 who profit under them, then they have 6,000 under them who are made governors of provinces and direct the state’s finances (p. 46);

- man-eaters (“ces mange-peuples” p. 57).

La Boétie thought that there were concentric circles of powerful people who surrounded the tyrant and benefited from the tax resources which flowed from the people to the centre. These sub-groups of greater or lesser tyrants and chiefs (les chefs) constituted the ruling class. The numbers he provides (the six, the six hundred, the six thousand) are figurative only but the point is still made:

| On ne le croira pas du premier coup, mais certes il eſt vray: ce ſont touſqiours quatre ou cinq qui maintiennent le tiran, quatre ou cinq qui lui tiennent tout le païs en ſeruage. Touſiours il a eſté que cinq ou fix ont eu l’oreille du tiran, & ſ’y ſont approché d’eus meſmes, ou bien ont eſté appeles par lui, pour eſtre les complices de ſes cruautes, les compaignons de ſes plaiſirs, les macquereaus de ſes voluptes, & communs aus biens de ſes pilleries. Ces ſix addreſſent ſi bien leur chef, qu’il faut, pour la ſocieté, qu’il ſoit meſchant, non pas ſeulement de ſes meſchancetes, mais ancore des leurs. Ces ſix ont ſix cent qui proufitent ſous eus, &, font de leurs ſix cent ce que les ſix font au tiran. Ces ſix cent en tiennent ſous eus ſix mille, qu’ils ont eſleué en eſtat, auſquels ils font donner ou le gouuernement des prouinces, ou le maniement des deniers, afin qu’ils tiennent la main à leur auarice & cruauté & qu’ils l’executent quand il ſera temps, & facent tant de maus d’allieurs qu’ils ne puiſſent durer , que ſoubs leur ombre, ni ſ’exempter que par leur moien des loix & de la peine. | This does not seem credible on first thought, but it is nevertheless true that there are only four or five who maintain the dictator, four or five who keep the country in bondage to him. Five or six have always had access to his ear, and have either gone to him of their own accord, or else have been summoned by him, to be accomplices in his cruelties, companions in his pleasures, panders to his lusts, and sharers in his plunders. These six manage their chief so successfully that he comes to be held accountable not only for his own misdeeds but even for theirs. The six have six hundred who profit under them, and with the six hundred they do what they have accomplished with their tyrant. The six hundred maintain under them six thousand, whom they promote in rank, upon whom they confer the government of provinces or the direction of finances, in order that they may serve as instruments of avarice and cruelty, executing orders at the proper time and working such havoc all around that they could not last except under the shadow of the six hundred, nor be exempt from law and punishment except through their influence. |

| Grande eſt la ſuitte qui vient apres cela, & qui voudra ſ’amuſer à deuider ce filet, il verra que, non pas les ſix mille, mais les cent mille, mais les millions, par cette corde, ſe tiennent au tiran, ſ’aidant d’icelle comme, en Homere, Iuppiter qui fe vante, ſ’il tire la cheſne, d’emmener vers ſoi tous les dieus. De là venoit la creue du Senat ſous Iules, l’eſtabliſſement de nouueaus eſtats, erection d’oſſices; non pas certes, à le bien prendre, reformation de la iuſtice, mais nouueaus ſouſtiens de la tirannie. En ſomme que l’on en vient là, par les faueurs ou ſoufaueurs, les guains lou reguains qu’on a auec les tirans, qu’il ſe trouue en fin quaſi autant de gens auſquels la tirannie ſemble eſtre profitable, comme de ceus à qui la liberté ſeroit aggreable,. Tout ainſi que les medecins diſent qu’en noſtre corps, ſ’il y a quelque choſe de gaſté, deſlors qu’en autre endroit, il ſ’y bouge rien, il ſe vient auſſi toſt rendre vers ceſte partie vereuſe : pareillement, deſlors qu’vn roi ſ’eſt declaré tiran, tout le mauuais, toute la lie du roiaume, ie ne dis pas vn tas de larronneaus & eſſorilles, qui ne peuuent gueres en vne republicque faire mal ne bien, mais ceus qui ſont taſches d’vne ardente ambition & d’vne notable auarice, ſ’amaſſent autour de lui & le ſouſtiennent pour auoir part au butin, & eſtre, ſous le grand tiran, tiranneaus eus meſmes. (Bonnefon, pp. 45-47.) | The consequence of all this is fatal indeed. And whoever is pleased to unwind the skein will observe that not the six thousand but a hundred thousand, and even millions, cling to the tyrant by this cord to which they are tied. According to Homer, Jupiter boasts of being able to draw to himself all the gods when he pulls a chain. Such a scheme caused the increase in the senate under Julius, the formation of new ranks, the creation of offices; not really, if properly considered, to reform justice, but to provide new supporters of despotism. In short, when the point is reached, through big favors or little ones, that large profits or small are obtained under a tyrant, there are found almost as many people to whom tyranny seems advantageous as those to whom liberty would seem desirable. Doctors declare that if, when some part of the body has gangrene a disturbance arises in another spot, it immediately flows to the troubled part. Even so, whenever a ruler makes himself a dictator, all the wicked dregs of the nation—I do not mean the pack of petty thieves and earless ruffians who, in a republic, are unimportant in evil or good—but all those who are corrupted by burning ambition or extraordinary avarice, these gather around him and support him in order to have a share in the booty and to constitute themselves petty chiefs under the big tyrant. (Kurz trans., pp. 71-73.) |

Levellers Richard Overton (1631-1664) and William Walwyn (1600-1681)

The English Levellers Richard Overton (1631-1664) and William Walwyn (1600-1681) took up a major theme of the radicals who opposed the absolutist reign of Charles I (1600-1649) which was the idea that tyranny had come to England with the Norman Conquest in 1066 and that the “freeborn men of England” had struggled ever since to place limits on kingly power by means of charters like Magna Carta (1215) or violent resistance if need be as the Civil Wars and Revolution (1642-51) demonstrated. The rulers and their powerful allies were seen as “conquerors” and parasitical “caterpillars” who ate the people’s livelihood and reduced them to poverty. In many of the Levellers’ pamphlets of the late 1640s other animal imagery was used to make the same point: the productive “mill horse” who turned the grind stone at the mill to make floor for bread vs. the unproductive “war horse” who took the soldiers into battle to kill and destroy the property of the people; or seeing the established and privileged church as so many wolves who attacked the defenseless flock of believers by imposing compulsory tithes to maintain their livelihoods. [45]

18th Century Commonwealthmen: John Trenchard (1662-1723) and Thomas Gordon (1692-1750)

By the early 18th century the analysis had become more sophisticated in the writings of the so-called “Commonwealthmen” like John Trenchard (1662-1723) and Thomas Gordon (1692-1750) who turned to Roman history to criticize the practices of the British state after the settlement of 1688 brought William of Orange to the throne. In their Cato’s Letters (1721-23) [46] the landed, financial, and military aristocracies which were the foundation stone of the expanding British Empire were likened to the tyrants of ancient Rome and their court of “hangers-on”. The King’s ministers were corrupt, “factions” and “parties” within the court contended for power (the “Ins” vs. the “Outs”), the court parasites plundered the people, and a standing army kept them and the colonies under control. [47] It was the journalism of Trenchard and Gordon which brought the notion of class to the English colonists in North America who readily adopted it as part of their critique of the British Empire, seeing their struggle very much as a tax revolt by the tax-payers against the tax-consumers of the metropole. [48]

The Enlightenment

Introduction

The second period was the Enlightenments which took place in England, Scotland, and France in the mid and late 18th century. This included thinkers like Adam Smith (1723-1790), Adam Ferguson (1723-1797), Jacques Turgot (1727-1781) and John Millar (1735-1801) who were interested in the nature of productive and “unproductive” labour and who engaged in it, the notion of “rank” within societies, the corrupting influence of political power, the problem of “faction” and “system”, and a four-stage theory of history through which societies moved as their ruling elites and the means by which wealth was created evolved over time. This stage theory of history would have a considerable impact on 19thC ideas about class in both the Classical Liberal as well as in the Marxist camps. [49]

Adam Smith (1723-1790) - 2307w

Adam Smith (1723-1790) was a Professor at the University of Edinburgh (1748-51) and the University of Glasgow (1751-64), a private tutor to the Duke of Buccleuch, and Commissioner of Customs in Scotland (1778-). His thinking about class was largely implicit in that he accepted the general Enlightened idea that history evolved through various economic stages (namely, the stages of hunting, pasturing, agriculture, and commerce) which he expressed in his Lectures on Jurisprudence (1763), [50] that societies were structured according to one’s rank and distinction which he discussed in Theory of Moral Sentiments (1759), [51] and that a complex “system of government” had emerged under mercantilism which granted legal and economic privileges to some manufacturers and agricultural producers at the expence of other consumers and producers, in The Wealth of Nations (1776). [52] Yet, he did not develop any detailed discussion of either the historical evolution of classes or the nature of the class structure of his own day. The basic ideas were there and he referred to them in passing on many occasions but the pieces would not be put together in a more explicit way until later when several of his followers in the English and French Classical School would do just that (see below).

Some of Smith’s ideas about class and class conflict include the following: that societies were divided into “ranks” and “orders” which had their own interests; that the government was a “great system” or a machine which had “wheels” which turned under the influence of “statesmen”, “factions,” “party men”, and “the man of system”; that producers and merchants would often get together to talk about “a conspiracy against the public” in order to further their own private interests; that there were many “unproductive hands” who lived off the taxes produced by the labour of other men; and that opposition by the lower orders to the system of privilege was weak and unlikely to result in violent opposition given their natural deference to their “superiors”. His most detailed discussion of these matters was in the Theory of Moral Sentiments (1759).

Ranks and Orders

Smith believed that societies were divided into “ranks” or “orders” each of which had its own “particular powers, privileges, and immunities“ and that members of these different orders attempted to expand its own “powers, privileges and immunities” and to protect itself from “the encroachments” of every other order.

Every independent state is divided into many different orders and societies, each of which has its own particular powers, privileges, and immunities. Every individual is naturally more attached to his own particular order or society, than to any other. His own interest, his own vanity, the interest and vanity of many of his friends and companions, are commonly a good deal connected with it. He is ambitious to extend its privileges and immunities. He is zealous to defend them against the encroachments of every other order or society. [53]

However, he does not spell out in any detail what these different ranks and orders were (such as social, political, economic, religious), what their power and privileges consisted of, and how their political power was exercised, except in vague and general terms. When he does give specific examples these are taken from classical Roman history and not from his own day. There is also very little discussion of how those with rank got their wealth and position in the first place, whether it was earned legitimately or illegitimately. He suggests that some people regarded as “the great”, did not acquire their position through “the purchase either of sweat or of blood” or “by knowledge, by industry, by patience, by self–denial, or by virtue of any kind,” but by birth (TMS, I.iii.2.4, p. 53). Others, and here he cites ancient Roman examples such as Caesar and Cataline, in spite of “the great injustice of their enterprises” earn our esteem which is not “without utility” because it helps establish “the distinction of ranks” and it teaches us to submit to authority and to “that fortunate violence which we are no longer capable of resisting.” (TMS, VI.iii.30, pp. 252-53.)

The Wheels of the Political Machine

Above the ranks and orders of society was “the great system of government” or the “political machine” which had “wheels” (TMS, IV.1.11, p. 185) which were turned by “statesmen”, “factions,” “party men” (TMS, III.3.43, p. 155), and “the man of system” (TMS, VI.ii.2.17. p. 233). At the pinnacle of political power are the leading “Statesmen” and Princes who sometimes behave like “political speculators” (TMS, VI.ii.2.18, p. 234) who have the “arrogance” to believe that they have all the knowledge required to run a country by themselves. They also sometimes believe that “the state (i)s made for themselves, not themselves for the state.” (TMS, VI.ii.2.18, p. 234.) Smith hints in a general way that the self-interest of members of the government led them to structure “the constitution of the state” in order to promote “the interest of the government; sometimes the interest of particular orders of men who tyrannize the government,” and thus “warp the positive laws of the country from what natural justice would prescribe”. (TMS, VII.iv.36, p. 341.)

Smith spends some time talking about the “factions” which contend for power within the government and “the violence of faction” which this introduces into politics. He thinks these factions can be “civil” or “ecclesiastical” in composition, that there is great “animosity” between the “hostile factions,” and that the resulting conflict creates “turbulence and disorder” in society. (TMS, VI.ii.2.15, p. 232.) He also talks about “party” and the “party-man” and the struggles of “the disconcerted party” to get back into power in similar terms. Smith makes a cryptic reference to there being “the laws of faction” which can be discovered by a study of how factions form and operate but unfortunately he does not go into any details. (TMS, III.3.43, p. 155.) Nevertheless, he concludes that faction in politics is the great “corrupter of moral sentiments”: “Of all the corrupters of moral sentiments, therefore, faction and fanaticism have always been by far the greatest.” (TMS, III.3.43, p. 156.)

Factions and party attract the attention of the politically “ambitious man” both from the lower ranks as well as from the superior ranks. Smith has some acute insights into the behavior and motivation of the “ambitious man” who makes himself a “candidate for fortune” in the system of government. (TMS, VI.iii.40, p. 257.) In order to get to the top they often act above the law and commit fraud, falsehood, and crimes like murder and rebellion to achieve their political goals. Such men hope that “the lustre of his future conduct will entirely cover, or efface, the foulness of the steps by which he arrived at that elevation”.

In many governments the candidates for the highest stations are above the law; and, if they can attain the object of their ambition, they have no fear of being called to account for the means by which they acquired it. They often endeavour, therefore, not only by fraud and falsehood, the ordinary and vulgar arts of intrigue and cabal; but sometimes by the perpetration of the most enormous crimes, by murder and assassination, by rebellion and civil war, to supplant and destroy those who oppose or stand in the way of their greatness. (TMS, I.iii.3.8, p. 64.)

Political ambition is also held by men of “inferior rank” who have to adopt a different path if they wish to climb the political ladder. They typically have some “superior knowledge” in their given profession and demonstrate “superior industry in the exercise of it” in order to make the money they need to buy or “acquire dependents” or political clients who will support them on their way into office. They cynically will take advantage of a “foreign war, or civil dissension” in order to do this. (TMS, I.iii.2.5, p. 55.) Thus, these ambitious men of the middle and lower ranks come to fill the highest offices of government and manage “the whole detail of the administration.” Yet, in spite of their political success, they harbour great resentment towards “those who were born their superiors” and thus had a much easier path into power. This resentment sets up a semi-permanent struggle between “the man of spirit and ambition” and “the man of rank and distinction.”

“The man of system” in Smith’s view was a special kind of politician who sought to control the machinery of government in order to implement some utopian scheme to completely reformulate or restructure the nature of politics. Smith thinks that these “men of system” often start out intending “nothing but their own aggrandisement” but end up becoming fanatical true believers in their cause (“this fanaticism”) and “the dupes of their own sophistry”. (TMS, VI.ii.2.16, p. 233.) He considered this to be a very dangerous form of government should such a man ever get into power, although how it would rank in comparison to what he considered to be “the worst of all governments for any country whatever”, namely “the government of an exclusive company of merchants” in a colony, it is hard to say (WoN, vol. II, IV.vii.b.11, p. 570).

Conspiracies against the Public

In Wealth of Nations Smith famously argued that producers and merchants, as well as more geographically dispersed country gentlemen and farmers, would often get together to talk about “a conspiracy against the public” (WoN, vol. 1, I.x.c.27, p. 145) in order to restrict trade to their own advantage.

People of the same trade seldom meet together, even for merriment and diversion, but the conversation ends in a conspiracy against the public, or in some contrivance to raise prices.