David M. Hart, “Plunderers, Parasites, and Plutocrats: Some Reflections on the Rise and Fall and Rise and Fall of Classical Liberal Class Analysis” (Oct. 2018)

The Libertarian Scholars Conference,

The Kings College, NYC

20 Oct. 2018

An online version of this paper is available here <davidmhart.com/liberty/Papers/Plunderers/DMH-PPP-Oct2018.html>.

Draft: 1 Sept. 2018

Revised: 17 Oct. 2018

Author: Dr. David M. Hart.

- Director of the Online Library of Liberty Project at Liberty Fund <oll.libertyfund.org> and

- Academic Editor of the Collected Works of Frédéric Bastiat.

Email:

- Work: dhart@libertyfund.org

- Private: dmhart@mac.com

Websites:

- Liberty Fund: <oll.libertyfund.org>

- Personal: <davidmhart.com/liberty>

Table of Contents↩

- The Rise and Fall and Rise and Fall of CLCA

- Opening Remarks

- I. A Brief Survey of the Rise of CLCA - “The Other Tradition”

- III. The Marxist highjacking of the CL Concepts of Exploitation and Class

- IV. The Rediscovery of CLCA in the Modern Era - the “Rothbardian Synthesis” or “the second rise” of CLCA

- IV. Areas for Further Research: Problems to Resolve and New Areas to Explore

- The Three Components of CLCA: History of Ideas, Theory, Application (case studies)

- The History of the Tradition of CLCA

- The Pure Theory of CLCA

- The Application of CLCA to the Study of History and Politics

- Conclusion

- Bibliography

- Endnotes

The Rise and Fall and Rise and Fall of CLCA↩

(M)en placed in society … are divided into two classes, Ceux qui pillent,—et Ceux qui sont pillés (those who pillage and those who are pillaged); and we must consider with some care what this division, the correctness of which has not been disputed, implies.

The first class, Ceux qui pillent, are the small number. They are the ruling Few. The second class, Ceux qui sont pillés, are the great number. They are the subject Many.

James Mill, "The State of the Nation” (1835)[1]

Opening Remarks↩

Over the past few years I have been trying to rekindle interest among libertarians on the topic of class analysis, or what I have termed “Classical Liberal Class Analysis” (or CLCA). It has been part of my research interests for decades, in particular my work on 19th century French CL and economists for whom CA was a central feature of their liberalism. About ten years ago I began giving lectures on CLCA to groups of students at the Foundation for Economic Education and the Institute for Humane Studies. Two years ago I organised a discussion on the Online Library of Liberty website which I run, “Classical Liberalism and the Problem of Class” (Nov. 2016), for which I wrote the Lead Essay and which included as discussants Gary Chartier, Steve Davies, Jayme Lemke, and George H. Smith.[2] Most recently, earlier this year in fact, I co-edited an anthology of classic texts of CLCA with Gary Chartier (et al.) on this “other” and largely forgotten tradition of thinking about class: Social Class and State Power: Exploring an Alternative Radical Tradition (Palgrave, 2018).[3]

So, I think it is most fitting that I am here today speaking at the reconstituted (or has it just been “reconvened” after a hiatus?) Libertarian Scholars Conference here in NYC because class analysis was an important component in the original LSCs (going back to 1972) organized by Rothbard and his colleagues Ralph Raico, Leonard Liggio, and Walter Grinder, as we can see from the conference programs and subsequent publication of papers in the Journal of Libertarian Studies.[4] For example:

- The Second Annual Libertarian Scholars’ Conference, New York City, 26 October, 1974:

- The Fourth Libertarian Scholars Conference, October, 1976, New York City:

- Mark Weinburg, “The Social Analysis of Three Early 19th Century French Liberals: Say, Comte, and Dunoyer”[8]

- Joseph T. Salerno, “Comment on the French Liberal School”

I read these papers when I was a college student in Australia and they had a profound impact on me. I corresponded with and then met Leonard Liggio, who took me under his wing and encouraged me to do research on the French classical liberals for whom class analysis was a central part of their social theory. Beginning with Gustave de Molinari (my 1979 undergraduate thesis on his thought was published in the JLS in 1981),[9] then Charles Comte and Charles Dunoyer,[10] Frédéric Bastiat (I’m the academic editor off LF’s big translation project of his collected works),[11] and now the “Paris School” more broadly understood (with a couple of anthologies of their writings in both English and French),[12] and most recently with another anthology on just CLCA which I co-edited: Social Class and State Power: Exploring an Alternative Radical Tradition (Palgrave, 2018).

As I said to Walter Grinder last Friday (12 Oct. 2018) on the occasion of his 80th birthday, the little seed of CLCA which he and Liggio planted 35 years ago has grown (in my case at least), if not into a towering and majestic tree, at least into a hardy bush.

The Second Rise of CLCA↩

When I drew up a list of modern Austrian and libertarian scholars who have worked on CLCA theory (and history) it was rather depressing to realize that this is a field of intellectual activity which has not really flourished since the early days of the LSC in the 1970s and this puzzles me as it seems central to our social theory to understand who has power, how it is wielded, to understand who benefits and who pays for this, and what this tells us about the society in which we live. It also puzzles me because, as I did further research in this field, I came to realize how central it has been to the classical liberal (libertarian) tradition for over 400 years. So why has this aspect of our thinking petered out in recent years (what I call the “second fall” of CLCA - the first having taken place at the end of the 19th century and WW1 when the CL movement by and large collapsed)?

The Austrian economists and modern libertarians who have been interested enough in CLCA to write about it are very few in number (c. 15):

- Ludwig von Mises referred to “caste” since he was very reluctant to use the word “class,” a word which was seen as being tainted with Marxism

- MNR of course through what I have called his “Rothbardian synthesis” of earlier schools of thought, beginning with

- Rothbard, “The Anatomy of the State” (1965).[15]

- as well as all his writings on history too numerous to list here. Typical is his chapter on “From Hoover to Roosevelt: The Federal Reserve and the Financial Elites,” in A History of Money and Banking in the United States: From the Colonial Era to World War II (2002).[16]

- members of the Cercle Bastiat around MNR in the 1950s and 1960s - Raico, Liggio

- Leonard P. Liggio, “Charles Dunoyer and French Classical Liberalism” (1977).[17]

- Ralph Raico, “Classical Liberal Exploitation Theory: A Comment on Professor Liggio’s Paper” (1977) (note that the original version of this paper was delivered at the Second Annual Libertarian Scholars’ Conference, New York City, 26 October, 1974), and “Classical Liberal Roots of the Marxist Doctrine of Classes” (1988, 1992).[18]

- the “next generation” of Austrian Scholars around MNR: Walter Grinder and John Hagel, Mark Weinberg

- Walter E. Grinder, “Introduction” to Albert Jay Nock, Our Enemy, the State (1973). [19]

- Walter E. Grinder and John Hagel, “Toward a Theory of State Capitalism: Ultimate Decision-Making and Class Structure” (1974) (note this paper was given at the Second Libertarian Scholars Conference, October, 1974, NYC).[20]

- John Hagel III and Walter E. Grinder, “From Laissez-Faire to Zwangswirtschaft: The Dynamics of Interventionism” (1975) (note: this paper was given at the Symposium on Austrian Economics, University of Hartford, June 22–28, 1975).[21]

- Possibly also by John Hagel (the unpublished paper is not signed): “Towards a Theory of State Capitalism: Imperialism - The Highest Stage of Interventionism” (1975).[22]

- Mark Weinburg, “The Social Analysis of Three Early 19th Century French Liberals: Say, Comte, and Dunoyer” (1978) (note: this paper was delivered at the Fourth Libertarian Scholars Conference, October, 1976, New York City).[23]

- Joseph T. Salerno, “Comment on the French Liberal School,” Journal of Libertarian Studies, 1978, vol. 2, no. 4, pp. 65–68. (note: this paper was delivered at the Fourth Libertarian Scholars Conference, October, 1976, New York City).

- Roy Childs,

- Robert Higgs, Crisis and Leviathan: Critical Episodes in the Growth of America Government (1987).[26]

- Hans-Hermann Hoppe, “Marxist and Austrian Class Analysis” (1990)[27]

- Tom G. Palmer, “Classical Liberalism, Marxism, and the Conflict of Classes: The Classical Liberal Theory of Class Conflict" (1988).[28]

- David Osterfeld

- Roderick T. Long, “ Toward a Libertarian Theory of Class” (1998).[31]

- myself (following in the footsteps of Liggio, Grinder, and Raico) on Charles Comte, Charles Dunoyer, Molinari, Bastiat, and the Paris School of political economy

- David M. Hart, “Gustave de Molinari and the Anti-Statist Liberal Tradition” (1979, 1981–82).[32]

- David M. Hart, Class Analysis, Slavery and the Industrialist Theory of History in French Liberal Thought, 1814–1830: The Radical Liberalism of Charles Comte and Charles Dunoyer (1994).[33]

- David M. Hart, “Opposing Economic Fallacies, Legal Plunder, and the State: Frédéric Bastiat’s Rhetoric of Liberty in the Economic Sophisms (1846–1850)” (2011). [34]

- The class analysis components in French Liberalism in the 19th Century: An Anthology (2012) and L’âge d’or du libéralisme français. Anthologie. XIXe siècle* (2014).[35]

- David M. Hart, “Bastiat’s Theory of Class: The Plunderers vs. the Plundered” (2016)

- Social Class and State Power: Exploring an Alternative Radical Tradition (Palgrave, 2018).

- most recently Jayme S. Lemke, “An Austrian Approach to Class Structure” (2015).[36]

What the tradition of CLCA involves?↩

I think there are three components which make up the tradition of thinking down as CLCA:

- the history of the tradition of CLCA over the past 400 or so years. This is a history of ideas project, one which I think has been a strong one in the libertarian movement (Liggio, Raico, Weinberg, and myself). It is something I have attempted to document in my recent anthology Social Class and State Power (2018).

- the actual or “pure” theory of CLCA. This was once quite strong but after Rothbard’s death has become weaker as fewer Austrian theorists are involved in developing it further (except perhaps for Long, Hoppe, Lemke)

- the application CLCA to analyzing the current state of society and history. This is the use of CLCA theory in writing works of history and case studies of current practice (political science, sociology, journalism). Again, since the death of Rothbard who used this approach repeatedly in his historical writing and his journalism, this is an area where libertarians have been weak.

I. A Brief Survey of the Rise of CLCA - “The Other Tradition”↩

Introduction↩

When one hears the word “class” one usually thinks of Marxist-inspired social theorists who talk about the exploitation of the “working class” by the “capitalist class” which owns the factories in which the workers labour away producing valuable goods but who do not receive the “full value” of what they create in their wages, and are thus “exploited.” Or more recently, one thinks of those who argue that the “1 percent” which is comprised of the “wealthy elites“ of “Wall Street” who own 90+% of “society’s wealth” and who have “rigged the system” so they continue to receive “excessive profits” at the expense of “the rest of us.” Other common understandings of class have their origins in the work of Max Weber on class and status, [37] or perhaps in the work of C. Wright Mills on power elite theories.[38]

However, this initial reaction would be wrong, or rather incomplete, as it ignores a much older tradition of classical liberal theories of class and exploitation which predate Marxism and which in fact partially inspired Marx in his own thinking about class which he was developing during the 1840s and 1850s. In this essay I want to briefly sketch a history of this “other tradition” of thinking about class, a classical liberal way of thinking about class, which emerged during the 18th, 19th, and early 20th centuries, before it was forgotten for half a century (the first “decline”), only to be rediscovered by Murray Rothbard and his circle of friends (in particular Ralph Raico and Leonard Liggio) in the 1950s and 1960s (this is the “second rise” of CLCA) and which has exerted a certain although intermittent influence on the modern libertarian movement.[39]

A Brief Survey of “The Other Tradition” of CA↩

In this section I would like to briefly survey the main components of what I call “the other tradition” of thinking about class, which constitute eight major streams of thought, as well as the problem of terminology with which CLs have had to face..

In a recent anthology I co-edited, Social Class and State Power: Exploring an Alternative Radical Tradition (Plagrave 2018), we were only able to scratch the surface of a much larger body of CL thinking about class and exploitation which goes back at least 470 years to the Levellers in the English Revolution. The common thread in this tradition of thought is that a small group or people, usually organized in some way in a state or a church, used force or threats of force to take “other people’s stuff” without their permission. There was also the common idea that people had a strong sense of what was “mine” and “thine” and that they objected to the use of force to make mine thine; as well as the idea that by the use of some kind of productive activity I could create things that were “mine” and by other voluntary activities like trading or gifting what was “mine” could legitimately become “thine”. Of course, over time people developed different ideas about was “productive” activity and what was “unproductive” activity, and what actions constituted “exploitation” whereby what was mine became thine unjustly. And this is a key theoretical matter for libertarians and is the source of our fundamental disagreement with Marxists and their theory of exploitation and class.

This long but relatively unknown tradition of thinking about class is quite diverse but has a number of features in common depending upon the sophistication of the economic theories that these thinkers had to work with, and the actual types of class society they lived in and were trying to understand. These common features include the following three key ideas:

(1.) That societies can be divided into two antagonistic groups, most simply put as “the people” vs. their “rulers”, with the defining feature being who has access to political (i.e. coercive) power within a given society. The latter group, “the rulers”, has been variously termed:

- “the single tyrant” and his “favourites” and “petty chiefs” (La Boétie)

- “the ruling few” (Bentham, James Mill, Spencer)

- “the sinister interests” (Bentham, Mill)

- “the oligarchy” (Knox, Wade, Bastiat, Cobden).

(2.) That one of these groups, “the ruling few” is not “productive” and “exploits” the other group (which is “productive”) by taking the latter’s property without their consent or by passing laws which benefit the former at the expense of the latter. These groups have been variously termed:

- “the producers” vs. “the non-producers” (Turgot, Say).

- “ce qui pillent” (those who pillage) vs “ce qui sont pillés” (those who are pillaged) (James Mill)

- “the plunderers” vs. “the plundered” (Bastiat),

- “the conquerors” vs. “the conquered” (Thierry, Spencer, Oppenheimer, Nock),

- “tax-payers” vs “tax consumers” (Calhoun) or “tax-eaters” (Cobbett) or “the budget eaters” (“la classe budgétivore” - Molinari) or the “caterpillars” (the Levellers)

(3.) That societies evolve over time as technology changes and trade and production increase, resulting in new kinds of class rule and exploitation, usually evolving towards a society with greater freedom. These stages have been described variously as:

- evolution through four stages of communal property, slavery, feudalism, commerce (Ferguson, Millar, Smith, Turgot)

- ancient warrior and slave-based society vs. modern commercial and industrial society with a new “industrious class” (Constant, Comte, Dunoyer)

- conquest, slavery, feudalism, then Free Cities, Communes, and the Third Estate (Thierry)

- war, slavery, theocratic plunder, monopoly, bureaucratic plunder, free trade (Bastiat)

- militant vs industrial societies (Spencer)

- the era of tribal community and slavery, the era of small scale industry and monopolies, and the era of large scale industry and complete competition (Molinari)

- the feudal state, the maritime state, the industrial state, the constitutional state (Oppenheimer).

In the early decades of the CL movement it was assumed by many (the Benthamites around James Mill and the Philosophic Radicals) that once the landed and financial elites which controlled Britain had been dispossessed of their political power by democratic reform and replaced by “right thinking” Benthamite reformers, class rule would come to an end. This was a view shared by Marxists who thought that once the capitalists had been overthrown and replaced by the “dictatorship of the proletariat” class rule would automatically and inevitably come to an end. The same can be said today about supporters of the modern welfare state (social democrats) who would be shocked to be told that it too is a class based state. In Molinari’s terminology those who work for the large state-run bureaucracies are members of the “functionary class” who pursue their own interests as any other member of an exploiting class does (and of course as Public Choice theorists have so clearly demonstrated). More hard-headed CLs believed that there could and would be class rule under any political system, democratic or socialist, where some people had access to state power which they could use against others for their own benefit.

The key period during which traditional CLCA emerged in a more coherent form was roughly the one hundred years between 1750–1850, a period which, not incidentally, coincided with the Enlightenment in Europe and North America and the liberal revolutions which accompanied this in America and France in the 18thC, and across much of Europe in 1848.

I list below eight ideological currents of thought which I believe have contributed to the formation of CLCA.[40] Although not all of them can be described as “classical liberal” (as this term had not been invented when many of these authors were writing), they were “liberal” in the sense that they had a concern with individual liberty, property rights, and limited government.

We also have to distinguish carefully between those CLs who used “class language” to describe their opponents in various political campaigns, such as Richard Cobden in his struggle against the land-owning class in Britain (the “oligarchy” and the “borough-mongers”) in his efforts to repeal the protectionist corn laws in the early 1840s, but did not attempt to incorporate this terminology and this manner of thinking into any broader social theory. Class theory was thus implicit in the way he thought about British society. This should be contrasted with his contemporary and counterpart in France, Frédéric Bastiat, who used much the same class language but did attempt to incorporate it into a sophisticated and well-thought out theory of class and history as his plans to write A History of Plunder clearly indicate.[41] Other CLs who integrated their notions of class into a broader theoretical framework include Herbert Spencer and Gustave de Molinari. The CL journalist who wrote the most detailed study of the class structure of the society in which he lived was the English Radical John Wade in his Extraordinary Black Book (1832).

- The Pre-history. I include in this group a couple of early modern and early 18thC thinkers who made the rather crude distinction between “the people” and “the King (or Prince) and his Courtiers”. I include in this group people like La Boétie, Levellers such as Richard Overton and William Walwyn, John Trenchard and Thomas Gordon, and the early Edmund Burke.

- The Anglo-Scottish Enlightenment. Thinkers like Adam Ferguson, John Millar, David Hume, and Adam Smith developed theories about “rank” within societies and a four stage theory of history (such as slavery, feudalism, commerce) each of which had a corresponding ruling elite which benefited from their privileged political position.[42]

- The French Enlightenment. Several thinkers, especially among the Physiocrats (like Turgot), had a similar stage theory of history which was to have a profound impact on 19thC ideas about class in both the Classical Liberal as well as in the Marxist camps.

- Radical Individualists and Republicans. These thinkers were influenced by the American and French Revolutions and were active in England, America, and France. They developed ideas about oligarchies (both aristocratic and mercantile), the growing importance of public debt and central banks, the role of an expanded military and its elites which controlled the empire, and the opposition of established political elites to the rising lower orders who wanted to participate in politics such as working class men and women. The main branches of this group included

- Thomas Paine, Mary Wollstonecraft, William Godwin, Vicesimus Knox, William Cobbett, Percey Shelley in England;

- Thomas Jefferson, John Taylor, John Calhoun, and William Leggett in America, and

- Jean-Baptiste Say, Benjamin Constant, Charles Comte, Charles Dunoyer, Augustin Thierry in France. The latter I think were particularly important in the development of CLCA because of the special problem in France created by the Restoration of the monarchy and the aristocracy after 1815, the legacy of Napoleon’s militarism and centralisation of the state, and the rise of a centralised bureaucracy and the “place-seeking” (job seeking) which took place within the French state.

- The Philosophic Radicals and the Benthamites. The two main thinkers in this group were Jeremy Bentham and James Mill who had a profound impact on the thinking of diverse radicals in the first half of the 19thC in England, such as John Wade and Thomas Hodgskin. Bentham’s idea of the “sinister interest” of the ruling elite and Mill’s contrast between the ruling few and ruled many, were particularly influential. These ideas led John Wade to write an extraordinarily detailed catalog of exactly what groups and individuals in the British ruling elite benefited from tax-payer’s money.

- The Classical Political Economists and their Supporters.

- The English branch of the school got side-tracked by their labour theory of value and theory of rent which led others (such as Marxists and other socialists in France like Louis Blanc) to argue that employers did not pay workers the full value their labour produced and hence “exploited” them, or that the rent paid for land was unearned by the land owner. However, they (Adam Smith and David Ricardo) were strong supporters of free trade and agitators like Richard Cobden adapted this into a class interpretation to criticise the landed oligarchy which ruled Britain and benefited from tariffs at the expense of ordinary consumers. Other topics they were interested in included the condition of the working class, of women (J.S. Mill), and slavery (William Stanley Jevons).

- The French branch of the classical school were interested in the productive role played by the entrepreneur (Say) whom they argued was not a parasite or exploiter, the idea of the existence of an “industrial class” (Comte and Dunoyer), the importance and essential productivity of non-material goods or “services” (Say and Bastiat), the economics of slavery (Heinrich Storch and Gustave de Molinari), the continuing problem of centralisation of government power (Alexis de Tocqueville), the growth of bureaucracy and “place-seeking” (Dunoyer and Molinari), and “plunder” (Frédéric Bastiat and Ambroise Clément). It should be noted here that the French school of CL were much more radical in their approach to CA than their English counterparts were which is something that needs to be discussed in more detail.

- The Sociological School. With the rise of sociology as separate discipline in late 19thC and early 20thC Classical Liberalism made significant contributions, such as the idea of the militant vs. industrial types of society (Herbert Spencer and Molinari), the circulation of elites (Vilfredo Pareto), “the forgotten man” (i.e. the ordinary taxpayer) and rule by a plutocracy (William Graham Sumner), status and rank (Max Weber), and overall theories about the growth of the modern state (Molinari, Gaetano Mosca, and Franz Oppenheimer). Oppenheimer in particular is important because of his later influence on Rothbard in the 1950s and 1960s.

- The Post-WW2 Austrian School, Public Choice, and the Modern Libertarian movement. Several streams of thought have contributed to the modern version of CLCA.

- During WW2 Ludwig von Mises turned to a form of economic sociology with his writings on bureaucracy (1944), the total state (Nazism and Stalinism) (1944), and his general theory of interventionism (1940).[43] Yet he refused to embrace the idea of “class” preferring instead to use the older term “caste” in his writings.[44]

- As a post-graduate student attending Mises seminar at NYU Rothbard played the central role in what I term the “Rothbardian synthesis” of Austrian economics and an older tradition of CLCA, especially the work of John C. Calhoun, Franz Oppenheimer, and Albert Jay Nock. (I will discuss this in more detail in a later post). Rothbard’s synthesis inspired two younger scholars, Walter Grinder and John Hagel,[45] to take his ideas further with an Austrian-inspired class analysis of “state capitalism” in the mid–1970s at meetings of the Libertarian Scholars Conference.

- Another stream appeared beginning in the 1960s with the key players in the Pubic Choice school, James Buchanan and Gordon Tullock,[46] applying their version of free market economics to the study of rent-seeking, the politics of bureaucracy and “Leviathan” without adopting an explicit class interpretation. Nevertheless, their work fits in very well with CLCA.

- There has also been an interesting contribution by Margaret Levi (although no CL) in 1988 who applied a Rational Choice perspective to an analysis of the state and class rule which she appropriately called “predatory rule” which appears to be a clear link back to mid–19thC Classical Liberal theories of class.[47]

The Problem of Terminology for CLs↩

In our Liberty Matters discussion of CLCA,[48] Steve Davies pointed out that CLs did not agree on any given terminology with which to express their class theories. The terms varied considerably according to time and place, and they reflected the particular needs of different individuals who were involved in specific political and economic battles, and their vocabulary changed accordingly. Although they may have shared the same general idea about exploitation they nevertheless expressed it differently. This should be compared to the Marxists and socialists who settled on standard vocabulary very early on and have stuck with it ever since.

My hunch is that one reason for the success of Marxist notions of class since the appearance of The Communist Manifesto in 1848 was how quickly Marxists and their supporters were able to settle on a set of key terms to describe their theory, terms such as the capitalist class and the bourgeoisie (which were “bad”), as against the working class or the proletariat (which were “good”). Classical liberals on the other hand were not able to settle on a similar set of limited terms to describe their ideas about rule and exploitation by a politically privileged elite. When they did use terms to describe their ideas they were very time specific, thus making the ideas behind them seem appear idiosyncratic and perhaps even quaint as the century wore on.

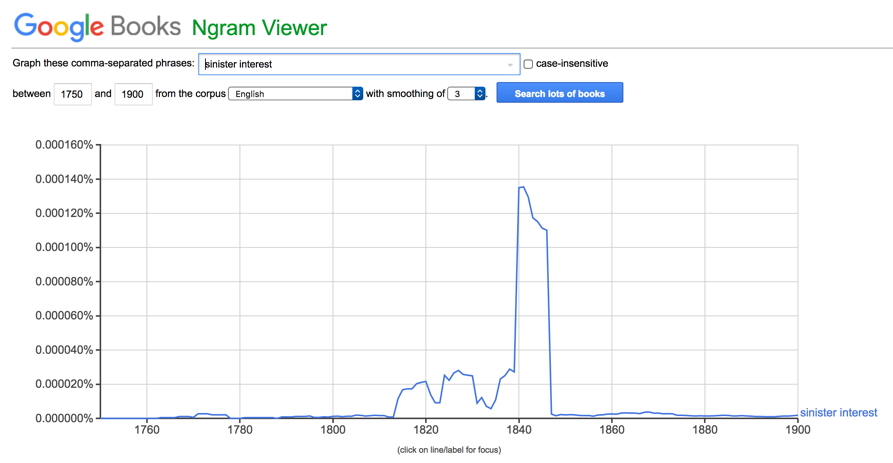

For example, the Philosophic Radicals around Jeremy Bentham and James Mill developed their own unique vocabulary dealing with class with such terms as “the sinister interest” and “the ruling few”. Use of these terms reached a peak[49] in the late 1830s after the success of the campaign for electoral reform with the passage of the First Reform Act in 1832 which ushered in a series of liberal reforms including the repeal of the Corn Laws in 1846. After that, the use of the Benthamite vocabulary of class practically disappeared - along with, I would argue, their notion of class.

Other terms which were common among late 18th and early 19th century radicals were the physiocrat Turgot’s idea of “the stipendiary class” (also used by English speaking authors), those who lived from incomes (stipends) from government service or payments on government loans (peaked in the 1790s); and William Cobbett’s term “paper aristocracy” also used to describe those who lived off the returns of government loans (peaked in 1820 and again in the 1830s), and “boroughmongers” who were able to control elections to the House of Commons by using the seats which were attached to their extensive land-holdings (peaked in 1820 and again during the agitation for the Reform Act of 1832).

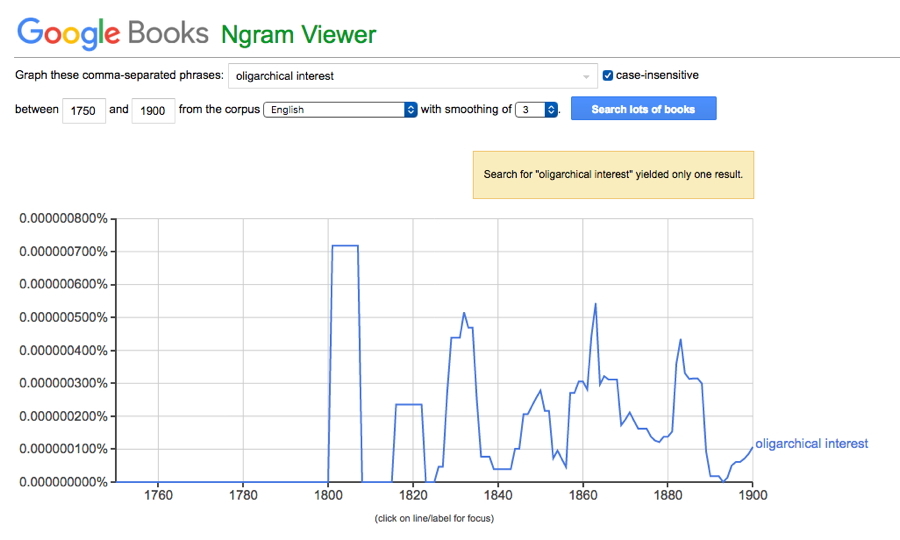

Two exceptions to this tendency for certain terms to peak at the time of some specific piece of legislative reform and then die out afterwards seems to be John Wade’s (a Radical) use of the term “oligarchical interest” with which he used to describe English elites between the 1820s and 1840s, which also had a use periodically throughout the rest of the 19th century when his form of Radicalism had largely disappeared. The same goes for Richard Cobden’s use of the term “squirearchy” to describe the large landowners who benefitted from agricultural protectionism and their control of elections to the unreformed House of Commons. Thus reached a peak during the campaign against the Corn Laws in the 1840s but continued to be quite widely used throughout the rest of the century. It is likely that these terms appealed to other radicals and socialists who used them frequently later in the century.

Later in the century, beginning in the 1870s and continuing for another 20 years, Herbert Spencer began to write his monumental works on political sociology in which he developed ideas like “the militant type” and the “industrial type” of society. The use of the term “militant type of society” peaked in the early 1880s and again around 1890. The graph for the term “industrial type of society” matches this almost exactly, suggesting the two were used as a pair.

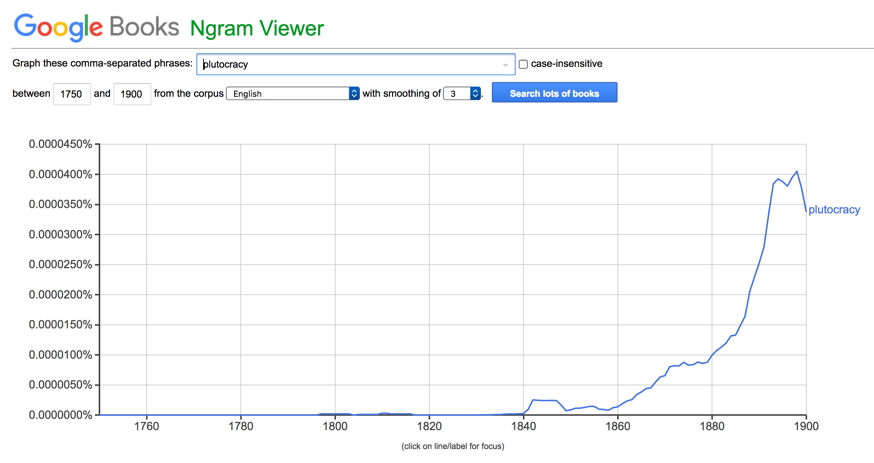

Two other rather generic terms which became popular in the late 19th century are “plutocracy” which was used by the American sociologist William Graham Sumner (peaking in the 1890s) and “ruling elite” which was taken up by Vifredo Pareto in the late 1890s (his notion of “the circulation of elites”). This is another example of a term used by both Classical Liberals and as well as by others and which quickly lost any specifically liberal connotation it might have had.

I believe that CLCA was hampered by the lack of a commonly accepted vocabulary with which to discuss class rule by privileged elites which put them at a serious disadvantage compared to the Marxists and socialists. This reflects the gradual loss of interest CLs had in this idea as the century wore on as well as the fact that class analysis was never fully integrated into modern CL thought as it seemed to be on the verge of doing earlier in the 19th century.

Other reasons for “the fall” in interest in CLCA in the late 19th and early 20th centuries would have to include the move towards the new mathematical economics of Marshall and others, and away from the older historical or philosophical approach to political economy; the widespread “new liberal” belief that government and politics in general could be “tamed” if only the “right people” were elected to office or appointed to senior positions in the bureaucracies. According to this view, “class” would rapidly disappear.

III. The Marxist highjacking of the CL Concepts of Exploitation and Class↩

I should note before concluding this brief survey that in the mid–19thC this Classical Liberal tradition of thinking about class was taken up by Karl Marx, altered considerably, and then diverted into an entirely different theory of class. Ralph Raico[50] and Tom Palmer[51] have documented how Marx borrowed key ideas from the Classical Liberal tradition but emphasised the Smithian and Ricardian errors concerning the labour theory of value, and turned this into a theory of class based upon the inevitable and necessary exploitation of workers via the payment of wages by employers. It should be further noted that when Marx wrote as a journalist, such as The 18th Brumaire of Louis Napoleon (1852),[52] he reverted to a more CLCA approach (where access to political power was crucial to explaining class), but when he wrote as an economist in Das Capital (1859) and elsewhere he increasingly abandoned CLCA and used a more “Marxist” Ricardian approach where the very existence of wage labour introduced exploitation of the works by the capitalists, and thus “class.” I would conclude from this rather confused “farrago” of concepts that “what is correct in Marx’s theory is not “Marxist”, and what is Marxist in his theory is not correct.”[53]

Yet one has to concede that Marx did not get it all wrong as he and his Marxist historian followers generally do ask the right questions about power, which makes their writing of history valuable to CLs (discounted of course for their misunderstandings about how markets actually work!). They typically ask the following key questions: who has power? how is this power exercised? who benefits from this power? (or ”cui bono”), and who suffers from the exercise of this power?

Marxist-inspired history should thus not be summarily dismissed but used cautiously by CLs for insight, inspiration, and evidence. As a history graduate I was introduced to a number of Marxist theorists and historians who asked these questions in a particularly interesting way and I list some of them them here, in no particular order, and would urge class minded CLs to examine their work carefully for lessons on how to go about doing good historical “class analysis”:[54]

- Perry Anderson, editor of the New Left Review and the author of a two volume history of the west in which he explores the issue of class: Passages from Antiquity to Feudalism and Lineages of the Absolutist State (1974)

- Charles Tilly of the formation of nation states in Europe

- Theda Skocpol on “bringing the state back in” to discussions about class

- Robin Blackburn, on colonial slavery and its overthrow

- Moses Finley on slavery in the ancient world

- Eric Hobsbawm on Europe since the French Revolution

There has been a recent spate of historical works from a neo-Marxist class analysis perspective about the rise of modern capitalism by authors such as the Harvard historian Sven Beckert who has written Empire of Cotton (2014).[55]

<!—BREAK—>

IV. The Rediscovery of CLCA in the Modern Era - the “Rothbardian Synthesis” or “the second rise” of CLCA↩

Introduction↩

The older CLCA tradition was rediscovered by Murray Rothbard and his circle of friends (in particular Ralph Raico and Leonard Liggio) in the 1950s and 1960s and this has exerted a certain influence on the modern libertarian movement. I have called this the “second rise” of CLCA.

The great contribution of Rothbard in the modern era was to combine three traditions of thought into a new version of CLCA, or what I call the “Rothbardian synthesis”. His synthesis combined the following:

- an older, classical liberal and radical set of ideas about class and the state which he got from authors such as La Boétie, John C. Calhoun, Franz Oppenheimer, and Albert Jay Nock,[56] with

- his own reworking of Austrian economic theory which appeared in his theoretical works Man, Economy, and State (1962) and Power and Market (1970)[57] and

- a New Left theory of class which appeared in the 1960s (by Gabriel Kolko and Williams, among others)[58] as part of its critique of American capitalism, foreign policy, and the war in Vietnam, which appeared in a series of important essays and pamphlets Rothbard wrote (with Liggio’s input as well) during the 1960s, especially “The Anatomy of the State” (1965).[59]

Rothbard’s Definition of Class and the State↩

I want to begin by quoting Rothbard’s classic definitions of class and the state from his 1965 essay "The Anatomy of the State”:

The great German sociologist Franz Oppenheimer pointed out that there are two mutually exclusive ways of acquiring wealth; one, the above way of production and exchange, he called the “economic means.” The other way is simpler in that it does not require productivity; it is the way of seizure of another’s goods or services by the use of force and violence. This is the method of one-sided confiscation, of theft of the property of others. This is the method which Oppenheimer termed “the political means” to wealth. It should be clear that the peaceful use of reason and energy in production is the “natural” path for man: the means for his survival and prosperity on this earth. It should be equally clear that the coercive, exploitative means is contrary to natural law; it is parasitic, for instead of adding to production, it subtracts from it. The “political means” siphons production off to a parasitic and destructive individual or group; and this siphoning not only subtracts from the number producing, but also lowers the producer’s incentive to produce beyond his own subsistence. In the long run, the robber destroys his own subsistence by dwindling or eliminating the source of his own supply. But not only that; even in the short-run, the predator is acting contrary to his own true nature as a man.

We are now in a position to answer more fully the question: what is the State? The State, in the words of Oppenheimer, is the “organization of the political means”; it is the systematization of the predatory process over a given territory. For crime, at best, is sporadic and uncertain; the parasitism is ephemeral, and the coercive, parasitic lifeline may be cut off at any time by the resistance of the victims. The State provides a legal, orderly, systematic channel for the predation of private property; it renders certain, secure, and relatively “peaceful” the lifeline of the parasitic caste in society.[60]

To summarise Rothbard’s view, he defines the state as “the organization of the political means of acquiring wealth” and class (or caste) as “a parasitic and destructive individual or group” which lives off this politically acquired wealth. I will not go into Rothbard’s theory of the state in any detail here as David Osterfeld has already covered this more than adequately in his 1988 paper “Caste and Class: The Rothbardian View of Governments and Markets.”[61]

Why was Rothbard virtually alone?↩

Apart from a small group of younger scholars around him in the 1950s and 1960s (the Cercle Bastiat, Walter Grinder) other free market economists refused to follow MNR’s lead. The question we need to ask ourselves is why?

I don’t pretend to have a final answer to this questions, but here are some speculations I have:

- the Public Choice school (and also David Friedman and Anthony de Jasay) talks about “vested interests” but not class, and they have some excellent insights which could be incorporated into a Rothbardian-style class theory. Gordon Tulloch in particular has done very interesting work on bureaucracy and the “exploitative state”. However, the Public School economists are very reluctant to apply their analysis to anything which smacks of CA perhaps because of their attachment to being “wertfrei” theorists, or because the word “class” has been tainted by association with Marxism.

- perhaps they and others believe that politics is just a series of ad hoc acts of rent seeking whereas the word “class” suggests something that has become more permanent or institutionalised or systematized (which is what I think has in fact happened with repeated acts of rent seeking over decades). Then question one might ask is, how long does it take before the institutions of the welfare-warfare state and the vested interests who control them and benefit from them become a “class”?

- perhaps they and others think that class analysis is “too conspiratorial” with its focus on particular groups, families, companies, parties, educational institutions, and so on. One of the strengths of MNR’s approach to class analysis, in my view, was his prosopographical method which looked at the interconnections and relationships between powerful individuals, families, corporations, and institutions (especially banking institutions such as those controlled by the Morgans). To some, this approach might seem “conspiratorial” and thus suspect.

- of course, they might think that CLCA is just wrong and should be ignored as worthless

IV. Areas for Further Research: Problems to Resolve and New Areas to Explore↩

The Three Components of CLCA: History of Ideas, Theory, Application (case studies)↩

As I mentioned above, I think there are three components which make up the tradition of thinking down as CLCA:

- the history of the tradition of CLCA over the past 400 or so years. This is a history of ideas project, one which I think has been a strong one in the libertarian movement (Liggio, Raico, Weinberg, and myself)

- the “pure” theory of CLCA which is an interdisciplinary study using the most recent economic theory, political theory, history, and sociology in order to construct a robust and coherent theory of class based upon CL and Austrian theory, which can be useful in the study of societies (both present and historical). This was once quite strong but after Rothbard’s death has become weaker as fewer Austrian theorists are involved in developing it further (except perhaps for Long, Hoppe, Lemke)

- the application of CLCA to the study of history and politics. This is the use of CLCA theory in the writing works of history and case studies of current political practice (political science, sociology, journalism). Again, since the death of Rothbard who used this approach repeatedly in his historical writing and his journalism, this is an area where libertarians have been weak.

The History of the Tradition of CLCA↩

The “intellectual archeology” of the history of thinking about CLCA is the area in which I have been working - and I think that there is a “big book” to be written on this one day! I have already discussed above my thoughts on the eight major streams of thought which have made up the nearly 500 year history of CLCA and I refer you the anthology, Social Class and State Power: Exploring an Alternative Radical Tradition (Plagrave 2018), and its Introduction for more details.

The things I am most interested in pursuing further include the following:

- the more radical and consistent French CL tradition vis-à-vis the weaker English CL tradition.

- the changing language and vocabulary used to describe the exploiters and the exploited over the centuries[62]

- the use of images to depict class relationships[63]

I agree with Steve Davies’s argument that the French CL tradition was more consistent and radical in their understanding of the state and the nature of exploitation and the ruling class. He argues that the “English tradition” didn’t think that the state was inherently exploitative but had ruthless people running it, and if “right thinking reformers” could get into power they would be able to change things fundamentally and bring class rule to an end. This was the strategy behind the Benthamite reformers like James Mill and the Philosophic Radicals during the 1820s and 1830s. In comparison to the English, the “French tradition” thought the state WAS inherently exploitative (or “parasitic” or “ulcerous” to use their own words), that exploitation was inherent in the beast itself, and that reform would not remove exploitation and class rule. To ask Rothbard’s famous question, “Do You hate the State?” which he posed in 1977, one would have to say that many of the French CL did indeed “hate the state,” while most of the English CL did not (with only a few exceptions).[56] George Smith has gone further than Steve Davies by arguing that the division in thinking about class can be found in the difference perspective of CLs (who trust the state by and large) and libertarians (who do not) rather than a difference between English and French CLs.

The implications of this view were “anarchistic,” that only by getting rid of the state would class exploitation come to an end. This was a view that J.B. Say and the younger Charles Dunoyer skirted around but did not confront head on. Only Gustave de Molinari saw this clearly and drew the radical anarchistic conclusions. This is what attracts me to the French CL tradition and their writings on CA and it is an area I wish to continue exploring. I have an anthology of Molinari’s writings of the state due out next year to be published by Institut Coppet to celebrate the 200th anniversary of Molinari’s birth in 1819. I am also putting together a collection of writings by Bastiat on class theory in an attempt to reconstruct his never finished book A History of Plunder which would have been the volume of his magnum opus to follow his Economic Harmonies which would have covered all the Economic and Political Disharmonies which afflicted the world.[64]

The Pure Theory of CLCA↩

What do CLs have to offer that is different?

Introduction

CL and libertarian political and economic theorists need to refine certain aspects of the theory in the light of the innovations which have taken place in these disciplines since the 1970s and 1980s, and there are better people than myself to see where in particular this has to be done. I can only offer in brief note form some of the ideas I have had concerning this matter.

We need to ask ourselves, what are the special insights CL political and economic theory can bring to the discussion of class which is unique and (I would argue) thus make it more powerful than other theories of class (especially the deeply flawed Marxist tradition). For example,

- the unintended consequences of previous government interventions in the economy make society unstable, thus requiring further interventions (Mises’s idea of the dynamics of interventionism) - how does this affect the way ruling elites respond and behave over time?

- the vital role of the banks and government control of a monopoly system of money; the business cycle is caused by government tinkering which lead to periodic “crises” which, in turn, lead to demands for further interventions (Robert Higgs’ “ratchet effect” of increasing power of the state)

- individuals in the government bureaucracies pursue their own private interests (public choice insight) which make them “players” in the system

- in the modern “regulatory state” a complex system of regulations administered by the state bureaucracy in many cases has replaced direct transfers of wealth from one group to another (the whole school of “law and economics” can be drawn upon here for insights)

- individuals matter: the principle of “methodological individualism” means that individuals (especially strong (charismatic) personalities and brilliant individuals do matter (unlike the Marxist view which buries individuals under “materialist” and faceless forces which are at work); hence the need for the “prosopographical approach” to the study of power elites[65]

- also “ideas matter”: Mises’s idea that one’s interests are really the ideas that one has about what constitutes one’s interests (one could be wrong, or change one’s mind)

Applying the Austrian School’s unique insights into the “Dynamics of Interventionism”

We need to explore further how the Austrian School’s unique insights into the “Dynamics of Interventionism” can explain how the state functions and responds to crises as they inevitably emerge.[66] State systems are dynamic because interventions cause problems which must be resolved by more interventions and these “dynamic” processes tend to increase the power of the State over time.

When the vested interests of the ruling elites are combined with an ideology which favours government intervention these dynamics produce greater government intervention in economy/society. (See Robert Higgs on this).

The “dynamics” of the growth of the State include the following:

- Dynamic of Increasing Class Conflict: there is rivalry/antagonism between those who receive benefits from the State and those who pay for those benefits.

- Democratic Dynamic to Expand State Benefits to All: Bastiat’s worry that in a democracy “everybody wants to live at the expence of everybody else”

- Dynamic of the Limit to State Plundering: The “Bastiat & the Malthusian Limit to Plundering” - plundering will continue to expand until all the resources available to the State are used up

- Dynamic of the Higgsian Ratchet Effect of Crisis: periodic crises enable the political class to greatly increase size of government to solve the problem (clamour for the government “to do something”)

- The Misesian Interventionist Dynamic: all government interventions in the economy result in “unintended consequences” (e.g. price controls, minimum wages)

- The National Security Dynamic: fear of invasion or attack by foreign enemy has been a common justification by the State for its “raison d’être”

The Need to bring the Public Choice school into the fold

Even though individual members of the Public Choice school are very reluctant to apply their analysis to anything which smacks of CA, they have some excellent insights which could be incorporated into a Rothbardian-style class theory. I think in particular the work of Gordon Tullock on The Rent-Seeking Society (LF, 2005), “The Politics of Bureaucracy” (1965), “The Exploitative State” (1974), and “The Goals and Organizational Forms of Autocracies” (1987).[67]

Is Rothbard’s Distinction between “net” tax-payers vs the “net” tax-consumers sufficient?

Another problem lies with the rather crude distinction Calhoun developed and which Rothbard took up up, namely the idea of “net tax-payers” and “net tax-receivers.” In the complex world in which we live, where the state has interpenetrated so many aspects of our lives, it is not as clear cut a distinction as it might have been when Calhoun first formulated the distinction back in 1849. Since we are all forced to be tax receivers of some kind (even if only because we walk on state-funded sidewalks and drive on state-funded roads) it is not clear that we have such a markedly different set of “class interests” as tax consumers vis-à-vis tax payers as Calhoun and later Rothbard imagined. Perhaps there is more of a “grey zone” now between the two groups, the complexities of which need to be explored further. If we are not “all Keynesians now”, maybe we are all “tax-eaters” now.

We face what I call “the problem of hybridity”, that societies are now a complex mixture of ways of earning an income, where no-one is a pure tax-payer anymore (we all use government funded roads, electricity monopolists, etc), but where there maybe examples of pure tax-consumers who live solely from money taken from other taxpayers. Again, as Steve Davies has noted, in previous historical periods, exploitation was more obvious as it often coincided with social class (aristocracy, monarchy). In the modern welfare/warfare state the water has been muddied since we all now are part exploiter and part exploitee (it is just that some are more so than others).

- all societies are now a mixture of market (price and consumer driven) and state controls (state and regulation driven)

- at one extreme there was the centrally planned Soviet Union (yet even there, there were (black) markets in the interstices)

- in other more market “oriented” societies (there are no fully laissez-faire societies) there are massive government interventions

- there is the question of the stability of these hybrids; can they stay put at one location on the spectrum, or are they focus by events to move either towards more intervention (Mises) or more deregulation? Idea of there being a “local well” of stability, as it requires too much effort/cost to go to either extreme, without some crisis/revolutionary event to make it inevitable or necessary.

Gary Chartier and Jayme Lemke have both observed that the growth of the regulatory-cum-administrative state has meant that state benefits can’t all be seen in terms of cash transfers (“tax dollars”) from one group to another. The result of this mass or regulation is that there are now multiple sources of class privilege which can harm some and benefit others (such as regulations about occupational licensing). Class structures should instead be conceived as complex systems in which power and privilege can vary across social groups in many different ways simultaneously depending on what kind of rules are in place and how those rules are interpreted and applied. Considering class structure in this way puts the focus on bureaucratic and administrative rules and how they affect different groups of people, which complicates Rothbard’s more simplistic model considerably.

Rothbard’s theory also raises a number of other questions:

- what are the class analysis implications of Rothbard’s binary/tertiary intervention

- “binary intervention” - implies 2 classes: the exploiting state (“the Few”) and the exploited many taxpayers/ruled (“the Many”)

- “tertiary intervention” - implies a third ancillary class (Bentham’s sub-ruling class) which benefits from subsidies, forced exchanges/monopolies

- shows complexity of possible class relations

- direct political access vs indirect political access

- direct economic privilege vs indirect economic privilege

- outright ownership of another - chattel slavery

- partial ownership of another - serfdom, convictism, conscription

- ownership of the product of another’s labour - confiscation of property, taxation of % of labour product

- preferential private ownership of means of production - land grants by monarch or state, monopoly of industry, govt licences (broadcasting, doctors)

- preferential pricing of goods - tariffs, monopolies. licences

- direct subsidies and grants - to the elite, to the masses, arts (museums, opera houses, symphony orchestras), education (state universities), welfare (food stamps, hospitals, pensions)

- state supported industries - state owned industry, military-industrial complex, private prisons

- access to power/legislation - member of parliament, party control, limits on parties/voting, sit on parliamentary committees which draw up legislation, lobbyists, advisors to political leaders, cabinet members, influencing tax legislation (deductions, exemptions)

- indirect economic influence - setting interest rates, money supply, banking licences, company board membership

- problem of the 50% level where do a person’s interests ultimately lie?

- if less than 50% of income is economic?

- if more than 50% of income is economic?

- if less than 50% of income is political?

- if more than 50% of income is political

- revolving door of modern era - work for state for 4 years then enter “private” sector as lobbyist, consultant, director

The Importance of a Interdisciplinary Approach to the Study of Class

One of the great strengths of CL/Libertarianism is its interdisciplinary approach to the study of liberty and state coercion. Thus, we also need to integrate sociological, historical, economic, and intellectual approaches into the study of CLCA. This used to be the case in the 19th century when CLs drew upon a range of disciplines to make their arguments against class exploitation and class rule. They stepped beyond just economics and in the late 19th century sociologists and political theorists such as Vilfredo Pareto, William Graham Sumner, Gaetano Mosca, and Franz Oppenheimer made this multi-discipline approach central to their theory. Steve Davies for one argues that Rothbard’s theory lacks the richness and variety of the older 19th century tradition. It is much more of a theory driven by economics and lacks the dense sociological and historiographical support that the older theory had. I would not go so far as that but I think it is partly true.

Any revised CLCA theory needs to incorporate the following kinds of analyses:

- a sociological analysis - generalizing from history of the state using theoretical insights drawn from economics, political theory, history

- the political means vs. the economic means of acquiring wealth (Oppenheimer)

- voluntary exchange vs. plunder/exploitation by force/coercion

- ratchet effect of war and crises in state growth (Robert Higgs)

- militant stage of social evolution (H. Spencer)

- circulation of elites (V. Pareto) - “ins” vs “outs”

- an historical analysis - history of actually existing states (origin of our own state)

- primitive state began when dominant warrior, holy man, bandit made his exploitation permanent - roving bandits became stationary bandit

- ruling individual claimed “legitimacy” through divine right, tradition, guarantor of “stability”

- institutions of state organization began as organization for war

- war is the purest form of the political means of acquiring wealth

- an intellectual-historical analysis of the state - what people have thought about the state and the ruling class over the centuries

- classical liberals (libertarians) in the late 18th and 19th centuries

- Marxist theories of class in the mid and late 19thC

- 20thC notions developed by Austrian School and others (Mises, Rothbard, Higgs)

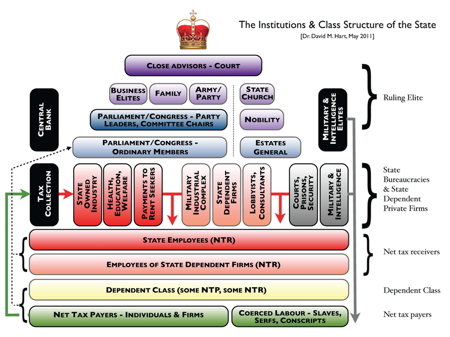

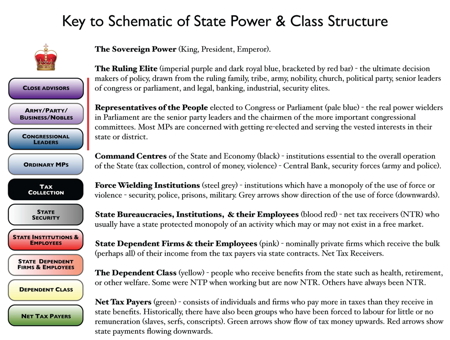

Refining the Taxonomy of Class

It is important to create a more agreed upon “taxonomy of class” so that libertarian scholars can use a more coherent theory of CLCA in their research. I have identified seven different types of class in an attempt to do this. I have singled out the following for special attention by scholars, which is accompanied by an attempt at a graphical representation (schematic) of their interrelationships:

- the Ruling Elite,

- the Political Class,

- the Bureaucratic Class,

- the Plutocratic Class,

- State-Dependent Firms,

- the Dependent Class, and

- Net Tax-Payers

Schematic of State Power and Class Structure

(1.) The Ruling Elite (“Deep State”) - those who control the “commanding heights” of the state (the presidency, Congress, military, intelligence services, Federal Reserve (or state bank), Supreme Court, etc.)

(2.) The Political Class - elected politicians who sit in Congress (especially those who head important committees which control spending and formulate legislation); senior bureaucrats who run the main government bureaucracies; and wealthy and influential “private individuals” from finance, banking, think tanks, industry (especially defense and communications); and media moguls who advise the government on policy matters.

(3.) The Bureaucratic Class, or Functionaries of the State - those who carry out and implement the government policies

- special subcategory of those who use force to implement state policy, members of the military, police forces, prisons

(4.) The Plutocratic Class (WGS) or Crony Capitalist Class - very wealthy and influential business owners who actively seek to get or retain special privileges from the state in the form of subsidies, contracts, monopolies, favorable legislation, favorable monetary policy,

(5.) State-Dependent Firms and their Employees - nominally private firms which receive the bulk (perhaps all) of their income from the tax-payers via state contracts

(6.) The Dependent Class - people who receive benefits from the state such as health, retirement, or other welfare benefits but who are not “rulers”.

(7.) Net Tax-Payers - most of us would fall into a “grey zone” where we pay taxes but also “consume taxes” in the form of using streets and getting police protection from robbers. Then there are the people who change their class status over time, people who are net tax-payers in their prime working years and then become net tax-receivers in their retirement.

The Tensions between Class Theory and Methodological Individualism

Another more general problem, one which Jayme Lemke has discussed in her recent and important paper,[68] is how CLCA can be reconciled with methodological individualism which lies at the heart of modern Austrian economic theory.

When do Vested Interests become a Class?

A good question to ask is, when do one off instances of rent-seeking become institutionalised over time and evolve into a more established "class”?

Public Choice analysis looks at the organisations and individuals who seek privileges and political “rent” from the state. Are they just disorganised, one-off, ad hoc attempts to get benefits at the expence of each other and the broader tax-paying public? Can they come together to organise a better way to achieve their common goals over time (and thus form a “class” with a conscious awareness of who they are and what they are doing) or are such attempts constantly disrupted by rivalry with each other? If they do manage to organise amongst themselves, how long does it take before they become an “institution” like a “ruling class”?

We now have decades of repeated “rent seeking” by the same entrenched organisations and groups, lobby groups, permanent bureaucracies and professional bureaucratic managers, to the point that it might now make sense to talk about “the rent seeking class or classes”. For example:

- the military industrial complex since WW2;

- banking interests since the Great Depression and the New Deal;

- farming groups since the Great Depression;

- elites which control and advise the two major parties on the American duopoly;

- “dynasties” which emerge in Congress/Presidency over time (e.g. Presott/Bush, Kennedy family, Clintons).

The “Commanding Heights” of Society and the State: How important are the Banks?

Where does ultimate power lie? and who controls it? The CL tradition often focussed on banks and paper money (who controlled the purse strings); the military (who controlled the guns); and the parliament (who made the laws). This is something CLs might argue about as the following institutions all play important roles (I limit myself here to only American examples, but all countries have their own equivalents):

- money and banking: the Federal Reserve cartel

- the police and intelligence agencies: the FBI, NSA, CIA, etc

- the military: the armed services, the Pentagon

- foreign affairs and security: Council on Foreign Relations

- tax collection: the IRS

- the formal institutions of government: Congress, the Republican and Democratic Parties (the institutionalized duopoly)

There is a song thread within CLCA which focuses on money and banking as the key source of power in the state. William Cobbett in the first decade of the 19thC thought that a new kind of aristocracy, a “paper aristocracy”[69] dependent of paper money, had emerged in Britain which benefited from the banking system and the need of the government for loans to fund the war effort against Napoleon. The power of central banks (or the Federal Reserve) is also highlighted by Grinder and Hagel as one of the central sources of power within the modern state, control of which is crucial for controlling all other aspects of economic life in the modern era. It was also a great concern of Rothbard’s. This sector continues to be of vital importance in the post-Financial Crisis (2008) era given the unprecedented experiments central banks are conducting with their policies of Quantitative Easing, ZIRP (Zero interest rates), and negative interest rates. What groups are benefiting from these monetary experiments and who will ultimately pay for it?

There is a great need to extend the pioneering work of Grinder and Hagel and update and refine it for the modern era.

The Relationship between “Interests” and Ideology

Both Jeremey Bentham and Frédéric Bastiat[70] stressed the way in which elites spread misinformation or “fallacies” (Bentham) or “sophisms” (Bastiat) in order to hide how elites went about getting their privileges (usually through Parliament or Congress) and to deflect criticism by the general public. How has the spread of mass communication in a democracy made this process of deception and obfuscation easier or harder for elites to achieve this? What role do “flatterers” (a term used frequently by Trenchard and Gordon), “court intellectuals”, and today the Main Stream Press play in this process?

The Psychology of those who Seek and Get Power

This is an area of study where psychology, history, and politics overlap. Many CLs have asked the questions, who is attracted to positions of political power over others? why are they so attracted? how do they behave once they have reached positions of power?

One answer is that “the worst” get into positions of power, or as Hayek phrased it in 1944, “on top.” The radical minister Vicesimus Knox in his essay on “Despotism” (1795)[71] asked the same question Hayek would ask in 1944 in The Road to Serfdom, “Why do the Worst get on Top?”[72] Knox wanted to know what type of person was attracted to political (or military) power, what skills they needed to be successful, and what this kind of personality and behaviour meant for a free society. The “pathology of power” has been studied in the case of dictators like Hitler, Mao, or Stalin but their counterparts in democracies less so, such as Winston Churchill, Tony Blair, Lyndon Johnson, and Richard Nixon, and now perhaps Donald Trump.

There are some famous (perhaps infamous now) studies which examine the behavior of power who have, or think they have, power over others, such as experiments conducted by Stanley Milgram at Yale University ion 1961, the “Stanford Prison Experiment” of 1971 conducted by Philip Zimbardo. [73]

This suggests that there is an new field to be developed examining the “pathology of rulers.”

Other Matters

Why are there so few Libertarian/CL Sociologists?

An obvious question to conclude this general discussion is to ask, why are there so few CL sociologists (whom one might have expected to have been interested in the matter of CA)? The notable exceptions to this trend are people like Robert Nisbet[74] and Stanislav Andeski.[75] I’m not sure I have a good answer to this, except for the observation that the term “class” is just so tainted by Marxism that CLs refused to touch it.

The Application of CLCA to the Study of History and Politics↩

The biggest task before us is to apply CLCA theory to the study of specific examples of exploitation and class relationships in current politics (political science, journalism, sociology) and how these class societies came about and changed over time (history). These are huge fields but some of the more important tasks (or opportunities for research) in my view are the following:

- the history of the origins of the state (a mixture of archeology and anthropology) could be enriched enormously with the introduction of economic insights

- resurrecting the old tradition of “muck raking” journalism to expose the current corrupt practices of those with access to state power which they use for personal enrichment

- who are the current main beneficiaries of rent seeking?

- who are the politicians who are coordinating this behavior? (acting as “brokers” of political rents)

- meticulously describing the various branches of the government and its bureaucracies, showing how tax money is channelled into the hands of key vested interests, how this began and how it has changed (and grown) over time

- case studies of particular industries which have very close ties to the state (the military-industrial complex, the computer and surveillance industries, the drug-medical-insurance industries)

- applying CLCA to completely new areas such as the structure of classes and the nature of exploitation in socialist, Marxist, and welfare states

- studying the inevitable resistance to heavy taxation and government regulation, such as tax revolts, black market activity, secessionist movements, etc.

History of the Origins of the State

Since Oppenheimer played an important role in the reveal of interest in CLCA theory in the 20th century we should re-examine his work closely, especially his theory of the rise/origin of the state in the light of recent archeological and anthropological studies. He also needs a proper intellectual biography (not all his work has been translated into English).

Some work has already been done in this area by Robert Carneiro, A Theory of the Origin of the State (1977) and Mancur Olson on “roving bandits” vs. “stationary bandits”.[76]

“Muck Raking” Journalism

We need a good dose of muck-raking journalism to expose current ongoing “rent-seeking” and favours; politicians who personally or whose families benefit from state contracts and legislation ("lifting the lid on the political sausage factory”).

Describing/Documenting the current Vested Interests

We need to be able to identify the key players in any given class system. This involves using a power-based “prosopography” of who is related/connected to whom and how they use these connections to better themselves at tax payer expense, and how this changes over time. For example:

- biographies of key ruling families such as Prescott/Bush, Kennedy, Clinton; Windsors (Queen Betty)

- key rulers: the work of Robert Caro on LBJ is a model of this in many ways

- key industries: oil, Boeing, finance, banking

- regional rivalries, North vs South, East vs West

Part of this effort is also to show that we have the best explanation for and understanding of “crony capitalism”; that CLCA also explains the class rule which emerges within crony capitalism. We need to move beyond the naive Randian notion of capitalists as “persecuted heroes.” Rothbard did some good work using New Leftists like Gabriel Kolko to show how this happened but libertarians have been reluctant to take this much further (almost as reluctant as Kolko was to allow libertarians to use his work in this way).[77]

We need to compile a new “Black Book of Statist Privilege.” A model example of the kind of thing I have in mind is an updated version of John Wade’s Extraordinary Black Book (1832) which meticulously documented “cui bono” (who benefited) from the British state in his own day. The radical John Wade[78] compiled a very detailed list (some 850 pages) of people and groups who lived off tax-payers’ money in the 1820s and 1830s - from the Civil List of royalty, to the privileges and property owned by the Church of England, to the sinecures of the children of aristocrats, to the pensions of ex-government employees, army officers, and politicians. This book badly needs to be updated to cover the modern welfare/warfare state.

Something like this was attempted by Ferdinand Lundberg on the “Sixty Families” (1937) who ruled America in the first part of the 20th century.[79] This also needs to be updated to the present as Fraser and Gerstle have attempted to do in Ruling America (2005).

The Dynamism of Class Rule: The “Ins” vs. the “Outs”

Class rule is not static so we need to be able to identify who is “In” and who is “Out”; and how ruling elites maintain themselves and/or change over time. There is also the question of “churn” within the ruling elite as new members enter and others live.

It is also a mistake to think that the ruling elite is monolithic. Not only is the membership changing over time (Pareto’s notion of “the circulation” of elites, and the idea of “the Ins” vs. “the Outs”) but there are important gradations of power and influence within the elite group. Thus we need to be able to describe in some detail “the gradations of tyrants” to use a good 18th century notion.

Both Trenchard and Bentham were interested in the complexities within the hierarchy of those who comprised the “ruling few.” They understood that it was not homogeneous but made up of many different levels with different privileges and powers. Bentham talked about “the sub-ruling few”[80], Gordon talked about a “gradation of tyrants” and “deputy tyrants”[81] who were rivalrous for power within the oligarchy, and La Boétie talked about a pyramid of power with the tyrant at the top and several hundred chiefs and petty chiefs below him who exploited the people.

In his essay on “The Circulation of Elites” (1900) Vilfredo Pareto[82] explores the important question of how open entrenched elites are to new comers. A common way to describe a circulation of elites taking turns to rule is John Wade’s “the Ins” vs. “the Outs”. In our own “democratic” societies it is assumed that the elites are open to some degree to outsiders. But is this in fact true, given the continuing importance of what school you went to (such as the preponderance of Yale and Harvard among members of the ruling elite), and the persistence of certain elite families in banking, law, and finance circles?

We need to study the ever ongoing struggle within the elite by rival groups with one elite trying to become predominant. “Class conflict” is not just “inter-class” conflict between the rulers and the ruled; but also “infra-class” conflict or rivalry within the ruling elite for position and power (“jostling”). The various factions sometimes form alliances to pursue their goals; at other times they fight each other quite ruthlessly for dominance. Thus we need to be able to be able to identify the key vested interest groups, their power, composition, changing fortunes, such as the military-industrial-security complex; medical-pharmaceutical complex; welfare complex; for them survival is a “zero sum game” to get control of tax money and legal system.

Resistance from Below

Class rule always provokes resistance from below by those who resent having to pay to keep the ruling elites in power. This can take various forms:

- at the large scale end of the spectrum it provokes revolts and revolutions which are inevitable but rare

- most of the time resistance is small scale, tax evasion/avoidance, black markets to escape onerous regulations and taxes

- this stimulates the rise of reformist parties to attempt to lessen the burden on the tax payers

- it also stimulates the ruling elites to “crack down” on dissent and rebellion in order to ensure their continued rule

Filling the Gaps in Class Theory: A Class Analysis of Communism and the Welfare State

One of the many great flaws in the classic Marxist theory of exploitation and class was its blindness to the possibility of any ruling class emerging in the future communist or socialist society. Since Marx viewed class in social or economic terms he paid little attention in his theoretical work to “political class”. Only in his journalism did he revert to a political notion of class.

The advantage a CLCA approach has is that it is more encompassing than other theories and in fact predicts that a ruling class of exploiters is inevitable in a socialist or communist society, if only because such as society will have a state which exercises power. This will inevitably attracted some individuals who wish to use this power to further their own interests at the expense of others. This individuals have come from the communist party, the military elite, factory managers, secret police, and so on. In the modern welfare state there have been state functionaries, large national companies, trade unions, intellectuals in state employment, all of who push their way to the top.

We desperately need a good class analysis based history of communist and welfare states in order to show how they do little to advance the needs of the ordinary people who pay for their expensive and inefficient (and sometime deadly) upkeep.

Conclusion↩

In a topic as broad as this one all I have been able to do in this paper is to sketch briefly the history of the “alternative tradition” of thinking about class, that is the CLCA, and to suggest some areas where it needs work by other scholars in order to re-invigorate and strengthen it.

I think this is a fitting venue to do this as these ideas were an important part of the Libertarian Scholars Conferences in the first few years of their existence and I am very glad to have been able to reconnect with those early pioneers of the “second rise” of thinking about CLCA. I hope to see a third one in the not too distant future.

Bibliography↩

H.B. Acton’s book The Illusion of the Epoch: Marxism-Leninism as a Philosophical Creed (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 2003).

Perry Anderson, Lineages of the Absolutist State (London: Verso, 1979)

Perry Anderson, Passages from Antiquity to Feudalism (London: Verso, 1979).

Stanislav Andreski, Parasitism and Subversion: The Case of Latin America (New York: Schocken, 1969).

Frédéric Bastiat, The Collected Works of Frédéric Bastiat. Vol. 3: Economic Sophisms and “What is Seen and What is Not Seen.” (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 2017). http://oll.libertyfund.org/titles/2731.

Sven Beckert, Empire of Cotton: A Global History (New York: Vintage, 2014).

Jeremy Bentham, The Book of Fallacies (1824), in Jeremy Bentham, The Works of Jeremy Bentham, published under the Superintendence of his Executor, John Bowring (Edinburgh: William Tait, 1838–1843). 11 vols. Vol. 2. http://oll.libertyfund.org/titles/1921#lf0872-02_label_846.

Robin Blackburn, American Crucible: Slavery, Emancipation and Human Rights (London: Verso, 2011).

Robin Blackburn, The Making of New World Slavery: from the Baroque to the Modern, 1492–1800 (London: Verso, 1997).