Jacques Callot and Hugo Grotius on Crime and Punishment in a time of War

|

| Title Page of "The Large Miseries and Misfortunes

of War" (1633) |

Date: 16 March, 2022

Introduction

In this "illustrated essay" I want to explore the problem of war in 17th century Europe by juxtaposing an image from the series of 18 etchings made by Jacques Callot showing the ravages of war in his native Lorraine during the Thirty Years War (1618-48), with passages from Hugo Grotius, The Rights of War and Peace (1625) which is a foundation stone of the modern understanding of the laws of war.

For example, in this the 7th picture in the series, "Plundering and Burning a Village", we see armed soldiers pillaging and burning a village which includes a small chapel in the upper centre (there is a cross to its left). The inhabitants and livestock are rounded up to be taken off as prisoners or booty. Livestock can be seen being herded at the lower right. A man can be seen being killed at the lower left under a tree.There is a grieviig wife who sits next to her dead husband in the centre foreground. Grotius noted that conquest of territory traditionally gave the conquerors "possession" of what they seized but he thought it strange to then go about destroying what had taken so much effort to acquire: "it is not a strange Conduct, to make War in such a Manner, that at the same Time, we dispute the Possession of a Thing, we leave nothing for ourselves but War". He discusses this and other matters in a chapter called "Concerning Moderation in regard to the spoiling the Country of our Enemies, and such other Things." [p. 653]

|

| 7. Plundering

and Burning a Village [See a larger version of this image (1368 px)] |

Jacques Callot (1592-1635)

The "French" engraver Jacques Callot was born in the independent Duchy of Lorraine (which later was conquered and incorporated into France). He worked for some of the most illustrious political leaders of the early 17th century - Cosimo II de'Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany, the dukes of Lorraine, Louis XIII King of France, and the Spanish Infanta, Isabella.

Callot lived through the 30 Years War (1618-1648) and depicted several aspects of the war and its impact on ordinary people. A contemporary of Callot's, Pierre Vuarin, described the invasion in his journal:

Callot's work ranged from large and elaborate "military maps" such as "The Siege of Breda"(1627-9), to smaller studies of soldiers enagaging in "military exercises", to depictions of ordinary people whose lives were disrupted by the war such as beggars and gypsies. Callot is best known for his series of etchings which he originally called "La vie des soldats" (the life of soldiers) but which were later published in two versions as "The Small Miseries of War" (six illustrations) and then "The Large Miseries of War" (1632) (18 illustrations).In transit they killed everyone they encountered as if it were open warfare. They burnt villages raped girls and women, pillaged and damaged churches and altars, carried away everything of value and did unheard of damage even though His Highness (Duke Henri II) provisioned them. Further they cut growing corn as feed for their horses which they stabled in churches. Everywhere they did infinite damage, stealing furniture and livestock, which they managed to discover even when hidden in the remoteness of woods.

For five whole days they (the Prince of Phalsbourg and his men who were supposed to be repelling the invaders) lived off the country, pillaging and extorting money like the enemy forces... The poor villagers returning to their villages after the passing of the soldiery picked up infections from human and animal carcasses left behind by the marauders. A third died from dissentry and other infectious diseases in the villages through which the soldiers had passed. [Callot’s Etchings : 338 prints. Ed. Howard Daniel (New York: Dover Publications, 1974), p. xix.]

For an overview of Callot's work see this earlier essay of mine "Jacques Callot (1592-1635) and the Miseries of the Thirty Years War."

Source

The Art Gallery of New South Wales: "The Miseries and Misfortunes of War" <https://www.artgallery.nsw.gov.au/collection/works/?group_accession=DO10.1963.1-18>

The Cleveland Museum of Art: <https://www.clevelandart.org/art/collection/search?search=1923.277&filter-include-parts=1>

The National gallery of Canada <https://www.gallery.ca/collection/search-the-collection?search_api_views_fulltext=&sort_by=field_date_made_earliest_year&f%5B0%5D=field_reference_artist%253Atitle%3AJacques%20Callot&page=13>

The original 1633 edition of "The Large Miseries of War": Recueil de gravures du XVIIe siècle. Les Miseres et les mal-heurs de la guerre. Representez Par Iacqves Callot Noble Lorrain et mis en lumiere Par Israel son amy. Suivi de : Diverses gr. de Jacques Callot Publisher (A Paris, 1633). [the complete collection of engravings facs. PDF; just the "Miseries of War" facs. PDF]

Hugo Grotius (1583-1645)

Huigh de Groot (Latinised name “Hugo Grotius”) was born in Delft, Holland. He was a child prodigy who entered the University of Leiden in 1594 (aged 11), where he studied philosophy and languages, writing poetry in Greek and Latin. His early career was s a lawyer then a diplomat for the Swedish government in Paris. After getting entangled in a religious controversy when he was 36 years old, he convicted of treason and imprisoned for life in the fortress at Loevenstein and had all his property confiscated. After 21 months he was able to escape with the assistance of his wife who had the right of cohabitation in prison. Grotius hid in trunk used to carry his books while his wife substituted for him in his cell. H fled to Paris where Louis XIII granted him sanctuary. He became the Swedish representative in Paris for 10 years and worked in negotiating peace treaties during the 30 Years War.

He is best known as legal theorist. Legal with works dealing with war such as Mare Liberum (The Freedom of the High Seas) (1604-06) dealing with the legal aspects of taking prizes (the seizure of booty and spoils) on the high seas. His best known work is The Law of War and Peace (De jure belli ac pacis) (1625) in which he explores what the law has historically said about how war should be declared and conducted, and in particular how war could be subjected to the rule of law. His work became a classic of international law or the law of nations. He advocated restraints in the conduct of war, many of which were written into international law as part of Hague and Geneva conventions.

Source

Hugo Grotius, The Rights of War and Peace, in Three Books. Wherein are explained, the Law of Nature and Nations, and the Principal Points relating to Government. Written in Latin by the Learned Hugo Grotius, Hugo, and translated into English. To which are added all the large Notes by Mr. J Barbeyrac, Professor of Law at Groningen, and Member of the Royal Academy of Sciences at Berlin. (London : Printed for W. Innys and R. Manby, J. and P. Knapton, D. Brown, T. Osborn, and E. Wicksteed. MDCCXXXVIII). [HTML and facs. PDF]

Other works by Grotius at this website.

An Overview of Callot's "The Large Miseries of War"

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The titles of the 18 images [the images above are listed in order from left to right and then top to bottom] the link will take you to the image and the quote from Grotius]:

- Title Page

- The Recruitment of Troops

- The Battle

- Scene of Pillage

- Plundering a Large Farmhouse

- Destruction of a Convent

- Plundering and Burning a Village

- Attack on a Coach

- Discovery of the Criminal Soldiers

- The Strappado

- The Hanging

- The Firing Squad

- The Stake

- The Wheel

- The Hospital

- Dying Soldiers by the Roadside

- The Peasants avenge Themselves

- The Distribution of Rewards

The Chronology and Structure of the set of images.

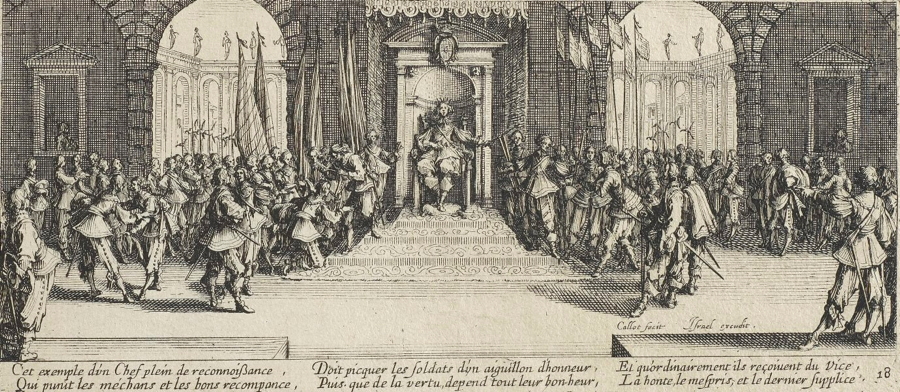

"The Large Miseries of War" forms a story in 18 panels. It shows the recruitment of troops, battle, scenes of plunder and other crimes, then a variety of punishments, a hospital and dying soldiers, revenge by peasants, and a final scene of the distribution of legal rewards by prince. Overall, the set seems to suggest a strong Christian view that wrongdoers will be punished directly by the Christian Prince or indirectly through the just actions of others (peasants' revenge). It expressed a somewhat forlorn hope that in spite of the chaos and lawlessness of the 30 Years War, justice would eventually triumph.

If one ignores the title page the set is bounded at each end with an image which depicts considerable order and the transfer of money. In image 2 the mercenary troops are being mustered and we can see some new recruits being paid. In image 18 we see the monarch presiding over a gathering of senior officers who are being rewarded for their actions with medals, money, grants of land, and other benfits typical of the period.

The image adjacent to both these images depicts combat and warfare between two organised groups. In image 3 we see a formal battle between two unidentified armies on an unidentified battlefield. In the historical context, this is probably between the forces of the French King Louis XIII and the nobles of Lorraine who were resisting the French invasion of their land. In image 17 we see a band of peasants who, guerrilla like, have ambushed in a forest clearing a party of soldiers of unknown allegiance (French or Lorrainers) and are exacting revenge for the looting and plundering which have gone on in images 4-8.

In images 4-8 we have 5 depictions of soldiers looting, pillaging, raping, torturing, and murdering civilians (presumably Lorrainers by French soldiers). It was expected of 17th century armies that they live off the land because the financing and organizing of large armies by the state was in its infancy. There was a very fine line between officially sanctioned "foraging" for food and supplies which had to be supplied by the local peasantry and the unofficial, private looting and pillaging undertaken by poorly paid mercenary soldiers. It seems clear from these depictions that Callot is showing us the latter rather than the former.

The image which serves as a hinge for a largely symmetrical set of images is image 9 where a band of "criminal soldiers" who had stepped over the line between offically santioned "foraging" into unsanctioned "pillaging" have been arrested and are being returned to camp presumably for punishment.

Image 9 is followed by another 5 images (10-14) in which very severe and brutal punishments are metered out by the army to the criminal soldiers. Groups of other soldiers have been formed to witness these punishments as a warning to them not to do the same thing.

The symmetry I have been describing breaks down here with the insertion of 2 images which have no parallel in the first half of the series, namely image 15 "The Hospital" and image 16 "Soldiers dying by the Roadside". In these images we see the detritus of battle in the early modern era. Soldiers who were sick or injured have been abandoned by the army to fend for themselves. Most face a period of beggary, a long period of painful convalescence, dependance on the charity of the church, or more likely death from infection and disease. We do not know where in the chronology these 2 images should come. It is plausible that first came the battle, then the pillaging by the soliders, and then their arrest and punishment. Images 15 and 16 could come at any time after the battle when they presumably received their injuries.

The overall theme of the sequence of images is of violence and the consequences of violence. Another is the role of the officers in these events. To begin with the officers: it is they who organize, raise and pay for the armies; they lead the army into battle; they organize official foraging parties and probably turn a blind eye if the soldiers go too far; they organize the arrest of the "criminal soldiers" and arrange to have their punishment and execution carried out in front of the other troops; they are then rewarded for their services by the king with medals and more money.

The groups who are engaged in acts of violence take the following forms: two organized armies fight on the battlefield; soliders from one side (possibly French) wage a kind of war pillaging and torturing the local peasants; a unit from the official army arrests some looters in the forest; the army uses judicial violence to execute the offending soldiers before their peers; an organized guerrilla band of peasants fight a battle against a unit of soldiers in the forest.

The consequences of violence are shown to take a number of forms as well. Images 15 and 16 show the consequences of battlefield violence for the injured. They are abandoned to their own devices, charity, and God's will. The peasants are the recipients of both offically sanctioned violence and "illegal" pillaging by the soldiers (images 4-8) whre we see horrific instances of looting, burning, torture, rape, and murder. Some of the soldiers are also the recipients of official violence in the form of the judicial punishments (torture and murder) they have to endure for their actions.

The final image 18 might also be seen in this light, as a "consequence" of all the violence which has come before. The officers are rewarded for their success on the battlefield, for exacting divine and royal punishment on those in the army who have transgressed, and for maintaining the honour and glory

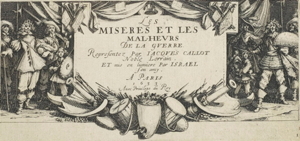

Plate 1: The Title Page

|

| 1. Title Page of "The Large Miseries and Misfortunes

of War" (1633) [See a larger version of this image (1275 px)] |

Description

There is a rectangular title above which are flags, banners and trumpets, below which tthere are the ools of war such as cannons, drums, swords. It is surrounded by officiers and page boys. To the right a soldier is crowned with a laurel ; he holds a sword in his right hand and a page his olding his helmet. To the left there is a crowned soldier with a cane while a page is holding his word and shield.

Quotation from Hugo Grotius, The Law of War and Peace (1625), Book 2, CHAPTER XXIV: Exhortations not to engage in a War rashly, tho’ for just Reasons.

[p. 497]: VII. We are also particularly to take Notice, that No Prince should ever make War upon another, who is of equal Strength with himself, on the Account of inflicting Punishment: For as the Civil Magistrate is supposed to have greater Power than the Criminal; so should he also who attempts to revenge Injuries by Arms, be stronger than him he attacks. And indeed it is not only Prudence, or Affection for his Subjects, that requires him to forbear engaging in a dangerous War, but very often Justice itself, that political Justice, which from the very Nature of Government does no less oblige a Prince to take Care of his Subjects, than it does the Subjects to obey their Prince. From whence it follows, (as Divines do with Reason teach us) that A King who undertakes a War upon frivolous Accounts, or to inflict some needless Punishments, and such as will involve his Subjects in a great Deal of Trouble, is obliged to make up the Damages they suffer thereby: For tho’ he cannot be accused with any Injury done to his Enemies, yet may there be a heavy Charge laid against him of wronging his Subjects, by plunging them in so much Misfortune and Misery for such Reasons. Livy says, that War is justifiable in those who are under a Necessity of being engaged in it, and that Arms are warrantable, when we have no Hopes but in our Arms. This is what Ovid desires when he says, Fast. 1.

Let the Soldier wear

No other Arms than what defensive are.

[p. 498]: X. 1. War, says Plutarch, is a most cruel Thing, and brings along with it an Ocean of Calamities and Violences. And St. Austin very wisely expresses himself thus, If I should attempt to speak of what Mischiefs and Massacres, what Misery and Hardships are occasioned by War, I should not only want Words, but not know when to put a Period to so large a Field of Discourse; but a Prince of Prudence and Thought (say they) will engage only in a just War; as if, when he reflects upon himself to be a Man, he will not, on the contrary, heartily lament, that there could ever be a Necessity of entring into any just Wars, because, unless he were satisfied of the Justice of them, he could not have had any Hand in them, and from hence it is plain, that a Prince of Prudence and Thought would, by his good Will, have no Wars at all; for it is the Injustice of the adverse Party that thrusts him into Wars, which are not only just, but sometimes inevitable; which Injustice every Man ought to bewail, as it is human Injustice, tho’ it did not oblige us to Arms. Whoever therefore considers with Regret, such great, such horrid, such barbarous Ills, must own that he is unfortunate, in being obliged to occasion them; but whoever can endure them, or make them the Objects of his Thoughts, without Grief and Emotion, that Wretch is still more miserable, because he counts himself happy in having cast off the Sentiments of Humanity. And in another Place he tells us, That the Good never engage in War but out of Necessity, whereas the Wicked take Delight in it. Maximus Tyrius tells us, τη̂ς τον̂ πολεμεɩ̂ν, &c. that Tho’there were no Injustice in a War, yet the very Necessity of it is deplorable. And again, ϕάινεται, &c. It is certain that good People make War only when compelled to, but the Wicked do it out of Choice.

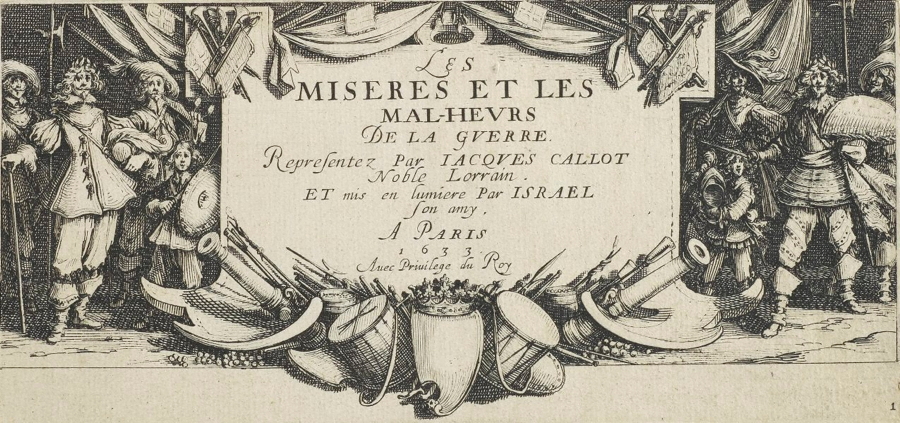

Plate 2: The Recruitment of Troops

|

| 2. The Recruitment of Troops (1633) [See a larger version of this image (1349 px)] |

Description

At the right there is a group of recruits with the hats under their arms, while an officer takes their details seated at a drum. Trhe troops are issued with an arquebus and then at the right an officer seated beneath a tree issues them with pay. Toops are drilled in two units, one in the centre and the other further to the right. Behind them are two units of cavalry. To the left the crennelated walls of a town can be seen. To the right are seen the tents of the camp.

Quotation from Hugo Grotius, The Law of War and Peace (1625): Book I, CHAPTER III: The Division of War into Publick and Private. An Explication of the supreme Power. A

[pp. 58-59]: But a publick War not Solemn, may be made both without any Formality, and against mere private Persons, and by the Authority of any Magistrate whatever. And indeed if we consider the thing without respect to the Civil Law, every Magistrate seems to have as much Right, in case of Resistance, to take up Arms in order to execute his Jurisdiction, as to defend the People committed to his Protection. But since by War the whole State is endangered, therefore it is provided, by the Laws of almost all Nations, that it be undertaken only by the Order or with the Approbation of the Sovereign. There is such a Law in Plato’s last Book de Legibus. And by the Roman Law he was reckoned guilty of High Treason, who without Commission from the Prince presumed to make War, list Soldiers, or raise an Army. And the Cornelian Law, enacted by L. Cornelius Sylla, says, without Commission from the People. In the Code of Justinian, there is a Constitution extant, made by Valentinian and Valens, thus, Let no Man use any Sort of Arms without our Knowledge and Permission. According to St. Austin, natural Order and the Peace of Mankind require, that the Matter should be so regulated in every State. This Law however ought to be understood with some Restriction, according to the Rules of Equity, as every Maxim is, however general the Terms may be in which it is expressed.

Plate 3: The Battle

|

| 3. The Battle (1633) [See a larger version of this image (1382 px)] |

Description

In the foreground cavalrymen fight with swords and pistols; towards the left, there are fallen men and horses on the ground. In the right background units of infantrymen fight. Behind them is a fort from which cannons fire sending smoke into the sky.

Quotation from Hugo Grotius, The Law of War and Peace (1625): Book II, CHAPTER I: Of the Causes of War; and first, of the Defence of Persons and Goods.

[pp. 128-29]: 3. What has been said touching the Justice of the Cause, ought to be observed in publick Wars, as well as in private. And Seneca with Reason complains of the Difference that is put in that respect, We punish, says he, Murders committed between private Persons: But do we act in like Manner with regard to Wars, and the Slaughter of whole Nations? It is a glorious Crime, Avarice and Cruelty reign there without Restraint.—Barbaritiesare authorised by the Decrees of the Senate, and Orders of the People; and what is prohibited in private Persons is enjoined by the State. ’Tis true, those Wars that are commenced by publick Authority have certain Effects of Right, as the Sentences of Judges: Of which hereafter: But are therefore not less criminal, if begun without a just Foundation. Thus was Alexander, for unjustly invading the Persians, and other Nations, deservedly reproached by the Scythians as a Highwayman, in Curtius, and by Seneca and Lucan18 branded with the opprobrious Names of Thief and Robber; by the Indian Magi he was taxed with criminal Ambition, and by a Pirate was told he was the same himself. So Justin, speaking of his Father Philip, said, that two Kings of Thrace were dethroned by the Fraud and Villany of a Thief. To which may be referred that Passage of St. Austin, What are Kingdoms without Equity, but so many great Robberies? So that of Lactantius, That Conquerors being dazzled with a vain Glory, miscall their Vices by the Name of Virtue.

Plate 4: The Recruitment of Troops

|

| 4. Scene of Pillage (1633) [See a larger version of this image (1382 px)] |

Description

There is a country inn showing a sign hanging on the left. Having stayed the night the troops pillage the inn and make off with all the property including linen, pots and pans, and mugs.Quotation from Hugo Grotius, The Law of War and Peace (1625): Book III, CHAPTER VI: Of the Right to the Things taken in War.

[p. 589]: 2. I shall begin with the Greeks, whose Custom Homer describes in several Places.

The Cities sack’d, the Spoils we did divide.

Achilles, in the same Poet, recounting the Cities which he had taken himself, says,

The worthiest Spoils with our own Hands we took,

And rich they were: We bore them instantly

To Agamemnon: He behind the Ships

Divided some; but far the most reserv’d.

For here we must look upon Agamemnon, partly as Head of all Greece at that Time, and so representing the whole Body of the People, by which Right he divided the Spoil, but with the Advice of his Council; and partly as General, and so out of that which was publick, he claimed a greater Share than others to himself. Therefore Achilles thus addresses Agamemnon,

I don’t pretend to equal Share with you,

When any Trojan Town we do subdue.

And in another Place Agamemnon, by the Advice of his Council, offers to Achilles, a Ship laden with Gold and Silver, and twenty Women, as his Share of the Spoil. When Troy was taken, as Virgil relates, Aeneid ii.

There Phoenix and Ulysses watch the Prey,

And thither all the Wealth of Troy convey:

The Spoils which they from ransack’d Houses brought,

And golden Bowls from burning Altars caught:

The Tables of the Gods, the purple Vests,

The People’s Treasure, and the Pomp of Priests.

[ Dryden. ]

So, long after, Aristides faithfully watched the Booty taken at the Battle of Marathon. And after the Battle at Plataeae, it was strictly forbidden, that any Man should take to himself any Part of the Spoil; and afterwards it was distributed among the People, according to every one’s Deserts. The Athenians being subdued, Lysander brought the Spoil into the publick Domain. And the Spartans had publick Offices, called Λαϕυροπω̂λαι, appointed to make Portsale of all the Prizes taken in War.

Quotation from Hugo Grotius, The Law of War and Peace (1625): Book I, CHAPTER I: What War is, and what Right is.

[p. 11]: 4. We must further observe, that this Natural Law does not only respect such Things as depend not upon Human Will, but also many Things which are consequent to some Act of that Will. Thus, Property for Instance, as now in use, was introduced by Man’s Will, and being once admitted, this Law of Nature informs us, that it is a wicked Thing to take away from any Man, against his Will, what is properly his own. Wherefore Paulus the Civilian infers, that Theft is forbid by the Law of Nature: Ulpian, that it is Dishonest by Nature: And Euripides calls it Hateful to GOD, as you may see in these Verses of Helena,

For the Deity abhors violence. It is his Will that all Men should remain in quiet Possession of their own Goods; but no Rapine is allowed. Riches unjustly acquired are to be renounced, for the Air and Earth are common to all Men, where, when they increase their Possessions, they are not to detain or take away what belongs to others. Helen. V. 909, &c.

Plate 5: Plundering a Large Farmhouse

|

| 5. Plundering a Large Farmhouse (1633) [See a larger version of this image (1351 px)] |

Description

We see the kitchen of a farmhouse into which armed men have burst. The inhabitants are cruelly tortured, women at the lower left are held by their hair, in the background centre a woman is held on a bed by 2 men, at the right through doorway another women is on a bed. At the entre left women are offering something to have her husband spared from a sword thrust. Ther is a man on the verge of death in the foreground left, there is a man suspended upside down over a fire in the background left, another man is tied hand and foot being executed by the sword. Other troops are seen generally looting.

Quotation from Hugo Grotius, The Law of War and Peace (1625): Book III, CHAPTER VI: Of the Right to the Things taken in War.

[p. 599]: 5. It is plain, by what I have said already, that the Romans, in the early Days of their State, did not allow so much to their Soldiers, but the civil Wars indulged them with more Liberty. Thus Equulanum was given to be plundered by the Soldiers, by Sylla. And Caesar, after the Battle of Pharsalia, gave Pompey’s Camp to be pillaged by the Soldiers; and Lucan introduces him speaking thus,

—— Super est pro sanguine merces,

Quam monstrare meum est; nec enim donare vocabo,

Quod sibi quisque dabit.

Let each reward himself, there lie the Spoils,

The Claim of War, and of illustrious Toils.

So the Soldiers of Octavius and Anthonyd plundered the Camp of Brutus and Cassius. In another civil War the Soldiers of Vespasian being led against Cremona, tho’ it was now near Night, made haste to storm the City, fearing lest otherwise the Wealth of the Cremonese should fall to the Share of their Commanders, and Lieutenant-Generals; for they knew well, says Tacitus, that The Plunder of a City taken by Storm belonged to the Soldiers, of one surrendered, to the Generals.

Plate 6: Destruction of a Convent

|

| 6. Destruction of a Convent (1633) [See a larger version of this image (1338 px)] |

Description

At the lower left nuns are being seized by horsemen. At the lower right foot soldiers surround a priest after having stolen his official robes. In the centre is a church with a door facing right with S. Maria above the doorway through which soldiers are carrying a trunk. The roof is on fire. At the left background the monastry itself is being pillaged and the booty is taken through a gate in the right background.

Quotation from Hugo Grotius, The Law of War and Peace (1625): Book I, CHAPTER IV: Of a War made by Subjects against their Superiors.

[p. 108, fn. 9]: The Authority of St. Ambrose is so far from being to our Author’s Purpose, that it may even serve to prove the contrary of what is here inferred from it, and shew how little we ought to depend on the Opinion of those old Doctors, vulgarly called the Fathers of the Church. The Conduct of the Person under Consideration sufficiently made it appear, that he thought Resistance allowable. Even two Passages, here quoted from him, were written on the Occasion of a signal Act of Resistance done by that great Saint. In giving the Fact, I shall borrow the very Words of Mr. Bayle’s Narration, formed on the Circumstances, admitted by Mr. Flechier, and Fa. Maimbourg. The former, in his Life of Theodosius: the latter in his History of Arianism. “On the Death of Gratian, the whole western Empire falling to Valentinian, his Brother, he made an Edict, at the Instance of Justina (his Mother) allowing the Arians the public Exercise of their Religion, and declaring all who should oppose the Execution of the said Order, Authors of Sedition, Disturbers of the Church’s Peace, Traitors, and worthy of Death. But as all the Churches were in the Power of St. Ambrose, the Arians attempted to take one in Defiance of his Authority. The Emperor going to take Possession of the Cathedral, found St. Ambrose with all his People as it were barricaded in it, who were resolved to defend both the Church and Pastor, to the last Drop of their Blood.” Hist. deTheod.Liv. III. num. 25, &c. “He invested the Church, and summoned St. Ambrose, by Virtue of the late Edict, to surrender it. The Bishop answered that he would never willingly quit it. A Remonstrance was made to the Emperor concerning the Difficulties of that Affair, and he was advised to extricate himself out of them by some Accommodation, because the Court was concerned in the Contest. The Emperor sent a very civil Message to St. Ambrose signifying, that he left him the quiet Possession of his Cathedral, and would be satisfied with a Church in the Suburbs; that it was reasonable that, as the Prince made some Abatement in his Demands for Peace Sake, the Prelate should do the same. But all to no Purpose; the People according to their Pastor’s Intentions, cried out with one Voice, that no Accommodation could be made in this Case, but that the Catholics were to be allowed the Churches which belong to them. Whereupon, a Party of Soldiers was sent by the Court, with Orders to make them selves Masters of the Church in the Suburbs; but the People took Arms and opposed them: The whole City was in a terrible Confusion: The Magistrates sent the Mutineers to Prison, and punished them severely; which only exasperated the rebellious Populace. Several Lords of the Court went to St. Ambrose, and desired he would appease the People, and put an End to the Disorder, since the Emperor demanded only one Church in the Suburbs, observing that it was but just that the Emperor should be Master in his own Dominions. The holy Archbishop replied, that the Emperor had no Right over the House of GOD; nor even over the House of one of his Subjects, which he could not seize by Force, without a Violation of Justice: That it was a Crime in a Bishop to surrender a Church, and Sacrilege in a Prince to seize on it: That, as for his Part, he did not raise the People, whom he exhorted to defend themselve sonly with Prayers and Tears; but when they were once spirited up to Rage and Fury, GOD alone could appease them. The Emperor and Empress, resolving to go in Person, and take Possession of old Basilic, sent a Party of Soldiers to put up the Imperial Canopy.

“St. Ambrose formally excommunicated all the Soldiers, who had the Insolence to seize the Churches. This Stroke surprized them so that they went over to his Party. The Emperor found himself reduced to the hard Necessity of fearing he should be abandoned by all his Subjects, and said to his chief Officers: I perceive that I am here no more than the Shadow of an Emperor, and that you are disposed to give me up to your Bishop, whenever he commands you. He then dispatched one of his Secretaries to St. Ambrose, with Instructions to ask him: Whether he was resolved on an obstinate Resistance of his Master’s Orders; and pretended to usurp the Empire, like a Tyrant, that Preparations might be made for disputing the Point by Force of Arms. The Saint answered, that he retained the Respect due to the Emperor, and revered his Power; but did not envy him it. He had indeed no Reason to envy him his Power, for his Authority was superior to that of the Emperor, as is evident from that Prince’s being at last obliged to leave Things as he found them, and recal the Edict published in Favour of the Arians. This now appears to me a real and formal rebellion. We see on one Side the Emperor’s Troops going to take Possession of a House, pursuant to the Edicts and Orders of a Sovereign: On the other a Mob assembled about their Archbishop, and resolved to spend the last Drop of their Blood in Opposition to the Execution of those Edicts. We see an Archbishop excommunicating Soldiers employed in the Execution of the Emperor’s Orders, and consequently dispensing Subjects from the Oath of Fidelity, which binds them to their Prince. We see a whole People taking Arms, even when an Emperor waves his Right. And we see all this happen, not under Circumstances, when a King requires his Subjects to do what is forbidden by the Law of GOD: For then it just to disobey; but at a Time, when the Prince makes a Demand of bare Walls, and permits Men to believe what they please, and serve GOD, according to their own Fancies. It is a surprizing illusion to imagine that a Building, designed for the Service of GOD, is the Inheritance of JESUS CHRIST, over which the secular Power has no Right, &c. General Criticisms on Mr. Maimbourg’sHistory of Calvinism. ” Lett. XXX. § 2, 3. p. 275, &c. Third Edit. It may be added that the Persons who then obstinately refused to allow the Arians and the Emperor a Church, were not furnished with any particular Privilege, by Vertue of which they could pretend their Sovereign had no Right to take it from them without their Consent. There was neither a fundamental Law of the State, nor a perpetual and irrevocable Concession, which secured them the Possession of it against the Will of their Sovereign.

Quotation from Hugo Grotius, The Law of War and Peace (1625): Book III, HAPTER V: Of Spoil and Rapine in War.

[pp. 574-75]: II. 1. Neither does the mere Law of Nations exempt sacred Things, that are consecrated, either to the true GOD, or to false Divinities, setting aside the Consideration of other Duties, (of which we will treat hereafter) from these Insults of War. Pomponius, the Civilian, tells us, When Places are taken from the Enemy, all Things therein cease to be sacred. Cicero, in his fourth Oration against Verres, observes, The Victory made all the sacred Things of Syracuse profane. The Reason of which is this, because those Things that are called sacred, are not of such a Nature, that the Moment they are consecrated to Religion, Men cannot more dispose of them, and make them serve to the Uses of Life, but they belong to the Publick, and are termed sacred on Account of the religious Use to which they were intended. For Instance, when one People submit themselves to another Nation, or King, they then deliver up what is called divine, as appears from the Form which we have elsewhere quoted, out of Livy; to which agrees that in Plautus’s Amphitryo,

They deliver up their City, Fields,

Altars, Houses, and themselves.

And again,

They deliver up themselves, and all they have

Divine and human.

2. Ulpian infers therefore, that there is a publick Right, even in Things that are sacred.7Pausanias tells us, that it was a common Custom with the Greeks and Barbarians, that Things sacred should be at the Disposal of the Conqueror. So when Troy was taken, the Image of Jupiter Hercaeus fell to the Share of Sthenelus: And he brings many other Examples of the like Custom. Thucydides, Lib. iv. It was a Law among the Grecians, that he who was Master of any Country, whether great or small, was also of the Temples. To which also that in Tacitus agrees, All the Ceremonies, Temples, and Images, in the Italick Towns, were at the Disposal, and under the Power of the Romans.

Plate 7. Plundering and Burning a Village

|

| 7. Plundering and Burning a Village (1633) [See a larger version of this image (1368 px)] |

Description

Armed soldiers pillage and burn a village including a small chapel in the upper centre (there is a cross to its left). The inhabitants and livestock are rounded up to be taken off as prisoners or booty. Livestock can be seen being herded at the lower right. A man can be seen being killed at the lower left under a tree. There is a grieviing wife who sits next to her dead husband in the centre foreground.

Quotation from Hugo Grotius, The Law of War and Peace (1625), Book I, Concerning Moderation in regard to the spoiling the Country of our Enemies, and such other Things.

[pp. 652-53]: III. 1. This will likewise happen, where the Possession is yet in Dispute, if there be great Hopes of a speedy Victory, of which those Lands and Fruits will be the Reward. Thus Alexander the Great, as Justin relates it, hindered his Soldiers from wasting Asia, declaring to them, that they should spare their own, and not destroy those Things, which they came to possess. Thus Quintius, when Philip overrun Thessaly, wasting it with Fire and Sword, exhorted his Soldiers (as Plutarch informs us) to march thro’ the Country, as if it were now entirely their own. Croesus advising Cyrus not to give up Lydia to be plundered by his Soldiers, tells him, You will not ruin my Cities, nor my Lands, they are no longer mine, they are now become yours, they will destroy what is yours.2. They who do otherwise, may apply to themselves the Words of Jocasta to Polynices in Seneca’s Thebais.

Patriam petendo perdis: Ut fiat tua,

Vis esse nullam: Quin tuae causae nocet

Ipsum hoc, quod armis uris infestis solum

Segetesque adultas sternis, & totos fugam

Edis per agros: Nemo sic vastat sua.

Quae corripi igne, quae meti gladio jubes,

Aliena credis.

[You ruin your Country whilst you seek it; to make it yours

Its Being you destroy; it defeats your Claim

To level, thus in Arms, the

ripen’d Harvest;

Is Fire and Sword, the Vengeance of an Enemy,

Applied to Spoil and Ravage what’s ones own?

No, our deadliest Foes we thus afflict.]

To the same Sense are the Words of Curtius, Whatsoever they did not waste, they owned to be their Enemies. Agreeable hereunto is that which Cicero, in his Letters to Atticus, says against the Design that Pompey had formed of taking his Country by Famine. Upon this Account Alexander the Isian blames Philip (in the 17th Book of Polybius) whose Words Livy has thus rendered: Philip dared not engage in a fair Field-fight, nor come to a pitch’d Battle, but flying away burned and plundered Cities; so that the Conquered rendered useless to the Conquerors what should have been the Recompence of Victory. But the old Kings of Macedon did not use to do so, they used to come to a fair Engagement, to spare Cities as much as possible, that they might have the more wealthy Dominion. For it is not a strange Conduct, to make War in such a Manner, that at the same Time, we dispute the Possession of a Thing, we leave nothing for ourselves but War.

Plate 8: Attack on a Coach

|

| 8. Attack on a Coach (1633) [See a larger version of this image (1363 px)] |

Description

Having probably lain in wait in the trees, some soldiers ambush a public coach. The coachman lies dead after being thrown from his seat. The travellers are forced to dismount to be robbed and probably killed. At the lower left they are shooting at a traveller on horseback. Behind that two more horseman are attacked, one is shooting back with his pistol. At the centre right a horseman is knocked from his horse and is being killed. At the lower centre a dead traveller on foot with his baggage is ransacked. Another foot traveller at the upper left is being robbed. At the lower right a sentry keeps lookout.

Quotation from Hugo Grotius, The Law of War and Peace (1625): Book III, CHAPTER I: Certain General Rules, shewing what, by the Law of Nature, is allowable in War; where also the Author treats of Deceit and Lying.

[p. 538]: XXI. As to the Manner of prosecuting a War, this Rule is also necessary,1 that whatsoever is unlawful for a Man to do, is also unlawful for another to force or persuade him to. As for Example, it is unlawful for a Subject to kill his Prince, or to deliver up a Town without the Consent of a Council of War, or to plunder his Countrymen. Therefore it is also unlawful to persuade him, who continues a Subject, to do so; for he that causes another to sin, always sins himself; neither is it enough to say, that it is lawful for him who tempts another to a base Act to do it himself, as to kill an Enemy, suppose; he may kill him, it is true, but not in such a Manner. And St. Augustine3 says true, It signifies nothing, whether a Man commit a Crime himself, or employ another to do it for him.

XXII. But it is another Thing if a Person shall freely offer himself, without any Persuasion to it; for it is not unlawful for us then to make use of him, as an Instrument, to do that which it is lawful for us to do. As we have proved already, by the Example of GOD himself. We receive a Deserter by the Law of War, said Celsus, that is, it is not contrary to the Law of War, to receive him, who quitting the Enemy’s Party, embraces ours.

Plate 9: Discovery of the Criminal Soldiers

|

| 9. Discovery of the Criminal Soldiers (1633) [See a larger version of this image (1347 px)] |

Description

In the middle of clearing regular soldiers led by an officer on horesback round up troops who have hidden in the shrubs and tress. Some are still hiding at the extreme left and right. The renegade troops were probably surprised and left their weapons and armour on the ground. A soldier gathers up weapons on the right. The prisoners have their hands tied and are led off to the right.

Quotation from Hugo Grotius, The Law of War and Peace (1625): Book II, CHAPTER XX: Of Punishments.

[pp. 410-11]: 4. But because we are apt to be partial in our own Cases or of those that belong to us, and to be hurried on too far by Passion, therefore as soon as many Families came and lived together in the same Place, that Liberty which Nature indulged them in of vindicating every Man his own Quarrel, was then taken away, and Judges appointed to determine all Controversies between Man and Man.

For when each angry Man avenged his Cause,

Judge to himself, and unrestrain’d by Laws;

The World grew weary of that brutal Strife,

Where Force the Limits gave to each precarious Life.

[ Lucret. ]

Thus Demosthenes against Conon, προεώραται ἐν τοɩ̂ς νόμοις, &c. It has been ordained by the Wisdom of our Ancestors, saith he, that all these Injuries should be redressed by the Law, and not by every private Man’s Passion and Caprice. So Quintilian, private Revenge is not only unlawful, but an Enemy to Peace; for there are Laws, Judges and Courts whereunto we may appeal, unless there be any who are ashamed to vindicate themselves by Law. So likewise the Emperors Honorius and Theodosius, For this Cause are Tribunals erected, and the Security of publick Laws provided, lest any Man should give himself the Liberty to revenge his own Quarrel. And King Theodorick: Hence sprung the sacred Reverence of Laws, that no Man migh trevenge himself by his own Hand, nor commit any Outrage upon his Enemy by the sudden Impulse of an impetuous Passion.

Plate 10: The Strappado

|

| 10. The Strappado (1633) [See a larger version of this image (1405 px)] |

Description

In a town square the renegade soldiers are tortured/punished by being suspended by their arms tied behind their back from a height and let fall suddenly to a metre above the ground - thus suffering dislocation and broken bones. At the lower right another soldier is being led out to suffer the same fate. Other soldiers and townspeople are watching (example for the soldiers). At the centre left four men have been chained together on a wooden horse (perhaps renegade officiers?) also watch.

Quotation from Hugo Grotius, The Law of War and Peace (1625): Book II, CHAPTER XX: Of Punishments.

[pp. 415-16]: 6. Moreover, in many Nations the plenary Right of Punishing, even with Death, remained in Masters over their Servants, and Parents over their Children, after the publick Laws were established. Thus in Sparta it was lawful for the Ephori to kill a Citizen, without any legal Prosecution.15 From what has been said we may plainly see, what the Law of Nature was concerning Punishments, and how long it continued.

X. 1. Let us now enquire whether this Liberty of punishing or revenging Injuries be not restrained by the Gospel. It is no Wonder indeed, as we saida elsewhere, that many Things which are permitted by the Law of Nature, and the Civil Law, should be forbidden by the divine Law, that being the most perfect of all Laws, and proposing a Reward above human Nature; and to obtain such a Reward, it is no Wonder if Virtues that exceed the bare Dictates of Nature are required. That those Corrections which leave no Infamy nor lasting Damage behind them, and in some Ages and Circumstances, are necessary, especially if they be inflicted by such Persons as human Laws permit so to do, as by Parents, Tutors, Masters, and Teachers, are no Ways repugnant to the Precepts of the Gospel, may be plainly enough gathered from the Nature of the Thing. For these Medicines of the Mind are altogether as innocent, as the disagreeable Potions given to a sick Person.

2. But the same is not to be said of Revenge. For as it tends only to satisfy the Resentment of the injured Person, it is so far from being agreeable to the Gospel, that it is not allowed of even by the Law of Nature, as we have shewn above. But the Law of Moses did not only forbid the Jews to entertain any Hatred against their Neighbour, that is, their Countrymen, Lev. xix. 17. but also to shew them some Sort of Kindness, even when they were Enemies, Exod. xxiii. 4, 5. Wherefore the Name of Neighbour being extended to all Mankind by the Gospel, it is plain that it is required of us, not only not to hate our Enemies, but even to do good to them, which is expressly commanded, Matt. v. 44. yet it was permitted to the Jews to seek Revenge for some great Injuries, not indeed by their own Hands, but by appealing to the Judge. But the Gospel takes away this Indulgence too, as is evident by the Opposition which our blessed Saviour puts between the Law and the Gospel. Ye have heard, saith he, that it hath been said, an Eye for an Eye, &c. But I say unto you, Matt. v. 38, 39. For tho’ what follows is properly concerning repelling of Injuries, and even this Liberty does in some Measure at least restrain, yet is it to be understood as much more strictly prohibiting Revenge; because it quite abrogates the old Indulgence,2 as only suitable to the Time of a more imperfect Dispensation; Not that a just Revenge is evil, but that Patience is much better; as Clement’s Constitutions have it, B. vii. Chap. xxiii.

Plate 11. The Hanging

|

| 11. The Hanging [See a larger version of this image (1360 px)] |

Description

Compare this panel with Billy Holliday's song "Strange Fruit" about the lynching of blacks. We see about 21 men in varying states of decomposition who are suspended from a tree as punishment for looting; again they are watched by the assembled troops. Camp tents in the background suggests that tbhis is perhaps taking place on a parade ground. A priest on a ladder against the tree offers a cross to the 22nd victim who is having a rope tied around his neck. To the left of the ladder another victim is on his knees before receiving benediction from a priest. Another victim is being guarded by troops on the left. Hats, cloaks and halberds lie on ground. To the right of the tree 2 victims pass the time by playing dice on a drum. At the lower right another victim talks with a monk.

Quotation from Hugo Grotius, The Law of War and Peace (1625): Book II, CHAPTER XX: Of Punishments.

[pp. 418-19]: 8. It remains that we say something of those Punishments that are inflicted, not for any private Advantage but for a publick Good; partly by putting to Death, or disabling the Criminal from doing any more Mischief, partly by deterring others by the Severity of the Example; that those Punishments were not abrogated by CHRIST, we have proved by an irrefragable Argument elsewhere; since, when he delivered those Precepts, he gave this Testimony of himself, That he did not destroy a Tittle of the Law. But the Law of Moses, which in these Cases certainly continued in Force as long as the Jewish State continued, strictly commanded their Magistrates to punish Homicides, and other great Crimes with Death, Exod. xxi. 14. Num. xxxvi. 31. Deut. xix. 13. And if the Precepts of CHRIST were consistent with the Law of Moses,20 as that Law required capital Punishments, well may they be consistent with human Laws, which do in this Respect imitate the divine.

XI. The Argument drawn from the Mercy of GOD declared in the Gospel, answered.XI. 1. Yet some there are, who, to maintain the contrary Opinion, alledge the great Mercy of GOD under the New Testament, which is to be imitated by all Men, and even by Magistrates themselves, as GOD’s Vice-gerents; which we grant to be true in some Measure, but yet that it is not to be extended so far as they would have it. For the great Mercy of GOD declared in the Gospel has Regard chiefly to Sins committed against the Law given to Adam, or against the Law of Moses, before the Promulgation of the Gospel, Acts xvii. 30. Rom. ii. 15. Acts, xiii. 38. Heb. ix. 15. For those which are committed afterwards, especially if they be persisted in with Obstinancy, are threatned with Judgments much more severe, than those of the Law of Moses, Heb. ii. 2, 3. x. 29. Matt. v. 21, 22, 28. Neither are they threatned with Judgments of the other Life only, but GOD often punishes such Crimes even in this, 1 Cor. xi. 30. Nor is Pardon for such Sins obtained,3 unless the Party does, as it were, punish himself, 1 Cor. xi. 31. by great Sorrow and Compunction, 2 Cor. ii. 7.

2. And they farther urge, that Magistrates, in Imitation of GOD, ought, at least, to pardon the penitent. But, besides that it is scarce possible for Men to discern which are true Penitents, and that if outward Shews, and Professions of Repentance were sufficient, no Man but would come off with Impunity, GOD himself doth not always remit all Kinds of Punishment, even to the true Penitent, as appears by the Example of David. As therefore GOD might remit the Punishment of the Law, that is, a violent or an otherwise untimely Death, and yet inflict grievous Punishments upon the Delinquents; so now, in like Manner, he may remit the Punishment of eternal Death, and yet, either punish the Sinner with an untimely Death himself, or be willing that he should be so punished by a Magistrate.

XII. 1. But others again condemn this Proceeding too; because, together with Life, all Opportunity for Repentance is cut off. But they themselves know very well, that good Magistrates always take special Care, that no Malefactor be hurried away to Punishment, before he has had a sufficient Time allowed him to confess his Sins in, seriously to detest and abhor them, and to make his Peace with GOD; and that GOD doth sometimes accept of such a Repentance, tho’ good Works being prevented by the Death of the Malefactor do not follow it, is plain from the Example of the Thief crucified with CHRIST. And if it be said, that longer Life might conduce much to a more serious and perfect Repentance; it may be answered, that Instances of those sometimes happen, to whom this Saying of Seneca may be justly applied, There is but one good Thing more, that we can offer you, which is Death: And that other Expression of the same Author, Let them cease to be wicked by the only Method they are capable of doing it. Which is what Eusebius, the Philosopher, had said before, Since they cannot be reformed by any other Means, let them, being thus freed from those Chains, bid Adieu to their Villanies.

Plate 12: The Firing Squad

|

| 12. The Firing Squad (1633) [See a larger version of this image (1398 px)] |

Description

On a training ground soldiers are being executed by firing squad. In the Centre 2 soldiers fire on blindfolded man tied to a post. Other victims lie dead on ground. At the Lower right another is led in prayer by a hooded monk. At the Upper left are the walls of a town. At the Upper right there are the tents of the camp and a hill with a fortress on top.Quotation from Hugo Grotius, The Law of War and Peace (1625): Book II, CHAPTER XXVI: Of the Reasons that justify those who under another’s Command engage in War.

[pp. 513-14]: IV. 7. And therefore Declarations of War used, as we shall shew you by and by, to be made publick, and the Reasons for it precisely expressed, that so all Mankind, as it were, might judge of the Justice of it. Prudence, (according to Aristotle) is indeed a Virtue peculiar to the Prince, but Justice belongs to every Man as he is a Man.

8. But Adrian’s Opinion, before-mentioned, seems absolutely to be relied on, if the Subject is not only in Suspence, but is, by probable Arguments, more enclined to believe that the War is unjust; especially if he be to take up Arms offensively, and not defensively.

9. And it is probable too, that an Executioner who is to put a condemned Malefactor to Death, ought to be acquainted with the Merits of the Cause, either by being present at the Trial, or by the Criminal’s Confession, in Order to satisfy himself that that person deserved Death; and this is still usual in some Places, and is what the Hebrew Law, Deut. xvii. 7. has an Eye to, when it injoins, that when a Malefactor is to be stoned, the Witnesses shall throw the first Stone.

V. 1. But if sufficient Satisfaction cannot be given to the Subjects, by explaining to them the Reasons of the War; it is a good Prince’s Duty to impose upon them rather some extraordinary Tax, than a personal military Service; especially when there are others who are ready to serve him, whose Intention, be it good or bad, a just King may make Use of, as GOD sometimes does of the Devil and the Wicked; and as a Man is in no Fault, if, when pressed with Poverty, and in extreme Want, he borrows Money from a griping Usurer.

2. Nay, tho’ the Justice of the War is not at all to be questioned, yet we cannot judge it reasonable that Christians should be forced to carry Arms against their Consent; since to abstain from War, even when it is lawful to fight, is reckoned a greater Piece of Sanctity, a Sanctity which has been constantly required from the Clergy, and from Penitents, and what is to all others recommended in several Manners. Origen makes this Answer to Celsus, upbraiding the Christians for their Refusal of going to War, To those who, being Strangers to our Religion, would command us to take up Arms for the State, and to kill Men, we thus reply, They who are your Idols Priests, and the Ministers of your reputed Gods, do keep their Hands undefiled, on the Account of their Sacrifices, that they may offer them up to your pretended Deities with innocent Hands, Hands with Murder unpolluted: Nor in War are your Priests ever listed. Now, if there be any Reason for this, then certainly you should reckon those, when others are in the War, to be, in their Way, under Arms too, who whilst, as the Priests and Worshippers of GOD, they preserve their Hands indeed pure from Blood, do yet with earnest Prayers contend with Heaven, both for them who are engaged in a just War, and for him who governs justly. In which Passage Origen calls every Christian a Priest, according to the Language of the Holy Writers, Rev. i. 6. 1 Pet. ii. 5.

VI. 1. But yet I am of Opinion that it may sometimes so fall out, that not only in a doubtful War, but even in one manifestly unjust, Subjects may lawfully take up Arms in their own Defence: For since an Enemy, tho’ carrying on a just War, cannot have any Right, truly or in Conscience, to put to the Sword such Subjects as are innocent, and have no Share in stirring up the War, unless it be in his own necessary Defence, or bya Consequence, and contrary to his Intentions; (for such Subjects are not liable to Punishment) it follows, that if it evidently appears, that the Enemy comes upon them with that Resolution of not giving the Subjects of his Enemy any Quarter, when, if he pleases, he may, then are those Subjects allowed, by the Right of Nature, to act in their own Defence, a Right which the Law of Nations has not deprived them of.

2. Nor can we even then say, that the War is just on both Sides: For the Question here is not about the War, but a certain particular Act of Hostility, which Act, tho’ his who has otherwise a Right to make a War, is yet unjust, and is therefore justly to be opposed and repelled.

Plate 13 The Stake

|

| 13. The Stake (1633) [See a larger version of this image (1377 px)] |

Description

Between two columns of troops a renegade soldier is burnt at the stake. Punishment seems to have come very quickly after the crime had been committed. Behind is the burning buildings of the village (church) ransacked by the renegades. A second victim is councilled by a monk on the right. In foreground a second stake is being prepared. There is a saw lying on the stake and a man is digging the post hole. There are bellows and a pot of coals to help get the next fire started.Quotation from Hugo Grotius, The Law of War and Peace (1625): Book III, Chapter: CHAPTER XI: Moderation concerning the Right of killing Men in a just War.

[pp. 646-47]: XVI. 1. Against these Rules of natural Right and Equity, some Exceptions use to be made, no way just, viz. If it be done by way of Retaliation; if by way of Terror, to frighten others; or if they have been obstinate in their Resistance. But no Man can look upon this enough to justify a Slaughter, who has seriously weighed what has been said before of the just Causes of killing Enemies; For there is no Danger from Prisoners, or from those who have actually surrendered themselves, or desire to do it. That they may therefore be justly put to Death, there ought to be a previous Crime, and that such a one, as an impartial Judge shall think Capital. And so we sometimes see Prisoners, and those that have surrendered themselves, put to the Sword, and their yielding upon Condition to have their Lives spared, not accepted; if they being satisfied of the Injustice of the War, have still continued in Arms; if they have abused the Conqueror with slanderous Reproaches, if they have broke their Faith, or any other Law of Nations, as the Privilege of Ambassadors; or if they have deserted their Colours.

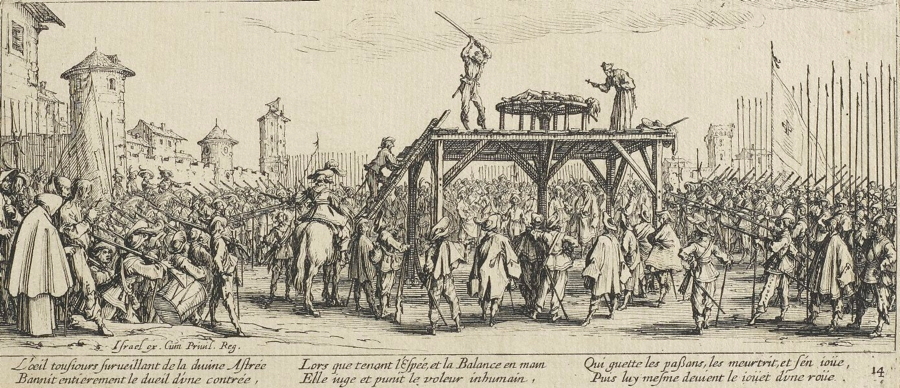

Plate 14: The Wheel

|

| 14. The Wheel (1633) [See a larger version of this image (1391 px)] |

Description

A similar scene, this time inside a walled town. Surrounded by troops is a platform with a wheel upon which is tied a victim. The executioner kills him by repeated blows with a heavy stick. A priest offers the cross at the right. At the lower left another victim with a cross in his hand waits with a monk.

Quotation from Hugo Grotius, The Law of War and Peace (1625): Book III, CHAPTER XVIII: Concerning Things privately done in a publick War.

[pp. 684-85]: 2. But they are mistaken, who think this arises only from the external Right of Nations; for if you barely consider that, as it is lawful for any one to seize on his Enemy’s Goods, (as we said before) so he may also kill his Enemy, for by that Right Enemies are accounted as if they were not real Persons. What Cato therefore adviseth, proceeds from the Roman military Discipline, which had a Law (as Modestinus observes) that he who disobeyed, should be put to Death, tho’ he had had good Success; but he was understood not to have obeyed, who without the General’s Command, fought the Enemy, as appears from the Example of Manlius. For if such a Thing were commonly permitted, the Soldier would abandon his Post of his own Head, or even Licentiousness might in Time proceed to such a Length, that the Whole Army or Part of it would rashly engage in dangerous Fights; which was by all Means to be avoided. Therefore Salust describing the Roman Discipline, says, They were oftener punished in War, who contrary to Orders had fought the Enemy, or kept the Field after sounding a Retreat. A certain Spartan, when just ready to kill his Enemy, stopt his Blow upon hearing the Retreat sounded, and gave this Reason, It is better to obey our Commanders, than to kill an Enemy. And Plutarch gives this Reason, why a Man dismissed from the Service, cannot kill an Enemy, because he is not obliged by the military Laws, which they that are to fight must observe. And Epictetus in Arrian relating the Action of Chrysantas, just mentioned, says, He thought it much better to obey the Orders of his General, than his own Will.

Plate 15: The Hospital

|

| 15. The Hospital (1633) [See a larger version of this image (1391 px)] |

Description

The courtyard of a hospital. Those maimed and crippled by war make their way to the entrance at the lower left where they are met by a priest/doctor. In the centre is a well next to which is a tub for washing. Cripples are doused with water. At the right a line of maimed are receiving food from a large pot.

Quotation from Hugo Grotius, The Law of War and Peace (1625): Book III, CHAPTER IV: The Right of killing Enemies in a solemn War; and of other Hostilities committed against the Person of the Enemy.

[pp. 565-66]: 2. Nor is this Licence of killing our Captives confined to any Time, by the Right of Nations, but it is restrained more or less in some Places, by the particular Laws of each State.

XI. We meet also with many Examples of Suppliants that have been slain, as by Achilles in Homer, of Mago, and Turnus in Virgil; which are not only recorded, but also justified by the Right of War. St. Augustine commending the Goths, for sparing Suppliants, and those that had fled for Refuge to Churches, acknowledges, That which by the Right of War they might do, they thought unlawful for them to do. Neither are they always received to Mercy, that beg it; witness the Greeks who served the Persians at the Battle of the Granicus. And the Uspenses in Tacitus begging Quarter, which (he says) the Conquerors denied, but let them die by the Law of Arms. Observe here also the Right of War confessed by that Author.

XII. Neither do they always find Mercy, thata surrender without any Condition, but are often slain, as the Princes of Pometia by the Romans, the Samnites by Sylla, thebNumidians, andcVercingetorix by Caesar. Nay, it was almost the constant Custom of the Romans on the Days of their Triumph to put to Death the Commanders of the Enemies, as Cicero tells us in his fifth Oration against Verres. Livy in his 28th Book, and elsewhere. Tacitus in his 12th Annal, and many others. And the same Tacitus informs us, that Galba caused the tenth Man to be killed of those, whom upon Submission he had received to Mercy; and Caecina upon the Surrender of Aventicum, caused Julius Alpinus to be slain, as the chief Promoter of the War; he left the rest to either the Mercy, or Cruelty of Vitellius.

XIII. 1.Historians sometimes set down the Reason of this Cruelty, of the Enemies, especially to Captives, and Suppliants, as either by way of Retaliation, or because of an obstinate Defence. But these are rather Motives, than justifying Causes, as I have distinguished in another Place. For just Retaliation (properly so called) is to be executed only upon the Person of the Offender (as has been already said, when we treated of the Communication of Punishment.) But on the contrary, in War this Right of Retaliation is often exercised upon the Innocent. This Custom is thus described by Diodorus Siculus, The Chance of War being equal on both Sides, neither Party can be ignorant, that if they be vanquished, they must suffer the same themselves, which they intend to their Enemies. And in the same Author, Philomelus the Phocian General, Diverted the Enemies from an insolent and cruel Revenge, by treating in the same manner such of them as fell into his Hands.

Plate 16: Dying Soldiers by the Roadside

|

| 16. Dying Soldiers by the Roadside (1633) [See a larger version of this image (1356 px)] |

Description

We see a road going through a village where on both sides are piles of straw and rubbish against which soldiers lie dying. At the lower right a priest attends to a dying soldier. In the centre others beg for food or money.

Quotation from Hugo Grotius, The Law of War and Peace (1625): Book II, CHAPTER I: Of the Causes of War; and first, of the Defence of Persons and Goods.

[pp. 132-33]: V. 1. But here ’tis necessary that the Danger be present, and as it were, contained in a Point. I grant, if a Man takes Arms, and his Intentions are visibly to destroy another, the other may very lawfully prevent his Intentions; for as well in moral as in natural Things, there is no Point but what admits of some Latitude: But they are highly mistaken, and deceive others, who admit that any Sort of Fear gives a Right to take away the Life of another. ’Tis very justly observed by Cicero, that one frequently commits Injustice, by attempting to hurt another, in Order to avoid the Evil which he apprehends from him. So Clearchus in Xenophon, καὶ γὰρ ὀίδα, &c. I have known many People moved either by some false Report, or by Suspicion, who for Fear of others, and to be before hand with them, have done most horrible Injuries to those, who never would have offered, nor ever designed to offer them any Hurt in the World. So Cato, in his Oration for the Rhodians, Shall we ourselves be first guilty of that which we alledge they intended to do? It was excellently said by Aulus Gellius, That a Gladiator’s Condition is such, that he must either kill or be killed; but human Life is not under such unhappy Circumstances, that we are necessitated to do an Injury to prevent the receiving one. And as Tully in another Place no less admirably expresses it, Whoever maintained, or to whom can it be allowed without exposing the Life of every one to the greatest Dangers, that a Man may lawfully destroy another, through a Pretence of Fear, lest the other should one Day kill him? To which this Passage of Euripides may be applied,

Ἐι γὰρ σ’ ἔμελλεν, &c.

Your Husband, say you, would have killed you: You should have staid till he actually attempted it. So Thucydides, What is to come is yet uncertain, nor should any one be so far transported with the Apprehensions of what may happen, as to engage in a declared Enmity, accompanied with present Acts of Hostility. The same Author, where he eloquently describes the Evils that Faction had brought upon the States of Greece, blames those People, because It was thought commendable in a Man to injure another first, for Fear of being injured himself. A very shameful Thing, as Livia calls it in Dion Cassius. Livy says, that By taking Precautions against what we apprehend from another, we give Occasion first to apprehend something from us, and we do to others the Injury we would repel, as if there were a Necessity either of doing or receiving Wrong. One may apply to such as act in that Manner, that of Vibius Crispus, so much celebrated by Quintilian, Who gave you an Authority thus to fear?

Quotation from Hugo Grotius, The Law of War and Peace (1625): Book II, CHAPTER XIX: Of the Right of Burial.

[pp. 394-96]: 6. Hence it is, that this good Office of Burial is said to be performed, not so much to the Man, that is, the particular Person buried, as to Humanity, that is, human Nature in general. Wherefore Seneca and Quintilian called Burial, A Piece of publick Humanity; and Petronius, A Piece of Humanity, derived down to us from our Ancestors. From all which Instances we may conclude, that Sepulture is not to be denied either to our private or publick Enemies. As to private Enemies, there is a fine Speech in Sophocles, about interring Ajax, where Ulysses thus says to Menelaus,

O Menelaus, do not sully all

That you have spoke, by injuring the Dead.

The Reason whereof is given by Euripides, in his Antigone, thus,

To ev’ry Mortal, Death’s the End of Strife;

For what Revenge can you desire more?

So in his Suppliants,

If the Argives did you wrong, they’re fallen;

And that’s Revenge enough for any Foe.

And Virgil,

With dead and vanquish’d Foes no War is made.

Which Verse the Author to Herennius has quoted, and gives this Reason for it, For that, saith he, which is the last and greatest of Evils has already befallen them. With whom agrees Statius.

We’ve been at War, ’tis true;

But Wrath and Hate by Death are done away.

The same Reason is given by Optatus Milevitanus, Tho’ your Passion was implacable while your Enemy lived, yet it should end with his Death; for he is now silent with whom you used to contend.

III. 1. And therefore it is agreed upon by all, that Burial is due, even to our publick Enemies. This, saith Appian, is a common Right in all Wars. And Philo calls it, The Commerce of War. Tacitus, Our very Enemies do not envy us Graves. Dion Chrysostome, This is a Right religiously observed, even amongst Enemies, tho’ their Enmity was irreconcileable before. Lucan, treating upon this Subject, saith, That funeral Rites are to be celebrated, even for Enemies. And Sopater, to the same Purpose, What War, saith he, can be so barbarous as to rob Mankind of its last Honour? What Enmity can extend the Resentment of Injuries so far as to dare to violate this Law? Whereunto we may add that of Dion Chrysostom, whom we have just now quoted; By this Law, saith he, the Dead are not accounted Enemies, nor does any Man extend his Anger and Revenge to the Bodies of the Slain.

Plate 17: The Peasants avenge Themselves

|

| 17. The Peasants avenge Themselves (1633) [See a larger version of this image (1338 px)] |

Description

Looting soldiers are burdened with their booty are in turn ambushed by peasants hiding in the trees (upper right and left). They attack with farm implements such as scythes, pitch forks and threshing sticks (middle centre) and stolen guns. At the lower right a soldier is stabbed with a pitchfork. At the lower centre soldiers are being stripped of their booty. At the lower left thre are dead animals. At the upper centre a man is suspended from a tree.

Quotation from Hugo Grotius, The Law of War and Peace (1625): Book III, CHAPTER XX: Concerning the publick Faith whereby War is finished; of Treaties of Peace, Lots, set Combats, Arbitrations, Surrenders, Hostages, and Pledges.

[p. 704]: XXXII. 1. Again, the Peace is said to be broken, not only when the whole Body of a State, but if any of the Subjects be forcibly invaded, unless upon Occasion of some new Cause of War. For Peace is made to the Intent that all the Subjects might live in Safety: The Treaty being an Act of the State for all the Members in general, and for each in particular. And if there be even a new Cause of War, it shall be lawful, tho’ the Peace subsists, for every one to defend himself and his Goods, against those that attack him. For it is natural (as Cassius says) to repel Force by Force. Therefore this Right cannot easily be thought to be renounced amongst Equals. But it shall not be lawful to revenge ones self, or by Force to recover what has been taken away, unless Judgment be first denied us. For this may admit of some Delay, but that of none.

Quotation from Hugo Grotius, The Law of War and Peace (1625): Book II, CHAPTER XX: Of Punishments.

[pp. 406-07]: 3. It is therefore contrary to Nature, for one Man to be pleased and satisfied with the Pain or Trouble he brings upon another, barely as it is Pain or Trouble. And therefore the weaker any one’s Reason is, the more prone he will be to Revenge. Juvenal,

But oh! Revenge than Life is sweeter far!

Thus think the Crowd, who, eager to engage,

Take quickly Fire, and kindle into Rage;

Who ne’er consider, but, without a Pause,

Make up in Passion what they want in Cause.

Not so mild Thales, nor Chrysippus thought,

Nor that good Man who drank the pois’nous Draught

With Mind serene; and could not wish to see

His vile Accuser drink as deep as he:

Exalted Socrates! Divinely brave!

Injur’d he fell, and dying he forgave,

Too noble for Revenge; which still we find,

The Pleasure of a weak and little Mind;

Degen’rous Passion, and for Man too base,

It seats its Empire in the Female Race.

[Creech.]

The same Observation is made by Lactantius: Foolish and unexperienced Men, saith he if they have any Injury offered them, are hurried on with a blind and inconsiderate Fury, to revenge themselves upon those that hurt them.

Quotation from Hugo Grotius, The Law of War and Peace (1625): Book II, CHAPTER XX: Of Punishments.

[p. 412]: The Law of Moses permitted the Kinsman of him, who was murdered, to kill the Murderer with his own Hand, if he could catch him out of the Places of Refuge; and the Jewish Commentators do well remark, that a Kinsman might execute the Law of Retaliation with his own Hand for the Person killed: but for himself, if any Violence was offered him, either by Wounds, Mutilation or otherwise, he was to appeal to the Judge; because it is more difficult to moderate our Revenge when it is excited by our own personal Pain. The like Custom of private Revenge for Murder, prevailed amongst the most antient Greeks, as appears from the Words of Theoclymenus in Homer, Odyss. XV. But Instances of this Custom are the most frequent in those Places, where they have no publick Judges to decide their Quarrels. Hence just Wars, as St. Austin testifies, are usually defined to be those, whereby Injuries are revenged. And Plato approves of carrying on a warlike Contest so long, Till the Offender shall be compelled to make the innocent Person, who has suffered by him, just Satisfaction.

Plate 18: The Distribution of Rewards

|

| 18. The Distribution of Rewards (1633) [See a larger version of this image (1379 px)] |

Description

After the war the prince thanks those (officers only it appears) who have performed their duty. At the upper centre seated on a throne with a sceptre in his left hand is prince. He is surrounded on both sides by gentlemen receiving their share of the spoils.

Quotation from Hugo Grotius, The Law of War and Peace (1625): Book II, CHAPTER XVII: Of the Damage done by an Injury, and of the Obligation thence arising.

[p. 374]: XX. 1. Kings and Magistrates are bound to make Reparation, if they do not use such Means, as they may and ought, to prevent Robberies and Piracy. For Neglect of which the Scyrians were formerly condemned by the Amphictyones. I remember I was asked the Question, concerning a Case that happened when our States had granted Commissions to several Privateers, some of whom had made Prizes on our own Friends, and deserting their native Country, roved about upon the Seas, and would not return, tho’ recalled, whether the States were bound to make Reparation, either for employing such lawless Men, or not taking Bail or Security of them, that they should not exceed their Commission. To which I answered, that the States were no farther obliged, than to punish or deliver up the Delinquents, if they could be taken, and to make over to the Persons injured, a Right to the Goods of these Pirates: Inasmuch as the States were neither the Cause of this Depredation, nor had any Hand in it, but had expressly prohibited the injuring of our Friends. That they were not in any wise obliged to require Security, since they may, even without express Commissions, give all their Subjects free Liberty to take as many Prizes as they can from their Enemy, as was formerly done: Nor can such a Licence be accounted the Cause of this Injury done to our Friends, since private Men may, without any such Licence, equip Ships and put out to Sea: Nor could it be foreseen that these Men would prove Rogues; nor can we altogether avoid the employing of dishonest Men; for then it would be impossible to raise an Army.