HUGO GROTIUS

The Rights of War and Peace (1625, 1738).

|

|

| Hugo Grotius (1583-1645) |

[Created: 16 March, 2022]

[Updated: 19 June, 2023 ] |

The Guillaumin Collection

|

This title is part of “The Guillaumin Collection” within “The Digital Library of Liberty and Power”. It has been more richly coded and has some features which other titles in the library do not have, such as the original page numbers, formatting which makes it look as much like the original text as possible, and a citation tool which makes it possible for scholars to link to an individual paragraph which is of interest to them. These titles are also available in a variety of eBook formats for reading on portable devices. |

Source

, The Rights of War and Peace, in Three Books. Wherein are explained, the Law of Nature and Nations, and the Principal Points relating to Government (London : W. Innys et al., 1738).http://davidmhart.com/liberty/OtherLiberals/Grotius/LawWarPeace/1738-edition/index.html

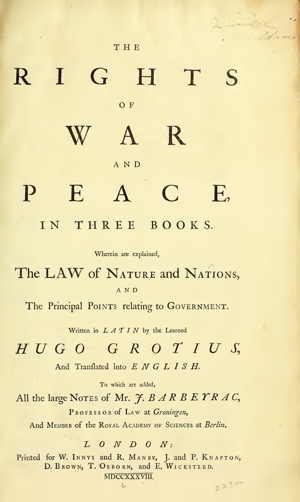

Hugo Grotius, The Rights of War and Peace, in Three Books. Wherein are explained, the Law of Nature and Nations, and the Principal Points relating to Government. Written in Latin by the Learned Hugo Grotius, and Translated into English. To which are added, all the large Notes of Mr. J. Barbeyrac, Professor of Law at Groningen, and Member of the Royal Academy of Sciences at Berlin. (London : Printed for W. Innys and R. Manby, J. and P. Knapton, D. Brown, T. Osborn, and E. Wicksteed, 1738).

This title is also available in a facsimile PDF of the original and various eBook formats - HTML, PDF, and ePub.

Editor’s Note: The section dealing with the “Passages of Scripture” mentioned in the book (pp. 758-61) and the very detailed Index (pp. 762-817) were not coded into HTML. These can be consulted in the facs. PDF version of the book if required.

This book is part of a collection of works by Hugo Grotius (1583-1645).

Table of Contents

Front Matter

- THE LIFE OF HUGO GROTIUS

- H. GROTIUS to His Most Christian Majesty LEWIS XIII. King of France and Navarre.

- THE PRELIMINARY DISCOURSE. Concerning the Certainty of Right in general; and the Design of this Work in particular.

- Endnotes for the Preliminary Discourse

THE RIGHTS OF WAR AND PEACE. BOOK I

- CHAPTER I. What War is, and what Right is.

- CHAPTER II. Whether ’tis ever Lawful to make War.

- CHAPTER III. The Division of War into Publick and Private. An Explication of the supreme Power.

- CHAPTER IV. Of a War made by Subjects against their Superiors.

- CHAPTER V. Who may lawfully make War.

- Endnotes for Book I

THE RIGHTS OF WAR AND PEACE. BOOK II

- CHAPTER I. Of the Causes of War; and first, of the Defence of Persons and Goods.

- CHAPTER II. Of Things which belong in common to all Men.

- CHAPTER III. Of the original Acquisition of Things; where also is treated of the Sea and Rivers.

- CHAPTER IV. Of a Thing presumed to be quitted, and of the Right of Possession that follows; and how such a Possession differs from Usucaption and Prescription.

- CHAPTER V. Of the Original Acquisition of a Right over Persons; where also is treated of the Right of Parents: Of Marriages: Of Societies: Of the Right over Subjects: Over Slaves.

- CHAPTER VI. Of an Acquisition (Possession or Purchase) derived from a Man’s own Deed; where also of the Alienation of a Government, and of the Things and Revenues that belong to that Government.

- CHAPTER VII. Of an Acquisition derived to one by Vertue of some Law; where also of succeeding to the Effects and Estate of a Man who dies without a Will.

- CHAPTER VIII. Of Such Properties as are commonly called Acquisitions by the Right of Nations.

- CHAPTER IX. When Jurisdiction and Property Cease.

- CHAPTER X. Of the Obligation that arises from Property.

- CHAPTER XI. Of Promises.

- CHAPTER XII. Of Contracts.

- CHAPTER XIII. Of an Oath.

- CHAPTER XIV. Of the Promises, Contracts, and Oaths of those who have the Sovereign Power.

- CHAPTER XV. Of publick Treaties, as well those that are made by the Sovereign himself, as those that are concluded without his Order.

- CHAPTER XVI. Of Interpretation, or the Way of explaining the Sense of a Promise or Convention.

- CHAPTER XVII. Of the Damage done by an Injury, and of the Obligation thence arising.

- CHAPTER XVIII. Of the Rights of Embassies.

- CHAPTER XIX. Of the Right of Burial.

- CHAPTER XX. Of Punishments.

- CHAPTER XXI. Of the Communication of Punishments.

- CHAPTER XXII. Of the unjust Causes of War.

- CHAPTER XXIII. Of the dubious Causes of War.

- CHAPTER XXIV. Exhortations not to engage in a War rashly, tho’ for just Reasons.

- CHAPTER XXV. Of the Causes for which War is to be undertaken on the Account of others.

- CHAPTER XXVI. Of the Reasons that justify those who under another’s Command engage in War.

- Endnotes for Book II

THE RIGHTS OF WAR AND PEACE. BOOK III

- CHAPTER I. Certain General Rules, shewing what, by the Law of Nature, is allowable in War; where also the Author treats of Deceit and Lying.

- CHAPTER II. How Subjects Goods, by the Law of Nations, are obliged for their Prince’s Debts: And of Reprisals.

- CHAPTER III. Of a just or solemn War, according to the Right of Nations, and of its Denunciation.

- CHAPTER IV. The Right of killing Enemies in a solemn War; and of other Hostilities committed against the Person of the Enemy.

- CHAPTER V. Of Spoil and Rapine in War.

- CHAPTER VI. Of the Right to the Things taken in War.

- CHAPTER VII. Of the Right over Prisoners.

- CHAPTER VIII. Of Empire over the Conquered.

- CHAPTER IX. Of the Right of Postliminy.

- CHAPTER X. Advice concerning Things done in an unjust War.

- CHAPTER XI. Moderation concerning the Right of killing Men in a just War.

- CHAPTER XII. Concerning Moderation in regard to the spoiling the Country of our Enemies, and such other Things.

- CHAPTER XIII. Moderation about Things taken in War.

- CHAPTER XIV. Of Moderation concerning Captives.

- CHAPTER XV. Moderation in obtaining Empire.

- CHAPTER XVI. Moderation concerning those Things which, by the Law of Nations, have not the Benefit of Postliminy.

- CHAPTER XVII. Of Neuters in War.

- CHAPTER XVIII. Concerning Things privately done in a publick War.

- CHAPTER XIX. Concerning Faith between Enemies.

- CHAPTER XX. Concerning the publick Faith whereby War is finished; of Treaties of Peace, Lots, set Combats, Arbitrations, Surrenders, Hostages, and Pledges.

- CHAPTER XXI. Of Faith during War, of Truces, of Safe-Conduct, and the Redemption of Prisoners.

- CHAPTER XXII. Concerning the Faith of inferior Powers in War.

- CHAPTER XXIII. Of Faith given by private Men in War.

- CHAPTER XXIV. Of Faith tacitly given.

- CHAPTER XXV. The Conclusion, with Admonitions to preserve Faith and seek Peace.

- Endnotes for Book III

[i]

THE LIFE OF HUGO GROTIUS

To look into the Manners of Antiquity, and recover the Memory of preceding Ages, is an Entertainment of the highest Pleasure and Advantage to the Mind, it establishes very lasting Impressions of Virtue in us, enlarges the Soul, and moves our Emulation to follow and excel the leading Characters before us; when we are tracing the Exploits of some Worthy of Old, with what Delight do we pursue him in every Circumstance of Action, we admire the Example, and transmit the Beauties of his Life into our own Conduct by Practice and Imitation; for the Mind of Man is of a searching Nature, very wide and extensive in her Speculations; and as she is blind to the Transactions of Futurity, so she receives a greater Lustre from the Reflection of Instances that are past, than from the Rules of Wisdom, or the Determination of the Schools: ![]() ιλοσο

ιλοσο![]() ία

ία ![]() κ πα

κ πα![]() αδειγμάτων, Philosophy from Example, in the Opinion of the Historian,Thucydides. advances human Life beyond the Power of Precept, or the Distinctions of Morality, it opens a large Scene for Observation, it displays all the Occurrences and Revolutions of Providence, how far Application and Industry improve the Abilities of the Soul, and offer us to the Notice of Mankind, and the Wonder of Posterity.

αδειγμάτων, Philosophy from Example, in the Opinion of the Historian,Thucydides. advances human Life beyond the Power of Precept, or the Distinctions of Morality, it opens a large Scene for Observation, it displays all the Occurrences and Revolutions of Providence, how far Application and Industry improve the Abilities of the Soul, and offer us to the Notice of Mankind, and the Wonder of Posterity.

This Life of GROTIUS is not writ with a Design to enlarge upon his Merit, or to adorn his Character, who has left such Illustrious Testimonies of his Learning, Zeal, and Piety, that the Letter’d World submits to his Authority, and reveres his Judgment so much, [ii] that his Name will be venerable to latest Ages: Our present Aim is only to reduce the Circumstances of his Life into such a Method as will shew us by what Steps and Degrees he attained to so high an Esteem, as to derive an Honour upon the Century he lived in, and to recommend him as a Pattern to succeeding Ages.

HUGO GROTIUS, in Dutch, de Groot, one of the greatest Men in Europe, was born at Delft the 10th of April, 1583; where his Family had been Illustrious between Four and Five Hundred Years. He made so early a Progress in his Studies, that he writ some Verses before he was nine Years of Age; and at Fifteen he had a great Understanding in Philosophy, Divinity and the Civil Law; but he was still better skill’d in Philology, as he made it appear by the Commentary he writ at that Age upon Martianus Capella, a very difficult Author. So prodigious was his Memory, that being present at the Muster of some Regiments, he remembered the Names of every Soldier there. In the Year 1598 he accompanied the Dutch Embassador, the famous Barnevelt, into France, where Henry IV gave him several Marks of his Esteem; he took there his Degree of Doctor of Law, and being returned into his Country, he applied himself to the Bar, and pleaded before he was Seventeen Years of Age; he was not Twenty four Years old when he was made Advocate-General; he settled at Rotterdam in 1613, and was Pensionary of that Town; he would not accept of that Employment, but upon Condition that he should not be deprived of it; for he foresaw that the Quarrels of Divines about the Doctrine of Grace, which formed already a thousand Factions in the State, would occasion many Revolutions in the chief Towns; he was sent into England in the same Year, by reason of the Misunderstanding between the Merchants of both Nations; he wrote a Treatise upon that Subject, and called it Mare Liberum, or a Treatise shewing the Right the Dutch have to the Indian Trade. He found himself so far engaged in the Affairs which undid Barnevelt, that he was arrested in August 1618, and condemned to perpetual Imprisonment the 18th Day of May 1619, and to forfeit his Estate; he was confined to the Castle of Louvestein the 6th of June in the same Year, where he was severely used for above 18 Months; from whence, by the Contrivance of Mary de Regelsberg his Wife, he made his Escape, who having observed that the Guards, being weary of searching a large Trunk full of Books and Linnen to be washed at Gorcum, a neighbouring Town, let it go without opening it as they used to do, advised her Husband to put himself into it, having made some Holes with a Wimble in the Place where the forepart of his Head was, that he might not be stifled. He followed her Advice, and was in that manner carried to a Friend of his at Gorcum; from whence he went to Antwerp in the usual Waggon, after he had crossed the publick Place in the Disguise of a Joyner, with a Ruler in his Hand. That good Woman pretended all the while that her Husband was [iii] very Sick, to give him time to make his Escape into a Foreign Country: But when she thought he was safe, she told the Guards, laughing at them, that the Birds were fled. At first there was a Design to Prosecute her, and some Judges were of Opinion she should be kept in Prison instead of her Husband; but by a Majority of Votes she was released, and praised by every Body, for having by her Wit procured her Husband’s Liberty. Such a Wife deserved not only to have a Statue erected to her in the Commonwealth of Learning, but also to be canoniz’d; for we are indebted to her for so many excellent Works published by her Husband, which had never come out of the Darkness of Louvestein, if he had remained there all his Lifetime, as some Judges appointed by his Enemies designed it.

He retir’d into France, where he met with a kind Reception at Court, and had a Pension assigned him; the Dutch Embassadors endeavoured to prepossess the King against him, but that Prince did not regard their Artifices, and gave a glorious Testimony to the Virtue of that Illustrious Refugee, and admired the Virtue of the Man, who being so ill used in his Country, never omitted an Opportunity to advance its Interest, and encrease its Grandeur. He applied himself very closely to Study, and to compose Books. The first he published after he settled in France, was An Apology for the Magistrates of Holland, who had been turned out of their Places. The contrary Party was very much displeased with this Treatise, they thought GROTIUS made it appear that they had acted against the Laws, and therefore they endeavoured again to ruin and defame him, but the Protection of the French Court secured him against their Attempts.

He left France after he had been there Eleven Years, and returned into Holland full of Hopes, by reason of a kind Letter he received from Prince Frederick Henry, who succeeded his Brother in that Republick; but his Enemies prevented the good Effects of that Letter, and therefore he was forced once more to leave his Country; he resolved to go to Hamburg, where he stayed till he accepted the Offers he received from the Crown of Sweden, in the Year 1634. Queen Christina made him one of her Counsellors, and sent him Embassador to Lewis XIII. Having discharged the Duties of that Employment about Eleven Years, he set out from France to give an Account of his Embassy to the Queen of Sweden; he went through Holland, and received many Honours at Amsterdam; he saw Queen Christina at Stockholm, and after he had discoursed with her about the Affairs he had been entrusted with, he most humbly begged of her, that she would grant him his Dismission. The Queen gave him no positive Answer when he asked leave to retire, which displeased some great Men, who were afraid that she would keep him in her Council: He perceived their Discontent, and was so pressing to obtain his Dismission, that it [iv] was granted him at last. The Queen, upon his Departure, gave him several Marks of her great Esteem for him. The Ship on Board which he embarked was violently tost by a Storm on the Coasts of Pomerania; GROTIUS being sick, and uneasy in Mind, continued to travel by Land, but his Illness forced him to stop at Rostock, where he died in a few Days, on the 28th of August 1645. His Body was carried to Delft to be buried among his Ancestors; he left behind him three Sons, and one Daughter. The Daughter was married to a French Gentleman called Mombas, who was very much talk’d of, on Occasion of a Trouble he was brought into soon after the French had passed the Rhine in the Year 1672. The eldest Son and the youngest pitched upon a Military Life, and died without being married. The second, whose Name was Peter de Groot, made himself illustrious by his Embassies. The Elector Palatine being restored to his Dominions by the Treaty of Munster, appointed him his Resident in Holland: He was made Pensionary of the City of Amsterdam in 1660, and discharged the Duties of that Place with great Ability for the Space of Seven Years. He was sent Embassador to the Northern Crowns in the Year 1668. At a Year’s End he went into France with the same Character, and acquitted himself in that Employment with great Dexterity and Wisdom. When the War was kindled 1672, he returned into his Country, and was deprived of his Office of Pensionary at Rotterdam, which he had enjoyed ever since his Return from his Embassy into Sweden: He was deprived of it during the Popular Tumults, which occasioned so many Alterations in the Towns of Holland. He retired to Antwerp, and then to Cologne, whilst the Peace was treating there, and acted for the Good of his Country as much as ever he could; and yet when he returned into Holland he was accused of a State Crime; the Cause was tried and he was acquitted: He retired into a Country-House, where he died at 70 Years of Age.

The Calumnies, maliciously dispersed by the Enemies of GROTIUS, about his Death, are irrefragably confuted by the Relation of the Minister who attended upon him when he was dying. The Minister, called John Quistorpius, was Professor of Divinity at Rostock. His Relation imports, “That he went to GROTIUS who had sent for him, and found him almost dying; that he exhorted him to prepare for Death, in order to enjoy a more happy Life, to acknowledge his Sins, and to repent of them; that having mentioned to him the Publican, who confessed himself a Sinner, and begged God’s Mercy, the sick Man answered, I am that Publican; that he went on and told him he should have Recourse to Jesus Christ, without whom there is no Salvation, and that GROTIUS replied, I place all my Hopes in Jesus Christ alone; that he repeated in a loud Voice a Prayer in High-Dutch, and that the sick Man said it softly after him with his Hands joined; that having ended, he asked him whether he understood [v] him, and his Answer was, I understood you very well; that he continued to repeat to him some Passages of the Word of God, which dying People are usually put in Mind of, and to ask him, Do you understand me? and that GROTIUS answered, I hear your Voice, but I do not understand every thing that you say; that with this Answer the sick Man lost his Speech, and expired soon after.” It were an absurd thing to call in Question the Sincerity of Quistorpius, nothing could move him to be false in his Account, and it is certain that the Lutheran Ministers were no less displeased than the Calvinists with the particular Opinions of GROTIUS, and therefore the Testimony of the Professor of Rostock is an authentick Proof; and if such Evidence is not sufficient in Matters of Fact, we make way for Scepticism, and it will be difficult to prove any thing. It is therefore an undeniable Case that GROTIUS being a dying, was affected like the Publican mentioned in the Gospel, he confess’d his Faults, he was sorry for them, and implor’d the Mercy of his heavenly Father; that he placed all his Hopes in Jesus Christ alone; that his last Thoughts were those that are contained in the Prayer of dying People, according to the Liturgy of the Lutheran Churches. The Result of which is, that those who say he died a Socinian, would be too gently used if they were only told, that they are guilty of a rash Judgment; they are Persons prejudiced against the Character of this Great Man, and therefore very unworthy of our Belief. Several People have wondered that his Grand-Children did not ask Satisfaction for this Injury done tohis Memory, and that they appeared less sensible in this Point, than Jansenius’s Relations upon slighter Calumnies; but some Persons highly approve their waving all Juridical Proceedings. There is a solid Answer to that Reflection upon our Author made by a Book entitled l’Esprit de Mr. Arnauld; and since the Accuser made no Reply to it, it is a plain Sign he has been convicted of Calumny. The Apologist for the Character of GROTIUS begins thus, “ But, Sir, what that Author and Father Simon say of GROTIUS, is nothing, if compared to what the nameless Author of the scandalous Libel intitled l’Esprit de Mr. Arnauld says of him; it is true, he slanders every Body in that Book, and the manifest Lies that are in it, ought to make one disbelieve every thing else; but because some are so weak, as to be imposed upon by his bold way of speaking, because some of those to whom you shew my Letters, entertain an ill Opinion of GROTIUS upon that Account, you will give me leave to undeceive them. Perhaps they will not be displeased to find an Author, for whom they have so great an Esteem, guilty of the most horrid Calumny that ever was; this will teach them, that one ought to suspect those who appear so zealous for Truth, and that sometimes a prodigious Malice and Detraction are concealed under the zealous Pretence of defending the Church of God. Afterwards the Apologist examines the four Accusations one after another; I shall not dwell on what [vi] he says upon the first Head, viz. That GROTIUS was a violent Arminian. GROTIUS, says our Author, in the second Place, was a Socinian, as appears from his enervating the Proofs of Christ’s Divinity. Sir, desire your Friends to read GROTIUS’s Annotations upon the Passages of St. Mark and St. John which I have mentioned to you, and if they do not say that it is an abominable Calumny, I am willing to be accounted a most wicked Calumniator. See also the DXLVIIIth Letter among the Literae Ecclesiasticae & Theologicae.” I should be too long should I mention what he says upon the third Head, I shall only set down this Passage out of it, “When Mr. Arnauld says something that is injurious to the Reformed, the Author of the Libel exclaims violently against him, and Mr. Arnauld is then an unsincere Man, an unfair Accuser, an Infamous Calumniator; but when he says something that may serve this Satyrical Writer to inveigh against those whom he hates, every thing is then right, it serves him to fill up his Page, and to prevent his being placed among the little Authors. ”

I must not forget that Mr. Arnauld blames the Lutheran Minister for not asking GROTIUS in what Communion he would die, this is a material Thing, says Mr. Arnauld, “with respect to a Man who was known to have had no Communion a long time with any Protestant Church, and to have confuted in his last Books most of the Doctrines that are common to them. Whereupon the Apologist says, that Mr. Arnauld and the Author of the Libel do wrongly fancy, that a Man has no Religion when he joins with none of the Factions that condemn Mankind, and each of which pretends to be the only Church of Christ. GROTIUS abstained from communicating with the Protestants, as well as with the Papists, because the Communion, which was appointed by Christ as a Symbol of Peace and Concord among his Disciples, is accounted in those Societies a Sign of Discord and Division. ”—Quistorpius acted the Part of a wise Man in not asking him what Communion he would die in, since he saw him dying in the Communion of Jesus Christ, by Virtue of which we are saved, and not by Virtue of that of the Bishop of Rome, or of the several Protestant Societies.

Without enquiring whether Quistorpius was in the Right or the Wrong for not asking such a Question, we observe, that a Man who believes the Fundamental Doctrines of Christianity, but forbears receiving the Communion, because he looks upon that Action as a Sign that one damns the other Christian Sects, cannot be accounted an Atheist, but by one who has forgot the Notions of Things or Definitions of Words; nay, we go farther, and maintain it cannot be denied that such a Man is a Christian; we allow you to say, that his believing all the Sects that receive the Gospel to be in the way to Salvation is an Heresy; we allow you to assert, that it is a pernicious and dangerous Doctrine; notwithstanding which, can it be said that [vii] those who believe that Jesus Christ is the Eternal Son of God, coessential and consubstantial with the Father, that he died for us, that he sits at the right Hand of God his Father; that Men are saved by Faith in his Death and Intercession; that one ought to obey his Precepts, and repent of one’s Sins, &c. we say, can it be affirmed that such People are not Christians? No Man of Sense can affirm it; but none would be more unreasonable in affecting such a thing than the Author of l’ Esprit de Mr. Arnauld, since he published another Book, wherein he shews that all those who believe the Fundamental Points, belong to the true Church, whatever Sect they may be of. We omit several other Maxims advanced by him, whereby it appears, that one may be saved in all Religions; we only mention such Doctrines as he cannot deny, and according to which he ought to acknowledge, that GROTIUS, who believed the Fundamental Doctrines, without approving Calvinism or Popery, &c. in every thing, was a Member of the true Church.

We suppose that what has been delivered may be of sufficient Force to overthrow the Calumnies that have been raised against our Author, in respect to his Principles in Religion; we shall now take a short Survey of the most eminent Books that were published from him.

During his Stay at Paris, before he was Embassador of Sweden, “he translated into Latin Prose his Book concerning the Truth of the Christian Religion, which he had writ in Dutch Verse, for the Use of the Seamen who travelled into the Indies, that they might have some Diversion in singing such a pious Poem.” Thus du Maurier speaks of it; but he is very much to blame for giving such a mean Notion of the Author’s Design, for GROTIUS aimed at a nobler End; he had a Mind to enable the Dutch, who travel to the Indies, to promote the Conversion of the Infidels; this is the Character he gives of it himself, My Resolution was to do something of Advantage to all my Countrymen, but especially for Seamen, that in all their Leisure they have Aboard, they may use their Time with Profit to themselves, and not loiter away their Hours as some do. And therefore beginning with a Panegyrick upon my own Nation, which infinitely excels all others in this Art; I encouraged them, that they would improve their Art, not only for their Benefit and Gain, but that they would regard it as the Mercy of Heaven, and use it for the propagating of the Christian Religion. It is an Excellent Work, and the Notes upon it are very learned. It was translated into English, French, Dutch, German, Greek, Persian, and Arabick; but we do not know whether all those Translations have been published; the Greek was not printed in the Year 1637. In the Year following GROTIUS mentions the Persian Translation only, as a Book which the Pope’s Missionaries had a Mind to publish. My Book, says he, concerning the Truth of the Christian Religion, that is accounted Socinian by some, is so far from having that Character here, that it is to be turned by the Pope’s Missionaries into the Persian [viii] Tongue, to convert, by the Favour of God, the Mahometans who are in that Kingdom. In the Year 1641, an Englishman, who had translated that Book into Arabick, was desirous his Translation should be printed in England. There came a very learned Englishman to me within these few Days, says he, who lived a long time in the Turkish Dominions, and translated my Book of the Truth of the Christian Religion into Arabick, and will endeavour, if he can, to have it published in England: He thinks no Book more profitable, either to instruct the Christians of those Parts, or to convert the Mahometans that are in the Turkish, Persian, Tartarian, Punic, or Indian Empire. That Translation made by the famous Dr. Edward Pocock, was printed at London in the Year 1660. There are three German Translations of that Work, two in Prose, and one in Verse, and two French Translations in Prose.

GROTIUS writ an History of the Low-Countries; it contains an Account of what happened in the Netherlands from the Departure of Philip II. It is divided into Annals and History, the Annals comprehend five Books; the History contains eighteen, and begins in the Year 1588. Casaubon, who had read something of it in the Year 1613, speaks well of it in a Letter written from London to Thuanus. The Judgment of the Author of the Parrhasiana runs thus, “ We may add to Polybius, a famous Historian among the Moderns, who though he had been a Sufferer by the Injustice of a great Prince, relates his noble Actions as carefully as any other Historian, and speaks of him according to his Merit, without saying any thing, whereby it may appear that he had Reason to complain of him; I mean the incomparable HUGO GROTIUS, who speaks in his History of the Netherlands of Prince Maurice de Nassau, as if he had never been ill treated by him; this is a remarkable Instance of Impartiality, which shews that it is not impossible to overcome one’s Passion, and speak well of one’s Enemies, as several People fancy, who judge of others by themselves. ” The Author who observes this fine Passage in GROTIUS’s History, did it not out of Flattery, for he blames him afterwards for a thing that deserves to be blamed; he does not approve GROTIUS’s Style, and shews thereby that he is a Man of a good Taste. “None,” says he, “of those who spoke well at Athens, and at Rome, expressed himself so obscurely in Conversation, as Thucydides and Tacitus did in their Histories; doubtless they had a Mind to raise themselves above common Use, and thereby they fell into that Obscurity for which they are justly reproved. It cannot be denied they have an affected Style, and that they hoped to recommend their Histories as it were by a manly Eloquence, whereby it seems that many things are expressed in few Words, and raised above the Capacity of the Vulgar; I cannot apprehend why some learned Men undertook to imitate them, as HUGO GROTIUS, and Dionysius Vossius in his Translation of Rheide’s History, and [ix] how they could relish such a Style; for certainly good Thoughts need not be obscure to be approved by good Judges; and when a Reader is obliged to stop continually, in order to look for the Sense, he does not think himself in the least obliged to an Historian who gives him the Trouble; this is the Reason why some Histories, though excellent as to the Matter, are read by few People; whereas if those Historians designed to write for the Instruction of those who have a sufficient Knowledge of the Latin Tongue to read a History with Pleasure, they should endeavour to make themselves easily understood, and useful to as many People as ever they could. The more a History deserves to be read by reason of the Events contained in it, the more it deserves to be of a general Use; the Authority of the Ancients who neglected the Clearness of the Style, cannot justify the Moderns, who have imitated them contrary to the Reasons I have mentioned, or rather contrary to good Sense. There is nothing in Tacitus that less deserves to be imitated, than his too concise, and consequently obscure Style; I am sorry GROTIUS was one of those who did not avoid it, it makes the Translation of his Writings more difficult, and his Thoughts more obscure.”

But his Book Of the Rights of War and Peace was the Masterpiece of his Works, and therefore deserves a more particular Account; it was printed at Paris in 1625, and dedicated to Lewis XIII. “King Gustavus of Sweden having read and admired it, resolved to make use of the Author, whom he took to be a great Politician by reason of that Work; but that Prince having been killed at the Battle of Lutzen in the Year 1632, Chancellor Oxenstern, according to his own Inclination, and the Design of the late King Gustavus, nominated him to be sent Embassador into France. ” Colomies says, “It is believed that GROTIUS exhausted his Parts upon that Book, and that he might have said of it what Casaubon said of his Commentary upon Perseus, in a Letter to Mr. Perillan his Kinsman, which is not printed, in Perseo omnem ingenii conatum effudimus; and indeed that Work of GROTIUS is an excellent Piece, and I do not wonder that it has been explained in some German Universities.”—Here follows the Judgment which M. Bignon, that unblamable Magistrate, makes of that Book in a Letter to GROTIUS, dated the 5th of March, 1633. “I had almost forgot,” says he, “to thank you for your Treatise De Jure Belli, which is as well printed as the Subject deserves it; I have been told that a great King had it always in his Hands, and I believe it is true, because a very great Advantage must accrue from it, since that Book shews, that there is Reason and Justice in a Subject, which is thought to consist only in Confusion and Injustice; those who read it will learn the true Maxims of the Christian Policy, which are the solid Foundations of all Governments; I have read it again with a wonderful Pleasure.” They did not make the [x] same Judgment of it at Rome, where it was placed among prohibited Books the 4th of February 1672. M. Chauvin’s Memorial concerning the Fate and Importance of that Work is so curious, that we cannot forbear transcribing some things out of it. It informs us that GROTIUS undertook to write that Book at the Solicitation of the famous Peireskius. He himself says so, in a Letter he writ to him, when he presented him with the Copy of that Work. “The Subject of it was thought to be so important and useful, that it gave Occasion to make a particular Science of it; for the Explication of which, some Professors have been appointed on purpose in the Universities. Charles Lewis, Elector Palatine, did so highly value that Book, that he thought fit it should serve as a Text to the Doctrine concerning the Right of Nature, and the Law of Nations, and in order to teach it he appointed M. de Puffendorf in the University of Heidelberg; and in Imitation of that Prince, the like Settlements have been made in other Universities. It does not appear that any Body criticized upon this Work of GROTIUS during his Lifetime”; but when he was dead it occasioned many Disputes, and was published over all the World of Letters, and commented upon by the most learned of all Nations. It came out at last, cum Notis Variorum, by which means our Author, within 50 Years after his Death, obtained an Honour, which was not bestowed upon the Ancients till after many Ages.

Thus have we given the History of this great Man, taken from the best Accounts that have contributed to derive his Memory to our Times; but as an Improvement of his Character receive the Testimony of Salmasius, one of his Enemies, in a Letter to him, You have laid but a small Obligation upon the Cardinals, and upon myself likewise, by bestowing a Title upon me, which is peculiar to the most eminent GROTIUS; for why should I not call him so, whom I had rather resemble, than enjoy the Wealth, the Purple, and Grandeur of the Sacred College?

[xi]

H. GROTIUS

to

His Most Christian Majesty

LEWIS XIII.

King of France and Navarre.

This Book presumes, most illustrious Prince, to in title it self to Your great Name, from a Confidence, not of itself, or its Author, but of the Subject Matter of it, which is Justice; a Virtue in so distinguishing a Manner Yours, that by it, both from Your own Merits, and the general Consent of Mankind, You have acquired a Title worthy so great a King, and are now every where known by the Name of JUST, no less than that of LEWIS. It was the Height of Glory to the Roman Generals, to be sirnamed from some of their conquered Countries, as Crete, Numidia, Africa, Asia, and the like. But how much more glorious Your Sirname, by which you are declared the irreconcileable Enemy, and perpetual Conqueror, not of any Nation or Man, but of Injustice? It was esteemed a great thing among the Egyptian Kings, for one of them to be stiled, the Lover of his Father, another the Lover of his Mother, another of his Brother. But how far short these of Your Name, which comprehends not only those, but every thing else that can be conceived beautiful and virtuous? You are JUST, as you honour the Memory of the great King your Father by imitating him: JUST, as You instruct your Brother by all imaginable Methods, but none more than that of Your own Example: JUST, as You procure the greatest Matches for Your Sisters: JUST, as You revive the Laws almost dead, and, to the utmost of Your Power, oppose the growing Wickedness of the Age: JUST, but at the same time Merciful too, as You deprive Your Subjects, whom the Ignorance of Your Goodness had caused to transgress the Bounds of their Duty, of nothing but the Liberty of offending, nor use any Violence to those who differ from You in Matters of Religion: JUST, and at the same time Compassionate, as you relieve by Your Authority oppressed Nations, and distressed Princes, and controul the exorbitant Power of Fortune. Which singular Beneficence in You, as near the Divine as Human Nature can admit, obliges me even in this publick Address to return You my private Thanks. For as the coelestial Bodies not only influence the great Parts of the World, but also suffer their Virtues [xii] to be communicated even to every individual Animal; so you, like a Star of most benign Influence to the Earth, not contented to have raised up dejected Princes, or given Succour to Nations, have condescended to give Protection and Comfort to me also, when illtreated by my Native Country. To Your publick Actions You have, to compleat the Measure of Justice, added such Innocence and Sanctity of Life, as deserves the Admiration, not of Men only, but of the blessed above. For who of the meanest People, or even of those who have sequestred themselves from the Conversation of the World, attains to that Perfection of Purity and Virtue, as you whom the Splendor of Fortune exposes daily to innumerable Charms of Vice? But how great is it to attain that in a multiplicity of Business, in a Crowd, in a Court amongst so many so various Examples of Vice, which others scarce are able, often are not able to do in Solitude? This is to merit the Name not of JUST only, but of Saint also, and that in this Life, which the Piety of the Age attributed to your Ancestors Charles the Great, and Lewis, only after their Deaths: This is to deserve the Title of most Christian, not by Descent, but your own proper Right. But as there is no part of Justice which does not belong to You, so that which concerns the Subject of this Book, viz. the Affairs of Peace and War, is properly Yours, as you are a King, and especially as King of France. Vast is Your Dominion, which extends from Sea to Sea, and comprehends so many spacious and happy Provinces; but it is a greater Dominion than this, not to desire others Dominions. Worthy is this of Your Piety, worthy of Your high Pitch of Grandeur, not to attempt the Invasion of any Man’s Right by Force of Arms, or the Alteration of ancient Limits; but together with War, to carry on Negotiations of Peace; nor to begin it, but with a Desire of bringing it to a speedy Conclusion. When it shall please God to call You to his Kingdom, which alone is better than that which You now possess, how becoming, how glorious, how joyful to the Conscience will it be for You to be able to say with Boldness; This Sword, received from thee for the Safeguard of Justice, I restore again pure, innocent, stained with no Man’s Blood rashly shed? Thus it shall be, that the Rules which we now seek for in Books, shall hereafter be learned from Your Actions, as the most perfect Pattern. Which thing itself, though of great Importance, yet the Christian World presumes to require something still greater from you; that is, that Wars every where ceasing, Peace may be restored, not only to Civil States, but to the Churches; and our Age submit itself to be modelled after the Pattern of the Apostolical Age, in which all unanimously acknowledge the Christian Faith to have been true and uncorrupted.

The Minds of Men, now grown weary of Dissention, are encouraged to hope for this, as the Effect of the Friendship lately contracted, and by the happy Marriage of Your Sister confirmed, between You and the King of Great Britain, a Prince eminent for his great Wisdom and ardent Love for the Peace of the Church. A Work indeed of vast Difficulty, by reason of the growing Animosity of Parties: But of two such great Kings nothing is Worthy but what is Difficult, and to all others impracticable. The God of Peace and Justice grant to Your Majesty, most Just and Peaceable Prince, together with all other Happiness, the Honour of accomplishing this great Work. MDCXXV.

[xiii]

THE PRELIMINARY DISCOURSE. Concerning the Certainty of Right in general; and the Design of this Work in particular.

I. The LAW of Nations.I. The Civil Law, whether that of the Romans, or of any other People, many have undertaken, either to explain by Commentaries, or to draw up into short Abridgments: But that Law, which is common to many Nations or Rulers of Nations, whether derived from Nature, or instituted by Divine Commands, or introduced [1] by Custom and tacit Consent, few have touched upon, and none hitherto treated of universally and methodically; tho’ it is the Interest of Mankind that it should be done.

Of War and Peace.II. Cicero [1] rightly commended the Excellence of this Science, in the Business of Alliances, Treaties, Conventions between States, Princes, and foreign Nations, and in short, in all Affairs that regard the Rights of War and Peace. And Euripides prefers this Science before the Knowledge of all other Things, whether Divine or Human, when he makes Helen say thus to Theonoe:

[2] ’Twould be a base Reproach

To you, who know th’ Affairs present and future

Of Men and Gods, not to know what Justice is.

Some think Interest alone the Rule of Justice.III. And indeed this Work is the more necessary, since we find some, both in this and in former Ages, so far despising this Sort of Right, as if it were nothing but an empty Name. The Saying of Euphemus in Thucydides is almost in every ones Mouth, [1] To a King or Sovereign City, no- [xiv]thing is unjust that is profitable. Not unlike to which is this, [2] That amongst the Great the stronger is the juster Side; and, That no State can be governed [3] without Injustice. Besides, the Disputes that happen between Nations or Princes, are commonly decided at the Point of the Sword. Now, it is not only the Opinion of the Vulgar, that War is a Stranger to all Justice, but many Sayings uttered by Men of Wisdom and Learning, give Strength to such an Opinion. And indeed, nothing is more frequent than the mentioning of Right and Arms, as opposite to one another. Thus Ennius, [4]

They have recourse to Force of Arms, not Law.

And Horace [5] thus describes the Fierceness of Achilles:

Laws as not made for him he proudly scorns,

And every Thing demands by Force of Arms.

Another Latin Poet [6] introduces another Conqueror, who entering upon War, speaks in this Manner,

Now, Peace and Law, I bid you both farewell.

Antigonus, [7] though old, laughed at the Man, who presented him with a Treatise concerning Justice, at the very Time he was besieging his Enemies Cities. And Marius said [8] he could not hear the Voice of the Laws for the [9] clashing of Arms. Even the [10] modest bashful Pompey [11] could have the Face to say, Can I think of Laws, who am in Arms?

IV. Among Christian Writers we find many Sayings of the same kind; let that of Tertullian suffice for all; [1] Fraud, Cruelty, Injustice, are the proper Business of War. Now they that are of this Opinion, will undoubtedly object against me that of the Comedian,

[2] You that attempt to fix by certain Rules

Things so uncertain, may with like Success

Strive to run mad, and yet preserve your Reason.

The Existence of Right asserted against the Objections of Carneades.V. But since it would be a vain Undertaking to treat of Right, if there is really no such thing; it will be necessary, in order to shew the Usefulness of our Work, and to establish it on solid Foundations, to confute here in a few Words so dangerous an Error. And that we may not engage with a Multitude at once, let us assign the man Advocate. And who more proper for this Purpose than Carneades, who arrived to such a Degree of Perfection, (the utmost his Sect aimed at,) that he could argue for or against Truth, with the same Force of Eloquence? This Man having undertaken to dispute against Justice, that kind of it, especially, which is the Subject of this Treatise, found no Argument stronger than this. [1] Laws (says he) were instituted by Men [xv] for the sake of Interest; and hence it is that they are different, not only in different Countries, according to the Diversity of their Manners, but often in the same Country, according to the Times. As to that which is called Natural Right, it is a mere Chimera. Nature prompts all Men, and in general all Animals, to seek their own particular Advantage: So that either there is no Justice at all, or if there is any, it is extreme Folly, because it engages us to procure the Good of others, to our own Prejudice.

VI. But what is here said by the Philosopher, and by the Poet after him,

1. Natural. [1] By naked Nature ne’er was understood

What’s Just and Right.Creech.

must by no Means be admitted. For Man is indeed an Animal, but one of a very high Order, and that excells all the other Species of Animals much more than they differ from one another; as the many Actions proper only to Mankind sufficiently demonstrate. Now amongst the Things peculiar to Man, is his Desire of [2] Society, that is, a certain Inclination to live with those of his own Kind, not in any Manner whatever, but peaceably, and in a Community regulated according to the best of his Understanding; which Disposition the [3] Stoicks termed ![]() ικείωσιν. [4] Therefore the [xvi] Saying, that every Creature is led by Nature to seek its own private Advantage, expressed thus universally, must not be granted.

ικείωσιν. [4] Therefore the [xvi] Saying, that every Creature is led by Nature to seek its own private Advantage, expressed thus universally, must not be granted.

VII. For even of the other Animals there are some that forget [1] a little the Care of their own Interest, in Favour [2] either of their young ones, or those of their own Kind. Which, in my Opinion, proceeds from [3] some extrinsick intelligent Principle, because they do not shew the same Dispositions in other Matters, that are not more difficult than these. The same may be said of Infants, in whom is to be seen a Propensity to do Good to others, before they are capable of Instruction, as Plutarch [4] well observes; and Compassion likewise discovers itself upon every Occasion in that tender Age. But it must be owned that a Man grown up, being capable of acting [xvii] in the same [5] Manner with respect to Things that are alike, has, besides an exquisite Desire [6] of Society, for the Satisfaction of which he alone of all Animals has received from Nature a peculiar Instrument, viz. the Use of Speech; I say, that he has, besides that, a Faculty of knowing and acting, according to some general Principles; so that what relates to this Faculty is not common to all Animals, but properly and peculiarly agrees to Mankind.

Peculiar to Man, properly and strictly called.VIII. This Sociability, which we have now described in general, or this Care of maintaining Society [1] in a Manner conformable to the Light of human Understanding, [2] is the Fountain of Right, properly so called; to which belongs the Abstaining [3] from that which is another’s, and [xviii] the Restitution of what we have of another’s, or of the Profit we have made by it, the Obligation of fulfilling Promises, the Reparation of a Damage done through our own Default, and the Merit of Punishment among Men.

IX. From this Signification of Right arose another of larger Extent. For by reason that Man above all other Creatures isendued not only with this Social Faculty of which we have spoken, but likewise with Judgment to discern Things [1] pleasant or hurtful, and those not only present but future, and such as may prove to be so in their Consequences; it must therefore be agreeable to human Nature, that according to the Measure of our Understanding we should in these Things follow the Dictates of a right and sound Judgment, and not be corrupted either by Fear, or the Allurements of present Pleasure, nor be carried away violently by blind Passion. And whatsoever is contrary to such a Judgment [2] is likewise understood to be contrary to Natural Right, that is, the Laws of our Nature.

Improperly and more loosely.X. And to this belongs a [1] prudent Management in the gratuitous Distribution of Things that properly belong to each particular Person or [2] Society, so as to prefer sometimes one of [3] greater before one of less Merit, a Relation [4] before a Stranger, a poor Man before one that is rich, and that according as each Man’s Actions, and [5] the Nature of the Thing require; which many both of the Ancients and Moderns take to be [6] a part of Right properly and strictly so called; when notwithstanding that Right, properly speaking, has a quite different Nature, since it consists in leaving [7] others in quiet Possession of what is already their own, or in doing for them what in Strictness they may demand.

[xix]

XI. And indeed, all we have now said would take place, [1] though we should even grant, what without the greatest Wickedness cannot be granted, that there is no God, or that he takes no Care of human Affairs. The contrary of which appearing [2] to us, partly from Reason, partly from a perpetual Tradition, which many Arguments and Miracles, attested by all Ages, fully confirm; it hence follows, that God, as being our Creator, and to whom we owe our Being, and all that we have, ought to be obeyed by us in all Things without Exception, especially since he has so many Ways shewn his infinite Goodness and Almighty Power; whence we have Room to conclude that he is able to bestow, upon those that obey him, the greatest Rewards, and those eternal too, since he himself is eternal; and that he is willing so to do ought even to be believed, especially if he has in express Words promised it; as we Christians, convinced by undoubted Testimonies, believe he has.

2. Voluntary. 1. Divine.XII. And this now is another Original of Right, besides that of Nature, being that which proceeds from the free Will [1] of God, to which our Understading infallibly assures us, we ought to be subject: And even the Law of Nature itself, whether it be that which consists in the Maintenance of Society, or that which in a looser Sense is so called, though it flows from the internal Principles of Man, may notwithstanding be justly ascribed [2] to God, because it was his Pleasure that these Principles should be in us. And in this Sense Chrysippus [3] and the Stoicks said, that the Original of Right is to be derived from no other than Jupiter himself; from which Word Jupiter it is probable [4] the Latins gave it the Name Jus.

XIII. There is yet this farther Reason for ascribing it to God, that God by the Laws which he has given, has made these very Principles more clear and evident, even to those who are less capable of strict Reasoning, and has forbid us to give way to those impetuous [1] Passions, which, [xx] contrary [2] to our own Interest, and that of others, divert us from following the Rules of Reason and Nature; for as they are exceeding unruly, it was necessary to keep a strict Hand over them, and to confine them within certain narrow Bounds.

XIV. Add to this, that sacred History, besides the Precepts it contains to this Purpose, affords no inconsiderable Motive to social Affection, since it teaches us that all Men are descended from the same first Parents. So that in this Respect also may be truly affirmed, what Florentinus said in another Sense, That [1] Nature has made us all akin: Whence it follows, that it is a Crime for one Man to act to the Prejudice of another.

XV. Amongst Men, Parents [1] are as so many Gods [2] in regard to their Children: Therefore the latter owe them an Obedience, not indeed unlimited, but as extensive [3] as that Relation requires, and as great as the Dependence of both upon a common Superior permits.

2 Human.XVI. Again, since the fulfilling of Covenants belongs to the Law of Nature, (for it was necessary there should be some Means of obliging Men among themselves, and we cannot conceive any other more conformable to Nature) from this very Foundation [1] Civil Laws were derived.Civil of every State. For those who had incorporated themselves into any Society, or subjected themselves to any one Man, or Number of Men, had either expressly, or from the Nature of the Thing must be understood to have tacitly promised, that they would submit to whatever either the greater part of the Society, or those on whom the Sovereign Power had been conferred, had ordained.

XVII. Therefore the Saying, not of Carneades only, but of others,

[1] Interest, that Spring of Just and Right.

Creech.

if we speak accurately, is not true; for the Mother of Natural Law is human Nature itself, which, though even the Necessity of our Circumstances should not require it, would of itself create in us a mutual Desire of Society: And the Mother of Civil Law is that very Obligation which arises from Consent, which deriving its Force from the Law of Nature, Nature may be called as it were, the Great Grandmother of this Law also. But to the Law of Nature Profit is annexed: For the Author of Nature was pleased, that every Man in particular [2] should be weak of himself, and in Want of many Things necessary for living commodiously, to the End we might more eagerly affect Society: Whereas of the Civil Law Profit was the Occasion; for that entering into Society, or that Subjection which we spoke of, began first for the Sake of some Advantage. And besides, those who prescribe Laws to others, usually have, or ought [3] to have, Regard to some Profit therein.

XVIII. But as the Laws of each State respect the Benefit of that State; so amongst all or most States there might be, and in Fact there are, some Laws agreed on by common Consent, which respect the Advantage not of one Body in particular, but of all in general. And this is what is called the Law of Nations, [1] Of Nations; of all or most States. when used in Distinction to the [2] Law of Nature. This [xxi] Part of Law Carneades omitted, in the Division he made of all Law into Natural and Civil of each People or State; when notwithstanding, since he was to treat of the Law which is between Nations (for he added a Discourse concerning Wars and Things got by War) he ought by all means to have mentioned this Law.

II. Objections confuted: Justice not Folly.XIX. But it is absurd in him to traduce Justice with the Name of Folly. [1] For as, according to his own Confession, that Citizen is no Fool, who obeys the Law of his Country, though out of Reverence to that Law he must and ought to pass by some Things that might be advantageous to himself in particular: So neither is that People or Nation foolish, who for the Sake of their own particular Advantage, will not break in upon the Laws common to all Nations; for the same Reason holds good in both. For [2] as he that violates the Laws of his Country for the Sake of some present Advantage to himself, thereby saps the Foundation of his own perpetual Interest, and at the same Time that of his Posterity: So that People which violate the Laws of Nature and Nations, break down the Bulwarks of their future Happiness and Tranquillity. But besides, though there were no Profit to be expected from the Observation of Right, yet it would be a Point of Wisdom, not of Folly, to obey the Impulse and Direction of our own Nature.

XX. Therefore neither is this Saying universally true,

[1] ’Twas Fear of Wrong that made us make our Laws.

Creech.

which one in Plato expresses thus, [2] The Fear of receiving Injury occasioned the Invention of Laws, and it was Force that obliged Men to practice Justice. For this Saying is applicable only to those Constitutions and Laws which were made for the better Execution of Justice: Thus many, finding themselves weak when taken singly and apart, did, for fear of being oppressed by those that were stronger, unite together to establish, and with their joint Forces to defend Courts of Judicature, to the End they might be an Overmatch for those whom singly they were unable to deal with. And now in this Sense only may be fitly taken what is said, That Law is that which the stronger pleases to impose; by which we are to understand, that Right has not its Effect externally, unless it be supported by Force. Thus Solon did great Things, as he himself boasted,

[3] By linking Force in the same Yoke with Law.

Justice brings Peace to the Conscience.XXI. Yet neither does Right lose all its Effect, by being destitute of the Assistance of Force. For Justice brings Peace to the Conscience; Injustice, Racks and Torments, such as Plato [1] describes in the Breasts of Tyrants. Justice is approved of, Injustice condemned by the Consent of all good Men. But that which is greatest of all, to this God is an Enemy, to the other a Patron, who does not so wholly reserve his Judgments for a future Life, but that he often makes the Rigour of them to be perceived in this, as Histories teach us by many Examples.

[xxii]

Equally concerns private Persons, Nations, and Rulers of Nations.XXII. But whereas many that require Justice in private Citizens, make no Account of it in a whole Nation or its Ruler; the Cause of this Error is, first, that they regard nothing in Right but the Profit arising from the Practice of its Rules, a Thing which is visible with Respect to Citizens, who, taken singly, are unable to defend themselves. But great States, that seem to have within themselves all things necessary for their Defence and Wellbeing, do not seem to them to stand in need of that Virtue which respects the Benefit of [1] others, and is called Justice.

XXIII. But, not to repeat what has been already said, namely, that Right has not Interest merely for its End; there is no State so strong or well provided, but what may sometimes stand in need of Foreign Assistance, either in the Business of Commerce, or to repel the joint Forces of several Foreign Nations Confederate against it. For which Reason we see Alliances desired by the most powerful Nations and Princes, the whole Force of which is destroyed by those that confine Right within the Limits of each State. So true is it, that the Moment we recede from Right, [1] we can depend upon nothing.

XXIV. If there is no Community which can be preserved without some Sort of Right, as Aristotle [1] proved by that remarkable [2] Instance of Robbers, certainly the Society of Mankind, or of several Nations, cannot be without it; which was observed by him who said, [3] That a base Thing ought not to be done, even for the Sake of ones Country. Aristotle [4] inveighs severely [xxiii] against those, [5] who, though they would not have any to govern amongst themselves, but he that has a Right to it, yet in regard to Foreigners are not concerned whether their Actions be just or unjust.

Governs Peace;XXV. A Spartan King having said, [1] That is the most happy Commonwealth, whose Bounds were determined by Spear and Sword; the same Pompey, whom we lately mentioned on the contrary Side, correcting that Maxim said, That is happy indeed, which has Justice for its Boundaries. For which he might have used the Authority of another Spartan King, [2] who preferred Justice before [3] military Fortitude, for this Reason, that Fortitude ought to be regulated by some sort of Justice: And that if all Men were Just, they would have no Occasion for that Fortitude. The Stoicks defined [4] Fortitude itself to be the Virtue that contends for Justice. Themistius, in his Oration to Valens, says very elegantly, that Kings, who conduct themselves by the Rules of Wisdom, take Care, not only of the Nation whose Government they are entrusted with, but of all Mankind; and are, as he expresses himself, not ![]() ιλομακέδονες Friends to the Macedonians only, or

ιλομακέδονες Friends to the Macedonians only, or ![]() ιλο

ιλο![]() ωμαίοι to the Romans, but

ωμαίοι to the Romans, but ![]() ιλάνθ

ιλάνθ![]() ωποι [5] to all Men without Exception. Nothing else made the Name of Minos odious to Posterity, [6] but his confining Equity within the Limits of his own Empire.

ωποι [5] to all Men without Exception. Nothing else made the Name of Minos odious to Posterity, [6] but his confining Equity within the Limits of his own Empire.

and War; hence the Laws of War.XXVI. But so far must we be from admitting the Conceit of some, that the Obligation of all Right ceases in War; that on the contrary, no War ought to be so much as undertaken but for the obtaining of Right; nor when undertaken, ought it to be carried on beyond the Bounds of Justice and Fidelity. Demosthenes [1] said well, that War is made against those who cannot be restrained in a judicial Way. For judicial Proceedings are of Force against those who are sensible of their Inability to oppose them; but against those who are or think themselves of equal Strength, Wars are undertaken; but yet certainly, to render Wars just, they are to be waged with no less Care and Integrity, than judicial Proceedings are usually carried on.

XXVII. Let it be granted then, that [1] Laws must be silent in the midst of Arms, provided they are only those Laws that are Civil and Judicial, and proper for Times of Peace; but not [xxiv] those that are of perpetual Obligation, and are equally suited to all Times. For it was very well said of Dion Prusaeensis, [2] That between Enemies, Written, that is, Civil Laws, are of no Force, but Unwritten [3] are, that is, those which Nature dictates, or the Consent of Nations has instituted. This we are taught by that ancient Form of the Romans, [4] These Things I think must be recovered by a pure and just War. The same ancient Romans, as Varro observed, [5] were very slow and far from all Licentiousness in entring upon War, because they thought that no War but such as is lawful and accompanied with Moderation, ought to be carried on. It was the Saying of Camillus, [6] That Wars ought to be managed with as much Justice as Valour: And of Scipio Africanus, [7] That the Romans both begin and finish their Wars with Justice. An Author [8] maintains, There are Laws of War, as there are of Peace. Another [9] admires Fabricius for a very great Man, and remarkable for a Virtue which is extremely difficult, Innocence in War, and who believed that there are some Things, which it would be unlawful to practise even against an Enemy.

XXVIII. Of how great Force in Wars is the Consciousness of the Justice of [1] the Cause, Historians every where shew, who often ascribe the Victory chiefly to this Reason. Hence the [xxv] Proverbial Sayings, [2] A Soldier’s Courage rises or falls according to the Merit of his Cause; [3] seldom does he return safely, who took up Arms unjustly; Hope is the [4] Companion of a good Cause; and others to the same Purpose. Nor ought any one to be moved at the prosperous Successes of unjust Attempts; for it is sufficient that the Equity of the Cause has of itself a certain, and that very great Force towards Action, though that Force, as it happens in all human Affairs, is often hindered of its Effect, by the Opposition of other [5] Causes. The Opinion that a War is not rashly and unjustly begun, nor dishonourably carried on, is likewise very prevalent towards procuring Friendships; which Nations, as well as private Persons, stand in need of upon many Occasions. For no Man readily associates ciates with those, who, he thinks, have Justice, Equity and Fidelity in Contempt.

III. The Author’s Reasons for writing this Book.XXIX. Now for my Part, being fully assured, by the Reasons I have already given, that there is some Right common to all Nations, which takes Place both in the Preparations and in the Course of War, I had many and weighty Reasons inducing me to write a Treatise upon it. I observed throughout the Christian World a Licentiousness in regard to War, which even barbarous Nations ought to be ashamed of:Restraining the Licentiousness in making War. a Running to Arms upon very frivolous or rather no Occasions; which being once taken up, there remained no longer any Reverence for Right, either Divine or Human, just as if from that Time Men were authorized and firmly resolved to commit all manner of Crimes without Restraint.

XXX. The Spectacle of which monstrous Barbarity worked many, and those in no wise bad Men, up into an Opinion, that a Christian, whose Duty consists principally in loving all Men without Exception, ought not at all [1] to bear Arms; with whom seem to agree sometimes Johannes Ferus [2] and our Countryman [3] Erasmus, Men that were great Lovers of Peace both Ecclesiastical and Civil; but, I suppose, they had the same View, as those have who in order to make Things that are crooked straight, usually [4] bend them as much the other Way. But this very Endeavour of inclining too much to the opposite Extreme, is so far from doing Good, that it often does Hurt, because Men readily discovering Things that are urged too far by them, are apt to slight their Authority in other Matters, which perhaps are more reasonable. A Cure therefore was to be applied to both these, as well to prevent believing that Nothing, as that all Things are lawful.

An endeavour to promote the Knowledge of Law, by giving an Example of a Method for it.XXXI. At the same Time I was likewise willing to promote, by my private Studies, the Profession of Law, which I formerly practised in publick [1] Employments with all possible Integrity; this being the only Thing that was left for me to do, being unworthily [2] banished my Native Country, which I have honoured with so many of my Labours. Many have before this designed [xxvi] to reduce it into a System; but none has accomplished it; nor indeed can it be done, unless those things (which has not been yet sufficiently taken Care of,) that are established [3] by the Will of Men, be duly distinguished from those which are founded on Nature. For the Laws of Nature being always the same, may be easily collected into an Art; but those which proceed from Human Institution being often changed, and different in different Places, are no more susceptible of a methodical System, than other Ideas of particular Things are.

XXXII. But if the Professors of true Justice would undertake to treat of the several Parts of that Law which is perpetual and natural, setting aside every Thing which owes its Rise to Voluntary Institution, so that one for Instance would treat of Laws, another of Tributes, another of the Office of Judges, another of the Conjecture of Wills, another of the Evidence in Matters of Fact, there might at last from all the Parts collected together be a Body of Law composed.

IV. The Contents and Order of the Work.XXXIII. What Method we thought fit to use, we have shewn in Deed rather than in Words in this Treatise, which contains that Part of Law, which is by far the noblest.

Book I.XXXIV. For in the first Book, after premising some Things concerning the Origin of Right, we have examined the general Question, whether any War is just; afterwards to discover the Difference between a publick and private War, our Business was to explain the Extent of the Supreme Power, what People, what Kings have it in full, who in part, who with a Power of alienating it, and who have it without that Power. And then we were to speak of the Duty of Subjects to their Sovereigns.

Book II.XXXV. The second Book, undertaken to explain all the Causes from whence a War may arise, shews at large, what Things are common, what proper, what Right one Person may have over another, what Obligation arises from the Property of Goods, what is the Rule of Regal Succession, what Rightarises from Covenant or Contract, what the Force and Interpretation of Treaties and Alliances, what of an Oath both publick and private, what may be due for a Damage done, what the Privileges of Embassadors, what the Right of burying the Dead, what the Nature of Punishments.

Book III.XXXVI. The third Book treats first of what is lawful in War; and then, having distinguished that which is done with bare Impunity, or which is even defended as lawful among foreign Nations, from that which is really blameless, descends to the several Kinds of Peace, and all Agreements made in war.

V. The Necessity of Writing.XXXVII. But I thought this Undertaking still the more worth my Pains, because, as I said before, this Subject has not been fully handled by any Body; and those who have treated of the Parts of it, have done it so, that they have left a great deal for the Labour of others.Nothing of the ancient Authors extant on this Subject. There is nothing of this Kind extant of the ancient Philosophers, whether those of the Pagan Greeks, (amongst whom Aristotle had composed a Book intitled, Δικαιώματα Πολέμων, [1] The Rights of War,) or those of the Primitive Christians, which was very much to be wished for. Nay, of those Books of the ancient Romans concerning the [2] Fecial Law, we have nothing transmitted to us but the bare Name: Those who have made Sums of Cases of Conscience, as they call them, have made only Chapters, as of other Things, so of War, of Promises, of an Oath, of Reprizals.

The Defects of the Moderns.XXXVIII. I have likewise seen some particular Treatises concerning the Rights of War, some of which were written by Divines, as [1] Franciscus Victoria, Henricus [2] Gorichemus, [3] Wilhelmus Matthaei, Johannes [4] de Carthagena; some by Professors of Law, as [5] Johannes Lupus, [6] Franciscus Arius, [7] Johannes de Lignano, [8] Martinus Laudensis. But upon so copious a Subject, they have all of them said but very little, and most of them in such a Manner, that they have, without any Order, mixed and confounded together those Things that belong severally to the Law Natural, Divine, of Nations, Civil and Canon.

XXXIX. What was most wanting in all those, viz. Illustrations from History, the most Learned [1] Faber has undertaken to supply in some Chapters of his Semestria, but no farther than [xxvii] served his Purpose, and only by alledging some Authorities. The same has been done more largely, and that by applying a Multitude of Examples to some general Maxims laid down, by Balthazar [2] Ayala, and still more largely by Albericus [3] Gentilis, whose Labour, as I know it may be serviceable to others, and confess it has been to me, so what may be faulty in his Stile, in Method, in distinguishing of Questions, and the several Kinds of Right, I leave to the Reader’s Judgment. I shall only say this, that in the Decision of Controversies, he is often wont to follow either a few Examples that are not always to be approved of, or even the Authority of modern Lawyers in their Answers, not a few of which are [4] accommodated to the Interest of those that consult them, and not formed by the invariable Rules of Equity and Justice. The Causes, from whence a War is denominated just or unjust, Ayala has not so much as touched upon: Gentilis has indeed described after his Manner some of the general Heads; but neither has he touched upon many famous Questions, which turn upon Cases that are very common.

I. The Author’s Case,XL. We have been careful that nothing of this Kind be passed over in Silence, having likewise shewn the very Foundations upon which we build our Decisions, so that it might be easy to determine any Question that may happen to be omitted by us. It remains now, that I briefly declare with what Assistance, and with what Care I undertook this Work.1. In proving the Law of Nature. My first Care was, to refer the Proofs of those Things that belong to the Law of Nature to some such certain Notions, as none can deny, without doing Violence to his Judgment. For the Principles of that Law, if you rightly consider, are manifest and self-evident, almost after the same Manner as those Things are that we perceive with our outward Senses, which do not deceive us, if the Organs are rightly disposed, and if other Things necessary are not wanting. Therefore Euripides in his Phoenissae makes Polynices, whose Cause he would have to be represented manifestly just, deliver himself thus:

[1] I speak not Things hard to be understood,

But such as, founded on the Rules of Good

And Just, [2] are known alike to Learn’d and Rude.

And he immediately adds the Judgment of the Chorus, (which consisted of Women and those too Barbarians) approving what he said.

XLI. I have likewise, towards the Proof of this Law, made Use of the Testimonies of [1] Philosophers, Historians, Poets, and in the last Place, Orators; not as if they were to be implicitly believed; for it is usual with them to accommodate themselves to the [2] Prejudices of their Sect, the Nature of their [3] Subject, and [4] the Interest of their Cause: But that when many Men of different Times and Places unanimously affirm the same Thing for Truth, this ought to be ascribed to a general Cause; which in the Questions treated of by us, can be no other than either a just [xxviii] Inference drawn from the Principles of Nature, or an universal Consent.Of Nations. The former shews the Law of Nature, the other the [5] Law of Nations. The Difference between which is not to be understood from the Testimonies themselves (for the Law of Nature and of Nations are Words used every where [6] promiscuously by Writers) but from the Quality of the Subject.2. In distinguishing both of them, and the Civil Law. For that which cannot be deduced from certain Principles by just Consequences, and yet appears to be every where observed, must owe its rise to a free and arbitrary Will.

XLII. Therefore these two I have very carefully endeavoured always to distinguish no less from one another, than from the Civil Law: And even in the Law of Nations, I have made a Distinction between that which is truly and in every Respect lawful,The Species of each. and that which only produces a certain external Effect after the Manner of that primitive Law; so that, for Instance, it may be lawful to resist it, or that it even ought to be every where defended with the publick Force, for the Sake of some Advantage that attends it, or that some great Inconveniences may be avoided. Which Observation, how necessary it is in many Respects, will appear in the following [1] Treatise. We have been no less careful in distinguishing Things belonging to Right properly and strictly so called, whence arises the Obligation of making Restitution, from those which are only said to belong to it, because that the acting otherwise is repugnant to some other Dictate of right Reason: Which Distinction we have already touched upon.

II. Assistance in the Work.XLIII. Among Philosophers Aristotle deservedly holds the chief Place, whether you consider his Method of treating Subjects, or the Acuteness of his Distinctions, or the Weight of his Reasons. I could only wish that the Authority of this great Man had not for some Ages past degenerated into Tyranny,1. Philosophers. Aristotle, his Praise. so that Truth, for the Discovery of which Aristotle took so great Pains, is now oppressed by nothing more than the very Name of Aristotle. I, for my Part, both in this and in all my other Writings, take to myself the Liberty of the ancient Christians, who espoused no Sect of Philosophers; not that they held with those who asserted that nothing can be known, than which there is nothing more foolish; but were of Opinion, that there was no one Sect that had discovered all Truth, nor any but what held something that was true. Therefore to collect into a Body the Truths that were dispersed in the Writings of each Philosopher and each Sect, they conceived to be nothing else, but [1] to deliver the true Christian Doctrine.

His Faults.XLIV. Among other Things, (that I may mention this by the by, as not being foreign to our Purpose,) it is not without Reason, that some of the Platonists and ancient [1] Christians seem to dissent from Aristotle in this, that he placed the very Nature of Virtue [2] in a Mediocrity of Passions and Actions; which being once laid down, drove him to this, that of Virtues of a different Kind, as for Instance, [3] Liberality and Frugality, he made but one; and [xxix] assigned [4] to Veracity two Opposites between which there is not an equal Contrariety, viz. Boasting and false Modesty; and imposed the Name of Vice upon some Things, which either are not in Nature, or in themselves are not Vices, as, the [5] Contempt of Pleasure and [6] Honours, [xxx] and an Insensibility to Injuries, which [7] hinders us from being angry against Men.

All Virtue has not Vice in Excess.XLV. But that this Principle of Mediocrity, taken universally, is not rightly laid, appears from the Instance of Justice itself, whose Opposites, too much and too little, when he could not find in the Affections and their subsequent Actions, [1] he sought for Both in the Things themselves [xxxi] about which Justice is conversant. Which very thing is in the first Place to leap from one kind of Thing to another, which he deservedly blames in others; and in the next Place, to receive less [2] than one’s Due may indeed happen to be a Vice, when the Circumstances of himself or his Family cannot allow of any Abatement; but certainly it cannot be repugnant to Justice, since it consists wholly in abstaining from that which is another Man’s. Like to which Mistake is that of his not allowing [3] Adultery proceeding from Lust, and Murder from Anger, to belong properly to Injustice: Whereas the very Nature of Injustice consists in nothing, else, but in the Violation of another’s Rights; nor does it signify, whether it proceeds from Avarice, or Lust, or Anger, or imprudent Pity, or Ambition, which are usually the Sources of the greatest Injuries. For to resist all Temptations of what Kind soever, and that for this only Reason, viz. the preserving of Human Society inviolable, is indeed the proper Business of Justice.