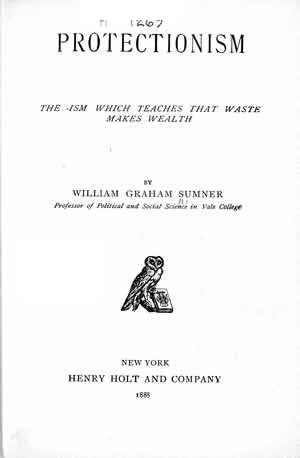

William Graham Sumner, Protectionism: The -Ism which teaches that Waste makes Wealth (1888)

|

|

| William Graham Sumner (1840-1910) |

This is part of a collection of works by William Graham Sumner.

Source

William Graham Sumner, Protectionism: The -Ism which teaches that Waste makes Wealth (New York: Henry Holt and Co., 1888).

See the facs. PDF.

See also his History of Protection in the United Sattes (1877) [HTML] and his survey of "Free Trade" written for the Nouveau Dictionnaire d'Économie politique (189-92) [en français in HTML and facs. PDF].

Editor's Note: The index has been removed from the HTML version. It can be viwed in the facs. PDF version if required. The table of contents has also been moved to the top of the document.

Table of Contents

- PREFACE

- CHAPTER I.: DEFINITIONS: STATEMENT OF THE QUESTION TO BE INVESTIGATED.

- A.): The System of which Protection is a Survival.

- B.): Old and New Conceptions of the State.

- C.): Definition of Protectionism.—Definition of “Theory.”

- D.): Definition of Free Trade and of a Protective Duty.

- E.): Protectionism Raises a Purely Domestic Controversy.

- F.): “A Protective Duty is not a Tax.”

- CHAPTER II.: PROTECTIONISM EXAMINED ON ITS OWN GROUNDS.

- A.): Assumptions in Protectionism.

- B.): Necessary Conditions of Successful Protective Legislation.

- C.): Examination of the Means Proposed, Viz., Taxes.

- D.): Examination, of the plan of Mutual Taxation.

- E.): Examination of the Proposal to “Create an Industry.”

- F.): Examination of the Proposal to Develop our Natural Resources.

- G.): Examination of the Proposal to Raise Wages.

- H.): Examination of the Proposal to Prerent Competition by Foreign Pauper Labor.

- I.): Examination of the Proposal to raise the Standard of Public Comfort.

- Chapter III.: PROTECTIONISM EXAMINED ADVERSELY.

- CHAPTER IV.: SUNDRY FALLACIES OF PROTECTIONISM

- (A.): That infant industries can be nourished up to independence and that they then become productive.

- (B.): That protective taxes do not raise prices but lower prices.

- (C.): That we should be a purely agricultural nation under free trade.

- (D.): That communities which manufacture are more prosperous than those which are agricultural.

- (E.): That it is an object to diversify industry, and that nations which have various industries are stronger than others which have not various industries.

- (F.): That manufactures give value to land.

- (G.): That the farmer, if he pays taxes to bring into existence a factory, which would not otherwise exist, will win more than the taxes by selling farm produce to the artisans.

- (H.): That farmers gain by, protection, because it draws so many laborers out of competition with them.

- (I.): That our industries would perish without protection.

- (J.): That it would be wise to call into existence various industries, even at an expense, if we could thus offer employment to all kinds of artisans, etc., who might come to us.

- (K.): That we want to be complete in ourselves and sufficient to ourselves, and independent, as a nation, which state of things will be produced by protection.

- (L.): That protective taxes are necessary to prevent a foreign monopoly from getting control of our market.

- (M.): That free trade is good in theory but impossible in practice; that it would be a good thing if all nations would have it.

- (N.): That trade is WAR, so that free trade methods are unfit for it, and that protective taxes are suited to it.

- (O.): That protection brings into employment labor and capital which would otherwise be idle.

- (P.): That a young nation needs protection and will suffer some disadvantage in free exchange with an old one.

- (Q.): That we need protection to get ready for war.

- (R.): That protectionism produces some great moral advantages.

- (S.): That a “worker may gain more by having his industry protected than he will lose by having to pay dearly for what he consumes. A system which raises prices all round—like that in the United States at present—is oppressive to consumers, but is most disadvantageous to those who consume without producing any thing, and does little, if any, injury to those who produce more than they consume.”

- (T.): That “a duty may at once protect the native manufacturer adequately, and recoup the country for the expense of protecting him.”

- Chapter V.: SUMMARY AND CONCLUSION.

- INDEX.

PREFACE ↩

During the last fifteen years we have had two great questions to discuss: the restoration of the currency, and civil-service reform. Neither of these questions has yet reached a satisfactory solution, but both are in the way toward such a result. The next great effort to strip off the evils entailed on us by the civil war will consist in the repeal of those taxes which one man was enabled to levy on another, under cover of the taxes which the government had to lay to carry on the war. I have taken my share in the discussion of the first two questions, and I expect to take my share in the discussion of the third.

I have written this book as a contribution to a popular agitation. I have not troubled myself to keep or to throw off scientific or professional dignity. I have tried to make my point as directly and effectively as I could for the readers whom I address, viz., the intelligent voters of all [vi] degrees of general culture, who need to have it explained to them what protectionism is and how it works. I have therefore pushed the controversy just as hard as I could, and have used plain language, just as I have always done before in what I have written on this subject. I must therefore forego the hope that I have given any more pleasure now than formerly to the advocates of protectionism.

Protectionism seems to me to deserve only contempt and scorn, satire and ridicule. It is such an arrant piece of economic quackery, and it masquerades under such an affectation of learning and philosophy, that it ought to be treated as other quackeries are treated. Still, out of deference to its strength in the traditions and lack of information of many people, I have here undertaken a patient and serious exposition of it. Satire and derision remain reserved for the dogmatic protectionists and the sentimental protectionists; the Philistine protectionists and those who hold the key of all knowledge; the protectionists of stupid good faith, and those who know their dogma is a humbug and are therefore irritated at the exposure of it; the protectionists by birth [vii] and those by adoption; the protectionists for hire and those by election; the protectionists by party platform and those by pet newspaper: the protectionists by “invincible ignorance,” and those by vows and ordination; the protectionists who run colleges, and those who want to burn colleges down; the protectionists by investment and those who sin against light; the hopeless ones who really believe in British gold and dread the Cobden Club, and the dishonest ones who storm about those things without believing in them; those who may not be answered when they come into debate, because they are “great” men, or because they are “old” men, or because they have stock in certain newspapers, or are trustees of certain colleges. All these have honored me personally, in this controversy, with more or less of their particular attention. I confess that it has cost me something to leave their cases out of account, but to deal with them would have been a work of entertainment, not of utility.

Protectionism arouses my moral indignation. It is a subtle, cruel, and unjust invasion of one man's rights by another. It is done by force of law. It is at the same time a social abuse, an [viii] economic blunder, and a political evil. The moral indignation which it causes is the motive which draws me away from the scientific pursuits which form my real occupation, and forces me to take part in a popular agitation. The doctrine of a “call” applies in such a case, and every man is bound to take just so great a share as falls in his way. That is why I have given more time than I could afford to popular lectures on this subject, and it is why I have now put the substance of those lectures into this book.

W. G. S.

[ix]

[1]

CHAPTER I.: DEFINITIONS: STATEMENT OF THE QUESTION TO BE INVESTIGATED. ↩

A.): The System of which Protection is a Survival.

1. The statesmen of the eighteenth century supposed that their business was the art of national prosperity. Their procedure was to form ideals of political greatness and civil prosperity on the one hand, and to evolve out of their own consciousness grand dogmas of human happiness and social welfare on the other hand. Then they tried to devise specific means for connecting these two notions with each other. Their ideals of political greatness contained, as predominant elements, a brilliant court, a refined and elegant aristocracy, well developed fine arts and belles lettres, a powerful army and navy, and a peaceful, obedient and [2] hard working peasantry and artisan class to pay the taxes and support the other part of the political structure. In this ideal the lower ranks paid upward, and the upper ranks blessed downward, and all were happy together. The great political and social dogmas of the period were exotic and incongruous. They were borrowed or accepted from the classical authorities. Of course the dogmas were chiefly held and taught by the philosophers, but, as the century ran its course, they penetrated the statesman class. The statesman who had had no purpose save to serve the “grandeur” of the king, or to perpetuate a dynasty, gave way to statesmen who had strong national feeling and national ideals, and who eagerly sought means to realize their ideals. Having as yet no definite notion, based on facts of observation and experience, of what a human society or a nation is, and no adequate knowledge of the nature and operation of social forces, they were driven to empirical processes which they could not test, or measure, or verify. They piled device upon device and failure upon failure. When one device failed of its intended purpose and produced an unforeseen evil, they invented a new device to prevent the new [3] evil. The new device again failed to prevent, and became a cause of a new harm, and so on indefinitely.

2. Among their devices for industrial prosperity were (I) export taxes on raw materials, to make raw materials abundant and cheap at home; (2) bounties on the export of finished products, to make the exports large; (3) taxes on imported commodities to make the imports small, and thus, with No. 2, to make the “balance of trade” favorable, and to secure an importation of specie; (4) taxes or prohibition on the export of machinery. so as not to let foreigners have the advantage of domestic inventions; (5)prohibition on the emigration of skilled laborers, lest they should carry to foreign rivals knowledge of domestic arts; (6) monopolies to encourage enterprise; (7) navigation laws to foster ship-building or the carrying trade, and to provide sailors for the navy; (8) a colonial system to bring about by political force the very trade which the other devices had destroyed by economic interference; (9) laws for fixing wages and prices to repress the struggle of the non-capitalist class to save themselves in the social press; (10) poor-laws to lessen the struggle [4] by another outlet; (II) extravagant criminal laws to try to suppress another development of this struggle by terror; and so on, and so on.

B.): Old and New Conceptions of the State.

3. Here we have a complete illustration of one mode of looking at human society, or at a state. Such society is, on this view, an artificial or mechanical product. It is an object to be molded, made, produced by contrivance. Like every product which is brought out by working up to an ideal instead of working out from antecedent truth and fact, the product here is hap hazard, grotesque, false. Like every other product which is brought out by working on lines fixed by à priori assumptions, it is a satire on human foresight and on what we call common sense. Such a state is like a house of cards, built up anxiously one upon another, ready to fall at a breath, to be credited at most with naive hope and silly confidence; or, it is like the long and tedious contrivance of a mischievous school-boy, for an end which has been entirely mis-appreciated and was thought desirable when it should have been thought a folly; or, it is like the museum [5] of an alchemist, filled with specimens of his failures, monuments of mistaken industry and testimony of an erroneous method; or, it is like the clumsy product of an untrained inventor, who, instead of asking “what means have I, and to what will they serve?” asks: “what do I wish that I could accomplish?” and seeks to win steps by putting in more levers and cogs, increasing friction and putting the solution ever further off.

4. Of course such a notion of a state is at war with the conception of a state as a seat of original forces which must be reckoned with all the time; as an organism whose life will go on any how, perverted, distorted, diseased, vitiated as it may be by obstructions or coercions; as a seat of life in which nothing is ever lost, but every antecedent combines with every other and has its share in the immediate resultant, and again in the next resultant, and so on indefinitely; as the domain of activities so great that they should appall any one who dares to interfere with them; of instincts so delicate and self-preservative that it should be only infinite delight to the wisest man to see them come into play, and his sufficient glory to give them a little intelligent assistance. [6] If a state well performed its functions of providing peace, order and security, as conditions under which the people could live and work, it would be the proudest proof of its triumphant success that it had nothing to do—that all went so smoothly that it had only to look on and was never called to interfere; just as it is the test of a good business man that his business runs on smoothly and prosperously while he is not harassed or hurried. The people who think that it is proof of enterprise to meddle and “fuss” may believe that a good state will constantly interfere and regulate, and they may regard the other type of state as “non-government.” The state can do a great deal more than to discharge police functions. If it will follow custom, and the growth of social structure to provide for new social needs, it can powerfully aid the production of structure by laying down lines of common action, where nothing is needed but some common action on conventional lines; or, it can systematize a number of arrangements which are not at their maximum utility for want of concord; or, it can give sanction to new rights which are constantly created by new relations under new social organizations, and so on.

[7]5. The latter idea of the state has only begun to win way. All history and sociology bear witness to its comparative truth, at least when compared with the former. Under the new conception of the state, of course liberty means breaking off the fetters and trammels which the “wisdom” of the past has forged, and laissez faire, or “let alone,” becomes a cardinal maxim of statesmanship, because it means, “Cease the empirical process. Institute the scientific process. Let the state come back to normal health and activity, so that you can study, it, learn something about it from an observation of its phenomena, and then regulate your action in regard to it by intelligent knowledge.” Statesmen suited to this latter type of state have not yet come forward in any great number. The new radical statesmen show no disposition to let their neighbors alone. They think that they have come into power just because they know what their neighbors need to have done to them. Statesmen of the old type, who told people that they knew how to make every body happy, and that they were going to do it, were always far better paid than any of the new type ever will be, and their failures never [8] cost them public confidence either. We have got tired of kings, priests, nobles and soldiers, not because they failed to make us all happy, but because our à priori dogmas have changed fashion. We have put the administration of the state in the hands of lawyers, editors, littérateurs and professional politicians, and they are by no means disposed to abdicate the functions of their predecessors, or to abandon the practice of the art of national prosperity. The chief difference is that, whereas the old statesmen used to temper the practice of their art with care for the interests of the kings and aristocracies which put them in power, the new statesmen feel bound to serve those sections of the population which have put them where they are.

6. Some of the old devices above enumerated (§ 2) are, however, out of date, or are becoming obsolete.* Number 3, taxes on imports for other than fiscal purposes, is not among this number. Just now such taxes seem to be coming back into [9] fashion, or to be enjoying a certain revival. It is a sign of the deficiency of our sociology as compared with our other sciences that such a phenomenon could be presented in the last quarter of the nineteenth century, as a certain revival of faith in the efficiency of taxes on imports as a device for producing national prosperity. There is not a single one of the eleven devices mentioned above, including taxes on the exportation of machinery and prohibitions on emigration, which is not quite as rational and sound as taxes on imports.

I now propose to analyze and criticise protectionism.

C.): Definition of Protectionism.—Definition of “Theory.”

7. By protectionism I mean the doctrine of protective taxes as a device to be employed in the art of national prosperity. The protectionists are fond of representing themselves as “practical” and the free traders as “theorists.” Theory is indeed one of the worst abused words in the language, and the scientists are partly to blame for it. They have allowed the word to come into [10] use, even among themselves, for a conjectural explanation, or a speculative conjecture, or a working hypothesis, or a project which has not yet been tested by experiment, or a plausible and harmless theorem about transcendental relations, or about the way in which men will act under certain motives. The newspapers seem often to use the word theoretical as if they meant by it imaginary or fictitious. I use the word theory, however, not in distinction from fact, but, in what I understand to be the correct scientific use of the word, to denote a rational description of a group of coordinated facts in their sequence and relations. A theory may, for a special purpose, describe only certain features of facts and disregard others. Hence “in practice,” where facts present themselves in all their complexity, he who has carelessly neglected the limits of his theory may be astonished at phenomena which present themselves, but his astonishment will be due to a blunder on his part, and will not be an imputation on the theory.

8. Now free trade is not a theory in any sense of the word. It is only a mode of liberty; one form of the assault (and therefore negative) which [11] the expanding intelligence of the present is making on the trammels which it has inherited from the past. Inside the United States, absolute free trade exists over a continent. No one thinks of it or realizes it. No one “feels” it. We feel only constraint and oppression. If we get liberty we reflect on it only so long as the memory of constraint endures. I have again and again seen the astonishment with which people realized the fact when presented to them that they have been living under free trade all their lives and never thought of it. When the whole world shall obtain and enjoy free trade there will be nothing more to be said about it; it will disappear from discussion and reflection; it will disappear from the text-books on political economy as the chapters on slavery are disappearing; it will be as strange for men to think that they might not have free trade as it would be now for an American to think that he might not travel in this country without a passport, or that there ever was a chance that the soil of our western states might be slave soil and not free soil. It would be as reasonable to apply the word theory to the protestant reformation, or to law reform, or to [12] anti-slavery, or to the separation of church and state, or to popular rights, or to any other campaign in the great struggle which we call liberty and progress, as to apply it to free trade. The pro-slavery men formerly did apply it to abolition, and with excellent reason, if the use of it which I have criticised ever was correct; for it required great power of realizing in imagination the results of social change, and great power to follow and trust abstract reasoning, for any man bred under slavery to realize, in advance of experiment, the social and economic gain to be won—most of all for the whites—by emancipation. It now requires great power of “theoretical conception” for people who have no experience of the separation of church and state to realize its benefits and justice. Similar observations would hold true of all similar reforms. Free trade is a revolt, a conflict, a reform, a reaction and recuperation of the body politic, just as free conscience, free worship, free speech, free press, and free soil have been. It is in no sense a theory.

9. Protectionism is not a theory in the correct sense of the term, but it comes under some of the popular and incorrect uses of the word. It is [13] purely dogmatic and à priori. It is desired to attain a certain object—wealth and national prosperity. Protective taxes are proposed as a means. It must be assumed that there is some connection between protective taxes and national prosperity, some relation of cause and effect, some sequence of expended energy and realized product, between protective taxes and national wealth. If then by theory we mean a speculative conjecture as to occult relations which have not been and can not be traced in experience, protection would be a capital example. Another and parallel example was furnished by astrology, which assumed a causal relation between the movements of the planets and the fate of men, and built up quite an art of soothsaying on this assumption. Another example, paralleling protectionism in another feature, was alchemy, which, accepting as unquestionable the notion that we want to transmute lead into gold if we can, assumed that there was a philosopher's stone, and set to work to find it through centuries of repetition of the method of “trial and failure.”

10. Protectionism then is an ism, that is, it is a doctrine or system of doctrine which offers no [14] demonstration, and rests upon no facts, but appeals to faith on grounds of its à priori reasonableness, or the plausibility with which it can be set forth. Of course, if a man should say: “I am in favor of protective taxes because they bring gain to me. That is all I care to know about them, and I shall get them retained as long as I can;”—there is no trouble in understanding him, and there is no use in arguing with him. So far as he is concerned, the only thing to do is to find his victims and explain the matter to them. The only thing which can be discussed is the doctrine of national wealth by protective taxes. This doctrine has the forms of an economic theory. It vies with the doctrine of labor and capital as a part of the science of production. Its avowed purpose is impersonal and disinterested,—the same, in fact, as that of political economy. It is not, like free trade, a mere negative position against an inherited system, to which one is led by a study of political economy. It is a species of political economy, and aims at the throne of the science itself. If it is true, it is not a corollary, but a postulate, on which, and by which, all political economy must be constructed.

[15]11. But then, lo! if the dogma which constitutes protectionism—national wealth can be produced by protective taxes and can not be produced without them—is enunciated, instead of going on to a science of political economy based upon it, the science falls dead on the spot. What can be said about production, population, land, money, exchange, labor and all the rest? What can the economist learn or do? What function is there for the university or school? There is nothing to do but to go over to the art of legislation, and get the legislator to put on the taxes. The only questions which can arise are as to the number, variety, size and proportion of the taxes. As to these questions the economist can offer no light. He has no method of investigating them. He can deduce no principles, lay down no laws in regard to them. The legislator must go on in the dark and experiment. If his taxes do not produce the required result, if there turn out to be “snakes” in the tariff which he has adopted, he has to change it. If the result still fails, change it again. Protectionism bars the science of political economy with a dogma, and the only process of the art of statesmanship to which it leads is eternal [16] trial and failure—the process of the alchemist and of the inventor of perpetual motion.

D.): Definition of Free Trade and of a Protective Duty.

12. What then is a protective tax? In order to join issue as directly as possible, I will quote the definition given by a leading protectionist journal,* of both free trade and protection. “The term free trade, although much discussed, is seldom rightly defined. It does not mean the abolition of custom houses. Nor does it mean the substitution of direct for indirect taxation, as a few American disciples of the school have supposed. It means such an adjustment of taxes on imports as will cause no diversion of capital, from any channel into which it would otherwise flow, into any channel opened or favored by the legislation which enacts the customs. A country may collect its entire revenue by duties on imports, and yet be an entirely free trade country, so long as it does not lay those duties in such a way as to lead any one to undertake any employment, or make any investment he would avoid in the [17] absence of such duties; thus, the customs duties levied by England—with a very few exceptions—are not inconsistent with her profession of being a country which believes in free trade. They either are duties on articles not produced in England, or they are exactly equivalent to the excise duties levied on the same articles if made at home. They do not lead any one to put his money into the home production of an article, because they do not discriminate in favor of the home producer.”

13. “A protective duty, on the other hand, has for its object to effect the diversion of a part of the capital and labor of the people out of the channels in which it would run otherwise, into channels favored or created by law.”

I know of no definitions of these two things which have ever been made by any body which are more correct than these. I accept them and join issue on them.

E.): Protectionism Raises a Purely Domestic Controversy.

14. It will be noticed that this definition of a protective duty says nothing about foreigners or about imports. According to this definition, a protective duty is a device for effecting a transformation [18] in our own industry. If a tax is levied at the port of entry on a foreign commodity which is actually imported, the tax is paid to the treasury and produces revenue. A protective tax is one which is laid to act as a bar to importation, in order to keep a foreign commodity out. It does not act protectively unless it does act as a bar, and is not a tax on imports but an obstruction to imports. Hence a protective duty is a wall to inclose the domestic producer and consumer, and to prevent the latter from having access to any other source of supply for his needs, in exchange for his products, than that one which the domestic producer controls. The purpose and plan of the device is to enable the domestic producer to levy on the domestic consumer the taxes which the government has set up as a barrier, but has not collected at the port of entry. Under this device the government says: “I do not want the revenue, but I will lay the tax so that you, the selected and favored producer, may collect it.” “I do not need to tax the consumer for myself, but I will hold him for you while you tax him.”

F.): “A Protective Duty is not a Tax.”

15. There are some who say that “a tariff is not [19] a tax,” or as one of them said before a Congressional Committee: “We do not like to call it so!” That certainly is the most humorous of all the funny things in the tariff controversy. If a tariff is not a tax, what is it? In what category does it belong? No protectionist has ever yet told. They seem to think of it as a thing by itself, a Power, a Force, a sort of Mumbo Jumbo whose special function it is to produce national prosperity. They do not appear to have analyzed it, or given themselves an account of it, sufficiently to know what kind of a thing it is or how it acts. Any one who says that it is not a tax must suppose that it costs nothing, that it produces an effect without an expenditure of energy. They do seem to think that if Congress will say: “Let a tax of—per cent. be laid on article A,” and if none is imported, and therefore no tax is paid at the custom house, national industry will be benefited and wealth secured, and that there will be no cost or outgo. If that is so, then the tariff is magic. We have found the philosopher's stone. Our congressmen wave a magic wand over the country and say: “Not otherwise provided for, 150 per cent.,” and, presto! there we have wealth. Again they say: [20] “Fifty cents a yard and fifty per cent. ad valorem;” and there we have prosperity! If we should build a wall along the coast to keep foreigners and their goods out, it would cost something. If we maintained a navy to blockade our own coast for the same purpose, it would cost something. Yet it is imagined that if we do the same by a tax it costs nothing.

16. This is the fundamental fallacy of protection to which the analysis will bring us back again and again. Scientifically stated it is that. protectionism sins against the conservation of energy. More simply stated it is that the protectionist either never sees or does not tell the other side of the account, the cost, the outlay for the gains which he alleges from protection, and that when these are examined and weighed they are sure to vastly exceed the gains, if the gains were real, even taking no account of the harm to national growth which is done by restriction and interference.

17. There are only three ways in which a man can part with his product, and different kinds of taxes fall under different modes of alienating one's goods. 1st. He may exchange his product for the product of others. Then he parts with [21] his property voluntarily, and for an equivalent. Taxes which are paid for peace, order and security, fall under this head. 2d. He may give his product away. Then he parts with it voluntarily without an equivalent. Taxes which are voluntarily paid for schools, libraries, parks, etc.,etc., fall under this head. 3d. He may be robbed of it. Then he parts with it involuntarily and without an equivalent. Taxes which are protective fall under this head. The analysis is exhaustive, and there is no other place for them. Protective taxes are those which a man pays to his neighbor to hire him (the neighbor) to carry on his own business. The first man gets no equivalent (§ 108). Hence any one who says that a tariff is not a tax would have to put it in some such category as tribute, plunder, or robbery. In order, then, that we may not give any occasion for even an unjust charge of using hard words, let us go back and call it a tax.

18. In any case it is plain that we have before us the case of two Americans. The protectionists who try to discuss the subject always go off to talk English politics and history, or Ireland, or India, or Turkey. I shall not follow them. I [22] shall discuss the case between two Americans, which is the only case there is. Whether Englishmen like our tariff or not is of no consequence. As a matter of fact, Englishmen seem to have come to the opinion that if Americans will take their own home market as their share, and will keep out of the world's market, they (the Englishmen) will agree to the arrangement; but it is immaterial whether they agree, or are angry. The only question for us is: What kind of an arrangement is it for one American to tax another American? How does it work? Who gains by it? How does it affect our national prosperity? These and these only are the questions which I intend to discuss.

19. I shall adopt two different lines of investigation. First, I shall examine protectionism on its own claims and pretensions, taking its doctrines and claims for true, and following them out to see whether they will produce the promised results; and second, I shall attack protectionism adversely, and controversially. If anyone proposes a device for the public good, he is entitled to candid and patient attention, but he is also under obligation to show how he expects his scheme to work, [23] what forces it will bring into play, how it will use them, etc. The joint stock principle, credit institutions, coöperation, and all similar devices must be analyzed and the explanation of their advantage, if they offer any, must be sought in the principles which they embody, the forces they employ, the suitableness of their apparatus. We ought not to put faith in any device (e. g. bi-metalism, socialism) unless the proposers offer an explanation of it which will bear rigid and pitiless examination; for, if it is a sound device, such examination will only produce more and more thorough conviction of its merits. I shall therefore first take up protectionism just as it is offered, and test it, as any candid inquirer might do, to see whether, as it is presented by its advocates, it has any claims to confidence.

[24]

CHAPTER II.: PROTECTIONISM EXAMINED ON ITS OWN GROUNDS. ↩

20. It is the peculiar irony in all empirical devices in social science that they not only fail of the effect expected of them, but that they produce the exact opposite. Paper-money is expected to help the non-capitalist and the debtor and to make business brisk. It ruins the non-capitalists and the debtors, and reduces industry and commerce to a standstill. Socialistic devices are expected to bring about equality and universal happiness. They produce despotism, favoritism, inequality, and universal misery. The devices are, in their operation, true to themselves. They act just as an unprejudiced examination of them should have led any one to expect that they would act, or just as a limited experience has shown that they must act. If protectionism is only another case of the same kind, an examination of it on its own grounds must bring out the fact that it [25] will issue in crippling industry, diminishing capital, and lowering the average of comfort. Let us see.

A.): Assumptions in Protectionism.

21. Obviously the doctrine includes two assumptions. The first is, that if we are left to ourselves, each to choose, under liberty, his line of industrial effort, and to use his labor and capital, under the circumstances of the country, as best he can, we shall fail of our highest prosperity. Second, that, if Congress will only tax us [properly] we can be led up to higher prosperity. Hence it is at once evident that free trade and protection here are not on a level. No free trader will affirm that he has a device for making the country rich, or saving it from hard times, any more than a respectable physician will tell us that he can give us specifics and preventives to keep us well. On the contrary, so long as men live, they will do foolish things, and they will have to bear the penalty, but if they are free, they will commit only the follies which are their own, and they will bear the penalties only of those. The protectionist begins with the premiss that we [26] shall make mistakes, and that is why he, who knows how to make us go right, proposes to take us in hand. He is like the doctor who can give us just the pill we need to “cleanse our blood” and “ward off chills.” Hence either prosperity in a free trade country, or distress in a protectionist country, is fatal to protectionism, while distress in a free trade country, or prosperity in a protectionist country proves nothing against free trade. Hence the fallacy of all Mr. R. P. Porter's letters is obvious. (§§ 52, 92, 102, 154.)

22. The device by which we are to be made better than ourselves is to select some of ourselves, who certainly are not the best business men among ourselves, to go to Washington, and there turn around and tax ourselves blindly, or, if not blindly, craftily and selfishly. Surely this would be the triumph of stupidity and ignorance over intelligent knowledge, enterprise and energy. The motive which would control each of us, if we were free, would be the hope of the greatest gain. We should have to put industry, prudence, economy and enterprise into our business. If we failed, it would be through error. How is the congressional interference to act? How is it to [27] meet and correct our error? It can appeal to no other motive than desire for profit, and can only offer us a profit where there was none before, if we will turn out of the industry which we have selected, into one which we do not know. It offers a greater profit there only by means of what it takes from somebody else and somewhere else. Or, is congressional interference to correct the errors of John, James and William, and to make the idle industrious and the extravagant prudent? Any one who believes it must believe that the welfare of mankind is not dependent on the reason and conscience of the interested persons themselves, but on the caprices of blundering ignorance, embodied in a selected few, or on the trickery of lobbyists, acting impersonally and at a distance.

B.): Necessary Conditions of Successful Protective Legislation.

23. Suppose, however, that it were true that Congress had the power (by some exercise of the taxing function) to influence favorably the industrial development of the country: is it not true that men of sense would demand to be satisfied on three points, as follows?

[28]24 (a.) If Congress can do this thing, and is going to try it, ought it not, in order to succeed, to have a distinct idea of what it is aiming at and proposes to do? Who would have confidence in any man who should set out on an enterprise and who did not satisfy this condition? Has Congress ever satisfied it? Never. They have never had any plan or purpose in their tariff legislation. Congress has simply laid itself open to be acted upon by the interested parties, and the product of its tariff legislation has been simply the resultant of the struggles of the interested cliques with each other, and of the log rolling combinations which they have been forced to make among themselves. In 1882 Congress did pay some deference, real or pretended, to the plain fact that it was bound, if it exercised this mighty power and responsibility, to bring some intelligence to bear on it, and it appointed a Tariff Commission which spent several months in collecting evidence. This Commission was composed of protectionists with one exception. It recommended a reduction of 25 per cent. in the tariff, and said: “Early in its deliberations the Commission became convinced that a substantial reduction of tariff duties is demanded, [29] not by a mere indiscriminate popular clamor, but by the best conservative opinion of the country.” “Excessive duties are positively injurious to the interests which they are supposed to benefit. They encourage the investment of capital in manufacturing enterprises by rash and unskilled speculators, to be followed by disaster to the adventurers and their employés, and a plethora of commodities which deranges the operations of skilled and prudent enterprise.” (§ 111.) This report was entirely, thrown aside, and Congress, ignoring it entirely, began again in exactly the old way. The Act of 1883 was not even framed by or in Congress. It was carried out into the dark, into a conference committee,* where new and gross abuses were put into the bill under cover of a pretended revision and reduction. When a tariff bill is before Congress, the first draft starts with a certain rate on a certain article, say 20 per cent. It is raised by amendment to 50, the article is taken into a combination and the rate put up to 80 per cent.; the bill is sent to the other house, and the rate on [30] this article cut down again to 40 per cent.; on conference between the two houses the rate is fixed at 60 per cent. He who believes in the protectionist doctrine must, if he looks on at that proceeding, believe that the prosperity of the country is being kicked around the floor of Congress, at the mercy of the chances which are at last to determine with what per cent. of tax these articles will come out. And what is it that determines with what tax any given article will come out? Any intelligent knowledge of industry? Not a word of it. Nothing in the case of a given tax on a given article, but just this: “Who is behind it?” The history of tariff legislation by the Congress of the United States, throws a light upon the protective doctrine which is partly grotesque and partly revolting.

25 (b.) If Congress can exert the supposed beneficent influence on industry, ought not Congress to understand the force which it proposes to use? Ought it not to have some rules of protective legislation so as to know in what cases, within what limits, under what conditions, the device can be effectively used? Would that not be a reasonable demand to make of any man who [31] should propose a device for any purpose? Congress has never had any knowledge of the way in which the taxes which it passed were to do this beneficent work. It has never had, and has never seemed to think that it needed to get, any knowledge of the mode of operation of protective taxes. It passes taxes, as big as the conflicting interests will allow, and goes home, satisfied that it has saved the country. What a pity that philosophers, economists, sages and moralists should have spent so much time in elucidating the conditions and laws of human prosperity! Taxes can do it all.

26 (c.) If Congress can do what is affirmed and is going to try it, is it not the part of common sense to demand that some tests be applied to the experiment after a few years to see whether it is really doing as was expected? In the campaign of 1880 it was said that if Hancock was elected we should have free trade, wages would fall, factories would be closed, etc., etc. Hancock was not elected, we did not get any reform of the tariff, and yet in 1884 wages were falling, factories were closed, and all the other direful consequences which were threatened had come to pass. Bradstreet's [32] made investigations in the winter of 1884–5 which showed that 316,000 workmen, 13 per cent. of the number employed in manufacturing in 1880, were out of work, 17,550 on strike, and that wages had fallen since 1882 from 10 to 40 per cent., especially in the leading lines of manufacturing which are protected. What did these calamities all prove then? If we had had any revision of the tariff, should we not have had these things alleged again and again as results of it? Did they not then, in the actual case, prove the folly of protection? Oh! no, that would be attacking the sacred dogma, and the sacred dogma is a matter of faith, so that, as it never had any foundation in fact or evidence, it has just as much after the experiment has failed as before the experiment was made.

27. If, now, it was possible to devise a scheme of legislation which should, according to protectionist ideas, be just the right jacket of taxation to fit this country to-day, how long would it fit? Not a week. Here are 55 millions of people on 3½ million square miles of land. Every day new lines of communication are opened, new discoveries made, new inventions produced, new processes [33] applied, and the consequence is that the industrial system is in constant flux and change. How, if a correct system of protective taxes was a practicable thing at any given moment, could Congress keep up with the changes and readaptations which would be required. The notion is preposterous, and it is a monstrous thing, even on the protectionist hypothesis, that we are living under a protective system which was set up in 1864. The weekly tariff decisions by the treasury department may be regarded as the constant attempts that are required to fit that old system to present circumstances, and, as it is not possible that new fabrics, new compounds, and new processes should find a place in schedules which were made twenty years before they were invented, those decisions carry with them the fate of scores of new industries which figure in no census, and are taken into account by no congressman. Therefore, even if we believed that the protective doctrine was sound, and that some protective system was beneficial, and that the one which we have was the right one when it was made, we should be driven to the conclusion that one which is twenty years old is sure to be injurious to-day.

[34]28. There is nothing then in the legislative machinery, by which the tariff is to be made, which is calculated to win the confidence of a man of sense, but every thing to the contrary; and the experiments of such legislation which have been made, have produced nothing but warnings against the device. Instead of offering any reasonable ground for belief that our errors will be corrected and our productive powers increased, an examination of the tariff as a piece of legislation, offers to us nothing but a burden, which must cripple any economic power which we have.

C.): Examination of the Means Proposed, Viz., Taxes.

29. Every tax is a burden, and in the nature of the case can be nothing else. In mathematical language, every tax is a quantity affected by a minus sign. If it gets peace and security, that is, if it represses crime and injustice and prevents discord, which would be economically destructive, then it is a smaller minus quantity than the one which would otherwise be there, and that is the gain by good government. Hence, like every other outlay which we make, taxes must be controlled by the law of economy—to get the best [35] and most possible for the least expenditure. Instead of regarding public expenditure carelessly, we should watch it jealously. Instead of looking at taxation as conceivably a good, and certainly not an ill, we should regard every tax as on the defensive, and every cent of tax as needing justification. If the statesman exacts any more than is necessary to pay for good government economically administered, he is incompetent, and fails in his duty. I have been studying political economy almost exclusively for the last fifteen years, and when I look back over that period and ask myself what is the most marked effect which I can perceive on my own opinion, or on my standpoint, as to social questions, I find that it is this: I am convinced that nobody yet understands the multiplied and complicated effects which are produced by taxation. I am under the most profound impression of the mischief which is done by taxation, reaching, as it does, to every dinner-table and to every fire-side. The effects of taxation vary with every change in the industrial system and the industrial status, and they are so complicated that it is impossible to follow, analyze, and systematize them; but out of the study of the [36] subject there arises this firm conviction: taxation is crippling, shortening, reducing all the time, over and over again.

30. Suppose that a man has an income of $1,000, of which he has been saving $100 per annum with no tax. Now a tax of $10 is demanded of him, no matter what kind of a tax or how laid. Is he to get the tax out of the $900 expenditure or out of the $100 savings? If the former, then he must cut down his diet, or his clothing, or his house accommodation; that is, lower his standard of comfort. If the latter, then he must lessen his accumulation of capital; that is, his provision for the future. Either way his welfare is reduced and can not be otherwise affected, and, through the general effect, the welfare of the community is reduced by the tax. Of course it is immaterial that he may not know the facts. The effects are the same. In this view of the matter it is plain what mischief is done by taxes which are laid to buy parks, libraries, and all sorts of grand things. The tax-layer is not providing public order. He is spending other people's earnings for them. He is deciding that his neighbor shall have less clothes and more library or park. But when we [37] come to protective taxes the abuse is monstrous. The legislator who has in his hands this power of taxation, uses it to say that one citizen shall have less clothes in order that he may contribute to the profits of another citizen's private business.

31. Hence if we look at the nature of taxation, and if we are examining protectionism from its own standpoint, under the assumption that it is true, instead of finding any confirmation of its assumptions, in the nature of the means which it proposes to use, we find the contrary. Granting that people make mistakes and fail of the highest prosperity which they might win when they act freely, we see plainly that more taxes can not help to lift them up or to correct their errors; on the contrary, all taxation, beyond what is necessary for an economical administration of good government, is either luxurious or wasteful, and if such taxation could tend to wealth, waste would make wealth.

D.): Examination, of the plan of Mutual Taxation.

32. Suppose then that the industries and sections all begin to tax each other as we see that they do under protection. Is it not plain that [38] the taxing operation can do nothing but transfer products, never by any possibility create them? The object of the protective taxes is to “effect the diversion of a part of the capital and labor of the country from the channels in which it would run otherwise.” To do this it must find a fulcrum or point of reaction, or it can exert no force for the effect it desires. The fulcrum is furnished by those who pay the tax Take a case. Pennsylvania taxes New England on every ton of iron and coal used in its industries. Ohio taxes New England on all the wool obtained from that state for its industries.* New England taxes Ohio and Pennsylvania on all the cottons and woolens which it sells to them. What is the net final result? It is mathematically certain that the only result can be that (1) New England gets back just all she paid (in which case the system is nil, save for the expense of the process and the limitation it imposes on the industry of all), or, [39] (2) that New England does not get back as much as she paid (in which case she is tributary to the others), or, (3) that she gets back more than she paid (in which case she levies tribute on them). Yet, on the protectionist notion, this system extended to all sections, and embracing all industries, is the means of producing national prosperity. When it is all done, what does it amount to except that all Americans must support all Americans? How can they do it better than for each to support himself to the best of his ability? Then, however, all the assumptions of protectionism must be abandoned as false.

33. In 1676 King Charles II. granted to his natural son, the Duke of Richmond, a tax of a shilling a chaldron on all the coal which was exported from the Tyne. We regard such a grant as a shocking abuse of the taxing power. It is, however, a very interesting case because the mine-owner and the tax-owner were two separate per. sons, and the tax can be examined in all its separate iniquity. If, as I suppose was the case, the Tyne valley possessed such superior facilities for producing coal that it had a qualified monopoly, the tax fell on the coal mine owner (landlord); [40] that is, the king transferred to his son part of the property which belonged to the Tyne coal owners. In that view the case may come home to some of our protectionists as it would not if the tax had fallen on the consumers. If Congress had pensioned General Grant by giving him 75 cents a ton on all the coal mined in the Lehigh Valley, what protests we should have heard from the owners of coal lands in that district! If the king's son, however, had owned the coal mines, and worked them himself, and if the king had said: “I will authorize you to raise the price of your coal a shilling a chaldron, and, to enable you to do it, I will myself tax all coal but yours a shilling a chaldron,” then the device would have been modern and enlightened and American. We have done just that on emery, copper and nickel. Then the tax comes out of the consumer. Then it is not, according to the protectionist, harmful, but the key to national prosperity, the thing which corrects the errors of our incompetent sell will, and leads us up to better organization of our industry than we, in our unguided stupidity, could have made.

E.): Examination of the Proposal to “Create an Industry.”

34. The protectionist says, however, that he is going to create an industry. Let us examine this notion also from his standpoint, assuming the truth of his doctrine, and see if we can find any thing to deserve confidence. A protective tax, according to the protectionist's definition (§ 13) “has for its object to effect the diversion of a part of the labor and capital of the people * * * into channels favored or created by law.” If we follow out this proposal, we shall see what those channels are, and shall see whether they are such as to make us believe that protective taxes can increase wealth.

35. What is an industry? Some people will answer: It is an enterprise which gives employment. Protectionists seem to hold this view, and they claim that they “give work” to laborers when they make an industry. On that notion we live to work; we do not work to live. But we do not want work. We have too much work. We want a living; and work is the inevitable but disagreeable price we must pay. Hence we want as much living at as little price as possible. We [42] shall see that the protectionist does “make work” in the sense of lessening the living and increasing the price. But if we want a living we want capital. If an industry is to pay wages, it must be backed up by capital. Therefore protective taxes, if they were to increase the means of living, would need to increase capital. How can taxes increase capital? Protective taxes only take from A to give to B. Therefore, if B by this arrangement can extend his industry and “give more employment,” A's power to do the same is diminished in at least an equal degree. Therefore, even on that erroneous definition of an industry, there is no hope for the protectionist.

36. An industry is an organization of labor and capital for satisfying some need of the community. It is not an end in itself. It is not a good thing to have in itself. It is not a toy or an ornament. If we could satisfy our needs without it we should be better off, not worse off. How then can we create industries?

37. If any one will find, in the soil of a district, some new power to supply human needs, he can endow that district with a new industry. If he [43] will invent a mode of treating some natural deposit, ore or clay for instance, so as to provide a tool or utensil which is cheaper and more convenient than what is in use, he can create an industry. If he will find out some new and better way to raise cattle or vegetables, which is, perhaps, favored by the climate, he can do the same. If he invents some new treatment of wool, or cotton, or silk, or leather, or makes a new combination which produces a more convenient or attractive fabric, he may do the same. The telephone is a new industry. What measures the gain of it? Is it the “employment” of certain persons in and about telephone offices? The gain is in the satisfaction of the need of communication between people at less cost of time and labor. It is useless to multiply instances. It can be seen what it is to “create an industry.” It takes brains and energy to do it. How can taxes do it?

38. Suppose that we create an industry even in this sense, What is the gain of it? The people of Connecticut are now earning their living by employing their labor and capital in certain parts of the industrial organization. They have changed [44] their “industries” a great many times. If it should be found that they had a new and better chance hitherto undeveloped, they might all go into it. To do that they must abandon what they are now doing. They would not change unless gains to be made in the new industry were greater. Hence the gain is the difference only between the profits of the old and the profits of the new. The protectionists, however, when they talk about “creating an industry,” seem to suppose that the total profit of the industry (and some of them seem to think that the total expenditure of capital) measures their good work. In any case, then, even of a true and legitimate increase of industrial power and opportunity, the only gain would be a margin. But, by our definition, “a protective duty has for its object to effect the diversion of a part of the capital and labor of the people out of the channels in which it would otherwise run.” Plainly this device involves coercion. People would need no coercion to go into a new industry which had a natural origin in new industrial power or opportunity. No coercion is necessary to make men buy dollars at 98 cents apiece. The case for coercion is when it is desired to make them [45] buy dollars at 101 cents apiece. Here the states” man with his taxing power is needed, and can do something. What? He can say: “If you will buy a dollar at 101 cents, I can and will tax John over there two cents for your benefit; one to make up your loss and the other to give you a profit.” Hence, on the protectionist's own doctrine, his device is not needed, and can not come into use, when a new industry is created in the true and only reasonable sense of the words, but only when and because he is determined to drive the labor and capital of the country into a disadvantageous and wasteful employment.

39. Still further, it is obvious that the protectionist, instead of “creating a new industry,” has simply taken one industry and set it as a parasite to live upon another. Industry is its own reward. A man is not to be paid a premium by his neighbors for earning his own living. A factory, an insane asylum, a school, a church, a poor-house, and a prison can not be put in the same economic category. We know that the community must be taxed to support insane asylums, poor-houses, and jails. When we come upon such institutions we see them with regret. They are wasting [46] capital. We know that the industrious people all about, who are laboring and producing, must part with a portion of their earnings to supply the waste and loss of these institutions. Hence the bigger they are the sadder they are.

40. As for the schools and churches, we know that society must pay for and keep up its own conservative institutions. They cost capital and do not pay back capital directly, although they do indirectly, and in the course of time, in ways which we could trace out and verify, if that were our subject. Here, then, we have a second class of institutions.

41. But the factories and farms and foundries are the productive institutions which must provide the support of these consuming institutions. If the factories, etc., put themselves on a line with the poor-houses, or even with the schools, what is to support them and all the rest too? They have nothing behind them. If in any measure or way they turn into burdens and objects of care and protection, they can plainly do it only by part of them turning upon the other part, and this latter part will have to bear the burden of all the consuming institutions, including [47] the consuming industries. For a protected factory is not a producing industry. It is a consuming industry! If a factory is (as the protectionist alleges) a triumph of the tariff, that is, if it would not be but for the tariff (and otherwise he has nothing to do with it), then it is not producing; it is consuming. It is a burden to be borne. The bigger it is the sadder it is.

42. If a protectionist shows me a woolen mill and challenges me to deny that it is a great and valuable industry, I ask him whether it is due to the tariff. If he says no, then I will assume that it is an independent and profitable establishment, but then it is out of this discussion as much as a farm or a doctor's practice. If he says yes, then I answer that the mill is not an industry at all. We pay sixty per cent. tax on cloth simply in order that that mill may be. It is not an institution for getting us cloth, for, if we went into the market with the same products which we take there now and if there were no woolen mill, we should get all the cloth we want, but the mill is simply an institution for making cloth cost per yard sixty per cent. more of our products than it otherwise would. That is the one and only function which the mill [48] has added, by its existence, to the situation. I have called such a factory a “nuisance.” The word has been objected to. The word is of no consequence. He who, when he goes into a debate, begins to whine and cry as soon as the blows get sharp, should learn to keep out. What I meant was this: A nuisance is something which by its existence and presence in society works loss and damage to the society—works against the general interest, not for it. A factory which gets in the way and hinders us from attaining the comforts which we are all trying to get,—which makes harder the terms of acquisition when we are all the time struggling by our arts and sciences to make those terms easier, is a harmful thing, and noxious to the common interest.

43. Hence, once more, starting from the protectionist's hypothesis, and assuming his own doctrine, we find that he can not create an industry. He only fixes one industry as a parasite upon another, and just as certainly as he has intervened in the matter at all, just so certainly has he forced labor and capital into less favorable employment than they would have sought if he had let them alone. When we ask which “channels” those [49] are which are to be “favored or created by law,” we find that they are, by the hypothesis, and by the whole logic of the protectionist system, the industries which do not pay. The protectionists propose to make the country rich by laws which shall favor or create these industries, but these industries can only waste capital, so that if they are the source of wealth, waste is the source of wealth. Hence the protectionist's assumption that by his system he could correct our errors and lead us to greater prosperity than we would have obtained under liberty, has failed again, and we find that he wastes what power we do possess.

F.): Examination of the Proposal to Develop our Natural Resources.

44. “But,” says the protectionist, “do you mean to say that, if we have an iron deposit in our soil, it is not wise for us to open and work it?” “You mean, no doubt,” I reply, “open and work it under protective help and stimulus; for, if there is an iron deposit, the United States does not own it. Some man owns it. If he wants to open and work it, we have nothing to do but wish him God-speed.” “Very well,” he says, “understand [50] it that he needs protection.” Let us examine this case then, and still we will do it assuming the truth of the protectionist doctrine. Let us see where we shall come out.

The man who has discovered iron (on the protectionist doctrine), when there is no tax, does not collect tools and laborers and go to work. He goes to Washington. He visits the statesman, and a dialogue takes place.

Iron man.—“Mr. Statesman, I have found an iron deposit on my farm.”

Statesman.—“Have you, indeed? That is good news. Our country is richer by one new natural resource than we have supposed.”

Iron man.—“Yes, and I now want to begin mining iron.”

Statesman.—“Very well, go on. We shall be glad to hear that you are prospering and getting rich.”

Iron man.—“Yes, of course. But I am now earning my living by tilling the surface of the ground, and I am afraid that I can not make as much at mining as at farming.”

Statesman.—“That is indeed another matter. Look into that carefully and do not leave a better industry for a worse.”

[51]Iron man.—“But I want to mine that iron. It does not seem right to leave it in the ground when we are importing iron all the time, but I can not see as good profits in it at the present price for imported iron as I am making out of what I raise on the surface. I thought that perhaps you would put a tax on all the imported iron so that I could get more for mine. Then I could see my way to give up farming and go to mining.”

Statesman.—“You do not think what you ask. That would be authorizing you to tax your neighbors, and would be throwing on them the risk of working your mine, which you are afraid to take yourself.”

Iron man (aside).—“I have not talked the right dialect to this man. I must begin all over again. (Aloud). Mr. Statesman, the natural resources of this continent ought to be developed. American industry must be protected. The American laborer must not be forced to compete with the pauper labor of Europe.”

Statesman.—“Now I understand you. Now you talk business. Why did you not say so before? How much tax do you want?”

[52]The next time that a buyer of pig iron goes to market to get some, he finds that it costs thirty bushels of wheat per ton instead of twenty.

“What has happened to pig-iron?” says he.

“Oh! haven't you heard?” is the reply. “A new mine has been found down in Pennsylvania. We have got a new ‘natural resource.’”

“I haven't got a new ‘natural resource,’” says he. “It is as bad for me as if the grasshoppers had eaten up one.third of my crop.”

45. That is just exactly the significance of a new resource on the protectionist doctrine. We had the misfortune to find emery here. At once a tax was put on it which made it cost more wheat, cotton, tobacco, petroleum, or personal services per pound than ever before. A new calamity befell us when we found the richest copper mines in the world in our territory. From that time on it cost us five (now four) cents a pound more than before. By another catastrophe we found a nickel mine, thirty cents (now fifteen) a pound tax! Up to this time we have had all the tin that we wanted above ground, because beneficent nature has refrained from putting any underground in our territory. In the metal schedule, where the metals [53] which we unfortunately possess are taxed from forty to sixty per cent., tin alone is free. Every little while a report is started that tin has been found. Hitherto these reports have happily all proved false. It is now said that tin has been found in West Virginia and Dakotah. We have reason to devoutly hope that this may prove false, for, if it should prove true, no doubt the next thing will be forty per cent. tax on tin. The mine-owners say that they want to exploit the mine. They do not. They want to make the mine an excuse to exploit the taxpayers.

46 . Therefore, when the protectionist asks whether we ought not by protective taxes to force the development of our own iron mines, the answer is, that, on his own doctrine, he has developed a new philosophy, hitherto unknown, by which “natural resources” become national calamities, and the more a country is endowed by nature the worse off it is. Of course, if the wise philosophy is not simply to use, with energy and prudence, all the natural opportunities which we possess, but to seek “channels favored or created by law,” then this view of natural resources is perfectly consistent with that philosophy, for it is [54] simply saying over again that waste is the key of wealth.

G.): Examination of the Proposal to Raise Wages.

47. “But,” he says again, “we want to raise wages and favor the poor working man.” “Do you mean to say,” I reply, “that protective taxes raise wages—that that is their regular and constant effect?” “Yes,” he replies, “that is just what they do, and that is why we favor them. We are the poor man's friends. You free-traders want to reduce him to the level of the pauper laborers of Europe.” “But here, in the evidence offered at the last tariff discussion in Congress, the employers all said that they wanted the taxes to protect them because they had to pay such high wages.” “Well, so they do.” “Well then, if they get the taxes raised to help them out when they have high wages to pay, how are the taxes going to help them any unless the taxes lower wages? But you just said that taxes raise wages. Therefore, if the employer gets the taxes raised, he will no sooner get home from Washington than he will find that the very taxes which he has just secured have raised wages. Then he must go [55] back to Washington to get the taxes raised to offset that advance, and when he gets home again he will find that he has only raised wages more, and so on forever. You are trying to teach the man to raise himself by his boot straps. Two of your propositions brought together eat each other.”

48. We will, however, pursue the protectionist doctrine of wages a little further. It is totally false that protective taxes raise wages. As I will show further on (§ 91 and following), protective taxes lower wages. Now, however, I am assuming the protectionist's own premises and doctrines all the time. He says that his system raises wages. Let us go to see some of the wages class and get some evidence on this point. We will take three wage-workers, a boot-man, a hat-man, and a cloth-man. First we ask the boot-man, “Do you win any thing by this tariff?” “Yes,” he says, “I understand that I do.” “How?” “Well, the way they explain it to me is that when any body wants boots he goes to my boss, pays him more on account of the tax, and my boss gives me part of it.” “All right! Then your comrades here, the hat-man and the cloth-man, pay this tax in which you share?” “Yes, I suppose [56] so. I never thought of that before. I supposed that rich people paid the taxes, but I suppose that when they buy boots they must do it too.” “And when you want a hat you go and pay the tax on hats, part of which (as you explain the system) goes to your friend the hat-man; and when you want cloth you pay the tax which goes to benefit your friend the cloth-man?” “I suppose that it must be so.” We go then to see the hat-man and have the same conversation with him, and we go to see the cloth-man and have the same conversation with him. Each of them then gets two taxes and pays two taxes. Three men illustrate the whole case. If we should take a thousand men in a thousand industries we should find that each paid 999 taxes, and each got 999 taxes, if the system worked as it is said to work. What is the upshot of the whole? Either they all come out even on their taxes paid and received, or some of the wage receivers are winning something out of other wage receivers to the net detriment of the whole class. If each man is creditor for 999 taxes, and each debtor for 999 taxes, and if the system is “universal and equal,” we can save trouble by each drawing 999 orders on the creditors to pay [57] to themselves their own taxes, and we can set up a clearing house to wipe off all the accounts. Then we come down to this as the net result of the system when it is “universal and equal,” that each man as a consumer pays taxes to himself as a producer. That is what is to make us all rich. We can accomplish it just as well and far more easily, when we get up in the morning, by transferring our cash from one pocket to the other.

49. One point, however, and the most important of all, remains to be noticed. How about the thousandth tax? How is it when the boot-man wants boots, and the hat-man hats, and the cloth-man cloth? He has to go to the store on the street and buy of his own boss, at the market price (tax on) the very things which he made himself in the shop. He then pays the tax to his own employer, and the employer, according to the doctrine, “shares” it with him. Where is the offset to that part which the employer keeps? There is none. The wages-class, even on the protectionist explanation, may give or take from each other, but to their own employers, they give and take not. At election time the boss calls them in and tells them that they must vote for protection [58] or he must shut up the shop, and that they ought to vote for protection, because it makes their wages high. If, then, they believe in the system, just as it is taught to them, they must believe that it causes him to pay them big wages, out of which they pay back to him big taxes, out of which he pays them a fraction back again, and that, but for this arrangement, the business could not go on at all. A little reflection shows that this just brings up the question for a wage-earner: How much can I afford to pay my boss for hiring me? or, again, which is just the same thing in other words: What is the net reduction of my wages below the market rate under freedom which results from this system? (see § 65).

50. Let it not be forgotten that this result is reached by accepting protectionism and reasoning forward from its doctrines and according to its principles. In truth, the employés get no share in any taxes which the boss gets out of them and others (see § 91 fg. for the truth about wages). Of course, when this or any other subject is thoroughly analyzed, it makes no difference where we begin or what line we follow, we shall always reach the same result if the result is correct. If [59] we accept the protectionist's own explanation of the way in which protection raises wages we find that it proves that protection lowers wages.

H.): Examination of the Proposal to Prerent Competition by Foreign Pauper Labor.

51. The protectionist says that he does not want the American laborer to compete with the foreign “pauper laborer” (see § 99). He assumes that if the foreign laborer is a woolen operative, the only American who may have to compete with him is a woolen operative here. His device for saving our operatives from the assumed competition is to tax the American cotton or wheat grower on the cloth he wears, to make up and offset to the woolen operative the disadvantage under which he labors. If then, the case were true as the protectionist states it, and if his remedy were correct, he would, when he had finished his operation, simply have allowed the American woolen operative to escape, by transferring to the American cotton or wheat grower the evil results of competition with “foreign pauper labor.”

I.): Examination of the Proposal to raise the Standard of Public Comfort.

52. But the protectionist reiterates that he wants to make our people well off, and to diffuse general prosperity, and he says that his system does this. He says that the country has prospered under protection and on account of it. He brings from the census the figures for increased wealth of the country, and, to speak of no minor errors, draws an inference that we have prospered more than we should have done under free trade, which is what he has to prove, without noticing that the second term of the comparison is absent and unattainable. In the same manner I once heard a man argue from statistics, who showed by the small loss of a city by fire that its fire department cost too much. I asked him if he had any statistics of the fires which we should have had but for the fire department (see § 102).

53. The people of the United States have inherited an untouched continent. The now living generation is practicing bonanza farming on prairie soil which has never borne a crop. The population is only 15 to the square mile. The population of England and Wales is 446 to the square [61] mile; that of the British Islands 290; that of Belgium 481; of France 180; of Germany 216. Bateman* estimates that in the better part of England or Wales a peasant proprietor would need from 4½ to 6 acres, and, in the worse part, from 9 to 45 acres on which to support “a healthy family.” The soil of England and Wales, equally divided between the families there, would give only 7 acres apiece. The land of the United States, equally divided between the families there, would give 215 acres apiece. These old nations give us the other term of the comparison by which we measure our prosperity. They have a dense population on a soil which has been used for thousands of years; we have an extremely sparse population on a virgin soil. We have an excellent climate, mountains full of coal and ore, natural highways on the rivers and lakes, and a coast indented with sounds, bays, and some of the best harbors in the world. We have also a population of good national character, especially as regards the economic and industrial virtues. The sciences and arts are highly cultivated among us, and [62] our institutions are the best for the development of economic strength. As compared with old nations we are prosperous. Now comes the protectionist statesman and says: “The things which you have enumerated are not the causes of our comparative prosperity. Those things are all vain. Our prosperity is not due to them. I made it with my taxes.”

54 (a) In the first place the fact is that we surpass most in prosperity those nations which are most like us in their tax systems, and those compared with whom our prosperity is least remarkable are those which have by free trade offset as much as possible the disadvantage of age and dense population. Since, then, we find greatest difference in prosperity with least difference in tax, and least difference in prosperity with greatest difference in tax, we can not regard tax as a cause of prosperity, but as an obstacle to prosperity which must have been overcome by some stronger cause. That such is the case lies plainly on the face of the facts. The prosperity which we enjoy is the prosperity which God and nature have given us minus what the legislator has taken from it.

55 (b) We prospered with slavery just as we [63] have prospered with protection. The argument that the former was a cause would be just as strong as the argument that the latter is a cause.