William Graham Sumner, Lectures on the History of Protection in the United States (1877)

|

|

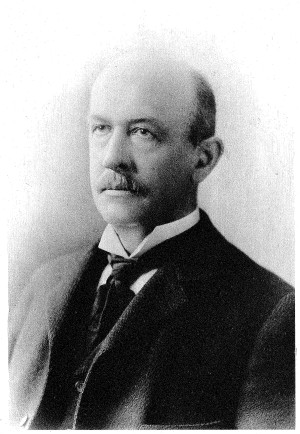

| William Graham Sumner (1840-1910) |

This is part of a collection of works by William Graham Sumner.

Source

William Graham Sumner, Lectures on the History of Protection in the United States delivered before the International Free Trade Alliance. Reprinted from “The New Century” (Published for the International Free Trade Alliance by G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1877).

See the facs. PDF.

Also see his longer book-length work on Protectionism (1888) [HTML and facs. PDF] and his survey of "Free Trade" written for the Nouveau Dictionnaire d'Économie politique (189-92) [en français in HTML and facs. PDF].

Table of Contents

- Lecture I. The National Idea and the American System - 7

- Lecture II. Broad Principles underlying the Tariff Controversy - 11

- Lecture III. The Origin of Protection in this Country - 17

- Lecture IV. The Establishment of Protection in this Country - 34

- Lecture V. Vacillation of the Protective Policy in this Country — Conclusion - 49

[3]

PREFACE.↩

The following lectures were delivered by me before the International Free Trade Alliance, in New York, in the spring of 1876. They are here republished exactly as delivered, although there are certain points which I should like to elaborate, if the opportunity were offered. I have endeavored here to combine two things : 1st, the history of our own tariff legislation, showing its weakness, ignorance, confusion, and oscillation ; and, 2d, a discussion of the arguments for and against free trade, as they have presented themselves in the industrial and legislative history of the country. I have summed up in the last lecture the convictions to which such a study of the subject must lead. Suffice it here to say, that when one clears one's head of all the sophistries and special pleas by which protection is usually defended, and looks at the matter as a simple matter of common sense, one must be convinced that an industrious people on a fertile soil, so abundant in extent that population is inadequate to the highest organization of labor, must enjoy advancing wealth and prosperity. They will owe this to a diligent use of their natural advantages. They will reach the maximurn of production when they produce and exchange most freely. Certainly no application of taxation can possibly increase their production ; that is their national wealth. Every tax or other interference with the freedom of production or exchange produces restraint, confusion, delay, change, risk and vexation, and these, as every one knows, cause loss of time, labor, and capital, that is, diminish the product which may be obtained from a given amount of labor. The amount of this loss can never be measured in figures, because we can never get statistics of " what might have been ;" but when it is shown here that the legislation of the United States has been constantly vacillating, not only in its policy, but also in the degree to which its policy has been pursued ; that it has laid burdens on production and exchange in a clumsy, brutal, and ignorant disregard of possible effects on the delicate network of modern industry; that it has had in view, from point to point, only a single interest, and has had no national stand-point or conception of the public interest (much as it boasts to the contrary) ; then, I think, any one must see that such legislation has lamed the national productive power, wasted the natural advantages which the nation enjoys, diminished its wealth, and contracted the general status of comfort for the whole people.

[4]

Adam Smith laid down four rules by which all taxes ought to he tested. Experience has ratified them so thoroughly that they are no longer questioned by anybody. They ought to be known by everybody.

1. Taxes should be, as far as practicable, equal.

2. They should be definite in amount (not uncertain or variable).

3. They should be collected, so far as possible, at the time most convenient to the payer, so as not to cripple the process of production.

4. They should be so arranged as to give the maximum revenue to the government at the minimum cost to the people, i. e., they should cost as little as possible to collect ; and they should keep capital out of the hands of the people as short time as possible.

Protective taxes are hostile to revenue, because the purpose of a protective tax is to prevent importations. The moment, however, that a tax begins to have this effect it prevents revenue. Hence, where protection legins, there revenue ends.,

There is no conceivable ground of right by which the legislature may decide what things ought to be produced, and in what measure, and then use its taxing power to carry out its notions. Every tax is an evil, and it is on the defensive. Its need must be shown, and no tax can he defended which is laid for anything but revenue to defray the legitimate and necessary cost of public peace, order, and security.

For taxes laid to this end, some further rules can now be laid down as established by long experience.

1. No such taxes should be allowed to act protectively to any degree. They should be offset by excise taxes of equivalent amount.

2. They should be laid on as few articles as possible, and in the simplest way possible (to avoid expense in collection).

3. The legislator should try to find the maximum revenue point on each article (i. e., If there were no tax there would be no revenue. If there were a prohibitory tax there would be no revenue. There is a point between, at which the highest revenue can be obtained with the least cost and the least fraud).

4 Eaw materials should not be taxed. (It is not easy to define "raw materials," but the rule has value as a practical rule. Taxes on raw materials strangle industry at its birth.)

These rules are only practical rules, derived from experience. There are no scientific laws of taxation, because there are no natural laws of taxation. Nature has not provided for taxation, as she has for production, exchange, distribution, and consumption. Taxation is part of the co-operation of society for its own defense against the evil and destructive forces within itself. Any state which lays protective taxes misuses the means of defense to increase the evils.

W. G. S.

[7]

LECTURE I. The National Idea and the American System.↩

It is a sign of a dogma in dissolution to change its form and to yield points of detail, while striving to guard its vested interests and traditional advantages. Just now the dogma of protection is striving to find standing ground, after a partial retreat, for a new defense, in the doctrine of nationality. We are told that there is only a " national " and not a "political" economy, that there are no universal laws of exchange, consequently no science of political economy; that it is only an art, and has only an empirical foundation, and that it varies with national circumstances to such a degree as to be controlled by nothing higher than traditional policy or dogmatic assumption. Great comfort is found for this position in. the assertion that the German economists have discovered or adopted its truth. How utterly unjust and untrue this is as a matter of fact, those who have read the works of the German economists must know. It is untrue, in the first place, that they are unanimously of the school of the socialistes en chaire, and, in the second place, it is untrue that the socialistes en chaire are clear and unanimous in their position. They occupy every variety of position, from extreme willingness to entrust the state with judgnient in the application of economical prescriptions, to the greatest conservatism in that regard. Finally, it is not true that any of them are protectionists.

We do not intend, however, to discuss the opinion or authority of the schools in question. If it should be claimed that the extreme admission made by some of the Germans of this school, that protection may be beneficial to a nation at a certain stage of development, is applicable to the United States to-day, we should desire no better footing for the controversy.

It is more directly interesting, however, to examine the doctrine of nationality on its merits. It will appear upon even a cursory examination of this kind, that existing nations are arbitrary and traditional divisions. There was published in Europe, in 1863, when the Emperor Napoleon was urging on an attempt to secure stable equilibrium in European politics by adjusting political divisions according to race and language divisions, a map of Europe thus rationally constructed. The effort, however, offered the most striking proof of the impossibility of reconstructing, on any such rationalistic or logical basis, political circumstancea [8] which are the historical outgrowth of political struggles and political accidents. The nations which must be made the subject of discussion are, therefore, such as exist, and of them it is true that their boundaries coincide with no lines of race, language, culture, industry, commerce, or anything else which would give the basis of scientific classification, so that different principles could be consistently applied in each. There was a time, indeed, when the civil subdivisions were small and numerous — when manners, customs, costumes and language varied over every hundred square miles of Europe — but the whole tendency of the great inventions of modern times is to obliterate these boundary lines for purposes of industry and trade.

It is not necessary to go into the history of Europe for proofs and illustrations. The very best are furnished by our own continent and our own nation. The geographical area known to-day as the United States is the result of discovery, conquest and purchase. It would have been impossible a century ago to constitute an empire of such extent, and to govern it according to the requirements of modern life. The improvements in transportation and the transmission of intelligence have made it physically possible, and the combination of local institutions with a centralized organization has made it politically possible.

When we turn to inquire, however, why it has been limited just as it has, why Canada and Mexico are outside, and why Texas, California and Alaska are within, we come at once to the historical antecedents which are partly accidents and partly ancient struggles and hostilities. Canada was never made thoroughly English before the revolutionary war; while it was French it was always hostile to the English colonies. This hostility was traditional, and there was no sympathy with the revolution. New Brunswick and Nova Scotia were largely peopled by the Tory refugees, whom the unwise severity of the Whigs forced to emigrate during and after the war. Texas was won from Mexico in war. California and the other Pacific States were obtained partly by conquest and partly by purchase. A few years ago we discussed a plan for purchasing San Domingo. Out of these historical movements, part of which fell out one way and part the other, the actual geographical limits of the United States result.

Now, according to the Constitution of the United States, no one of these States can make any laws restricting commerce between itself and any of the others. If it be asserted that states which pursue different industries cannot afford to trade freely with one another, here we have them — New York and Pennsylvania, Massachusetts and Minnesota, Maine and Louisana. If it be asserted that states with like industries cannot afford to trade freely with one another, here we have them — Indiana and Illinois, Iowa and Minnesota, Massachusetts and Ehode Island, Alabama [9] and Mississippi. If it be said that small States cannot aflford to trade freely with great empires, here are New York and Connecticut, Pennsylvania and Delaware. Why do not the great states suck the life out of the small ones ? If it be said that new states with little capital, and on the first stage of culture, cannot afford to exchange freely with old states having large capital and advanced social organization, here are New York and Oregon, Massachusetts and Idaho. How can any territories ever grow into states under the pressure ? If it be said that a state which relies on one industry cannot afford to exchange freely with one which has a diversified industry, here are Pennsylvania and Colorado, California and Nevada, any of the cotton states and any of the north-eastern states. No such strong illustrations are furnished by any states in the world which are sovereign and independent of each other. The Constitution of the Union enforces absolute freedom of exchanges, and each state pays its own taxes and supports its own government. The traveler rarely knows when he passes from one state to another. As to what he buys or where he buys, what he sells or where he sells, it would be considered an unwarrantable impertinence for any public official to inquire. Yet no man has ever been known, so far as we are aware, to complain of this as a hardship, or as imposing a loss upon him, and no such complaint has arisen from any state as a state, nor has any one been heard to claim that there was here an actual loss, which must be endured for the sake of the great benefits which come from Union. On the contrary, it is universally and tacitly agreed that this is one of the great benefits of the Union.

Here, however, comes in another phase of the matter. If a man lives in Vermont he must trade freely with New Hampshire, Massachusetts and New York, but if he wants to trade northward to Canada, it is regarded as fatal to him and to his country, that he should do so freely. As we won Texas from Mexico, we enter into absolute free trade with her, but we think that it would be ruinous to trade freely with the rest of the ancient state of Mexico. If we had got the political jurisdiction of San Domingo, we should have entered into free exchanges with her, but the difficulty of the political jurisdiction was the main ground of the wise decision of the nation not to buy that island. If, however, we cannot have the trouble of the political jurisdiction, we think it would be calamitous to have the free exchanges. Free exchanges with Cuba are not to be thought of on our part, even if they would be granted on hers.

Here, then, the refutation of the " nationality " notion is right before us, and it is at the same time the condemnation of our policy in regard to [foreign commerce. If there be any such thing as an "American system " — a system which we can claim to illustrate and advocate before the civilized world, it must be that of absolute free trade, each state or [10] nation providing for its own needs and expenses, each state freely open to all comers, securing peace and safety to persons and property while within its borders.

The " British system " is different, and is distinctly defined. It is to raise revenue by customs for convenience, and to lay excises to counteract " incidental protection." We would be very glad to see the British system introduced into this country, but if the protectionists taunt freetraders with flinching from the consequences of their doctrine, we accept the challenge. We are convinced by the experience of the United States, that the best system would be to have absolutely free exchanges, and to leave each nation to pay the expense of maintaining the organization of society within its own borders.

Another application of the facts here discussed which is put to us, is deserving of far less respectful treatment. It is said that we have free trade already within the Union, and that we are discontented and unreasonable, because we demand more. It would be difficult to show why a man who has ten thousand dollars should not sue for ten thousand more which are due him, or why a man who enjoys the right of locomotion is unreasonable in demanding the right of association.

There is in all that we have said no infringement upon the true idea of the " nation," and no derogation from its value and dignity. It exists historically and traditionally, and we take it as it is handed down to us. It is an organized human society, whose limits are given historically, and are maintained for convenience, because they allow play to certain local interests, prejudices, traditions, habits and customs. Whether it is formed by accident and immemorial tradition, or by colonization and legislative act, it develops an organic life. The society as such develops functions. Its harmonious action emanates from its individual members and reacts upon them. Its government is the machinery by which harmony, co-operation and unity are brought about. It would seem, however, that America had done its greatest service to the world by showing that states did not exist, for the sake of bringing men into convenient groups for making either commercial or military war upon each other, but that they might more easily embrace the earth in a family of harmonious communities.

[11]

LECTURE II. Broad Principles underlying the Tariff Controversy.↩

The world has heard a great deal about liberty for the last century. That period has been marked by great struggles on the part of nations to secure independence, and on the part of classes and individuals to secure freedom from old traditional restraints. The world has struggled towards "freedom" and "liberty" as if these were the first considerations of peace, justice, prosperity and happiness, and the result has been to produce, in the forefront of modern civilization, states whose fundamental principle is to give the freest scope to individual energy and effort.

We in the United States make it our greatest boast that we have accepted this broad principle absolutely, and applied it fearlessly ; nevertheless, we, who are met here to-night, are associated to demand more liberty. There is no body of our fellow-citizens worth mentioning who deny the right and the expediency of private property. What we have to demand, and what the majority of our fellow-citizens — so far as their will has yet been constitutionally expressed — deny us, is the privilege of using our property as we like, that is, of exchanging it when and where and with whomsoever we will. When we demand this privilege, which belongs to us on the simplest principles of right reason and common sense, we are met by a speculative theory based on artificial assumptions, put forward sometimes on bare considerations of selfish interest, and sometimes with no little parade of abstract philosophizing. We are told, " Oh, no! It is not best for the state that you should do as you like about making your exchanges. The legislature must consider the question, and prescribe for you with whom and for what you shall exchange. If you deal with the designated persons, your countrymen, they will gain, the wealth of the community will increase, and you, as a member of the community, will participate, and be better off in the end than if you had been let alone."

Now, we dispute this theory at every stage. We deny that the state, i. e., the legislature, can make any such provision for us better than we can make for ourselves, and we appeal to experience of everything it tries to do; we deny that it has any business to theorize for us in the premises ; we deny that the designated persons will gain — at least, that they will gain as much as they would if they were left to deal with us on their own footing ; we deny that they can gain anything from us, on [13] account of the law, but wliat we lose; we deny that the total gains to one part of society by this process can ever exceed the total losses of another part, i. e., that the process can increase the wealth of the community; we deny, finally, that our share of these hypothetical gains can ever be redistributed to us so as to bring back our first loss. We have never seen money go through such a process, passing through many hands, and come back whole, to say nothing of loss and waste.

Thus the issue is joined. On the one side are broad and simple principles, so elementary that they are mere truisms, and on the other side are special pleas of various kinds set up to befog men's judgment, and prevent them from drawing the inferences which follow inevitably.

Let me suggest to you two or three ot the hroadest and most commanding principles which really decide this question :

1. We, Americans, have made it the first principle of our society that no man shall obtain by law any advantage in the race of life on account of birth or rank, or any traditional or fictitious privilege of any kind whatsoever, and on the other hand, we have removed, so far as the law can remove, all the hindrances and stumbling blocks which come from circumstances of birth and family. Society gives no aid, but it removes all obstacles of social prejudice and tradition. There is not a man in the country who does not respond with a full heart to the wisdom and truth of this relation of society to the individual. Now, on what principle is this relation based? It is on the belief that society makes the most of its members in that way. Some men have more in them than others. We do not know which is which until they show it; but we believe that the way to let each one come to his best, is for society to set them all on their feet, and then let them run each for himself. We believe that the best powers of the community are brought out in that way.

It does not follow that men so treated never make mistakes, and never ruin themselves. We see them do this every day; but if it were proposed that the state should interfere, few would be led astray by the proposition.

The same principle applies to trade directly and completely. The productive powers of men and communities differ, but whatever they are, more or less, they reach their maximum under liberty. The total of national wealth is greatest where each disposes of his own energy in production and exchange with the least interference. This is not saying that none will make mistakes, or that free trade will eliminate all ills from human life. Free trade will not make the idle enjoy the fruits of industry, nor the thriftless possess the rewards of economy. Poverty, pain, disease, misery will remain as long as idleness and vice remain. Free trade will only act in its own measure and way, to leave men face to [13] face with these things, with a somewhat better chance to conquer them. It is one of the great vices of protection that it makes the industrious suffer for the idle, and the energetic and enterprising bear the losses of the stupid.

2. If, now, you examine the opposite theory you will find that it assumes that we or our ancestors all made a great mistake in coming to this country and trying to live here. We are told that a tariff is necessary to "make a market" for our farmers, that a tariff is necessary to keep our manufactures from destruction, that navigation laws arc necessary to preserve our shipping. Some of the old countries support a population twenty or thirty times as dense as ours with little or nothing of this artificial system. If, then, we are not able to live here without this aid, we must have left a part of the world where life is easier for one where it is harder. This brings me, then,

3. To the great fundamental error of the theory, viz. : That taxation is a productive force. No emigrants go to the desert of Sahara. None would go to New York if it were sand and rocks. If, however, New York is a part of the earth's surface, consisting of arable land fit to produce food for man ; if it is intersected by mountains, covered by forests, and containing iron and coal, and if it possesses great rivers and a splendid harbor, then the conditions of supporting human life are fulfilled. It requires only labor and capital to build up there a great and prosperous community. It is plain that some parts of the earth's surface contain more materials for man's use than others, and the fact as to New York will affect the wealth of its inhabitants. It is plain that it makes a difference whether the people are idle or industrious, listless or energetic, sluggish or enterprising. It is plain that it makes a difference how much capital they have, or whether there are enough of them for the best distribution of labor. It is plain that it makes a difference what is the state of the arts and sciences, and what are the facilities of transportation.

The wealth of New York at any given time must depend on the way in which these factors are combined. Now the question arises : How can taxation possibly increase the product ? Which one of the factors does it act upon ?

Just consider what taxation is. "We pay taxes, in the first place, to pay for the necessary organization of society, in order that we may act together, and not at cross purposes like a mob ; but if that were all the state had to do taxes would be very small. We must support courts and police, and army and navy. These we need for peace, and justice, and security. But suppose that there were none who had the will to rob, or to swindle, or to cheat, or to do violence, the expenditures under this head would dwindle to nothing. It follows that taxes are the tribute we pay [14] to avarice, and violence, and rapine, and all the other vices which disfigure human nature. Taxes are only those evils translated into money and spread over the community. They are so much taken from the strength of the laborer, or the fertility of the soil, or the benefit of the climate. They are loss and waste to almost their entire extent.

This is the function of government, then, which it is proposed to use to create value, to do what men can do only by applying labor and capital to land. Let us take a case to test it. Let us suppose that no woolen cloth is made in New York, but that a New York farmer, at the ead of a certain time, has ten bushels of wheat, of which one bushel will buy a yard of imported cloth. After the exchange then he has nine bushels of wheat and one yard of cloth. If any one could make cloth in New York as easily as he could raise a bushel of wheat, some one would do it as soon as there was unemployed labor and capital, and that would be the end of the matter ; but if no one undertakes the business it must be because labor and capital are all employed, or because it takes more labor and capital to produce a yard of cloth than a bushel of wheat. Let us suppose that it would take as much as a bushel and a half of wheat. Now, a protectionist proposes to the state to tax imported cloth one-half bushel of wheat per yard. If his plan is carried out the difficulty of obtaining imported cloth is raised to one bushel and a half of wheat per yard, which is the rate of difficulty at which it can be produced in New York. The protectionist then begins and offers his cloth at a bushel and a half per yard. The farmer who, as before, has produced ten bushels, now buys at the new rate, and after the exchange stands possessed of eight and a half bushels of wheat and one yard of cloth. Whither has the other half bushel gone ? It has gone to make up a fund to hire some men to make life in New York harder than God and nature made it. From time to time we are told how much "our industries have increased." So far as their increase is in fact due to this arrangement, it is only a proof how much mischief has been done. This application of taxation does not alter the nature of taxation, it only extends its effects arbitrarily and needlessly, and inflicts upon the people a greater measure than they need otherwise bear of the burden which is due to robbery, injustice, war, famine and the other social ills.

4. Protection is, moreover, hostile to improvements. We are always eager to devise improved methods and to invent machinery to "save labor," but every such improvement which we introduce involves the waste and destruction of a great deal of capital. Old machinery must be discarded, although it is not worn out. This loss is not incurred by anybody willingly ; it is enforced by competition. When, therefore, competition is withdrawn or limited the incentive to improvement is lessened or destroyed. This applies especially in manufactures where the international [15] competition is cut off by protective duties. The same principle that protection resists improvement applies even more distinctly to those improvements wliich are made in transportation. In spite of their theories men rejoice in all the improved means of communication which bring nations nearer together. A new railroad or an improved steamship is regarded as a step gained in civilization. Such improvements are realized in diminished freights and diminished prices of imported goods. No sooner is this realized, however, than "foreign competition" is found to be worse than ever. An outcry goes up for "more protection," and a new tax is put on to-day to counteract what we rejoiced over yesterday as an immense gain. We spend millions to dredge out our harbors, to remove rocks and cut channels through sandbars, as if it were a gain to have communication inward and outward as free as possible, and as soon as we experience the effects in reduced cost of goods we lay a new tax, like restoring the sandbars, in order to undo our work. Indeed, to build sandbars across our harbors would be a far cheaper means of reaching the same end. Next, we find that the numerous and complicated taxes have made it impossible for us to build ships to sail across the ocean where they must come in competition with foreign ships; so we make navigation acts and forbid the purchase of ships, exclude foreigners from our coasting trade, and finally, propose bounties and subsidies, all of which must come at last out of the products of our labor, in order to try to get ships once more. It is like the man who cut a piece from his coat to mend his trowsers, a piece from his vest to replace the hole in his coat, a piece from his trowsers to restore his vest, and so on over again. Did he ever get a whole suit? He found in a little while that he had only a rag left.

"We are told, however, that if we do not do all this we shall be "inundated " with foreign goods. The word is appalling, and carries with it a fallacy which often seems to have great power. On what terms sliall we get this flood of good things ? Will they be given to us ? If so, what can we do better than to stop work and live on this generosity? Why are we, however, selected as the especial objects of this bounty, if bounty it is? Why do not England and France and Belgium and Germany pour out their inundations on Patagonia and Iceland ? The answer is plain enough. The goods are not gifts, they arc offered for exchange. Nothing can force us to buy or dictate terms of exchange ; and the inundation comes to us because we are known to be rich and able, and because we inhabit a continent prolific in some of the chief objects of human desire. It is not the beggar who, when he goes down the street, is " inundated " with wares from the various stores. If it were he would probably stem the tide with joy. It is the rich man only to whom good things are freely offered with a well understood condition; few rich men have ever been heard to complain of it. If, then, the Americans have these good things offered them [16] in exchange and they allow themselves to be worsted in the bargain, they sadly belie their reputation.

These few observations which I have now presented as bearing on this subject are very broad and comprehensive, and very sweeping in their effect. They appeal directly to common sense and right reason. They give us the correct point of view, and dispel some of the fog which has collected from habit and prejudice around this subject. They lead us right up to the doctrine which the United States have put m practice in their own internal trade — absolute freedom of exchange and local or internal taxation. We have proved the practical value of that system here over a continent. I cannot see why the same system would not be a great gain if extended over Canada, Mexico and the West Indies. I cannot see why it would not be a great gain if all South America were embraced in a confederation exactly like ours as far as this point is concerned, with absolute free trade between the states. I cannot see why all Europe would not gain by similar relations, as far as trade is concerned; and I see no reason why it should not be equally beneficent if extended to the whole civilized globe.

The objections come in the shape of stubborn prejudices and old errors attaching to narrow and special considerations. Some people dread the sweep of a great general principle, however clear and certain and scientific it may be. They dispose of it as a " theory." Well, I am a theorist. I accept the disabilities and demand the advantages of my position ; and when I find a great principle founded in an observation of facts and experience, I am not afraid to follow it up to its last corollary. The statesman must do what he can in the face of tradition and prejudice and vested interests, and I presume that it will be long before the public will be so enlightened as to demand to feel every cent that it pays in taxes for the very sake of knowing the amount, but I am clear in regard to the wisdom of such an arrangement.

la the further lectures which I am to give I propose to treat the subject historically for I believe that the tariff history of the United States shows most clearly some of the worst of the evils of the system, and I think that every one ought to know how this system has grown up and been fastened upon us.

[17]

LECTURE III. The Origin of Protection in this Country.↩

The war of American Independence was a revolt against unjust taxation. In the same year the Declaration of Independence was adopted, and Adam Smith published his "Wealth of Nations." They were two revolts, one political, the other scientific, against the prevailing dogmas of the mercantile system of political economy. They were twin incidents in the revolt of modern life against the traditions of the middle age. It is at once a pity and a surprise that the last century has seen their developments diverge instead of combining.

The revolt of the American colonies was against the " colonial system," which was itself only a part of a grand theory about the relations of nations as regards trade. According to this theory, nations were to be isolated from each other. They were not regarded as merely groups in the body of mankind, having common interests, but as distinct and separate bodies, having hostile interests, and ruled in their relations to one another by jealousy, suspicion and desire for plunder. Civilization had advanced so far that these motives were regarded inside the nation as barbarous and injurious, but they still prevailed in international relations. In regard to trade, it was believed that its object was to get possession of money — precious metals — that this was wealth, and that only one party to an exchange could gain by it. It naturally followed that complicated laws were made to control trade and drive it into the forms which men thought wiser and better than those of nature. Export duties were laid on raw materials to make them cheap ; bounties were laid on exports of manufactured goods in order to increase exports; duties were laid on imports to diminish them; prohibitions were laid on the exportation of specie, or on the exportation of machinery, or on the emigration of laborers. Navigation laws, including discriminating duties and tonnage taxes were passed. All this belonged to the great system: the effect was to isolate nations, to rob them of each other's gains in literature and the arts and sciences, and to cut off all that highest development which comes from the action of states on states.

When this system was complete and the barriers were established, nations began to put in special gates, well defended, at which they agreed to let each other in and out for special forms of trade, at particular times and under strict regulations. We ask, in astonishment, if this was trade [18] if men really believed that trade must be watched and restrained in this way. We see that the private trader cannot make his place of business too attractive, nor set the door too wide open, nor make the approach too easy, nor be too indifferent as to who comes, or how, provided he comes for honest trade. But the method we here find in use suggests only dread, suspicion and war. The machinery is that of a fortress, not that of a market.

The colonial system was only a part of this system. When the old States had all been thus isolated they began to seek possessions in the new world, with which each for itself could hold free trade but exclude all others. That is, foreign commerce was, after all, a good thing, and free trade was a good thing, if you could hold the foreign nation in subjection and coerce all its relations. If the colony could be used for the interest of the mother country, freedom, on this theory, became a good thing for trade. This theory had an obvious weakness, that if the colony ever got strong enough it would not endure this warping of all its energies in one direction, but would get independence in order to come into free relations with other nations besides its mother country. Such is the actual meaning of the American war of independence.

It would seem natural that the emancipated colonies would seek free intercourse with all nations, and it is a very curious study to see how this logical tendency conflicted for years after the revolution with inherited traditions and prejudices. On the 6th February, 1778, Gerard, Franklin, Deane and Lee made a treaty of alliance and also a treaty of commerce between Prance and the United States. In the latter treaty it was agreed to avoid " all those burthensome prejudices which are usually sources of debate, embarrassment and discontent," and to take as the " basis of their agreement the most perfect equality and reciprocity." They further refer to the general principle by which they were guided as that of " founding the advantage of commerce solely upon reciprocal utility and the just rules of free intercourse." Up to this time the principle of treaties of commerce had been that two nations made an agreement to give each other special and exclusive privileges. The Americans introduced this much of a new principle, that they would not enter into those complicated relations by which Europe, after having cut off all natural relations, had set up special, narrow, arbitrary and artificial relations between nations, but that they would hold themselves open to the freest relations they could establish with all parts of the old world.

Hence we find their representatives abroad eagerly pushing, at every opportunity, for chances to establish commercial relations. They met with all kinds of obstacles. Old habit had accustomed nations to deal with their own colonies only. They had no idea what good things the North American colonies could offer. The habit of suspicion was strong, [19] and the prevailing notions of trade led them to apprehend dangers rather than advantages from trade. On the other hand, as it had generally been believed that England had gained great advantages from her colonies, there was great eagerness to get a share in those advantages now that they were free and open, if only the aspirants had been able to find out what those advantages were and how to obtain them.

It is strange to read the correspondence of the American agents abroad, and to see how they argued and discussed with grave ambassadors about the "loss" which one nation would suffer in trading with another, any shipment of specie one way or the other being regarded as an infallible sign of loss. The Americans were by no means clear in their ideas, and did not combat these notions on principle, but apparently coincided in them. They sought equality and reciprocity, but they never rose to the height of the only true doctrine. In an exchange both parties win, or else obviously one would refuse to trade. If then one party puts obstacles in the way, the total gain is diminished, the diminution probably being divided. If the other party creates an obstacle, the gain is still further diminished or destroyed. It is a matter of regret therefore when one party is guilty of this folly, but it only doubles the mischief, and still further injures the other, if he likewise perpetrates the same folly. This is the answer to the well worn and stubborn notion that free trade must be reciprocal, or would be good if all nations would adopt it. One nation which adopts free trade gets more than it would if it put on restraints, even though all other nations may have restraints. It will share the gain if they follow its example, for the gain is multiplied at every step, but, even while they hold back, it gains as much as it can and makes the best of a bad state of things, while waiting for them to come to a better mind, if it adopts freedom. What would be thought of a grocer who refused to trade with the hatter who would sell him the best hats at the lowest price, because the hatter did not buy flour and sugar of him ?

The American ministers had little success in their efforts to make treaties such as I have described. The one with England was the one most eagerly desired. Under the prevailing notions the English had expected to suffer immense losses by the separation, but habit and the excellence of English goods revived trade immediately after the war, and the trade was found as good as ever. A treaty which would have been eagerly seized in 1783 was refused in 1785. They did not care for any treaty.

Here we come to the first case in which currency errors became intertwined with errors as to foreign trade, a junction which has run through all our history to the present moment and which has been prolific of mischief. In 1781, after the downfall of the continental currency, [20] specie became very abundant here, being bought by both French and English. The States, however, still had vast quantities of paper afloat. As soon as the war ended this specie was all exported and expended in the purchase of goods long missed. The export of specie in 1783 was ten millions. The import of goods from England in 1785 was 10 millions, and the exports 3.9 millions. In 1770 the imports were 8.5 millions, and the exports 4. 5 millions. This explains why the English were so well satisfied with the revival of trade.

During the war many industries liad sprung up to supply the wants of the people for manufactures formerly imported. At the return of peace these industries were prostrated, and a cry began to be made at that time that the country could not stand free trade, and that it must do as England had always done, that is, imitate the old restrictive system. The real demand was that some way should be found by law to continue upon the American people, by their own act, the evils which the war had inflicted on them. We shall see more of this when we come to the tariff of 1816. Whatever may have been the effect of peace to destroy the war mushrooms, we find that there were, in 1789, manufactures of iron, glass, paper and cloth here, which were boasted of as strong and prosperous, and propositions were made by competent capitalists for mining iron on a large scale in Pennsylvania, which fell only on account of the turbulency of the inhabitants and the insecurity of titles.

While things were in this state, Adams wrote from England in great disgust at the rejection of his treaty, and urged reprisals. He declared that we could get no treaty until we should set up restrictions, that is, we were to put a hindrance in the way in order to make a bargain for getting English obstacles removed by promising to remove ours. Massachusetts took this advice, but found that it drove trade away to Newport and Portsmouth. Virginia did the same, and found that she had likewise benefited Maryland and North Carolina.

Meanwhile the government of the Confederation was falling to pieces, and was a pity and a laughing stock. It had no revenues and could not pay instalments on its loans as they fell due, nor even the interest on its debt. Misery was great throughout the country, owing to paper money and debt and the losses of war. The people were discontented and rebellious, actual disorder occurring in Massachusetts, Pennsylvania and North Carolina. The Congress was begging the States to lay a uniform five per cent. duty to provide a revenue for the Confederation. The question of import tax was, therefore, bound up with the question of civil order, protection to manufactures, foreign commercial relations, and the misery arising from bad currency at home. Virginia having tried to come to an agreement with Maryland to enforce a common revenue system on the great waters of those States, this was found [21] to be impracticable without the cooperation of other States. This led to the Congress of Annapolis in 1786, which was only a commercial convention, and which found no better way to discharge the task it had undertaken than to recommend Congress to call another convention in the following year to revise the Articles of Confederation ; that is, to provide for a common revenue system, and for " the regulation of commerce," by giving the general government permanent power for those purposes. The Convention, when it met, made a complete reconstruction of the Articles of Confederation and gave us the present Constitution. You see, then, just how much truth there is in the assertion that the country was ruined by free trade during the Confederation, and that the Constitution was made to give protection.

In the Constitutional Convention, the question of free trade came up under the form of a desire for a navigation law, and it at once took a sectional form. The Eastern States wanted the Constitution chiefly in order to get such a law. The Southernmost States wanted free trade. The positions of the two sections were inverted in regard to slavery, while some of the Middle States wanted neither navigation laws nor slavery. It was one of the compromises of the Constitution that the power to regulate commerce was inserted, together with the allowance of the slave trade until 1808 (under the permission to tax slaves not over ten dollars per head), and the prohibition of export duties.

No sooner did the House of Eepresentatives get a quorum than the subject of revenue came up, and no sooner was the subject of revenue taken up than the question of protection was raised. In the debate, Madison said :

"I own myself the friend of a very free system of commerce. If industry and labor are left to take their own course they will generally be directed to those objects which are most productive, and that in a manner more certain and direct than the wisdom of the most enlightened legislature could point out. Nor do I believe that the national interest is more promoted by such legislative directions than the interest of the individuals concerned. Yet I concede that exceptions exist to this general rule, important in themselves, and claiming the particular attention of this committee. If America were to leave her ports perfectly free, and to make no discrimination between vessels owned by citizens and those owned by foreigners, while other nations make such discrimination, such a policy would go to exclude American shipping from foreign ports, and we should be materially affected in one of our most important interests."

Again, in reply to Fitzsimmons, of Pennsylvania, who wanted more protection, and wanted to discourage luxury, and made certain propositions to that end, he said : " Some of the propositions may be productive of revenue, and some may protect our domestic manufactures, though the [22] latter subject, which involves some intricate questions, ought not to be too confusedly blended with the former."

That is to say, he was one of those who believe that a doctrine can be true and its application unwise, and he thought that the coercion to be exercised on somebody else by doing one's self an injury was sufficient cause for submitting to suffering. He also tried very hard, on this and subsequent occasions, but fortunately in vain, to introduce discriminating duties as between the nations with which we had treaties and those with which we had none.

Perhaps the most remarkable utterance which has ever been made in the discussion of this tariff question was made by Fisher Ames in this debate of 1789. He said : " From the different situation of the manufacturers in Europe and America, encouragement is necessary. In Europe the artisan is driven to labor for his bread. Stern necessity, with her iron rod, compels his exertion. In America, invitation and encouragement are needed. Without them the infant manufacture droops, and those who might be employed in it seek with success a competency from our cheap and fertile soil." For a man to adduce the facts which are the grandest argument on one side of the question as an argument on the other is not common, and that a man like Fisher Ames could do it is a proof of the depth to which long rooted notions can affect a man's mind. The argument amounts to saying that it is so easy for laborers to get a living in America, that we must make it hard to get a living here in order that work may be done. It states the protectionist position in America, however, with great exactness. The cheap and fertile soil, by nature, holds out to men of the artisan class a competency in return for moderate and easy labor. In order that they might be forced to work at manufactures, which were, in the nature of things, less remunerative in a new country with boundless fertile soil, it was necessary to curtail by artificial and legal arrangements the profits of agriculture. This is just what the tariff has done from 1789 until this day. We are more familiar with the argument under the form of the comparative rates of wages here and abroad, but it comes back to just what Ames so simply stated. The competition which the protectionist employer has had to contend against here has never been the cheapness of foreign labor ; it has been the greater return which his men could get by putting the same labor on the soil. That is the only meaning of the high wages in this country. What makes wages high ? Where do they come from ? Or why is it that artisans are told that protection makes wages high ? How are these things reconcilable ? Or how is it that the foreign labor with which we are told that we cannot compete is especially that of England, where wages are higher than anywhere else in Europe ? Or why is it that high-priced labor can [23] compete here in agriculture and stand three or four thousand miles of transportation ? Wages are high here because men of the wages class can get all the fertile land they can till by going to it; because the capital required is yery small, and because the returns are almost pure reward of labor. Hence they will not go into the wages class unless the inducement is equal. It is the great form in which the new country holds out grand opportunities to the man who has nothing but his manual labor to depend upon, and the protective system does, and always has taken away from the farmer, laborer and artisan, the advantages which nature offered him in the new country.

To return to the tariff debate of 1789. The character of all tariff legislation in this country, as a grand grab struggle between interests and sections, was illustrated then.

The South, except Georgia, wanted a high tariff duty on rum, for revenue ; the Middle States, in the interest of temperance, the Eastern States, for protection to their rum distilleries. Georgia opposed this tax because she used a great deal of rum, and bought it in the West Indies with her lumber. The Southern and Middle States wanted a tax also on molasses, but this the Eastern States vigorously opposed. Molasses was the raw material of rum. It was bought with salt fish, lumber and staves sent to the West Indies. Rum was itself an export to Africa. Both the Eastern States, in this case, and Georgia, in the preceding, felt and urged the truth which the South urged in 1833, but which the manufacturers scouted, that the tariff on imports would diminish the trade and lessen the exports ; that is, cripple the " home industry." Our present tariff is unquestionably acting in the same way on all the great staple agricultural industries of the country which export their product.

The South opposed the tax on iron and steel, as all agricultural interests must. The Pennsylvanians replied that the manufacture was already established in their State, and that a slight duty would, " in a little while," lead to a great production.

The South wanted a protective tax on hemp, claiming that rice and indigo were unprofitable. Pennsylvania opposed any tax on hemp as a raw material of cordage, but wanted a tax on that. New England opposed the tax on cordage as a raw material of ships, but wanted protection on the latter. In the midst of this wrangling effort to invent some way by law to enable people to get rich in the country, it is interesting to notice that cotton was only incidentally alluded to. A tax of three cents a pound was put upon it, on the chances that it might come to something. This well illustrates the amount of foresight that statesmen can ever exercise in these matters. They passed over an article, destined by natural circumstances to become one of the great staples of the country, while they were looking for something to encourage, and when they found such [24] an article, whose value lay iu nature and fact, it was totally beyond their puny systems of artificial aid.

The South opposed any duty on spikes or nails. Goodhue replied for New England, that they were already exported, and that a tax would soon produce enough for all North America. It was a " domestic manufacture" in chimney corners. " Domestic manufactures " was a term then used for household manufactures, which were regarded with great favor as a desirable thing.

For twenty-five years after this time protectionist journals gathered instances of farmers whose wives or daughters spun and wove, and whose sons spent the evening in making nails at the chimney corner, and such journals paraded these cases as glorious instances of industry. This went on long after machinery had so cheapened these manufactures that an hour's farm work would pay for more goods of this kind than people could make by hand in a day, but the old people who clung to the method were pointed to as models, and the young people who preferred printed calicoes to homespnn and leisure to nail-making, were scolded for their extravagance. This opinion had no necessary connection with protection, but it sprang from the general erroneous point of view that we want work for the sake of work, and not for the sake of results ; that industry is a good thing, not because it produces more goods, but because it is work ; that the ideal of life is not abundance with leisure, but scarcity with toil. Hence it seems wise to refuse the benefits of machinery owned by foreigners in the first place, and before they know it, those who advocate protection to bring factories into being are applauding those who refuse to profit by the machinery when established.

New England and Virginia, which latter then expected to become a ship-building State, favored navigation acts as protection to shipping. The other States, as freight-payers and not ship owners, objected. A discriminating tonnage duty was laid, and ten per cent, was reduced from duties on goods imported in American ships. A special discriminating duty was laid on tea, because the tea trade could only be carried on by "a drain of specie." The wars in Europe and the increased trade of neutrals during the next twenty-five years led to an immense increase of American shipping independent of protection, but it became an important precedent, as I shall show, in the tariff debate of 1816.

The tariff of 1789 avowedly adopted the principle of protection. The preamble read as follows : " Whereas, it is necessary for the support of the Government, for the discharge of the debts of the United States, and the encouragement and protection of manufactures, that duties be laid, &c." It was declared to be only temporary in order to give infant industries a start, and was limited to 1796. The duties levied under it were equivalent to an ad valorem rate of 8 1/2 per cent. During the debate some [35] fears were expressed that the duties might be so high as to encourage smuggling. To this Mr. Madison replied that he " would not believe that the virtue of our citizens was so weak as not to resist that temptation to smuggling which a seeming interest might create. Their conduct under the British Government was no proof of a disposition to evade a just tax. At that time they conceived themselves oppressed by a nation in whose councils they had no share, and on that principle resistance was justified to their consciences. The case was now altered ; all had a voice in every regulation, and he did not despair of a great revolution in sentiment when it came to be understood that the man who wounds the honor of his country by a baseness in defrauding the revenue, at the same time exposes his neighbors to further impositions."

This tariff, then, was the thin edge of the wedge. The duties were raised the next year so as to equal an 11 per cent, ad valorem rate; and in 1792 they were raised to equal 13 1/2 per cent. Between the tariff of 1789 and that of 1816, a period of twenty-six years, seventeen acts were passed affecting duties, generally and steadily raising them.

The most important incident in this early tariff history was Hamilton's report on the manufactures, December 5, 1791. It came from a man who held and deserved high authority as a statesman, and it dealt with the subject in a comprehensive manner, li has been the arsenal from which our popular school of protectionists have borrowed ever since. Its political economy, however, is very erroneous, and defective in many fundamental respects. It is erroneous as to wages, and it confuses credit, capital and money. It is marked throughout by the errors of the old mercantile system, hinging all its views of foreign trade on the import or export of specie to be occasioned. Thus Hamilton says: "The West India Islands, the soils of which are the most fertile, and the nation which in the greatest degree supplies the rest of the world with the precious metals, exchange to a loss with almost every other country."

He admits the force of the broad free trade arguments, but thinks that while other nations follow the restrictive system, the United States must do so. He speaks of the hindrances met with in attempting to export American products, which would seem to point to a general conviction of the mischief of the entire restrictive system, and not to the conclusion that the United States ought to adopt the same policy. Though led to advocate protection on this special plea, he goes on to try to give it a theoretical justification. We shall have occasion to notice this again; but I beg you here to observe the difference. If the argument was made, as it often was for our first half century, that free trade was good, but that we must restrict because others did, it would follow that we ought to abandon restriction as fast and as far as others did. If the argument was based on principle and theory, it would be good any time, [26] for all nations, and forever. The argument of expediency was used, howeyer as in this report of Hamilton, to break the force of the common sense free trade view, and the theoretical argument was smuggled in behind it. He distinguishes seven particulars in which he thinks protection is theoretically advantageous. Of these, three, "the division of labor," "affording greater scope for the diversity of talents," and "affording a more ample and various field for enterprise," are only subdivisions of the great doctrine of the " diversification of industry," and may be noticed under that head. The issue here between the free trader and the protectionist depends on radically different views of human society. The question is whether industry diversifies itself as chances arise under the operation of natural forces, so that man can neither hasten the process nor retard it without doing injury ; or whether the legislature must be always on the watch to discharge a heavy responsibility resting upon it, viz., to tell society when and how to adjust itself into groups for industrial purposes. The industrial history of the American colonies offers the best proof in the world of the truth of the former view. There we see communities growing froin the simplest germ, isolated to a certain extent. We see that the development of society is as regular and as natural as that of a plant, and there is no more need of human interference than there is to make a bud burst into a blossom at the proper moment. It is a development, moreover, which cannot be hastened without injury. A new country cannot have the higher social developments until its population begins to grow dense. It is so with us yet. We have hot the literature or the science or the fine arts of the old countries, but we have not their poverty and misery. We must take our advantages and disadvantages together.

Now the diversification of industry comes, so far as it is desirable or advantageous, of itself. We must wait for it till it comes, and we must take it when it comes. The South will find its interest in cotton culture as a great prevailing industry for a long time to come. The same is true of the wheat of the West. No preaching can induce men to abandon the industry which is the most lucrative, and no law can make them do it without injuring their interest. As for the scope for varied talents, persons go to the places which offer an arena for their talents. They do not sit still and say : " Let us make an arena here." The tendency of man, as transportation is made easier and emigration freer, is to stop trying to coerce nature, and to put himself where nature spontaneously aids him. As for the division of labor, it is just as great and just as advantageous, now that transportation is easy, if the laborers are locally distributed as if they are industrially distributed. Look at the distribution in our own country. The South raises raw materials, the West raises [27] food, and the East manufactures. As for the varied field of enterprise, the world opens that, and our enterprises seek the place of advantage.

Hamilton next says that protection extends the use of machinery. He means that if there are manufactures, there is more use for machinery than there is in agriculture. On this view you do the business to use the machinery, you do not use machinery to do the business.

Next he argues that protection furnishes additional employment to classes not formerly engaged in the business. This is the argument that protection makes work. It is very true that protection makes work, but that it makes more work without making more product. It increases the human exertion necessary to gain the same amount of good.

He had in view domestic work auxiliary to adjacent manufactories. He thinks that the factories offer employment to the wives and children of farmers, in work which they can do at home. He refers to the children employed in factories in England, and he thinks that the farmer's income might be enlarged by this aid. Let us realize the facts. An American farmer could, by virtue of the advantages of the new country, if untrammeled by interference, support himself and a family by his own labor. Farm work furnishes opportunity for the participation of all the family to a certain degree. Beyond that the farmer could give his wife leisure for the culture and accomplishments of life. He could also support his children up to maturity, giving them a long and complete education. Now adopt the protective system and put up a fostered industry by the side of his farm. I think it very likely that you would soon find his wife spending her time over work from the factory, and his children curtailed of their time of education and sent to work in it. It would be found necessary to take some such step to keep up the family income to the old figure. Work would be made for the wife and children, and the amount of that work which they would be obliged to do would be no unfair measure of the harm the restrictive system had inflicted on the farmer. The protective system simply lowers the social attainments of farmers and farmers' wives, and lessens the degree of education to which farmers' children can aspire.

The next object which Hamilton thought that a protective system could attain was the promotion of immigration. The best examination of this claim is to look at the fact as to what immigration has taken place. Of course protection cannot be credited with any other immigration than that which has taken place amongst workmen in the protected industries. The total immigration for fifty-one years, from 1820 to 1870, was 7,800,000. Of these 4,800,000, or 61 per cent., had no occupation or stated none. They were mostly women and children and laborers, supplying manual labor, which the new country demanded in large quantities. The next largest number was of laborers so reported, 1,300,000. [28] The next number was of farmers, 900,000, bearing witness to the attractions of the natural advantages of the country simply. The next number was of mechanics, not specified, 500,000. Of the others, the only ones possibly included in protected industries were, miners, 92,181 ; weavers and spinners, 14,790 (of whom nearly half came between 1830 and 1840, when, as is well known, large numbers of persons in these trades came from England on account of the introduction of machinery, and sought other employment here) ; manufacturers, 4,520. Now, if we look at the half million mechanics, we find that very few of them belong to industries which are protected. For the sake of a closer examination, take a year of high protection and very large immigration, 1870. The total immigration was 387,303. Of these, those classified as " skilled workmen," numbered 31,964. Of these, 8,061, were " mechanics not stated," leaving say 24,000. The largest numbers amongst these were, blacksmiths, 2,378; carpenters, 4,421 ; masons, 2,190; shoemakers, 1,557; tailors, 1,660 (none of whom certainly profited by protection) ; miners, 4,763; weavers, 1,178 (who came into more or less protection). The others who belonged to protected industries were, brewers, 362 ; cutlers, 5 ; distillers, 2; file-makers, 2 ; gunsmiths, 2 ; hatters, 58 ; hoemaker, 1 ; instrument maker, 1 ; iron workers, 8 ; jewelers, 409 ; nailmakers, 19 ; potters, 8; printers, 180; puddlers, 2; rope-makers, 3; saddlers, 167; shipwrights, 9; soap-makers, 2 ; spinners, 7; tanners, 102; woolsorter, 1 ; operatives, 23 ; shepherds, 23. Out of a total of 387,203 immigrants, the number who came to make articles which either could be or were protected was 6,960, or less than two per cent. It appears that protection has not drawn immigrants, as a matter of fact.

Hamilton's next point is that protection secures a more certain and steady market for the products of the soil. This is the notion of the " home market." Hamilton urged it on the ground that foreign restrictions hindered the exportation of an agricultural surplus. He thought it necessary for government to take the matter in hand and provide or secure a home market. Obviously it is an advantage to any new country to increase its inhabitants. If such increase took place anywhere there must follow an increased production.

Now, for the sake of brevity, I will state in general terms what happens, although every proposition might be illustrated abundantly from our own colonial liistory. The industries which begin first in a new country are those which the economists call "extractive industries." They require little capital, and admit of little division of labor. They are agriculture, lumbering, hunting or trapping, fishing and mining. Some mechanics are needed in the building trades. In regard to these persons, one principle I have already stated was illustrated in the early history of Massachusetts, They would not work except at wages which [29] would equal the remuneration which they could get in the industries mentioned. The way the Puritans tried to deal witli the problem was to fix wages by law, but the men either took to agriculture, or went on to other settlements where there was no such law. At first, every farmer is his own wheelwright and blacksmith and carpenter. As the population increases there is a surplus of agricultural products. Some who have greater skill or taste for the mechanical arts work in those occupations for others until the division of labor becomes established gradually and naturally. Some products are exported, being raw materials, of great demand. Manufactured goods, cloth, tools, books, paper, and all the comforts and conveniences of the old life of the colonists are imported in exchange. Some become merchants to carry on this exchange, and build a town at the seaport. At first, clergymen and schoolmasters may be the only professional men, and they act as lawyers and doctors. All participate in legislation ; merchants do all the banking. As the population increases and the country fills up the extractive industries become less lucrative. The sources for some of them become exhausted, the supplies of others become superabundant. Farming itself undergoes subdivisions and refinements. Orchards are planted for fruit, and gardens for vegetables. Stock raising becomes profitable, and dairy farming is extended. Simultaneously with this, without any dividing line, or any exertion whatever, the simple mechanic arts which existed at the outset grow into independent manufactures, according to the circumstances of the case. It depends on the distance of the colony, the facility of transportation, the market for its surplus abroad, the amount of land open, how soon or how rapidly this social organization will be developed. If foreign nations all had severe restrictions upon the entrance of the goods this country wanted to export, they would put just so much premium on the early development of manufactures there. The whole tendency of a surplus supply of food would be to force some of the producers of it to seek some other employment, in which they would produce other things to exchange with their neighbors for food. Every refusal of a foreign country to take the only things the new country could offer in exchange for its goods would throw the inhabitants back on their neighbors to supply the want by such exchange. Every such act would, moreover, diminish the value of the surplus, that is, would increase the amount which the farmer could afford to give his neighbor for making his cloth and iron for him. The "home market" would thus "provide" itself, if it was wanted, and the want itself would be the result of foreign errors, injuring in just so far the community in question. If one of their own statesmen took it into his head that it was his business to provide a home market, he could only do it by adopting the restrictive [30] system, and still further depressing the profits of agriculture, and thus accellerating the mischievous process already at work.

The repeal of the corn laws in England was accordingly a great blowto American manufactures, because it allowed American agriculture to come to a part of its natural rights, and we have been trying, ever since 1861, to neutralize this by heavier pressure of taxation. That same repeal, however, took away all Hamilton's argument, and the general argument has since been altered. We have been told lately that protection is to bring the manufacturer and the farmer near together ; to give the farmer a market near his own door, and in various ways the export of agricultural produce has been represented as an evil. But when we talk of " bringing " the manufacturer and farmer together, it may fairly be asked : Who is to " bring ?" This is language for an Assyrian king, deporting inhabitants from one part of a country to another. If the manufacturer finds the conditions of successful industry lead him to a certain spot, well and good. That spot will enjoy the benefit of its peculiar advantages. But if it has no such advantages, and we plant a factory there, shall we thereby give them to it ? Shall we ever get back the expended force ? Shall we not rather suffer loss so long as the artificial creation stands where it ought not to be ? Will not that loss come out of the legitimate, sound and healthy industries ? The error is in thinking that we ever can get out of an artificial creation any more than we put into it; it is only when we get nature to work with us and for ue, that we can get anything gratuitously. The American farmer has long ago found that there cannot be two prices in the same market ; that he does not get any different price for his wheat if consumed next door from that which he gets if it is consumed in Manchester. He rarely knovws where it is consumed and never cares.

The whole idea of advantage in bringing farmer and manufacturer together is a delusion. It is much more important to bring the various manufacturers together, because they form groups which assist and sustain each other, and it is important to bring them to the country or place where the conditions of success exist. This place will not be where the profits of capital and the wages of labor in either agriculture or commerce are exceptionally high. Hence to carry a factory by force into an agricultural district will be to ruin the factory and not help the farmer; Where the profits of one industry far exceed those of all others, we have that one only. Where the profits of several are equal, we have them all. The advantages and disadvantages of either state of things are about equal.

Hamilton next proceeds to consider the objection to manufactures, that they are impossible here on account of the dearness of labor and the scarcity of capital. He reduces both these objections to a minimum, but shows thereby that protection was not necessary, and proves finally that [31] . manufactures were possible by enumerating many which, were already thriving. In fact the country became very prosperous in 1789 and 1790 so soon as civil order was secured.

Further on again he urges an argument which is especially interesting because at a later time it became very popular: that protection lowers prices through the home competition. One is impelled to ask why, then, those interested desire it. Who would urge Government interference to lower the price of his goods ? If the Grovernment should so act, who would not cry out to be " let alone " ? Nevertheless, the assertion is not without truth, only it is not all the truth. The first effect of a tariff is to draw many persons into the protected industries who believe that the tariff gives them full margin, and that special knowledge, or business care, or sagacity in choice of situation are not necessary. Factories are built extravagantly, or in bad situations. There follows large production, a glut, a fall in prices, perhaps even below foreign prices. Then come failures of those who have been most reckless. Then the remaining strong firms continue and adopt rules to " limit production," the necessary manipulation of any monopoly. Prices rise again on a limited supply, and the operation is repeated unless the combination is really strong enough to keep others out. These fluctuations are the real character of a tariff system, not either high prices or low prices, and they are one great reason why protection does not protect.

Hamilton next considers the means of protection, of which he enumerates eleven. These are import duties, prohibition on imports, prohibitions on exports, bounties, premiums, drawbacks, patents, inspection laws, facilitation of remittances, and improvements in transportation.