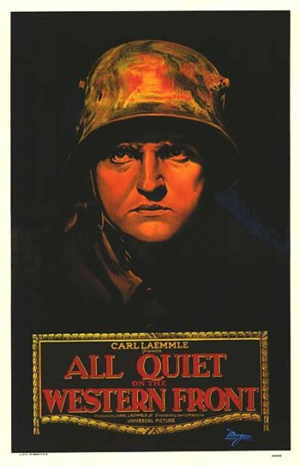

[Michael Curtiz, “The Adventures of Robin Hood” (1938) – a man who “speaks treason fluently” to tyrants]

[Warren Beatty, “Reds” (1981) – a brilliant political film but about the wrong side]

See also “The Politics and History of/in Film”.

I have used films in my teaching and lecturing ever since I began teaching at the University of Adelaide in 1986. They were a regular feature in my first year introductory courses on Modern European history, my upper level courses on “German Europe” and “The Holocaust,” and most extensively in my course “Responses to War: An Intellectual and Cultural History” in which, over a period of a decade, I showed about 100 different films. [See “Some Thoughts on how People have ‘Responded to War’”]

The week long Summer Seminars organized by the Institute for Humane Studies during the 1990s on “Liberty in Film and Fiction” gave me an opportunity to show and discuss films with a group of students who were sympathetic to CL/libertarian ideas and who were in creative writing and film studies programs. These films included:

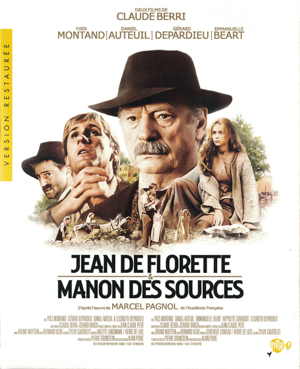

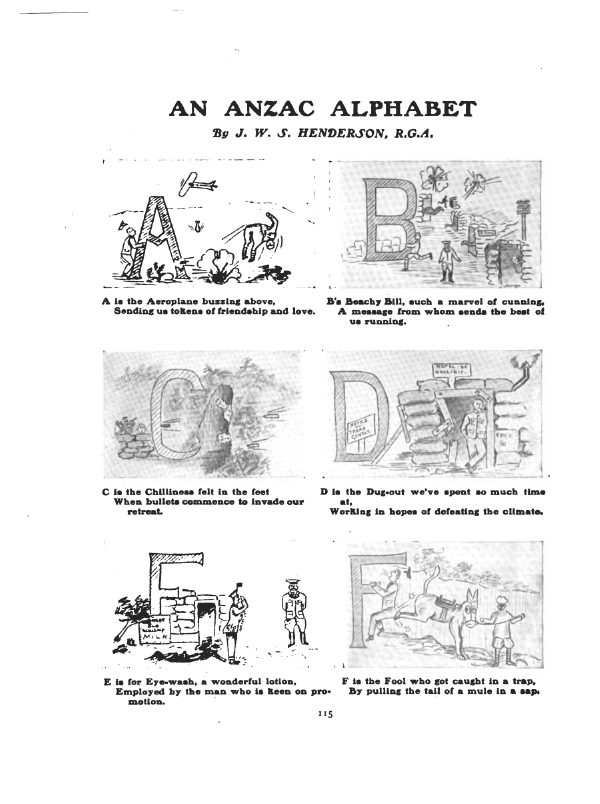

- Lewis Milestone, “All Quiet on the Western Front” (1930)

- Michael Curtiz, “The Adventures of Robin Hood” (1938)

- Robert Wise, “Executive Suite” (1954)

- Stanley Kubrick, “Dr. Strangelove” (1964)

- Andrew McLaglan, “Shenandoah“ (1965)

- George Lucas, “Star Wars IV: A New Hope” (1977)

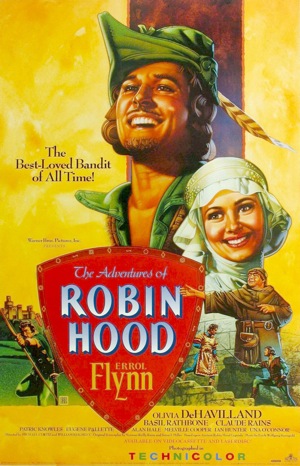

- Claude Berri, “ Jean de Florette“ (1987) and “Manon des sources” (1987)

- Oliver Stone, “Wall Street” (1987)

- Kenneth Branagh, “Henry V” (1989)

- Volker Schloendorff, “The Handmaid’s Tale” (1990)

- Norman Jewison, “Other People’s Money” (1991)

[Claude Berri, “Jean de Florette” (1987) – on property rights in water and what happens when they are violated]

Since war films were a major interest of mine, during 1995 I held a two week long “film festival” to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the end of the Second World War, during which I showed two films a day for two weeks. See the full list.

The two Honours level subjects I taught on ”Reel History: History IN Film and Film AS History” (course guide) and “Film and the History of Occupation, Collaboration, and Resistance in WW2” (course guide) provided an opportunity to explore in greater depth some of the key questions which an historian must ask about film, such as

- the representation and interpretation of history which takes place WITHIN films, in other words, to examine films as works of historical interpretation by the filmmaker

- to study films as important historical documents in their own right, i.e. to use films as just one of many primary sources one might use in order to better understand the past

- to compare and contrast the kind of history presented to the public by the film industry in Hollywood, i.e. “Hollywood History”, with other, sometimes more thoughtful historical films made by European and independent filmmakers

- to compare and contrast all forms of “filmed history” with the history found in traditional, printed texts

Since I was teaching “history” courses a major question we had to ask and try to answer (if we could) was how historically accurate was the film, and if it was not accurate, to ask the follow up question, why did the filmmaker alter the past or stress certain aspects and ignore or distort others?

A question we kept coming back to was one posed by Robert Rosenstone, who asked:

No matter how serious or honest the filmmakers, and no matter how deeply committed they are to rendering the subject faithfully, the history that finally appears on the screen can never fully satisfy the historian as historian (although it may satisfy the historian as filmgoer). Inevitably, something happens on the way from the page to the screen that changes the meaning of the past as it is understood by those of us who work in words.

[Robert A. Rosenstone, “History in Images/History in Words: Reflections on the Possibility of Really Putting History into Film,” American Historical Review, December 1988, vol. 93, no. 5, pp. 1173-85. ]

It should be noted that Rosenstone, as an historian, wrote a biography of the American socialist journalist John Reed, Romantic Revolutionary: A Biography of John Reed (1975) and then advised Warren Beatty in the making of his Academy award-winning film Reds (1981). The film is a brilliant depiction of an immensely important historical event but is is far too sympathetic to the socialist cause, even uncritical. This inspired me to write my own screenplay on a classical liberal on whom I had written a great deal who had also been involved in a revolution – Frédéric Bastiat in the 1848 Revolution in Paris in February 1848. The results, entitled “Broken Windows” screenplay HTML, along with an “illustrated essay” to help the director “visualize the past” can be found here. I found some initial interest by a small-time producer in taking it further but that interest soon evaporated when the complexity and the cost of filming an “historical film” became evident. In the meantime a dreadful “bro” movie about Marx and Engels in Paris at the same time Bastiat was living and working there got made with funding by the EU. [Raoul Peck, “The Young Karl Marx” (2018) and the review in the New York Times by A.O. Scott (22 Feb. 2018) here]

[Raoul Peck, “The Young Karl Marx” (2018) – yet another account of the life of an obnoxious man and his obnoxious ideas]

Other questions I explored in these classes, with particular reference to war films, were the following. To use films:

(1.) to assist in the visualisation of historical events or historical conditions, thus the film acts as a “window on the past” and is an attempt to “restage the past” (Sorlin) or an attempt to create “historical authenticity” (Zemon Davis) on the screen. Examples include:

- Carl Theodor Dreyer, The Passion of Joan of Arc (La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc) (1928)

- Lewis Milestone, All Quiet on the Western Front (1930)

- Cy Endfield, Zulu (1964)

- Stanley Kubrick’s Spartacus (1960) and Dr Strangelove (1964)

- Peter Watkins, The Battle of Culloden (1969)

- Oliver Stone, Platoon (1986)

- Maxwell, Gettysburg (1994)

- and one film which is not: John Wayne’s Green Berets (1968).

[The sensational original release movie poster of a slave revolt in ancient Rome which does not show any inkling of Kubrick’s deeper ideas about the subject.]

(2.) to study the history of prevailing attitudes or mentalités, since sometimes the film tells us more about the time of its making than the events it sets out to depict, that the film reflects the “climate of opinion” of the society in which it was made, in other words it acts as a “mirror of contemporary society”.

- the left-wing and humanitarian pacifism of Remarque/Milestone’s All Quiet (1930) and Pabst’s Westfront 1918 (1930) in the late Weimar Republic;

- the officially sanctioned or supported war propaganda of Olivier’s Henry V (1944) and Frank Capra’s series on Why We Fight (1942); and on the German/Nazi side, Veit Harlan, Kolberg (1945)

- he paranoia and fear of communist infiltration and invasion at the height of the Cold War in Siegel’s Invasion of the Bodysnatchers (1956);

- and the anti-authoritarianism, even anarchism, of the swinging sixties depicted in Altman’s MASH** (1970) and Nichols’ Catch-22 (1970).

(3.) to study the ideas of individual filmmakers (especially those who were war veterans); in this case, the film is a “personal memoir” by someone who had first-hand experience of the events depicted on the screen.

- films made by directors who were engaged as official filmmakers during war who went on to make films after the war, such as John Ford’s They Were Expendable (1945) and William Wyler’s The Best Years of Our Lives (1946).

- Three examples of filmmakers who personally experienced combat include Jean Renoir’s La Grande Ilusion (1936), Masaki Kobayashi’s The Human Condition (1959-61), and Oliver Stone’s (again) Platoon (1986) and Born on the 4th of July (1989).

- or indirectly, when a director makes a film based upon a novel or memoir by someone else who was a participant, such as Lewis Milestone (Erick Maria Remarque), All Quiet on the Western Front (1930)

(4.) to reflect on the nature of war, history and the human condition in a general way; in this case, film can function as a philosophical or historical “essay” which attempts to interpret or make sense of the past in some way.

- films based upon Shakespeare – Laurence Olivier’s and Kenneth Branagh’s versions of Shakespeare’s Henry V (1944/1989), Akira Kurosawa’s Throne of Blood (1957) and Ran (1985);

- Akira Kurosawa, The Seven Samurai (Shichinin no Samurai) (1954)

- Sergei Bondarchuck’s version of Tolstoy’s War and Peace (1968);

- Jean Renoir, La Grande Illusion (1936); Kon Ichikawa, The Burmese Harp (Harp of Burma – Biruma No Tategoto) (1956) and Fires on the Plain (Nobi) (1962)

- Stanley Kubrick’s oeuvre of war films: Paths of Glory (1957), Full Metal Jacket (1987), Dr. Strangelove, or How I learned to stop worrying and love the Bomb (1964)

- Masaki Kobayashi’s The Human Condition (1958-61).

[Lewis Milestone, “All Quiet on the Western Front” (1930) – the classic anti-war movie to which we all keep coming back.]

An important question which was often raised in my courses was one articulated by the Romanian film historian Manuela Gheorghiu-Cernat who expressed it this way: is the showing and studying of war films (especially violent ones) “a pedagogy of peace or a school of violence?” [Arms and the Film, pp. 303-23]. Perhaps Fritz Lang was correct when he stated in 1958 interview: “Could anything new be possibly said on war?… No. But, it is essential for us to repeat over and over again, the things previously uttered.” (Quoted in Manuela Gheorghiu-Cernat, Arms and the Film, p. 304.)

Lang’s unstated assumption is that in the 20th century film would become the medium through which this restatement of the horrors and evil of war can and should be made. We need to ask ourselves whether film, rather than the written word (or perhaps art), is the proper medium for this dialogue. Or perhaps Georges Duhamel is closer to the mark with his prediction: “I shall no longer be able to think what I want. My thoughts will be replaced by mobile images.” (Quoted in Manuela Gheorghiu-Cernat, Arms and the Film, p. 305.) The American soldiers in Vietnam who had watched John Wayne westerns and war movies when they were growing up had such mobile images in their minds – images of heroic actions, self-sacrifice for the state, and glorious death on the battlefield. The great power cinema has is the capacity to offer such “mobile images”, with their associated political and moral meanings, for the purposes of distraction, excitement, amusement, and the political control of audiences. Thus educators have a special responsibility to use this medium carefully.

What I try to do in my use of film in the teaching of history is to make explicit what is implicit in the mobile images on the screen, to place in historical context what might appear at first sight to be timeless and “normal” to the viewer, to discuss the moral beliefs and the political orientation of filmmakers and the impact these ideas have on their filmmaking, and to examine the reception of the films by the audiences of their day.

[Source: Manuela Gheorghiu-Cernat, Arms and the Film: War and Peace in European films. Translated into English by Florin Ionescu and Ecaterina Grundbock (Bucharest : Meridiane, 1983).]

Some additional thoughts on the connections between film and history can be found in the following essays and guides:

“A Guide to the Study of War, History, and Film”

“Further Thoughts on War Films and the Study of History”

“Bastiat goes to the Movies, or “Filming Freddie”: How to Popularise Economic Ideas in Film” (2017)

“Some Thoughts on an ‘Austrian Theory of Film’: Ideas and Human Action in a Film about Frédéric Bastiat” (Sept. 2019)