Date: 6 July, 2023

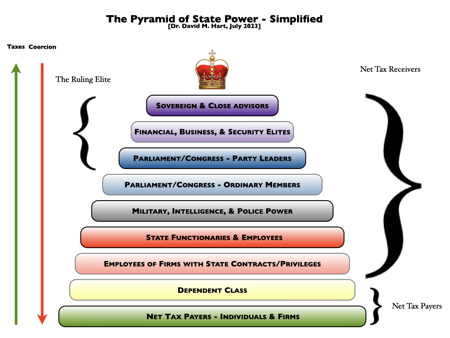

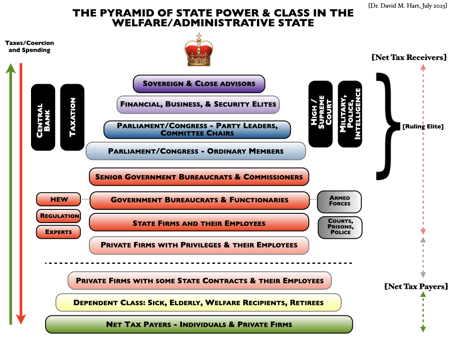

A Summary View

- The Sovereign Power

- The Ruling Elite

- The Political Class

- The Bureaucratic or Functionary Class

- Force Wielding Institutions

- The Welfare State

- The Regulatory State

- The Plutocratic or “Crony Capitalist” Class

- State Privileged or Dependent Firms & their Employees

- State Owned Firms

- State Privileged Firms

- State Dependent Firms

- The Dependent Class

- Net Tax Payers (NTP)

A More Detailed Discussion

The Sovereign Power

The Sovereign Power historically used to be a single person, such as a monarch, emperor, or dictator. All legitimate power came from them and they considered all the property and the inhabitants in the country to be “theirs” to do with what they willed. In the modern state “sovereignty” is more nebulous in that it can reside in a semi-fictitious entity known as “The Crown”, or “the people” as represented in an elected body like Parliament or Congress.

The Ruling Elite

The “ruling elite” is the ultimate decision maker of policy, drawn from the ruling family, tribe, army, nobility, church, political party, senior leaders of congress or parliament, and legal, banking, industrial, security elites, depending upon the historical circumstances. This relatively small group control the “Command Centres” of the state (the Presidency, Congress, the military, the intelligence services, the Federal Reserve (or Reserve Bank), the Supreme Court, the Taxation Office, etc) and run the show. This group is a very small minority of those who benefit from access to state power. Some theorists also call this group the “Deep State” which was first developed to explain the power structure within the modern Turkish state. They remain in power for long periods of time and are shielded from the upheavals and uncertainties of the electoral cycle.

The Political Class

The “Political Class” more generally speaking is made up of elected politicians who sit in Congress / Parliament. The real power wielders in Parliament are the senior party leaders, the chairmen of the more important congressional committees which control spending and formulate legislation, and senior bureaucrats who run the main government bureaucracies (Health, Education, Welfare). Most MPs are concerned with getting re-elected and serving the vested interests in their state or district. We can add to this group some of the more wealthy and influential “private individuals” from finance, banking, think tanks, industry (especially defence and communications), and media moguls who advise the government on policy matters. Much of their influence comes from their ability to raise funds for politicians to get elected.

The Bureaucratic or Functionary Class

The Bureaucratic or Functionary Class carry out and implement the government policies which they are given. This large group can be divided into those who run and work for the “Force Wielding Institutions” which have a monopoly of the use of force or violence, such as the Courts, police, prisons, and the armed forces; the main government bureaucracies of the “Welfare State” such as Health, Education, and Welfare; and the other bureaucracies and Commissions which administer and regulate the economy and citizen’s lives (i.e. the Regulatory State)

Many bureaucrats and sate functionaries are low ranking office workers, public school teachers, and post office workers, etc, and are thus by no means members of the “ruling class” but they are in a technical sense “net tax-receivers” and have a long-term interest in voting to maintain government (or rather tax-payer) funding for the institutions which employ them and pay their retirement benefits.

The Plutocratic or “Crony Capitalist” Class

The Plutocratic or Crony Capitalist Class are very wealthy and influential business owners who actively seek to get or retain special privileges from the state in the form of subsidies, contracts, monopolies, favourable legislation, favourable monetary policy, etc. This class is quite complex to understand using the crude NTP/NTR distinction since they may still receive most of their income from the private sector (hence making them technically NTP). However they benefit enormously from their access to state by getting the entire economic system skewed in their favour.

State Privileged or Dependent Firms & their Employees

There are several types of firms in this category. There are the “State Owned Firms” which are entities owned and run by the state. These include (or used to include) transport (buses, railways, ports), public utilities (water, gas, electricity), and industries considered to be of “strategic” importance such as munitions and armaments work. Another category are “State Privileged Firms” which have been given “protection” or subsidies such as the car industry or the sugar industry. A third category are “State Dependent Firms” who earn some of their income by selling goods and services in the market but which also seek and get government contracts in order to make profits. They are a complex mixture of sometimes being a “tax receiver” as well as a “tax payer”. Whether they are “net” in one direction of the other has to be determined on a case by case study. The latter two categories are nominally private firms which receive the bulk (perhaps all) of their income from privileges granted to them by the state, such as tariff protection for the car industry, or who are largely dependent for their income on contracts made with the government (and paid by tax-payers) such as companies which specialize in building highways or military equipment.

The Dependent Class

The Dependent Class is comprised of people who receive benefits from the state such as health, retirement, or other welfare benefits. Some were NTP when they were working (probably in the private sector) but are now NTR in their retirement. Others have always been NTR. Some others are very poor and/or sick people who have been trapped in the cycle of poverty which has been created by the welfare state over the past 60 years. This latter group might also be categorised as “victims” rather than “beneficiaries” of the modern welfare state.

Net Tax Payers (NTP)

“Net Tax Payers” consists of individuals and firms who pay more in taxes than they receive in state benefits. Historically, there have also been groups who have been forced to labour for little or no remuneration (slaves, serfs, conscripts). This group is a complex one because it is not immediately apparent whether they are, on net, NTP or not. There may be some clear examples of “pure net tax-payers” still in existence, but in this thoroughly statised and regulated world most of us would fall into the category of the “grey zone” where we pay taxes but also “consume taxes” in the form of using streets and getting police protection from robbers. Then there are the people who change their class status over time, people who are net tax-payers in their prime working age and then become net tax-receivers in their retirement.

For further reading on CLCA

- see a page which lists the material on my website on CLCA: <davidmhart.com/liberty/index.html#clca>

- my chapter on “Class” in The Routledge Companion to Libertarianism. Edited by Matt Zwolinski and Benjamin Ferguson (Routledge, 2022) , pp. 291-307.

- a much longer version of which is here: “Libertarian Class Analysis: An Historical Survey” <davidmhart.com/liberty/ClassAnalysis/HistoricalSurvey/Sept2020draft.html>

- a paper I gave at the 2018 Libertarian Scholars Conference, The Kings College, NYC, 20 Oct. 2018: “Plunderers, Parasites, and Plutocrats: Some Reflections on the Rise and Fall and Rise and Fall of Classical Liberal Class Analysis” <davidmhart.com/liberty/Papers/Plunderers/DMH-PPP-Oct2018.html>

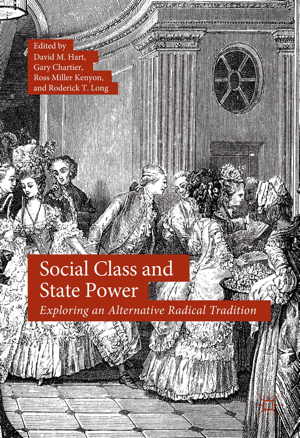

- the book I co-edited of a collection of texts in classical liberal and libertarian class analysis, Social Class and State Power: Exploring an Alternative Radical Tradition, ed. David M. Hart, Gary Chartier, Ross Miller Kenyon, and Roderick T. Long (Palgrave Macmillan, 2018).