Further Thoughts on War Films and the Study of History

|

|

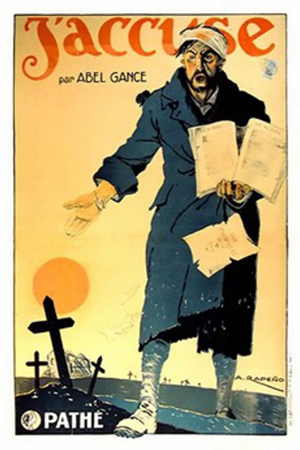

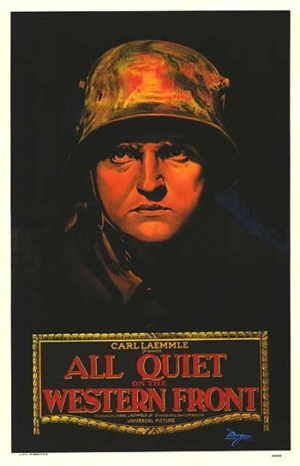

| Abel Gance, "J'Accuse" (I accuse you!) (1919) | Lewis Milestone, "All Quiet ion the Western Front" (1930) |

This essay is part of a collection of material on my course "Responses to War."

Introduction

Film has become one of the greatest and most influential art forms of the 20th century. We need to learn how to view films critically and historically not just to be entertained by them. We need to appreciate that films embody ideas and values about the world and that critical viewing of them can reveal what these ideas and values are.

War films can be used for a number of purposes in the study of history:

- to assist in the visualisation of historical events or historical conditions - the film acts as a "window on the past", it is an attempt to "restage the past" (Sorlin) or an attempt to create "historical authenticity" (Zemon Davis) on the screen.

- to study the history of prevailing attitudes or mentalités - sometimes the film tells us more about the time of its making than the events it sets out to depict, that the film reflects the "climate of opinion" of the society in which it was made, in other words it acts as a "mirror of contemporary society".

- to study the ideas of individual filmmakers (especially those who were war veterans) - in this case, the film is a "memoir" by someone who had first-hand experience of the events depicted on the screen.

- to reflect on the nature of war, history and the human condition in a general way - in this case, film can function as a philosophical or historical "essay" which attempts to interpret or make sense of the past in some way.

Film as a “Window on the Past”: "Restaging the Past"

See for examples of films which attempt to create, with varying degrees of success, accurate depictions of historical events or conditions :

- Carl Theodor Dreyer, The Passion of Joan of Arc (La Passion de Jeanne d'Arc) (1928)

- Lewis Milestone, All Quiet on the Western Front (1930)

- Cy Endfield, Zulu (1964)

- Stanley Kubrick’s Dr Strangelove (1964)

- Peter Watkins, The Battle of Culloden (1969)

- Oliver Stone, Platoon (1986)

- Maxwell, Gettysburg (1994)

- and one film which is not: John Wayne’s Green Berets (1968).

The visualisation of historical events or historical conditions is the most elementary function of film in the teaching of history. It is simply an attempt, in Pierre Sorlin’s words, to “restage the past” in a manner which captures the imagination of viewers. (Pierre Sorlin, The Film in History: Restaging the Past (Totowa, New Jersey: Barnes and Noble Books, 1980).) Where once words on a page were sufficient to create images in the reader’s mind, in the TV age images on a screen are needed to achieve the same result. To a literate reader, Voltaire's few sentences in Candide (1759) describing the innocent victims of war and the sanctimonious behaviour of the French and Prussian military leaders are sufficient to transmit his profound hatred of war which emerged during the Seven Years War. The power of Tolstoy's prose to describe the French summary executions of Russian civilians who opposed the occupation of Moscow by Napoleon's troops in 1812 is as impressive as one can find anywhere in literature. Likewise, the passages in Émile Zola's novel The Debacle (1892) describing the horrors of a makeshift field hospital and the human consequences of the new Prussian needle gun in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870 require no pictures to make their point. I think Zola does a much better job of showing the horror of production line amputations than Kevin Costner does in the opening of Dances with Wolves. However, when it comes to twentieth century wars our mental picture of them is just that - mind "pictures" which have their origins in film, photographs and TV. Twentieth century war is "visual" like no other period of warfare in human history. Thus, we must be able to "read" a film in a critical and historically informed manner if we are to deal adequately with the nature of war in our century.

Film as a “Mirror of Contemporary Society”: The History of Prevailing Attitudes

Examples include the following:

- the left-wing and humanitarian pacifism of Remarque/Milestone’s All Quiet (1930) and Pabst’s Westfront 1918 (1930) in the late Weimar Republic;

- the officially sanctioned or supported war propaganda of Olivier’s Henry V (1944) and Frank Capra’s series on Why We Fight (1942); and on the German/Nazi side, Veit Harlan, Kolberg (1945)

- the paranoia and fear of communist infiltration and invasion at the height of the Cold War in Siegel’s Invasion of the Bodysnatchers (1956);

- and the anti-authoritarianism, even anarchism, of the swinging sixties depicted in Altman’s M*A*S*H* (1970) and Nichols’ Catch-22 (1970).

The second use of films is to study the history of the prevailing attitudes or mentalités of the time in which the film was made. In some cases the film tells us more about the time of its making than the events it sets out to depict. The assumption behind this approach is that the ideas of the filmmakers which are transferred to the screen reflect in some way the “climate of opinion” of the broader society in which they work. Since films from their inception have been made to make profits at the box office, most popular films have been made to appeal to the tastes and interests of the audiences, thus reflecting commonly held views back to the audience for their enjoyment. Other films, not made for popular taste but to further a particular political cause, tell us about the ideas of important sub-groups or classes within society. Examples I would like to mention include the humanitarian pacifism of Remarque/Milestone’s All Quiet (1930) and the left-wing pacifism of Pabst’s Westfront 1918 (1930) in the late Weimar Republic; the officially sanctioned or supported war propaganda of Olivier’s Henry V (1944) and Frank Capra’s series on Why We Fight (1942); the paranoia and fear of communist infiltration and invasion at the height of the Cold War in Siegel’s Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956); and the anti-authoritarianism, even anarchism, of the swinging sixties depicted in Altman’s M*A*S*H* (1970) and Nichols’ Catch-22 (1970).

Film as a Personal “Memoir”: The Ideas of Veteran Filmmakers

Examples include

- films made by directors who were engaged as official filmmakers during war who went on to make films after teh war, such as John Ford’s They Were Expendable (1945) and William Wyler’s The Best Years of Our Lives (1946).

- Three examples of filmmakers who personally experienced combat include Jean Renoir’s La Grande Ilusion (1936), Masaki Kobayashi’s The Human Condition (1959-61), and Oliver Stone’s (again) Platoon (1986) and Born on the 4th of July (1989).

- or indirectly, when a director makes a film based upon a novel or memoir by someone else who was a participant, such as Lewis Milestone (Erick Maria Remarque), All Quiet on the Western Front (1930)

The third use to which I put film in my teaching is to study the ideas of individual filmmakers who were war veterans, of which there are a surprising number. But we should not be surprised given the research by Kevin Brownlow for the First World War and Paul Virilio for the twentieth century as a whole, on the striking connection between war service and filmmaking. (Kevin Brownlow, The War, the West and the Wilderness (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1979); Paul Virilio, War and Cinema: The Logistics of Perception, trans. Patrick Camiller (London: Verso, 1989).) As an historian of ideas I am concerned with the view of war presented to us by filmmakers who directly experienced war or combat in some form. In many cases filmmakers served in the armed forces in sections which enabled them to draw upon their skill as filmmakers - in the signal corps, intelligence, or propaganda or documentary services. Two examples of films made by directors who were engaged as official filmmakers during war include John Ford’s They Were Expendable (1945) and William Wyler’s The Best Years of Our Lives (1946). Less frequently though, we can find examples of filmmakers who served at the front and experienced combat directly as footsoldiers, rather than from the more privileged position of Army cameramen or official propagandists. I am especially interested in these soldier filmmakers as a rather different view of war comes from those future filmmakers who sighted along the barrel of a rifle instead of through an army signal corps camera. Three examples of filmmakers who personally experienced combat include

- 1. Jean Renoir’s La Grande Ilusion (1936)

- 2. Masaki Kobayashi’s The Human Condition (1959-61)

- 3. Oliver Stone’s (again) Platoon and Born on the 4th of July (1989).

Jean Renoir served as an observer and then as a pilot in the French Flying Corps in World War One and later drew upon his experiences to produce the classic pacifist film La Grande Ilusion (1936) with its moving plea for reconciliation and understanding between classes and nationalities.

Masaki Kobayashi was drafted into the Japanese army and served in Manchuria and the Ryukyu islands from 1942-44, experiences which he drew upon for his monumental and epic film The Human Condition (1959-61). Kobayashi’s hero Kaji struggles to maintain his humanity and dignity in the face of the atrocities of slave labour, conscription, basic training and combat. Only his love for his wife sustains him while in the Japanese army and ultimately only death frees him from his torment.

Oliver Stone is perhaps the best known “veteran” filmmaker of recent history. Stone dropped out of Yale University, taught English at a school in Saigon, served as a wiper in merchant marine, and then joined the US army to fight in Vietnam in 1967-68 (15 months altogether). Stone wrote the screenplay of Platoon during the bicentennial of the American Revolution 1976 but could not get any American film makers to make it. When it was made some ten years later the film had become what Stone described as “a possible antidote to the reborn militarism of Grenada, Libya, Nicaragua.” In his tetralogy of films about the 1960s (Platoon, Born on the 4th of July, The Doors, JFK) Stone has argued that idealistic youth like himself were somehow “betrayed” by the political establishment and their parents. The anger caused by this sense of betrayal is vividly transferred to the screen.

D. Film as a Philosophical or Historical “Essay”: Philosophical Reflection upon the Nature of War and the Human Condition

I include in this section the following films:

- films based upon Shakespeare - Laurence Olivier’s and Kenneth Branagh’s versions of Shakespeare’s Henry V (1944/1989), Akira Kurosawa’s Throne of Blood (1957) and Ran (1985);

- Akira Kurosawa, The Seven Samurai (Shichinin no Samurai) (1954)

- Sergei Bondarchuck’s version of Tolstoy’s War and Peace (1968);

- Jean Renoir, La Grande Illusion (1936);

- Kon Ichikawa, The Burmese Harp (Harp of Burma - Biruma No Tategoto) (1956) and Fires on the Plain (Nobi) (1962)

- Stanley Kubrick's oeuvre of war films: Paths of Glory (1957), Full Metal Jacket (1987), Dr. Strangelove, or How I learned to stop worrying and love the Bomb (1964)

- Masaki Kobayashi’s The Human Condition (1958-61).

The fourth use of films in the teaching of history is to reflect upon the nature of war and the human condition in a general, philosophical way. The concern here is less with the exactitude of the historical depiction of the events depicted (although this is always important), than with the view of the world offered by the director. The topic of war offers filmmakers enormous scope for an examination of the moral dilemmas posed by violent conflict, the ties that bind men who go to war, the nature of political authority, and the effect on men of violence both directly and indirectly. In other words, war can be viewed as a microcosm of the human condition in general and films about war can serve as philosophical texts which explore this domain. Whether or not the filmmaker has had any personal or direct experience of war or combat is less important. What is important is that they have something interesting to say. I include is this section the following films: Laurence Olivier’s and Kenneth Branagh’s versions of Shakespeare’s Henry V (1944/1989); Sergei Bondarchuck’s version of Tolstoy’s War and Peace (1968); Jean Renoir’s La Grande Illusion (1936); Kon Ichikawa’s Fires on the Plain (1962) and Harp of Burma (1967); Stanley Kubrick’s oeuvre of war films; Masaki Kobayashi’s The Human Condition (1958-61).

The Genre of the “War Film”

Film historians and critics divide films into various genres such as the thriller, science fiction, the western, romances, film noir, and war films and its "sub-genre" of the combat film.

War film one of earliest genres to emerge in history of film. Histories of genre, e.g. Kagan.

I use a broad definition of War Film:

- films made during war - may be combat movies (Guadalcanal Diary), propaganda movies (Bugs Bunny, Capra’s Why We Fight documentaries), historical costume dramas (Harlan’s Kolberg), or dramas (Clouzot’s The Raven)

- films which are directly about war - combat film (Milestone’s Pork Chop Hill), POW film (Renoir’s Grande Illusion, The Bridge on the River Kwai)

- films which are indirectly about war - the returned veteran (The Best Years of Our Lives),

- films influenced in some way by war or ideas about war - science fiction (Lucas’ Star Wars), horror films (Seiler’s Invasion of the Body Snatchers)

“War is Cinema and Cinema is War”: The Place of War in the History of Cinema

The French film critic Paul Virilio’s claim that “War is cinema and cinema is war” has been supported by a number of historians of the war film genre. For example, the Roumanian film historian Manuela Gheorghiu-Cernat, Arms and the Film: War and Peace in European Films (Bucharest: Meridiane, 1983), p. 57 has pointed out that the earliest pioneers of the art of filmmaking, Lumière and Méliès, were attracted for aesthetic and political reasons to the “photogenic quality of military uniforms and ceremonial.” From filming military parades they progressed to the creation of “reconstructed” newsreels of the contemporary wars taking place in the Transvaal and Cuba, but filmed in the suburbs of Paris. Eventually newsreels actually filmed at the frontline (such as the Boxer Rebellion in China, the Balkan wars of 1903, and the Russo-Japanese War) were made. The next step in the evolution of the war film was the celebration of the anniversaries of great historical battles, such as The Siege of Sebastopol (1911) made by the Russian filmmakers Khanzhonkov and Goncharov, and then the production of official instruction films for the military (Manuela Gheorghiu-Cernat, Arms and the Film, p. 61.). As we can see from this short historical account, from the very beginning of the history of cinema filmmakers have served a number of important functions for the state which they continue to fulfill to this day - reporting ongoing wars, celebrating past wars, making training films for future or current wars, and mobilising popular opinion for and participation in war. It seems that only rarely do filmmakers use their talents for opposing war, and when they do it is often years after the war in question. A number of cinema's greatest directors have been closely connected to the political and military establishments of their day and their films have espoused very conservative, even reactionary, points of view. Gilbert Adair notes this connection among great American directors. In a dicussion of Wayne’s The Green Berets Adairs argues:

... it would be silly to write off John Wayne, as some apologists have managed to do, as a political innocent. The ignorance of these so-called ‘innocents’ has a habit of steering them straight into the camp of extreme reaction; and, for a hard-liner, almost all of the American cinema must be accounted as reactionary, with a few of its greatest directors - Griffith, Ford, Vidor, Capra, Fuller - flagrantly so. (Gilbert Adair, Hollywood’s Vietnam: From The Green Berets to Full Metal Jacket (London: Heinemann, 1989), p. 21.)

Parallel to the close ideological ties between filmmakers and the military are the equally close technological ties between war and cinema. In one of the most provocative examinations of the deep historical and strategic relationship between war and cinema, Paul Virilio, War and Cinema: The Logistics of Perception, trans. Patrick Camiller (London: Verso, 1989) argues that cinema in general and the genre of war film in particular has benefited from the “systematic use of cinema techniques in the conflicts of the twentieth century.” (p.1) The technology of modern filmmaking has evolved from the military photography of the American Civil War, to aerial reconnaissance developed in the First World War, and now to the video surveillance of smart missiles in the Persian Gulf War. The camera of the feature war film is a close relative (in more ways than one) of the military’s “sight machine”:

Thus, alongside the ‘war machine’, there has always existed an ocular (and later optical and electro-optical) ‘watching machine’ capable of providing soldiers, and particularly commanders, with a visual perspective on the military action under way. From the original watch-tower through the anchored balloon to the reconnaissance aircraft and remote-sensing satellites, one and the same function has been indefinitely repeated, the eye’s function being the function of a weapon. (Virilio, War and Cinema, p. 3.)

As war has become total in the twentieth century, the “war of pictures and sound” (Virilio, War and Cinema, p. 4.) has become total as well, with a battle-field and a home front dimension. Military commanders require an accurate perception of the forces arrayed on the battlefield. Politicians on the homefront want the civilian population (who send their young men off to fight and who work in the munitions factories) to perceive the war in a way which will maximise their willingness to particpate in and make sacrifices for the war effort. The important part war movies could play in war propaganda was realised very early on. For example, in the First World War D.W. Griffith was the only American director granted permission to visit the battlefields of Europe to film propaganda material; Frank Capra was given unlimited access to documentary war footage in the creation of the Army training films Why We Fight during World War Two; the controlled release to the TV networks of only the successful “shots” of the smart missiles in the Gulf War. With control over access to documentary footage and censorship of what could be shown at home in the cinemas, the state rapidly hitched the film industry (and now TV) to the wagon of the war effort.

Thus Virilio’s claim that “War is cinema and cinema is war” is not as ludicrous as it first may appear (Virilio, War and Cinema, p. 26.)

The Sub-Genre of the “Combat Film

See Jeanine Basinger, The World War II Combat Film: Anatomy of a Genre (New York: Columbia University Press, 1986).

Argues that during WW2 a “formula” for making combat movies emerged which developed into a new genre of “combat film” and which was very influential in the post-war period. Importance of 2 1943 films in defining genre:

- 1. Tay Garnet’s Bataan

- 2. Lewis Seiler’s Guadalcanal Diary

Based on Bataan the “generic requirements” of combat film are as follows:

See pp. 61-2 of Basinger.

Basinger then creates a “list” or “formula” for a combat movie with which anyone could write a screenplay for one. The film historian, Jeanine Basinger, believes that during WW2 combat movies evolved into a formulaic “genre” with identifiable elements and characteristics which define the genre’s “anatomy”:

From these films of 1943 comes a list of elements to be found which repeat and recur in the combat genre. We know Guadalcanal Diary to be an on-the-spot-correspondent’s account of an actual battle. And yet the story might as well have been thought up in Hollywood by someone who had never been there. Setting aside differences in military uniform and weapons, and thus the attendant differences in mission and type of combat, Destination Tokyo, Bataaa, Air Force, Sahara and Guadalcanal Diary are the same movie. This “list” can be put in two forms:

A. As a “story” of a film the “story” which becomes what everyone imagines the combat genre to be, but which, in fact, does not exist in any pure form in any single film. It is this “story” that the satirists use in TV skits, but it is also the thing that filmmakers would later use to create new genre films.

B. As an outline of elements and characteristics, to be used in analyzing films of the genre. (Jeanine Basinger, The World War II Combat Film, p. 73).

See long list of items pp. 73-75.

This raises the ingtriguing issue of whether or not all combat movies are basically “the same movie” made over and over again which might make it unlikely that this genre of war film would have anything new to say after a certain number have been made.

Are War Films ever True?

When one reflects upon the relationship between war films and the study of history one needs to keep in mind the question Norman Kagan posed in his history of The War Film: A Pyramid History of the Movies (New York: Pyramid Publications, 1974): “are war films ever true?” Before answering this difficult question Kagan poses a series of related questions “true to what?”

- - True to war? What do their depictions of characters and events have to do with the real ones? What is the difference between Sergeant York and Sergeant York, and what does it mean? Can we ever film “courage” or “strategy”?

- - True to history? History is not just the “facts” but principles, explanations, causes and effects. What does All Quiet on the Western Front or The Dirty Dozen suggest, omit, or falsify about the history of war?

- - True to film? Are there special techniques and conventions for war movies? Are there approaches that lend themselves to such films? What are the tricks, shortcuts and conventions behind the cameras?

- - True to their time? How do these films reflect the beliefs current when they were made? How do their stories suggest underlying social ideas, motives, and emotions?

- - True to art? Do the war films’ conventions relate to other arts, e.g., the young hero or old warrior types in Renaissance portraiture? In general, how does adaptation reshape a war novel into a war film?

I would add a question of my own to Kagan's useful list - are war films true to humanity? Do war films increase our understanding of the human condition. Do they contribute to the creation of a tolerant, peaceful and prosperous human community? Or do they excite intolerance, promote violence, and inspire hatred of others?

The Moral Problem of Showing War Films

1. Manuela Gheorghiu-Cernat - "A Pedagogy of Peace or a School of Violence?"

In closing I would like to address the challenging question posed by Manuela Gheorghiu-Cernat about the educational function of war films - are they a pedagogy of peace or a school of violence? (pp. 303-23). Perhaps Fritz Lang is correct when he asks (in a 1958 interview): “Could anything new be possibly said on war?... No. But, it is essential for us to repeat over and over again, the things previously uttered.” (Quoted in Manuela Gheorghiu-Cernat, Arms and the Film, p. 304.) Lang's unstated assumption is that in the 20th century film is to be the medium through which this restatement of the horrors and evil of war can and should be made. We need to ask ourselves whether film, rather than the written word, is the proper medium for this dialogue. Or perhaps Georges Duhamel is closer to the mark with his prediction: “I shall no longer be able to think what I want. My thoughts will be replaced by mobile images.” (Quoted in Manuela Gheorghiu-Cernat, Arms and the Film, p. 305.) The American soldiers in Vietnam who had watched John Wayne westerns and war movies had such mobile images in their minds - images of heroic actions, self-sacrifice for the state, and glorious death on the battlefield. The great power cinema has is the capacity to offer such “mobile images”, with their associated political and moral meanings, for the purposes of distraction, excitement, amusement, and the political control of audiences. Thus educators have a special responsability to use this medium carefully.

What I try to do in my use of film in the teaching of history is to make explicit what is implicit in the mobile images on the screen, to place in historical context what might appear at first sight timeless and “normal” to the viewer, to discuss the moral beliefs and the political orientation of filmmakers and the impact these ideas have on their filmmaking, and to examine the reception of the films by the audiences of their day. To return to Kagan's useful list of questions I quoted earlier, I try to answer the following: are the films true to war, are they true to history, are they true to their time? I also attempt to answer my own question: are the films true to humanity? In many cases they are and the discussions and essays they provoke are the proof.

2. Roger Manvell and The Moral and Historical “Lessons” of War Films

The sufferings of the immediate past have been put on living record as never before, and we have the means in both the cinema and television to make these sufferings and their consequences known to audiences of a size unimaginable even half a century ago (written in 1974).

... The cinema’s great gallery of pictures of the Second World War, so much of it seen at first hand and culminating in the horrifying climax of genocide and death from nuclear devastation, show what armed conflict in the twentieth century has come to mean for both soldiers and civilians. The new generation can study these portraits of human disintegration and suffering at first hand. This vicarious experience projected constantly on the cinema and television screens should in all conscience be sufficient to prevent any further resort in man’s future history to universal war. (pp. 350-51)

These observations raise the question whether or not violent films can serve a moral or educational purpose (as Manvell and Gheorghiu-Cernat argue: Manvell, pp. 350-51; Gheorghiu-Cernat, Arms and the Film, pp. 303-23.) And these related questions:

- Do war films increase our understanding of the human condition?

- Do they contribute to the creation of a tolerant, peaceful and prosperous human community?

- Do they excite intolerance, promote violence, and inspire hatred of others?

- Does the “personalisation” of killing (i.e. seen through the eyes of one character) dramatise or trivialise the problem?

- Why do people go to see violent films? for excitement? as a release of frustration? out of habit?

- How should the viewer react? can or should one remain morally neutral?

- Should violent war movies be banned?

Thinking about War Movies as an Historian (and some tips on writing the essay)

Although this subject deals with texts drawn from a broad range of disciplines (literature, art, music, film, music, economic and political thought) the approach to take in analysing them is an historical one. In your reading and writing I would like you to examine the personal experience of and response to war of a number of individuals of your choice. To do this historically you need to keep the following in mind:

1. Biography

Biography (e.g. what personal experience of war did the individual concerned have and what impact did it have on them?, in other words - what was their response to war?). Biographical information can be found in autobiographies, biographies, memoirs and other critical works written by historians, encyclopaedias.

2. Historical Context

Historical Context (what were the main events and significance of the war experienced by that individual and/or what contemporary events influenced the individual when the text was created?). Works to consult for this information include standard histories of the war in question, historical works on the country or period in which the individual lived and worked. There are a number of levels of historical contexts of which you should take note (Olivier’s Henry V is taken as an example :

- the context of the actual war and the historical figures engaged in that war - e.g. the 100 Years War and King Henry V

- the context in which Shakespeare wrote the play - e.g. events in late 16th and early 17th England, the rivalry between England and Spain, problems ih Ireland, political assassinations

- the context in which the film was made - e.g. WW2 Britain, propaganda funded by the British govt to bolster the war effort

- the context of the audience watching the film - Adelaide, 1996

3. Historical Origins

Historical Origins (what are the origins of the ideas/approaches/style used by the individual in their response to war? what earlier writers, artists, filmmakers, philosophers influenced their work?). Information on the intellectual origins of the response of individuals can be found in specialised critical works on the author or filmmaker, histories of art, music, film etc.

4. Historical Accuracy

Historical Accuracy (are the events depicted in the text or film “accurate” when compared with standard historical accounts of the war in question? Are they similar to other accounts by eye-witnesses, other novels, other films? If the text or film is not accurate, why has history been distorted? for what (political) purpose? Information to judge the historical accuracy of a film or text can be found in standard histories of the war in question.

So, when it comes to writing a paper on the war films we need to keep a number of points in mind, most especially that the essay should not be a mere recitation of what happened in the film but a critical evaluation of the way in which war is presented in the film. In addition to the specific topic on which you will write, some more general issues you might like to consider include the following:

- is the film historically accurate

- is it based upon the experiences of someone who participated in the war

- what view of war does the director give us (heroic, realistic, critical, absurd, inevitable, etc.)

- what effect is war shown to have on those directly involved (such as the leaders and foot soldiers)

- what effect does the film have on the viewer

- how successful is the film in achieving the aims of the director?, and so on.

Standard kinds of essay questions to consider are, roughly in increasing order of difficulty:

- Assess the historical accuracy of the film.

- Discuss the way in which the author’s and/or flicker’s personal experience of war has influenced the image of war presented in the film.

- Discuss the image of war presented in the film (with reference to the historical sources of and contemporary influences on that image).

- The American historian Robert Rosenstone has observed that: “No matter how serious or honest the filmmakers, and no matter how deeply committed they are to rendering the subject faithfully, the history that finally appears on the screen can never fully satisfy the historian as historian (although it may satisfy the historian as filmgoer). Inevitably, something happens on the way from the page to the screen that changes the meaning of the past as it is understood by those of us who work in words.” (Robert A. Rosenstone, “History in Images/History in Words: Reflections on the Possibility of Really Putting History into Film,” American Historical Review, December 1988, vol. 93, no. 5, pp. 1173-85. Quote on p. 1173.) Discuss Rosenstone’s claim, that the process of transferring words on the page of a history book to flickering images on a screen changes “history” into something else, with respect to your chosen film/s.

1. Historical Accuracy of the Film

Make sure you choose your question appropriately. For example, it may not be appropriate to choose the historical accuracy question to discuss films about wars of the future! For example, Cameron’s Aliens has much to do with the Vietnam War so Question 3 on the image of war in the film would be more appropriate. However, you might be able to take this approach with H.G. Wells and Cameron Menzies’ Things to Come by assessing the accuracy of their predictions about future war. Most films are more straightforward than this. A useful way to approach this question is:

- to establish the novelist’s and/or filmmaker’s credentials to comment on war accurately (what was their personal experience of war). The sources for this are biographies, autobiographies, interviews, critical works on the novelist or filmmaker.

- to read some standard historical accounts of the war in question and/or some oral histories of veterans of that war and then compare and contrast events, episodes, recollections, etc. from the histories with the film/novel in order to evaluate its historical accuracy.

- to explain how and why the novel or film is inaccurate, partial, one-sided - especially taking into account the historical context of the time when the novel or film was made (in many cases years after the events in question).

2. Personal Experience of War

Concerning the second question, many films are based upon novels written by individuals who personally experienced war (e.g. Erich Maria Remarque’s All Quiet on the Western Front (1929. In this case, your primary interest would be in the war experience of the novelist with a secondary interest in the way in which this war experience is transferred to the screen, noting in particular any differences between novel and film. Also, many filmmakers had some direct experience of war (e.g. John Ford in WW2) but others, like Kubrick, have none (other than living through the Cold War). Their response to war is an intellectual rather than an experiential one, thus question three would be more appropriate for a paper on Kubrick (although you could choose question 2 and refer to the war experience of the screenplay writers Hasford and Herr for Full Metal Jacket (1987. To answer this question you would need to examine the following:

- the direct personal experience of war (especially any combat experience) of both the novelist and filmmaker. The sources for this are biographies, autobiographies, interviews, critical works on the novelist or filmmaker.

- the reasons for writing the novel or making the film (and the historical context in which this was done). Secondary sources dealing with the cultural history of the time the novel and/or film were made would provide this information.

- specific ideas, themes, incidents, interpretations about war and combat and their impact on individuals and societies which appear in the novel and/or film. You need to refer to specific passages in the book and specific scenes in the film to discuss this adequately.

- an overall evaluation of the novelist’s and/or filmmaker’s response to war. This can often be best done by comparing and contrasting their response to that of others or by discussing how other historians and critics have evaluated their responses.

3. The Image of War

The third question is a more general question to provide an opportunity to discuss some of the hard to classify films (future war films, films made by individuals with no direct war experience, deeply philosophical or simply brilliant or beautifully made films about war). If you choose this question you will need to discuss the meaning and symbolism of the images created by the filmmaker. This may require some philosophical, literary, artistic, religious, filmic and/or cultural analysis. I welcome this approach but would like to remind you of the essential historical method required in this subject. The question of the historical origins of these ideas/images/meanings, their change over time, and the influence of contemporary events on the filmmaker (i.e. biography, historical context) must be included in your discussion. English, Cultural and Film Studies students please take note!

4. History into Film

The fourth question is a more difficult one and requires some reading and reflection on the nature of film itself, especially the difficulties of turning “history” into “film” and vice versa. With regard to Rosenstone’s claims about turning history into flickering images on the screen (American Historical Review, December 1988, p. 1173) we need to ask ourselves:

- What is the process by which a memoir, novel, historical account of a war, etc. gets made into a film?

- What demands must a filmmaker satisfy in making a film and how is this done (consider the roles of the studio, financial backer, the viewing public, screenplay writer, critics, actors, producers, director’s personal vision)?

- What steps can a filmmaker take to ensure the “historical accuracy” of a film?

- Discuss the role of a professional academic historian as “historical advisor” to a filmmaker (e.g. Rosenstone on “Reds”, Zeman Davis with “The Return of Martin Guerre”, Bill Gammage with “Gallipoli”)

- What is the difference between history as words on a page and history as flickering image on a screen?

A Summary of the Questions to Ask Yourself

Keep in mind the following questions:

- Is the film historically accurate? If not, why not? What is the filmmaker’s purpose in distorting history?

- Is it based upon the experiences of someone who participated in the war? (directly in the case of the director, or indirectly if it is based upon a novel written by someone who had personal experience of war)

- What is the historical context in which the film was made? does this influence the way war is depicted in the film?

- What view of war does the director give us? (heroic, realistic, philosophical, critical, absurd, inevitable, tragic, exciting)

- What effect is war shown to have on those directly involved (military leaders, foot soldiers)? on those indirectly involved (home front)?

- What effect does the film have on the viewer? on you?

- How have other filmmakers treated the same war or conflict?

- What was the reception of the film when it was first released?

- Can the film be interpreted in different ways? on different levels?

- How successful is the film in achieving the aims of the director?

- Has the director made other war films? if so, how is war treated there?

- How should one use other reviews and secondary sources in writing your own review?

- How does one “quote” from a film? (dialogue, images, scenes)