The Institut Coppet has recently published volume 9 of the Œuvres complètes (Complete Works) of Gustave de Molinari, thus completing the first 10 years of his long and very productive life. Only 60 more years to go!

See a comprehensive (though probably still not complete) bibliography of his works which consists of 73 Books, Printed Pamphlets, and Intros to books; and 240 articles.

I have also put online dozens of his stand alone books and magazines/journals which he edited and wrote for, as well as three anthologies of his work:

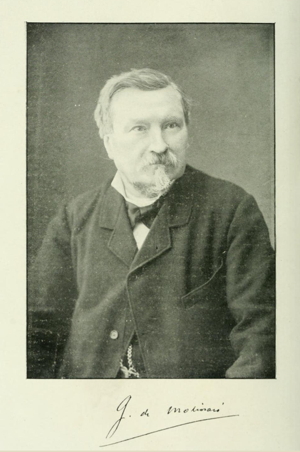

- an overview of his life and work: “Gustave de Molinari (1819–1912): A Survey of the Life and Work of an “Économiste Dure” (A Hard-Core Economist)” here

- a bibliography with links to his works online here

- and this list of recently added items

- these three anthologies of Molinari’s writings for the bicentennial: “The Bicentennial Anthology of the Writings of Gustave de Molinari on the State (1846-1911)” (Nov. 2018) the first.

- “The Collected Articles by Gustave de Molinari from the Dictionnaire de l’économie politique (1852-53)” (June, 2019) the second

- “Molinari’s Collected Writings on the Production of Security (1846-1901)” (Aug., 2019) the third.

The Institut Coppet Edition of the Collected Works of Molinari

The set so far consists of the following volumes:

- Volume 1 : Avant la conversion au libéralisme (1842-1845)

- Volume 2: Libre-échange et réforme électorale (1845-1846)

- Volume 3 : Le libre-échange sans compromission (1846)

- Volume 4 : L’entrée au Journal des économistes (1846-1847)

- Volume 5 : Dans la tempête révolutionnaire (1848)

- Volume 6 : La liberté des gouvernements (1849)

- Volume 7 : La république menacée (1850)

- Volume 8 : La solitude et l’exil (1851)

- Volume 9 : En exil dans son propre pays (1852)

I have put together the full tables of contents of these volumes into one file.

Below are the full publishing details, a brief description of the contents of each volume, and links to the downloadable PDFs (free of charge) from the Institut Coppet website. Below that, there is an abbreviated table of contents listing the 64 main parts of the collection.

Œuvres complètes de Gustave de Molinari, sous la direction de Mathieu Laine, avec le soutien de M. André de Molinari, et avec des notes et notices par Benoît Malbranque (Paris: Institut Coppet, 2019-).

Volume 1 : Avant la conversion au libéralisme (1842-1845). — Les premiers écrits, redécouverts pour la première fois, témoignent que le jeune Molinari était d’abord éloigné des principes du libéralisme. PDF

Volume 2: Libre-échange et réforme électorale (1845-1846). — Après sa conversion, Molinari s’engage dans la défense du libre-échange aux côtés de Bastiat, dans des textes retrouvés pour la première fois et inédits. PDF

Volume 3 : Le libre-échange sans compromission (1846). — Suite des articles inédits de Molinari sur le libre-échange. L’auteur s’affirme progressivement comme un libéral radical. PDF

Volume 4 : L’entrée au Journal des économistes (1846-1847). — Suite des articles inédits. Ayant fait ses preuves, Molinari intègre aussi le Journal des économistes et le « réseau Guillaumin ». De larges notices donnent sur ces faits des éclairages tout à fait nouveaux. PDF

Volume 5 : Dans la tempête révolutionnaire (1848). — Les évènements révolutionnaires de février et juin 1848 forcent Gustave de Molinari à abandonner ses premiers combats, notamment en faveur du libre-échange, pour une action journalistique de réaction qui doit sauver les assises de la société face à la menace rouge. Après une large notice, en tête de volume, revenant sur cet environnement éminemment nouveau, ce volume donne à lire une masse d’articles retrouvés dans la presse parisienne et inexplorés jusqu’à aujourd’hui. PDF

Volume 6 : La liberté des gouvernements (1849). — Après les tremblements de la révolution de 1848, Gustave de Molinari renouvelle la défense de la liberté et de la propriété, notions si attaquées, en étendant le champ d’application du libéralisme traditionnel. Ses théories dites anarcho-capitalistes, sur la privatisation des fonctions régaliennes de l’État et la liberté des gouvernements, sont exposées dans le Journal des économistes puis la même année dans les Soirées de la rue Saint-Lazare, et font date dans l’histoire du libéralisme. PDF

Volume 7 : La république menacée (1850). — Après avoir imaginé la privatisation des gouvernements dans deux contributions fameuses, Gustave de Molinari devait affronter, en journaliste de tous les jours, les déceptions du suffrage universel et les dangers de l’agitation socialo-communiste. Sans grand enthousiasme, mais parce que la survie de la civilisation en dépendait, il se ralliait politiquement au camp de l’ordre, représenté par la figure sans cesse montante et dominante du président bientôt empereur, Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte. PDF

Volume 8 : La solitude et l’exil (1851). — L’année 1851 est une époque de transformations importantes dans le paysage intellectuel de Gustave de Molinari, entre l’annonce de la mort de Frédéric Bastiat, qui ouvre cette année troublée, et le coup d’État du président Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte, qui la clôt et contraint l’auteur à l’exil. Dans des centaines d’articles donnés à la presse quotidienne parisienne, Molinari étudie cette montée en puissance du régime présidentiel bonapartiste, qu’il perçoit d’abord comme une espérance, un rempart face à la « menace rouge », mais qui se révélera finalement plein de dangers. PDF

Volume 9 : En exil dans son propre pays (1852). — Éloigné physiquement de la scène du libéralisme économique français, Gustave de Molinari poursuit sa collaboration aux grandes œuvres du mouvement : le Journal des économistes, et le nouveau Dictionnaire de l’économie politique. En Belgique, il ouvre un cours d’économie politique et prononce des conférences. La menace que Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte représente pour les libertés en France mais aussi en Belgique apparaît lancinante, et domine l’arrière-plan. PDF

The Collected Tables of Contents of the Coppet Edition

Volume 1 : Avant la conversion au libéralisme (1842-1845)

Préface, par Mathieu Laine, p. v

Introduction. — La jeunesse belge de Gustave de Molinari, p. 1

1842

-

(001) CHRONIQUES POLITIQUES (Le biographe universel, revue générale biographique et littéraire), p. 11

-

(002) BULLETIN LITTÉRAIRE (Le biographe universel, revue générale biographique et littéraire), p. 65

-

(003) BIOGRAPHIES (Le biographe universel, revue générale biographique et littéraire), p. 70

1843

-

(004) LAMARTINE, p. 99

-

(005) CHEMINS DE FER ET BOURSES DE TRAVAIL, p. 164

1844

-

(006) LE SORT DES CLASSES LABORIEUSES, p. 201

-

(007) ÉTUDES ÉCONOMIQUES. Le Courrier français, octobre-novembre 1844, p. 215

-

(008) L’INSTRUCTION PUBLIQUE. Des compagnies religieuses et de la publicité de l’instruction publique, 1844, p. 241

-

(009) LE COURRIER FRANÇAIS, p. 264

1845

-

(010) LE COURRIER FRANÇAIS, p. 287

-

(011) LA MOBILISATION DU TRAVAIL. De la mobilisation du travail, La Réforme, 9 juin et 9 juillet 1845, p. 352

-

(012) LE COURRIER FRANÇAIS, p. 371

Annexe, p. 447

Volume 2: Libre-échange et réforme électorale (1845-1846)

1845 (suite)

-

(013) UN NOUVEL ENVIRONNEMENT INTELLECTUEL, p. 5

-

(014) LE COURRIER FRANÇAIS, p. 30

1846

-

(015) ÉTUDES ÉCONOMIQUES, p. 226

-

(016) LA RENCONTRE AVEC FRÉDÉRIC BASTIAT. Souvenirs, p. 313

-

(017) LE COURRIER FRANÇAIS, p. 315

Volume 3 : Le libre-échange sans compromission (1846)

1845 (suite)

-

(018) LE COURRIER FRANÇAIS, p. 5

-

(020) LE COURRIER FRANÇAIS, p. 273

-

(021) LA QUESTION DES SUBSISTANCES. CONTRE LAMARTINE, p. 399

-

(022) LE COURRIER FRANÇAIS, p. 411

Volume 4 : L’entrée au Journal des économistes (1846-1847)

1846 (suite)

-

(023) LA QUESTION DES DOUANES, p. 5

-

(024) LE COURRIER FRANÇAIS, p. 53

-

(025) ASSOCIATION POUR LA LIBERTÉ DES ÉCHANGES, p. 98

1847

-

(026) LE COURRIER FRANÇAIS, p. 107

-

(027) LA QUESTION DES DOUANES, p. 120

-

(028) LA QUESTION DES SUBSISTANCES, p. 214

-

(029) LE JOURNAL DES ÉCONOMISTES, p. 221

-

(030) SITUATION ÉCONOMIQUE DE L’ANGLETERRE ET DE L’IRLANDE, p. 238

-

(031) CONFÉRENCES LIBRE-ÉCHANGISTES EN BELGIQUE, p. 315

-

(032) CONGRÈS DES ÉCONOMISTES À BRUXELLES. Souvenirs, p. 320

-

(033) JOURNAL LE LIBRE-ÉCHANGE, p. 325

-

(034) UNE CRITIQUE DE PROUDHON, p. 342

-

(035) LE TRAVAIL INTELLECTUEL, p. 381

-

(036) HISTOIRE DE L’ÉCONOMIE POLITIQUE, p. 422

-

(037) UN COURS D’ÉCONOMIE POLITIQUE, p. 442

Volume 5 : Dans la tempête révolutionnaire (1848)

1848

Introduction. — De nouvelles circonstances, p. 5

-

(038) LA RÉPUBLIQUE FRANÇAISE, p. 29

-

(039) LE CLUB DE LA LIBERTÉ DU TRAVAIL, p. 95

-

(040) LA SOCIÉTÉ D’ÉCONOMIE POLITIQUE, p. 98

-

(041) HISTOIRE DE L’ÉCONOMIE POLITIQUE, p. 115

-

(042) JACQUES BONHOMME, p. 171

-

(043) LE JOURNAL DES ÉCONOMISTES, p. 196

-

(044) LE COMMERCE, p. 256

Volume 6 : La liberté des gouvernements (1849)

1849

-

(045) CORRESPONDANCE, p. 5

-

(046) LE JOURNAL DES ÉCONOMISTES, p. 12

-

(047) L’ABOLITION DE L’ESCLAVAGE, p. 71

-

(048) LES SOIRÉES DE LA RUE SAINT-LAZARE, p. 80

-

(049) LA LIBERTÉ DES THÉÂTRES, p. 301

-

(050) LA PATRIE, p. 334

-

(051) LA SOCIÉTÉ D’ÉCONOMIE POLITIQUE, p. 468

-

(052) MARIAGE avec Mlle Edmée Terrillon. Annonce officielle, p. 470

Volume 7 : La république menacée (1850)

1850

-

(053) LA PATRIE, p. 5

-

(054) LE JOURNAL DES ÉCONOMISTES, p. 258

-

(055) LA PATRIE, p. 306

Volume 8 : La solitude et l’exil (1851)

1851

-

(056) LA PATRIE, p. 5

-

(057) LE JOURNAL DES ÉCONOMISTES, p. 605

-

(058) SOCIÉTÉ D’ÉCONOMIE POLITIQUE, p. 689

Volume 9 : En exil dans son propre pays (1852)

1852

-

(059) COURS D’ÉCONOMIE POLITIQUE AU MUSÉE DE L’INDUSTRIE, p. 5

-

(060) CORRESPONDANCE AVEC RICHARD COBDEN, p. 22

-

(061) SOCIÉTÉ D’ÉCONOMIE POLITIQUE, p. 25

-

(062) LE DICTIONNAIRE DE L’ÉCONOMIE POLITIQUE, p. 49

-

(063) CONFÉRENCE AU CERCLE ARTISTIQUE ET LITTÉRAIRE, p. 243

-

(064) LE JOURNAL DES ÉCONOMISTES, p. 244

-

(065) RÉVOLUTION ET DESPOTISME, p. 369