BROKEN WINDOWS: AN ILLUSTRATED HISTORY OF THE LIFE AND WORK OF FREDERIC BASTIAT

By David M. Hart↩

[Updated: August 2, 2016 ]

[Some broken windows and a travelling glazier]

The Life and Work of Frederic Bastiat (1810–1850)

[Frédéric Bastiat (1801–1850)]

This “illustrated history” should be read in conjunction with A Reader’s Guide to the Works of Frédéric Bastiat (1801–1850).

It is also a supplement to a screenplay I have written also called “Broken Windows” a draft of which can be found here.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

- Structure of Acts and Blocks of Scenes

- OPENING: DEATH ON THE BARRICADES IN JUNE 1848

- ACT I: FROM PROVINCIAL MUGRON TO PARIS (1843–44)

- ACT II: SUCCESS IN PARIS (1845–47)

- Paris in the 1840s

- The Guillaumin Circle

- Political Cartoons in FB’s Office

- A Wall Poster advertising a Free Trade meeting.

- Getting around the Ban on Political Meetings 1: Singing Societies or Goguettes

- Getting around the Ban on Political Meetings 2: A Political Banquet in late 1847

- Delacroix’s ceiling in the Palais Bourbon (Leg. Ass)

- ACT III: REVOLUTION AND CRISIS BETWEEN FEBRUARY AND JUNE 1848

- ACT IV: RESOLUTION - FROM JUNE 1848 TO DEC. 1850

- Coda: The Aftermath

Structure of Acts and Blocks of Scenes↩

- Opening: Death on the Barricades June 1848

- I. From Provincial Mugron to Paris (1843–44)

- II. Success in Paris (1845–47)

- III. Revolution and Crisis between Feb. and June 1848

- IV. Resolution June 1848–50

- Coda: The Aftermath

Scenes used multiple times↩

- FB’s home in Mugron

- Guillaumin’s publishing HQ in Paris

- FB’s office at the French Free Trade Association on rue de Choiseul

- the Chamber of the Constituent Assembly

- Butard Lodge in woods outside Paris

Scenes with broken windows:↩

- I. Opening sequence of June 1848 barricades

- I. Jacque Bonhomme’s shop and court session

- I. a protest in Paris at high bread prices

- III. Opening sequence, troops firing on protesters Feb 1848

- III. Club Lib broken up by socialists

- III. fighting on a street barricade in June 1848

- IV. martial law is declared and the political clubsHortense Cheuvreuxre shut down

Big Set Pieces - Interior Scenes:↩

- Chamber of General Council in Mont-de-Mersan

- Welcome dinner for FB in Paris

- Free Trade meeting at Montesquieu Hall

- Hippolyte Castille’s salon on rue Saint-Lazare

- Hortense Cheuvreux’s salon in her Paris home

- Committee Room in Chamber of Deputies; the ceiling of the Library in Palais Bourbon (Leg. Ass)

- Club Lib meeting room; other Clubs

- FB’s speeches in Chamber (Const. Assembly)

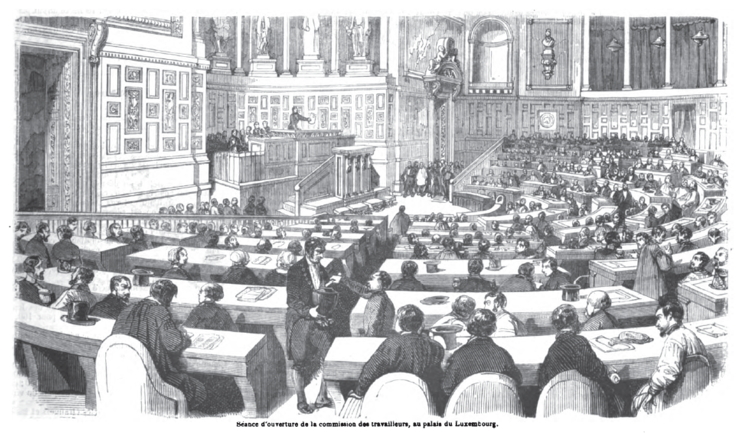

- Louis Blanc in Luxembourg Palace

- attempt by Blanc’s supporters to seize Chamber in May 1848

- Peace Congress at St. Cecilia Hall

Big Set Pieces - Exterior Scenes:↩

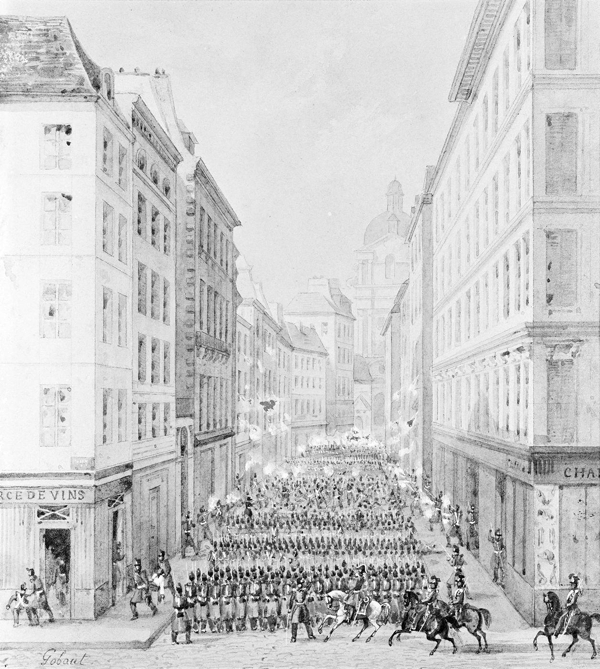

- military parade for King Louis Philippe and inspection of troops on the wall

- riot in street over high price of bread - smashing of bakery

- a Political Banquet in a Paris park

- protest march in Paris Feb 22 which triggered Rev.

- 1st street barricade scene in Feb. 1848

- protest March in June over threat to close Nat Workshops

- 2nd street barricade in June 1848

Panoramic Scenes of Historical Note↩

- bird’s eye of Paris in June 1848 showing barricades, etc.

- Les Landes countryside - flying camera in opening sequences to show mountains, rivers, ag. land, marsh, sheep herders; show stark beauty of south

- the three walls which encircle and confine Paris:

- the octroi wall surrounding Paris

- the military wall and ditch around Paris

- the 16 major forts around Paris

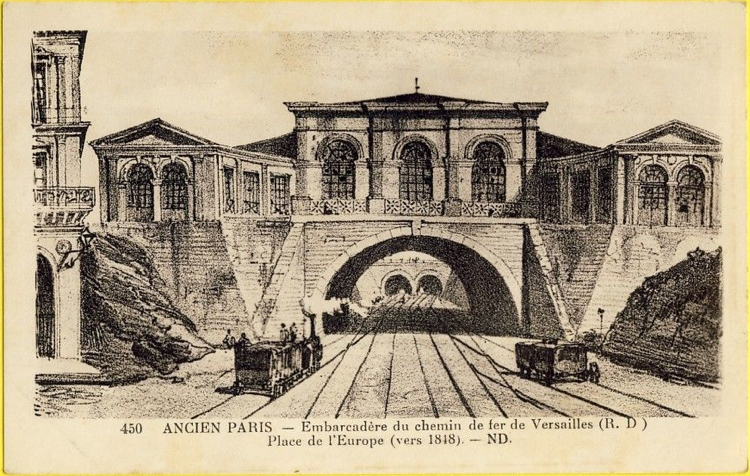

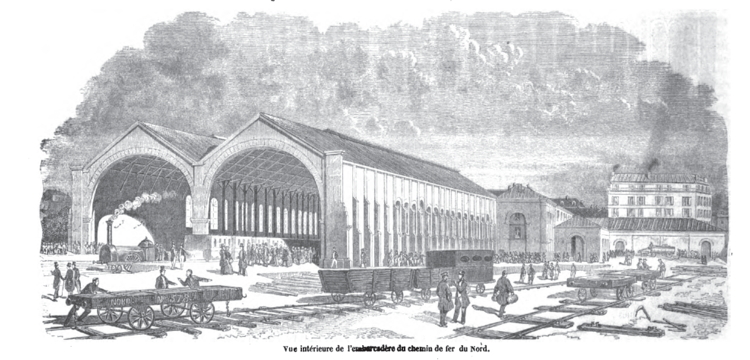

— travelling to Paris by train - one of the new Paris railway stations

Scenes with works of art:↩

- FB’s study in Mugron - print of Delacroix’s “Liberty leading the People”

- ceiling of Palais Bourbon (Leg. Ass) - Orpheus vs. Attila

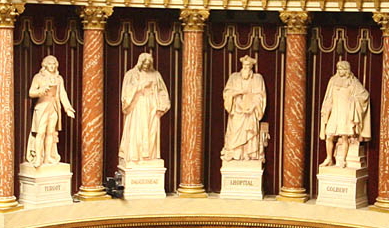

- statues in semi-circle in Luxembourg Palace (Peers, Lux. Com) - Turgot and Colbert

- Delacroix’s “Liberty leading the People” in storage room in Lux. Palace

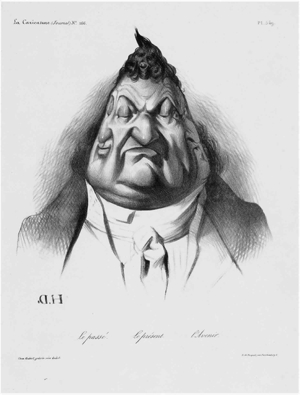

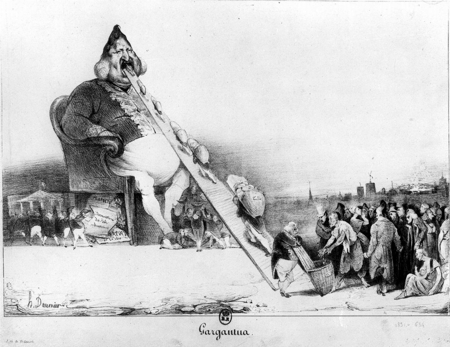

- Daumier cartoons in FB’s office - pear-shaped LP, Gargantua

- Napoleon III as the budget-eating vulture of France

- FB’s statue in Mugron with “Marianne” figure

OPENING: DEATH ON THE BARRICADES IN JUNE 1848↩

On the Barricades↩

[Theme image of the film: Delacroix’s “Liberty Leading the People on the Barricade” (1830)]

[Troops taking the barricade on the rue de la Fontaine-au-Roi, 23 June 1848]

Paris from Above: the Three Walls around the city built by the State↩

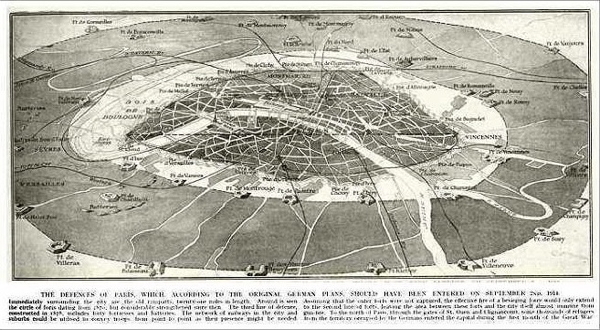

[A birdseye view of Paris and its 3 concentric circles of walls and forts]

[An early 20thC drawing of the ring of fortifications around Paris]

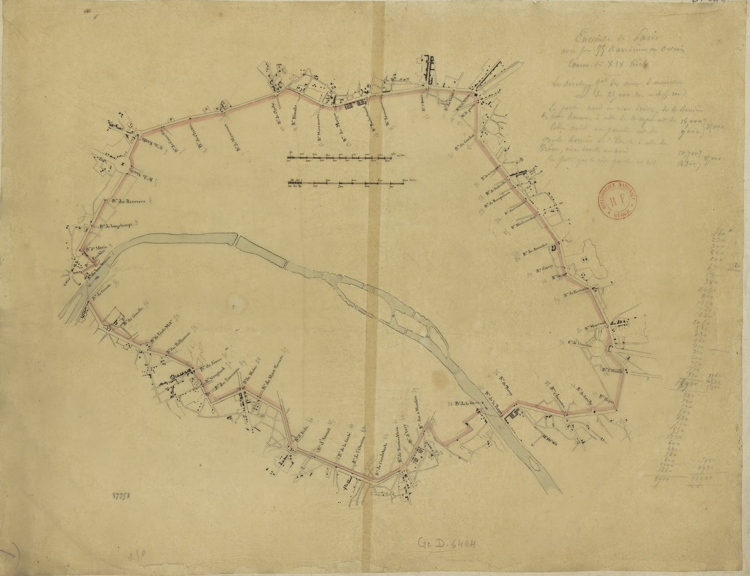

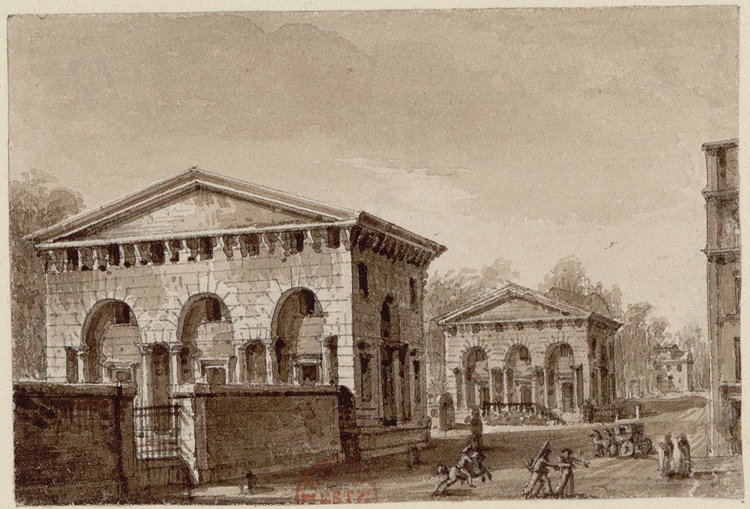

The inner ring of Octroi tax gates and wall

The octroi was a tax on most consumer goods which were brought into the city.

[A Map showing the late 18th century Octroi tax gates and wall encircling Paris. It was built between 1784–90 to enable the private contractors who collected city taxes (the “Farmers General”) to prevent untaxed goods entering the city. There were 55 gates or “barriers” built before the Revolution (eventually there were 61) and the walls extended for 24 km.]

[The Octroi gate and wall at Belleville (built 1786–88)]

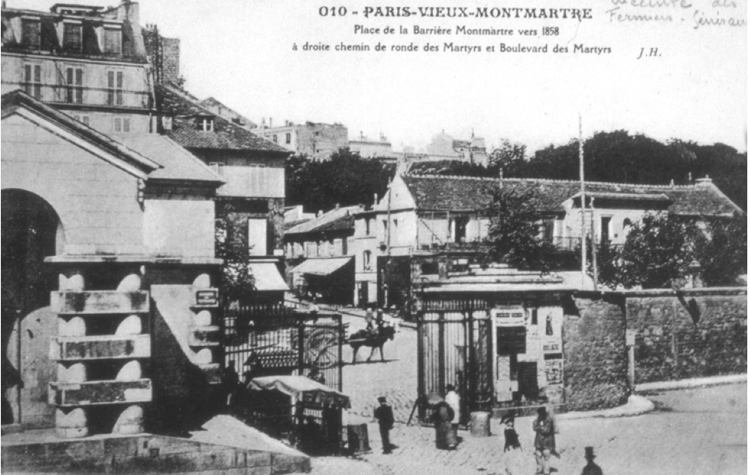

[The Octroi gate and wall at Montmartre]

[Pulling down the Octroi Gates and walls in 1859]

The Fortifications of Paris (1841–45): the middle ring of the military wall and the outer ring of forts

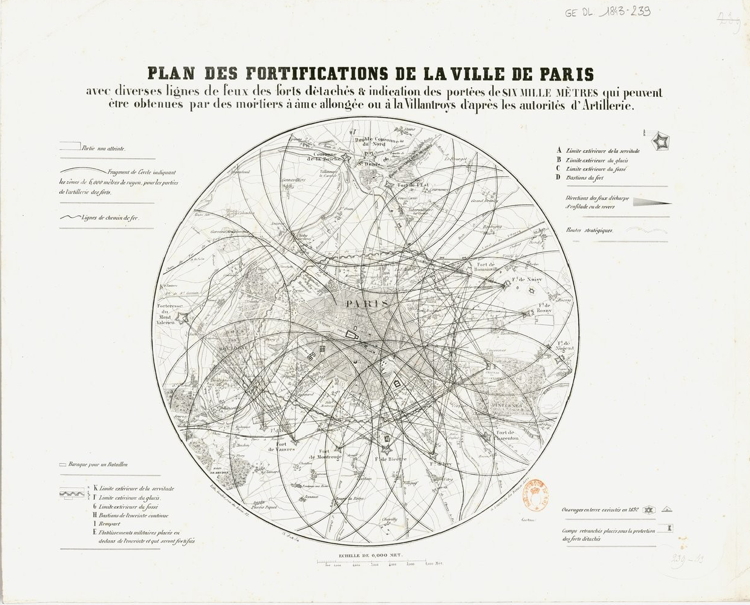

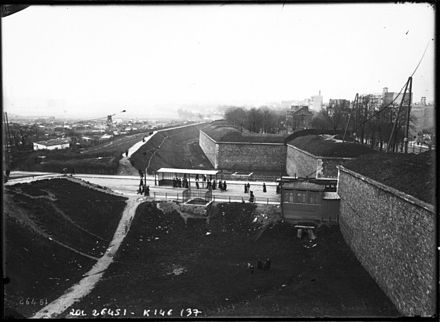

The Prime Minister Adolphe Thiers was the driving force behind the building of the military wall and 16 major forts around the city between 1841–44. It extended for 33 km (20.6 miles) and had 23 main gates for road and foot traffic, 8 entry points for the railways, and 5 for river boats.

[The range and line of fire of mortars and artillery from the 16 forts which encircled Paris]

[A photograph of the Military Wall at the Versailles Entry Gate]

[Cross section of the Wall and surroundings. The wall consisted of an interior military road, a parapet 6 metres high, an exterior wall or escarpment which was 3.5 metres wide and 10 metres high, a dry ditch 40 metres wide, another less steep escarpment which had on the other side gently sloping “glacis” which extended for 250 metres which had to keep clear of any buildings or trees.]

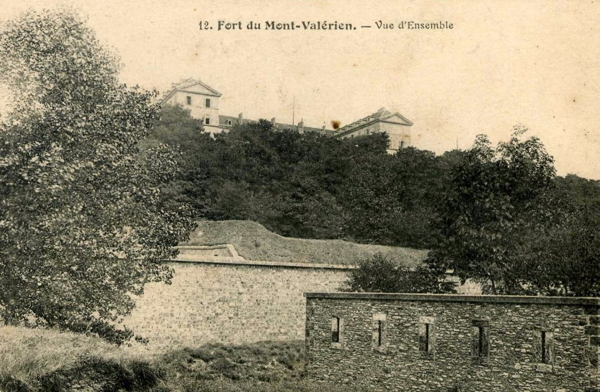

[One of the largest Forts was at Mont Valérien which was a hill overlooking the city. The 16 major forts were built in a classic star shape and contained barracks and storage for enough food and weapons which could withstand a long siege.]

[An aerial view of the Fortress of Mont Valérien looking back over the city of Paris]

ACT I: FROM PROVINCIAL MUGRON TO PARIS (1843–44)↩

FB’s life in Les Landes: Bayonne, Mugron, Mont-de-Mersan (1843–44).↩

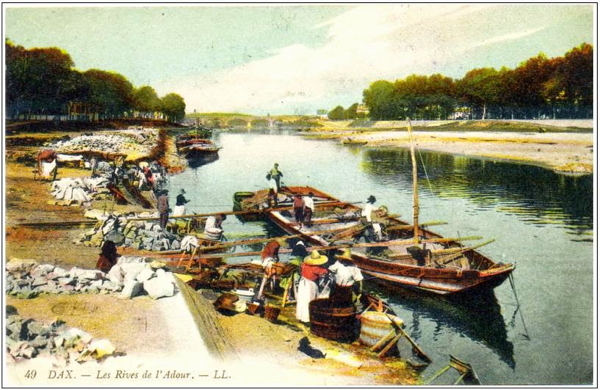

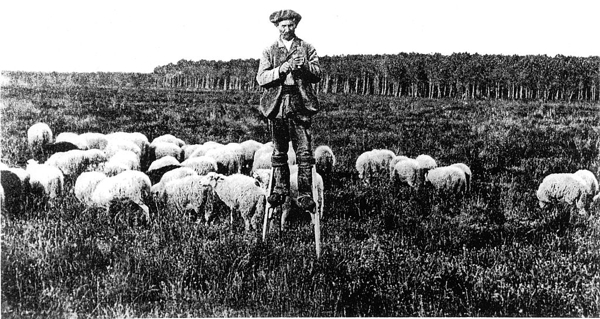

His family ran a business out of the city of Bayonne. Bastiat inherited some land in the region known as La Chalosse near Mugron when his grandfather died. He took up farming and wine growing and had as amny as 150 share-croppers as tenants. He was a magistrate (Justice of the Peace) in Mugron and was a member of the General Council of Les Landes which operated out of the town of Mont-de Mersan. Mugron was on the Adour river which flowed through Bayonne into the sea. To the north of Mugron was a large area of swampy marsh and heath land (“les landes”) which was used for sheep herding.

[Relief map of France. Bayonne is on the Atlantic coast in the south west corner of the map.]

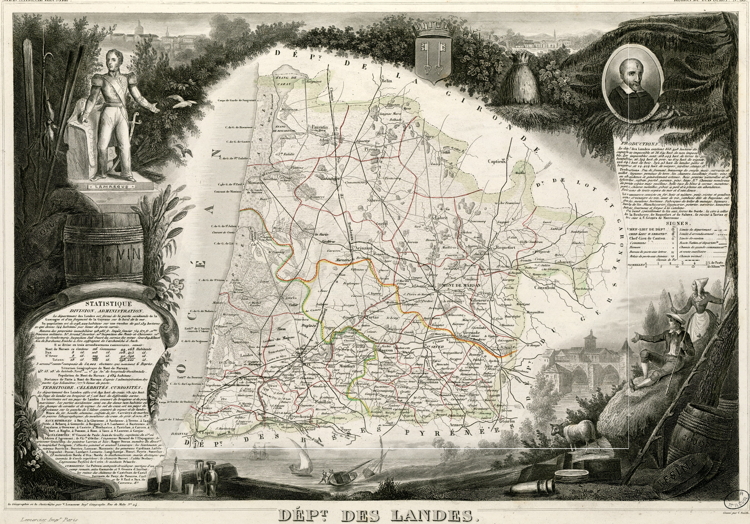

[Map of the Département of Les Landes. To the south are the Pyrénées mountains and the Spanish border. To the north is Bordeaux and the Gironde.]

[Map showing location of Mugron]

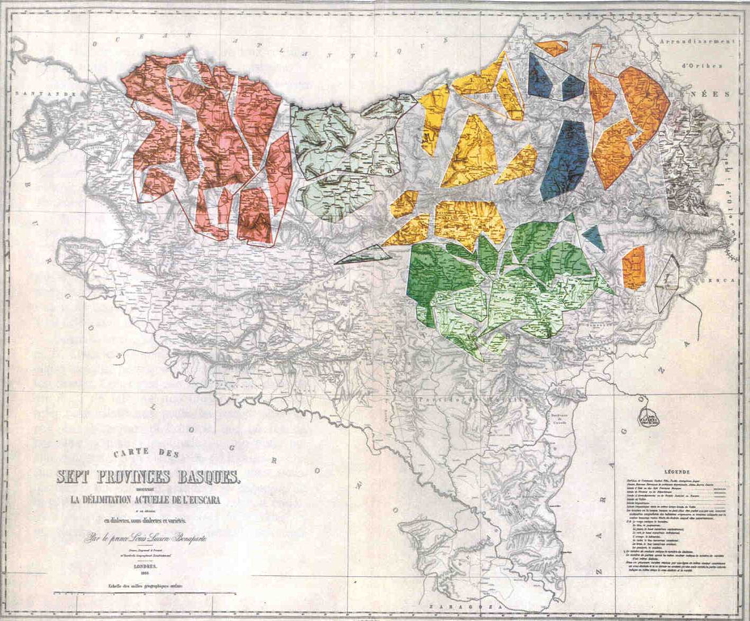

[Bayonne is considered to be the cultural and economic centre of the French “Basque country”. This map of Basque dialects was drawn up Napoléon III’s son Louis Lucien in 1868. The orange, blue and some of the yellow regions are in “France”.]

[Bastiat’s house in Mugron]

[Place Bastiat in Mugron]

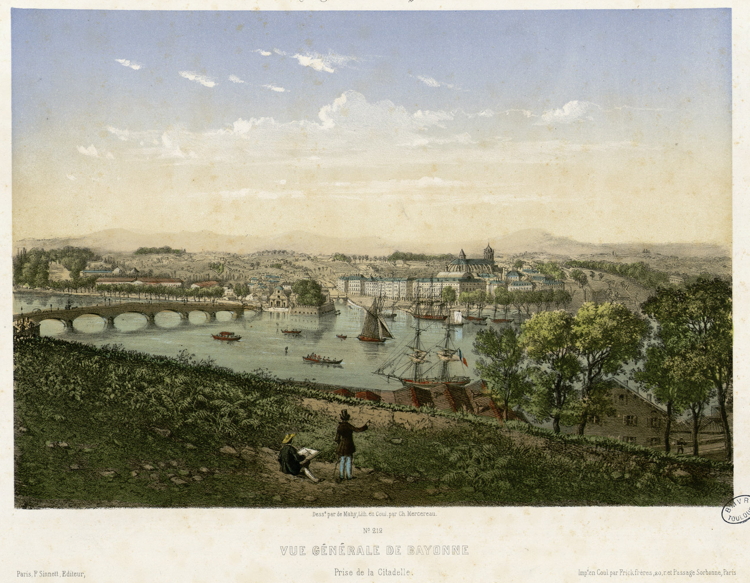

[The port city of Bayonne where Bastiat conducted business. Since it was near the Spanish border and because it was part of the French “Basque country” Bastiat would have hear several languages spoken here: Spanish, Basque, the Gascogne dialect of French, and probably English. He was fluent in all of them except perhaps Basque, of which he knew a little.]

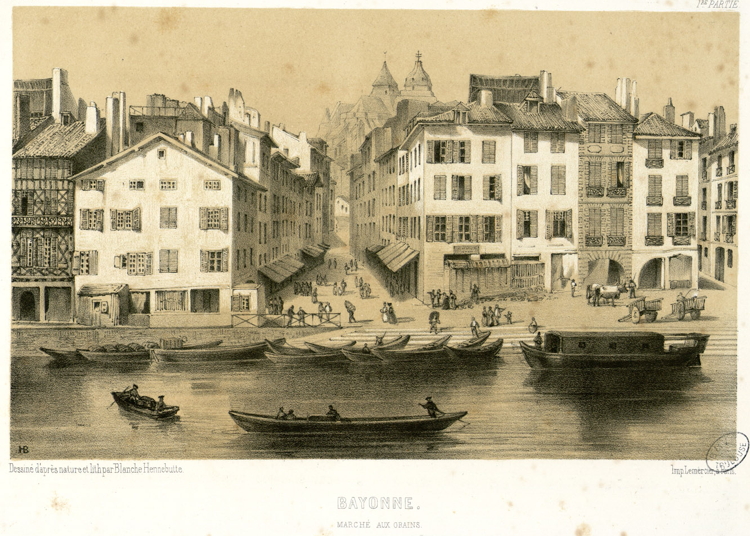

[The main grain market in Bayonne. The Adour river enabled grain and other products from the hinterland (including Mugron) to be brought to market.]

[The military citadelle in Bayonne where Bastiat played a small part in the 1830 Revolution. He was 29 and was a liberal in his political views. When the Bourbon monarchy was overthrown in August 1830 the garrison in Bayonne was split in its loyalties. Bastiat said went late at night to persuade the officers to side with the revolution and the new king Louis Philippe. They drank red wine and sang political songs (by Béranger) into the night and he was able to persuade them to support the new “liberal” monarch.]

[A Basque peasant from the Bayonne region in costume.]

[The Library of the Hotel de Ville in Mont-de-Mersan where Les Landes General Council may have met. In 1833 (at the age of 32) he was elected to the General Council of Les Landes to advise the local government on economic matters. He gave a number of speeches on tax policy and public works projects.]

[The Chalosse valley where Bastiat had his farm]

[Vineyards in the Chalosse region]

[River traffic and commerce on the Adour River at Dax]

[Painting of Landais farmers on stilts. They wore stilts so they could walk quickly over the heath land and so they would not sink into the marshy ground.]

[A Farmer inspecting his tenants]

[A shepherd walking of stilts to better observe his sheep in the heathlands]

[Shepherds on Stilts]

[A bull fight in the local arena in Mugron shows how influential Spanish culture is in Les Landes.]

FB’s Train Trip to Paris↩

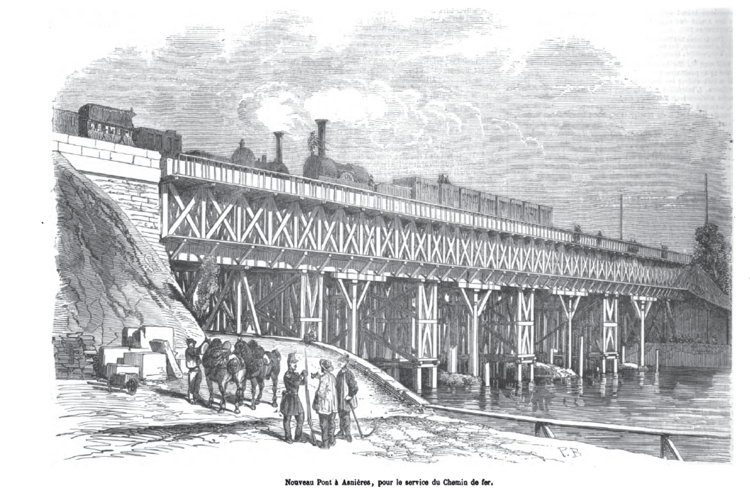

The building of railways began in the late 1830s and a law of 1841 ruled that 5 large networks would serve the provinces and each would have a major railway station in Paris. The government granted concessions to private railway companies and shared building and operating part of the system. The link from Paris to Bordeaux/Bayonne was under construction towards the end of Bastiat’s life.

[Gare chemin de fer Versailles in 1848]

[The railway station of the Northern Line]

[A newly constructed railway bridge]

ACT II: SUCCESS IN PARIS (1845–47)↩

Bastiat wrote some important essays on free trade in late 1844 and came to the attention of the Parisian economists. He went to Paris to meet them in May 1845 and was instrumental in setting up a free trade movement in France between 1846 to the end of 1847. He quickly became an important part of the Guillaumin circle of free market economists and published several works with them during this period.

Paris in the 1840s↩

[A Panoramic View of Paris in the 1840s]

The Guillaumin Circle↩

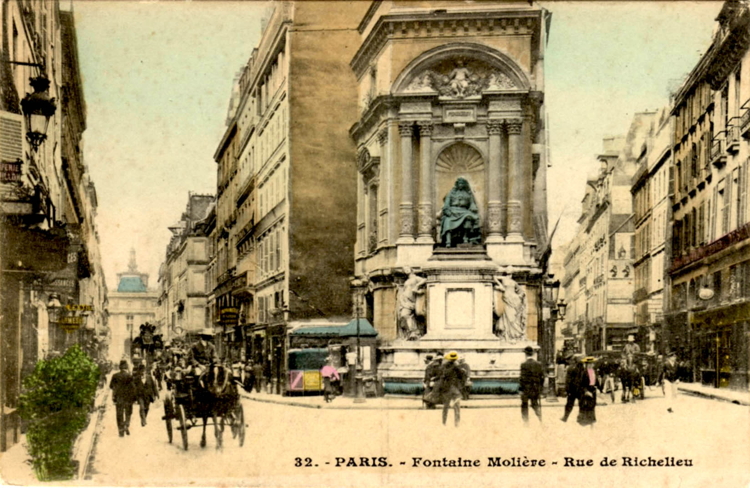

[Guillaumin office and the Molière Fountain, rue Richelieu. The Guillaumin office was down the left street. The Molière statue and fountain was built in 1845 just when Bastiat was visiting Paris. Molière was one of Bastiat’s favourite authors and he quoted him frequently in his writing. ]

Political Cartoons in FB’s Office↩

[King Louis Philippe as a big fat pear]

[King Louis Philippe the “tax-eater” sitting on his throne and shitting privileges]

[The Army Hierarchy. The French Army consisted of about 400,000 men, most of whom were conscripts and served for 7 years.]

A Wall Poster advertising a Free Trade meeting.↩

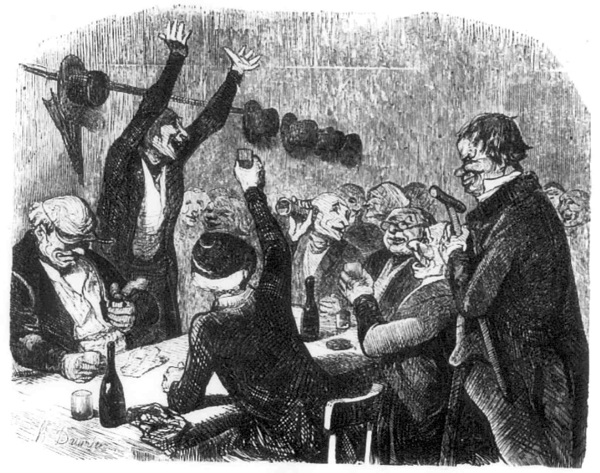

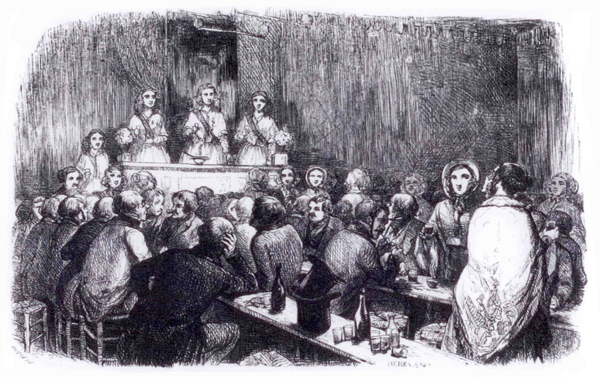

[A Goguette in 1844]

[A drawing of a Goguette by Daumier]

[A Goguette run by Women]

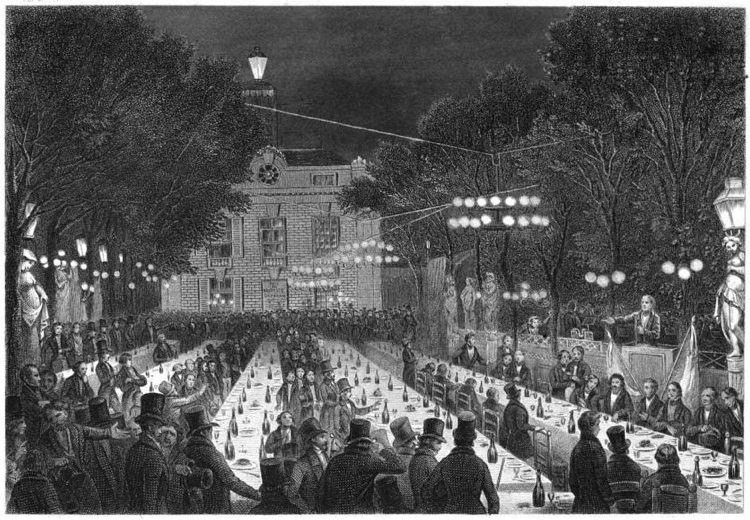

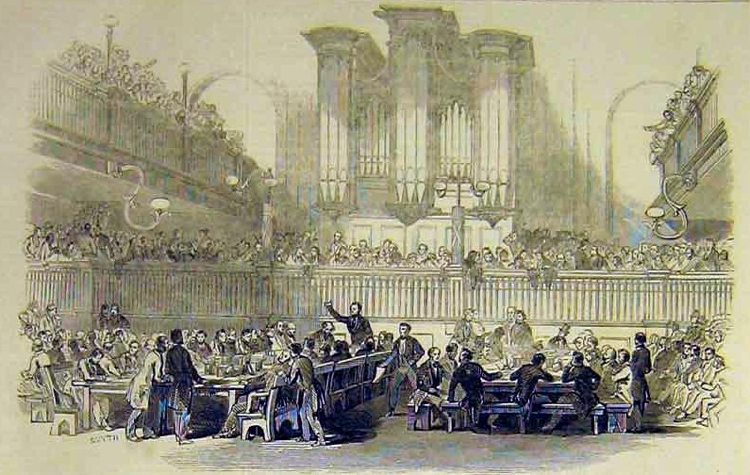

Getting around the Ban on Political Meetings 2: A Political Banquet in late 1847↩

In the summer of 1847 an opposition political movement began to put pressure on the government to lessen the restriction of freedom of speech and association. Since political speeches were banned at the “political banquets” only “toasts” could be given. Since the police had difficulty distinguishing between a long political toast and a short political speech, and since the number of banquets were increasing in number and radicalism, the government banned them in February 1848. A march to protest the banning of a banquet to celebrate the birthday of the republican and democratic George Washington (Feb. 22) triggered the fall of Louis Philippe’s regime and the creation of the Second Republic.

[A Political Banquet in July 1847]

[A Political Banquet held in Feb. 1848]

Delacroix’s ceiling in the Palais Bourbon (Leg. Ass)↩

In the mid and late 1840s Eugène Delacroix painted a ceiling mural for the Library of the Palais Royal which was the seat of the National Assembly. It was a complex allegorical depiction of the struggle between “war” (Attila the Hun) and “peace” (Orpheus). It was completed in 1847.

[Delacroix’s ceiling mural of Orpheus (Peace) vs. Attila (War) 1]

[Delacroix’s ceiling mural of Orpheus vs. Attila 2: “Attila and his hordes overrun Italy and the Arts (1847)]

ACT III: REVOLUTION AND CRISIS BETWEEN FEBRUARY AND JUNE 1848↩

Bastiat’s world was turned upside down because of the Revolution and the rise of socialism in February 1848. The free trade movement he had helped build was put on hold while the economists threw themselves into politics, in particular opposing the rise of socialism in the National Workshops scheme run by Louis Blanc. He was elected in April 1848 to represent Les Landes in the Constituent Assembly of the Second Republic. He was also appointed vice-president of the Chamber’s Finance Committee where he opposed high taxes and excessive government expenditure such as the National Workshops state-funded work programs. He and his friends got caught up in the street fighting in Paris in February and June when many thousands were killed and injured by the army. They were handing out copies of their small revolutionary magazines on the streets defending free markets and criticising high taxes and socialist ideas.

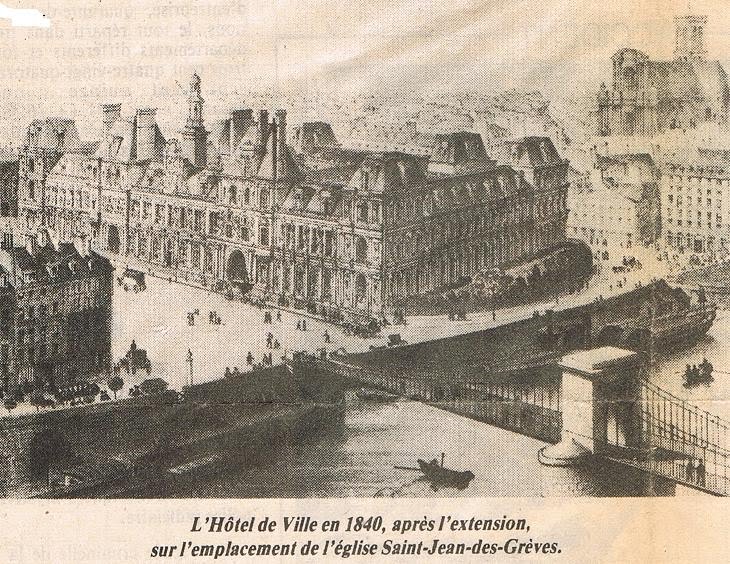

Lamartine declaring the Formation of Second Republic↩

[Lamartine on the steps of the Hotel de ville announcing the Formation of the Provisional Government]

[The Hotel de Ville in 1840]

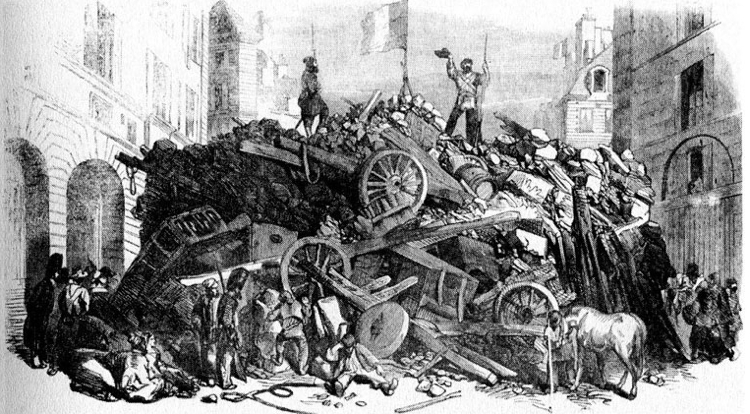

Barricades in February 1848↩

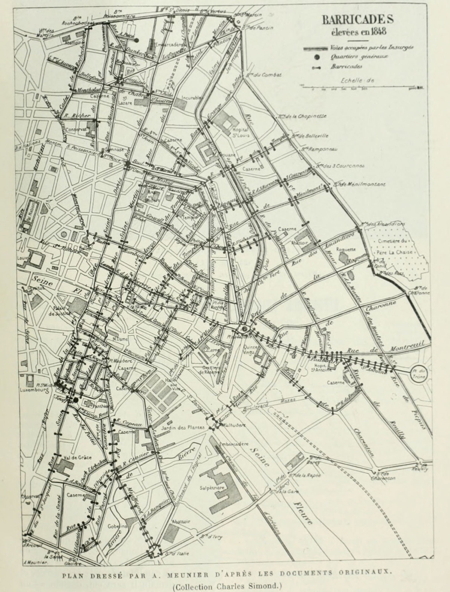

Barricades built across the streets had a history going back centuries and reached their classic form during the 1830 Revolution in Paris. They consisted of street paving stones, old furniture, fence railings, overturned carriages, which were tied together with iron chains. In some parts of Paris they were constructed every couple of hundred of metres (see the map below of June 1848) and were a severe impediment to the movement of troops in the city. In February the French troops were disorganised and divided in their loyalties. They were eventually defeated by the barricade builders. This was not the case in June when new tactics were adopted and artillery used to destroy the barricades.

[A Barricade in the rue Saint-Martin]

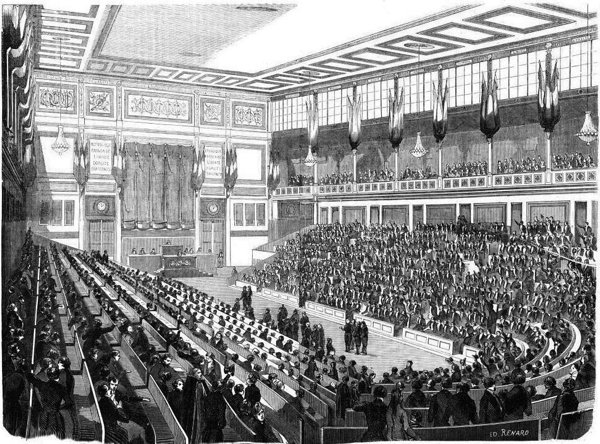

The National Assembly (Palais Bourbon)↩

[The exterior of the National Assembly]

[Interior of Assemblée Nationale in 1848. It seated 900 Deputies.]

The Luxembourg Palace and the National Workshops↩

The radical socialists who were members of the Provisional Government wanted to put into practice the ideas of Victor Considerant and Louis Blanc to “organise work” into worker controlled groups where all workers would be granted “the right to a job” and would be paid an equal wage and profits would be abolished. The Provisional Government set up Louis Blanc to “investigate” the matter in a “Government Commission for the Workers”. He was not set up as the new “Minister for Labour” or the “minister for Progress” (which was Considerant’s idea). Blanc with the help of “Albert” took over the Luxembourg Palace (the seat of the old Chamber of Peers) to begin implementing the National Workshops which would provide paid employment for any and all unemployed workers. As the number of unemployed seeking government paid relief grew the economic burden became too great and, under Bastiat’s strong urging in the Finance Committee, the decision was taken in late May to abolish the workshops. Supporters of the national Workshops organised protest marches on June 22 thus triggering the “June Days” uprising (and another period of barricade building) which was bloodily put down by the Army under General Cavaignac.

[Louis Blanc, the head of the Luxembourg Commission for Labour]

[The Luxembourg Palace and Gardens]

[Citizens reading wall posters for news]

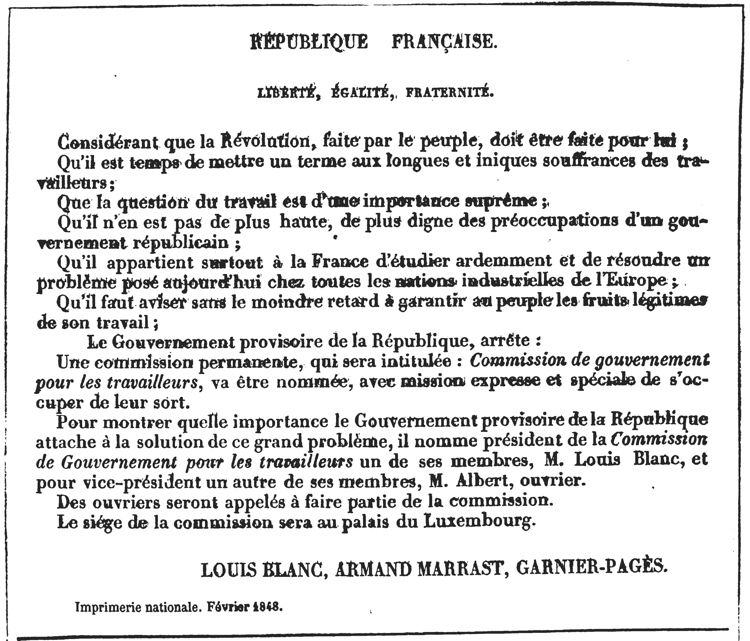

[A wall poster announcing the formation of the National Workshops in Feb. 1848]

[The SemiCircle of Famous French Politicians in the Luxembourg Palace]

[Turgot the Free Trader and Colbert the Mercantilist]

[A meeting of workers at the Luxembourg Commission]

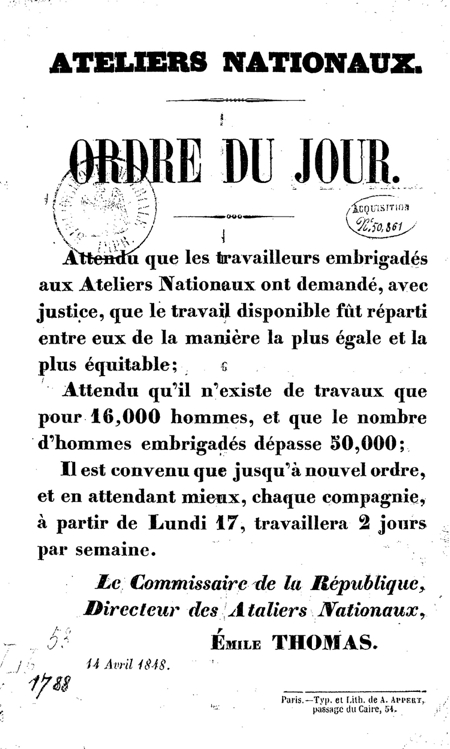

[A wall poster announcing a cut back in hours paid because too many workers were claiming payments which was bankrupting the new government.]

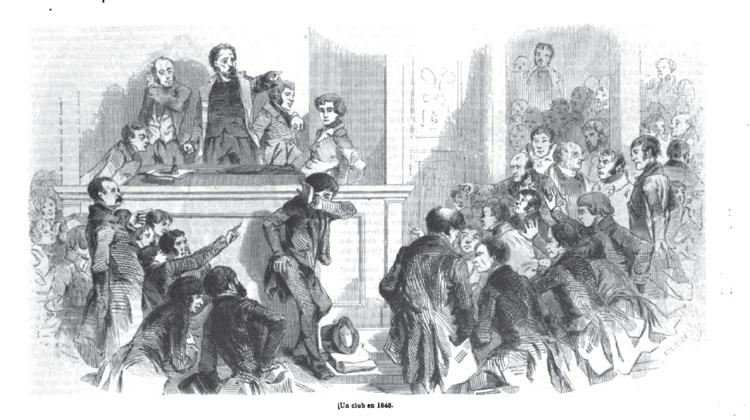

Political Clubs↩

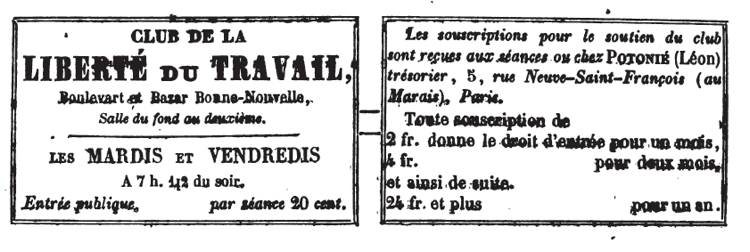

When censorship collapsed in late February with the fall of Louis Philippe’s régime there was complete freedom of speech and association for the first time in several decades. Various groups took advantage of this to set up political clubs and publish magazine to espouse their points of view. The economists set up their own club called “The Club for the Freedom of Working” (liberté du travail) (“Club Lib” for short) to directly counter Louis Blanc’s club which supported the “right to a job” (liberté au travail).

[Entry Ticket to the Club Lib]

[A debate in one of the Political Clubs]

FB’s Revolutionary Newspapers↩

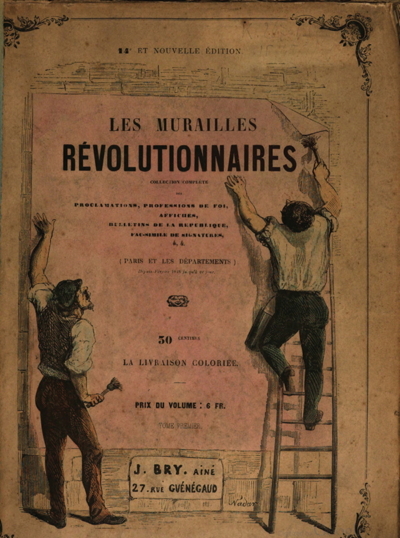

A common way to disseminate information was by means of wall posters which were plastered all over the city.

[Putting up Wall Posters]

[The title page of the first issue of FB’s revolutionary street paper “Jacques Bonhomme”]

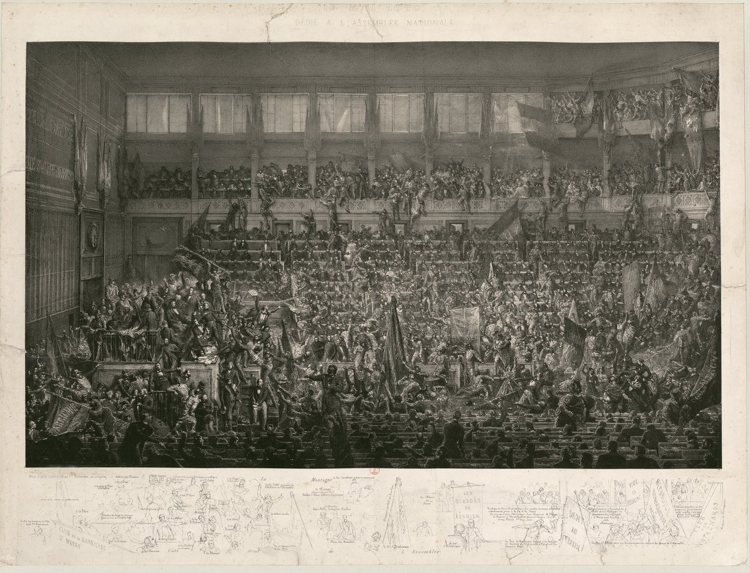

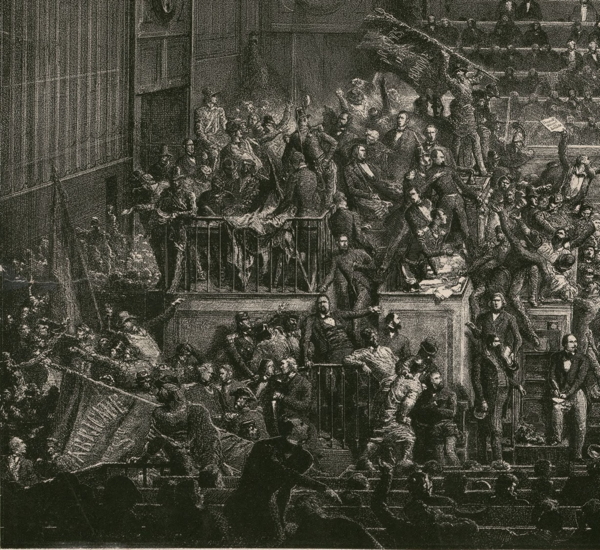

Invasion of the National Assembly in May 1848↩

A group of Louis Blanc’s supporters were disappointed at how badly the socialist did in the April election that they decided to invade the National Asembly during one of its sessions and force the Provisional Government to resign and to appoint more socialist ministers. It is unclear how much support Blanc gave to this act but he was carried around the Chamber on the shoulders of his supporters. They were eventually arrested and expelled from the Chamber. Later Bastiat defended Blanc from having his parliamentary privileges revoked so he could be arrested and charged. He lost and Blanc was forced to go into exile to England.

[The invasion of the National Assembly on 15 May 1848 by Political Clubs and others supporting Louis Blanc and the National Workshops program]

[Louis Blanc’s supporters seizing control of the Speaker’s rostrum]

[Louis Blanc being carried on the shoulders of his supporters]

Street Barricades during the June Days↩

Bastiat, Molinari and other colleagues started a second revolutionary street magazine in June to hand out to the workers in the streets. They got caught up in the crossfire when the soldiers moved to put down the revolt and remove the barricades.

[A Map showing the scores of barricades built across Paris]

[A Barricade on the rue Saint-Maur]

[Troops massing to destroy the barricades on rue Sainte-Catherine]

ACT IV: RESOLUTION - FROM JUNE 1848 TO DEC. 1850↩

After the June rioting Bastiat’s health continued to decline (I believe he was suffering from throat cancer which would kill him in Dec. 1850). He continued to fight against socialism and interventionism in the Chamber and in a series of a dozen or so anti-socialist pamphlets which were published by Guillaumin. He also continued work on writing his economic treatise, Economic Harmonies, he participated in an important international Peace Congress which was held in Paris in August 1849, and also wrote three important works on Free Credit (in an acrimonious debate with the left-anarchist Proudhon), What is Seen and What is Not Seen, and The Law.

During this period he received help from Madame Hortense Cheuvreux who made available to him the use of a hunting lodge in the woods to the west of Paris so he could have the peace and quiet he needed to write. There is also the possibility that in late 1849, following the Peace Congress, he went on a secret mission to London on behalf of a faction within the French government to sound out, through his friend Richard Cobden, the chances of the English government agreeing to cuts in military spending.

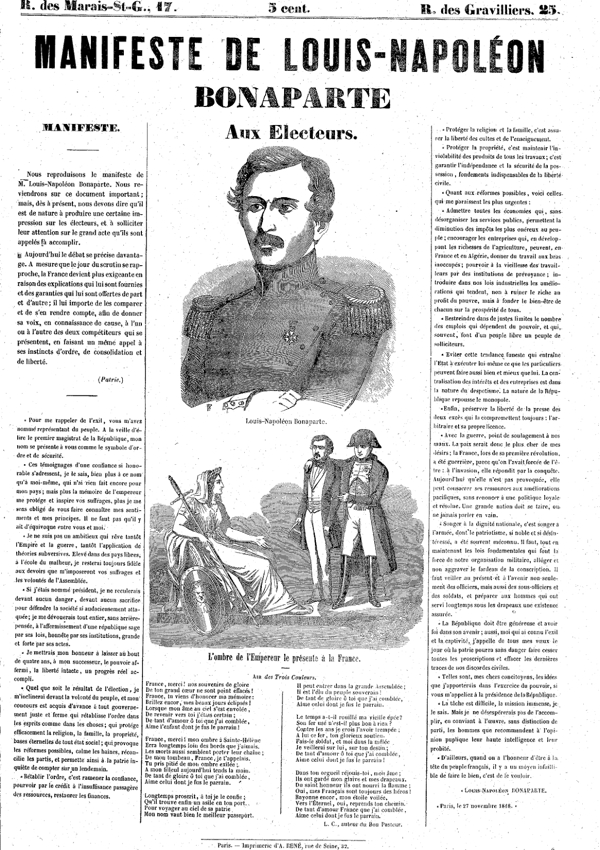

Bastiat and his colleagues were very worried about the future plans of Louis Napoléon Bonaparte, the nephew of Emperor Napoléon, who got elected to the Camber in June 1848 and then President of the Republic in December 1848. He seemed to combine political popularism, militarism, and economic interventionism much as his uncle had done 40 years previously. Although Bastiat died before Louis Napoléon seized power in a coup d’état in December 1851 he probably suspected what lay ahead as he and his colleagues began shifting gear in 1849 to challenge the new “socialism from above” (of Bonapart’s bureaucratic interventionism) now that “socialism from below” of Louis Blanc and the radical “Montagnard” movement had been defeated by the declaration of martial law and the crackdown on freedom of speech and association by the police.

The Butard Hunting Lodge↩

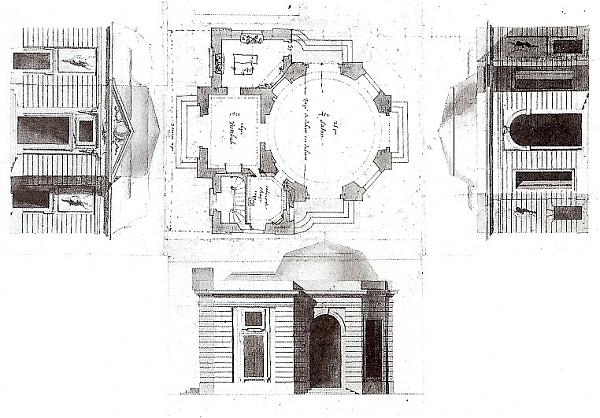

[The Butard Hunting Lodge outside Paris where FB wrote Economic Harmonies]

[The plan of the Lodge]

[The main Salon]

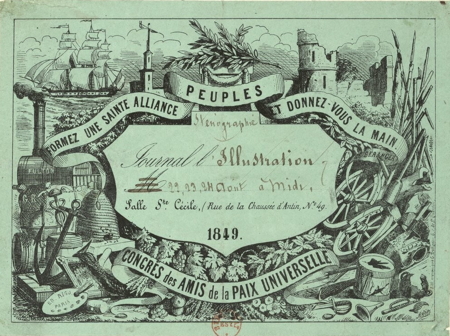

The Friends of Peace Congress↩

[Entry ticket for the Friends of Peace Congress, Aug. 1849]

[Victor Hugo, the President of the Peace Congress meeting]

[Richard Cobden, one of the key speakers]

[Victor Hugo opening the Peace Congress in Saint-Cecile Hall]

[Members of the English delegation to the Congress]

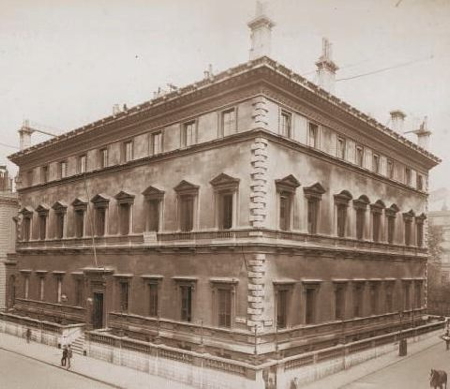

FB’s Secret Mission to visit Cobden in London↩

[The Reform Club where FB met with Richard Cobden to discuss disarmament]

[The Upper Level of the Reform Club]

Louis Napoleon is elected President↩

[An election poster in Nov. 1848]

FB Leaving Paris for the Last Time - Political graffiti↩

[The “Prince-President” Louis Napoleon was elected President of the Second Republic in Dec. 1848]

[A Cartoon of Napoleon III as Budget-Eating Vulture]

Coda: The Aftermath↩

In 7 years the unknown provincial 42 year old magistrate who had a hobby of reading economics became one of the most brilliant economic journalists the world has ever seen, help start and ran the French Free Trade movement, participated in a Revolution, got elected to the Chamber and became a strong voice within it for lower taxes and balanced budgets, wrote a string of important pamphlets on economic and political theory, and began work on a multi-volume treatise on social theory which he was unable to complete before he died at the age of 49.

The years immediately after his death appeared to be bleak for free market liberals like himself:

- the push for free trade had been defeated in the summer of 1847;

- the political and intellectual force of socialism appeared in early 1848 and was stronger than the liberals had anticipated;

- another power-hungry and interventionist Bonaparte had become head of the French state in December 1848;

- one of his promising younger colleagues, Alcide Fonteyraud, died suddenly in the cholera epidemic which swept France in the summer of 1849;

- he died not living long enough to finish his magnum opus;

- the brilliant editor and his friend on the barricade, Charles Coquelin, dropped dead from a heart attack in mid–1852 while working on the next big project the Guilllaumin network had taken up, the Dictionnaire de l’économie politique, which was designed to counter the new threat of “socialism from above”;

- and his younger colleague and friend Gustave de Molinari left Paris to go into voluntary exile rather than live under Napoléon III.

The group pf classical liberal economists in Paris had truly been decimated between 1849 and 1852.

Nevertheless, the work of his colleague Michel Chevalier within Napoléon III’s regime eventually resulted in a free trade treaty with England in January 1860, signed by his dear friend Richard Cobden. Bastiat himself would eventually get some recognition in 1878 when his friends raised enough money to have one of the leading sculptors in France design and build a fitting monument to his life and work which was erected in the square of his home town of Mugron. The statue was partly made of bronze and this bronze-work was seized by the Nazis in 1942 and melted down to make munitions as the scarcity of resources began to weaken the German war effort. This was a considerable irony given Bastiat’s great hostility to war and his efforts to build a peace movement.

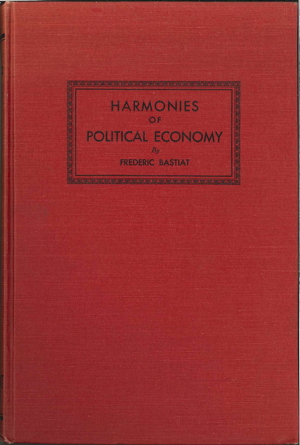

Although long forgotten in his own country, Bastiat’s work was discovered by some Americans who were opposed to the policies of President Roosevelt in the 1930s and WW2. The newspaper publisher R.C. Hoiles in Santa Ana, California used the printing presses of his newspaper to reprint an old English translation of Bastiat’s two most important works, the Economic Sophisms and Economic Harmonies in very bright red covers - thus introducing his work to the new generation of free market economists which appeared after WW2.

The Signing of the Anglo-French Free Trade Treaty in 1860↩

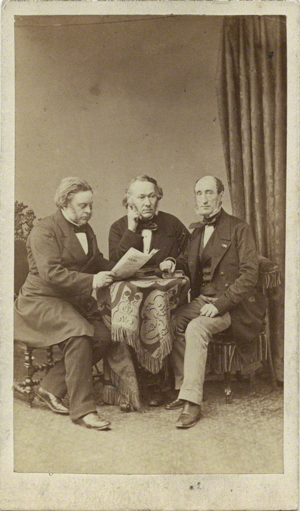

[John Bright, Richard Cobden, and Michel Chealier in 1860]

Erecting a Statue of FB in Mugron 1878↩

[The Statue for Bastiat in Mugron 1878]

Melting down the bronze to make munitions in 1940s↩

[A French foundry in the 1940s]

[A German tank factory in WW2]

The Rediscovery of Bastiat in 1940s California↩

[R.C. Hoiles takes over the Santa Ana Register and prints new editions of Bastiat’s works in a bright red cover]

[Printing Presses from the 1940s]

[The covers of the new American edition of Bastiat’s main works (1944)]