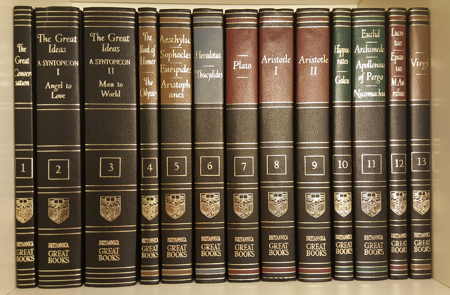

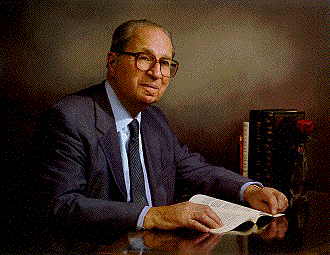

For over twenty years I have been working on making “the great books of liberty” (or “GBL”) accessible and more widely known . These GBL are a subset of the larger “great books” program pioneered by the University of Chicago under the direction of Mortimer Adler (1902-2001) back in the 1950s. Like many people growing up in the 1960s and 1970s our school library had the distinctive custom-made shelf unit which housed the collection of 54 volumes of “the Great Books of the Western World” which one usually bought as a set along with its three companion volumes which tried to make some sense of the collection for the ordinary reader.

These “Introductory Volumes” included a volume on “The Great Conversation” and two volumes on “The Great Ideas: A Syntopicon”, which was a rather awkward neo-Latin word for a “collection of topics”.1

After regular sales produced very poor results in the beginning, the publisher Encyclopedia Britannica employed experienced door-to-door salesmen to sell the set as they would any other “encyclopedia” designed for the home market. This resulted in the sale of millions of the sets, although we have no data about how many of these volumes ever got read by the presumably suburban purchasers.

See these Wikipedia entries for details:

– Great Books of the Western World – Wikipedia

– A Syntopicon – Wikipedia

– Great Conversation – Wikipedia

– and a cutdown version of only 10 volumes: Gateway to the Great Books – Wikipedia

Mortimer Adler’s 102 Great Ideas

Adler thought he could identify 102 “Great Ideas” on which he wrote short introductory essays to the very detailed list of specific pages in “the great books” in the collection. In 1992 Adler updated his introductions which was republished as The Great Ideas: a Lexicon of Western Thought (1992) along with another volume, Mortimer Adler: “The Great Conversation Revisited,” in The Great Conversation: A Peoples Guide to Great Books of the Western World, (Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., Chicago, 1990).

These “102” ideas were:

Volume I: Angel, Animal, Aristocracy, Art, Astronomy, Beauty, Being, Cause, Chance, Change, Citizen, Constitution, Courage, Custom and Convention, Definition, Democracy, Desire, Dialectic, Duty, Education, Element, Emotion, Eternity, Evolution, Experience, Family, Fate, Form, God, Good and Evil, Government, Habit, Happiness, History, Honor, Hypothesis, Idea, Immortality, Induction, Infinity, Judgment, Justice, Knowledge, Labor, Language, Law, Liberty, Life and Death, Logic, and Love.

Volume II: Man, Mathematics, Matter, Mechanics, Medicine, Memory and Imagination, Metaphysics, Mind, Monarchy, Nature, Necessity and Contingency, Oligarchy, One and Many, Opinion, Opposition, Philosophy, Physics, Pleasure and Pain, Poetry, Principle, Progress, Prophecy, Prudence, Punishment, Quality, Quantity, Reasoning, Relation, Religion, Revolution, Rhetoric, Same and Other, Science, Sense, Sign and Symbol, Sin, Slavery, Soul, Space, State, Temperance, Theology, Time, Truth, Tyranny and Despotism, Universal and Particular, Virtue and Vice, War and Peace, Wealth, Will, Wisdom, and World.

The ideas of individual liberty and constitutional government were important to Adler as the above lists indicate. For example, there are entries on Aristocracy, Constitution, Democracy, Government, Labor, Law, Liberty, Monarchy, Oligarchy, Revolution, Slavery, State, Tyranny and Despotism, War and Peace, and Wealth. He would also write other books in which the idea of freedom or liberty would be given a more prominent position, such as The Idea of Freedom (1958); Six Great Ideas (1984) which were Truth, Goodness, Beauty, Liberty, Equality, and Justice; and We hold these truths : Understanding the Ideas and Ideals of the Constitution (1987).2

I have put online the essays and “links” or references to the texts dealing with Government and Liberty as examples of the extraordinary industry which Adler and his editorial assistants gave to this enormous project. All this or course in the pre-computer era.

His original list of 102 “great ideas” is an eclectic and very idiosyncratic mixture of ideas and concepts which were, on the one hand, an heroic attempt to organise a mass of material but, on the other hand, one which I think fails to do justice to the diversity of thinking and creative activity which is the hallmark of the several thousands of years old “civilisation” or “tradition”, “western” or otherwise.

Adler and the Encyclopedia Britannica publishers which backed the project were criticized for their many omissions, such as women authors and “people of colour” from the Left (especially during the 1970s), as well as for their emphasis on “ideas” rather than the style or form of the works (especially of art and literature). It was also criticized from the Right, such as their erstwhile collaborator, Pierre Goodrich, the founder of Liberty Fund, who had his own idea of the “great books” which placed a much great emphasis on individual liberty, limited government, and free markets than Adler and his colleagues did. For instance, the only economic ”ideas” Adler included in his list were “Labor” and “Wealth” but not “Markets,” “Private Property,” “Cooperation,” “Taxation,” or “Coercion”. There is also no entry for “Individual” or “Individualism” which I believe is a key concept which emerged out of the western tradition.

Being both a business and an intellectual entrepreneur, Goodrich solved the problem by setting up his own foundation in 1960 in competition with Adler’s group at the University of Chicago to promote his own vision of “the great books of liberty.” It was to put online Goodrich’s vision of the GBL that I was originally employed by LF some 20 years ago. The results of my efforts can be seen here:

- the Introduction to The Great Books of Liberty,” *The Online Library of Liberty and

- Some Provocative Pairings of Texts about Liberty and Power

When the new building for Liberty Fund was being designed the Board wanted to pay homage to Goodrich’s vision of the GBL by having the names of the 100 authors on his list prominently displayed on the exterior of the building, as this photo shows.

[The facade of LF’s new building in Indianapolis, IN.]

Most unfortunately, the end result is largely a failure as the names are barely visible from the main road (even when the sunlight is shining at the right angle), and probably never read by the drivers of the cars as they rush by at high speed. The greatest failing of their attempt is that Goodrich had a teleology in mind, as he believed all these authors and great books were leading up to the writing of the Declaration of Independence in 1776, but this end point and purpose is mysteriously hidden from view around a corner of the building. It is not visible from the street and is so well hidden and obscured that it is barely visible through a window from one side room which is not used very often.

The Contested Nature of the Great Books

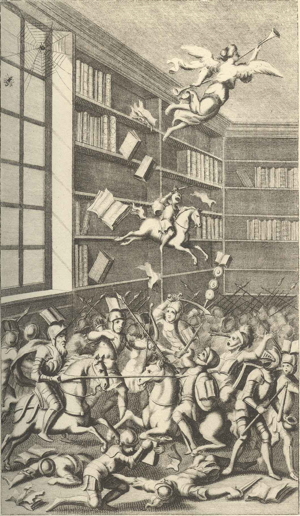

[Jonathan Swift, The Battle of the Books (1704)]

If the gender or ethnicity of the authors, or the feature of a work which defines its “greatness” (the ideas it contains, or its form and style) is a matter of disagreement, I would add my own criticism. This is the idea that “great books” seem to emerge as a whole out of the surrounding intellectual sea in which they were given birth. My view is that what we have now come to regard as “great books” were not deemed such at the time of their appearance, that they came out of or produced hotly contested debates among many authors and groups, in other words they were “contested” at the time and continued to be be “contested” in the present as the debates about the gender and ethnicity of the authors and the general “wokeness” of their content clearly demonstrate.

I think the editors of the original collection were aware of this problem and attempted to deal with it as best they could. As they stated in the first volume on abc concerning what they termed “subordinate types of questions” (Preface to volume 1 of Syntopicon, pp. xxii-xxiii)

The question, *What books other than those published in this set contain important discussions of this ideas?* is answered, to some extent, by the Additional Readings listed in the chapter on each of the great ideas.

The question, *What is the history of the ideas, its various meanings, and the problems or controversies it has raised?* is answered, at least initially, by the Introduction to the chapter on each of the great ideas. Here as before, if the reader’s interest is aroused to further inquiry, the topics, the references under them, the passages in the great books referred to, and the books listed in the Additional Readings, provide the means for a fuller exploration of the idea, in varying degrees of thoroughness and ramification.

In the example I have provided, the Introductory essay on the idea of “Liberty”, one can see for oneself how well they have succeeded in doing this. I fear that sometimes the project becomes so bogged down in details and cross-references that this noble goal disappears from view.

Thus, in the spirit of Goodrich, I have drawn up my own list of “the great books”, a kind of competing “great books” list, in order to make the contested nature of their appearance and content more clearly visible to the contemporary reader. My list at present contains some 17 “pairings” of texts and I plan to expand this in due course. This approach I realize is easier to do with books which deal with questions about the liberty of the individual, the extent of the power of the state, the nature of property rights, and the free market, but I suspect a creative person interested in literature or art could do something similar with the “texts” they are most familiar with. There might be the conflict between “traditionalists” and “innovators” for example. I would love to teach in a broad “Great Books” course where experts in different disciplines could adopt a similar methodology. Furthermore, this approach is very much in the tradition of the original Adlerian approach which was to invoke the study of the Great Books as a continuation of “the great conversation” which has been going on in the west for centuries. By having our own “conversations” in the present about hotly contested “topics” we can continue this excellent approach to teaching and learning.

My list of “provocative pairings” of texts is now on the front page of my website) and contains the introduction which I include below. Wherever possible I include a copy of the text in its original language as I think it important to be able to read some of the texts in the language in which it was actually written, rather than just rely on translations. And since I am now living back in Australia, I have made an attenmpt to include wherever possible a domestic equivalent to show the universal nature of these debates and conversations.

Introduction

There are different schools of thought about what makes “the western tradition” “western”. One common perspective (advocated here) is to argue that it was in “the west” where ideas about the individual (including individual “natural rights”), limits to the political power of the ruler, the rule of law, freedom of speech and religion, and free markets (in fact the whole discipline of “economics”), were preconditions for the emergence of the industrial revolution (and the massive increase in wealth this made possible) and the institutions and practices of “liberal democracy” such as constitutional government.

However, the emergence of these ideas, institutions, and practices was not inevitable and was in fact hotly contested within “the west” itself, both ideologically (in print) and politically (i.e. by the use of violence). Ideologically, it seems extraordinary to me that “the” western tradition could produce two such contrasting thinkers such as Karl Marx and Herbert Spencer, for example. Thus I think that the best way to understand how the ideas and institutions now associated with “the west” emerged, is to see it as the result of a “dialogue” or “conversation” (and sometimes an outright “battle of the books” as Jonathan Swift described it) between opposing positions.

Politically, many of the iconic texts of “the western tradition” were burned and/or banned and their authors censored, imprisoned, tortured, and even executed by the Catholic Church and various governments. In other words, they were “indexed”. Thus, the struggle was not just an ideological one but also sometimes a violent political one since traditional ruling elites did not relinquish their power and privileges without episodes of violence, such as the Reformation and the Wars of Religion, the English Civil Wars and Revolution, and the revolutions that followed in North America, France, and across Europe in 1848. So it seems to me that the ideological disputes we can read in the texts need to be placed against the backdrop of political events, with the texts being seen as sometimes precursors to political change or reactions to previous political change.

My “Provocative Pairings” of some of the Texts

I suggest that an interesting way to read the “great books” of the western tradition is by pairing each one with a contemporary (or near contemporary) text which takes a different view. This approach works especially well with books on political, economic and social theory. See my paper on “The Conflicted Western Tradition: Some Provocative Pairings of Texts about Liberty and Power” for the Association of Core Texts and Courses annual conference, April 2019, Santa Fe, NM., where I explore this approach in more detail.

Below is a list of some “great” (i.e. influential) books in the western tradition about political power which oppose the idea of individual liberty, free markets, and limited government and which I have paired with a contemporary “pro-liberty” text. Wherever possible I also link to the original language version of the texts as translations can be of variable quality (see the specific book page for details); and in a couple of instances I also include an Australian counterpart if it is available.

See the list here.

I am planning to write a more detailed Study Guide for my list of Provocative Pairings and put it online in due course.

- The Great Ideas. A Syntopicon of Great Books of the Western World. M. J. Adler, Editor in Chief. William Gorman, General Editor (Encyclopaedia Britannica: Chicago, [1952). [↩]

- Mortimer Adler, The Idea of Freedom : a Dialectical Examination of the Conceptions of Freedom (Garden City, New York : Doubleday & Company, Inc., 1958); Six Great Ideas: Truth, Goodness, and Beauty – Ideas we Judge By. Liberty, Equality, and Justice – Ideas we Act On (New York: Collier Macmillan, 1984).; and We hold these truths : Understanding the Ideas and Ideals of the Constitution (New York : Macmillan, 1987). [↩]