Note: This post is a continuation of an earlier one on the scandalous neglect of classical liberal sociology (especially classical liberal class analysis). See “The Scandalous Neglect of Classical Liberal Sociology” (30 May, 2021).

Note 2: A longer version of this was written for my website (with lengthy quotes).

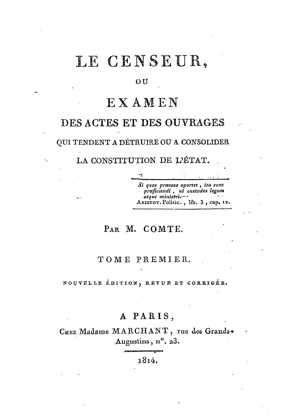

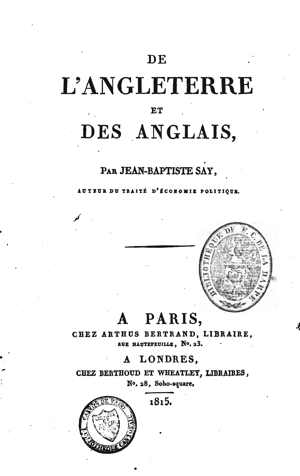

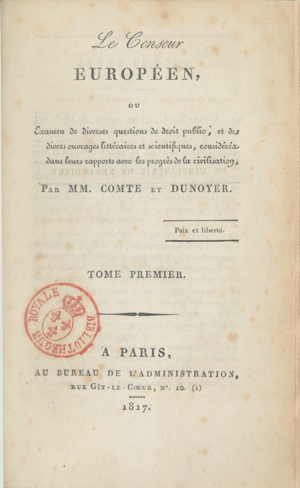

The writings of the economist Jean-Baptiste Say (1767-1832) had a profound impact on the thinking of Charles Comte (1782-1837) and Charles Dunoyer (1786-1862) in the years 1814 to 1817. We can trace this impact in the essays they wrote for their journals Le Censeur (July 1814 – Sept. 1815) and Le Censeur européen (Jan. 1817 – Apr. 1819).1

Comte and Dunoyer were trained as lawyers and their earliest forays into politics showed them to be fairly standard defenders of “political liberalism” such as freedom of speech and association, constitutional limits on state power, and opposition to “despotism” whether monarchical or imperial (i.e. Napoleonic) in form. In the pages of their journals we can see their intellectual transformation during this period into advocates of a new kind of “social” and “economic” liberalism. This transition occurred under the influence of their reading of the sociologist Saint-Simon, the historian Augustin Thierry (who later became an editorial assistant to Comte and Dunoyer), the royalist historian of the French monarchy and aristocracy, Montlosier, the liberal political theorist Benjamin Constant, and then most importantly the industrialist and political economist Jean-Baptiste Say, which we can trace in their book reviews.

Say’s economic theory in particular provided them with a much larger framework for their liberalism which would now include a theory of the antagonism or struggle (la lutte) between the productive “industrial” class and the unproductive parasitical “ruling” class, as well as a new “industrialist” theory of history which explained how societies moved through different stages based upon their very different “means of production” and the different forms the conflict between the “industrial” and the “ruling” class took in these different stages of economic development. Among these stages, they were particularly interested in slavery, which they regarded as the archetypal form of class rule and exploitation, and the newest form of rule and exploitation by a bureaucratic class of government officials which had appeared under Napoleon and which seemed to be kind of class rule which wold govern France in the near future.

That these two liberals developed quite sophisticated ideas about class conflict and the transition of societies from one economic stage to another some thirty years before Marx did is striking and needs to be better known and appreciated by scholars.

What made their form of liberalism unique, as well as those other French liberals who followed in their footsteps (such as Bastiat and Molinari), was this combination of political liberalism (limited government and rule of law), economic liberalism (free markets and laissez-faire policies), and social (or sociological) liberalism (class analysis, the evolution of societies thorough economic stages). The combination of these three different dimensions to their liberal theory made their version of liberalism a very radical, rich, and interesting one, one which I believe sets them above their contemporary English counterparts.2

In fact, what Say’s economic ideas did was to show them the interconnectedness of the political, the social, and the moral worlds in a way which even the ideas of Adam Smith did not, at least as explicitly. (They do if you view his Theory of Moral Sentiments (1759) and the Wealth of Nations (1776) together, which at the time was not usually done.) We can see this very clearly in the first review of his Treatise which was supposed to appear in September 1815 which was confiscated by the police.

The first of Say’s works to be reviewed (the author signed as “X” and was probably Comte) was his official report for the French government on the economic impact of the wars on the English economy, De l’Angleterre et des Anglais (On England and the English) in volume 6 of Le Censeur (1 June, 1815). The reviewer thought that Say’s ideas were so important that the journal would soon publish a review of Say’s Treatise. [See the bibliography of Say’s works here ; and Say, De l’Angleterre et les Anglais (Paris: Arthus Bertrad, 1815). [ facs. PDF ] Comte and Dunoyer were still asserting the seminal importance of Say’s work in 1819-20 when their journal became a daily news paper, also called

Le Censeur européen. By then a fourth edition of Say’s Treatise had been published which they were describing as “without contradiction one of the most important books which have been published since the beginning of the 19th century. [Le Censeur européen, 14 October, 1819, quoted in Harpaz, pp. 128-29, fn 5.]

Next to be reviewed, also by Comte, was Say’s major Treatise on Political Economy, the 1st edition of which was published in 1803 (but not reviewed in C or CE), the 2nd edition of which appeared in 1815 and reviewed in volume 7 of Le Censeur which should have appeared in September 1815. However, that issue of their magazine was seized by the police and the journal was forced to close for a period of 15 months while the two lawyers hid from the police and battled the censors in the courts. Some copies of this issue were saved so we have access to it. [See the review by Comte, CR “Traité d’économie politique, ou simple exposition de la manière dont se forment, se distribuent et se consomment les richesses, par M. J.B. Say” (C, T.7, 6 Sept. 1815), pp. 43-77) in HTML (to come) and facs. PDF; and Say’s Traité: the facs. PDF of the 3rd ed. [vol.1 and vol.2 ] and the HTML and facs. PDF of the 6th ed. of 1841; and the rather old (1821) English trans. of the 4th ed. of 1819 by Princeps in HTML and facs. PDF – vol.1 and vol.2.]

As he stated on the opening page:

A l’affût comme nous le sommes de toutes les idées, de tous les ouvrages qui peuvent exercer une influence favorable sur le sort [44] de la nation, le *Traité d’économie politique* de M. Say ne pouvait nous échapper. Nous l’avons lu avec l’attention qu’il mérite, et nous pouvons affirmer que nous connaissons peu de livres qui renferment autant de notions saines, autant de vues immédiatement applicables et utiles. Nous le déclarons, cet ouvrage nous paraît avoir complètement tire l’économie politique de l’empire des opinions systématiques. Il fait apercevoir, il vous oblige d’observer des faits qui arrivent journellement, et qui n’en sont pas mieux connus pour cela; il montre la relation de ces faits entr’eux, celle qu’ils ont avec leurs causes, avec leurs résultats; et ces faits sont les plus intéressans pour l’homme, puisque ce sont ceux qui ont rapport à sa fortune, à son existence, aux biens qui peuvent la rendre douce …

As we are on the lookout for all those ideas and all those works which can have a favourable influence on the fate of the nation, M. Say’s *Treatise on Political Economy* could not escape our attention. We have read it with the attention it deserves and we can assure the reader that we know of very few books which contain as many good ideas, as many opinions which are immediately practicable and useful. We believe that this work appears to us to have completely established (the science/discipline) of political economy upon the foundation of systematic thinking. It makes us see things (les faits), it forces us to observe things which happen every day, things that are not well understood even though they do happen every day; it shows us the interconnectedness of (these) things, (the connection) they have to their causes and to their consequences; and these things (faits) are the most interesting things for mankind because they have a connection to our wealth, our very existence, and the goods which can make (our) lives better (douce) …

As he quotes passage after passage from Say we can see him thinking through the implications of some of Say’s most important ideas, especially that all activities which create a value of some kind thereby create wealth, not just agriculture (the 18thC Physiocratic notion) but also commerce and “industry” very broadly defined; that both parties to a voluntary exchange benefit from that exchange; and that so much of what the government does either destroys wealth, prevents wealth from being created, or transfers wealth from one group to another.

Comte and Dunoyer reopened in January 1817 with a new title Le Censeur européen and another review by Comte of Say’s Treatise, this time of the revised 3rd edition which had appeared in the interim. Part 1 of the review appeared in volume 1 (Jan. 1817) and Part 2 in the following issue Volume 2 ( March, 1817). [See, Comte, CR “Traité d’économie politique, ou simple exposition de la manière dont se forment, se distribuent et se consomment les richesses, 3e. édit., par M. Jean-Baptiste Say,” (CE T.1, 19 December 1816, p. 159-227) in HTML (to come) and facs. PDF; and [CC?], CR “Traité d’économie politique, ou simple exposition de la manière dont se forment, se distribuent et se consomment les richesses, 3e. édit., par M. Jean-Baptiste Say,” (CE, T.2, 27 March 1817), pp. 169-221, in HTML and facs. PDF.]

One line of Say’s thought which struck them was the idea that political economy in Say’s hands had become a true science for the first time (even beating out Adam Smith) and that he had revealed “les lois constantes et invariables” (the constant and unchanging laws) which governed not only the economic world but the much broader social and political world. So much of the world’s problems could be attributed to theorists and politicians trying to run the world according to “les règles de conduite” (rules of conduct) which they had spun out of their imaginations instead of following economic laws which could be discovered by empirical observation of how people behaved in the real world.

As examples of policies pursued by governments which violated these unbreakable economic laws the reviewer singles out excessive government expenditure and the massive taxation and the issuing of paper money required to fund these policies, the policy of pursuing a “favourable” balance of trade by using tariffs and subsidies to “protect” domestic producers, and (in the previous review article) the idea that the possession of colonies would increase national prosperity. Added to these problems there was also the problems caused by ignorance of what activities truly created wealth as people were mislead by “false systems” of economic thought, such as the greater productivity made possible by the use of machines, the contribution to wealth generation made by manufacturing industry in general, and the important role played by “la classes des entrepreneurs” (the class of entrepreneurs) in bringing all these improvement about.

Only the teaching of a more scientific approach to political economy would disabuse people of these false economic ideas. The reviewer bemoaned the fact that the teaching of economics in France was far behind that of other countries such as Germany, Britain, Russia, and even Spain. It should be noted that J.B. Say would eventually be allowed to give lectures at the private Athénée in Paris (1816-1819) and then made a professor of political economy at the prestigious Collège de France in 1831 where he taught briefly before his death the following year.

In the second part of the review of the 3rd edition of Say’s Treatise (March 1817) the reviewer discussed Say’s ideas about the nature of consumption, especially the difference between “productive” and “unproductive” consumption, and how this idea could be applied to government expenditure and “consumption”. The radical implication of Say’s ideas was that most (perhaps all) government expenditure was “unproductive” and thus a drain on wealth creation by the “productive and industrious class” with important flow on effects on the broader society or “civilisation” as he termed it. Thus, rather than facilitating the creation of wealth by others, or engaging in the production of wealth itself, the government became instead “un gouvernement dissipateur” (a wasteful government) [p. 196] or resembled “un voleur” (a thief) [p. 199].

The reviewer then turned to discussing Say’s ideas which added to the traditional “le doux commerce” (the softening effect of commerce) thesis by including far more than just commerce in his analysis of the impact of economics on culture, or as it was termed at that time “la morale” (morality) and “la civilisation”. What was important here were the ideas of the mutually beneficial nature of exchange, the cooperation brought about by the division of labour, and how these brought people closer together instead of encouraging them to think of each other as potential enemies.

A review, this time by Dunoyer, of a third work by Say, Petit volume contenant quelques aperçus des hommes et de la société (A Small Volume containing some Thoughts on Mankind and Society) , was published also in two parts, in volume 6 (Sept., 1817) [PDF] and volume 7 (March, 1818) [PDF]. The first “review” was quite short and consisted mostly of short quotes from the book. The actual review would come in the following edition of the journal as the first edition of the book had sold out and a second revised edition would be available very soon.

Dunoyer was very taken with Say’s book, considering it to be filled with astute insights, provocative ideas, and expressed in a manner which would encourage the reader to explore more of the discipline of political economy. He also used the review as an opportunity for him to express himself very frankly about what he thought the proper function of governments should be (very little other than protecting the life, liberty and property of its citizens), how best to go about changing the current system of corruption and exploitation (enlightening the “dupes” who allowed themselves to be deceived by conniving politicians and their hangers-on), and the role of a free press in “tearing off the mask” of those who ruled and exposing them in their complete political “nakedness” for all to see. I provide here three lengthy quotes from the review which illustrate the quite remarkable and explicit views expressed by Dunoyer in this piece. Perhaps he thought the censors would not read a review of a book like this and he could be more open and forthright in expressing his views.

After carefully reviewing Say’s books in their journal Comte and Dunoyer then applied what they had learned from him in a series of original and path-breaking articles of their own in which they developed their ideas on class conflict and the economic progression of societies in much greater detail. These essays are included in my Anthology of their writings and they would provide the foundation for the much more extensive and detailed development of their “industrialist theory of history” in the multi-volume books they would publish over the next 20 (Comte) or 30 (Dunoyer) years.

These important essays were the following and are available online:3

- Comte, “Considerations sur l’état moral de la nation française, et sur les causes de l’instabilité de ses institutions” (Thoughts on the Moral State of the French Nation and on the Causes of the Instability of its Institutions) (CE, T.1, Jan. 1817. pp. 1-92) – HTML and facs. PDF.

- Comte, “De l’organisation sociale considérée dans ses rapports avec les moyens de subsistance des peuples” (On Social Organisation and its Connection with the Way the People earn their Living) (CE, T2, Mar. 1817, pp. 1-66.) – HTML and facs. PDF.]

- Dunoyer, “Considérations sur l’état présent de l’Europe, sur les dangers de cet état, et sur les moyens d’en sortir” (Thoughts on the Present State of Europe, the Dangers it faces, and the Means of Escaping them) (CE, T1, Mar. 1817, pp. 1-92.) – HTML and facs. PDF.]

- Comte, “De la multiplication des pauvres, des gens à places, et des gens à pensions” (On the Increase in Numbers of the Poor, People with Government Jobs, and People who live off Government Pensions) (CE, T7, Mar. 1818, pp. 1-79.) – HTML and facs. PDF.]

- Dunoyer, “De l’influence qu’exercent sur le gouvernement les salaires attachés à l’exercice des fonctions publiques” (On the Influence exerted on the Government by those who earn Salaries by carrying out Public Functions) (CE, T11, Feb. 1819, pp. 75-118.) – HTML and facs. PDF.]

I will discuss these articles in more detail in future post.

These articles in turn provided the foundation for the much more detailed elaboration of these ideas in a series of multi-volume books which the two wrote over the coming decades. Comte completed 2 works before he died in 1837:4

- Traité de législation, ou exposition des lois générales suivant lesquelles les peuples prospèrent, dépérissent ou restent stationnaire (A Treatise on Legislation, or a Discussion of the General Laws which enable Nations to prosper, decline, or remain in a stationary state, 4 vols. (1827) – HTML (to come) and facs. PDF of vol.1; vol.2; vol.3; and vol.4.

- Traité de la propriété (A Treatise on Property), 2 vols. (1834)- HTML (to come) and facs. PDF of vol.1 and vol.2.

And Charles Dunoyer 3 works which were really a series of expanded versions of the same initial concept:5

- L’Industrie et la morale considérées dans leurs rapports avec la liberté (Industry and Morality considered in their Relationship with Liberty) (1825)- HTML (to come) and facs. PDF.

- Nouveau traité d’économie sociale, ou simple exposition des causes sous l’influence desquelles les hommes parviennent à user de leurs forces avec le plus de LIBERTÉ, c’est-à-dire avec le plus FACILITÉ et de PUISSANCE (A New Treatise on Social Economy, or a simple description of the causes under whose influence mankind becomes able to use their powers with the greatest amount of Liberty, that is to say with the greatest ease and power) 2 vols. (1830)- HTML (to come) and facs. PDF of vol.1 and vol.2.

- De la liberté du travail, ou simple exposé des conditions dans lesquelles les force humaines s’exercent avec le plus de puissance (On the Liberty of Working, or a simple discussion of the conditions under which human energy can be exercised with the greatest power) (1845) – HTML (to come) and facs. PDF of vol.1; vol.2; and vol.3.

It is my intention to put these important works online in HTML so scholars can make better use of them. They have been online in facs. PDF format for over 10 years now as they (along with the works of Bastiat and Molinari) have been the core of my online library since its inception.

Bibliography

Comte, Charles, Traité de législation, ou exposition des lois générales suivant lesquelles les peuples prospèrent, dépérissent ou restent stationnaire, 4 vols. (Paris: A. Sautelet et Cie, 1827).

Comte, Charles, Traité de la propriété, 2 vols. (Paris: Chamerot, Ducollet, 1834).

Dunoyer, Charles, L’Industrie et la morale considérées dans leurs rapports avec la liberté (Paris: A. Sautelet et Cie, 1825).

Dunoyer, Charles, Nouveau traité d’économie sociale, ou simple exposition des causes sous l’influence desquelles les hommes parviennent à user de leurs forces avec le plus de LIBERTÉ, c’est-à-dire avec le plus FACILITÉ et de PUISSANCE (Paris: Sautelet et Mesnier, 1830), 2 vols.

Dunoyer, Charles, De la liberté du travail, ou simple exposé des conditions dans lesquelles les force humaines s’exercent avec le plus de puissance (Paris: Guillaumin, 1845).

Endnotes

- On the history of these journals see the three articles by Éphraïm Harpaz, “Le Censeur, Histoire d’un journal libéral,” Revue des sciences humaines, Octobre-Décembre 1958, 92, pp. 483-511; “Le Censeur européen, histoire d’un journal industrialiste,” Revue d’histoire économique et sociale, 1959, vol. 37, no. 2, pp. 185-218 and vol. 37, no. 3, pp. 328-57; and “Le Censeur européen: histoire d’un journal quotidien,” Revue des sciences humaines, 1964, pp. 113-116, pp. 137-259; which have been republished together in a book: Le Censeur. Le Censeur européen. Histoire d’un Journal libéral et industrialiste (Genève: Slatkine Reprints, 2000). [↩]

- On Comte’s and Dunoyer’s “industrialist theory of history” see my unpublished PhD “Class Analysis, Slavery and the Industrialist Theory of History in French Liberal Thought, 1814-1830: The Radical Liberalism of Charles Comte and Charles Dunoyer” (Cambridge, 1994) online here. [↩]

- On some of these articles see Mark Weinburg, “The Social Analysis of Three Early 19th Century French Liberals: Say, Comte, and Dunoyer,” Journal of Libertarian Studies, 1978, vol. 2, No. 1, pp. 45-63. Online. [↩]

- See the bibliography on Charles Comte for a complete list of his works. [↩]

- See the bibliography on Charles Dunoyer for a more complete list of his works. [↩]