“SOME THOUGHTS ON AN ‘AUSTRIAN THEORY OF FILM’:

IDEAS AND HUMAN ACTION IN A FILM ABOUT FRÉDÉRIC BASTIAT”

By David M. Hart

[Created: 5 August, 2019]

[Revised: 8 July, 2024] |

Abstract

This paper was originally written for the Libertarian Scholars Conference held in New York City in September 2019.

In this paper I explore some of the problems one faces in making a good movie of ideas (or any work of art for that matter) and why there are relatively few pro-liberty movies being made (I also have in mind the disaster which was the attempt to turn the sprawling novel Atlas Shrugged (1957) into a movie). Several years ago I wrote a screenplay about Frédéric Bastiat during the 1848 Revolution so I have thought long and hard about how one should go about making a film about ideas. My model was the very successful and very good movie by Warren Beatty “Reds” (1981) which won several Oscars but the events of 1917 were seen through the eyes of an American communist journalist. My movie about Bastiat, which I called “Broken Windows”, saw the events of 1847-1850 thought he eyes of a great libertarian thinker and politician.

The theoretical framework I use is a Misesian one in which I propose that there is an “Austrian theory of film” which is based on Mises’ theory of “human action.” To this I have added Bastiat’s own theory of “the seen” and “the unseen,” where ideas are “the unseen” and the actions people take based upon those ideas are “the seen.” I develop an outline of such a theory in my paper. As Mises stated in Human Action, "Action is preceded by thinking. Thinking is to deliberate beforehand over future action and to reflect afterwards upon past action. Thinking and acting are inseparable. Every action is always based on a definite idea about causal relations." Thus, I believe that ideas can be presented in films either directly (through speech) or indirectly by inference from the images and the “action” which one sees on the screen (both the traditional form of “action” in a movie, as well as in the “Austrian” sense). The "direct presentation of ideas" can be achieved via set speeches and in smaller private conversations. The "indirect presentation of ideas" can be achieved via static images, actions taken by the state and its agents, actions by individuals in the market, and most importantly, the character and motivation of the hero/protagonist.

I use the screenplay I wrote about Bastiat's activivities during the 1848 Revolution in Paris as a case study of this approach to making a film about idea, iu=in this case classical loberal ideas.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

- Introduction

- Some Personal Background

- The Problem of the Depiction of Individual and Economic Liberty in Films

- Introduction

- The Problem revisited: Atlas might have shrugged, but audiences did too

- The Problem of Filming a “Positive” vs. a “Negative” Depiction of Liberty, or “the Seen” and “the Unseen”

- Some Thoughts on Presenting Ideas in Film

- Introduction

- Some Good Movies of Ideas

- Examples of the Direct Expression of Ideas

- Ideas and Human Action in Film: Towards an Austrian Theory of Film/Cinema

- Mises on Ideas, Interests, and Human Action

- Helping the Viewer see the Connection between Ideas and Action: “Product Placement” and Visual Nudging

- Some More Thoughts on Presenting Ideas in Film: The “Broken Windows” Experiment

- Introduction

- How “Cinematic” was the life of Bastiat?

- How “Cinematic” was Paris and the Revolution of 1848?

- The Direct Expression of Ideas: Set Speeches

- The Direct Expression of Ideas: Private Conversations

- The Indirect Expression of Ideas: Static Images of State Power

- The Indirect Expression of Ideas: Showing the everyday violence of the State

- The Indirect Expression of Ideas: Showing the Violence used by the State during the Revolution 1848–49:

- The Indirect Expression of Ideas: Showing the everyday good things done by the Market

- The Indirect Expression of Ideas: Showing works of Art, Literature, and Music

- Other Opportunities for “Visual Nudging”

- Some Nerdy Stuff

- Introduction

- An Historian’s Angst and Guilt

- Save the Cat

- Recurring Images

- Fleeting references to historical figures

- The Soundtrack for the Movie

- Conclusion

- Appendix I: Mises on Ideas, Interests, and Action

- Appendix II: Some Notes on the Screenplay

- Striking Visuals

- Music

- Big Set Pieces

- My Fabrications in the Script

- Strange but True

- Bibliography and Filmography

- Those Mentioned in the Text

- My Favorite Political Films / Movies of Ideas

- Endnotes

Introduction↩

Some Personal Background

|

|

| Some broken windows | An itinerant glazier |

My screenplay of the life and thought of Frédéric Bastiat (1810-1850), naturally entitled “Broken Windows”, [1] is the product of 40 years of thinking about films historically, politically, and economically - in other words how they have been influenced by and used to depict ideas. From the time I saw Lewis Milestone’s great anti-war classic All Quiet on the Western Front (1930) on late night TV in Australia in the 1970s, [2] to seeing Andrzej Wajda’s powerful film Danton (1983) about the Terror during the French Revolution and Elem Klimov’s Come and See (1985) about Nazi atrocities in Byelorussia at the Cambridge Film Festival in the mid-1980s, and the reconstruction of Abel Gance’s monumental film Napoléon (1927, 1981 restored by Kevin Brownlow with a score by Carmine Coppola) with a full orchestral accompaniment at the Barbican in London, to working with Marty Zupan of the Institute for Human Studies to develop the “Liberty in Film and Fiction Summer Seminars” throughout the 1990s (the highlight I think of that period was showing Claude Berri’s marvelous films about property rights, Jean de Florette (1986) and its sequel Manon des Sources (1986), also set in the south of France), to teaching several courses on film and history at the University of Adelaide, [3] I have been drawn to the power of cinema to depict political and economic ideas.

I have also been dismayed at how few of those great films were made by people who understood or believed in the free market and individual liberty. Part of Marty’s and my hopes back in the 1990s was to find future filmmakers and fiction writers who were sympathetic to free market ideas, to deepen their understanding of the political and economy theory of liberty, and thus make them better advocates for liberty in their creative work, in whatever media they might have chosen. I think we largely failed in that endeavour and the program was eventually cancelled and we both went on with our lives.

That is, until I was approached out of the blue in September 2014 by a film producer based in Florida to write a screenplay on Bastiat. I thought to myself that here was an opportunity to put into practice something I had been talking about and telling others to do for decades. The producer said he had come across the first volumes of Liberty Fund’s edition of the Collected Works of Bastiat of which I was co-editor and translator. [4] He thought it would make a good movie, which I thought it would as well, and invited me to write the screenplay, which I willingly did. He told me about the software many screenplay writers use to format their material in the Hollywood regulation style (“Final Draft”), and about Blake Snyder’s amusing book Save the Cat (2005) on how to structure a good screenplay. [5] He also advised me to join the Screenwriters Guild and register my screenplay (which I did).

I intended my screenplay on Bastiat to be the classical liberal or libertarian equivalent of Warren Beatty"s brilliant but very leftwing movie Reds (1981) about the life of the American communist journalist John Reed (1887-1920) before and during the Russian Revolution of 1917. [6] It is an outstanding movie on many levels and justly won three Oscars at the Academy Awards ceremony. It combined interesting people, radical ideas, large crowd scenes, cities in revolution, and a sense of history. If my Broken Windows could achieve a fraction of this I would be a very happy man.

|

| Warren Beatty, Reds (1981) |

But to cut a long story short, this “producer from Florida” motivated me to write a long screenplay on Bastiat’s life which took two years of my life. I submitted it, along with a detailed “illustrated history” of Bastiat’s life and times, in August 2016, both of which are available online. [7] To cut an even longer story shorter, it turned out to be a scam (I think) as he wanted me to fund the project with what he called “seed money,” to take the project to “the next stage” (he suggested a figure of $100,000), which is how I think he made a living, flattering the people he approached, filling their heads with dreams of making a movie on their pet project, and then putting the hit on them financially. I declined his offer to do so.

I have no movie about Bastiat (yet) but I learnt a great deal while working on the project, looking at history from a completely different perspective from what I had done previously. For example rereading his correspondence with a movie in mind is very different from reading it from the perspective of the history of ideas. One looks for conflicts, personal ties, hidden or concealed feelings and emotions, and so on. I would like to share some of those thoughts with you today, in particular the long and hard thinking I did on how to transfer ideas about economic and political liberty onto the screen.

The Problem of the Depiction of Individual and Economic Liberty in Films↩

Introduction

Let me begin by asking what is a topic like this doing in a “libertarian scholars” conference? One could begin by saying that film theory and history is an accepted academic discipline to which libertarian scholars should be engaged in. It also addresses the broader problem of the relationship between political and economic ideas and the broader culture in which we live and how these ideas are represented (or not represented) in art in general and film in particular given its broad appeal. There is also the important matter of the political economy of making films, the place of Hollywood in that industry, the political and economic ideas of the main players in that industry and the connections they have with government, especially the Department of Defence (in the making of government approved war movies) and the Democratic Party.

I think we should be very concerned about the political and economic ideas which are presented in popular culture like books, comics, video games, TV, and films. It it worrying that classical liberal ideas are ignored or poorly represented in these media for a number of reason. One reason was identified by Friedrich Hayek in his 1949 article “The Intellectuals and Socialism” [8] where he expressed the concern that many people get their, in many cases erroneous, economic ideas from studying history at school or college and not by reading economic theory per se. I share a similar concern that many people today get their ideas about “capitalism” from popular culture, or at least have their prejudices confirmed by the TV and films they watch.

|

| Friedrich Hayek, “The Intellectuals and Socialism” (1949) |

Sometimes this can work to our advantage as in the case of Ayn Rand’s novels. It is an historical fact that many people in the modern libertarian movement came to these ideas via a “novel about ideas,” namely Ayn Rand’s Atlas Shrugged (1957) which shows how people can be influenced by the ideas (political or economic) in various art forms, especially novels then and perhaps films now. Think of the impact that “the social novel” has had on the socialist movements of the past, such as Emile Zola’s novels of the Second Empire and Third Republic, Charles Dickens in Victorian England, and Sinclair Lewis in the U.S. An interesting question we can ponder is whether films are in the same category as these social or political novels, or whether they are made and come to popular attention after people have already made up their minds on these questions and thus the films merely reinforce ideas or perceptions audiences already have.

We could also ask if the novel of ideas still has the same power to influence people’s minds in this increasingly post-literature culture, and whether a film of ideas can compete against the seemingly endless action movies based upon 40 or 50 year old comic books?

I think most of us would agree that we would like to live in a culture which is sympathetic to classical liberal, pro-liberty, and pro-individual ideas, at the very least to counter the prevalence of cultural Marxism, and the general hostility to “greed” and capitalism, and more positively to explore as widely as possible the values and ideals we believe in in all kinds of artistic representations. Now the extent to which art reflects preexisting ideas and beliefs or provokes and stimulates new ways of thinking is debatable, and it often depends on whether one is discussing popular art forms or the avant-garde. The former has to reflect pre-existing ideas among ordinary people (otherwise it will not sell), while the latter deliberately ignores them and speaks instead to artistic and intellectual elites (where once the avant-garde was funded by aristocrats, in our own day the avant-garde is often funded by the state through universities or subsidized orchestras or museums and is thus immune to the dictates of the market).

Libertarian art, if there is such a thing, is caught between these two realms: we do not have a broad enough popular constituency to support an explicit or radical form of popular libertarian art, and we are not part of the avant-garde which is left leaning at best. It has happened in the past that the avant-garde has thrust itself up from below by radical young innovators, but I do not see that happening at the moment and I am not sure Charles Koch is ready to fund a soirée for avant-garde libertarian artists and writers yet (however, his brother David might be but seems happy enough where he is in the established NYC artistic world).

When I depress myself with thoughts like these I think back to what Ayn Rand did back in the 1940s and 50s when she was living in a very hostile intellectual and cultural world, yet still managed to sell millions of copies of her novel in spite of its many flaws (it is notorious for having the longest speech in a novel ever written, as well as the not so hidden theme of rape) and inspired a libertarian movement at the height of the Cold War and Johnson’s Great Society. Yet sadly the Atlas Shrugged movies were terrible and this should be a lesson for us. They could have drawn a large audience given the number of people who have read the novels over the decades. [9]

On the other hand, there is also good evidence that people are willing to pay to watch films today which have a “pro-liberty” and “pro-individualist” perspective such as The Hunger Games (2008) series and the recent movie Joy (2015) about entrepreneurship. And there is another positive lesson with the success of the Hayek/Keynes rap videos; which of course are short videos not feature length movies.

A Liberal Culture: the “Rhetoric” and “Iconography” of Liberty

|

| Eugène Delacroix, “Liberty leading the People on the barricade” (1830) |

I sometimes ask myself whether we need a liberal culture in order to express ourselves in a unique way and to make clear to others what we mean. As you know, the left and the radical right have such an explicit culture which involves both a specific rhetoric and an iconography, as does of course the Catholic Church. They have a defined body of writings with a certain vocabulary and rhetorical devices the use of which identifies them to others immediately. They also have a stock of images upon which they can draw (an iconography - literally in the case of the Church) and an aesthetic. These things together give them a cultural foundation upon which to build, to refer to in new works, and to expand and explore further in a creative manner. For example, in terms of iconography, the swastika identifies Nazism, the hammer and sickle identifies the Soviet Union, and the cross identifies the Christian religion.

We are fortunate in having such a stock of writings and images upon which to base a libertarian or classical liberal culture. This has been built up since the 17th century beginning with the English Revolution, became firmly established in the 18th century with the European and American Enlightenment and the American and French Revolutions, and continued well into the 19th century with the development of “bourgeois” liberal culture. So in the case of a “rhetoric of liberty” we have phrases like “the rights of freeborn Englishmen,” “Magna Carta,” “innocent until proven guilty,” “self evident truths,” the rights to “Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness” which are deeply embedded in the Anglo-American-Franco tradition and well known to all (if not recognized in practice). We also have a solid body of images or “iconography of liberty” which serve a similar purpose and have a similar long history like our rhetoric of liberty. These images include the sea green ribbon of the Levellers, the Phrygian cap of liberty, Marianne [10] and the Statue of Liberty, [11] the “Don’t Tread on Me” snake image on the Gadsden flag, and the “Am I not a Brother?’” image of the 19th century abolitionists. [12] And then of course, there is my favorite image of liberty from the 19th century, Delacroix’s “Liberty Leading the People on the Barricades” (1830), [13] which I use as a kind of logo for my website. [14]

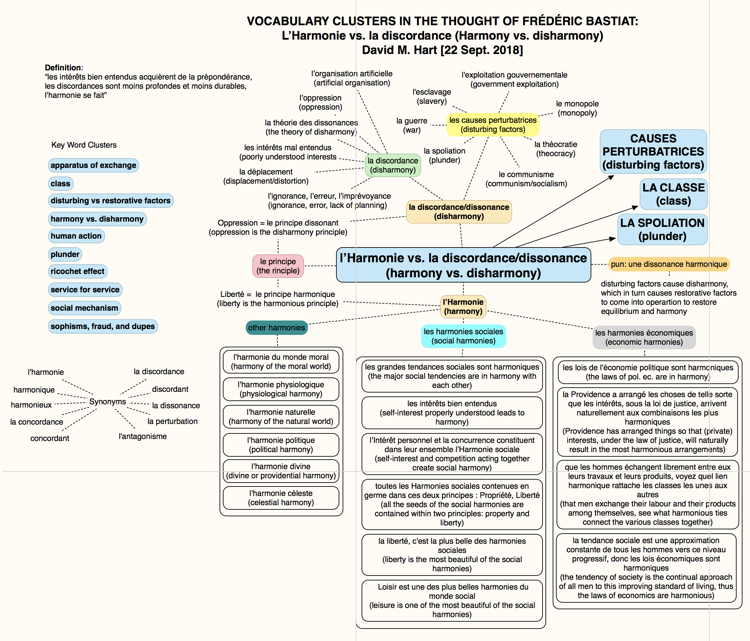

I have explored the iconography of “liberty and power” in several works such as my ongoing series on “The Images of Liberty and Power” at the OLL website [15] and a pair of lectures on “The Culture of Liberty vs. the Culture of Power” which I have given over the years. [16] More recently I have been interested in the “rhetoric of liberty” used by people like Frédéric Bastiat in his popularization of economic ideas, the well-known and loved Economic Sophisms (1846, 1848), and his unique “word clusters” which he used in his treatise Economic Harmonies, [17] Gustave de Molinari in the development of his radical idea of the private “production of security,” and the language of class used by several hundred years of classical liberal theorists. [18]

An interesting question to pose in this context is what place, if any, does film have in such an iconography of liberty? Many of us could quickly identify a film made in the socialist realist tradition, and I have have seen enough Nazi propaganda feature films to be able to do the same with them. Would we even want to be able to do the same with a “libertarian movie”, whatever that might be? But there might be some useful purpose in have a palette of images and rhetorical or visual devices which a filmmaker could “dip into” now and again to make a point and which would be instantly recognized by audiences.

Another question to pose: can economic ideas be depicted in a visual medium like film, or is economics a purely “verbal” analytical discipline (as Austrians would argue, though not Keynesians with their mathematical models of the economy). How would you show visually something like, opportunity cost (missed opportunities), unintended consequences, entrepreneurial insight, or time preference? D. McCloskey has argued that economics is a deeply “rhetorical” discipline, in that it has well-established methods of persuading people of the correctness of its propositions which are rhetorical in their nature (whether by words, tables of data, graphs, or equations). [19] Bastiat had a very well-developed verbal “rhetoric of liberty” in his efforts to popularise economic ideas which involved telling stories and “economic parables”, writing little plays and dialogs between stock characters (like a free trader and a protectionist), writing satires and parodies, and using very blunt or harsh language by calling “a spade a spade.” [20] Only later in his treatise, Economic Harmonies, did he attempt to use images to explain his economic reasoning, which may be a first in economics. [21]

I will mention here as an aside, that Bastiat was often very theatrical in his efforts to popularise economic ideas to a broad audience by telling stories, writing plays (even plays within plays), and making parodies of classic French plays (by Molière). [22] So, writing or telling or filming a story about him telling economic stories is quite ironic though very fitting. If he had know about film, I’m sure he would have approved.

So I wonder, given these difficulties, how could one create an “ iconography of economics and liberty” which might be adapted for use in a film?

The Problem revisited: Atlas might have shrugged, but audiences did too

|

| Atlas Shrugged Part I (2011-14) |

When one looks back on the history of cinema during the 20th century one is struck by the paucity of liberal directors, producers, and screenplay writers. But this should come as no surprise since cinema emerged as a major cultural force in that period just as classical liberal went into a nearly century long decline (even eclipse). Some of the great periods of cinematic innovation took place when classical liberal artists largely no longer existed and when they did they were marginalized and ignored. I have in mind German Expressionism in the 1920s, French cinema in the 1930s, Hollywood during the 1930s and 40s (during the New Deal), French and Italian New Wave in the immediate post-war period (when the modern welfare was being built), and so on.

Interesting and excellent movies about ideas were made during this period, of course, but their message was often “skewed” for classical liberals in that they might be “individualistic” or “anti-authority” or whatever, but the message was “degraded” or “clouded” shall we say by other ideological baggage or interpretations which we would not find congenial or just wrong (hostility to “capitalism,” “consumerism,” the bourgeoisie, and so on).

My list of great movies about ideas (listed in the Filmography below) show how, in spite of the ideological perspective of filmmakers, many great and important films classical liberals could enjoy and even celebrate were made, but it makes one wonder what might have been if things had been otherwise …

The Problem of Filming a “Positive” vs. a “Negative” Depiction of Liberty, or “the Seen” and “the Unseen”

Or, there might be an inherent problem for classically liberal-minded filmmakers to overcome. What if showing free markets and individual liberty is inherently too complex to show on the screen or too boring to watch? What if the only interesting drama comes out of the violation or absence of individual liberty and free markets, of the conflict which arises between peaceful traders and violent regulators of trade? I call these alternatives “the positive depiction of liberty” and “the negative depiction of liberty (or the absence of liberty)”.

What if it is the case that filming peace and prosperity is intrinsically boring since there is a lack of conflict and hence drama. There might be haggling and negotiation, attempts to persuade and influence each other, but ultimately a trade does not take place unless both sides benefit (unless coercion intrudes). This is not, I would suggest, cinematically interesting. My solution to this problem is to achieve the same purpose indirectly, that is by having mutually beneficial market activities take place as a backdrop to other human activities. The viewer just takes it as “a given” that trade is taking place and that both parties benefit.

|

| Eliot Ness and the war against alcohol |

If it is uninteresting or boring to make a film about “a positive”, i.e. free markets are good, perhaps we should stick to making films about a “negative”, i.e. what happens in the absence of peace and freedom, when people are prevented from engaging in mutually beneficial exchanges, and the hurt and upset this causes, especially if the state and its agents have to use violence to prevent such trades.

Two interesting examples of how markets are repressed come from The Hunger Games (2008-) and The Untouchables (1987). In The Hunger Games the central state regulates the entire economy and different regions are forced to specialize in certain industrial and economic activities. There are widespread black markets which help the local people get the essential food and other supplies which are rationed by the state. We see Katniss hunting birds and other game illegally in a banned area which she trades for other supplies. We also see a local second hand goods market where people are trying to scratch a living. Nothing is directly said but the viewer is expected to figure this out for themselves, that government controls cause shortages and force people to engage in banned black market activities to survive. A counter example is The Untouchables (1987) (the 1970s film The French Connection (1971) might also be mentioned here), where the filmmaker’s intent is to show “heroic” policemen trying to stamp out illegal trading activities (the sale of alcohol in one and heroine in the other) by wicked “peddlers” and “pushers” of banned substances. In my case the filmmaker had the opposite impact. When I watched these films I was rooting for the drug dealers against the wicked state regulators who had initiated violence against the peaceful traders and I applauded the latter’s efforts and ingenuity in avoiding or evading the actions of the police.

I would mention three other examples of the “negative depiction of liberty” (or the absence of peace and freedom) which have spawned a number of excellent films. Firstly, there is the great tradition of anti-war films such as All Quiet on the Western Front (1930), MASH (1970), and Catch-22 (1970). I will not say much about this genre here except to ask whether libertarian filmmakers as libertarians have anything new to say about this?

The second example are the films which depict the absence of justice, such as false imprisonment, police brutality, the corruption of the justice system, tax rebellions, and resistance to slavery. I have in mind here Gandhi (1982) and its depiction of the opposition to the salt tax (among many other things), (Spartacus (1960), Amazing Grace (2006), and Birth of a Nation (2016) all of which deal with the issue of resistance and opposition to slavery. As an aside: maybe someday someone will make a film about Lysander Spooner and John Brown and their efforts to supply weapons to slaves and runaway slaves to defend themselves against their tyrannous owners.

The third example are the depictions of dystopias in which every aspect of a person’s life is controlled by the state. I have in mind films like 1984 (1984) and TV shows like The Prisoner (1967).

A interesting sub-genre are films which use black humour and satire to mock and undermine the lack of liberty in which individuals may find themselves . The abuse of political power, corruption, hypocrisy, and sheer stupidity are criticized in this way in films like Catch-22 (1970) and Dr. Strangelove (1964), and TV shows like Yes, Minister (1980-1984) and Yes, Prime Minister (1986-1988). I would regard the latter as one of the great libertarian, even “public choice”, TV shows ever made.

Some Thoughts on Presenting Ideas in Film↩

Introduction

In one sense films are by their very nature are “individualistic” because we see events through the eyes of the protagonists (who are acting, thinking, and choosing individuals), the choices they make, the actions they take based on these ideas, the interaction between the different actors, and the consequences of their actions. In thinking about the presentation of ideas in films I have been guided by what I call an “Austrian theory of film” which is based on Mises’ theory of “human action” and the role that he thought “ideas” played in determining that action, to which I have added Bastiat’s theory of “the seen” and “the unseen,” where ideas are “the unseen” and the actions people take based upon those ideas are “the seen.” I will provide an outline of such a theory below.

In brief, ideas can be presented in films either directly (through speech) or indirectly by inference from the images and the “action” which one sees on the screen (both the traditional form of “action” in a movie, as well as in the “Austrian” sense).

The filmmaker is in effect creating an entire world for the viewer to experience, which it is self-contained in many ways and takes for granted certain norms about the characters and the events which unfold which are created by the filmmaker. On the other hand viewers will bring with them to the cinema their own views and norms which the film may or may not challenge or confirm. The issue for us is how to entice or “nudge” the viewer into entering our world for a brief moment and to see and experience things the way we do. Like science fiction movies where there has to be a “suspension of belief” by the viewer before they can enter the new world the filmmaker has created, for viewers who do not share classical liberal values or beliefs there has to be a similar “suspension of political belief” at least temporarily. For this suspension of political belief to happen the events have to be plausible (even true if possible), the main characters have to be appealing or interesting, the drama gripping, and the images exciting to look at.

Some Good Movies of Ideas

I’m sure we are all in agreement when I say I would like to see more films made which are sympathetic to notions of individual and economic liberty, at least implicitly. As part of this aim, I have given some thought to (1) how to make a good “movie of ideas” in general, and (2) how to make one which would take a strong stand in favour of individual liberty and economic liberty in particular.

One way of doing this is to examine examples of good movies of ideas and political movies and to study how they were made and why they were successful (both at the box office and critically). (See my list of the good films of ideas in the Filmography below.)

Another way was to try to write a screenplay for a movie myself and to use that exercise as a way to think through the problems and hopefully come up with some practical ideas. My screenplay, called “Broken Windows”, is about the French free market economist Frédéric Bastiat (1801-1850) who lived through and participated in the 1848 Revolution.

Four movies which have inspired me in particular are Abel Gance’s silent movie Napoléon (1927), Akira Kurosawa’s Seven Samurai (1954), Stanley Kubrick’s Spartacus (1960) and Warren Beatty’s Reds (1981).

An excellent example of a wordless way to convey political ideas is in Abel Gance’s epic silent film Napoléon (1927) where he tells us with a scene of a schoolboys’ snowball fight all we need to know about the future Emperor of France.

|

| Abel Gance, Napoléon (1927) |

Kurosawa’s The Seven Samurai is not normally considered to be a film about ideas but a classic reworking of a story about samurai warriors in early modern Japan. Yet, it can also be seen as a powerful film about defenceless peasants who have been neglected by the state and who are being robbed by a group of roving bandits; they seek outside, private help in defending their village, and employ a group of seven “masterless” samurais to take on the task. The ideas behind this action are implied not spelled out explicitly: namely the right of individuals to defend themselves and their property from attack, their right to do it themselves or to employ an outside agency to provide these security services for them at an agreed upon price. What is remarkable about this film is how it does all this almost wordlessly, or at least with a minimal amount of dialogue. There are no speeches but the problem is understood, the bargain is struck, and the men go about their business. It is also a beautiful and important film which inspired an American western John Sturges’ The Magnificent Seven (1960), which is very fitting since it had been inspired by American westerns in the first place.

|

|

| Akira Kurosawa, The Seven Samurai (1954) |

Kubrick’s Spartacus (1960) is about a slave revolt during the Roman Republic and is interesting for a number of reasons; firstly that it was based on a novel by a Marxist Howard Fast, [23] and a screenplay by a communist Dalton Trumbo, yet it tells an inspiring libertarian story about a man’s desire for freedom from the worst kind of oppression imaginable. It also has spectacular fight and battle sequences on a massive scale. Secondly, it too does not have to be explicit about the ideas which lay behind the film. A man is enslaved, he is treated brutally, he resents being a slave, he wishes to be free, and takes action to do so by organising others in his struggle. These ideas are taken for granted and the film moves forward from there. The action naturally follows from the logic of these unchallenged goals and beliefs.

|

| Stanley Kubrick, Spartacus (1960) |

I will not repeat what I said about Warren Beatty’s Reds above.

Some Examples of the Direct Expression of Ideas

I will argue that ideas in films can be expressed in the following ways:

- wordlessly as in the examples above of The Seven Samurai and Spartacus - the viewer takes the ideas behind the movie for granted without any need for a character to articulate them explicitly as they are obvious and implied by what happens; they are like a “statement of fact” which has meaning in the context of the film and the main character

- the direct expression of ideas as in actual speeches (say of politicians), and the small, private conversations between the protagonists (say among friends in a bar or restaurant)

- the indirect expression of ideas through inference; we see images or activity (human action) which needs no explanation or discussion as in the following three kinds:

- the static images of the built environs in which the film takes place (as in a prison, or the walls of city (more below on this)); it is clear from the image that the state hems us in, confines and restricts us, and controls our freedom of movement

- actions by the state and its representatives which show them violating rights to life, liberty, and property of individuals; this is an opportunity to show the “everyday violence” of state control and repression; the unarticulated view is that the actions of the state are violent and hurtful and hence bad

- actions by private individuals who are just going about their everyday business in the background with no need for verbal description or justification; one concludes from viewing this that these private acts help people and are thus interpreted as being good

- the actions and expressed ideas of the protagonist him/herself

It is impossible to avoid the direct expression of ideas entirely in a film about a politician, lawyer, scientist, or a business leader. Public speeches or formal declarations of what the character believes have to be kept to an absolute minimum and when one does resort to them they have to be short, contentious, and dramatic in order to hold the viewer’s attention. Some examples of set speeches which work in movies include the following:

- the filibuster speech of Mr. Smith (James Stewart) who fights corruption in Washington in Frank Capra’s Mr Smith goes to Washington (1939)

- Don Walling’s (William Holden) boardroom speech in Robert Wise’s Executive Suite (1954) - resolving conflict non-violently in the board room

- Danton’s (Gerard Depardieu) speech in court and his private dinner with Robespierre in Andrzej Wajda’s Danton (1983) - opposing the dictatorship of the Terror

- Gordon Gecko’s (Michael Douglas) speech to the shareholders in Oliver Stone’s Wall Street (1987) - the “Greed its good” speech

- John Quincy Adam’s (Anthony Hopkins) courtroom speeches in Stephen Spielberg’s Amistad (1997) - defending the release of mutinous slaves

- speeches by William Wilberforce (Ioan Gruffudd), Thomas Clarkson (Rufus Sewell ) and others in Michael Apted’s Amazing Grace (2006) - discussions among the abolitionists, speeches and voting in the House of Commons

- the speech by Robin Hood (Russell Crowe) challenging the usurping powers of Prince John in Ridley Scott’s remake of Robin Hood (2010)

Some other good films which have lots of private conversation which work well:

- Davis, Juror 8 (Henry Fonda) persuades his fellow jurors one way and then the other way in a discussion of the guilt of an 18 year old man in Sidney Lumet’s 12 Angry Men (1957) - nothing but conversation in a small jurors room

- the father Charlie (James Stewart) discusses the morality of going to war with his sons around the dinner table in Andrew V. McLaglen"s Shenandoah (1965)

- a dinner conversation between Andre (Andre Gregory and Wally (Wallace Shawn) in Louis Malle’s My Dinner with André (1981) - nothing but talking over dinner about the theatre and life in general

- Quentin Tarantino, Pulp Fiction (1994) - constant witty and ironic conversation interspersed with extreme violence

- Quentin Tarantino, Kill Bill: Volume 1 (2003) and Volume 2 (2004) - constant conversation (voiceover) interspersed with extreme violence

Another good example of how a great deal of conversation can be successful are TV sitcoms which in many cases are nothing but talk in confined spaces with very few sets. I have in mind:

- Larry David and Jerry Seinfeld, Seinfeld (NBC, 1989-1998): all talk and hardly any action because it is “about nothing”; really a comedy of manners

- David Angell, Peter Casey, and David Lee, Frasier (NBC 1993-2004) - discussion about as well as living with neuroses and psychiatry

- Chuck Lorre and Bill Prady, The Big Bang Theory (CBS 2007-2019) - talk about science between science nerds

The problem for the filmmaker or screenplay writer is to get the balance right between ideas which are directly expressed in set pieces (such as speeches) or in private conversations, or indirectly inferred by seeing various actions and images.

Ideas and Human Action in Film: Towards an Austrian Theory of Film/Cinema↩

Mises on Ideas, Interests, and Human Action

When thinking about the problems a filmmaker faces when trying to make a “movie of ideas” I was struck by the relevance of the works of two economists, that of Ludwig von Mises’ theory of “human action” and Frédéric Bastiat’s theory of “the seen and the unseen,” in helping the filmmaker think about the problems of depicting economic ideas and economic actions in a visual medium like film. It made me think that perhaps we should develop an “Austrian theory of Film” to help us do this. If there can be a feminist theory of film and a Marxist theory of film, why not an Austrian theory of film?

Mises is relevant because according to his theory of human action people act upon the ideas they have about what their interests are (in many cases these are economic interests), what their alternatives might be, and how best they can attempt to satisfy those interests given their scarce resources and other options. In essence then, human action is based upon the ideas people hold.

Bastiat is relevant because the ideas people hold in their heads are a textbook example of what is invisible to outsiders, in other words they are “the unseen” perhaps even the unseeable, yet the actions which people take based upon the ideas they have about themselves, their interests, and the world around them can be “seen” in the actions they take. [24]

In the sphere of economics an action, a habit, an institution, or a law engenders not just one effect but a series of effects. Of these effects only the first is immediate; it is revealed simultaneously with its cause; it is seen. The others merely occur successively; they are not seen; we are lucky if we foresee them.

The entire difference between a bad and a good Economist is apparent here. A bad one relies on the visible effect, while the good one takes account both of the effect one can see and of those one must foresee.

See also the entry on “The Seen and the Unseen” in Further Aspects of Bastiat’s Thought, CW5 (forthcoming).

I want to prepare you for a very bad pun: we have all heard of the “action movie” and know how popular it is as a genre (e.g. “The Fast and Furious” franchise (2001)); what I am proposing is an entirely new genre, the “human action movie” (perhaps we could call it “the Peaceful and Productive” franchise).

The question then is, can the filmmaker use these theories about economic behavior to make an interesting film with economic themes.

In a movie there are three major components, how the film looks, how it sounds, and how the protagonists act, react, and interact with each other. The latter is made up of what they do and what they say.

When I say “action” I mean this in both the traditional sense of physical movement (such as a journey, a car chase, seeking a goal, or just going about their business) and personal conflict (fights, violence, confrontations, arguments), but also very much in the Austrian sense of individuals making choices and then acting upon those choices. I think there could be some interesting work to be done in formulating a theory of “the cinematography of human action” (or “dramaturgy of human action”) which I am going to trademark here and now!) which shows how human action in the Austrian sense is also a key feature of films, and when combined with Bastiat’s theory of the seen and the unseen suggests that the filmmaker has to use “seen” and visible action to make “unseen” (and probably unexpressed and thus “unheard”) ideas seen and thus more understandable to the viewer.

Mises discussed the connection between ideas, interests, and human action in his treatise Human Action (1949) and again in Theory and History (1957). These can be summarized in the following passages. (See the Appendix for a more complete list of relevant quotations.) [25]

In the world of reality, life, and human action there is no such thing as interests independent of ideas, preceding them temporally and logically. What a man considers his interest is the result of his ideas. (TH, p. 93)

Action is preceded by thinking. Thinking is to deliberate beforehand over future action and to reflect afterwards upon past action. Thinking and acting are inseparable. Every action is always based on a definite idea about causal relations. (HA1, p. 177)

Verstehen [understanding] … is the method which all historians and all other people always apply in commenting upon human events of the past and in forecasting future events. (HA1, p. 50)

If one thinks of the filmmaker of “a movie of ideas” as an “historian” or a “teller of stories” then the task is to try to get the viewer “to understand” (Verstehen) the ideas which lie behind the actions the protagonist takes, to make “visible” that which is not obviously visible to the “cinematic eye” but which is implied in their very actions taken or not taken.

Helping the Viewer see the Connection between Ideas and Action: “Product Placement” and Visual Nudging

A key question to ask is whether the ordinary film viewer can correctly infer the ideas which lie behind a person’s choices and actions as depicted in a film, and how subtle should a screenplay writer or director be in giving the viewer hints in a kind of visual “nudging”?

One of the best examples I know of where the filmmaker doesn’t have to say anything to help the viewer understand the idea behind the whole movie is Kubrick’s film Spartacus (1960). There is no need for a speech or conversation about the natural rights of every individual to life, liberty, and property, or the Lockean theory self-ownership, to set up the movie because it is clear that Spartacus is a slave, that he is maltreated very badly, he doesn’t like this situation, and wants to escape. End of discussion and everything that follows in the movie follows naturally from this unstated and non-articulated intellectual position. The challenge for the filmmaker of the Bastiat story is to try to achieve something similar in order to avoid too much talking and speechifying. Hence the need for the viewer to see the state and its functionaries doing lots of bad things to ordinary people (the seen action) so that Bastiat’s actions to challenge or overturn these seem the perfectly natural thing to do which any ordinary right thinking person would support. Thus as much of the film as possible needs to show the viewer what actions Bastiat has to take in order to accomplish this and the obstacles he has to overcome along the way. In a way, the complex system of ideas which lies behind Bastiat’s actions are almost assumed away and taken for granted (or just hinted at).

Another more subtle example is the trick of placing books with a particular point of view in a shot which is barely seen by the viewer. The camera pans across the books, say on a desk or a bookshelf in a room, which possibly register subliminally but can only really be seen when freeze framed. Think of Oliver Stone’s Born on the Fourth of July (1989) when we catch a glimpse of Erich Maria Remarque’s classic anti-war novel Im Western nichts Neues (All Quiet on the Western Front) (1928) on the desk, or B.F. Skinner"s book Science and Human Behaviour (1953) on the psychiatrist’s office bookshelf in Clint Eastwood’s American Sniper (2014) (which I happen to think is also a powerful anti war movie). One could also do the same with works of art which I have done in my screenplay (a couple of works by Bastiat’s contemporary Eugene Delacroix). The problem with this is that tricks like this, a kind of intellectual “product placement”, then become in-jokes or obscure references which only the cognoscenti will understand and appreciate. Whether this trick works or not for the average viewer is debatable.

A good example of a kind of “visual nudging” to help the viewer see what is “unseen” takes place in the film Joy (2015) when the protagonist Joy Mangano (Jennifer Lawrence) has her moment of entrepreneurial insight and all we see is her face in close up as she comes to this realization. We see “the penny drop” as it were.

|

| The joy of entrepreneurship |

Some More Thoughts on Presenting Ideas in Film: The “Broken Windows” Experiment↩

Introduction

You can’t make a movie or a revolution without breaking some windows. (David Hart)

Let me now turn to putting into practice (or suggesting how they might be) some of the historical and theoretical ideas I have presented above. Where I have have made reference to my Bastiat screenplay above, I will try to collect them here for the sake of convenience.

As I related above, I was presented with an opportunity to turn a story of Bastiat’s life and work into a movie which I accepted with relish as I thought it was both an interesting intellectual challenge and an opportunity to put into practice ideas which I had been thinking about for decades.

I refer you to the online copy of my screenplay “Broken Windows” and its accompanying “illustrated essay" on what I think 1848 Paris during the revolution looked like. [26]

There are many challenges in making a film about Bastiat in the 1848 Revolution. Firstly, there is the challenge of filming in an old city which doesn’t exist anymore. For example, the massive fortification wall built around the city between 1841-44 has largely been demolished but it played a dominating role in the city’s landscape in 1848. This would have to be recreated by CGI (see Agora (2009) for an example of how this might be done in the case of the ancient city of Alexandria). [27] Secondly, in a film about a city experiencing a revolution there is the challenge of recreating large and often violent crowd senes, and in the case of Paris the hundreds of street barricades which were erected in March and June which were only overcome by the massive use of artillery being fired in the streets of Paris (see the map drawn up by the government enquiry following the June Days uprising). Bastiat was an eyewitness to both these events.

|

| Map of Paris showing positions of the barricades in June 1848 |

Thirdly, there is the challenge of making a film about an intellectual, in this case an economist and free trade activist, whose life and activities are probably not of much immediate interest to the average filmgoer. So, how does one make such as person interesting enough for the viewer to pay $10 and watch a 2 hour movie. Fourthly, there is the challenge of showing how markets work and what happens when they don’t or aren’t allowed to, which was a major cause of the February Revolution in 1848 and a major driving force behind Bastiat’s and the other economist’s activities in this period.

Fortunately, both Bastiat’s personal life and the events of 1848 are “cinematic” enough in my view to make an interesting movie of ideas.

How “Cinematic” was the life of Bastiat?

Making Bastiat interesting to the Viewer: An Overview

There is a double problem we face in making a film about Bastiat. First there is the more general problem of making a film of ideas interesting to the general public, then there is the more specific problem of making a film about an economist, who is probably even less interesting than an historian like myself. How does one make the life of an economist and the ideas and issues he is interested in interesting to ordinary people and likable enough to be worth spending two hours with? The filmmaker will have have to show Bastiat the economist’s similarity to ordinary people, who has similar concerns and problems, as well as unusual concerns and interests which they may want to spend some time learning about.

Fortunately in Bastiat we have a very interesting and engaging person who is a bit of a “character” with his Gascogne regional accent and dress, his wicked sense of humor (his use of satire and his ability to parody politicians), and his “party skills” (he liked singing ribald and disrespectful political songs, and playing the cello). He also had a passion for justice which made itself felt in his crusade to create a Free Trade movement to lower the cost of food and clothing for ordinary French people, and to get into politics during the revolution in order to cut their heavy burden of indirect taxes. The major missing element is the lack of an obvious romantic interest (but this is something a creative filmmaker can plausibly “fix” if necessary - see below for details). And to add some pathos to the mixture, he discovered late in his life that he had an incurable disease of the throat (possibly cancer) which was extremely painful, made him lose his voice (something which was very difficult and embarrassing for a newly elected politician), and meant that it was a race against time for him to finish the tasks he had set himself (to cut taxes on the poor and finish writing a theoretical work on economics) before he died (he would die at the age of 49).

In editing and translating the volumes in the Bastiat translation Project for LF I was also struck by how “cinematic” his life was in terms of the very striking visuals of his homeland in the Basque and wine-growing regions of southwest France where he lived as a gentleman farmer and winegrower for most of his life; and of course the city of Paris where he moved at the relatively mature age of 44 to take up a completely new life as a free trade organiser, politician, economic journalist, and economic theorist.

His life as a farmer and local magistrate in Les Landes provides opportunities to show the bustling port towns of Bayonne and Bordeaux, the river traffic and trade, and the smuggling of highly taxed goods which was rife across Spanish border. He was active in local liberal politics in the garrison town of Bayonne where he participated in the local singing clubs, called Goguettes, where he learned the satirical and political songs of Béranger. He would have witnessed the efforts of the local police to close down these clubs on a regular basis when they became “too political” as political meetings were strictly prohibited during the 1820s and 30s, and the resistance of the ordinary people to those heavy handed tactics when they started up new clubs almost immediately. Later, his Paris friend Gustave de Molinari described Bastiat as having a “Rabelaisian wit” which means that he had a mocking sense of humor which probably tended towards the bawdy and scatological as much as the political. Even before he went to Paris he got involved in the Revolution of July 1830 which overthrew the oppressive Bourbon monarchy. He took the risky step of personally visiting the garrison one night in August when the revolution had not yet succeeded in order to persuade the young officers to side with the new more liberal minded regime of Louis Philippe. So, we have a wonderful scene of him and the officers agreeing to support the revolution and singing political songs and drinking wine well into the night.

He was inspired to uproot his life in provincial Mugron and move to Paris as a result of the political and economic upheavals caused by the anti-tariff free trade Anti-Corn-Law League in England. He wanted to destroy the power of the “oligarchs” who controlled France just as Richard Cobden and his followers were trying to do in England. He was instrumental in helping found the French Free Trade Association which organised mass meetings in large public halls throughout the country during 1846 and 1847 to protest the high price of food caused by trade restrictions and government created monopolies. These meetings took place at a time of harvest failure in France when the price of bread soared and people rioted and smashed bakeries. The free traders were often met with hostile opponents who heckled the speakers and disrupted the handing out of their literature. The inaction and incompetence of the government during the food crisis triggered a political protest movement to agitate for democratic reforms and the removal of corrupt and ineffectual officials. Since political meetings and parties were banned the protesters organised mass “political banquets” which were held outdoors and attended by a thousand or more people at a time throughout 1847. Instead of giving political speeches (which were banned) the protesters held round after round of political “toasts” which challenged the police to shut them down and thus cause further protests and demonstrations. The free trade economists attended these banquets and gave toasts to “free trade” and economic and political reforms. We have no direct information that Bastiat attended one but he could well have which is enough for a flexible filmmaker to seize upon.

When a banquet was cancelled by the police (it was to be held on George Washington’s birthday to show the protesters’ commitment to republicanism and democracy) a protest march was held in Paris which got out of control and led to the abdication and then overthrow of King Louis Philippe and the declaration of the Second Republic in February 1848. Bastiat was personally crushed when the French Free Trade Association was closed down (it had been his dream for several years) but he quickly turned to opposing the socialist movement which had unexpectedly sprung up once the regime collapsed. He and a small group of radical friends started a magazine which they handed out on the streets of Paris in March 1848 to the ordinary workers and citizens. It was when doing this that Bastiat witnessed the violence of the troops first hand (for the first time; it would happen again in June) when he and his friends were caught in the crossfire as troops moved in to remove the protesters’ barricades which had been thrown up across Paris. He also joined with some friends to start a political club (one of hundreds which appeared in March when the laws against political speech and association were no longer enforced) to argue in the street face to face with the socialists over such issues as the right to a (government issued) job for all workers. Their club lasted only a few weeks as, according to Molinari again, their meetings were broken up violently by a group of “communist thugs”.

Bastiat’s next step was to abandon street journalism and debating with the socialists to stand for election in his home town of Mugron for the new Constituent Assembly. He won the seat and spent the next two years serving as a Deputy in the Chamber. In addition to his parliamentary duties (he was elected by the Deputies to be the VP of the Fiance Committee where he attempted to introduce his tax and tariff cutting program) he started a new career as an anti-socialist pamphleteer and an economic theorist. We should note that he couldn’t resist another bout of street journalism in June 1848 when he and his friends started a second magazine which they handed out on the streets of Paris in which they tried to appeal directly to the workers not to be taken in by the promises of the socialists. Once again, he was caught up in the violence of the June Days uprising when hundreds of barricades were again built across the streets and this time the troops used heavy artillery to blow up the barricades and to disperse and arrest the protesters. Bastiat tells us in a letter he was trapped behind one of the street barricades until he flashed his Deputy’s badge at an officer who agreed to a cease fire while the dead and wounded were removed to the side streets.

The above is just a brief summary of the most dramatic and cinematic events Bastiat was involved in during the Revolution which includes riots and revolution, and violent confrontations with socialists, the police, and the army. This provides the backdrop for the other things were were taking place in his life. This more personal and human drama includes his ambition to start a free trade movement in France, the setbacks to this ambition, the choices he has to make about the direction his life will then take, his conflict with rivals (protectionists, socialists, other politicians), the interesting people of his time with whom he interacted, his idiosyncratic and highly individual character, and ultimately his race against time to achieve his goals before his premature death from cancer.

The personal drama of is life is quite extensive, so the filmmaker would have to choose what to emphasize and what to leave out for the sake of brevity. It includes the following:

- discovering at an older age (44) that he had new things he wanted to do:

- he had developed a passion to end the injustice of protectionism; and build and lead a French French Free Trade Association like the Anti-Corn Law League in England

- that he had original economic thoughts and doubts about whether he could express them and be accepted by Paris school economists

- he felt great fear and uncertainty about moving to Paris (which he called “Babylon”) and leave his comfortable provincial life at his age

- after moving to Paris he almost single-handedly ran the new French Free Trade Association, organising a broad-based popular movement, giving speeches to large crowds across the country, and editing and writing most of the articles for the Association’s magazine; after so much work he was devastated when the French Free Trade Association was suspended when revolution broke out in February

- his brilliance as an economic journalist, perhaps the best who has ever lived;

- the very theatrical nature of many of his best pieces; his dialogues, little plays, parodies of plays, fictitious petitions to the government; one of these deserves to be “performed” in the film

- his participation in three salons in Paris: two run by the wives of wealthy supporters of the free trade movement, and a third by a radical journalist who would have introduced to him many other radicals such as republicans and socialists

- he was the star at two of the Paris salons; this is a chance to show off his wit, musical skills

- he got caught up in the violence of Feb. and June 1848;

- he published two small magazines which he handed out on the streets, and was eyewitness to some violent events

- he participated in the rowdy but free speech of the political clubs (Marx was there)

- he witnessed the police and army repression of dissidents

- after his election to the Chamber in April 1848 he

- played a leading role in the economic reform of France as VP of Finance Committee (CL caught between left and right)

- became an anti-socialist pamphleteer of considerable note

- he was in the Chamber when supporters of the socialist Louis Blanc stormed the building with arms in order to stage a coup in May 1848

- dying of incurable throat cancer, his race against time to achieve everything he wanted to achieve before he died

- his battle to work on and finish magnum opus the treatise Economic Harmonies

- the irony and frustration of him losing his voice just after he got elected and got a platform to express his ideas in the Chamber

- the true but highly dramatic way he said farewell to his closest friends at a final lunch in the woods at Butard Lodge, literally “riding off into the sunset”

How “Cinematic” was Paris and the Revolution of 1848?

Recreating the Look of Paris in 1848

|

| The military wall around Paris 1841-44 |

The look of Paris in the mid- and late-1840s is a gift for the filmmaker although it poses some problems of reconstructing some architecture which has been dismantled since. I have collected a number of images from contemporary illustrated newspapers and other sources of art in an attempt to recreate who the city looked like.

Some of the more important images and events include the following:

- the three rings of customs walls and gates which surrounded Paris; the inner octrois gates built in the 1780s for the tax-famers; the huge “Thiers’ wall of fortification built around the city in 1841—44; and the ring of star-shaped forts which circled the city; thus everybody had to enter and leave the city through thee gates, walls, and forts providing a great image of state control and oppression

- the large public halls where meetings of thousands of people were held for the Free Trade Association and the Peace Congress; these would have been very crowded, hot, and contentious, with heckling and booing

- the beautiful stately homes of the wealthy benefactors of the free trade movement and the economists circle; these were witty salons run by smart, rich women in fancy dresses

- the new symbols of economic progress which were the main train routes leading in and out of Paris and their corresponding massive train stations; there were being built in the 1840s when Bastiat came to Paris

- other new and expanding industries which would promote some excellent images are:

- the new department stores which began to appear in Paris in the late 1830s, which revolutionized shopping; Zola’s novels depicted this negatively (some were made into films such as René Clément, Gervaise (1956))

- the print and publishing industry which made low cost printing of books and newspapers possible for the first time; this was essential for the economists (and their rivals the socialists) to get the word out to the people

- working class bars and singing societies (Goguettes) where banned politics meetings were held in spite of police raids

- concert halls and theaters: the general cultural, musical, artistic life of the leading capital of Europe: Delacroix, Berlioz, Chopin, Hugo, Béranger, Dumas

Crowd scenes and Violence in 1848 Revolution

|

| A barricade on rue Saint Martin (Feb. 1848) |

A good movie (even one of ideas) might need to have its fair share of sex and violence. Concerning the latter the agitation for free trade and the Revolution provide several examples a filmmaker could use. We are “lucky” in this respect since Bastiat lived through a bloody and violent revolution and he saw things at first hand.

- he probably witnessed food riots and the smashing of bakers’ shops during the crop failures and food crisis in 1846-47

- he witnessed illegal political meetings busted up by police - the outdoor political banquets of 1847, and goguettes

- there was considerable violence in Paris streets in February and June 1848 and he wrote a couple of letters about what he saw and did on the streets; getting caught in the crossfire, calling for a cease-fire and helping injured to safety in the side streets

- he attended public meetings which were broken up by communist thugs (the Political Clubs of February/March/April 1848)

- he was in Chamber in May 1848 when supporters of the socialist Louis Blanc broke in and tried to stage a coup; (he later was one of the few Deputies to defend Blanc)

- he witnessed the police crackdown on the political clubs and meetings in 1849

There are whole books devoted to the history and cultural of building and manning the barricades in Paris which can be used to make these scenes historically accurate. For example, Mark Traugott, The Insurgent Barricade (2010). [28]

|

| Meissonier, “A Barricade in June 1848" |

|

| The invasion of the Assembly by Blanc supporters (May 1848) |

The Direct Expression of Ideas: Set Speeches

Introduction

To summarize my thoughts on how ideas can be expressed in films, I believe the can be done so directly or indirectly. They can be expressed indirectly showing things such as:

- static images of state power

- the everyday violence of the state

- the everyday good things done by the market

- the violence of the revolution

- works of art and literature

They can be expressed directly in the form of

- set speeches

- private conversations

Set Speeches

|

| Paris Peace Congress (August 1849) |

We can’t avoid having a couple of set speeches as this was part of Bastiat’s life as a free trade organizer, politician, and peace activist. The speeches have to kept to a minimum to avoid boring the viewer. Nevertheless, these meetings took place in beautiful and very large public halls which dotted Paris, with thousands of people in attendance, with hecklers from the audience to maker things even more interesting. These would be an opportunity to show off Bastiat’s considerable eloquence and wit. These meetings included:

- French Free Trade Association meetings 1846-47

- his speeches in Chamber of Deputies of cutting taxes and allowing workings the right to form unions; during the speeches he got heckled by the left and the right at times

- the big international Friends of Peace Congress held Paris Aug. 1849; the president of the meeting was Victor Hugo and Bastiat gave one of the key speeches to a huge audience.

The Direct Expression of Ideas: Private Conversations

Since conversations with others is such an important part of the life of an intellectual we also can’t avoid having these as a way of telling the viewer what Bastiat thinks about various topics, what problems he faces, how he plans to overcome or resolve these problems, the doubts he might have about what he wants to do next, and so. Again, these conversations have to be kept to a minimum and be in proportion to the other parts of the movie. The types of private conversations Bastiat engaged in include the following:

- private conversations with his close friends in Mugron, such as Felix, the other members of the local “Academy” book club, at the banned singing clubs or goguettes in Bayonne, his singing and drinking with officers of the Bayonne garrison during the Revolution of July 1830

- his conversations with other economists and the financial supporters of the French Free Trade Association

- his conversations with the economists and publishers at the Guillaumin publishing firm

- conversations with his friends who published and wrote the two street magazines he handed out during the revolution

- the conversations he had with the radicals and socialists in Castille’s soirée

- the witty conversations he participated in at Hortense’s Paris soirée

- the conversations and arguments he had in the Chamber’s Finance Committee over cutting taxes and government expenditure

The Soirées

The three soirées in Paris that Bastiat participated in provide a wonderful opportunity for the filmmaker to mix spectacle and witty conversations about ideas and politics since there is something about a Parisian soirée which is very “theatrical.”

I was quite excited to discover in my second reading of Bastiat’s correspondence, my “cinematographic” reading of the texts, that he had attended at least three soirées while he was living in Paris in the late 1840s (two high society soirées and one more working class). This is a gift to the filmmaker because the classic Parisian soirée is well understood by cinema goers and it provides an opportunity to show a beautiful aristocratic home, with well dressed men and women, engaging in witty and sharp repartee full of interesting ideas. I think film goers expect there to be an exchange of ideas in an explicit way in such a context. A close reading of his letters showed he attended two soirées run by two women who were married to key figures in the economists’ circle: one by Anne Say who was married to Horace Say, the businessman son of the economist Jean-Baptiste Say; and Hortense Cheuvreux who was married to a wealthy manufacturer Casimir. The attendees of these soirées would have been the intellectual and commercial and political elite of Paris and it seems that Bastiat was considered by one of the women (Hortense) to be one of the stars of the show with his wicked and ribald wit, ability to sing political songs, quote poetry and plays, challenge all and sundry with his critical views of French society, and play his cello. He would have been a memorable party guest when these skills were added to his provincial charm - he spoke with a strong Gascogne regional accent and dressed like a Basque Country gentleman farmer (which he was). In my screenplay I conflated the two soirées for the sake of brevity. He would have flirted with the ladies and offended the more conservative and pompous attendees with his bawdy songs.

There was a third soirée which Bastiat attended which was organized by the radical journalist Hippolyte Castille in his large home on the rue Saint-Lazare. This shows a very different working class and socialist group in which Bastiat and Molinari also mixed. This is a chance to show the “other world” of Paris (the “upstairs, downstairs” of French politics) which was concerned with workers’ rights to form unions, participate in politics, and their opposition to censorship.

The two different kinds of soirées provides an opportunity to show the viewers something about the nature of the classical liberal perspective, namely that is both “left” and “right” depending on the context. We can show Bastiat taking a “left wing” perspective in an exchange with a conservative (perhaps Tocqueville) on the question of the workers right to form voluntary trade unions; and a “rightwing” perspective on free trade or the deregulation of industry in an argument with a socialist.

Furthermore, I used the soirée to develop the initially flirtatious relationship with Hortense into something more in order to build up this side of Bastiat’s character. (This is plausible but not strictly historically accurate).

The Indirect Expression of Ideas: Static Images of State Power

My second category for the expression of ideas in film is an indirect one in the sense that little or no words are involved. The viewer is encouraged by the filmmaker to infer certain ideas (or to understand or interpret the meaning behind certain actions or objects) simply by seeing what is put in front of them and how it is arranged. This can be done with “static images” as well as scenes involving many people but with little or no conversation or talking.

A good example of a static image which contains much useful meaning simply by existing, is the built environment of Paris in the late 1840s with the recently completed fortification wall around the city constructed under the direction of Adolphe Thiers.

|

| The military wall around Paris 1841-44 |

We can see this in the map above. With the construction of a massive fortified wall around the entire city of Paris (the red line) there were now three walls built by the state which surrounded the people of Paris and was an ever present reminder of state oppression every time one went in or out of the city when one would be inspected and taxed. The pink section was surrounded by customs (octrois) walls and gates in the 1780s to make it easier for the privatized tax-collectors (the tax “farmers”) to collect the taxes; the red stars were massive star-shaped forts which ringed the city a further distance out from the walls and were built at the same time as Thiers’ wall. The intention was to “protect” the city from another English invasion and occupation as happened after 1815; however critics at the time noted that the wall and the forts meant that 40-50,000 troops were close to the city to prevent any uprising or another revolution like in 1830, and these were the troops used in the 1848 Revolution to crush the revolt. The very existence of the two walls and the ring of forts was a constant visual reminder of the oppressive taxing and regulating powers of the French state, which intruded on the citizens’ liberty every time they went in or out of this city of one million people, and had their possessions and goods inspected, taxed, or confiscated by customs officials. The people of Paris would also see the constant patrolling of the troops along the top of the wall armed with their rifles.

Since Bastiat and his friends and colleagues were constantly going in and out of the city there is plenty of opportunities to show this oppression of the state in a very visual and even silent way. The problem for the filmmaker is to construct digitally a fair representation of these walls and forts given the fact that most of them have disappeared in the expansion and urbanisation of Paris since then.

The Indirect Expression of Ideas: Showing the everyday violence of the State

The filmmaker can also nudge or suggest to the viewer how actions of the state should be interpreted. We want to show the actions undertaken by the state and its representatives in a negative light. The inference we want viewers to make is that the state is “bad” and hurts people with its use of violence because it violates the rights to life, liberty, and property of the people. There are many ways to show this “everyday violence” of state control and repression, which was becoming worse in the years leading up to the outbreak of revolution in February 1848. One of the goals of the film is to show that conditions were reaching a breaking point in late 1847 and early 1848, that these aggressive and violents acts by the state were constant and getting worse, and that the revolution that broke out was just and necessary.

We also want to show the violence used by some socialist groups and supporters of protectionism in a negative light, that their resorting to violence harmed ordinary people as well as the free traders and economists. Their actions can been seen as are somewhat ambivalent since Bastiat and Molinari both thought the socialists and hungry citizens had legitimate grievances against the state but chose the wrong methods to change things. However, this might be too subtle and difficult to show easily in a film.

Some examples include the following:

Everyday violence by the state:

- customs inspectors at the customs walls and octrois gates forcing people to be inspected, pay taxes on the goods they were bringing into the city, or having those goods confiscated

- customs inspectors chasing and arresting smugglers, both across borders like the Spanish border near where Bastiat lived, or into the city of Paris (mainly salt, tobacco, and alcohol which were heavily taxed or were high priced government monopolies)

- police forcing their way into goguettes to stop political gatherings and singing; shutting them down

- police confiscating banned newspapers and books (mainly socialist and working class)

- police arresting draft dodgers; seeing conscripts being used to build Thiers’ wall around the city

- police harassing prostitutes, stopping them to ask for their health check books/identification; being roughed up

- police stopping workers to check their work books (which had to be stamped by their employer), otherwise they were regarded as vagrants

- police busting up meetings of workers, since trade unions were banned

- police breaking up protest marches in city when “political banquets” were banned or broken up

- police monitoring the large outdoor banquets in 1847 for any “political speech”; arrest of those making political speeches

- troops marching through the streets of Paris, along the fortress wall; Paris is an occupied city surrounded by walls and forts

Other forms of violence which are relevant to Bastiat’s activities:

- the food and bread riots in 1847; people do not understand why there are shortages and high prices; they blame hoarders and bakers and not the policy of protectionism; they smash bakery windows and take bread; they blame free trade for making things worse

The Indirect Expression of Ideas: Showing the Violence used by the State during the Revolution 1848-49:

The violence used by the state intensified during the Revolution in a very dramatic way:

- soldiers shooting protesters on the barricades in 1848; firing artillery down the streets to destroy the barricades; massive destruction of property, broken windows, and deaths; mass arrests and beatings of protesters; summary executions in the streets

- the crackdown during the period of martial law; the end of free speech and association; mass arrests and the forcible closing of the political clubs in 1849

Violence was also used by socialist and anti-free trade groups:

- violence used by communists to break up the economists’ political club meeting

- poster wars in the streets of Paris; tearing down Bastiat’s posters and trashing his magazines