“Bastiat goes to the Movies, or “Filming Freddie”: How to Popularise Economic Ideas in Film”

Created: 1 April, 2017

Revised: 15 April 2017

APEE Annual Conference, April 2017

Sheraton Maui Hotel. Maui, Hawaii

An online version of this paper is available here <davidmhart@mac.com/liberty/papers/Bastiat/FilmingFreddie/index.html>.

Author: Dr. David M. Hart.

- Director of the Online Library of Liberty Project at Liberty Fund <oll.libertyfund.org> and

- Academic Editor of the Collected Works of Frédéric Bastiat.

Email:

- Work: dhart@libertyfund.org

- Private: dmhart@mac.com

Websites:

- Liberty Fund: <oll.libertyfund.org>

- Personal: <davidmhart.com/liberty>

Bio

David Hart was born and raised in Sydney, Australia. He did his undergraduate work in modern European history and wrote an honours thesis on the radical Belgian/French free market economist Gustave de Molinari, whose book Evenings on Saint Lazarus Street (1849) he is currently editing for Liberty Fund. This was followed by a year studying at the University of Mainz studying German Imperialism, the origins of the First World War, and German classical liberal thought. Postgraduate degrees were completed in Modern European history at Stanford University (M.A.) where he also worked for the Institute for Humane Studies (when it was located at Menlo Park, California) and was founding editor of the Humane Studies Review: A Research and Study Guide; and a Ph.D. in history from King’s College, Cambridge on the work of two early 19th century French classical liberals, Charles Comte and Charles Dunoyer. He then taught for 15 years in the Department of History at the University of Adelaide in South Australia where he was awarded the University teaching prize.

Since 2001 he has been the Director of the Online Library of Liberty Project at Liberty Fund in Indianapolis. The OLL has won several awards including a “Best of the Humanities on the Web” Award from the National Endowment for the Humanities, and was chosen by the Library of Congress for its Minerva website archival project. He is currently the Academic Editor of Liberty Fund’s translation project of the Collected Works of Frédéric Bastiat (in 6 vols.) and is also editing a translation of Molinari’s Evenings on Saint Lazarus Street: Discussions on Economic Laws and the Defence of Property (1849).

David is also the co-editor of two collections of 19th century French classical liberal thought (with Robert Leroux of the University of Ottawa), one in English published by Routledge: French Liberalism in the 19th Century: An Anthology (Routledge studies in the history of economics, May 2012), and another in French called L’âge d’or du libéralisme français. Anthologie XIXe siècle (The Golden Age of French Liberalism: A 19th Century Anthology) (Paris: Editions Ellipses, 2014). He is currently a co-editor of a collection of texts on The Classical Liberal Theory of Class Analysis (Palgrave, forthcoming).

Table of Contents

Introduction

My screenplay of the life and thought of FB, naturally entitled “Broken Windows”,[1] is the product of 30 years of thinking about films historically, politically, and economically - in other words ideologically. From the time I saw Lewis Milestone’s great anti-war classic All Quiet on the Western Front (1930) on late night TV in Australia in the 1970s, to seeing Andrzej Wajda’s powerful film about the Terror during the French Revolution, Danton (1983), at the Cambridge Film Festival, to working with Marty Zupan of the IHS to develop the “Liberty in Film and Fiction Summer Seminars” throughout the 1990s (the highlight I think of that period was showing Claude Berri’s marvelous films about property rights, Jean de Florette (1986) and its sequel Manon des Sources (1986)), to teaching several courses on war films and history at the University of Adelaide,[2] I have been drawn to the power of cinema to depict political and economic ideas.

I have also been dismayed at how few of those great films were made by people who understood or believed in the free market and individual liberty. Part of Marty’s and my hopes back in the 1990s was to find future filmmakers and fiction writers who were sympathetic to free market ideas, to deepen their understanding of the political and economy theory of liberty, and thus make them better advocates for liberty in their creative work, in whatever media they might have chosen. I think we largely failed in that endeavour and the program was eventually cancelled and we both went on with our lives.

That is, until I was approached out of the blue in September 2014 by a film producer based in Florida to write a screenplay on Bastiat. I thought to myself that here was an opportunity to put into practice something I had been talking about and telling others to do for decades. The producer said he had come across the first volumes of LF’s edition of the Collected Works of Bastiat of which I was co-editor and translator.[3] I intended the screenplay to be the classical liberal or libertarian equivalent of Warren Beatty’s brilliant but very leftwing movie Reds (1981) about the life of the American communist journalist John Reed (1887–1920) before and during the Russian Revolution of 1917.[4] It is an outstanding movie on many levels and justly won 3 Oscars at the Academy Awards ceremony. It combined interesting people, radical ideas, large crowd scenes, cities in revolution, and a sense of history. If my Broken Windows could achieve a fraction of this I would be a very happy man.

Side bar: After seeing Reds I confess to having had a crush on Maureen Stapleton who played the anarchist Emma Goldman on whom I had written an undergraduate history essay. She won one of Reds’ Oscars for Best Actress in a Supporting Role.

But to cut a long story short, this “producer from Florida” motivated me to write a long screenplay on Bastiat’s life which took two years of my life. I submitted it, along with a detailed “illustrated history” of Bastiat’s life and times, in August 2016, both of which are available online.[5] To cut an even longer story shorter, it turned out to be a scam (I think) as he wanted me to fund the project with what he called “seed money,” which is how I think he made a living, flattering the people he approached, filling their heads with dreams of making a movie on their pet project, and then putting the hit on them financially. So be it.

I have no movie about FB (yet) but I learnt a great deal in working on the project, looking at history from a completely different perspective from what I had done previously. I would like to share some of those thoughts with you today, in particular the long and hard thinking I did on how to transfer ideas about economic and political liberty onto the screen.

What other Good Films and TVs can tell us about ideas and moving pictures

Some Examples to Consider

One place to start is to look at some older good (and often great) films and TV shows which deal with important ideas and try to figure out how they combined telling good stories and sending a strong political message. Below are some of my personal favourites (in chronological order of creation not merit). In quite a few instances I intensely dislike the political message they were sending but I do recognise the skill with which they were made.

Feature films:

- Fritz Lang, Metropolis (1927) - wage slavery

- Lewis Milestone All Quiet on the Western Front (1930) - how it is NOT sweet and fitting to die for the Fatherland

- Michael Curtiz, The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938) and Ridley Scott, Robin Hood (2010) - anti-tax, anti-usurper

- John Ford, The Grapes of Wrath (1940) - greed and the capitalist system destroy good hard working people

- Robert Wise, Executive Suite (1954) - resolving conflict non-violently in board room

- Akira Kurosawa, The Seven Samurai (1954) - private defence

- Michael Anderson, 1984 (1956) and Michael Radford, Nineteen Eighty-Four (1984) - Big Brother is watching us

- Stanley Kubrick, Spartacus (1960) - uprising against slavery

- Stanley Kubrick, Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (1964) - the utter madness of M.A.D.

- Bryan Forbes, King Rat (1965) - services provided by scrounger in a POW camp but hated for making a profit

- Andrew V. McLaglen, Shenandoah (1965) - anti conscription

- Robert Altman, MASH (1970) - the absurdity and carnage of war

- Mike Nichols, Catch–22 (1970) - the irrationality of the bureaucratisation of war

- William Friedkin, The French Connection (1971) - Marseilles drug trade into NYC

- Clint Eastwood, The Outlaw Josie Wales (1976) - revenge against military crimes

- Warren Beatty, Reds (1981) - commie film about ideas and revolution

- Richard Attenborough, Gandhi (1982) - salt tax, cicil disobedience, anti-empire

- Andrzej Wajda, Danton (1983) - film of ideas; speeches in court

- Miloš Forman, Amadeus (1984) - on a genius composer

- Claude Berri, Jean de Florette and Manon des Sources (1986) - importance of private property for realising personal dreams; revenge when it is frustrated

- Stanley Kubrick, Full Metal Jacket (1987) - anti basic training

- Brian De Palma, The Untouchables (1959 TV) (1987 film by ) - Elliott Ness, dreadful film about prohibition

- Steven Spielberg, Amistad (1997) - slave rebellion and court case

- Michael Apted, Amazing Grace (2006) - the heroic abolitionist movement in Britain

- Gary Ross (Suzanne Collins), The Hunger Games (2008) - depiction of black markets, state planning of production by geographic sectors; rebellion against state

- Alejandro Amenábar, Agora (2009) - a persecuted Greek female mathematician

- Mike Leigh, Mr. Turner (2014) - about a genius painter

- David O. Russell, Joy (2015) - “the Joy of Entrepreneurship”

- Nate Parker, Birth of a Nation (2016) - uprising against slavery

TV shows:

- Gene Roddenberry, Star Trek (1966- ) TV and movies - military socialism, end of scarcity

- Patrick McGoohan, The Prisoner (1967) - no one can escape the state

- Larry Gelbart, MASH (1972–83) - an anti-Vietnam war film set in Korea; mocking everyone in authority

- Antony Jay and Jonathan Lynn, Yes, Minister (1980–84) and Yes, Prime Minister (1986—88) - every episode a lesson in Pubic Choice economics

- Aaron Sorkin, The West Wing (1999) TV - all well-meaning lovable people doing horrible things (in our eyes only)

- House of Cards (UK TV 1990 by Andrew Davies; US TV 2013 by Beau Willimon) - TV series shows corrupt and murderous politicians

Why are there so few Pro-Liberty or Pro-Free Market Films and TV Shows?

Some preliminary thoughts

The Long History of Popularising Economics in Print

My paper on “From Say to Jasay via Bastiat”[6]

In the modern period:

- Henry Hazlitt

- Milton Friedman

- Don Boudreaux and Café Hayek

- many free market bloggers today; a new “Golden Age” for print (but not yet for film/video)

The “Rhetoric” and “Aesthetics” of Economics and Liberty

D. McCloskey’s idea of the “rhetoric of economics” (in words and equations)[7]

There needs to be an “aesthetic of economics and liberty” which includes images like art, video, statues, symbols.

There is a Long History of the Iconography of Liberty

- the Phrygian cap

- Marianne[8]

- Delacroix’s “Liberty Leading the People on the Barricades” (1830)

- the Statue of Liberty (a conservative depiction of Marianne)[9]

My collection of “Images of Liberty and Power” [10]

Is the problem with the filmmakers?

- filmmakers have traditionally been hostile to FM ideas (like most intellectuals in the 20thC)

- have filmmakers with pro-market ideas just been bad filmmakers? e.g. the Atlas Shrugged debâcle: Atlas Shrugged trilogy Part I (2011), Part II (2012), and Part III (2014)

- perhaps pro-market filmmakers haven’t figured things out yet

Or is it with the content?

- filming peace and prosperity is intrinsically boring: lack of conflict and drama

- Perhaps it is better to achieve the same purpose indirectly, have market activities as a backdrop to other human activities/conflicts

Positives vs. Negatives

Maybe it is too hard and/or boring to make a film about “a positive”, i.e. free markets are good. Perhaps we should stick to making films about a “negative”, i.e. what happens in the absence of peace and freedom:

- absence of free markets, presence of black markets (The Hunger Games), e.g alcohol prohibition (The Untouchables and The French Connection), drug war/prohibition, food shortages

- absence of peace, great tradition of anti-war films (AQWF, MASH, Catch–22) - do libertarians have anything new to say about this?

- absence of justice, e.g. false imprisonment, police brutality, corruption of justice system, tax rebellions (Gandhi and salt tax), slavery (Spartacus, Amazing Grace, Birth of a Nation)

Depictions of dystopias are usually more interesting and moving than depictions of utopias (1984, The Prisoner).

Important role played by black humour, satire; mocking power, corruption, hypocrisy, stupidity (Catch–22, Yes, Minister, MASH, Dr. Strangelove)

The Four Challenges in “Filming Freddie”

I think there are four challenges to consider:

- the challenge of filming a revolution, especially in an old city which doesn’t exist anymore

- the challenge of making pro-liberty ideas interesting on film

- the challenge of making the main character interesting enough for the viewer to pay %8 and watch a 2 hour movie

- the challenge of showing how markets work and what happens when they don’t or aren’t allowed to

(1) The Challenge of Filming a Revolution

Why are there so few movies about Revolution, especially the 1848 Revs?

- the Revolutions of 1848 did lead to some significant liberal reforms throughout Europe even though technically they were “defeated”

- the historiography has been dominated by leftist historians; the role CLs like FB played has been totally ignored

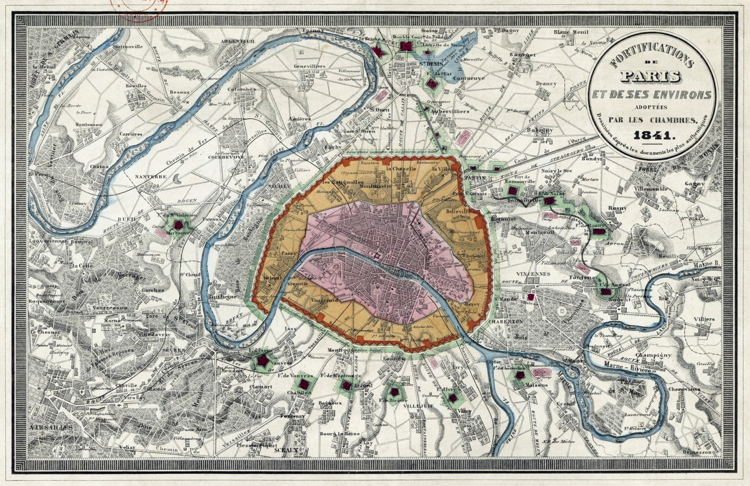

The problem of sets and costumes in historical dramas:

- very (too?) expensive to make

- old Paris no longer exists

- the customs and military walls around Paris no longer exist

- sheer cost of recreating this (CGI?)

- the problem of recreating crowd scenes

How much background knowledge do viewers need in order to make sense of the chaos and complexity of revolution?

(2) The Challenge of Making Ideas about Liberty interesting to the lay person

How much background knowledge do viewers need in order to make sense of the ideological conflict going on before them?

The problem of “speechifying” and boring the viewer.

The need to make ideological conflict personal not abstract and theoretical.

- friends/lovers/family on opposite sides to a conflict

- threading together personal conflict, political conflict, violence, and ideas as the motive behind it all

(3) The Challenge of Making Freddie interesting (to non-economists)

Do good movies have to have violence and sex? What if FB had no love life? Do we invent one for him?

- what if economists and historians are essentially boring people?

Do good movies have to have a likable/attractive (either good or bad) main character?

What is his “save the cat” moment (an even in the first 5–10 minutes of the film which makes the viewer want to see more of him)?[11]

(4) The Challenge of Showing Markets at Work

Can economic ideas be depicted in a visual medium like film? or is economics a “verbal” discipline (even if it does have a “rhetoric” and not an “aesthetic” yet?

Two early attempts to create an illustrated version of two important CL books:

- the illustrated Bastiat’s The Law (FEE, late 1940s)[12]

- the illustrated Hayek’s The Road to Serfdom in Cartoons (Readers; Digest, 1945)[13]

A more recent attempt:

- the Keynes/Hayek Rap video - John Papola, Fear the Boom and Bust (2010)

Is buying and selling stuff peacefully in markets essentially boring (to watch)? Only interesting when they don’t work or are prevented from working (by the state)

- better implying not showing economic matters directly; not talking about them

- economics as background to other things going on which are more interesting

- conflict comes about between the state and some of the economic actors

- food riots/hunger/unemployment/strikes often shown in film but “capitalism” is usually blamed

- the “feeding of Paris”; great markets needed to feed a city of 1 million people

- printing books and magazine, handing them out on streets

- smuggling wine, tobacco, salt through the customs barriers

Show onscreen how FB went about popularising economic ideas

- his “rhetoric of liberty” using French lit. to tell stories and “economic parables”;

- little plays and dialogs;

- satire and mocking tone; calling “a spade a spade”[14]

- singing banned political songs in goguettes

- show him acting these stories out in his apartment or at the salons before he writes them down formally

Some Specific Thoughts about “Filming Freddie”

Do good movies have to have violence and sex? Maybe.

Do good movies have to be beautiful to look at? I would say definitely yes.

It is hard to make a bad looking film with 1848 Paris as the backdrop

Great images to use in a film of his life in Paris 1845–50. See my “Illustrated History of the Life and Times of FB”.

- walls surrounding Paris - customs and military

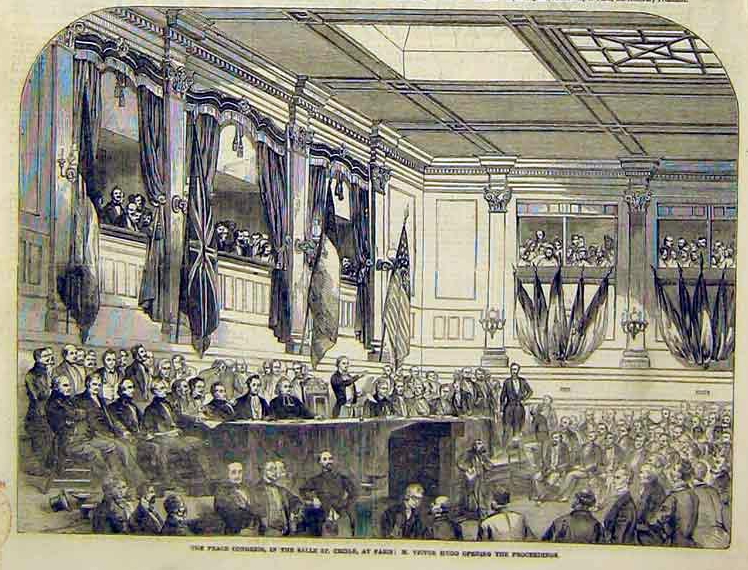

- massive public meetings which are contentious; heckling; booing; for Free Trade Association, Peace Congress

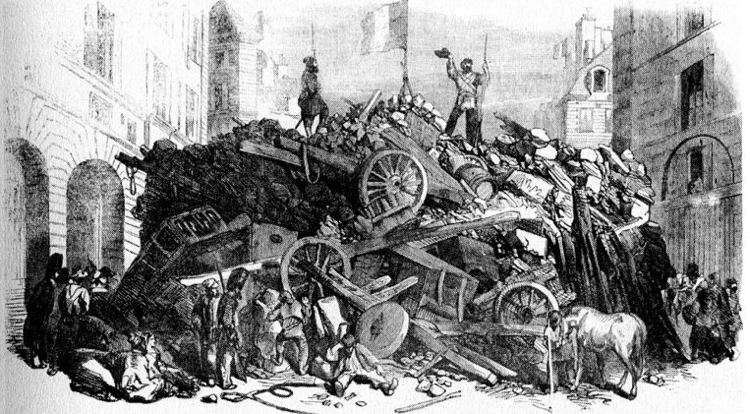

- barricades in streets of Paris; troops using artillery

- violence by socialists against Club de la Liberté du travail

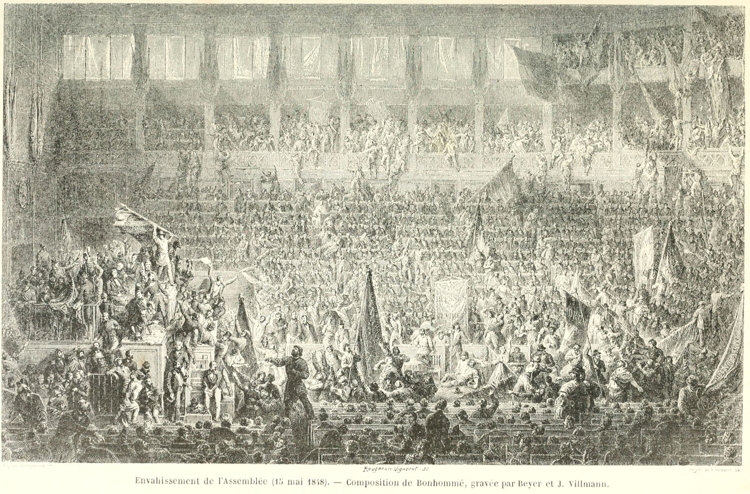

- invasion, attempted coup in Chamber in May 1848

- illegal political meetings busted up by police - the outdoor political banquets of 1847, and goguettes

- witty salons run by smart, rich women in fancy dresses

There are whole books devoted to the history and cultural of building and manning the barricades in Paris which can be used to make these scenes historically accurate. For example, Mark Traugott, The Insurgent Barricade (2010).[15]

The Problem of Violence

We are “lucky” in this respect since FB lived through a bloody and violent revolution and saw things at first hand.

- there was considerable violence in Paris streets in Feb and June 1848 and he wrote a couple of letters about what he saw and did on the streets; getting caught in the crossfire, helping injured to safety

- he was in Chamber when supporters of the socialist Louis Blanc broke in and tried to stage a coup; (he later was one of the few Deputies to defend Blanc)

- he attended public meetings which were broken up by communist thugs (the Political Clubs of Feb/March/April 1848)

- there were some riots in the streets over high food prices, especially bread

Opportunities to show the “everyday violence” of state control and repression

- customs inspectors; customs wall, octrois gates

- conscripts into army; used to build Thiers’ wall; ring of forts around Paris

- chasing and arresting smugglers

- health inspectors harassing prostitutes

- police invading goguettes and shutting them down

- soldiers shooting protesters on the barricades in 1848

- courtroom drama: trial and conviction of workers who formed union; FB as magistrate being lenient on smugglers, draft dodgers

The Problem of Turning Invisible Ideas into Visible Action

The temptation is to have too much talking as the way to transmit ideas. (And I am so easily tempted!) The problem is to show conflict either arising out of the conflict between people with opposing ideas, or to show the ideas as a backdrop to the action

- big public meetings which were contentious and provoked some violence in retaliation (more “broken windows”); free trade meetings with 2,000 people in huge halls; interjections and heckling

- the “poster wars” on the streets of Paris; with the breakdown of political control in Feb. 1848 there was de facto freedom of speech; blossoming of political clubs and press; violence came from hecklers in audience, beating up one’s political opponents; pulling down their posters and trashing their books and newspapers

- the attempted take over of the Chamber by socialists in May 1848

- the crackdown during the period of martial law; end of free speech and association

FB attended two salons run by wealthy CL supporters (Cheuvreux, Say); good opportunity to show off his wit and musical skill with repartee; flirting with the ladies; offending the conservatives and the pompous with his bawdy songs; attended third salon run by radical republicans and socialist - chance to show the “other world” of Paris (the “upstairs, downstairs” of French politics and how FB and GdM straddled that)

The Problem of Sex and Romantic Attraction

There was no sex we know of, but some flirtation with a wealthy woman who ran a Paris salon (Hortense Cheuvreux); unrequited love is hinted at.

(See above on the salons he attended.)

The Problem of getting to know and liking Freddie

Do good movies have to have a likable/attractive (either good or bad) main character? I would say yes.

- “save the cat” moment to suck audience in; get them to commit emotionally to watching the next 90 mins

- my “save the cat” moment was “invented” by me and came on the streets of Paris in June 1848 when he and an office boy were handing out their magazine to people on the barricades; boy gets killed and FB tries to save him

FB has considerable drama and conflict in his personal life, as well as a personal “dramatic” and radical style:

- dying of incurable cancer, race against time to achieve something; struggling to give major speech in Chamber with a failing voice

- frustration at starting a FFTA but having to cancel it when Rev breaks out

- dramatic opposition with socialists in street and in Chamber

- late blossoming as theoretical economist, he has something to say and wants to say say it before it is too late

- his radical (proto-Austrian and Public Choice) ideas opposed by his colleagues; even his colleagues and friends eventually turn against him (or turn their backs on him)

His personal idiosyncrasies and radicalism make him interesting as a person (his “dramatic style”)

- idiosyncratic and individualistic personal style: clothes, accent; ironic, mocking, “Rabelaisian” (GdM) wit; anger at injustice

- star of two Paris salons; chance to show off his wit, musical skills

- wrote ES with lots of dialog; little plays, even plays within plays; calls out for reenacting on screen

- dramatic farewell to his street fighting friends at lunch at Butard lodge

Endnotes

-

Named after, of course, the first chapter of Bastiat’s last work WSWNS (July 1850) “The Broken Window”. It is also a reference to the shattered windows caused by French troops called in to quell the uprising in February and June 1848 when they fired artillery down the streets of Paris to clear away the hastily built barricades of the revolutionaries. See Mark Traugott’s book about barricades. ↩

-

One course I taught for 10 years was called “Responses to War: An Intellectual and Cultural History” (1989–1999) in the course of which I showed nearly 100 war films to my students. See the course guides for the films here http://davidmhart.com/liberty/WarPeace/WarFilms/FilmGuides.html and some video clips from some of the films http://davidmhart.com/liberty/VideoClips/index.html. ↩

-

The Collected Works of Frédéric Bastiat. In Six Volumes (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 2011-), General Editor Jacques de Guenin. Academic Editor Dr. David M. Hart. Vol. 1: The Man and the Statesman. The Correspondence and Articles on Politics (2011); Vol. 2: “The Law,” “The State,” and Other Political Writings, 1843–1850 (2012); Vol. 3: Economic Sophisms and “What is Seen and What is Not Seen” (2017). ↩

-

See his famous account Ten Days That Shook the World (1919) which many classes on the Russian Revolution still teach today. ↩

-

See at my personal website “’Broken Windows’. A Screenplay about the Life and Work of Frédéric Bastiat (1801–1850)” <davidmhart.com/liberty/FrenchClassicalLiberals/Bastiat/Screenplay/BrokenWindows2.html> with an accompanying “Illustrated History of the Life and Work Frédéric Bastiat” <davidmhart.com/liberty/FrenchClassicalLiberals/Bastiat/Screenplay/BrokenWindows.html>. ↩

-

David M. Hart, “Negative Railways, Turtle Soup, talking Pencils, and House owning Dogs: “The French Connection” and the Popularization of Economics from Say to Jasay,” (Sept. 2014) <davidmhart.com/liberty/Papers/Bastiat/BastiatAndJasay.html>. A shortened version of this paper was published in the “Symposium on Anthony de Jasay” in The Independent Review, vol. 20, no. 1, Summer 2015, “Broken Windows and House-Owning Dogs: The French Connection and the Popularization of Economics from Bastiat to Jasay,” pp. 61–84. ↩

-

Donald N. McCloskey, The Rhetoric of Economics (Madison, Wisconsin: The University of Wisconsin Press, 1985). ↩

-

Maurice Agulhon, Marianne into Battle: Republican Imagery and Symbolism in France, 1789–1880, translated by Janet Lloyd. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1981). ↩

-

Marvin Trachtenberg, The Statue of Liberty (New York, Viking Press, 1976). ↩

-

See the collection of “Images of Liberty and Power” in the Online Library of Liberty http://oll.libertyfund.org/images. ↩

-

Blake Snyder, Save the Cat! The Last Book on Screenwriting You’ll Ever Need (2005) and Save the Cat! Goes to the Movies (2007). ↩

-

The illustrated Bastiat’s The Law (FEE, late 1940s). Online http://davidmhart.com/liberty/FrenchClassicalLiberals/Bastiat/Books/Sampling_TheLaw/Bastiat_IllustratedTheLaw.html. ↩

-

The illustrated Hayek’s The Road to Serfdom in Cartoons (Readers; Digest, 1945). Online http://davidmhart.com/liberty/GermanClassicalLiberals/Books/Hayek/IllustratedRoadSerfdom/index.html. ↩

-

David M. Hart, “Bastiat’s Rhetoric of Liberty: Satire and the Sting of Ridicule”,” in Editor’s Introduction to The Collected Works of Frédéric Bastiat. Vol. 3: Economic Sophisms and “What is Seen and What is Not Seen” (Liberty Fund, 2017), pp. lviii-lxiv, and my paper "Opposing Economic Fallacies, Legal Plunder, and the State: Frédéric Bastiat’s Rhetoric of Liberty in the Economic Sophisms (1846–1850)”, Paper given at the History of Economic Thought Society of Australia (HETSA) annual meeting, RMIT Melbourne, Victoria, July 5–8, 2011 http://davidmhart.com/liberty/Papers/Bastiat/EconomicSophisms/Hart_BastiatsSophismsAug2011.html. ↩

-

Mark Traugott, The Insurgent Barricade (University of California Press, 2010). ↩