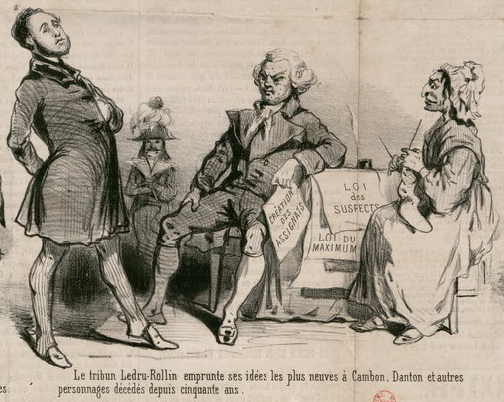

[The cartoonist “Cham” ridicules the plans of the French socialists like Ledru-Rollin who dreams of a new socialist Terror. See, Amédée de Noé, dit Cham, “Ce qu’on appelle des idées nouvelles en 1848” (Paris?: Imp. Aubert & Cie, 1848).]

Before turning to the criticism of socialism by the French political economists it is important to understand what the socialist critique of wage labour, private property, and the free market societies actually was.

During the 1830s and 1840s the basic socialist criticisms of the free market were first expressed at some length and with some coherence, and solutions proposed (usually involving state ownership, regulation of economic activity, and transfer payments to the poor and unemployed) which would remain essentially the same for the next hundred years or so. These criticisms can be summarized as economic, moral/philosophical, and political in nature, and were usually articulated in the various “Manifestos” which were issued by socialist groups, such as Victor Considerant’s “Manifesto” of 1847, Karl Marx’s “Communist Manifesto” of February 1848, and Ledru-Rollin’s “Manifesto for the Mountain Party” of December 1848.

More extensive criticism of the free market can be found in their longer works such as

- Louis Blanc, Organisation du travail. Association universelle. Ouvriers (1841) in French HTML and English HTML ; and Le Socialisme. Droit au travail, réponse à M. Thiers (1848)

- Victor Considerant, Principes du Socialisme. Manifeste de la Démocratie au XIXe siècle (1847) in French HTML and English HTML ; and Droit de propriété et du droit au travail (1848)

- Joseph Proudhon, Qu’est-ce que la propriété? ou Recherches sur le principe du Droit et du Gouvernement (1840) in French HTML and English HTML ; Système des contradictions économiques, ou philosophy de la misère (1846); Le droit au travail et le droit de propriété (1850);

[Proudhon believes “property is theft”]

These criticisms can be summarized as follows:

- Economic Criticism

- the free market and bourgeois society is based upon private property which is unjust; the exclusive ownership of things, especially land, was a form of “theft” against those who did not own property, such as the ordinary worker. Hence Proudhon’s famous dictum “la propriety, c’est le vol” (property is theft)

- wage labour leads to the “exploitation” of workers because they do not receive the full value of their labour, since some of it is withheld as “profit” by the factory owner

- wage labour (especially factory work) “alienates” the workers from both the things they create and their full potential (this objection was put forward most forcibly by Karl Marx)

- profit, interest, and land rent are unjust because they are “unearned” as the factory owner, capitalist or bank, and landowner do not “labour” to produce anything of value (important because most socialists believed that only “labour” produces wealth, hence if one did not “labour” then one inevitably exploited those who did)

- competition has disastrous consequences for the workers in that they compete for scarce jobs and thus drive down the level of wages, thus becoming poorer and poorer (immiseration) under capitalism

- there is a tendency towards the formation of monopolies which ruthlessly exploit consumers by charging excess profits and driving their competitors (and their workers) out of business, hence Louis Blanc’s idea that competition was a form of “murder” of workers

- there are periodic economic crises which adversely affect the poor working class who are least able to survive during periods of unemployment

- the emergence of international capitalism leads to “free trade”, global competition, and the destruction of national industry

- Moral/Philosophical Criticism

- there is increasing inequality between the wealthy capitalists and the “bourgeoisie” on the one hand, and ordinary working people on the other

- capitalism is “heartless” as a result of the selfish behaviour of individuals and the drive to get profits

- there is the destruction of traditional communities as people seek work in the large cities and industrial towns and leave the countryside and smaller towns

- Political Criticism

- the growing power and wealth of the “capitalist class” (the bourgeoisie) within the political system allows them to further their own ends at the expense of the weaker or non-voting working class

- there is an unequal relationship between employers and labor, especially when it comes to bargaining for wages and conditions

- the traditional “nuclear family” perpetuates bourgeois thought and behaviour

The political economists gradually realized the threat the socialists posed, both intellectually and increasingly politically after 1845 and addressed them accordingly in an outpouring of books and pamphlets, which unfortunately having been largely forgotten today:

- Charles Dunoyer, La Liberté du travail (1845): literally on “the liberty of working” as opposed to the socialist notion of “the right to work (or right to a job)” – in French in facs. PDF via this page

- Adolphe Thiers, De la propriété (1848) – (en français) in HTML and facs. PDF ; and in English with a slightly different title, The Rights of Property: A Refutation of Communism & Socialism (1848) in HTML and facs. PDF

- Léon Faucher, Du droit au travail (1848)

- Michel Chevalier, Lettres sur l’Organisation du travail (1848) [in French facs. PDF ] and L’économie politique et le socialisme (1849) [in French facs. PDF ]

- Frédéric Bastiat’s series of 12 anti-socialist pamphlets (1848-1850) – [these will be discussed in more detail in a future post]

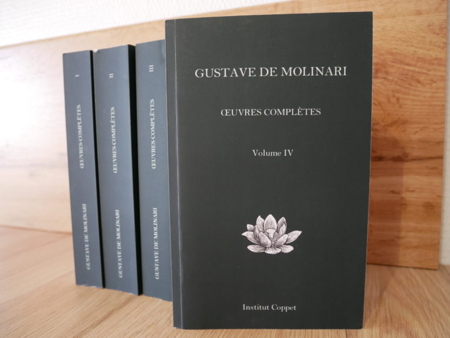

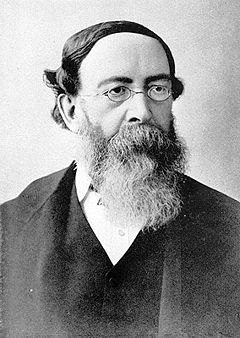

- Gustave de Molinari, Les Soirées de la rue Saint-Lazare; entretiens sur les lois économiques et défense de la propriété (1849) [ HTML and facs,. PDF in French; draft English trans. at the OLL]

- Bastiat and Proudhon, Gratuité du crédit (Oct. 1849 – Feb. 1850) – in French [ HTML and facs. PDF ]

- Dictionnaire de l’économie politique (1852-53): with many articles on socialism and socialist theorists which was designed to be a compendium of criticism of socialist and other forms of interventionism by the state – in French facs. PDF

[Molinari on the other hand believes socialists will inevitably fail because they ignore “economic laws”]

Their rebuttal of socialist criticisms of the free market and their concerns about why socialism would fail in practice were extensive and detailed. The economists argued that the socialists ignored or misunderstood the following problems:

- the incentive problem: communally organised living and working arrangements destroy incentives for individuals to work hard when all “profits” go to the community to be equally distributed

- the division of labour problem: people with key skills (managerial, financial, technical, organisational, entrepreneurial) need to be paid for their extra contribution to the productive process

- the risk problem: all economic activity involves risks (loss, miscalculation, natural disaster) which needs to be rewarded

- the injustice of expropriation: to create any socialist system of production existing justly owned property has to be confiscated and given to new communally organised groups

- the individual liberty problem: many socialists modeled their proposed new communal organisations on the army or a government bureaucracy (like the post office); these organisations would be deliberately hierarchical, with command from above, communal eating and sleeping arrangements, and general loss of individual choice and liberty

- the human nature problem: socialists assumed that human nature is not fixed but malleable, that it is possible to create a” new socialist man” who would not be selfish or acquisitive; the economists believed humans were social but not communist, self-interested (broadly understood) not willing to sacrifice their interests to the community’s; and that people had vastly different tastes, preferences, skills, and interests which would and not be taken into account under socialism

- the public choice problem – rulers were not disinterested parties but had own agendas

- the problem of ignoring economic laws – the economy is governed by economic “laws” (such as the law of supply and demand) which cannot be ignored or wished away by well meaning people

What is striking to the modern reader, are the similarities between both the socialist critique of free markets and the economists’ defense of them of the 1840s and those of today. It would seem that we collectively have remembered nothing of them and thus have learned nothing from them. The major differences in my view is the Hayekian notion that free market prices carry vital information about the relative scarcity of goods and services and the changing demands of both consumers and other producers which are all crucial factors in entrepreneurs knowing what to produce, when and where. This idea is only rudimentary at best or completely absent from the political economists’ understanding of the problems faced by socialist production. On the other hand, the modern day socialists have greatly expanded the Malthusian critique of the ability of free markets to feed and clothe the poorest members of society, and applied this to a critique of “capitalism’s” over-exploitation and thus depletion of resources, its pollution of the environment, and the problem of “global warming” (sorry, “climate change”). It would seem that the proposed “Green New Deal” is just another in the long list of attempts by socialists to centrally plan the economy and thus avoid the waste and destruction inherent in free markets.

The socialist challenge in the 1840s was eventually put down by brutal police action in 1849 and many, like Louis Blanc, were imprisoned or sent into exile. However, their ideas were not so easily defeated. Some of their ideas would be taken up by the soon to be (self-)appointed Emperor Napoleon III and imposed from above in what would become a newly invigorated form of French “dirigisme” or “state socialism”. “Socialism proper” (in the form of working class socialist or labour parties) would reemerge in the 1880s and 1890s and would be met again by the French political economists in another round of anti-socialist publishing activity. This will be the topic of a future post.

On Cham’s cartoon see my talk on “Unfortunately, Hardly Anyone Listens to the Economists”: The Battle against Socialism by the French Economists in the 1840s.