[Delacroix’s “Liberty leading the People on the Barricade” (1830)]

Date: 20 May, 2021

Revised: 22 Apr. 2022

[Note: This post is part of a series on the History of the Classical Liberal Tradition]

An Essential Reference Work

An accessible and very comprehensive introduction to CL /Libertarianism can be found in the Cato Institute’s The Encyclopedia of Libertarianism, ed. Ronald Hamowy (Los Angeles: Sage, 2008. A Project of the Cato Institute). It contains dozens of short entries on key individuals, policies, intellectual movements, and ideas and concepts. It is available online free of charge here. The abbreviation EoL is used below for this reference.

I. Begin with an Overview

I suggest you begin with a couple of overviews :

On the state of liberty in the world today, see The Human Freedom Index 2021. A Global Measurement of Personal, Civil, and Economic Freedom. Ian Vásquez, Fred McMahon, Ryan Murphy, and Guillermina Sutter Schneider (Cato Institute and Fraser Institute, 2021). Online – Human Freedom Index: 2021 | Cato Institute and PDF. Note: the Introduction to the volume is well worth reading. Also, that Australia has been dropping in the ranks.

Then browse around the articles in the EoL according to your whims and tastes. I have reorganized the entries into the following categories to make browsing a bit easier (see my webpage with links to the EoL site here:

- People

- Ideas

- Movements and Ideas: both Liberal and Anti-Liberal

- Historical Events and Documents

- Policy Issues (specific)

- Other General Topics of Interest

II. Then Delve into some Primary Sources

You should read some of the original texts for yourself and not just depend on what others have said about them. Here is my personal selection of some of “The Great Books of Liberty”.

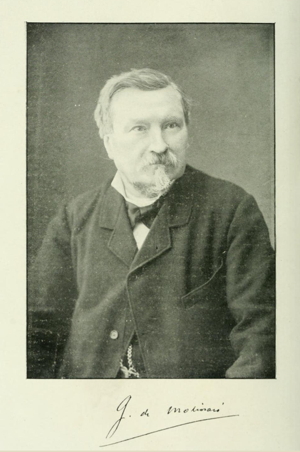

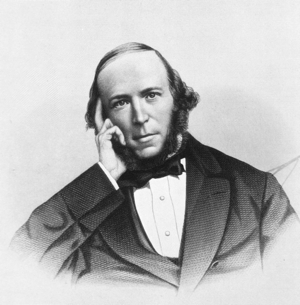

I believe that liberalism can be divided into three main types according to how consistent it is in applying the principles of individual liberty, self-ownership, and non-coercion to the areas of social/individual liberty, political liberty, and economic liberty. Thus there is “radical” liberalism, “moderate” liberalism, and “new” or “neo” liberalism (or what I would call partial or inconsistent liberalism). My own preference is the radical liberalism of Frédéric Bastiat, Herbert Spencer, and Gustave de Molinari.

A good sample of classical liberal work is E. K. Bramsted and K. J. Melhuish, Western Liberalism: A History in Documents from Locke to Croce (New York: Longman, 1978).

For a broader sampling of classical liberal writing on various topics, see my compilation of 600 Quotations about Liberty and Power: The Collected Quotations from the Online Library of Liberty (2004-2018), the table of contents of which (with links to the full quotes and my commentary) can be found on my website here.

In my view I think that there are 5 important periods in the development of classical liberalism / libertarianism:

- its “pre-history” during the classical, medieval, and reformation/renaissance periods when some of the key ideas evolved but they were not brought together into a coherent “worldview”

- the 17th century, particularly in England with the emergence of the Levellers and other supporters of Parliament against the growing power of the monarchy, during the Civil Wars and Revolution and then the Exclusion Crisis leading up to the Revolution of 1688

- the 18th century Enlightenment in France, Scotland, England, and North America which culminated in the American and French Revolutions and the creation of the first limited, constitutional, “liberal” government in the world

- the 19th century during which “classical liberalism” emerged and the most comprehensive liberal reforms (political, economic, and social) were introduced

- the decline and “long sleep” of CL during the 1st three quarters of the 20th century before its re-emergence in the 1970s and 1980s with the modern “libertarian” movement in the U.S. and elsewhere.

See below for a more detailed list and description of some of the key figures.

Modern Works on CL Theory

But enough of history! What are modern day CLs and Libertarians saying? See the following recent works to get an idea:

- Peter J. Boettke, The Struggle For A Better World (Arlington, Virginia: Mercatus Center, 2021). Online at The Struggle for a Better World | Mercatus Center: F. A. Hayek Program.

- Visions of Liberty. Edited by Aaron Ross Power and Paul Matzko (Washington, D.C.: Cato Institute, 2020) Online

- George F. Will, The Conservative Sensibility (Hachette Books, 2019).

- Deirdre McCloskey, Why Liberalism Works: How True Liberal Values Produce a Freer, More Equal, Prosperous World for All (Yale University Press, 2019).

- Richard Ebeling, For a New Liberalism (American Institute for Economic Research, 2019).

- Eamonn Butler, School of Thought: 101 Classical Liberals (IEA, 2019).

- Eric Mack, Libertarianism (Key Concepts in Political Theory. Polity, 2018).

- [Brennan] The Routledge Handbook of Libertarianism. Edited by: Jason Brennan, Bas van der Vossen, and David Schmidtz (New York : Routledge, 2018).

- [Zywicki] Research Handbook on Austrian Law and Economics. Edited by Todd J. Zywicki and Peter J. Boettke (Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar, 2017).

- [Boettke, Coyne, and Storr] Interdisciplinary Studies of the Market Order. New Applications of Market Process Theory. Edited by Peter J. Boettke, Christopher J. Coyne, and Virgil Henry Storr (London: Rowman & Littlefield, 2017).

- Steven Horwitz, Hayek’s Modern Family: Classical Liberalism and the Evolution of Social Institutions (Palgrave Macmillan, 2015).

- Edward P. Stringham, Private Governance: Creating Order in Economic and Social Life (Oxford University Press, 2015).

- Peter T. Leeson, Anarchy Unbound: Why Self-governance Works Better than You Think (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014).

- George H. Smith, The System of Liberty: Themes in the History of Classical Liberalism (Cambridge University Press, 2013).

- Chandran Kukathas, The Liberal Archipelago: A Theory of Diversity and Freedom (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003).

And for an Australian perspective:

Chris Berg, The Libertarian Alternative (Melbourne University Press, 2016).

David Kemp’s trilogy (Melbourne University Press) on the the “moderate” or “compromised” liberalism which emerged in Australia:

1. The Land of Dreams: How Australians Won Their Freedom, 1788–1860 (2018)

2. A Free Country: Australia’s Search for Utopia, 1861-1901 (2019).

3. A Liberal State: How Australians Chose Liberalism over Socialism 1926–1966 (2021)

David Llewellyn , AUSTRALIA FELIX: Jeremy Bentham and Australian colonial democracy (PhD. thesis, University of Melbourne, July 2016).

My own rather pessimistic views can be found in this blog post:

- “The State of the Libertarian Movement after 50 Years (1970-2020): Some Observations” Reflections on Liberty and Power (25 March, 2021) here.

Some older but still value works include:

- Alan Ryan, The Making of Modern Liberalism (Princeton University Press, 2012).

- José G. Merquior, Liberalism: Old and New (Boston: Twayne Publishers, 1991).

- Stephen Macedo, Liberal Virtues. Citizenship, Virtue, and Community in Liberal Constitutionalism (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1990).

- Anthony Arblaster, The Rise and Decline of Western Liberalism (Oxford: Blackwell, 1984).

- Murray N. Rothbard, For a New Liberty: The Libertarian Manifesto. Revised edition. (New York: Collier Macmillan, 1978).

- David L. Norton, Personal Destinies (Princeton University Press, 1976).

- Robert Nozick, Anarchy, State, and Utopia (New York: Basic Books, 1974).

Other Recommended Works

Works by the Great CLs

John Stuart Mill, On Liberty (1859), in John Stuart Mill, The Collected Works of John Stuart Mill, Volume XVIII – Essays on Politics and Society Part I, ed. John M. Robson, Introduction by Alexander Brady (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1977).

F.A. Hayek, “The Intellectuals and Socialism,” The University of Chicago Law Review (Spring 1949), pp. 417-420; reprinted in Studies in Philosophy, Politics, and Economics (University of Chicago Press, 1967), pp. 178-194.

Friedrich Hayek, Law, Legislation and Liberty: A new statement of the liberal principles of justice and political economy 3 vols. (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1973-79)

My list of “One Volume Surveys of Classical Liberal Thought”:

First wave:

- Wilhelm von Humboldt, Ideen zu einem Versuch, die Gränzen der Wirksamkeit des Staates zu bestimmen (Ideas presented in an Attempt to determine the Limits of State Activity) (1792, 1854)

- Benjamin Constant, Principes de politique, applicables à tous les gouvernemens représentatifs (The Principles of Politics which are applicable to all Representative Governments) (1815)

- Gustave de Molinari, Les Soirées de la rue Saint-lazare (Evenings on Saint Lazarus Street) (1849)

- Herbert Spencer, Social Statics (1851)

- JS Mill, On Liberty (1859)

- Herbert Spencer, The Principles of Ethics (1879)

- Bruce Smith, Liberty and Liberalism (1888)

Second wave (20th century before the modern libertarian movement emerged)

- Ludwig von Mises, Liberalismus (Liberalism) (1927)

- Friedrich A. Hayek, The Constitution of Liberty (Chicago: Henry Regnery, 1960)

- Milton Friedman (with the assistance of Rose D. Friedman), Capitalism and Freedom (University of Chicago, 1962)

Third wave (which coincided with the emergence of the modern libertarian movement):

- John Hospers, Libertarianism – A Political Philosophy for Tomorrow (Los Angeles: Nash, 1971)

- David Friedman, The Machinery of Freedom: Guide to a Radical Capitalism (1973)

- Murray N. Rothbard, For a New Liberty (New York: Macmillan, 1973)

- Milton Friedman and Rose Friedman, Free to Choose: A Personal Statement (Harcourt, Brace, Jovanovitch, 1980; Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1980)

Three Aussie Radical Liberals

William Edward Hearn, Plutology or the Theory of the Efforts to Satisfy Human Wants (Melbourne: George Robertson, 1863; London: Macmillan and Co., 1864). Online.

Bruce Smith, Liberty and Liberalism: A Protest against the growing Tendency toward undue Interference by the State, with Individual Liberty, Private Enterprise and the Rights of Property (1887; reprinted 2005 by the CIS) Bio of Arthur Bruce Smith (1851-1937) and the book online

Bob Howard et al. who wrote the Workers Party Platform (1975) Online.

On CL natural rights theory:

- Douglas B. Rasmussen and Douglas J. Den Uyl, Liberty and Nature: An Aristotelian Defense of Liberal Order (La Salle, IL: Open Court, 1991).

- Douglas B. Rasmussen and Douglas J. Den Uyl, Norms of Liberty: A Perfectionist Basis for Non-Perfectionist Politics [hereinafter NOL] (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2005), especially chapters 4 and 11; and

- Douglas J. Den Uyl and Douglas B. Rasmussen, The Perfectionist Turn: From Metanorms to Metaethics (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2016).

- Douglas B. Rasmussen and Douglas J. Den Uyl, The Realist Turn: Repositioning Liberalism (Palgrave Macmillan, 2020).

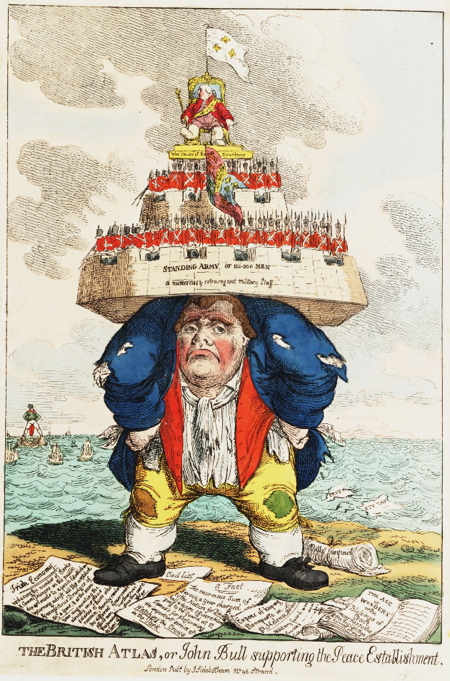

Works on history and the history of ideas:

Bernard Bailyn, The Ideological Origins of the American Revolution. Enlarged Edition (The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1992). 1st ed. 1967. Especially chap. III “Power and Liberty: A Theory of Politics,” pp. 55-93.

Bernard Bailyn, “The Central Themes of the American Revolution: An Interpretation,” in S. Kurtz and J. Hutson, eds., Essays on the American Revolution (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1973), pp. 26–27.

Jerome Blum, The End of the Old Order in Rural Europe (Princeton University Press, 1978).

Joseph Hamburger, James Mill and the Art of Revolution (Yale: Yale University Press, 1963).

Joseph Hamburger, Intellectuals in Politics: John Stuart Mill and the Philosophic Radicals (Yale: Yale University Press, 1965).

Theodore S. Hamerow, The Birth of a New Europe: State and Society in the Nineteenth Century (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1983).

Jonathan Israel, Revolutionary Ideas: An Intellectual History of the French Revolution from The Rights of Man to Robespierre (Princeton University Press, 2014).

Jonathan Israel, The Expanding Blaze: How the American Revolution Ignited the World, 1775-1848 (Princeton University Press, 2017).

Jonathan Israel, The Enlightenment That Failed: Ideas, Revolution, and Democratic Defeat, 1748-1830 (Oxford University Press, 2019).

Robert Kelley, The Transatlantic Persuasion: The Liberal-Democratic Mind in the Age of Gladstone (New York: Alfred A. Knopf. 1969).

McCloskey’s “Bourgeois trilogy” on bourgeois virtues, dignity, and equality:

- Deirdre N. McCloskey, The Bourgeois Virtues : Ethics for an Age of Commerce (University of Chicago Press, 2006).

- Deirdre N. McCloskey, Bourgeois Dignity: Why Economics Can’t Explain the Modern World (University of Chicago Press, 2010).

- Deirdre N. McCloskey, Bourgeois Equality: How Ideas, Not Capital or Institutions, Enriched the World (University of Chicago Press, 2016).

Robert Nisbet, “The Social Impact of the Revolution.” In America’s Continuing Revolution: An Act of Conservation (Washington: The American Enterprise Institute for Public Policy Research, 1975).

Robert R. Palmer, The Age of the Democratic Revolution: The Challenge (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1959).

Robert R. Palmer, The Age of the Democratic Revolution: The Struggle (Princeton University Press, 1964).

[Pocock] Three British Revolutions: 1641, 1688, 1776. Edited by J.G.A. Pocock (Princeton University Press, 1980).

Murrary N. Rothbard, “Left and Right: The Prospects for Liberty” Left and Right: A Journal of Libertarian Thought (Spring 1965, no. 1), pp. 4-22;

Murray N. Rothbard, For a New Liberty: The Libertarian Manifesto. Revised edition. (New York: Collier Macmillan, 1978), “Preface. The Libertarian Heritage: The American Revolution and Classical Liberalism,” pp. 1-19. Online at Mises Wire.

The Five important Periods in the Development of Classical Liberalism / Libertarianism

[With links to the relevant articles in the EoL and my website.]

The Pre-History of Liberalism: Precursors and Influences

Its “pre-history” during the classical, medieval, and reformation/renaissance periods when some of the key ideas evolved but they were not brought together into a coherent “worldview”:

- Greek ideas about democracy; the independent self-governing polis; the existence of a higher moral law, and justice

- Roman ideas about natural law; property law; the problem of the tyrant king/emperor; tyrannicide: Stoicism and Epicurianism; Cicero – Stoicism; Epicureanism; Cicero (106-43 BC); Natural Law

- Christian ideas about the individual soul; the higher moral law; the early church as a voluntary, self-governing association; the abbey/monastery as an early form of the “firm”; decentralised decision-making and governance; overlapping jurisdictions / legal polycentism

- the Medieval Period: Magna Carta – Magna Carta; the Free Cities and their Charters; Scholastics – School of Salamanca – Scholastics/School of Salamanca

- the Renaissance Republicanism; the independent republican city and its citizens; self-governance and political independence from the central power (monarchy, or pope); rule by a pro-trade, commercial oligarchy; opposition to tyrants/tyranny: Classical Republicanism – Republicanism, Classical; The Dutch Republic – Dutch Republic

- the French Humanist magistrate Étienne de La Boétie (1530-1563) EoL who asked why a minority of ruthless “princes” and their allies could plunder and abuse the majority of taxpaying and obedient people without using (too much) violence. His answer was that most people willingly entered a state of “voluntary servitude”. See my Boétie page and my edition of his “Speech on Voluntary Servitude” (c. 1550s) here.

(1) 1640s: the English Civil War and Revolution (proto-liberalism)

The 17th century, particularly in England, we see the emergence of the Levellers and other supporters of Parliament against the growing power of the monarchy, during the Civil Wars and Revolution and then the Exclusion Crisis leading up to the Revolution of 1688.

- English Common Law: Edward Coke – Common Law;

- The English Civil Wars/Revolution of the 1640s: the Levellers, John Lilburne, Richard Overton, William Walwyn, John Milton. One of my favourites from among the emerging “proto-liberals” of the 1640s was the Leveller Richard Overton (1631–1664) who wrote one of the greatest and impassioned defenses of “self-propriety” (self-ownership) ever written, An Arrow against all Tyrants and Tyranny (Oct. 1646) text. See the EoL entry on the Levellers here and my “Leveller Tracts and Pamphlets Project” here. See also English Civil Wars; Milton, John (1608-1674)

- the Glorious Revolution of 1688: Algernon Sidney, John Locke, Whigs – Glorious Revolution; Sidney, Algernon (1623-1683); Locke, John (1632-1704)

- the “big name” of 17th century liberals is of course the English philosopher John Locke (1632-1704) EoL whose Two Treatises of Government (written 1680–1683, published in 1689) was the definitive statement on the right to property and the need for all governments to have the consent of the governed. See Book II, chap. V “Of Property” here.

(2) 1750s-1790s: the American and French Revolutions (early liberalism, the “liberal “ Enlightenment)

The 18th century Enlightenment in France, Scotland, England, and North America which culminated in the American and French Revolutions and the creation of the first limited, constitutional, “liberal” government in the world.

- in general on the 18thC Enlightenment in Europe and North America – Enlightenment.

- the French Enlightenment: the possibilities to include here are enormous, but one of my favourites is Voltaire (1694-1778) EoL who waged a one-man war against all forms of intolerance, especially by the Church. His witty overview of the injustices of his own day can be found in his “philosophic tale” Candide (1759) here; and his critique of the Church and church doctrine in his Philosophic Dictionary (1764). Among the many entries, see “Inquisition” and “Intolerance”; and “Toleration” and “Torture” See also my main Voltaire page. See also the entries on Physiocracy; Montesquieu, Charles de Secondat de; Diderot, Denis (1713-1784)

- the Scottish Enlightenment: it is hard to go past Adam Smith (1723-1790) EoL as the best representative of the Scottish Enlightenment. His critique of government interventionism in the economy (known as “Mercantilism” in his day EoL is unsurpassed (except for perhaps Frédéric Bastiat 75 years later). The section in his Wealth of Nations (1776) on “the invisible hand” is classic – found in Book IV, Chapter II “Of restraints upon the importation from foreign countries of such goods as can be produced at home” here. See also Adam Ferguson, David Hume – Ferguson, Adam (1723-1816); Hume, David (1711-1776).

- key figures in the English Enlightenment were the 18thC Commonwealthmen, Cato’s Letters, Trenchard and Gordon – Cato’s Letters

- the American Enlightenment: the American Declaration of Independence (1776) is perhaps the greatest statement of CL political principles ever written. The draft was penned by Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826). See the EoL entry “Declaration of Independence” and on Jefferson. Although not an American by birth the English born Thomas Paine (1737-1809) EoL was active in England, America, and then France. His two-part Rights of Man (1791, 1792) was and remains a stirring defence of individual liberty against the claims of the state (especially monarchies) and those who opposed natural rights rights (like Edmund Burke). See especially Part II. Chapter I. Of Society and Civilisation here; Chapter II. Of the Origin of the Present Old Governments; and Chapter III. Of the Old and New Systems of Government.

- The American Revolution: Thomas Paine, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison – American Revolution; Paine, Thomas (1737-1809); Jefferson, Thomas (1743-1826); Madison, James (1750-1836)

- The French Revolution: Lafayette, Condorcet, the Girondins, Destutt de Tracy, Madame de Stael – French Revolution; Condorcet, Marquis de (1748-1794); Tracy, Destutt de (1754-1836);

(3) The long 19th century 1815-1914 (classical liberalism)

During the 19th century “classical liberalism” emerged and the most comprehensive liberal reforms (political, economic, and social) were introduced:

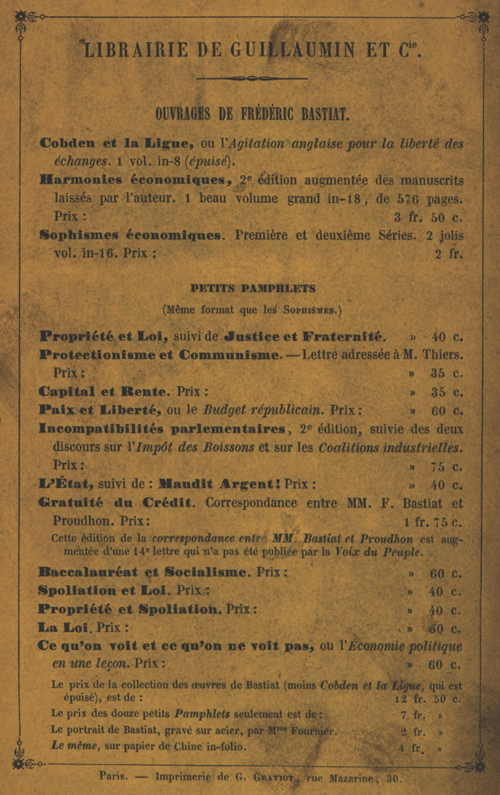

- Classical Liberalism (the French School): Jean-Baptiste Say, Benjamin Constant, Charles Comte, Charles Dunoyer, Frédéric Bastiat, Gustave de Molinari – Say, Jean-Baptiste (1767-1832); Constant, Benjamin (1767-1830); Comte, Charles (1782-1887); Dunoyer, Charles (1786-1862); Bastiat, Frédéric (1801-1850); Molinari, Gustave de (1819-1912). My favorite is the French politician and economist Frédéric Bastiat (1801-1850) was the greatest economic journalist who has ever lived and during his relatively short life he produced some of the wittiest and most profound critiques of tariff protection and socialism ever written by a CL. See his “Petition of the Candlemakers” (1845) ES1.7 at OLL as an example of the former, and The Law (1850) at OLL as an example of the latter. See the EoL entry on Bastiat and my main Bastiat page.

- Classical Liberalism (the English School): Philosophic Radicals, Utilitarianism, Jeremy Bentham, James Mill, Classical Economics, John Stuart Mill – Liberalism, Classical; Philosophic Radicals; Utilitarianism; Bentham, Jeremy (1748-1832); Classical Economics; Mill, John Stuart (1806-1873). See in particular the English politician theorists John Stuart Mill (1806-1873) EoL and Herbert Spencer (1820-1903) EoL who represent the split which existed within CL between the advocates of utilitarianism and those of natural rights. Both wanted to limit the powers of the state but JSM was much more moderate, while Spencer verged on the anarchistic. See my Mill page (to come) and Spencer page. See Mill’s Chap. IV. “Of the limits to the authority of society over the individual” in On Liberty (1859) here; and Spencer’s Chap. XIX “The Right to Ignore the State” in Social Statics (1851) here.

- Australian CL: for an Australian flavor we have a professor of economics at the University of Melbourne, William Hearn (1826-1888), who was influenced by Bastiat and the NSW politician Bruce Smith (1851-1937) who had been influenced by Spencer. Neither, unfortunately, are mentioned in the EoL but see my Hearn page and Smith page. See Hearn’s chapter on the proper functions of the state, Chapter XXIII. “Of the Impediments Presented to Industry by Government” in Plutology (1863) here; and Bruce Smith’s chapter IX “Practical Application of the Principles of True Liberalism” in Liberty and Liberalism (1887) here.

Key issues and movements of CL reform in the 19thC:

- the Abolition of Slave Trade and Slavery: Clarkson, William Wilberforce, William Lloyd Garrison, Frederick Douglass, John Brown, Lysander Spooner – Abolitionism; Slavery in America; Wilberforce, William (1759-1833); Garrison, William Lloyd (1805-1879); Douglass, Frederick (1818-1895); Brown, John (1800-1859); Spooner, Lysander (1808-1881)

- Constitutional Monarchism: Benjamin Constant – Constitutionalism; Constant, Benjamin (1767-1830)

- Free Trade Movement: Anti-Corn Law League, Richard Cobden, John Bright; Bastiat, Michel Chevalier – Anti-Corn Law League; Free Trade; Cobden, Richard (1804-1865); Bright, John (1811-1859); Bastiat, Frédéric (1801-1850)

- 1848 Revolutions: constitutionalism and abolition of serfdom

- opposition to war and empire: Cobden, Bright, W.G. Sumner – War; Peace and Pacifism; Cobden, Richard (1804-1865); Bright, John (1811-1859); Sumner, William Graham (1840-1910)

- Feminism and Women’s Rights: Mary Wollstonecraft, J.S. Mill – Feminism and Women’s Rights; Wollstonecraft, Mary (1759-1797); Mill, John Stuart (1806-1873)

- The Radical Individualists: Thomas Hodgskin, Herbert Spencer, Auberon Herbert – Individualism, Political and Ethical; Individualist Anarchism; Spencer, Herbert (1820-1903); Herbert, Auberon (1838-1906)

- The Austrian School of Economics (1st generation): Carl Menger, Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk – Economics, Austrian School of; Menger, Carl (1840-1921); Böhm-Bawerk, Eugen von (1851-1914)

(4) The post-WW2 Liberal Renaissance and the Rise of “Libertarianism”

There was decline and “long sleep” of CL during the 1st three quarters of the 20th century before its re-emergence in the 1970s and 1980s with the modern “libertarian” movement in the U.S. and elsewhere. Some groups of note include:

The Austrian School (inter-war years): Ludwig von Mises, Friedrich Hayek – Economics, Austrian School of; Mises, Ludwig von (1881-1972); Hayek, Friedrich A. (1889-1992).

The Post-World War 2 Liberal Renaissance:

The Austrian School of Economics (2nd generation):

- Mises, Hayek, Murray N. Rothbard, Israel Kirzner – Economics, Austrian School of; Mises, Ludwig von (1881-1972); Hayek, Friedrich A. (1889-1992); Rothbard, Murray (1926-1995); Kirzner, Israel M. (1930-). Key texts include Ludwig von Mises, Human Action (1949); Friedrich Hayek, The Constitution of Liberty (1960); and Murray Rothbard, Man, Economy and State (1962)

Other Economic Schools:

The modern American Libertarian movement:

The Australia Workers Party (1975): John Singleton and Bob Howard wrote and promoted The Australian “Workers Party Platform” (1975) – the most consistent application of the “non-aggression principle” by any political party ever. Here in HTML and facs. PDF. This is emblazoned at the bottom of every page: “No man or group of men has the right to initiate the use of force, fraud or coercion against another man or group of men”. See the EoL entry on the “Nonaggression Principle”.