Bastiat is justly famous for the idea of “the seen” (ce qu’on voit) and “the unseen” (ce qu’on ne voit pas) which was the title of the last book he wrote before his untimely death on Christmas Eve 1850. It was an original contribution to the idea of opportunity cost (which Tony de Jasay believed he in fact invented) which was brilliantly described in his witty and deeply insightful booklet. Less well known is the fact that he had been developing the idea over the course of the previous ten years and that it had a richness and depth which has not been fully appreciated – “not seen” you might say. I believe it was also a crucial part of his treatise on economic theory, Economic Harmonies on which he was working when he wrote his booklet What is Seen and What is Not Seen.

In this paper “Bastiat on the Seen and the Unseen: An Intellectual History” I explore the history of the development of his idea and some of its related concepts. One of these is the idea that economic acts (often interventions by the state) create a series of interlocking and sequential “effects” or “consequences” which flow outwards into other sectors of the economy. These effects are separated in time and space from the initial act and are often hard to observe. Some are close by in time and space and can be easily “seen” by even the untrained eye. Others however are stretched out across space and time and can be quite subtle in their impact. Thus they are hard to discern and are largely “unseen” except for the “good economists” who have been trained in the complexities of market processes.

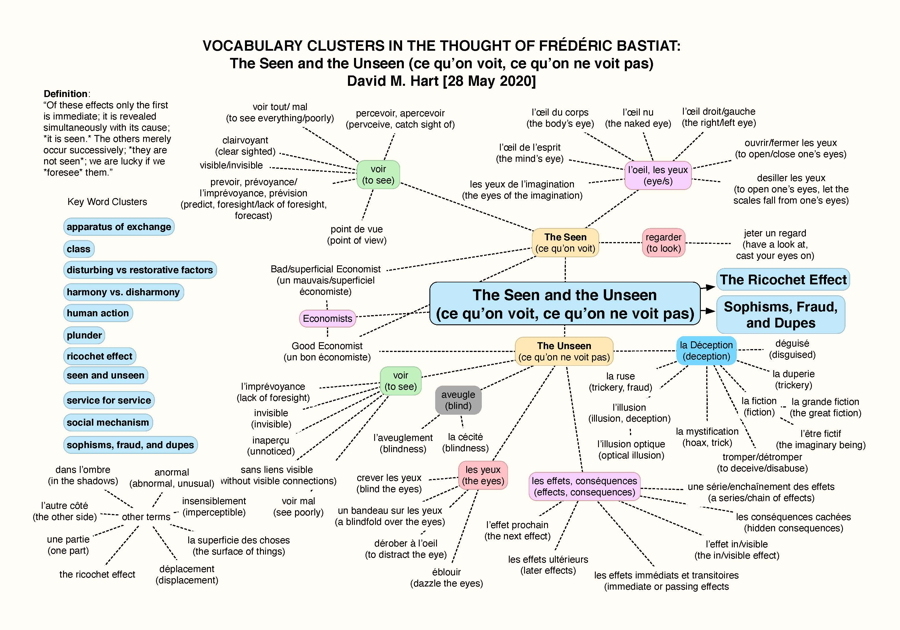

As he often did with his original ideas, Bastiat developed a complex “cluster” of terms and concepts to describe and explain his ideas about how the economy functioned. He did this with his theory of “la spoliation” (plunder), “la classe” (class), “les causes perturbatrices et les causes réparatrices” (disturbing and restorative factors), “l’harmonie et la dissonance” (harmony and disharmony), and “l’action humaine” (human action), and for each of these “clusters” I have created a visual concept map to help the student of Bastiat’s work understand it better. They can be found here. I have now done the same for his idea of “the seen” and “the unseen.”

See a larger version

Bastiat was a very skilled wordsmith and loved to make puns and other plays on words, and create many allusions to related terms and concepts. This was part of his “rhetoric of liberty” and reflected his great love of literature and his masterful command of language. As he liked to do, Bastiat uses pairs of opposing words and concepts to make his arguments, such as the seen and the unseen, the visible and the invisible, the noticed and the unnoticed, things in the light and things in the shadows, the real world versus the unreal world of fictions and illusions and disguises, the close by and the distant, the immediate and the postponed or delayed, the hidden and the obvious, the direct and the indirect, being blind and being clear sighted, seeing only one side or all sides of an event, the deep and the superficial, the normal and the abnormal, the single event versus events which are linked in a chain or series, and of course the good economist who sees or foresees “the unseen” and the bad economist who does not.

This paper is part of a broader project I have underway to reclaim Bastiat as a significant economic theorist, after his abject dismissal by scholars such as Joseph Schumpeter (“I do not hold that he was a bad theorist. I hold that he was no theorist.”) a view which has been repeated endlessly by people who I think have not actually read the man’s work in either English or French.

As he observed in chapter 12 on “the right to work and the right to a profit” in WSWNS:

“Not to understand political economy is to let oneself be blinded by the immediate effect of a phenomenon; to understand it means to consider all of its effects in one’s thinking and in one’s predictions about the future.”