Louis Blanc, Organisation of Work (Sept., 1840)

|

|

| Louis Blanc (1811-1882) |

Source

Organization of Work by Louis Blanc. Translated from the First Edition by Marie Paula Dickoré. University of Cincinnati Studies, Series II January-February, 1911, Vol. VII, No. 1. (Published by The University Of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, Ohio, 1911).

This is a translation of the 1st edition of September, 1840 which was published in the magazine "Organisation du travail," Revue du Progrès, Tome deuxième, 2e série, , p p. 1-30. It would be republished many times (the 9th edition appeared in 1850) with c hanges and additions in almost every edition as Blanc responded to his critics, such as the conservative politician Adolphe Thiers and the political economist Michel Chevalier.

See other versions of this work:

- a French version of the 1840 magazine article (which differs somewhat from Dickoré's version, in HTML

- a French version also from 1840 as a stand alone pamphlet: Organisation du travail (Paris: Prévot, 1840).[facs. PDF]

- another early French version from 1841: Organisation du travail. Association universelle. Ouvriers. - Chefs-d'Ateliers - Hommes de lettres. (Paris: Administration de Librairie, 1841). [facs. PDF]

- it was republished in 1845 and 1847 and yet again in 1848 during the revolution when Blanc attemtped to put his ideas into practice as a leasder of the Luembourg Commission: Organisation du travail. Cinquième édition . Revue, corrigée et augmentée d'une Polémique entre M. Michel Chevalier et l'auteur, ainsi que d'un Appendice indiquant ce qui pourrait être tenté à présent. (Paris: Au Bureau de la Société de l'Industrie Fraternelle, 1848). [facs. PDF]

- such was the interest in the book it was quickly translated into English and also published in 1848: The Organization of Labour. (London: H.G. Clarke and Co., 1848). [facs. PDF]

- the pamphlet also stimulated political economists like Michel Chevalier and Frédéric Bastiat to respond. Chevalier's critique was translated and published in 1848, along width some of Blanc's speeches: Michel Chevalier, The Labour Question. 1. Amelioration of the Condition of the Labouring Classes. 2. Wages. 3. Organization of Labour. Translated from the French.* (London: H.G. Clarke & Co., 1848). Chevalier’s essay was originally published in the Révue des Deux Mondes, 15 March, 1848, and here, pp. 7-69; with additional material by Louis Blanc: Addresses of M. Louis Blanc to the Committee of Workmen at the Luxembourg. To which is added “The Report of the Committee” (London: H.G. Clarke, 1848), pp. 73-119, and pp. 121-50. [facs. PDF]

Table of Contents

- TRANSLATOR’S PREFACE

- AUTHOR’S PREFACE

- CHAPTER I. THE ORGANIZATION OF LABOR.

- CHAPTER II. COMPETITION IS FOR THE PEOPLE A SYSTEM OF EXTERMINATION

- CHAPTER III. COMPETITION IS THE CAUSE OF THE DECLINE OF THE BOURGEOISIE

- CHAPTER IV. COMPETITION CONDEMNED BY THE EXAMPLE OF ENGLAND

- CHAPTER V. COMPETITION WILL NECESSARILY RESULT IN A DEATH STRUGGLE BETWEEN ENGLAND AND FRANCE

- CHAPTER VI. THE NECESSITY OF A DOUBLE REFORM

- CONCLUSION. HOW, ACCORDING TO OUR VIEW, IT WOULD BE POSSIBLE TO ORGANIZE

Text

TRANSLATOR’S PREFACE↩

The author of this interesting little book, Jean Joseph Charles Louis Blanc, was born far from the scene of his life work in Madrid, October 29, 1811. [FN1: Various dates are given but I have accepted October 29, 1811, on the authority of “Le Grande.” Warshauer has October 28, while among others Daniel Sterne (Madame d’Agoult) Histoire de la Révolution and Quack, De Socialisten, make a mistake of two years, giving 1813 as the year of Blanc’s birth. Golliet gives still another, 1812. ] His father, Jean Charles, had suffered by the Reign of Terror and fled to Spain where he served as General Inspector of Finance under Joseph Bonaparte. He had married Estella Pozzo di Borgo and their two children were Jean and Charles. Soon after the family returned to France during the Restoration, their circumstances became so straightened that Louis was thrown upon the world to earn his own way.

The pittance received from private lessons and clerking in an attorney’s office was not sufficient so Blanc accepted, in 1832, a position as tutor in Arras in the family of a manufacturer, Halette, who employed more than 300 workmen.[FN2: Warshauer, Otto—Zur Entwicklungsgeschichte des Socialismus, part III, pp. 237, Louis Blanc, Berlin 1903.] Here Blanc not only attended to his profession but made observations which sowed the seed for his future career. He talked with the work men and studied their life and conditions; he endeavored to teach them and saw with pleasure how eager they were to educate them selves. Thus he had the opportunity of studying at close range conditions which heretofore had been strange to him and which now formulated in his mind the sketch for the interpretation of life which he later enlarged upon and made such great use of in his famous work.[FN3: Golliet, (Louis Blanc, sa doctrine—son action, Paris, 1903), claims that the difficulties which Blanc experienced before he went to Arras turned his thoughts to reflections on and criticisms of the social organization; , also that Flaugergues, a friend and compatriot of the Blanc family told Louis about his experiences in the world of politics and thus laid the foundation of the ideas later developed by Blanc.]

[5]

Arras wās not only the birthplace of his socialistic, but also of his journalistic career, for two of his poems, Sur Mirabeau and Eloge de Manuel, were awarded prizes by the Arras academy and local newspapers published other bits from his pen. In 1834 he returned to Paris, wrote for various papers and finally in 1837 became the editor of the Bon Sens. The impressions received in Arras first came to light in this Bon Sens. He pointed out the evil effect of free competition on the working classes and went even so far as to devote a portion of his paper to all working men’s news. However, this happy labor was not to exist long. Blanc disagreed with the publishers because they were not in harmony with his ideas and the final break came when he demanded that the building of railroads be conducted by the state and not by private corporations.

This break, however, did not crush his dauntless spirit. In 1839 he founded the Revue du Progrès, politique et litteraire, a magazine appearing every month and in which he could give his ideas free scope. He pointed out the corruption of the bourgeoisie in France; violently attacked the rights of the nobility; warmly recommended the introduction of equal suffrage and made a plea for the proletarian and his material welfare.[FN4: Warshauer; pp. 239.] The best product of this journalistic freedom was the series of articles, appearing in 1839 which, receiving so much applause throughout France, were published in pamphlet form, September, 1840.[FN5: Many writers have said that the pamphlet was published in 1841 but my copy of the first edition is dated September, 1840.] Of this valuable article nine editions have appeared altogether, the last dated April 15, 1850.

Although Blanc proved himself a writer of no mean ability in his later productions (Histoire de dir ans, Histoire de la Révolution française), this Organization du Travail is a little masterpiece showing the author to be a clear thinker, a fine idealist, possessed of a versatile, brilliant style with which to clothe his arguments and illustrate them by animated depictions of poverty and destitution. He set forth[FN6: Warschauer—The fundamental principle of the Organization du Travail is: all free competition must be destroyed because it does not combine harmoniously but disseminates the activities of each individual; being for the masses an unbearable condition of suffering and being also the cause of the antagonism which necessarily must exist between all producers and all consumers. Blanc was certain that through free competition individual interest grows into a rapacious craving and that in the pursuit of wealth he who amasses riches strides victoriously over the ruins of others and builds up his own fortune out of the shattered fragments.] the evils inherent in the [6] social conditions and the sufferings of the laboring class, due to insufficient wages, in order to demonstrate that a strict regulation of labor is necessary; for he held that individualism and free competition will ruin both the laboring class and the bourgeoisie. To this end he advocated the idea that the government should own the greater industries and establish national workshops in which each man would receive according to his needs and contribute according to his abilities. The state would then, through self production cripple all other competitors and finally become the only maintenance of society. Blanc was a defender of the right of existence and an opponent of any income without work— especially of interest on capital.

The little book created such a stir among the laboring classes that the organization of work became the problem to be solved by the February Revolution, 1848, and as Blanc was a member of the Provisional Government, also president of the commission for the discussion of the labor problem,[FN7: Much for the betterment of the working classes was really accomplished by this commission; a ten hour day in Paris and an eleven hour day in the provinces; abolished the “marchandage;” settled strikes, abolished the competition of prison labor, etc.] it was decided to give his plan a trial and National Workshops were established February 27, 1848. However, so many applied for work in these ateliers that each one could work only about every fourth day though receiving pay. Thousands of unemployed stormed Paris in search of this Eldorado so that a halt had to be called on the great wave of immigration of undesirable population by means of unfair decrees, with the result that Blanc did not see his plans accomplished owing to mismanagement by those in charge and harsh measures in reducing the number of applicants. As these ateliers were purposely not planned and equipped at the start according to Blanc’s theories, they were a failure, brought about the June insurrection, and caused Blanc’s flight to England. His scheme was not practicable in his day, for he was, like many another genius, far ahead of his time; he understood the ills of society and saw a fit remedy of which, however, years of patient application would be necessary in order to overcome the deep rooted evils.

Thus we see that Louis Blanc was the founder of this national workshop theory, but not the active leader in the [7] revolution of 1848, only the suggestive power. Though his practical work failed, his ideas have lived on and have been adopted by various bodies of socialists, especially the German school, which reached its height in Karl Marx.

The years 1848-1870 Blanc spent in England where he wrote his twelve volume History of the French Revolution. After the fall of the Empire, he returned to Paris in 1870 and in 1871 was elected to the National Assembly. He died at Cannes, December 6, 1882.

The ninth edition, 1850, is divided into four parts: Part I, called Industry, contains the original material with many additions; Part II, Agriculture; Part III, Literary work, which appeared as early as the fourth edition, 1845; Part IV, Credit, also answers to many charges made against statements in the first edition. Each part shows that its special branch of labor, too, must be controlled by the State in order that Free Competition may not bring about its ruin.

This study will set forth a translation of the first edition only.

I wish to express my great appreciation of the kind assistance rendered by Adolph Ebel, Universität Marburg, to whom I am indebted for a copy of the rare first edition without which I could not have made this translation; to Miss Mary C. Gallagher for a careful and critical reading of the manuscript; to N. D. C. Hodges, Cincinnati Public Library, Wm. H. Bishop, Library of Congress, and Walter Smith, University of Wisconsin Library, for the loan of valuable books. To Professor Merrick Whitcomb, however, I owe the inspiration for this task and by inscribing this book to him I wish to express my sincere gratitude.

Marie Paula Dickoré

Cincinnati, 1910

[8]

AUTHOR’S PREFACE↩

This work has been especially written for the Revue du Progrès in which it has been published serially.

Some laborers have thought that under the actual circumstances it would be good to give more publicity to it than was possible through the circulation of the Revue du Progrès.

The agitation shown in the last few days is the symptom of a profound evil.

That the police might be concerned in the movement in order to ruin it, is possible. But to make it depend solely upon some foul tricks would be to slander without reason the people of Paris.

The workmen of Paris do not rise to instigate civil war but to demand justice. To confront them with millions of bayonets is a childish and useless expedient.

Once again, the evil is deep rooted; it demands a prompt remedy. To find that remedy should be the mission of the powerful; to seek it, the duty of every good citizen.

September, 1840.

CHAPTER I. THE ORGANIZATION OF LABOR.↩

The institution of modern society rests principally on two men, the one acts as a figure head, the other as headsman. The hierarchy of the old school of politics begins with the king and ends on the gallows.

When the workingmen of Lyons rose, saying, give us bread or kill us, we were very much embarrassed by this demand. As it seemed too difficult to support them, we strangled them.

By this means order was reestablished.

However, the question is to make up your mind whether you are willing to try such bloody experiments. How you would be hated, should you decide on such a dangerous measure. Every delay conceals a storm.

Is not all Paris in a state of excitement as I am writing these lines? Why these numerous meetings of laborers in the different parts of the capital? Why these detachments of cavalry, which patrol our boulevards in a menacing manner? But, God be praised, this time the press is a little less excited. It has been speaking of these agitations in the same serious manner as if the journey of a princelet or a horse race were in question. Let us take courage We are entering upon the way of progress. But know well, gentlemen, where the first step leads. You speak of solving problems? From today on a solution will be an imperious necessity. Moreover, what are we waiting for? Has the epic of modern industry further mournful episodes to relate? The recent unfortunate events in Nantes, the riot in Niemes, the massacre in Lyons, the many bankruptcies in Milan, the embarrassments of all money-markets, the troubles in New York, the rise of chartism in England, are not these solemn and formidable warnings abroad? Is it not because so many fortunes are crumbling, because so much gall is mixed with the joy of the rich, so much wrath swelling the heart of the poor man under his rags?

I ask, who really is interested in the maintenance of the economic conditions of today? No one at all; neither the rich nor the poor, neither the master nor the slave, neither the tyrant nor [11] the victim. As for me, I am perfectly convinced that the suffering which is produced through an imperfect civilization is distributed in various forms over the whole of society. Let us look at the life of the rich man; it is filled with bitterness. And why? Is he not in good health? Is he no longer young? Are women and flatterers wanting to him? Does he doubt that he has friends? No, his misery is, that he has reached the end of his enjoyments, his unhappiness is, that he has no further desires. The inability to enjoy, as the result of satiety, that is the poverty of the rich —a poverty without hope. How many of those whom we call happy plunge into a duel because of a longing for excitement, how many seek the dangers and toil of the hunt to escape the tortures of idleness? How many, hurt through their sensitiveness, suffer from secret wounds in the midst of an apparent happiness and sink gradually below the surface of the general suffering, side by side with those who throw life away like a bitter fruit; those who cast it aside like a squeezed lemon! What social disorder is not revealed by this great moral disorder! What a severe lesson to egotism, to pride, to every kind of tyranny that this inequality in the means of enjoyment ends in the equality of anguish.

To every poor person who is pale from hunger there is a rich one who grows pale from fear. “I do not know,” said Miss Wardour to the old beggar who had saved her, “what my father will do for our rescuer, but he will certainly secure you against every want for the rest of your life. Accept for the present this trifle.” “That I may be robbed of it or murdered, when I wander at nights from place to place,” answered the beggar, “or at least be in constant fear of it, which is hardly better. Ah! and besides, who would be fool enough to give me alms if he saw me change a banknote?”

Admirable reply! Walter Scott is in this not only a novelist but he proves himself to be a philosopher as well as a socialist. Who is the unhappier of the two, the blind man who hears the begged coin ring in the cup which his dog guards, or the mighty king who groans when a dower is refused his son?

If a thing is true philosophically is it any less true economically? Thank God! for society there is neither a partial progress nor a partial decline. The whole society rises, or falls. When justice is exercised, all have the advantage, when right is obscured, the whole suffers. A people in which one class is suppressed [12] resembles a man who has a wounded leg. The injured leg prevents him from using the good one. This sounds paradoxical, the oppressor and the oppressed gain equally by the removal of oppression; they lose equally by its maintenance. Do we want a more striking proof of this? The bourgeoisie has built its sovereignty upon free competition—the basis of tyranny; alas! we see today the decline of the bourgeoisie through this free competition. I have two millions, you say, my competitor has only one; in the arena of industry, armed with the advantages of the lowest price, I shall certainly ruin him. Coward and fool! Do you not see that some merciless Rothschild, armed with your own weapons, will ruin you tomorrow ! Then, how could you have the effrontery to complain? The large tradesman, in this wretched system of daily struggles, has already swallowed up his smaller competitor. What a Pyrrhic victory ! For behold this larger tradesman is swallowed up in his turn by the great operator who, himself forced to seek new customers at the ends of the world, will begin to play a game of chance, which, like all games, will bring some of its players to crime, others to suicide. Tyranny is not only hateful, but it is also stupid. No intelligence can exist where there is no consideration for others.

Then let us prove:

- That competition is for the people a system of ex termination.

- That competition is an ever present cause of impoverishment and decline of the bourgeoisie.

When we have proven this it will be clear that we shall establish a solidarity of interests and that social reform means salvation for all members of society without exception.

[13]

CHAPTER II. COMPETITION IS FOR THE PEOPLE A SYSTEM OF EXTERMINATION↩

Is the poor man a member of society or its enemy? Answer this He finds the soil everywhere about him already occupied.

May he cultivate the land for himself? No, for the right of the first occupant has become the right of possession.

May he gather the fruits which God has allowed to ripen along the common highway? No, for as the soil so the fruits have been appropriated.

May he hunt or fish? No, for that is a right which the state claims.

May he draw water from a well in a field? No, for the proprietor of the field is, by the law of accretion,[FN8: “Accessio—A term of Roman law used to express the acquisition of property by an addition to former property, due to an accidental circumstance. If, for instance, a plot of land on the bank of a river was increased by the gradual deposit of earth on the bank, the property in the new piece of land was said to be acquired by Accessio.” From Palgrave, R. H. Inglis, ed., Dictionary of political economy.] also the proprietor of the well.

May he, dying from hunger and thirst, reach out his hand, beseeching the benevolence of his fellow-men? No, for there are laws against begging.

May he, tired and without shelter, stretch his limbs out on the pavement? No, for there are laws against vagabonds.

May he flee from his homicidal fatherland, which denies him everything and endeavor to gain a livelihood far from his birth place? No, for he is permitted to change his place of abode only under certain conditions, impossible for him to fulfill.

What then shall the unfortunate one do? He will tell you: “I have arms, I have intelligence, I have strength, I have youth, take them all and give me in exchange a morsel of bread.” Thus the proletarians speak and act today. But even then your answer to the poor one is: “I have no work to give you.” What do you want him to do then? It is very clear that there are but two horns to this dilemma, he can either kill himself or kill you.

[14]

The answer is very simple: ASSURE the poor man work. Even with this there is certainly little enough done for justice, and you are still a very long way from the reign of fraternity, but at least you will have removed the necessity for revolt, and his hate is deprived of its justification. Have you already thought of it? When, in order to live, a man offers society his services and then is forced necessarily to attack this same society in order not to die of hunger, he finds himself, although apparently an aggressor, in a state of legitimate defense, and the society which strikes him does not judge him but assassinates him.

The question should be put thus: Is competition a means of ASSURING work to the poor? To put a question of this kind, means to solve it. What does competition mean to workingmen? It is the distribution of work to the highest bidder. A contractor needs a laborer: three apply. “How much do you ask for your work?” “Three francs, I have a wife and children.” “Good, and you?” “Two and a half francs, I have no children, but a wife.” “So much the better, and you?” “Two francs will do for me; I am single.” “You shall have the work.” With this the affair is settled, the bargain is closed. What will become now of the other two proletarians? They will starve, it is to be hoped. But what if they become thieves? Never mind, why have we our police? Or murderers? Well, for them we have the gallows. And the fortunate one of the three; even his victory is only temporary. Let a fourth laborer appear, strong enough to fast one out of every two days; the desire to cut down the wages will be exerted to its fullest extent. A new pariah, perhaps a new recruit for the galleys.

Can anyone assert that these conclusions are exaggerated, that they are not possible in all cases in which the amount of work is not sufficient for the poor who want to be employed? I shall ask for my part if competition contains in itself the means of doing away with this murderous inequality. If one industry lacks labor, who will vouch for it that in this immense confusion, caused by a universal competition, some other industry does not suffer a surplus of labor? It would be sufficient to invalidate the principle if only twenty men out of thirty-four millions were driven to be thieves in order to live. Destroy these unhappy ones, I say, and let civilization herself take vengeance upon them for the crime which she has committed against them, but do not mention righteousness any more; and since you refuse to judge your judges, to [15] overthrow your courts, raise a temple to violence and drape a veil about the statue of justice.

Who would be blind enough not to see that under the reign of free competition the continuous decline of wages necessarily becomes a general law with no exception whatsoever? Has population limits which it may never overstep? Are we allowed to say to industry, which is subjected to the daily whims of individual egotism, to industry, which is an ocean full of wreckage: “Thus far shalt thou go and no farther.” The population increases steadily; command the mothers of the poor to be sterile and blaspheme God who made them fruitful; for if you do not command it, the space will be too small for all strugglers. A machine is invented; demand it to be broken and fling an anathema against science! Because if you do not do it, one thousand workmen, whom the new machine displaces in the workshops, will knock at the door of the next one and will force down the wages

of their fellow-workers. A systematic lowering of wages resulting in the elimination of a certain number of laborers is the inevitable effect of free competition.

It is nothing but an industrial process by means of which the proletarians are forced to exterminate each other. Finally, in order that the exacting people can not accuse us of having exaggerated the colors of the picture, we give here in figures the condition of the working class of Paris:

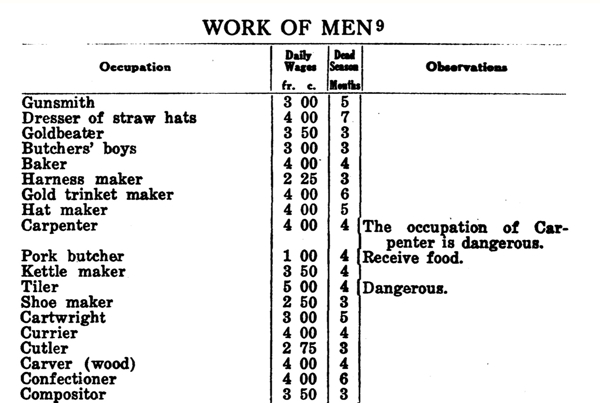

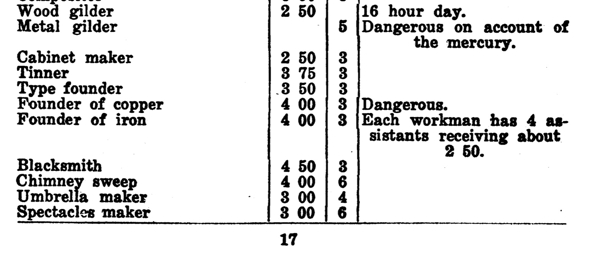

WORK OF WOMEN

WORK OF MEN

[FN9: Author’s note—We are indebted for these statistics, which we have collected with great care in order that no one will be tempted to accuse us of exaggeration, to Messrs. Robert, dyer, 60 Gravilliers Street; Rosier, cane-maker, 33 Sainte Avoie St.; Landry, cabinet maker, 99 Faubourg St. Martin; Baratre, saddler, 17 Laborde St. : Moreau, clerk, 16 Caire St. ]

[16]

[17]

How many tears are represented in every one of these figures, how many cries of anguish! How many violent curses from the depth of the heart! This is the condition of the populace of Paris, the city of science, of arts, the most brilliant capital of the civilized world; a city, whose face shows only too truthfully all the ugly contrasts of a highly praised civilization: beautiful boulevards and dirty streets; brilliantly lighted stores and dark work shops; theaters, in which there is singing, and dark hovels where [18] is only weeping; monuments for the conqueror and a corner for the drowned, the Arc de l’Etoile and the morgue!

The attraction which these large cities have for the country people is certainly a remarkable fact; these cities where every moment the riches of some mock the poverty of others. Nevertheless, this fact exists and is only too true: industry is the opponent of agriculture. A periodical devoted to the discussion of the present social conditions recently published these sad lines from the pen of a prelate, the bishop of Strassburg: “The mayor of a little town told me: “Formerly I paid my laborers three hundred francs, today one thousand francs are scarcely sufficient for the same work. They threaten to abandon our work and go to the factories if we do not agree to pay high wages.” How much will agriculture, the true wealth of a country, suffer under such conditions! Add to this the fact that when commercial credit is unsound, when one of these business houses fails, three or four thousand laborers are suddenly thrown out of employment, are without bread, and fall a burden to the state. For these unfortunates do not know how to save for the future; every week sees the fruit of their toil vanish. How dangerous, in times of revolution, exactly when bankruptcies become more numerous, is the population of starved workingmen, who are suddenly thrown from recklessness into absolute want. They even lack the resource of selling their labor to the farmers; they are not accustomed any longer to the hard work of the fields, their enfeebled arms have no longer the strength for it.”

Not enough, that the great cities are centers of extreme misery, but it is further a fact that the population of the country is irresistibly drawn towards these centers which engulf them. And, as if to aid this wretched condition, is it not true that we are building railroads everywhere? For these railroads, which in a prudently governed society, represent an immense progress, are in our own, only a new misfortune. They render desolate the places where labor is lacking and heap up men in those places where many are seeking in vain to get their little place in the sun; they tend to complicate the frightful disorder which they have introduced into the laboring class, into the distribution of work and of products.

We now come to the cities of second rank.

Dr. Guépin has written, in a little booklet, unworthy, I suppose, of being placed in the library of a statesman, the following words:

[19]

“As Nantes takes the middle place between the cities of great industries and commerce such as Lyons, Paris, Marseilles, Bordeaux, and the cities of third rank, the conditions of the laborers are there perhaps more favorable than in any other place, it seems to us that we can not select a better example to illustrate clearly the conclusions to which we must arrive and to give them the character of absolute certainty.

“No one who has not stifled every sense of justice in himself can without great sadness, look upon the immense inequality which exists between the joys and sufferings in the case of the poor laborers; to live, for them, means merely not to die!

“The workingman sees nothing more beyond the crust of bread which he needs for himself and his family, nor beyond the bottle of wine, which for a moment dulls the consciousness of his sufferings, neither does he hope for more.

“Do you want to know how he lives? Then step into one of those streets where misery has huddled them together as the Jews, in the middle ages, were crowded into the quarters to which the prejudice of the people had assigned them. Stoop down if you enter one of these sewers which open on the street and are below the level of the pavement; the air is cold and damp, as in a cellar, your feet slip on the slimy earth, you are afraid of falling into the mud. On each side of the low hall and, consequently, under the ground, you find a dark, large, cold room; from the walls trickles dirty water and only one window gives access to air, too small to let the daylight enter and too poorly made to shut tightly. Open the door and walk in, if the foul air is not too repulsive, but take care, for the uneven floor is neither paved nor flagged, or else the stones are so thickly covered with layers of dirt, that it is impossible to see them. Two or three beds, worm-eaten and shaky, held together with difficulty by pieces of rope; a straw mattress, a ragged cover, seldom washed because it is the only one, perhaps a sheet and a pillow. Behold all that there is of the bed. Wardrobes are not needed in these houses. A spinning wheel and a loom Sometimes complete the furnishings.

“On the other floor the rooms are a little drier, a little lighter, but just as dirty and neglected. It is here, that, frequently with out fire, these men, during the long winter evenings, work by the light of a flickering pine splinter for fourteen hours a day in order to earn from fifteen to twenty sous.

[20]

“The children of this class live in the dirt of the street up to the moment when they are able to increase by a few pennies the income of their family through tiresome and brutalizing work; pale, swollen, their eyes red, bleared, so eaten away by scrofulous humor that they can scarcely use them, you could believe they came from an entirely different race than the children of the rich. The difference between the adults of the suburbs and those in the richer districts is not so evident—but a horrible process of selection has taken place; only the strong fruits have developed, while many fell from the trees before they were ripe. After twenty years one is strong or dead. We could add many sad instances, but the specification of expenses of this class of society will speak a still more audible language.

Lodging for one family.

“If a family earns 300 francs per year, according to this, 196 francs will remain for the food of a family of four or five persons who need, {FN10: It is peculiar that so careful a writer as Blanc should have permitted such an error to stand without comment. It could not have escaped his notice that 89 francs from 300 francs leaves 211 francs, but he did not correct it until a much later edition after his attention had been called to the fact that a footnote was necessary.] with all privations, at least 150 francs for bread. Forty-six francs remain to buy salt, butter, vegetables and potatoes, not to mention meat, the use of which is unknown. If you consider, that the tavern calls for a certain sum, you will admit that the condition of these families is horrible, in spite of the fact that a few loaves of bread are distributed from time to time by charitable institutions.”

We have proven with statistics to what excess of misery the application of the cowardly and brutal principle of competition has brought the people. But all this does not say enough. Misery begets something even worse; let us go to the heart of this sad discussion.

[21]

The ancients said, Malesueda fames, “hunger is a bad counsellor.” A horrible and true saying ! But if crime is born of misery, what engenders misery? We shall see directly. Competition is just as fatal to the safety of the rich as to the existence of the poor. For the one ceaseless tyranny, for the other a perpetual threat. Do you know where the greater part of the unfortunates come from who fill the prisons? From some great center of industry. The manufacturing districts furnish to the Grand Jury double the number of accused that is furnished by the agricultural districts. Statistics give on this point arguments to which we have no reply. What are we to think of the present organization of labor, of the conditions which are imposed on it, and the laws which dominate it, if the galleys are recruited from the work shops? Consider, in heaven’s name, the terrible words of M. Moreau Christoph: “In the present condition of society, theft, committed by the poor against the rich, is nothing but a reparation, that is to say, the just and reciprocal transmission of a piece of money, of a piece of bread, which returns from the hands of the thief to the hands of the one from whom it is stolen.”

“Thou art master of my money,” said Jean Sbogar, “I of thy life. This belongs neither to thee nor to me, give it up and I let thee go.” And now, ye philanthropists, go and invent some fine penal system. If you have found—with great trouble and work—means and ways of educating the criminal, then want, which awaits the prisoner when he steps out from our places of correction, remorselessly throws him back to crime. The accounts of the penitentiaries of New York show that one of every two discharged criminals is confirmed in his evil life. Ye sagacious physicians, keep the pest-stricken in the hospitals; to give him freedom only means to throw him back into the arms of pestilence, And where is the means to reform the criminal in prison? To come in contact with an incorrigible rogue is fatal for one who is still susceptible to reform. For vice has its standard of honor as well as Virtue. Shall we resort to isolation? What unhappy experiences ! In the state of Maine five out of eleven prisoners condemned to solitary confinement became sick, two suicided, the others became beastly idiots. This is the mortality of solitary confinement. You only have to look at the statistics. But what is the good of a remedy which has been studied with so much interest? Wait a moment and see what has been unquestionably proven. The condition of our prisons ought to be better than [22] that of our workshops. Shall there be a premium on theft? Society tells the poor: attack me if you wish that I should show my solicitude for you! Does this not sound like a joke? Well, this is anyhow the inevitable consequence of the industrial regime, where every factory becomes a school of corruption.

Other fatal consequences:–We mentioned that from individualism springs competition; from competition, fluctuation of wages and their insufficiency. Having reached this point, we come upon the next step, namely: the breaking of the family ties. Every marriage creates increasing expense. Why should poverty mate itself with poverty? The family gives way to illegitimate union. Children are born to the poor, how shall they be fed? This is the reason why we find so many of these un fortunate little creatures dead in dark corners, on the stairs of lonely churches, even in the vestibules of the buildings where laws are made. In order that there may be no doubt as to the cause of infanticide, statistics prove that the number of infanticides which are committed in the fourteen chief industrial departments of France to those of the whole country is in the ratio of 41 to 121.[FN11: Author’s Note—See the statistics published by the Constitution; of July 15, 1840.] The greatest evil is always found where industry has chosen its field of action. Ought not the state step forth and tell the poor mother:-I will take care of your children, I will open orphan asylums for them. Should this not be sufficient? No, it ought to go further, it ought to take away the reason which leads to the system of sterility. We have erected foundling asylums, we have given motherhood, which relinquishes its offspring, the benefit of secrecy. But who can now check the progress of unlawful union after the temptation of lust has been freed from the fear of burdens which it enjoins? Thus the moralists cry out! Their assertion is substantiated by the heartless statisticians, and their complaints are even louder. Suppress the foundling asylums, suppress them, if you do not want the number of foundlings to increase to such an extent that all of our united resources cannot suffice to sustain them. The increase in the number of foundlings since the erection of the asylums has been remarkable indeed! January 1, 1784, the number of foundlings amounted to 40,000; in 1820, to 102,103; in 1831, to 122,981; to day it has increased to 130,000.[FN12: Author’s Note—See the books of Mme. Huerne de Pommeuse, Duchâtel, Benoiston de Châteauneuf.] The proportion of foundlings [23] in the last forty years has almost tripled. How is it possible to check this great increase of misery? And what can we do to evade the ever increasing burden of taxes? I am sure that mortality ranges high in these institutions of modern charity; I am assured that many of these infants who are turned over to public benevolence, are killed by the keen air of the street as they come from their hovels, or by the heavy atmosphere of the asylum; it is not new to me that many others die gradually from insufficient food; for, of the 9,727 nurses of foundlings in Paris, only 6,264 own a cow or a goat; I know further that many of the children confided to wet nurses, die from the effect of the milk which other nurselings born in debauchery have poisoned,[FN13: Author’s Note—Philosophie du Buget by M. Edelstand Duméril.] yet even this mortality does not, alas, relieve us of our burdens. And if we ask now about the increase of taxes in figures, we find the expenditures from 1815 to 1831 have grown; Charente, from 45,232 fr. to 92,454; Landes, from 38,881 to 74,553; Lot-et-Garonne, from 66,579 fr. to 116,986; Loire, from 50,079 to 83,492 fr. And so on for the rest of France. In 1825 the Conseils Genereaux voted an appropriation of 5,915,744 fr. and the end of the year the deficit reached 230,418 fr. To make matters worse, the conditions of health in the foundling asylums better themselves from day to day; the progress in hygiene becomes a calamity! Great God! what conditions are these! And once more, I ask, what shall we do? Somebody has proposed that each mother who wants to hand over her child to the asylum, be submitted to the humiliating obligation of taking a policeman as her confessor. Indeed a fine invention! What can society gain when women have learned not to blush any more? If every youthful indiscretion shall have obtained its permit or if every act of libertinism shall have received a passport, what will happen next? Then through the necessity of this painful confession, the bridle will soon lose its curbing power; women will be raised to shamelessness, chastity will be relegated to oblivion, when the state sets its seal on the violation of all laws of modesty and decorum. Then it would certainly be better to fulfill the wish of many, and remove the foundling asylums. Impious demand! True, gentlemen, it is possible that you will find the taxes increased, but we do not want the number of infanticides to increase. The sum which burdens your budget horrifies you! But, we say, [24]

that when the daughters of the people do not find in their wages the necessary means of existence, it is no more than just that you should lose on one side what you have gained on the other. But is the family ruined through this? Certainly! See to it that labor is reorganized. For, I repeat, the utmost misery, the destruction of the family, is the consequence of competition. Strange fact! that the advocates of this regime should tremble at the shadow of each innovation and do not perceive that the maintenance of this system throws them by a natural and irresistible descent into the most audacious of modern innovations: into Saint-Simonism.

The penning up of children in factories is one of the results of the hideous industrial system. “In France, philanthropists of Mühlhausen submitted a petition to the chamber saying, children of all ages are employed in every cotton spinnery as well as in all the other industries; we found there children five and six years old. The number of hours of daily work is the same for young and old in the spinneries unless in a commercial crisis—this number is never less than 13 1/2 hours. Walk through an industrial town some morning, and look at the people who pour into the cotton mills! There you will see the unfortunate children, pale, delicate, starved, embittered, with dim eyes and hollow cheeks, breathing with difficulty, their backs bent like old men. Listen to the conversation of these children: their voices are rough and heavy, as if clogged by the unclean vapors which they are forced to inhale in the cotton factories.” Would to heaven that this description were exaggerated But these facts are based on observations, collected by conscientious men and entered in official reports. The proofs, moreover, are only too convincing. M. Charles Dupin has laid before the Chamber of Peers these facts; that in the ten départements most given to industry in France, for every 10,000 men called to the army, 8,980 were feeble or deformed; in the départements given to agriculture, only 4,029. In 1837, to get 100 men strong enough to endure the hardships of war, it was necessary to reject 170 in Rouen; 157 in Nimes; 168 in Elboeuf; 100 in Mühlhausen [FN14: Author’s Note—See the above cited statistics.]. These figures show the natural results of competition. In helping immeasurably to impoverish the workmen, we force them to find in their children an addition to their wages. Wherever competition dominates, it [25]

has been necessary to employ children. In England, for instance, the greater part of the workshops are filled by children. The Monthly Review, quoted by M. D’Haussez, estimates the number of laborers in the factories of Dundee who have not reached the age of 18 to be 1,078; but of these the majority are under 14; a great number under 12; some younger than 9 years, yes, even 6 or 7 year old children were employed.

If we accept the statement of the Ausland, quoted by M. Edelstand Duméril, the consequences of this terrible burden on childhood are as follows:—amongst 700 children of both sexes, picked at random, in Manchester, we found among the 350 not employed in factories 21 sick, 88 in poor health, 241 in full health; while of the 350 children working in factories, 75 were sick, 154 in poor health and only 145 in full health.

A system which forces the fathers to exploit their own children is a homicidal one. From the moral point of view can we think of anything more disastrous than to employ both sexes in factories? It means to inoculate the children with vice. Can we read, without horror, of the eleven-year old boy whom Dr. Cumins treated in a hospital for syphilis? And what conclusion shall we draw from the fact that the age in the English house of refuge averages eighteen years! We might multiply these sad proofs; in Paris for 12,607 women inscribed on the register of prostitutes the cities furnish 8,641; and all belong to the artisan class. M. Lorain, professor at the Collége Louis le Grand, has compiled a report as sad as it is remarkable, concerning the conditions of public schools in the kingdom. After minutely enumerating the odious victories of industry over education and its influence on the morals of children, he adds, that France is on the verge of being infected by the customs which have gained root in England, where, as a table of statistics in the Journal of Education has proven, in four days 144 children have frequented low dives. How is it possible without a reorganization of labor to stay the rapid decay of the population? By laws which regulate the employment of child labor in factories. This is now being tried. In France, the philanthropy of the law-makers is so great that the Chamber of Peers fixed the age at which a child may be made a part of a machine at eight years. According to this law, overflowing with love and charity, a child of eight years shall not be compelled to work longer than eight hours; nor a child of twelve years longer than twelve hours per day. This is only

[26] a plagiary of the “Factory Bill.” And what a plagiary! But, after all, this law must be obeyed; but how can it be possible? What shall the law-makers answer the unhappy father, who says to them: “I have children of eight and nine years; if you shorten their time of work, you diminish their wages. I have children of six and seven years, but no bread to feed them; you forbid me to send them to work, do you want me to let them starve?” The fathers are unwilling to shorten the hours, you cry out. Is it possible to force them? And on what law, on what point of justice should such a violence be based in the face of poverty? Under this law we cannot respect humanity in the child without outrageously insulting it in the father.

The Courier Français has lately admitted that this is a very serious difficulty; I readily believe it. Thus you see there is no remedy possible without social reform. Thus under the sovereignty of competition labor will bequeath to the future a generation decrepit, deformed, rotten, half gone into decay. O, ye rich ones, who will die for you in war? You must have soldiers!

But upon this annihilation of physical and moral capabilities of the sons of the poor, closely follows the annihilation of their intellectual faculties. Thanks to the imperious demands of the law, there are in every locality elementary teachers, but the necessary means for their support are granted everywhere with a shameful stinginess. Yet this is not all: not long ago, in travelling through the most civilized provinces of France, workmen whom we asked why they did not send their children to school, answered every time, that they sent them to the factories instead. Through personal experience we verified the truth of this generally acknowledged fact, which can also be read in the report of M. Lorain, a member of the University, who says liter ally:-“Wherever a factory, a spinnery, an arsenal, a workshop is opened, you may close the school.” What economic condition is this in which we find industry in a strife with education? And what success can a school show under such an economic condition? Go to the villages and see who are the teachers. Some times they are released convicts, vagabonds and adventurers, who pretend to be schoolmasters; sometimes half-starved teachers who like to exchange the plough for the ferrule and teach only be cause they have nothing better to do. Almost everywhere children are penned up in damp, unhealthy rooms. Yes, even in horse stables, where they profit at least in winter by the warmth which [27]

the animals give out. There are villages where the teacher keeps school in a room which serves him at the same time for kitchen, dining room, and bed-room. If the children of the poor receive an education at all, it is thus handicapped, and still these are the privileged ones. These details, let me emphasize again, are given by the official reports. Those writers who pretend that the people ought to be educated, say that without education no improvement is possible, that reform must begin there. The reply is very simple; if the poor man has to choose between school and work, his choice will not be doubtful for a single moment. A strong argument speaks for the factory which secures its preference; in school, the child is taught, but in the factory, paid. In this way under the reign of competition, the intelligence of the poor is stifled when they have scarce left the cradle; their hearts are ruined, their bodies are destroyed. Threefold sin, threefold murder!

But a minute’s patience, dear reader, I am soon at the end of my sorrowful evidence. It is an incontestable fact that the growth of population is considerably more rapid amongst the poor than the rich. According to the Statistique de la civilization européenne, the birth rate in the better districts of Paris is only 1/32 of the population, while in the poorer it is 1/26. This disproportion is a general fact and M. de Sismondi explains it very well in his work on political economy because of the impossibility of the day laborer to either hope for anything in the future or to provide for the future. Only he who knows himself master of tomorrow, can regulate the number of his children to his income; but he who lives from hand to mouth, subjects himself to the yoke of a mysterious fatality, to which he consecrates his progeny, because he himself has been consecrated to it. On the other hand, the asylums threaten society with an inundation of beggars. What remedy is there against this plague of the country? Yes, if pestilences were only more frequent, or peace would not last so long! For, in the present economic condition, annihilation is the simplest remedy But wars are becoming less and less frequent; cholera lets us wait so long; where shall all this end? And what shall we finally do with our poor? It is evident that any society in which food does not keep pace with the birth rate, is tottering on the edge of an abyss. France is in just such a situation. M. Rubichon, in his book entitled Social Mechanism, has proven this frightful truth beyond any doubt. It is true, [28]

poverty kills. According to Dr. Villermé, out of 20,000 individuals born at the same time, of whom 10,000 are among the rich and 10,000 among the poor, 54 per cent of the former and 62 per cent of the latter died before they reached the age of forty years. The number of people at the age of 90 years is in the rich district 82 and in the poor, 53 to 10,000 inhabitants. Vain remedy! This frightful remedy of death. Misery brings into existence more unhappy ones than it permits to reach maturity. Once more, which side shall we take? The Spartans killed their slaves; Valerius had the mendicants drowned, in France certain laws were passed in the sixteenth century condemning them to the gibbet.[FN15: Author’s Note—See the authors cited by M. Edelstand Duméril in his Philosophie du Buget, vol. 1, pp. 11.] We can take our choice between these just punishments! Why do we not embrace the doctrine of Malthus? Oh, but Malthus has not been logical, he has not carried his system to its logical conclusion. Let us adhere to the theory of the Livre du Meutre, published in England, February, 1839, or better still, to the pamphlet written by Marcus, of which our friend Godfrey Cavaignac has given an account, in which it is proposed to suffocate all children of the working classes after the third one, conditional damages being paid to the mother for this patriotic deed. You laugh? But it is a serious book which gives these proposals, written by an author philosopher. Whole volumes of commentaries have been written about it, the most important writers of England have discussed it, and finally condemned it with indignation for its hideous cruelty —and it is not at all a ridiculous book! It is a fact that England has no right to laugh at these blood-thirsty follies, this same England which found herself forced by the principles of competition to another immense extravagance to the poor-tax. Will our readers permit us to recommend to their meditations a few lines taken from E. Bulwer’s book:-England and the English:

“The independent day-laborer can buy with his wages only 122 ounces of food a week, including 13 ounces of meat.

“The healthy poor, who becomes a burden to the parish, receives 151 ounces of food per week, including 21 ounces of meat.

“The convict gets 239 ounces per week, including 38 ounces of meat.”

In other words, the material condition of the convict in England is more favorable than that of the recipient of charity, and his position is again better than that of the honest laborer. That is [29] monstrous, is it not? Well, it is only a necessity. England has laborers, but not so many as inhabitants. But as they can only choose between the maintenance of the poor or their annihilation, the English law makers have decided for the first; they did not have as much courage as Emperor Valerius, that is all. It only remains to ascertain if the law makers of France, in the face of all this, considered in cold blood the terrible consequences of the economic regime which they borrowed from England. I insist upon this point! Competition breeds misery; and this fact is proven by figures. Misery is dreadfully prolific, this fact is proven by figures. The fertility of the poor throws unfortunates into society who ought to work, but who can not find work; this fact is also proven by figures. Once arrived at this point, Society cannot act otherwise than to kill the poor or to feed them free! Cruelty or madness!

[30]

CHAPTER III. COMPETITION IS THE CAUSE OF THE DECLINE OF THE BOURGEOISIE↩

I could stop here. A society like the one I have just de scribed is in peril of civil war. What does it matter that the bourgeoisie congratulates itself that lawlessness has not yet reached its heart, when anarchy already lies threatening at her feet. But does not the reign of the bourgeoisie harbor in itself all elements of an early and inevitable dissolution?

Cheapness is the big word which, according to the school of economists of Smith and Say, embraces all benefits of free competition; but why do we stubbornly refuse to take into consideration the results of cheapness and its relation to the momentary usefulness which the consumer derives from it? Cheapness benefits only those who are consumers, while it sows amongst the producers the seeds of destructive anarchy. Cheapness is the bludgeon with which the rich producer fells the less fortunate. Cheapness is the trap into which the bold speculators lure industrious workingmen. Cheapness is the death sentence of the manufacturer who is not able to advance the money for a costly machine which his wealthy rival is able to have. Cheapness is an ambush in which monopoly lies in wait; it is the death-knell of the small industry, for the small trade, the small property; in one word, it is the destruction of the bourgeoisie in favor of an industrial oligarchy.

Shall cheapness be condemned altogether? Nobody will dare to suggest such an absurdity. But it is the peculiarity of false principles that they change good into evil and corrupt all things. In the system of competition cheapness is only a temporary and apparent benefit. It is only maintained so long as the combat is raging; as soon as the stronger has overcome all his rivals, the prices rise. Competition leads to monopoly for the same reason that cheapness leads to exorbitant prices. Thus that which has been an instrument of war, used by the producers amongst themselves, becomes now—sooner or later—the cause of impoverishment for the consumer. Combine all these causes with those which we have already enumerated, first of all the [31] unregulated increase of the population, and we shall have to accept the fact that the impoverishment of the masses of consumers is an evil which is the direct result of competition.

On the other hand, this competition, which aims to dry up the sources of consumption, forces production to a destructive activity. The confusion resulting from the general conflict of interests, takes away from the single producer the knowledge of the state of the market. Groping in the dark, he is dependent on chance alone for the sale of his products. Why should he curb his production as long as he can make up his losses in the exceptionally elastic wages of his laborers? We see daily that manufacturers continue the work, although at a loss, because they do not want to diminish the value of their machinery, their tools, their raw materials, their buildings and furthermore not lose their customers, and because they—like the gambler, do not care to lose the possibility of a lucky winning in industry, which, under the domineering power of competition, is scarcely anything else than a game of chance.

Therefore we cannot often enough insist upon this result, that competition forces production to increase and consumption to decrease; thus it goes directly in opposition to the reasonable purpose of economic science; it is at the same time oppression and madness.

When the bourgeoisie rose against the old power and saw it sink to the ground under its heavy blows, it declared that these old powers had been stricken with blindness and ignorance.

Well, today the bourgeosie is in the same position, for it does not perceive how its own blood flows nor how it is tearing at its vitals with its own hands.

Yes, the economic order of today threatens the property of the middle class, as it has also destroyed in a cruel manner the property of the poor.

Who has not read of the lawsuit to which the fight between the Messageries françaises and the Messageries royales and the Messageries Lafitte and Caillard had given cause? What a law suit! How it laid bare all the weak points of our economic conditions. And yet this lawsuit passed by practically unnoticed. They have paid less attention to it than they would have given to any commonplace parliamentary debate. The most astonishing thing, the most incomprehensible in connection with this lawsuit is the fact that nobody drew the conclusion from it which it [32] naturally offered. What was it all about? Two companies were accused of uniting to destroy a third one. This created a great disturbance. Law had been violated, that protecting law which in order to prevent oppression, prohibits coalitions whose purpose is to prevent the oppression of the weak by the strong. Is this not a most wretched condition? What! The law forbids him, who possesses 100,000 fr. to consolidate with another who has 100,000 fr. against some one who has just as much, be cause this means the unavoidable destruction of the latter, and this same law permits the owner of 200,000 fr. to wage war upon him who has only 100,000 fr. Wherein lies the difference between these two cases? Is it not here as there the war of the greater capital against the lesser? And is it not always the fight of the strong against the weak? And is this fight not always an odious warfare because of its inequality? What a contradiction! One of the lawyers pleading in this celebrated case said: “It is permissible for any one to ruin himself in order to ruin others.” The statement is true under present conditions and is found to be very correct. THAT IT IS PERMISSIBLE FOR ANY ONE TO RUIN HIMSELF IN ORDER TO RUIN OTHERS!!!

What do the present statesmen think and expect when they cry out convinced of the imminence of the peril as did lately the Constitutionnel and the Courrier Français:

“The only remedy consists in driving this system to the extreme, to throw down everything that opposes its complete development; in short to complete the absolute freedom of industry, through the absolute freedom of commerce.” What! is that a remedy? Do you call the enlargement of the field of battle the only means of avoiding the misery of war? What! are there not industries enough which ruin themselves; will you add to this lawlessness the incalculable complications of a new means of destruction? This is the road that leads to chaos.

We can less easily understand those who imagine that any mysterious combination of two opposite principles would be possible. It is a very poor idea to try to graft association on competition, this would be about the same as if we should take hermaphrodites to replace eunuchs. The association is a progress only when it finds universal application. In the past few years we have seen many profit-sharing societies develop. Who does not know their scandalous histories? If one individual fights against another individual, or one association against another [33] one—it is always war, always a reign of violence which makes use of deceit and tyranny with hypocrisy. What else is the association of capitalists amongst themselves? Here are the laborers, who are not capitalists, what are you going to do with them? As associates you reject them, do you wish to make enemies of them?

Do you mean to say that, the extreme concentration of personal property, neutralized and lessened by the principle of division of inheritances and that the power of the bourgeoisie, if destroyed by industry, can be reestablished through agriculture? What an erroneous idea. The excessive division of real estate must, if we do not take care, lead us back to the reconstruction of the great landed estate. We seek in vain to deny this; the parcelling of soil, small proprietorship, the spade instead of the plow, dull routine, labor unaided by science. Parcelling of soil deprives agriculture of machinery as well as of capital. Without machinery there is no progress; without capital no stock. How can—under such circumstances—small farms endure the competition of the larger ones without being absorbed? The result has not yet been shown, because minute division of land has not been carried out to its farthest limits. But have patience! See what is happening in the meantime ! Every small proprietor is a day laborer; for two days in the week he is his own master, the other time he is the slave of his neighbor. And if he ever has the wish to enlarge his property, he steps so much nearer to complete servitude. And thus it happens that the farmer, who owns only a few acres of poor land, which barely brings 4 per cent if he works it himself, can seldom withstand the temptation to enlarge his property if he has a chance. He takes a mortgage on it at 10, 15 or 20 per cent. For if there is no credit in the country, usury steps in and takes its place. The results are evident! The figures in France of real estate indebtedness amount to 13 thousands of millions. This does not mean anything else but that side by side with those capitalists who become captains of industry, a handful of mere usurers start up who try to make themselves masters of the land. Thus the bourgeoisie advances towards dissolution in the cities as well as in the country. From all sides it is threatened, its position undermined, and its existence destroyed.

To avoid commonplaces and cheap truths I have not mentioned the horrifying moral corruption with which industry in the [34] present order, or better, disorder, has harrassed the bourgeoisie. Everything has become salable and competition has invaded even the domain of thought.

Thus factories ruin trades; commercial houses absorb the modest little ones; the tradesman, who is his own master, is replaced by the day laborer who is not his own master; cultivation by means of the plow gives way to the spade; and the field of the poor falls under the shameful control of the usurer; failures of business houses become more numerous; industry is transformed through the poorly regulated extension of credit to gambling in which the gain is assured to no one, not even to the scoundrel. Finally this vast disorder which is created especially to awaken in the souls of every one jealousy, suspicion and hatred, and by and by to stifle all nobler feelings and to dry up all scources of faith, devotion, and poetry, this is the despicable but too truthful picture of the results due to the application of free competition.

We have borrowed this wretched system from the English. Let us see at a casual glance what this system has done for the glory and prosperity of England.

[35]

CHAPTER IV. COMPETITION CONDEMNED BY THE EXAMPLE OF ENGLAND↩

Englishmen say that capital and labor are by nature two antagonistic powers; how can we force them to live side by side and aid one another? For this there is only one remedy; the laborer must never lack work; the employer, on the other hand, should always find—in the ready market for his product—the means to pay work accordingly. Does not this solve the problem? Who will have the right or the heart to complain in case production should finally become active and consumption finally elastic! The wages of the one will always be sufficient, the profit of the other always satisfactory. Let us then, open the doors of the infinite to human activity, nothing will limit its enthusiastic flight. Let us proclaim “laissez faire” honestly and without restriction. Is England’s production not sufficiently varied to afford commerce a larger career? Well, we shall find sailors and construct ships which will give us the commerce of the world. Do we live on an island? Well, then, our ships give access to all continents. Is not the amount of raw material produced by our country too limited? Very well, then let us seek raw materials at the end of the world. All nations will become consumers of the products of England, which will work for all people. To produce, always to produce and to solicit other nations by every means to induce consumption, is the work which the power of England will employ. This will make her rich; this will develop the genius of her sons.

A gigantic plan A plan almost as egoistic as absurd, and still one which England, for two centuries, has followed with incredible perseverance! Oh, surely, to be shut up on a little, not very fertile, foggy island, and to go forth from there one day to conquer the universe, not with soldiers but with merchants, to send thousands of ships to the East, to the West, North and South, to teach hundreds of countries the use of their own treasure, to sell America the products of Europe, and Europe the riches of India; to bind all nations to her existence and to fetter them in some way to her girdle by the innumerable ties of a world-spanning [36] commerce; to find in gold the power capable of balancing the sword, and in Pitt the man capable of making the audacity of a Napoleon hesitate; and in all this is a quality of greatness, which dazzles and astonishes the mind.

But what has England not dared to accomplish her end! Up to what point has she not pushed the rapacity of her hope and the madness of her pretentions. How has she conquered Issequibo and Surinam, how Ceylon and Demerary, how Tobago and St. Lucia, how Malta and Corfu-enmeshing the whole world in the immense network of her colonies? We know how she has settled herself in Lisbon since the time of the Methuen Treaty, and by what abuse of power she has founded in India her commercial tyranny; side by side with the sovereignty of Holland, mixed with the debris of the colonial structure erected by Vasco de Gama and an Albuquerque. No one denies the damage which her cupidity has imparted to France; every one knows by what strategems, by what perfidious instigations she has always known how to drench the Spanish colonies in America with blood. What shall we say about the violence by which England has secured the empire of the sea for so long? Has she ever respected the rights of neutral countries or even acknowledged them? Has the right of blockade as exercised by England not become the most arrogant of tyrannies? And has she not made the right of search the most odious of all brigandage? And what is the purpose of all this? Only to have—let us repeat it—raw materials for the manufacturer and to serve her customers. This thought has been the dominating one in England for two centuries, that in her colonies the culture of articles of food, such as rice, sugar, coffee, were neglected, while to the culture of cotton and silk a feverish attention was given. But why? While England put exorbitant, and we might say homicidal, duty on the importation of food stuffs, she opened to all raw materials her ports almost free of duty, a monstrous anomaly, which induced M. Rubichon to say, “Of all the nations of the world the English have worked most and fasted most.”

To this leads a merciless political economy of which Ricardo has so complaisantly announced the premises and of which Malthus has drawn with the utmost sangfroid the horrible conclusion.

This political economy carried the germ of vice in itself, which will render it fatal to England and to the whole world. [37] It advanced the theory that nothing was of importance but to try to find consumers; it was necessary to add, solvent consumers. But how dare they awaken a wish, without the possibility of its fulfillment? Could we not foresee that England, while substituting her activity for the activity of those nations whom she wished to have as her consumers, must end with the destruction of these people, because she closed for them the source of all wealth, namely, labor? Could England pose exclusively as the producing nation and hope at the same time that her wares would find a continuous market amongst the peoples that became exclusively her consumers? This hope was evident madness. The day will dawn when the English will perish from prosperity by causing the others to perish from poverty. The day will dawn when the consuming nation cannot find raw material in exchange; and what will this mean to England? The glut of markets, the ruin of numerous factories, the misery of the whole mass of laborers, the universal destruction of credit.

In order to know how far the carelessness, the folly of production goes, we need only to search the history of England’s trade and commerce. At one time English merchants sent to Brazil, where they had never seen ice, whole ship loads of skates;[FN16-1: Author’s Note—1. Mawe, Travels in Brazil.] at another time, Manchester exported to Rio de Janeiro[FN16-2: ibid.] more wares in one week than they have used in the last twenty years. Everywhere production in using her sources of help in an exaggerated way, cripples her activity without rendering herself account of the possible consumption of her production.

But again, to cause a nation to entrust to another the care of developing elements of labor which it possesses, means to gradually take away the capital and to impoverish it, and consequently to make it more unfit for consumption, as it can only consume that for which it is able to pay. The general impoverishment of other nations which England has needed in order to have her products consumed, is the vicious circle in which England has been moving for the past two centuries; this is the mistake, the deep, incorrigible error of her system. Thus (we insist upon this point of view because it is the most import ant), England has brought herself to a strange position, unique in history; to bring about for herself two equally effective causes [38] of ruin, the one in the work of the people, the other in their inertia; this labor creates competition for her which she cannot always conquer; their inertia, takes from her her consumers with out whom she cannot get along.

This has already happened on a small scale, but inevitably will happen on a larger one. What losses has not England already sustained because her products have grown with a greater rapidity than the articles which the other nations would exchange for them? How often has England not produced, after many warnings, the results of which have cruelly punished the extravagance of overproduction. We cannot so soon forget the great crisis, which terminated in the English intrigues in the countries lying between Mexico and Paraguay. Scarcely had the news reached England that a field had been opened for industrial adventures in South America, when all hearts beat immediately with joy, and every brain was excited. All heads were turned. The production in England was never in such a paroxysm of frenzy. If the speculators were to be believed, only a few days and a few ships were necessary to transport all the immense wealth which America possessed to Great Britain. The confidence was so great, that the bankers hastened to coin money, hoping to have the first returns. And what was the result of this great movement? They had calculated on everything except the existence of articles of exchange and the facility of transporting them. America kept her gold, which they could not extract from her mines; that country, which had been devastated by fire and sword, had nothing to give in exchange for the merchandise brought to her—neither cotton nor indigo. England knows as well as Europe what this great mistake has cost her both in millions and in tears!

Let no one say that we drew the conclusions from the exceptions to the rule. The evil we have pointed out has given rise to all the evils in its train. For, while England exhausted herself colonially in incredible efforts to render the whole universe tributary to her industry, what spectacle has her inner history offered to an attentive observer? Workshops succeeded workshops, the invention of to-morrow succeeded the invention of yesterday; the furnaces of the North ruined by those of the West; the laboring population increased beyond all measure under the stimulus of a limitless competition; the number of cattle, which as food of man, fell far behind the number of horses, which men [39] were obliged to feed; the bread of charity replaced, little by little, the bread of labor; the poor-tax was introduced and served to increase poverty. In short, England presented to the surprised and indignant world a spectacle of extreme misery, hatched under the wings of extreme opulence. Such are the results due to a public policy which is based on the principle of national egotism: England had to seek consumers everywhere and at any price.

And to obtain these horribly disastrous results, how many injustices had England to commit, how often to encourage treason, to sow discord, to foment wars, subsidize iniquitous coalitions and combat glorious ideas!

I do not wish to go any further, I will try to end this sad history, so that no one can accuse me of wanting to insult the strong old English race. No, I can and will not forget that England, in spite of the evil which she has done to the world and to my country, can claim for herself, in the history of nations, many immortal pages; that England, before all other peoples of Europe, has been visited by freedom, that her laws, even under the yoke of an overbearing aristocracy, have rendered sincere and solemn homage to the dignity of mankind; that from her bosom came forth the wildest but also the most powerful cry that was ever raised against the tyranny of the papacy, united with that of the inquisition; that she is even to-day the only country which the furies of political life have not rendered inhospitable and fatal to the weak. For there, at least, you found an asylum, you poor noble exiles, unconquered but wounded champions; there you reassembled the remnants of your fortunes, there you found the life of the soul and intellect, perhaps the only thing which the rage of our enemies left you in your great disaster. And from there you followed the thoughts of a people who were as unhappy, as much in exile, as you; for had they not to search for their fatherland, though they lived in its midst, but alas! could not recognize it in its degradation?

In addition England has made full expiation. There is, says a new writer, a penal code for the nations as well as for the individual. This truth has been grieviously proven in the history of England. Where is her power to-day? The empire of the seas eludes her. Her possessions in the Indies are threatened. Not so long ago the English Lords almost held the stirrup [40] of the victor of Toulouse, whom they dared no longer call the victim of Waterloo.

And what has become of the English aristocracy, the most vigorous and most splendid of the world? Who are, indeed, her leaders? Is it Lord Lindhurst, the son of an obscure painter, or Sir Robert Peele, the son of a cotton manufacturer, created Baronet by Pitt? Or Lord Wellington, this feeble offspring of the Irish race and the bourgeoisie of the Wellesley’s? These are the heads of the English aristocracy, they are the ones who lead it and govern it and represent it. And these men are not even of her blood!

Not long ago the Marquis of Westminster said in the House of Lords: “They tell us we should sacrifice one fifth of our revenues, we, the possessors of the soil of Great Britain’ Are those who say this ignorant of the fact that the other four fifths belong to our creditors?”

The exaggeration of these words is evident. Unfortunately, it is only too true that the inalienability of fiefs in England protects the larger part of the income of the English noblemen against every loss, and these revenues are immense. If they amount—as it seems certain—to 135 millions for the 500 families of the Peers of England and to one billion three hundred millions for the four hundred thousand people who compose the families of baronets, knights and the gentry, we have to acknowledge that the British nobility knew how to seize a very good part of the spoils of the globe! But we have seen what a powerful menace hangs over English commerce. The aristocracy is a sleeping partner in all the industries, and it is easy to predict that the material punishment will not be long delayed.