As part of my “Farewell to America” tour in January 2020 I gave the following talks and papers on my way back to Australia:

- On Bastiat at the Political Economy Project at Dartmouth College, New Hampshire

- On Bastiat at the American Institute for Economic Research, Great Barrington, Massachusetts

- On classical liberal class analysis at the Adam Smith Center and the School of Social Sciences, Singapore Management University

- On the history of the classical liberal tradition at the Mannkal Economic Education Foundation, Perth, Western Australia

[David’s lecture on Bastiat at the AIER]

(1.) Dartmouth College: “Bastiat’s Economic Harmonies: A Reassessment after 170 Years.”

At Dartmouth College, New Hampshire: “Bastiat’s Economic Harmonies: A Reassessment after 170 Years.” A paper given to the Political Economy Project at Dartmouth College, Hanover, New Hampshire (7 Jan. 2020). This paper is a summary of what I have learned about the originality and importance of Bastiat as an economic theorist after having completed the manuscript of volume 5 of the Collected Works of Bastiat for Liberty Fund in September 2020. It builds upon a “Liberty Matters” discussion I organised on this topic earlier in the year when I invited leading scholars of Bastiat’s economic thought (Donald J. Boudreaux, Guido Hülsmann, and Joseph T. Salerno) to give their assessment of his work. See the discussion. In my paper I talked about Bastiat’s importance as a leading classical liberal figure and the striking radicalism of his thought. I also explain why I think he is underrated as an economic, political, and social theorist but justly recognised as one of the greatest economic journalists and popularizers of economic ideas who has ever lived. I include in the paper a number of key passages from his writings to illustrate my claims. See the paper in HTML and PDF; and also the lecture slides PDF. The talk was videoed but has not been released to my knowledge.

(2.) American Institute for Economic Research, Great Barrington, Massachusetts: “Bastiat on Harmony and Disharmony”

At the American Institute for Economic Research, Great Barrington, Massachusetts. Here I gave a paper on my reconstruction of what Bastiat’s great unfinished works on Harmony and Disharmony might have looked like had he lived long enough to complete them. These never finished works might rank alongside Lord Acton’s much anticipated History of Liberty as one of the most important classical liberal books never written. I also was interviewed by Jeff Tucker on the importance, originality, and radicalism of Bastiat which appears as a three part podcast.

“Bastiat on Harmony and Disharmony” – a talk given at the AIER (20 January, 2020). In this nearly book-length paper I explore the connection between harmony and disharmony in the thought of Bastiat. The interconnections between the two show that Bastiat was never a crude “optimist” as many of his critics have argued. Given the presence of “plunder” and “disharmony” in human relations throughout history Bastiat understood that harmony could and had been disrupted or prevent from occurring – hence his desire to write a book on The History of Plunder to explain how this had taken place and what it had meant for human flourishing. In spite of these impediments, the potentially “harmonious” nature of human relationships kept bursting through in the form of markets and other social interactions between individuals. He thought this needed to be described and explained in at least two works – one on “social harmony” broadly understood (legal, social, political), and another on the very important subset of harmony, namely “economic harmonies”. In Bastiat’s theory of history there was a constant tension between the forces or factors tending towards “disharmony” (disturbing factors) and those tending towards “harmony” (restorative factors) which I explore in some detail. The end result I believe is a very sophisticated and rich social theory which has not been properly appreciated by historians of thought in general and libertarians in particular. See the lecture in HTML and PDF 5.9MB; as well as the lecture slides PDF. The video of the proceedings is here and on Youtube.

Following the talk, I was interviewed by Jeff Tucker on the life and thought of Frédéric Bastiat which appears in three parts.

- Part 1: “Who was Claude-Frédéric Bastiat?” Part1

- Part 2: “Who was Claude-Frédéric Bastiat” Part 2

- Part 3: “Insights into Bastiat’s Libertarianism” Part 3

(3.) Singapore: “Understanding Class Divisions in Society: A Classical Liberal Approach”

In Singapore I gave a talk on how classical liberal class analysis can explain many of the divisions which have arisen in modern societies; and was interviewed on the history of the classical liberal tradition and what this political tradition still has to offer us today.

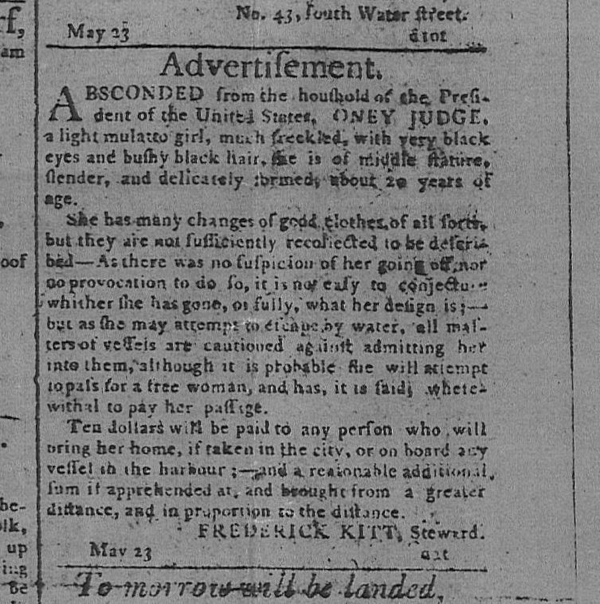

“Understanding Class Divisions in Society: A Classical Liberal Approach”. This talk is part of the Philosophy, Politics and Economics (PPE) Series co-organised by the Adam Smith Center and the School of Social Sciences, Singapore Management University (20 Jan. 2020). According to socialists and Marxists, tensions and conflicts within society are the result of the very essence of the existence of private property and free market relationships between individuals (especially wage labour). In a “capitalist” society these tensions become so great that they give rise to “classes” which contend for power and profits and eventually result (according to the Marxists) in class warfare and ultimately revolution. The classical liberal tradition on the other hand also has a theory of class and class conflict, but these tensions and conflicts are the result of political and other coercive interventions in the economy. In this talk I explore the kinds of problems and tensions created by government intervention the economy, how they give rise to “class conflict” (class here being defined politically rather than economically), and how this different way of looking at the world can help us understand and explain the cause of many tensions and conflicts which are afflicting societies today. The five examples of social tensions and conflicts caused by governments which I discuss in the talk include:

- different groups fighting over control of limited resources (taxes) in order to get benefits for themselves

- different groups trying to get laws passed by the government to further their own vision of “the good society” and to exclude or harm groups they oppose

- different regions of nation states trying to free themselves from central control and taxation, and seeking autonomy

- groups which oppose the “capitalist system” (the free market and liberal society) and which seek to either overthrow it or radically change it so it conforms to their ideas of how a future society should be structured and run

- the most powerful groups in society who wish to use the power of the state to pursue their own interests at an international level

See the lecture in [ HTML ] and [ PDF ]. A video of the talk is on Facebook.

I was also interviewed by Bryan Cheang, head of the Adam Smith Centre , on the history of the classical liberal tradition (not yet online).

(4.) The Mannkal Economic Education Foundation, Perth, Western Australia: “An Introduction to the Classical Liberal Tradition: People, Ideas, and Movements”.

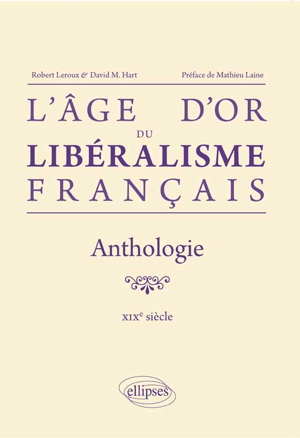

“An Introduction to the Classical Liberal Tradition: People, Ideas, and Movements”. A talk given at the Mannkal Economic Education Foundation, Perth (30 January, 2020). In this talk I survey for Mannkal’s incoming students (for northern hemisphere readers the academic year in Australia starts at the end of summer, i.e February/March) the long history of the classical liberal tradition and its key ideas. I discuss the long history of the Classical Liberal tradition (CLT) which goes back over 400 years; how it has evolved over this period in reaction to the different kinds of oppression people have suffered under; and the problem we in the present face with defining what is meant by “liberalism” (hence the need for what I call “hyphenated” liberalism.” I argue that there have been 4 main periods in the evolution of CL ideas, beginning in the 1640s and continuing into 1680s (the English Civil War and Revolution in the 1640s (1647-49); and the “Glorious Revolution” of 1688-89); the 1750s-1790s (the “trans-Atlantic” Enlightenment and the American and French Revolutions; the liberal reforms of the19th century 1815-1914 (the period of so-called “Classical Liberalism”; and the post-WW2 liberal / libertarian renaissance. I argue that there are two sets of ideas wee have to take into account: the things CLs were Against and the things they were For. It is in relation to the latter that I present my list of the “Twelve Key Concepts of CL”. Although the achievements of the CLT have been immense, it seems that that CL might be losing the battle of ideas today.

I have given versions of this talk for over a decade and I am currently re-writing and expanding it (as well as adding a section on liberalism in Australia). See the documents listed here “Study Guides on the Classical Liberal Tradition”, especially the section on “The 12 Key Concepts of Liberty”. An important summary of CL ideas and movements can be found in the Cato Institute’s The Encyclopedia of Libertarianism (2008) which is now online, along with my selection (with links) of the key entries and also here.

See also the PDF of my Mannkal talk overheads and Further Reading.

In addition to the talk, I ran a workshop for the Mannkal students in which we conducted a close reading of my new translation and edition of Bastiat’s perhaps best-known essay “The Law” (1850). See “Frédéric Bastiat, The Law (June 1850): A New Translation by David M. Hart with a Reader’s Guide to the Text” (with discussion questions and key passages) PDF.