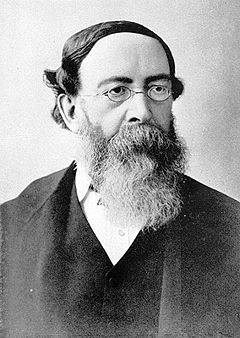

William Edward Hearn (1826-1888)

This is part of a collection of Australian Classical Liberals and Libertarians.

For information about William Edward Hearn (1826-1888) see:

- James Williams, "Hearn, William Edward", Dictionary of National Biography (1885-1900), vol. 25, p. 335.

- J. A. La Nauze, "Hearn, William Edward (1826–1888)" Australian Dictionary of Biography, Volume 4, (Melbourne University Press, 1972). <http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/hearn-william-edward-3743>.

- Murray N. Rothbard, An Austrian Perspective on the History of Economic Thought. Volume II: Classical Economics (Auburn, Alabama: Ludwig von Mises Institute, 2006). "14.8 Plutology: Hearn and Donisthorpe," pp. 463-65.

- David Kemp, A Free Country: Australia’s Search for Utopia, 1861–1901 (Melbourne: The Miegunya Press, 2019). Section on Hearn in Chap. 10 “Liberalism and the New Economics.”

James Williams, "Hearn, William Edward", Dictionary of National Biography (1885-1900)

Source: James Williams, "Hearn, William Edward", Dictionary of National Biography (1885-1900), vol. 25, p. 335. <https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Dictionary_of_National_Biography,_1885-1900/Hearn,_William_Edward>.

HEARN, WILLIAM EDWARD, LL.D. (1826–1888), legal and economical writer, born, 22 April 1826, at Belturbet, co. Cavan, was son of the vicar of Killague in the same county. He was educated at the royal school at Enniskillen and Trinity College, Dublin, where he was first senior moderator in classics and first junior moderator in logic and ethics. After being professor of Greek in Queen's College, Galway, from 1849 to 1854, he was in the latter year nominated as the first professor of modern history, modern literature, logic, and political economy in the new university of Melbourne. He was called to the Irish bar in 1853, and to the bar of Victoria in 1860. On the reorganisation of the school of law in 1873 he resigned his professorship and became dean of the faculty of law, and from May to October 1886 was chancellor of the university. In 1878 he was elected to represent the central province of Victoria in the legislative council. While in parliament his energies were mainly devoted to codification of the law. In 1879 he introduced the Duties of the People Bill, a code of criminal law; in 1881 the Law of Obligations Bill, a code of duties and rights as between subject and subject; in 1884 the Substantive General Law Consolidation Bill. All these bills were in 1887 referred to a joint select committee of both houses for report, and their adoption was recommended, but owing to Hearn's ill-health they were dropped for the time. Hearn was a member of the church of England, and as a layman took a prominent part in the working of the diocese of Melbourne. In 1886 he was appointed Q.C. He died 23 April 1888.

Hearn wrote:

1. 'The Cassell Prize Essay on the Condition of Ireland,' London, 1851.

2. 'Plutology, or the Theory of the Efforts to satisfy Human Wants,' 1864.

3. 'The Government of England, its Structure and its Development,' 1867; 2nd edit. 1887; an important and valuable work, which is referred to by Mr. Herbert Spencer as one of those which have helped to graft the theory of evolution on history.

4. 'The Aryan Household, its Structure and its Development; an Introduction to Comparative Jurisprudence,' 1879; his most important work, which, in the author's words, was intended 'to describe the rise and the progress of the principal institutions that are common to the nations of the Aryan stock.'

5. 'Payment by Results in Primary Education,' 1872.

6. 'The Theory of Legal Rights and Duties; an Introduction to Analytical Jurisprudence,' 1885.

Hearn also made some brilliant contributions to the local press.

[A very full obituary notice is contained in the Australasian of 28 April 1888; Athenæum, 28 April 1888; Brit. Mus. Cat.]

Murray N. Rothbard, "14.8 Plutology: Hearn and Donisthorpe" (2006)

Another forerunner and contemporary hailed by the revolutionary marginalist Stanley Jevons was the Irish-Australian economist, William Edward Hearn (1826–88). Born in County Cavan, Ireland, Hearn was one of the last students of the great Whatelyite economists at Trinity College, Dublin, entering in 1842 and graduating four years later. There he learned an economics very different from the dominant Millian school in Britain, an economics steeped in subjective utility theory and a catallactic focus upon exchange. Made the first professor of Greek at the new Queen’s College, Galway in Ireland at the age of 23, Hearn received an appointment five years later, in 1854, as professor of modern history, logic and political economy as well as temporary professor of classics at the new University of Melbourne, Australia. In a country otherwise devoid of economists, Hearn had little incentive to pursue economic studies; he became dean of the law faculty and chancellor of the university. Most of his scholarship was devoted to such diverse subjects as the condition of Ireland, the government of England, the theory of legal rights and duties, and a study of the Aryan household, on all of which he published books issued in London as well as Melbourne. Hearn also served as a member of the legislative council“ of the state of Victoria and as leader of the Victoria House.

Hearn wrote only one book in economics from his eyrie in Australia, but it proved highly influential in England. Plutology, or the Theory of the Efforts to Satisfy Human Wants, was published in Melbourne in 1863 and reprinted in London the following year.(44) ‘Plutology’ was a term that Hearn adopted from the French laissez-faire economist J.G. Courcelle-Seneuil (1813–92), in his Traité théorique et pratique d’économie politique (1858) to mean a pure science of economics, a scientific analysis of human action. There are, indeed, hints in Hearn that he sought a broad science of human action going beyond even the limits of catallactics, or exchange.(45)

Hearn’s Plutology was patterned after Bastiat. Like Bastiat, Hearn provided a Harmonielehre, demonstrating the ‘unfailing rule’ that the pursuit of self-interest produces a flow of services on the market in the ‘order of their social importance’. Like Bastiat, Hearn began with a chapter on human wants, the satisfaction of which is central to the economic system. Human wants, Hearn pointed out, are hierarchically ordered, with the most intense wants satisfied first, and with the value of each want diminishing as the supply of goods to fulfil that want increases. In short, Hearn came very close to a full-fledged theory of diminishing marginal utility. Since each party to every exchange gains from the transaction, this means that each person gains more than he gives up – so that there is an inequality of value, and a mutual gain, in every exchange.

The value of every good, showed Hearn, is determined by the interaction of its utility with its degree of scarcity. Demand and supply thereby interact to determine price, and competition will tend to bring prices down to the minimum cost of production of each product. Thus Providence, through competition, brings about a beneficent social order, a natural harmony, through the free market economy.

In all these doctrines, Hearn anticipated the imminent advent of the Austrian School of economics, as well as echoing and building upon the best utility/scarcity/harmony-mutual benefit analyses of continental economics. Also anticipating the Austrian School, and building upon Turgot and various nineteenth century French and British writers including John Rae, was Hearn’s analysis of entrepreneurship. The entrepreneur contracts with labour and ‘capital’ (i.e. lenders) at a fixed price, attains full title to the eventual output, and then bears the profit or loss incurred by eventual sale to the particular entrepreneur at the next stage of production.

Hearn also showed that capital accumulation increases the amount of capital relative to the supply of labour, and therefore raises the productivity of labour, as well as standards of living in the economy. He saw that capital could accumulate, and therefore living standards could increase in the economy, without limit. In addition, Hearn generalized the law of diminishing returns, expanding it from land to all factors of production, being careful to assume a given technology and supplies of natural resources.

A champion of free trade, William Hearn called for the removal of Catholic disabilities in Britain, the freeing of the “Irish wool trade, the abolition of usury laws and entail, and the removal of all restrictions on transactions in land. Opposing government intervention, Hearn declared that government’s only function is to preserve order and enforce contracts, and to leave all other matters to individual interest.

Hearn’s Plutology was used as an economics text in Australia for six decades until 1924 – indeed it was virtually the only work on economics published in Australia until the 1920s. While the book went unnoticed upon its publication in London in 1864, it soon drew high praise from several economists, especially Jevons, who hailed it as the best and most advanced work on economics to date. Jevons featured Plutology prominently in his path-breaking ˆ (1871). Apart from these citations, however, Hearn’s work gave rise to only one plutological disciple. The attorney and mine-owner Wordsworth Donisthorpe (1847-?) published his Principles of Plutology (London: Williams & Norgate, 1876), which apparently was mentioned by no economic work from that day until the publication of the New Palgrave in 1987, either in the literature of the time or in any of the histories or surveys of economic thought. While scarcely an earth-shattering work “, Donisthorpe’s 206-page book certainly did not deserve to sink without trace.(46)

Most of Principles of Plutology was devoted to ground-clearing methodology, discussion of definitions, and attacks on plutology’s great methodological rival, ‘political economy’. But yet there was much valuable substantive discussion in Donisthorpe, a lucid writer who admirably wanted to forge a scientific economics that would clearly distinguish between analysis and ethical or political advocacy. Defining plutology as the purely scientific investigation of the uniformity or relations between values, Donisthorpe went on to point out that values are all relative; and that these values, including the value of money, vary continually and unpredictably, in contrast to units such as weights which remain fixed and unvarying. There are different intensities of wants, and different degrees of utility, and the interaction of these utilities and relative scarcities determine values.

In a proto-Austrian manner, Donisthorpe also distinguished between directly useful and indirectly useful goods, and showed how the latter had varying degrees of remoteness from the pleasure-giving stage of goods; in short, Donisthorpe engaged in a sophisticated analysis of the time-structure of production. He also had a pioneering analysis of the influence of substitutes and complements (‘co-elements’) upon values. While Donisthorpe’s discussion of demand curves (i.e. schedules), supply, and price was interesting but hopelessly confused (e.g. he denied that an increased desire of consumers for a product would raise their demand for the product), he did present a remarkably clear foreshadowing of Philip Wicksteed’s insight of four decades later that witholding the stock of a product by suppliers really amounts to the suppliers’ ‘reservation demand’ for that product. Thus Donisthorpe:

In the first place sellers and buyers are not two classes, but one class… To refuse a certain price for an article is to give that price for it. A proprietor who refuses to sell a horse for fifty guineas virtually gives fifty guineas for the horse in the hope of getting more for him another day, or else because he obtains more gratification from the horse than from fifty guineas. Proprietors who do not sell must be regarded as virtually buyers of their own goods.(47)

Perhaps from disappointment at the reception of his book, Wordsworth Donisthorpe, like Hearn before him, abandoned economic theory and plutology from then on, and spent the next two decades battling on behalf of libertarianism and individualism in law and political philosophy.(48)

Endnotes

44. J.A. LaNauze writes of the Hearn work that ‘It was an innovation in English political economy to begin a treatise with a chapter on human wants, and to make the satisfaction of wants a central theme… But his is an innovation only in English writing. The prominence which Hearn gives to wants is simply a reflection of his reading from French literature. His chapter is in places almost a transcription from Bastiat’s Harmonies, and his sub-title echoes Bastiat’s frequently repeated phrase, “Wants, Efforts, Satisfactions.’” J.A. LaNauze, Political Economy in Australia (Carlton, Australia: Melbourne University Press, 1949), pp. 56–8. See also the discussion of Hearn in Salerno, op. cit., note 9, pp. 125–9.

45. Kirzner, op. cit., note 43, pp. 202n7, 212n2.

46. Williams & Norgate was an important publisher of the day, the publisher of Herbert Spencer’s works and of the philosophic journal Mind. This is not surprising in view of the libertarian individualist philosophy common to both Donisthorpe and Spencer.

47. Wordsworth Donisthorpe, Principles of Plutology (London: Williams & Norgate, 1876), p. 132. Also see Peter Newman, ‘Donisthorpe, Wordsworth’, New Palgrave, op. cit., note 9,1, pp. 916–7.

48. On Donisthorpe as libertarian, see W.H. Greenleaf, The British Political Tradition, Vol. II, The Ideological Heritage (London: Methuen, 1983), pp. 277–80.

J. A. La Nauze, "Hearn, William Edward (1826–1888)" (1972)

William Edward Hearn (1826–1888), political economist, jurist, politician and university teacher, was born on 21 April 1826 at Belturbet, County Cavan, Ireland, second of the seven sons of Rev. William Edward Hearn (d.1855) and his wife Henrietta Alicia, née Reynolds, of Kinsale, Ireland. His father, then curate and later vicar of Killargue, County Leitrim, and of Kildrumferton, County Cavan, was a grandson of Archdeacon Daniel Hearn (d.1766), an Englishman who had settled in Ireland early in the eighteenth century. Hearn married first in Dublin in 1847 Rose (d.1877), daughter of Rev. W. J. H. Le Fanu, rector of St Paul’s, Dublin, a member of a celebrated Irish literary family of Huguenot descent, and second at Melbourne in 1878 Isabel, daughter of Major W. G. St Clair, 9th Regiment, Dublin.

After early education at Portora Royal School, Enniskillen, Hearn in 1842 entered Trinity College, Dublin (B.A., 1847; M.A., LL.D., 1863). He had a brilliant career, graduating as first senior moderator in classics and distinguishing himself in logic and ethics. He also studied law at Trinity College under the eminent jurist, Mountifort Longfield, and at the King’s Inn, Dublin, and Lincoln’s Inn, London. He was admitted to the Irish Bar in 1853.

When the Queen’s Colleges, established for Ireland by Peel’s Act of 1845, were opened in 1849, Hearn was nominated professor of Greek at the College of Galway. In 1854 he was chosen by a committee, acting in London for the newly-established University of Melbourne, as the first professor of modern history and literature, political economy and logic. By 1857 his formal responsibilities had been reduced to the subjects of history and political economy, but his versatility was shown by his ready assumption in 1855–56 and again in 1871 of the duties of the professor of classics. One of four original professors, Hearn had probably been attracted to Melbourne by the high salary of £1000 with accommodation in the university building. The choice was amply justified by his academic and public career in a small but lively and growing society, to the intellectual and public life of which he contributed much in the generation after the discovery of gold.

Classes in the university were small but Hearn, who arrived early in 1855, taught a wide range of courses almost single-handed. He was a popular lecturer in a discursive style, much respected personally and as a teacher by students who included such men, later distinguished in literature, law and politics, as Alexander Sutherland, Samuel Alexander, Henry Higgins, (Sir) Isaac Isaacs and Alfred Deakin. In 1873 Hearn was appointed dean of the new faculty of law, surrendering his title of professor but retaining the emoluments and privileges of that position, and lecturing in legal subjects including constitutional law and jurisprudence. He played an active and sometimes stormy part in university politics and administration. In May 1886 he was elected chancellor, but his term as a university council member expiring in October, he was defeated in a strenuously fought contest and so was automatically ineligible for re-election to the chancellorship.

Before his arrival in Melbourne Hearn had published in 1851 The Cassell Prize Essay on the Condition of Ireland, and had written, probably in 1853–54, an ‘Essay on Natural Religion’, a manuscript of some 250 pages defending the argument from design for the existence of a beneficent creator against evolutionary doctrine as it was known in pre-Darwinian form (copy in the Baillieu Library, University of Melbourne). In Melbourne he wrote four books, all characterized by a graceful clarity of style and wide learning, if also by cautious and sometimes superficial judgments. The first three were in their time well known outside Australia and still have modest places in the history of their disciplines; they were indeed remarkable books to have emerged from a colonial society. Plutology or the Theory of the Efforts to Satisfy Human Wants (Melbourne, 1863; London, 1864), a textbook of political economy, was highly praised by William Jevons, Marshall, Edgeworth and other eminent economists. Close examination shows it to be less original than they supposed; Hearn drew heavily on a number of writers not well known in England for his reassessment of ‘classical’ political economy. But his book emphasized a new approach to the question of economic progress, stressing the stimulus of demand rather than the difficulties of supply, and was remarkable for its early, though rather shallow, attempt to apply Darwinian doctrines to the evolution and organization of economic society. Of The Government of England (1867), concerned with the growth of constitutional law and conventions, the jurist, A. V. Dicey, wrote in 1885 that it ‘has taught me more than any other single work of the way in which the labours of lawyers established in early times the elementary principles which form the basis of the constitution’. The Aryan Household (1878) was concerned with the early social institutions, such as the family and the household, of the supposed progenitors of Western European peoples. Hearn’s last book, The Theory of Legal Duties and Rights (1883), gave the theoretical reasoning behind his practical attempts to codify the laws of Victoria. These books brought the young University of Melbourne to the notice of scholars in Europe and America. He also published various pamphlets and lectures and was an active, though anonymous, journalist, writing extensively until 1888 for the leading ‘conservative’ Victorian newspaper, the Argus, and its weekly counterpart the Australasian founded in 1864.

From his first years in Victoria Hearn took a prominent part in public affairs. He was an early advocate of adult educational classes and founded the People’s College at the Melbourne Mechanics’ Institute in an attempt to give, by lectures and examinations, some kind of formal educational qualification other than a university degree. In 1856 he was appointed a member of a board to make suggestions to the Victorian government for the organization of the civil service. Its report, avowedly based on the recent Northcote-Trevelyan report on the British civil service, recommended the establishment of an independent board to control both admission by examination, and promotion. In 1859–60 a royal commission, of which Hearn was a member, presented a weakened version of these recommendations, dropping the board but retaining entrance by examination. An Act of 1862 was based on this report; Hearn argued in 1883, when it was superseded by the more effective Act introduced by James Service, that it had never been fairly tried.

Hearn was a prominent layman of the Church of England, being chancellor of the diocese of Melbourne in 1877–88 and active in the affairs of Trinity College, founded in 1872 as an Anglican residential college of the university. He practised little at the Victorian Bar, to which he was admitted in 1860; his appointment as Q.C. in 1886 was a recognition of his scholarly work in the field of law. His main practical venture in law, his drafting of the Land Act of 1862, had unfortunate consequences. According to the author of the Act, (Sir) Charles Gavan Duffy, Hearn was selected by the attorney-general, Richard Ireland, as draftsman because much care and long consideration would be needed. But there were faults in drafting, which Ireland later admitted were well known to him at the time. These allowed the ostensible purpose of the Act, the dispersal of large pastoral estates, to be evaded within the law by pastoralists acting through their agents or ‘dummies’, though the fault seems to have been Ireland’s rather than Hearn’s.

In January 1859, to the indignation of the chancellor of the university, Sir Redmond Barry, Hearn offered himself unsuccessfully as a candidate at a by-election for the Legislative Assembly, an action which induced the university council to pass a statute, not repealed for a century, forbidding professors to sit in parliament or to become members of any political association. In 1874 and 1877 he was again defeated in elections to the assembly; he met the university council’s protest on the first occasion by pointing out that his standing for parliament was not inconsistent with the tenure of his office, which was now that of a dean, not a professor. In September 1878 he was at last elected to parliament to represent the Central Province in the Legislative Council, at a time when fierce political strife between the ‘Liberal’ followers of the premier, (Sir) Graham Berry, and the conservative element in the colony had culminated in a prolonged deadlock between the two Houses and a rejection of the annual appropriation bill by the council.

By English standards Hearn was a mild conservative, cautious about state intervention in economic affairs but not implacably opposed to it, and a free trader in a colony where ‘liberals’ or ‘radicals’ were almost unanimously protectionists. On such questions his opinions were unchanged during his parliamentary career, and he was easily represented by the Age to be an illiberal reactionary. In fact he soon gained the respect of both sides of the House as being, on most matters, a more or less neutral and well-informed technical critic of legislation, concerned to improve its form and to suggest practical amendments. From 1882 he was regarded as the ‘unofficial leader’ of the House. In his last years he was engaged in drafting an immense code of Victorian law, based on a Benthamite-Austinian view of jurisprudence. It was introduced as a draft bill, provoked formal admiration and recommended for adoption by a committee to which it was referred. Regarded as too abstract by practising lawyers, it was quietly abandoned in favour of simple consolidation.

When Hearn died in Melbourne on 23 April 1888 Victoria lost a scholar who had tempered the rawness of colonial life with learning and intellectual distinction and brought lustre to the name of its young university. Black-bearded and bespectacled, he was witty and courteous, though ambitious and sometimes devious in controversy. If the width of his reading and the lucidity of his style helped to conceal a certain superficiality in his scholarship, and the extent of his debts to others, it was nevertheless a considerable achievement in his circumstances to have written several books which gained high praise from the leading authorities in their fields, and were still occasionally referred to a century after their publication. He founded no ‘school’ in the university; post-graduate studies, affected by the example and ideas of an influential teacher, lay far in the future. But he set an example of humane learning, especially in history and law, to many leaders of Victorian and Australian life in the generation after his death.

Hearn was survived by four of the six children of his first marriage. His only son, William Edward Le Fanu, who had been a medical practitioner at Hamilton, Victoria, died in Western Australia in 1893. His second surviving daughter, Rosalie Juliet Josephine (d.1934) married in 1884 James Young, a Victorian grazier. Of their three sons, James was chaplain to the New Zealand artillery in World War I and Charles Le Fanu (d.1921) after serving as captain in that war, was headmaster of the Cathedral Grammar School, Christchurch. Hearn’s eldest surviving daughter, Charlotte Catherine Frances (d.1943), and the youngest, Henrietta Alice (d.1927), also moved to New Zealand. By his second marriage Hearn had no children.

David Kemp, Section on Hearn in A Free Country, vol. 2, Chap. 10 “Liberalism and the New Economics”

The absent economists

The death, or perhaps dormancy, of academic political economy in Australia in the later nineteenth century might seem surprising, given the early work of William Hearn, one of the four founding professors of the University of Melbourne, a political economist and historian, later Dean of Law, and member of parliament. Hearn was a significant theorist who made a substantial contribution to the development of political economy. His major work in economics, Plutology: Or the Theory of the Efforts to Satisfy Human Wants (1863), was read by the leading political economists in England, and they gave it strong positive acknowledgement. Its title, however, was unfortunately obscure, and its publishers, Macmillan, thought that this might well have put people off. Its sales to the wider public were slow.

In his writing on political economy, Hearn addressed one of the great questions that then puzzled (and in some respects still puzzles) economists and governments: the causes of economic progress. Was it something that was occurring for exceptional reasons—such as some new technology or the colonial expansion—or was its source to be found in more fundamental processes? Hearn’s contribution was to emphasise the importance “of the demand to fulfil human wants, rather than the supply of products, in the dynamics of economic growth.

Hearn rejected the term ‘political economy’ because it seemed to have encouraged a focus on society as a whole (as, for example, in the work of the historical economists), whereas the proper study should be the individual and the circumstances that led individuals to create wealth. The progress of society was driven by the desire of individuals to satisfy their wants, and as a result of that effort society inexorably evolves towards a situation in which those wants are satisfied as a result of increased knowledge and improved ‘industrial powers’.5 His emphasis on the significance of individual decisionmaking was a perspective that was to dovetail with the later work of Jevons in England and of Leon Walras in France and Switzerland.6

Hearn’s view was that society was inevitably evolving towards more cooperative organised forms of action, as evidenced by the evolution from the family to industrial partnerships and complex communities. It was, in fact, the combination of cooperation and exchange that allowed great enterprises to take place and the satisfaction of wants to increase. The role of government “was the issue:

But as men are not gregarious, but political, animals, as they live not merely in society, but in society regulated by law, we must consider, so far at least as it affects industry, that further process of social evolution which is implied in the term Government …

The proper exercise of the legitimate functions of government is at all times most beneficial to industry, and is essential to its complete development. The improper or defective performance of those functions, and their undue extension, are among the most formidable obstacles with which industry has to contend.7

On the role of government, Hearn was in the camp of Herbert Spencer’s Social Statics and of John Stuart Mill’s On Liberty, recently published. Indeed, Herbert Spencer knew of and admired Hearn as the first writer who ‘clearly perceived how institutions were the product of evolution’.8 To Hearn, it was self-evident that ‘before a man can rightly use his freedom, he must be accustomed to be free’.9 The dangers of misguided state intervention were obvious: ‘as wrong leads to wrong, so every interference necessitates or at least appears to necessitate its successor’.10 He was confident that the lesson had now been learnt and that there was little risk in any Anglo-Saxon country that ‘the old extravagances of state-action will be revived’:

When a reader of the present day learns that about eighty years ago Jeremy Bentham’s father was brought before a magistrate on a charge of wearing unlawful buttons, he can hardly restrain an incredulous smile.

Yet although its outward manifestations are thus changed, the spirit which gave rise to this perversion of the functions of the state is still vigorous. In one place, it appears in the form of communism, or of socialism, or of some kindred system. In another it wears the more modest disguise of protection …11

Hearn was a life-long supporter of free trade, and when he entered parliament in 1878 as a member for the Central Province of the Legislative Council in Victoria, he was vigorously criticised by the Age as an ‘illiberal reactionary’ for his failure to support Syme’s nationalist and restrictionist policies, even though his views were classically liberal. Nevertheless his personal qualities and his expert opinions on legal matters gave him high standing and ‘from 1882 he was regarded as the “unofficial leader” of the [Council]’.12

Despite Hearn’s path-breaking work, however, political economy as a field of academic study was close to non-existent in Australia by the last two decades of the nineteenth century. The secular universities had been established to provide the rational knowledge that would advance civilisation and government in Australia. By the last decades of the nineteenth century they were failing in that task insofar as the understanding of the liberal economy was concerned.

Sydney University had had no course on political economy in its published curriculum since 1867 (when there was briefly an offering), until shortly after Federation, when a Department of Commerce and Economics was finally established. Occasionally lectures on political economy were given as part of the philosophy course.13

In Victoria, Melbourne University had had a course in political economy from its foundation, but when Hearn vacated his chair in 1876, it was filled by J.R. Elkington until 1912, a period that has been described by La Nauze as ‘completely unproductive’.14 Elkington was a well-regarded teacher and a popular colleague, but his academic interests were in history and constitutional law rather than political economy, and his wider interests were particularly in civic affairs.

Endnotes

5 William Edward Hearn, Plutology: Or the Theory of the Efforts to Satisfy Human Wants (1864), Kessinger Publishing, Whitefish, MT, 2010, p. 8.

6 J.A. La Nauze, ‘Hearn, William Edward (1826–1888)’, ADB, vol. 4, p. 371.

7 Hearn, Plutology, pp. 10–11.

8 Owen Dixon, Jesting Pilate: and Other Papers and Addresses, Law Book Co., Sydney, 1965, p. 42.

9 Hearn, Plutology, p. 442.

10 Ibid.

11 Ibid., p. 443.

12 La Nauze, ‘Hearn’, p. 371.

13 La Nauze, Political Economy, pp. 18–19.